Australian Alcohol Consumption and Health Promotion Strategies Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/07

|11

|2945

|436

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an overview of alcohol consumption in Australia, highlighting it as a major public health concern due to the associated harms and misuse. It examines various interventions implemented to reduce alcohol consumption, including both individual-level strategies like educational programs and population-level approaches such as taxation and advertising regulations. The report contrasts individual change interventions, which target at-risk individuals, with population-level interventions that aim to affect the entire community. It discusses the effectiveness of different strategies, such as brief interventions, mass media campaigns, and regulations on alcohol availability, while also acknowledging the political and social challenges in implementing these interventions. The report concludes by emphasizing effective interventions that address the wellbeing and welfare sector and have a positive influence on several health domains.

HEALTH PROMOTION 1

Health Promotion

Student’s Name

Institutional Affiliation

Professor’s Name

City

Date

Health Promotion

Student’s Name

Institutional Affiliation

Professor’s Name

City

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

HEALTH PROMOTION 2

Executive summary

This report covers alcohol consumption in Australia and the strategies enforced to reduce

its use and the related damages. The high consumption of alcohol misuse, along with the harms

affiliated with alcohol are major policy and public health concerns in Australia. The consumption

patterns of alcohol impact the nature and extent of the harms related to alcohol (Roche et al.,

2015, p. ii20). Frequent lower consumption may lead to alcohol-affiliated disorders like brain

damage, cardiovascular disorder as well as liver cirrhosis. On the other hand, infrequent higher

consumption may result in harms stemming from intoxication-affiliated injuries and assaults.

Interventions implemented to change the behavior of an individual are depended chiefly upon

educational programs, primarily in the form of mass media policies or community-based skills

training for teenagers.

Alcohol Misuse

Health promotion is an essential element of public health practice. It is a process of

helping individuals increase control over the health factors hence improving their wellbeing

(McPhail-Bell, Bond, Brough and Fredericks, 2016, p.195). Alcohol misuse is defined as the

consumption of alcohol which puts people at an escalated peril of adverse health outcomes as

well as social problems. Moreover, it is described as excess daily consumption of more than four

bottles daily for men or more than 3 bottles for women. Misuse of alcohol is a significant issue

both economically and socially to the Australian people (Jiang and Room 2018, p.1157).

At the individual level, higher socioeconomic status seems to be affiliated with more

constant consumption whilst lower socioeconomic status relates to the use of higher quantities

per occasion (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii22). Nonetheless, this connection is dependent on the

socioeconomic status measures utilized like education, neighborhood deprivation, income, and

Executive summary

This report covers alcohol consumption in Australia and the strategies enforced to reduce

its use and the related damages. The high consumption of alcohol misuse, along with the harms

affiliated with alcohol are major policy and public health concerns in Australia. The consumption

patterns of alcohol impact the nature and extent of the harms related to alcohol (Roche et al.,

2015, p. ii20). Frequent lower consumption may lead to alcohol-affiliated disorders like brain

damage, cardiovascular disorder as well as liver cirrhosis. On the other hand, infrequent higher

consumption may result in harms stemming from intoxication-affiliated injuries and assaults.

Interventions implemented to change the behavior of an individual are depended chiefly upon

educational programs, primarily in the form of mass media policies or community-based skills

training for teenagers.

Alcohol Misuse

Health promotion is an essential element of public health practice. It is a process of

helping individuals increase control over the health factors hence improving their wellbeing

(McPhail-Bell, Bond, Brough and Fredericks, 2016, p.195). Alcohol misuse is defined as the

consumption of alcohol which puts people at an escalated peril of adverse health outcomes as

well as social problems. Moreover, it is described as excess daily consumption of more than four

bottles daily for men or more than 3 bottles for women. Misuse of alcohol is a significant issue

both economically and socially to the Australian people (Jiang and Room 2018, p.1157).

At the individual level, higher socioeconomic status seems to be affiliated with more

constant consumption whilst lower socioeconomic status relates to the use of higher quantities

per occasion (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii22). Nonetheless, this connection is dependent on the

socioeconomic status measures utilized like education, neighborhood deprivation, income, and

HEALTH PROMOTION 3

occupation. On the other hand, at a population level, there exists an immediate interrelationship

amidst per-capita acquisition power and use of alcohol. Here, percentages of abstainers reduce as

per-capita income elevates. Nevertheless, this connection weakens when the per-capita alcohol

affordability threshold is attained (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii22).

Comparison between individual change interventions and interventions at a population

level

Both at a population level and individual level, pricing and taxation is an intervention that

has reduced the drinking of alcohol. Escalated taxation to increase the prices of alcohol may

decline its use and affiliated dangers at the population level (Wilson, Graham, and Taft, 2014, p.

881). Nonetheless, a comparatively brief investigation has regarded price effects from an

impartiality aspect and available research is uncertain. Inexpensive alcohol may contain

specifically adverse ramifications for underprivileged persons. As low socioeconomic persons,

young individuals along with perilous alcoholics are most probable to decline their use in

reaction to elevated costs (Jiang et al., 2019, p. e029918). Nonetheless, risky drinkers who keep

alcohol consumption despite the high costs might encounter escalated disadvantages like

spending limited cash on alcohol instead of housing (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii23).

Education along with persuasion interventions at the individual level and advertising at

the population level has a similarity in how they reduce the consumption of alcohol and its

related problems. Education and persuasion are among the most famous strategy for the

prevention of alcohol-affiliated harms and have multiple objectives. The aims of education and

persuasion are attempting to reduce the peril by altering consumption behaviors, attempting to

escalate the reinforcement for alcohol control strategies, along with elevating the knowledge of

drinking-affiliated perils.

occupation. On the other hand, at a population level, there exists an immediate interrelationship

amidst per-capita acquisition power and use of alcohol. Here, percentages of abstainers reduce as

per-capita income elevates. Nevertheless, this connection weakens when the per-capita alcohol

affordability threshold is attained (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii22).

Comparison between individual change interventions and interventions at a population

level

Both at a population level and individual level, pricing and taxation is an intervention that

has reduced the drinking of alcohol. Escalated taxation to increase the prices of alcohol may

decline its use and affiliated dangers at the population level (Wilson, Graham, and Taft, 2014, p.

881). Nonetheless, a comparatively brief investigation has regarded price effects from an

impartiality aspect and available research is uncertain. Inexpensive alcohol may contain

specifically adverse ramifications for underprivileged persons. As low socioeconomic persons,

young individuals along with perilous alcoholics are most probable to decline their use in

reaction to elevated costs (Jiang et al., 2019, p. e029918). Nonetheless, risky drinkers who keep

alcohol consumption despite the high costs might encounter escalated disadvantages like

spending limited cash on alcohol instead of housing (Roche et al., 2015, p. ii23).

Education along with persuasion interventions at the individual level and advertising at

the population level has a similarity in how they reduce the consumption of alcohol and its

related problems. Education and persuasion are among the most famous strategy for the

prevention of alcohol-affiliated harms and have multiple objectives. The aims of education and

persuasion are attempting to reduce the peril by altering consumption behaviors, attempting to

escalate the reinforcement for alcohol control strategies, along with elevating the knowledge of

drinking-affiliated perils.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

HEALTH PROMOTION 4

Advertising and other forms of promotion have escalated recently. Self-regulation of

alcohol advertising as well as marketing has been demonstrated to be insubstantial and highly

incompetent. However, assessments of the impacts of regulations on alcohol advertising do not

demonstrate evident declines in alcohol use and affiliated injuries. Over the years, the addition of

warning labels on alcohol packaging has been a significant public discourse in Australia

(Howard, Gordon and Jones 2014, p. 848). The labels feature a pictogram showing that pregnant

women should not use alcohol or statements like “kids and alcohol do not mix” thus changing

the behaviors of individuals.

Moreover, the intervention of education and persuasion along with advertising has also

been featured in large-scale mass media campaigns to emphasize the adverse aspects of

dangerous drinking habits. Whilst these campaigns mainly target the decline of the most

common perilous behaviors in present alcoholics, the government of Australia has targeted at

avoidance in future alcoholics via classroom learning (Howard et al., 2014, p. 848).

The contrast between individual change interventions and interventions at a population

level

Individual behavior change interventions also are known as indicated interventions are

types of interventions to assist a person with a certain health condition or behavior that may

impact his or her wellbeing (Morrison and Cameron 2015, p.1183). They target individuals

identified as being at escalated peril of harm due to alcohol and substance abuse. On the other

hand, interventions at a population level also known as universal intervention are utilized to

minimize certain health issues. A health issue like alcohol misuse is minimized over all

individuals in a specific population by minimizing a broad range of risk determinants and

Advertising and other forms of promotion have escalated recently. Self-regulation of

alcohol advertising as well as marketing has been demonstrated to be insubstantial and highly

incompetent. However, assessments of the impacts of regulations on alcohol advertising do not

demonstrate evident declines in alcohol use and affiliated injuries. Over the years, the addition of

warning labels on alcohol packaging has been a significant public discourse in Australia

(Howard, Gordon and Jones 2014, p. 848). The labels feature a pictogram showing that pregnant

women should not use alcohol or statements like “kids and alcohol do not mix” thus changing

the behaviors of individuals.

Moreover, the intervention of education and persuasion along with advertising has also

been featured in large-scale mass media campaigns to emphasize the adverse aspects of

dangerous drinking habits. Whilst these campaigns mainly target the decline of the most

common perilous behaviors in present alcoholics, the government of Australia has targeted at

avoidance in future alcoholics via classroom learning (Howard et al., 2014, p. 848).

The contrast between individual change interventions and interventions at a population

level

Individual behavior change interventions also are known as indicated interventions are

types of interventions to assist a person with a certain health condition or behavior that may

impact his or her wellbeing (Morrison and Cameron 2015, p.1183). They target individuals

identified as being at escalated peril of harm due to alcohol and substance abuse. On the other

hand, interventions at a population level also known as universal intervention are utilized to

minimize certain health issues. A health issue like alcohol misuse is minimized over all

individuals in a specific population by minimizing a broad range of risk determinants and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

HEALTH PROMOTION 5

fostering a wide range of protective factors (Greenberg and Abenavoli 2017, p.40). These

interventions apply to the whole population with no attempt to differentiate people based on their

risk for developing issues.

In individual change behavior, screening intervention accurately categorizes users into

low, moderate and high-risk categories. Regardless of the screening approach applied, those

deemed at risk of harm are normally provided a brief intervention or referred to therapy (Tanner-

Smith and Lipsey 2015, p.3). In contrast, at a population level, drink driving countermeasures

categorizes users of alcohol and policies preventing driving under the influence of alcohol are

established in Australian law (Wilson, Stoyanov, Gandabhai and Baldwin 2016, p.e98).

For example, all Australian states and territories mandate drivers to have their blood

alcohol content (BAC) below 0.05 and a threshold of BAC leads to immediate license

suspension. Moreover, there is a huge level of variability in certain fines for drink driving

violations over Australia. This contrasts with the screening intervention as screening provides

brief intervention or refers to therapy but in drink driving, a test of at-risk consumption leads to

penalty and license suspension.

At an individual level, the alcohol treatment and early strategy is advantageous and

recommends substantial gains in wellbeing since the capability for a GP to share therapy with a

specialist alcohol and drug service is a principally compelling model. This intervention is cost-

saving and legislators recognize the need for therapy and early intervention for problem

alcoholics (Stockings et al., 2016, p.280). The successful interventions under the early

intervention include self-help strategies, screening and brief advice, pharmacological therapy to

prevent relapse in alcohol-dependent individuals and cognitive behavior therapy.

fostering a wide range of protective factors (Greenberg and Abenavoli 2017, p.40). These

interventions apply to the whole population with no attempt to differentiate people based on their

risk for developing issues.

In individual change behavior, screening intervention accurately categorizes users into

low, moderate and high-risk categories. Regardless of the screening approach applied, those

deemed at risk of harm are normally provided a brief intervention or referred to therapy (Tanner-

Smith and Lipsey 2015, p.3). In contrast, at a population level, drink driving countermeasures

categorizes users of alcohol and policies preventing driving under the influence of alcohol are

established in Australian law (Wilson, Stoyanov, Gandabhai and Baldwin 2016, p.e98).

For example, all Australian states and territories mandate drivers to have their blood

alcohol content (BAC) below 0.05 and a threshold of BAC leads to immediate license

suspension. Moreover, there is a huge level of variability in certain fines for drink driving

violations over Australia. This contrasts with the screening intervention as screening provides

brief intervention or refers to therapy but in drink driving, a test of at-risk consumption leads to

penalty and license suspension.

At an individual level, the alcohol treatment and early strategy is advantageous and

recommends substantial gains in wellbeing since the capability for a GP to share therapy with a

specialist alcohol and drug service is a principally compelling model. This intervention is cost-

saving and legislators recognize the need for therapy and early intervention for problem

alcoholics (Stockings et al., 2016, p.280). The successful interventions under the early

intervention include self-help strategies, screening and brief advice, pharmacological therapy to

prevent relapse in alcohol-dependent individuals and cognitive behavior therapy.

HEALTH PROMOTION 6

In contrast, at a population level, regulating the availability along with the accessibility of

alcohol is often not enforced since the intervention is objected politically in many campaigns. Its

consumption tends to elevate with greater physical availability and research exhibits that alcohol-

affiliated issues can be reduced by restricting availability by minimizing hours of sale as well as

decreasing the outlet density of alcohol. Members of the general community and many drinkers

obstruct these regulations and therefore legislators do not recognize the need for the intervention.

However, the government of New South Wales currently initiated legislation to minimize trading

hours for licensed venues as well as bottle shops in the Sydney central business district (Pennay,

Lubman and Frei 2014, p. 356).

Effective interventions

Effective interventions intent to decline the dangerous utilization of alcohol, and

consequently address the wellbeing as well as the welfare sector as its initial audience.

Moreover, these effective interventions have a positive influence on several health domains.

They lead to better mental health, improve adolescent, child, and reproductive health, lessens the

burden of non-communicable infections and decrease violence and injuries (Newton et al., 2016,

p.1056). A successful intervention constitutes a practical example of health promotion.

At the individual level, brief interventions were effective because they minimize alcohol

consumption in primary care and even in other environments (Linke and Murray 2017). They are

successful with both older and younger patients and with both men and women. They entail

personal follow-up which is more effective than a single contact strategy. Moreover, Mass

media campaigns, as well as education and persuasion interventions, were found to be effective

since they produce constant knowledge that may lay the basis for declines in alcohol drinking

(Young et al., 2018, p.303). Education, as well as persuasion, aims at elevating the understanding

In contrast, at a population level, regulating the availability along with the accessibility of

alcohol is often not enforced since the intervention is objected politically in many campaigns. Its

consumption tends to elevate with greater physical availability and research exhibits that alcohol-

affiliated issues can be reduced by restricting availability by minimizing hours of sale as well as

decreasing the outlet density of alcohol. Members of the general community and many drinkers

obstruct these regulations and therefore legislators do not recognize the need for the intervention.

However, the government of New South Wales currently initiated legislation to minimize trading

hours for licensed venues as well as bottle shops in the Sydney central business district (Pennay,

Lubman and Frei 2014, p. 356).

Effective interventions

Effective interventions intent to decline the dangerous utilization of alcohol, and

consequently address the wellbeing as well as the welfare sector as its initial audience.

Moreover, these effective interventions have a positive influence on several health domains.

They lead to better mental health, improve adolescent, child, and reproductive health, lessens the

burden of non-communicable infections and decrease violence and injuries (Newton et al., 2016,

p.1056). A successful intervention constitutes a practical example of health promotion.

At the individual level, brief interventions were effective because they minimize alcohol

consumption in primary care and even in other environments (Linke and Murray 2017). They are

successful with both older and younger patients and with both men and women. They entail

personal follow-up which is more effective than a single contact strategy. Moreover, Mass

media campaigns, as well as education and persuasion interventions, were found to be effective

since they produce constant knowledge that may lay the basis for declines in alcohol drinking

(Young et al., 2018, p.303). Education, as well as persuasion, aims at elevating the understanding

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

HEALTH PROMOTION 7

of the dangers associated with alcohol along with changing attitudes and drinking habits. In

education, details regarding alcohol are provided to persons who can then select for themselves

whether or not to consume alcohol and to what magnitude (Janssen, Mathijssen, van Bon–

Martens, Van Oers and Garretsen 2013, p.18).

At a population level, strategies that were effective entail increasing the minimum

drinking age and alcohol advertising (Berey, Loparco, Leeman and Grube 2017, p.173). This is

because they minimize the consumption of alcohol as well as minimizing affiliated dangers and

are focused on limiting its accessibility along with availability (Wakefield al., 2017, p.e014193).

As for minimizing the drinking age, it will decline the consumption amongst teenagers since it

will be difficult to buy alcohol. Moreover, teenagers are the most probable group to misuse

alcohol like drinking excess which results in accidents, deaths and health issues. If these youths

start to use alcohol later in life, they may be more probable to consume in restraint and not

become addicts at an early age (Plunk et al., 2016, p.1761).

of the dangers associated with alcohol along with changing attitudes and drinking habits. In

education, details regarding alcohol are provided to persons who can then select for themselves

whether or not to consume alcohol and to what magnitude (Janssen, Mathijssen, van Bon–

Martens, Van Oers and Garretsen 2013, p.18).

At a population level, strategies that were effective entail increasing the minimum

drinking age and alcohol advertising (Berey, Loparco, Leeman and Grube 2017, p.173). This is

because they minimize the consumption of alcohol as well as minimizing affiliated dangers and

are focused on limiting its accessibility along with availability (Wakefield al., 2017, p.e014193).

As for minimizing the drinking age, it will decline the consumption amongst teenagers since it

will be difficult to buy alcohol. Moreover, teenagers are the most probable group to misuse

alcohol like drinking excess which results in accidents, deaths and health issues. If these youths

start to use alcohol later in life, they may be more probable to consume in restraint and not

become addicts at an early age (Plunk et al., 2016, p.1761).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

HEALTH PROMOTION 8

References

Berey, B.L., Loparco, C., Leeman, R.F. and Grube, J.W., 2017. The myriad influences of alcohol

advertising on adolescent drinking. Current addiction reports, 4(2), pp.172-183.

Greenberg, M.T. and Abenavoli, R., 2017. Universal interventions: Fully exploring their impacts

and potential to produce population-level impacts. Journal of Research on Educational

Effectiveness, 10(1), pp.40-67.

Howard, S.J., Gordon, R. and Jones, S.C., 2014. Australian alcohol policy 2001–2013 and

implications for public health. BMC Public Health, 14(1), p.848.

Janssen, M.M., Mathijssen, J.J., van Bon–Martens, M.J., Van Oers, H.A. and Garretsen, H.F.,

2013. Effectiveness of alcohol prevention interventions based on the principles of social

marketing: a systematic review. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 8(1), p.18.

Jiang, H. and Room, R., 2018. Action on minimum unit pricing of alcohol: a broader need. The

Lancet, 391(10126), p.1157.

Jiang, H., Room, R., Livingston, M., Callinan, S., Brennan, A., Doran, C. and Thorn, M., 2019.

The effects of alcohol pricing policies on consumption, health, social and economic outcomes,

and health inequality in Australia: a protocol of an epidemiological modeling study. BMJ

Open, 9(6), p.e029918.

Kelly, S., Olanrewaju, O., Cowan, A., Brayne, C. and Lafortune, L., 2017. Interventions to prevent and

reduce excessive alcohol consumption in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and

aging, 47(2), pp.175-184.

Linke, S. and Murray, E., 2017. Internet-Based Methods in Managing Alcohol Misuse. In Oxford

Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.

References

Berey, B.L., Loparco, C., Leeman, R.F. and Grube, J.W., 2017. The myriad influences of alcohol

advertising on adolescent drinking. Current addiction reports, 4(2), pp.172-183.

Greenberg, M.T. and Abenavoli, R., 2017. Universal interventions: Fully exploring their impacts

and potential to produce population-level impacts. Journal of Research on Educational

Effectiveness, 10(1), pp.40-67.

Howard, S.J., Gordon, R. and Jones, S.C., 2014. Australian alcohol policy 2001–2013 and

implications for public health. BMC Public Health, 14(1), p.848.

Janssen, M.M., Mathijssen, J.J., van Bon–Martens, M.J., Van Oers, H.A. and Garretsen, H.F.,

2013. Effectiveness of alcohol prevention interventions based on the principles of social

marketing: a systematic review. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 8(1), p.18.

Jiang, H. and Room, R., 2018. Action on minimum unit pricing of alcohol: a broader need. The

Lancet, 391(10126), p.1157.

Jiang, H., Room, R., Livingston, M., Callinan, S., Brennan, A., Doran, C. and Thorn, M., 2019.

The effects of alcohol pricing policies on consumption, health, social and economic outcomes,

and health inequality in Australia: a protocol of an epidemiological modeling study. BMJ

Open, 9(6), p.e029918.

Kelly, S., Olanrewaju, O., Cowan, A., Brayne, C. and Lafortune, L., 2017. Interventions to prevent and

reduce excessive alcohol consumption in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and

aging, 47(2), pp.175-184.

Linke, S. and Murray, E., 2017. Internet-Based Methods in Managing Alcohol Misuse. In Oxford

Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.

HEALTH PROMOTION 9

McPhail-Bell, K., Bond, C., Brough, M. and Fredericks, B., 2016. ‘We don’t tell people what to

do’: ethical practice and Indigenous health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of

Australia, 26(3), pp.195-199.

Morrison, C. and Cameron, P., 2015. The case for environmental strategies to prevent alcohol-

related trauma. Injury, 46(7), pp.1183-1185.

Newton, N.C., Conrod, P.J., Slade, T., Carragher, N., Champion, K.E., Barrett, E.L., Kelly, E.V.,

Nair, N.K., Stapinski, L. and Teesson, M., 2016. The long‐term effectiveness of a selective,

personality‐targeted prevention program in reducing alcohol use and related harms: A cluster

randomized controlled trial. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 57(9), pp.1056-1065.

Pennay, A., Lubman, D.I., and Frei, M., 2014. Alcohol: prevention, policy and primary care

responses. Australian family physician, 43(6), p.356.

Plunk, A.D., Krauss, M.J., Syed‐Mohammed, H., Hur, M., Cavzos‐Rehg, P.A., Bierut, L.J. and

Grucza, R.A., 2016. The impact of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol‐related chronic

disease mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research, 40(8), pp.1761-1768.

Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Fischer, J., Nicholas, R., O'Rourke, K., Pidd, K., & Trifonoff, A.

(2015). Addressing inequities in alcohol consumption and related harms. Health promotion

international, 30(suppl_2), ii20-ii35.

Stockings, E., Hall, W.D., Lynskey, M., Morley, K.I., Reavley, N., Strang, J., Patton, G. and

Degenhardt, L., 2016. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance

use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.280-296.

Tanner-Smith, E.E., and Lipsey, M.W., 2015. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and

young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 51,

pp.1-18.

McPhail-Bell, K., Bond, C., Brough, M. and Fredericks, B., 2016. ‘We don’t tell people what to

do’: ethical practice and Indigenous health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of

Australia, 26(3), pp.195-199.

Morrison, C. and Cameron, P., 2015. The case for environmental strategies to prevent alcohol-

related trauma. Injury, 46(7), pp.1183-1185.

Newton, N.C., Conrod, P.J., Slade, T., Carragher, N., Champion, K.E., Barrett, E.L., Kelly, E.V.,

Nair, N.K., Stapinski, L. and Teesson, M., 2016. The long‐term effectiveness of a selective,

personality‐targeted prevention program in reducing alcohol use and related harms: A cluster

randomized controlled trial. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 57(9), pp.1056-1065.

Pennay, A., Lubman, D.I., and Frei, M., 2014. Alcohol: prevention, policy and primary care

responses. Australian family physician, 43(6), p.356.

Plunk, A.D., Krauss, M.J., Syed‐Mohammed, H., Hur, M., Cavzos‐Rehg, P.A., Bierut, L.J. and

Grucza, R.A., 2016. The impact of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol‐related chronic

disease mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research, 40(8), pp.1761-1768.

Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Fischer, J., Nicholas, R., O'Rourke, K., Pidd, K., & Trifonoff, A.

(2015). Addressing inequities in alcohol consumption and related harms. Health promotion

international, 30(suppl_2), ii20-ii35.

Stockings, E., Hall, W.D., Lynskey, M., Morley, K.I., Reavley, N., Strang, J., Patton, G. and

Degenhardt, L., 2016. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance

use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.280-296.

Tanner-Smith, E.E., and Lipsey, M.W., 2015. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and

young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 51,

pp.1-18.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

HEALTH PROMOTION 10

Wakefield, M.A., Brennan, E., Dunstone, K., Durkin, S.J., Dixon, H.G., Pettigrew, S. and Slater,

M.D., 2017. Features of alcohol harm reduction advertisements that most motivate reduced

drinking among adults: an advertisement response study. BMJ Open, 7(4), p.e014193.

Wilson, H., Stoyanov, S.R., Gandabhai, S., and Baldwin, A., 2016. The quality and accuracy of

mobile apps to prevent driving after drinking alcohol. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(3), p.e98.

Wilson, I.M., Graham, K. and Taft, A., 2014. Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy, and intimate

partner violence: a systematic review. BMC public health, 14(1), p.881.

Young, B., Lewis, S., Katikireddi, S.V., Bauld, L., Stead, M., Angus, K., Campbell, M., Hilton,

S., Thomas, J., Hinds, K. and Ashie, A., 2018. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns to reduce

alcohol consumption and harm: a systematic review. Alcohol and alcoholism, 53(3), pp.302-316.

Wakefield, M.A., Brennan, E., Dunstone, K., Durkin, S.J., Dixon, H.G., Pettigrew, S. and Slater,

M.D., 2017. Features of alcohol harm reduction advertisements that most motivate reduced

drinking among adults: an advertisement response study. BMJ Open, 7(4), p.e014193.

Wilson, H., Stoyanov, S.R., Gandabhai, S., and Baldwin, A., 2016. The quality and accuracy of

mobile apps to prevent driving after drinking alcohol. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(3), p.e98.

Wilson, I.M., Graham, K. and Taft, A., 2014. Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy, and intimate

partner violence: a systematic review. BMC public health, 14(1), p.881.

Young, B., Lewis, S., Katikireddi, S.V., Bauld, L., Stead, M., Angus, K., Campbell, M., Hilton,

S., Thomas, J., Hinds, K. and Ashie, A., 2018. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns to reduce

alcohol consumption and harm: a systematic review. Alcohol and alcoholism, 53(3), pp.302-316.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

HEALTH PROMOTION 11

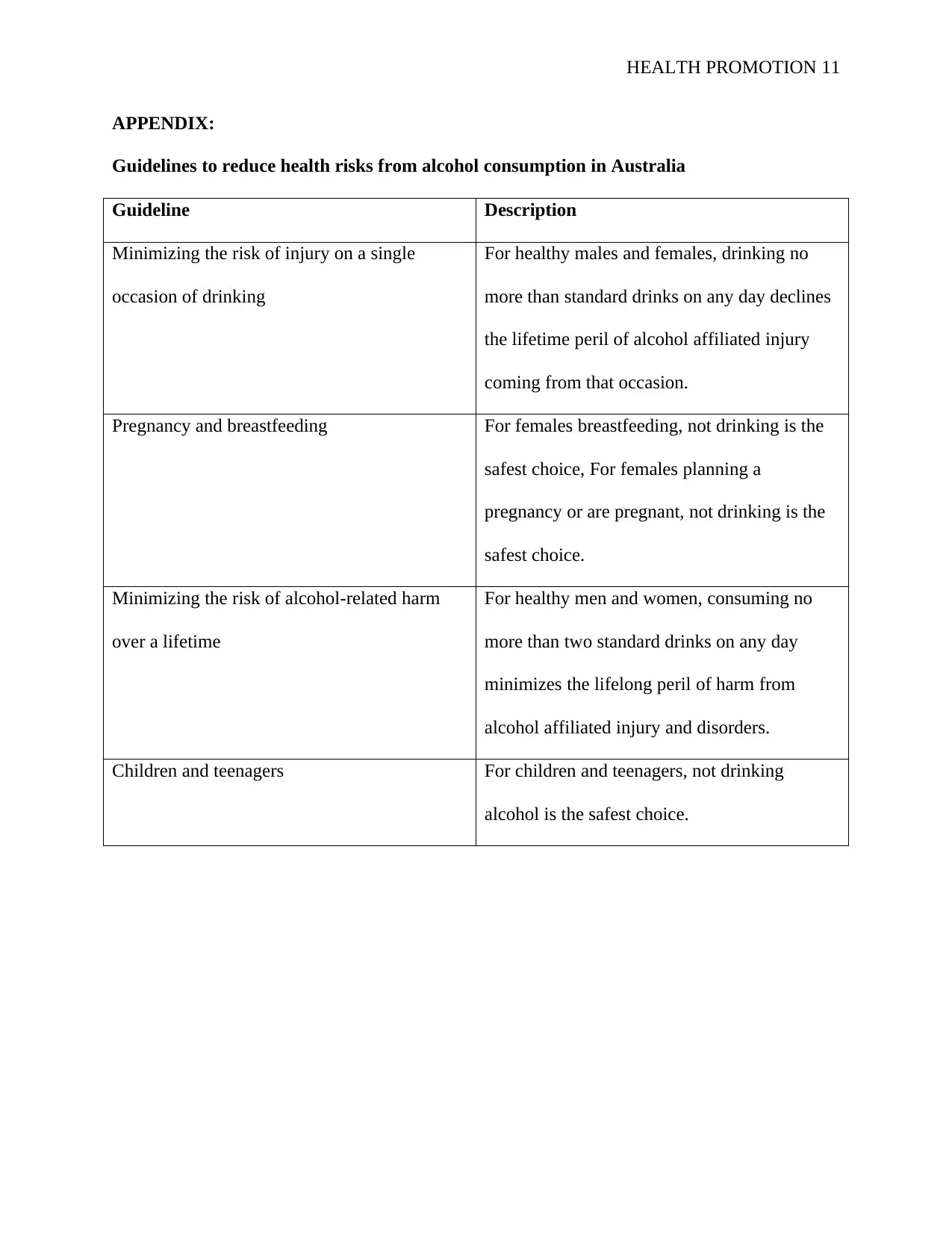

APPENDIX:

Guidelines to reduce health risks from alcohol consumption in Australia

Guideline Description

Minimizing the risk of injury on a single

occasion of drinking

For healthy males and females, drinking no

more than standard drinks on any day declines

the lifetime peril of alcohol affiliated injury

coming from that occasion.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding For females breastfeeding, not drinking is the

safest choice, For females planning a

pregnancy or are pregnant, not drinking is the

safest choice.

Minimizing the risk of alcohol-related harm

over a lifetime

For healthy men and women, consuming no

more than two standard drinks on any day

minimizes the lifelong peril of harm from

alcohol affiliated injury and disorders.

Children and teenagers For children and teenagers, not drinking

alcohol is the safest choice.

APPENDIX:

Guidelines to reduce health risks from alcohol consumption in Australia

Guideline Description

Minimizing the risk of injury on a single

occasion of drinking

For healthy males and females, drinking no

more than standard drinks on any day declines

the lifetime peril of alcohol affiliated injury

coming from that occasion.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding For females breastfeeding, not drinking is the

safest choice, For females planning a

pregnancy or are pregnant, not drinking is the

safest choice.

Minimizing the risk of alcohol-related harm

over a lifetime

For healthy men and women, consuming no

more than two standard drinks on any day

minimizes the lifelong peril of harm from

alcohol affiliated injury and disorders.

Children and teenagers For children and teenagers, not drinking

alcohol is the safest choice.

1 out of 11

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.