Post-Project Review of Bank1's Enterprise Architecture Implementation

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/22

|31

|12469

|345

Report

AI Summary

This assignment requires a business analyst to conduct a post-project review of Bank1's Enterprise Architecture Implementation (EAI). The analysis focuses on why the architects failed to secure stakeholder commitment and support for the EAI, utilizing the BABOK knowledge areas of enterprise analysis, elicitation, requirements analysis, and solution assessment and validation. The report examines the architects' perspectives, their interactions within the team, and their interactions with business and technology staff, highlighting the issues that led to the EAI's stalling. The tasks involve analyzing the root causes of the issues and proposing alternative strategies, referencing the BABOK knowledge areas, to ensure future stakeholder commitment and support for similar projects. The case study provides detailed insights into the organizational structure, the architects' roles, and the challenges faced during the EAI implementation, including the role of the Architecture Review Board (ARB) and the impact of the architects' practices on stakeholder engagement. The report is intended to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issues and propose actionable solutions for successful EAI implementation.

1

INF80014 CONTEMPORARY

ISSUES IN BUSIUNESS

ANALYSIS, S2 2021

ASSIGNMENT 1

INDIVIDUAL ASSIGNMENT

Assignment Submission and Weighting Details: See Unit Outline

Length:1,500 ± 10% words

ASSIGNMENT TASK

Please read the attached case study and complete the following 2 tasks

You are a business analyst and have been engaged by Bank1 to do a Post-Project review.

1) Applying the following Knowledge Areas of the BABOK (enterprise analysis,

elicitation, requirements analysis and solution assessment and validation), analyse why

the architects in Bank1 were unable to build stakeholder commitment and support for the

enterprise architecture implementation (EAI). 2) With reference to the above knowledge

areas, what would you do differently to ensure stakeholder commitment and support for

the EAI?

Please refer to the assignment rubric for additional information.

INF80014 CONTEMPORARY

ISSUES IN BUSIUNESS

ANALYSIS, S2 2021

ASSIGNMENT 1

INDIVIDUAL ASSIGNMENT

Assignment Submission and Weighting Details: See Unit Outline

Length:1,500 ± 10% words

ASSIGNMENT TASK

Please read the attached case study and complete the following 2 tasks

You are a business analyst and have been engaged by Bank1 to do a Post-Project review.

1) Applying the following Knowledge Areas of the BABOK (enterprise analysis,

elicitation, requirements analysis and solution assessment and validation), analyse why

the architects in Bank1 were unable to build stakeholder commitment and support for the

enterprise architecture implementation (EAI). 2) With reference to the above knowledge

areas, what would you do differently to ensure stakeholder commitment and support for

the EAI?

Please refer to the assignment rubric for additional information.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

BANK1 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

IMPLEMENTATION CASE STUDY

Introduction

• Background to the case: This includes information about the organization, its

operations and structure. Though it is important that the case studies be understood in

their wider organizational context, background information is presented in a way to

ensure that the identity of the organization and participants is not revealed.

• Information about the case study presentation

The discussion of results from the data analysis is presented in four themes. The first

theme, EAI work – the architect’s perspective, highlights the architects’ view of their

role in the EAI and how they conceptualize their implementation work. The second

theme: Practice work in the architecture team is focused on the nature of the interactions

amongst the architects and highlights the architect’s perspective on the EAI approach,

tools and documentation. The third theme, Framing EAI work – business and technology

staff’s perspective, highlights business and technology staff’s perceptions and

expectations of the implementation roles and practices of the architects. The fourth

theme, Interactions with business and technology staff, highlights the issues that reveal

the nature of the relationship between the architects, business and technology staff.

Case Study: Bank1

Bank1 has over 48,000 employees, operates in more than 30 different countries including

Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific, Europe, Dubai, United States of America and has

over eight million customers worldwide. At the beginning of 2011, the CEO of Bank1

BANK1 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

IMPLEMENTATION CASE STUDY

Introduction

• Background to the case: This includes information about the organization, its

operations and structure. Though it is important that the case studies be understood in

their wider organizational context, background information is presented in a way to

ensure that the identity of the organization and participants is not revealed.

• Information about the case study presentation

The discussion of results from the data analysis is presented in four themes. The first

theme, EAI work – the architect’s perspective, highlights the architects’ view of their

role in the EAI and how they conceptualize their implementation work. The second

theme: Practice work in the architecture team is focused on the nature of the interactions

amongst the architects and highlights the architect’s perspective on the EAI approach,

tools and documentation. The third theme, Framing EAI work – business and technology

staff’s perspective, highlights business and technology staff’s perceptions and

expectations of the implementation roles and practices of the architects. The fourth

theme, Interactions with business and technology staff, highlights the issues that reveal

the nature of the relationship between the architects, business and technology staff.

Case Study: Bank1

Bank1 has over 48,000 employees, operates in more than 30 different countries including

Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific, Europe, Dubai, United States of America and has

over eight million customers worldwide. At the beginning of 2011, the CEO of Bank1

3

announced a new five-year strategic plan that required radical change to the business

model and structure of the organization and would see it operating in new international

markets. Such a radical change had significant ramifications for the existing enterprise

architecture (EA). The organization was restructured from sixteen business units to four

business divisions with greater emphasis on international markets. Many of the

technology management and operational functions that supported the sixteen business

units were to be disbanded and many of the technology systems and environments they

managed and maintained were to be upgraded or decommissioned. Previously the

sixteen business units had operated independently, but under the new strategy there was

greater emphasis on common platforms, applications and data sharing.

Producing the EA Plans

After the announcement of the new strategy, the architects met several times over six

weeks with the executives of the business divisions to understand their requirements.

According to the Deputy CEO, who was involved in these meetings, the business

executives and architects discussed the business process, product and service

requirements of the different business divisions, and also their customer data and

information requirements. For the next four and half months (until June 2011), the

architects developed an integrated set of EA models that described the desired systems

and platforms, including the data, application, infrastructure, integration, storage and

security specifications required to support the business divisions. In June/ July of 2011,

the architects presented the EA plans to the senior executives of the various business

divisions who approved them.

Implementing the EA

After the approval of the EA plans, the architects were involved in two significant

activities. Firstly, they selected the new software and hardware products to build the

systems and platforms specified in the EA plans. This task, which began in June/ July

2011, was expected to finish by December 2011. In December 2011, the architects

presented the plans for the selected hardware and software products and the programs of

work to the senior executives of the business divisions for approval. However, these

executives were reluctant to commit to funding the hardware and software products and

the programs of work specified by the architects, and by the end of 2011 the

implementation of the EA had stalled.

announced a new five-year strategic plan that required radical change to the business

model and structure of the organization and would see it operating in new international

markets. Such a radical change had significant ramifications for the existing enterprise

architecture (EA). The organization was restructured from sixteen business units to four

business divisions with greater emphasis on international markets. Many of the

technology management and operational functions that supported the sixteen business

units were to be disbanded and many of the technology systems and environments they

managed and maintained were to be upgraded or decommissioned. Previously the

sixteen business units had operated independently, but under the new strategy there was

greater emphasis on common platforms, applications and data sharing.

Producing the EA Plans

After the announcement of the new strategy, the architects met several times over six

weeks with the executives of the business divisions to understand their requirements.

According to the Deputy CEO, who was involved in these meetings, the business

executives and architects discussed the business process, product and service

requirements of the different business divisions, and also their customer data and

information requirements. For the next four and half months (until June 2011), the

architects developed an integrated set of EA models that described the desired systems

and platforms, including the data, application, infrastructure, integration, storage and

security specifications required to support the business divisions. In June/ July of 2011,

the architects presented the EA plans to the senior executives of the various business

divisions who approved them.

Implementing the EA

After the approval of the EA plans, the architects were involved in two significant

activities. Firstly, they selected the new software and hardware products to build the

systems and platforms specified in the EA plans. This task, which began in June/ July

2011, was expected to finish by December 2011. In December 2011, the architects

presented the plans for the selected hardware and software products and the programs of

work to the senior executives of the business divisions for approval. However, these

executives were reluctant to commit to funding the hardware and software products and

the programs of work specified by the architects, and by the end of 2011 the

implementation of the EA had stalled.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

The second significant activity that the architects were involved with was the

Architecture Review Board (ARB). In June 2011, the CIO established the ARB to

review the hardware and software changes proposed by existing and new technology

projects at Bank1. Senior members of the architecture team staffed the ARB and the

ARB became an important approval step in the funding of technology projects at Bank1.

Approval from the ARB also gave projects access to critical implementation facilities

like the development, testing and production environments. Existing technology projects

that were already underway, as well new technology projects were required to submit

their proposed hardware and software changes to the ARB for approval. From its

inception, the architects used the ARB as an instrument to stabilize the technology

environment of Bank1, thus ensuring the relevance of the EA plans and the selected

technology products and implementation plans. The architects effectively used the ARB

to stop new technology projects from beginning and existing technology projects from

implementing.

The ARB lasted approximately twelve months from June 2011 until May/ June 2012.

The interviews for this research were conducted from January 2012 until June 2012, a

period when business and technology stakeholders’ frustrations with the ARB and the

practices of the architects were growing.

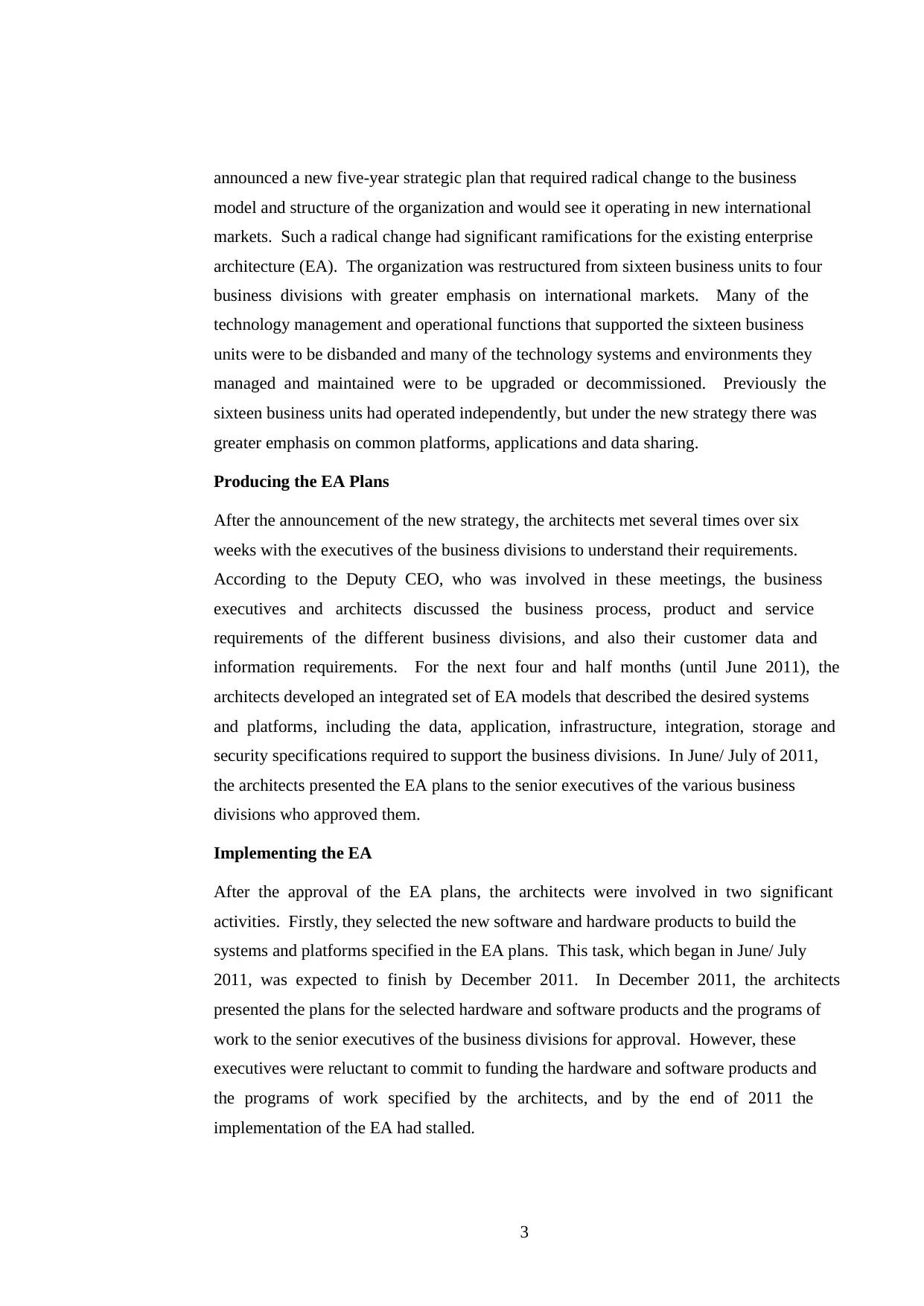

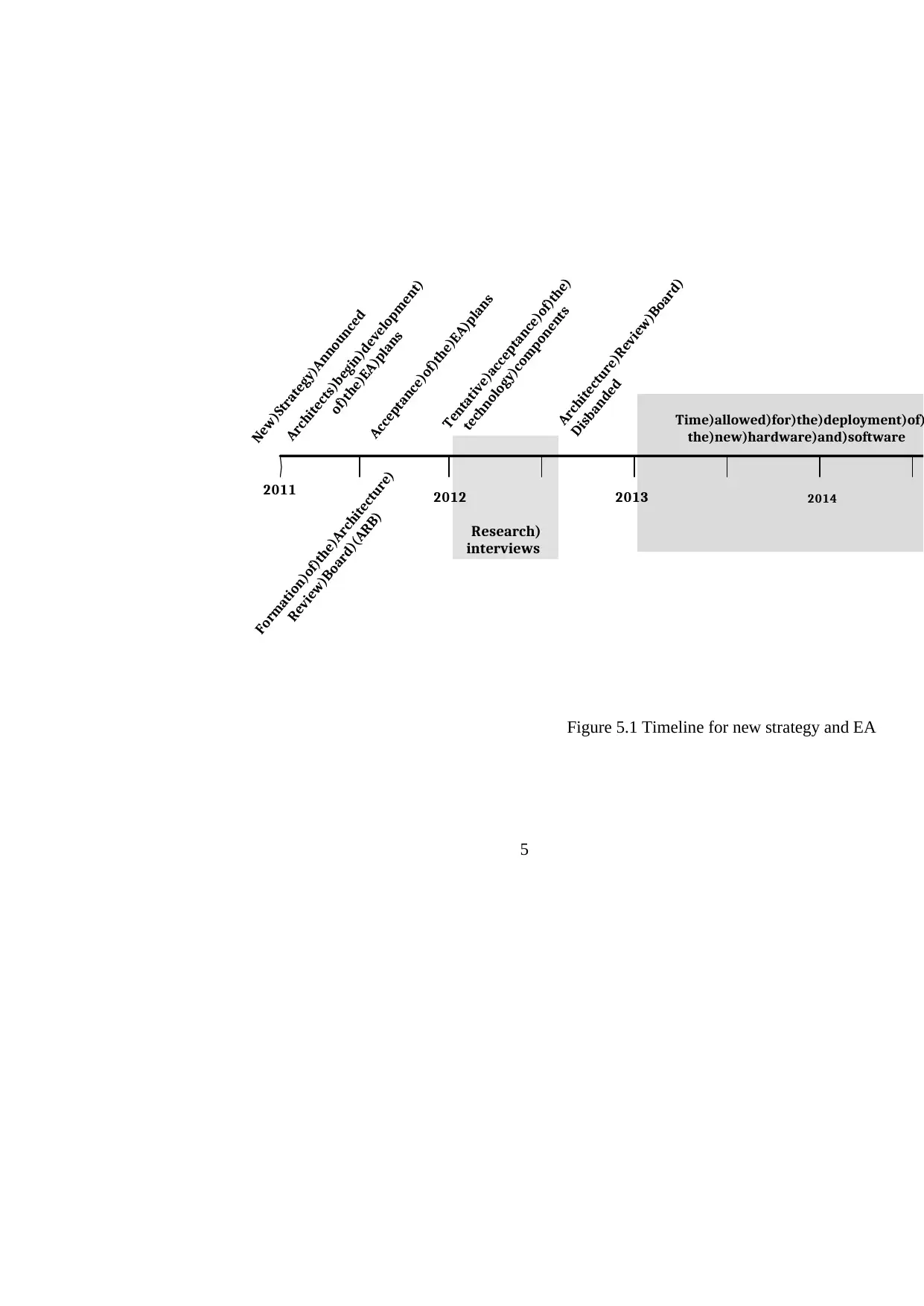

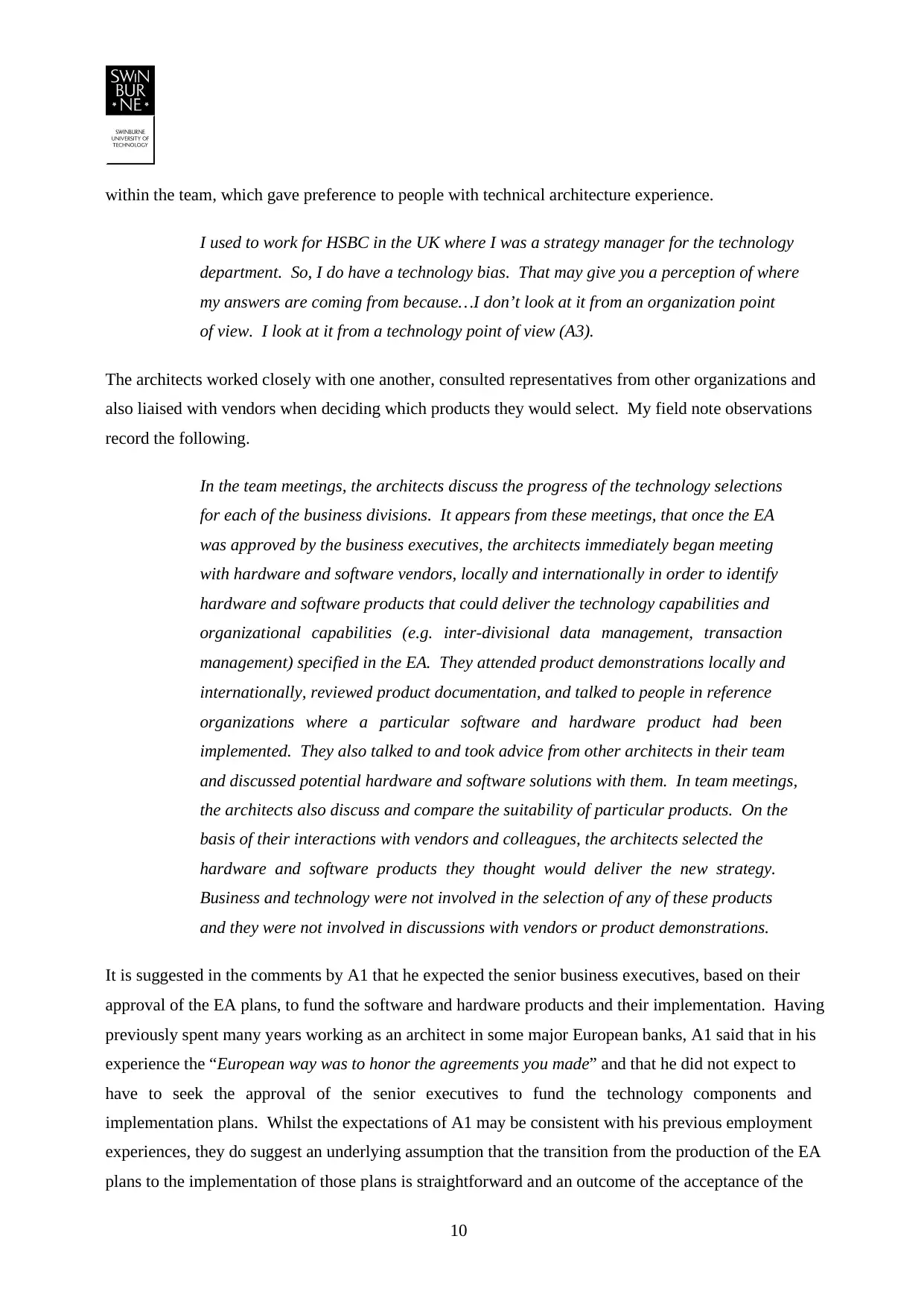

The following diagram (See Figure 5.1) provides a timeline of significant events from

the announcement of the new strategy up to the time when the new organizational

strategy was expected to deliver its forecast profits. The timeline also identifies the

period during which the research interviews were conducted.

The second significant activity that the architects were involved with was the

Architecture Review Board (ARB). In June 2011, the CIO established the ARB to

review the hardware and software changes proposed by existing and new technology

projects at Bank1. Senior members of the architecture team staffed the ARB and the

ARB became an important approval step in the funding of technology projects at Bank1.

Approval from the ARB also gave projects access to critical implementation facilities

like the development, testing and production environments. Existing technology projects

that were already underway, as well new technology projects were required to submit

their proposed hardware and software changes to the ARB for approval. From its

inception, the architects used the ARB as an instrument to stabilize the technology

environment of Bank1, thus ensuring the relevance of the EA plans and the selected

technology products and implementation plans. The architects effectively used the ARB

to stop new technology projects from beginning and existing technology projects from

implementing.

The ARB lasted approximately twelve months from June 2011 until May/ June 2012.

The interviews for this research were conducted from January 2012 until June 2012, a

period when business and technology stakeholders’ frustrations with the ARB and the

practices of the architects were growing.

The following diagram (See Figure 5.1) provides a timeline of significant events from

the announcement of the new strategy up to the time when the new organizational

strategy was expected to deliver its forecast profits. The timeline also identifies the

period during which the research interviews were conducted.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

Figure 5.1 Timeline for new strategy and EA

2011 2012 2013

New)Strategy)Announced

Formation)of)the)Architecture)

Review)Board)(ARB)

Architecture)Review)Board)

Disbanded

2014

Acceptance)of)the)EA)plans

Architects)begin)development)

of)the)EA)plans

Tentative)acceptance)of)the)

technology)components

Research)

interviews

Time)allowed)for)the)deployment)of)

the)new)hardware)and)software

Figure 5.1 Timeline for new strategy and EA

2011 2012 2013

New)Strategy)Announced

Formation)of)the)Architecture)

Review)Board)(ARB)

Architecture)Review)Board)

Disbanded

2014

Acceptance)of)the)EA)plans

Architects)begin)development)

of)the)EA)plans

Tentative)acceptance)of)the)

technology)components

Research)

interviews

Time)allowed)for)the)deployment)of)

the)new)hardware)and)software

6

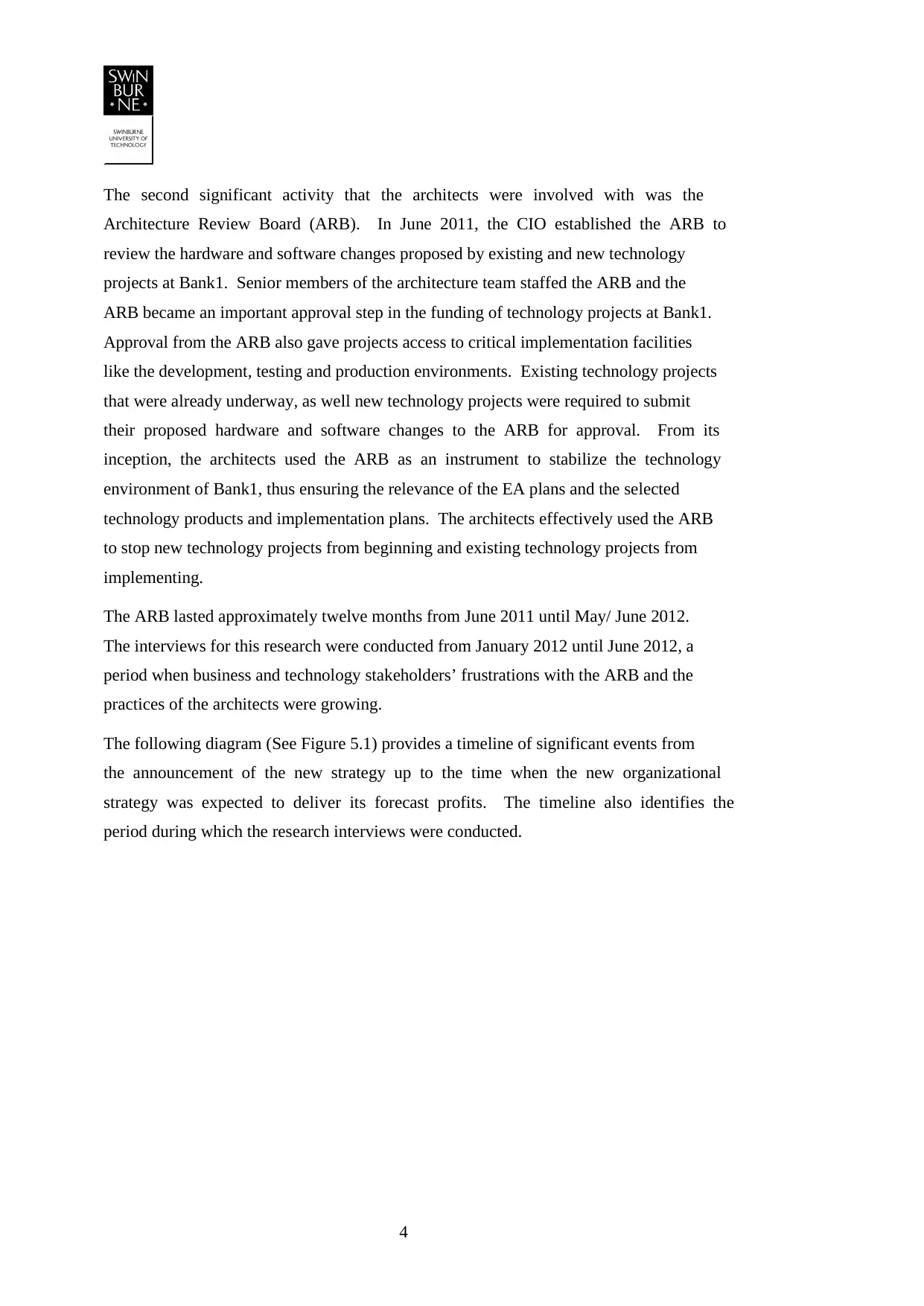

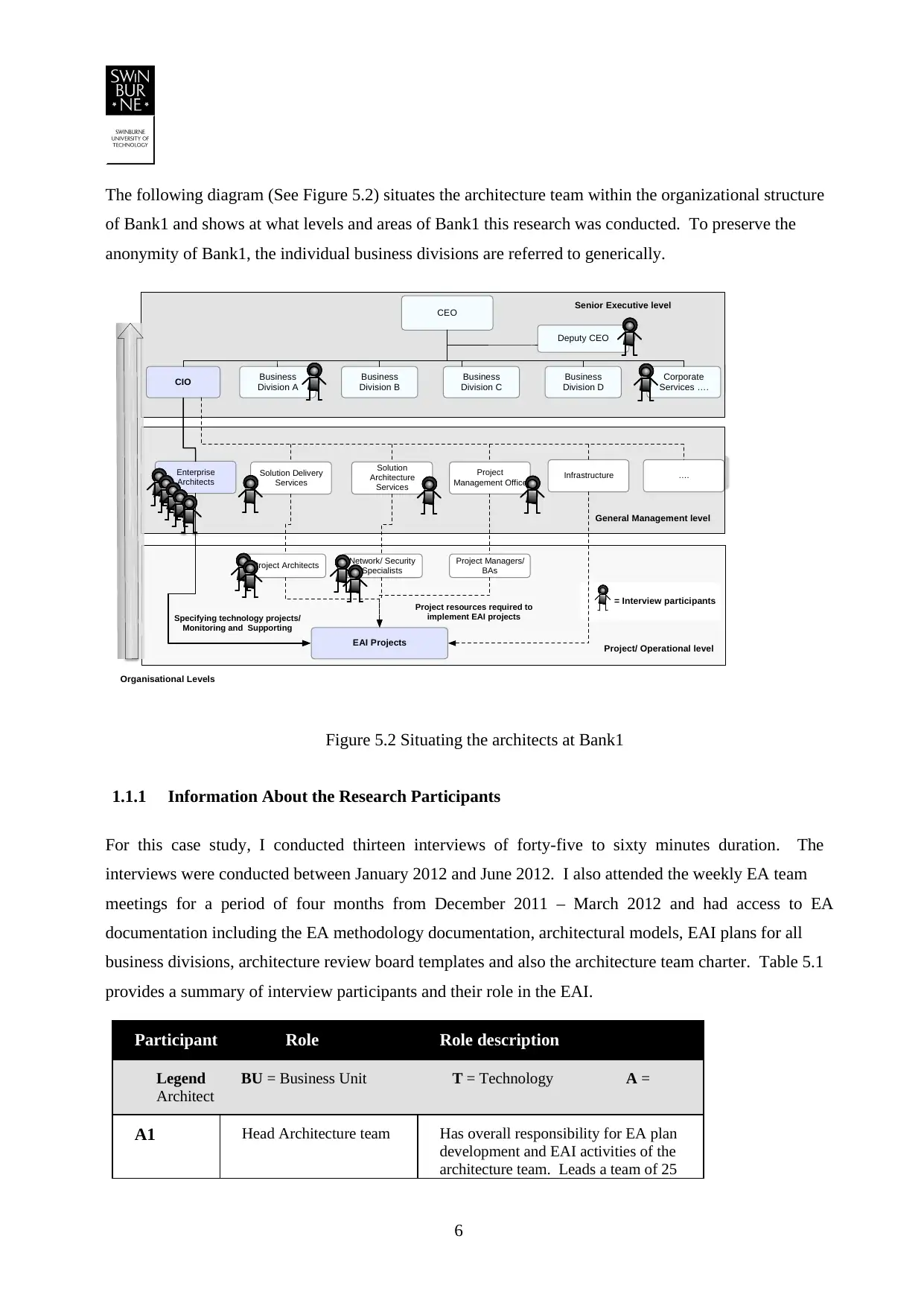

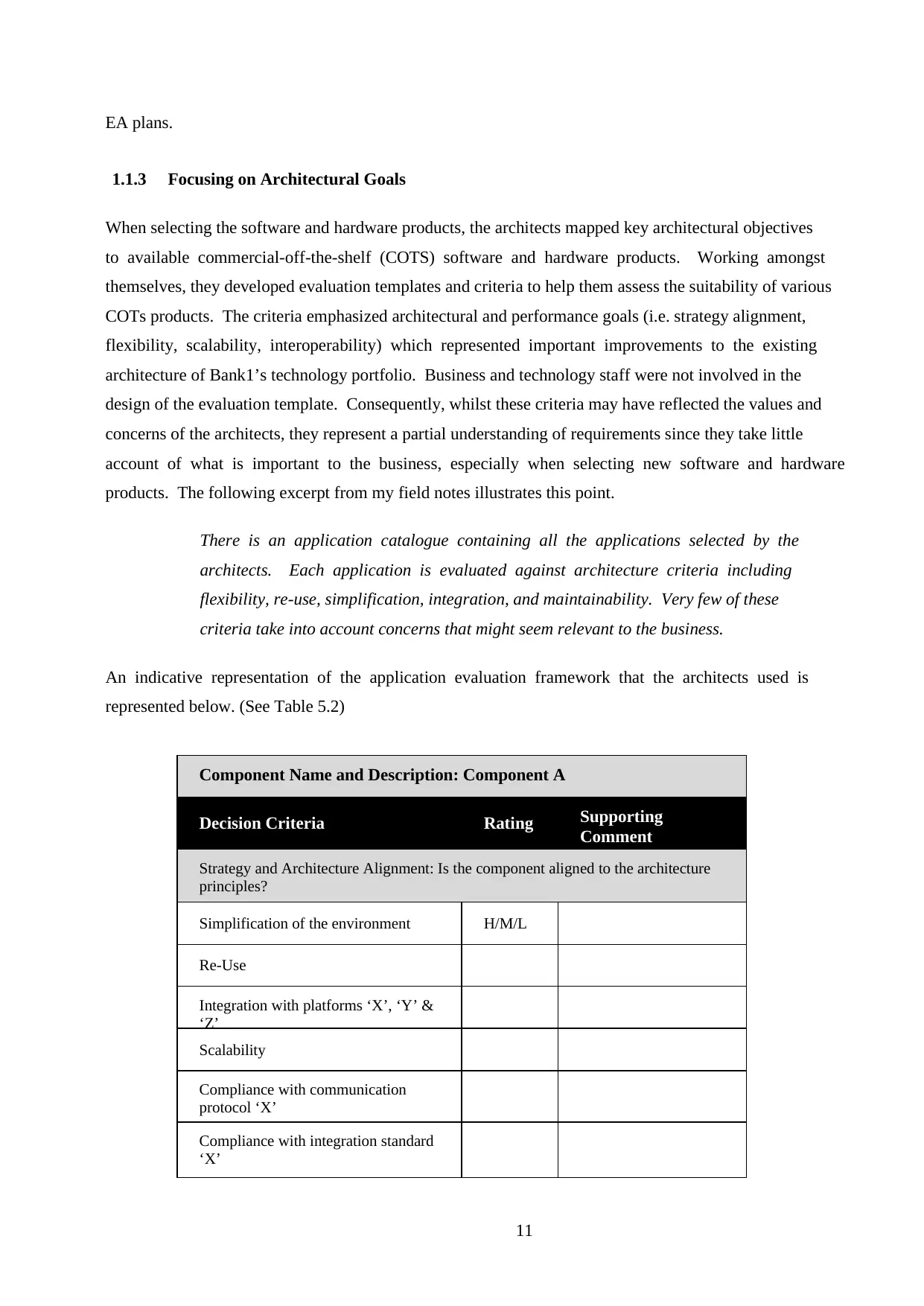

The following diagram (See Figure 5.2) situates the architecture team within the organizational structure

of Bank1 and shows at what levels and areas of Bank1 this research was conducted. To preserve the

anonymity of Bank1, the individual business divisions are referred to generically.

Figure 5.2 Situating the architects at Bank1

1.1.1 Information About the Research Participants

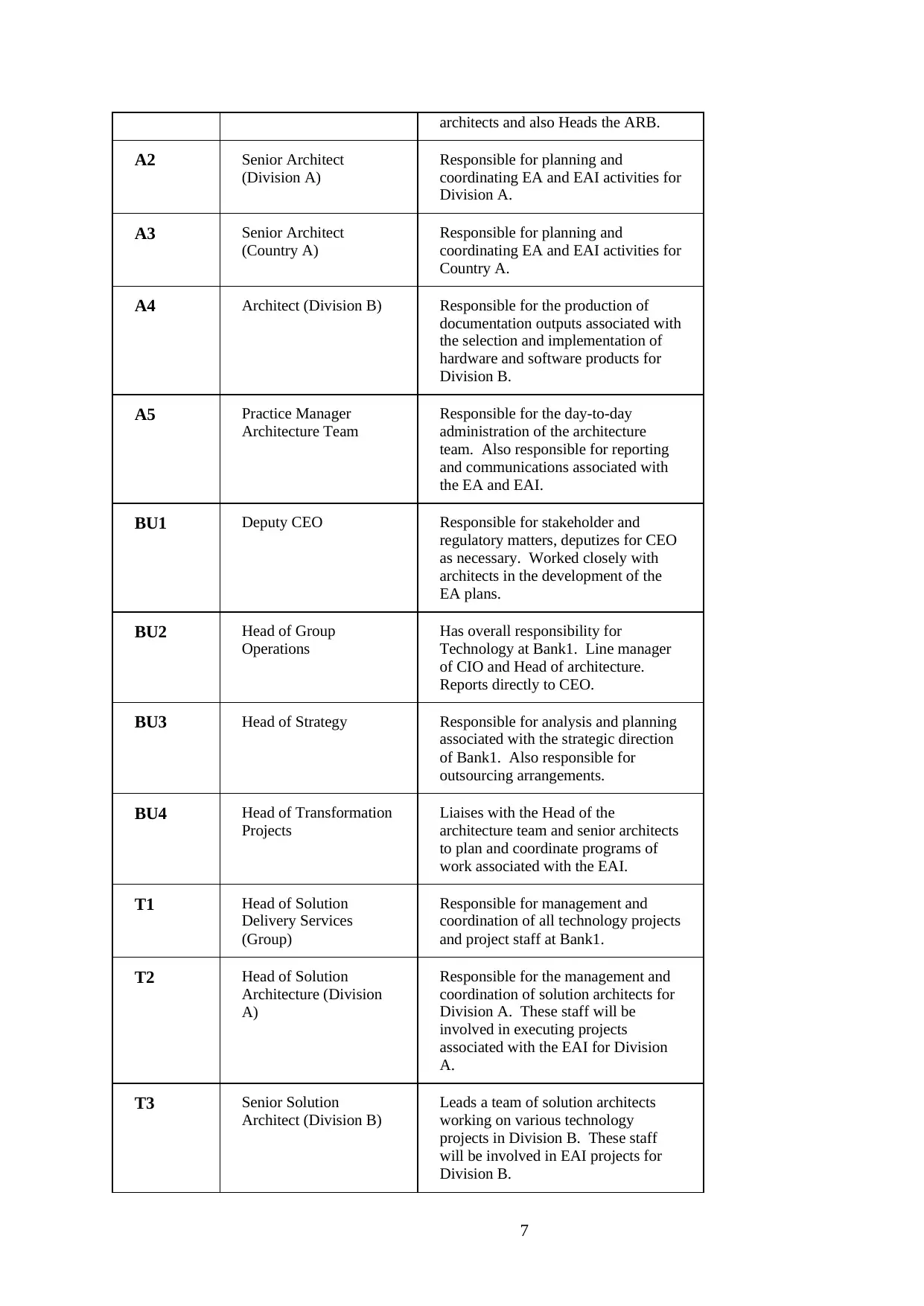

For this case study, I conducted thirteen interviews of forty-five to sixty minutes duration. The

interviews were conducted between January 2012 and June 2012. I also attended the weekly EA team

meetings for a period of four months from December 2011 – March 2012 and had access to EA

documentation including the EA methodology documentation, architectural models, EAI plans for all

business divisions, architecture review board templates and also the architecture team charter. Table 5.1

provides a summary of interview participants and their role in the EAI.

Participant Role Role description

Legend BU = Business Unit T = Technology A =

Architect

A1 Head Architecture team Has overall responsibility for EA plan

development and EAI activities of the

architecture team. Leads a team of 25

CEO

CIO Business

Division A

Deputy CEO

Enterprise

Architects

Corporate

Services ….

Solution Delivery

Services

Solution

Architecture

Services

EAI Projects

Organisational Levels

Project

Management Office

Business

Division B

Business

Division C

Business

Division D

Specifying technology projects/

Monitoring and Supporting

Project resources required to

implement EAI projects

Senior Executive level

General Management level

Project/ Operational level

Project Architects Network/ Security

Specialists

Project Managers/

BAs

= Interview participants

Infrastructure ….

The following diagram (See Figure 5.2) situates the architecture team within the organizational structure

of Bank1 and shows at what levels and areas of Bank1 this research was conducted. To preserve the

anonymity of Bank1, the individual business divisions are referred to generically.

Figure 5.2 Situating the architects at Bank1

1.1.1 Information About the Research Participants

For this case study, I conducted thirteen interviews of forty-five to sixty minutes duration. The

interviews were conducted between January 2012 and June 2012. I also attended the weekly EA team

meetings for a period of four months from December 2011 – March 2012 and had access to EA

documentation including the EA methodology documentation, architectural models, EAI plans for all

business divisions, architecture review board templates and also the architecture team charter. Table 5.1

provides a summary of interview participants and their role in the EAI.

Participant Role Role description

Legend BU = Business Unit T = Technology A =

Architect

A1 Head Architecture team Has overall responsibility for EA plan

development and EAI activities of the

architecture team. Leads a team of 25

CEO

CIO Business

Division A

Deputy CEO

Enterprise

Architects

Corporate

Services ….

Solution Delivery

Services

Solution

Architecture

Services

EAI Projects

Organisational Levels

Project

Management Office

Business

Division B

Business

Division C

Business

Division D

Specifying technology projects/

Monitoring and Supporting

Project resources required to

implement EAI projects

Senior Executive level

General Management level

Project/ Operational level

Project Architects Network/ Security

Specialists

Project Managers/

BAs

= Interview participants

Infrastructure ….

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

architects and also Heads the ARB.

A2 Senior Architect

(Division A)

Responsible for planning and

coordinating EA and EAI activities for

Division A.

A3 Senior Architect

(Country A)

Responsible for planning and

coordinating EA and EAI activities for

Country A.

A4 Architect (Division B) Responsible for the production of

documentation outputs associated with

the selection and implementation of

hardware and software products for

Division B.

A5 Practice Manager

Architecture Team

Responsible for the day-to-day

administration of the architecture

team. Also responsible for reporting

and communications associated with

the EA and EAI.

BU1 Deputy CEO Responsible for stakeholder and

regulatory matters, deputizes for CEO

as necessary. Worked closely with

architects in the development of the

EA plans.

BU2 Head of Group

Operations

Has overall responsibility for

Technology at Bank1. Line manager

of CIO and Head of architecture.

Reports directly to CEO.

BU3 Head of Strategy Responsible for analysis and planning

associated with the strategic direction

of Bank1. Also responsible for

outsourcing arrangements.

BU4 Head of Transformation

Projects

Liaises with the Head of the

architecture team and senior architects

to plan and coordinate programs of

work associated with the EAI.

T1 Head of Solution

Delivery Services

(Group)

Responsible for management and

coordination of all technology projects

and project staff at Bank1.

T2 Head of Solution

Architecture (Division

A)

Responsible for the management and

coordination of solution architects for

Division A. These staff will be

involved in executing projects

associated with the EAI for Division

A.

T3 Senior Solution

Architect (Division B)

Leads a team of solution architects

working on various technology

projects in Division B. These staff

will be involved in EAI projects for

Division B.

architects and also Heads the ARB.

A2 Senior Architect

(Division A)

Responsible for planning and

coordinating EA and EAI activities for

Division A.

A3 Senior Architect

(Country A)

Responsible for planning and

coordinating EA and EAI activities for

Country A.

A4 Architect (Division B) Responsible for the production of

documentation outputs associated with

the selection and implementation of

hardware and software products for

Division B.

A5 Practice Manager

Architecture Team

Responsible for the day-to-day

administration of the architecture

team. Also responsible for reporting

and communications associated with

the EA and EAI.

BU1 Deputy CEO Responsible for stakeholder and

regulatory matters, deputizes for CEO

as necessary. Worked closely with

architects in the development of the

EA plans.

BU2 Head of Group

Operations

Has overall responsibility for

Technology at Bank1. Line manager

of CIO and Head of architecture.

Reports directly to CEO.

BU3 Head of Strategy Responsible for analysis and planning

associated with the strategic direction

of Bank1. Also responsible for

outsourcing arrangements.

BU4 Head of Transformation

Projects

Liaises with the Head of the

architecture team and senior architects

to plan and coordinate programs of

work associated with the EAI.

T1 Head of Solution

Delivery Services

(Group)

Responsible for management and

coordination of all technology projects

and project staff at Bank1.

T2 Head of Solution

Architecture (Division

A)

Responsible for the management and

coordination of solution architects for

Division A. These staff will be

involved in executing projects

associated with the EAI for Division

A.

T3 Senior Solution

Architect (Division B)

Leads a team of solution architects

working on various technology

projects in Division B. These staff

will be involved in EAI projects for

Division B.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

T4 Senior Infrastructure

Architect (Division A)

Responsible for infrastructure

planning and design for Division A

and will be involved in EAI projects

for Division A.

Table 5.1 Summary of interview participants for Bank1

The Challenges of EAI Work

In this section, I discuss insights into the architects’ EAI roles and practices under three of the previously

discussed four themes,

• Framing EAI work – architects’ perspective,

• Practice work in the architecture team, and

• Framing EAI work – business and technology staff’s perspective.

Framing EAI Work – Architect’s Perspective

Comments categorized under this theme revealed how the architects perceived their EAI role and how

their worldview may have influenced both their practices and their relationships with business and

technology staff. When the architects reflected on the nature of their EAI role, they focused on their role

as enabling strategy and the importance of selecting the appropriate hardware and software products to

realize the new organizational strategy. The issues that emerged in this theme include, 1) the tendency

of the architects to focus on internal architecture team activities and processes, 2) the absence of business

and technology stakeholder involvement in the selection of the hardware and software products, 3) the

technological focus of the architect’s EAI efforts, and 4) the efforts made by the architects to try to stop

the business and technology from implementing new hardware and software into the environment.

1.1.2 Selecting the New Systems and Defining the Implementation Plans

The main objective of the architects’ EAI work, as articulated by them, was to select the new systems to

deliver the new organizational strategy and develop the implementation plans to deliver those systems

into operation. My field notes indicate that the architects allowed themselves twelve months to complete

the EA plans and begin implementing the new systems. It appears from the comments of A2 that the

architects wanted to be seen as proactive in responding to the new organizational strategy.

Once the strategy was announced, we moved fast. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be visible.

T4 Senior Infrastructure

Architect (Division A)

Responsible for infrastructure

planning and design for Division A

and will be involved in EAI projects

for Division A.

Table 5.1 Summary of interview participants for Bank1

The Challenges of EAI Work

In this section, I discuss insights into the architects’ EAI roles and practices under three of the previously

discussed four themes,

• Framing EAI work – architects’ perspective,

• Practice work in the architecture team, and

• Framing EAI work – business and technology staff’s perspective.

Framing EAI Work – Architect’s Perspective

Comments categorized under this theme revealed how the architects perceived their EAI role and how

their worldview may have influenced both their practices and their relationships with business and

technology staff. When the architects reflected on the nature of their EAI role, they focused on their role

as enabling strategy and the importance of selecting the appropriate hardware and software products to

realize the new organizational strategy. The issues that emerged in this theme include, 1) the tendency

of the architects to focus on internal architecture team activities and processes, 2) the absence of business

and technology stakeholder involvement in the selection of the hardware and software products, 3) the

technological focus of the architect’s EAI efforts, and 4) the efforts made by the architects to try to stop

the business and technology from implementing new hardware and software into the environment.

1.1.2 Selecting the New Systems and Defining the Implementation Plans

The main objective of the architects’ EAI work, as articulated by them, was to select the new systems to

deliver the new organizational strategy and develop the implementation plans to deliver those systems

into operation. My field notes indicate that the architects allowed themselves twelve months to complete

the EA plans and begin implementing the new systems. It appears from the comments of A2 that the

architects wanted to be seen as proactive in responding to the new organizational strategy.

Once the strategy was announced, we moved fast. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be visible.

9

We developed the architecture, leveraging earlier architecture designs and we got

approval from the executive leadership. Then we defined the technology assets [i.e.

products] and implementation plans. We made the decision on which systems the

businesses needed to execute the strategy. The business wasn’t involved … the

architecture and roadmaps [implementation plans] were completed in twelve months

(A2).

The implementation plans describe the various hardware and software products, how they should be

implemented, the sequence in which they should be implemented and how the existing legacy systems

would be decommissioned. The architects allowed themselves six months (June-December 2011) to

complete the selection of the technology components, the implementation plans and other technical

documentation, and this may form part of the explanation for their inward looking and team-focused

approach. By December of 2011, their task was not complete. In a team meeting in mid-December

2011, A1 commented,

This is a chicken and egg thing. We have to concentrate. It’s December. So we have

to define the assets [technology products] and roadmaps [implementation plans] as

soon as possible. It’s our number one priority. And to be honest, if ‘X’ and ‘Y’ [senior

business executives] come to me and say, “Tell me what architecture I have to

implement?” We only have bits and pieces … We’ve [been] talking for six months

about transaction management and we still don’t have anything. There’s no criticism

or blame, but as long as we don’t have anything, no one is going to listen to us. It

becomes almost a joke, transaction management. It’s the same in the corporate

center, the same in integration but, there at least we have something moving, but we

still don’t have the assets defined (A1).

In selecting the various hardware and software products, the architects did not liaise with business and

technology stakeholders and seemed to assume that it was not important to do so.

We are identifying the technology products that will deliver the new strategy. We’re

not focusing on business processes … They will come later. At this time, we’re

focusing only on hardware and software (A2).

Our role is first and all, to define the technology components and the implementation

plans. That’s all we do (A1).

Irrespective of what the business wants, we build technology capabilities (A1).

The technical and technology focus of the architect’s efforts may also be a result of recruitment practices

We developed the architecture, leveraging earlier architecture designs and we got

approval from the executive leadership. Then we defined the technology assets [i.e.

products] and implementation plans. We made the decision on which systems the

businesses needed to execute the strategy. The business wasn’t involved … the

architecture and roadmaps [implementation plans] were completed in twelve months

(A2).

The implementation plans describe the various hardware and software products, how they should be

implemented, the sequence in which they should be implemented and how the existing legacy systems

would be decommissioned. The architects allowed themselves six months (June-December 2011) to

complete the selection of the technology components, the implementation plans and other technical

documentation, and this may form part of the explanation for their inward looking and team-focused

approach. By December of 2011, their task was not complete. In a team meeting in mid-December

2011, A1 commented,

This is a chicken and egg thing. We have to concentrate. It’s December. So we have

to define the assets [technology products] and roadmaps [implementation plans] as

soon as possible. It’s our number one priority. And to be honest, if ‘X’ and ‘Y’ [senior

business executives] come to me and say, “Tell me what architecture I have to

implement?” We only have bits and pieces … We’ve [been] talking for six months

about transaction management and we still don’t have anything. There’s no criticism

or blame, but as long as we don’t have anything, no one is going to listen to us. It

becomes almost a joke, transaction management. It’s the same in the corporate

center, the same in integration but, there at least we have something moving, but we

still don’t have the assets defined (A1).

In selecting the various hardware and software products, the architects did not liaise with business and

technology stakeholders and seemed to assume that it was not important to do so.

We are identifying the technology products that will deliver the new strategy. We’re

not focusing on business processes … They will come later. At this time, we’re

focusing only on hardware and software (A2).

Our role is first and all, to define the technology components and the implementation

plans. That’s all we do (A1).

Irrespective of what the business wants, we build technology capabilities (A1).

The technical and technology focus of the architect’s efforts may also be a result of recruitment practices

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

within the team, which gave preference to people with technical architecture experience.

I used to work for HSBC in the UK where I was a strategy manager for the technology

department. So, I do have a technology bias. That may give you a perception of where

my answers are coming from because…I don’t look at it from an organization point

of view. I look at it from a technology point of view (A3).

The architects worked closely with one another, consulted representatives from other organizations and

also liaised with vendors when deciding which products they would select. My field note observations

record the following.

In the team meetings, the architects discuss the progress of the technology selections

for each of the business divisions. It appears from these meetings, that once the EA

was approved by the business executives, the architects immediately began meeting

with hardware and software vendors, locally and internationally in order to identify

hardware and software products that could deliver the technology capabilities and

organizational capabilities (e.g. inter-divisional data management, transaction

management) specified in the EA. They attended product demonstrations locally and

internationally, reviewed product documentation, and talked to people in reference

organizations where a particular software and hardware product had been

implemented. They also talked to and took advice from other architects in their team

and discussed potential hardware and software solutions with them. In team meetings,

the architects also discuss and compare the suitability of particular products. On the

basis of their interactions with vendors and colleagues, the architects selected the

hardware and software products they thought would deliver the new strategy.

Business and technology were not involved in the selection of any of these products

and they were not involved in discussions with vendors or product demonstrations.

It is suggested in the comments by A1 that he expected the senior business executives, based on their

approval of the EA plans, to fund the software and hardware products and their implementation. Having

previously spent many years working as an architect in some major European banks, A1 said that in his

experience the “European way was to honor the agreements you made” and that he did not expect to

have to seek the approval of the senior executives to fund the technology components and

implementation plans. Whilst the expectations of A1 may be consistent with his previous employment

experiences, they do suggest an underlying assumption that the transition from the production of the EA

plans to the implementation of those plans is straightforward and an outcome of the acceptance of the

within the team, which gave preference to people with technical architecture experience.

I used to work for HSBC in the UK where I was a strategy manager for the technology

department. So, I do have a technology bias. That may give you a perception of where

my answers are coming from because…I don’t look at it from an organization point

of view. I look at it from a technology point of view (A3).

The architects worked closely with one another, consulted representatives from other organizations and

also liaised with vendors when deciding which products they would select. My field note observations

record the following.

In the team meetings, the architects discuss the progress of the technology selections

for each of the business divisions. It appears from these meetings, that once the EA

was approved by the business executives, the architects immediately began meeting

with hardware and software vendors, locally and internationally in order to identify

hardware and software products that could deliver the technology capabilities and

organizational capabilities (e.g. inter-divisional data management, transaction

management) specified in the EA. They attended product demonstrations locally and

internationally, reviewed product documentation, and talked to people in reference

organizations where a particular software and hardware product had been

implemented. They also talked to and took advice from other architects in their team

and discussed potential hardware and software solutions with them. In team meetings,

the architects also discuss and compare the suitability of particular products. On the

basis of their interactions with vendors and colleagues, the architects selected the

hardware and software products they thought would deliver the new strategy.

Business and technology were not involved in the selection of any of these products

and they were not involved in discussions with vendors or product demonstrations.

It is suggested in the comments by A1 that he expected the senior business executives, based on their

approval of the EA plans, to fund the software and hardware products and their implementation. Having

previously spent many years working as an architect in some major European banks, A1 said that in his

experience the “European way was to honor the agreements you made” and that he did not expect to

have to seek the approval of the senior executives to fund the technology components and

implementation plans. Whilst the expectations of A1 may be consistent with his previous employment

experiences, they do suggest an underlying assumption that the transition from the production of the EA

plans to the implementation of those plans is straightforward and an outcome of the acceptance of the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

EA plans.

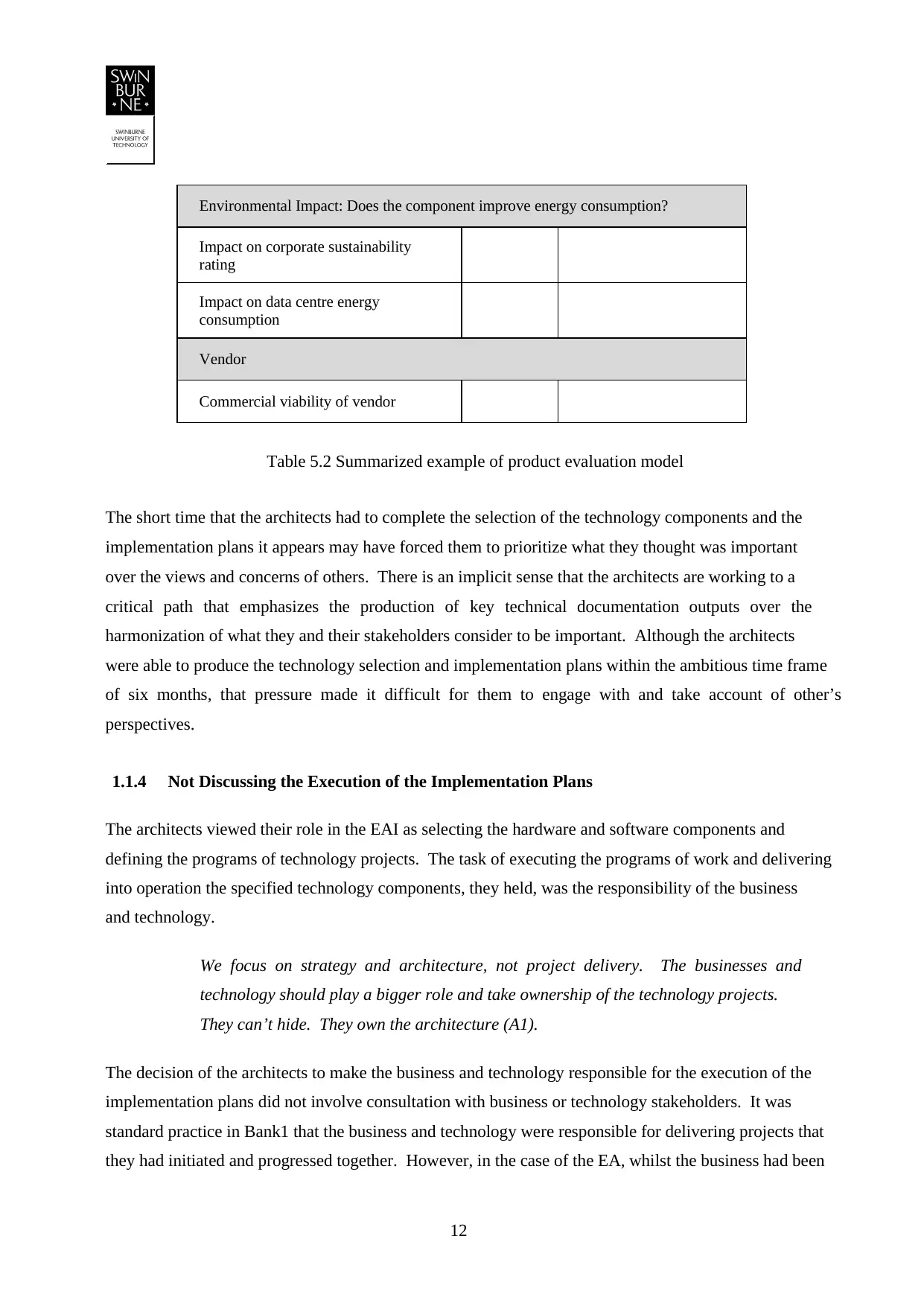

1.1.3 Focusing on Architectural Goals

When selecting the software and hardware products, the architects mapped key architectural objectives

to available commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) software and hardware products. Working amongst

themselves, they developed evaluation templates and criteria to help them assess the suitability of various

COTs products. The criteria emphasized architectural and performance goals (i.e. strategy alignment,

flexibility, scalability, interoperability) which represented important improvements to the existing

architecture of Bank1’s technology portfolio. Business and technology staff were not involved in the

design of the evaluation template. Consequently, whilst these criteria may have reflected the values and

concerns of the architects, they represent a partial understanding of requirements since they take little

account of what is important to the business, especially when selecting new software and hardware

products. The following excerpt from my field notes illustrates this point.

There is an application catalogue containing all the applications selected by the

architects. Each application is evaluated against architecture criteria including

flexibility, re-use, simplification, integration, and maintainability. Very few of these

criteria take into account concerns that might seem relevant to the business.

An indicative representation of the application evaluation framework that the architects used is

represented below. (See Table 5.2)

Component Name and Description: Component A

Decision Criteria Rating Supporting

Comment

Strategy and Architecture Alignment: Is the component aligned to the architecture

principles?

Simplification of the environment H/M/L

Re-Use

Integration with platforms ‘X’, ‘Y’ &

‘Z’

Scalability

Compliance with communication

protocol ‘X’

Compliance with integration standard

‘X’

EA plans.

1.1.3 Focusing on Architectural Goals

When selecting the software and hardware products, the architects mapped key architectural objectives

to available commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) software and hardware products. Working amongst

themselves, they developed evaluation templates and criteria to help them assess the suitability of various

COTs products. The criteria emphasized architectural and performance goals (i.e. strategy alignment,

flexibility, scalability, interoperability) which represented important improvements to the existing

architecture of Bank1’s technology portfolio. Business and technology staff were not involved in the

design of the evaluation template. Consequently, whilst these criteria may have reflected the values and

concerns of the architects, they represent a partial understanding of requirements since they take little

account of what is important to the business, especially when selecting new software and hardware

products. The following excerpt from my field notes illustrates this point.

There is an application catalogue containing all the applications selected by the

architects. Each application is evaluated against architecture criteria including

flexibility, re-use, simplification, integration, and maintainability. Very few of these

criteria take into account concerns that might seem relevant to the business.

An indicative representation of the application evaluation framework that the architects used is

represented below. (See Table 5.2)

Component Name and Description: Component A

Decision Criteria Rating Supporting

Comment

Strategy and Architecture Alignment: Is the component aligned to the architecture

principles?

Simplification of the environment H/M/L

Re-Use

Integration with platforms ‘X’, ‘Y’ &

‘Z’

Scalability

Compliance with communication

protocol ‘X’

Compliance with integration standard

‘X’

12

Environmental Impact: Does the component improve energy consumption?

Impact on corporate sustainability

rating

Impact on data centre energy

consumption

Vendor

Commercial viability of vendor

Table 5.2 Summarized example of product evaluation model

The short time that the architects had to complete the selection of the technology components and the

implementation plans it appears may have forced them to prioritize what they thought was important

over the views and concerns of others. There is an implicit sense that the architects are working to a

critical path that emphasizes the production of key technical documentation outputs over the

harmonization of what they and their stakeholders consider to be important. Although the architects

were able to produce the technology selection and implementation plans within the ambitious time frame

of six months, that pressure made it difficult for them to engage with and take account of other’s

perspectives.

1.1.4 Not Discussing the Execution of the Implementation Plans

The architects viewed their role in the EAI as selecting the hardware and software components and

defining the programs of technology projects. The task of executing the programs of work and delivering

into operation the specified technology components, they held, was the responsibility of the business

and technology.

We focus on strategy and architecture, not project delivery. The businesses and

technology should play a bigger role and take ownership of the technology projects.

They can’t hide. They own the architecture (A1).

The decision of the architects to make the business and technology responsible for the execution of the

implementation plans did not involve consultation with business or technology stakeholders. It was

standard practice in Bank1 that the business and technology were responsible for delivering projects that

they had initiated and progressed together. However, in the case of the EA, whilst the business had been

Environmental Impact: Does the component improve energy consumption?

Impact on corporate sustainability

rating

Impact on data centre energy

consumption

Vendor

Commercial viability of vendor

Table 5.2 Summarized example of product evaluation model

The short time that the architects had to complete the selection of the technology components and the

implementation plans it appears may have forced them to prioritize what they thought was important

over the views and concerns of others. There is an implicit sense that the architects are working to a

critical path that emphasizes the production of key technical documentation outputs over the

harmonization of what they and their stakeholders consider to be important. Although the architects

were able to produce the technology selection and implementation plans within the ambitious time frame

of six months, that pressure made it difficult for them to engage with and take account of other’s

perspectives.

1.1.4 Not Discussing the Execution of the Implementation Plans

The architects viewed their role in the EAI as selecting the hardware and software components and

defining the programs of technology projects. The task of executing the programs of work and delivering

into operation the specified technology components, they held, was the responsibility of the business

and technology.

We focus on strategy and architecture, not project delivery. The businesses and

technology should play a bigger role and take ownership of the technology projects.

They can’t hide. They own the architecture (A1).

The decision of the architects to make the business and technology responsible for the execution of the

implementation plans did not involve consultation with business or technology stakeholders. It was

standard practice in Bank1 that the business and technology were responsible for delivering projects that

they had initiated and progressed together. However, in the case of the EA, whilst the business had been

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 31

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.