Examining Advertising and Sales Promotions' Influence on Brand Equity

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/13

|8

|11069

|141

Report

AI Summary

This academic paper, published in the Journal of Business Research, investigates the relationship between advertising and sales promotions and their impact on brand equity. The study, based on a survey of 302 UK consumers, explores how advertising spend and attitudes toward advertisements influence brand equity dimensions like awareness, associations, and perceived quality. It also examines the effects of monetary and non-monetary sales promotions, revealing that attitudes toward advertisements significantly impact brand equity, while advertising spend primarily boosts brand awareness. The research further suggests that companies can optimize brand equity management by understanding the interrelationships among different brand equity dimensions. The study builds on existing frameworks, providing insights into the evolving theory of brand equity and offering practical implications for marketing managers. The paper also explores the causal order among brand equity dimensions and highlights the importance of considering consumer-based brand equity measures when analyzing marketing mix effectiveness.

Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation☆

Isabel Buila,

⁎, Leslie de Chernatonyb, c, 1

, Eva Martíneza, 2

a University of Zaragoza,Spain

b Università della Svizzera italiana,Switzerland

c Aston Business School,UK

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 June 2010

Received in revised form 1 November 2010

Accepted 1 February 2011

Available online 10 August 2011

Keywords:

Advertising

Sales promotions

Brand equity dimensions

This study explores the relationships between two central elements of marketing communication programs

advertising and sales promotions — and their impact on brand equity creation.In particular,the research

focuses on advertising spend and individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements.The study also inves-

tigates the effects of two kinds of sales promotions,monetary and non-monetary promotions.Based on a

survey of 302 UK consumers, findings show that the individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements play a

key role influencing brand equity dimensions, whereas advertising spend for the brands under investigation

improves brand awareness but is insufficient to positively influence brand associations and perceived qualit

The paper also finds distinctive effects ofmonetary and non-monetary promotions on brand equity.In

addition, the results show that companies can optimize the brand equity management process by consideri

the relationships existing between the different dimensions of brand equity.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Both practitioners and academics regard brand equity as an

important concept (Keller and Lehmann, 2006). Elements of a brand's

equity positively influence consumers'perceptions and subsequent

brand buying behaviors (Reynolds and Phillips,2005).Therefore,to

increase the likelihood of such positive contributions and manage

brands properly, companies need to develop strategies which encour-

age the growth of brand equity (Keller,2007). In this context,the

identification offactors that build brand equity represents a central

priority for academics and marketing managers (Baldauf et al.,2009;

Valette-Florence et al., 2011).

Previous research suggests that marketing mix elements are key

variables in building brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000). As such, one

of the major challenges marketers face is deciding on the optimum

marketing budget to achieve both the highest impact on the target

market (Soberman,2009) and the brand (Ataman et al., 2010).

Although considerable research examines the effectiveness ofdif-

ferent elements of the marketing mix on brand equity,as Keller and

Lehmann (2006,p. 747) state,these researchers “have not typically

addressed the fullbreadth ofbrand equity dimensions”.Few studies

include consumer-based brand equity measures (i.e.,mindset mea-

sures) when analyzing marketing mix effectiveness.One of the ex-

ceptions is Yoo et al.(2000) who explore the relationships between

selected marketing mix elements and consumer-based brand equity.

While their research provides new insights into how marketing ac-

tivities may influence brand equity,these authors advocate further

exploration of the impact of the different marketing mix variables.

Two marketing variables are of particular interest: advertising and

sales promotions.Compared to other forms of marketing activity,ex-

penditures on advertising and promotions are significant. For instance,

these two variables account for approximately 1.5% of the UK's gross

domestic product (West and Prendergast,2009). Despite their impor-

tance, the individual contributions of advertising and sales promotions

to brand equity remain unclear and scholars highlight the need to

further examine the effect of these variables (Netemeyer et al.,2004;

Chu and Keh, 2006). Therefore, this study addresses this request.

Another area for improving understanding about consumer-based

brand equity is the interaction between brand equity dimensions.

Generally,researchers propose associative relationships among the

consumer-based brand equity dimensions (e.g.,Yoo and Donthu,

2001; Pappu et al.,2005; Tong and Hawley,2009).However, several

authors advocate that researchers focus on the ordering among the

brand equity dimensions (Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and

Lehmann, 2006).

Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

☆ The authors thank the following sources for their financial help: I + D + I project

(Ref: ECO2009-08283) from the Governmentof Spain and the project “GENERES”

(Ref: S-09) from the Government ofAragon.The authors would also like to thank

Dr José M.Pina for his insightful comments and helpful suggestions.

⁎ Corresponding author at:Department ofMarketing Management,University of

Zaragoza,María de Luna s/n, Edificio Lorenzo Normante,50018 Zaragoza,Spain.

Tel.: +34 976 761000; fax: +34 976 761767.

E-mail addresses: ibuil@unizar.es (I.Buil), dechernatony@btinternet.com

(L. de Chernatony),emartine@unizar.es (E.Martínez).

1 Università della Svizzera italiana,Lugano,Switzerland and Aston Busines School,

Birmingham,UK. Tel.+44 790 508 8927; fax: +44 121 449 0104.

2 Department of Marketing Management,University of Zaragoza.Gran Vía 2,50005

Zaragoza,Spain.Tel.: +34 976 762713; fax: +34 976 761767.

0148-2963/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.030

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

Isabel Buila,

⁎, Leslie de Chernatonyb, c, 1

, Eva Martíneza, 2

a University of Zaragoza,Spain

b Università della Svizzera italiana,Switzerland

c Aston Business School,UK

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 June 2010

Received in revised form 1 November 2010

Accepted 1 February 2011

Available online 10 August 2011

Keywords:

Advertising

Sales promotions

Brand equity dimensions

This study explores the relationships between two central elements of marketing communication programs

advertising and sales promotions — and their impact on brand equity creation.In particular,the research

focuses on advertising spend and individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements.The study also inves-

tigates the effects of two kinds of sales promotions,monetary and non-monetary promotions.Based on a

survey of 302 UK consumers, findings show that the individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements play a

key role influencing brand equity dimensions, whereas advertising spend for the brands under investigation

improves brand awareness but is insufficient to positively influence brand associations and perceived qualit

The paper also finds distinctive effects ofmonetary and non-monetary promotions on brand equity.In

addition, the results show that companies can optimize the brand equity management process by consideri

the relationships existing between the different dimensions of brand equity.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Both practitioners and academics regard brand equity as an

important concept (Keller and Lehmann, 2006). Elements of a brand's

equity positively influence consumers'perceptions and subsequent

brand buying behaviors (Reynolds and Phillips,2005).Therefore,to

increase the likelihood of such positive contributions and manage

brands properly, companies need to develop strategies which encour-

age the growth of brand equity (Keller,2007). In this context,the

identification offactors that build brand equity represents a central

priority for academics and marketing managers (Baldauf et al.,2009;

Valette-Florence et al., 2011).

Previous research suggests that marketing mix elements are key

variables in building brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000). As such, one

of the major challenges marketers face is deciding on the optimum

marketing budget to achieve both the highest impact on the target

market (Soberman,2009) and the brand (Ataman et al., 2010).

Although considerable research examines the effectiveness ofdif-

ferent elements of the marketing mix on brand equity,as Keller and

Lehmann (2006,p. 747) state,these researchers “have not typically

addressed the fullbreadth ofbrand equity dimensions”.Few studies

include consumer-based brand equity measures (i.e.,mindset mea-

sures) when analyzing marketing mix effectiveness.One of the ex-

ceptions is Yoo et al.(2000) who explore the relationships between

selected marketing mix elements and consumer-based brand equity.

While their research provides new insights into how marketing ac-

tivities may influence brand equity,these authors advocate further

exploration of the impact of the different marketing mix variables.

Two marketing variables are of particular interest: advertising and

sales promotions.Compared to other forms of marketing activity,ex-

penditures on advertising and promotions are significant. For instance,

these two variables account for approximately 1.5% of the UK's gross

domestic product (West and Prendergast,2009). Despite their impor-

tance, the individual contributions of advertising and sales promotions

to brand equity remain unclear and scholars highlight the need to

further examine the effect of these variables (Netemeyer et al.,2004;

Chu and Keh, 2006). Therefore, this study addresses this request.

Another area for improving understanding about consumer-based

brand equity is the interaction between brand equity dimensions.

Generally,researchers propose associative relationships among the

consumer-based brand equity dimensions (e.g.,Yoo and Donthu,

2001; Pappu et al.,2005; Tong and Hawley,2009).However, several

authors advocate that researchers focus on the ordering among the

brand equity dimensions (Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and

Lehmann, 2006).

Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

☆ The authors thank the following sources for their financial help: I + D + I project

(Ref: ECO2009-08283) from the Governmentof Spain and the project “GENERES”

(Ref: S-09) from the Government ofAragon.The authors would also like to thank

Dr José M.Pina for his insightful comments and helpful suggestions.

⁎ Corresponding author at:Department ofMarketing Management,University of

Zaragoza,María de Luna s/n, Edificio Lorenzo Normante,50018 Zaragoza,Spain.

Tel.: +34 976 761000; fax: +34 976 761767.

E-mail addresses: ibuil@unizar.es (I.Buil), dechernatony@btinternet.com

(L. de Chernatony),emartine@unizar.es (E.Martínez).

1 Università della Svizzera italiana,Lugano,Switzerland and Aston Busines School,

Birmingham,UK. Tel.+44 790 508 8927; fax: +44 121 449 0104.

2 Department of Marketing Management,University of Zaragoza.Gran Vía 2,50005

Zaragoza,Spain.Tel.: +34 976 762713; fax: +34 976 761767.

0148-2963/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.030

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Within this context, the purpose of this article is twofold. First, to

shed more light on two particular drivers of brand equity: advertising

and sales promotions. In particular, the study focuses on advertising

spend and individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements.Simi-

larly, the research investigates the effects oftwo kinds of sales

promotions, monetary and non-monetary promotions.Second,to

explore the relationships among brand equity dimensions.

Building on the framework proposed by Yoo et al. (2000), the current

work goes beyond research on sources of brand equity in several ways.

First,most brand equity studies have simply focused on the influence

that advertising spend and frequency of monetary promotions have

on brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000; Villarejo and Sánchez, 2005; Bravo

et al.,2007; Valette-Florence et al.,2011).By contrast,this study also

analyzes individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements and non-

monetary promotions.Despite several scholars recognizing that other

advertising characteristicsbeyond just advertising spend,such as

individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements,play an important

role in growing brand equity (Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Keller and

Lehmann, 2003; 2006; Bravo et al., 2007; Sriram et al., 2007), research

on brand equity has traditionally ignored these attitudes.Similarly,

recent literature on sales promotions (e.g., Chandon et al., 2000) stresses

the need to differentiate between two types of promotions,monetary

and non-monetary promotions. Surprisingly, academic research into the

effects of non-monetary promotions on brand equity is scarce. Second,

this article analyzes the causal order among brand equity dimensions.

Several studies suggest a hierarchy in terms of the importance of brand

equity dimensions and potential causal order (Agarwal and Rao, 1996;

Maio Mackay, 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and Lehmann, 2003;

2006).However,few studies have empirically examined how brand

equity dimensions inter-relate. Analyzing all these aspects, this research

advances knowledge by providing more insight about the evolving

theory of brand equity.

This paper opens with a brief,general discussion of brand equity

and marketing mix elements followed by the hypotheses.Then,the

fourth section explains the methodology to testthe model. Next

section presents the results of the study. Finally, the paper concludes

by outlining the conclusions, implications and limitations of the

research.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1.Brand equity

Brand equity is a key issue in marketing.Despite receiving con-

siderable attention,no consensus exists aboutwhich are the best

measures to capture this complex and multi-faceted construct (Maio

Mackay, 2001; Raggio and Leone,2007). Part of the reason is the

different perspectives adopted to define and measure this concept

(Christodoulides and de Chernatony, 2010). The financial perspective

stresses the value of a brand to the firm (Simon and Sullivan,1993;

Feldwick, 1996). On the other hand, the consumer perspective focuses

the conceptualization and measurement of brand equity on individual

consumers (Leone et al.,2006).

Adopting the latter perspective,and from a cognitive psychology

approach,brand equity denotes the added value endowed by the

brand to the product (Farquhar,1989).Aaker (1991,p. 15) provides

one of the most accepted and comprehensive definitions ofbrand

equity: “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and

symbol that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or

service to a firm and/or to thatfirm's customers”.Keller (1993,p. 2)

proposes a similar definition: “the differential effect of brand knowledge

on consumer response to the marketing of the brand”.

Consumer-based brand equity measuresassessthe awareness,

attitudes,associations,attachmentsand loyalties consumershave

toward a brand (Keller and Lehmann,2006). These measures offer

considerable advantages such as the assessment of sources of brand

equity and its consequences, plus a diagnostic capability (Ailawadi et al.,

2003; Gupta and Zeithaml, 2006). In this sense, these measures act as

early evaluation signals about future performance (Srinivasan et al.,

2010).From this perspective,the two main frameworks that concep-

tualize brand equity are those ofAaker (1991) and Keller (1993).

According to Aaker (1991), brand equity is a multidimensional concept

whose first four core brand equity dimensions are brand awareness,

perceived quality,brand associations and brand loyalty.Brand equity

research omits the fifth of Aaker's dimensions, other proprietary brand

assets,since this component is not pertinent to consumers.Keller's

(1993) conceptualization focuses on brand knowledge and involves two

components: brand awareness and brand image.

Drawing on these theoretical proposals,a large number of studies

conceptualize and measure brand equity using the dimensions of brand

awareness, perceived quality, brand associations and brand loyalty (e.g.,

Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Yoo et al.,2000; Yoo and Donthu,2001;

Washburn and Plank, 2002; Ashill and Sinha, 2004; Pappu et al., 2005;

2006; Konecnik and Gartner,2007; Tong and Hawley,2009; Lee and

Back, 2010).

Following these two approaches,this research uses a consumer-

based brand equity measure that consists of four dimensions: brand

awareness,perceived quality, brand associations, and brand loyalty.

2.2.Marketing mix elements

Marketing mix elements influence consumers'equity perceptions

toward brands (Pappu and Quester, 2008). These variables are impor-

tant not only because they can greatly affect brand equity but also

because they are under companies' control, enabling marketers to grow

brand equity through their marketing activities (Keller,1993; Berry,

2000; Yoo et al., 2000; Ailawadi et al., 2003; Herrmann et al., 2007).

Within the discipline of marketing dynamics, numerous studies use

financial and product–market measures of brand equity to analyze the

short- and long-term effects of marketing actions and polices, such as

advertising and price promotions (Leeflang et al.,2009; Ataman et al.,

2010; Srinivasan et al., 2010).

From the consumer-based brand equity perspective, which

this research follows,Yoo et al. (2000) find that high advertising

spend,high price,high distribution intensity and distribution through

retailers with good store image would help build brand equity.By

contrast, frequent price promotions would harm brand equity. Villarejo

and Sánchez (2005) also focus their study on advertising spend and

price promotions,while Bravo et al.(2007) add to these variables the

effect of the price.

This study focuses on the role of two specific marketing com-

munications tools: advertising and sales promotions. These two

marketing elements account for at least 25% of UK marketing budgets

(Chartered Institute of Marketing,2009). Despite their importance,

the influence of these variables on brand equity still remains unclear

(Netemeyer et al.,2004; Chu and Keh, 2006). This research responds

to this gap by exploring their effects on consumer-based brand equity.

3. Research hypotheses

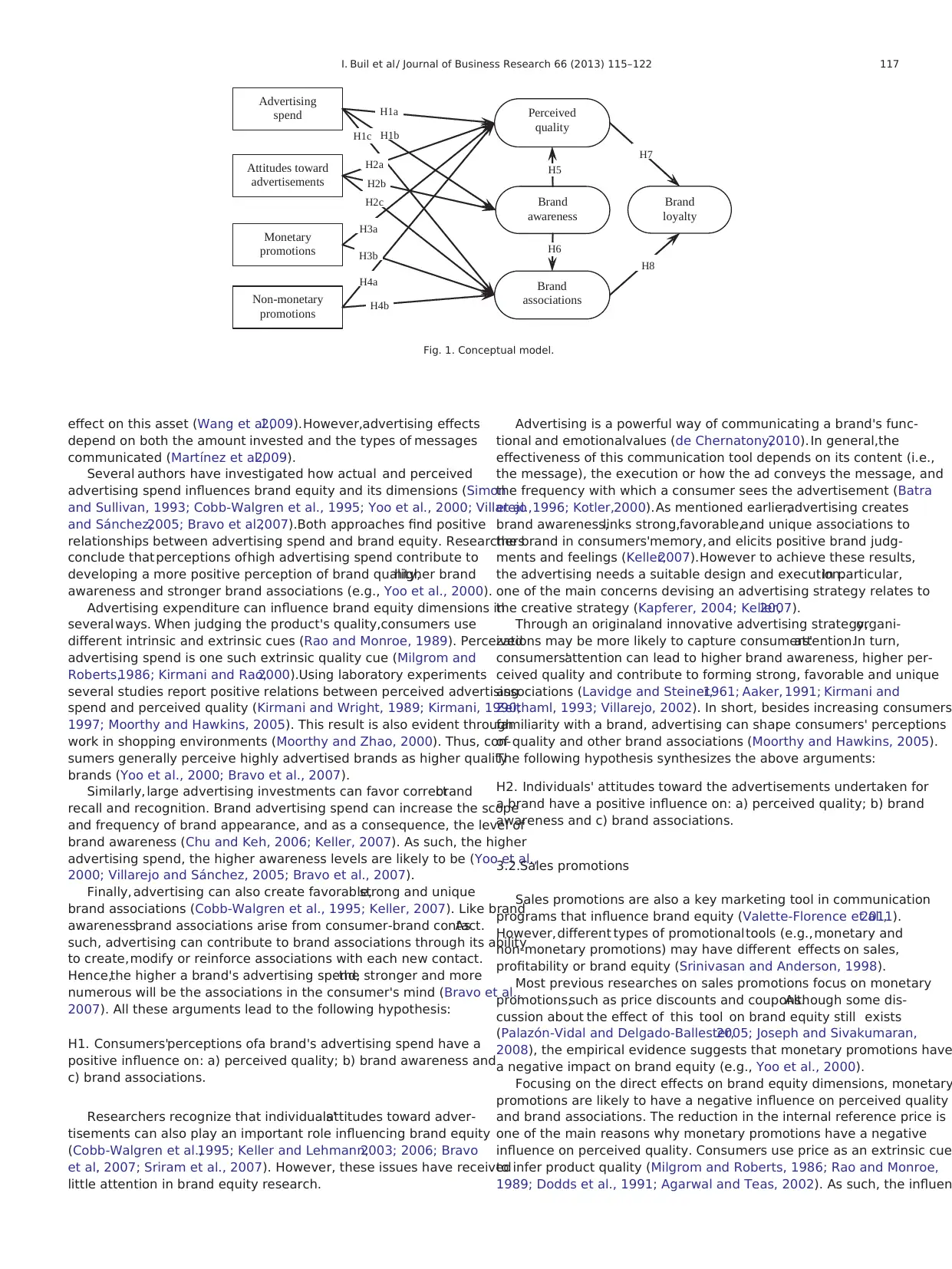

Fig. 1 shows the conceptualframework underlying this research.

This study addresses how advertising spend and individuals' attitudes

toward the advertisements influence brand equity dimensions.Simi-

larly, the study focuses on two kinds of sales promotions, monetary and

non-monetary. Based on the literature, this research also hypothesizes

relationships among brand equity dimensions.

3.1.Advertising

Advertising is one of the most visible marketing activities.

Generally,researchers posit that advertising is successful in building

consumer-based brand equity,having a sustaining and accumulative

116 I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

shed more light on two particular drivers of brand equity: advertising

and sales promotions. In particular, the study focuses on advertising

spend and individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements.Simi-

larly, the research investigates the effects oftwo kinds of sales

promotions, monetary and non-monetary promotions.Second,to

explore the relationships among brand equity dimensions.

Building on the framework proposed by Yoo et al. (2000), the current

work goes beyond research on sources of brand equity in several ways.

First,most brand equity studies have simply focused on the influence

that advertising spend and frequency of monetary promotions have

on brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000; Villarejo and Sánchez, 2005; Bravo

et al.,2007; Valette-Florence et al.,2011).By contrast,this study also

analyzes individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements and non-

monetary promotions.Despite several scholars recognizing that other

advertising characteristicsbeyond just advertising spend,such as

individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements,play an important

role in growing brand equity (Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Keller and

Lehmann, 2003; 2006; Bravo et al., 2007; Sriram et al., 2007), research

on brand equity has traditionally ignored these attitudes.Similarly,

recent literature on sales promotions (e.g., Chandon et al., 2000) stresses

the need to differentiate between two types of promotions,monetary

and non-monetary promotions. Surprisingly, academic research into the

effects of non-monetary promotions on brand equity is scarce. Second,

this article analyzes the causal order among brand equity dimensions.

Several studies suggest a hierarchy in terms of the importance of brand

equity dimensions and potential causal order (Agarwal and Rao, 1996;

Maio Mackay, 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and Lehmann, 2003;

2006).However,few studies have empirically examined how brand

equity dimensions inter-relate. Analyzing all these aspects, this research

advances knowledge by providing more insight about the evolving

theory of brand equity.

This paper opens with a brief,general discussion of brand equity

and marketing mix elements followed by the hypotheses.Then,the

fourth section explains the methodology to testthe model. Next

section presents the results of the study. Finally, the paper concludes

by outlining the conclusions, implications and limitations of the

research.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1.Brand equity

Brand equity is a key issue in marketing.Despite receiving con-

siderable attention,no consensus exists aboutwhich are the best

measures to capture this complex and multi-faceted construct (Maio

Mackay, 2001; Raggio and Leone,2007). Part of the reason is the

different perspectives adopted to define and measure this concept

(Christodoulides and de Chernatony, 2010). The financial perspective

stresses the value of a brand to the firm (Simon and Sullivan,1993;

Feldwick, 1996). On the other hand, the consumer perspective focuses

the conceptualization and measurement of brand equity on individual

consumers (Leone et al.,2006).

Adopting the latter perspective,and from a cognitive psychology

approach,brand equity denotes the added value endowed by the

brand to the product (Farquhar,1989).Aaker (1991,p. 15) provides

one of the most accepted and comprehensive definitions ofbrand

equity: “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and

symbol that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or

service to a firm and/or to thatfirm's customers”.Keller (1993,p. 2)

proposes a similar definition: “the differential effect of brand knowledge

on consumer response to the marketing of the brand”.

Consumer-based brand equity measuresassessthe awareness,

attitudes,associations,attachmentsand loyalties consumershave

toward a brand (Keller and Lehmann,2006). These measures offer

considerable advantages such as the assessment of sources of brand

equity and its consequences, plus a diagnostic capability (Ailawadi et al.,

2003; Gupta and Zeithaml, 2006). In this sense, these measures act as

early evaluation signals about future performance (Srinivasan et al.,

2010).From this perspective,the two main frameworks that concep-

tualize brand equity are those ofAaker (1991) and Keller (1993).

According to Aaker (1991), brand equity is a multidimensional concept

whose first four core brand equity dimensions are brand awareness,

perceived quality,brand associations and brand loyalty.Brand equity

research omits the fifth of Aaker's dimensions, other proprietary brand

assets,since this component is not pertinent to consumers.Keller's

(1993) conceptualization focuses on brand knowledge and involves two

components: brand awareness and brand image.

Drawing on these theoretical proposals,a large number of studies

conceptualize and measure brand equity using the dimensions of brand

awareness, perceived quality, brand associations and brand loyalty (e.g.,

Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Yoo et al.,2000; Yoo and Donthu,2001;

Washburn and Plank, 2002; Ashill and Sinha, 2004; Pappu et al., 2005;

2006; Konecnik and Gartner,2007; Tong and Hawley,2009; Lee and

Back, 2010).

Following these two approaches,this research uses a consumer-

based brand equity measure that consists of four dimensions: brand

awareness,perceived quality, brand associations, and brand loyalty.

2.2.Marketing mix elements

Marketing mix elements influence consumers'equity perceptions

toward brands (Pappu and Quester, 2008). These variables are impor-

tant not only because they can greatly affect brand equity but also

because they are under companies' control, enabling marketers to grow

brand equity through their marketing activities (Keller,1993; Berry,

2000; Yoo et al., 2000; Ailawadi et al., 2003; Herrmann et al., 2007).

Within the discipline of marketing dynamics, numerous studies use

financial and product–market measures of brand equity to analyze the

short- and long-term effects of marketing actions and polices, such as

advertising and price promotions (Leeflang et al.,2009; Ataman et al.,

2010; Srinivasan et al., 2010).

From the consumer-based brand equity perspective, which

this research follows,Yoo et al. (2000) find that high advertising

spend,high price,high distribution intensity and distribution through

retailers with good store image would help build brand equity.By

contrast, frequent price promotions would harm brand equity. Villarejo

and Sánchez (2005) also focus their study on advertising spend and

price promotions,while Bravo et al.(2007) add to these variables the

effect of the price.

This study focuses on the role of two specific marketing com-

munications tools: advertising and sales promotions. These two

marketing elements account for at least 25% of UK marketing budgets

(Chartered Institute of Marketing,2009). Despite their importance,

the influence of these variables on brand equity still remains unclear

(Netemeyer et al.,2004; Chu and Keh, 2006). This research responds

to this gap by exploring their effects on consumer-based brand equity.

3. Research hypotheses

Fig. 1 shows the conceptualframework underlying this research.

This study addresses how advertising spend and individuals' attitudes

toward the advertisements influence brand equity dimensions.Simi-

larly, the study focuses on two kinds of sales promotions, monetary and

non-monetary. Based on the literature, this research also hypothesizes

relationships among brand equity dimensions.

3.1.Advertising

Advertising is one of the most visible marketing activities.

Generally,researchers posit that advertising is successful in building

consumer-based brand equity,having a sustaining and accumulative

116 I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

effect on this asset (Wang et al.,2009).However,advertising effects

depend on both the amount invested and the types of messages

communicated (Martínez et al.,2009).

Several authors have investigated how actual and perceived

advertising spend influences brand equity and its dimensions (Simon

and Sullivan, 1993; Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995; Yoo et al., 2000; Villarejo

and Sánchez,2005; Bravo et al.,2007).Both approaches find positive

relationships between advertising spend and brand equity. Researchers

conclude that perceptions ofhigh advertising spend contribute to

developing a more positive perception of brand quality,higher brand

awareness and stronger brand associations (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000).

Advertising expenditure can influence brand equity dimensions in

several ways. When judging the product's quality,consumers use

different intrinsic and extrinsic cues (Rao and Monroe, 1989). Perceived

advertising spend is one such extrinsic quality cue (Milgrom and

Roberts,1986; Kirmani and Rao,2000).Using laboratory experiments

several studies report positive relations between perceived advertising

spend and perceived quality (Kirmani and Wright, 1989; Kirmani, 1990;

1997; Moorthy and Hawkins, 2005). This result is also evident through

work in shopping environments (Moorthy and Zhao, 2000). Thus, con-

sumers generally perceive highly advertised brands as higher quality

brands (Yoo et al., 2000; Bravo et al., 2007).

Similarly,large advertising investments can favor correctbrand

recall and recognition. Brand advertising spend can increase the scope

and frequency of brand appearance, and as a consequence, the level of

brand awareness (Chu and Keh, 2006; Keller, 2007). As such, the higher

advertising spend, the higher awareness levels are likely to be (Yoo et al.,

2000; Villarejo and Sánchez, 2005; Bravo et al., 2007).

Finally, advertising can also create favorable,strong and unique

brand associations (Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995; Keller, 2007). Like brand

awareness,brand associations arise from consumer-brand contact.As

such, advertising can contribute to brand associations through its ability

to create,modify or reinforce associations with each new contact.

Hence,the higher a brand's advertising spend,the stronger and more

numerous will be the associations in the consumer's mind (Bravo et al.,

2007). All these arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

H1. Consumers'perceptions ofa brand's advertising spend have a

positive influence on: a) perceived quality; b) brand awareness and

c) brand associations.

Researchers recognize that individuals'attitudes toward adver-

tisements can also play an important role influencing brand equity

(Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Keller and Lehmann,2003; 2006; Bravo

et al., 2007; Sriram et al., 2007). However, these issues have received

little attention in brand equity research.

Advertising is a powerful way of communicating a brand's func-

tional and emotionalvalues (de Chernatony,2010). In general,the

effectiveness of this communication tool depends on its content (i.e.,

the message), the execution or how the ad conveys the message, and

the frequency with which a consumer sees the advertisement (Batra

et al.,1996; Kotler,2000).As mentioned earlier,advertising creates

brand awareness,links strong,favorable,and unique associations to

the brand in consumers'memory,and elicits positive brand judg-

ments and feelings (Keller,2007).However to achieve these results,

the advertising needs a suitable design and execution.In particular,

one of the main concerns devising an advertising strategy relates to

the creative strategy (Kapferer, 2004; Keller,2007).

Through an originaland innovative advertising strategy,organi-

zations may be more likely to capture consumers'attention.In turn,

consumers'attention can lead to higher brand awareness, higher per-

ceived quality and contribute to forming strong, favorable and unique

associations (Lavidge and Steiner,1961; Aaker, 1991; Kirmani and

Zeithaml, 1993; Villarejo, 2002). In short, besides increasing consumers

familiarity with a brand, advertising can shape consumers' perceptions

of quality and other brand associations (Moorthy and Hawkins, 2005).

The following hypothesis synthesizes the above arguments:

H2. Individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements undertaken for

a brand have a positive influence on: a) perceived quality; b) brand

awareness and c) brand associations.

3.2.Sales promotions

Sales promotions are also a key marketing tool in communication

programs that influence brand equity (Valette-Florence et al.,2011).

However,different types of promotionaltools (e.g.,monetary and

non-monetary promotions) may have different effects on sales,

profitability or brand equity (Srinivasan and Anderson, 1998).

Most previous researches on sales promotions focus on monetary

promotions,such as price discounts and coupons.Although some dis-

cussion about the effect of this tool on brand equity still exists

(Palazón-Vidal and Delgado-Ballester,2005; Joseph and Sivakumaran,

2008), the empirical evidence suggests that monetary promotions have

a negative impact on brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000).

Focusing on the direct effects on brand equity dimensions, monetary

promotions are likely to have a negative influence on perceived quality

and brand associations. The reduction in the internal reference price is

one of the main reasons why monetary promotions have a negative

influence on perceived quality. Consumers use price as an extrinsic cue

to infer product quality (Milgrom and Roberts, 1986; Rao and Monroe,

1989; Dodds et al., 1991; Agarwal and Teas, 2002). As such, the influen

Brand

awareness

Perceived

quality

Brand

associations

Brand

loyalty

Advertising

spend

Non-monetary

promotions

Monetary

promotions

Attitudes toward

advertisements

H5

H6

H8

H7

H4a

H4b

H3a

H3b

H1a

H1bH1c

H2a

H2b

H2c

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

117I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

depend on both the amount invested and the types of messages

communicated (Martínez et al.,2009).

Several authors have investigated how actual and perceived

advertising spend influences brand equity and its dimensions (Simon

and Sullivan, 1993; Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995; Yoo et al., 2000; Villarejo

and Sánchez,2005; Bravo et al.,2007).Both approaches find positive

relationships between advertising spend and brand equity. Researchers

conclude that perceptions ofhigh advertising spend contribute to

developing a more positive perception of brand quality,higher brand

awareness and stronger brand associations (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000).

Advertising expenditure can influence brand equity dimensions in

several ways. When judging the product's quality,consumers use

different intrinsic and extrinsic cues (Rao and Monroe, 1989). Perceived

advertising spend is one such extrinsic quality cue (Milgrom and

Roberts,1986; Kirmani and Rao,2000).Using laboratory experiments

several studies report positive relations between perceived advertising

spend and perceived quality (Kirmani and Wright, 1989; Kirmani, 1990;

1997; Moorthy and Hawkins, 2005). This result is also evident through

work in shopping environments (Moorthy and Zhao, 2000). Thus, con-

sumers generally perceive highly advertised brands as higher quality

brands (Yoo et al., 2000; Bravo et al., 2007).

Similarly,large advertising investments can favor correctbrand

recall and recognition. Brand advertising spend can increase the scope

and frequency of brand appearance, and as a consequence, the level of

brand awareness (Chu and Keh, 2006; Keller, 2007). As such, the higher

advertising spend, the higher awareness levels are likely to be (Yoo et al.,

2000; Villarejo and Sánchez, 2005; Bravo et al., 2007).

Finally, advertising can also create favorable,strong and unique

brand associations (Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995; Keller, 2007). Like brand

awareness,brand associations arise from consumer-brand contact.As

such, advertising can contribute to brand associations through its ability

to create,modify or reinforce associations with each new contact.

Hence,the higher a brand's advertising spend,the stronger and more

numerous will be the associations in the consumer's mind (Bravo et al.,

2007). All these arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

H1. Consumers'perceptions ofa brand's advertising spend have a

positive influence on: a) perceived quality; b) brand awareness and

c) brand associations.

Researchers recognize that individuals'attitudes toward adver-

tisements can also play an important role influencing brand equity

(Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Keller and Lehmann,2003; 2006; Bravo

et al., 2007; Sriram et al., 2007). However, these issues have received

little attention in brand equity research.

Advertising is a powerful way of communicating a brand's func-

tional and emotionalvalues (de Chernatony,2010). In general,the

effectiveness of this communication tool depends on its content (i.e.,

the message), the execution or how the ad conveys the message, and

the frequency with which a consumer sees the advertisement (Batra

et al.,1996; Kotler,2000).As mentioned earlier,advertising creates

brand awareness,links strong,favorable,and unique associations to

the brand in consumers'memory,and elicits positive brand judg-

ments and feelings (Keller,2007).However to achieve these results,

the advertising needs a suitable design and execution.In particular,

one of the main concerns devising an advertising strategy relates to

the creative strategy (Kapferer, 2004; Keller,2007).

Through an originaland innovative advertising strategy,organi-

zations may be more likely to capture consumers'attention.In turn,

consumers'attention can lead to higher brand awareness, higher per-

ceived quality and contribute to forming strong, favorable and unique

associations (Lavidge and Steiner,1961; Aaker, 1991; Kirmani and

Zeithaml, 1993; Villarejo, 2002). In short, besides increasing consumers

familiarity with a brand, advertising can shape consumers' perceptions

of quality and other brand associations (Moorthy and Hawkins, 2005).

The following hypothesis synthesizes the above arguments:

H2. Individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements undertaken for

a brand have a positive influence on: a) perceived quality; b) brand

awareness and c) brand associations.

3.2.Sales promotions

Sales promotions are also a key marketing tool in communication

programs that influence brand equity (Valette-Florence et al.,2011).

However,different types of promotionaltools (e.g.,monetary and

non-monetary promotions) may have different effects on sales,

profitability or brand equity (Srinivasan and Anderson, 1998).

Most previous researches on sales promotions focus on monetary

promotions,such as price discounts and coupons.Although some dis-

cussion about the effect of this tool on brand equity still exists

(Palazón-Vidal and Delgado-Ballester,2005; Joseph and Sivakumaran,

2008), the empirical evidence suggests that monetary promotions have

a negative impact on brand equity (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000).

Focusing on the direct effects on brand equity dimensions, monetary

promotions are likely to have a negative influence on perceived quality

and brand associations. The reduction in the internal reference price is

one of the main reasons why monetary promotions have a negative

influence on perceived quality. Consumers use price as an extrinsic cue

to infer product quality (Milgrom and Roberts, 1986; Rao and Monroe,

1989; Dodds et al., 1991; Agarwal and Teas, 2002). As such, the influen

Brand

awareness

Perceived

quality

Brand

associations

Brand

loyalty

Advertising

spend

Non-monetary

promotions

Monetary

promotions

Attitudes toward

advertisements

H5

H6

H8

H7

H4a

H4b

H3a

H3b

H1a

H1bH1c

H2a

H2b

H2c

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

117I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of price discounting on consumers'reference price can lead to un-

favorable quality evaluations (Mela et al., 1998; Raghubir and Corfman,

1999; Jørgensen et al., 2003; DelVecchio et al., 2006).

Similarly, monetary promotions can erode brand associations.

Martínez et al.(2007) and Montaner and Pina (2008) reported that

monetary promotions have a negative impact on brand image. In addi-

tion, monetary promotion campaigns are too short to establish long-

term brand associations and can create uncertainty about brand quality

(Winer, 1986), which results in more negative brand perceptions.

In short, the frequent use of price promotions has a negative

impact on perceived quality and brand association dimensions

because this toolleads consumers to think primarily about price,

and not about the brand (Yoo et al., 2000). Hence, the third hy-

pothesis states:

H3. Consumers' perceptions of a brand's monetary promotions have a

negative influence on: a) perceived quality and b) brand associations.

Non-monetary promotions, such as free gifts, free samples, sweep-

stakes and contests,are becoming increasingly important in promo-

tional strategies (Palazón and Delgado-Ballester,2009).Surprisingly,

academic research into the effects ofnon-monetary promotions on

brand equity is scarce.

Recent studies show that non-monetary promotions may help

reinforce brand equity (Palazón-Vidaland Delgado-Ballester,2005;

Montaner and Pina, 2008). Unlike monetary promotions, non-monetary

promotions do not influence consumers'internal reference prices

(Campbelland Diamond,1990), and consequently are less likely to

create a negative influence on perceived quality.

Likewise, non-monetary promotions can help differentiate brands,

communicating distinctive brand attributes and contribute to the

improved brand equity (Papatla and Krishnamurthi, 1996; Mela et al.,

1998; Chu and Keh, 2006). While monetary promotions primarily

relate to utilitarian benefits, non-monetary promotions relate to

hedonic benefits (Chandon et al., 2000). These benefits,such as

entertainment and exploration,are similar to experiential emotions,

pleasure and self-esteem.Non-monetary promotions can therefore

evoke more associations related to brand personality, enjoyable

experiences,feelings and emotions. Furthermore,they link more

favorable and positive brand associations to the brand (Palazón-Vidal

and Delgado-Ballester,2005).

Non-monetary promotion strategies can enhance brand equity

(Montaner and Pina,2008),positively influencing perceived quality

and brand associations,as the following hypothesis postulates:

H4. Consumers' perceptions of a brand's non-monetary promo-

tions have a positive influence on: a) perceived quality and b) brand

associations.

3.3.Relationships among brand equity dimensions

Brand equity dimensions inter-relate.While some studies pro-

pose associative relationships among brand equity dimensions (e.g.,

Yoo et al.,2000; Pappu et al.,2005; 2006; Tong and Hawley,2009),

few researchers posit causalrelations among them (e.g.,Ashill and

Sinha, 2004; Bravo et al.,2007).

This study builds on the traditional hierarchy of effects model

to propose hypotheses about the relationships among brand

equity dimensions. This model, also known as the standard learning

hierarchy, follows the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen,

1975; Ajzen and Fishbein,1980). This theory posits that attitudes

and subjective norms influence intentions, which in turn affect

behavior. Approaching a product decision as a problem-solving pro-

cess, this hierarchy model suggests thatconsumers form beliefs

about a product by seeking information about relevant attributes.

Consumers then evaluate these beliefs and develop feelings about the

product resulting in buying or rejecting the brand (Solomon et al.,

2006). The traditional hierarchy of effects model assumes that

consumers are highly involved in making their decision. According to

this model, consumers are motivated to seek out information,

evaluate alternatives and make a considered decision (Solomon et

al., 2006).

Although some researchers challenge this framework and

propose alternative hierarchy models (Krugman,1965; 1966; Ray

et al., 1973; Barry et al., 1987; Solomon et al., 2006), most researchers

posit that this theory is a useful framework for studying the causal

order among the dimensions of brand equity from the perspective of

the consumer (Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Agarwal and Rao,1996;

Maio Mackay, 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and Lehmann,

2003; 2006; Tolba and Hassan, 2009).

This framework depicts the evolution of brand equity as a consumer

learning process: consumers' awareness of the brand leads to attitudes

(e.g.,perceived quality and brand associations),which in turn will

influence attitudinal brand loyalty (Lavidge and Steiner, 1961; Gordon

et al., 1993; Konecnik and Gartner, 2007).

The process of building brand equity begins with increasing brand

awareness.Consumers must first be aware of a brand to later have a

set of brand associations (Aaker,1991).Brand awareness affects the

formation and the strength of brand associations, including perceived

quality (Keller, 1993; Pitta and Katsanis, 1995; Aaker, 1996; Na et al.,

1999; Keller and Lehmann, 2003; Konecnik and Gartner, 2007). Thus,

brand awareness is important as an antecedent to brand associations

and perceived quality (Pitta and Katsanis, 1995; Keller and Lehmann,

2003).

When consumers acquire a more positive perception of a brand,

loyalty results (Oliver, 1999). As such, brand associations and perceived

quality are the previous step leading to brand loyalty (Keller and

Lehmann,2003).Thus,high levels ofperceived quality and positive

associations can enhance brand loyalty (Keller, 1993; Chaudhuri, 1999;

Keller and Lehmann, 2003; Pappu et al.,2005). The following hypoth-

eses summarize these arguments:

H5. Brand awareness has a positive influence on perceived quality.

H6. Brand awareness has a positive influence on brand associations.

H7. Perceived quality has a positive influence on brand loyalty.

H8. Brand associations have a positive influence on brand loyalty.

4. Methodology

4.1.Sample selection and data collection

The data to test the hypotheses came from a consumer survey in

the United Kingdom.This study uses a sample of consumers unlike

other studies that examine the influence of marketing communica-

tion elements on brand equity on student samples (e.g.,Yoo et al.,

2000).

Following previous works in this area (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000;

Netemeyer et al.,2004), two criteria guide the selection of product

categories and brands. The first criterion is to select product categories

and brands that are widely available and well-known by UK con-

sumers.This enables consumers to provide more valid and reliable

responses and assures the reliability of the scales (Parameswaran and

Yaprak,1987). The second criterion is to choose product categories

and brands that reflect a broad set of consumer products and provide

some generalizability.

The use of rankings and secondary research to select product

categories and brands is common in brand equity research (Cobb-

Walgren et al.,1995; Krishnan, 1996; Netemeyer et al., 2004). Thus,

this study used the Best Global Brands ranking by Interbrand.

118 I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

favorable quality evaluations (Mela et al., 1998; Raghubir and Corfman,

1999; Jørgensen et al., 2003; DelVecchio et al., 2006).

Similarly, monetary promotions can erode brand associations.

Martínez et al.(2007) and Montaner and Pina (2008) reported that

monetary promotions have a negative impact on brand image. In addi-

tion, monetary promotion campaigns are too short to establish long-

term brand associations and can create uncertainty about brand quality

(Winer, 1986), which results in more negative brand perceptions.

In short, the frequent use of price promotions has a negative

impact on perceived quality and brand association dimensions

because this toolleads consumers to think primarily about price,

and not about the brand (Yoo et al., 2000). Hence, the third hy-

pothesis states:

H3. Consumers' perceptions of a brand's monetary promotions have a

negative influence on: a) perceived quality and b) brand associations.

Non-monetary promotions, such as free gifts, free samples, sweep-

stakes and contests,are becoming increasingly important in promo-

tional strategies (Palazón and Delgado-Ballester,2009).Surprisingly,

academic research into the effects ofnon-monetary promotions on

brand equity is scarce.

Recent studies show that non-monetary promotions may help

reinforce brand equity (Palazón-Vidaland Delgado-Ballester,2005;

Montaner and Pina, 2008). Unlike monetary promotions, non-monetary

promotions do not influence consumers'internal reference prices

(Campbelland Diamond,1990), and consequently are less likely to

create a negative influence on perceived quality.

Likewise, non-monetary promotions can help differentiate brands,

communicating distinctive brand attributes and contribute to the

improved brand equity (Papatla and Krishnamurthi, 1996; Mela et al.,

1998; Chu and Keh, 2006). While monetary promotions primarily

relate to utilitarian benefits, non-monetary promotions relate to

hedonic benefits (Chandon et al., 2000). These benefits,such as

entertainment and exploration,are similar to experiential emotions,

pleasure and self-esteem.Non-monetary promotions can therefore

evoke more associations related to brand personality, enjoyable

experiences,feelings and emotions. Furthermore,they link more

favorable and positive brand associations to the brand (Palazón-Vidal

and Delgado-Ballester,2005).

Non-monetary promotion strategies can enhance brand equity

(Montaner and Pina,2008),positively influencing perceived quality

and brand associations,as the following hypothesis postulates:

H4. Consumers' perceptions of a brand's non-monetary promo-

tions have a positive influence on: a) perceived quality and b) brand

associations.

3.3.Relationships among brand equity dimensions

Brand equity dimensions inter-relate.While some studies pro-

pose associative relationships among brand equity dimensions (e.g.,

Yoo et al.,2000; Pappu et al.,2005; 2006; Tong and Hawley,2009),

few researchers posit causalrelations among them (e.g.,Ashill and

Sinha, 2004; Bravo et al.,2007).

This study builds on the traditional hierarchy of effects model

to propose hypotheses about the relationships among brand

equity dimensions. This model, also known as the standard learning

hierarchy, follows the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen,

1975; Ajzen and Fishbein,1980). This theory posits that attitudes

and subjective norms influence intentions, which in turn affect

behavior. Approaching a product decision as a problem-solving pro-

cess, this hierarchy model suggests thatconsumers form beliefs

about a product by seeking information about relevant attributes.

Consumers then evaluate these beliefs and develop feelings about the

product resulting in buying or rejecting the brand (Solomon et al.,

2006). The traditional hierarchy of effects model assumes that

consumers are highly involved in making their decision. According to

this model, consumers are motivated to seek out information,

evaluate alternatives and make a considered decision (Solomon et

al., 2006).

Although some researchers challenge this framework and

propose alternative hierarchy models (Krugman,1965; 1966; Ray

et al., 1973; Barry et al., 1987; Solomon et al., 2006), most researchers

posit that this theory is a useful framework for studying the causal

order among the dimensions of brand equity from the perspective of

the consumer (Cobb-Walgren et al.,1995; Agarwal and Rao,1996;

Maio Mackay, 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Keller and Lehmann,

2003; 2006; Tolba and Hassan, 2009).

This framework depicts the evolution of brand equity as a consumer

learning process: consumers' awareness of the brand leads to attitudes

(e.g.,perceived quality and brand associations),which in turn will

influence attitudinal brand loyalty (Lavidge and Steiner, 1961; Gordon

et al., 1993; Konecnik and Gartner, 2007).

The process of building brand equity begins with increasing brand

awareness.Consumers must first be aware of a brand to later have a

set of brand associations (Aaker,1991).Brand awareness affects the

formation and the strength of brand associations, including perceived

quality (Keller, 1993; Pitta and Katsanis, 1995; Aaker, 1996; Na et al.,

1999; Keller and Lehmann, 2003; Konecnik and Gartner, 2007). Thus,

brand awareness is important as an antecedent to brand associations

and perceived quality (Pitta and Katsanis, 1995; Keller and Lehmann,

2003).

When consumers acquire a more positive perception of a brand,

loyalty results (Oliver, 1999). As such, brand associations and perceived

quality are the previous step leading to brand loyalty (Keller and

Lehmann,2003).Thus,high levels ofperceived quality and positive

associations can enhance brand loyalty (Keller, 1993; Chaudhuri, 1999;

Keller and Lehmann, 2003; Pappu et al.,2005). The following hypoth-

eses summarize these arguments:

H5. Brand awareness has a positive influence on perceived quality.

H6. Brand awareness has a positive influence on brand associations.

H7. Perceived quality has a positive influence on brand loyalty.

H8. Brand associations have a positive influence on brand loyalty.

4. Methodology

4.1.Sample selection and data collection

The data to test the hypotheses came from a consumer survey in

the United Kingdom.This study uses a sample of consumers unlike

other studies that examine the influence of marketing communica-

tion elements on brand equity on student samples (e.g.,Yoo et al.,

2000).

Following previous works in this area (e.g., Yoo et al., 2000;

Netemeyer et al.,2004), two criteria guide the selection of product

categories and brands. The first criterion is to select product categories

and brands that are widely available and well-known by UK con-

sumers.This enables consumers to provide more valid and reliable

responses and assures the reliability of the scales (Parameswaran and

Yaprak,1987). The second criterion is to choose product categories

and brands that reflect a broad set of consumer products and provide

some generalizability.

The use of rankings and secondary research to select product

categories and brands is common in brand equity research (Cobb-

Walgren et al.,1995; Krishnan, 1996; Netemeyer et al., 2004). Thus,

this study used the Best Global Brands ranking by Interbrand.

118 I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Following the criteria noted above,the empirical research is based

on three product categories,within each of which there are two

mature brands, selected from the Interbrand ranking (i.e., six brands

in total were chosen).All the brands selected are valuable but have

different positions in the ranking. They also represent different

marketing characteristics (e.g., price, market share, marketing

strategies,etc.), which enhance the generalizability ofthe results

(Yoo et al., 2000; Netemeyer et al., 2004). The brands are Adidas and

Nike for sportswear,Sony and Panasonic for consumer electronics,

and BMW and Volkswagen for cars.All brands are familiar and well

known to UK consumers, which is an important criterion to

understand brand equity (Krishnan,1996). In addition, the variety

of categories selected enhances the generalizability of the findings.

Previous studies recognize these three categories as high involve-

ment product categories (e.g., Chen, 2007; Ko et al., 2007).

The empirical study used six questionnaires,one for each brand.

Each respondent only completed one version of the questionnaire and

evaluated only one brand.To be eligible for the study,respondents

needed to be aware of the focal brand on their questionnaire.

Collection of data took place at severallocations in the city of

Birmingham using quota sampling (by age and sex).Field workers

collected the data during different times of the day and on different

days.Of the 307 received questionnaires,302 valid questionnaires

were completed and the data from these 302 were analyzed.The

profile of the sample represented the population ofBirmingham,

which is akin to the general national population of the United

Kingdom. As such, 24.3% of respondents are 15 to 24 years old; 37.5%

are 25 to 39 years old and the remainder are 40 to 69 years old. Males

represent 50.9% of respondents.

4.2.Measurement

A review of previous studies provided the basis for the selection of

the measures for the marketing communication tools and brand

equity dimensions.The respondents assessed allitems on seven-

point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree).

Given that consumers have little knowledge ofactualmarketing

efforts, measures of marketing communications rely on perceived mar-

keting efforts (Yoo et al., 2000). These measures also link more directly

with consumer psychology (Yoo et al.,2000; Valette-Florence et al.,

2011). This study measures perceived advertising spend by adopting the

scale proposed by Yoo et al.(2000).To measure individuals'attitudes

toward the advertisements,this research proposes a three-item scale.

The brand equity literature recognizes that the degree to which con-

sumers perceive advertising as creative,original and different from

other competing brands are important success factors for advertising

(Kapferer, 2004; Keller, 2007). Interviews with experts also supported

this view.Previous scales,however,did not include these three char-

acteristics (e.g., LaTour et al., 1990; Henthorne et al., 1993). Therefore,

the three-item scale used to measure individuals' attitudes toward the

advertisements takes into accountinsights from the brand equity

literature and experts' opinion. To measure the perceived monetary and

non-monetary promotion intensities the study employs and adapts the

three-item scale of Yoo et al.(2000).Specifically,price discounts and

gifts were used as they are increasingly importantin promotional

strategies (Raghubir, 2005; Palazón and Delgado-Ballester, 2009).

The measurement ofbrand equity is consistent with the multi-

dimensionalconceptualization proposed within the consumer-based

perspective.Drawing from the literature (Lassar et al.,1995; Aaker,

1996; Yoo et al., 2000; Netemeyer et al., 2004; Pappu et al., 2005; 2006),

this research usesfive items to measure brand awareness, four items to

assess perceived quality,nine items to gauge brand associations and

three items to measure brand loyalty.

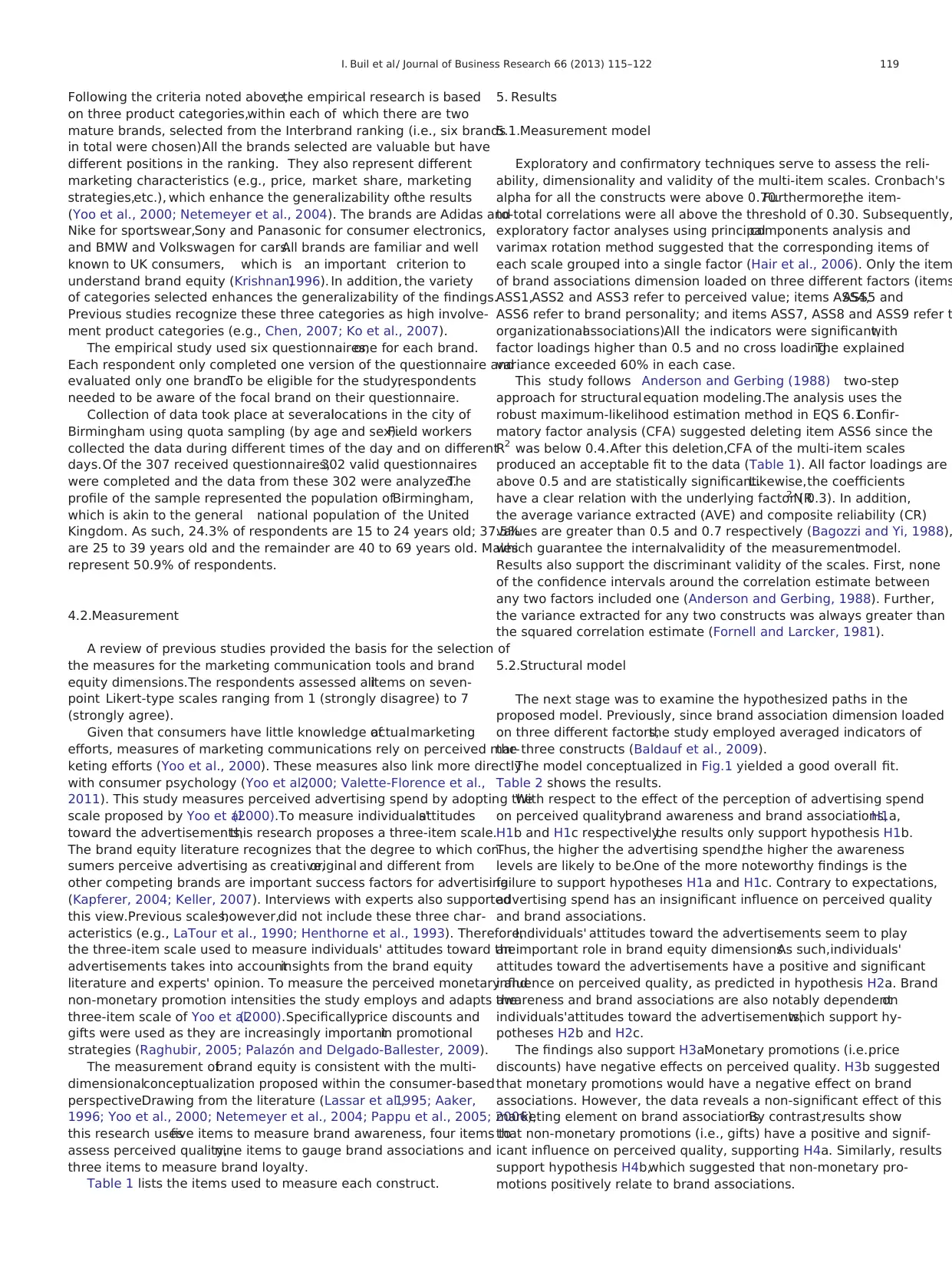

Table 1 lists the items used to measure each construct.

5. Results

5.1.Measurement model

Exploratory and confirmatory techniques serve to assess the reli-

ability, dimensionality and validity of the multi-item scales. Cronbach's

alpha for all the constructs were above 0.70.Furthermore,the item-

to-total correlations were all above the threshold of 0.30. Subsequently,

exploratory factor analyses using principalcomponents analysis and

varimax rotation method suggested that the corresponding items of

each scale grouped into a single factor (Hair et al., 2006). Only the item

of brand associations dimension loaded on three different factors (items

ASS1,ASS2 and ASS3 refer to perceived value; items ASS4,ASS5 and

ASS6 refer to brand personality; and items ASS7, ASS8 and ASS9 refer t

organizationalassociations).All the indicators were significant,with

factor loadings higher than 0.5 and no cross loading.The explained

variance exceeded 60% in each case.

This study follows Anderson and Gerbing (1988) two-step

approach for structural equation modeling.The analysis uses the

robust maximum-likelihood estimation method in EQS 6.1.Confir-

matory factor analysis (CFA) suggested deleting item ASS6 since the

R2 was below 0.4.After this deletion,CFA of the multi-item scales

produced an acceptable fit to the data (Table 1). All factor loadings are

above 0.5 and are statistically significant.Likewise,the coefficients

have a clear relation with the underlying factor (R2N 0.3). In addition,

the average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR)

values are greater than 0.5 and 0.7 respectively (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988),

which guarantee the internalvalidity of the measurementmodel.

Results also support the discriminant validity of the scales. First, none

of the confidence intervals around the correlation estimate between

any two factors included one (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Further,

the variance extracted for any two constructs was always greater than

the squared correlation estimate (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

5.2.Structural model

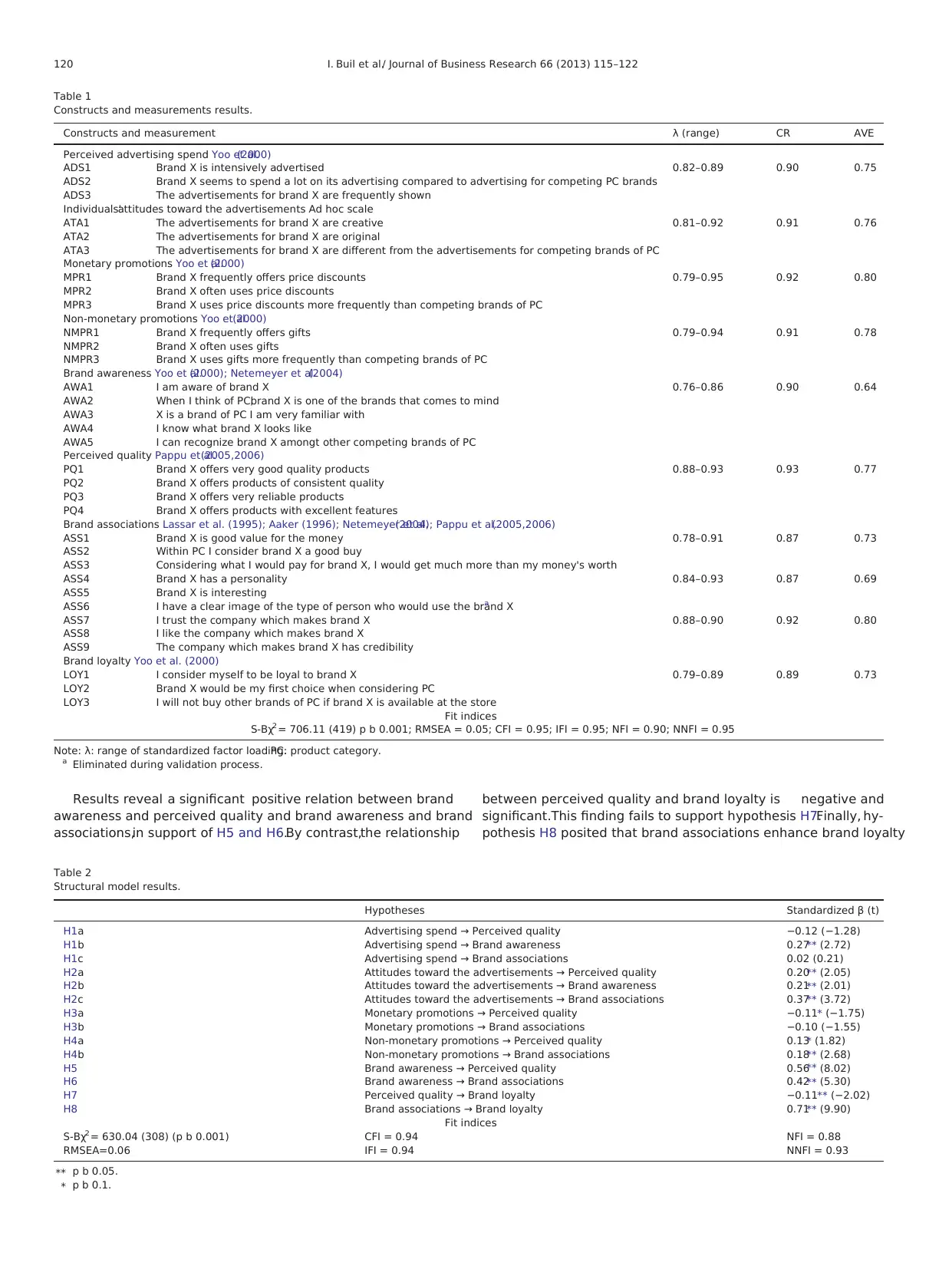

The next stage was to examine the hypothesized paths in the

proposed model. Previously, since brand association dimension loaded

on three different factors,the study employed averaged indicators of

the three constructs (Baldauf et al., 2009).

The model conceptualized in Fig.1 yielded a good overall fit.

Table 2 shows the results.

With respect to the effect of the perception of advertising spend

on perceived quality,brand awareness and brand associations,H1a,

H1b and H1c respectively,the results only support hypothesis H1b.

Thus, the higher the advertising spend,the higher the awareness

levels are likely to be.One of the more noteworthy findings is the

failure to support hypotheses H1a and H1c. Contrary to expectations,

advertising spend has an insignificant influence on perceived quality

and brand associations.

Individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements seem to play

an important role in brand equity dimensions.As such,individuals'

attitudes toward the advertisements have a positive and significant

influence on perceived quality, as predicted in hypothesis H2a. Brand

awareness and brand associations are also notably dependenton

individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements,which support hy-

potheses H2b and H2c.

The findings also support H3a.Monetary promotions (i.e.,price

discounts) have negative effects on perceived quality. H3b suggested

that monetary promotions would have a negative effect on brand

associations. However, the data reveals a non-significant effect of this

marketing element on brand associations.By contrast,results show

that non-monetary promotions (i.e., gifts) have a positive and signif-

icant influence on perceived quality, supporting H4a. Similarly, results

support hypothesis H4b,which suggested that non-monetary pro-

motions positively relate to brand associations.

119I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

on three product categories,within each of which there are two

mature brands, selected from the Interbrand ranking (i.e., six brands

in total were chosen).All the brands selected are valuable but have

different positions in the ranking. They also represent different

marketing characteristics (e.g., price, market share, marketing

strategies,etc.), which enhance the generalizability ofthe results

(Yoo et al., 2000; Netemeyer et al., 2004). The brands are Adidas and

Nike for sportswear,Sony and Panasonic for consumer electronics,

and BMW and Volkswagen for cars.All brands are familiar and well

known to UK consumers, which is an important criterion to

understand brand equity (Krishnan,1996). In addition, the variety

of categories selected enhances the generalizability of the findings.

Previous studies recognize these three categories as high involve-

ment product categories (e.g., Chen, 2007; Ko et al., 2007).

The empirical study used six questionnaires,one for each brand.

Each respondent only completed one version of the questionnaire and

evaluated only one brand.To be eligible for the study,respondents

needed to be aware of the focal brand on their questionnaire.

Collection of data took place at severallocations in the city of

Birmingham using quota sampling (by age and sex).Field workers

collected the data during different times of the day and on different

days.Of the 307 received questionnaires,302 valid questionnaires

were completed and the data from these 302 were analyzed.The

profile of the sample represented the population ofBirmingham,

which is akin to the general national population of the United

Kingdom. As such, 24.3% of respondents are 15 to 24 years old; 37.5%

are 25 to 39 years old and the remainder are 40 to 69 years old. Males

represent 50.9% of respondents.

4.2.Measurement

A review of previous studies provided the basis for the selection of

the measures for the marketing communication tools and brand

equity dimensions.The respondents assessed allitems on seven-

point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree).

Given that consumers have little knowledge ofactualmarketing

efforts, measures of marketing communications rely on perceived mar-

keting efforts (Yoo et al., 2000). These measures also link more directly

with consumer psychology (Yoo et al.,2000; Valette-Florence et al.,

2011). This study measures perceived advertising spend by adopting the

scale proposed by Yoo et al.(2000).To measure individuals'attitudes

toward the advertisements,this research proposes a three-item scale.

The brand equity literature recognizes that the degree to which con-

sumers perceive advertising as creative,original and different from

other competing brands are important success factors for advertising

(Kapferer, 2004; Keller, 2007). Interviews with experts also supported

this view.Previous scales,however,did not include these three char-

acteristics (e.g., LaTour et al., 1990; Henthorne et al., 1993). Therefore,

the three-item scale used to measure individuals' attitudes toward the

advertisements takes into accountinsights from the brand equity

literature and experts' opinion. To measure the perceived monetary and

non-monetary promotion intensities the study employs and adapts the

three-item scale of Yoo et al.(2000).Specifically,price discounts and

gifts were used as they are increasingly importantin promotional

strategies (Raghubir, 2005; Palazón and Delgado-Ballester, 2009).

The measurement ofbrand equity is consistent with the multi-

dimensionalconceptualization proposed within the consumer-based

perspective.Drawing from the literature (Lassar et al.,1995; Aaker,

1996; Yoo et al., 2000; Netemeyer et al., 2004; Pappu et al., 2005; 2006),

this research usesfive items to measure brand awareness, four items to

assess perceived quality,nine items to gauge brand associations and

three items to measure brand loyalty.

Table 1 lists the items used to measure each construct.

5. Results

5.1.Measurement model

Exploratory and confirmatory techniques serve to assess the reli-

ability, dimensionality and validity of the multi-item scales. Cronbach's

alpha for all the constructs were above 0.70.Furthermore,the item-

to-total correlations were all above the threshold of 0.30. Subsequently,

exploratory factor analyses using principalcomponents analysis and

varimax rotation method suggested that the corresponding items of

each scale grouped into a single factor (Hair et al., 2006). Only the item

of brand associations dimension loaded on three different factors (items

ASS1,ASS2 and ASS3 refer to perceived value; items ASS4,ASS5 and

ASS6 refer to brand personality; and items ASS7, ASS8 and ASS9 refer t

organizationalassociations).All the indicators were significant,with

factor loadings higher than 0.5 and no cross loading.The explained

variance exceeded 60% in each case.

This study follows Anderson and Gerbing (1988) two-step

approach for structural equation modeling.The analysis uses the

robust maximum-likelihood estimation method in EQS 6.1.Confir-

matory factor analysis (CFA) suggested deleting item ASS6 since the

R2 was below 0.4.After this deletion,CFA of the multi-item scales

produced an acceptable fit to the data (Table 1). All factor loadings are

above 0.5 and are statistically significant.Likewise,the coefficients

have a clear relation with the underlying factor (R2N 0.3). In addition,

the average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR)

values are greater than 0.5 and 0.7 respectively (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988),

which guarantee the internalvalidity of the measurementmodel.

Results also support the discriminant validity of the scales. First, none

of the confidence intervals around the correlation estimate between

any two factors included one (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Further,

the variance extracted for any two constructs was always greater than

the squared correlation estimate (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

5.2.Structural model

The next stage was to examine the hypothesized paths in the

proposed model. Previously, since brand association dimension loaded

on three different factors,the study employed averaged indicators of

the three constructs (Baldauf et al., 2009).

The model conceptualized in Fig.1 yielded a good overall fit.

Table 2 shows the results.

With respect to the effect of the perception of advertising spend

on perceived quality,brand awareness and brand associations,H1a,

H1b and H1c respectively,the results only support hypothesis H1b.

Thus, the higher the advertising spend,the higher the awareness

levels are likely to be.One of the more noteworthy findings is the

failure to support hypotheses H1a and H1c. Contrary to expectations,

advertising spend has an insignificant influence on perceived quality

and brand associations.

Individuals' attitudes toward the advertisements seem to play

an important role in brand equity dimensions.As such,individuals'

attitudes toward the advertisements have a positive and significant

influence on perceived quality, as predicted in hypothesis H2a. Brand

awareness and brand associations are also notably dependenton

individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements,which support hy-

potheses H2b and H2c.

The findings also support H3a.Monetary promotions (i.e.,price

discounts) have negative effects on perceived quality. H3b suggested

that monetary promotions would have a negative effect on brand

associations. However, the data reveals a non-significant effect of this

marketing element on brand associations.By contrast,results show

that non-monetary promotions (i.e., gifts) have a positive and signif-

icant influence on perceived quality, supporting H4a. Similarly, results

support hypothesis H4b,which suggested that non-monetary pro-

motions positively relate to brand associations.

119I. Buil et al./ Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 115–122

Results reveal a significant positive relation between brand

awareness and perceived quality and brand awareness and brand

associations,in support of H5 and H6.By contrast,the relationship

between perceived quality and brand loyalty is negative and

significant.This finding fails to support hypothesis H7.Finally, hy-

pothesis H8 posited that brand associations enhance brand loyalty

Table 2

Structural model results.

Hypotheses Standardized β (t)

H1a Advertising spend → Perceived quality −0.12 (−1.28)

H1b Advertising spend → Brand awareness 0.27⁎⁎ (2.72)

H1c Advertising spend → Brand associations 0.02 (0.21)

H2a Attitudes toward the advertisements → Perceived quality 0.20⁎⁎ (2.05)

H2b Attitudes toward the advertisements → Brand awareness 0.21⁎⁎ (2.01)

H2c Attitudes toward the advertisements → Brand associations 0.37⁎⁎ (3.72)

H3a Monetary promotions → Perceived quality −0.11⁎ (−1.75)

H3b Monetary promotions → Brand associations −0.10 (−1.55)

H4a Non-monetary promotions → Perceived quality 0.13⁎ (1.82)

H4b Non-monetary promotions → Brand associations 0.18⁎⁎ (2.68)

H5 Brand awareness → Perceived quality 0.56⁎⁎ (8.02)

H6 Brand awareness → Brand associations 0.42⁎⁎ (5.30)

H7 Perceived quality → Brand loyalty −0.11⁎⁎ (−2.02)

H8 Brand associations → Brand loyalty 0.71⁎⁎ (9.90)

Fit indices

S-Bχ2= 630.04 (308) (p b 0.001) CFI = 0.94 NFI = 0.88

RMSEA=0.06 IFI = 0.94 NNFI = 0.93

⁎⁎ p b 0.05.

⁎ p b 0.1.

Table 1

Constructs and measurements results.

Constructs and measurement λ (range) CR AVE

Perceived advertising spend Yoo et al.(2000)

ADS1 Brand X is intensively advertised 0.82–0.89 0.90 0.75

ADS2 Brand X seems to spend a lot on its advertising compared to advertising for competing PC brands

ADS3 The advertisements for brand X are frequently shown

Individuals'attitudes toward the advertisements Ad hoc scale

ATA1 The advertisements for brand X are creative 0.81–0.92 0.91 0.76

ATA2 The advertisements for brand X are original

ATA3 The advertisements for brand X are different from the advertisements for competing brands of PC

Monetary promotions Yoo et al.(2000)

MPR1 Brand X frequently offers price discounts 0.79–0.95 0.92 0.80

MPR2 Brand X often uses price discounts

MPR3 Brand X uses price discounts more frequently than competing brands of PC

Non-monetary promotions Yoo et al.(2000)

NMPR1 Brand X frequently offers gifts 0.79–0.94 0.91 0.78

NMPR2 Brand X often uses gifts