Bioactive Glass in Spinal Fusion

VerifiedAdded on 2020/03/16

|17

|4142

|60

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the use of bioactive glass in spinal fusion interventions, highlighting its benefits, evidence-based findings, and potential to enhance surgical outcomes. It discusses the material's properties, clinical applications, and the importance of systematic management in reducing post-operative complications. The report is supported by extensive research and references, providing a comprehensive overview of bioactive glass as a promising alternative in spinal surgery.

Project-1 Report

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1 | P a g e

Table of Content

Introduction and Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2

Bioactive glass based spinal interventions management – An evidence based analysis……………………..4

Data collection methods……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7

Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8

Discussion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10

References………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………11

1 | P a g e

Table of Content

Introduction and Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2

Bioactive glass based spinal interventions management – An evidence based analysis……………………..4

Data collection methods……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7

Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8

Discussion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10

References………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………11

1 | P a g e

2 | P a g e

Introduction and Background

Spinal fusion interventions require the systematic utilization of various ceramic

products attributing to β TCP, hydroxypartite, healos and calcium sulphate. The lumbar

spinal fusion interventions evidentially utilize ICBG (iliac crest bone graft) while undertaking

the process of joints arthrodesis (Vaz, et al., 2010). Alternatively, TCP (tricalcium phosphate)

and HA (hydroxyapatite) are also utilized in spinal fusion process due to their proven healing

characteristics (Pugely, Petersen, DeVries-Watson, & Fredericks, 2017). Evidence-based

clinical literature advocates the influence of bone graft quality on the pattern of surgically

induced spinal fusion (McGuire, Pilcher, & Dettori, 2011). The quality and configuration of

bone graft (in spinal fusion surgeries) is of paramount importance in terms of reducing the

occurrence of surgical complications and associated adverse clinical manifestations in the

treated patients (Nouh, 2012). β TCP (beta-tricalcium phosphate) is regarded as a significant

bone substitute that facilitates the formation of bone structure through the process of

osteoclast-mediated resorption (Tanaka, et al., 2017). Therefore, β TCP substitute is utilized

in various spinal fusion interventions with the objective of facilitating the regeneration of

cortical bone. Porous titanium is a bioactive metal that is evidentially utilized in configuring

bone grafts while undertaking complex spinal fusion interventions in the context of its

elevated bone bonding capacity. The alloy of titanium undergoes thermal and chemical

surface treatment to facilitate its active transformation to a bioactive material (Fujibayashi, et

al., 2011). This bioactive intervention substantially elevates the fusion capacity of titanium

implant during spinal fusion interventions. However, the research intervention by

(Ilharreborde , et al., 2008) indicates the elevated capacity and cost effectiveness of bioactive

glass (compared to other ceramic products) in terms of facilitating spinal fusion undertaken to

treat the pattern of idiopathic scoliosis. Bioactive glass is preferred over iliac crest autograft

in terms of bone substitution for effectively treating (AIS) adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

2 | P a g e

Introduction and Background

Spinal fusion interventions require the systematic utilization of various ceramic

products attributing to β TCP, hydroxypartite, healos and calcium sulphate. The lumbar

spinal fusion interventions evidentially utilize ICBG (iliac crest bone graft) while undertaking

the process of joints arthrodesis (Vaz, et al., 2010). Alternatively, TCP (tricalcium phosphate)

and HA (hydroxyapatite) are also utilized in spinal fusion process due to their proven healing

characteristics (Pugely, Petersen, DeVries-Watson, & Fredericks, 2017). Evidence-based

clinical literature advocates the influence of bone graft quality on the pattern of surgically

induced spinal fusion (McGuire, Pilcher, & Dettori, 2011). The quality and configuration of

bone graft (in spinal fusion surgeries) is of paramount importance in terms of reducing the

occurrence of surgical complications and associated adverse clinical manifestations in the

treated patients (Nouh, 2012). β TCP (beta-tricalcium phosphate) is regarded as a significant

bone substitute that facilitates the formation of bone structure through the process of

osteoclast-mediated resorption (Tanaka, et al., 2017). Therefore, β TCP substitute is utilized

in various spinal fusion interventions with the objective of facilitating the regeneration of

cortical bone. Porous titanium is a bioactive metal that is evidentially utilized in configuring

bone grafts while undertaking complex spinal fusion interventions in the context of its

elevated bone bonding capacity. The alloy of titanium undergoes thermal and chemical

surface treatment to facilitate its active transformation to a bioactive material (Fujibayashi, et

al., 2011). This bioactive intervention substantially elevates the fusion capacity of titanium

implant during spinal fusion interventions. However, the research intervention by

(Ilharreborde , et al., 2008) indicates the elevated capacity and cost effectiveness of bioactive

glass (compared to other ceramic products) in terms of facilitating spinal fusion undertaken to

treat the pattern of idiopathic scoliosis. Bioactive glass is preferred over iliac crest autograft

in terms of bone substitution for effectively treating (AIS) adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

2 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3 | P a g e

(Ilharreborde , et al., 2008). The bioactive glass intervention leads to the long-term correction

of AIS in comparison to other ceramic interventions. Bioactive glass exhibits osteoconductive

activity that leads to the establishment of bone fusion outcomes after spinal interventions

(Miyazaki, Tsumura, Wang, & Alanay, 2009). Bioactive glass when integrated with other

osteoinductive and osteogenic agents leads to the substantial enhancement of bone fusion

activity. Bioactive glass proves to be versatile in terms of its handling and utilization while

undertaking spinal fusion interventions (Pugley, Petersen, DeVries-Watson, & Fredericks,

2017). The hydration of the bioactive glass strips through bone marrow aspirate and

subsequent integration with the autograft enhances autoconduction, facilitates the process of

cell attachment and induces the generation of osseous tissue for correcting the bony

deformities of the spine (Pugely , Petersen , DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). These

findings confirm the potential of bioactive glass in terms of facilitating the extension of bone

graft warranted for inducing posterolateral spinal fusion. Furthermore, bioactive glass

intervention accelerates the rate of spinal fusion and promotes the pattern of 100% healing of

the quality and quantity of bone that any autograft group could generate after spinal fusion

surgery (Pugely, Petersen, DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). These evidence-based

facts indicate the elevated potential of bioactive glass ceramic product in terms of enhancing

the quality, pace and long-term outcomes of spinal fusion intervention. The osteostimulative

property of bioactive glass makes it a promising candidate requiring utilization in terms of a

bone graft substitute for treating the pattern of spinal osteomyelitis. Bioactive glass does not

produce ectopic bone while facilitating spinal fusion and facilitates the generation of new

orthotopic bone (Gestel, et al., 2015). The systematic implantation of bioactive glass leads to

the formation of the layer of calcium phosphate over its surface (after the sustained exposure

to the body fluid). Eventually, the glass surface layer releases phosphate, calcium, silica and

sodium ions that substantially increases osmotic pressure and localized pH (Gestel, et al.,

3 | P a g e

(Ilharreborde , et al., 2008). The bioactive glass intervention leads to the long-term correction

of AIS in comparison to other ceramic interventions. Bioactive glass exhibits osteoconductive

activity that leads to the establishment of bone fusion outcomes after spinal interventions

(Miyazaki, Tsumura, Wang, & Alanay, 2009). Bioactive glass when integrated with other

osteoinductive and osteogenic agents leads to the substantial enhancement of bone fusion

activity. Bioactive glass proves to be versatile in terms of its handling and utilization while

undertaking spinal fusion interventions (Pugley, Petersen, DeVries-Watson, & Fredericks,

2017). The hydration of the bioactive glass strips through bone marrow aspirate and

subsequent integration with the autograft enhances autoconduction, facilitates the process of

cell attachment and induces the generation of osseous tissue for correcting the bony

deformities of the spine (Pugely , Petersen , DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). These

findings confirm the potential of bioactive glass in terms of facilitating the extension of bone

graft warranted for inducing posterolateral spinal fusion. Furthermore, bioactive glass

intervention accelerates the rate of spinal fusion and promotes the pattern of 100% healing of

the quality and quantity of bone that any autograft group could generate after spinal fusion

surgery (Pugely, Petersen, DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). These evidence-based

facts indicate the elevated potential of bioactive glass ceramic product in terms of enhancing

the quality, pace and long-term outcomes of spinal fusion intervention. The osteostimulative

property of bioactive glass makes it a promising candidate requiring utilization in terms of a

bone graft substitute for treating the pattern of spinal osteomyelitis. Bioactive glass does not

produce ectopic bone while facilitating spinal fusion and facilitates the generation of new

orthotopic bone (Gestel, et al., 2015). The systematic implantation of bioactive glass leads to

the formation of the layer of calcium phosphate over its surface (after the sustained exposure

to the body fluid). Eventually, the glass surface layer releases phosphate, calcium, silica and

sodium ions that substantially increases osmotic pressure and localized pH (Gestel, et al.,

3 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4 | P a g e

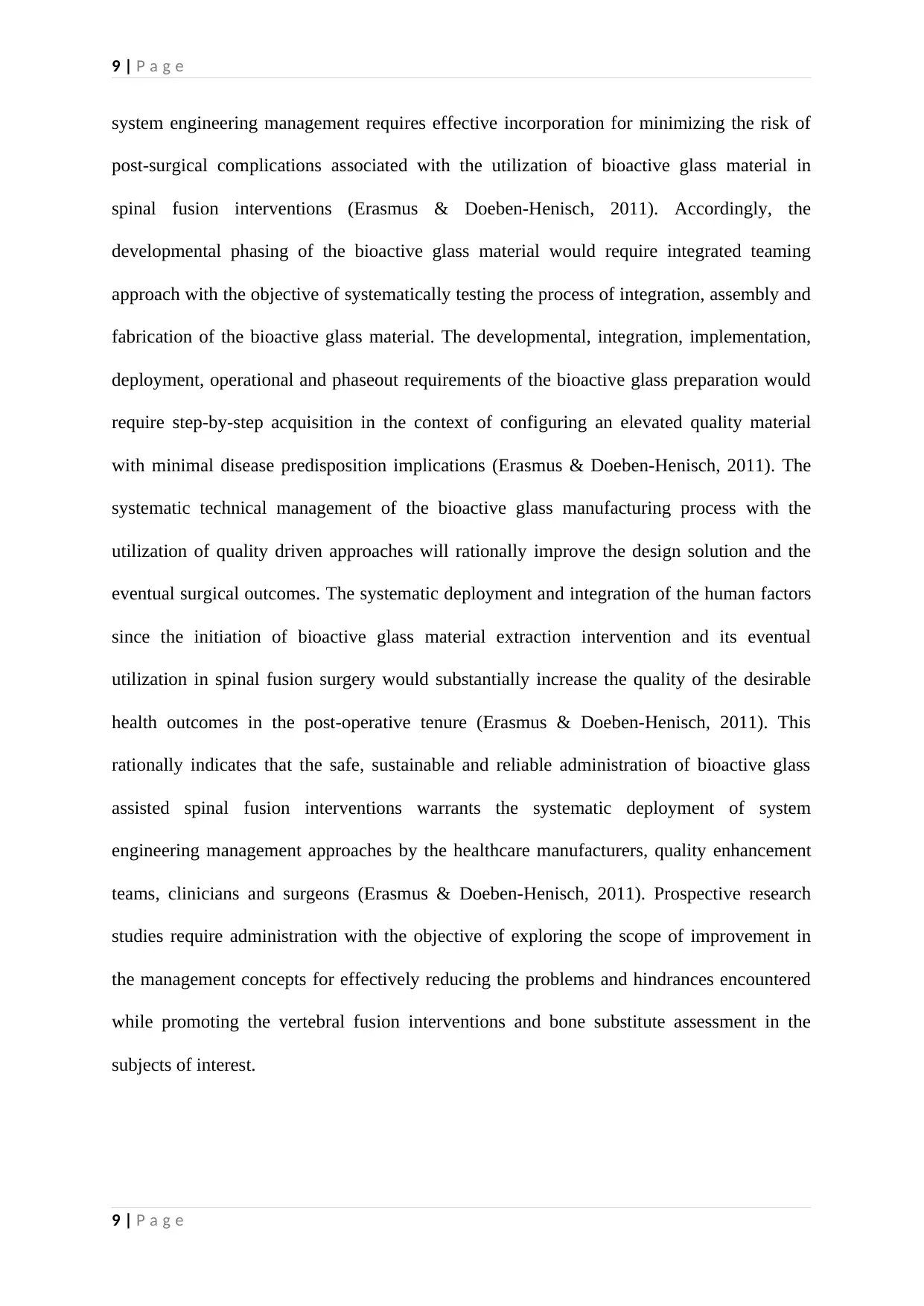

2015). The layer of silica gel then gradually deposits on the glass surface layer and

precipitated under the influence of amorphous calcium phosphate. The eventual

crystallization of these amorphous substitutes to the pattern of natural hydroxyapatite leads to

the development of osteoblasts that facilitate the generation of the new bone (Gestel, et al.,

2015). The antibacterial and angiogenetic properties of the bioactive glass make this

biomaterial a suitable choice for undertaking spinal interventions.

Bioactive glass based spinal interventions management – An evidence based analysis

The pattern of post-operative spinal infections potentially hinders the after-

management of spinal fusion interventions in the clinical setting (Hedge, Meredith, Kepler, &

Huang, 2012). The invasion of the spinal fusion site by MRSA (methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus) leads to the development of clinical complications that eventually

facilitate the development of spinal stability and substantial reversal of the deformity

correction (Hedge, Meredith, Kepler, & Huang, 2012). However, the utilization of bioactive

glass (S53P4 model) leads to the reduced predisposition of the spinal surgery candidate in

terms of developing the infectious processes at the site of surgery in the post-operative tenure

(Lindfors , et al., 2017). The bone bonding and antibacterial properties of bioactive glass

elevate its potential in terms of reducing the scope of infection development after spinal

fusion. The angiogenetic potential of the bioactive glass attributes to its property of

generating fibrous tissue that subsequently facilitates the formation of vasculature at the

desirable bone locations (Drago, et al., 2013). The osteoproductive property of bioactive glass

assists in the generation of bone matrix, osteogenic cells differentiation, replication and

migration. The utilization of the isolated autograft bone for undertaking anterior cervical

fusion leads to the sustained reduction in the rate of spinal fusion during the initial 3-6

months (Fischer, et al., 2013). This leads to the establishment of spinal instability until the

development of 100% fusion at the site of spinal intervention. Contrarily, bioactive glass

4 | P a g e

2015). The layer of silica gel then gradually deposits on the glass surface layer and

precipitated under the influence of amorphous calcium phosphate. The eventual

crystallization of these amorphous substitutes to the pattern of natural hydroxyapatite leads to

the development of osteoblasts that facilitate the generation of the new bone (Gestel, et al.,

2015). The antibacterial and angiogenetic properties of the bioactive glass make this

biomaterial a suitable choice for undertaking spinal interventions.

Bioactive glass based spinal interventions management – An evidence based analysis

The pattern of post-operative spinal infections potentially hinders the after-

management of spinal fusion interventions in the clinical setting (Hedge, Meredith, Kepler, &

Huang, 2012). The invasion of the spinal fusion site by MRSA (methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus) leads to the development of clinical complications that eventually

facilitate the development of spinal stability and substantial reversal of the deformity

correction (Hedge, Meredith, Kepler, & Huang, 2012). However, the utilization of bioactive

glass (S53P4 model) leads to the reduced predisposition of the spinal surgery candidate in

terms of developing the infectious processes at the site of surgery in the post-operative tenure

(Lindfors , et al., 2017). The bone bonding and antibacterial properties of bioactive glass

elevate its potential in terms of reducing the scope of infection development after spinal

fusion. The angiogenetic potential of the bioactive glass attributes to its property of

generating fibrous tissue that subsequently facilitates the formation of vasculature at the

desirable bone locations (Drago, et al., 2013). The osteoproductive property of bioactive glass

assists in the generation of bone matrix, osteogenic cells differentiation, replication and

migration. The utilization of the isolated autograft bone for undertaking anterior cervical

fusion leads to the sustained reduction in the rate of spinal fusion during the initial 3-6

months (Fischer, et al., 2013). This leads to the establishment of spinal instability until the

development of 100% fusion at the site of spinal intervention. Contrarily, bioactive glass

4 | P a g e

5 | P a g e

material utilization leads to the elevation in spinal fusion rate within 4-8 weeks of the surgical

intervention (Pugely , Petersen , DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). Pre-clinical studies

indicate the high potential of Bioactive glass in terms of accomplishing the cavitary defects

through the elevated generation of osteoblasts. However, bioactive glass generates a lower

quantity of osteocytes in comparison to the autograft (Camargo, Baptista, Natalino, &

Camargo, 2015). The elevated absorbance of bioactive glass at the site of spinal fusion makes

it as a biomaterial of choice since its systematic utilization leads to the elimination of the

entire glass ceramics from the fused spine during the post-operative tenure (Lee, et al., 2014).

This elimination occurs due to high biocompatibility, resorbing property and

osteoconductivity of bioactive glass material. The elevated tensile strength of the fusion

masses attained with the utilization of bioactive glass reduces the risk of clinical

complications in the fused vertebral region during the post-surgical tenure (Lee, et al., 2014).

The spinal cord pain management theory advocates the requirement of undertaking

spinal cord stimulation with the objective of reducing the intensity of chronic spinal pain

(Jeon, 2012). This pain management intervention is also recommended in cases where spinal

implant requires removal after acquiring the desirable fusion outcome (Song, Popescu, & Bell

, 2014). The pattern of spinal pain might occur in terms of a mechanical complication of the

spinal implant. However, the elements of the biodegradable bioactive glass do not contribute

to the pain pattern because of their high dissolution property. The ceramic products

(including bioactive glass) prove to be the bone extenders under the sustained influence of a

local bone graft (Nickoli & Hsu, 2014). Bioactive glass continues to extend the lumbar spine

at the fusion area under the influence of an osteoinductive stimulus while minimizing the

scope of post-operative spinal complications. The systematic utilization of bioactive glass in

the process of posterior spondylodesis leads to the generation of new bone across the

transverse processes of the fused location. The pattern of solid spinal fusion is further

5 | P a g e

material utilization leads to the elevation in spinal fusion rate within 4-8 weeks of the surgical

intervention (Pugely , Petersen , DeVries-Watson , & Fredericks , 2017). Pre-clinical studies

indicate the high potential of Bioactive glass in terms of accomplishing the cavitary defects

through the elevated generation of osteoblasts. However, bioactive glass generates a lower

quantity of osteocytes in comparison to the autograft (Camargo, Baptista, Natalino, &

Camargo, 2015). The elevated absorbance of bioactive glass at the site of spinal fusion makes

it as a biomaterial of choice since its systematic utilization leads to the elimination of the

entire glass ceramics from the fused spine during the post-operative tenure (Lee, et al., 2014).

This elimination occurs due to high biocompatibility, resorbing property and

osteoconductivity of bioactive glass material. The elevated tensile strength of the fusion

masses attained with the utilization of bioactive glass reduces the risk of clinical

complications in the fused vertebral region during the post-surgical tenure (Lee, et al., 2014).

The spinal cord pain management theory advocates the requirement of undertaking

spinal cord stimulation with the objective of reducing the intensity of chronic spinal pain

(Jeon, 2012). This pain management intervention is also recommended in cases where spinal

implant requires removal after acquiring the desirable fusion outcome (Song, Popescu, & Bell

, 2014). The pattern of spinal pain might occur in terms of a mechanical complication of the

spinal implant. However, the elements of the biodegradable bioactive glass do not contribute

to the pain pattern because of their high dissolution property. The ceramic products

(including bioactive glass) prove to be the bone extenders under the sustained influence of a

local bone graft (Nickoli & Hsu, 2014). Bioactive glass continues to extend the lumbar spine

at the fusion area under the influence of an osteoinductive stimulus while minimizing the

scope of post-operative spinal complications. The systematic utilization of bioactive glass in

the process of posterior spondylodesis leads to the generation of new bone across the

transverse processes of the fused location. The pattern of solid spinal fusion is further

5 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6 | P a g e

affirmed radiologically by the CT intervention in limited case scenarios, the remnants of the

bioactive glass remain embedded on the surface of the cancellous spinal bone after the

process of spinal surgical fusion intervention. However, no substantial evidence of spinal

fusion complications under the influence of bioactive glass remnants recorded in evidence

based clinical literature. Evidence-based research literature reports multiple benefits of

utilizing bioactive material as a stand-alone graft in spinal fusion interventions. The

utilization of bioactive material in the intertransverse vertebral space leads to 95% correction

of the vertebral spinal location (as emphasized by the findings in evidence-based clinical

literature) (Rantakokko, et al., 2012). The research literature has not revealed any evidence

regarding the predisposition of the candidates of spinal fusion in terms of acquiring the

debilitating disease outcomes attributing to feline leukemia, hepatitis virus, human

immunodeficiency virus and other virally transmitted diseases (Rantakokko, et al., 2012).

Evidence-based research literature does not recommend the sterilization, freeze drying or

freezing of the of the allograft bone (generated through bioactive material) with the objective

of retaining its osteoconductive and osteoinductive capacity (Rantakokko, et al., 2012).

Spinal fusion intervention evidentially increases the risk of the treated patients in terms of

acquiring adjacent segment disease and associated junctional spinal stenosis (Saavedra-Pozo,

Deusdara, & Benzel, 2014). The research professionals require undertaking prospective study

interventions with the objective of determining the possible change in bioactive glass

utilization methodology in spinal fusion interventions warranted for reducing the scope of

occurrence of post-operative spinal complications (including ASD and spinal stenosis). a

implantation of bioactive glass assisted hard tissue prosthesis in various spinal fusion

interventions brings excellent clinical outcomes. The porous biomaterial of the bioactive

glass assists in the fixation of the prosthetic device across the vertebral region (Krishnan &

Lakshmi, 2013). The extracellular elements of the bioactive glass lead facilitate an excellent

6 | P a g e

affirmed radiologically by the CT intervention in limited case scenarios, the remnants of the

bioactive glass remain embedded on the surface of the cancellous spinal bone after the

process of spinal surgical fusion intervention. However, no substantial evidence of spinal

fusion complications under the influence of bioactive glass remnants recorded in evidence

based clinical literature. Evidence-based research literature reports multiple benefits of

utilizing bioactive material as a stand-alone graft in spinal fusion interventions. The

utilization of bioactive material in the intertransverse vertebral space leads to 95% correction

of the vertebral spinal location (as emphasized by the findings in evidence-based clinical

literature) (Rantakokko, et al., 2012). The research literature has not revealed any evidence

regarding the predisposition of the candidates of spinal fusion in terms of acquiring the

debilitating disease outcomes attributing to feline leukemia, hepatitis virus, human

immunodeficiency virus and other virally transmitted diseases (Rantakokko, et al., 2012).

Evidence-based research literature does not recommend the sterilization, freeze drying or

freezing of the of the allograft bone (generated through bioactive material) with the objective

of retaining its osteoconductive and osteoinductive capacity (Rantakokko, et al., 2012).

Spinal fusion intervention evidentially increases the risk of the treated patients in terms of

acquiring adjacent segment disease and associated junctional spinal stenosis (Saavedra-Pozo,

Deusdara, & Benzel, 2014). The research professionals require undertaking prospective study

interventions with the objective of determining the possible change in bioactive glass

utilization methodology in spinal fusion interventions warranted for reducing the scope of

occurrence of post-operative spinal complications (including ASD and spinal stenosis). a

implantation of bioactive glass assisted hard tissue prosthesis in various spinal fusion

interventions brings excellent clinical outcomes. The porous biomaterial of the bioactive

glass assists in the fixation of the prosthetic device across the vertebral region (Krishnan &

Lakshmi, 2013). The extracellular elements of the bioactive glass lead facilitate an excellent

6 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7 | P a g e

movement of nutrients, vascularity as well as cell occupancy. However, the utilization of

bioactive glass matrix in spinal fusion interventions does not reduce the risk of the corrected

spine in terms of acquiring spinal fractures under stressful conditions (Krishnan & Lakshmi,

2013). Therefore, the clinicians and research professionals require undertaking prospective

research interventions with the objective of developing innovative bone matrix preparation

strategies for reducing the risk of occurrence of spinal fractures following their corrective

fusion interventions.

Data collection methods

The systematic study data regarding bioactive glass material was sequentially

retrieved through PubMed, Cochrane and Research Gate for its evidence-based analysis. The

following search term pattern was utilized for selecting the articles of interest that included

the pattern of systematic, observatory as well as quantitative research interventions. Indeed,

out of 456 selected research interventions, 6 studies that appropriately matched with the

subject of interest were selected and analysed for retrieving the evidence-based findings.

1. “Bioactive glass” and spinal fusion”

2. “Bioactive glass” or “ceramic products”

3. “β TCP” and “Bioactive glass” and “spinal fusion”

4. “Hydroxypartite” and “Bioactive glass” and “spinal fusion”

5. Healos” and Bioactive glass” and spinal fusion”

6. Bioactive glass” and orthopaedic surgery”

7. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fusion management”

8. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fusion” and bone substitute”

9. Bioactive glass” and intervertebral regeneration”

10. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fractures”

11. Bioactive glass management”

7 | P a g e

movement of nutrients, vascularity as well as cell occupancy. However, the utilization of

bioactive glass matrix in spinal fusion interventions does not reduce the risk of the corrected

spine in terms of acquiring spinal fractures under stressful conditions (Krishnan & Lakshmi,

2013). Therefore, the clinicians and research professionals require undertaking prospective

research interventions with the objective of developing innovative bone matrix preparation

strategies for reducing the risk of occurrence of spinal fractures following their corrective

fusion interventions.

Data collection methods

The systematic study data regarding bioactive glass material was sequentially

retrieved through PubMed, Cochrane and Research Gate for its evidence-based analysis. The

following search term pattern was utilized for selecting the articles of interest that included

the pattern of systematic, observatory as well as quantitative research interventions. Indeed,

out of 456 selected research interventions, 6 studies that appropriately matched with the

subject of interest were selected and analysed for retrieving the evidence-based findings.

1. “Bioactive glass” and spinal fusion”

2. “Bioactive glass” or “ceramic products”

3. “β TCP” and “Bioactive glass” and “spinal fusion”

4. “Hydroxypartite” and “Bioactive glass” and “spinal fusion”

5. Healos” and Bioactive glass” and spinal fusion”

6. Bioactive glass” and orthopaedic surgery”

7. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fusion management”

8. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fusion” and bone substitute”

9. Bioactive glass” and intervertebral regeneration”

10. Bioactive glass” and vertebral fractures”

11. Bioactive glass management”

7 | P a g e

8 | P a g e

12. Bioactive glass” and intervertebral complications”

Results

The findings of the evaluated research interventions confirm the elevated capacity of

bioactive glass in terms of facilitating the process of spinal surgical fusion. The minimum

post-operative complications that the surgery candidates experience after spinal fusion

(because of the effective utilization of bioactive glass) makes it as a material of choice for

undertaking corrective interventions of the human spine. The findings of the presented

systematic analysis were rationally authenticated with the systematic utilization of the CASP

tool. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) is indeed regarded as an evidence-based

tool warranting utilization for the systematic assessment for the methodological quality and

results of numerous research interventions (Zeng, et al., 2015). The study review addressed a

focussed research question (related to bioactive material utilization and its comparative

analysis with other ceramic products) and research papers of the selected subject were

evidentially explored for generating the desirable study outcomes. The irrelevant studies were

summarily excluded from the research interventions. The precision of the study results

appeared precise, rational unless and otherwise negated by the findings of the prospective

research interventions.

Discussion

The evidence-based findings regarding the utilization of bioactive glass in spinal

fusion interventions indicate its potential in terms of intervertebral bone generation and

facilitation of the healing process during the post-operative period. However, the utilization

of bioactive glass does not effectively subside the entire risks associated with spinal

interventions related outcomes. For example, no concrete methodology exists for effectively

reducing the risk of occurrence of spinal fractures (during post-operative period) under the

influence of weak tensile strength of the bioactive glass material. Therefore, the concept of

8 | P a g e

12. Bioactive glass” and intervertebral complications”

Results

The findings of the evaluated research interventions confirm the elevated capacity of

bioactive glass in terms of facilitating the process of spinal surgical fusion. The minimum

post-operative complications that the surgery candidates experience after spinal fusion

(because of the effective utilization of bioactive glass) makes it as a material of choice for

undertaking corrective interventions of the human spine. The findings of the presented

systematic analysis were rationally authenticated with the systematic utilization of the CASP

tool. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) is indeed regarded as an evidence-based

tool warranting utilization for the systematic assessment for the methodological quality and

results of numerous research interventions (Zeng, et al., 2015). The study review addressed a

focussed research question (related to bioactive material utilization and its comparative

analysis with other ceramic products) and research papers of the selected subject were

evidentially explored for generating the desirable study outcomes. The irrelevant studies were

summarily excluded from the research interventions. The precision of the study results

appeared precise, rational unless and otherwise negated by the findings of the prospective

research interventions.

Discussion

The evidence-based findings regarding the utilization of bioactive glass in spinal

fusion interventions indicate its potential in terms of intervertebral bone generation and

facilitation of the healing process during the post-operative period. However, the utilization

of bioactive glass does not effectively subside the entire risks associated with spinal

interventions related outcomes. For example, no concrete methodology exists for effectively

reducing the risk of occurrence of spinal fractures (during post-operative period) under the

influence of weak tensile strength of the bioactive glass material. Therefore, the concept of

8 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9 | P a g e

system engineering management requires effective incorporation for minimizing the risk of

post-surgical complications associated with the utilization of bioactive glass material in

spinal fusion interventions (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). Accordingly, the

developmental phasing of the bioactive glass material would require integrated teaming

approach with the objective of systematically testing the process of integration, assembly and

fabrication of the bioactive glass material. The developmental, integration, implementation,

deployment, operational and phaseout requirements of the bioactive glass preparation would

require step-by-step acquisition in the context of configuring an elevated quality material

with minimal disease predisposition implications (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). The

systematic technical management of the bioactive glass manufacturing process with the

utilization of quality driven approaches will rationally improve the design solution and the

eventual surgical outcomes. The systematic deployment and integration of the human factors

since the initiation of bioactive glass material extraction intervention and its eventual

utilization in spinal fusion surgery would substantially increase the quality of the desirable

health outcomes in the post-operative tenure (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). This

rationally indicates that the safe, sustainable and reliable administration of bioactive glass

assisted spinal fusion interventions warrants the systematic deployment of system

engineering management approaches by the healthcare manufacturers, quality enhancement

teams, clinicians and surgeons (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). Prospective research

studies require administration with the objective of exploring the scope of improvement in

the management concepts for effectively reducing the problems and hindrances encountered

while promoting the vertebral fusion interventions and bone substitute assessment in the

subjects of interest.

9 | P a g e

system engineering management requires effective incorporation for minimizing the risk of

post-surgical complications associated with the utilization of bioactive glass material in

spinal fusion interventions (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). Accordingly, the

developmental phasing of the bioactive glass material would require integrated teaming

approach with the objective of systematically testing the process of integration, assembly and

fabrication of the bioactive glass material. The developmental, integration, implementation,

deployment, operational and phaseout requirements of the bioactive glass preparation would

require step-by-step acquisition in the context of configuring an elevated quality material

with minimal disease predisposition implications (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). The

systematic technical management of the bioactive glass manufacturing process with the

utilization of quality driven approaches will rationally improve the design solution and the

eventual surgical outcomes. The systematic deployment and integration of the human factors

since the initiation of bioactive glass material extraction intervention and its eventual

utilization in spinal fusion surgery would substantially increase the quality of the desirable

health outcomes in the post-operative tenure (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). This

rationally indicates that the safe, sustainable and reliable administration of bioactive glass

assisted spinal fusion interventions warrants the systematic deployment of system

engineering management approaches by the healthcare manufacturers, quality enhancement

teams, clinicians and surgeons (Erasmus & Doeben-Henisch, 2011). Prospective research

studies require administration with the objective of exploring the scope of improvement in

the management concepts for effectively reducing the problems and hindrances encountered

while promoting the vertebral fusion interventions and bone substitute assessment in the

subjects of interest.

9 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10 | P a g e

10 | P a g e

10 | P a g e

11 | P a g e

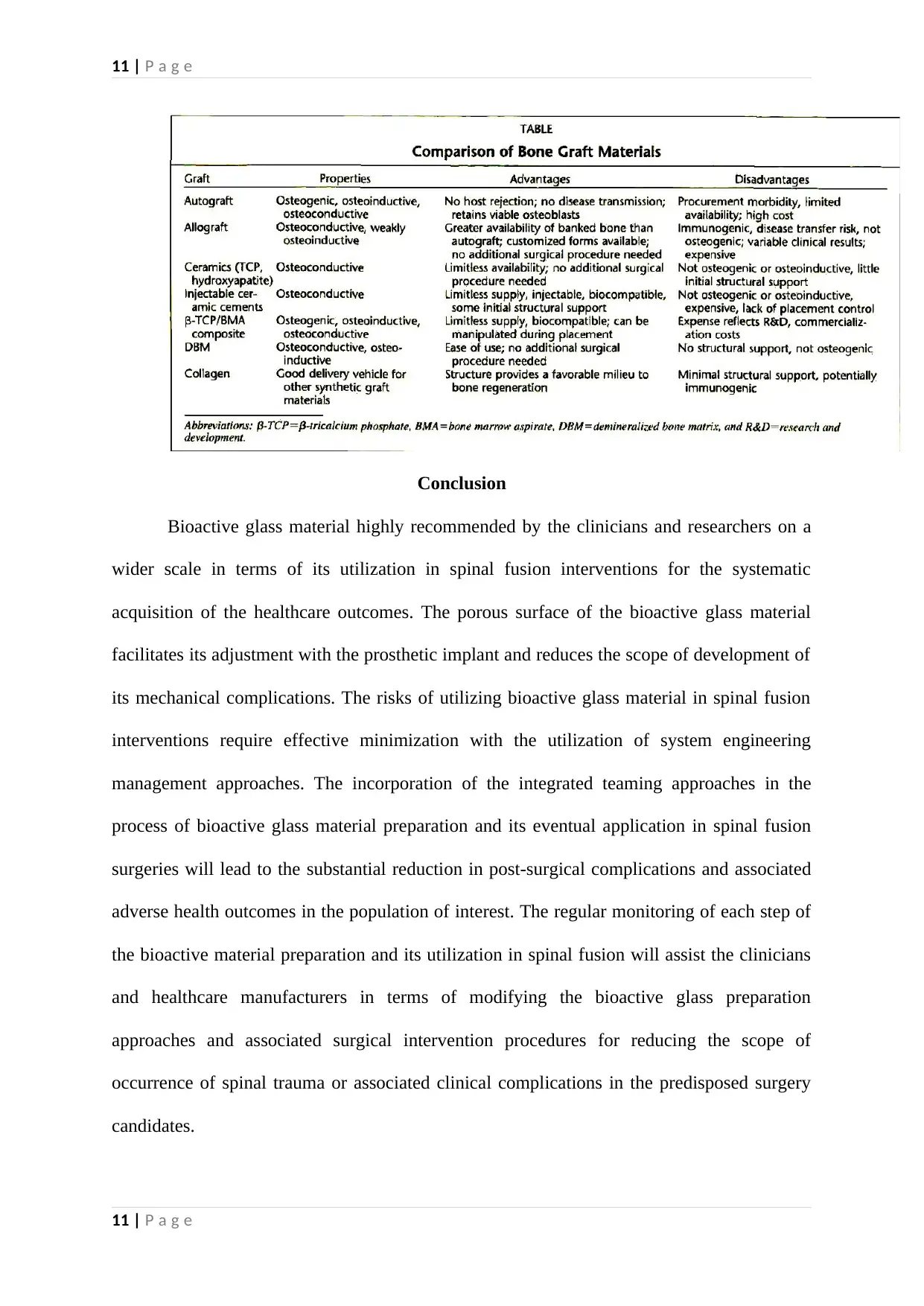

Conclusion

Bioactive glass material highly recommended by the clinicians and researchers on a

wider scale in terms of its utilization in spinal fusion interventions for the systematic

acquisition of the healthcare outcomes. The porous surface of the bioactive glass material

facilitates its adjustment with the prosthetic implant and reduces the scope of development of

its mechanical complications. The risks of utilizing bioactive glass material in spinal fusion

interventions require effective minimization with the utilization of system engineering

management approaches. The incorporation of the integrated teaming approaches in the

process of bioactive glass material preparation and its eventual application in spinal fusion

surgeries will lead to the substantial reduction in post-surgical complications and associated

adverse health outcomes in the population of interest. The regular monitoring of each step of

the bioactive material preparation and its utilization in spinal fusion will assist the clinicians

and healthcare manufacturers in terms of modifying the bioactive glass preparation

approaches and associated surgical intervention procedures for reducing the scope of

occurrence of spinal trauma or associated clinical complications in the predisposed surgery

candidates.

11 | P a g e

Conclusion

Bioactive glass material highly recommended by the clinicians and researchers on a

wider scale in terms of its utilization in spinal fusion interventions for the systematic

acquisition of the healthcare outcomes. The porous surface of the bioactive glass material

facilitates its adjustment with the prosthetic implant and reduces the scope of development of

its mechanical complications. The risks of utilizing bioactive glass material in spinal fusion

interventions require effective minimization with the utilization of system engineering

management approaches. The incorporation of the integrated teaming approaches in the

process of bioactive glass material preparation and its eventual application in spinal fusion

surgeries will lead to the substantial reduction in post-surgical complications and associated

adverse health outcomes in the population of interest. The regular monitoring of each step of

the bioactive material preparation and its utilization in spinal fusion will assist the clinicians

and healthcare manufacturers in terms of modifying the bioactive glass preparation

approaches and associated surgical intervention procedures for reducing the scope of

occurrence of spinal trauma or associated clinical complications in the predisposed surgery

candidates.

11 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 17

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.