A Historical Perspective: African Contributions to American Culture

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|24

|10797

|50

Essay

AI Summary

This essay explores the significant contributions of Africans to American culture, challenging earlier debates about the survival of African heritage in the United States. It highlights how enslaved Africans, primarily from the Bantu-speaking regions, retained and adapted their cultural traditions despite the hardships of slavery. The essay details African expertise in agriculture, particularly rice cultivation in South Carolina, and their role in developing the American dairy industry and open grazing practices. It also discusses the influence of African folklore, such as the Brer Rabbit tales, and the cultural significance of Congo Square in New Orleans, where African dances and music thrived. The essay emphasizes the lasting impact of African traditions on American cuisine, language, and performing arts, demonstrating the profound and often unacknowledged role of Africans in shaping American identity and culture. Desklib provides this and many other solved assignments for students.

AFRICAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN CULTURE

By Joseph E. Holloway Ph.D

Source:THE SLAVE REBELLION WEB SITE

(http://slaverebellion.org/index.php?page=african-contribution-to-american-culture)

Scholars have long recognized African origins in the linguistic forms and

the culturaltraits of African Americans, and thus assumed that these

Africanisms were derived principally from West Africa. There has been

much debate over the origins of African culture in the U.S. The classic

debate between Melville J. Herskovits and E. Franklin Frazier is still

relevant. To revisit it briefly, Frazier believed that Black Americans lost

their African heritage during slavery; thus, the African American culture

evolved independently of any African influences. Herskovits argued the

opposite that it was not possible to understand and appreciate African

American culture without understanding its African linkages and carryover

called Africanisms.Current scholars are more concernedwith using a

transnational framework to examine how African cultural survivals have

changed over time and readapted to diasporic conditions while

experiencing slavery, forced labor, and racial discrimination.

The new scholarship suggests that the West Africans contributed primarily

to Euro-American culture whereas people who came from the vast Bantu

speaking areas of Africa, to the east and south of West Africa, are tho

most likely to have left an African cultural heritage to African Americans.

Plantation slavery tended to acculturate West Africans relatively quickly,

yet unwittingly encouraged retention of African traditions among others.

Enslaved Africans, not free to openly transport kinship, courts, religion,

and material cultures, were forced to disguise or abandon them during the

Middle Passage. Instead, they dematerialized their cultural artifacts during

the Middle Passage to rematerialize African culture on their arrival in the

New World. Africans arrived in the New World capable of using Old

World knowledge to create New World realities.

Africans, and their descendants, contributed to the richness and fullness of

American culture from its beginnings. Their contributions in early

America, for which they have received little or no credit, include the

developmentof the American dairy industry, open grazing of cattle,

artificial insemination of cows, the development of vaccines (including

vaccination for smallpox), and cures for snake bites.

By Joseph E. Holloway Ph.D

Source:THE SLAVE REBELLION WEB SITE

(http://slaverebellion.org/index.php?page=african-contribution-to-american-culture)

Scholars have long recognized African origins in the linguistic forms and

the culturaltraits of African Americans, and thus assumed that these

Africanisms were derived principally from West Africa. There has been

much debate over the origins of African culture in the U.S. The classic

debate between Melville J. Herskovits and E. Franklin Frazier is still

relevant. To revisit it briefly, Frazier believed that Black Americans lost

their African heritage during slavery; thus, the African American culture

evolved independently of any African influences. Herskovits argued the

opposite that it was not possible to understand and appreciate African

American culture without understanding its African linkages and carryover

called Africanisms.Current scholars are more concernedwith using a

transnational framework to examine how African cultural survivals have

changed over time and readapted to diasporic conditions while

experiencing slavery, forced labor, and racial discrimination.

The new scholarship suggests that the West Africans contributed primarily

to Euro-American culture whereas people who came from the vast Bantu

speaking areas of Africa, to the east and south of West Africa, are tho

most likely to have left an African cultural heritage to African Americans.

Plantation slavery tended to acculturate West Africans relatively quickly,

yet unwittingly encouraged retention of African traditions among others.

Enslaved Africans, not free to openly transport kinship, courts, religion,

and material cultures, were forced to disguise or abandon them during the

Middle Passage. Instead, they dematerialized their cultural artifacts during

the Middle Passage to rematerialize African culture on their arrival in the

New World. Africans arrived in the New World capable of using Old

World knowledge to create New World realities.

Africans, and their descendants, contributed to the richness and fullness of

American culture from its beginnings. Their contributions in early

America, for which they have received little or no credit, include the

developmentof the American dairy industry, open grazing of cattle,

artificial insemination of cows, the development of vaccines (including

vaccination for smallpox), and cures for snake bites.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

African stories and folklore, such as the Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and Chicken

Little tales originated in Africa, and were absorbed into America’s culture

of childhood and laid a foundation for American nursery culture. Despite

the limitations imposed by slavery, Africans and their descendants made

substantial contributions to American culture in aesthetics,animal

husbandry, agriculture, cuisine, folklore, folk medicine and language. This

chapter examines African contribution to American culture.

AFRICAN RICE CULTIVATION

The major contribution of enslaved Africans was in agriculture. In the

1740s, rice from Madagascar was introduced to South Carolina’s farming

economy. Africans, experts in rice cultivation, were transported from the

island of Goree, off the coast of what is now the Senegambia, to train

Europeans to cultivate this new crop.

The first successful cultivation of rice in the New World was accomplished

in the South Carolina Sea Islands by an African woman who later showed

her owner how to cultivate rice. The first rice seeds were imported directly

from the island of Madagascar in 1685; Africans supplied the labor and the

technical expertise for this new crop industry. Africans off the coast of

Senegal helped train Europeans in the methods of cultivation and those

who specialized in rice cultivation were imported directly from the island

of Goree. Africans were able to successfully transfer their rice culture to the

New World. The method of rice cultivation used in West Africa and South

Carolina was identical. Enslaved Africans used three basic systems: ground

water, springs, and soil moisture retention, or high water table. These three

systems are found on both sides of the Atlantic, and formed the basis for

South Carolina’s antebellum economy.

Early Africans brought with them highly developed skills in metal

working, leather work, pottery, and weaving. Senegambianswere

employed as medicine men (root doctors), Blacksmiths, harness makers,

carpenters, and lumberjacks. These trades were passed down to other

enslaved Africans by the skilled African craftsmen in an apprentice-type

fashion.

Traditional African food culture has been preserved even today in many

areas of American cuisine, as in the technique of deep fat frying, southern

stews (gumbos), and nut stews. Okra, tania, Blackeyed peas, kidney an

lima bean were all brought on slave ships as food gathered in Africa for the

Africans during the transatlantic voyage. Fufu, a traditional African meal

throughout the continent, was eaten from the Senegambia to Angola an

Little tales originated in Africa, and were absorbed into America’s culture

of childhood and laid a foundation for American nursery culture. Despite

the limitations imposed by slavery, Africans and their descendants made

substantial contributions to American culture in aesthetics,animal

husbandry, agriculture, cuisine, folklore, folk medicine and language. This

chapter examines African contribution to American culture.

AFRICAN RICE CULTIVATION

The major contribution of enslaved Africans was in agriculture. In the

1740s, rice from Madagascar was introduced to South Carolina’s farming

economy. Africans, experts in rice cultivation, were transported from the

island of Goree, off the coast of what is now the Senegambia, to train

Europeans to cultivate this new crop.

The first successful cultivation of rice in the New World was accomplished

in the South Carolina Sea Islands by an African woman who later showed

her owner how to cultivate rice. The first rice seeds were imported directly

from the island of Madagascar in 1685; Africans supplied the labor and the

technical expertise for this new crop industry. Africans off the coast of

Senegal helped train Europeans in the methods of cultivation and those

who specialized in rice cultivation were imported directly from the island

of Goree. Africans were able to successfully transfer their rice culture to the

New World. The method of rice cultivation used in West Africa and South

Carolina was identical. Enslaved Africans used three basic systems: ground

water, springs, and soil moisture retention, or high water table. These three

systems are found on both sides of the Atlantic, and formed the basis for

South Carolina’s antebellum economy.

Early Africans brought with them highly developed skills in metal

working, leather work, pottery, and weaving. Senegambianswere

employed as medicine men (root doctors), Blacksmiths, harness makers,

carpenters, and lumberjacks. These trades were passed down to other

enslaved Africans by the skilled African craftsmen in an apprentice-type

fashion.

Traditional African food culture has been preserved even today in many

areas of American cuisine, as in the technique of deep fat frying, southern

stews (gumbos), and nut stews. Okra, tania, Blackeyed peas, kidney an

lima bean were all brought on slave ships as food gathered in Africa for the

Africans during the transatlantic voyage. Fufu, a traditional African meal

throughout the continent, was eaten from the Senegambia to Angola an

was assimilated into American culture as “turn meal and flour” in South

Carolina. Corn bread prepared by African slaves was similar to the African

millet bread. In some of the slave narrative reports, “cornbread” was

referred to as one of the foods that accompanied them to the New World.

AFRICAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN “COWBOY” CULTURE

The first major contribution by Africans to North American society was in

the arena of cattle raising. When the Fulani (or Fula) people from

Senegambia, along with longhorn cattle, were imported to South Carolina

in 1731, colonial herds increased from 500 to 6,784 some 30 years lat

These Fulas were expert cattlemen and were responsible for introducing

African husbandry patterns of open grazing now practiced throughout the

American cattle industry. Cattle drives to the centers of distribution were

innovations Africans brought with them as contributions to a developing

industry. Originally a cowboy was an African who worked with cattle, just

as a houseboy worked in “de big House.” Open grazing made practical use

of an abundance of land and a limited labor force.

Africans and their descendants were America’s first cowboys. Most people

are not aware that many cowboys of the American West were Black,

contrary to how the film industry and the media have portrayed them.

Only recently have we begun to recognize the extent to which cowboy

culture has African roots. Many details of cowboy life, work, and even

material culture can be traced to the Fulani, America’s first cowboys, b

there has been little investigation of this by historians of the American

West.

Contemporary descriptions of local West African animal husbandry bear a

striking resemblanceto what appeared in Carolina and later in the

American dairy and cattle industries. Africans introduced the first artificial

insemination and the use of cows’ milk for human consumption. Peter

Wood believes that from this early relationship between cattle and Africans

the word, “cowboy” originated.

As late as 1865, following the Civil War, Africans whose responsibilities

were with cattle were referred to as “cowboys’ in plantation records. After

1865, whites associated with the cattle industry referred to themselves

“cattlemen,”to distinguish themselvesfrom the Black cowboys. The

annual North-South migratory patterns the cowboys followed are directly

related to the migratory patterns of the Fulani cattle herders who lived

scattered throughout Nigeria and Niger. Not only were Africans imported

Carolina. Corn bread prepared by African slaves was similar to the African

millet bread. In some of the slave narrative reports, “cornbread” was

referred to as one of the foods that accompanied them to the New World.

AFRICAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN “COWBOY” CULTURE

The first major contribution by Africans to North American society was in

the arena of cattle raising. When the Fulani (or Fula) people from

Senegambia, along with longhorn cattle, were imported to South Carolina

in 1731, colonial herds increased from 500 to 6,784 some 30 years lat

These Fulas were expert cattlemen and were responsible for introducing

African husbandry patterns of open grazing now practiced throughout the

American cattle industry. Cattle drives to the centers of distribution were

innovations Africans brought with them as contributions to a developing

industry. Originally a cowboy was an African who worked with cattle, just

as a houseboy worked in “de big House.” Open grazing made practical use

of an abundance of land and a limited labor force.

Africans and their descendants were America’s first cowboys. Most people

are not aware that many cowboys of the American West were Black,

contrary to how the film industry and the media have portrayed them.

Only recently have we begun to recognize the extent to which cowboy

culture has African roots. Many details of cowboy life, work, and even

material culture can be traced to the Fulani, America’s first cowboys, b

there has been little investigation of this by historians of the American

West.

Contemporary descriptions of local West African animal husbandry bear a

striking resemblanceto what appeared in Carolina and later in the

American dairy and cattle industries. Africans introduced the first artificial

insemination and the use of cows’ milk for human consumption. Peter

Wood believes that from this early relationship between cattle and Africans

the word, “cowboy” originated.

As late as 1865, following the Civil War, Africans whose responsibilities

were with cattle were referred to as “cowboys’ in plantation records. After

1865, whites associated with the cattle industry referred to themselves

“cattlemen,”to distinguish themselvesfrom the Black cowboys. The

annual North-South migratory patterns the cowboys followed are directly

related to the migratory patterns of the Fulani cattle herders who lived

scattered throughout Nigeria and Niger. Not only were Africans imported

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

with the expertise to handle cattle, but the African longhorn was imported

as well, a breed that later became known as the Texas longhorn.

Much of the early language associated with cowboy culture had a stron

African flavor. The word buckra (buckaroo) is derived from Mbakara, the

Efik/lbibio work for “poor white man.” It was used to describe a class of

whites who worked as broncobusters,bucking and breaking horses.

Planters used buckras as broncobusters because slaves were too valuable to

risk injury. Another African word that found its way into popular cowboy

songs is “get along little dogies.” The word “doggies” originated from

Kimbundu, along with kidogo, a little something, and dodo, small. After the

Civil War when great cattle roundups began, Black cowboys introduced

such Africanisms to cowboy language and songs.

TALES OUT OF AFRICA

In the area of folklore, Brer Rabbit, Brer Wolf, Brer Bear, and Sis’ Nann

Goat were part of the folklore the Wolof brought by way of the Hausa, Fula

(Fulani), and the Mandinka. Other West African tales of a trickster Hare

were also introduced. The Spider (Anansi) tales appeared in the United

States in the form of Aunt Nancy and Brer Rabbit stories. All the stories of

Uncle Remus, as retold in the Sea Islands, are Hausa in origin via the

Mande (Mandinka). These African tales laid the foundation for American

nursery rhymes.

These stories found their way into American culture as told by slaves. The

Chicken Little story is also part of this tradition, and originated unaltered

from Africa. The Hare and Hyena, corresponds to Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox

tales. African slaves who fled to the Creek Indian Nation introduced these

West African Trickster tales, which were also adopted by the Seminoles.

THE CONGO SQUARE

Le placed du Congo, Congo Square, is in old New Orleans. An ordinance

of the Municipal Council, adopted on October 15, 1817, made the name of

this traditional place law. It was considered one of the unique attractions of

old New Orleans, ranking second only to the Quadroon Ball. At the square,

women wore dotted calico dresses with brightly colored Madras kerchiefs

tied about their hair, to form the popular headdress called the tignon.

Children wore garments with brightfeathers and bits of ribbon.The

favorite dances of the slaves in Congo Square were the bamboula and the

calinda, two Congo dances, the latter being a variation of the former th

was also danced in voodoo ceremonies.

as well, a breed that later became known as the Texas longhorn.

Much of the early language associated with cowboy culture had a stron

African flavor. The word buckra (buckaroo) is derived from Mbakara, the

Efik/lbibio work for “poor white man.” It was used to describe a class of

whites who worked as broncobusters,bucking and breaking horses.

Planters used buckras as broncobusters because slaves were too valuable to

risk injury. Another African word that found its way into popular cowboy

songs is “get along little dogies.” The word “doggies” originated from

Kimbundu, along with kidogo, a little something, and dodo, small. After the

Civil War when great cattle roundups began, Black cowboys introduced

such Africanisms to cowboy language and songs.

TALES OUT OF AFRICA

In the area of folklore, Brer Rabbit, Brer Wolf, Brer Bear, and Sis’ Nann

Goat were part of the folklore the Wolof brought by way of the Hausa, Fula

(Fulani), and the Mandinka. Other West African tales of a trickster Hare

were also introduced. The Spider (Anansi) tales appeared in the United

States in the form of Aunt Nancy and Brer Rabbit stories. All the stories of

Uncle Remus, as retold in the Sea Islands, are Hausa in origin via the

Mande (Mandinka). These African tales laid the foundation for American

nursery rhymes.

These stories found their way into American culture as told by slaves. The

Chicken Little story is also part of this tradition, and originated unaltered

from Africa. The Hare and Hyena, corresponds to Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox

tales. African slaves who fled to the Creek Indian Nation introduced these

West African Trickster tales, which were also adopted by the Seminoles.

THE CONGO SQUARE

Le placed du Congo, Congo Square, is in old New Orleans. An ordinance

of the Municipal Council, adopted on October 15, 1817, made the name of

this traditional place law. It was considered one of the unique attractions of

old New Orleans, ranking second only to the Quadroon Ball. At the square,

women wore dotted calico dresses with brightly colored Madras kerchiefs

tied about their hair, to form the popular headdress called the tignon.

Children wore garments with brightfeathers and bits of ribbon.The

favorite dances of the slaves in Congo Square were the bamboula and the

calinda, two Congo dances, the latter being a variation of the former th

was also danced in voodoo ceremonies.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Another favorite dance at the Congo Square was the Chica, which was very

popular during the slave era. The talent of the female dancer resides in the

perfection of her ability to move her hips, the bottom parts of her wai

with the rest of the body remaining in a sort of stillness which does n

disturb the weak swaying of her hands, waving the ends of a handkerchief

or her waist petticoat. A male gets closer to her, leaping up suddenly, and

falls back rhythmically, almost touching her. He pulls back, leaps up again

and challenges her to the most seductive duel. The dance gets animate

and soon becomes lustful.

Another dance particular to New Orleans and the Congo Square was th

Ombliguide. This dance was criticized in 1766 by the New Orleans City

Council. The dance is performed by four men and four women and

involved objectionable movements with navel-to-navel contact, a common

trait of Angolan traditional dancing. Enslaved Africans came regularly to

Congo Square to perform the Ombliguide and other Congo dances, such as

the Calinda, Bamboula and Chica, all transplanted directly from Central

Africa. The partial Europeanization of some of these African movements

eventually created the native dances of Latin American countries such a

the Marcumbi, a dance learned by the Spanish and later brought to La

America. The Fandango, the national dance of Spain, originated in Cuba,

from African dances. Other dances derived from the Ombliguide are th

Chacharara, Cadomba, Melongo, Malamba, Gati, Samba, Rhumba, Mamba,

Conga and Tango.

The “ring shout” was a dance performed in the Congo Square, also. This is

a dance involving people moving aroundin a circle counterclockwise,

rhythmically shuffling their feet and shaking their hands while those

outside the ring clap, sing, and gesticulate. Movement in a ring during

ceremonies honoring the ancestors was an integral part of life in Centr

Africa and is believed to have been transported to Congo Square direct

from Africa.

Enslaved Africans maintained their music, song, and dance cultures as they

adapted to life in the New World. Many African dances survived because

they were reshaped and adopted by European Americans, while others

remained intact, or changed with the new circumstances. For example, the

ring shout started as a sacred Kongolese dance, but later found expression

in non sacred forms of dance.

In both Africa and the New World, the circle ritual had different meanings

in the distinct cultures. In the Kongo, the ring shout circle is identical to the

Gullah counterclockwise dance, which is linked to the most important

popular during the slave era. The talent of the female dancer resides in the

perfection of her ability to move her hips, the bottom parts of her wai

with the rest of the body remaining in a sort of stillness which does n

disturb the weak swaying of her hands, waving the ends of a handkerchief

or her waist petticoat. A male gets closer to her, leaping up suddenly, and

falls back rhythmically, almost touching her. He pulls back, leaps up again

and challenges her to the most seductive duel. The dance gets animate

and soon becomes lustful.

Another dance particular to New Orleans and the Congo Square was th

Ombliguide. This dance was criticized in 1766 by the New Orleans City

Council. The dance is performed by four men and four women and

involved objectionable movements with navel-to-navel contact, a common

trait of Angolan traditional dancing. Enslaved Africans came regularly to

Congo Square to perform the Ombliguide and other Congo dances, such as

the Calinda, Bamboula and Chica, all transplanted directly from Central

Africa. The partial Europeanization of some of these African movements

eventually created the native dances of Latin American countries such a

the Marcumbi, a dance learned by the Spanish and later brought to La

America. The Fandango, the national dance of Spain, originated in Cuba,

from African dances. Other dances derived from the Ombliguide are th

Chacharara, Cadomba, Melongo, Malamba, Gati, Samba, Rhumba, Mamba,

Conga and Tango.

The “ring shout” was a dance performed in the Congo Square, also. This is

a dance involving people moving aroundin a circle counterclockwise,

rhythmically shuffling their feet and shaking their hands while those

outside the ring clap, sing, and gesticulate. Movement in a ring during

ceremonies honoring the ancestors was an integral part of life in Centr

Africa and is believed to have been transported to Congo Square direct

from Africa.

Enslaved Africans maintained their music, song, and dance cultures as they

adapted to life in the New World. Many African dances survived because

they were reshaped and adopted by European Americans, while others

remained intact, or changed with the new circumstances. For example, the

ring shout started as a sacred Kongolese dance, but later found expression

in non sacred forms of dance.

In both Africa and the New World, the circle ritual had different meanings

in the distinct cultures. In the Kongo, the ring shout circle is identical to the

Gullah counterclockwise dance, which is linked to the most important

African ceremony – the rites of passage. Among the Mande, the circle

dance is a part of the marriage and birth ceremonies, and in Wolof culture,

the ring circle is central to most dancing.

The Bamboula and the Calinda, variations of voodoo dance, became

popular forms of dance expression in early New Orleans. The Cakewalk

and the Charleston traveled from Africa to become integral to American

dance forms on the American plantation.

The Calinda, also known as La Calinda, is one of the earliest forms of

African dance seen in America. This Kongo/Angolan dance first became

popular in Santo Domingo, then in Haiti and New Orleans. La Calinda is

first reported by Dessalles in 1654 and by a French monk, Jean Baptist

Labat, who went to Martinique as a missionary in 1694. The Calinda is a

variation of a dance used in voodoo ceremonies, and is always performed

by male and female dancers in couples. The dancers move to the middle of

the circle and begin to dance. Each dancer chooses a partner and performs

the dance, with few variations, by taking a step in which every leg is

straightened and pulled back alternatively with a quick strike, sometime

on point, sometimes with a grounded heel. This dance is performed in

manner slightly similar to that of the Anglaise. The male dancer turns by

himself or goes around his partner, who also makes a turn and changes her

position while waving the ends of a handkerchief. Her partner raises his

hands in almost clenched fists up and down alternately, with his elbow

close to his body. This dance is vivid and lively. In 1704, records show that

a police ordinance was issued prohibiting night gatherings from

performing the Calinda on plantations.

SLAVE MUSIC AND THE BANJO

The dance now known as the Charleston had the greatest influence on

American dance culture than any other imported African dance. It is a

form of the jitterbug dance, which is a general term applied to

unconventional, often formless and violent, social dances performed to

syncopatedmusic. Enslaved Africans brought it from the Kongo to

Charleston, South Carolina, as the juba dance, which then slowly evolved

into what is now the Charleston. This one-legged sembuka step, over-and-

cross, arrived in Charleston between 1735 and 1740. Similar in type to the

“one-legged” sembuka-style dancing found in northern Kongo, the dance

consists of “patting” (otherwise known as “patting Juba”), stamping,

clapping, and slapping of arms, chest, and so forth. The name “Charleston”

was given to the Juba dance by European Americans. In Africa, however,

the dance is called the Juba, or Djouba.

dance is a part of the marriage and birth ceremonies, and in Wolof culture,

the ring circle is central to most dancing.

The Bamboula and the Calinda, variations of voodoo dance, became

popular forms of dance expression in early New Orleans. The Cakewalk

and the Charleston traveled from Africa to become integral to American

dance forms on the American plantation.

The Calinda, also known as La Calinda, is one of the earliest forms of

African dance seen in America. This Kongo/Angolan dance first became

popular in Santo Domingo, then in Haiti and New Orleans. La Calinda is

first reported by Dessalles in 1654 and by a French monk, Jean Baptist

Labat, who went to Martinique as a missionary in 1694. The Calinda is a

variation of a dance used in voodoo ceremonies, and is always performed

by male and female dancers in couples. The dancers move to the middle of

the circle and begin to dance. Each dancer chooses a partner and performs

the dance, with few variations, by taking a step in which every leg is

straightened and pulled back alternatively with a quick strike, sometime

on point, sometimes with a grounded heel. This dance is performed in

manner slightly similar to that of the Anglaise. The male dancer turns by

himself or goes around his partner, who also makes a turn and changes her

position while waving the ends of a handkerchief. Her partner raises his

hands in almost clenched fists up and down alternately, with his elbow

close to his body. This dance is vivid and lively. In 1704, records show that

a police ordinance was issued prohibiting night gatherings from

performing the Calinda on plantations.

SLAVE MUSIC AND THE BANJO

The dance now known as the Charleston had the greatest influence on

American dance culture than any other imported African dance. It is a

form of the jitterbug dance, which is a general term applied to

unconventional, often formless and violent, social dances performed to

syncopatedmusic. Enslaved Africans brought it from the Kongo to

Charleston, South Carolina, as the juba dance, which then slowly evolved

into what is now the Charleston. This one-legged sembuka step, over-and-

cross, arrived in Charleston between 1735 and 1740. Similar in type to the

“one-legged” sembuka-style dancing found in northern Kongo, the dance

consists of “patting” (otherwise known as “patting Juba”), stamping,

clapping, and slapping of arms, chest, and so forth. The name “Charleston”

was given to the Juba dance by European Americans. In Africa, however,

the dance is called the Juba, or Djouba.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1781: “The instrument proper to them [Africa

American] is the Banjar, brought from Africa, and which is the [form] of the gu

its chords being precisely the four lower chords of the guitar.” The ba

known in America as an African instrument until the 1840s, when minstrel

shows took it as a part of their Blackface acts. As a result, the banjo became

a badge of ridicule and Blacks abandoned it, allowing southern whites to

claim it as their own invention.

Benjamin Latrobe, an American architect,while in New Orleans also

noticed that the banjo was particular to Africans. In his own words, “a

crowd of 5 or 600 persons assembled in an open space or public square. I we

the spot & crowded near enough to see the performance. All those wh

engaged in the business seemed to be Blacks. I did not observe a do

faces. They were formed into circular groups [sic] in the midst of four of whic

which I examined (but there were more of them), was a ring, the largest not 1

in diameter. In the first were two women dancing. They held each a

handkerchief extended by the corners in their hands & set to each oth

miserably dull & slow figure, hardly moving their feet or bodies. The m

consisted of two drums and a stringed instrument. An old man sat ast

cylindrical drum about a foot in diameter, & beat it with incredible quickness w

the edge of his hand & fingers. The other drum was an open staved

between the knees & beaten in the same manner. They made an incredible n

The most curious instrument, however, was a stringed instrument which no do

was imported from Africa. On the top of the finger board was the rude figure

man in a sitting posture, & two pegs behind him to which the strings

fastened. The body was a calabash. It was played upon by a very little old ma

apparently 80 or 90 years old.”

Other African instruments that survived the Middle Passage were the

thumb piano also known as the mbira, common in the late 19th century in

New Orleans, and the cane fifes found in both West and Central Africa

The making and playing of cane fifes survived the Middle Passage.

Africans and African Americans use the same technique to make them.

African drums were common until the Stono Rebellion of 1739. Talking

drums were well known on both sides of the Atlantic, especially for the

use in slave revolts. The first description of the use of drums in America

comes from the official account of the Stono slave rebellion in South

Carolina where they were used by Angolans. Afterward the colony of

South Carolina in the Slave Act of 1740 passed laws prohibiting “drums

horns, or other loud instruments.”

American] is the Banjar, brought from Africa, and which is the [form] of the gu

its chords being precisely the four lower chords of the guitar.” The ba

known in America as an African instrument until the 1840s, when minstrel

shows took it as a part of their Blackface acts. As a result, the banjo became

a badge of ridicule and Blacks abandoned it, allowing southern whites to

claim it as their own invention.

Benjamin Latrobe, an American architect,while in New Orleans also

noticed that the banjo was particular to Africans. In his own words, “a

crowd of 5 or 600 persons assembled in an open space or public square. I we

the spot & crowded near enough to see the performance. All those wh

engaged in the business seemed to be Blacks. I did not observe a do

faces. They were formed into circular groups [sic] in the midst of four of whic

which I examined (but there were more of them), was a ring, the largest not 1

in diameter. In the first were two women dancing. They held each a

handkerchief extended by the corners in their hands & set to each oth

miserably dull & slow figure, hardly moving their feet or bodies. The m

consisted of two drums and a stringed instrument. An old man sat ast

cylindrical drum about a foot in diameter, & beat it with incredible quickness w

the edge of his hand & fingers. The other drum was an open staved

between the knees & beaten in the same manner. They made an incredible n

The most curious instrument, however, was a stringed instrument which no do

was imported from Africa. On the top of the finger board was the rude figure

man in a sitting posture, & two pegs behind him to which the strings

fastened. The body was a calabash. It was played upon by a very little old ma

apparently 80 or 90 years old.”

Other African instruments that survived the Middle Passage were the

thumb piano also known as the mbira, common in the late 19th century in

New Orleans, and the cane fifes found in both West and Central Africa

The making and playing of cane fifes survived the Middle Passage.

Africans and African Americans use the same technique to make them.

African drums were common until the Stono Rebellion of 1739. Talking

drums were well known on both sides of the Atlantic, especially for the

use in slave revolts. The first description of the use of drums in America

comes from the official account of the Stono slave rebellion in South

Carolina where they were used by Angolans. Afterward the colony of

South Carolina in the Slave Act of 1740 passed laws prohibiting “drums

horns, or other loud instruments.”

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

One of the most popular chordophones is from the Kongo/Angolan area,

the mouth-resonatedMusical Bow. It only appeared sporadically in

African American culture when compared to its diffusion from Africa to

South America and the Caribbean, where it is played by Africans, Native

Americans and mixed groups. Today the African Mouth Bow’s greatest

U.S. distribution is in isolated white communitiesin the Ozark and

Appalachian mountains.

AFRICAN INFLUENCES ON WHITE AMERICAN CULTURE

David Dalby has identified early linguistic retention and traced many

Americanisms to Wolof including such words as OK (okay), bogus, boogie-

woogie, bug (insect), John, phony, guy, honkie, dig (to understand), jam

jamboree, jitter(bug), jive, juke(box), fuzz (police), hippie, mumbo-jumbo,

phoney, root toot(y), and rap, to name a few. Other linguistic Africanisms

first used by Americans includes words such as banana, banjo, cola (as in

Coca-Cola), elephant, goober (peanut), gorilla, gumbo, okra, sorcery, tater,

tote and turnip. [For further reading on African Linguistic retention, see

Holloway and Vass, The African Heritage of American English].

The acculturation process was mutual, as well as reciprocal. Africans

assimilated white culture, and planters adopted some aspects of African

customs and practices, such as the African agricultural methods of rice

cultivation, African cuisine (southern cooking), open grazing of cattle, and

uses of herbal medicinesto cure New World diseases. For example,

Africans are credited for bringing folk treatment for small pox, knowledge

of birth by Caesarian section (pharaonic in origin), and cures for snake bites

and other poisons.

Through the root doctor, Africans brought holistic health practices to th

plantations. The African house servants also learned new domestic skills,

including the art of quilting from their mistresses. They took a European

quilting technique and Africanized it by combining their appliqué style,

reflecting a pattern and form which are still found today in the Akan and

Fon textile industries of West Africa. While many of the Mandes were

enslaved as craftsmen, artisans, and house servants, the field slaves we

mainly Central Africans who, unlike the Senegambians,brought a

homogeneous,identifiable culture. The Bantus often possessedgood

metallurgical and woodworking skills. They had particular skill in iron

working, making the wrought iron balconies in New Orleans and

Charleston.

the mouth-resonatedMusical Bow. It only appeared sporadically in

African American culture when compared to its diffusion from Africa to

South America and the Caribbean, where it is played by Africans, Native

Americans and mixed groups. Today the African Mouth Bow’s greatest

U.S. distribution is in isolated white communitiesin the Ozark and

Appalachian mountains.

AFRICAN INFLUENCES ON WHITE AMERICAN CULTURE

David Dalby has identified early linguistic retention and traced many

Americanisms to Wolof including such words as OK (okay), bogus, boogie-

woogie, bug (insect), John, phony, guy, honkie, dig (to understand), jam

jamboree, jitter(bug), jive, juke(box), fuzz (police), hippie, mumbo-jumbo,

phoney, root toot(y), and rap, to name a few. Other linguistic Africanisms

first used by Americans includes words such as banana, banjo, cola (as in

Coca-Cola), elephant, goober (peanut), gorilla, gumbo, okra, sorcery, tater,

tote and turnip. [For further reading on African Linguistic retention, see

Holloway and Vass, The African Heritage of American English].

The acculturation process was mutual, as well as reciprocal. Africans

assimilated white culture, and planters adopted some aspects of African

customs and practices, such as the African agricultural methods of rice

cultivation, African cuisine (southern cooking), open grazing of cattle, and

uses of herbal medicinesto cure New World diseases. For example,

Africans are credited for bringing folk treatment for small pox, knowledge

of birth by Caesarian section (pharaonic in origin), and cures for snake bites

and other poisons.

Through the root doctor, Africans brought holistic health practices to th

plantations. The African house servants also learned new domestic skills,

including the art of quilting from their mistresses. They took a European

quilting technique and Africanized it by combining their appliqué style,

reflecting a pattern and form which are still found today in the Akan and

Fon textile industries of West Africa. While many of the Mandes were

enslaved as craftsmen, artisans, and house servants, the field slaves we

mainly Central Africans who, unlike the Senegambians,brought a

homogeneous,identifiable culture. The Bantus often possessedgood

metallurgical and woodworking skills. They had particular skill in iron

working, making the wrought iron balconies in New Orleans and

Charleston.

As field workers the Bantus were kept away from the developing

mainstreamof white American culture. This isolation worked to the

Bantus’ advantage in that it allowed their culture to escape acculturatio

and maintained their homogeneity. Bantu contributions to South Carolina

and Louisiana included not only wrought iron balconies, but also wood

carvings, basketry, weaving, clay-baked figurines, and pottery.

Cosmograms, grave designs and decorations, funeral practices, and the

wake are Bantu in origin. Bantu musical contributions include banjos,

drums, diddle bows, mouthbows, Quilts, washtub bass, jugs, gongs, bells,

rattles, idiophones, and the lokoimni (a five-stringed harp). The Bantus had

the largest constituency in South Carolina and possibly in other areas of the

southeastern United States, including Alabama and Louisiana. Herskovits

noted that the cultural center of the Bantu in North America is in the South

Carolina Sea Islands off the Carolina coast.

Given the homogeneity of the Bantu culture and the strong similarities

among Bantu languages, this group no doubt influenced West African

groups of larger size. Also, since the Bantus were predominantly field

hands or were used in capacities that required little or no contact with

European Americans, they were not confronted with the same problems of

acculturationas West African domestic servants and artisans were.

However, the Mande had a greater influence on white American culture.

Coexisting in relative isolation from other groups, the Bantus were able to

maintain a strong sense of unity and to retain a cultural vitality that laid the

foundation for the development of African American culture.

AFRICAN CROPS TO THE NEW WORLD

Crops brought directly from Africa during the transatlantic slave trade

include rice, okra, tania, Blackeyed peas, and kidney and lima beans. They

were consumed by Africans on board the slave ships on the way to th

New World. Slavers collected local cultivated crops such as rice and yams,

and included dried beans, peas, wheat, shelled barley and biscuits to feed

the cargo.

African women prepared much of the food during the transatlantic voyage

as suggested by an entry from the journal of the ship Mary from Monday

June 20, 1796: “The Women Cleaning Rice and Grinding corn for corn

cakes.” These foods were mixed with a sauce of meat or fish, or with palm

oil. Once they survived the Middle Passage, the meals they consumed in

the plantation fields consisted of boiled yams, eddoes (Tania), okra,

callaloo, and plantain heavily seasoned with cayenne pepper and salt.

mainstreamof white American culture. This isolation worked to the

Bantus’ advantage in that it allowed their culture to escape acculturatio

and maintained their homogeneity. Bantu contributions to South Carolina

and Louisiana included not only wrought iron balconies, but also wood

carvings, basketry, weaving, clay-baked figurines, and pottery.

Cosmograms, grave designs and decorations, funeral practices, and the

wake are Bantu in origin. Bantu musical contributions include banjos,

drums, diddle bows, mouthbows, Quilts, washtub bass, jugs, gongs, bells,

rattles, idiophones, and the lokoimni (a five-stringed harp). The Bantus had

the largest constituency in South Carolina and possibly in other areas of the

southeastern United States, including Alabama and Louisiana. Herskovits

noted that the cultural center of the Bantu in North America is in the South

Carolina Sea Islands off the Carolina coast.

Given the homogeneity of the Bantu culture and the strong similarities

among Bantu languages, this group no doubt influenced West African

groups of larger size. Also, since the Bantus were predominantly field

hands or were used in capacities that required little or no contact with

European Americans, they were not confronted with the same problems of

acculturationas West African domestic servants and artisans were.

However, the Mande had a greater influence on white American culture.

Coexisting in relative isolation from other groups, the Bantus were able to

maintain a strong sense of unity and to retain a cultural vitality that laid the

foundation for the development of African American culture.

AFRICAN CROPS TO THE NEW WORLD

Crops brought directly from Africa during the transatlantic slave trade

include rice, okra, tania, Blackeyed peas, and kidney and lima beans. They

were consumed by Africans on board the slave ships on the way to th

New World. Slavers collected local cultivated crops such as rice and yams,

and included dried beans, peas, wheat, shelled barley and biscuits to feed

the cargo.

African women prepared much of the food during the transatlantic voyage

as suggested by an entry from the journal of the ship Mary from Monday

June 20, 1796: “The Women Cleaning Rice and Grinding corn for corn

cakes.” These foods were mixed with a sauce of meat or fish, or with palm

oil. Once they survived the Middle Passage, the meals they consumed in

the plantation fields consisted of boiled yams, eddoes (Tania), okra,

callaloo, and plantain heavily seasoned with cayenne pepper and salt.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Other crops brought from Africa included peanuts (ultimately from South

America), millet, sorghum, guinea melon, watermelon, yams (Dioscorea

cayanensis),and sesame (benne). These crops found their way into

American food ways and became part of the ingredients found in the

earliest cook books written by Southern Americans.

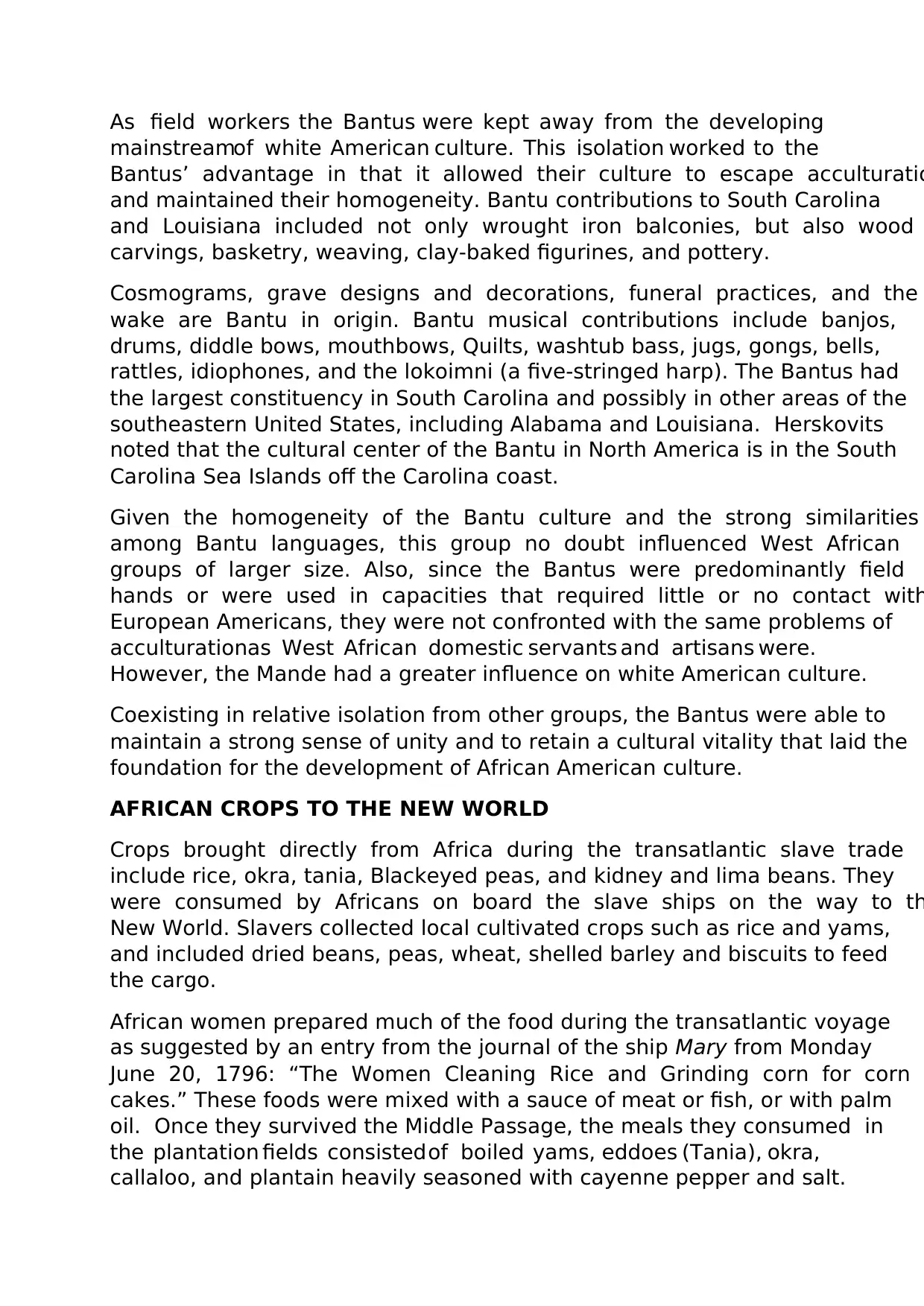

Genus, Species Common Name

Abelmoschus esculentus okra, guimbombo

Aracis hypogaea groundnut

Blighia spida ackee, aka, akee

Cajanus cajan Angola pea, pigeon pea

Cannabis sativa diamba, marijuana

Cassia italica Jamaican senna

Cola acuminate bichy tree

Cucumis anguria maroon cucumber

Dioscorea alata yam bacara

Dioscorea cayenensis yellow yam

Elaeis guineensis African oil palm

Monodora myristica nutmeg

Oryza glaberrima African rice

Phaseolus lunatus broad bean

Sesamun indicum benne seed

Sorghum vulgare guinea corn, wheat

William Ed Grime, Ethno-Botany of the Black Americans Algoniac, Mic

publications, 1970

A young physician, Sir Hans Sloane, living in the West Indies, found many

of these crops growing on the island of Jamaica as early as 1687. The

plants reached the mainland of North America either directly from Africa,

or came with enslaved Africans destined for North America and through

trade with the West Indies. These crops may have already found a home in

North America before Sloane's encounter. Eventually, however, these crops

America), millet, sorghum, guinea melon, watermelon, yams (Dioscorea

cayanensis),and sesame (benne). These crops found their way into

American food ways and became part of the ingredients found in the

earliest cook books written by Southern Americans.

Genus, Species Common Name

Abelmoschus esculentus okra, guimbombo

Aracis hypogaea groundnut

Blighia spida ackee, aka, akee

Cajanus cajan Angola pea, pigeon pea

Cannabis sativa diamba, marijuana

Cassia italica Jamaican senna

Cola acuminate bichy tree

Cucumis anguria maroon cucumber

Dioscorea alata yam bacara

Dioscorea cayenensis yellow yam

Elaeis guineensis African oil palm

Monodora myristica nutmeg

Oryza glaberrima African rice

Phaseolus lunatus broad bean

Sesamun indicum benne seed

Sorghum vulgare guinea corn, wheat

William Ed Grime, Ethno-Botany of the Black Americans Algoniac, Mic

publications, 1970

A young physician, Sir Hans Sloane, living in the West Indies, found many

of these crops growing on the island of Jamaica as early as 1687. The

plants reached the mainland of North America either directly from Africa,

or came with enslaved Africans destined for North America and through

trade with the West Indies. These crops may have already found a home in

North America before Sloane's encounter. Eventually, however, these crops

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

went from being eaten exclusively by Africans in North America to being in

white southern cuisine.

Blackeyed peas were first brought to the New World during the

transatlantic slave trade as food for slaves. They first arrived in Jamaic

around 1675, spreading throughout the West Indies, and finally reaching

Florida by 1700, North Carolina in 1738, and Virginia by 1775. Slave planter

William Byrd mentions Blackeyed peas in his writings in 1738. By the time

of the American Revolution, Blackeyed peas were firmly established in

America and a part of the cuisine.

George Washington wrote in a letter in 1791 that "pease" (Blackeyed peas)

were rarely grown in Virginia. In 1792 he brought 40 bushels of seeds for

planting on his plantation. Blackeyed peas became one of the most popular

food crops in the southern part of the United States. George Washingto

later referred to them as "callicance" and "cornfield peas," because of

early custom of planting them between the rows of field corn.

Okra arrived in the New World during the transatlantic slave trade in the

1600s. Okra, called gumbo in Africa, found exceptional popularity in New

Orleans. In French Louisiana, Creole cuisine and African cooking combined

to produce the unique cuisine of New Orleans. Gumbo is a popular stew, or

soup, in which okra is the main ingredient, thickened with powder from

sassafras leaves (gumbo filé). One observer in 1748 noted that thickene

soup was a delicacy liked by Blacks.

Okra was commonly used by the American white population before the

American Revolutionary War. Enslaved Africans used the young fruit that

contains the vegetable mucilage to eat after boiling. The leaves were a

used medicinally to make a softening cataplasm, and seeds were used

make a coffee substitute on the plantations of South Carolina. Okra wa

popular among women to produce abortion, by lubricating the uterine

passage with the slimy pods. In West Africa, women still use okra to

produce abortion, using the same method.

The next important crop to arrive to the United States by way of Africa is

the American peanut. The peanut is known by several names, including

groundnut, earth nut and ground peas. Two other words of African origin

for the peanut are Pindar and goober. Among other recorded sources of the

use of these African names, both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington

called peanuts peendar and Pindars (1794, 1798); the word was used before

the Revolutionary War. The word goober was used principally in the 19th

century. The period of its greatest popularity was the 1860s when the Civil

white southern cuisine.

Blackeyed peas were first brought to the New World during the

transatlantic slave trade as food for slaves. They first arrived in Jamaic

around 1675, spreading throughout the West Indies, and finally reaching

Florida by 1700, North Carolina in 1738, and Virginia by 1775. Slave planter

William Byrd mentions Blackeyed peas in his writings in 1738. By the time

of the American Revolution, Blackeyed peas were firmly established in

America and a part of the cuisine.

George Washington wrote in a letter in 1791 that "pease" (Blackeyed peas)

were rarely grown in Virginia. In 1792 he brought 40 bushels of seeds for

planting on his plantation. Blackeyed peas became one of the most popular

food crops in the southern part of the United States. George Washingto

later referred to them as "callicance" and "cornfield peas," because of

early custom of planting them between the rows of field corn.

Okra arrived in the New World during the transatlantic slave trade in the

1600s. Okra, called gumbo in Africa, found exceptional popularity in New

Orleans. In French Louisiana, Creole cuisine and African cooking combined

to produce the unique cuisine of New Orleans. Gumbo is a popular stew, or

soup, in which okra is the main ingredient, thickened with powder from

sassafras leaves (gumbo filé). One observer in 1748 noted that thickene

soup was a delicacy liked by Blacks.

Okra was commonly used by the American white population before the

American Revolutionary War. Enslaved Africans used the young fruit that

contains the vegetable mucilage to eat after boiling. The leaves were a

used medicinally to make a softening cataplasm, and seeds were used

make a coffee substitute on the plantations of South Carolina. Okra wa

popular among women to produce abortion, by lubricating the uterine

passage with the slimy pods. In West Africa, women still use okra to

produce abortion, using the same method.

The next important crop to arrive to the United States by way of Africa is

the American peanut. The peanut is known by several names, including

groundnut, earth nut and ground peas. Two other words of African origin

for the peanut are Pindar and goober. Among other recorded sources of the

use of these African names, both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington

called peanuts peendar and Pindars (1794, 1798); the word was used before

the Revolutionary War. The word goober was used principally in the 19th

century. The period of its greatest popularity was the 1860s when the Civil

War song "Goober Peas" was written. After the war the song’s lyrics were

attributed to "A Pindar" and its music to "P. Nutt."

The American peanut has an interestinghistory. While the peanut is

indigenous to South America as a crop, it was first brought to Africa b

Portuguese sailors and then back to Virginia from Africa by enslaved

Africans. The peanut was used to feed Africans crossing the Middle

Passage. One New World observer noted, "The first I ever saw of these

[peanuts] growing was the Negro's plantation who affirmed, that they grew

in great plenty in their country." In Africa, peanut stews, soups, and gravies

serve as an important part of any meal. Nut soups, however, in the

American South, although of African origin, and are no longer enjoyed by

the descendants of Africans, but rather are associated with Euro-Americans.

The peanut is a crop that George Washington Carver researched. From his

experimentshe found water, fats, oils, gums, resins, sugar, starches,

pectins, pentosans, and proteins. From these compounds he discovered

over 300 possible peanut products, including Jersey milk that led to the

production of butter and cheese. Among the 300 products arising from his

research were instant coffee, flour, face cream, bleach, synthetic rubber and

linoleum. Dr. Carver found rubbing peanut oil on the body helpful for

rejuvenating muscles. Mahatma Gandhi found that peanut milk, as well as

the soy bean formula Dr. Carver created for him, constituted a healthy part

of his diet.

Sesame first arrived in South Carolina from Africa by 1730. In 1730, a

Carolinian sent sesame along with sesame oil to London. This is an item of

considerable importance in Colonial America and England because table oil

was one of the products England hoped to obtain by colonizing the Ne

World. In order not to import olive oil for cooking, Britain encouraged

production of table oils by offering bounties on edible oils. By 1733, a book

on gardening published in London, noting the cultivation of the sesame

plant and its usefulness as a source of "sallet-oil." Enslaved Africans grew

sesame for uses other than its oil. Thomas Jefferson noted in the 1770s that

benne (another name for sesame) was eaten raw, toasted or boiled in soups

by African slaves. Jefferson also noted that enslaved Africans baked sesame

in breads, boiled in greens, and used it to enrich broth. Today sesame

used primarily as a bread topping.

African cooks in the "Big House" introduced their native African crops and

foods to the planters, thus becoming intermediary links in the melding of

African and European culinary cultures. The house servants, while learning

from the planters, also took African culinary taste into the Big House.

attributed to "A Pindar" and its music to "P. Nutt."

The American peanut has an interestinghistory. While the peanut is

indigenous to South America as a crop, it was first brought to Africa b

Portuguese sailors and then back to Virginia from Africa by enslaved

Africans. The peanut was used to feed Africans crossing the Middle

Passage. One New World observer noted, "The first I ever saw of these

[peanuts] growing was the Negro's plantation who affirmed, that they grew

in great plenty in their country." In Africa, peanut stews, soups, and gravies

serve as an important part of any meal. Nut soups, however, in the

American South, although of African origin, and are no longer enjoyed by

the descendants of Africans, but rather are associated with Euro-Americans.

The peanut is a crop that George Washington Carver researched. From his

experimentshe found water, fats, oils, gums, resins, sugar, starches,

pectins, pentosans, and proteins. From these compounds he discovered

over 300 possible peanut products, including Jersey milk that led to the

production of butter and cheese. Among the 300 products arising from his

research were instant coffee, flour, face cream, bleach, synthetic rubber and

linoleum. Dr. Carver found rubbing peanut oil on the body helpful for

rejuvenating muscles. Mahatma Gandhi found that peanut milk, as well as

the soy bean formula Dr. Carver created for him, constituted a healthy part

of his diet.

Sesame first arrived in South Carolina from Africa by 1730. In 1730, a

Carolinian sent sesame along with sesame oil to London. This is an item of

considerable importance in Colonial America and England because table oil

was one of the products England hoped to obtain by colonizing the Ne

World. In order not to import olive oil for cooking, Britain encouraged

production of table oils by offering bounties on edible oils. By 1733, a book

on gardening published in London, noting the cultivation of the sesame

plant and its usefulness as a source of "sallet-oil." Enslaved Africans grew

sesame for uses other than its oil. Thomas Jefferson noted in the 1770s that

benne (another name for sesame) was eaten raw, toasted or boiled in soups

by African slaves. Jefferson also noted that enslaved Africans baked sesame

in breads, boiled in greens, and used it to enrich broth. Today sesame

used primarily as a bread topping.

African cooks in the "Big House" introduced their native African crops and

foods to the planters, thus becoming intermediary links in the melding of

African and European culinary cultures. The house servants, while learning

from the planters, also took African culinary taste into the Big House.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.