Investigating Anxiety's Impact on Cognitive Abilities in Older Adults

VerifiedAdded on 2020/07/22

|32

|9062

|81

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the impact of anxiety on cognitive functions, specifically focusing on information processing speed, memory, and attention in older adults. The study employs a comparative analysis between younger and older adult groups using various assessment tools, including anxiety inventories, cognitive function tests, and visual search tasks. The findings reveal detrimental effects of anxiety, particularly in older males, with higher depression scores correlating to longer visual search times. The research aligns with prior studies suggesting anxiety's influence on response times and highlights the importance of considering subjective cognitive function and intra-individual variability. The report also examines the potential influence of sex and educational level on information processing speed and discusses the implications of these findings for understanding cognitive decline in ageing and age-related diseases. The study emphasizes the need for further research to explore the complex interplay between anxiety and cognitive performance in the context of ageing.

1

Does Anxiety influence Information Processing Speed and variability, Memory and attention in

ageing?

Does Anxiety influence Information Processing Speed and variability, Memory and attention in

ageing?

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The main objective behind carry out study is to analyze the extent to

which anxiety level has high level of impact on information processing speed, memory and

attention in older adulthood.

METHODS: Tests of anxiety, including beck anxiety inventory, state and trait anxiety,

sleep quality, depression and subjective and objective cognitive functioning and visual search

task were administered to two groups of adults, one younger (n= 52; 18-25 years) and one older

(n= 52; 50-80 years).

RESULTS: From assessment, it has identified that detrimental effects of anxiety are not

limited to the clinical disorders. Hence, higher depression scores resulted in longer Visual

Search Effect times. All these were statistically significant, and occurred only in older males.

Prior studies have indicated that anxiety lengthens response times, and the Visual Search task

displayed impacts of anxiety levels.

DISCUSSION: From assessment, it has identified that results were consistent with prior

studies pertaining to anxiety lengthens response times. Along with this, it has found from visual

search task results that anxiety level has influence on response times.

Keywords: Anxiety, Attention, Information processing speed, Subjective memory

function, Objective cognitive function, Ageing.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The main objective behind carry out study is to analyze the extent to

which anxiety level has high level of impact on information processing speed, memory and

attention in older adulthood.

METHODS: Tests of anxiety, including beck anxiety inventory, state and trait anxiety,

sleep quality, depression and subjective and objective cognitive functioning and visual search

task were administered to two groups of adults, one younger (n= 52; 18-25 years) and one older

(n= 52; 50-80 years).

RESULTS: From assessment, it has identified that detrimental effects of anxiety are not

limited to the clinical disorders. Hence, higher depression scores resulted in longer Visual

Search Effect times. All these were statistically significant, and occurred only in older males.

Prior studies have indicated that anxiety lengthens response times, and the Visual Search task

displayed impacts of anxiety levels.

DISCUSSION: From assessment, it has identified that results were consistent with prior

studies pertaining to anxiety lengthens response times. Along with this, it has found from visual

search task results that anxiety level has influence on response times.

Keywords: Anxiety, Attention, Information processing speed, Subjective memory

function, Objective cognitive function, Ageing.

3

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment implies for the situation of abnormality that is higher as

compared to expected aspects pertaining to age and education. From assessment, it has found

that situation of self-perceived cognitive decline pertaining to memory aspect usually occurred

among older adults having both MCI and dementia at early stage. Along with this, it has found

that memory function closely influences daily life and mental health of individual. In both

cognitively healthy ageing and ageing–related diseases states such as Alzheimer’s disease, a

large body of evidence supports an association between information processing speed and the

functional integrity of both cognitive and of neuroanatomical aspects of the mind. These impacts

include changes to the brain’s white matter, and alterations to components of information

processing system (Anstey et al., 2007; Haynes et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2013; Lövdén, Shing

& Lindberger, 2007; Voelker et al., 2017). Neuroanatomical studies have identified age-related

differences in the interhemispheric data transfer rates and activation as well as differences in

white matter integrity, with older adults demonstrating greater transfer rates than younger ones,

possibly as a compensatory strategy to overcome ageing-related cognitive declines (Anstey et al.,

2007; Haynes et al., 2017). These differences are identifiable using reaction time tasks as

fundamental measures of both interhemispheric transfer and cognitive changes due to ageing

(Antsey et al., 2007).

As defined in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) occurs when an

individual experiences memory and other core brain functions problems that do not interfere

with independent living and which are not due to delirium or another mental disorder (APA,

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment implies for the situation of abnormality that is higher as

compared to expected aspects pertaining to age and education. From assessment, it has found

that situation of self-perceived cognitive decline pertaining to memory aspect usually occurred

among older adults having both MCI and dementia at early stage. Along with this, it has found

that memory function closely influences daily life and mental health of individual. In both

cognitively healthy ageing and ageing–related diseases states such as Alzheimer’s disease, a

large body of evidence supports an association between information processing speed and the

functional integrity of both cognitive and of neuroanatomical aspects of the mind. These impacts

include changes to the brain’s white matter, and alterations to components of information

processing system (Anstey et al., 2007; Haynes et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2013; Lövdén, Shing

& Lindberger, 2007; Voelker et al., 2017). Neuroanatomical studies have identified age-related

differences in the interhemispheric data transfer rates and activation as well as differences in

white matter integrity, with older adults demonstrating greater transfer rates than younger ones,

possibly as a compensatory strategy to overcome ageing-related cognitive declines (Anstey et al.,

2007; Haynes et al., 2017). These differences are identifiable using reaction time tasks as

fundamental measures of both interhemispheric transfer and cognitive changes due to ageing

(Antsey et al., 2007).

As defined in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) occurs when an

individual experiences memory and other core brain functions problems that do not interfere

with independent living and which are not due to delirium or another mental disorder (APA,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

2013). Brain studies of individuals with MCI demonstrate that as many as 10 to 15 percent of

those with MCI develop full dementia within a year (Fauzan & Amran, 2015).

Information processing speed is commonly measured as part of the diagnosis of dementia

and cognitive impairment. In normal aging, the brain functions slow while intelligence measures

stabilise, and recall ability decreases significantly. Research evidence indicates that information

processing speed can vary significantly with respect to methodological factors such as the task

used and thus areas of the brain recruited for performance and response demands (Rodrigues &

Pandeirada, 2014; Valeriani et al., 2003) and person-related factors such as sex (Commmodari &

Guanera, 2013), education (Tales & Basoudan, 2016), and possibly genetic factors (Luo et al.,

2017). Interactions between these factors can result in significantly different impacts on

processing speeds depending on specific brain areas required for performance of tasks (Tales et

al., 2010; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Hence, older individuals often experience greater difficulty

remembering the name of people, places and other aspects. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

occurs when the individual experiences measureable problems in relation to memory and another

core brain functions. MCI is also associated with increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s

disease in the short term.

RT variability is impacted by a combination of three physiological effects: hemispheric

specialization, individual neuroanatomy, and transient functional fluctuations between trials

(Antonova et al., 2016), Thus, RT measures need to consider many aspects of typical behavior

and environmental interaction (Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014, Tales & Basoudan, 2016).

Results of information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted

with respect to such caveats, making it difficult to relate clinical to research findings. It is

included in DSM-5 for measurement specifically with respect to attention-related processing

2013). Brain studies of individuals with MCI demonstrate that as many as 10 to 15 percent of

those with MCI develop full dementia within a year (Fauzan & Amran, 2015).

Information processing speed is commonly measured as part of the diagnosis of dementia

and cognitive impairment. In normal aging, the brain functions slow while intelligence measures

stabilise, and recall ability decreases significantly. Research evidence indicates that information

processing speed can vary significantly with respect to methodological factors such as the task

used and thus areas of the brain recruited for performance and response demands (Rodrigues &

Pandeirada, 2014; Valeriani et al., 2003) and person-related factors such as sex (Commmodari &

Guanera, 2013), education (Tales & Basoudan, 2016), and possibly genetic factors (Luo et al.,

2017). Interactions between these factors can result in significantly different impacts on

processing speeds depending on specific brain areas required for performance of tasks (Tales et

al., 2010; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Hence, older individuals often experience greater difficulty

remembering the name of people, places and other aspects. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

occurs when the individual experiences measureable problems in relation to memory and another

core brain functions. MCI is also associated with increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s

disease in the short term.

RT variability is impacted by a combination of three physiological effects: hemispheric

specialization, individual neuroanatomy, and transient functional fluctuations between trials

(Antonova et al., 2016), Thus, RT measures need to consider many aspects of typical behavior

and environmental interaction (Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014, Tales & Basoudan, 2016).

Results of information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted

with respect to such caveats, making it difficult to relate clinical to research findings. It is

included in DSM-5 for measurement specifically with respect to attention-related processing

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

(Naveteur et.al., 2005). Research indicates that information processing speed can vary

significantly with respect to methodological factors such as the task used and thus areas of the

brain recruited for performance and response demands and person-related factors such as sex and

educational level (Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Such research evidence indicates

that the results of information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be

interpreted with respect to such caveats, especially as there is a high degree in variability in the

tasks used to measure information processing speeds in clinical populations, making the

comparison of results within the clinical arena problematic and also making it difficult to relate

clinical to research findings.

It is important to measure information processing speed because slowing of information

processing can have a negative influence upon many aspects of real life [Increased RT in older

adults has been shown to be associated to increased antagonist muscle co-activation. In older

subjects, the RTs for both measures were significantly longer than for younger adults (Arnold et

al., 2015). From assessment, it has identified that three physiological effects namely hemispheric

specialization, individual neuroanatomy and transient functional fluctuations between trials has

an impact on RT variability (Antonova et al., 2016). Thus, RT measures need to be assessed

appropriately and in relation to many aspects of typical behaviour and environmental interaction

(Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014).

By doing research, it has identified that risk of dementia can be reduced significantly

through the means of resourcefulness training. From evaluation, it has asserted that RT training

provides high level of assistance in reducing the level of caregiver stress. It is possible that other

factors that are rarely researched and rarely tested in clinical conditions, may also affect

information processing speed. One such factor is anxiety. Salthouse (2011) highlighted the

(Naveteur et.al., 2005). Research indicates that information processing speed can vary

significantly with respect to methodological factors such as the task used and thus areas of the

brain recruited for performance and response demands and person-related factors such as sex and

educational level (Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Such research evidence indicates

that the results of information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be

interpreted with respect to such caveats, especially as there is a high degree in variability in the

tasks used to measure information processing speeds in clinical populations, making the

comparison of results within the clinical arena problematic and also making it difficult to relate

clinical to research findings.

It is important to measure information processing speed because slowing of information

processing can have a negative influence upon many aspects of real life [Increased RT in older

adults has been shown to be associated to increased antagonist muscle co-activation. In older

subjects, the RTs for both measures were significantly longer than for younger adults (Arnold et

al., 2015). From assessment, it has identified that three physiological effects namely hemispheric

specialization, individual neuroanatomy and transient functional fluctuations between trials has

an impact on RT variability (Antonova et al., 2016). Thus, RT measures need to be assessed

appropriately and in relation to many aspects of typical behaviour and environmental interaction

(Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014).

By doing research, it has identified that risk of dementia can be reduced significantly

through the means of resourcefulness training. From evaluation, it has asserted that RT training

provides high level of assistance in reducing the level of caregiver stress. It is possible that other

factors that are rarely researched and rarely tested in clinical conditions, may also affect

information processing speed. One such factor is anxiety. Salthouse (2011) highlighted the

6

possibility that anxiety may affect RT performance and that although high levels of clinical

anxiety may be acknowledged to affect information processing speeds, lower levels of anxiety

are generally not considered to have any effect. In contrast, however, Tales and Basoudan (2016)

noted that anxiety has a high prevalence in older adults and that even non-clinical anxiety may

impact cognitive performance. One aim of this research is to determine the potential for anxiety

to affect the outcome of information processing speed in older adults.

Subjective Cognitive Function

Another factor that has rarely been considered in the investigation of information

processing speed in ageing and ageing-related disease is subjective cognitive function. Although

most studies examining information processing speed in ageing measure and factor in the

potential influence of objectively measured status of cognitive function it is rare for research

results to consider how subjective feelings or assessment of cognitive function may influence

information processing speed. Objective measures of poor general cognition are often found to

be related to slower information processing speeds compared to intact cognition in older adults

(Tales & Basoudan, 2016). It is possible that subjectively poor cognition may also affect

information processing speed (either via similar or different mechanisms as yet to be fully

identified).

If this is the case then both clinical and research findings would need to be interpreted

with respect to this caveat also. A further aim of this study is also to determine whether in older

adults either objectively measured or subjectively experienced cognitive function influences

information processing speed. Finally, the potential influence of sex (male/female) and

educational level upon information processing speed will also be investigated.

possibility that anxiety may affect RT performance and that although high levels of clinical

anxiety may be acknowledged to affect information processing speeds, lower levels of anxiety

are generally not considered to have any effect. In contrast, however, Tales and Basoudan (2016)

noted that anxiety has a high prevalence in older adults and that even non-clinical anxiety may

impact cognitive performance. One aim of this research is to determine the potential for anxiety

to affect the outcome of information processing speed in older adults.

Subjective Cognitive Function

Another factor that has rarely been considered in the investigation of information

processing speed in ageing and ageing-related disease is subjective cognitive function. Although

most studies examining information processing speed in ageing measure and factor in the

potential influence of objectively measured status of cognitive function it is rare for research

results to consider how subjective feelings or assessment of cognitive function may influence

information processing speed. Objective measures of poor general cognition are often found to

be related to slower information processing speeds compared to intact cognition in older adults

(Tales & Basoudan, 2016). It is possible that subjectively poor cognition may also affect

information processing speed (either via similar or different mechanisms as yet to be fully

identified).

If this is the case then both clinical and research findings would need to be interpreted

with respect to this caveat also. A further aim of this study is also to determine whether in older

adults either objectively measured or subjectively experienced cognitive function influences

information processing speed. Finally, the potential influence of sex (male/female) and

educational level upon information processing speed will also be investigated.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

Intra-Individual Variability

In the research arena in addition to measuring information processing speed it has been

common to measure also its intra-individual variability (IIVRT). IIVRT like information processing

speed is also related to cognitive and neuroanatomical factors, with increased variability

commonly but not always, related to disease related ageing such as Alzheimer’s disease, and in

some cases, has been found to be more sensitive to ageing and or disease than mean information

processing speed per se (Luo et al., 2017; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Although previous research

has examined IIVRT with respect to objectively measured cognitive function very little research

has examined the influence of subjective cognitive function and anxiety. This measure will thus

also be investigated in the present also be investigated in the present study considering gender

and level of education.

Attention

Attention is one of the cognitive functions most affected by ageing. The loss of function

in attention can impact a wide variety of cognitive activities and daily living functions (Akimoto

et al., 2014). Valeriani, Ranghi and Giaquinto (2003) identified differences in somatosensory

evoked potentials (SEPs) to median nerve stimulation between tasks requiring neutral

stimulation conditions and selective attention conditions for both older (mean age 71.7) and

younger (mean age 26.9) adults and abnormal attention function found in MCI and various

aetiologies of dementia (Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Of particular context for the

current study is the demand by DSM-5 that information processing speed should be measured

with respect to attentional function. In this study, therefore, these questions are investigated

Intra-Individual Variability

In the research arena in addition to measuring information processing speed it has been

common to measure also its intra-individual variability (IIVRT). IIVRT like information processing

speed is also related to cognitive and neuroanatomical factors, with increased variability

commonly but not always, related to disease related ageing such as Alzheimer’s disease, and in

some cases, has been found to be more sensitive to ageing and or disease than mean information

processing speed per se (Luo et al., 2017; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Although previous research

has examined IIVRT with respect to objectively measured cognitive function very little research

has examined the influence of subjective cognitive function and anxiety. This measure will thus

also be investigated in the present also be investigated in the present study considering gender

and level of education.

Attention

Attention is one of the cognitive functions most affected by ageing. The loss of function

in attention can impact a wide variety of cognitive activities and daily living functions (Akimoto

et al., 2014). Valeriani, Ranghi and Giaquinto (2003) identified differences in somatosensory

evoked potentials (SEPs) to median nerve stimulation between tasks requiring neutral

stimulation conditions and selective attention conditions for both older (mean age 71.7) and

younger (mean age 26.9) adults and abnormal attention function found in MCI and various

aetiologies of dementia (Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Of particular context for the

current study is the demand by DSM-5 that information processing speed should be measured

with respect to attentional function. In this study, therefore, these questions are investigated

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

using a computer-based visual search task which allows measurement of attention-related choice

reaction time and attentional function (Therrien & Hunsley, 2011).

Anxiety

Anxiety prevalence and levels vary with respect to age and age-related conditions such as

subjective and objective cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Estimates vary

from 1 to 28% depending on whether clinical or community-dwelling populations are used

(Bryant et al., 2008; Therrien & Hunsley, 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). Anxiety also

impact visuals search tasks, with generalized anxiety disorder patients showing slower RTs, but

not enhanced detection of threats (Rinck et al., 2003). There exists, however, a paucity of

evidence regarding the potential influence anxiety, especially non-clinical anxiety, may have

upon research outcome and therefore potentially clinical results and interpretation. Evidence

exists that associates anxiety with the ventral prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. These two

areas of the brain have greater activation in anxious situations as they are the main activation

sector to responses accorded by the brain (Guyer et al, 2008). Anxiety brings about an increase in

stimulus-driven processes that negatively impact efficient top-down control and consequently

have a detrimental effect on the ability to regulate emotional inhibitions (Ansari & Derakshan,

2011).

Anxiety also impact visuals search tasks, with generalized anxiety disorder patients

showing slower RTs, but not demonstrating enhanced detection of threats (Rinck et al., 2003).

Dennis, Scialfa and Ho (2004) found that older adults were no more reliant on bottom-up vs. top-

down learning in visual search tasks compared to younger adults, and were no more susceptible

to distractions.

using a computer-based visual search task which allows measurement of attention-related choice

reaction time and attentional function (Therrien & Hunsley, 2011).

Anxiety

Anxiety prevalence and levels vary with respect to age and age-related conditions such as

subjective and objective cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Estimates vary

from 1 to 28% depending on whether clinical or community-dwelling populations are used

(Bryant et al., 2008; Therrien & Hunsley, 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). Anxiety also

impact visuals search tasks, with generalized anxiety disorder patients showing slower RTs, but

not enhanced detection of threats (Rinck et al., 2003). There exists, however, a paucity of

evidence regarding the potential influence anxiety, especially non-clinical anxiety, may have

upon research outcome and therefore potentially clinical results and interpretation. Evidence

exists that associates anxiety with the ventral prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. These two

areas of the brain have greater activation in anxious situations as they are the main activation

sector to responses accorded by the brain (Guyer et al, 2008). Anxiety brings about an increase in

stimulus-driven processes that negatively impact efficient top-down control and consequently

have a detrimental effect on the ability to regulate emotional inhibitions (Ansari & Derakshan,

2011).

Anxiety also impact visuals search tasks, with generalized anxiety disorder patients

showing slower RTs, but not demonstrating enhanced detection of threats (Rinck et al., 2003).

Dennis, Scialfa and Ho (2004) found that older adults were no more reliant on bottom-up vs. top-

down learning in visual search tasks compared to younger adults, and were no more susceptible

to distractions.

9

Subjective feelings of cognitive impairment

Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), while not recognized as a mental disorder in the

DSM-V, may presage future decline in cognitive abilities. Symptoms of SCI reports are similar

to those for MCI: increasing level of forgetfulness, depression, overwhelmed feelings, etc.

(Stewart, 2012). SCI is considered subjective in nature because patients with SCI do not fail

objective tests of cognitive functioning, though they report cognitive lapses performing daily

cognitive tasks. Stewart (2012) noted that SCI is associated with some brain abnormalities

similar to those associated with dementia. Some underlying brain changes may be amenable to

interventions that slow or even stop further. An emerging area of research in ageing and

dementia is the characterization of subjective feelings of cognitive impairment and the

development of dementia and effects upon behaviour, daily living and social interaction

irrespective of aetiology (Torrens-Burton et al., 2017).

Methods

Participants

Participants included a group of younger (n =52) undergraduates chosen from the

psychology department at the University, with 31 females and 21 males (mean 19.9; s.d. 1.6;

range 18 to 25 years) and older adults (n =52) recruited from the general public, 32 females and

20 males (mean 66.5; s.d. 4.5; range 50 to 80 years). Exclusion criteria included severe

depression, poor self-reported general health; history of head injury or neurological, medical, or

psychological problems; medically diagnosed subjective cognitive impairment and self-reported

medications that impact cognitive functioning. All had normal or corrected to normal vision and

hearing.

Subjective feelings of cognitive impairment

Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), while not recognized as a mental disorder in the

DSM-V, may presage future decline in cognitive abilities. Symptoms of SCI reports are similar

to those for MCI: increasing level of forgetfulness, depression, overwhelmed feelings, etc.

(Stewart, 2012). SCI is considered subjective in nature because patients with SCI do not fail

objective tests of cognitive functioning, though they report cognitive lapses performing daily

cognitive tasks. Stewart (2012) noted that SCI is associated with some brain abnormalities

similar to those associated with dementia. Some underlying brain changes may be amenable to

interventions that slow or even stop further. An emerging area of research in ageing and

dementia is the characterization of subjective feelings of cognitive impairment and the

development of dementia and effects upon behaviour, daily living and social interaction

irrespective of aetiology (Torrens-Burton et al., 2017).

Methods

Participants

Participants included a group of younger (n =52) undergraduates chosen from the

psychology department at the University, with 31 females and 21 males (mean 19.9; s.d. 1.6;

range 18 to 25 years) and older adults (n =52) recruited from the general public, 32 females and

20 males (mean 66.5; s.d. 4.5; range 50 to 80 years). Exclusion criteria included severe

depression, poor self-reported general health; history of head injury or neurological, medical, or

psychological problems; medically diagnosed subjective cognitive impairment and self-reported

medications that impact cognitive functioning. All had normal or corrected to normal vision and

hearing.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

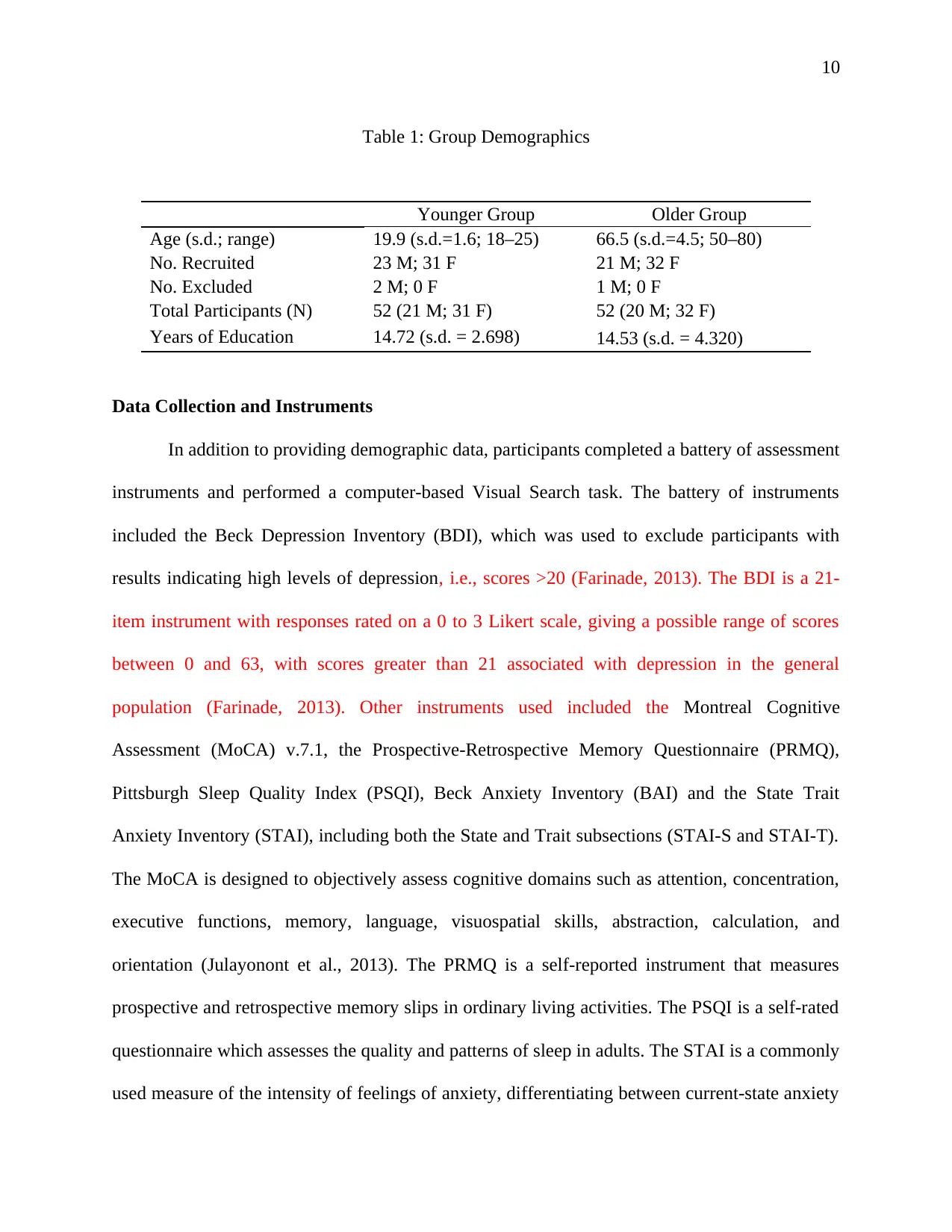

Table 1: Group Demographics

Younger Group Older Group

Age (s.d.; range) 19.9 (s.d.=1.6; 18–25) 66.5 (s.d.=4.5; 50–80)

No. Recruited 23 M; 31 F 21 M; 32 F

No. Excluded 2 M; 0 F 1 M; 0 F

Total Participants (N) 52 (21 M; 31 F) 52 (20 M; 32 F)

Years of Education 14.72 (s.d. = 2.698) 14.53 (s.d. = 4.320)

Data Collection and Instruments

In addition to providing demographic data, participants completed a battery of assessment

instruments and performed a computer-based Visual Search task. The battery of instruments

included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which was used to exclude participants with

results indicating high levels of depression, i.e., scores >20 (Farinade, 2013). The BDI is a 21-

item instrument with responses rated on a 0 to 3 Likert scale, giving a possible range of scores

between 0 and 63, with scores greater than 21 associated with depression in the general

population (Farinade, 2013). Other instruments used included the Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MoCA) v.7.1, the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ),

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the State Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI), including both the State and Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T).

The MoCA is designed to objectively assess cognitive domains such as attention, concentration,

executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction, calculation, and

orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The PRMQ is a self-reported instrument that measures

prospective and retrospective memory slips in ordinary living activities. The PSQI is a self-rated

questionnaire which assesses the quality and patterns of sleep in adults. The STAI is a commonly

used measure of the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-state anxiety

Table 1: Group Demographics

Younger Group Older Group

Age (s.d.; range) 19.9 (s.d.=1.6; 18–25) 66.5 (s.d.=4.5; 50–80)

No. Recruited 23 M; 31 F 21 M; 32 F

No. Excluded 2 M; 0 F 1 M; 0 F

Total Participants (N) 52 (21 M; 31 F) 52 (20 M; 32 F)

Years of Education 14.72 (s.d. = 2.698) 14.53 (s.d. = 4.320)

Data Collection and Instruments

In addition to providing demographic data, participants completed a battery of assessment

instruments and performed a computer-based Visual Search task. The battery of instruments

included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which was used to exclude participants with

results indicating high levels of depression, i.e., scores >20 (Farinade, 2013). The BDI is a 21-

item instrument with responses rated on a 0 to 3 Likert scale, giving a possible range of scores

between 0 and 63, with scores greater than 21 associated with depression in the general

population (Farinade, 2013). Other instruments used included the Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MoCA) v.7.1, the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ),

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the State Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI), including both the State and Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T).

The MoCA is designed to objectively assess cognitive domains such as attention, concentration,

executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction, calculation, and

orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The PRMQ is a self-reported instrument that measures

prospective and retrospective memory slips in ordinary living activities. The PSQI is a self-rated

questionnaire which assesses the quality and patterns of sleep in adults. The STAI is a commonly

used measure of the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-state anxiety

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

in the present moment and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive situations as

threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two scales, the STAI-S

Anxiety scale evaluates current state of anxiety, and the STAI-T Anxiety scale evaluates general,

long-lasting feelings of anxiety. The STAI is highly reliable in both scales, and across a variety

of samples, including older adults, working adults, general population, students, and others

(McDowell, 2006). The BAI measure is designed to distinguish between anxiety and depression

using a 21-item instrument with a 4-point Likert scale range, between 0 to 3. Total scores range

between 0 and 63, with scores between 0–9 indicating normal or no anxiety, 10–18 indicating

mild anxiety levels, 19–29 indicating moderate to severe anxiety, and 30 or greater indicating

severe anxiety (Julian, 2011).

Visual Search Task

For the purpose of computer-based visual search task, time which is taken to respond the

target in the context of isolation and irrelevant as well as distracting stimuli was determined. All

such investigation was conducted on a Dell Precision PC running Windows XP X86 CPU,

viewed at a distance of 57 cm. In order to meet the goals and objectives all trials were made

including black target. In this task, participants were shown a specific figure, either a left-

pointing or a right-pointing arrow. They were asked to determine whether the arrow pointed left

or right. The target appeared alone 8 times at each of the locations around the circle and 8 times

when it was surrounded by 7 distracting figures as shown in Figure 1. For recording time that is

taken for position the target when it is appeared alone and with 7 distracters clock face

configuration was used. In this, total number of 64 trials were made in which target is appearing

8 times at every clock face locations. Under half of the trials, distracters were presented, whereas

in the present moment and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive situations as

threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two scales, the STAI-S

Anxiety scale evaluates current state of anxiety, and the STAI-T Anxiety scale evaluates general,

long-lasting feelings of anxiety. The STAI is highly reliable in both scales, and across a variety

of samples, including older adults, working adults, general population, students, and others

(McDowell, 2006). The BAI measure is designed to distinguish between anxiety and depression

using a 21-item instrument with a 4-point Likert scale range, between 0 to 3. Total scores range

between 0 and 63, with scores between 0–9 indicating normal or no anxiety, 10–18 indicating

mild anxiety levels, 19–29 indicating moderate to severe anxiety, and 30 or greater indicating

severe anxiety (Julian, 2011).

Visual Search Task

For the purpose of computer-based visual search task, time which is taken to respond the

target in the context of isolation and irrelevant as well as distracting stimuli was determined. All

such investigation was conducted on a Dell Precision PC running Windows XP X86 CPU,

viewed at a distance of 57 cm. In order to meet the goals and objectives all trials were made

including black target. In this task, participants were shown a specific figure, either a left-

pointing or a right-pointing arrow. They were asked to determine whether the arrow pointed left

or right. The target appeared alone 8 times at each of the locations around the circle and 8 times

when it was surrounded by 7 distracting figures as shown in Figure 1. For recording time that is

taken for position the target when it is appeared alone and with 7 distracters clock face

configuration was used. In this, total number of 64 trials were made in which target is appearing

8 times at every clock face locations. Under half of the trials, distracters were presented, whereas

12

as in the remaining case not. In the left image in the figure, the target arrow pointed left; in the

right image, the target arrow (in the lower left of the image) pointed right. Separate data was kept

for trials that included both the presence and absence of distracters to determine the size of the

impact of the distracters on the RTs. The central cross in the image appeared 1000 msec. prior to

the target arrows and distractors. Participants fixed their gaze on the central cross and responded

by pressing either the left < key or the right > key as quickly as possible while still maintaining

accuracy. Participants had a practice block of up to 10 trials to ensure they understood the task.

They received no feedback on the accuracy of their responses. About 64 trials were completed in

a single block unless the participant specifically requested a break.

Figure 1. An example of the visual search task with and without distracters

Incorrect responses, those obviously due to a lapse of concentration or disturbance, and

those with times less than 150 msec. (the “normal” RT expected) were excluded from the data.

The data analysis generated the participant’s median RTs for the target by itself and for the target

with distractors. Those individual RTs combined to create group mean RTs.

as in the remaining case not. In the left image in the figure, the target arrow pointed left; in the

right image, the target arrow (in the lower left of the image) pointed right. Separate data was kept

for trials that included both the presence and absence of distracters to determine the size of the

impact of the distracters on the RTs. The central cross in the image appeared 1000 msec. prior to

the target arrows and distractors. Participants fixed their gaze on the central cross and responded

by pressing either the left < key or the right > key as quickly as possible while still maintaining

accuracy. Participants had a practice block of up to 10 trials to ensure they understood the task.

They received no feedback on the accuracy of their responses. About 64 trials were completed in

a single block unless the participant specifically requested a break.

Figure 1. An example of the visual search task with and without distracters

Incorrect responses, those obviously due to a lapse of concentration or disturbance, and

those with times less than 150 msec. (the “normal” RT expected) were excluded from the data.

The data analysis generated the participant’s median RTs for the target by itself and for the target

with distractors. Those individual RTs combined to create group mean RTs.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 32

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.