COIT20249 Report: 3D Printing of Anatomical Teaching Resources

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|8

|7329

|189

Report

AI Summary

This report details the use of three-dimensional (3D) printing technology in producing anatomical teaching resources, addressing the challenges associated with traditional cadaver-based anatomy education. It discusses how 3D printing enables the creation of high-resolution, accurate color reproductions of prosected human cadavers and other anatomical specimens, using data from surface scanning or CT imaging. The report illustrates the application of 3D printing to produce models of negative spaces and contrast CT radiographic data using segmentation software, comparing the accuracy of printed specimens with original specimens. It highlights the advantages of this approach over plastination, including rapid production, scalability, and suitability for diverse teaching facilities, while also mitigating cultural and ethical issues related to cadaver specimens. The study addresses data input requirements, data processing logistics, qualitative and quantitative accuracy, and relative costs, ultimately demonstrating the potential of 3D printing to enhance anatomical sciences education.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

The Production of AnatomicalTeaching Resources Using

Three-Dimensional(3D) Printing Technology

Paul G. McMenamin,* Michelle R. Quayle, Colin R. McHenry, Justin W. Adams

Centre for Human Anatomy Education, Department of Anatomy and DevelopmentalBiology,

School of BiomedicalSciences, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University,

Clayton, Victoria, Australia

The teaching of anatomy has consistently been the subject of societalcontroversy,espe-

cially in the context of employing cadaveric materials in professionalmedicaland allied

health professionaltraining.The reduction in dissection-based teaching in medicaland

allied health professionaltraining programs has been in part due to the financial consid-

erations involved in maintaining bequest programs,accessing human cadavers and con-

cerns with health and safety considerations for students and staffexposed to formalin-

containing embalming fluids.This reportdetails how additive manufacturing or three-

dimensional(3D) printing allows the creation of reproductionsof prosected human

cadaver and other anatomicalspecimens that obviates many of the above issues.These

3D prints are high resolution,accurate color reproductions of prosections based on data

acquired by surface scanning or CT imaging.The application of 3D printing to produce

models of negative spaces,contrast CT radiographic data using segmentation software is

illustrated.The accuracy of printed specimens is compared with original specimens. This

alternativeapproach to producinganatomicallyaccuratereproductionsoffers many

advantages over plastination as it allows rapid production of multiple copies of any dis-

sected specimen,at any size scale and should be suitable for any teaching facility in any

country, thereby avoiding some of the cultural and ethical issues associated with cadaver

specimens either in an embalmed or plastinated form.Anat Sci Educ 00: 000–000.VC 2014

American Association of Anatomists.

Key words: gross anatomy education;medicaleducation;human anatomy;cadavers;

image processing;3D printing; rapid prototyping;additive manufacturing;anatomical

models

INTRODUCTION

Historically,the teaching of human anatomy in medicaland

allied health curricula using cadavershas been a source of

significantsocial controversy,rivaling the mostcontentious

medico-legaland ethicaldebates across other scientific disci-

plines.One of the major recurring controversies in anatomy

education is whether dissection of cadavers is stilla relevant

and appropriate component of a modern medicalundergrad-

uate training (Parker,2002;Winkelmann,2007;Korf et al.,

2008; Chambersand Emlyn-Jones,2009; Heetun, 2009).

Many hold the view that cadaveric dissection is the key com-

ponentof teaching anatomy (Ramsey-Stewartet al., 2010;

Sugand et al., 2010) and the consequences for trainees/practi-

tioners not having competentanatomicalknowledgehas

recently been emphasized (Johnson et al.,2012).In contrast,

some institutionsin the United Kingdom and Europe have

abandoned dissection-based learning (McLachlan and Patten,

2006) and in the United States many rely on combinations of

prosection and dissection (Drake et al.,2009).The reduction

in dissection-based teaching in medicaland allied health pro-

fessionaltraining programs in developed countries has been

in part due to financialconsiderations involved in maintain-

ing a cadaver bequestprogram,accessing cadavers and the

cost of maintaining modern laboratories and storage facilities

AdditionalSupporting Information may be found in the online version of

this article.

*Correspondence to:Prof. Paul G. McMenamin,Department of Anat-

omy and DevelopmentalBiology, Monash University,Building 13C,

Wellington Rd, Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia.

E-mail: paul.mcmenamin@monash.edu

Received 20 January 2014;Revised 14 May 2014;Accepted 12 June

2014.

Published online 00 Month 2014 in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/ase.1475

VC 2014 American Association of Anatomists

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 Anat SciEduc 00:00–00 (2014)

DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLE

Three-Dimensional(3D) Printing Technology

Paul G. McMenamin,* Michelle R. Quayle, Colin R. McHenry, Justin W. Adams

Centre for Human Anatomy Education, Department of Anatomy and DevelopmentalBiology,

School of BiomedicalSciences, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University,

Clayton, Victoria, Australia

The teaching of anatomy has consistently been the subject of societalcontroversy,espe-

cially in the context of employing cadaveric materials in professionalmedicaland allied

health professionaltraining.The reduction in dissection-based teaching in medicaland

allied health professionaltraining programs has been in part due to the financial consid-

erations involved in maintaining bequest programs,accessing human cadavers and con-

cerns with health and safety considerations for students and staffexposed to formalin-

containing embalming fluids.This reportdetails how additive manufacturing or three-

dimensional(3D) printing allows the creation of reproductionsof prosected human

cadaver and other anatomicalspecimens that obviates many of the above issues.These

3D prints are high resolution,accurate color reproductions of prosections based on data

acquired by surface scanning or CT imaging.The application of 3D printing to produce

models of negative spaces,contrast CT radiographic data using segmentation software is

illustrated.The accuracy of printed specimens is compared with original specimens. This

alternativeapproach to producinganatomicallyaccuratereproductionsoffers many

advantages over plastination as it allows rapid production of multiple copies of any dis-

sected specimen,at any size scale and should be suitable for any teaching facility in any

country, thereby avoiding some of the cultural and ethical issues associated with cadaver

specimens either in an embalmed or plastinated form.Anat Sci Educ 00: 000–000.VC 2014

American Association of Anatomists.

Key words: gross anatomy education;medicaleducation;human anatomy;cadavers;

image processing;3D printing; rapid prototyping;additive manufacturing;anatomical

models

INTRODUCTION

Historically,the teaching of human anatomy in medicaland

allied health curricula using cadavershas been a source of

significantsocial controversy,rivaling the mostcontentious

medico-legaland ethicaldebates across other scientific disci-

plines.One of the major recurring controversies in anatomy

education is whether dissection of cadavers is stilla relevant

and appropriate component of a modern medicalundergrad-

uate training (Parker,2002;Winkelmann,2007;Korf et al.,

2008; Chambersand Emlyn-Jones,2009; Heetun, 2009).

Many hold the view that cadaveric dissection is the key com-

ponentof teaching anatomy (Ramsey-Stewartet al., 2010;

Sugand et al., 2010) and the consequences for trainees/practi-

tioners not having competentanatomicalknowledgehas

recently been emphasized (Johnson et al.,2012).In contrast,

some institutionsin the United Kingdom and Europe have

abandoned dissection-based learning (McLachlan and Patten,

2006) and in the United States many rely on combinations of

prosection and dissection (Drake et al.,2009).The reduction

in dissection-based teaching in medicaland allied health pro-

fessionaltraining programs in developed countries has been

in part due to financialconsiderations involved in maintain-

ing a cadaver bequestprogram,accessing cadavers and the

cost of maintaining modern laboratories and storage facilities

AdditionalSupporting Information may be found in the online version of

this article.

*Correspondence to:Prof. Paul G. McMenamin,Department of Anat-

omy and DevelopmentalBiology, Monash University,Building 13C,

Wellington Rd, Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia.

E-mail: paul.mcmenamin@monash.edu

Received 20 January 2014;Revised 14 May 2014;Accepted 12 June

2014.

Published online 00 Month 2014 in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/ase.1475

VC 2014 American Association of Anatomists

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 Anat SciEduc 00:00–00 (2014)

DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLE

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

that comply with current health and safety considerations for

studentsand staff is also a financial burden (AAA, 2012;

Raja and Sultana, 2012). Furthermore, in some countries cul-

tural and ethicalconsiderations,and the rural location of

some institutions,mean thatmany medicalschoolsor col-

legesinvolved in educating doctorsand other allied disci-

plines have difficulties accessing human cadaver specimens.

Many medicalschoolsand anatomydepartmentshave

soughtalternativesor adjunctsto cadaver-based instruction

through the use ofalternative techniques including plastina-

tion (von Hagenset al., 1979), two-dimensional(2D) and

three-dimensional(3D) imaging (Estevez etal., 2010), and

body painting (McMenamin, 2008).

Rapid prototyping via 3D printing is a rapidly expanding

technology that is now a critical part of the iterative design pro-

cess in engineering,producing physicalmodels quickly,easily

and inexpensively from computer-aided design (CAD)and

other digital data (Pham and Dimov, 2001). Additive manufac-

turing or 3D printing is often promoted as one of the most sig-

nificant technologicaladvancesin our modern era.In the

medical and health care arena, 3D printing was identified as a

technology with great promise as early as 1997 (McGurk et al.,

1997) and has already had an impact in the domain of oromax-

illary and facial surgery (Isolan et al., 2007; Cohen et al., 2009)

and orthopedic surgery (Esses et al., 2011) by allowing the pro-

duction of bespoke prefabricated bone models for presurgical

planning or the creation of patient-specificprosthesesfor

implantation (Tam et al., 2013), surgical simulation (Monfared

et al.,2012,Waran et al.,2013) or as a patient educational

tools (see review, Rengier et al., 2010). The use of 3D printing

in forensic medicine to create models of bone fractures, vessels,

cardiac infarctions, ruptured organs and bite-mark wounds has

also been reported (Ebert et al., 2011). As 3D prints can be gen-

erated from medical CT/MRI data, it is logically possible to use

3D print outs from common imaging studies to augment the

teaching of topographic and applied clinical anatomy.

Some issuesremain unresolved regarding the application

of this emerging technology foranatomicalscienceseduca-

tion. In this study we wanted to addressthe following

questions:

(1) What data inputsare required orcan be potentially

utilized? (2) What are the logistics of data processing and 3D

print production? (3) What is the qualitative and quantitative

accuracy of the 3D prints compared with the originalspeci-

mens?(4) What are the relativecostswhen compared to

alternatives?

METHODS

Image Data Acquisition

The precise threshold ofresolution required for 3D printed

models to be usefulfor haptic teaching aids is not presently

known, but the majority of3D printers are capable of100

mm isometric resolution,and latestgeneration 3D scanning

equipment(such as fixed or hand-held surface scanners)are

capableof comparable(or higher)resolution during data

acquisition.A modern 64 slice CT scanner typically involves

lower resolutions;for example a CT scan of a limb segment

would produce pixel sizes (i.e., X and Y resolutions) of 0.15–

0.5 mm and interslice distances (Z resolution) of 0.4–1.0 mm

(Kalender,2006).Thus as long as printer resolution is higher

than the scan resolution,3D printing will not resultin any

loss of accuracy.For initial testing of3D printing as a tool

for anatomy teaching and learning,we aimed to produce a

3D model that displayed the surface features visible in a pro-

sected specimen. To obtain high quality 3D printed models of

cadaver specimens it is vitalthat the originalcadaver prosec-

tion be of high quality.For the initial“proof of concept” we

scanned a prosected upperlimb (Fig. 1A), using a Philips

Brilliance64 CT scanner (Olympic Park Radiology, Mel-

bourne,Australia).The scannerfield of view was set to

150 mm,giving a per-slice pixelsize of 0.195 mm,and slice

distance wasset to 0.4 mm (near maximalresolutionsfor

this scanner).Using these parameters on a fixed prosection

we were essentially using the CT scanner for the purpose of

digitizing 3D surface geometry only,and either soft- or hard-

tissue optimized algorithms are suitable for subsequent gener-

ation of the 3D data.

As many interesting anatomicalfeaturesare fluid or air

filled spaces(e.g.,ventricles,paranasalair sinuses,vessels,

heart chambers) we also provide three examples of “negative

spaces” to demonstrate the capability of this method for visu-

alizing such anatomicalfeaturesof interestand producing

haptic models.First, to obtain a print of mammalian cranial

sinuses we scanned an adult common warthog (Phacochoerus

africanus;TM 738) specimen from theDitsong National

Museum NaturalHistory Departmentof Vertebrates (Preto-

ria, South Africa) collection usinga Phillips Brilliance 6

180P3 CT Scanner (Philips Healthcare,Best, The Nether-

lands)with a per-slice pixelsize of 0.5mm and a slice dis-

tance of 1.0 mm. Second, to prove 3D vascular data could be

printed contrast CT coronary angiogram data set was chosen

for segmentation.Third, to obtain a printof a mammalian

cochlea and vestibularapparatusof the dried skull of an

adult king colobus monkey (Colobus polykomos;ZA 1038)

was scanned using the Nikon XT H 225 ST micro-focus X-

ray tomography systems (Nikon Metrology, Leuven, Belgium)

housed atthe South African NationalCentre for Radiogra-

phy and Tomography thatobtained an isometric voxel(3D

pixel) size of 66 mm.

Image Processing

The CT data output for the upperlimb prosection wasin

DICOM (Digital Imaging and COmmunications in Medicine)

image stack of 1,343 slices. To generate a file that can be 3D

printed requiresspecialized 3D imageprocessing software

that can import a DICOM stack. Various ‘segmentation’

tools are then used to produce a 3D isosurface that is essen-

tially a 3D visualization of segmented structures. In this study

Avizo software,version 7.0,for 3D analysis of scientific and

industrial data (Visualization Science Group/FEI Comp,

M erignac Cedex,France)was chosen.As only the surface

features ofthe specimen were initially ofinterestsegmenta-

tion required only thatvoxels in the datasetwith an X-ray

density close to orhigherthan thatof water be separated

from voxels with a density corresponding to air.Automatic

thresholding tools(which segmentvoxels based upon CT

attenuation values,i.e., Hounsfield numbers)are a fastand

effective means of achieving this outcome. We found it valua-

ble to use low-density foam to hold the specimen clear of the

scanning table allowing the prosected specimen to be seg-

mented and digitally separated from the scanning table.The

scan was cropped in the long axis so that only the hand and

wrist were included in the final isosurface (Fig. 1B). The reso-

lutions and reconstruction algorithm used in the scan allow

2 McMenamin et al.

studentsand staff is also a financial burden (AAA, 2012;

Raja and Sultana, 2012). Furthermore, in some countries cul-

tural and ethicalconsiderations,and the rural location of

some institutions,mean thatmany medicalschoolsor col-

legesinvolved in educating doctorsand other allied disci-

plines have difficulties accessing human cadaver specimens.

Many medicalschoolsand anatomydepartmentshave

soughtalternativesor adjunctsto cadaver-based instruction

through the use ofalternative techniques including plastina-

tion (von Hagenset al., 1979), two-dimensional(2D) and

three-dimensional(3D) imaging (Estevez etal., 2010), and

body painting (McMenamin, 2008).

Rapid prototyping via 3D printing is a rapidly expanding

technology that is now a critical part of the iterative design pro-

cess in engineering,producing physicalmodels quickly,easily

and inexpensively from computer-aided design (CAD)and

other digital data (Pham and Dimov, 2001). Additive manufac-

turing or 3D printing is often promoted as one of the most sig-

nificant technologicaladvancesin our modern era.In the

medical and health care arena, 3D printing was identified as a

technology with great promise as early as 1997 (McGurk et al.,

1997) and has already had an impact in the domain of oromax-

illary and facial surgery (Isolan et al., 2007; Cohen et al., 2009)

and orthopedic surgery (Esses et al., 2011) by allowing the pro-

duction of bespoke prefabricated bone models for presurgical

planning or the creation of patient-specificprosthesesfor

implantation (Tam et al., 2013), surgical simulation (Monfared

et al.,2012,Waran et al.,2013) or as a patient educational

tools (see review, Rengier et al., 2010). The use of 3D printing

in forensic medicine to create models of bone fractures, vessels,

cardiac infarctions, ruptured organs and bite-mark wounds has

also been reported (Ebert et al., 2011). As 3D prints can be gen-

erated from medical CT/MRI data, it is logically possible to use

3D print outs from common imaging studies to augment the

teaching of topographic and applied clinical anatomy.

Some issuesremain unresolved regarding the application

of this emerging technology foranatomicalscienceseduca-

tion. In this study we wanted to addressthe following

questions:

(1) What data inputsare required orcan be potentially

utilized? (2) What are the logistics of data processing and 3D

print production? (3) What is the qualitative and quantitative

accuracy of the 3D prints compared with the originalspeci-

mens?(4) What are the relativecostswhen compared to

alternatives?

METHODS

Image Data Acquisition

The precise threshold ofresolution required for 3D printed

models to be usefulfor haptic teaching aids is not presently

known, but the majority of3D printers are capable of100

mm isometric resolution,and latestgeneration 3D scanning

equipment(such as fixed or hand-held surface scanners)are

capableof comparable(or higher)resolution during data

acquisition.A modern 64 slice CT scanner typically involves

lower resolutions;for example a CT scan of a limb segment

would produce pixel sizes (i.e., X and Y resolutions) of 0.15–

0.5 mm and interslice distances (Z resolution) of 0.4–1.0 mm

(Kalender,2006).Thus as long as printer resolution is higher

than the scan resolution,3D printing will not resultin any

loss of accuracy.For initial testing of3D printing as a tool

for anatomy teaching and learning,we aimed to produce a

3D model that displayed the surface features visible in a pro-

sected specimen. To obtain high quality 3D printed models of

cadaver specimens it is vitalthat the originalcadaver prosec-

tion be of high quality.For the initial“proof of concept” we

scanned a prosected upperlimb (Fig. 1A), using a Philips

Brilliance64 CT scanner (Olympic Park Radiology, Mel-

bourne,Australia).The scannerfield of view was set to

150 mm,giving a per-slice pixelsize of 0.195 mm,and slice

distance wasset to 0.4 mm (near maximalresolutionsfor

this scanner).Using these parameters on a fixed prosection

we were essentially using the CT scanner for the purpose of

digitizing 3D surface geometry only,and either soft- or hard-

tissue optimized algorithms are suitable for subsequent gener-

ation of the 3D data.

As many interesting anatomicalfeaturesare fluid or air

filled spaces(e.g.,ventricles,paranasalair sinuses,vessels,

heart chambers) we also provide three examples of “negative

spaces” to demonstrate the capability of this method for visu-

alizing such anatomicalfeaturesof interestand producing

haptic models.First, to obtain a print of mammalian cranial

sinuses we scanned an adult common warthog (Phacochoerus

africanus;TM 738) specimen from theDitsong National

Museum NaturalHistory Departmentof Vertebrates (Preto-

ria, South Africa) collection usinga Phillips Brilliance 6

180P3 CT Scanner (Philips Healthcare,Best, The Nether-

lands)with a per-slice pixelsize of 0.5mm and a slice dis-

tance of 1.0 mm. Second, to prove 3D vascular data could be

printed contrast CT coronary angiogram data set was chosen

for segmentation.Third, to obtain a printof a mammalian

cochlea and vestibularapparatusof the dried skull of an

adult king colobus monkey (Colobus polykomos;ZA 1038)

was scanned using the Nikon XT H 225 ST micro-focus X-

ray tomography systems (Nikon Metrology, Leuven, Belgium)

housed atthe South African NationalCentre for Radiogra-

phy and Tomography thatobtained an isometric voxel(3D

pixel) size of 66 mm.

Image Processing

The CT data output for the upperlimb prosection wasin

DICOM (Digital Imaging and COmmunications in Medicine)

image stack of 1,343 slices. To generate a file that can be 3D

printed requiresspecialized 3D imageprocessing software

that can import a DICOM stack. Various ‘segmentation’

tools are then used to produce a 3D isosurface that is essen-

tially a 3D visualization of segmented structures. In this study

Avizo software,version 7.0,for 3D analysis of scientific and

industrial data (Visualization Science Group/FEI Comp,

M erignac Cedex,France)was chosen.As only the surface

features ofthe specimen were initially ofinterestsegmenta-

tion required only thatvoxels in the datasetwith an X-ray

density close to orhigherthan thatof water be separated

from voxels with a density corresponding to air.Automatic

thresholding tools(which segmentvoxels based upon CT

attenuation values,i.e., Hounsfield numbers)are a fastand

effective means of achieving this outcome. We found it valua-

ble to use low-density foam to hold the specimen clear of the

scanning table allowing the prosected specimen to be seg-

mented and digitally separated from the scanning table.The

scan was cropped in the long axis so that only the hand and

wrist were included in the final isosurface (Fig. 1B). The reso-

lutions and reconstruction algorithm used in the scan allow

2 McMenamin et al.

visualization of even small nerves and vessels. The 3D isosur-

face is then exported as a 3D stereolithographyformat

(.STL), virtual reality modeling language (.VRML)or poly-

gon file format(.PLY) file; these are common formats that

can be read by the 3D printer’sdriver software.A similar

method wasapplied to the scansof both the warthog and

monkey, where the voxel attenuation values for the structures

of interest(air-filled spaces)were also wellseparated from

the values ofthe surrounding bone tissue and segmentation

was largely undertaken using automaticthresholding with

some manual editing. Clearly CT data does not contain color

information and as our first priority was to produce accurate

and valuable replicas of prosections we considered a number

of image processing software packages thatwould allow us

to import and ‘paint’the 3D digital file prior to printing.

After severaltrials of software packages3D-Coat, version

3.3, (Kompaniya Pilgway Studio,Ukraine)was chosen.One

advantage ofthe digitalpainting approach is that,once the

anatomicalfeatures have been highlighted in different colors,

a range of color maps can be created that either resemble the

dull tones of the originalprosection specimen or use brighter

colors to produce a more vivid teaching tool (Fig. 1C).

Three-DimensionalPrinting

There are many types of3D printers available which use a

variety ofmedia,substrates,and printing techniques.A 3D

Systems (formerly Z Corporation) Z650 printer (3D Systems,

Rock Hill, SC) was used for some of the prints in this study.

This is a powder infiltration printerthat can use different

combinationsof colored bindersto print in color with a

claimed palette of 390,000 color shades, similar to a conven-

tional ink jet printer. The Z650 has a large build tray (254 3

381 3 203 mm3) with a build speed of 28 mm/hour,which

makes it a suitable size for printing many human anatomical

specimens.The final hand model(Fig. 1D) took 3 hours to

print with a slice thickness of 0.1 mm.

Quantitative measurements.Measurementswere taken

from specimens and printout concurrently using Vernier cali-

pers. For the wrist/hand shown in Figure 1, the specimen and

the printout were aligned and four equivalent transverse sec-

tions of each were established; these were located at (approx-

imately) the distal radioulnar joint, the carpometacarpal

joints, the metacarpophalangealjoints, and the proximal

interphalangealjoints (Fig.1 Supporting Information).Two

typesof measurementwere taken:transversediametersof

longitudinalstructures atthe four cross sections,and linear

distancesbetween reliably distinguishable landmarks.Error

was calculated as the difference between the recorded mea-

surement for the printout and the specimen.Percentage error

was calculated as the error divided by the mean of the print-

out and specimen measurements.

Repeatability.A repeatability study wasperformed to

assess both the fidelity ofmeasurements derived from a 3D

print to those obtained from the originalobject and the con-

sistency ofmeasurements across multiple 3D printed repro-

ductions of the objects.As an example for this study,a right

maxillary tooth row of an extant African bovid (klipspringer;

Oreotragus oreotragus)from our comparative anatomy col-

lections was selected that preserved six premolars and molars

(Fig. 2 Supporting Information) that would allow for

Figure 1.

Prosection of the hand and wrist with 3D images and 3D printed model.(A) Image of CT-scanned prosection of hand and wrist;(B) The 3D computer image is

constructed from the CT data (in this case, exported from the scanner workstation in DICOM format) using image processing software (e.g., Amira, Avizo, Mimics

Simpleware,3D Slicer),which creates a stereolithography file (.STL);(C) Because CT scan does not provide information on color,anatomically realistic colors can

be added using a package such as 3D Coat; (D) The colored STL file can then be printed in full color as a 3D copy of the original prosection. Scale bar 5 10 cm.

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 3

face is then exported as a 3D stereolithographyformat

(.STL), virtual reality modeling language (.VRML)or poly-

gon file format(.PLY) file; these are common formats that

can be read by the 3D printer’sdriver software.A similar

method wasapplied to the scansof both the warthog and

monkey, where the voxel attenuation values for the structures

of interest(air-filled spaces)were also wellseparated from

the values ofthe surrounding bone tissue and segmentation

was largely undertaken using automaticthresholding with

some manual editing. Clearly CT data does not contain color

information and as our first priority was to produce accurate

and valuable replicas of prosections we considered a number

of image processing software packages thatwould allow us

to import and ‘paint’the 3D digital file prior to printing.

After severaltrials of software packages3D-Coat, version

3.3, (Kompaniya Pilgway Studio,Ukraine)was chosen.One

advantage ofthe digitalpainting approach is that,once the

anatomicalfeatures have been highlighted in different colors,

a range of color maps can be created that either resemble the

dull tones of the originalprosection specimen or use brighter

colors to produce a more vivid teaching tool (Fig. 1C).

Three-DimensionalPrinting

There are many types of3D printers available which use a

variety ofmedia,substrates,and printing techniques.A 3D

Systems (formerly Z Corporation) Z650 printer (3D Systems,

Rock Hill, SC) was used for some of the prints in this study.

This is a powder infiltration printerthat can use different

combinationsof colored bindersto print in color with a

claimed palette of 390,000 color shades, similar to a conven-

tional ink jet printer. The Z650 has a large build tray (254 3

381 3 203 mm3) with a build speed of 28 mm/hour,which

makes it a suitable size for printing many human anatomical

specimens.The final hand model(Fig. 1D) took 3 hours to

print with a slice thickness of 0.1 mm.

Quantitative measurements.Measurementswere taken

from specimens and printout concurrently using Vernier cali-

pers. For the wrist/hand shown in Figure 1, the specimen and

the printout were aligned and four equivalent transverse sec-

tions of each were established; these were located at (approx-

imately) the distal radioulnar joint, the carpometacarpal

joints, the metacarpophalangealjoints, and the proximal

interphalangealjoints (Fig.1 Supporting Information).Two

typesof measurementwere taken:transversediametersof

longitudinalstructures atthe four cross sections,and linear

distancesbetween reliably distinguishable landmarks.Error

was calculated as the difference between the recorded mea-

surement for the printout and the specimen.Percentage error

was calculated as the error divided by the mean of the print-

out and specimen measurements.

Repeatability.A repeatability study wasperformed to

assess both the fidelity ofmeasurements derived from a 3D

print to those obtained from the originalobject and the con-

sistency ofmeasurements across multiple 3D printed repro-

ductions of the objects.As an example for this study,a right

maxillary tooth row of an extant African bovid (klipspringer;

Oreotragus oreotragus)from our comparative anatomy col-

lections was selected that preserved six premolars and molars

(Fig. 2 Supporting Information) that would allow for

Figure 1.

Prosection of the hand and wrist with 3D images and 3D printed model.(A) Image of CT-scanned prosection of hand and wrist;(B) The 3D computer image is

constructed from the CT data (in this case, exported from the scanner workstation in DICOM format) using image processing software (e.g., Amira, Avizo, Mimics

Simpleware,3D Slicer),which creates a stereolithography file (.STL);(C) Because CT scan does not provide information on color,anatomically realistic colors can

be added using a package such as 3D Coat; (D) The colored STL file can then be printed in full color as a 3D copy of the original prosection. Scale bar 5 10 cm.

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 3

standard dentalmetricsto be acquired (overallmesiodistal

length and overallbuccolingualwidth; Janis, 1988).A sur-

face mesh ofthe maxillary dentition was captured using an

Artec SpiderTM hand-held 3D scanner (Artec Group,Luxen-

bourg)with a stated resolution of0.1 mm and accuracy up

to 0.03 mm. The resulting STL (STereoLithography)mesh

was imported into the 3D modelling software package Rhi-

noceros 3D,version 5.0 (Robert McNeel& Associates,Seat-

tle, WA) to merge the maxillary surfacewithin a solid

platform and then five copies of the final mesh (Maxilla 1–5)

were printed using the Z650 printer at 100% scaling (Fig.2

Supporting Information).

The originalspecimen of the maxillary tooth row and all

five 3D printed reproductions were measured using Mitutoyo

500 series calipers (Mitutoyo America,Aurora,IL) with pre-

cision of 0.01 mm and accuracy of0.02 mm.The dentition

of the originaland each printed specimen was measured by

one of the authors(J.W.A.) five timesover the span of a

week (average intervalof 24 hours between specimen meas-

urements) to establish a range of intraobserver error for each

dentalmeasurement.These data were used fora seriesof

intraclasscorrelation coefficients(ICC) calculated in SPSS

statisticalpackage,version 20.0 (IBM SPSS,Chicago,IL) to

assessthe intraobserverreliability ofthe repeated measure-

ments on the original and each of the printed maxillary denti-

tions.In addition,the calculated mean measurements for the

original and reproductions was used to calculate concordance

correlation coefficients (Lin,1989, 2000)to assess the reli-

ability of the 3D printed reproductions againstthe original

maxillary dentition.

RESULTS

Three-dimensionalprinting ofprosected specimens based on

CT data sets produced highly realistic 3D replicas in which

even smallnerves and vessels could be readily distinguished

(Fig. 1D). In addition printing ofnegative space such as air

sinusesand coronary vesselssegmented from CT data sets

(some with contrastmedia) was as anatomically accurate as

the originalclinicalradiologicaldata (Fig.2). Scaling up or

scaling down in size ofthe 3D prints is possible and pro-

duced highly satisfactory replicas of dissections and negative

space prints (Fig. 3). This is particularly valuable if the origi-

nal specimen is larger than the build tray ofthe printer in

which case anothersolution is to print large specimensin

portions that can be joined manually together (Fig. 3A).

Quantitative evaluation of 3D prints in comparison to the

original prosection showed thatstructuresabove 10 mm

were accurate in size with a mean absolute error of 0.32 mm

(variance of0.054 mm);mean percentage error was 1.29%

(variance 0.02%). The error increased when structures below

10 mm were measured (mean error,0.53 mm; variance

0.097 mm;mean percentage error,14.52%,variance 8.58%)

or below 4 mm (mean error 0.46,variance 0.093;mean per-

centageerror 17.92%, variance1.52%). Viewed continu-

ously, the percentageerror has a strong negativepower

relationship with structuresize and the smallerstructures

more affected by errorincludethe terminalvessels,nerve

branches,and tendons in the hand (Fig.3 Supporting Infor-

mation).Two factorslikely accountfor the increased error

for smaller structures:caliper measurementshave larger

errors at smaller sizes;but the resolution of the imaging pro-

cess and printer output is also important.

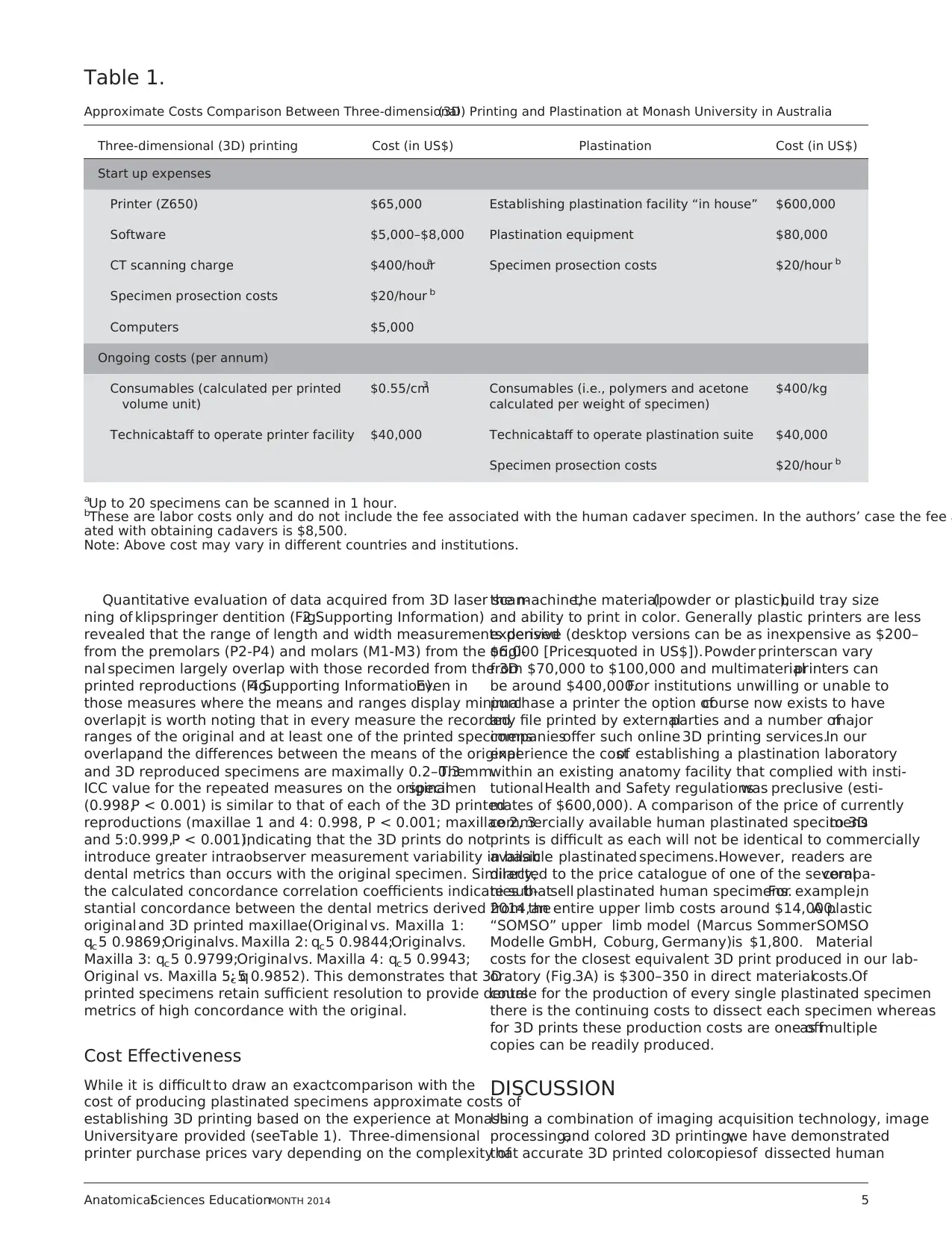

Figure 2.

Examples of 3D prints of negative spaces.(A) segmented and computer gener-

ated reconstructed image ofair sinuses in warthog skull;(B) 3D print of the

air sinuses alone;(C) contrast CT of heart and ascending aorta with coronary

arteries from which the data was extracted via segmentation and rendered into

a 3D file and printed (D). Scale bar 5 1 cm.

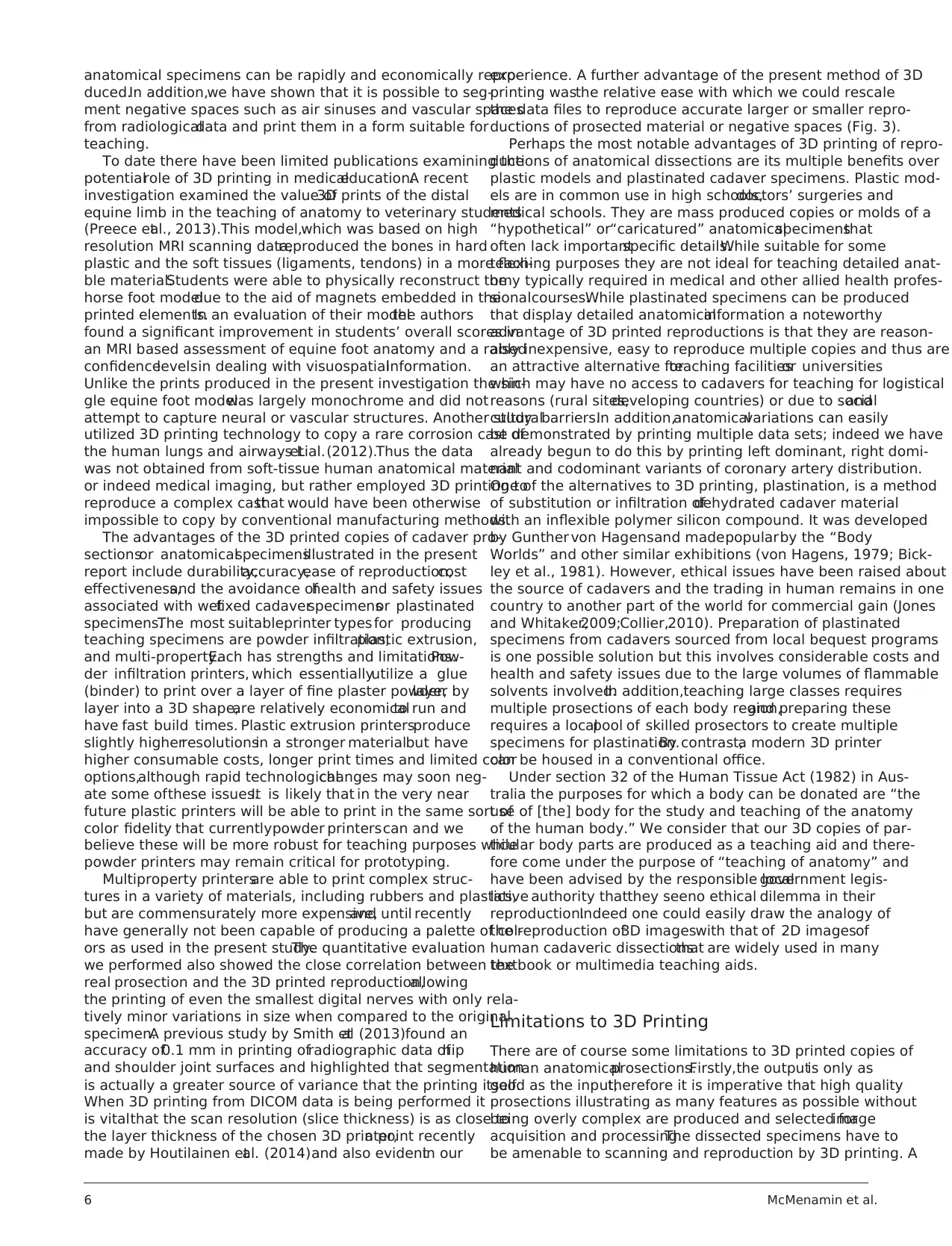

Figure 3.

Example of scaling up or scaling down a 3D print. (A) A full size upper limb prosection shown; (B) reduction at 50%; (C) reduction at 25%; (D) the inner ear of a

colobus monkey derived from segmented data extracted from a microCT data obtained from a dried skull at full size; (E) 500% enlargement of the same specim

4 McMenamin et al.

length and overallbuccolingualwidth; Janis, 1988).A sur-

face mesh ofthe maxillary dentition was captured using an

Artec SpiderTM hand-held 3D scanner (Artec Group,Luxen-

bourg)with a stated resolution of0.1 mm and accuracy up

to 0.03 mm. The resulting STL (STereoLithography)mesh

was imported into the 3D modelling software package Rhi-

noceros 3D,version 5.0 (Robert McNeel& Associates,Seat-

tle, WA) to merge the maxillary surfacewithin a solid

platform and then five copies of the final mesh (Maxilla 1–5)

were printed using the Z650 printer at 100% scaling (Fig.2

Supporting Information).

The originalspecimen of the maxillary tooth row and all

five 3D printed reproductions were measured using Mitutoyo

500 series calipers (Mitutoyo America,Aurora,IL) with pre-

cision of 0.01 mm and accuracy of0.02 mm.The dentition

of the originaland each printed specimen was measured by

one of the authors(J.W.A.) five timesover the span of a

week (average intervalof 24 hours between specimen meas-

urements) to establish a range of intraobserver error for each

dentalmeasurement.These data were used fora seriesof

intraclasscorrelation coefficients(ICC) calculated in SPSS

statisticalpackage,version 20.0 (IBM SPSS,Chicago,IL) to

assessthe intraobserverreliability ofthe repeated measure-

ments on the original and each of the printed maxillary denti-

tions.In addition,the calculated mean measurements for the

original and reproductions was used to calculate concordance

correlation coefficients (Lin,1989, 2000)to assess the reli-

ability of the 3D printed reproductions againstthe original

maxillary dentition.

RESULTS

Three-dimensionalprinting ofprosected specimens based on

CT data sets produced highly realistic 3D replicas in which

even smallnerves and vessels could be readily distinguished

(Fig. 1D). In addition printing ofnegative space such as air

sinusesand coronary vesselssegmented from CT data sets

(some with contrastmedia) was as anatomically accurate as

the originalclinicalradiologicaldata (Fig.2). Scaling up or

scaling down in size ofthe 3D prints is possible and pro-

duced highly satisfactory replicas of dissections and negative

space prints (Fig. 3). This is particularly valuable if the origi-

nal specimen is larger than the build tray ofthe printer in

which case anothersolution is to print large specimensin

portions that can be joined manually together (Fig. 3A).

Quantitative evaluation of 3D prints in comparison to the

original prosection showed thatstructuresabove 10 mm

were accurate in size with a mean absolute error of 0.32 mm

(variance of0.054 mm);mean percentage error was 1.29%

(variance 0.02%). The error increased when structures below

10 mm were measured (mean error,0.53 mm; variance

0.097 mm;mean percentage error,14.52%,variance 8.58%)

or below 4 mm (mean error 0.46,variance 0.093;mean per-

centageerror 17.92%, variance1.52%). Viewed continu-

ously, the percentageerror has a strong negativepower

relationship with structuresize and the smallerstructures

more affected by errorincludethe terminalvessels,nerve

branches,and tendons in the hand (Fig.3 Supporting Infor-

mation).Two factorslikely accountfor the increased error

for smaller structures:caliper measurementshave larger

errors at smaller sizes;but the resolution of the imaging pro-

cess and printer output is also important.

Figure 2.

Examples of 3D prints of negative spaces.(A) segmented and computer gener-

ated reconstructed image ofair sinuses in warthog skull;(B) 3D print of the

air sinuses alone;(C) contrast CT of heart and ascending aorta with coronary

arteries from which the data was extracted via segmentation and rendered into

a 3D file and printed (D). Scale bar 5 1 cm.

Figure 3.

Example of scaling up or scaling down a 3D print. (A) A full size upper limb prosection shown; (B) reduction at 50%; (C) reduction at 25%; (D) the inner ear of a

colobus monkey derived from segmented data extracted from a microCT data obtained from a dried skull at full size; (E) 500% enlargement of the same specim

4 McMenamin et al.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Quantitative evaluation of data acquired from 3D laser scan-

ning of klipspringer dentition (Fig.2 Supporting Information)

revealed that the range of length and width measurements derived

from the premolars (P2-P4) and molars (M1-M3) from the origi-

nal specimen largely overlap with those recorded from the 3D

printed reproductions (Fig.4 Supporting Information).Even in

those measures where the means and ranges display minimal

overlap,it is worth noting that in every measure the recorded

ranges of the original and at least one of the printed specimens

overlap;and the differences between the means of the original

and 3D reproduced specimens are maximally 0.2–0.3 mm.The

ICC value for the repeated measures on the originalspecimen

(0.998,P < 0.001) is similar to that of each of the 3D printed

reproductions (maxillae 1 and 4: 0.998, P < 0.001; maxillae 2, 3

and 5:0.999,P < 0.001),indicating that the 3D prints do not

introduce greater intraobserver measurement variability in basic

dental metrics than occurs with the original specimen. Similarly,

the calculated concordance correlation coefficients indicate sub-

stantial concordance between the dental metrics derived from the

original and 3D printed maxillae(Original vs. Maxilla 1:

qc5 0.9869;Originalvs. Maxilla 2: qc5 0.9844;Originalvs.

Maxilla 3: qc5 0.9799;Originalvs. Maxilla 4: qc5 0.9943;

Original vs. Maxilla 5: qc5 0.9852). This demonstrates that 3D

printed specimens retain sufficient resolution to provide dental

metrics of high concordance with the original.

Cost Effectiveness

While it is difficult to draw an exactcomparison with the

cost of producing plastinated specimens approximate costs of

establishing 3D printing based on the experience at Monash

Universityare provided (seeTable 1). Three-dimensional

printer purchase prices vary depending on the complexity of

the machine,the material(powder or plastic),build tray size

and ability to print in color. Generally plastic printers are less

expensive (desktop versions can be as inexpensive as $200–

$6,000 [Pricesquoted in US$]).Powder printerscan vary

from $70,000 to $100,000 and multimaterialprinters can

be around $400,000.For institutions unwilling or unable to

purchase a printer the option ofcourse now exists to have

any file printed by externalparties and a number ofmajor

companiesoffer such online 3D printing services.In our

experience the costof establishing a plastination laboratory

within an existing anatomy facility that complied with insti-

tutionalHealth and Safety regulationswas preclusive (esti-

mates of $600,000). A comparison of the price of currently

commercially available human plastinated specimensto 3D

prints is difficult as each will not be identical to commercially

available plastinated specimens.However, readers are

directed to the price catalogue of one of the severalcompa-

nies thatsell plastinated human specimens.For example,in

2014,an entire upper limb costs around $14,000.A plastic

“SOMSO” upper limb model (Marcus SommerSOMSO

Modelle GmbH, Coburg, Germany)is $1,800. Material

costs for the closest equivalent 3D print produced in our lab-

oratory (Fig.3A) is $300–350 in direct materialcosts.Of

course for the production of every single plastinated specimen

there is the continuing costs to dissect each specimen whereas

for 3D prints these production costs are one offas multiple

copies can be readily produced.

DISCUSSION

Using a combination of imaging acquisition technology, image

processing,and colored 3D printing,we have demonstrated

that accurate 3D printed colorcopiesof dissected human

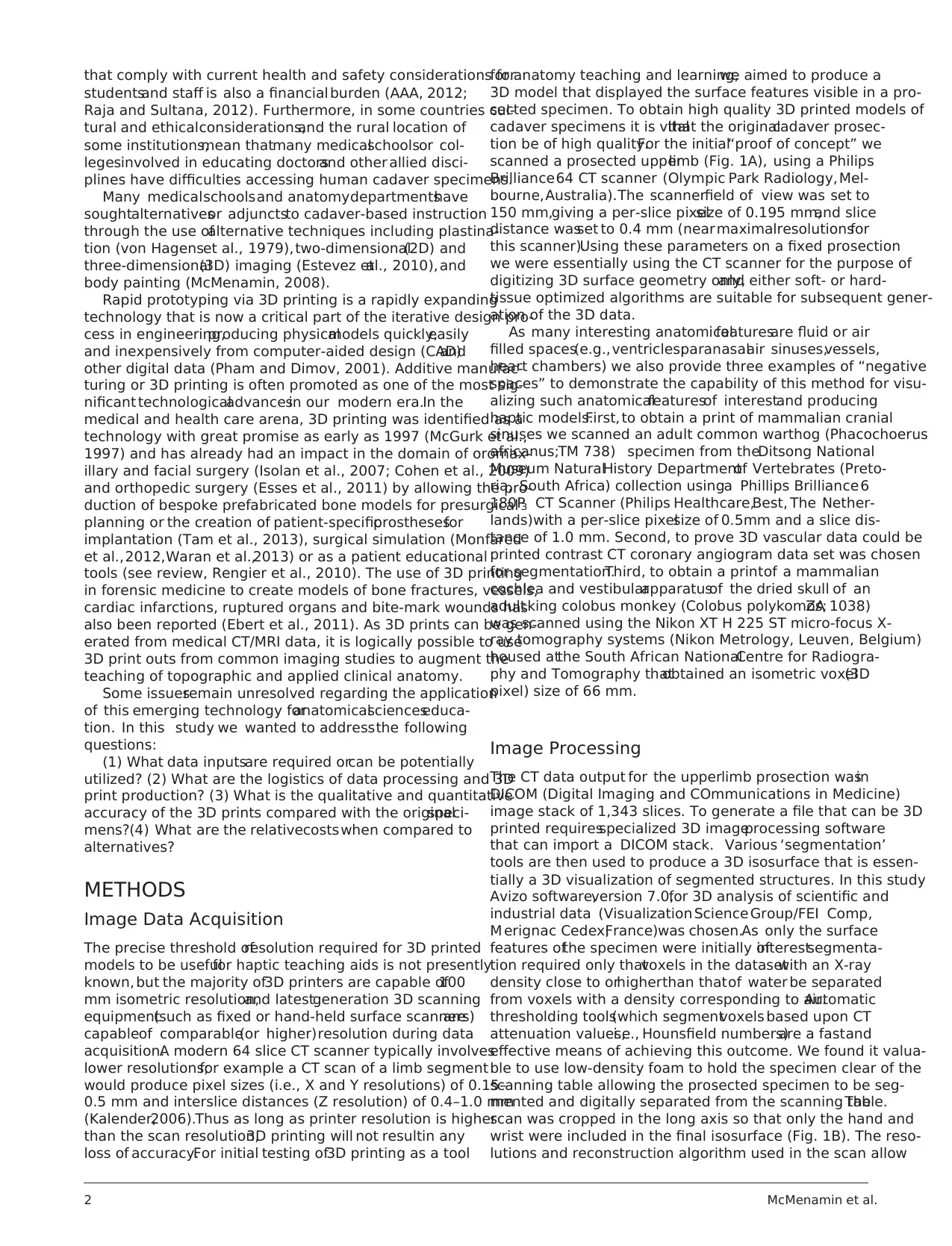

Table 1.

Approximate Costs Comparison Between Three-dimensional(3D) Printing and Plastination at Monash University in Australia

Three-dimensional (3D) printing Cost (in US$) Plastination Cost (in US$)

Start up expenses

Printer (Z650) $65,000 Establishing plastination facility “in house” $600,000

Software $5,000–$8,000 Plastination equipment $80,000

CT scanning charge $400/houra Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

Computers $5,000

Ongoing costs (per annum)

Consumables (calculated per printed

volume unit)

$0.55/cm3 Consumables (i.e., polymers and acetone

calculated per weight of specimen)

$400/kg

Technicalstaff to operate printer facility $40,000 Technicalstaff to operate plastination suite $40,000

Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

aUp to 20 specimens can be scanned in 1 hour.

bThese are labor costs only and do not include the fee associated with the human cadaver specimen. In the authors’ case the fee a

ated with obtaining cadavers is $8,500.

Note: Above cost may vary in different countries and institutions.

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 5

ning of klipspringer dentition (Fig.2 Supporting Information)

revealed that the range of length and width measurements derived

from the premolars (P2-P4) and molars (M1-M3) from the origi-

nal specimen largely overlap with those recorded from the 3D

printed reproductions (Fig.4 Supporting Information).Even in

those measures where the means and ranges display minimal

overlap,it is worth noting that in every measure the recorded

ranges of the original and at least one of the printed specimens

overlap;and the differences between the means of the original

and 3D reproduced specimens are maximally 0.2–0.3 mm.The

ICC value for the repeated measures on the originalspecimen

(0.998,P < 0.001) is similar to that of each of the 3D printed

reproductions (maxillae 1 and 4: 0.998, P < 0.001; maxillae 2, 3

and 5:0.999,P < 0.001),indicating that the 3D prints do not

introduce greater intraobserver measurement variability in basic

dental metrics than occurs with the original specimen. Similarly,

the calculated concordance correlation coefficients indicate sub-

stantial concordance between the dental metrics derived from the

original and 3D printed maxillae(Original vs. Maxilla 1:

qc5 0.9869;Originalvs. Maxilla 2: qc5 0.9844;Originalvs.

Maxilla 3: qc5 0.9799;Originalvs. Maxilla 4: qc5 0.9943;

Original vs. Maxilla 5: qc5 0.9852). This demonstrates that 3D

printed specimens retain sufficient resolution to provide dental

metrics of high concordance with the original.

Cost Effectiveness

While it is difficult to draw an exactcomparison with the

cost of producing plastinated specimens approximate costs of

establishing 3D printing based on the experience at Monash

Universityare provided (seeTable 1). Three-dimensional

printer purchase prices vary depending on the complexity of

the machine,the material(powder or plastic),build tray size

and ability to print in color. Generally plastic printers are less

expensive (desktop versions can be as inexpensive as $200–

$6,000 [Pricesquoted in US$]).Powder printerscan vary

from $70,000 to $100,000 and multimaterialprinters can

be around $400,000.For institutions unwilling or unable to

purchase a printer the option ofcourse now exists to have

any file printed by externalparties and a number ofmajor

companiesoffer such online 3D printing services.In our

experience the costof establishing a plastination laboratory

within an existing anatomy facility that complied with insti-

tutionalHealth and Safety regulationswas preclusive (esti-

mates of $600,000). A comparison of the price of currently

commercially available human plastinated specimensto 3D

prints is difficult as each will not be identical to commercially

available plastinated specimens.However, readers are

directed to the price catalogue of one of the severalcompa-

nies thatsell plastinated human specimens.For example,in

2014,an entire upper limb costs around $14,000.A plastic

“SOMSO” upper limb model (Marcus SommerSOMSO

Modelle GmbH, Coburg, Germany)is $1,800. Material

costs for the closest equivalent 3D print produced in our lab-

oratory (Fig.3A) is $300–350 in direct materialcosts.Of

course for the production of every single plastinated specimen

there is the continuing costs to dissect each specimen whereas

for 3D prints these production costs are one offas multiple

copies can be readily produced.

DISCUSSION

Using a combination of imaging acquisition technology, image

processing,and colored 3D printing,we have demonstrated

that accurate 3D printed colorcopiesof dissected human

Table 1.

Approximate Costs Comparison Between Three-dimensional(3D) Printing and Plastination at Monash University in Australia

Three-dimensional (3D) printing Cost (in US$) Plastination Cost (in US$)

Start up expenses

Printer (Z650) $65,000 Establishing plastination facility “in house” $600,000

Software $5,000–$8,000 Plastination equipment $80,000

CT scanning charge $400/houra Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

Computers $5,000

Ongoing costs (per annum)

Consumables (calculated per printed

volume unit)

$0.55/cm3 Consumables (i.e., polymers and acetone

calculated per weight of specimen)

$400/kg

Technicalstaff to operate printer facility $40,000 Technicalstaff to operate plastination suite $40,000

Specimen prosection costs $20/hour b

aUp to 20 specimens can be scanned in 1 hour.

bThese are labor costs only and do not include the fee associated with the human cadaver specimen. In the authors’ case the fee a

ated with obtaining cadavers is $8,500.

Note: Above cost may vary in different countries and institutions.

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 5

anatomical specimens can be rapidly and economically repro-

duced.In addition,we have shown that it is possible to seg-

ment negative spaces such as air sinuses and vascular spaces

from radiologicaldata and print them in a form suitable for

teaching.

To date there have been limited publications examining the

potentialrole of 3D printing in medicaleducation.A recent

investigation examined the value of3D prints of the distal

equine limb in the teaching of anatomy to veterinary students

(Preece etal., 2013).This model,which was based on high

resolution MRI scanning data,reproduced the bones in hard

plastic and the soft tissues (ligaments, tendons) in a more flexi-

ble material.Students were able to physically reconstruct the

horse foot modeldue to the aid of magnets embedded in the

printed elements.In an evaluation of their modelthe authors

found a significant improvement in students’ overall scores in

an MRI based assessment of equine foot anatomy and a raised

confidencelevelsin dealing with visuospatialinformation.

Unlike the prints produced in the present investigation the sin-

gle equine foot modelwas largely monochrome and did not

attempt to capture neural or vascular structures. Another study

utilized 3D printing technology to copy a rare corrosion cast of

the human lungs and airways Liet al.(2012).Thus the data

was not obtained from soft-tissue human anatomical material

or indeed medical imaging, but rather employed 3D printing to

reproduce a complex castthat would have been otherwise

impossible to copy by conventional manufacturing methods.

The advantages of the 3D printed copies of cadaver pro-

sectionsor anatomicalspecimensillustrated in the present

report include durability,accuracy,ease of reproduction,cost

effectiveness,and the avoidance ofhealth and safety issues

associated with wetfixed cadaverspecimensor plastinated

specimens.The most suitableprinter types for producing

teaching specimens are powder infiltration,plastic extrusion,

and multi-property.Each has strengths and limitations.Pow-

der infiltration printers, which essentiallyutilize a glue

(binder) to print over a layer of fine plaster powder,layer by

layer into a 3D shape,are relatively economicalto run and

have fast build times. Plastic extrusion printersproduce

slightly higherresolutionsin a stronger materialbut have

higher consumable costs, longer print times and limited color

options,although rapid technologicalchanges may soon neg-

ate some ofthese issues.It is likely that in the very near

future plastic printers will be able to print in the same sort of

color fidelity that currentlypowder printerscan and we

believe these will be more robust for teaching purposes while

powder printers may remain critical for prototyping.

Multiproperty printersare able to print complex struc-

tures in a variety of materials, including rubbers and plastics,

but are commensurately more expensive,and until recently

have generally not been capable of producing a palette of col-

ors as used in the present study.The quantitative evaluation

we performed also showed the close correlation between the

real prosection and the 3D printed reproduction,allowing

the printing of even the smallest digital nerves with only rela-

tively minor variations in size when compared to the original

specimen.A previous study by Smith etal (2013)found an

accuracy of0.1 mm in printing ofradiographic data ofhip

and shoulder joint surfaces and highlighted that segmentation

is actually a greater source of variance that the printing itself.

When 3D printing from DICOM data is being performed it

is vitalthat the scan resolution (slice thickness) is as close to

the layer thickness of the chosen 3D printer,a point recently

made by Houtilainen etal. (2014)and also evidentin our

experience. A further advantage of the present method of 3D

printing wasthe relative ease with which we could rescale

the data files to reproduce accurate larger or smaller repro-

ductions of prosected material or negative spaces (Fig. 3).

Perhaps the most notable advantages of 3D printing of repro-

ductions of anatomical dissections are its multiple benefits over

plastic models and plastinated cadaver specimens. Plastic mod-

els are in common use in high schools,doctors’ surgeries and

medical schools. They are mass produced copies or molds of a

“hypothetical” or“caricatured” anatomicalspecimensthat

often lack importantspecific details.While suitable for some

teaching purposes they are not ideal for teaching detailed anat-

omy typically required in medical and other allied health profes-

sionalcourses.While plastinated specimens can be produced

that display detailed anatomicalinformation a noteworthy

advantage of 3D printed reproductions is that they are reason-

ably inexpensive, easy to reproduce multiple copies and thus are

an attractive alternative forteaching facilitiesor universities

which may have no access to cadavers for teaching for logistical

reasons (rural sites,developing countries) or due to socialand

culturalbarriers.In addition,anatomicalvariations can easily

be demonstrated by printing multiple data sets; indeed we have

already begun to do this by printing left dominant, right domi-

nant and codominant variants of coronary artery distribution.

One of the alternatives to 3D printing, plastination, is a method

of substitution or infiltration ofdehydrated cadaver material

with an inflexible polymer silicon compound. It was developed

by Gunther von Hagensand madepopularby the “Body

Worlds” and other similar exhibitions (von Hagens, 1979; Bick-

ley et al., 1981). However, ethical issues have been raised about

the source of cadavers and the trading in human remains in one

country to another part of the world for commercial gain (Jones

and Whitaker,2009;Collier,2010). Preparation of plastinated

specimens from cadavers sourced from local bequest programs

is one possible solution but this involves considerable costs and

health and safety issues due to the large volumes of flammable

solvents involved.In addition,teaching large classes requires

multiple prosections of each body region,and preparing these

requires a localpool of skilled prosectors to create multiple

specimens for plastination.By contrast,a modern 3D printer

can be housed in a conventional office.

Under section 32 of the Human Tissue Act (1982) in Aus-

tralia the purposes for which a body can be donated are “the

use of [the] body for the study and teaching of the anatomy

of the human body.” We consider that our 3D copies of par-

ticular body parts are produced as a teaching aid and there-

fore come under the purpose of “teaching of anatomy” and

have been advised by the responsible localgovernment legis-

lative authority thatthey seeno ethical dilemma in their

reproduction.Indeed one could easily draw the analogy of

the reproduction of3D imageswith that of 2D imagesof

human cadaveric dissectionsthat are widely used in many

textbook or multimedia teaching aids.

Limitations to 3D Printing

There are of course some limitations to 3D printed copies of

human anatomicalprosections.Firstly,the outputis only as

good as the input,therefore it is imperative that high quality

prosections illustrating as many features as possible without

being overly complex are produced and selected forimage

acquisition and processing.The dissected specimens have to

be amenable to scanning and reproduction by 3D printing. A

6 McMenamin et al.

duced.In addition,we have shown that it is possible to seg-

ment negative spaces such as air sinuses and vascular spaces

from radiologicaldata and print them in a form suitable for

teaching.

To date there have been limited publications examining the

potentialrole of 3D printing in medicaleducation.A recent

investigation examined the value of3D prints of the distal

equine limb in the teaching of anatomy to veterinary students

(Preece etal., 2013).This model,which was based on high

resolution MRI scanning data,reproduced the bones in hard

plastic and the soft tissues (ligaments, tendons) in a more flexi-

ble material.Students were able to physically reconstruct the

horse foot modeldue to the aid of magnets embedded in the

printed elements.In an evaluation of their modelthe authors

found a significant improvement in students’ overall scores in

an MRI based assessment of equine foot anatomy and a raised

confidencelevelsin dealing with visuospatialinformation.

Unlike the prints produced in the present investigation the sin-

gle equine foot modelwas largely monochrome and did not

attempt to capture neural or vascular structures. Another study

utilized 3D printing technology to copy a rare corrosion cast of

the human lungs and airways Liet al.(2012).Thus the data

was not obtained from soft-tissue human anatomical material

or indeed medical imaging, but rather employed 3D printing to

reproduce a complex castthat would have been otherwise

impossible to copy by conventional manufacturing methods.

The advantages of the 3D printed copies of cadaver pro-

sectionsor anatomicalspecimensillustrated in the present

report include durability,accuracy,ease of reproduction,cost

effectiveness,and the avoidance ofhealth and safety issues

associated with wetfixed cadaverspecimensor plastinated

specimens.The most suitableprinter types for producing

teaching specimens are powder infiltration,plastic extrusion,

and multi-property.Each has strengths and limitations.Pow-

der infiltration printers, which essentiallyutilize a glue

(binder) to print over a layer of fine plaster powder,layer by

layer into a 3D shape,are relatively economicalto run and

have fast build times. Plastic extrusion printersproduce

slightly higherresolutionsin a stronger materialbut have

higher consumable costs, longer print times and limited color

options,although rapid technologicalchanges may soon neg-

ate some ofthese issues.It is likely that in the very near

future plastic printers will be able to print in the same sort of

color fidelity that currentlypowder printerscan and we

believe these will be more robust for teaching purposes while

powder printers may remain critical for prototyping.

Multiproperty printersare able to print complex struc-

tures in a variety of materials, including rubbers and plastics,

but are commensurately more expensive,and until recently

have generally not been capable of producing a palette of col-

ors as used in the present study.The quantitative evaluation

we performed also showed the close correlation between the

real prosection and the 3D printed reproduction,allowing

the printing of even the smallest digital nerves with only rela-

tively minor variations in size when compared to the original

specimen.A previous study by Smith etal (2013)found an

accuracy of0.1 mm in printing ofradiographic data ofhip

and shoulder joint surfaces and highlighted that segmentation

is actually a greater source of variance that the printing itself.

When 3D printing from DICOM data is being performed it

is vitalthat the scan resolution (slice thickness) is as close to

the layer thickness of the chosen 3D printer,a point recently

made by Houtilainen etal. (2014)and also evidentin our

experience. A further advantage of the present method of 3D

printing wasthe relative ease with which we could rescale

the data files to reproduce accurate larger or smaller repro-

ductions of prosected material or negative spaces (Fig. 3).

Perhaps the most notable advantages of 3D printing of repro-

ductions of anatomical dissections are its multiple benefits over

plastic models and plastinated cadaver specimens. Plastic mod-

els are in common use in high schools,doctors’ surgeries and

medical schools. They are mass produced copies or molds of a

“hypothetical” or“caricatured” anatomicalspecimensthat

often lack importantspecific details.While suitable for some

teaching purposes they are not ideal for teaching detailed anat-

omy typically required in medical and other allied health profes-

sionalcourses.While plastinated specimens can be produced

that display detailed anatomicalinformation a noteworthy

advantage of 3D printed reproductions is that they are reason-

ably inexpensive, easy to reproduce multiple copies and thus are

an attractive alternative forteaching facilitiesor universities

which may have no access to cadavers for teaching for logistical

reasons (rural sites,developing countries) or due to socialand

culturalbarriers.In addition,anatomicalvariations can easily

be demonstrated by printing multiple data sets; indeed we have

already begun to do this by printing left dominant, right domi-

nant and codominant variants of coronary artery distribution.

One of the alternatives to 3D printing, plastination, is a method

of substitution or infiltration ofdehydrated cadaver material

with an inflexible polymer silicon compound. It was developed

by Gunther von Hagensand madepopularby the “Body

Worlds” and other similar exhibitions (von Hagens, 1979; Bick-

ley et al., 1981). However, ethical issues have been raised about

the source of cadavers and the trading in human remains in one

country to another part of the world for commercial gain (Jones

and Whitaker,2009;Collier,2010). Preparation of plastinated

specimens from cadavers sourced from local bequest programs

is one possible solution but this involves considerable costs and

health and safety issues due to the large volumes of flammable

solvents involved.In addition,teaching large classes requires

multiple prosections of each body region,and preparing these

requires a localpool of skilled prosectors to create multiple

specimens for plastination.By contrast,a modern 3D printer

can be housed in a conventional office.

Under section 32 of the Human Tissue Act (1982) in Aus-

tralia the purposes for which a body can be donated are “the

use of [the] body for the study and teaching of the anatomy

of the human body.” We consider that our 3D copies of par-

ticular body parts are produced as a teaching aid and there-

fore come under the purpose of “teaching of anatomy” and

have been advised by the responsible localgovernment legis-

lative authority thatthey seeno ethical dilemma in their

reproduction.Indeed one could easily draw the analogy of

the reproduction of3D imageswith that of 2D imagesof

human cadaveric dissectionsthat are widely used in many

textbook or multimedia teaching aids.

Limitations to 3D Printing

There are of course some limitations to 3D printed copies of

human anatomicalprosections.Firstly,the outputis only as

good as the input,therefore it is imperative that high quality

prosections illustrating as many features as possible without

being overly complex are produced and selected forimage

acquisition and processing.The dissected specimens have to

be amenable to scanning and reproduction by 3D printing. A

6 McMenamin et al.

furtherlimitation isthe lack of pliability compared to real

dissections,however,this is also a limitation ofplastinated

specimens.Thus we advocate 3D printed anatomicalreplicas

not as a replacementbut an adjunctto actualdissection.If

access to cadaver materialis not an option or unavailable to

students we maintain that 3D prints may offer a novel, accu-

rate and effective substitute.Evaluation studies are planned

to gather direct evidence of their value in teaching.

CONCLUSIONS

The range of possible usesof 3D printing for reproducing

accurate replicas of human anatomical material presented are

different from previous methods of producing teaching mate-

rials. They are only made possible by the application of tech-

nological advancesthat allow the physical printing of

computer generated three-dimensionaldata.While this tech-

nology has been available to engineers for severaldecades it

is only now thatits biomedicalapplications are being real-

ized. Three-dimensional printing is likely to play a significant

role in pathology teaching, veterinary anatomy teaching, zoo-

logicalspecimen reproduction,reproduction of rare museum

specimens,to name a few potential applications.We are

actively exploring the use ofmultiple materialprinting and

the printing of cell and tissue data from confocal microscopic

studies which willintroduce yet another entirely new dimen-

sion to this science education revolution.

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

PAUL G. MCMENAMIN, D.Sc. (Med), is a professorand

Director of the Centre for Human Anatomy Education in the

Department of Anatomy and DevelopmentalBiology,Faculty

of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at Monash Univer-

sity,Clayton,Australia.He has been teaching human anat-

omy to undergraduate and postgraduate medicaland science

students for over 30 years.

MICHELLE R. QUAYLE, B.Env.Sc.Mgt.(Hons), is a

research and technicalassistantfor the Centre of Human

Anatomy Education in the Departmentof Anatomy and

DevelopmentalBiology,Faculty of Medicine,Nursing and

Health Sciencesat Monash University,Clayton, Australia.

She researches 3D modeling techniques and runs the Centre

of Human Anatomy Education’s 3D printer.

COLIN R. MCHENRY, Ph.D., is a lecturer in the Centre

for Human Anatomy Education in the Department of Anat-

omy and DevelopmentalBiology,Faculty of Medicine,Nurs-

ing and Health Sciencesat Monash University,Clayton,

Australia.He teacheshuman and comparative anatomy to

medical and science undergraduate and postgraduate students

and utilizes 3D modeling in his research.

JUSTIN W. ADAMS, Ph.D., is a senior lecturerin the

Centre for Human Anatomy Education in the Department of

Anatomy and DevelopmentalBiology,Faculty of Medicine,

Nursing and Health Sciences at Monash University,Clayton,

Australia.He teacheshuman and comparative anatomy to

medical and science undergraduate and postgraduate students

and uses 3D printing in his paleontology research.

LITERATURE CITED

AAA. 2012.American Association of Anatomists.Gross Anatomy Laboratory

Design. AAA, Bethesda,MD. URL: http://www.anatomy.org/content/gross-

anatomy-laboratory-design [accessed 25 March 2014].

Bickley HC, von Hagens G,Townsend FM.1981.An improved method for

the preservation of teaching specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med 105:674–676.

Chambers J,Emlyn-Jones D.2009. Keeping dissection alive for medicalstu-

dents. Anat Sci Educ 2:302–303.

Cohen A,Laviv A, Berman P,Nashef R,Abu-Tair J. 2009.Mandibular recon-

struction using stereolithographic 3-dimensionalprinting modeling technology.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 108:661–666.

Collier R. 2010. Cadaver shows stir controversy. CMAJ 182:687–688.

Drake RL, McBride JM, Lachman N, Pawlina W. 2009. Medical education in the ana-

tomical sciences: The winds of change continue to blow. Anat Sci Educ 2:253–259.

Ebert LC, Thali MJ, Ross S. 2011. Getting in touch-3D printing in forensic

imaging. Forensic Sci Int 10:e1–e6.

Esses SJ,Berman P,Bloom AI, Sosna J.2011.Clinical applications of physical

3D models derived from MDCT data and created by rapid prototyping.AJR

Am J Roentgenol 196:W683–W688.

Estevez ME, Lindgren KA, Bergethon PR.2010. A novel three-dimensional

tool for teaching human anatomy. Anat Sci Educ 3:309–317.

Heetun M. 2009.Anatomy dissection:A valuable surgicaltraining tool.Br J

Hosp Med (Lond) 70:540.

Human Tissue Act. 1982. Version No. 036. Human Tissue Act 1982 No. 9860

of 1982. Version incorporating amendmentsas at 1 January 2010. Public

Health Branch, Rural and Regional Health and Aged Care Services Division of

the Victorian State Government,Department ofHealth,Melbourne,Victoria,

Australia. URL: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/humantissue/htact[accessed 31

May 2014].

Huotilainen E,Paloheimo M,SalmiM, Paloheimo KS,Bj€orkstrand R,Tuomi

J, Markkola A, M €akitie A. 2014. Imaging requirements for medicalapplica-

tions of additive manufacturing. Acta Radiol 55:78–85.

Isolan GR, Rowe R, Al-Mefty O. 2007. Microanatomy and surgical

approaches to the infratemporal fossa: An anaglyphic three-dimensional stereo-

scopic printing study. Skull Base 17:285–302.

Janis CM. 1988. An estimation oftooth volume and hypsodonty indicies in

ungulate mammals,and the correlation ofthese factorswith dietary prefer-

ence.In: RusselDE, Santoro JP,Sigogneau-RussellD (Editors). Teeth Revis-

ited: Proceedingsof the VIIth International Symposium on Dental

Morphology:Memoires Du Museum NationalD’Histoire Naturelle Series C

53. 1st Ed. Paris, France: Museum National D’Histoire Naturelle. p 367–387.

Johnson EO, Charchanti AV, Troupis TG. 2012. Modernization of an anatomy

class:From conceptualization to implementation.A case for integrated multi-

modal–multidisciplinary teaching. Anat Sci Educ 5:354–366.

Jones DG, Whitaker MI. 2009. Engaging with plastination and theBody

Worlds phenomenon:A culturaland intellectual challenge for anatomists.Clin

Anat 22:770–776.

Kalender WA. 2006. X-ray computed tomography. Phys Med Biol 51:R29–R43.

Korf HW, Wicht H, Snipes RL, TimmermansJP, Paulsen F, Rune G,

Baumgart-VogtE. 2008. The dissection course—Necessary and indispensable

for teaching anatomy to medical students. Ann Anat 190:16–22.

Li J, Nie L, Li Z, Lin L, Tang L, Ouyang J.2012.Maximizing modern distri-

bution of complex anatomicalspatial information:3D reconstruction and

rapid prototype production of anatomical corrosion casts of human specimens.

Anat Sci Educ 5:330–339.

Lin LI. 1989. A concordance correlation coeffecient to evaluate reproducibility.

Biometrics 45:255–268.

Lin LI. 2000. A note on the concordance correlation coefficient.Biometrics

56:324–325.

McGurk M, Amis AA, Potamianos P, Goodger NM. 1997. Rapid prototyping tech-

niques for anatomical modelling in medicine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 79:169–174.

McLachlan JC, Patten D. 2006. Anatomy teaching: Ghosts of the past, present

and future. Med Educ 40:243–253.

McMenamin PG.2008.Body painting as a toolin clinicalanatomy teaching.

Anat Sci Educ 1:139–144.

Monfared A,Mitteramskogler G,Gruber S,Salisbury JK Jr,StampflJ, Blevins

NH. 2012.High-fidelity,inexpensive surgicalmiddle ear simulator.Otol Neu-

rotol 33:1573–1577.

Parker LM. 2002.Anatomicaldissection:Why are we cutting itout? Dissec-

tion in undergraduate teaching. ANZ J Surg 72:910–912.

Pham DT, Dimov SS. 2001. Rapid Manufacturing:The Technologiesand

Applications ofRapid Prototyping and Rapid Tooling.1st Ed. London, UK:

Springer-Verlag. 234 p.

Preece D,Williams SB,Lam R, Weller R. 2013.“Let’s get physical”:Advan-

tages of a physicalmodel over 3D computer models and textbooks in learning

imaging anatomy. Anat Sci Educ 6:216–224.

Raja DS, Sultana B.2012. Potentialhealth hazards forstudentsexposed to

formaldehyde in the gross anatomy laboratory. J Environ Health 74:36–40.

Ramsey-Stewart G,Burgess AW,Hill DA. 2010.Back to the future:Teaching

anatomy by whole-body dissection. Med J Aust 193:668–671.

Rengier F, Mehndiratta A, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Zechmann CM,

Unterhinninghofen R,Kauczor HU, GieselFL. 2010. 3D printing based on

imaging data: Review of medical applications. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg

5:335–341.

AnatomicalSciences EducationMONTH 2014 7

dissections,however,this is also a limitation ofplastinated

specimens.Thus we advocate 3D printed anatomicalreplicas

not as a replacementbut an adjunctto actualdissection.If

access to cadaver materialis not an option or unavailable to

students we maintain that 3D prints may offer a novel, accu-

rate and effective substitute.Evaluation studies are planned

to gather direct evidence of their value in teaching.

CONCLUSIONS

The range of possible usesof 3D printing for reproducing

accurate replicas of human anatomical material presented are

different from previous methods of producing teaching mate-

rials. They are only made possible by the application of tech-

nological advancesthat allow the physical printing of

computer generated three-dimensionaldata.While this tech-