Macroeconomic Principles: Analysis of Economic Policies and Models

VerifiedAdded on 2020/03/16

|7

|1601

|361

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment delves into key macroeconomic principles, analyzing the effects of a unit carbon tax on market externalities, the impact of declining consumer confidence on aggregate demand using the Keynesian cross model, and the complexities of measuring the Australian unemployment rate, including alternative perspectives on its estimation. Furthermore, it examines the aggregate expenditure function, calculating the equilibrium level of income and the foreign trade multiplier in an open economy. The assignment utilizes economic models and real-world examples to illustrate these concepts, supported by references to academic sources and news articles.

Running Head: Macroeconomic Principles

Macroeconomic Principles

By (Name)

(Tutor)

(University)

(Date)

Macroeconomic Principles

By (Name)

(Tutor)

(University)

(Date)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Macroeconomic Principles 2

Macroeconomic Principles

Question 1

Part a

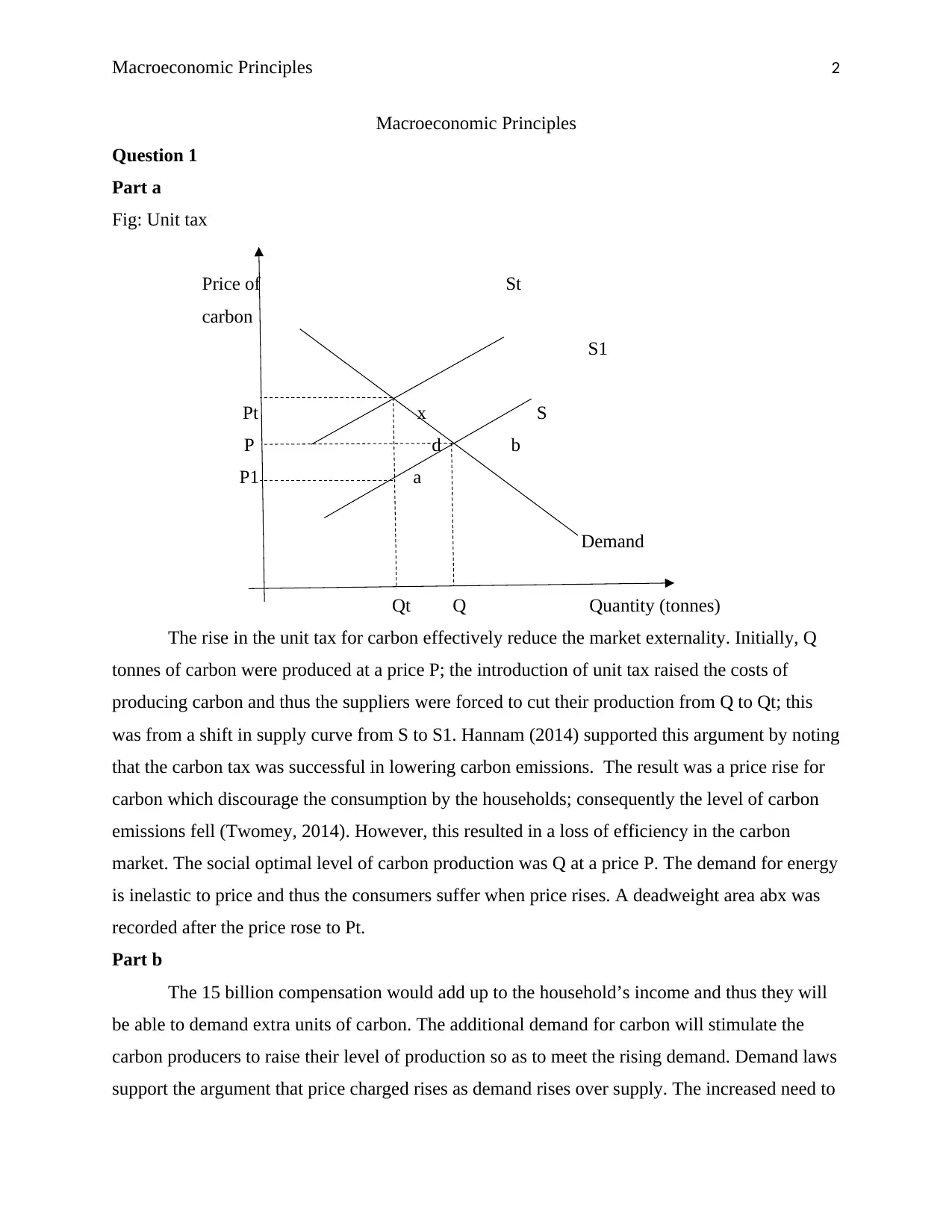

Fig: Unit tax

Price of St

carbon

S1

Pt x S

P d b

P1 a

Demand

Qt Q Quantity (tonnes)

The rise in the unit tax for carbon effectively reduce the market externality. Initially, Q

tonnes of carbon were produced at a price P; the introduction of unit tax raised the costs of

producing carbon and thus the suppliers were forced to cut their production from Q to Qt; this

was from a shift in supply curve from S to S1. Hannam (2014) supported this argument by noting

that the carbon tax was successful in lowering carbon emissions. The result was a price rise for

carbon which discourage the consumption by the households; consequently the level of carbon

emissions fell (Twomey, 2014). However, this resulted in a loss of efficiency in the carbon

market. The social optimal level of carbon production was Q at a price P. The demand for energy

is inelastic to price and thus the consumers suffer when price rises. A deadweight area abx was

recorded after the price rose to Pt.

Part b

The 15 billion compensation would add up to the household’s income and thus they will

be able to demand extra units of carbon. The additional demand for carbon will stimulate the

carbon producers to raise their level of production so as to meet the rising demand. Demand laws

support the argument that price charged rises as demand rises over supply. The increased need to

Macroeconomic Principles

Question 1

Part a

Fig: Unit tax

Price of St

carbon

S1

Pt x S

P d b

P1 a

Demand

Qt Q Quantity (tonnes)

The rise in the unit tax for carbon effectively reduce the market externality. Initially, Q

tonnes of carbon were produced at a price P; the introduction of unit tax raised the costs of

producing carbon and thus the suppliers were forced to cut their production from Q to Qt; this

was from a shift in supply curve from S to S1. Hannam (2014) supported this argument by noting

that the carbon tax was successful in lowering carbon emissions. The result was a price rise for

carbon which discourage the consumption by the households; consequently the level of carbon

emissions fell (Twomey, 2014). However, this resulted in a loss of efficiency in the carbon

market. The social optimal level of carbon production was Q at a price P. The demand for energy

is inelastic to price and thus the consumers suffer when price rises. A deadweight area abx was

recorded after the price rose to Pt.

Part b

The 15 billion compensation would add up to the household’s income and thus they will

be able to demand extra units of carbon. The additional demand for carbon will stimulate the

carbon producers to raise their level of production so as to meet the rising demand. Demand laws

support the argument that price charged rises as demand rises over supply. The increased need to

Macroeconomic Principles 3

produce more will result in an increased employment since more labor will be a requisite. The

carbon price level will rise one again.

Question 2

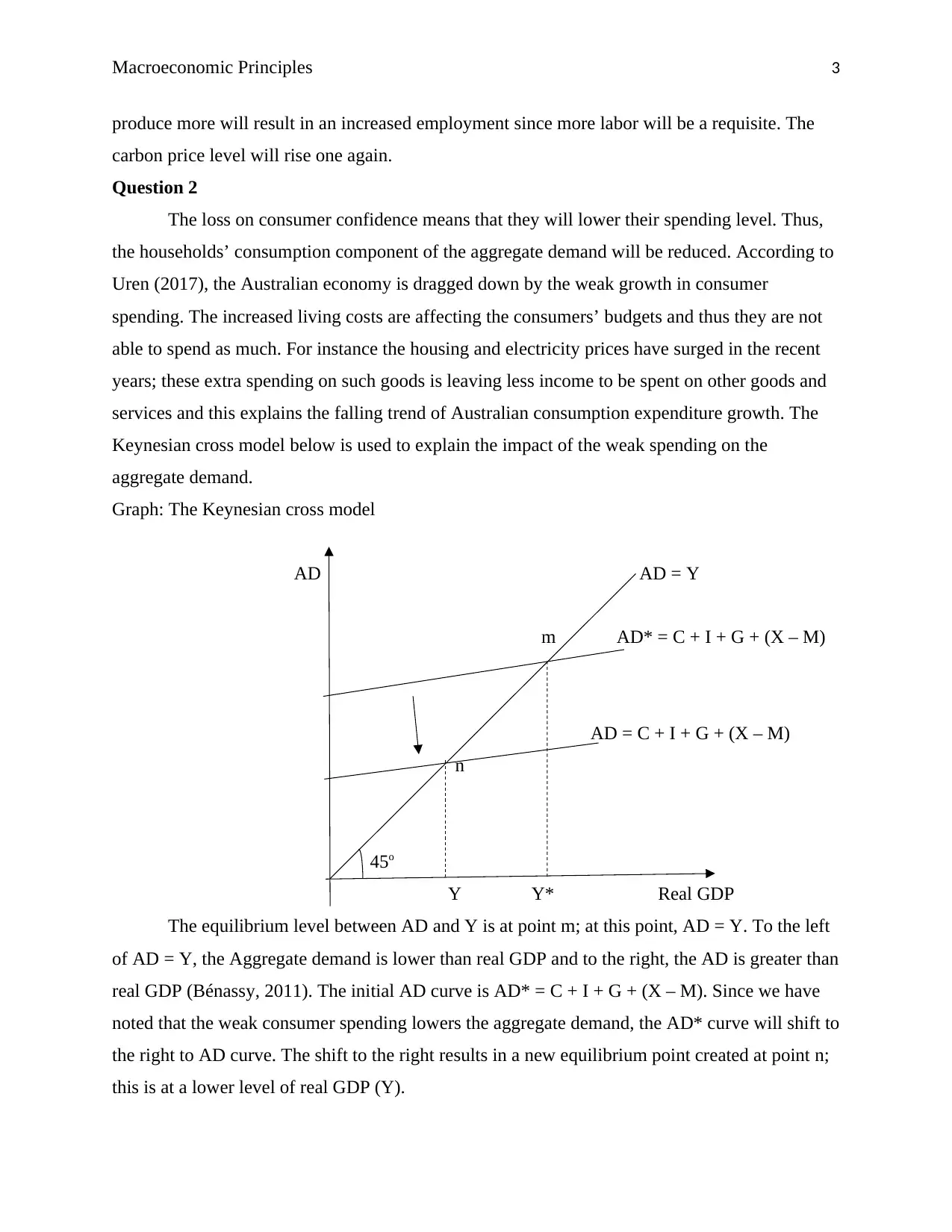

The loss on consumer confidence means that they will lower their spending level. Thus,

the households’ consumption component of the aggregate demand will be reduced. According to

Uren (2017), the Australian economy is dragged down by the weak growth in consumer

spending. The increased living costs are affecting the consumers’ budgets and thus they are not

able to spend as much. For instance the housing and electricity prices have surged in the recent

years; these extra spending on such goods is leaving less income to be spent on other goods and

services and this explains the falling trend of Australian consumption expenditure growth. The

Keynesian cross model below is used to explain the impact of the weak spending on the

aggregate demand.

Graph: The Keynesian cross model

AD AD = Y

m AD* = C + I + G + (X – M)

AD = C + I + G + (X – M)

n

45o

Y Y* Real GDP

The equilibrium level between AD and Y is at point m; at this point, AD = Y. To the left

of AD = Y, the Aggregate demand is lower than real GDP and to the right, the AD is greater than

real GDP (Bénassy, 2011). The initial AD curve is AD* = C + I + G + (X – M). Since we have

noted that the weak consumer spending lowers the aggregate demand, the AD* curve will shift to

the right to AD curve. The shift to the right results in a new equilibrium point created at point n;

this is at a lower level of real GDP (Y).

produce more will result in an increased employment since more labor will be a requisite. The

carbon price level will rise one again.

Question 2

The loss on consumer confidence means that they will lower their spending level. Thus,

the households’ consumption component of the aggregate demand will be reduced. According to

Uren (2017), the Australian economy is dragged down by the weak growth in consumer

spending. The increased living costs are affecting the consumers’ budgets and thus they are not

able to spend as much. For instance the housing and electricity prices have surged in the recent

years; these extra spending on such goods is leaving less income to be spent on other goods and

services and this explains the falling trend of Australian consumption expenditure growth. The

Keynesian cross model below is used to explain the impact of the weak spending on the

aggregate demand.

Graph: The Keynesian cross model

AD AD = Y

m AD* = C + I + G + (X – M)

AD = C + I + G + (X – M)

n

45o

Y Y* Real GDP

The equilibrium level between AD and Y is at point m; at this point, AD = Y. To the left

of AD = Y, the Aggregate demand is lower than real GDP and to the right, the AD is greater than

real GDP (Bénassy, 2011). The initial AD curve is AD* = C + I + G + (X – M). Since we have

noted that the weak consumer spending lowers the aggregate demand, the AD* curve will shift to

the right to AD curve. The shift to the right results in a new equilibrium point created at point n;

this is at a lower level of real GDP (Y).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Macroeconomic Principles 4

Question 3

According to Jericho (2017), the main reason why Adam Creighton claimed that the real

Australian unemployment rate is above 20% is that the estimation for unemployment rate does

not include some many potential workers. the measure include only those who are considered to

be actively seeking; all those who are not actively seeking but could do a job if they had one are

excluded. In an economy like Australia where there is a market failure in the labor market, it

may take long before a potential worker lands into a job. A prolonged duration of job search

discourages some workers and they fail to actively seek a job anymore; the government

estimation of unemployment only considers the four past week’s active seekers. Thus

government’s unemployment data obtained from the statistics bureau may be way lower than

what is the actual Australian unemployment rate.

Creighton’s measure considered not only including the discouraged workers, but also the

retirees and the stay-home-parents who have no employed jobs. Further, he also included the

underemployed in his measure. Some people may be working for only a few hours and be

considered employed; someone working for an hour or two could as well be considered

unemployed since the wage received is insufficient for meeting the personal needs. This hidden

unemployment is difficult to estimate because not all people need a job. Some people are into

businesses and thus may not participate in the labor force. Thus, considering all those seeking

and not seeking unemployment to be unemployed would again bring issues. It is difficult to

determine the job done by every person; most people will be dishonest.

Question 4

Part a

Aggregate Expenditure function

AD = C + I + G + (X - M)

The autonomous expenditure is the spending that has to take place even if the income level was

zero (Yadav, 2014). The consumption expenditure function is C = 40 + 0.9YD. In this case the

autonomous consumption is 40.

Part b

Y = C + I + G + (X - M)

But, C = 40 + 0.9YD; I = 40; G = 60; T = 0.2Y; X = 14 M = 10 + 0.02Y.

Y = 40+ 0.9 YD+ 40+60+(14−(10+ 0.02Y ))

Question 3

According to Jericho (2017), the main reason why Adam Creighton claimed that the real

Australian unemployment rate is above 20% is that the estimation for unemployment rate does

not include some many potential workers. the measure include only those who are considered to

be actively seeking; all those who are not actively seeking but could do a job if they had one are

excluded. In an economy like Australia where there is a market failure in the labor market, it

may take long before a potential worker lands into a job. A prolonged duration of job search

discourages some workers and they fail to actively seek a job anymore; the government

estimation of unemployment only considers the four past week’s active seekers. Thus

government’s unemployment data obtained from the statistics bureau may be way lower than

what is the actual Australian unemployment rate.

Creighton’s measure considered not only including the discouraged workers, but also the

retirees and the stay-home-parents who have no employed jobs. Further, he also included the

underemployed in his measure. Some people may be working for only a few hours and be

considered employed; someone working for an hour or two could as well be considered

unemployed since the wage received is insufficient for meeting the personal needs. This hidden

unemployment is difficult to estimate because not all people need a job. Some people are into

businesses and thus may not participate in the labor force. Thus, considering all those seeking

and not seeking unemployment to be unemployed would again bring issues. It is difficult to

determine the job done by every person; most people will be dishonest.

Question 4

Part a

Aggregate Expenditure function

AD = C + I + G + (X - M)

The autonomous expenditure is the spending that has to take place even if the income level was

zero (Yadav, 2014). The consumption expenditure function is C = 40 + 0.9YD. In this case the

autonomous consumption is 40.

Part b

Y = C + I + G + (X - M)

But, C = 40 + 0.9YD; I = 40; G = 60; T = 0.2Y; X = 14 M = 10 + 0.02Y.

Y = 40+ 0.9 YD+ 40+60+(14−(10+ 0.02Y ))

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Macroeconomic Principles 5

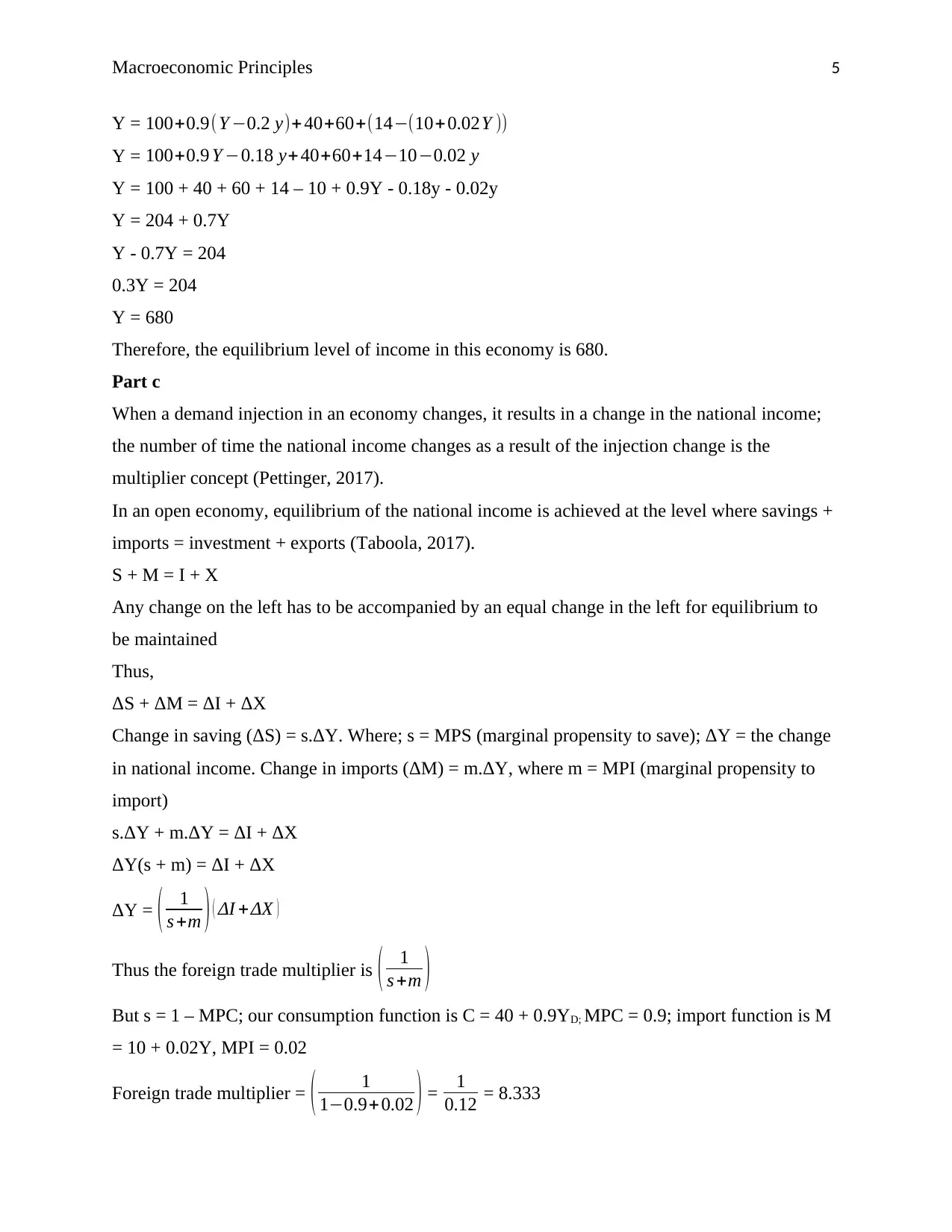

Y = 100+0.9(Y −0.2 y)+ 40+60+(14−(10+0.02Y ))

Y = 100+0.9 Y −0.18 y+ 40+60+14−10−0.02 y

Y = 100 + 40 + 60 + 14 – 10 + 0.9Y - 0.18y - 0.02y

Y = 204 + 0.7Y

Y - 0.7Y = 204

0.3Y = 204

Y = 680

Therefore, the equilibrium level of income in this economy is 680.

Part c

When a demand injection in an economy changes, it results in a change in the national income;

the number of time the national income changes as a result of the injection change is the

multiplier concept (Pettinger, 2017).

In an open economy, equilibrium of the national income is achieved at the level where savings +

imports = investment + exports (Taboola, 2017).

S + M = I + X

Any change on the left has to be accompanied by an equal change in the left for equilibrium to

be maintained

Thus,

ΔS + ΔM = ΔI + ΔX

Change in saving (ΔS) = s.ΔY. Where; s = MPS (marginal propensity to save); ΔY = the change

in national income. Change in imports (ΔM) = m.ΔY, where m = MPI (marginal propensity to

import)

s.ΔY + m.ΔY = ΔI + ΔX

ΔY(s + m) = ΔI + ΔX

ΔY = ( 1

s +m ) ( ΔI +ΔX )

Thus the foreign trade multiplier is ( 1

s +m )

But s = 1 – MPC; our consumption function is C = 40 + 0.9YD; MPC = 0.9; import function is M

= 10 + 0.02Y, MPI = 0.02

Foreign trade multiplier = ( 1

1−0.9+ 0.02 ) = 1

0.12 = 8.333

Y = 100+0.9(Y −0.2 y)+ 40+60+(14−(10+0.02Y ))

Y = 100+0.9 Y −0.18 y+ 40+60+14−10−0.02 y

Y = 100 + 40 + 60 + 14 – 10 + 0.9Y - 0.18y - 0.02y

Y = 204 + 0.7Y

Y - 0.7Y = 204

0.3Y = 204

Y = 680

Therefore, the equilibrium level of income in this economy is 680.

Part c

When a demand injection in an economy changes, it results in a change in the national income;

the number of time the national income changes as a result of the injection change is the

multiplier concept (Pettinger, 2017).

In an open economy, equilibrium of the national income is achieved at the level where savings +

imports = investment + exports (Taboola, 2017).

S + M = I + X

Any change on the left has to be accompanied by an equal change in the left for equilibrium to

be maintained

Thus,

ΔS + ΔM = ΔI + ΔX

Change in saving (ΔS) = s.ΔY. Where; s = MPS (marginal propensity to save); ΔY = the change

in national income. Change in imports (ΔM) = m.ΔY, where m = MPI (marginal propensity to

import)

s.ΔY + m.ΔY = ΔI + ΔX

ΔY(s + m) = ΔI + ΔX

ΔY = ( 1

s +m ) ( ΔI +ΔX )

Thus the foreign trade multiplier is ( 1

s +m )

But s = 1 – MPC; our consumption function is C = 40 + 0.9YD; MPC = 0.9; import function is M

= 10 + 0.02Y, MPI = 0.02

Foreign trade multiplier = ( 1

1−0.9+ 0.02 ) = 1

0.12 = 8.333

Macroeconomic Principles 6

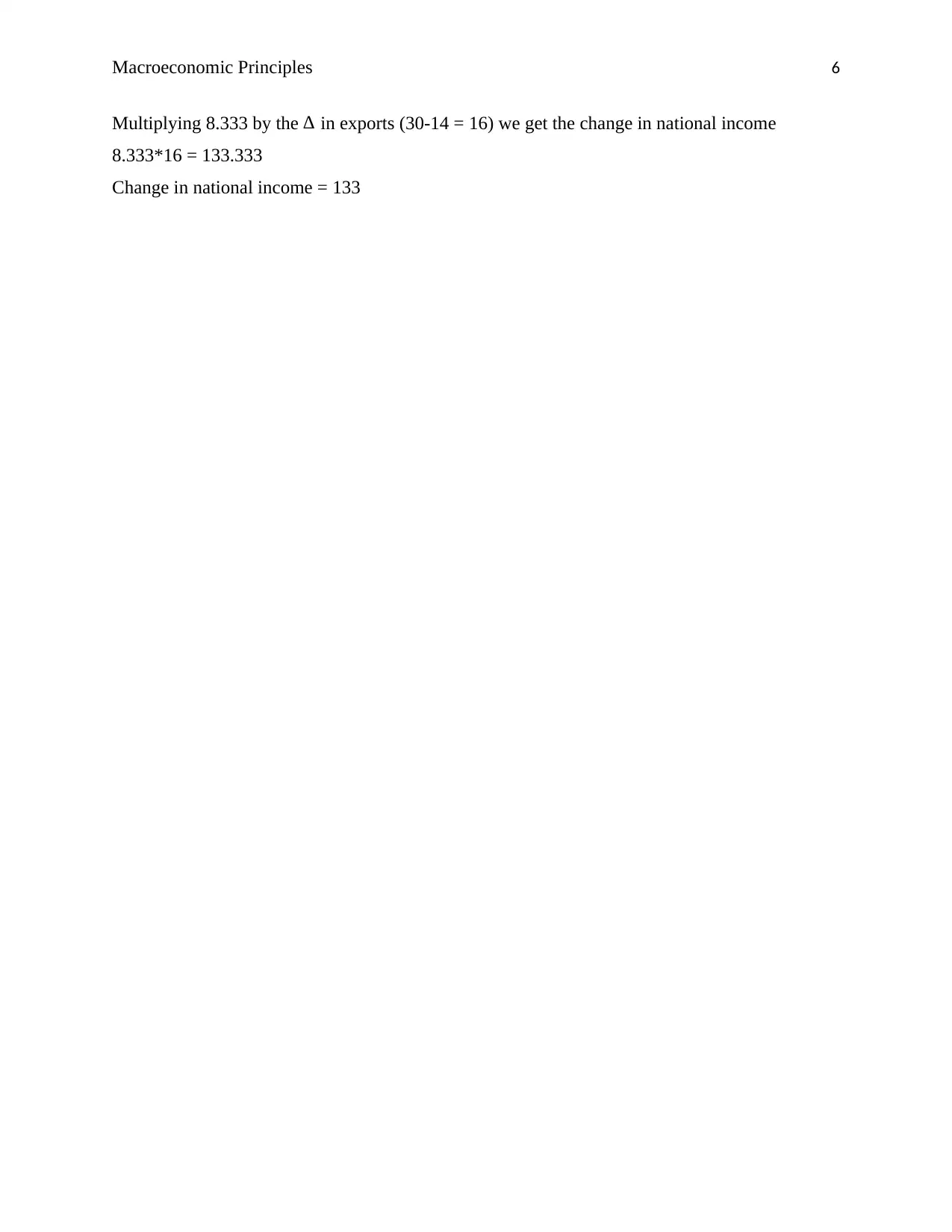

Multiplying 8.333 by the ∆ in exports (30-14 = 16) we get the change in national income

8.333*16 = 133.333

Change in national income = 133

Multiplying 8.333 by the ∆ in exports (30-14 = 16) we get the change in national income

8.333*16 = 133.333

Change in national income = 133

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Macroeconomic Principles 7

References

Bénassy, J. (2011). Macroeconomic theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hannam, P. (2014). Carbon price helped curb emissions, ANU study finds. [Online] The Sydney

Morning Herald. Available at: http://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/carbon-

price-helped-curb-emissions-anu-study-finds-20140716-ztuf6.html [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Jericho, G. (2017). To those who claim Australia's unemployment data is dishonest – please stop

| Greg Jericho. [Online] The Guardian. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/business/grogonomics/2017/may/30/to-those-who-claim-

australias-unemployment-data-is-dishonest-please-stop [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Pettinger, T. (2017). The multiplier effect. [Online] Economicshelp.org. Available at:

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1948/economics/the-multiplier-effect/ [Accessed 2 Oct.

2017].

Taboola (2017). National Income and the Foreign Trade Multiplier. [Online] Economics

Discussion. Available at: http://www.economicsdiscussion.net/national-income/foreign-trade-

multiplier/national-income-and-the-foreign-trade-multiplier-2/10760 [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Twomey, P. (2014). Obituary: Australia's carbon price. [Online] The Conversation. Available

at: https://theconversation.com/obituary-australias-carbon-price-29217 [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Uren, D. (2017). Weak spend a drag on economy. [Online] Theaustralian.com.au. Available at:

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/opinion/david-uren-economics/weak-consumer-

spending-a-drag-on-economic-growth/news-story/5cf5c25bbdb6e119f5ca8517dfc40430

[Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Yadav, G. (2014). How are autonomous expenditures determined? [Online] Quora. Available at:

https://www.quora.com/How-are-autonomous-expenditures-determined [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

References

Bénassy, J. (2011). Macroeconomic theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hannam, P. (2014). Carbon price helped curb emissions, ANU study finds. [Online] The Sydney

Morning Herald. Available at: http://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/carbon-

price-helped-curb-emissions-anu-study-finds-20140716-ztuf6.html [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Jericho, G. (2017). To those who claim Australia's unemployment data is dishonest – please stop

| Greg Jericho. [Online] The Guardian. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/business/grogonomics/2017/may/30/to-those-who-claim-

australias-unemployment-data-is-dishonest-please-stop [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Pettinger, T. (2017). The multiplier effect. [Online] Economicshelp.org. Available at:

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1948/economics/the-multiplier-effect/ [Accessed 2 Oct.

2017].

Taboola (2017). National Income and the Foreign Trade Multiplier. [Online] Economics

Discussion. Available at: http://www.economicsdiscussion.net/national-income/foreign-trade-

multiplier/national-income-and-the-foreign-trade-multiplier-2/10760 [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Twomey, P. (2014). Obituary: Australia's carbon price. [Online] The Conversation. Available

at: https://theconversation.com/obituary-australias-carbon-price-29217 [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Uren, D. (2017). Weak spend a drag on economy. [Online] Theaustralian.com.au. Available at:

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/opinion/david-uren-economics/weak-consumer-

spending-a-drag-on-economic-growth/news-story/5cf5c25bbdb6e119f5ca8517dfc40430

[Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Yadav, G. (2014). How are autonomous expenditures determined? [Online] Quora. Available at:

https://www.quora.com/How-are-autonomous-expenditures-determined [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

1 out of 7

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.