Bacterial Meningitis: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis and Treatment

VerifiedAdded on 2021/05/31

|3

|1845

|435

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a detailed analysis of bacterial meningitis, focusing on its various aspects. It begins by outlining the risk factors associated with the infection in children, such as day care attendance, family history of H. influenzae infection, lack of vaccination, and underlying health conditions. The report then delves into the aetiology, highlighting both congenital and acquired conditions, including chronic infections, immunodeficiencies, and anatomical abnormalities. The common microorganisms responsible, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, are also discussed. The pathophysiology section explains how bacteria spread to the central nervous system, leading to inflammation, increased intracranial pressure, and neurological damage. Clinical manifestations, including fever, headache, and seizures, are described, along with diagnostic tests like CT scans, MRI, cell cultures, and blood tests. The treatment section emphasizes the need for immediate antimicrobial therapy, hydration, and ICP medication, as well as the role of nursing in assessment, monitoring, and patient education, including the importance of vaccination. The report concludes with a comprehensive list of references supporting the information presented.

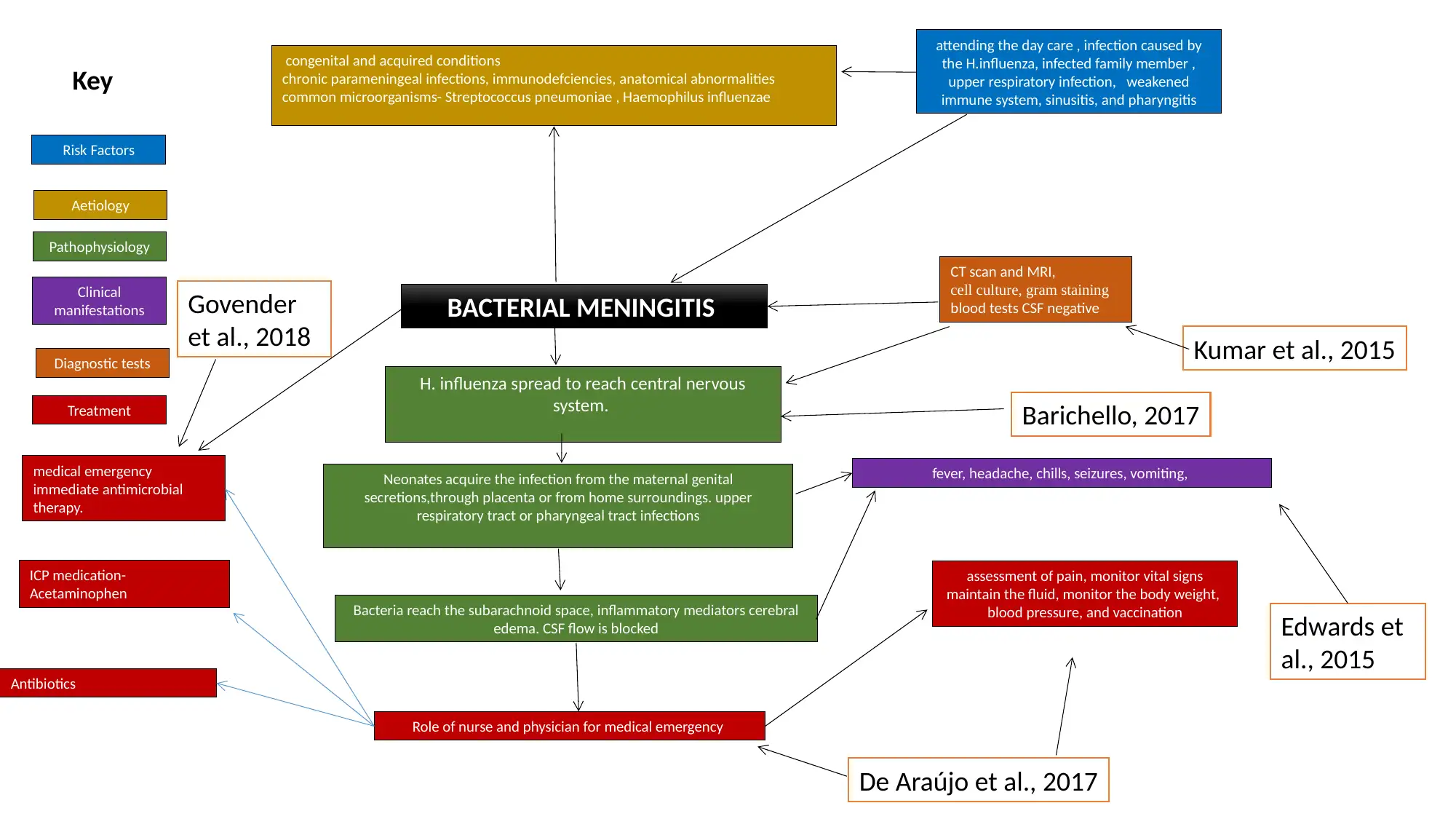

Risk Factors

Aetiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical

manifestations

Diagnostic tests

Treatment

Key

BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

H. influenza spread to reach central nervous

system.

congenital and acquired conditions

chronic parameningeal infections, immunodefciencies, anatomical abnormalities

common microorganisms- Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae

Neonates acquire the infection from the maternal genital

secretions,through placenta or from home surroundings. upper

respiratory tract or pharyngeal tract infections

Bacteria reach the subarachnoid space, inflammatory mediators cerebral

edema. CSF flow is blocked

fever, headache, chills, seizures, vomiting,

attending the day care , infection caused by

the H.influenza, infected family member ,

upper respiratory infection, weakened

immune system, sinusitis, and pharyngitis

CT scan and MRI,

cell culture, gram staining

blood tests CSF negative

medical emergency

immediate antimicrobial

therapy.

Role of nurse and physician for medical emergency

ICP medication-

Acetaminophen

Antibiotics

assessment of pain, monitor vital signs

maintain the fluid, monitor the body weight,

blood pressure, and vaccination

Kumar et al., 2015

De Araújo et al., 2017

Govender

et al., 2018

Edwards et

al., 2015

Barichello, 2017

Aetiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical

manifestations

Diagnostic tests

Treatment

Key

BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

H. influenza spread to reach central nervous

system.

congenital and acquired conditions

chronic parameningeal infections, immunodefciencies, anatomical abnormalities

common microorganisms- Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae

Neonates acquire the infection from the maternal genital

secretions,through placenta or from home surroundings. upper

respiratory tract or pharyngeal tract infections

Bacteria reach the subarachnoid space, inflammatory mediators cerebral

edema. CSF flow is blocked

fever, headache, chills, seizures, vomiting,

attending the day care , infection caused by

the H.influenza, infected family member ,

upper respiratory infection, weakened

immune system, sinusitis, and pharyngitis

CT scan and MRI,

cell culture, gram staining

blood tests CSF negative

medical emergency

immediate antimicrobial

therapy.

Role of nurse and physician for medical emergency

ICP medication-

Acetaminophen

Antibiotics

assessment of pain, monitor vital signs

maintain the fluid, monitor the body weight,

blood pressure, and vaccination

Kumar et al., 2015

De Araújo et al., 2017

Govender

et al., 2018

Edwards et

al., 2015

Barichello, 2017

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Explanation

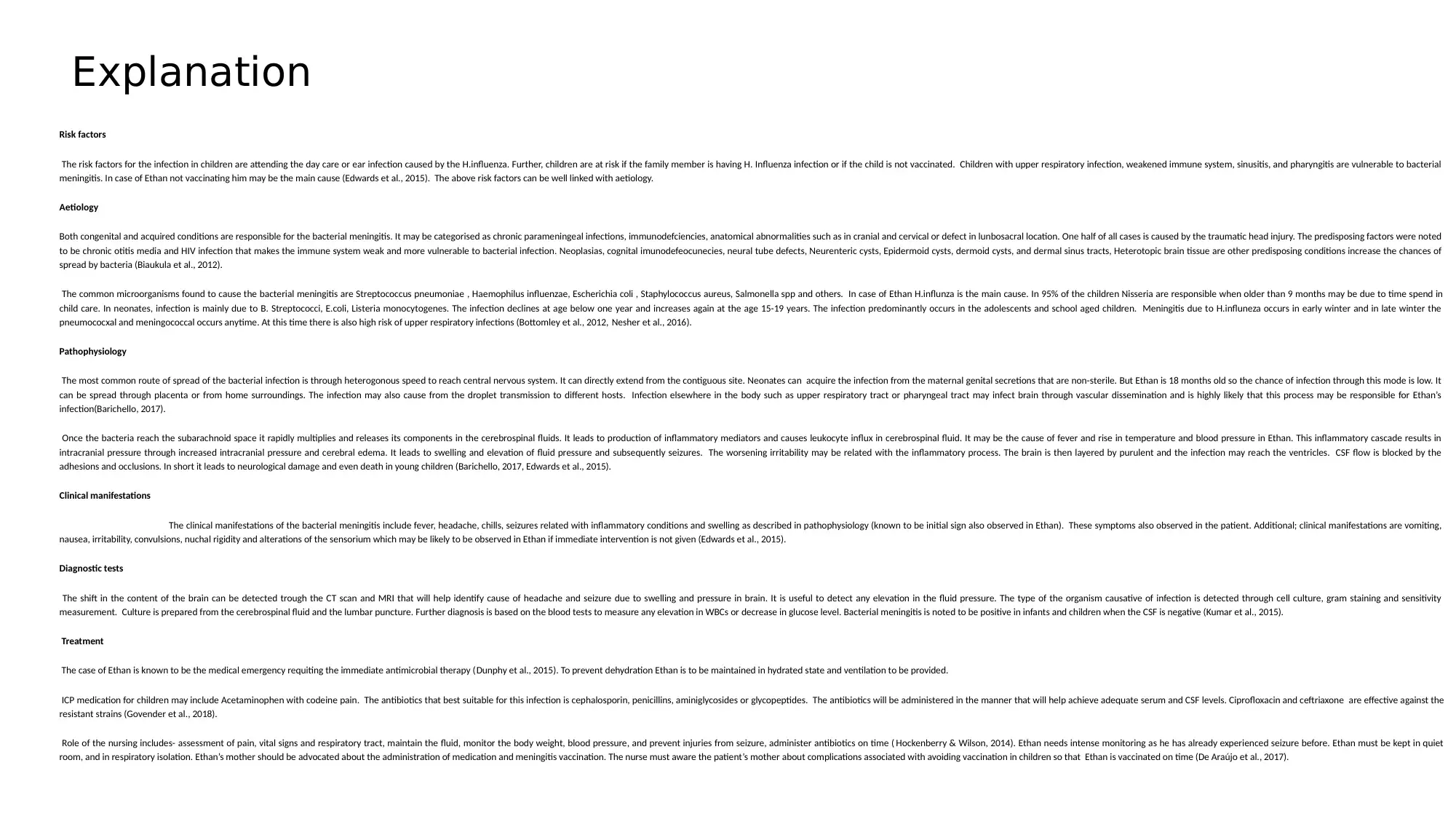

Risk factors

The risk factors for the infection in children are attending the day care or ear infection caused by the H.influenza. Further, children are at risk if the family member is having H. Influenza infection or if the child is not vaccinated. Children with upper respiratory infection, weakened immune system, sinusitis, and pharyngitis are vulnerable to bacterial

meningitis. In case of Ethan not vaccinating him may be the main cause (Edwards et al., 2015). The above risk factors can be well linked with aetiology.

Aetiology

Both congenital and acquired conditions are responsible for the bacterial meningitis. It may be categorised as chronic parameningeal infections, immunodefciencies, anatomical abnormalities such as in cranial and cervical or defect in lunbosacral location. One half of all cases is caused by the traumatic head injury. The predisposing factors were noted

to be chronic otitis media and HIV infection that makes the immune system weak and more vulnerable to bacterial infection. Neoplasias, cognital imunodefeocunecies, neural tube defects, Neurenteric cysts, Epidermoid cysts, dermoid cysts, and dermal sinus tracts, Heterotopic brain tissue are other predisposing conditions increase the chances of

spread by bacteria (Biaukula et al., 2012).

The common microorganisms found to cause the bacterial meningitis are Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli , Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp and others. In case of Ethan H.influnza is the main cause. In 95% of the children Nisseria are responsible when older than 9 months may be due to time spend in

child care. In neonates, infection is mainly due to B. Streptococci, E.coli, Listeria monocytogenes. The infection declines at age below one year and increases again at the age 15-19 years. The infection predominantly occurs in the adolescents and school aged children. Meningitis due to H.influneza occurs in early winter and in late winter the

pneumococxal and meningococcal occurs anytime. At this time there is also high risk of upper respiratory infections (Bottomley et al., 2012, Nesher et al., 2016).

Pathophysiology

The most common route of spread of the bacterial infection is through heterogonous speed to reach central nervous system. It can directly extend from the contiguous site. Neonates can acquire the infection from the maternal genital secretions that are non-sterile. But Ethan is 18 months old so the chance of infection through this mode is low. It

can be spread through placenta or from home surroundings. The infection may also cause from the droplet transmission to different hosts. Infection elsewhere in the body such as upper respiratory tract or pharyngeal tract may infect brain through vascular dissemination and is highly likely that this process may be responsible for Ethan’s

infection(Barichello, 2017).

Once the bacteria reach the subarachnoid space it rapidly multiplies and releases its components in the cerebrospinal fluids. It leads to production of inflammatory mediators and causes leukocyte influx in cerebrospinal fluid. It may be the cause of fever and rise in temperature and blood pressure in Ethan. This inflammatory cascade results in

intracranial pressure through increased intracranial pressure and cerebral edema. It leads to swelling and elevation of fluid pressure and subsequently seizures. The worsening irritability may be related with the inflammatory process. The brain is then layered by purulent and the infection may reach the ventricles. CSF flow is blocked by the

adhesions and occlusions. In short it leads to neurological damage and even death in young children (Barichello, 2017, Edwards et al., 2015).

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of the bacterial meningitis include fever, headache, chills, seizures related with inflammatory conditions and swelling as described in pathophysiology (known to be initial sign also observed in Ethan). These symptoms also observed in the patient. Additional; clinical manifestations are vomiting,

nausea, irritability, convulsions, nuchal rigidity and alterations of the sensorium which may be likely to be observed in Ethan if immediate intervention is not given (Edwards et al., 2015).

Diagnostic tests

The shift in the content of the brain can be detected trough the CT scan and MRI that will help identify cause of headache and seizure due to swelling and pressure in brain. It is useful to detect any elevation in the fluid pressure. The type of the organism causative of infection is detected through cell culture, gram staining and sensitivity

measurement. Culture is prepared from the cerebrospinal fluid and the lumbar puncture. Further diagnosis is based on the blood tests to measure any elevation in WBCs or decrease in glucose level. Bacterial meningitis is noted to be positive in infants and children when the CSF is negative (Kumar et al., 2015).

Treatment

The case of Ethan is known to be the medical emergency requiting the immediate antimicrobial therapy (Dunphy et al., 2015). To prevent dehydration Ethan is to be maintained in hydrated state and ventilation to be provided.

ICP medication for children may include Acetaminophen with codeine pain. The antibiotics that best suitable for this infection is cephalosporin, penicillins, aminiglycosides or glycopeptides. The antibiotics will be administered in the manner that will help achieve adequate serum and CSF levels. Ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone are effective against the

resistant strains (Govender et al., 2018).

Role of the nursing includes- assessment of pain, vital signs and respiratory tract, maintain the fluid, monitor the body weight, blood pressure, and prevent injuries from seizure, administer antibiotics on time ( Hockenberry & Wilson, 2014). Ethan needs intense monitoring as he has already experienced seizure before. Ethan must be kept in quiet

room, and in respiratory isolation. Ethan’s mother should be advocated about the administration of medication and meningitis vaccination. The nurse must aware the patient’s mother about complications associated with avoiding vaccination in children so that Ethan is vaccinated on time (De Araújo et al., 2017).

Risk factors

The risk factors for the infection in children are attending the day care or ear infection caused by the H.influenza. Further, children are at risk if the family member is having H. Influenza infection or if the child is not vaccinated. Children with upper respiratory infection, weakened immune system, sinusitis, and pharyngitis are vulnerable to bacterial

meningitis. In case of Ethan not vaccinating him may be the main cause (Edwards et al., 2015). The above risk factors can be well linked with aetiology.

Aetiology

Both congenital and acquired conditions are responsible for the bacterial meningitis. It may be categorised as chronic parameningeal infections, immunodefciencies, anatomical abnormalities such as in cranial and cervical or defect in lunbosacral location. One half of all cases is caused by the traumatic head injury. The predisposing factors were noted

to be chronic otitis media and HIV infection that makes the immune system weak and more vulnerable to bacterial infection. Neoplasias, cognital imunodefeocunecies, neural tube defects, Neurenteric cysts, Epidermoid cysts, dermoid cysts, and dermal sinus tracts, Heterotopic brain tissue are other predisposing conditions increase the chances of

spread by bacteria (Biaukula et al., 2012).

The common microorganisms found to cause the bacterial meningitis are Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli , Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp and others. In case of Ethan H.influnza is the main cause. In 95% of the children Nisseria are responsible when older than 9 months may be due to time spend in

child care. In neonates, infection is mainly due to B. Streptococci, E.coli, Listeria monocytogenes. The infection declines at age below one year and increases again at the age 15-19 years. The infection predominantly occurs in the adolescents and school aged children. Meningitis due to H.influneza occurs in early winter and in late winter the

pneumococxal and meningococcal occurs anytime. At this time there is also high risk of upper respiratory infections (Bottomley et al., 2012, Nesher et al., 2016).

Pathophysiology

The most common route of spread of the bacterial infection is through heterogonous speed to reach central nervous system. It can directly extend from the contiguous site. Neonates can acquire the infection from the maternal genital secretions that are non-sterile. But Ethan is 18 months old so the chance of infection through this mode is low. It

can be spread through placenta or from home surroundings. The infection may also cause from the droplet transmission to different hosts. Infection elsewhere in the body such as upper respiratory tract or pharyngeal tract may infect brain through vascular dissemination and is highly likely that this process may be responsible for Ethan’s

infection(Barichello, 2017).

Once the bacteria reach the subarachnoid space it rapidly multiplies and releases its components in the cerebrospinal fluids. It leads to production of inflammatory mediators and causes leukocyte influx in cerebrospinal fluid. It may be the cause of fever and rise in temperature and blood pressure in Ethan. This inflammatory cascade results in

intracranial pressure through increased intracranial pressure and cerebral edema. It leads to swelling and elevation of fluid pressure and subsequently seizures. The worsening irritability may be related with the inflammatory process. The brain is then layered by purulent and the infection may reach the ventricles. CSF flow is blocked by the

adhesions and occlusions. In short it leads to neurological damage and even death in young children (Barichello, 2017, Edwards et al., 2015).

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of the bacterial meningitis include fever, headache, chills, seizures related with inflammatory conditions and swelling as described in pathophysiology (known to be initial sign also observed in Ethan). These symptoms also observed in the patient. Additional; clinical manifestations are vomiting,

nausea, irritability, convulsions, nuchal rigidity and alterations of the sensorium which may be likely to be observed in Ethan if immediate intervention is not given (Edwards et al., 2015).

Diagnostic tests

The shift in the content of the brain can be detected trough the CT scan and MRI that will help identify cause of headache and seizure due to swelling and pressure in brain. It is useful to detect any elevation in the fluid pressure. The type of the organism causative of infection is detected through cell culture, gram staining and sensitivity

measurement. Culture is prepared from the cerebrospinal fluid and the lumbar puncture. Further diagnosis is based on the blood tests to measure any elevation in WBCs or decrease in glucose level. Bacterial meningitis is noted to be positive in infants and children when the CSF is negative (Kumar et al., 2015).

Treatment

The case of Ethan is known to be the medical emergency requiting the immediate antimicrobial therapy (Dunphy et al., 2015). To prevent dehydration Ethan is to be maintained in hydrated state and ventilation to be provided.

ICP medication for children may include Acetaminophen with codeine pain. The antibiotics that best suitable for this infection is cephalosporin, penicillins, aminiglycosides or glycopeptides. The antibiotics will be administered in the manner that will help achieve adequate serum and CSF levels. Ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone are effective against the

resistant strains (Govender et al., 2018).

Role of the nursing includes- assessment of pain, vital signs and respiratory tract, maintain the fluid, monitor the body weight, blood pressure, and prevent injuries from seizure, administer antibiotics on time ( Hockenberry & Wilson, 2014). Ethan needs intense monitoring as he has already experienced seizure before. Ethan must be kept in quiet

room, and in respiratory isolation. Ethan’s mother should be advocated about the administration of medication and meningitis vaccination. The nurse must aware the patient’s mother about complications associated with avoiding vaccination in children so that Ethan is vaccinated on time (De Araújo et al., 2017).

Reference list

Bichello, T. (2017). Pathophysiology of Neonatal Bacterial Meningitis. In Fetal and Neonatal Physiology (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1703-1712).

Biaukula, V. L., Tikoduadua, L., Azzopardi, K., Seduadua, A., Temple, B., Richmond, P., ... & Russell, F. M. (2012). Meningitis in children in Fiji: etiology, epidemiology, and neurological

sequelae. International journal of infectious diseases, 16(4), e289-e295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.013

Bottomley, M. J., Serruto, D., Sáfadi, M. A. P., & Klugman, K. P. (2012). Future challenges in the elimination of bacterial meningitis. Vaccine, 30, B78-B86. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.099

De Araújo, A. B. R., Oliveira, R. S., Torres, F. Q., Siqueira, J. E., & Lopes, J. R. (2017). Combined therapy of pediatric bacterial meningitis with the use of corticosteroids and antibacterials: a

bibliographical review. Unimontes Científica, 248-252.

Dunphy, L. M., Winland-Brown, J., Porter, B., & Thomas, D. (2015). Primary care: Art and science of advanced practice nursing. FA Davis. Retrieved from:

https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fsnXBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=meningitis+treatment+and+nursing+care&ots=OMY3ru6rrl&sig=0Xp-6YoTyPHYVx4LnBWezkWe_Mo#v=onep

age&q=meningitis%20treatment%20and%20nursing%20care&f=false

Edwards, M. S., Baker, C. J., Kaplan, S. L., Weisman, L. E., & Armsby, C. (2015). Bacterial meningitis in the neonate: clinical features and diagnosis. inUpToDate, TW Post, Ed., UpToDate, Waltham,

Mass, USA. Retrieved from:https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-meningitis-in-the-neonate-clinical-features-and-diagnosis#H3

Hockenberry, M. J., & Wilson, D. (2014). Wong's nursing care of infants and children-E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. Retrieved from: https://books.google.co.in/books?

hl=en&lr=&id=z_okCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=meningitis+treatment+and+nursing+care&ots=rt7n45UUum&sig=Exp4giMLU51JqvEOMsOq_NspQ4c#v=onepage&q=meningitis%20treatment

%20and%20nursing%20care&f=false

Govender, I., Steyn, C., Maricowitz, G., Clark, C. C., & Tjale, M. C. (2018). A primary care physician’s approach to a child with meningitis. Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases, 33(2), 31-37.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23120053.2017.1394610

Kumar, A., Debata, P. K., Ranjan, A., & Gaind, R. (2015). The role and reliability of rapid bedside diagnostic test in early diagnosis and treatment of bacterial meningitis. The Indian Journal of

Pediatrics, 82(4), 311-314. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-014-1357-z

Nesher, L., Hadi, C. M., Salazar, L., Wootton, S. H., Garey, K. W., Lasco, T., ... & Hasbun, R. (2016). Epidemiology of meningitis with a negative CSF Gram

stain: under-utilization of available diagnostic tests. Epidemiology & Infection, 144(1), 189-197. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815000850

Bichello, T. (2017). Pathophysiology of Neonatal Bacterial Meningitis. In Fetal and Neonatal Physiology (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1703-1712).

Biaukula, V. L., Tikoduadua, L., Azzopardi, K., Seduadua, A., Temple, B., Richmond, P., ... & Russell, F. M. (2012). Meningitis in children in Fiji: etiology, epidemiology, and neurological

sequelae. International journal of infectious diseases, 16(4), e289-e295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.013

Bottomley, M. J., Serruto, D., Sáfadi, M. A. P., & Klugman, K. P. (2012). Future challenges in the elimination of bacterial meningitis. Vaccine, 30, B78-B86. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.099

De Araújo, A. B. R., Oliveira, R. S., Torres, F. Q., Siqueira, J. E., & Lopes, J. R. (2017). Combined therapy of pediatric bacterial meningitis with the use of corticosteroids and antibacterials: a

bibliographical review. Unimontes Científica, 248-252.

Dunphy, L. M., Winland-Brown, J., Porter, B., & Thomas, D. (2015). Primary care: Art and science of advanced practice nursing. FA Davis. Retrieved from:

https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fsnXBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=meningitis+treatment+and+nursing+care&ots=OMY3ru6rrl&sig=0Xp-6YoTyPHYVx4LnBWezkWe_Mo#v=onep

age&q=meningitis%20treatment%20and%20nursing%20care&f=false

Edwards, M. S., Baker, C. J., Kaplan, S. L., Weisman, L. E., & Armsby, C. (2015). Bacterial meningitis in the neonate: clinical features and diagnosis. inUpToDate, TW Post, Ed., UpToDate, Waltham,

Mass, USA. Retrieved from:https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-meningitis-in-the-neonate-clinical-features-and-diagnosis#H3

Hockenberry, M. J., & Wilson, D. (2014). Wong's nursing care of infants and children-E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. Retrieved from: https://books.google.co.in/books?

hl=en&lr=&id=z_okCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=meningitis+treatment+and+nursing+care&ots=rt7n45UUum&sig=Exp4giMLU51JqvEOMsOq_NspQ4c#v=onepage&q=meningitis%20treatment

%20and%20nursing%20care&f=false

Govender, I., Steyn, C., Maricowitz, G., Clark, C. C., & Tjale, M. C. (2018). A primary care physician’s approach to a child with meningitis. Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases, 33(2), 31-37.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23120053.2017.1394610

Kumar, A., Debata, P. K., Ranjan, A., & Gaind, R. (2015). The role and reliability of rapid bedside diagnostic test in early diagnosis and treatment of bacterial meningitis. The Indian Journal of

Pediatrics, 82(4), 311-314. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-014-1357-z

Nesher, L., Hadi, C. M., Salazar, L., Wootton, S. H., Garey, K. W., Lasco, T., ... & Hasbun, R. (2016). Epidemiology of meningitis with a negative CSF Gram

stain: under-utilization of available diagnostic tests. Epidemiology & Infection, 144(1), 189-197. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815000850

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 3

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.