Comprehensive Report: State of Australian Economy 2016-2017

VerifiedAdded on 2020/04/07

|12

|2817

|36

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the Australian economy from August 2016 to September 2017. It examines key economic indicators, including Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, inflation rates, and unemployment figures, highlighting the impact of commodity price fluctuations and domestic demand. The report delves into the state of the Australian economy, covering GDP trends, inflation in tradeable and non-tradeable goods, and unemployment rates. Furthermore, it assesses the current account, exchange rates, and net foreign debt, as well as the terms of trade. Growth concerns, such as domestic consumption, international economic uncertainties (particularly those related to China), and labor productivity are also discussed. The report concludes with an outlook for 2018, predicting stronger growth and reduced unemployment, driven by factors like increased wages and favorable international trade conditions. The analysis draws on data from sources such as the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, providing a detailed and insightful overview of the Australian economic landscape during the specified period.

State of the Australian Economy

2016- 2017

2016- 2017

The Australian Economy witnessed a sort of comeback in the period

between August 2016 and September 2017 led by the resurgence of

commodity prices in the international market and strong domestic

demand. This strong growth is expected to continue in the next twelve

months with a few concerns but an overall positive outlook.

2016- 2017

2016- 2017

The Australian Economy witnessed a sort of comeback in the period

between August 2016 and September 2017 led by the resurgence of

commodity prices in the international market and strong domestic

demand. This strong growth is expected to continue in the next twelve

months with a few concerns but an overall positive outlook.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1. Introduction

August 2016 was a time when the Australian economy was witnessing a drag in the GDP growth due to a

slowdown in the global commodity market. This changed considerably during the period of August 2016

and September 2017 as the economy experienced a come back from the lows of the previous quarters

that were largely caused due to the end of a commodity super cycle. (Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development, 2017) The economy of Australia has seen stability in the period since

August 2016, partly due to the end of the decline in commodity market and partly due to high domestic

consumption.

2. The Current State of Australian Economy

2.1 Gross Domestic Product

The GDP growth declined between November 2016 - February 2017 due to a decrease in the

decline in construction activities and disruptions in coal supply owing to bad weather. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017). However, the growth rate picked up sharply.

Table 1 Australia’s Nominal Gross Domestic Product . Source (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Year

Nominal GDP

(in Million $)

Year on Year Real

GDP Growth Rate

Jun-16 420254 3.2

Sep-16 418441 1.9

Dec-16 423034 2.4

Mar-17 424450 1.8

Jun-17 427948 1.8

The end of the boom in the commodity market has led to an imbalanced GDP growth. States like

Queensland and Western Australia where the resources sector has a greater contribution to

output have experienced a slower growth. States where non mining economy is proportionately

stronger have experienced better growth since non mining investment has remained high. Non

August 2016 was a time when the Australian economy was witnessing a drag in the GDP growth due to a

slowdown in the global commodity market. This changed considerably during the period of August 2016

and September 2017 as the economy experienced a come back from the lows of the previous quarters

that were largely caused due to the end of a commodity super cycle. (Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development, 2017) The economy of Australia has seen stability in the period since

August 2016, partly due to the end of the decline in commodity market and partly due to high domestic

consumption.

2. The Current State of Australian Economy

2.1 Gross Domestic Product

The GDP growth declined between November 2016 - February 2017 due to a decrease in the

decline in construction activities and disruptions in coal supply owing to bad weather. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017). However, the growth rate picked up sharply.

Table 1 Australia’s Nominal Gross Domestic Product . Source (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Year

Nominal GDP

(in Million $)

Year on Year Real

GDP Growth Rate

Jun-16 420254 3.2

Sep-16 418441 1.9

Dec-16 423034 2.4

Mar-17 424450 1.8

Jun-17 427948 1.8

The end of the boom in the commodity market has led to an imbalanced GDP growth. States like

Queensland and Western Australia where the resources sector has a greater contribution to

output have experienced a slower growth. States where non mining economy is proportionately

stronger have experienced better growth since non mining investment has remained high. Non

mining investment remained high in the states of Victoria and New South Wales. (Australian

Bureau of Statistics, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

However, in spite of the decline in mining investment the GDP growth has not slowed down and

a reason for this could be domestic consumption. The low rates of interest, and household

perceptions of their finances helped the sales in the retail sector to remain high. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017) (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017)

Table 2: Australia GDP Growth and GDP Growth Forecasts . Source Reserve Bank of Australia (2016)

Year-ended

Dec 2016 Jun 2017 Dec 2017 Jun 2018 Dec 2018

GDP growth 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 3–4

CPI inflation 1½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½

Underlying inflation 1½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½

2016 2016/17 2017 2017/18 2018

GDP growth 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½

2.2 Inflation

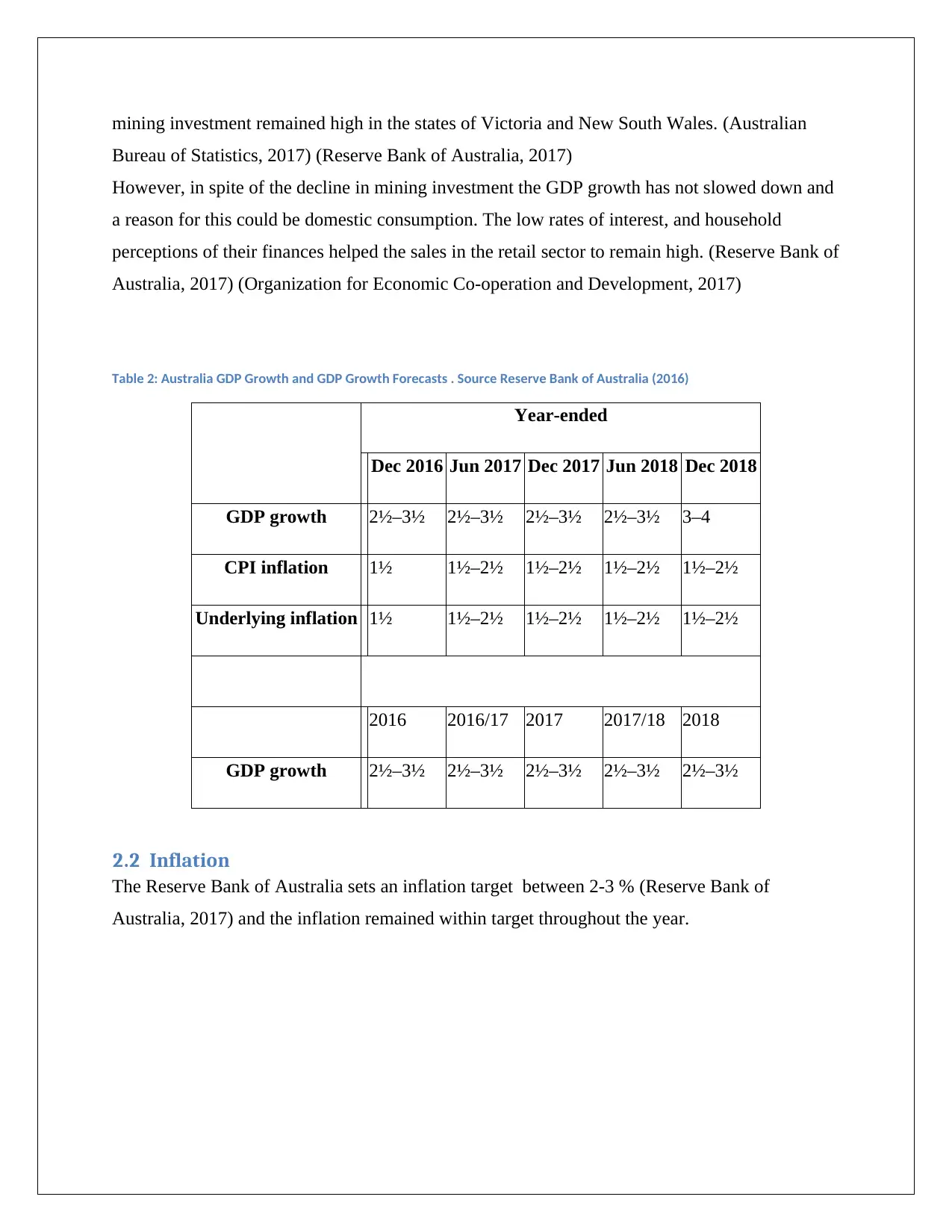

The Reserve Bank of Australia sets an inflation target between 2-3 % (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017) and the inflation remained within target throughout the year.

Bureau of Statistics, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

However, in spite of the decline in mining investment the GDP growth has not slowed down and

a reason for this could be domestic consumption. The low rates of interest, and household

perceptions of their finances helped the sales in the retail sector to remain high. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017) (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017)

Table 2: Australia GDP Growth and GDP Growth Forecasts . Source Reserve Bank of Australia (2016)

Year-ended

Dec 2016 Jun 2017 Dec 2017 Jun 2018 Dec 2018

GDP growth 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 3–4

CPI inflation 1½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½

Underlying inflation 1½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½ 1½–2½

2016 2016/17 2017 2017/18 2018

GDP growth 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½ 2½–3½

2.2 Inflation

The Reserve Bank of Australia sets an inflation target between 2-3 % (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017) and the inflation remained within target throughout the year.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Jun-16

Jul-16

Aug-16

Sep-16

Oct-16

Nov-16

Dec-16

Jan-17

Feb-17

Mar-17

Apr-17

May-17

Jun-17

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Chart Title

Year Ended Inflation

Change

Graph 1 The Change in Inflation (CPI) Rate of Australia (Year-on -Year) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

A common trend throughout the year has been the increase of inflation in non tradeable goods

and a deflation of prices in tradeable goods. An increase in non-tradeable items implies greater

domestic demand or a higher consumer spending. The non-tradeable inflation represents

consumption of services such as hospital services, alcohol, tobacco etc.

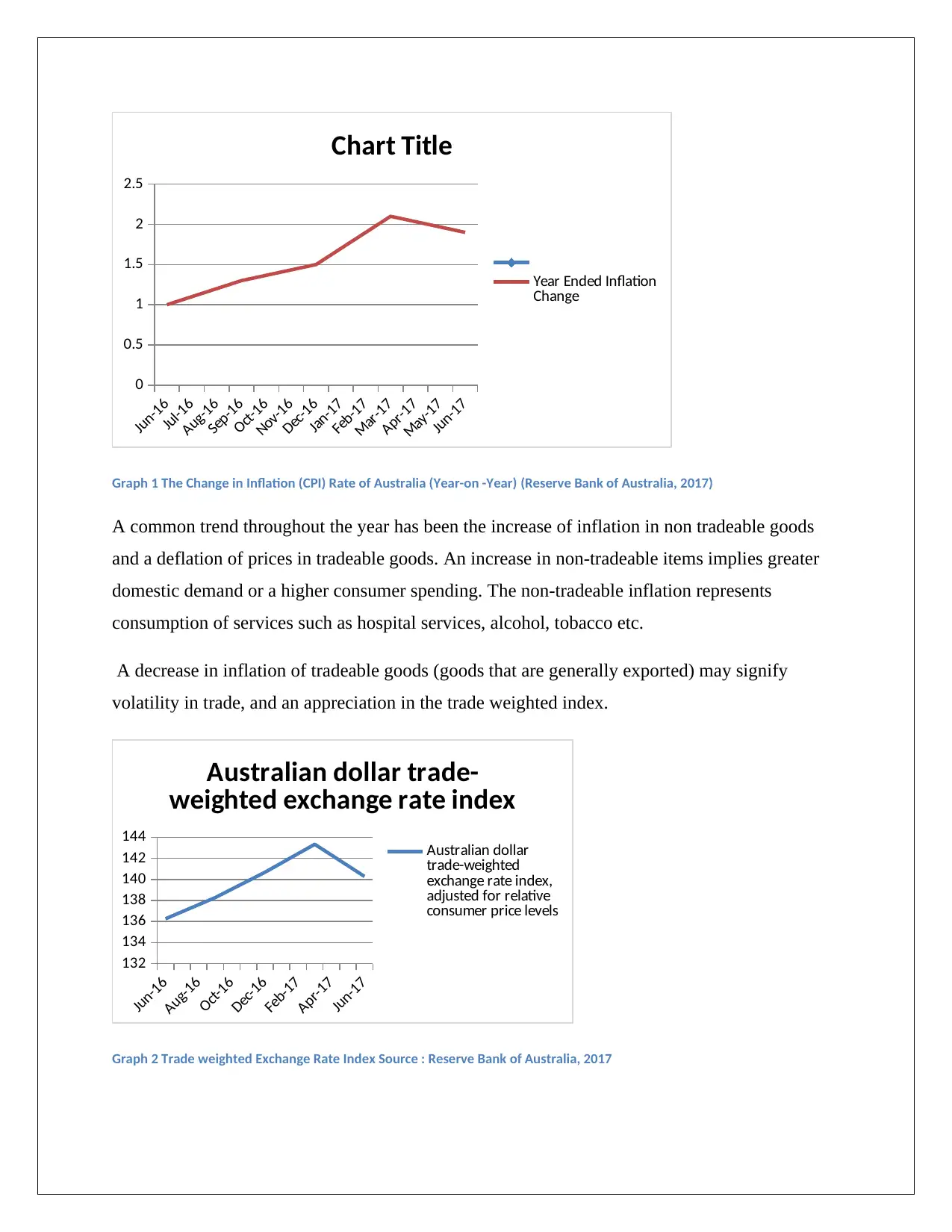

A decrease in inflation of tradeable goods (goods that are generally exported) may signify

volatility in trade, and an appreciation in the trade weighted index.

Jun-16

Aug-16

Oct-16

Dec-16

Feb-17

Apr-17

Jun-17

132

134

136

138

140

142

144

Australian dollar trade-

weighted exchange rate index

Australian dollar

trade-weighted

exchange rate index,

adjusted for relative

consumer price levels

Graph 2 Trade weighted Exchange Rate Index Source : Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017

Jul-16

Aug-16

Sep-16

Oct-16

Nov-16

Dec-16

Jan-17

Feb-17

Mar-17

Apr-17

May-17

Jun-17

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Chart Title

Year Ended Inflation

Change

Graph 1 The Change in Inflation (CPI) Rate of Australia (Year-on -Year) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

A common trend throughout the year has been the increase of inflation in non tradeable goods

and a deflation of prices in tradeable goods. An increase in non-tradeable items implies greater

domestic demand or a higher consumer spending. The non-tradeable inflation represents

consumption of services such as hospital services, alcohol, tobacco etc.

A decrease in inflation of tradeable goods (goods that are generally exported) may signify

volatility in trade, and an appreciation in the trade weighted index.

Jun-16

Aug-16

Oct-16

Dec-16

Feb-17

Apr-17

Jun-17

132

134

136

138

140

142

144

Australian dollar trade-

weighted exchange rate index

Australian dollar

trade-weighted

exchange rate index,

adjusted for relative

consumer price levels

Graph 2 Trade weighted Exchange Rate Index Source : Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

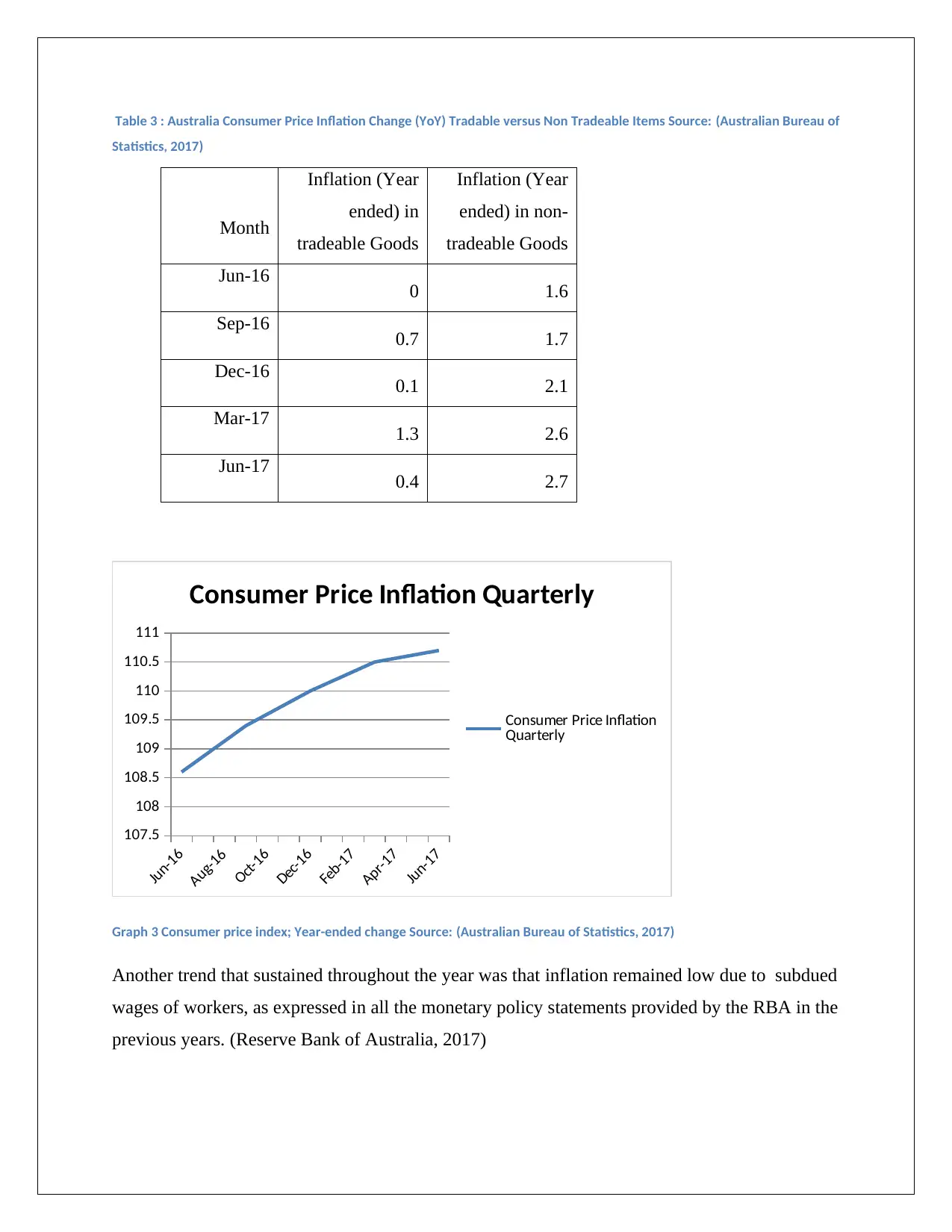

Table 3 : Australia Consumer Price Inflation Change (YoY) Tradable versus Non Tradeable Items Source: (Australian Bureau of

Statistics, 2017)

Jun-16

Aug-16

Oct-16

Dec-16

Feb-17

Apr-17

Jun-17

107.5

108

108.5

109

109.5

110

110.5

111

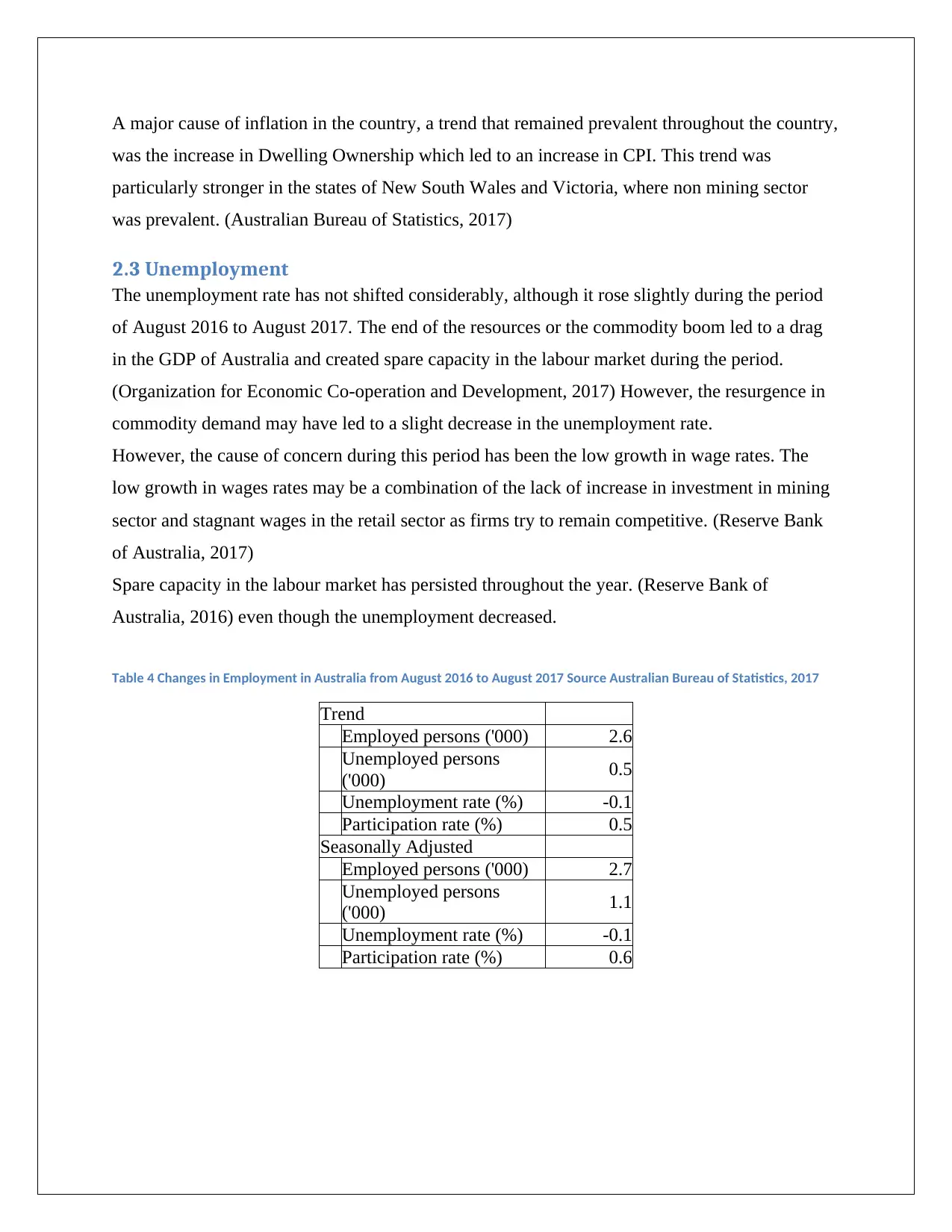

Consumer Price Inflation Quarterly

Consumer Price Inflation

Quarterly

Graph 3 Consumer price index; Year-ended change Source: (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017)

Another trend that sustained throughout the year was that inflation remained low due to subdued

wages of workers, as expressed in all the monetary policy statements provided by the RBA in the

previous years. (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Month

Inflation (Year

ended) in

tradeable Goods

Inflation (Year

ended) in non-

tradeable Goods

Jun-16 0 1.6

Sep-16 0.7 1.7

Dec-16 0.1 2.1

Mar-17 1.3 2.6

Jun-17 0.4 2.7

Statistics, 2017)

Jun-16

Aug-16

Oct-16

Dec-16

Feb-17

Apr-17

Jun-17

107.5

108

108.5

109

109.5

110

110.5

111

Consumer Price Inflation Quarterly

Consumer Price Inflation

Quarterly

Graph 3 Consumer price index; Year-ended change Source: (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017)

Another trend that sustained throughout the year was that inflation remained low due to subdued

wages of workers, as expressed in all the monetary policy statements provided by the RBA in the

previous years. (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Month

Inflation (Year

ended) in

tradeable Goods

Inflation (Year

ended) in non-

tradeable Goods

Jun-16 0 1.6

Sep-16 0.7 1.7

Dec-16 0.1 2.1

Mar-17 1.3 2.6

Jun-17 0.4 2.7

A major cause of inflation in the country, a trend that remained prevalent throughout the country,

was the increase in Dwelling Ownership which led to an increase in CPI. This trend was

particularly stronger in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, where non mining sector

was prevalent. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017)

2.3 Unemployment

The unemployment rate has not shifted considerably, although it rose slightly during the period

of August 2016 to August 2017. The end of the resources or the commodity boom led to a drag

in the GDP of Australia and created spare capacity in the labour market during the period.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017) However, the resurgence in

commodity demand may have led to a slight decrease in the unemployment rate.

However, the cause of concern during this period has been the low growth in wage rates. The

low growth in wages rates may be a combination of the lack of increase in investment in mining

sector and stagnant wages in the retail sector as firms try to remain competitive. (Reserve Bank

of Australia, 2017)

Spare capacity in the labour market has persisted throughout the year. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2016) even though the unemployment decreased.

Table 4 Changes in Employment in Australia from August 2016 to August 2017 Source Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017

Trend

Employed persons ('000) 2.6

Unemployed persons

('000) 0.5

Unemployment rate (%) -0.1

Participation rate (%) 0.5

Seasonally Adjusted

Employed persons ('000) 2.7

Unemployed persons

('000) 1.1

Unemployment rate (%) -0.1

Participation rate (%) 0.6

was the increase in Dwelling Ownership which led to an increase in CPI. This trend was

particularly stronger in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, where non mining sector

was prevalent. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017)

2.3 Unemployment

The unemployment rate has not shifted considerably, although it rose slightly during the period

of August 2016 to August 2017. The end of the resources or the commodity boom led to a drag

in the GDP of Australia and created spare capacity in the labour market during the period.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017) However, the resurgence in

commodity demand may have led to a slight decrease in the unemployment rate.

However, the cause of concern during this period has been the low growth in wage rates. The

low growth in wages rates may be a combination of the lack of increase in investment in mining

sector and stagnant wages in the retail sector as firms try to remain competitive. (Reserve Bank

of Australia, 2017)

Spare capacity in the labour market has persisted throughout the year. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2016) even though the unemployment decreased.

Table 4 Changes in Employment in Australia from August 2016 to August 2017 Source Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017

Trend

Employed persons ('000) 2.6

Unemployed persons

('000) 0.5

Unemployment rate (%) -0.1

Participation rate (%) 0.5

Seasonally Adjusted

Employed persons ('000) 2.7

Unemployed persons

('000) 1.1

Unemployment rate (%) -0.1

Participation rate (%) 0.6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

2.4 Trade

2.4.1 Current Account

Growth in global industrial production and merchandise trade picked up in late 2016 (as

compared to the previous quarters) but commodity prices remained low. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017). This led to better and helped reduce the Current Account Deficit in the Quarter

of August – November 2017. The Current Account Deficit fell sharply during the latter half of

2017 but increased between March and June 2017. The mining investment in the country has

declined in the past and is not expected to pick up in the near future. (Organization for Economic

Co-operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017). Investment in mining

implies import of capital goods and a decline in investment results in a decline in imports of

heavy goods (Thirlwell, 2017) Additionally, given the low rates of investment, the dividends

paid out to the foreign owners of Companies in Australia also lowered, contributing to the

reduction in deficit. (Gittins, 2017) Since, the investment has decline, the current account deficit

is not widening.

Table 5 Australian Current Account Deficit as Percentage of GDP. Source (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Quarter Current Account Deficit

Jun-2016 -3.7

Sep-2016 -2.6

Dec-2016 -0.8

Mar-2017 -1.1

Jun-2017 -2.1

2.4.1 Current Account

Growth in global industrial production and merchandise trade picked up in late 2016 (as

compared to the previous quarters) but commodity prices remained low. (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017). This led to better and helped reduce the Current Account Deficit in the Quarter

of August – November 2017. The Current Account Deficit fell sharply during the latter half of

2017 but increased between March and June 2017. The mining investment in the country has

declined in the past and is not expected to pick up in the near future. (Organization for Economic

Co-operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017). Investment in mining

implies import of capital goods and a decline in investment results in a decline in imports of

heavy goods (Thirlwell, 2017) Additionally, given the low rates of investment, the dividends

paid out to the foreign owners of Companies in Australia also lowered, contributing to the

reduction in deficit. (Gittins, 2017) Since, the investment has decline, the current account deficit

is not widening.

Table 5 Australian Current Account Deficit as Percentage of GDP. Source (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Quarter Current Account Deficit

Jun-2016 -3.7

Sep-2016 -2.6

Dec-2016 -0.8

Mar-2017 -1.1

Jun-2017 -2.1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

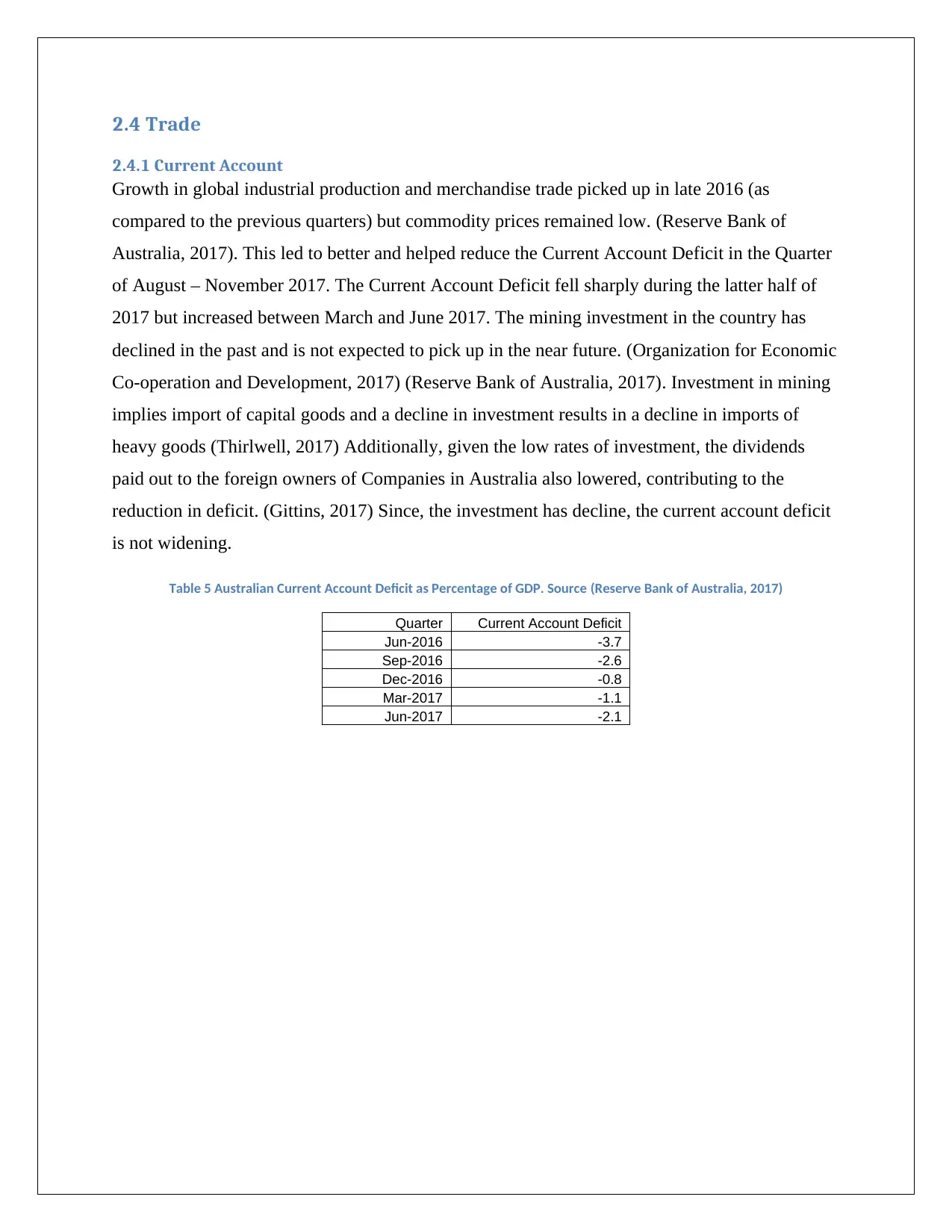

2.4.2 Exchange Rate

18-Aug-16

20-Sep-16

23-Oct-16

25-Nov-16

28-Dec-16

30-Jan-17

4-Mar-17

6-Apr-17

9-May-17

11-Jun-17

14-Jul-17

16-Aug-17

18-Sep-17

0.66

0.68

0.7

0.72

0.74

0.76

0.78

0.8

0.82

Rate of Exchange (AUD/USD)

Rate of Exchange

(AUD/USD)

Graph 4: The Nominal Rate of Exchange of AUD Vs USD. Source Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017

The Australian Dollar depreciated in last quarter of 2016. This helped improve the value of

Overseas Dividend Receipts of Australia held by foreign creditors. (Thirlwell, 2017)

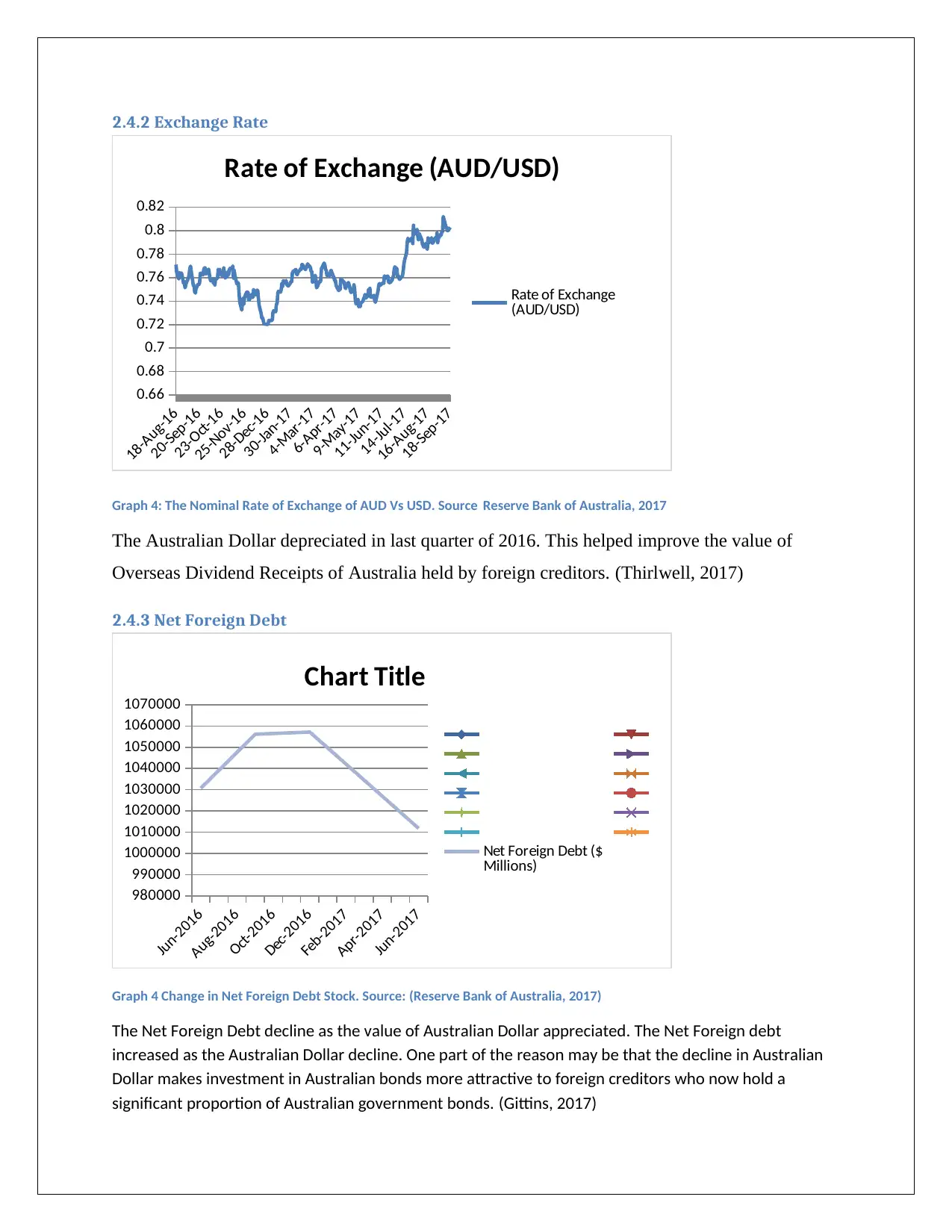

2.4.3 Net Foreign Debt

Jun-2016

Aug-2016

Oct-2016

Dec-2016

Feb-2017

Apr-2017

Jun-2017

980000

990000

1000000

1010000

1020000

1030000

1040000

1050000

1060000

1070000

Chart Title

Net Foreign Debt ($

Millions)

Graph 4 Change in Net Foreign Debt Stock. Source: (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

The Net Foreign Debt decline as the value of Australian Dollar appreciated. The Net Foreign debt

increased as the Australian Dollar decline. One part of the reason may be that the decline in Australian

Dollar makes investment in Australian bonds more attractive to foreign creditors who now hold a

significant proportion of Australian government bonds. (Gittins, 2017)

18-Aug-16

20-Sep-16

23-Oct-16

25-Nov-16

28-Dec-16

30-Jan-17

4-Mar-17

6-Apr-17

9-May-17

11-Jun-17

14-Jul-17

16-Aug-17

18-Sep-17

0.66

0.68

0.7

0.72

0.74

0.76

0.78

0.8

0.82

Rate of Exchange (AUD/USD)

Rate of Exchange

(AUD/USD)

Graph 4: The Nominal Rate of Exchange of AUD Vs USD. Source Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017

The Australian Dollar depreciated in last quarter of 2016. This helped improve the value of

Overseas Dividend Receipts of Australia held by foreign creditors. (Thirlwell, 2017)

2.4.3 Net Foreign Debt

Jun-2016

Aug-2016

Oct-2016

Dec-2016

Feb-2017

Apr-2017

Jun-2017

980000

990000

1000000

1010000

1020000

1030000

1040000

1050000

1060000

1070000

Chart Title

Net Foreign Debt ($

Millions)

Graph 4 Change in Net Foreign Debt Stock. Source: (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

The Net Foreign Debt decline as the value of Australian Dollar appreciated. The Net Foreign debt

increased as the Australian Dollar decline. One part of the reason may be that the decline in Australian

Dollar makes investment in Australian bonds more attractive to foreign creditors who now hold a

significant proportion of Australian government bonds. (Gittins, 2017)

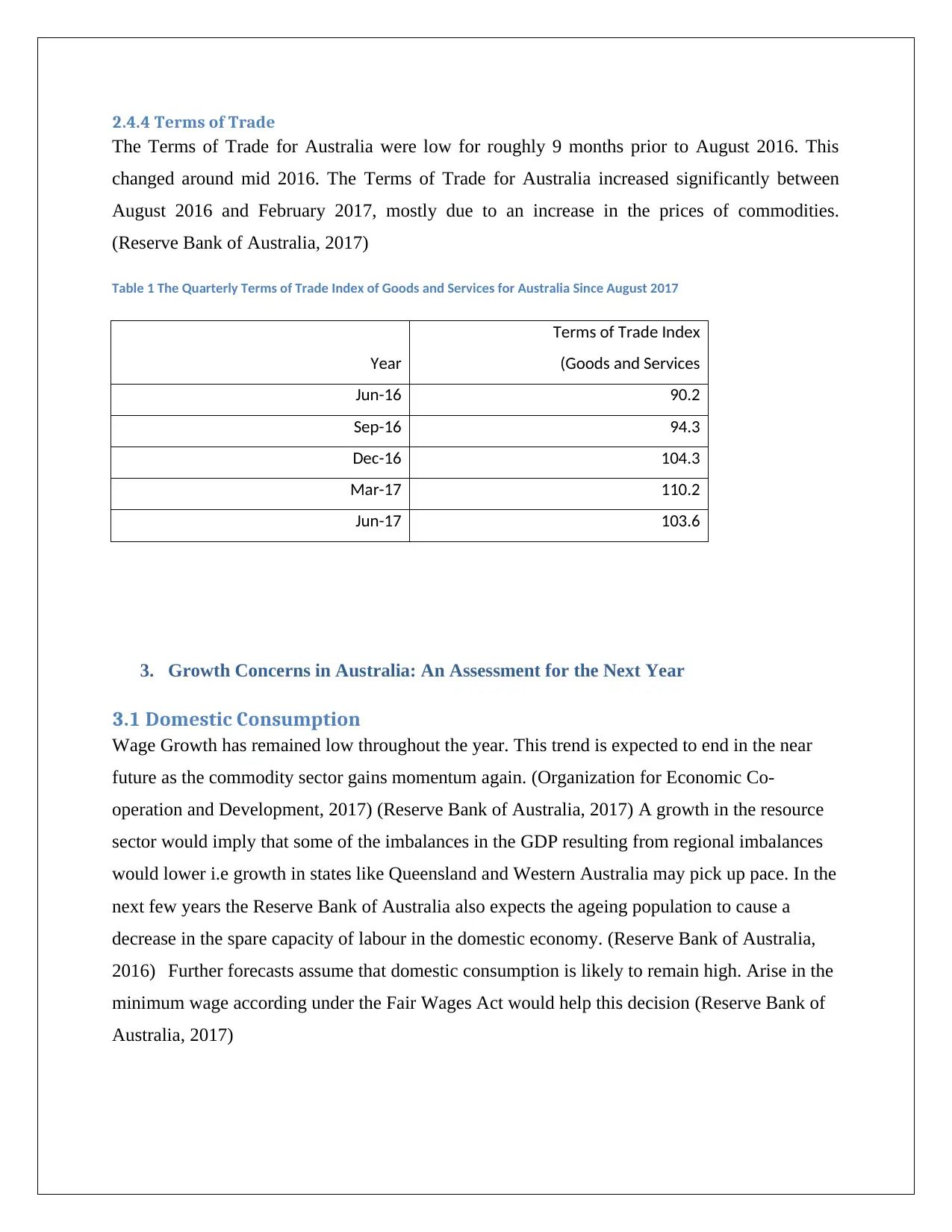

2.4.4 Terms of Trade

The Terms of Trade for Australia were low for roughly 9 months prior to August 2016. This

changed around mid 2016. The Terms of Trade for Australia increased significantly between

August 2016 and February 2017, mostly due to an increase in the prices of commodities.

(Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Table 1 The Quarterly Terms of Trade Index of Goods and Services for Australia Since August 2017

Year

Terms of Trade Index

(Goods and Services

Jun-16 90.2

Sep-16 94.3

Dec-16 104.3

Mar-17 110.2

Jun-17 103.6

3. Growth Concerns in Australia: An Assessment for the Next Year

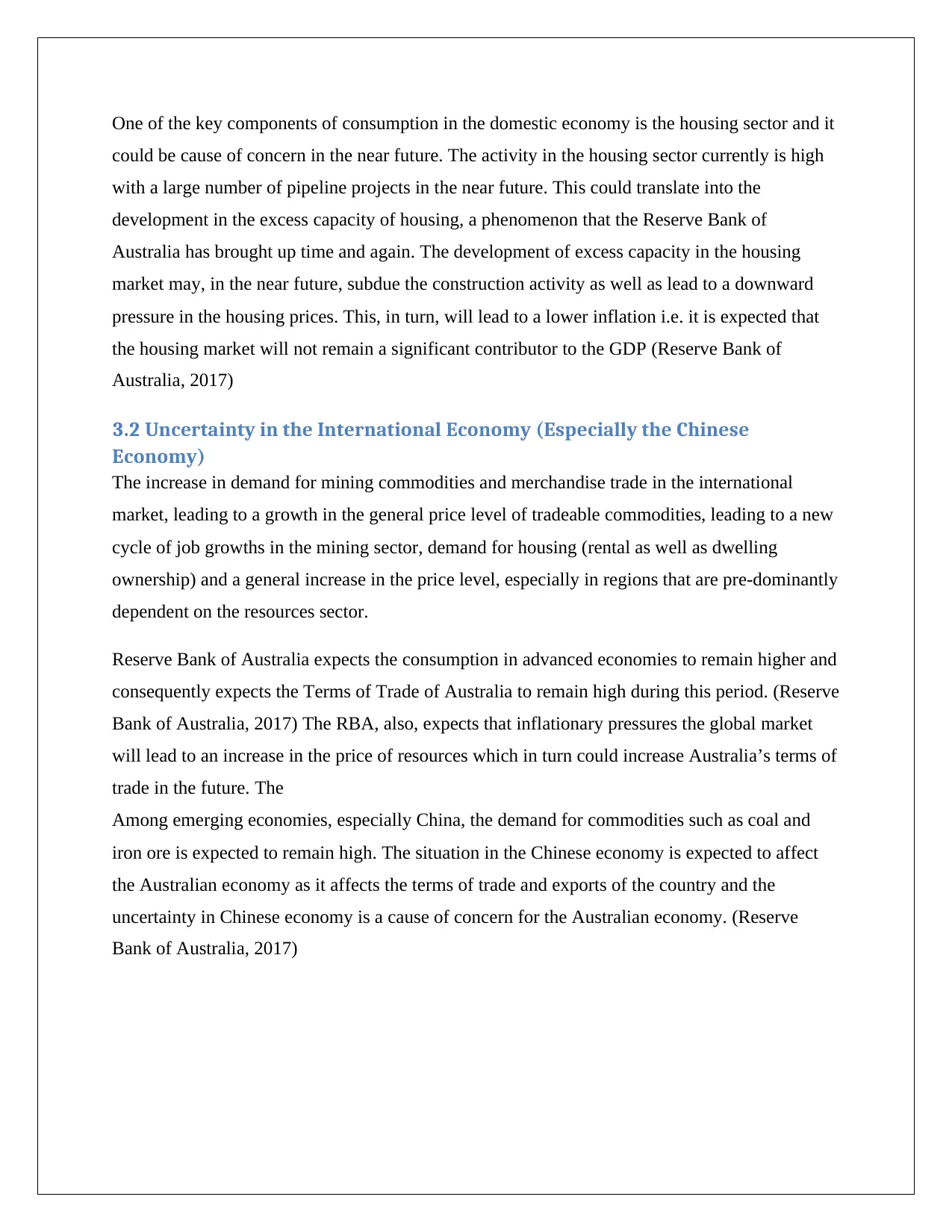

3.1 Domestic Consumption

Wage Growth has remained low throughout the year. This trend is expected to end in the near

future as the commodity sector gains momentum again. (Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017) A growth in the resource

sector would imply that some of the imbalances in the GDP resulting from regional imbalances

would lower i.e growth in states like Queensland and Western Australia may pick up pace. In the

next few years the Reserve Bank of Australia also expects the ageing population to cause a

decrease in the spare capacity of labour in the domestic economy. (Reserve Bank of Australia,

2016) Further forecasts assume that domestic consumption is likely to remain high. Arise in the

minimum wage according under the Fair Wages Act would help this decision (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017)

The Terms of Trade for Australia were low for roughly 9 months prior to August 2016. This

changed around mid 2016. The Terms of Trade for Australia increased significantly between

August 2016 and February 2017, mostly due to an increase in the prices of commodities.

(Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017)

Table 1 The Quarterly Terms of Trade Index of Goods and Services for Australia Since August 2017

Year

Terms of Trade Index

(Goods and Services

Jun-16 90.2

Sep-16 94.3

Dec-16 104.3

Mar-17 110.2

Jun-17 103.6

3. Growth Concerns in Australia: An Assessment for the Next Year

3.1 Domestic Consumption

Wage Growth has remained low throughout the year. This trend is expected to end in the near

future as the commodity sector gains momentum again. (Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2017) A growth in the resource

sector would imply that some of the imbalances in the GDP resulting from regional imbalances

would lower i.e growth in states like Queensland and Western Australia may pick up pace. In the

next few years the Reserve Bank of Australia also expects the ageing population to cause a

decrease in the spare capacity of labour in the domestic economy. (Reserve Bank of Australia,

2016) Further forecasts assume that domestic consumption is likely to remain high. Arise in the

minimum wage according under the Fair Wages Act would help this decision (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

One of the key components of consumption in the domestic economy is the housing sector and it

could be cause of concern in the near future. The activity in the housing sector currently is high

with a large number of pipeline projects in the near future. This could translate into the

development in the excess capacity of housing, a phenomenon that the Reserve Bank of

Australia has brought up time and again. The development of excess capacity in the housing

market may, in the near future, subdue the construction activity as well as lead to a downward

pressure in the housing prices. This, in turn, will lead to a lower inflation i.e. it is expected that

the housing market will not remain a significant contributor to the GDP (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017)

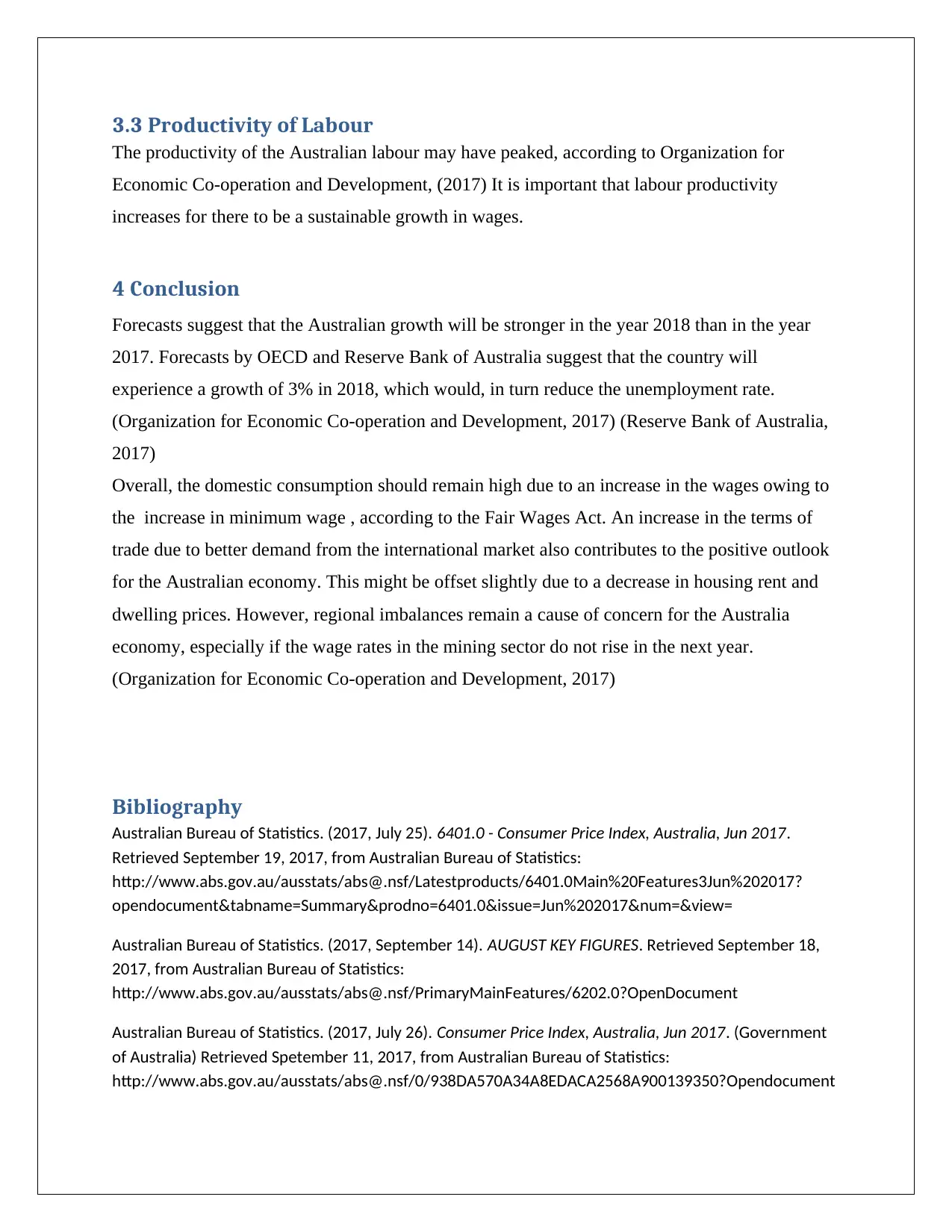

3.2 Uncertainty in the International Economy (Especially the Chinese

Economy)

The increase in demand for mining commodities and merchandise trade in the international

market, leading to a growth in the general price level of tradeable commodities, leading to a new

cycle of job growths in the mining sector, demand for housing (rental as well as dwelling

ownership) and a general increase in the price level, especially in regions that are pre-dominantly

dependent on the resources sector.

Reserve Bank of Australia expects the consumption in advanced economies to remain higher and

consequently expects the Terms of Trade of Australia to remain high during this period. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017) The RBA, also, expects that inflationary pressures the global market

will lead to an increase in the price of resources which in turn could increase Australia’s terms of

trade in the future. The

Among emerging economies, especially China, the demand for commodities such as coal and

iron ore is expected to remain high. The situation in the Chinese economy is expected to affect

the Australian economy as it affects the terms of trade and exports of the country and the

uncertainty in Chinese economy is a cause of concern for the Australian economy. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017)

could be cause of concern in the near future. The activity in the housing sector currently is high

with a large number of pipeline projects in the near future. This could translate into the

development in the excess capacity of housing, a phenomenon that the Reserve Bank of

Australia has brought up time and again. The development of excess capacity in the housing

market may, in the near future, subdue the construction activity as well as lead to a downward

pressure in the housing prices. This, in turn, will lead to a lower inflation i.e. it is expected that

the housing market will not remain a significant contributor to the GDP (Reserve Bank of

Australia, 2017)

3.2 Uncertainty in the International Economy (Especially the Chinese

Economy)

The increase in demand for mining commodities and merchandise trade in the international

market, leading to a growth in the general price level of tradeable commodities, leading to a new

cycle of job growths in the mining sector, demand for housing (rental as well as dwelling

ownership) and a general increase in the price level, especially in regions that are pre-dominantly

dependent on the resources sector.

Reserve Bank of Australia expects the consumption in advanced economies to remain higher and

consequently expects the Terms of Trade of Australia to remain high during this period. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017) The RBA, also, expects that inflationary pressures the global market

will lead to an increase in the price of resources which in turn could increase Australia’s terms of

trade in the future. The

Among emerging economies, especially China, the demand for commodities such as coal and

iron ore is expected to remain high. The situation in the Chinese economy is expected to affect

the Australian economy as it affects the terms of trade and exports of the country and the

uncertainty in Chinese economy is a cause of concern for the Australian economy. (Reserve

Bank of Australia, 2017)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3.3 Productivity of Labour

The productivity of the Australian labour may have peaked, according to Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development, (2017) It is important that labour productivity

increases for there to be a sustainable growth in wages.

4 Conclusion

Forecasts suggest that the Australian growth will be stronger in the year 2018 than in the year

2017. Forecasts by OECD and Reserve Bank of Australia suggest that the country will

experience a growth of 3% in 2018, which would, in turn reduce the unemployment rate.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia,

2017)

Overall, the domestic consumption should remain high due to an increase in the wages owing to

the increase in minimum wage , according to the Fair Wages Act. An increase in the terms of

trade due to better demand from the international market also contributes to the positive outlook

for the Australian economy. This might be offset slightly due to a decrease in housing rent and

dwelling prices. However, regional imbalances remain a cause of concern for the Australia

economy, especially if the wage rates in the mining sector do not rise in the next year.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017)

Bibliography

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, July 25). 6401.0 - Consumer Price Index, Australia, Jun 2017.

Retrieved September 19, 2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/6401.0Main%20Features3Jun%202017?

opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=6401.0&issue=Jun%202017&num=&view=

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, September 14). AUGUST KEY FIGURES. Retrieved September 18,

2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/6202.0?OpenDocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, July 26). Consumer Price Index, Australia, Jun 2017. (Government

of Australia) Retrieved Spetember 11, 2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/938DA570A34A8EDACA2568A900139350?Opendocument

The productivity of the Australian labour may have peaked, according to Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development, (2017) It is important that labour productivity

increases for there to be a sustainable growth in wages.

4 Conclusion

Forecasts suggest that the Australian growth will be stronger in the year 2018 than in the year

2017. Forecasts by OECD and Reserve Bank of Australia suggest that the country will

experience a growth of 3% in 2018, which would, in turn reduce the unemployment rate.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017) (Reserve Bank of Australia,

2017)

Overall, the domestic consumption should remain high due to an increase in the wages owing to

the increase in minimum wage , according to the Fair Wages Act. An increase in the terms of

trade due to better demand from the international market also contributes to the positive outlook

for the Australian economy. This might be offset slightly due to a decrease in housing rent and

dwelling prices. However, regional imbalances remain a cause of concern for the Australia

economy, especially if the wage rates in the mining sector do not rise in the next year.

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017)

Bibliography

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, July 25). 6401.0 - Consumer Price Index, Australia, Jun 2017.

Retrieved September 19, 2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/6401.0Main%20Features3Jun%202017?

opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=6401.0&issue=Jun%202017&num=&view=

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, September 14). AUGUST KEY FIGURES. Retrieved September 18,

2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/6202.0?OpenDocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, July 26). Consumer Price Index, Australia, Jun 2017. (Government

of Australia) Retrieved Spetember 11, 2017, from Australian Bureau of Statistics:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/938DA570A34A8EDACA2568A900139350?Opendocument

Gittins, R. (2017, April 8). Australia has $1 trillion foreign debt. Should we be worried? . Retrieved

September 19, 2017, from The Sydney Morning Herald: http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-

economy/australias-1-trillion-foreign-debt-level-should-worry-us-all-20170407-gvfsqq.html

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). 2017 Economic Survey of Australia.

Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Inflation Target. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of

Australia: http://www.rba.gov.au/inflation/inflation-target.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, August). Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2017 Box A The

Recent Pick-up in Global Merchandise Trade . Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of

Australia: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2017/aug/box-a-the-recent-pick-up-in-global-

merchandise-trade.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, August). Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2017 Box C Minimum

Wage Decision. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of Australia:

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2017/aug/box-c-minimum-wage-decision.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2016, November). Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2016.

Retrieved September 18, 2017, from Reserve Bank of Australia:

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2016/nov/economic-outlook.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Statement on Monetary Policy August 2017. Melbourne: Reserve Bank

of Australia.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Statement on Monetary Policy, February 2017. Melbourne: Reserve

Bank of Australia.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, July 27). Statistical Tables. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from

Reserve Bank of Australia: http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade . (2017). Composition of Trade Australia 2016. Melbourne:

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade , Australian Government.

Thirlwell, M. (2017, June 23). Australia’s shrinking current account deficit. Retrieved Spetember 19,

2017, from Australian Trade and Investment Commission:

https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-shrinking-current-account-deficit

September 19, 2017, from The Sydney Morning Herald: http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-

economy/australias-1-trillion-foreign-debt-level-should-worry-us-all-20170407-gvfsqq.html

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). 2017 Economic Survey of Australia.

Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Inflation Target. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of

Australia: http://www.rba.gov.au/inflation/inflation-target.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, August). Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2017 Box A The

Recent Pick-up in Global Merchandise Trade . Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of

Australia: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2017/aug/box-a-the-recent-pick-up-in-global-

merchandise-trade.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, August). Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2017 Box C Minimum

Wage Decision. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from Reserve Bank of Australia:

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2017/aug/box-c-minimum-wage-decision.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2016, November). Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2016.

Retrieved September 18, 2017, from Reserve Bank of Australia:

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2016/nov/economic-outlook.html

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Statement on Monetary Policy August 2017. Melbourne: Reserve Bank

of Australia.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Statement on Monetary Policy, February 2017. Melbourne: Reserve

Bank of Australia.

Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017, July 27). Statistical Tables. Retrieved September 11, 2017, from

Reserve Bank of Australia: http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade . (2017). Composition of Trade Australia 2016. Melbourne:

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade , Australian Government.

Thirlwell, M. (2017, June 23). Australia’s shrinking current account deficit. Retrieved Spetember 19,

2017, from Australian Trade and Investment Commission:

https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-shrinking-current-account-deficit

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.