Street Art's Context and Materiality: Banksy's Slave Labour Essay

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/27

|4

|1465

|285

Essay

AI Summary

This essay examines the intersection of street art, urban context, and community through an analysis of Banksy's Slave Labour. It argues that street art, far from being mere decoration, actively shapes and strengthens the solidarity of a city. The essay delves into the reciprocal relationships between street art and its environment, discussing how the artwork's placement, symbolism, and the public reaction to its removal highlight its role as a communicative event and a democratic forum. The analysis draws on academic journals and the specific example of Slave Labour to demonstrate how street art engages with local culture, challenges capitalist ideologies, and fosters a sense of collective identity and critical reflection within urban spaces. The essay concludes by emphasizing the indivisible connection between street art and the dynamic nature of urban life.

Q: In a properly made street art piece the forms and meanings of the street are not the

backdrop, they are the working material. Find a street art or graffiti image on the street or

online and discuss its context and its materiality

Slave Labour and The Street

Word count:

By the lens of the term “street art”, the emerging nature is that street art is an inherent

collaboration between physical infrastructure, urban context, artists, business, politics,

community, and even an entire society (Kenaan 2011; Abarca 2016; Hansen & Danny 2015).

Those underlying reciprocal relationships between street art and the city context has been

illustrated by the explosion of aesthetic protests after the removal of Banksy’s Slave Labour

from a wall in North London (BBC 2013). The protests further indicate the solidaritarian

place-making practice of street art on the city (Christensen & Thor 2017). Therefore, this

essay will argue that the street art is not only shaped by the city, but performs and strengthen

solidarity of city as well. To support my premise, I will examine this through an analysis of

academic journals, as well as Banksy’s Slave Labour.

Before beginning it, it makes sense to parse out what separate “street art” from the

mainstream of art and what constitutes “the street” of “street art”. Because compared with the

institutional works of art, the city space where street art is based upon is not a blank canvas,

but a complicated and ever-changing accumulation of objects, symbols, individuals, as well

as their both obvious and potential representations. On the other hand, when the artist put the

first action on the space, another layer of contestation process between his/her own

understandings of locality and spatial dynamic culture happens. Therefore, a street artwork

can be regarded as a visualised cultural product from all multifaceted contestations in the city

space. This product can further be internalised as a part of the city culture. A professor of

philosophy Hagi Kenaan (2011, 101) thus argues that street art embraces not only a specific

spatial matrix but also a dynamic and open-ended process of multi-subjective, interventions,

tensions, contestations, and even constructions that take place within the space of the city.

The collective and dynamic nature of street art makes it more likely to be an urban

democratic communicative landscape (Christensen & Thor 2017, 585) upon which every

individual has an equal accessibility and ability to put a layer of identity and perception by

doing critical reflections or creating new works. Such can be seen clearly in Banksy’s famous

street artwork, Slave Labour.

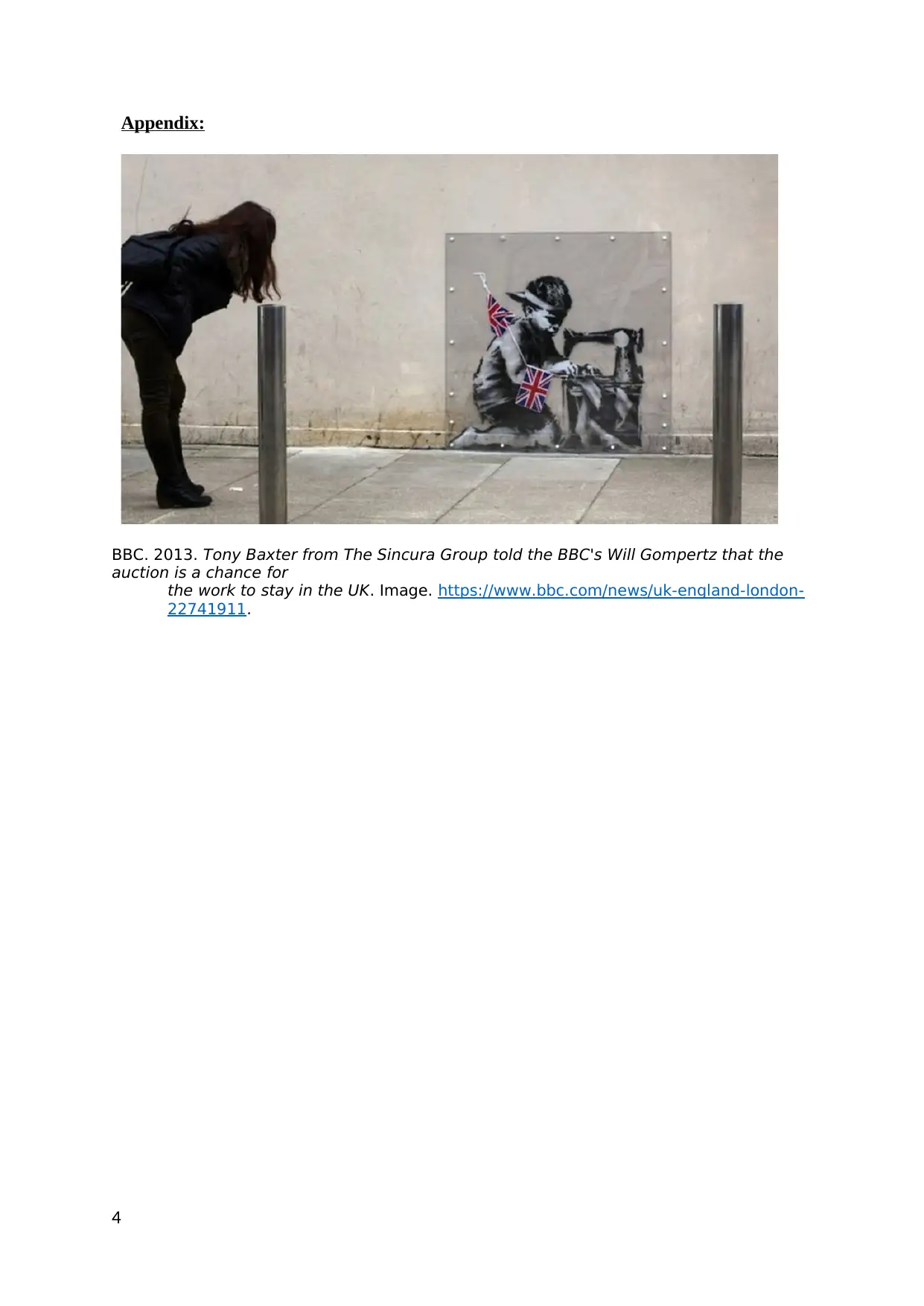

Slave Labour (Appendix 1) which shows a life-sized Asian boy figure hunching over a

sewing machine stitching union flag bunting, appeared on the wall of a Poundland store on

Whymark Avenue in Wood Green, during the lead up to the 2012 London Olympics and the

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee (BBC 2013). The positioning of the work, as a crucial element of

street art, here need to be highlighted first. Poundland, the largest discount retailer in Europe,

was heavily stocked with Jubilee merchandise at the time and some plastic Union Jack

buntings in store which are similar to the undone product on the boy’s sewing machine. The

connection between the store and this boy image is thus built by the product placement, and

directly leads viewers and passers-by to a child sweatshop labour image behind the

production of these disposable nationalistic icons. A public scandal over Poundland’s

involvement in child sweatshop labour provides viewers with another clue to interpret this

work as condemning child labour and further a dark reflection on the imminent Olympics and

the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations (Hansen & Danny 2015, 901).

1

backdrop, they are the working material. Find a street art or graffiti image on the street or

online and discuss its context and its materiality

Slave Labour and The Street

Word count:

By the lens of the term “street art”, the emerging nature is that street art is an inherent

collaboration between physical infrastructure, urban context, artists, business, politics,

community, and even an entire society (Kenaan 2011; Abarca 2016; Hansen & Danny 2015).

Those underlying reciprocal relationships between street art and the city context has been

illustrated by the explosion of aesthetic protests after the removal of Banksy’s Slave Labour

from a wall in North London (BBC 2013). The protests further indicate the solidaritarian

place-making practice of street art on the city (Christensen & Thor 2017). Therefore, this

essay will argue that the street art is not only shaped by the city, but performs and strengthen

solidarity of city as well. To support my premise, I will examine this through an analysis of

academic journals, as well as Banksy’s Slave Labour.

Before beginning it, it makes sense to parse out what separate “street art” from the

mainstream of art and what constitutes “the street” of “street art”. Because compared with the

institutional works of art, the city space where street art is based upon is not a blank canvas,

but a complicated and ever-changing accumulation of objects, symbols, individuals, as well

as their both obvious and potential representations. On the other hand, when the artist put the

first action on the space, another layer of contestation process between his/her own

understandings of locality and spatial dynamic culture happens. Therefore, a street artwork

can be regarded as a visualised cultural product from all multifaceted contestations in the city

space. This product can further be internalised as a part of the city culture. A professor of

philosophy Hagi Kenaan (2011, 101) thus argues that street art embraces not only a specific

spatial matrix but also a dynamic and open-ended process of multi-subjective, interventions,

tensions, contestations, and even constructions that take place within the space of the city.

The collective and dynamic nature of street art makes it more likely to be an urban

democratic communicative landscape (Christensen & Thor 2017, 585) upon which every

individual has an equal accessibility and ability to put a layer of identity and perception by

doing critical reflections or creating new works. Such can be seen clearly in Banksy’s famous

street artwork, Slave Labour.

Slave Labour (Appendix 1) which shows a life-sized Asian boy figure hunching over a

sewing machine stitching union flag bunting, appeared on the wall of a Poundland store on

Whymark Avenue in Wood Green, during the lead up to the 2012 London Olympics and the

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee (BBC 2013). The positioning of the work, as a crucial element of

street art, here need to be highlighted first. Poundland, the largest discount retailer in Europe,

was heavily stocked with Jubilee merchandise at the time and some plastic Union Jack

buntings in store which are similar to the undone product on the boy’s sewing machine. The

connection between the store and this boy image is thus built by the product placement, and

directly leads viewers and passers-by to a child sweatshop labour image behind the

production of these disposable nationalistic icons. A public scandal over Poundland’s

involvement in child sweatshop labour provides viewers with another clue to interpret this

work as condemning child labour and further a dark reflection on the imminent Olympics and

the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations (Hansen & Danny 2015, 901).

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Besides sensibly accumulating the meanings and connotations of the objects from this

space, Banksy injects his understandings and perceptions of this space, this community, this

whole city and even the time into the accumulation and visualising process (Abarca 2016,

61). This stencilled Asian boy thus can be understood as Banksy’s engagement with the city

as a collage of environment and source materials. From the perspective of viewers, this

visualised city engagement embracing relationships with local culture is similar to a street

sign or street name according to semiotics, which means that it in essence is complete

accessible and understandable by passers-by, and based upon a specific urban context,

informs the viewer of the intended critical meaning using explicit visual cues (Christensen &

Thor 2017, 594). But being different from simple street signs and names, Slave Labour can

become communicative events (594) – a magnet that attracts more street artworks to visually

colonise the entire current sphere, but simultaneously and constantly effacing other images

(Kenaan 2011,103). For viewers, Slave labour intervenes in the habitual communication

between individual and dominated capitalist space under a homogenizing ideology and

reveals the radical divisions and specific dark children labour fact existing in the public realm

(McDonough 1994, 69). Due to simultaneously partaking of a differential network of

changing and accumulating visual signs and individual reflections, it is gradually internalised

in the community as a democratic forum within which every people has the right to express

and speak on any specific political character.

Once this democracy is emerging, all visual images and all objects on the wall are conjoined

in their function as creating connectivity and reciprocity, as well as “solidatarian place-

making” a sub-landscape under hegemony urban space (Christensen & Thor 2017, 587). Here

“solidatarian place-making” is understood as an encouragement to mutual understanding and

respect for our positions in urban environment (587) and a call for action to do critical

reflections on established urban spaces as a free spectator rather than a part of the capitalism

world. Based upon the place-making practice, the Slave Labour’s removal implies not only a

deprivation of an asset of the community, but a destruction of an integral cultural system of

this space. Such is highlighted by a subsequent series of self-consciously egalitarian works of

aesthetic protest on the wall (Hansen & Danny 2015, 899), all of which express the outrage

on the extraction of their own public, democratic, accessible and readable platform rather

than of a famous artwork itself.

To conclude, we can observe that by looking at the analysis of Banksy’s Slave Labour,

images created on the street is understood as being shaped by changing and intersecting

objects, symbols and culture, consequently being internalised into a part of the dynamic of

urban space (Kenaan 2011, 103). The community reaction and aesthetic protest on the wall

after its removal further proves the indivisibility of street art and urban space.

2

space, Banksy injects his understandings and perceptions of this space, this community, this

whole city and even the time into the accumulation and visualising process (Abarca 2016,

61). This stencilled Asian boy thus can be understood as Banksy’s engagement with the city

as a collage of environment and source materials. From the perspective of viewers, this

visualised city engagement embracing relationships with local culture is similar to a street

sign or street name according to semiotics, which means that it in essence is complete

accessible and understandable by passers-by, and based upon a specific urban context,

informs the viewer of the intended critical meaning using explicit visual cues (Christensen &

Thor 2017, 594). But being different from simple street signs and names, Slave Labour can

become communicative events (594) – a magnet that attracts more street artworks to visually

colonise the entire current sphere, but simultaneously and constantly effacing other images

(Kenaan 2011,103). For viewers, Slave labour intervenes in the habitual communication

between individual and dominated capitalist space under a homogenizing ideology and

reveals the radical divisions and specific dark children labour fact existing in the public realm

(McDonough 1994, 69). Due to simultaneously partaking of a differential network of

changing and accumulating visual signs and individual reflections, it is gradually internalised

in the community as a democratic forum within which every people has the right to express

and speak on any specific political character.

Once this democracy is emerging, all visual images and all objects on the wall are conjoined

in their function as creating connectivity and reciprocity, as well as “solidatarian place-

making” a sub-landscape under hegemony urban space (Christensen & Thor 2017, 587). Here

“solidatarian place-making” is understood as an encouragement to mutual understanding and

respect for our positions in urban environment (587) and a call for action to do critical

reflections on established urban spaces as a free spectator rather than a part of the capitalism

world. Based upon the place-making practice, the Slave Labour’s removal implies not only a

deprivation of an asset of the community, but a destruction of an integral cultural system of

this space. Such is highlighted by a subsequent series of self-consciously egalitarian works of

aesthetic protest on the wall (Hansen & Danny 2015, 899), all of which express the outrage

on the extraction of their own public, democratic, accessible and readable platform rather

than of a famous artwork itself.

To conclude, we can observe that by looking at the analysis of Banksy’s Slave Labour,

images created on the street is understood as being shaped by changing and intersecting

objects, symbols and culture, consequently being internalised into a part of the dynamic of

urban space (Kenaan 2011, 103). The community reaction and aesthetic protest on the wall

after its removal further proves the indivisibility of street art and urban space.

2

References:

Abarca, Javier. 2016. "From street art to murals, what have we lost?". the Street Art and

Urban

Creativity Scientific Journal 2 (2): 60-67.

BBC, 2013. "Banksy's Slave Labour auctioned". BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-

england-london-22741911

Christensen, Miyase & Thor, Tindra. 2017. "The reciprocal city: Performing solidarity—

Mediating space through street art and graffiti". International Communication

Gazette 79 (6-7): 584-612.

Hansen, Susan & Danny, Flynn. 2015. "‘This is not a Banksy!’: street art as aesthetic

protest". Continuum 29 (6): 898-912.

McDonough, Thomas F. 1994. "Situationist Space". October 67 (Winter, 1994): 58-77.

Kenaan, Hagi. 2011. "Street Art and the Sovereign’s Imagination". Street Art in Israel: 97-

107.

3

Abarca, Javier. 2016. "From street art to murals, what have we lost?". the Street Art and

Urban

Creativity Scientific Journal 2 (2): 60-67.

BBC, 2013. "Banksy's Slave Labour auctioned". BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-

england-london-22741911

Christensen, Miyase & Thor, Tindra. 2017. "The reciprocal city: Performing solidarity—

Mediating space through street art and graffiti". International Communication

Gazette 79 (6-7): 584-612.

Hansen, Susan & Danny, Flynn. 2015. "‘This is not a Banksy!’: street art as aesthetic

protest". Continuum 29 (6): 898-912.

McDonough, Thomas F. 1994. "Situationist Space". October 67 (Winter, 1994): 58-77.

Kenaan, Hagi. 2011. "Street Art and the Sovereign’s Imagination". Street Art in Israel: 97-

107.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Appendix:

BBC. 2013. Tony Baxter from The Sincura Group told the BBC's Will Gompertz that the

auction is a chance for

the work to stay in the UK. Image. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-

22741911.

4

BBC. 2013. Tony Baxter from The Sincura Group told the BBC's Will Gompertz that the

auction is a chance for

the work to stay in the UK. Image. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-

22741911.

4

1 out of 4

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.