Biomarker-Guided Antibiotic Stewardship in VAP: A Critical Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|10

|11013

|16

Report

AI Summary

The provided document is a research article published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, detailing the VAPrapid2 trial. This multicenter, randomized controlled trial investigated whether the measurement of IL-1β and IL-8 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid could improve antibiotic stewardship in patients with clinically suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units (ICUs). The study included 210 patients across 24 ICUs in the UK, randomly assigned to either biomarker-guided antibiotic recommendations or routine antibiotic use. The primary outcome was antibiotic-free days. The trial found no significant difference in the primary outcome between the groups, suggesting that a rapid, highly sensitive rule-out test did not improve antibiotic stewardship due to established prescribing practices and reluctance for bronchoalveolar lavage. The study highlights the need to address prescribing culture and barriers to adopting new technologies to optimize antibiotic use in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. The trial was funded by the UK Department of Health and the Wellcome Trust.

182 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

Articles

Lancet Respir Med 2020;

8: 182–91

Published Online

December 3, 2019

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2213-2600(19)30367-4

SeeComment page 130

Translational and Clinical

Research Institute

(T P Hellyer PhD, A J Rostron PhD,

J Scott BSc, Prof A J Simpson PhD),

National Institute for Health

Research Newcastle In Vitro

Diagnostics Cooperative

(A J Allen PhD, Prof A J Simpson),

and Newcastle Clinical Trials

Unit (J Parker MClinRes,

S A Bowett PhD), Newcastle

University, Newcastle, UK;

The Wellcome-Wolfson Centre

for Experimental Medicine,

Queen’s University Belfast,

Belfast, UK

(Prof D F McAuley MD,

R McMullan MD,

L M Emerson MPH,

Prof B Blackwood PhD,

Prof C M O’Kane PhD);

Regional Intensive Care Unit

(Prof D F McAuley) and

Northern Ireland Clinical Trials

Unit (A Agus PhD, G Phair MSc),

The Royal Hospitals, Belfast,

UK; Anaesthesia, Critical Care

and Pain Medicine, University

of Edinburgh, Queen’s Medical

Research Institute, Edinburgh,

UK (Prof T S Walsh MD);

Intensive Care Unit, Royal

Infirmary of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh, UK (Prof T S Walsh,

K Kefala MD); Usher Institute,

University of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh, UK

(N Anderson PhD); Division of

Anaesthesia, Department of

Medicine, University of

Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s

Hospital, Cambridge, UK

(A Conway Morris PhD);

Department of Cancer and

Surgery, Imperial College

London, London, UK

Biomarker-guided antibiotic stewardship in sus

ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAPrapid2):

controlled trial and process evaluation

Thomas P Hellyer, Daniel F McAuley, Timothy S Walsh, Niall Anderson, Andrew Conway Morris, Suveer Singh, Pa

Gavin D Perkins, Ronan McMullan, Lydia M Emerson, Bronagh Blackwood, Stephen E Wright, Kallirroi Kefala, Ce

Simon V Baudouin, Ross L Paterson, Anthony J Rostron, Ashley Agus, Jonathan Bannard-Smith, Nicole M Robin, I

Christopher Bassford, Bryan Yates, Craig Spencer, Shondipon K Laha, Jonathan Hulme, Stephen Bonner, Vaness

Tina Van Den Broeck, Gert Boschman, DW James Keenan, Jonathan Scott, A Joy Allen, Glenn Phair, Jennie Parke

A John Simpson

Summary

Background Ventilator-associated pneumonia is the most common intensive care unit (I

accurate diagnosis remains difficult, leading to overuse of antibiotics. Low concentratio

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid have been validated as effective markers for exclusion of ventila

The VAPrapid2 trial aimed to determine whether measurement of bronchoalveolar lavage flui

effectively and safely improve antibiotic stewardship in patients with clinically suspected ven

Methods VAPrapid2 was a multicentre, randomised controlled trial in patients admitted to 24

Health Service hospital trusts across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Patients were

and included if they were 18 years or older, intubated and mechanically ventilated for at leas

ventilator-associated pneumonia. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to biomarker-g

antibiotics (intervention group) or routine use of antibiotics (control group) using a web-base

hosted by Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit. Patients were randomised using randomly permuted

six and stratified by site, with allocation concealment. Clinicians were masked to patient assig

period until biomarker results were reported. Bronchoalveolar lavage was done in all patients

IL-1β and IL-8 rapidly determined in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients randomised to

antibiotic recommendation group. If concentrations were below a previously validated cutoff,

that ventilator-associated pneumonia was unlikely and to consider discontinuing antibiotics.

use of antibiotics group received antibiotics according to usual practice at sites. Micro

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from all patients and ventilator-associated pneumonia was

10⁴ colony forming units per mL of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The primary outcome

antibiotic-free days in the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage. Data were analysed on an

with an additional per-protocol analysis that excluded patients randomly assigned to t

defaulted to routine use of antibiotics because of failure to return an adequate bioma

process evaluation assessed factors influencing trial adoption, recruitment, and decisio

registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN65937227, and ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01972425.

Findings Between Nov 6, 2013, and Sept 13, 2016, 360 patients were screened for inclusion in

were ineligible, leaving 214 who were recruited to the study. Four patients were excluded bef

meaning that 210 patients were randomly assigned to biomarker-guided recommendation on

routine use of antibiotics (n=106). One patient in the biomarker-guided recommendation grou

the clinical team before bronchoscopy and so was excluded from the intention-to-treat

significant difference in the primary outcome of the distribution of antibiotic-free days

bronchoalveolar lavage in the intention-to-treat analysis (p=0·58). Bronchoalveolar lavag

small and transient increase in oxygen requirements. Established prescribing practices, reluc

lavage, and dependence on a chain of trial-related procedures emerged as factors that impair

Interpretation Antibiotic use remains high in patients with suspected ventilator-associat

stewardship was not improved by a rapid, highly sensitive rule-out test. Prescribing culture, r

performance, might explain this absence of effect.

Funding UK Department of Health and the Wellcome Trust.

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article und

Articles

Lancet Respir Med 2020;

8: 182–91

Published Online

December 3, 2019

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2213-2600(19)30367-4

SeeComment page 130

Translational and Clinical

Research Institute

(T P Hellyer PhD, A J Rostron PhD,

J Scott BSc, Prof A J Simpson PhD),

National Institute for Health

Research Newcastle In Vitro

Diagnostics Cooperative

(A J Allen PhD, Prof A J Simpson),

and Newcastle Clinical Trials

Unit (J Parker MClinRes,

S A Bowett PhD), Newcastle

University, Newcastle, UK;

The Wellcome-Wolfson Centre

for Experimental Medicine,

Queen’s University Belfast,

Belfast, UK

(Prof D F McAuley MD,

R McMullan MD,

L M Emerson MPH,

Prof B Blackwood PhD,

Prof C M O’Kane PhD);

Regional Intensive Care Unit

(Prof D F McAuley) and

Northern Ireland Clinical Trials

Unit (A Agus PhD, G Phair MSc),

The Royal Hospitals, Belfast,

UK; Anaesthesia, Critical Care

and Pain Medicine, University

of Edinburgh, Queen’s Medical

Research Institute, Edinburgh,

UK (Prof T S Walsh MD);

Intensive Care Unit, Royal

Infirmary of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh, UK (Prof T S Walsh,

K Kefala MD); Usher Institute,

University of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh, UK

(N Anderson PhD); Division of

Anaesthesia, Department of

Medicine, University of

Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s

Hospital, Cambridge, UK

(A Conway Morris PhD);

Department of Cancer and

Surgery, Imperial College

London, London, UK

Biomarker-guided antibiotic stewardship in sus

ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAPrapid2):

controlled trial and process evaluation

Thomas P Hellyer, Daniel F McAuley, Timothy S Walsh, Niall Anderson, Andrew Conway Morris, Suveer Singh, Pa

Gavin D Perkins, Ronan McMullan, Lydia M Emerson, Bronagh Blackwood, Stephen E Wright, Kallirroi Kefala, Ce

Simon V Baudouin, Ross L Paterson, Anthony J Rostron, Ashley Agus, Jonathan Bannard-Smith, Nicole M Robin, I

Christopher Bassford, Bryan Yates, Craig Spencer, Shondipon K Laha, Jonathan Hulme, Stephen Bonner, Vaness

Tina Van Den Broeck, Gert Boschman, DW James Keenan, Jonathan Scott, A Joy Allen, Glenn Phair, Jennie Parke

A John Simpson

Summary

Background Ventilator-associated pneumonia is the most common intensive care unit (I

accurate diagnosis remains difficult, leading to overuse of antibiotics. Low concentratio

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid have been validated as effective markers for exclusion of ventila

The VAPrapid2 trial aimed to determine whether measurement of bronchoalveolar lavage flui

effectively and safely improve antibiotic stewardship in patients with clinically suspected ven

Methods VAPrapid2 was a multicentre, randomised controlled trial in patients admitted to 24

Health Service hospital trusts across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Patients were

and included if they were 18 years or older, intubated and mechanically ventilated for at leas

ventilator-associated pneumonia. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to biomarker-g

antibiotics (intervention group) or routine use of antibiotics (control group) using a web-base

hosted by Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit. Patients were randomised using randomly permuted

six and stratified by site, with allocation concealment. Clinicians were masked to patient assig

period until biomarker results were reported. Bronchoalveolar lavage was done in all patients

IL-1β and IL-8 rapidly determined in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients randomised to

antibiotic recommendation group. If concentrations were below a previously validated cutoff,

that ventilator-associated pneumonia was unlikely and to consider discontinuing antibiotics.

use of antibiotics group received antibiotics according to usual practice at sites. Micro

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from all patients and ventilator-associated pneumonia was

10⁴ colony forming units per mL of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The primary outcome

antibiotic-free days in the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage. Data were analysed on an

with an additional per-protocol analysis that excluded patients randomly assigned to t

defaulted to routine use of antibiotics because of failure to return an adequate bioma

process evaluation assessed factors influencing trial adoption, recruitment, and decisio

registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN65937227, and ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01972425.

Findings Between Nov 6, 2013, and Sept 13, 2016, 360 patients were screened for inclusion in

were ineligible, leaving 214 who were recruited to the study. Four patients were excluded bef

meaning that 210 patients were randomly assigned to biomarker-guided recommendation on

routine use of antibiotics (n=106). One patient in the biomarker-guided recommendation grou

the clinical team before bronchoscopy and so was excluded from the intention-to-treat

significant difference in the primary outcome of the distribution of antibiotic-free days

bronchoalveolar lavage in the intention-to-treat analysis (p=0·58). Bronchoalveolar lavag

small and transient increase in oxygen requirements. Established prescribing practices, reluc

lavage, and dependence on a chain of trial-related procedures emerged as factors that impair

Interpretation Antibiotic use remains high in patients with suspected ventilator-associat

stewardship was not improved by a rapid, highly sensitive rule-out test. Prescribing culture, r

performance, might explain this absence of effect.

Funding UK Department of Health and the Wellcome Trust.

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article und

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Articles

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 183

(S Singh PhD); Division of

Infection Immunity and

Respiratory Medicine,

Manchester National Institute

for Health Research Biomedica

Research Centre, University of

Manchester, Manchester, UK

(Prof P Dark PhD); Integrated

Critical Care Unit, Sunderland

Royal Hospital, City Hospitals

Sunderland NHS Foundation

Trust, Sunderland, UK

(A I Roy MBChB, A J Rostron);

Warwick Medical School,

University of Warwick,

Coventry, UK

(Prof G D Perkins MD); Intensive

Care Unit, Heartlands Hospital

University Hospitals

Birmingham NHS Foundation

Trust, Birmingham, UK

(Prof G D Perkins); Integrated

Critical Care Unit, Freeman

Hospital (S E Wright MBChB)

and Intensive Care Unit, Royal

Victoria Infirmary

(S V Baudouin MD), Newcastle

upon Tyne Hospitals NHS

Foundation Trust, Newcastle,

UK; Intensive Care Unit,

Western General Hospital,

Edinburgh, UK

(R L Paterson MD); Intensive

Care Unit, Manchester Royal

Infirmary, Manchester

University NHS Foundation

Trust, Manchester, UK

(J Bannard-Smith MBChB);

Intensive Care Unit, Countess

of Chester NHS Foundation

Trust, Chester, UK

(N M Robin MBChB); Institute

of Ageing and Chronic Disease

University of Liverpool,

Liverpool, UK

(Prof I D Welters PhD); Intensive

Care Unit, University Hospital

Coventry, University Hospitals

Coventry and Warwickshire

NHS Trust, Coventry, UK

(C Bassford PhD); Intensive Care

Unit, Northumbria Specialist

Emergency Care Hospital,

Cramlington, UK

(B Yates MBBS); Intensive Care

Unit, Preston Royal Hospital,

Lancashire Teaching Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust,

Preston, UK (C Spencer MBChB,

S K Laha MA); Intensive Care

Unit, Sandwell General

Hospital, Sandwell and

West Birmingham Hospitals

NHS Trust, West Bromwich, UK

(J Hulme MD); Intensive Care

Unit, James Cook University

Hospital, South Tees Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust,

Middlesbrough, UK

(Prof S Bonner FFICM); Intensive

Care Unit, Queen Elizabeth

Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia is the most common

infection acquired in intensive care units (ICUs),1 and is

associatedwith substantialmortality,particu larlyin

the ageing ICU population.2 Broad-spectrum antibiotic

use is recommended in suspected ventilator-associated

pneumonia.3,4 However,diag nosisof this infection

remains notoriously difficult, and pulmonary infection is

typically confirmed in only 20–60% of suspected cases.5

Consequently,antibioticsare overusedfor suspected

ventilator-associatedpneumonia,potentiallyexposing

patients to adverse effects, detracting from alternative

causes of respiratory compromise, increasing costs, and

driving emergence of antimicrobial resistance.5

Point prevalence studies suggest that 70% of patients

in the ICU receive antibiotics.6 The association between

increased antibiotic use and emergence of antimicrobial

resistance in ICUs is well established.7 In the setting

of hospital-acquired pneumonia, adherence to guide-

lines that promote broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics

has been associatedwith adverseoutcomes.8 This

background has driven a need to rationalise antibiotic

prescribing in ICUs.

Rapid diagnostic tests with the capacity to rule out

ventilator-associatedpneumoniamight presentearly

opportunitiesto optimiseantibioticprescriptionand

decrease antibiotic use. Among protein-based biomarkers,

only a combination of low IL-1β and IL-8 concentrations

in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid has been validated in a

multicentresetting in suspectedventilator-asso ciated

pneumonia.9,10

The VAPrapid2 trial aimed to determinewhether

measurement of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid IL-1β and

IL-8 could improve antibiotic stewardshipwithout

compromisingpatientsafetyin suspectedventilator-

associated pneumonia. In keeping with expert guidance

on analysis of complex interventions,11 a process eva-

luation study was embedded in this trial.

Methods

Study design and participants

VAPrapid2 was a multicentre, randomised controlled

trial in patients admitted to the ICU with suspected

ventilator-associated pneumonia. The trial was done in

24 ICUs from 17 National Health Service (NHS) hospital

trusts across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We searched Medline between Jan 1, 1996, and April 30, 2019,

with the MeSH terms “Pneumonia”; “Pneumonia, bacterial”;

“Pneumonia, Ventilator-Associated”; “Respiratory Tract

Infections”; “Biomarkers”; “Protein Precursors”; and “Anti-

bacterial Agents”. Although several trials investigated the role

of procalcitonin in reducing antibiotic use in lower respiratory

tract infections, to our knowledge, few trials have been done in

patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. A multicentre

trial of a procalcitonin-guided intervention to discontinue

antibiotics in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia

reported a significant improvement in antibiotic-free days at

28 days. However, the duration of antibiotics in both the

intervention and the control groups of the trial were longer

than the 8-day duration recommended in international

guidelines. A further single-centre trial used a combination of

the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score and procalcitonin to

guide antibiotic discontinuation in patients who had already

completed 7 days of antibiotic therapy. Although patients in

the procalcitonin group had more antibiotic-free days at

28 days versus the control group, the duration of antibiotics in

both groups was longer than 8 days. These studies focused on

discontinuation of antibiotics once empirical treatment was

established. To our knowledge, there are no published trials in

which antibiotic stewardship is based on early exclusion of

ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, VAPrapid2 is the first trial to use a validated

biomarker in a cohort of patients with clinically suspected

ventilator-associated pneumonia, with an aim to determine

whether early exclusion of ventilator-associated pneumonia

could improve antibiotic stewardship. Furthermore, our trial

included a process evaluation that aimed to understand clinical

behaviours and implementation of the trial protocol. This trial

showed that, although the biomarker test could accurately

exclude ventilator-associated pneumonia, the trial

recommendation regarding antibiotic discontinuation was

seldom followed by clinicians, resulting in no difference in

antibiotic use between the intervention and control groups.

The results of this trial highlight entrenched behaviours in

antibiotic prescribing practice and barriers to adopting new,

unfamiliar technologies.

Implications of all the available evidence

Previous trials of procalcitonin have influenced the duration of

antibiotic treatment in patients with ventilator-associated

pneumonia. However, most patients with suspected ventilator-

associated pneumonia do not actually have it, subjecting them

to unnecessary antibiotic treatment while the true cause of

respiratory compromise potentially goes untreated. Avoiding

antibiotic use in such patients remains an important goal for

antibiotic stewardship in intensive care units. The VAPrapid2

trial showed no influence on antibiotic prescribing practices in

this patient group. Future studies should differentiate

suspected from confirmed ventilator-associated pneumonia,

aim to reduce antibiotics in patients who do not have

confirmed infection, and dissect complex mechanisms that

influence prescribing practices.

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 183

(S Singh PhD); Division of

Infection Immunity and

Respiratory Medicine,

Manchester National Institute

for Health Research Biomedica

Research Centre, University of

Manchester, Manchester, UK

(Prof P Dark PhD); Integrated

Critical Care Unit, Sunderland

Royal Hospital, City Hospitals

Sunderland NHS Foundation

Trust, Sunderland, UK

(A I Roy MBChB, A J Rostron);

Warwick Medical School,

University of Warwick,

Coventry, UK

(Prof G D Perkins MD); Intensive

Care Unit, Heartlands Hospital

University Hospitals

Birmingham NHS Foundation

Trust, Birmingham, UK

(Prof G D Perkins); Integrated

Critical Care Unit, Freeman

Hospital (S E Wright MBChB)

and Intensive Care Unit, Royal

Victoria Infirmary

(S V Baudouin MD), Newcastle

upon Tyne Hospitals NHS

Foundation Trust, Newcastle,

UK; Intensive Care Unit,

Western General Hospital,

Edinburgh, UK

(R L Paterson MD); Intensive

Care Unit, Manchester Royal

Infirmary, Manchester

University NHS Foundation

Trust, Manchester, UK

(J Bannard-Smith MBChB);

Intensive Care Unit, Countess

of Chester NHS Foundation

Trust, Chester, UK

(N M Robin MBChB); Institute

of Ageing and Chronic Disease

University of Liverpool,

Liverpool, UK

(Prof I D Welters PhD); Intensive

Care Unit, University Hospital

Coventry, University Hospitals

Coventry and Warwickshire

NHS Trust, Coventry, UK

(C Bassford PhD); Intensive Care

Unit, Northumbria Specialist

Emergency Care Hospital,

Cramlington, UK

(B Yates MBBS); Intensive Care

Unit, Preston Royal Hospital,

Lancashire Teaching Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust,

Preston, UK (C Spencer MBChB,

S K Laha MA); Intensive Care

Unit, Sandwell General

Hospital, Sandwell and

West Birmingham Hospitals

NHS Trust, West Bromwich, UK

(J Hulme MD); Intensive Care

Unit, James Cook University

Hospital, South Tees Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust,

Middlesbrough, UK

(Prof S Bonner FFICM); Intensive

Care Unit, Queen Elizabeth

Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia is the most common

infection acquired in intensive care units (ICUs),1 and is

associatedwith substantialmortality,particu larlyin

the ageing ICU population.2 Broad-spectrum antibiotic

use is recommended in suspected ventilator-associated

pneumonia.3,4 However,diag nosisof this infection

remains notoriously difficult, and pulmonary infection is

typically confirmed in only 20–60% of suspected cases.5

Consequently,antibioticsare overusedfor suspected

ventilator-associatedpneumonia,potentiallyexposing

patients to adverse effects, detracting from alternative

causes of respiratory compromise, increasing costs, and

driving emergence of antimicrobial resistance.5

Point prevalence studies suggest that 70% of patients

in the ICU receive antibiotics.6 The association between

increased antibiotic use and emergence of antimicrobial

resistance in ICUs is well established.7 In the setting

of hospital-acquired pneumonia, adherence to guide-

lines that promote broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics

has been associatedwith adverseoutcomes.8 This

background has driven a need to rationalise antibiotic

prescribing in ICUs.

Rapid diagnostic tests with the capacity to rule out

ventilator-associatedpneumoniamight presentearly

opportunitiesto optimiseantibioticprescriptionand

decrease antibiotic use. Among protein-based biomarkers,

only a combination of low IL-1β and IL-8 concentrations

in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid has been validated in a

multicentresetting in suspectedventilator-asso ciated

pneumonia.9,10

The VAPrapid2 trial aimed to determinewhether

measurement of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid IL-1β and

IL-8 could improve antibiotic stewardshipwithout

compromisingpatientsafetyin suspectedventilator-

associated pneumonia. In keeping with expert guidance

on analysis of complex interventions,11 a process eva-

luation study was embedded in this trial.

Methods

Study design and participants

VAPrapid2 was a multicentre, randomised controlled

trial in patients admitted to the ICU with suspected

ventilator-associated pneumonia. The trial was done in

24 ICUs from 17 National Health Service (NHS) hospital

trusts across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We searched Medline between Jan 1, 1996, and April 30, 2019,

with the MeSH terms “Pneumonia”; “Pneumonia, bacterial”;

“Pneumonia, Ventilator-Associated”; “Respiratory Tract

Infections”; “Biomarkers”; “Protein Precursors”; and “Anti-

bacterial Agents”. Although several trials investigated the role

of procalcitonin in reducing antibiotic use in lower respiratory

tract infections, to our knowledge, few trials have been done in

patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. A multicentre

trial of a procalcitonin-guided intervention to discontinue

antibiotics in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia

reported a significant improvement in antibiotic-free days at

28 days. However, the duration of antibiotics in both the

intervention and the control groups of the trial were longer

than the 8-day duration recommended in international

guidelines. A further single-centre trial used a combination of

the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score and procalcitonin to

guide antibiotic discontinuation in patients who had already

completed 7 days of antibiotic therapy. Although patients in

the procalcitonin group had more antibiotic-free days at

28 days versus the control group, the duration of antibiotics in

both groups was longer than 8 days. These studies focused on

discontinuation of antibiotics once empirical treatment was

established. To our knowledge, there are no published trials in

which antibiotic stewardship is based on early exclusion of

ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, VAPrapid2 is the first trial to use a validated

biomarker in a cohort of patients with clinically suspected

ventilator-associated pneumonia, with an aim to determine

whether early exclusion of ventilator-associated pneumonia

could improve antibiotic stewardship. Furthermore, our trial

included a process evaluation that aimed to understand clinical

behaviours and implementation of the trial protocol. This trial

showed that, although the biomarker test could accurately

exclude ventilator-associated pneumonia, the trial

recommendation regarding antibiotic discontinuation was

seldom followed by clinicians, resulting in no difference in

antibiotic use between the intervention and control groups.

The results of this trial highlight entrenched behaviours in

antibiotic prescribing practice and barriers to adopting new,

unfamiliar technologies.

Implications of all the available evidence

Previous trials of procalcitonin have influenced the duration of

antibiotic treatment in patients with ventilator-associated

pneumonia. However, most patients with suspected ventilator-

associated pneumonia do not actually have it, subjecting them

to unnecessary antibiotic treatment while the true cause of

respiratory compromise potentially goes untreated. Avoiding

antibiotic use in such patients remains an important goal for

antibiotic stewardship in intensive care units. The VAPrapid2

trial showed no influence on antibiotic prescribing practices in

this patient group. Future studies should differentiate

suspected from confirmed ventilator-associated pneumonia,

aim to reduce antibiotics in patients who do not have

confirmed infection, and dissect complex mechanisms that

influence prescribing practices.

Articles

184 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

Hospital, Gateshead NHS

Foundation Trust, Gateshead,

UK (V Linnett MBBS); Intensive

Care Unit, Russells Hall

Hospital, Dudley Group NHS

Foundation Trust, Dudley, UK

(J Sonksen MBChB); and Becton

Dickinson Biosciences Europe,

Erembodegem, Belgium

(T Van Den Broeck PhD,

G Boschman PhD,

D W J Keenan BSc)

Correspondence to:

Prof A John Simpson,

Translational and Clinical

Research Institute, Newcastle

University, Newcastle NE2 4HH,

UK

j.simpson@ncl.ac.uk

See Onlinefor appendix

Patients were screened for eligibility on weekdays and

included if they were aged 18 years or older, intubated

and mechanically ventilated for at least 48 h, and had

suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Criteria for

suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia were new or

worsening chest radiographic (x-ray or chest CT) alveolar

changesplus at least two of the following: body

temperature less than 35°C or greater than 38°C, white

cell count less than 4 × 10⁹/L or greater than 11 × 10⁹/L,

and purulent tracheal secretions.5 Additionally, clinicians

had to con sidereligible patientsunlikely to have

extrapulmonary infection requiring antibiotic treatment

(ie, early discontinuationof antibioticswould be

appropriateif ventilator-associatedpneumonia was

confidently excluded).

Patients were excluded if they fulfilled the criteria

predicting poor tolerance of bronchoscopy and broncho-

alveolar lavage: PaO2 less than 8 kPa on FiO2 greater

than 0·7, positive end-expiratory pressure greater than

15 cmH2O, peak airway pressure greater than 35 cmH2O,

heart rate greater than 140 beats per minute, mean

arterial pressure less than 65 mm Hg, bleeding diathesis

(platelet count <20 × 10⁹/L or international normalised

ratio >3), intracranial pressure greater than 20 mm Hg,

and ICU consultantconsideredbronchoscopyand

bronchoalveolar lavage to be unsafe for the patient.

The research protocol was approved by the England and

Northern Ireland (13/LO/065) and Scotland (13/SS/0074)

National Research Ethics Service committees, and the trial

protocol has been published previously.12 Patients or their

relatives or representatives gave written informed consent

for inclusion in the study.

Randomisation and masking

Patientswere randomlyassigned(1:1)to biomarker-

guided recommendationon antibiotics(intervention

group) or routine use of antibiotics(controlgroup)

using a web-basedrandomisationservicehostedby

Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). Randomisation

was triggered by the technician receiving each patient’s

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample. The randomisation

sequence was generated by the trial statistician using

Sealed Envelope.Patients were randomisedusing

randomlypermuted blocks ofsize fourand six and

stratified by site, with allocation concealment. Participants

underwent the same clinical procedures up to the point

biomarker results were returned to the clinical service

for the intervention group. Therefore, there was an initial

period of double-blinding until test results were com-

municated to clini cians. As such, clinicians and research

nurses were masked until the biomarker results became

available.

Procedures

Investigators were asked to record a clinical opinion on

the pre-testprobabilityof ventilator-associatedpneu-

monia in randomly assigned patients—high, medium,

or low. A protocolised bronchoscopy and bronchoalveola

lavage was arranged for all randomly assigned patients

using a 120 mL lavage with 0·9% saline.10 Samples were

transportedat 4°C to one of six testinglaboratories

(appendix p 5), with a transport time of up to 1·5 h.

IL-1β and IL-8 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid wer

measured by cytometric bead array using Accuri C6 flow

cytometers (Becton Dickinson Biosciences; San Jose, CA

USA). IL-1β and IL-8 concentrations in bronchoalveolar

lavagefluid were enteredinto a previouslyderived

equation for the exclusion of ventilator-associated pneu

monia,10 and an automated calculation was made av

able to the laboratory staff processing bronchoalveo

lavage fluid samples. Instructions were communicate

to clinicians by telephoneimmediatelyafter results

became available. For patients randomly assigned t

the biomarker-guided group, the instruction relayed

clinicians was either, “Biomarker result above cutoff

Ventilator-associatedpneumoniacannotbe excluded,

consider continuing antibiotics,” or “Biomarker resul

below cutoff. The negative predictive value is 1 an

ventilator-associatedpneumonia is very unlikely.

Consider discontinuation of antibiotics.” For patients

randomlyassignedto routine use of antibioticsthe

instruction given to clinicians was, “Patient in routin

use of antibiotics group.” If assays did not meet internal

quality control criteria, clinicians were advised to defaul

to routine care. The median negative predictive val

previously calculated for the combination of IL-1β a

IL-8 was 1·0 (95% CI 0·92–1·0).10

We defined confirmed ventilator-associated pneumoni

as growth of a potentially pathogenic organism of at lea

10⁴ colony forming units (CFU) per mL of broncho-

alveolar lavage fluid.13Microbiology testing was done in

accredited NHS or Public Health England microbiology

laboratories. Standard operating procedures for sem

quan titative culture were done in accordance with

2012 UK Standardsfor MicrobiologyInvestigation,

issued by the Health Protection Agency. This strate

allowed samples to be quantified as having no gro

1–10 CFU/mL, 10–10² CFU/mL, 10²–10³ CFU/mL,

10³–10⁴ CFU/mL, 10⁴–10⁵ CFU/mL, and so on, allowing

simple and clear demarcationof bacteriagrown at

10⁴ CFU/mL or more (ventilator-associated pneumonia)

and less than 10⁴ CFU/mL.

Investigators visited all ICUs before recruitment com-

menced, providing educational sessions on the diagnos

performance of the biomarkers and on the trial int

vention. Key components of trial design were reinforced

through regular communication. Additional training was

done in testing laboratories with respect to laborato

processes and biomarker measurement. Before the

commenced, clinicians were again made aware of t

biomarkertest and were encouragedto follow the

biomarker-guided recommendations. However, antibiot

use decisions were not mandated and were at clinicians

discretion.

For more on Sealed Envelope

see www.sealedenvelope.com

184 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

Hospital, Gateshead NHS

Foundation Trust, Gateshead,

UK (V Linnett MBBS); Intensive

Care Unit, Russells Hall

Hospital, Dudley Group NHS

Foundation Trust, Dudley, UK

(J Sonksen MBChB); and Becton

Dickinson Biosciences Europe,

Erembodegem, Belgium

(T Van Den Broeck PhD,

G Boschman PhD,

D W J Keenan BSc)

Correspondence to:

Prof A John Simpson,

Translational and Clinical

Research Institute, Newcastle

University, Newcastle NE2 4HH,

UK

j.simpson@ncl.ac.uk

See Onlinefor appendix

Patients were screened for eligibility on weekdays and

included if they were aged 18 years or older, intubated

and mechanically ventilated for at least 48 h, and had

suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Criteria for

suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia were new or

worsening chest radiographic (x-ray or chest CT) alveolar

changesplus at least two of the following: body

temperature less than 35°C or greater than 38°C, white

cell count less than 4 × 10⁹/L or greater than 11 × 10⁹/L,

and purulent tracheal secretions.5 Additionally, clinicians

had to con sidereligible patientsunlikely to have

extrapulmonary infection requiring antibiotic treatment

(ie, early discontinuationof antibioticswould be

appropriateif ventilator-associatedpneumonia was

confidently excluded).

Patients were excluded if they fulfilled the criteria

predicting poor tolerance of bronchoscopy and broncho-

alveolar lavage: PaO2 less than 8 kPa on FiO2 greater

than 0·7, positive end-expiratory pressure greater than

15 cmH2O, peak airway pressure greater than 35 cmH2O,

heart rate greater than 140 beats per minute, mean

arterial pressure less than 65 mm Hg, bleeding diathesis

(platelet count <20 × 10⁹/L or international normalised

ratio >3), intracranial pressure greater than 20 mm Hg,

and ICU consultantconsideredbronchoscopyand

bronchoalveolar lavage to be unsafe for the patient.

The research protocol was approved by the England and

Northern Ireland (13/LO/065) and Scotland (13/SS/0074)

National Research Ethics Service committees, and the trial

protocol has been published previously.12 Patients or their

relatives or representatives gave written informed consent

for inclusion in the study.

Randomisation and masking

Patientswere randomlyassigned(1:1)to biomarker-

guided recommendationon antibiotics(intervention

group) or routine use of antibiotics(controlgroup)

using a web-basedrandomisationservicehostedby

Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). Randomisation

was triggered by the technician receiving each patient’s

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample. The randomisation

sequence was generated by the trial statistician using

Sealed Envelope.Patients were randomisedusing

randomlypermuted blocks ofsize fourand six and

stratified by site, with allocation concealment. Participants

underwent the same clinical procedures up to the point

biomarker results were returned to the clinical service

for the intervention group. Therefore, there was an initial

period of double-blinding until test results were com-

municated to clini cians. As such, clinicians and research

nurses were masked until the biomarker results became

available.

Procedures

Investigators were asked to record a clinical opinion on

the pre-testprobabilityof ventilator-associatedpneu-

monia in randomly assigned patients—high, medium,

or low. A protocolised bronchoscopy and bronchoalveola

lavage was arranged for all randomly assigned patients

using a 120 mL lavage with 0·9% saline.10 Samples were

transportedat 4°C to one of six testinglaboratories

(appendix p 5), with a transport time of up to 1·5 h.

IL-1β and IL-8 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid wer

measured by cytometric bead array using Accuri C6 flow

cytometers (Becton Dickinson Biosciences; San Jose, CA

USA). IL-1β and IL-8 concentrations in bronchoalveolar

lavagefluid were enteredinto a previouslyderived

equation for the exclusion of ventilator-associated pneu

monia,10 and an automated calculation was made av

able to the laboratory staff processing bronchoalveo

lavage fluid samples. Instructions were communicate

to clinicians by telephoneimmediatelyafter results

became available. For patients randomly assigned t

the biomarker-guided group, the instruction relayed

clinicians was either, “Biomarker result above cutoff

Ventilator-associatedpneumoniacannotbe excluded,

consider continuing antibiotics,” or “Biomarker resul

below cutoff. The negative predictive value is 1 an

ventilator-associatedpneumonia is very unlikely.

Consider discontinuation of antibiotics.” For patients

randomlyassignedto routine use of antibioticsthe

instruction given to clinicians was, “Patient in routin

use of antibiotics group.” If assays did not meet internal

quality control criteria, clinicians were advised to defaul

to routine care. The median negative predictive val

previously calculated for the combination of IL-1β a

IL-8 was 1·0 (95% CI 0·92–1·0).10

We defined confirmed ventilator-associated pneumoni

as growth of a potentially pathogenic organism of at lea

10⁴ colony forming units (CFU) per mL of broncho-

alveolar lavage fluid.13Microbiology testing was done in

accredited NHS or Public Health England microbiology

laboratories. Standard operating procedures for sem

quan titative culture were done in accordance with

2012 UK Standardsfor MicrobiologyInvestigation,

issued by the Health Protection Agency. This strate

allowed samples to be quantified as having no gro

1–10 CFU/mL, 10–10² CFU/mL, 10²–10³ CFU/mL,

10³–10⁴ CFU/mL, 10⁴–10⁵ CFU/mL, and so on, allowing

simple and clear demarcationof bacteriagrown at

10⁴ CFU/mL or more (ventilator-associated pneumonia)

and less than 10⁴ CFU/mL.

Investigators visited all ICUs before recruitment com-

menced, providing educational sessions on the diagnos

performance of the biomarkers and on the trial int

vention. Key components of trial design were reinforced

through regular communication. Additional training was

done in testing laboratories with respect to laborato

processes and biomarker measurement. Before the

commenced, clinicians were again made aware of t

biomarkertest and were encouragedto follow the

biomarker-guided recommendations. However, antibiot

use decisions were not mandated and were at clinicians

discretion.

For more on Sealed Envelope

see www.sealedenvelope.com

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Articles

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 185

A process evaluation was done with interviews of clinical

staff and research staff (eg, site principal investigator,

consultants, research nurses, and ward manager) in the

following three phases: pre-trial (in month 1 of sites

joining the trial; exploring routine diagnosis and

management of ventilator-associated pneumonia), mid-

trial (once a site was involved in the trial for at least 1 year;

exploring intervention quality, attitudes to the trial, and

barriers or facilitators to suc cessful trial delivery), and late-

trial, with purposive sampling of nine sites based on pre-

trial and mid-trial results (in the final 3 months of the

intervention period in June to Augsust, 2016; exploring

local factors determining recruitment). Interviews were

done by LME. Further details are in the appendix (p 4).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the distribution of antibiotic-

free days in the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage.

Antibiotic-free days were handled as an integer, with

patients classified in one of eight categories (0–7 antibiotic-

free days, inclusive).

Predefined secondary outcomes were antibiotic-free

days at days 14 and 28, antibiotic days at days 7, 14, and

28, ventilator-free days at 28 days, 28-day mortality and

ICU mortality,sequentialorgan failure assessment

(SOFA) score at days 3, 7 and 14, duration of critical care

(level 2 and level 3 care) and hospital stay, antibiotic-

associated infections (Clostridium difficile and meticillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus) up to hospital discharge,

death, or 56 days, antibiotic-resistant pathogens (resistant

to two or more antibiotics) cultured up to hospital dis-

charge, death, or 56 days, and health-care resource use

calculated from length of critical care and hospital stay

up to discharge, death, or 56 days. When considering

outcomes at days 7, 14, and 28, antibiotics refers to all

antibiotics given for treatment of infection; prophylactic

antibiotics were not considered.

Since adverse clinical events are common in ICUs, the

trial protocolmandatedreportingof adverseevents

within 2 h of bronchoscopy. Clinical team members

reported any further events after 2 h if they were con-

sidered clinically significant or related to the trial.

Statistical analysis

Full statistical methods were outlined in a Statistical

Analysis Plan before the close of recruitment. Sample

size was based on the change in frequency distribution

of antibiotic-free days in the 7 days following broncho-

alveolar lavage. Models of change in distribution are

outlined in the trial protocol.12 We deemed effect sizes

in the region 0·07–0·08 to be of a clinically relevant

magnitude.These effect sizes representan approx -

imate change in median antibiotic-free days from 0

(IQR 0·0–2·5) to 1·5 (0·0–3·5). There fore, we proposed

a recruitment target of 90 patients per group, with an α

of 0·05 and β of 0·20. Allowing for attrition of 14·3%,

the target sample size was 210 patients. The primary

analysis was done on the intention-to-treat population.

We analysedthe primary outcomeby χ² test on a

2 × 8 table of trial group versus antibiotic-free days.

Sensitivity analyses were done using a discrete-time

Cox proportionalhazards model with centre and

randomisation group as covariates, censored for death

or end of follow-up at 7 days. We did a further sensitivity

analysis, redefining antibiotic-freedays as zero if

death occurred within 7 days, as a more conservative

approach.

We analysed secondary outcomes using Cox propor-

tional hazards models, logistic regression, linear regres-

sion, or Poisson regression as appropriate (see appendix

p 4). Planned subgroup analyses included a per-protocol

analysis, clinician assessment of likelihood of ventilator-

associated pneumonia, and admission category (medical,

surgical caused by trauma or head injury, and other

surgical). We excluded patients randomly assigned to the

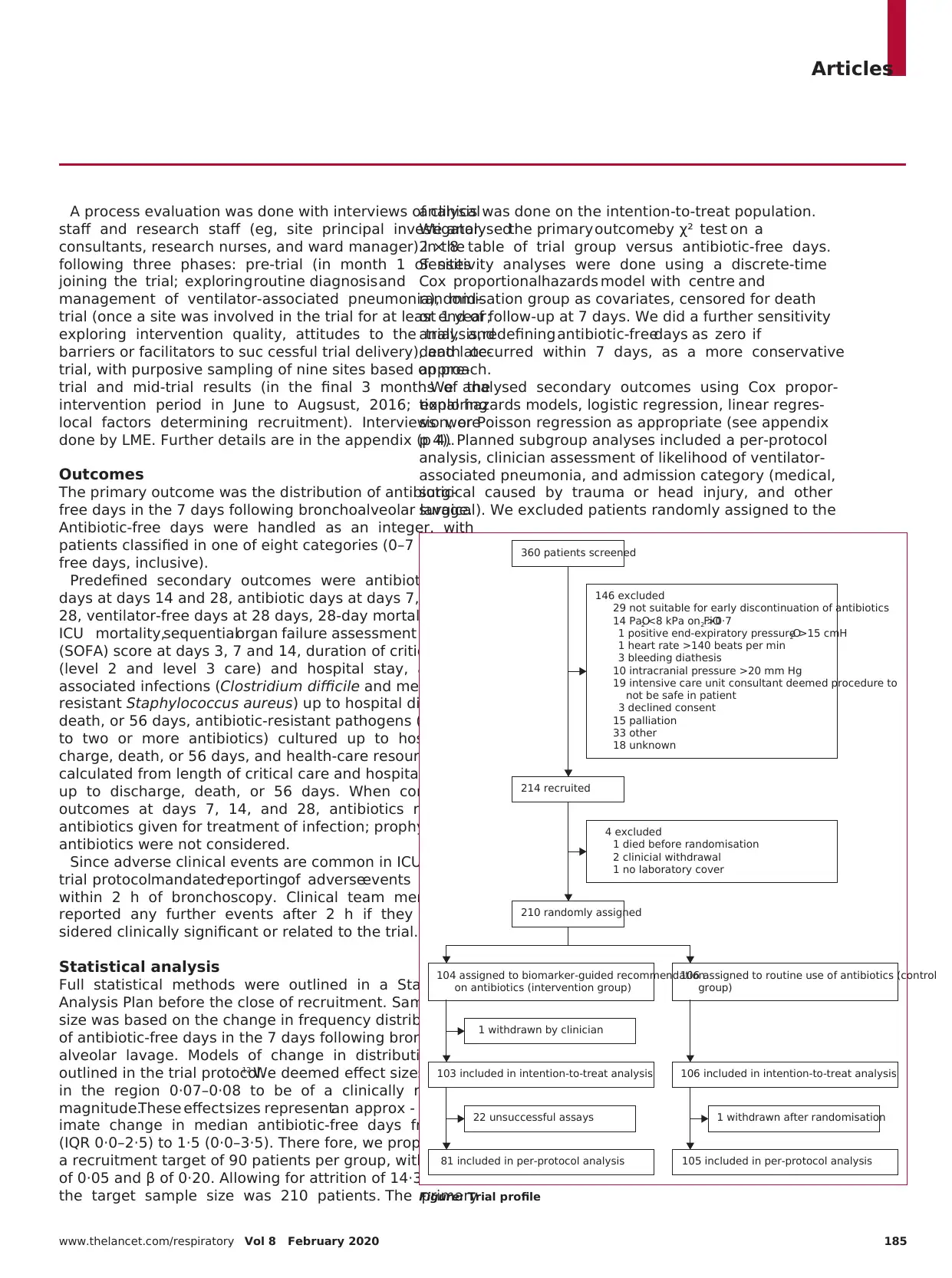

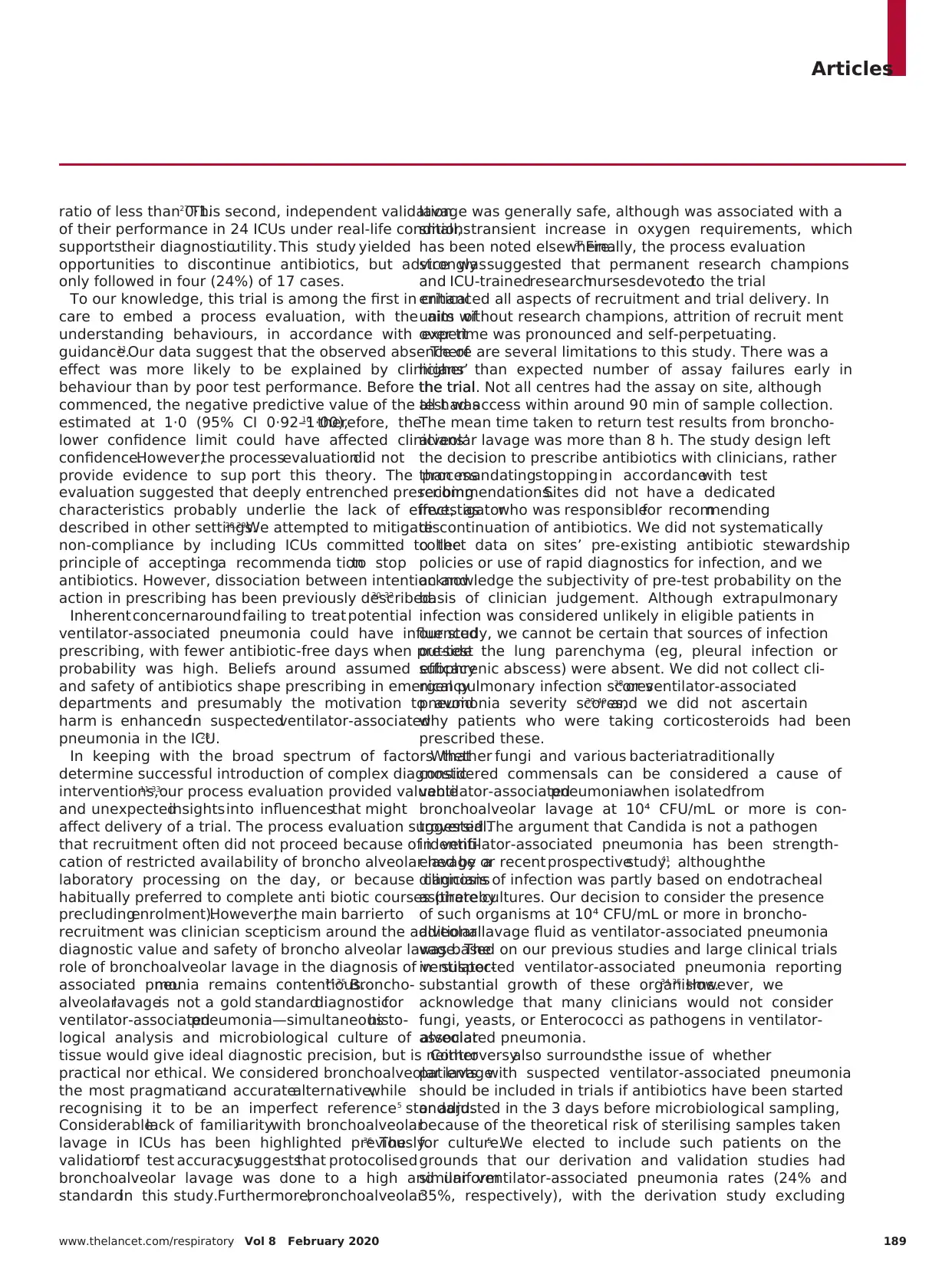

Figure: Trial profile

1 withdrawn by clinician

104 assigned to biomarker-guided recommendation

on antibiotics (intervention group)

103 included in intention-to-treat analysis

81 included in per-protocol analysis

22 unsuccessful assays

106 assigned to routine use of antibiotics (control

group)

106 included in intention-to-treat analysis

105 included in per-protocol analysis

1 withdrawn after randomisation

210 randomly assigned

214 recruited

360 patients screened

4 excluded

1 died before randomisation

2 clinicial withdrawal

1 no laboratory cover

146 excluded

29 not suitable for early discontinuation of antibiotics

14 PaO2 <8 kPa on FiO2 >0·7

1 positive end-expiratory pressure >15 cmH2O

1 heart rate >140 beats per min

3 bleeding diathesis

10 intracranial pressure >20 mm Hg

19 intensive care unit consultant deemed procedure to

not be safe in patient

3 declined consent

15 palliation

33 other

18 unknown

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 185

A process evaluation was done with interviews of clinical

staff and research staff (eg, site principal investigator,

consultants, research nurses, and ward manager) in the

following three phases: pre-trial (in month 1 of sites

joining the trial; exploring routine diagnosis and

management of ventilator-associated pneumonia), mid-

trial (once a site was involved in the trial for at least 1 year;

exploring intervention quality, attitudes to the trial, and

barriers or facilitators to suc cessful trial delivery), and late-

trial, with purposive sampling of nine sites based on pre-

trial and mid-trial results (in the final 3 months of the

intervention period in June to Augsust, 2016; exploring

local factors determining recruitment). Interviews were

done by LME. Further details are in the appendix (p 4).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the distribution of antibiotic-

free days in the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage.

Antibiotic-free days were handled as an integer, with

patients classified in one of eight categories (0–7 antibiotic-

free days, inclusive).

Predefined secondary outcomes were antibiotic-free

days at days 14 and 28, antibiotic days at days 7, 14, and

28, ventilator-free days at 28 days, 28-day mortality and

ICU mortality,sequentialorgan failure assessment

(SOFA) score at days 3, 7 and 14, duration of critical care

(level 2 and level 3 care) and hospital stay, antibiotic-

associated infections (Clostridium difficile and meticillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus) up to hospital discharge,

death, or 56 days, antibiotic-resistant pathogens (resistant

to two or more antibiotics) cultured up to hospital dis-

charge, death, or 56 days, and health-care resource use

calculated from length of critical care and hospital stay

up to discharge, death, or 56 days. When considering

outcomes at days 7, 14, and 28, antibiotics refers to all

antibiotics given for treatment of infection; prophylactic

antibiotics were not considered.

Since adverse clinical events are common in ICUs, the

trial protocolmandatedreportingof adverseevents

within 2 h of bronchoscopy. Clinical team members

reported any further events after 2 h if they were con-

sidered clinically significant or related to the trial.

Statistical analysis

Full statistical methods were outlined in a Statistical

Analysis Plan before the close of recruitment. Sample

size was based on the change in frequency distribution

of antibiotic-free days in the 7 days following broncho-

alveolar lavage. Models of change in distribution are

outlined in the trial protocol.12 We deemed effect sizes

in the region 0·07–0·08 to be of a clinically relevant

magnitude.These effect sizes representan approx -

imate change in median antibiotic-free days from 0

(IQR 0·0–2·5) to 1·5 (0·0–3·5). There fore, we proposed

a recruitment target of 90 patients per group, with an α

of 0·05 and β of 0·20. Allowing for attrition of 14·3%,

the target sample size was 210 patients. The primary

analysis was done on the intention-to-treat population.

We analysedthe primary outcomeby χ² test on a

2 × 8 table of trial group versus antibiotic-free days.

Sensitivity analyses were done using a discrete-time

Cox proportionalhazards model with centre and

randomisation group as covariates, censored for death

or end of follow-up at 7 days. We did a further sensitivity

analysis, redefining antibiotic-freedays as zero if

death occurred within 7 days, as a more conservative

approach.

We analysed secondary outcomes using Cox propor-

tional hazards models, logistic regression, linear regres-

sion, or Poisson regression as appropriate (see appendix

p 4). Planned subgroup analyses included a per-protocol

analysis, clinician assessment of likelihood of ventilator-

associated pneumonia, and admission category (medical,

surgical caused by trauma or head injury, and other

surgical). We excluded patients randomly assigned to the

Figure: Trial profile

1 withdrawn by clinician

104 assigned to biomarker-guided recommendation

on antibiotics (intervention group)

103 included in intention-to-treat analysis

81 included in per-protocol analysis

22 unsuccessful assays

106 assigned to routine use of antibiotics (control

group)

106 included in intention-to-treat analysis

105 included in per-protocol analysis

1 withdrawn after randomisation

210 randomly assigned

214 recruited

360 patients screened

4 excluded

1 died before randomisation

2 clinicial withdrawal

1 no laboratory cover

146 excluded

29 not suitable for early discontinuation of antibiotics

14 PaO2 <8 kPa on FiO2 >0·7

1 positive end-expiratory pressure >15 cmH2O

1 heart rate >140 beats per min

3 bleeding diathesis

10 intracranial pressure >20 mm Hg

19 intensive care unit consultant deemed procedure to

not be safe in patient

3 declined consent

15 palliation

33 other

18 unknown

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Articles

186 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

interventiongroup who defaultedto routine use of

antibiotics from the per-protocol analysis because th

did not return a biomarker result.

We assessed the prevalence of missing data during a

masked review after database lock, which was judg

to be of sufficiently low frequency as to not requir

imputation for all variables. However, as prespecified in

the Statistical Analysis Plan, SOFA scores were based on

the last evaluable score. Unadjusted CIs and p values ar

reported for multiplicity.

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation

Trust acted as sponsor for the trial. Clinical trial manage

ment was providedby the NCTU. An independent

data monitoring and safety committee oversaw the trial

(appendix p 3).

Analyses were done with R version 3.3.2, with the

addition of the discSurv package (version 1.3.4). Th

study is registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN65937227, and

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01972425.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, dat

collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing

the report. The corresponding author had full access to

all the data in the study and had final responsibility for

the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between Nov 6, 2013, and Sept 13, 2016, 360 patients

screened for inclusion in the study. 146 patients w

ineligible, leaving 214 who were recruited to the st

Four patientswere excludedbefore randomisation,

meaning that 210 patients were randomly assigned

biomarker-guided recommendation on antibiotics (n=10

or routine use of antibiotics (n=106; figure). One patien

in the biomarker-guidedrecommendationgroup was

withdrawn by the clinical team once baseline data

collected but before bronchoscopy, so was excluded fro

the intention-to-treat analysis.

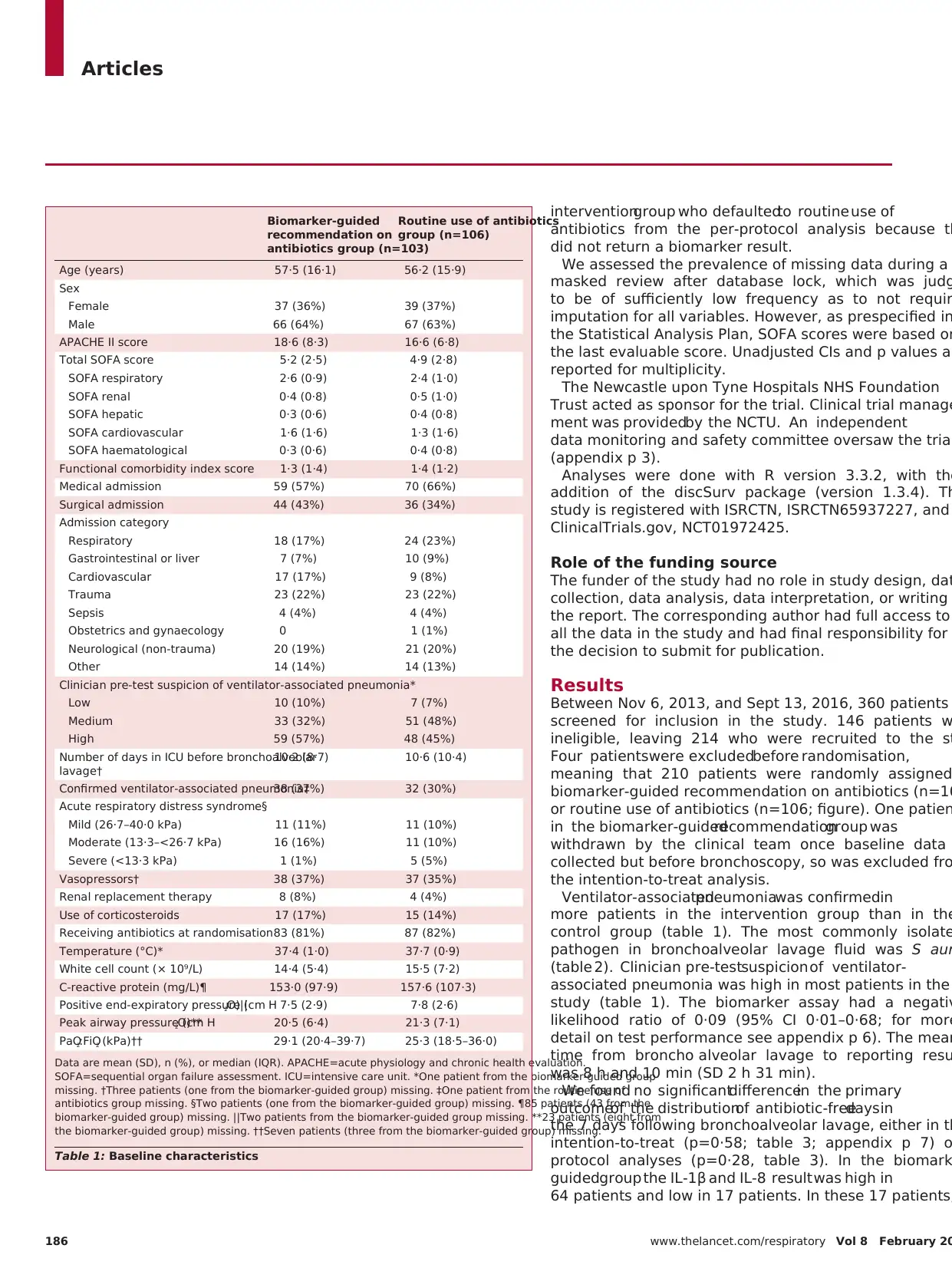

Ventilator-associatedpneumoniawas confirmedin

more patients in the intervention group than in the

control group (table 1). The most commonly isolate

pathogen in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was S aur

(table 2). Clinician pre-testsuspicion of ventilator-

associated pneumonia was high in most patients in the

study (table 1). The biomarker assay had a negativ

likelihood ratio of 0·09 (95% CI 0·01–0·68; for more

detail on test performance see appendix p 6). The mean

time from broncho alveolar lavage to reporting resu

was 8 h and 10 min (SD 2 h 31 min).

We found no significantdifferencein the primary

outcomeof the distributionof antibiotic-freedays in

the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage, either in th

intention-to-treat (p=0·58; table 3; appendix p 7) o

protocol analyses (p=0·28, table 3). In the biomark

guidedgroup the IL-1β and IL-8 result was high in

64 patients and low in 17 patients. In these 17 patients,

Biomarker-guided

recommendation on

antibiotics group (n=103)

Routine use of antibiotics

group (n=106)

Age (years) 57·5 (16·1) 56·2 (15·9)

Sex

Female 37 (36%) 39 (37%)

Male 66 (64%) 67 (63%)

APACHE II score 18·6 (8·3) 16·6 (6·8)

Total SOFA score 5·2 (2·5) 4·9 (2·8)

SOFA respiratory 2·6 (0·9) 2·4 (1·0)

SOFA renal 0·4 (0·8) 0·5 (1·0)

SOFA hepatic 0·3 (0·6) 0·4 (0·8)

SOFA cardiovascular 1·6 (1·6) 1·3 (1·6)

SOFA haematological 0·3 (0·6) 0·4 (0·8)

Functional comorbidity index score 1·3 (1·4) 1·4 (1·2)

Medical admission 59 (57%) 70 (66%)

Surgical admission 44 (43%) 36 (34%)

Admission category

Respiratory 18 (17%) 24 (23%)

Gastrointestinal or liver 7 (7%) 10 (9%)

Cardiovascular 17 (17%) 9 (8%)

Trauma 23 (22%) 23 (22%)

Sepsis 4 (4%) 4 (4%)

Obstetrics and gynaecology 0 1 (1%)

Neurological (non-trauma) 20 (19%) 21 (20%)

Other 14 (14%) 14 (13%)

Clinician pre-test suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia*

Low 10 (10%) 7 (7%)

Medium 33 (32%) 51 (48%)

High 59 (57%) 48 (45%)

Number of days in ICU before bronchoalveolar

lavage†

10·2 (8·7) 10·6 (10·4)

Confirmed ventilator-associated pneumonia‡38 (37%) 32 (30%)

Acute respiratory distress syndrome§

Mild (26·7–40·0 kPa) 11 (11%) 11 (10%)

Moderate (13·3–<26·7 kPa) 16 (16%) 11 (10%)

Severe (<13·3 kPa) 1 (1%) 5 (5%)

Vasopressors† 38 (37%) 37 (35%)

Renal replacement therapy 8 (8%) 4 (4%)

Use of corticosteroids 17 (17%) 15 (14%)

Receiving antibiotics at randomisation83 (81%) 87 (82%)

Temperature (°C)* 37·4 (1·0) 37·7 (0·9)

White cell count (× 10⁹/L) 14·4 (5·4) 15·5 (7·2)

C-reactive protein (mg/L)¶ 153·0 (97·9) 157·6 (107·3)

Positive end-expiratory pressure (cm H2O)|| 7·5 (2·9) 7·8 (2·6)

Peak airway pressure (cm H2O)** 20·5 (6·4) 21·3 (7·1)

PaO2:FiO2 (kPa)†† 29·1 (20·4–39·7) 25·3 (18·5–36·0)

Data are mean (SD), n (%), or median (IQR). APACHE=acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

SOFA=sequential organ failure assessment. ICU=intensive care unit. *One patient from the biomarker-guided group

missing. †Three patients (one from the biomarker-guided group) missing. ‡One patient from the routine use of

antibiotics group missing. §Two patients (one from the biomarker-guided group) missing. ¶85 patients (43 from the

biomarker-guided group) missing. ||Two patients from the biomarker-guided group missing. **23 patients (eight from

the biomarker-guided group) missing. ††Seven patients (three from the biomarker-guided group) missing.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

186 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

interventiongroup who defaultedto routine use of

antibiotics from the per-protocol analysis because th

did not return a biomarker result.

We assessed the prevalence of missing data during a

masked review after database lock, which was judg

to be of sufficiently low frequency as to not requir

imputation for all variables. However, as prespecified in

the Statistical Analysis Plan, SOFA scores were based on

the last evaluable score. Unadjusted CIs and p values ar

reported for multiplicity.

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation

Trust acted as sponsor for the trial. Clinical trial manage

ment was providedby the NCTU. An independent

data monitoring and safety committee oversaw the trial

(appendix p 3).

Analyses were done with R version 3.3.2, with the

addition of the discSurv package (version 1.3.4). Th

study is registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN65937227, and

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01972425.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, dat

collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing

the report. The corresponding author had full access to

all the data in the study and had final responsibility for

the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between Nov 6, 2013, and Sept 13, 2016, 360 patients

screened for inclusion in the study. 146 patients w

ineligible, leaving 214 who were recruited to the st

Four patientswere excludedbefore randomisation,

meaning that 210 patients were randomly assigned

biomarker-guided recommendation on antibiotics (n=10

or routine use of antibiotics (n=106; figure). One patien

in the biomarker-guidedrecommendationgroup was

withdrawn by the clinical team once baseline data

collected but before bronchoscopy, so was excluded fro

the intention-to-treat analysis.

Ventilator-associatedpneumoniawas confirmedin

more patients in the intervention group than in the

control group (table 1). The most commonly isolate

pathogen in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was S aur

(table 2). Clinician pre-testsuspicion of ventilator-

associated pneumonia was high in most patients in the

study (table 1). The biomarker assay had a negativ

likelihood ratio of 0·09 (95% CI 0·01–0·68; for more

detail on test performance see appendix p 6). The mean

time from broncho alveolar lavage to reporting resu

was 8 h and 10 min (SD 2 h 31 min).

We found no significantdifferencein the primary

outcomeof the distributionof antibiotic-freedays in

the 7 days following bronchoalveolar lavage, either in th

intention-to-treat (p=0·58; table 3; appendix p 7) o

protocol analyses (p=0·28, table 3). In the biomark

guidedgroup the IL-1β and IL-8 result was high in

64 patients and low in 17 patients. In these 17 patients,

Biomarker-guided

recommendation on

antibiotics group (n=103)

Routine use of antibiotics

group (n=106)

Age (years) 57·5 (16·1) 56·2 (15·9)

Sex

Female 37 (36%) 39 (37%)

Male 66 (64%) 67 (63%)

APACHE II score 18·6 (8·3) 16·6 (6·8)

Total SOFA score 5·2 (2·5) 4·9 (2·8)

SOFA respiratory 2·6 (0·9) 2·4 (1·0)

SOFA renal 0·4 (0·8) 0·5 (1·0)

SOFA hepatic 0·3 (0·6) 0·4 (0·8)

SOFA cardiovascular 1·6 (1·6) 1·3 (1·6)

SOFA haematological 0·3 (0·6) 0·4 (0·8)

Functional comorbidity index score 1·3 (1·4) 1·4 (1·2)

Medical admission 59 (57%) 70 (66%)

Surgical admission 44 (43%) 36 (34%)

Admission category

Respiratory 18 (17%) 24 (23%)

Gastrointestinal or liver 7 (7%) 10 (9%)

Cardiovascular 17 (17%) 9 (8%)

Trauma 23 (22%) 23 (22%)

Sepsis 4 (4%) 4 (4%)

Obstetrics and gynaecology 0 1 (1%)

Neurological (non-trauma) 20 (19%) 21 (20%)

Other 14 (14%) 14 (13%)

Clinician pre-test suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia*

Low 10 (10%) 7 (7%)

Medium 33 (32%) 51 (48%)

High 59 (57%) 48 (45%)

Number of days in ICU before bronchoalveolar

lavage†

10·2 (8·7) 10·6 (10·4)

Confirmed ventilator-associated pneumonia‡38 (37%) 32 (30%)

Acute respiratory distress syndrome§

Mild (26·7–40·0 kPa) 11 (11%) 11 (10%)

Moderate (13·3–<26·7 kPa) 16 (16%) 11 (10%)

Severe (<13·3 kPa) 1 (1%) 5 (5%)

Vasopressors† 38 (37%) 37 (35%)

Renal replacement therapy 8 (8%) 4 (4%)

Use of corticosteroids 17 (17%) 15 (14%)

Receiving antibiotics at randomisation83 (81%) 87 (82%)

Temperature (°C)* 37·4 (1·0) 37·7 (0·9)

White cell count (× 10⁹/L) 14·4 (5·4) 15·5 (7·2)

C-reactive protein (mg/L)¶ 153·0 (97·9) 157·6 (107·3)

Positive end-expiratory pressure (cm H2O)|| 7·5 (2·9) 7·8 (2·6)

Peak airway pressure (cm H2O)** 20·5 (6·4) 21·3 (7·1)

PaO2:FiO2 (kPa)†† 29·1 (20·4–39·7) 25·3 (18·5–36·0)

Data are mean (SD), n (%), or median (IQR). APACHE=acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

SOFA=sequential organ failure assessment. ICU=intensive care unit. *One patient from the biomarker-guided group

missing. †Three patients (one from the biomarker-guided group) missing. ‡One patient from the routine use of

antibiotics group missing. §Two patients (one from the biomarker-guided group) missing. ¶85 patients (43 from the

biomarker-guided group) missing. ||Two patients from the biomarker-guided group missing. **23 patients (eight from

the biomarker-guided group) missing. ††Seven patients (three from the biomarker-guided group) missing.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

Articles

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 187

recommendation to discontinue antibiotics was followed

in four (24%) patients, and a false negative result was

obtainedin one (6%) patient.Microbiologicaldetails

relating to bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from the 17 patients

with a low IL-1β and IL-8 result (ie, those eligible for

antibiotic discontinuation) are shown in the appendix (p 8).

We observed no significant differences between the

groups for all other secondary outcomes (table 4). Results

for subgroup analyses,per-protocolanalyses, and

antibiotic-resistantinfections are shown in the

appendix (pp 10–17). Our two sensitivity analyses—one

treating death as equivalent to zero antibiotic-free days

and the other censoring at death in a discrete-time Cox

model—revealed no difference in the primary outcome

in the intention-to-treat population (appendix p 9).

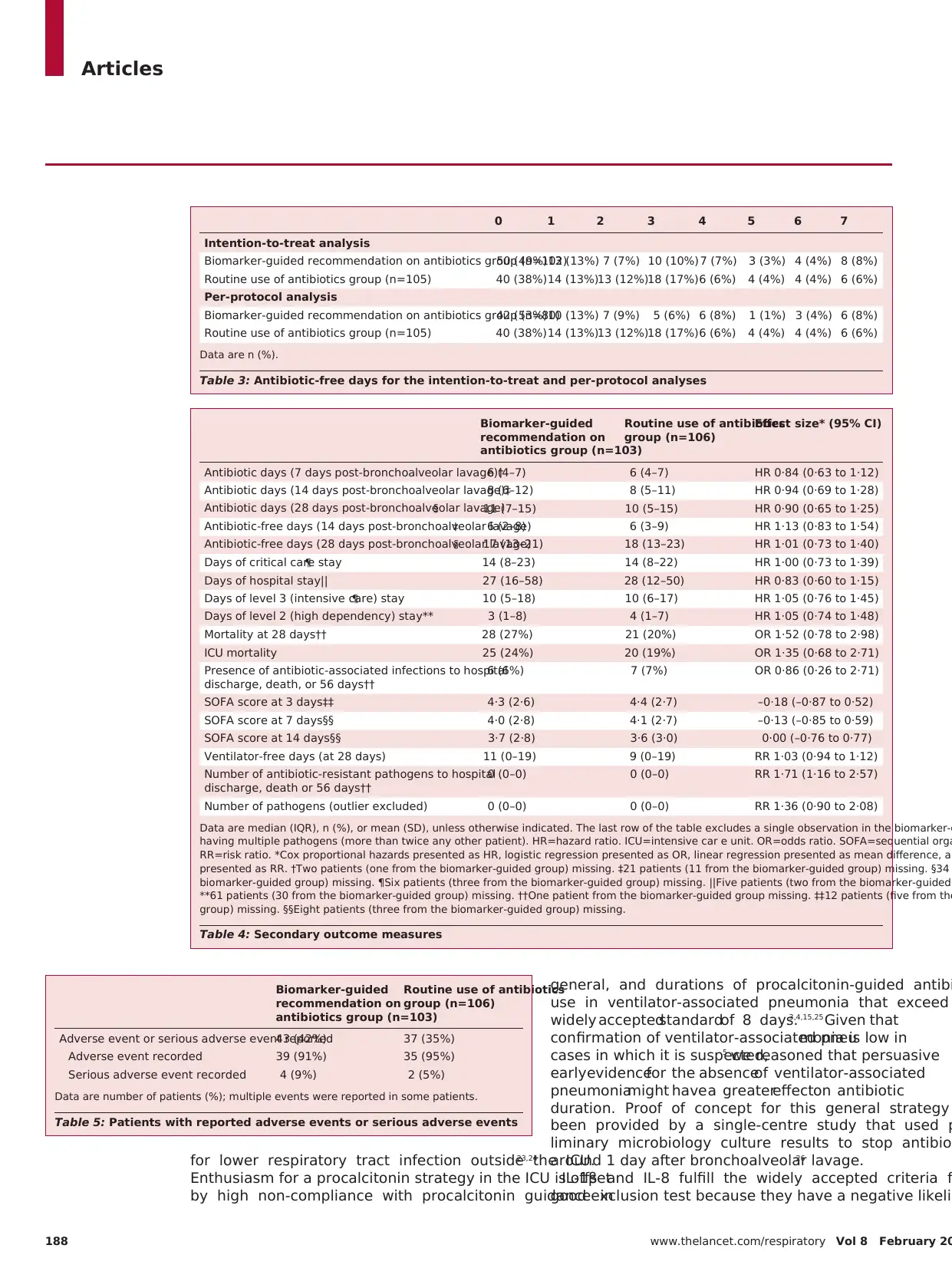

Zero antibiotic-freedays was the most frequent

prescribing outcome (table 3). Median antibiotic days at

day 7 were 6 (IQR 4–7) in both groups (hazard ratio [HR]

0·84, 95% CI 0·63–1·12; table 4). We found no between-

group differences in antibiotic-free days at 14 days or

28 days (table 4). Reported indications for antibiotics

are described in the appendix (pp 18–19).

Numbers of patients with one or more reported adverse

events or serious adverse events are shown in table 5.

Details of adverse events and serious adverse events are

shown in the appendix (p 20). Bronchoalveolar lavage

was associated with a small, transient increase in oxygen

requirements (appendix p 21).

In the 13 patientsin whom the discontinuation

recommendation was not followed, our process evalu-

ation suggestedthat perceivedventilator-associated

pneu monia or hospital-acquired pneumonia was the

most common reason for antibiotic use. The process

evaluationidentifiedtwo broad potentiallynegative

influences on recruitment to the trial and compliance

with the trial intervention. The first of these influences

suggestedthat the chain involving identificationof

potential participants, preparation for bronchoalveolar

lavage, laboratory processing, and a clinician making a

judgement on the basis of the recommendation, intro-

duced many opportunitiesfor deviationfrom the

model. A breakdown in this sequence, at any stage,

negatively affected site performance and implement-

ation of the intervention.Second, we identified a

pattern such that low recruitment by units appeared to

correspondwith less use of bronchoalveolarlavage

in the diagnosisof ventilator-associatedpneumonia

outside the trial, a culture of not actively de-escalating

antibiotics, and the absence of so-called trial champions

(designated as having a particular interest in promoting

and delivering the trial within a given unit). These

same units also described a greater perception of risk

for bronchoalveolarlavage(favouringless invasive

methods) and for discontinuing antibiotics (favouring

antibiotic use as the perceived lower-risk approach). For

further details of the process evaluationsee the

appendix (pp 22–24).

Discussion

In the VAPrapid2 trial, a validated test with good rule-out

characteristics for ventilator-associated pneumonia did not

reduceantibioticuse or improveany of our other

investigated clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, this is

the first trial to use biomarkers to exclude ventilator-

associatedpneumoniato increaseconfidencein early

discontinuation of empirical antibiotics. Previous studies

have shown proof of principlefor modestantibiotic

reduction in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia

using discontinuation rules.14,15 Serum procalcitonin has

been studiedwidelyin the ICU (outside thespecific

contextof ventilator-associatedpneumonia)and this

approachshowedvaryingsuccessfor safelyadjusting

antibiotic use.16–20However, procalcitonin is ineffective for

the exclusion of ventilator-associated pneumonia,21,22which

was the focus of our approach. Inconsistent effects of

procalcitonin on antibiotic use have also been des cribed

Ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

(≥10⁴ CFU/mL;

n=70)

Non-ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

(<10⁴ CFU/mL;

n=139)

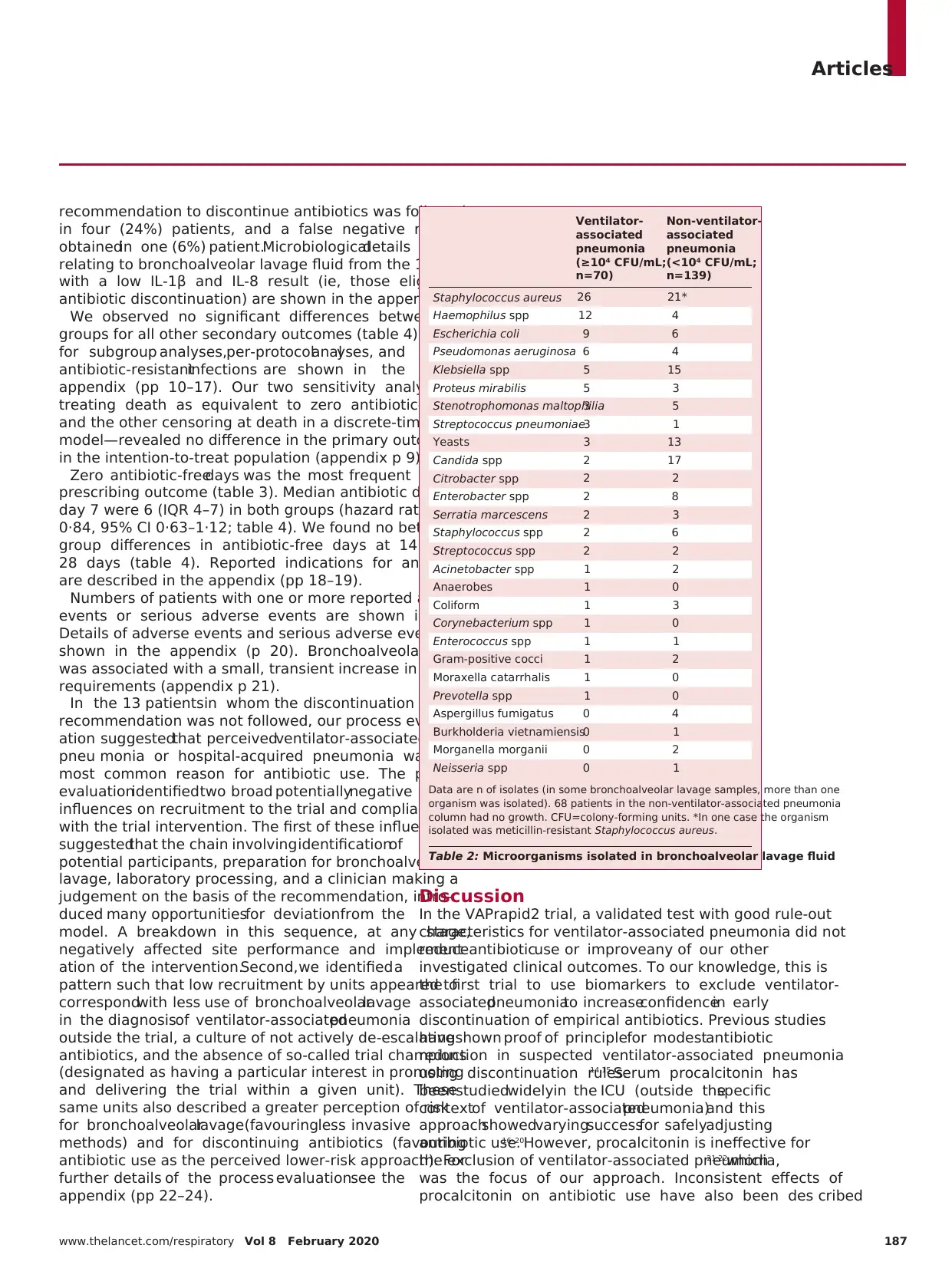

Staphylococcus aureus 26 21*

Haemophilus spp 12 4

Escherichia coli 9 6

Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6 4

Klebsiella spp 5 15

Proteus mirabilis 5 3

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia3 5

Streptococcus pneumoniae3 1

Yeasts 3 13

Candida spp 2 17

Citrobacter spp 2 2

Enterobacter spp 2 8

Serratia marcescens 2 3

Staphylococcus spp 2 6

Streptococcus spp 2 2

Acinetobacter spp 1 2

Anaerobes 1 0

Coliform 1 3

Corynebacterium spp 1 0

Enterococcus spp 1 1

Gram-positive cocci 1 2

Moraxella catarrhalis 1 0

Prevotella spp 1 0

Aspergillus fumigatus 0 4

Burkholderia vietnamiensis0 1

Morganella morganii 0 2

Neisseria spp 0 1

Data are n of isolates (in some bronchoalveolar lavage samples, more than one

organism was isolated). 68 patients in the non-ventilator-associated pneumonia

column had no growth. CFU=colony-forming units. *In one case the organism

isolated was meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 2: Microorganisms isolated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 2020 187

recommendation to discontinue antibiotics was followed

in four (24%) patients, and a false negative result was

obtainedin one (6%) patient.Microbiologicaldetails

relating to bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from the 17 patients

with a low IL-1β and IL-8 result (ie, those eligible for

antibiotic discontinuation) are shown in the appendix (p 8).

We observed no significant differences between the

groups for all other secondary outcomes (table 4). Results

for subgroup analyses,per-protocolanalyses, and

antibiotic-resistantinfections are shown in the

appendix (pp 10–17). Our two sensitivity analyses—one

treating death as equivalent to zero antibiotic-free days

and the other censoring at death in a discrete-time Cox

model—revealed no difference in the primary outcome

in the intention-to-treat population (appendix p 9).

Zero antibiotic-freedays was the most frequent

prescribing outcome (table 3). Median antibiotic days at

day 7 were 6 (IQR 4–7) in both groups (hazard ratio [HR]

0·84, 95% CI 0·63–1·12; table 4). We found no between-

group differences in antibiotic-free days at 14 days or

28 days (table 4). Reported indications for antibiotics

are described in the appendix (pp 18–19).

Numbers of patients with one or more reported adverse

events or serious adverse events are shown in table 5.

Details of adverse events and serious adverse events are

shown in the appendix (p 20). Bronchoalveolar lavage

was associated with a small, transient increase in oxygen

requirements (appendix p 21).

In the 13 patientsin whom the discontinuation

recommendation was not followed, our process evalu-

ation suggestedthat perceivedventilator-associated

pneu monia or hospital-acquired pneumonia was the

most common reason for antibiotic use. The process

evaluationidentifiedtwo broad potentiallynegative

influences on recruitment to the trial and compliance

with the trial intervention. The first of these influences

suggestedthat the chain involving identificationof

potential participants, preparation for bronchoalveolar

lavage, laboratory processing, and a clinician making a

judgement on the basis of the recommendation, intro-

duced many opportunitiesfor deviationfrom the

model. A breakdown in this sequence, at any stage,

negatively affected site performance and implement-

ation of the intervention.Second, we identified a

pattern such that low recruitment by units appeared to

correspondwith less use of bronchoalveolarlavage

in the diagnosisof ventilator-associatedpneumonia

outside the trial, a culture of not actively de-escalating

antibiotics, and the absence of so-called trial champions

(designated as having a particular interest in promoting

and delivering the trial within a given unit). These

same units also described a greater perception of risk

for bronchoalveolarlavage(favouringless invasive

methods) and for discontinuing antibiotics (favouring

antibiotic use as the perceived lower-risk approach). For

further details of the process evaluationsee the

appendix (pp 22–24).

Discussion

In the VAPrapid2 trial, a validated test with good rule-out

characteristics for ventilator-associated pneumonia did not

reduceantibioticuse or improveany of our other

investigated clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, this is

the first trial to use biomarkers to exclude ventilator-

associatedpneumoniato increaseconfidencein early

discontinuation of empirical antibiotics. Previous studies

have shown proof of principlefor modestantibiotic

reduction in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia

using discontinuation rules.14,15 Serum procalcitonin has

been studiedwidelyin the ICU (outside thespecific

contextof ventilator-associatedpneumonia)and this

approachshowedvaryingsuccessfor safelyadjusting

antibiotic use.16–20However, procalcitonin is ineffective for

the exclusion of ventilator-associated pneumonia,21,22which

was the focus of our approach. Inconsistent effects of

procalcitonin on antibiotic use have also been des cribed

Ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

(≥10⁴ CFU/mL;

n=70)

Non-ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

(<10⁴ CFU/mL;

n=139)

Staphylococcus aureus 26 21*

Haemophilus spp 12 4

Escherichia coli 9 6

Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6 4

Klebsiella spp 5 15

Proteus mirabilis 5 3

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia3 5

Streptococcus pneumoniae3 1

Yeasts 3 13

Candida spp 2 17

Citrobacter spp 2 2

Enterobacter spp 2 8

Serratia marcescens 2 3

Staphylococcus spp 2 6

Streptococcus spp 2 2

Acinetobacter spp 1 2

Anaerobes 1 0

Coliform 1 3

Corynebacterium spp 1 0

Enterococcus spp 1 1

Gram-positive cocci 1 2

Moraxella catarrhalis 1 0

Prevotella spp 1 0

Aspergillus fumigatus 0 4

Burkholderia vietnamiensis0 1

Morganella morganii 0 2

Neisseria spp 0 1

Data are n of isolates (in some bronchoalveolar lavage samples, more than one

organism was isolated). 68 patients in the non-ventilator-associated pneumonia

column had no growth. CFU=colony-forming units. *In one case the organism

isolated was meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 2: Microorganisms isolated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Articles

188 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 8 February 20

for lower respiratory tract infection outside the ICU.23,24