A Qualitative Analysis: Barriers and Facilitators in CNCP Management

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|7

|9189

|406

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a qualitative analysis of primary care providers' (PCPs) experiences and attitudes regarding chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) management. Conducted within the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, the study aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to improve CNCP care for veterans. Data were collected through open-ended surveys completed by 45 PCPs and analyzed using qualitative content analysis to identify recurring themes across system, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains. The findings revealed eleven key themes, including inadequate training, organizational impediments, clinical challenges, and interpersonal issues. Facilitators included intellectual satisfaction, improved communication skills, therapeutic alliances, universal protocols, and access to complementary medicine. The research highlights the need for strategies to mitigate barriers and enhance positive aspects of CNCP management to improve patient care and provider satisfaction. The study underscores the importance of addressing the challenges faced by PCPs in managing CNCP and provides insights for system-wide improvements in pain management within the VHA.

Lincoln et al., J Palliative Care Med 2013

DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.S3-00

Research Article Open Access

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management

in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’

Experiences and Attitudes

L Elizabeth Lincoln1,2*, Linda Pellico3, Robert Kerns2,4,5 and Daren Anderson6

1Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

2VA Connecticut Health Care System, USA

3Yale University School of Nursing, USA

4Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

5Department of Psychology, Yale University, USA

6Community Health Center Inc., USA

Abstract

Objectives: Most patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) are cared for, by primary care providers (PCPs).

While some of the barriers faced by PCPs have been described, there is little information about PCPs’ experience with

factors that facilitate CNCP care.

Design: The study design was descriptive and qualitative. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Krippendorff’s thematic clustering technique was used to identify the repetitive themes regarding PCPs’ experiences

related to CNCP management.

Subjects: Respondents were PCPs (n=45) in the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in two academically affiliated

institutions and six community based sites.

Results: Eleven themes were identified across systems, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Barriers included inadequate training, organizational impediments, clinical quandaries and the frustrations that

accompany them, issues related to share care among PCPs and specialists, antagonistic aspects of provider-patient

interactions, skepticism, and time factors. Facilitators included the intellectual satisfaction of solving difficult diagnostic

and management problems, the ability to develop keener communication skills, the rewards of healing and building

therapeutic alliances with patients, universal protocols, and the availability of complementary and alternative medicine

resources and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion: PCPs experience substantial difficulties in caring for patients with pain while acknowledging certain

positive aspects. There is a need for strategies that mitigate the barriers to pain management while bolstering the

positive aspects to improve care and provider satisfaction.

*Corresponding author: L Elizabeth Lincoln, Instructor, Department of

Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital 55 Fruit

St, Yawkey 4B, Suite 4700 Boston, MA 02114, USA, Tel: 203-752-6168; E-mail:

llincoln2@partners.org

Received February 25, 2013; Accepted March 08, 2013; Published March 11,

2013

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators

to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis

of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3:

001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Copyright: © 2013 Lincoln LE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.

Keywords:Primary care; Chronic pain; Pain management; Primary

care providers; Ambulatory care

Introduction

Pain and effective pain care are among the most critical health

issues facing Americans. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine reported

that about one-third of all Americans experience persistent pain at an

annual cost of as much as $635 billion in medical treatment and lost

productivity. The report noted that military veterans are an especially

vulnerable group, with data documenting a particularly high prevalence

of pain and extraordinary rates of complexity associated with multiple

medical and mental health comorbidities [1].

Pain is the most common symptom reported by patients receiving

care in primary care, accounting for up to 40% of all visits to primary

care providers (PCPs) [2]. More than half of all patients who have

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain (CNCP) receive their care primarily from

PCPs [3].Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of male veterans and

up to 75% of female veterans seen in Veteran’s Health Administration

(VHA) primary care settings report the presence of pain [4-6]. More

recent data suggest that the prevalence of CNCP, particularly painful

musculoskeletal disorders including chronic low back pain, is increasing

annually [7]. Cost effective strategies that improve the management of

CNCP in the primary care setting are needed to address the challenges

posed by this public health crisis.

The VHA has implementeda SteppedCare Model for Pain

Management (SCM-PM) as a national pain care strategy to meet the

needs of veterans [8]. The SCM-PM provides for effective assessment

and treatment of pain within primary care whenever poss

the capacity to escalate treatment options to include specialize

and interdisciplinary approaches, if needed. Critical to the succ

the SCM-PM is the ability of PCPs and multidisciplinary primary

teams to effectively access and manage most common pain co

The SCM-PM is similar to that advocated by the American Acad

of Pain Medicine [9], and it was cited by the Institute of Medicin

potentially important model of care for persons with CNCP [1].

Unfortunately,the literaturesuggeststhat PCPs do not feel

adequately prepared to take on the role of frontline prov

patients with CNCP. Although several studies have describ

attitudesand barriersto prescribingopioidsfor CNCP [10-14],

Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

P

a

I

I

i

a

t

i

v

e

C

a

r

e

&

M

e

d

i

c

i

n

e

ISSN: 2165-7386

DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.S3-00

Research Article Open Access

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management

in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’

Experiences and Attitudes

L Elizabeth Lincoln1,2*, Linda Pellico3, Robert Kerns2,4,5 and Daren Anderson6

1Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

2VA Connecticut Health Care System, USA

3Yale University School of Nursing, USA

4Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

5Department of Psychology, Yale University, USA

6Community Health Center Inc., USA

Abstract

Objectives: Most patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) are cared for, by primary care providers (PCPs).

While some of the barriers faced by PCPs have been described, there is little information about PCPs’ experience with

factors that facilitate CNCP care.

Design: The study design was descriptive and qualitative. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Krippendorff’s thematic clustering technique was used to identify the repetitive themes regarding PCPs’ experiences

related to CNCP management.

Subjects: Respondents were PCPs (n=45) in the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in two academically affiliated

institutions and six community based sites.

Results: Eleven themes were identified across systems, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Barriers included inadequate training, organizational impediments, clinical quandaries and the frustrations that

accompany them, issues related to share care among PCPs and specialists, antagonistic aspects of provider-patient

interactions, skepticism, and time factors. Facilitators included the intellectual satisfaction of solving difficult diagnostic

and management problems, the ability to develop keener communication skills, the rewards of healing and building

therapeutic alliances with patients, universal protocols, and the availability of complementary and alternative medicine

resources and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion: PCPs experience substantial difficulties in caring for patients with pain while acknowledging certain

positive aspects. There is a need for strategies that mitigate the barriers to pain management while bolstering the

positive aspects to improve care and provider satisfaction.

*Corresponding author: L Elizabeth Lincoln, Instructor, Department of

Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital 55 Fruit

St, Yawkey 4B, Suite 4700 Boston, MA 02114, USA, Tel: 203-752-6168; E-mail:

llincoln2@partners.org

Received February 25, 2013; Accepted March 08, 2013; Published March 11,

2013

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators

to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis

of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3:

001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Copyright: © 2013 Lincoln LE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.

Keywords:Primary care; Chronic pain; Pain management; Primary

care providers; Ambulatory care

Introduction

Pain and effective pain care are among the most critical health

issues facing Americans. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine reported

that about one-third of all Americans experience persistent pain at an

annual cost of as much as $635 billion in medical treatment and lost

productivity. The report noted that military veterans are an especially

vulnerable group, with data documenting a particularly high prevalence

of pain and extraordinary rates of complexity associated with multiple

medical and mental health comorbidities [1].

Pain is the most common symptom reported by patients receiving

care in primary care, accounting for up to 40% of all visits to primary

care providers (PCPs) [2]. More than half of all patients who have

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain (CNCP) receive their care primarily from

PCPs [3].Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of male veterans and

up to 75% of female veterans seen in Veteran’s Health Administration

(VHA) primary care settings report the presence of pain [4-6]. More

recent data suggest that the prevalence of CNCP, particularly painful

musculoskeletal disorders including chronic low back pain, is increasing

annually [7]. Cost effective strategies that improve the management of

CNCP in the primary care setting are needed to address the challenges

posed by this public health crisis.

The VHA has implementeda SteppedCare Model for Pain

Management (SCM-PM) as a national pain care strategy to meet the

needs of veterans [8]. The SCM-PM provides for effective assessment

and treatment of pain within primary care whenever poss

the capacity to escalate treatment options to include specialize

and interdisciplinary approaches, if needed. Critical to the succ

the SCM-PM is the ability of PCPs and multidisciplinary primary

teams to effectively access and manage most common pain co

The SCM-PM is similar to that advocated by the American Acad

of Pain Medicine [9], and it was cited by the Institute of Medicin

potentially important model of care for persons with CNCP [1].

Unfortunately,the literaturesuggeststhat PCPs do not feel

adequately prepared to take on the role of frontline prov

patients with CNCP. Although several studies have describ

attitudesand barriersto prescribingopioidsfor CNCP [10-14],

Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

P

a

I

I

i

a

t

i

v

e

C

a

r

e

&

M

e

d

i

c

i

n

e

ISSN: 2165-7386

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 2 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

provided with a study information sheet and a paper copy of th

survey questions. Open-ended questions were selected for this

because this tactic offers a less biased approach rather t

participant responses and it facilitates spontaneity from re

[21]. Participants were recruited at practice meetings, via mail

e-mail. Non-respondents were contacted again through e-mail

of the study staff. Study questions were:

1. Describe some barriers that you feel limit your abili

manage chronic pain.

2. Can you describe some of the positive aspects related to

for patients with chronic pain?

3. What are some of the negative aspects about caring for

with chronic pain?

The PCPs’ written comments were typed verbatim into

spreadsheetand verifiedas accurateby comparingthemto the

originalsurveydata.Respondents’commentstotalednearly3000

words; individual comments ranged from one word (“time

words (average, 11 words). Rather than code responses by eac

question, all data were merged in order to comprehend meani

entirety without losing connections between the three survey p

Three of the four authors read the aggregated comments in

and inductively coded the comments. An inductive approa

used to analyze the data since there is fragmented knowledge

to the phenomenon of PCPs’ experience with CNCP using quali

methodology[22]. In inductivecoding,the text progressesfrom

specific to general, so that individual instances are discerned a

related into a larger whole that describes the phenomenon of i

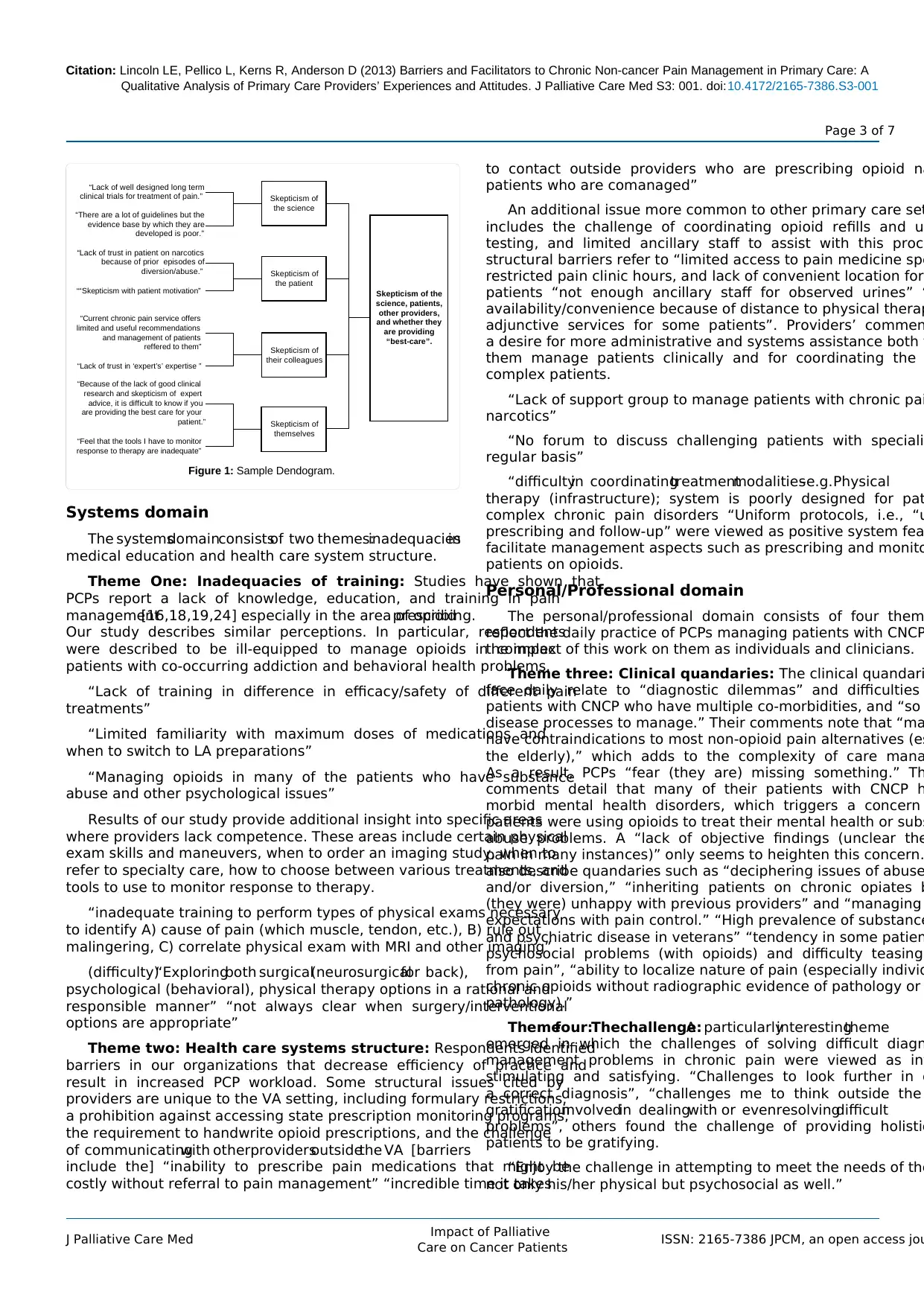

Content analysis using Krippendorff’s method [23] was used to

repetitive themes. Coding consisted of the authors separately

exact words, passages, or sentences, noting unique comments

as recurrent passages related to the research questions.

grouped according to Krippendorff’s analytical technique of clu

to identify phrases and sentences that shared some characteri

an example, statements such as “suspicion,” “lack of trust in t

expertise,” and “many comfortable patients state their pain sc

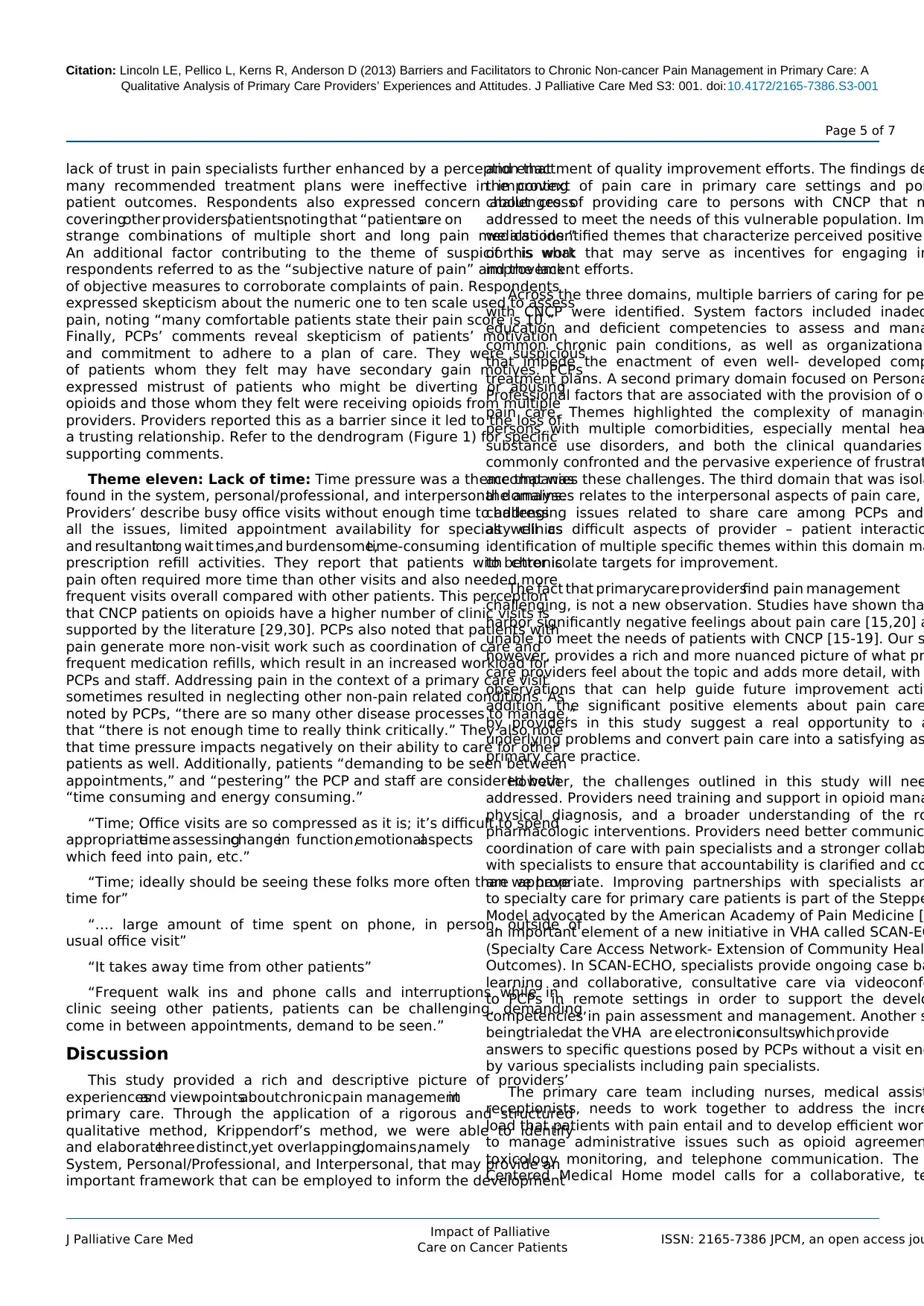

were categorized as skepticism. Dendrograms, or tree-like

were then created to illustrate how data collapsed into cl

example of a dendogram is presented in figure 1.

Authors consisted of a multidisciplinary team including a qu

nurse researcher, two primary care providers, and a pain psyc

The authorsmet frequentlyto discussselectionof passages,text

characteristics, and the transcripts were discussed line by line.

among the researchers was reconciled to represent conse

the meaning of participant comments, and the construction of

was established by group consensus. An audit trail was c

record personal reflections and to provide plausible interpretat

evidence of consistency with the original data set. The audit tr

shared with all authors. In addition, numerous participant quot

included in the results to enhance the credibility of our finding

Results

Eleven themes were identified. The themes are artificially o

into three domains as a taxonomy in which the reader c

the inter-relationships of the themes. They are: System, P

Professional, and Interpersonal domains. Two of the eleve

interrelateacrossthe threedomainsand thereforeare described

separately.

few studies provide a broad overview of CNCP management from

a provider’sperspective.Previoussurveyshaveshownthat PCPs

have concerns about the prescribing of opioids and are fearful of

contributing to addiction. In addition, PCPs note the deficiency in

primary care education and training in pain management, and question

their capacity to provide optimal pain care [15-19]. Limitations of this

research include the fact that some of these studies targeted subsets of

the broader population of primary care patients with CNCP such as

patients having high rates of opioid utilization or addiction, or included

providers other than PCPs. More information is particularly needed

about the experiences and attitudes of PCPs serving the population

of veterans. There are even fewer studies using qualitative analysis

[17,19,20]. Qualitative research offers a method of inquiry that values

the identification of the human experience related to a phenomenon

of interest and may provide a more complete understanding of PCPs’

attitudes and experiences about pain management. Interestingly, to our

knowledge, no study has specifically inquired about the positive aspects

of pain management. While we know about some of the barriers to pain

care, there is relatively little information about factors that providers

feel facilitate the care of patients with chronic pain other than opioid

agreements and a strong therapeutic doctor-patient alliance [17,20].

Our objective in conducting this study was to further describe the

context of CNCP management in primary care by exploring PCPs’

experiences and viewpoints of barriers and facilitators using qualitative

analysis. We expected that the findings would highlight important

opportunities for improving the quality of chronic pain management

in primary care not previously identified. This study was part of a larger

research project to improve the care of veterans with chronic pain at

the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and its findings

will be used to promote knowledge uptake and inform system-wide

improvements in pain management across the VHA.

Methods

Setting

The primary care section of the VACHS provides medical care to

46,000 veterans. Primary care is provided by PCPs in two large academic

medical centers and six community based practices. Comprehensive

specialty care is available to all VACHS patients. Patients have access to

pain specialists who perform consultations and procedures, as well as

to an interdisciplinary pain center.

Sample

All PCPs (N=60)wereinvitedto participatein the studyby

completinga threeitem open responsesurveyand a fifty item

knowledge questionnaire. Only results of the open response survey

are reported here. Forty-five PCPs participated, for a return rate of

75%. Respondents were 60% female and 40% male, with 40 Attending

Physicians, four Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), and

one Physician Assistant (PA). Academic faculty numbered 26. Average

time in practice since graduation from training was 17 years. On

average, approximately five percent of each provider’s panel of patients

was being treated with prescription opioid medication.

Design

Surveyquestionswere formedbasedupon currentresearch

findings, overall aims of the study, and researchers’ experience treating

patients with chronic pain. This study was reviewed and approved by

the VACHS Human Studies Subcommittee, and the Yale University

School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. A waiver of written

informedconsentwas approved.All PCPs in the VACHS were

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 2 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

provided with a study information sheet and a paper copy of th

survey questions. Open-ended questions were selected for this

because this tactic offers a less biased approach rather t

participant responses and it facilitates spontaneity from re

[21]. Participants were recruited at practice meetings, via mail

e-mail. Non-respondents were contacted again through e-mail

of the study staff. Study questions were:

1. Describe some barriers that you feel limit your abili

manage chronic pain.

2. Can you describe some of the positive aspects related to

for patients with chronic pain?

3. What are some of the negative aspects about caring for

with chronic pain?

The PCPs’ written comments were typed verbatim into

spreadsheetand verifiedas accurateby comparingthemto the

originalsurveydata.Respondents’commentstotalednearly3000

words; individual comments ranged from one word (“time

words (average, 11 words). Rather than code responses by eac

question, all data were merged in order to comprehend meani

entirety without losing connections between the three survey p

Three of the four authors read the aggregated comments in

and inductively coded the comments. An inductive approa

used to analyze the data since there is fragmented knowledge

to the phenomenon of PCPs’ experience with CNCP using quali

methodology[22]. In inductivecoding,the text progressesfrom

specific to general, so that individual instances are discerned a

related into a larger whole that describes the phenomenon of i

Content analysis using Krippendorff’s method [23] was used to

repetitive themes. Coding consisted of the authors separately

exact words, passages, or sentences, noting unique comments

as recurrent passages related to the research questions.

grouped according to Krippendorff’s analytical technique of clu

to identify phrases and sentences that shared some characteri

an example, statements such as “suspicion,” “lack of trust in t

expertise,” and “many comfortable patients state their pain sc

were categorized as skepticism. Dendrograms, or tree-like

were then created to illustrate how data collapsed into cl

example of a dendogram is presented in figure 1.

Authors consisted of a multidisciplinary team including a qu

nurse researcher, two primary care providers, and a pain psyc

The authorsmet frequentlyto discussselectionof passages,text

characteristics, and the transcripts were discussed line by line.

among the researchers was reconciled to represent conse

the meaning of participant comments, and the construction of

was established by group consensus. An audit trail was c

record personal reflections and to provide plausible interpretat

evidence of consistency with the original data set. The audit tr

shared with all authors. In addition, numerous participant quot

included in the results to enhance the credibility of our finding

Results

Eleven themes were identified. The themes are artificially o

into three domains as a taxonomy in which the reader c

the inter-relationships of the themes. They are: System, P

Professional, and Interpersonal domains. Two of the eleve

interrelateacrossthe threedomainsand thereforeare described

separately.

few studies provide a broad overview of CNCP management from

a provider’sperspective.Previoussurveyshaveshownthat PCPs

have concerns about the prescribing of opioids and are fearful of

contributing to addiction. In addition, PCPs note the deficiency in

primary care education and training in pain management, and question

their capacity to provide optimal pain care [15-19]. Limitations of this

research include the fact that some of these studies targeted subsets of

the broader population of primary care patients with CNCP such as

patients having high rates of opioid utilization or addiction, or included

providers other than PCPs. More information is particularly needed

about the experiences and attitudes of PCPs serving the population

of veterans. There are even fewer studies using qualitative analysis

[17,19,20]. Qualitative research offers a method of inquiry that values

the identification of the human experience related to a phenomenon

of interest and may provide a more complete understanding of PCPs’

attitudes and experiences about pain management. Interestingly, to our

knowledge, no study has specifically inquired about the positive aspects

of pain management. While we know about some of the barriers to pain

care, there is relatively little information about factors that providers

feel facilitate the care of patients with chronic pain other than opioid

agreements and a strong therapeutic doctor-patient alliance [17,20].

Our objective in conducting this study was to further describe the

context of CNCP management in primary care by exploring PCPs’

experiences and viewpoints of barriers and facilitators using qualitative

analysis. We expected that the findings would highlight important

opportunities for improving the quality of chronic pain management

in primary care not previously identified. This study was part of a larger

research project to improve the care of veterans with chronic pain at

the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and its findings

will be used to promote knowledge uptake and inform system-wide

improvements in pain management across the VHA.

Methods

Setting

The primary care section of the VACHS provides medical care to

46,000 veterans. Primary care is provided by PCPs in two large academic

medical centers and six community based practices. Comprehensive

specialty care is available to all VACHS patients. Patients have access to

pain specialists who perform consultations and procedures, as well as

to an interdisciplinary pain center.

Sample

All PCPs (N=60)wereinvitedto participatein the studyby

completinga threeitem open responsesurveyand a fifty item

knowledge questionnaire. Only results of the open response survey

are reported here. Forty-five PCPs participated, for a return rate of

75%. Respondents were 60% female and 40% male, with 40 Attending

Physicians, four Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), and

one Physician Assistant (PA). Academic faculty numbered 26. Average

time in practice since graduation from training was 17 years. On

average, approximately five percent of each provider’s panel of patients

was being treated with prescription opioid medication.

Design

Surveyquestionswere formedbasedupon currentresearch

findings, overall aims of the study, and researchers’ experience treating

patients with chronic pain. This study was reviewed and approved by

the VACHS Human Studies Subcommittee, and the Yale University

School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. A waiver of written

informedconsentwas approved.All PCPs in the VACHS were

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 3 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Systems domain

The systemsdomainconsistsof two themes:inadequaciesin

medical education and health care system structure.

Theme One: Inadequacies of training: Studies have shown that

PCPs report a lack of knowledge, education, and training in pain

management[16,18,19,24] especially in the area of opioidprescribing.

Our study describes similar perceptions. In particular, respondents

were described to be ill-equipped to manage opioids in complex

patients with co-occurring addiction and behavioral health problems.

“Lack of training in difference in efficacy/safety of different pain

treatments”

“Limited familiarity with maximum doses of medications and

when to switch to LA preparations”

“Managing opioids in many of the patients who have substance

abuse and other psychological issues”

Results of our study provide additional insight into specific areas

where providers lack competence. These areas include certain physical

exam skills and maneuvers, when to order an imaging study, when to

refer to specialty care, how to choose between various treatments, and

tools to use to monitor response to therapy.

“inadequate training to perform types of physical exams necessary

to identify A) cause of pain (which muscle, tendon, etc.), B) rule out

malingering, C) correlate physical exam with MRI and other imaging”

(difficulty)“Exploringboth surgical(neurosurgicalfor back),

psychological (behavioral), physical therapy options in a rational and

responsible manner” “not always clear when surgery/interventional

options are appropriate”

Theme two: Health care systems structure: Respondents identified

barriers in our organizations that decrease efficiency of practice and

result in increased PCP workload. Some structural issues cited by

providers are unique to the VA setting, including formulary restrictions,

a prohibition against accessing state prescription monitoring programs,

the requirement to handwrite opioid prescriptions, and the challenge

of communicatingwith otherprovidersoutsidethe VA [barriers

include the] “inability to prescribe pain medications that might be

costly without referral to pain management” “incredible time it takes

to contact outside providers who are prescribing opioid na

patients who are comanaged”

An additional issue more common to other primary care set

includes the challenge of coordinating opioid refills and u

testing, and limited ancillary staff to assist with this proc

structural barriers refer to “limited access to pain medicine spe

restricted pain clinic hours, and lack of convenient location for

patients “not enough ancillary staff for observed urines” “

availability/convenience because of distance to physical therap

adjunctive services for some patients”. Providers’ commen

a desire for more administrative and systems assistance both t

them manage patients clinically and for coordinating the

complex patients.

“Lack of support group to manage patients with chronic pai

narcotics”

“No forum to discuss challenging patients with speciali

regular basis”

“difficultyin coordinatingtreatmentmodalities–e.g.Physical

therapy (infrastructure); system is poorly designed for pat

complex chronic pain disorders “Uniform protocols, i.e., “u

prescribing and follow-up” were viewed as positive system fea

facilitate management aspects such as prescribing and monito

patients on opioids.

Personal/Professional domain

The personal/professional domain consists of four them

reflect the daily practice of PCPs managing patients with CNCP

the impact of this work on them as individuals and clinicians.

Theme three: Clinical quandaries: The clinical quandari

face daily relate to “diagnostic dilemmas” and difficulties

patients with CNCP who have multiple co-morbidities, and “so

disease processes to manage.” Their comments note that “ma

have contraindications to most non-opioid pain alternatives (es

the elderly),” which adds to the complexity of care mana

As a result, PCPs “fear (they are) missing something.” Th

comments detail that many of their patients with CNCP h

morbid mental health disorders, which triggers a concern

patients were using opioids to treat their mental health or subs

abuse problems. A “lack of objective findings (unclear the

pain in many instances)” only seems to heighten this concern.

also describe quandaries such as “deciphering issues of abuse

and/or diversion,” “inheriting patients on chronic opiates b

(they were) unhappy with previous providers” and “managing

expectations with pain control.” “High prevalence of substance

and psychiatric disease in veterans” “tendency in some patien

psychosocial problems (with opioids) and difficulty teasing

from pain”, “ability to localize nature of pain (especially individ

chronic opioids without radiographic evidence of pathology or

pathology).”

Themefour:Thechallenge:A particularlyinterestingtheme

emerged in which the challenges of solving difficult diagn

management problems in chronic pain were viewed as in

stimulating and satisfying. “Challenges to look further in o

a correct diagnosis”, “challenges me to think outside the

gratificationinvolvedin dealingwith or evenresolvingdifficult

problems”, others found the challenge of providing holistic

patients to be gratifying.

“Enjoy the challenge in attempting to meet the needs of the

not only his/her physical but psychosocial as well.”

Skepticism of the

science, patients,

other providers,

and whether they

are providing

“best-care”.

Skepticism of

the science

Skepticism of

the patient

Skepticism of

their colleagues

Skepticism of

themselves

“Lack of well designed long term

clinical trials for treatment of pain.”

“There are a lot of guidelines but the

evidence base by which they are

developed is poor.”

“Lack of trust in patient on narcotics

because of prior episodes of

diversion/abuse.”

““Skepticism with patient motivation”

“Current chronic pain service offers

limited and useful recommendations

and management of patients

reffered to them”

“Lack of trust in ‘expert’s’ expertise ”

“Because of the lack of good clinical

research and skepticism of expert

advice, it is difficult to know if you

are providing the best care for your

patient.”

“Feel that the tools I have to monitor

response to therapy are inadequate”

Figure 1: Sample Dendogram.

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 3 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Systems domain

The systemsdomainconsistsof two themes:inadequaciesin

medical education and health care system structure.

Theme One: Inadequacies of training: Studies have shown that

PCPs report a lack of knowledge, education, and training in pain

management[16,18,19,24] especially in the area of opioidprescribing.

Our study describes similar perceptions. In particular, respondents

were described to be ill-equipped to manage opioids in complex

patients with co-occurring addiction and behavioral health problems.

“Lack of training in difference in efficacy/safety of different pain

treatments”

“Limited familiarity with maximum doses of medications and

when to switch to LA preparations”

“Managing opioids in many of the patients who have substance

abuse and other psychological issues”

Results of our study provide additional insight into specific areas

where providers lack competence. These areas include certain physical

exam skills and maneuvers, when to order an imaging study, when to

refer to specialty care, how to choose between various treatments, and

tools to use to monitor response to therapy.

“inadequate training to perform types of physical exams necessary

to identify A) cause of pain (which muscle, tendon, etc.), B) rule out

malingering, C) correlate physical exam with MRI and other imaging”

(difficulty)“Exploringboth surgical(neurosurgicalfor back),

psychological (behavioral), physical therapy options in a rational and

responsible manner” “not always clear when surgery/interventional

options are appropriate”

Theme two: Health care systems structure: Respondents identified

barriers in our organizations that decrease efficiency of practice and

result in increased PCP workload. Some structural issues cited by

providers are unique to the VA setting, including formulary restrictions,

a prohibition against accessing state prescription monitoring programs,

the requirement to handwrite opioid prescriptions, and the challenge

of communicatingwith otherprovidersoutsidethe VA [barriers

include the] “inability to prescribe pain medications that might be

costly without referral to pain management” “incredible time it takes

to contact outside providers who are prescribing opioid na

patients who are comanaged”

An additional issue more common to other primary care set

includes the challenge of coordinating opioid refills and u

testing, and limited ancillary staff to assist with this proc

structural barriers refer to “limited access to pain medicine spe

restricted pain clinic hours, and lack of convenient location for

patients “not enough ancillary staff for observed urines” “

availability/convenience because of distance to physical therap

adjunctive services for some patients”. Providers’ commen

a desire for more administrative and systems assistance both t

them manage patients clinically and for coordinating the

complex patients.

“Lack of support group to manage patients with chronic pai

narcotics”

“No forum to discuss challenging patients with speciali

regular basis”

“difficultyin coordinatingtreatmentmodalities–e.g.Physical

therapy (infrastructure); system is poorly designed for pat

complex chronic pain disorders “Uniform protocols, i.e., “u

prescribing and follow-up” were viewed as positive system fea

facilitate management aspects such as prescribing and monito

patients on opioids.

Personal/Professional domain

The personal/professional domain consists of four them

reflect the daily practice of PCPs managing patients with CNCP

the impact of this work on them as individuals and clinicians.

Theme three: Clinical quandaries: The clinical quandari

face daily relate to “diagnostic dilemmas” and difficulties

patients with CNCP who have multiple co-morbidities, and “so

disease processes to manage.” Their comments note that “ma

have contraindications to most non-opioid pain alternatives (es

the elderly),” which adds to the complexity of care mana

As a result, PCPs “fear (they are) missing something.” Th

comments detail that many of their patients with CNCP h

morbid mental health disorders, which triggers a concern

patients were using opioids to treat their mental health or subs

abuse problems. A “lack of objective findings (unclear the

pain in many instances)” only seems to heighten this concern.

also describe quandaries such as “deciphering issues of abuse

and/or diversion,” “inheriting patients on chronic opiates b

(they were) unhappy with previous providers” and “managing

expectations with pain control.” “High prevalence of substance

and psychiatric disease in veterans” “tendency in some patien

psychosocial problems (with opioids) and difficulty teasing

from pain”, “ability to localize nature of pain (especially individ

chronic opioids without radiographic evidence of pathology or

pathology).”

Themefour:Thechallenge:A particularlyinterestingtheme

emerged in which the challenges of solving difficult diagn

management problems in chronic pain were viewed as in

stimulating and satisfying. “Challenges to look further in o

a correct diagnosis”, “challenges me to think outside the

gratificationinvolvedin dealingwith or evenresolvingdifficult

problems”, others found the challenge of providing holistic

patients to be gratifying.

“Enjoy the challenge in attempting to meet the needs of the

not only his/her physical but psychosocial as well.”

Skepticism of the

science, patients,

other providers,

and whether they

are providing

“best-care”.

Skepticism of

the science

Skepticism of

the patient

Skepticism of

their colleagues

Skepticism of

themselves

“Lack of well designed long term

clinical trials for treatment of pain.”

“There are a lot of guidelines but the

evidence base by which they are

developed is poor.”

“Lack of trust in patient on narcotics

because of prior episodes of

diversion/abuse.”

““Skepticism with patient motivation”

“Current chronic pain service offers

limited and useful recommendations

and management of patients

reffered to them”

“Lack of trust in ‘expert’s’ expertise ”

“Because of the lack of good clinical

research and skepticism of expert

advice, it is difficult to know if you

are providing the best care for your

patient.”

“Feel that the tools I have to monitor

response to therapy are inadequate”

Figure 1: Sample Dendogram.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 4 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Additionally, clinicians noted that chronic pain care helped them

develop keener interpersonal and other communication skills.

“Challenges to communicate effectively a therapeutic plan with

patient, it teaches empathy and builds patience and endurance.”

Theme five: The rewards of healing: Many PCPs commented on

the emotionally rewarding association of witnessing successful pain

care with “improvements in patient function and mood,” “improved

quality of life,” and “return to work,” with benefits accrued beyond “the

patient, to the family and society” as a whole. Providers felt personally

rewarded in “helping (patients) when they are in real discomfort,”

“empathizing with a suffering person,” and PCPs “appreciated long

term relationships” with patients. The fact that “some patients are

very gratified when you provide relief of their pain” was personally

“satisfying.” The “avoidance of long term narcotic use (with chronic

pain managed)” was also viewed as a positive outcome that left PCPs

with a sense of reward.

Theme six: Provider frustrations: Provider frustrations related to

the complexity of CNCP management and their inability to control the

patient’s pain. Their ineffectiveness ultimately impacts the providers’

sense of efficacy and self-image.

“Frustration and apathy develop over time as well as hopelessness

in the provider and resentment toward the patient.”

“Poor long term success with maintaining pain control. Sense can

never win-will never fully relieve pain or satisfy patient.”

“Frustration at inability to help patients with pain feel better.

Whatever you do is never enough and it makes the MD feel inadequate

and mean for not keeping the patient pain- free.”

Interpersonal domain

The interpersonal domain consists of three themes that cluster

around the dyad relationships of provider and provider or patient and

provider.

Theme seven: Provider-provider relationships: A lack of quality

specialtyserviceswas identifiedfrequentlyas a barrierto CNCP

management. Issues detailed by PCPs included consults being “rejected”

and a lack of collaboration and “ownership” by specialists for patients.

Complaints about lack of effective support were especially prevalent for

the pain consultants but extended to many disciplines involved in pain

management including orthopedics, rheumatology, neurosurgery, and

substance abuse. Comments suggest that PCPs believed the onus for

caring for patients with chronic pain rested on their shoulders. In this

study, the quality of consultations seemed to be more of a concern for

PCPs than issues of access as found in other studies[17,25-27].

“…they (pain specialty) spend a lot of time rejecting consults and

turfing back to primary care”

“Pain specialists do not take ownership of the patient”

“Current chronic pain service offers limited and useful

recommendations and management of patients referred to them”

Interestingly, given that opioids have become among the most

prescribed medications in the U.S. [28], some providers commented

that a deficiency in consultative services led to a personal overreliance

on pharmacologic therapy, particularly opioids.

“I work with femalepatientswho often havecomplexpain

syndromes. Our system is poorly designed to handle these patients.

They seem to fall through the cracks-when referred…… my own bag of

tricks is limited to counseling and pain medications.”

However,the availabilityof complementaryand alternative

medicine resources, such as chiropractic and acupuncture serv

the availability of a “multidisciplinary team approach” were hig

as facilitators of effective CNCP management which leads to a

collegial relationship among providers.

Themeeight:Antagonisticpatient-providerinteractions:

Troubling or unpleasant encounters between PCPs and some p

with chronic pain were noted in this study. In such encounters,

were described as “dishonest”, “manipulative”, “angry”, “a

“explosive” and “abusive” in the context of opioid use. While s

findings have been previously described [20], our respond

highlighted the unwillingness of patients to accept non-pharma

modes of treatment, particularly behavioral health interven

an additional dissatisfying element of such interactions. PC

what they perceive to be patients’ unrealistic expectations to b

free”. These encounters lead to a sense of exasperation

the comments of the PCP and set the stage for antagonistic pro

patient relationships.

“Patients tend to be problematic, ill, demanding, manipulat

even dishonest”

“Patient resistance to PT/CBT (physical therapy/cognitive be

therapy) - ‘just want a pill’”

“Difference between patient expectations in pain relief and

pain relief obtainable with multiple complex pain regimens”

Theme nine: Enjoyable patient-provider interaction

experiencedsatisfactionin creatinglong-termrelationshipswith

patients who had chronic pain. Their comments describe a shif

an acute model of care and traditional role of primary decision

to a chronic model of collaborative shared partnership between

and provider, which is viewed as enjoyable. The chronicity of C

allowed for the building of stronger relationships and commen

that some providers formulate positive attitudes that enco

effective and compassionate treatment of CNCP.

“Reward of working together with patient, to achieve goals”

“If you can enter a collaborative working relationship i

positive”

(positive aspect is) “Forming an alliance with patient t

shared goals”

“I actually enjoy working with chronic pain patients. Th

difficult and as such don’t often feel validated by some p

(particularly specialty clinics, etc.). I find that the patients often

from an empathetic ear … and I experience some reward from

able at least to empathize, validate, usually medicate, and cou

Theme ten: Skepticism: The notion of skepticism tra

threedomains(system,personal/professional,and interpersonal).

Respondentsexpressedskepticismtowardsthe scienceof pain

management, the usefulness of consultants’ advice, their

delivery of “best practice,” and patients’ motivation and partic

PCPs expressed doubt in the quality of evidence in the fi

management. Comments suggest that participants question th

clinical trials and clinical practice guidelines. Many PCPs felt th

recommended treatment modalities were ineffective in the

population. In addition, the inability to access the state p

monitoring database, a VA-specific prohibition, prevented PCPs

investigating their suspicions that some patients were receivin

from other community providers. PCPs’ comments also ex

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 4 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Additionally, clinicians noted that chronic pain care helped them

develop keener interpersonal and other communication skills.

“Challenges to communicate effectively a therapeutic plan with

patient, it teaches empathy and builds patience and endurance.”

Theme five: The rewards of healing: Many PCPs commented on

the emotionally rewarding association of witnessing successful pain

care with “improvements in patient function and mood,” “improved

quality of life,” and “return to work,” with benefits accrued beyond “the

patient, to the family and society” as a whole. Providers felt personally

rewarded in “helping (patients) when they are in real discomfort,”

“empathizing with a suffering person,” and PCPs “appreciated long

term relationships” with patients. The fact that “some patients are

very gratified when you provide relief of their pain” was personally

“satisfying.” The “avoidance of long term narcotic use (with chronic

pain managed)” was also viewed as a positive outcome that left PCPs

with a sense of reward.

Theme six: Provider frustrations: Provider frustrations related to

the complexity of CNCP management and their inability to control the

patient’s pain. Their ineffectiveness ultimately impacts the providers’

sense of efficacy and self-image.

“Frustration and apathy develop over time as well as hopelessness

in the provider and resentment toward the patient.”

“Poor long term success with maintaining pain control. Sense can

never win-will never fully relieve pain or satisfy patient.”

“Frustration at inability to help patients with pain feel better.

Whatever you do is never enough and it makes the MD feel inadequate

and mean for not keeping the patient pain- free.”

Interpersonal domain

The interpersonal domain consists of three themes that cluster

around the dyad relationships of provider and provider or patient and

provider.

Theme seven: Provider-provider relationships: A lack of quality

specialtyserviceswas identifiedfrequentlyas a barrierto CNCP

management. Issues detailed by PCPs included consults being “rejected”

and a lack of collaboration and “ownership” by specialists for patients.

Complaints about lack of effective support were especially prevalent for

the pain consultants but extended to many disciplines involved in pain

management including orthopedics, rheumatology, neurosurgery, and

substance abuse. Comments suggest that PCPs believed the onus for

caring for patients with chronic pain rested on their shoulders. In this

study, the quality of consultations seemed to be more of a concern for

PCPs than issues of access as found in other studies[17,25-27].

“…they (pain specialty) spend a lot of time rejecting consults and

turfing back to primary care”

“Pain specialists do not take ownership of the patient”

“Current chronic pain service offers limited and useful

recommendations and management of patients referred to them”

Interestingly, given that opioids have become among the most

prescribed medications in the U.S. [28], some providers commented

that a deficiency in consultative services led to a personal overreliance

on pharmacologic therapy, particularly opioids.

“I work with femalepatientswho often havecomplexpain

syndromes. Our system is poorly designed to handle these patients.

They seem to fall through the cracks-when referred…… my own bag of

tricks is limited to counseling and pain medications.”

However,the availabilityof complementaryand alternative

medicine resources, such as chiropractic and acupuncture serv

the availability of a “multidisciplinary team approach” were hig

as facilitators of effective CNCP management which leads to a

collegial relationship among providers.

Themeeight:Antagonisticpatient-providerinteractions:

Troubling or unpleasant encounters between PCPs and some p

with chronic pain were noted in this study. In such encounters,

were described as “dishonest”, “manipulative”, “angry”, “a

“explosive” and “abusive” in the context of opioid use. While s

findings have been previously described [20], our respond

highlighted the unwillingness of patients to accept non-pharma

modes of treatment, particularly behavioral health interven

an additional dissatisfying element of such interactions. PC

what they perceive to be patients’ unrealistic expectations to b

free”. These encounters lead to a sense of exasperation

the comments of the PCP and set the stage for antagonistic pro

patient relationships.

“Patients tend to be problematic, ill, demanding, manipulat

even dishonest”

“Patient resistance to PT/CBT (physical therapy/cognitive be

therapy) - ‘just want a pill’”

“Difference between patient expectations in pain relief and

pain relief obtainable with multiple complex pain regimens”

Theme nine: Enjoyable patient-provider interaction

experiencedsatisfactionin creatinglong-termrelationshipswith

patients who had chronic pain. Their comments describe a shif

an acute model of care and traditional role of primary decision

to a chronic model of collaborative shared partnership between

and provider, which is viewed as enjoyable. The chronicity of C

allowed for the building of stronger relationships and commen

that some providers formulate positive attitudes that enco

effective and compassionate treatment of CNCP.

“Reward of working together with patient, to achieve goals”

“If you can enter a collaborative working relationship i

positive”

(positive aspect is) “Forming an alliance with patient t

shared goals”

“I actually enjoy working with chronic pain patients. Th

difficult and as such don’t often feel validated by some p

(particularly specialty clinics, etc.). I find that the patients often

from an empathetic ear … and I experience some reward from

able at least to empathize, validate, usually medicate, and cou

Theme ten: Skepticism: The notion of skepticism tra

threedomains(system,personal/professional,and interpersonal).

Respondentsexpressedskepticismtowardsthe scienceof pain

management, the usefulness of consultants’ advice, their

delivery of “best practice,” and patients’ motivation and partic

PCPs expressed doubt in the quality of evidence in the fi

management. Comments suggest that participants question th

clinical trials and clinical practice guidelines. Many PCPs felt th

recommended treatment modalities were ineffective in the

population. In addition, the inability to access the state p

monitoring database, a VA-specific prohibition, prevented PCPs

investigating their suspicions that some patients were receivin

from other community providers. PCPs’ comments also ex

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 5 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

lack of trust in pain specialists further enhanced by a perception that

many recommended treatment plans were ineffective in improving

patient outcomes. Respondents also expressed concern about cross

coveringother providers’patients,noting that “patientsare on

strange combinations of multiple short and long pain medications.”

An additional factor contributing to the theme of suspicion is what

respondents referred to as the “subjective nature of pain” and the lack

of objective measures to corroborate complaints of pain. Respondents

expressed skepticism about the numeric one to ten scale used to assess

pain, noting “many comfortable patients state their pain score is 10.”

Finally, PCPs’ comments reveal skepticism of patients’ motivation

and commitment to adhere to a plan of care. They were suspicious

of patients whom they felt may have secondary gain motives. PCPs

expressed mistrust of patients who might be diverting or abusing

opioids and those whom they felt were receiving opioids from multiple

providers. Providers reported this as a barrier since it led to the loss of

a trusting relationship. Refer to the dendrogram (Figure 1) for specific

supporting comments.

Theme eleven: Lack of time: Time pressure was a theme that was

found in the system, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Providers’ describe busy office visits without enough time to address

all the issues, limited appointment availability for specialty clinics

and resultantlong wait times,and burdensome,time-consuming

prescription refill activities. They report that patients with chronic

pain often required more time than other visits and also needed more

frequent visits overall compared with other patients. This perception

that CNCP patients on opioids have a higher number of clinic visits is

supported by the literature [29,30]. PCPs also noted that patients with

pain generate more non-visit work such as coordination of care and

frequent medication refills, which result in an increased workload for

PCPs and staff. Addressing pain in the context of a primary care visit

sometimes resulted in neglecting other non-pain related conditions. As

noted by PCPs, “there are so many other disease processes to manage,”

that “there is not enough time to really think critically.” They also note

that time pressure impacts negatively on their ability to care for other

patients as well. Additionally, patients “demanding to be seen between

appointments,” and “pestering” the PCP and staff are considered both

“time consuming and energy consuming.”

“Time; Office visits are so compressed as it is; it’s difficult to spend

appropriatetime assessingchangein function,emotionalaspects

which feed into pain, etc.”

“Time; ideally should be seeing these folks more often than we have

time for”

“…. large amount of time spent on phone, in person, outside of

usual office visit”

“It takes away time from other patients”

“Frequent walk ins and phone calls and interruptions while in

clinic seeing other patients, patients can be challenging, demanding,

come in between appointments, demand to be seen.”

Discussion

This study provided a rich and descriptive picture of providers’

experiencesand viewpointsaboutchronic pain managementin

primary care. Through the application of a rigorous and structured

qualitative method, Krippendorf’s method, we were able to identify

and elaboratethree distinct,yet overlapping,domains,namely

System, Personal/Professional, and Interpersonal, that may provide an

important framework that can be employed to inform the development

and enactment of quality improvement efforts. The findings de

the context of pain care in primary care settings and poi

challenges of providing care to persons with CNCP that m

addressed to meet the needs of this vulnerable population. Im

we also identified themes that characterize perceived positive

of this work that may serve as incentives for engaging in

improvement efforts.

Across the three domains, multiple barriers of caring for pe

with CNCP were identified. System factors included inadeq

education and deficient competencies to assess and mana

common chronic pain conditions, as well as organizational

that impede the enactment of even well- developed comp

treatment plans. A second primary domain focused on Persona

Professional factors that are associated with the provision of op

pain care. Themes highlighted the complexity of managing

persons with multiple comorbidities, especially mental hea

substance use disorders, and both the clinical quandaries

commonly confronted and the pervasive experience of frustrat

accompanies these challenges. The third domain that was isola

the analyses relates to the interpersonal aspects of pain care,

challenging issues related to share care among PCPs and

as well as difficult aspects of provider – patient interactio

identification of multiple specific themes within this domain ma

to better isolate targets for improvement.

The fact that primarycare providersfind pain management

challenging, is not a new observation. Studies have shown tha

harbor significantly negative feelings about pain care [15,20] a

unable to meet the needs of patients with CNCP [15-19]. Our s

however, provides a rich and more nuanced picture of what pr

care providers feel about the topic and adds more detail, with

observations that can help guide future improvement activ

addition, the significant positive elements about pain care

by providers in this study suggest a real opportunity to a

underlying problems and convert pain care into a satisfying as

primary care practice.

However, the challenges outlined in this study will nee

addressed. Providers need training and support in opioid mana

physical diagnosis, and a broader understanding of the ro

pharmacologic interventions. Providers need better communic

coordination of care with pain specialists and a stronger collab

with specialists to ensure that accountability is clarified and co

are appropriate. Improving partnerships with specialists an

to specialty care for primary care patients is part of the Steppe

Model advocated by the American Academy of Pain Medicine [

an important element of a new initiative in VHA called SCAN-EC

(Specialty Care Access Network- Extension of Community Heal

Outcomes). In SCAN-ECHO, specialists provide ongoing case ba

learning and collaborative, consultative care via videoconfe

to PCPs in remote settings in order to support the develo

competencies in pain assessment and management. Another s

beingtrialedat the VHA are electronicconsults,which provide

answers to specific questions posed by PCPs without a visit enc

by various specialists including pain specialists.

The primary care team including nurses, medical assist

receptionists, needs to work together to address the incre

load that patients with pain entail and to develop efficient work

to manage administrative issues such as opioid agreemen

toxicology monitoring, and telephone communication. The

Centered Medical Home model calls for a collaborative, te

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 5 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

lack of trust in pain specialists further enhanced by a perception that

many recommended treatment plans were ineffective in improving

patient outcomes. Respondents also expressed concern about cross

coveringother providers’patients,noting that “patientsare on

strange combinations of multiple short and long pain medications.”

An additional factor contributing to the theme of suspicion is what

respondents referred to as the “subjective nature of pain” and the lack

of objective measures to corroborate complaints of pain. Respondents

expressed skepticism about the numeric one to ten scale used to assess

pain, noting “many comfortable patients state their pain score is 10.”

Finally, PCPs’ comments reveal skepticism of patients’ motivation

and commitment to adhere to a plan of care. They were suspicious

of patients whom they felt may have secondary gain motives. PCPs

expressed mistrust of patients who might be diverting or abusing

opioids and those whom they felt were receiving opioids from multiple

providers. Providers reported this as a barrier since it led to the loss of

a trusting relationship. Refer to the dendrogram (Figure 1) for specific

supporting comments.

Theme eleven: Lack of time: Time pressure was a theme that was

found in the system, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Providers’ describe busy office visits without enough time to address

all the issues, limited appointment availability for specialty clinics

and resultantlong wait times,and burdensome,time-consuming

prescription refill activities. They report that patients with chronic

pain often required more time than other visits and also needed more

frequent visits overall compared with other patients. This perception

that CNCP patients on opioids have a higher number of clinic visits is

supported by the literature [29,30]. PCPs also noted that patients with

pain generate more non-visit work such as coordination of care and

frequent medication refills, which result in an increased workload for

PCPs and staff. Addressing pain in the context of a primary care visit

sometimes resulted in neglecting other non-pain related conditions. As

noted by PCPs, “there are so many other disease processes to manage,”

that “there is not enough time to really think critically.” They also note

that time pressure impacts negatively on their ability to care for other

patients as well. Additionally, patients “demanding to be seen between

appointments,” and “pestering” the PCP and staff are considered both

“time consuming and energy consuming.”

“Time; Office visits are so compressed as it is; it’s difficult to spend

appropriatetime assessingchangein function,emotionalaspects

which feed into pain, etc.”

“Time; ideally should be seeing these folks more often than we have

time for”

“…. large amount of time spent on phone, in person, outside of

usual office visit”

“It takes away time from other patients”

“Frequent walk ins and phone calls and interruptions while in

clinic seeing other patients, patients can be challenging, demanding,

come in between appointments, demand to be seen.”

Discussion

This study provided a rich and descriptive picture of providers’

experiencesand viewpointsaboutchronic pain managementin

primary care. Through the application of a rigorous and structured

qualitative method, Krippendorf’s method, we were able to identify

and elaboratethree distinct,yet overlapping,domains,namely

System, Personal/Professional, and Interpersonal, that may provide an

important framework that can be employed to inform the development

and enactment of quality improvement efforts. The findings de

the context of pain care in primary care settings and poi

challenges of providing care to persons with CNCP that m

addressed to meet the needs of this vulnerable population. Im

we also identified themes that characterize perceived positive

of this work that may serve as incentives for engaging in

improvement efforts.

Across the three domains, multiple barriers of caring for pe

with CNCP were identified. System factors included inadeq

education and deficient competencies to assess and mana

common chronic pain conditions, as well as organizational

that impede the enactment of even well- developed comp

treatment plans. A second primary domain focused on Persona

Professional factors that are associated with the provision of op

pain care. Themes highlighted the complexity of managing

persons with multiple comorbidities, especially mental hea

substance use disorders, and both the clinical quandaries

commonly confronted and the pervasive experience of frustrat

accompanies these challenges. The third domain that was isola

the analyses relates to the interpersonal aspects of pain care,

challenging issues related to share care among PCPs and

as well as difficult aspects of provider – patient interactio

identification of multiple specific themes within this domain ma

to better isolate targets for improvement.

The fact that primarycare providersfind pain management

challenging, is not a new observation. Studies have shown tha

harbor significantly negative feelings about pain care [15,20] a

unable to meet the needs of patients with CNCP [15-19]. Our s

however, provides a rich and more nuanced picture of what pr

care providers feel about the topic and adds more detail, with

observations that can help guide future improvement activ

addition, the significant positive elements about pain care

by providers in this study suggest a real opportunity to a

underlying problems and convert pain care into a satisfying as

primary care practice.

However, the challenges outlined in this study will nee

addressed. Providers need training and support in opioid mana

physical diagnosis, and a broader understanding of the ro

pharmacologic interventions. Providers need better communic

coordination of care with pain specialists and a stronger collab

with specialists to ensure that accountability is clarified and co

are appropriate. Improving partnerships with specialists an

to specialty care for primary care patients is part of the Steppe

Model advocated by the American Academy of Pain Medicine [

an important element of a new initiative in VHA called SCAN-EC

(Specialty Care Access Network- Extension of Community Heal

Outcomes). In SCAN-ECHO, specialists provide ongoing case ba

learning and collaborative, consultative care via videoconfe

to PCPs in remote settings in order to support the develo

competencies in pain assessment and management. Another s

beingtrialedat the VHA are electronicconsults,which provide

answers to specific questions posed by PCPs without a visit enc

by various specialists including pain specialists.

The primary care team including nurses, medical assist

receptionists, needs to work together to address the incre

load that patients with pain entail and to develop efficient work

to manage administrative issues such as opioid agreemen

toxicology monitoring, and telephone communication. The

Centered Medical Home model calls for a collaborative, te

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 6 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access jou

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

approach to primary care [31]. Many of the systems issues cited in this

study could be improved through more effective use of a health care

team. The use of nurse care coordinators to provide support for patients

with chronic pain has been shown to improve patient satisfaction and

pain scores [32-34]. Opioid renewal clinics can improve pain care

by assigning dedicated staff to manage the opioid prescription and

monitoring process for high risk patients [35]. Other collaborative

and interdisciplinary approaches may help with the management of

patients with complex psychosocial and behavioral issues. Chronic

pain is prevalent in two-thirds of patients with major depressive

illness [36,37]. Optimizing depression in a primary care setting with

the assistance of a mental health liaison improves pain levels [38,39].

Efforts to integrate mental health care into primary care as is practiced

at the VHA should be expanded.

One particularly frequent theme that appeared in our study and

that of Matthias et al. was that of the challenging, antagonistic patient

encounter [20]. The physician-patient relationship is predicated on

trust, communication, and a patient centered partnership in which the

patient and provider work together towards a common aim. Comments

from this study suggest that such relationships often are compromised

by suspicion and lack of trust and that antagonism, frustration, and

even nihilism often pervade the encounter. In pain care, differing

expectations between patients and PCPs are common [40,41]. Lack

of concordance between patient and physician goals may contribute

many of the negative feelings about pain care expressed by study

respondents. This aspect of pain care needs to be addressed specifically.

Primary care providers need training in how to handle challenging and

unpleasant encounters and need to acquire tools, many of which are

more commonly employed by behavioral health staff, to manage these

negative emotions and better handle difficult encounters to improve

the likelihood of a positive outcome.

Our institution has piloted a peer support intervention for PCPs

who may be experiencing tension in the relationship with an individual

patient with chronic pain. In this model, PCPs can present their

experience to a committee that includes PCPs who are knowledgeable

in pain care, a behavioral health provider, and an addictions specialist.

PCPs are able to share their frustrations, receive emotional support,

and are also assisted in developing a specific plan of care. Occasionally,

members of the committee will meet with the PCP and patient together,

to help facilitateunderstandingand defusetension.Preliminary

feedback of this process from PCPs has been highly positive.

The positive factors identified in this study that facilitate CNCP

care in the primary care setting are of equal interest and have been

less described in the literature. They largely encompassed humanistic,