Evaluating Art Therapy's Potential for UK Armed Forces Mental Health

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/07

|8

|6867

|30

Essay

AI Summary

This essay, originally published in the International Journal of Art Therapy, evaluates the potential application of art therapy within the UK Ministry of Defence's Department of Community Mental Health (DCMH) to address the mental health needs of UK Armed Forces personnel. It begins by considering the prevalence of mental health problems in the Armed Forces compared to the general UK population and details the current treatment pathways available. The paper reviews existing literature on art therapy for similar client groups, including UK veterans and military personnel in other countries, specifically highlighting the work of Combat Stress and research from the US, Russia, and Israel. The author hypothesizes that art therapy could be a suitable treatment option for UK Armed Forces personnel and proposes that formal research be undertaken to determine its efficacy within the DCMH. The essay also provides definitions of key terms, outlines the principles of art therapy, and contrasts it with current practices within the Defence Medical Service (DMS). The research suggests art therapy could offer a valuable addition to the mental healthcare available to military personnel.

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rart20

International Journal of Art Therapy

Formerly Inscape

ISSN: 1745-4832 (Print) 1745-4840 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rart20

Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence Department

of Community Mental Health

Rachel Preston

To cite this article: Rachel Preston (2019): Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the United

Kingdom Ministry of Defence Department of Community Mental Health, International Journal of Art

Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

Published online: 10 Sep 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 11

View related articles

View Crossmark data

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rart20

International Journal of Art Therapy

Formerly Inscape

ISSN: 1745-4832 (Print) 1745-4840 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rart20

Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence Department

of Community Mental Health

Rachel Preston

To cite this article: Rachel Preston (2019): Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the United

Kingdom Ministry of Defence Department of Community Mental Health, International Journal of Art

Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

Published online: 10 Sep 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 11

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ESSAY PRIZE WINNER

Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the United Kingdom Ministry of

Defence Department of Community Mental Health

Rachel Preston

ABSTRACT

UK Armed Forces personnel experiencing mental health difficulties are not,at present,offered

art therapy as a treatmentoption.This paperconsiders the prevalence ofmentalhealth

problems for personnelcurrently serving in the Armed Forces compared with the UK general

population.The current treatment pathway for UK Armed Forces personnelis explained and

compared with a review ofliterature regarding arttherapy forthe similarclientgroups;

veterans in the UK and,military personnelin the United States,Russia and Israel.Much of

the UK media discussion aboutmilitary mentalhealth focuseson Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder(PTSD).The veterans charity CombatStress (along-side othercharities)carries out

vitalwork with PSTD sufferers.However,it is highlighted that PTSD is not the most prevalent

mentalhealth presentation forUK Armed Forcespersonnel.It is hypothesised thatart

therapy could be a suitable treatmentoption forUK Armed Forces personnelwith mental

health issues and it is proposed that formalresearch should be undertaken,to determine the

efficacy of art therapy with this client group at one of the Ministry of Defence Departments

of Community Mental Health.

Plain-language summary

Definitions:

• UK Armed Forces: Personnel currently serving in the UK military in either; the Army, Royal Navy,

Royal Marines or the RoyalAir Force.

• Veteran: A person who has left the Armed Forces having previously served for at least one full

day.

• Combat Stress:A UK based charity providing mental health support for veterans.

UK Armed Forces personnel experiencing mental health difficulties are not,at present,offered

art therapy as a treatment option at any ofthe Ministry ofDefence (MoD)Departments of

Community MentalHealth (DCMH).This paperprovidesa brief overview ofart therapy

before considering the prevalence of mentalhealth problems for personnelcurrently serving

in the UK Armed Forces compared with the UK generalpopulation.The current treatment

pathway for serving personnelis explained and compared to a review of literature regarding

art therapy forveteransin the UK predominantly looking atthe art therapy workshops

conducted by the charity Combat Stress with lead arttherapist Janice Lobban.The author

also considered papers submitted concerning art therapy for military personnelin the United

States,Russia and Israel.In addition she looked at the report from the AllParty Parliamentary

Group forArts in Health and Wellbeing.In conclusion,it is hypothesised thatart therapy

could be a suitable treatmentoption forthe UK Armed Forces.The authorproposes that

formalresearch could be undertaken,to determine the efficacy of art therapy with an Armed

Forces client group at one of the Ministry of Defence Departments of Community Mental Health.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 17 December 2018

Accepted 24 July 2019

KEYWORDS

Art therapy;Armed Forces;

mental health; Department of

Community MentalHealth;

DCMH;veterans;military

Introduction

This article discusses the potential use of art therapy in

the Ministry ofDefence (MoD)specialistoutpatient

mentalhealth service(Departmentof Community

MentalHealth (DCMH)).Like the UK generalpopu-

lation,service personnelencountersituations which

affect their mentalwellbeing.Most are able to adopt

appropriate coping strategies:nevertheless,a small

percentage (DefStats (Health),2017)need a greater

levelof mentalhealth support.The MoD has a clear

strategy regarding mentalhealth and wellbeing for

the Armed Forces (MoD,2017).However,it does not

include the use of art therapy (Lobban,2016b).Using

evidencerelating to the use of art therapywith

similar client groups;UK veterans and military person-

nel in other countries, it is recommended that a clinical

trialof art therapy could be undertaken within DCMH

to ascertain ifUK Armed Forcespersonnelwould

benefit from art therapy as a treatment option.

What is art therapy?

The British Association ofArt Therapy describes art

therapy as:

© 2019 British Association of Art Therapists

CONTACT RachelPreston r.preston3@unimail.derby.ac.uk

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY

https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

Assessing the potential use of art therapy in the United Kingdom Ministry of

Defence Department of Community Mental Health

Rachel Preston

ABSTRACT

UK Armed Forces personnel experiencing mental health difficulties are not,at present,offered

art therapy as a treatmentoption.This paperconsiders the prevalence ofmentalhealth

problems for personnelcurrently serving in the Armed Forces compared with the UK general

population.The current treatment pathway for UK Armed Forces personnelis explained and

compared with a review ofliterature regarding arttherapy forthe similarclientgroups;

veterans in the UK and,military personnelin the United States,Russia and Israel.Much of

the UK media discussion aboutmilitary mentalhealth focuseson Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder(PTSD).The veterans charity CombatStress (along-side othercharities)carries out

vitalwork with PSTD sufferers.However,it is highlighted that PTSD is not the most prevalent

mentalhealth presentation forUK Armed Forcespersonnel.It is hypothesised thatart

therapy could be a suitable treatmentoption forUK Armed Forces personnelwith mental

health issues and it is proposed that formalresearch should be undertaken,to determine the

efficacy of art therapy with this client group at one of the Ministry of Defence Departments

of Community Mental Health.

Plain-language summary

Definitions:

• UK Armed Forces: Personnel currently serving in the UK military in either; the Army, Royal Navy,

Royal Marines or the RoyalAir Force.

• Veteran: A person who has left the Armed Forces having previously served for at least one full

day.

• Combat Stress:A UK based charity providing mental health support for veterans.

UK Armed Forces personnel experiencing mental health difficulties are not,at present,offered

art therapy as a treatment option at any ofthe Ministry ofDefence (MoD)Departments of

Community MentalHealth (DCMH).This paperprovidesa brief overview ofart therapy

before considering the prevalence of mentalhealth problems for personnelcurrently serving

in the UK Armed Forces compared with the UK generalpopulation.The current treatment

pathway for serving personnelis explained and compared to a review of literature regarding

art therapy forveteransin the UK predominantly looking atthe art therapy workshops

conducted by the charity Combat Stress with lead arttherapist Janice Lobban.The author

also considered papers submitted concerning art therapy for military personnelin the United

States,Russia and Israel.In addition she looked at the report from the AllParty Parliamentary

Group forArts in Health and Wellbeing.In conclusion,it is hypothesised thatart therapy

could be a suitable treatmentoption forthe UK Armed Forces.The authorproposes that

formalresearch could be undertaken,to determine the efficacy of art therapy with an Armed

Forces client group at one of the Ministry of Defence Departments of Community Mental Health.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 17 December 2018

Accepted 24 July 2019

KEYWORDS

Art therapy;Armed Forces;

mental health; Department of

Community MentalHealth;

DCMH;veterans;military

Introduction

This article discusses the potential use of art therapy in

the Ministry ofDefence (MoD)specialistoutpatient

mentalhealth service(Departmentof Community

MentalHealth (DCMH)).Like the UK generalpopu-

lation,service personnelencountersituations which

affect their mentalwellbeing.Most are able to adopt

appropriate coping strategies:nevertheless,a small

percentage (DefStats (Health),2017)need a greater

levelof mentalhealth support.The MoD has a clear

strategy regarding mentalhealth and wellbeing for

the Armed Forces (MoD,2017).However,it does not

include the use of art therapy (Lobban,2016b).Using

evidencerelating to the use of art therapywith

similar client groups;UK veterans and military person-

nel in other countries, it is recommended that a clinical

trialof art therapy could be undertaken within DCMH

to ascertain ifUK Armed Forcespersonnelwould

benefit from art therapy as a treatment option.

What is art therapy?

The British Association ofArt Therapy describes art

therapy as:

© 2019 British Association of Art Therapists

CONTACT RachelPreston r.preston3@unimail.derby.ac.uk

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY

https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1650786

… a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its

primarymode of expression and communication.

Within this context,art is not used as a diagnostic

tool but as a medium to address emotionalissues

which may be confusing and distressing.

Art therapists work with children, young people, adults

and the elderly.Clients may have a wide range of

difficulties,disabilitiesor diagnoses.These include

emotional,behaviouralor mentalhealth problems,

learning or physical disabilities, life-limiting conditions,

neurologicalconditions and physicalillnesses.(BAAT,

2019)

The interchangeabletitles Art Therapist/ArtPsy-

chotherapistare protected termsand membersof

this profession must have completed mandatory train-

ing at Masters Level on a course validated by the Health

and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and they must be

registered with the HCPC to practice (BAAT, 2019). Prac-

ticing arttherapists mustcontinue to engage in rel-

evant continuousprofessionaldevelopmentand

engage in regular clinicalsupervision to maintain the

safety and quality of their practice.

Art therapy may be used as an intervention with

individuals orgroups.Art therapists employ a range

of theoreticaltherapeuticapproacheswhich are

adapted to an arttherapy perspective as explained

by Hogan (2016),including;cognitive behaviouralart

therapy;solution-focused brief therapy;psychoanalyti-

cal (Freudian)art therapy;analytical(Jungian)art

therapy;Gestalt art therapy;person centred (Rogerian)

art therapy;mindfulnessart therapy;integrative art

therapy (the group-interactive model)and feminist

art therapy.Each art therapist employs the theoretical

model(s)that suits their,or their employing organis-

ation’s,preferred style and which,in practice,the pro-

vider finds works best with their client or group.

There is no one-size-fits-allapproach which makes

comparing treatment outcomes difficult.

Art therapy/psychotherapy is an intervention that

considerswhat is happening forthe clientin their

unconsciousthought processes.Neurosciencehas

shown thatexperience is captured by the senses as

images,smells,soundsand feelings(Van derKolk,

2014).Difficult or traumatic memories which have not

been processedcognitivelycan have a negative

effect on the emotions or behaviour of the individual,

howeverthe image making processes in arttherapy

can be used to help in reprocessing these memories

(Edwards,2014).

Art therapistsare recognised in the UK National

Health Service (NHS)as Allied Health Professionals.

They are employed in a varietyof settings;NHS,

social services,mainstream and specialeducation,

prisons, secure and residential care homes, within char-

ities,at galleries and museums,and,in private practice

(BAAT,2019).

Armed Forces mental health treatment

The Armed Forces have theirown Defence Medical

Service (DMS),which has close links with the Depart-

ment of Health and the NHS.Personnelexperiencing

mentalhealth issues are initially seen by their Medical

Officer (equivalent ofa GeneralPractitioner)and are

either treated locally or referred to one of sixteen mili-

tary Departments of Community Mental Health (DCMH)

providing outpatientmentalhealth care in the UK.

Inpatient care,if required,is provided under contract

by a consortium of NHS trusts (Hacker Hughes,2017).

The DCMH operate asa multi-disciplinary team

(MDT) staffed by a mix of military and civilian;mental

health nurses,psychologists,psychiatrists and mental

health socialworkers.Clinicians decide on the most

appropriate treatment for each individualwhich may

include prescribing pharmacologicalsupportand/or

engaging in a talking therapy.Most membersof

DCMH staff are trained in cognitivebehavioural

therapy (CBT)(Alford & Beck,1997)and some are

trained to deliver eye movement desensitising and pro-

cessing (EMDR) (Shapiro & Forrester, 1998) for the treat-

mentof trauma.Both these treatments are used in

accordance with the NationalInstitute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE)Guidelines (NICE,2015).Treat-

mentis delivered as an out-patientservice once or

twice a week (Hacker Hughes,2017).There is no evi-

dence thatart therapyis a treatmentoffered by

DCMH (Lobban,2016b).It could be inferred that this

is because arttherapy isnot listed asa treatment

option in the Nice Guidelines.However,that argument

becomes self-fulfilling – arttherapy is notprovided,

therefore,research on its efficacy is notconducted.

Ergo,there is no evidence on which to recommend

art therapy as a treatmentoption.If DCMH were to

employ an arttherapistit is likely they would form

part ofthe MDT as they would in a NHS community

mentalhealth team.Concurrently,research into the

potentialbenefits ofart therapy as a psychological

intervention could be conducted.The DMS might con-

sider how they could commission and integrate an art

therapy provision in a DCMH for a trialperiod by con-

sulting with otherNHS or charitable providersof

similar interventions.

The MoD produce annual statistics about the Armed

Forces mentalhealth (DefStats (Health),2017).The

report covering,2016/2017 showed that 3.2% ofthe

Armed Forcespopulation were initially assessed to

have a mentalhealth disorder at their primary DCMH

appointment.This compares with a rate of3.5% in

the UK generalpopulation (NHS Digital,2017).The

DefenceStatistics(Health)report (2017)does not

include those treated locally by their MedicalOfficer.

Trend analysisshows that the numbersinitially

assessed with a mentalhealth disorder in the Armed

2 R.PRESTON

primarymode of expression and communication.

Within this context,art is not used as a diagnostic

tool but as a medium to address emotionalissues

which may be confusing and distressing.

Art therapists work with children, young people, adults

and the elderly.Clients may have a wide range of

difficulties,disabilitiesor diagnoses.These include

emotional,behaviouralor mentalhealth problems,

learning or physical disabilities, life-limiting conditions,

neurologicalconditions and physicalillnesses.(BAAT,

2019)

The interchangeabletitles Art Therapist/ArtPsy-

chotherapistare protected termsand membersof

this profession must have completed mandatory train-

ing at Masters Level on a course validated by the Health

and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and they must be

registered with the HCPC to practice (BAAT, 2019). Prac-

ticing arttherapists mustcontinue to engage in rel-

evant continuousprofessionaldevelopmentand

engage in regular clinicalsupervision to maintain the

safety and quality of their practice.

Art therapy may be used as an intervention with

individuals orgroups.Art therapists employ a range

of theoreticaltherapeuticapproacheswhich are

adapted to an arttherapy perspective as explained

by Hogan (2016),including;cognitive behaviouralart

therapy;solution-focused brief therapy;psychoanalyti-

cal (Freudian)art therapy;analytical(Jungian)art

therapy;Gestalt art therapy;person centred (Rogerian)

art therapy;mindfulnessart therapy;integrative art

therapy (the group-interactive model)and feminist

art therapy.Each art therapist employs the theoretical

model(s)that suits their,or their employing organis-

ation’s,preferred style and which,in practice,the pro-

vider finds works best with their client or group.

There is no one-size-fits-allapproach which makes

comparing treatment outcomes difficult.

Art therapy/psychotherapy is an intervention that

considerswhat is happening forthe clientin their

unconsciousthought processes.Neurosciencehas

shown thatexperience is captured by the senses as

images,smells,soundsand feelings(Van derKolk,

2014).Difficult or traumatic memories which have not

been processedcognitivelycan have a negative

effect on the emotions or behaviour of the individual,

howeverthe image making processes in arttherapy

can be used to help in reprocessing these memories

(Edwards,2014).

Art therapistsare recognised in the UK National

Health Service (NHS)as Allied Health Professionals.

They are employed in a varietyof settings;NHS,

social services,mainstream and specialeducation,

prisons, secure and residential care homes, within char-

ities,at galleries and museums,and,in private practice

(BAAT,2019).

Armed Forces mental health treatment

The Armed Forces have theirown Defence Medical

Service (DMS),which has close links with the Depart-

ment of Health and the NHS.Personnelexperiencing

mentalhealth issues are initially seen by their Medical

Officer (equivalent ofa GeneralPractitioner)and are

either treated locally or referred to one of sixteen mili-

tary Departments of Community Mental Health (DCMH)

providing outpatientmentalhealth care in the UK.

Inpatient care,if required,is provided under contract

by a consortium of NHS trusts (Hacker Hughes,2017).

The DCMH operate asa multi-disciplinary team

(MDT) staffed by a mix of military and civilian;mental

health nurses,psychologists,psychiatrists and mental

health socialworkers.Clinicians decide on the most

appropriate treatment for each individualwhich may

include prescribing pharmacologicalsupportand/or

engaging in a talking therapy.Most membersof

DCMH staff are trained in cognitivebehavioural

therapy (CBT)(Alford & Beck,1997)and some are

trained to deliver eye movement desensitising and pro-

cessing (EMDR) (Shapiro & Forrester, 1998) for the treat-

mentof trauma.Both these treatments are used in

accordance with the NationalInstitute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE)Guidelines (NICE,2015).Treat-

mentis delivered as an out-patientservice once or

twice a week (Hacker Hughes,2017).There is no evi-

dence thatart therapyis a treatmentoffered by

DCMH (Lobban,2016b).It could be inferred that this

is because arttherapy isnot listed asa treatment

option in the Nice Guidelines.However,that argument

becomes self-fulfilling – arttherapy is notprovided,

therefore,research on its efficacy is notconducted.

Ergo,there is no evidence on which to recommend

art therapy as a treatmentoption.If DCMH were to

employ an arttherapistit is likely they would form

part ofthe MDT as they would in a NHS community

mentalhealth team.Concurrently,research into the

potentialbenefits ofart therapy as a psychological

intervention could be conducted.The DMS might con-

sider how they could commission and integrate an art

therapy provision in a DCMH for a trialperiod by con-

sulting with otherNHS or charitable providersof

similar interventions.

The MoD produce annual statistics about the Armed

Forces mentalhealth (DefStats (Health),2017).The

report covering,2016/2017 showed that 3.2% ofthe

Armed Forcespopulation were initially assessed to

have a mentalhealth disorder at their primary DCMH

appointment.This compares with a rate of3.5% in

the UK generalpopulation (NHS Digital,2017).The

DefenceStatistics(Health)report (2017)does not

include those treated locally by their MedicalOfficer.

Trend analysisshows that the numbersinitially

assessed with a mentalhealth disorder in the Armed

2 R.PRESTON

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Forces have increased from 1.8% in 2007/2008.The

reportexplains thatthe increase may be a resultof

campaigns by the MoD to reduce stigma surrounding

mentalhealth,leading to individualsfeeling more

able to report to primarycare for help (Jones,

Campion,Keeling,& Greenberg,2018).

The statistics (Def Stats (Health),2017) show that of

those personnelassessed with a mentaldisorderat

initial presentation:63% presented with a neurotic dis-

order (32% adjustment disorder, 25% other neurotic dis-

orders and 6% post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)),

33%with a mood disorder,4% with psychoactive sub-

stance misuse and the remaining 2% presented with

other mental health disorders.Despite common

media reporting,statistically,PSTD is shown to be a

comparativelylow occurrence equating to two in

1,000 personnelwho are currently serving in the UK

Armed Forces (DefStats (Health),2017).This may be

due to a reluctance ofservice personnelwanting to

admit they have a problem.The charity Combat Stress

(Combat Stress,2019) reports that on average it takes

13 years from leaving the military for a veteran to seek

their help for mentalhealth problems.It may also be

because the Armed Forces have a robustsystem in

place to manage operational stress which includes pre

and post deployment exercises,briefings and decom-

pression tasks(Jones,Burdett,Green,& Greenberg,

2017). They also use a cadre of trained Trauma Risk Man-

agement (TRiM) practitioners and leaders from within

their own ranks to assessand manage personnel

involved in stressfuland potentially traumatic events

(Greenberg,Langston,& Jones,2008).This allows indi-

viduals to talk to a peer and process distressing events

shortly after the event takes place.When an individual

is experiencing difficultiesin coping with the after

effects of an event the TRiM practitioner is able to sign-

post to appropriate supportavailable from trained

medical or welfare staff (Jones, Burdett, et al., 2017).

The aim of medical support in the Armed Forces is to

get individuals back to operationalfitness as expedi-

ently as possible.It is acknowledged thatthere are

roles in the Armed Forceswhere returning to full

time duty while experiencing mentalill health carries

a risk. Therefore,the medicalofficerwill consider

imposing employmentlimitationsthat mitigate the

risks.This enables the service person to be employed

to the best of their ability while attending out-patient

appointments.The limitations are lifted once the indi-

vidualhas recovered (Defence MedicalService,2017).

Service personnelwho are unable to work due to

injury or illness be it physical or mental will be reviewed

by their unit medical officer and/or their specialist care

team and a determination willbe made about how to

manage their care while the individual is on long term

sickness absence (Defence Medical Service, 2017). They

might be referred to one of the recovery centres which

are funded by both charitable and public money as

part of the Defence RecoveryCapability(NHS

Choices,2015).The centres do not employ art thera-

pists but they do employ occupationaltherapists and

provide a variety of creative activity workshops (such

as art,woodturning,stone carving and horticulture)

with facilitators drawn from each particularcreative

discipline.The workshops are accessed by both in-

patientsand out-patients,and it is recognised that

these activitieshave a therapeutic effect(Help for

Heroes,2017).

In cases where return to duty is notfeasible the

Service person is supported by a care team in their

transition to civilian living.On leaving the Armed

Forces, medical care is transferred to the NHS. NHS pro-

viders have funded specialist veteran units as part of

the UK government’scommitmentto the Armed

ForcesCovenantin recognition thatsome veterans

need additionalsupport(Ashcroft,2014).In addition

there are many charities dedicated to supporting the

Armed Forces and Veteran community (COBSEO, 2017).

Art therapy research with veterans in the UK

and the US

The charity,CombatStress(CombatStress,2019),

specialisesin the care of UK veteranswith mental

health issues.They employed theirfirstart therapist

in 2001 (Lobban,2017).Lobban has written a number

of papers aboutart therapy with the veteran client

group (Lobban,2014,2016a,2016b,2017).She has

also published a book detailing the framework she

uses in her work with veterans(Lobban,2017).

Further,she has been the subject ofa video relating

to the provision ofart therapy to veterans (McArdle,

2011).Notwithstanding the low prevalence ofPTSD

reported by the MoD (DefStats (Health),2017),art

therapy at Combat Stress focuses primarily on clients

who are experiencing complex PTSD recognising that

formaldiagnosis ofthe condition may notbe made

untilafter the individualleaves the Armed Forces as

sometimes,accessingtreatmentcan take years

(Lobban,2017).

Combatstressdeliverart therapyat residential

centres where veterans also have access to a number

of other clinicians and they are also able to socialise

and share their experiences with other former Serving

personnel which contributes to feelings of community

and bonding (Lobban, 2017). The Intensive PTSD Treat-

ment Programme (ITP) has NationalSpecialised Com-

missioning from the Department ofHealth,it is a six

week programme with a number of psychological treat-

ments conducted in groups and individual therapy ses-

sions.Art therapy group sessions are a mandatory part

of the programme and last 75 min, once a week (six ses-

sions in total). Art is made in response to a theme. After-

wardsreflection and discussion around the images

takesplace (Lobban,2017).Evidenceof Lobban’s

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY 3

reportexplains thatthe increase may be a resultof

campaigns by the MoD to reduce stigma surrounding

mentalhealth,leading to individualsfeeling more

able to report to primarycare for help (Jones,

Campion,Keeling,& Greenberg,2018).

The statistics (Def Stats (Health),2017) show that of

those personnelassessed with a mentaldisorderat

initial presentation:63% presented with a neurotic dis-

order (32% adjustment disorder, 25% other neurotic dis-

orders and 6% post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)),

33%with a mood disorder,4% with psychoactive sub-

stance misuse and the remaining 2% presented with

other mental health disorders.Despite common

media reporting,statistically,PSTD is shown to be a

comparativelylow occurrence equating to two in

1,000 personnelwho are currently serving in the UK

Armed Forces (DefStats (Health),2017).This may be

due to a reluctance ofservice personnelwanting to

admit they have a problem.The charity Combat Stress

(Combat Stress,2019) reports that on average it takes

13 years from leaving the military for a veteran to seek

their help for mentalhealth problems.It may also be

because the Armed Forces have a robustsystem in

place to manage operational stress which includes pre

and post deployment exercises,briefings and decom-

pression tasks(Jones,Burdett,Green,& Greenberg,

2017). They also use a cadre of trained Trauma Risk Man-

agement (TRiM) practitioners and leaders from within

their own ranks to assessand manage personnel

involved in stressfuland potentially traumatic events

(Greenberg,Langston,& Jones,2008).This allows indi-

viduals to talk to a peer and process distressing events

shortly after the event takes place.When an individual

is experiencing difficultiesin coping with the after

effects of an event the TRiM practitioner is able to sign-

post to appropriate supportavailable from trained

medical or welfare staff (Jones, Burdett, et al., 2017).

The aim of medical support in the Armed Forces is to

get individuals back to operationalfitness as expedi-

ently as possible.It is acknowledged thatthere are

roles in the Armed Forceswhere returning to full

time duty while experiencing mentalill health carries

a risk. Therefore,the medicalofficerwill consider

imposing employmentlimitationsthat mitigate the

risks.This enables the service person to be employed

to the best of their ability while attending out-patient

appointments.The limitations are lifted once the indi-

vidualhas recovered (Defence MedicalService,2017).

Service personnelwho are unable to work due to

injury or illness be it physical or mental will be reviewed

by their unit medical officer and/or their specialist care

team and a determination willbe made about how to

manage their care while the individual is on long term

sickness absence (Defence Medical Service, 2017). They

might be referred to one of the recovery centres which

are funded by both charitable and public money as

part of the Defence RecoveryCapability(NHS

Choices,2015).The centres do not employ art thera-

pists but they do employ occupationaltherapists and

provide a variety of creative activity workshops (such

as art,woodturning,stone carving and horticulture)

with facilitators drawn from each particularcreative

discipline.The workshops are accessed by both in-

patientsand out-patients,and it is recognised that

these activitieshave a therapeutic effect(Help for

Heroes,2017).

In cases where return to duty is notfeasible the

Service person is supported by a care team in their

transition to civilian living.On leaving the Armed

Forces, medical care is transferred to the NHS. NHS pro-

viders have funded specialist veteran units as part of

the UK government’scommitmentto the Armed

ForcesCovenantin recognition thatsome veterans

need additionalsupport(Ashcroft,2014).In addition

there are many charities dedicated to supporting the

Armed Forces and Veteran community (COBSEO, 2017).

Art therapy research with veterans in the UK

and the US

The charity,CombatStress(CombatStress,2019),

specialisesin the care of UK veteranswith mental

health issues.They employed theirfirstart therapist

in 2001 (Lobban,2017).Lobban has written a number

of papers aboutart therapy with the veteran client

group (Lobban,2014,2016a,2016b,2017).She has

also published a book detailing the framework she

uses in her work with veterans(Lobban,2017).

Further,she has been the subject ofa video relating

to the provision ofart therapy to veterans (McArdle,

2011).Notwithstanding the low prevalence ofPTSD

reported by the MoD (DefStats (Health),2017),art

therapy at Combat Stress focuses primarily on clients

who are experiencing complex PTSD recognising that

formaldiagnosis ofthe condition may notbe made

untilafter the individualleaves the Armed Forces as

sometimes,accessingtreatmentcan take years

(Lobban,2017).

Combatstressdeliverart therapyat residential

centres where veterans also have access to a number

of other clinicians and they are also able to socialise

and share their experiences with other former Serving

personnel which contributes to feelings of community

and bonding (Lobban, 2017). The Intensive PTSD Treat-

ment Programme (ITP) has NationalSpecialised Com-

missioning from the Department ofHealth,it is a six

week programme with a number of psychological treat-

ments conducted in groups and individual therapy ses-

sions.Art therapy group sessions are a mandatory part

of the programme and last 75 min, once a week (six ses-

sions in total). Art is made in response to a theme. After-

wardsreflection and discussion around the images

takesplace (Lobban,2017).Evidenceof Lobban’s

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY 3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

experiences of working with this group is detailed in

many published case studies (Lobban,2014,2016a,

2016b,2017b;Lobban & Murphy,2018;Palmer,Hill,

Lobban,& Murphy,2017).Standardised psychological

outcome measures are used at Combat Stress and a

research study of the results suggests that 87 percent

of veterans who completed the programme between

2012 and 2014 saw a reduction in their PTSD symptoms

and co-morbid anxiety and depression,angerand

alcoholuse, and this was maintained attheir six-

month follow-up (Lobban 2017b).

The ITP is in contrastto talking interventionsat

DCMH which may consist of weekly sessions,possibly,

over a more extended time frame either as a standa-

lone intervention or as part of a range of other treat-

ments from the multi-disciplinaryteam (Hacker

Hughes,2017).

During 2016,Lobban visited the United States to

meet with art therapistsworking with US veterans

(Lobban,2016b)she studied examples of art therapy

being used to support veterans at the US Department

of Veteran Affairs Healthcare facilities.She also met

art therapists working with serving military personnel

at the NationalIntrepid Center ofExcellence (NICoE),

WalterReed NationalMilitary MedicalCenterand at

Intrepid Spirit One,Fort Belvoir Community Hospital.

In her executive summary Lobban (2016b,p. 5) notes:

Findings reveal that in the US, policy recommendations

have promoted the inclusion of creative arts therapies

within healthcare teams across the military continuum

from pre-deployment/activeduty status to post-

deploymentreintegration and veteran status.US art

therapists have therefore been able to devise innova-

tive programmes to treat a range of mental health pro-

blems including PTSD.Outcomes include:symptom

reduction;resiliencebuilding; increased insight;

reduction of socialisolation;enhanced coping;stimu-

lation of positive emotions.

Following her visit to the USA,Lobban (2016b) made a

number of recommendationssuggesting how art

therapy could be used in a widermilitary context

including in NHS SpecialistVeteran Services,and

Defence Medical ServicesRehabilitation.Lobban

suggested that greater use of public or private partner-

ships could be used;and, also thatinvestmentin

research should take place to provide the evidence

base forart therapy in the military contextthatwill

encourage service commissioning.However,Lobban

does not explicitly recommend art therapy within the

MoD DCMH organisation.

The progress of art therapy with military populations

in the US is captured in a recently published book

(Howie,2017) and many published papers (Alexander,

2015;Campbell,Decker,Kruk,& Deaver,2016;Collie,

Backos,Malchiodi,& Spiegel,2006;Jones et al.,2017

Malchiodi,2016;Salmon & Gerber,1999;Walker,

Kaimal,Gonzaga,Myers-Coffman,& DeGraba,2017;

Walker,Kaimal,Koffman,& DeGraba,2016).Research

on both sides of the Atlantic demonstrates that the out-

comes arttherapists achieve with serving personnel

and veterans, particularly those with PTSD and/or Trau-

matic Brain Injury (TBI) is effective. Indeed, an American

PatientSatisfaction Survey carried outat the NICoE

between November2012 and June 2014 rated art

therapy fifth highest on a list of forty one options for

assisting recovery (Jones et al.,2017).

Other art therapy research with military

personnel

Art therapy research with military personnel is also con-

ducted in other countries.Kopytin and Lebedev (2015)

conducted a study in St Petersburg,Russia with male

soldiers who had seen service in combatareas both

within Russiaand in other global locations.The

research examined the effects of humour in art in the

course of an interactive art therapy group.This study

revealed that humour plays an important role in veter-

an’s art therapyand the frequencyof humorous

responseswas significantly greaterthan in another

similar study of non-veterans (Silver,2002).It was con-

cluded that humour enabled the veterans to engage in

the therapeutic process in a way thathelped them

overcome avoidance,anxiety and resistance using a

method thatenabled them to feelsafe in revealing

underlying tensions(England,Martin,& Rosamond,

2017).The particulartype ofmilitary banter/humour

can make it difficult for service personnel and veterans

to interact with those unused to the military environ-

ment (Busuttil,2017).Kopytin and Lebedev (2015)

highlight the importance of understanding the unspo-

ken culture and language that forms the character and

identity of those who serve in the military.

Harel-Shalev,Huss, Daphna-Tekoah,and Cwikel

(2017)conducted a study aboutthe experiences of

females in support roles in the IsraeliDefence Force.

In theirart therapy study they were able to identify

three themes as the main stressors for women as:the

responsibility for others in life threatening situations;

the military as a firstprofessionalwork experience;

and,the interaction between military and gender hier-

archies.The reported prevalence of mentalhealth dis-

orders in UK Armed Forces women is 6.3% compared

with 2.8% in men (Def Stats (Health),2017).As men-

tioned earlier,there has been considerable focus on

treatmentoptions forPTSD and TBIalthough these

conditionsare, statisticallylow. Def Stats (Health)

(2017) show that more than 90% of initial assessments

at a DCMH are for non PTSD related mental health pro-

blems.It is feasible thatart therapy may also be an

appropriate intervention to supportthe recovery of

these individuals.Having served as a woman in the

UK Armed Forces and having experienced periods of

4 R.PRESTON

many published case studies (Lobban,2014,2016a,

2016b,2017b;Lobban & Murphy,2018;Palmer,Hill,

Lobban,& Murphy,2017).Standardised psychological

outcome measures are used at Combat Stress and a

research study of the results suggests that 87 percent

of veterans who completed the programme between

2012 and 2014 saw a reduction in their PTSD symptoms

and co-morbid anxiety and depression,angerand

alcoholuse, and this was maintained attheir six-

month follow-up (Lobban 2017b).

The ITP is in contrastto talking interventionsat

DCMH which may consist of weekly sessions,possibly,

over a more extended time frame either as a standa-

lone intervention or as part of a range of other treat-

ments from the multi-disciplinaryteam (Hacker

Hughes,2017).

During 2016,Lobban visited the United States to

meet with art therapistsworking with US veterans

(Lobban,2016b)she studied examples of art therapy

being used to support veterans at the US Department

of Veteran Affairs Healthcare facilities.She also met

art therapists working with serving military personnel

at the NationalIntrepid Center ofExcellence (NICoE),

WalterReed NationalMilitary MedicalCenterand at

Intrepid Spirit One,Fort Belvoir Community Hospital.

In her executive summary Lobban (2016b,p. 5) notes:

Findings reveal that in the US, policy recommendations

have promoted the inclusion of creative arts therapies

within healthcare teams across the military continuum

from pre-deployment/activeduty status to post-

deploymentreintegration and veteran status.US art

therapists have therefore been able to devise innova-

tive programmes to treat a range of mental health pro-

blems including PTSD.Outcomes include:symptom

reduction;resiliencebuilding; increased insight;

reduction of socialisolation;enhanced coping;stimu-

lation of positive emotions.

Following her visit to the USA,Lobban (2016b) made a

number of recommendationssuggesting how art

therapy could be used in a widermilitary context

including in NHS SpecialistVeteran Services,and

Defence Medical ServicesRehabilitation.Lobban

suggested that greater use of public or private partner-

ships could be used;and, also thatinvestmentin

research should take place to provide the evidence

base forart therapy in the military contextthatwill

encourage service commissioning.However,Lobban

does not explicitly recommend art therapy within the

MoD DCMH organisation.

The progress of art therapy with military populations

in the US is captured in a recently published book

(Howie,2017) and many published papers (Alexander,

2015;Campbell,Decker,Kruk,& Deaver,2016;Collie,

Backos,Malchiodi,& Spiegel,2006;Jones et al.,2017

Malchiodi,2016;Salmon & Gerber,1999;Walker,

Kaimal,Gonzaga,Myers-Coffman,& DeGraba,2017;

Walker,Kaimal,Koffman,& DeGraba,2016).Research

on both sides of the Atlantic demonstrates that the out-

comes arttherapists achieve with serving personnel

and veterans, particularly those with PTSD and/or Trau-

matic Brain Injury (TBI) is effective. Indeed, an American

PatientSatisfaction Survey carried outat the NICoE

between November2012 and June 2014 rated art

therapy fifth highest on a list of forty one options for

assisting recovery (Jones et al.,2017).

Other art therapy research with military

personnel

Art therapy research with military personnel is also con-

ducted in other countries.Kopytin and Lebedev (2015)

conducted a study in St Petersburg,Russia with male

soldiers who had seen service in combatareas both

within Russiaand in other global locations.The

research examined the effects of humour in art in the

course of an interactive art therapy group.This study

revealed that humour plays an important role in veter-

an’s art therapyand the frequencyof humorous

responseswas significantly greaterthan in another

similar study of non-veterans (Silver,2002).It was con-

cluded that humour enabled the veterans to engage in

the therapeutic process in a way thathelped them

overcome avoidance,anxiety and resistance using a

method thatenabled them to feelsafe in revealing

underlying tensions(England,Martin,& Rosamond,

2017).The particulartype ofmilitary banter/humour

can make it difficult for service personnel and veterans

to interact with those unused to the military environ-

ment (Busuttil,2017).Kopytin and Lebedev (2015)

highlight the importance of understanding the unspo-

ken culture and language that forms the character and

identity of those who serve in the military.

Harel-Shalev,Huss, Daphna-Tekoah,and Cwikel

(2017)conducted a study aboutthe experiences of

females in support roles in the IsraeliDefence Force.

In theirart therapy study they were able to identify

three themes as the main stressors for women as:the

responsibility for others in life threatening situations;

the military as a firstprofessionalwork experience;

and,the interaction between military and gender hier-

archies.The reported prevalence of mentalhealth dis-

orders in UK Armed Forces women is 6.3% compared

with 2.8% in men (Def Stats (Health),2017).As men-

tioned earlier,there has been considerable focus on

treatmentoptions forPTSD and TBIalthough these

conditionsare, statisticallylow. Def Stats (Health)

(2017) show that more than 90% of initial assessments

at a DCMH are for non PTSD related mental health pro-

blems.It is feasible thatart therapy may also be an

appropriate intervention to supportthe recovery of

these individuals.Having served as a woman in the

UK Armed Forces and having experienced periods of

4 R.PRESTON

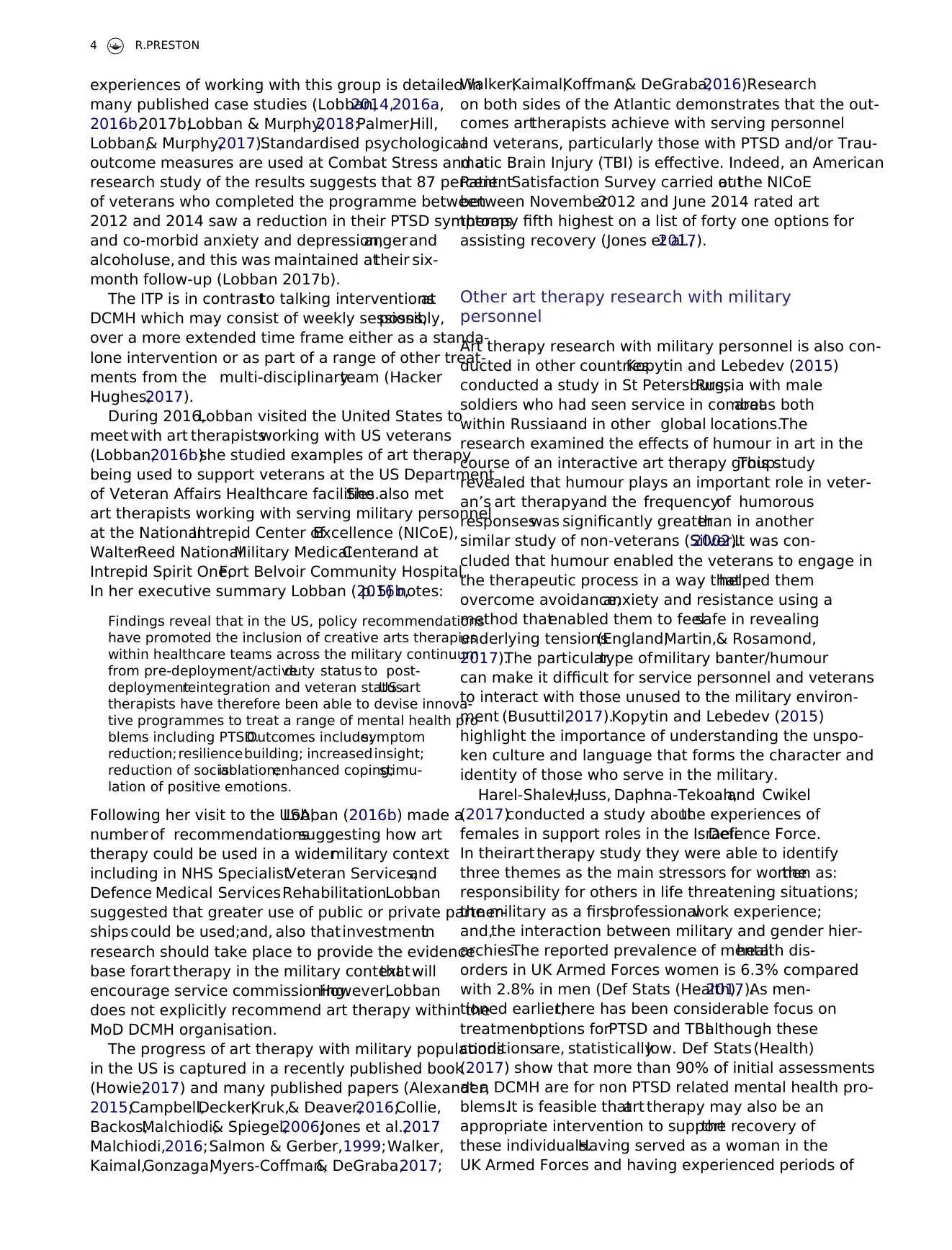

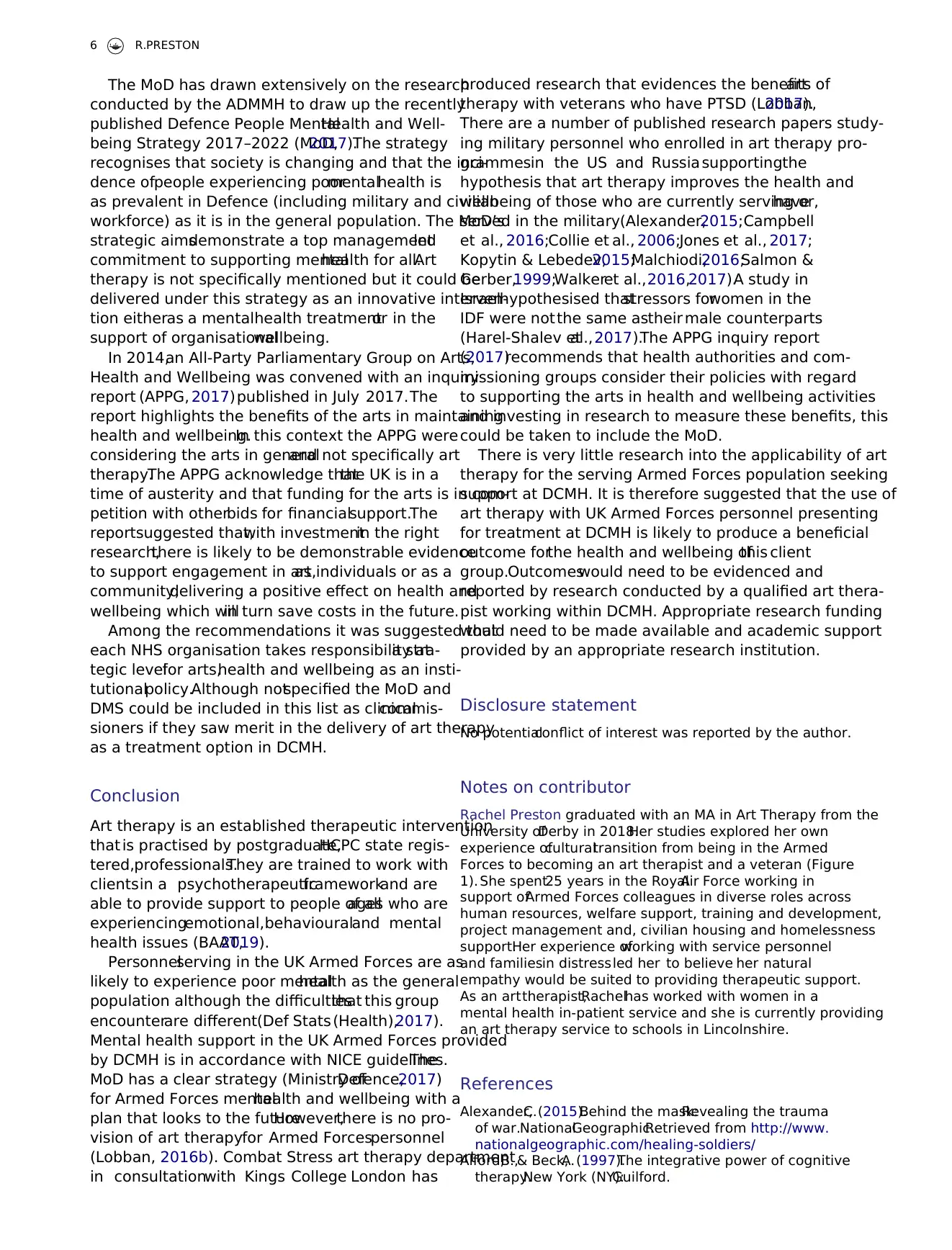

anxiety and depression (Figure 1),the authorfeels

there may be benefitin conducting an arttherapy

study to ascertain some of the stressors that arise for

women in comparison to men in the UK Armed Forces.

Potential research

It has been discussed in this paper that the MoD do not

employ art therapists nor do they use art therapy as a

treatmentintervention formentalhealth conditions.

It is inferred by the author that this is due to the NICE

guideline recommendation thattreatmentfor PTSD

should be CBT followed by EMDR.However,without

employing an arttherapistto conductresearch with

an armed forces personnelclient group,one is never

going to gather the evidence required to change the

recommended treatment.

Evidenceis being gathered bythe UK charity

Combat Stress and at NICoE in the US which suggests

that art therapy is a beneficialtreatment for UK veter-

ans and US military personnelexperiencing PTSD and

TBIs.As yet,art therapy as a treatment option has not

yet been introduced in any ofthe DCMH settings.

This could be explained due to the statistical evidence

gathered (Def Stats (Health), 2017) which suggests that

only 6% ofserving armed forces personnelreport as

suffering from PSTD.

However,art therapy is a treatment option that can

be used to address the full range of emotional,behav-

ioural and mentalhealth issues(BAAT,2019);the

statisticalevidence (DefStats (Health),2017)shows

that 90% ofthe MentalHealth conditions presenting

at DCMH are:mood disorders (33%),adjustment dis-

orders (32%) and non-PSTD related neurotic disorders

(25%),it is suggested thatart therapy research may

be focused in addressingone of the prevailing

conditions.

It is not the intent of this paper to discuss a specific

intervention orresearch method thatcould be used

within a DCMH as a proposalwould need discussion,

ethicalscrutiny and agreementwith key personnel

before work could begin.However,this paperis a

call to arms (pun intended)to pave the way to

employ an arttherapistto conductclinicalresearch

in this field.

Advice on funding for academic research is available

from the Research Council(Research Council,2017)

and it is normalfor the findings to be published in a

peer reviewed journal.The Academic Departmentof

MilitaryMental Health (ADMMH),based at King’s

College London (KCL), have undertaken numerous aca-

demic studies into the mentalhealth of Armed Forces

and Veteran personnel(Kings College London,2017).

ADMMH supported CombatStressin the studies

undertaken by the arttherapy departments used by

veterans.KCL has a good working relationship with

the MoD and both organisation’s ethics boards scruti-

nise requests for Armed Forces personnel participation

in research carried out by KCL academics and students

(Kings College London,2017).

Figure 1. Remember.Mixed media,R.Preston,2018.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY 5

there may be benefitin conducting an arttherapy

study to ascertain some of the stressors that arise for

women in comparison to men in the UK Armed Forces.

Potential research

It has been discussed in this paper that the MoD do not

employ art therapists nor do they use art therapy as a

treatmentintervention formentalhealth conditions.

It is inferred by the author that this is due to the NICE

guideline recommendation thattreatmentfor PTSD

should be CBT followed by EMDR.However,without

employing an arttherapistto conductresearch with

an armed forces personnelclient group,one is never

going to gather the evidence required to change the

recommended treatment.

Evidenceis being gathered bythe UK charity

Combat Stress and at NICoE in the US which suggests

that art therapy is a beneficialtreatment for UK veter-

ans and US military personnelexperiencing PTSD and

TBIs.As yet,art therapy as a treatment option has not

yet been introduced in any ofthe DCMH settings.

This could be explained due to the statistical evidence

gathered (Def Stats (Health), 2017) which suggests that

only 6% ofserving armed forces personnelreport as

suffering from PSTD.

However,art therapy is a treatment option that can

be used to address the full range of emotional,behav-

ioural and mentalhealth issues(BAAT,2019);the

statisticalevidence (DefStats (Health),2017)shows

that 90% ofthe MentalHealth conditions presenting

at DCMH are:mood disorders (33%),adjustment dis-

orders (32%) and non-PSTD related neurotic disorders

(25%),it is suggested thatart therapy research may

be focused in addressingone of the prevailing

conditions.

It is not the intent of this paper to discuss a specific

intervention orresearch method thatcould be used

within a DCMH as a proposalwould need discussion,

ethicalscrutiny and agreementwith key personnel

before work could begin.However,this paperis a

call to arms (pun intended)to pave the way to

employ an arttherapistto conductclinicalresearch

in this field.

Advice on funding for academic research is available

from the Research Council(Research Council,2017)

and it is normalfor the findings to be published in a

peer reviewed journal.The Academic Departmentof

MilitaryMental Health (ADMMH),based at King’s

College London (KCL), have undertaken numerous aca-

demic studies into the mentalhealth of Armed Forces

and Veteran personnel(Kings College London,2017).

ADMMH supported CombatStressin the studies

undertaken by the arttherapy departments used by

veterans.KCL has a good working relationship with

the MoD and both organisation’s ethics boards scruti-

nise requests for Armed Forces personnel participation

in research carried out by KCL academics and students

(Kings College London,2017).

Figure 1. Remember.Mixed media,R.Preston,2018.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY 5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The MoD has drawn extensively on the research

conducted by the ADMMH to draw up the recently

published Defence People MentalHealth and Well-

being Strategy 2017–2022 (MoD,2017).The strategy

recognises that society is changing and that the inci-

dence ofpeople experiencing poormentalhealth is

as prevalent in Defence (including military and civilian

workforce) as it is in the general population. The MoD’s

strategic aimsdemonstrate a top managementled

commitment to supporting mentalhealth for all.Art

therapy is not specifically mentioned but it could be

delivered under this strategy as an innovative interven-

tion eitheras a mentalhealth treatmentor in the

support of organisationalwellbeing.

In 2014,an All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts,

Health and Wellbeing was convened with an inquiry

report (APPG, 2017)published in July 2017.The

report highlights the benefits of the arts in maintaining

health and wellbeing.In this context the APPG were

considering the arts in generaland not specifically art

therapy.The APPG acknowledge thatthe UK is in a

time of austerity and that funding for the arts is in com-

petition with otherbids for financialsupport.The

reportsuggested that,with investmentin the right

research,there is likely to be demonstrable evidence

to support engagement in art,as individuals or as a

community,delivering a positive effect on health and

wellbeing which willin turn save costs in the future.

Among the recommendations it was suggested that

each NHS organisation takes responsibility ata stra-

tegic levelfor arts,health and wellbeing as an insti-

tutionalpolicy.Although notspecified the MoD and

DMS could be included in this list as clinicalcommis-

sioners if they saw merit in the delivery of art therapy

as a treatment option in DCMH.

Conclusion

Art therapy is an established therapeutic intervention

that is practised by postgraduate,HCPC state regis-

tered,professionals.They are trained to work with

clientsin a psychotherapeuticframeworkand are

able to provide support to people of allages who are

experiencingemotional,behaviouraland mental

health issues (BAAT,2019).

Personnelserving in the UK Armed Forces are as

likely to experience poor mentalhealth as the general

population although the difficultiesthat this group

encounterare different(Def Stats (Health),2017).

Mental health support in the UK Armed Forces provided

by DCMH is in accordance with NICE guidelines.The

MoD has a clear strategy (Ministry ofDefence,2017)

for Armed Forces mentalhealth and wellbeing with a

plan that looks to the future.However,there is no pro-

vision of art therapyfor Armed Forcespersonnel

(Lobban, 2016b). Combat Stress art therapy department

in consultationwith Kings College London has

produced research that evidences the benefits ofart

therapy with veterans who have PTSD (Lobban,2017).

There are a number of published research papers study-

ing military personnel who enrolled in art therapy pro-

grammesin the US and Russia supportingthe

hypothesis that art therapy improves the health and

wellbeing of those who are currently serving or,have

served in the military(Alexander,2015;Campbell

et al., 2016;Collie et al., 2006;Jones et al., 2017;

Kopytin & Lebedev,2015;Malchiodi,2016;Salmon &

Gerber,1999;Walkeret al.,2016,2017).A study in

Israelhypothesised thatstressors forwomen in the

IDF were notthe same astheir male counterparts

(Harel-Shalev etal.,2017).The APPG inquiry report

(2017)recommends that health authorities and com-

missioning groups consider their policies with regard

to supporting the arts in health and wellbeing activities

and investing in research to measure these benefits, this

could be taken to include the MoD.

There is very little research into the applicability of art

therapy for the serving Armed Forces population seeking

support at DCMH. It is therefore suggested that the use of

art therapy with UK Armed Forces personnel presenting

for treatment at DCMH is likely to produce a beneficial

outcome forthe health and wellbeing ofthis client

group.Outcomeswould need to be evidenced and

reported by research conducted by a qualified art thera-

pist working within DCMH. Appropriate research funding

would need to be made available and academic support

provided by an appropriate research institution.

Disclosure statement

No potentialconflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Rachel Preston graduated with an MA in Art Therapy from the

University ofDerby in 2018.Her studies explored her own

experience ofculturaltransition from being in the Armed

Forces to becoming an art therapist and a veteran (Figure

1). She spent25 years in the RoyalAir Force working in

support ofArmed Forces colleagues in diverse roles across

human resources, welfare support, training and development,

project management and, civilian housing and homelessness

support.Her experience ofworking with service personnel

and familiesin distressled her to believe her natural

empathy would be suited to providing therapeutic support.

As an arttherapist,Rachelhas worked with women in a

mental health in-patient service and she is currently providing

an art therapy service to schools in Lincolnshire.

References

Alexander,C.(2015).Behind the mask:Revealing the trauma

of war.NationalGeographic.Retrieved from http://www.

nationalgeographic.com/healing-soldiers/

Alford,B.,& Beck,A.(1997).The integrative power of cognitive

therapy.New York (NY):Guilford.

6 R.PRESTON

conducted by the ADMMH to draw up the recently

published Defence People MentalHealth and Well-

being Strategy 2017–2022 (MoD,2017).The strategy

recognises that society is changing and that the inci-

dence ofpeople experiencing poormentalhealth is

as prevalent in Defence (including military and civilian

workforce) as it is in the general population. The MoD’s

strategic aimsdemonstrate a top managementled

commitment to supporting mentalhealth for all.Art

therapy is not specifically mentioned but it could be

delivered under this strategy as an innovative interven-

tion eitheras a mentalhealth treatmentor in the

support of organisationalwellbeing.

In 2014,an All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts,

Health and Wellbeing was convened with an inquiry

report (APPG, 2017)published in July 2017.The

report highlights the benefits of the arts in maintaining

health and wellbeing.In this context the APPG were

considering the arts in generaland not specifically art

therapy.The APPG acknowledge thatthe UK is in a

time of austerity and that funding for the arts is in com-

petition with otherbids for financialsupport.The

reportsuggested that,with investmentin the right

research,there is likely to be demonstrable evidence

to support engagement in art,as individuals or as a

community,delivering a positive effect on health and

wellbeing which willin turn save costs in the future.

Among the recommendations it was suggested that

each NHS organisation takes responsibility ata stra-

tegic levelfor arts,health and wellbeing as an insti-

tutionalpolicy.Although notspecified the MoD and

DMS could be included in this list as clinicalcommis-

sioners if they saw merit in the delivery of art therapy

as a treatment option in DCMH.

Conclusion

Art therapy is an established therapeutic intervention

that is practised by postgraduate,HCPC state regis-

tered,professionals.They are trained to work with

clientsin a psychotherapeuticframeworkand are

able to provide support to people of allages who are

experiencingemotional,behaviouraland mental

health issues (BAAT,2019).

Personnelserving in the UK Armed Forces are as

likely to experience poor mentalhealth as the general

population although the difficultiesthat this group

encounterare different(Def Stats (Health),2017).

Mental health support in the UK Armed Forces provided

by DCMH is in accordance with NICE guidelines.The

MoD has a clear strategy (Ministry ofDefence,2017)

for Armed Forces mentalhealth and wellbeing with a

plan that looks to the future.However,there is no pro-

vision of art therapyfor Armed Forcespersonnel

(Lobban, 2016b). Combat Stress art therapy department

in consultationwith Kings College London has

produced research that evidences the benefits ofart

therapy with veterans who have PTSD (Lobban,2017).

There are a number of published research papers study-

ing military personnel who enrolled in art therapy pro-

grammesin the US and Russia supportingthe

hypothesis that art therapy improves the health and

wellbeing of those who are currently serving or,have

served in the military(Alexander,2015;Campbell

et al., 2016;Collie et al., 2006;Jones et al., 2017;

Kopytin & Lebedev,2015;Malchiodi,2016;Salmon &

Gerber,1999;Walkeret al.,2016,2017).A study in

Israelhypothesised thatstressors forwomen in the

IDF were notthe same astheir male counterparts

(Harel-Shalev etal.,2017).The APPG inquiry report

(2017)recommends that health authorities and com-

missioning groups consider their policies with regard

to supporting the arts in health and wellbeing activities

and investing in research to measure these benefits, this

could be taken to include the MoD.

There is very little research into the applicability of art

therapy for the serving Armed Forces population seeking

support at DCMH. It is therefore suggested that the use of

art therapy with UK Armed Forces personnel presenting

for treatment at DCMH is likely to produce a beneficial

outcome forthe health and wellbeing ofthis client

group.Outcomeswould need to be evidenced and

reported by research conducted by a qualified art thera-

pist working within DCMH. Appropriate research funding

would need to be made available and academic support

provided by an appropriate research institution.

Disclosure statement

No potentialconflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Rachel Preston graduated with an MA in Art Therapy from the

University ofDerby in 2018.Her studies explored her own

experience ofculturaltransition from being in the Armed

Forces to becoming an art therapist and a veteran (Figure

1). She spent25 years in the RoyalAir Force working in

support ofArmed Forces colleagues in diverse roles across

human resources, welfare support, training and development,

project management and, civilian housing and homelessness

support.Her experience ofworking with service personnel

and familiesin distressled her to believe her natural

empathy would be suited to providing therapeutic support.

As an arttherapist,Rachelhas worked with women in a

mental health in-patient service and she is currently providing

an art therapy service to schools in Lincolnshire.

References

Alexander,C.(2015).Behind the mask:Revealing the trauma

of war.NationalGeographic.Retrieved from http://www.

nationalgeographic.com/healing-soldiers/

Alford,B.,& Beck,A.(1997).The integrative power of cognitive

therapy.New York (NY):Guilford.

6 R.PRESTON

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts,Health and Wellbeing.

(2017). Inquiry report, creative health: The arts for health and

wellbeing (2nd ed.).APPG:Retrieved from http://www.

artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

Ashcroft,M. (2014).The veterans’transition review.Retrieved

from http://www.veteranstransition.co.uk/vtrreport.pdf

British Association of Art Therapists. (2019). British Association

of Art Therapists Website. Retrieved from http://www.baat.

org

Busuttil, W. (2017). Military culture effects on mental health and

help-seeking. In J. Lobban (Ed.), Art therapy with military veter-

ans: Trauma and the image (pp. 73–88).London:Routledge.

Campbell,M., Decker,K., Kruk,K.,& Deaver,S. (2016).Art

therapy and cognitive processing therapy forcombat-

related PTSD:A randomized controlled trial.Art Therapy,

33(4),169–177.

COBSEO.(2017).Confederation ofservice charities.Retrieved

from https://www.cobseo.org.uk/members/directory/

Collie,C.A.,Backos,A.,Malchiodi,C.,& Spiegel,D.(2006).Art

therapy forcombat-related PTSD:Recommendations for

research and practice.Art Therapy,23(4),157–164.

Combat Stress.(2019).Combat stress – for veterans’mental

health.Retrieved from https://www.combatstress.org.uk/

Defence MedicalService.(2017).Defencemedicalservice.

Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/

defence-medical-services

Defence Statistics (Health).(2017).UK Armed Forces mental

health:Annualsummary & trends overtime,2007/08–

2016/17.Ministryof Defence:Retrieved from https://

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/619133/20170615_Mental_Health_

Annual_Report_16-17_O_R.pdf

Edwards,D.(2014).Art therapy (2nd ed.).London:Sage.

England,J., Martin,T.,& Rosamond,S. (2017).Art in action:

The combatart project.In J. Lobban (Ed.),Art therapy

with military veterans:Trauma and the image (pp.202–

214).London:Routledge.

Greenberg,N.,Langston,V.,& Jones,N. (2008).Trauma risk

management (TRiM)in the UK Armed Forces.Journalof

the RoyalArmy MedicalCorps,154,124–127.

Hacker Hughes, J. (2017). Mental health treatment for serving

UK military personnel.In J. Lobban (Ed.),Art therapy with

militaryveterans:Trauma and theimage(pp. 63–72).

London:Routledge.

Harel-Shalev,A., Huss,E., Daphna-Tekoah,S., & Cwikel,J.

(2017).Drawing (on)women’s military experiences and

narratives – Israeliwomen soldiers’challenges in the mili-

tary environment.Gender,Place &Culture,24(4),499–514.

Help for Heroes. (2017). Help for heroes recovery programme.

Retrieved from https://www.helpforheroes.org.uk/get-

support/recovery-programme/

Hogan,S. (2016).Art therapy theories:A criticalintroduction.

London:Routledge.

Howie,P. (Ed.).(2017).Art therapy with military populations:

History, innovation and application. New York (NY): Routledge.

Jones,N., Burdett,H., Green,K., & Greenberg,N. (2017).

Trauma risk management (TRiM):Promoting help seeking

for mentalhealth problems among combat exposed U.K.

military personnel.Psychiatry,80(3),236–251.

Jones,N.,Campion,B.,Keeling,M.,& Greenberg,N. (2018).

Cohesion,leadership,mentalhealth stigmatisation and

perceived barriersto care in UK militarypersonnel.

Journalof MentalHealth,27(1),10–18.

Kings College London. (2017). KCMHR and ADMMH Publications.

Retrieved from https://www1.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/pubdb/

Kopytin,A., & Lebedev,A. (2015).Therapeutic functions of

humour in group art therapy with war veterans.

InternationalJournalof Art Therapy,20(2),40–53.

Lobban,J. (2014).The invisible wound:Veterans’art therapy.

InternationalJournalof Art Therapy,19(1),3–18.

Lobban,J. (2016a).Factors that influence engagement in an

inpatientart therapy group forveterans with posttrau-

matic stress disorder.InternationalJournalof Art Therapy,

21(1),15–22.

Lobban, J. (2016b). Art therapy for military veterans with PTSD:

A transatlantic study.Winston ChurchillMemorialTrust.

Retrieved from http://www.wcmt.org.uk/sites/default/

files/report-documents/Lobban%20J%20Report%

202016%20Final.pdf

Lobban,J. (2017).Art therapy with military veterans:Trauma

and the image.London:Routledge.

Lobban,J., & Murphy,D. (2018).Using art therapy to over-

come avoidance in veterans with chronic post-traumatic

stress disorder.InternationalJournalof Art Therapy,23(3),

99–114.

Malchiodi,C. (2016).Art therapy:Treating combat-related

PTSD.Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/

blog/arts-and-health/201610/art-therapy-treating-combat-

related-ptsd

McArdle,L. (Director).(2011).Art for heroes:A culture show

special [Televisionseries episode]. In L. McArdle

(Producer),The Culture Show.London:BBC.

Ministry of Defence. (2017). Defence people mental health and

wellbeing strategy 2017-2022.Retrieved from https://www.

gov.uk/government/publications/defence-people-mental-

health-and-wellbeing-strategy

NHS Choices.(2015).Defence recovery capability.Retrieved

from https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/Militaryhealthcare/

transition/Pages/defence-recovery.aspx

NHS Digital.(2017).Mentalhealth services data set.Retrieved

from http://content.digital.nhs.uk/mhsds

NICE. (2015).Post-traumaticstressdisorder:Management.

Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg26

Palmer,E.,Hill,K.,Lobban,J., & Murphy,D. (2017).Veterans’

perspectives on the acceptability of art therapy:A mixed-

methods study.InternationalJournalof Art Therapy,22(3),

132–137.

ResearchCouncil.(2017).Eligibilityfor ResearchCouncil

funding.Retrieved from http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/funding/

eligibilityforrcs/

Salmon, P., & Gerber, N. (1999). Disappointment,

dependency and depression in the military:The role of

expectations as reflected in drawings.Art Therapy,16

(1),17–30.

Shapiro,F.,& Forrester,M. (1998).EMDR:The breakthrough

‘eye movement’therapy for overcoming anxiety,stress and

trauma.New York (NY):Sage.

Silver,R. (2002).Threeart assessments.New York (NY):

Brunner-Routledge.

Van derKolk,B. (2014).The body keeps the score.London:

Penguin Books.

Walker,M., Kaimal,G., Gonzaga,A., Myers-Coffman,K., &

DeGraba,T. (2017).Active-duty military service members’

visual representationsof PTSD and TBI in masks.

InternationalJournalof Qualitative Studies on Health and

Well-Being,12(1),1267317.

Walker,M.,Kaimal,G.,Koffman,R.,& DeGraba,T.(2016).Art

therapy forPTSD and TBI:A senioractive duty military

service member’stherapeuticjourney. The Arts in

Psychotherapy,49,10–18.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART THERAPY 7

(2017). Inquiry report, creative health: The arts for health and

wellbeing (2nd ed.).APPG:Retrieved from http://www.

artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

Ashcroft,M. (2014).The veterans’transition review.Retrieved

from http://www.veteranstransition.co.uk/vtrreport.pdf

British Association of Art Therapists. (2019). British Association

of Art Therapists Website. Retrieved from http://www.baat.

org

Busuttil, W. (2017). Military culture effects on mental health and

help-seeking. In J. Lobban (Ed.), Art therapy with military veter-

ans: Trauma and the image (pp. 73–88).London:Routledge.

Campbell,M., Decker,K., Kruk,K.,& Deaver,S. (2016).Art

therapy and cognitive processing therapy forcombat-

related PTSD:A randomized controlled trial.Art Therapy,

33(4),169–177.

COBSEO.(2017).Confederation ofservice charities.Retrieved

from https://www.cobseo.org.uk/members/directory/

Collie,C.A.,Backos,A.,Malchiodi,C.,& Spiegel,D.(2006).Art

therapy forcombat-related PTSD:Recommendations for

research and practice.Art Therapy,23(4),157–164.

Combat Stress.(2019).Combat stress – for veterans’mental

health.Retrieved from https://www.combatstress.org.uk/

Defence MedicalService.(2017).Defencemedicalservice.

Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/

defence-medical-services

Defence Statistics (Health).(2017).UK Armed Forces mental

health:Annualsummary & trends overtime,2007/08–

2016/17.Ministryof Defence:Retrieved from https://

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/619133/20170615_Mental_Health_

Annual_Report_16-17_O_R.pdf

Edwards,D.(2014).Art therapy (2nd ed.).London:Sage.

England,J., Martin,T.,& Rosamond,S. (2017).Art in action:

The combatart project.In J. Lobban (Ed.),Art therapy

with military veterans:Trauma and the image (pp.202–

214).London:Routledge.

Greenberg,N.,Langston,V.,& Jones,N. (2008).Trauma risk

management (TRiM)in the UK Armed Forces.Journalof

the RoyalArmy MedicalCorps,154,124–127.

Hacker Hughes, J. (2017). Mental health treatment for serving

UK military personnel.In J. Lobban (Ed.),Art therapy with

militaryveterans:Trauma and theimage(pp. 63–72).

London:Routledge.

Harel-Shalev,A., Huss,E., Daphna-Tekoah,S., & Cwikel,J.

(2017).Drawing (on)women’s military experiences and

narratives – Israeliwomen soldiers’challenges in the mili-

tary environment.Gender,Place &Culture,24(4),499–514.

Help for Heroes. (2017). Help for heroes recovery programme.

Retrieved from https://www.helpforheroes.org.uk/get-

support/recovery-programme/

Hogan,S. (2016).Art therapy theories:A criticalintroduction.

London:Routledge.

Howie,P. (Ed.).(2017).Art therapy with military populations:

History, innovation and application. New York (NY): Routledge.

Jones,N., Burdett,H., Green,K., & Greenberg,N. (2017).

Trauma risk management (TRiM):Promoting help seeking

for mentalhealth problems among combat exposed U.K.

military personnel.Psychiatry,80(3),236–251.

Jones,N.,Campion,B.,Keeling,M.,& Greenberg,N. (2018).

Cohesion,leadership,mentalhealth stigmatisation and

perceived barriersto care in UK militarypersonnel.

Journalof MentalHealth,27(1),10–18.

Kings College London. (2017). KCMHR and ADMMH Publications.

Retrieved from https://www1.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/pubdb/

Kopytin,A., & Lebedev,A. (2015).Therapeutic functions of