Detailed Analysis: Cranial Nerves and Animal Behavior in Biology

VerifiedAdded on 2021/08/19

|18

|5937

|155

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This biology assignment delves into three key areas: the functions of cranial nerves, social organization in insects, and the importance of animal behavior in ecosystems. The assignment begins by detailing the functions of six pairs of cranial nerves, including the olfactory, optic, oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal, and abducens nerves, explaining their roles in sensory perception and motor control. It then explores the social organization of insects, using termites and bees as examples, highlighting their colony structures, division of labor, and unique adaptations. Finally, the assignment emphasizes the critical role of animal behavior in ecosystems, discussing its influence on biological adaptations, interactions with the environment, and contributions to human understanding of behavior, neurobiology, and societal issues.

Question # 02: Explain the functions of any 06 pairs of cranial nerves.

Your cranial nerves are pairs of nerves that connect your brain to different parts of your head,

neck, and trunk. There are 12 of them, each named for their function or structure.

Each nerve also has a corresponding Roman numeral between I and XII. This is based off their

location from front to back. For example, your olfactory nerve is closest to the front of your

head, so it’s designated as I.

I. Olfactory nerve

The olfactory nerve transmits sensory information to your brain regarding smells that you

encounter. When you inhale aromatic molecules, they dissolve in a moist lining at the roof of

your nasal cavity, called the olfactory epithelium. This stimulates receptors that generate nerve

impulses that move to your olfactory bulb. Your olfactory bulb is an oval-shaped structure that

contains specialized groups of nerve cells.

From the olfactory bulb, nerves pass into your olfactory tract, which is located below the frontal

lobe of your brain. Nerve signals are then sent to areas of your brain concerned with memory and

recognition of smells.

II. Optic nerve

The optic nerve is the sensory nerve that involves vision.

When light enters your eye, it comes into contact with special receptors in your retina called rods

and cones. Rods are found in large numbers and are highly sensitive to light. They’re more

specialized for black and white or night vision. Cones are present in smaller numbers. They have

a lower light sensitivity than rods and are more involved with color vision. The information

received by your rods and cones is transmitted from your retina to your optic nerve. Once inside

your skull, both of your optic nerves meet to form something called the optic chiasm. At the

optic chiasm, nerve fibers from half of each retina form two separate optic tracts. Through each

optic tract, the nerve impulses eventually reach your visual cortex, which then processes the

information. Your visual cortex is located in the back part of your brain.

III. Oculomotor nerve

The oculomotor nerve has two different motor functions: muscle function and pupil response.

Muscle function. Your oculomotor nerve provides motor function to four of the six muscles

around your eyes. These muscles help your eyes move and focus on objects. Pupil response. It

also helps to control the size of your pupil as it responds to light. This nerve originates in the

Your cranial nerves are pairs of nerves that connect your brain to different parts of your head,

neck, and trunk. There are 12 of them, each named for their function or structure.

Each nerve also has a corresponding Roman numeral between I and XII. This is based off their

location from front to back. For example, your olfactory nerve is closest to the front of your

head, so it’s designated as I.

I. Olfactory nerve

The olfactory nerve transmits sensory information to your brain regarding smells that you

encounter. When you inhale aromatic molecules, they dissolve in a moist lining at the roof of

your nasal cavity, called the olfactory epithelium. This stimulates receptors that generate nerve

impulses that move to your olfactory bulb. Your olfactory bulb is an oval-shaped structure that

contains specialized groups of nerve cells.

From the olfactory bulb, nerves pass into your olfactory tract, which is located below the frontal

lobe of your brain. Nerve signals are then sent to areas of your brain concerned with memory and

recognition of smells.

II. Optic nerve

The optic nerve is the sensory nerve that involves vision.

When light enters your eye, it comes into contact with special receptors in your retina called rods

and cones. Rods are found in large numbers and are highly sensitive to light. They’re more

specialized for black and white or night vision. Cones are present in smaller numbers. They have

a lower light sensitivity than rods and are more involved with color vision. The information

received by your rods and cones is transmitted from your retina to your optic nerve. Once inside

your skull, both of your optic nerves meet to form something called the optic chiasm. At the

optic chiasm, nerve fibers from half of each retina form two separate optic tracts. Through each

optic tract, the nerve impulses eventually reach your visual cortex, which then processes the

information. Your visual cortex is located in the back part of your brain.

III. Oculomotor nerve

The oculomotor nerve has two different motor functions: muscle function and pupil response.

Muscle function. Your oculomotor nerve provides motor function to four of the six muscles

around your eyes. These muscles help your eyes move and focus on objects. Pupil response. It

also helps to control the size of your pupil as it responds to light. This nerve originates in the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

front part of your midbrain, which is a part of your brainstem. It moves forward from that area

until it reaches the area of your eye sockets.

IV. Trochlear nerve

The trochlear nerve controls your superior oblique muscle. This is the muscle that’s responsible

for downward, outward, and inward eye movements. It emerges from the back part of your

midbrain. Like your oculomotor nerve, it moves forward until it reaches your eye sockets, where

it stimulates the superior oblique muscle.

V. Trigeminal nerve

The trigeminal nerve is the largest of your cranial nerves and has both sensory and motor

functions.

The trigeminal nerve has three divisions, which are:

Ophthalmic. The ophthalmic division sends sensory information from the upper part of your

face, including your forehead, scalp, and upper eyelids.

Maxillary. This division communicates sensory information from the middle part of your face,

including your cheeks, upper lip, and nasal cavity.

Mandibular. The mandibular division has both a sensory and a motor function. It sends sensory

information from your ears, lower lip, and chin. It also controls the movement of muscles within

your jaw and ear.

The trigeminal nerve originates from a group of nuclei — which is a collection of nerve cells —

in the midbrain and medulla regions of your brainstem. Eventually, these nuclei form a separate

sensory root and motor root. The sensory root of your trigeminal nerve branches into the

ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular divisions. The motor root of your trigeminal nerve passes

below the sensory root and is only distributed into the mandibular division.

VI. Abducens nerve

The abducens nerve controls another muscle that’s associated with eye movement, called

the lateral rectus muscle. This muscle is involved in outward eye movement. For example, you

would use it to look to the side. This nerve, also called the abducent nerve, starts in

the pons region of your brainstem. It eventually enters your eye socket, where it controls the

lateral rectus muscle.

Q# 3 Explain social organization in insects with examples.

until it reaches the area of your eye sockets.

IV. Trochlear nerve

The trochlear nerve controls your superior oblique muscle. This is the muscle that’s responsible

for downward, outward, and inward eye movements. It emerges from the back part of your

midbrain. Like your oculomotor nerve, it moves forward until it reaches your eye sockets, where

it stimulates the superior oblique muscle.

V. Trigeminal nerve

The trigeminal nerve is the largest of your cranial nerves and has both sensory and motor

functions.

The trigeminal nerve has three divisions, which are:

Ophthalmic. The ophthalmic division sends sensory information from the upper part of your

face, including your forehead, scalp, and upper eyelids.

Maxillary. This division communicates sensory information from the middle part of your face,

including your cheeks, upper lip, and nasal cavity.

Mandibular. The mandibular division has both a sensory and a motor function. It sends sensory

information from your ears, lower lip, and chin. It also controls the movement of muscles within

your jaw and ear.

The trigeminal nerve originates from a group of nuclei — which is a collection of nerve cells —

in the midbrain and medulla regions of your brainstem. Eventually, these nuclei form a separate

sensory root and motor root. The sensory root of your trigeminal nerve branches into the

ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular divisions. The motor root of your trigeminal nerve passes

below the sensory root and is only distributed into the mandibular division.

VI. Abducens nerve

The abducens nerve controls another muscle that’s associated with eye movement, called

the lateral rectus muscle. This muscle is involved in outward eye movement. For example, you

would use it to look to the side. This nerve, also called the abducent nerve, starts in

the pons region of your brainstem. It eventually enters your eye socket, where it controls the

lateral rectus muscle.

Q# 3 Explain social organization in insects with examples.

In insects social life has evolved only in two orders, namely, Isoptera (termites) and

Hymenoptera (bees, wasps and ants) which make a nest and live in colonies of thousands of

individuals that practice division of labour and social interaction.

Examples:

SOCIAL LIFE IN TERMITES

Termites were the first animals which started living in colonies and developed a well organised

social system about 300 million years ago, much earlier than honey bees, ants and human beings.

Although termites do not exceed 3-4 mm in size, their queen is a 4 inch long giant that lies in the

royal chamber motionless, since its legs are too small to move its enormous body. Hence

workers have to take care of all its daily chores. Termite queen is an egg-laying machine that

reproduces at an astonishing rate of two eggs per second. Generally the queen of a termite colony

can lay 6,000 to 7,000 eggs per day, and can live for 15 to 20 years. The other

castes, workers and soldiers are highly devoted to the colony, working incessantly and tirelessly,

demanding nothing in return from the society. Soldiers have long dagger-like mandibles with

which they defend their nest and workers chew the wood to feed to the queen and larvae and

grow fungus gardens for lean periods. Nasutes are specialized soldiers which specialize in

chemical warfare. They produce a jet of highly corrosive chemical from their bodies that can

dissolve the skin of enemies and can also help in making galleries through the rocks.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF A BEE COLONY

The population of a healthy bee hive in spring and honey flow period may contain 40,000-80,000

individuals but the population declines in winter and extreme summer. There is remarkable order

in the hive and no conflicts are seen among the members. Queen is one and a half times larger

than the workers and is the only fertile female in the hive. Queen keeps the colony together by

secreting a pheromone called queen substance from its mandibular glands. In multiqueen

colonies, young queens after emergence attempt to sting and kill the rival queens.

Hymenoptera (bees, wasps and ants) which make a nest and live in colonies of thousands of

individuals that practice division of labour and social interaction.

Examples:

SOCIAL LIFE IN TERMITES

Termites were the first animals which started living in colonies and developed a well organised

social system about 300 million years ago, much earlier than honey bees, ants and human beings.

Although termites do not exceed 3-4 mm in size, their queen is a 4 inch long giant that lies in the

royal chamber motionless, since its legs are too small to move its enormous body. Hence

workers have to take care of all its daily chores. Termite queen is an egg-laying machine that

reproduces at an astonishing rate of two eggs per second. Generally the queen of a termite colony

can lay 6,000 to 7,000 eggs per day, and can live for 15 to 20 years. The other

castes, workers and soldiers are highly devoted to the colony, working incessantly and tirelessly,

demanding nothing in return from the society. Soldiers have long dagger-like mandibles with

which they defend their nest and workers chew the wood to feed to the queen and larvae and

grow fungus gardens for lean periods. Nasutes are specialized soldiers which specialize in

chemical warfare. They produce a jet of highly corrosive chemical from their bodies that can

dissolve the skin of enemies and can also help in making galleries through the rocks.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF A BEE COLONY

The population of a healthy bee hive in spring and honey flow period may contain 40,000-80,000

individuals but the population declines in winter and extreme summer. There is remarkable order

in the hive and no conflicts are seen among the members. Queen is one and a half times larger

than the workers and is the only fertile female in the hive. Queen keeps the colony together by

secreting a pheromone called queen substance from its mandibular glands. In multiqueen

colonies, young queens after emergence attempt to sting and kill the rival queens.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Question # 04: Explain the importance of animal behavior in ecosystems.

Animal behavior is the bridge between the molecular and physiological aspects of biology and

the ecological. Behavior is the link between organisms and environment and between the

nervous system, and the ecosystem. Behavior is one of the most important properties of animal

life. Behavior plays a critical role in biological adaptations. Behavior is how we humans define

our own lives. Behavior is that part of an organism by which it interacts with its environment.

Behavior is as much a part of an organisms as its coat, wings etc. The beauty of an animal

includes its behavioral attributes. For the same reasons that we study the universe and subatomic

particles there is intrinsic interest in the study of animals. In view of the amount of time that

television devotes to animal films and the amount of money that people spend on nature books

there is much more public interest in animal behavior than in neutrons and neurons. If human

curiosity drives research, then animal behavior should be near the top of our priorities.

While the study of animal behavior is important as a scientific field on its own, our science has

made important contributions to other disciplines with applications to the study of human

behavior, to the neurosciences, to the environment and resource management, to the study of

animal welfare and to the education of future generations of scientists.

A. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND HUMAN SOCIETY

1. Many problems in human society are often related to the interaction of environment and

behavior or genetics and behavior. The fields of socioecology and animal behavior deal with

the issue of environment behavioral interactions both at an evolutionary level and a

proximate level. Increasingly social scientists are turning to animal behavior as a framework

Animal behavior is the bridge between the molecular and physiological aspects of biology and

the ecological. Behavior is the link between organisms and environment and between the

nervous system, and the ecosystem. Behavior is one of the most important properties of animal

life. Behavior plays a critical role in biological adaptations. Behavior is how we humans define

our own lives. Behavior is that part of an organism by which it interacts with its environment.

Behavior is as much a part of an organisms as its coat, wings etc. The beauty of an animal

includes its behavioral attributes. For the same reasons that we study the universe and subatomic

particles there is intrinsic interest in the study of animals. In view of the amount of time that

television devotes to animal films and the amount of money that people spend on nature books

there is much more public interest in animal behavior than in neutrons and neurons. If human

curiosity drives research, then animal behavior should be near the top of our priorities.

While the study of animal behavior is important as a scientific field on its own, our science has

made important contributions to other disciplines with applications to the study of human

behavior, to the neurosciences, to the environment and resource management, to the study of

animal welfare and to the education of future generations of scientists.

A. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND HUMAN SOCIETY

1. Many problems in human society are often related to the interaction of environment and

behavior or genetics and behavior. The fields of socioecology and animal behavior deal with

the issue of environment behavioral interactions both at an evolutionary level and a

proximate level. Increasingly social scientists are turning to animal behavior as a framework

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

in which to interpret human society and to understand possible causes of societal problems.

(e.g. Daly and Wilson's book on human homicide is based on an evolutionary analysis from

animal research. Many studies on child abuse utilize theory and data from studies on

infanticide in animals.)

2. Research by de Waal on chimpanzees and monkeys has illustrated the importance of

cooperation and reconciliation in social groups. This work provides new perspectives by

which to view and ameliorate aggressive behavior among human beings.

3. The methodology applied to study animal behavior has had a tremendous impact in

psychology and the social sciences. Jean Piaget began his career with the study of snails, and

he extended the use of careful behavioral observations and descriptions to his landmark

studies on human cognitive development. J. B. Watson began his study of behavior by

observing gulls. Aspects of experimental design, observation techniques, attention to

nonverbal communication signals were often developed in animal behavior studies before

their application to studies of human behavior. The behavioral study of humans would be

much diminished today without the influence of animal research.

4. Charles Darwin's work on emotional expression in animals has had an important influence on

many psychologists, such as Paul Ekman, who study human emotional behavior.

5. Harry Harlow's work on social development in rhesus monkeys has been of major

importance to theories of child development and to psychiatry. The work of Overmier, Maier

and Seligman on learned helplessness has had a similar effect on child development and

psychiatry.

6. The comparative study of behavior over a wide range of species can provide insights into

influences affecting human behavior. For example, the woolly spider monkey in Brazil

displays no overt aggressive behavior among group members. We might learn how to

minimize human aggression if we understood how this species of monkey avoids aggression.

If we want to have human fathers be more involved in infant care, we can study the

conditions under which paternal care has appeared in other species like the California mouse

or in marmosets and tamarins. Studies of various models of the ontogeny of communication

in birds and mammals have had direct influence on the development of theories and the

research directions in the study of child language. The richness of developmental processes

(e.g. Daly and Wilson's book on human homicide is based on an evolutionary analysis from

animal research. Many studies on child abuse utilize theory and data from studies on

infanticide in animals.)

2. Research by de Waal on chimpanzees and monkeys has illustrated the importance of

cooperation and reconciliation in social groups. This work provides new perspectives by

which to view and ameliorate aggressive behavior among human beings.

3. The methodology applied to study animal behavior has had a tremendous impact in

psychology and the social sciences. Jean Piaget began his career with the study of snails, and

he extended the use of careful behavioral observations and descriptions to his landmark

studies on human cognitive development. J. B. Watson began his study of behavior by

observing gulls. Aspects of experimental design, observation techniques, attention to

nonverbal communication signals were often developed in animal behavior studies before

their application to studies of human behavior. The behavioral study of humans would be

much diminished today without the influence of animal research.

4. Charles Darwin's work on emotional expression in animals has had an important influence on

many psychologists, such as Paul Ekman, who study human emotional behavior.

5. Harry Harlow's work on social development in rhesus monkeys has been of major

importance to theories of child development and to psychiatry. The work of Overmier, Maier

and Seligman on learned helplessness has had a similar effect on child development and

psychiatry.

6. The comparative study of behavior over a wide range of species can provide insights into

influences affecting human behavior. For example, the woolly spider monkey in Brazil

displays no overt aggressive behavior among group members. We might learn how to

minimize human aggression if we understood how this species of monkey avoids aggression.

If we want to have human fathers be more involved in infant care, we can study the

conditions under which paternal care has appeared in other species like the California mouse

or in marmosets and tamarins. Studies of various models of the ontogeny of communication

in birds and mammals have had direct influence on the development of theories and the

research directions in the study of child language. The richness of developmental processes

in behavior, including multiple sources and the consequences of experience are significant in

understanding processes of human development.

7. Understanding the differences in adaptability between species that can live in a variety of

habitats versus those that are restricted to limited habitats can lead to an understanding of

how we might improve human adaptability as our environments change.

8. Research by animal behaviorists on animal sensory systems has led to practical applications

for extending human sensory systems. Griffin's demonstrations on how bats use sonar to

locate objects has led directly to the use of sonar techniques in a wide array of applications

from the military to fetal diagnostics.

9. Studies of chimpanzees using language analogues have led to new technology (computer

keyboards using arbitrary symbols) that have been applied successfully to teaching language

to disadvantaged human populations.

10. Basic research on circadian and other endogenous rhythms in animals has led to research

relevant to human factors and productivity in areas such as coping with jet-lag or changing

from one shift to another.

11. Research on animals has developed many of the important concepts relating to coping with

stress, for example studies of the importance of prediction and control on coping behavior.

B. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND NEUROBIOLOGY

1. Sir Charles Sherrington, an early Nobel Prize winner, developed a model for the structure

and function of the nervous system based only on close behavioral observation and

deduction. Seventy years of subsequent neurobiological research has completely supported

the inferences Sherrington made from behavioral observation.

2. Neuroethology, the integration of animal behavior and the neurosciences, provides important

frameworks for hypothesizing neural mechanisms. Careful behavioral data allow

neurobiologists to narrow the scope of their studies and to focus on relevant input stimuli and

attend to relevant responses. In many case the use of species specific natural stimuli has led

to new insights about neural structure and function that contrast with results obtained using

non-relevant stimuli.

3. Recent work in animal behavior has demonstrated a downward influence of behavior and

social organization on physiological and cellular processes. Variations in social environment

can inhibit or stimulate ovulation, produce menstrual synchrony, induce miscarriages and so

understanding processes of human development.

7. Understanding the differences in adaptability between species that can live in a variety of

habitats versus those that are restricted to limited habitats can lead to an understanding of

how we might improve human adaptability as our environments change.

8. Research by animal behaviorists on animal sensory systems has led to practical applications

for extending human sensory systems. Griffin's demonstrations on how bats use sonar to

locate objects has led directly to the use of sonar techniques in a wide array of applications

from the military to fetal diagnostics.

9. Studies of chimpanzees using language analogues have led to new technology (computer

keyboards using arbitrary symbols) that have been applied successfully to teaching language

to disadvantaged human populations.

10. Basic research on circadian and other endogenous rhythms in animals has led to research

relevant to human factors and productivity in areas such as coping with jet-lag or changing

from one shift to another.

11. Research on animals has developed many of the important concepts relating to coping with

stress, for example studies of the importance of prediction and control on coping behavior.

B. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND NEUROBIOLOGY

1. Sir Charles Sherrington, an early Nobel Prize winner, developed a model for the structure

and function of the nervous system based only on close behavioral observation and

deduction. Seventy years of subsequent neurobiological research has completely supported

the inferences Sherrington made from behavioral observation.

2. Neuroethology, the integration of animal behavior and the neurosciences, provides important

frameworks for hypothesizing neural mechanisms. Careful behavioral data allow

neurobiologists to narrow the scope of their studies and to focus on relevant input stimuli and

attend to relevant responses. In many case the use of species specific natural stimuli has led

to new insights about neural structure and function that contrast with results obtained using

non-relevant stimuli.

3. Recent work in animal behavior has demonstrated a downward influence of behavior and

social organization on physiological and cellular processes. Variations in social environment

can inhibit or stimulate ovulation, produce menstrual synchrony, induce miscarriages and so

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

on. Other animal studies show that the quality of the social and behavioral environment have

a direct effect on immune system functioning. Researchers in physiology and immunology

need to be guided by these behavioral and social influences to properly control their own

studies.

C. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND THE ENVIRONMENT, CONSERVATION AND

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

1. The behavior of animals often provides the first clues or early warning signs of

environmental degradation. Changes in sexual and other behavior occur much sooner and at

lower levels of environmental disruption than changes in reproductive outcomes and

population size. If we wait to see if numbers of animal populations are declining, it may be

too late to take measures to save the environment. Studies of natural behavior in the field are

vital to provide baseline data for future environmental monitoring. For example, the

Environmental Protection Agency uses disruptions in swimming behavior of minnows as an

index of possible pesticide pollution.

2. Basic research on how salmon migrate back to their home streams started more than 40 years

ago by Arthur Hasler has taught us much about the mechanisms of migration. This

information has also been valuable in preserving the salmon industry in the Pacific

Northwest and applications of Hasler's results has led to the development of a salmon fishing

industry in the Great Lakes. Basic animal behavior research can have important economic

implications.

3. Animal behaviorists have described variables involved in insect reproduction and host plant

location leading to the development of non-toxic pheromones for insect pest control that

avoid the need for toxic pesticides. Understanding of predator prey relationships can lead to

the introduction of natural predators on prey species.

4. Knowledge of honeybee foraging behavior can be applied to mechanisms of pollination

which in turn is important for plant breeding and propagation.

5. An understanding of foraging behavior in animals can lead to an understanding of forest

regeneration. Many animals serve as seed dispersers and are thus essential for the

propagation of tree species and essential for habitat preservation.

6. The conservation of endangered species requires that we know enough about natural

behavior (migratory patterns, home range size, interactions with other groups, foraging

a direct effect on immune system functioning. Researchers in physiology and immunology

need to be guided by these behavioral and social influences to properly control their own

studies.

C. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND THE ENVIRONMENT, CONSERVATION AND

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

1. The behavior of animals often provides the first clues or early warning signs of

environmental degradation. Changes in sexual and other behavior occur much sooner and at

lower levels of environmental disruption than changes in reproductive outcomes and

population size. If we wait to see if numbers of animal populations are declining, it may be

too late to take measures to save the environment. Studies of natural behavior in the field are

vital to provide baseline data for future environmental monitoring. For example, the

Environmental Protection Agency uses disruptions in swimming behavior of minnows as an

index of possible pesticide pollution.

2. Basic research on how salmon migrate back to their home streams started more than 40 years

ago by Arthur Hasler has taught us much about the mechanisms of migration. This

information has also been valuable in preserving the salmon industry in the Pacific

Northwest and applications of Hasler's results has led to the development of a salmon fishing

industry in the Great Lakes. Basic animal behavior research can have important economic

implications.

3. Animal behaviorists have described variables involved in insect reproduction and host plant

location leading to the development of non-toxic pheromones for insect pest control that

avoid the need for toxic pesticides. Understanding of predator prey relationships can lead to

the introduction of natural predators on prey species.

4. Knowledge of honeybee foraging behavior can be applied to mechanisms of pollination

which in turn is important for plant breeding and propagation.

5. An understanding of foraging behavior in animals can lead to an understanding of forest

regeneration. Many animals serve as seed dispersers and are thus essential for the

propagation of tree species and essential for habitat preservation.

6. The conservation of endangered species requires that we know enough about natural

behavior (migratory patterns, home range size, interactions with other groups, foraging

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

demands, reproductive behavior, communication, etc) in order to develop effective reserves

and effective protection measures. Relocation or reintroduction of animals (such as the

golden lion tamarin) is not possible without detailed knowledge of a species' natural history.

With the increasing importance of environmental programs and human management of

populations of rare species, both in captivity and in the natural habitat, animal behavior

research becomes increasingly important. Many of the world's leading conservationists have

a background in animal behavior or behavioral ecology.

7. Basic behavioral studies on reproductive behavior have led to improved captive breeding

methods for whooping cranes, golden lion tamarins, cotton-top tamarins, and many other

endangered species. Captive breeders who were ignorant of the species' natural reproductive

behavior were generally unsuccessful.

D. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND ANIMAL WELFARE

1. Our society has placed increased emphasis on the welfare of research and exhibit animals.

US law now requires attending to exercise requirements for dogs and the psychological well-

being of nonhuman primates. Animal welfare without knowledge is impossible. Animal

behavior researchers look at the behavior and well-being of animals in lab and field. We have

provided expert testimony to bring about reasonable and effective standards for the care and

well-being of research animals.

2. Further developments in animal welfare will require input from animal behavior specialists.

Improved conditions for farm animals, breeding of endangered species, proper care of

companion animals all require a strong behavioral data base.

E. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND SCIENCE EDUCATION

Many in our society are concerned with scientific illiteracy, the lack of interest that students have

in science and the fact that women and minority groups are underrepresented in science. Courses

in animal behavior and behavioral ecology serve as hooks to interest students in behavioral

biology. At the University of Wisconsin, Madison more than 700 students a year take courses in

animal behavior and behavioral ecology in the Departments of Anthropology, Psychology and

Zoology, yet none of these courses serve as required courses for majors. Cornell University

enrolls nearly 400 students in an Introduction to Behavior course that is required of only 60-70

students. Enrollment has grown by 30% in the last three years. At the University of Stirling,

Scotland, 75% of graduates in Psychology enroll in the elective, non-required animal behavior

and effective protection measures. Relocation or reintroduction of animals (such as the

golden lion tamarin) is not possible without detailed knowledge of a species' natural history.

With the increasing importance of environmental programs and human management of

populations of rare species, both in captivity and in the natural habitat, animal behavior

research becomes increasingly important. Many of the world's leading conservationists have

a background in animal behavior or behavioral ecology.

7. Basic behavioral studies on reproductive behavior have led to improved captive breeding

methods for whooping cranes, golden lion tamarins, cotton-top tamarins, and many other

endangered species. Captive breeders who were ignorant of the species' natural reproductive

behavior were generally unsuccessful.

D. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND ANIMAL WELFARE

1. Our society has placed increased emphasis on the welfare of research and exhibit animals.

US law now requires attending to exercise requirements for dogs and the psychological well-

being of nonhuman primates. Animal welfare without knowledge is impossible. Animal

behavior researchers look at the behavior and well-being of animals in lab and field. We have

provided expert testimony to bring about reasonable and effective standards for the care and

well-being of research animals.

2. Further developments in animal welfare will require input from animal behavior specialists.

Improved conditions for farm animals, breeding of endangered species, proper care of

companion animals all require a strong behavioral data base.

E. ANIMAL BEHAVIOR AND SCIENCE EDUCATION

Many in our society are concerned with scientific illiteracy, the lack of interest that students have

in science and the fact that women and minority groups are underrepresented in science. Courses

in animal behavior and behavioral ecology serve as hooks to interest students in behavioral

biology. At the University of Wisconsin, Madison more than 700 students a year take courses in

animal behavior and behavioral ecology in the Departments of Anthropology, Psychology and

Zoology, yet none of these courses serve as required courses for majors. Cornell University

enrolls nearly 400 students in an Introduction to Behavior course that is required of only 60-70

students. Enrollment has grown by 30% in the last three years. At the University of Stirling,

Scotland, 75% of graduates in Psychology enroll in the elective, non-required animal behavior

course. At the University of Washington, Seattle, more than 300 students enroll each quarter in a

basic animal behavior class. Similar results can be found on many other campuses.

For many students, especially females, these courses are their first introduction to behavioral

biology. Many female undergraduates approach us to discuss graduate school and research

careers after taking these courses. 75% or more of our graduate applicants are female. A good

proportion of students enrolled in animal behavior courses become motivated for research

careers, but there is little hope to offer them that they will actually be able to become practicing

scientists when they finish due to severe limitations on research funding.

Question # 05: Enlist various types of chemical signals

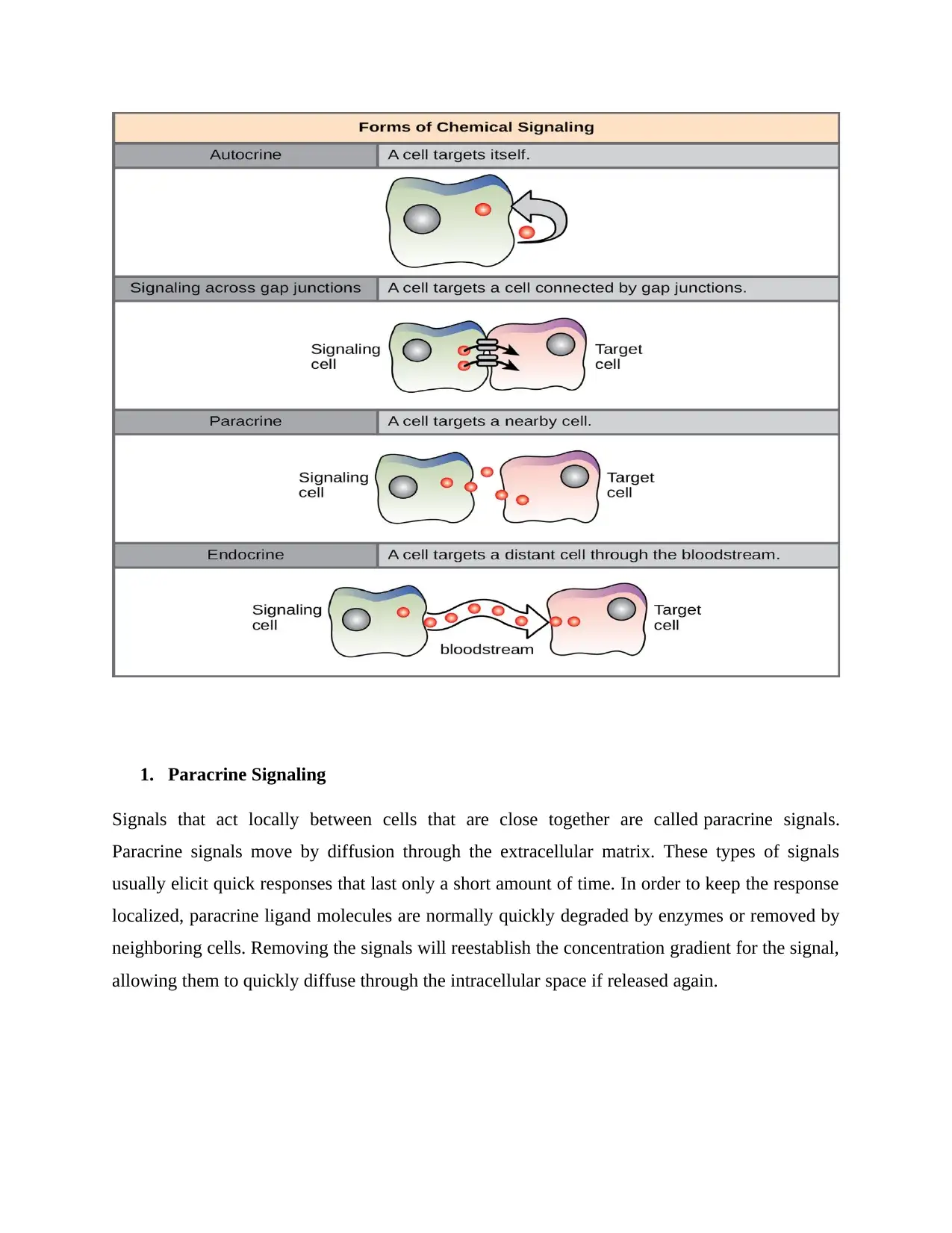

There are four categories of chemical signaling found in multicellular organisms: paracrine

signaling, endocrine signaling, autocrine signaling, and direct signaling across gap junctions

(Figure). The main difference between the different categories of signaling is the distance that

the signal travels through the organism to reach the target cell. Not all cells are affected by the

same signals.

basic animal behavior class. Similar results can be found on many other campuses.

For many students, especially females, these courses are their first introduction to behavioral

biology. Many female undergraduates approach us to discuss graduate school and research

careers after taking these courses. 75% or more of our graduate applicants are female. A good

proportion of students enrolled in animal behavior courses become motivated for research

careers, but there is little hope to offer them that they will actually be able to become practicing

scientists when they finish due to severe limitations on research funding.

Question # 05: Enlist various types of chemical signals

There are four categories of chemical signaling found in multicellular organisms: paracrine

signaling, endocrine signaling, autocrine signaling, and direct signaling across gap junctions

(Figure). The main difference between the different categories of signaling is the distance that

the signal travels through the organism to reach the target cell. Not all cells are affected by the

same signals.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

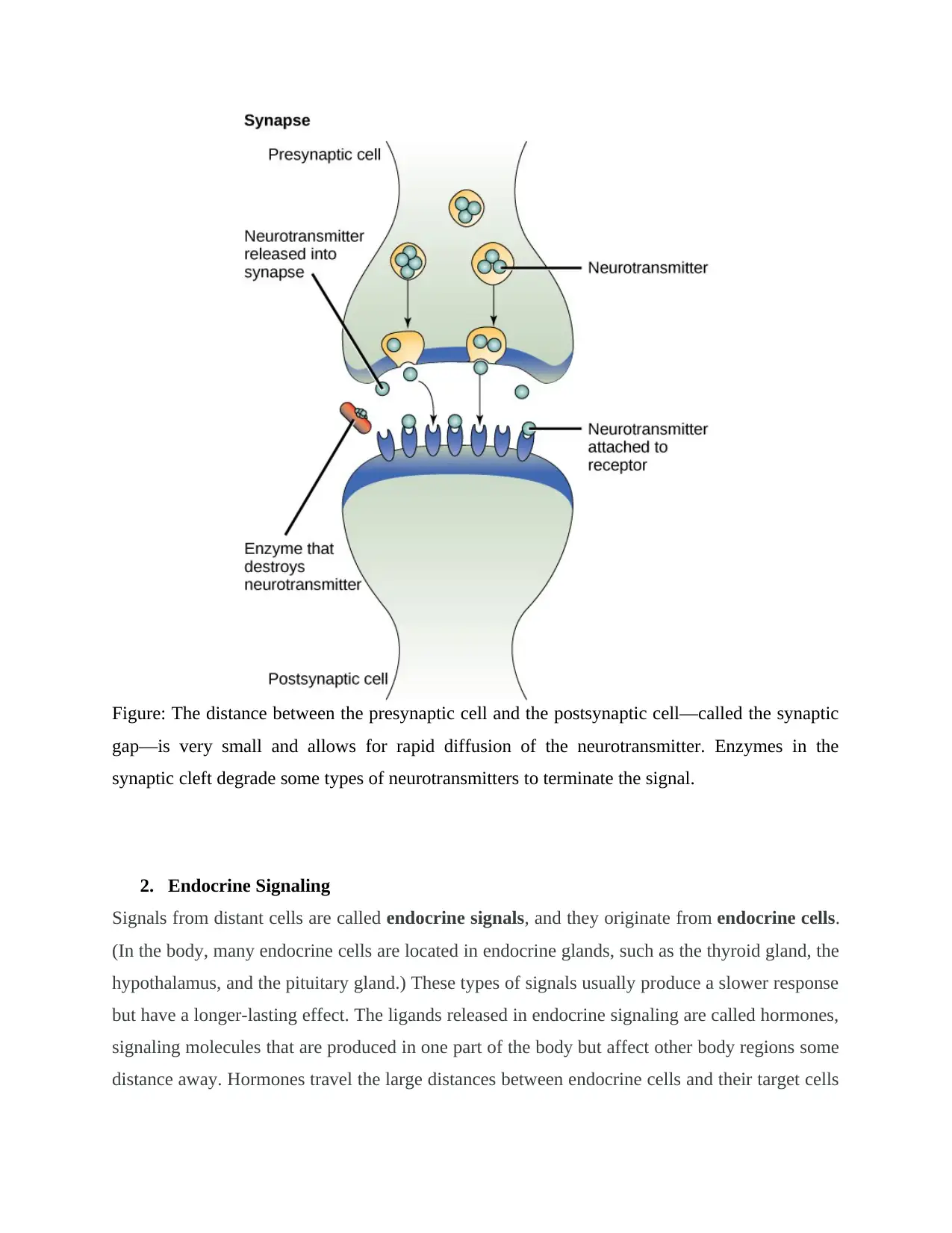

1. Paracrine Signaling

Signals that act locally between cells that are close together are called paracrine signals.

Paracrine signals move by diffusion through the extracellular matrix. These types of signals

usually elicit quick responses that last only a short amount of time. In order to keep the response

localized, paracrine ligand molecules are normally quickly degraded by enzymes or removed by

neighboring cells. Removing the signals will reestablish the concentration gradient for the signal,

allowing them to quickly diffuse through the intracellular space if released again.

Signals that act locally between cells that are close together are called paracrine signals.

Paracrine signals move by diffusion through the extracellular matrix. These types of signals

usually elicit quick responses that last only a short amount of time. In order to keep the response

localized, paracrine ligand molecules are normally quickly degraded by enzymes or removed by

neighboring cells. Removing the signals will reestablish the concentration gradient for the signal,

allowing them to quickly diffuse through the intracellular space if released again.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Figure: The distance between the presynaptic cell and the postsynaptic cell—called the synaptic

gap—is very small and allows for rapid diffusion of the neurotransmitter. Enzymes in the

synaptic cleft degrade some types of neurotransmitters to terminate the signal.

2. Endocrine Signaling

Signals from distant cells are called endocrine signals, and they originate from endocrine cells.

(In the body, many endocrine cells are located in endocrine glands, such as the thyroid gland, the

hypothalamus, and the pituitary gland.) These types of signals usually produce a slower response

but have a longer-lasting effect. The ligands released in endocrine signaling are called hormones,

signaling molecules that are produced in one part of the body but affect other body regions some

distance away. Hormones travel the large distances between endocrine cells and their target cells

gap—is very small and allows for rapid diffusion of the neurotransmitter. Enzymes in the

synaptic cleft degrade some types of neurotransmitters to terminate the signal.

2. Endocrine Signaling

Signals from distant cells are called endocrine signals, and they originate from endocrine cells.

(In the body, many endocrine cells are located in endocrine glands, such as the thyroid gland, the

hypothalamus, and the pituitary gland.) These types of signals usually produce a slower response

but have a longer-lasting effect. The ligands released in endocrine signaling are called hormones,

signaling molecules that are produced in one part of the body but affect other body regions some

distance away. Hormones travel the large distances between endocrine cells and their target cells

via the bloodstream, which is a relatively slow way to move throughout the body. Because of

their form of transport, hormones get diluted and are present in low concentrations when they act

on their target cells. This is different from paracrine signaling, in which local concentrations of

ligands can be very high.

3. Autocrine Signaling

Autocrine signals are produced by signaling cells that can also bind to the ligand that is

released. This means the signaling cell and the target cell can be the same or a similar cell (the

prefix auto- means self, a reminder that the signaling cell sends a signal to itself). This type of

signaling often occurs during the early development of an organism to ensure that cells develop

into the correct tissues and take on the proper function. Autocrine signaling also regulates pain

sensation and inflammatory responses. Further, if a cell is infected with a virus, the cell can

signal itself to undergo programmed cell death, killing the virus in the process. In some cases,

neighboring cells of the same type are also influenced by the released ligand. In embryological

development, this process of stimulating a group of neighboring cells may help to direct the

differentiation of identical cells into the same cell type, thus ensuring the proper developmental

outcome.

4. Direct Signaling Across Gap Junctions

Gap junctions in animals and plasmodesmata in plants are connections between the plasma

membranes of neighboring cells. These water-filled channels allow small signaling molecules,

called intracellular mediators, to diffuse between the two cells. Small molecules, such as

calcium ions (Ca2+), are able to move between cells, but large molecules like proteins and DNA

cannot fit through the channels. The specificity of the channels ensures that the cells remain

independent but can quickly and easily transmit signals. The transfer of signaling molecules

communicates the current state of the cell that is directly next to the target cell; this allows a

group of cells to coordinate their response to a signal that only one of them may have received.

In plants, plasmodesmata are ubiquitous, making the entire plant into a giant, communication

network.

Question # 06: Explain various behavioral communications among animals.

their form of transport, hormones get diluted and are present in low concentrations when they act

on their target cells. This is different from paracrine signaling, in which local concentrations of

ligands can be very high.

3. Autocrine Signaling

Autocrine signals are produced by signaling cells that can also bind to the ligand that is

released. This means the signaling cell and the target cell can be the same or a similar cell (the

prefix auto- means self, a reminder that the signaling cell sends a signal to itself). This type of

signaling often occurs during the early development of an organism to ensure that cells develop

into the correct tissues and take on the proper function. Autocrine signaling also regulates pain

sensation and inflammatory responses. Further, if a cell is infected with a virus, the cell can

signal itself to undergo programmed cell death, killing the virus in the process. In some cases,

neighboring cells of the same type are also influenced by the released ligand. In embryological

development, this process of stimulating a group of neighboring cells may help to direct the

differentiation of identical cells into the same cell type, thus ensuring the proper developmental

outcome.

4. Direct Signaling Across Gap Junctions

Gap junctions in animals and plasmodesmata in plants are connections between the plasma

membranes of neighboring cells. These water-filled channels allow small signaling molecules,

called intracellular mediators, to diffuse between the two cells. Small molecules, such as

calcium ions (Ca2+), are able to move between cells, but large molecules like proteins and DNA

cannot fit through the channels. The specificity of the channels ensures that the cells remain

independent but can quickly and easily transmit signals. The transfer of signaling molecules

communicates the current state of the cell that is directly next to the target cell; this allows a

group of cells to coordinate their response to a signal that only one of them may have received.

In plants, plasmodesmata are ubiquitous, making the entire plant into a giant, communication

network.

Question # 06: Explain various behavioral communications among animals.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 18

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.