An In-depth Analysis of Brazil's Productivity and Monetary Policies

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/14

|10

|2155

|7

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of Brazil's economic performance, focusing on total factor productivity (TFP) and monetary policy. It examines Brazil's slow TFP growth, particularly its negative contribution during specific periods, contrasting it with the contributions of capital and labor. The report highlights the volatility of TFP and its limited contribution to GDP growth, using figures and comparisons to other countries. It also explores the impact of labor accumulation and human capital quality on Brazil's growth relative to other nations. The report further delves into the Mexican economy's financial distress due to monetary policies, contrasting discretionary versus rule-based monetary policy and the consequences of the Mexican government's decisions, including devaluation. The analysis compares the advantages and disadvantages of discretionary monetary policy against currency board rules, drawing conclusions about the importance of stable economic policies.

BRAZIL 1

Brazil

Name

Course

Tutor

University

City/State

Date

Brazil

Name

Course

Tutor

University

City/State

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

BRAZIL 2

Productivity is an important parameter as it serves as a signal to technical efficiency that

demonstrates how firms, industries, and different sectors or the state convert measured inputs

into finished products. The most common measures of productivity entail labor productivity and

total factor productivity (Araújo , et al., 2018). On the other hand, with regards discretion, the

monetary institution has the freedom to operate as per its judgment. A good illustration is if

legislation gave directives to the Federal Reserve to act in its best interest to ensure that the

economy is performing at its best and gifted the monetary authority the tools that it has, the

Federal Reserve, in this case, would be said to be exercising discretionary monetary policy. A

rule, on the other hand, is a limitation on the monetary authority’s discretion. Thus, a rule entails

regulating actions of the monetary authority.

The derivation of total factor productivity entails obtaining the residual of out after the

effect of all evaluated inputs gets accounted for, importantly, labor which entails the

augmentation regarding the quality of human capital, and capital. Thus, TFP encompasses the

efficiency where all inputs are integrated into the production process. TFP, as an evolving

concept, can be thought of as an economic parameter that evaluates technical progress. The

growth of TFP can be a result of reallocating resources to firms that are more efficient across

industries or also due to innovations. Innovation in this context can be as a result of developing a

new product and technology and adapting existing technologies and processes. Thus, the primary

determinant of variations in the rates of economic growth is how various countries use

disposable inputs.

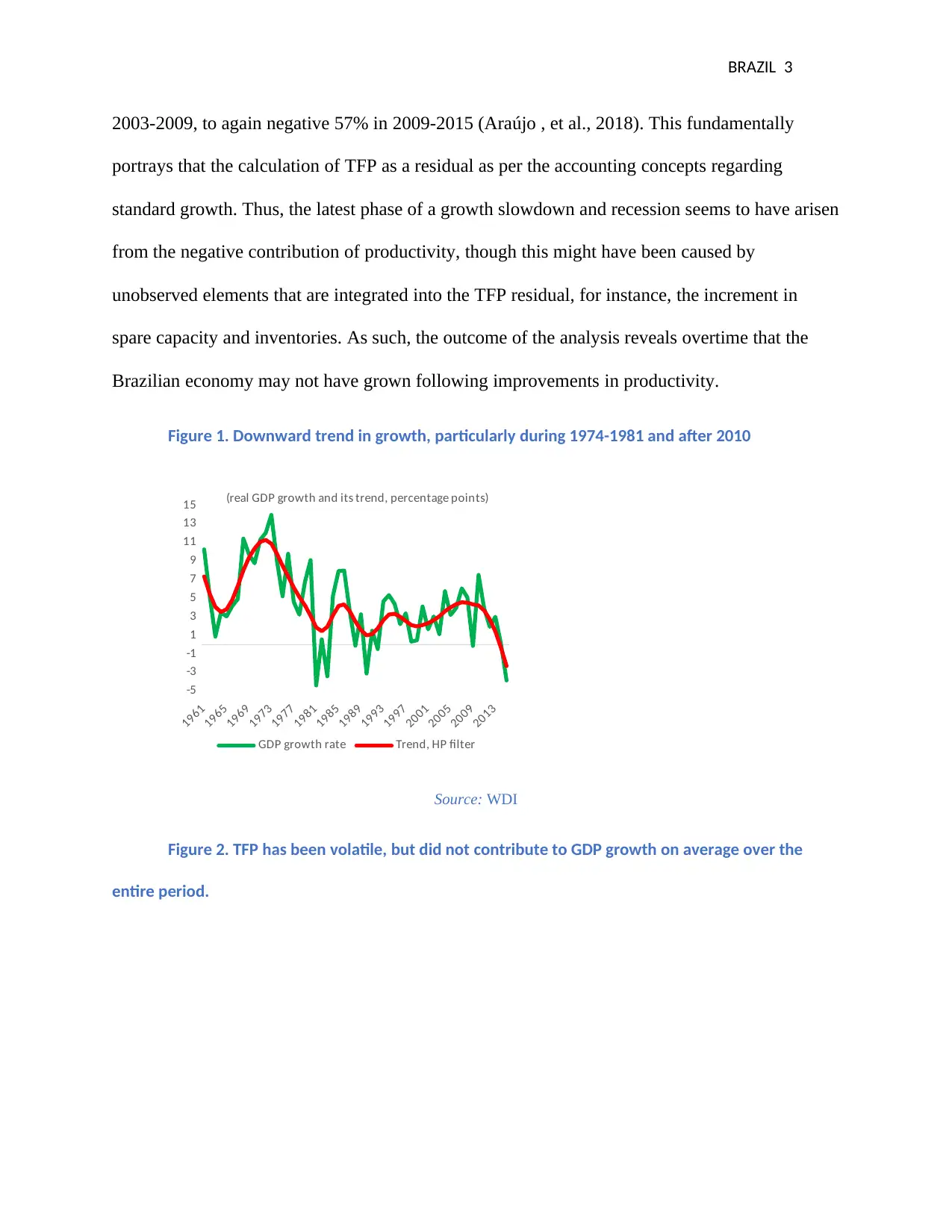

Brazil’s total factor productivity has recorded slow pace in growth exhibiting a negative

contribution in the period between 1996-2015 (de Souza & da Cunha, 2018).TFP’s contribution

to economy-related growth moved from negative 29% during 1996-2003 to positive 39% during

Productivity is an important parameter as it serves as a signal to technical efficiency that

demonstrates how firms, industries, and different sectors or the state convert measured inputs

into finished products. The most common measures of productivity entail labor productivity and

total factor productivity (Araújo , et al., 2018). On the other hand, with regards discretion, the

monetary institution has the freedom to operate as per its judgment. A good illustration is if

legislation gave directives to the Federal Reserve to act in its best interest to ensure that the

economy is performing at its best and gifted the monetary authority the tools that it has, the

Federal Reserve, in this case, would be said to be exercising discretionary monetary policy. A

rule, on the other hand, is a limitation on the monetary authority’s discretion. Thus, a rule entails

regulating actions of the monetary authority.

The derivation of total factor productivity entails obtaining the residual of out after the

effect of all evaluated inputs gets accounted for, importantly, labor which entails the

augmentation regarding the quality of human capital, and capital. Thus, TFP encompasses the

efficiency where all inputs are integrated into the production process. TFP, as an evolving

concept, can be thought of as an economic parameter that evaluates technical progress. The

growth of TFP can be a result of reallocating resources to firms that are more efficient across

industries or also due to innovations. Innovation in this context can be as a result of developing a

new product and technology and adapting existing technologies and processes. Thus, the primary

determinant of variations in the rates of economic growth is how various countries use

disposable inputs.

Brazil’s total factor productivity has recorded slow pace in growth exhibiting a negative

contribution in the period between 1996-2015 (de Souza & da Cunha, 2018).TFP’s contribution

to economy-related growth moved from negative 29% during 1996-2003 to positive 39% during

BRAZIL 3

2003-2009, to again negative 57% in 2009-2015 (Araújo , et al., 2018). This fundamentally

portrays that the calculation of TFP as a residual as per the accounting concepts regarding

standard growth. Thus, the latest phase of a growth slowdown and recession seems to have arisen

from the negative contribution of productivity, though this might have been caused by

unobserved elements that are integrated into the TFP residual, for instance, the increment in

spare capacity and inventories. As such, the outcome of the analysis reveals overtime that the

Brazilian economy may not have grown following improvements in productivity.

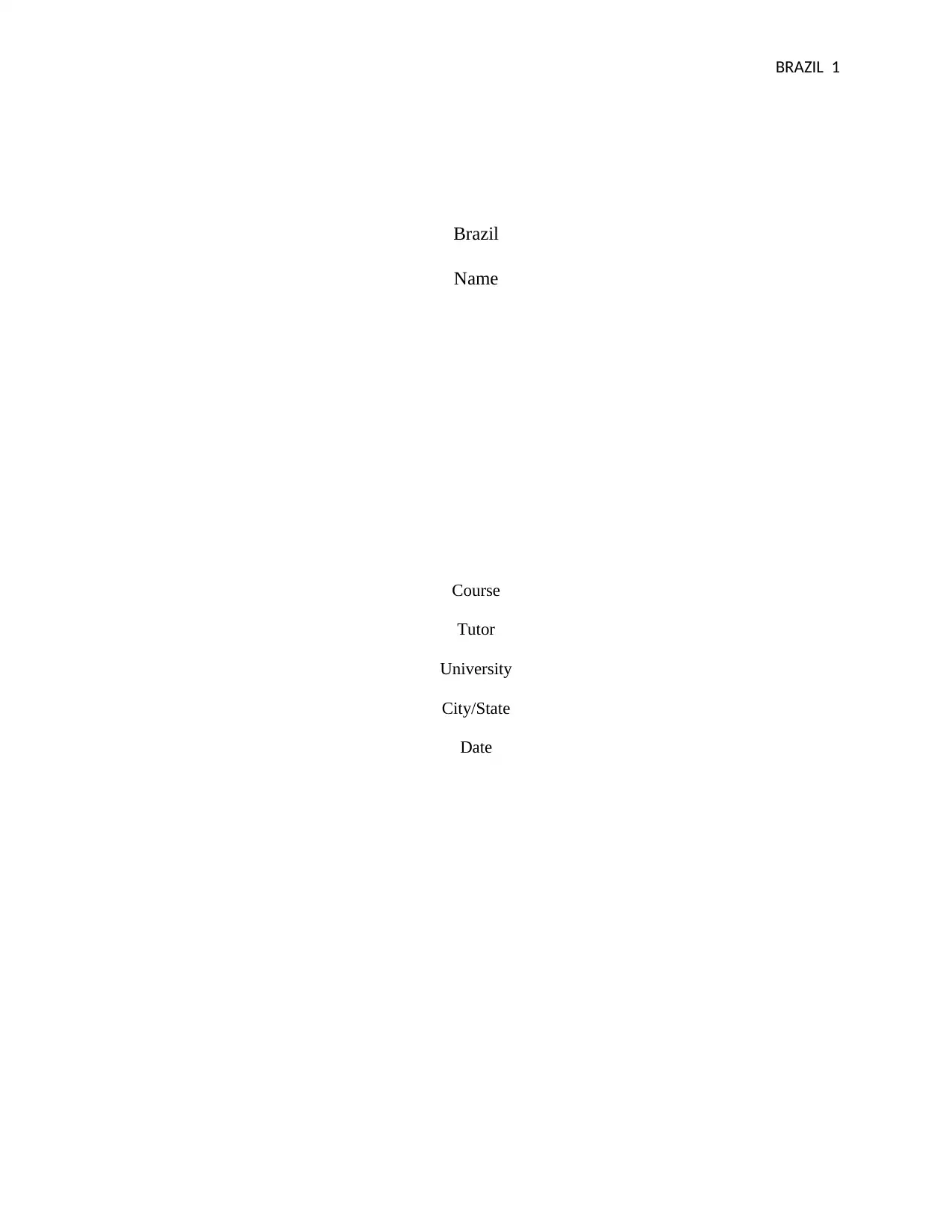

Figure 1. Downward trend in growth, particularly during 1974-1981 and after 2010

1961

1965

1969

1973

1977

1981

1985

1989

1993

1997

2001

2005

2009

2013

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

9

11

13

15 (real GDP growth and its trend, percentage points)

GDP growth rate Trend, HP filter

Source: WDI

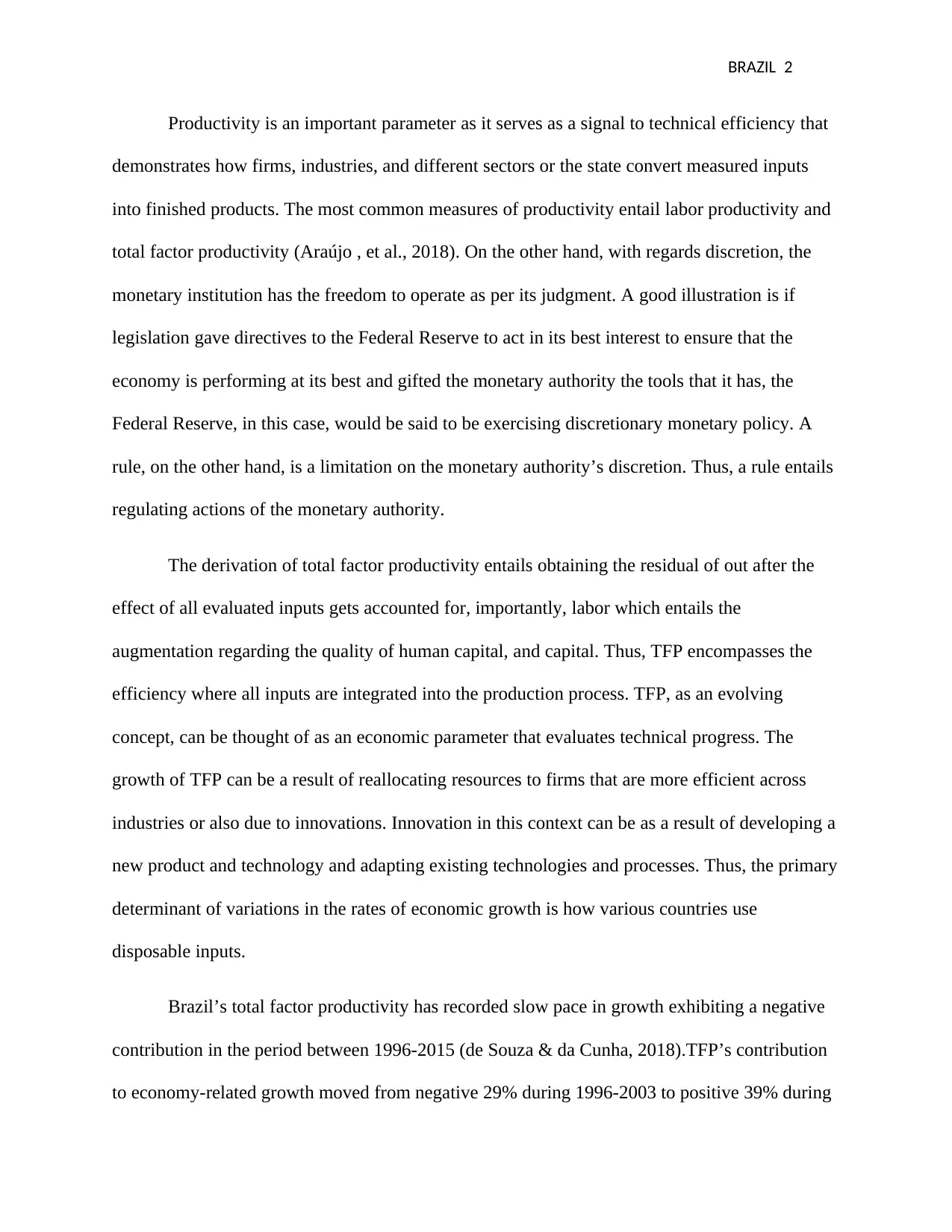

Figure 2. TFP has been volatile, but did not contribute to GDP growth on average over the

entire period.

2003-2009, to again negative 57% in 2009-2015 (Araújo , et al., 2018). This fundamentally

portrays that the calculation of TFP as a residual as per the accounting concepts regarding

standard growth. Thus, the latest phase of a growth slowdown and recession seems to have arisen

from the negative contribution of productivity, though this might have been caused by

unobserved elements that are integrated into the TFP residual, for instance, the increment in

spare capacity and inventories. As such, the outcome of the analysis reveals overtime that the

Brazilian economy may not have grown following improvements in productivity.

Figure 1. Downward trend in growth, particularly during 1974-1981 and after 2010

1961

1965

1969

1973

1977

1981

1985

1989

1993

1997

2001

2005

2009

2013

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

9

11

13

15 (real GDP growth and its trend, percentage points)

GDP growth rate Trend, HP filter

Source: WDI

Figure 2. TFP has been volatile, but did not contribute to GDP growth on average over the

entire period.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

BRAZIL 4

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

(real GDP growth and contributions, percentage

points)

Human Capital Labor

Capital Total Factor Productivity

Real GDP

Source: IBGE, world bank staff calculation

Figure 3. TFP only contributed to Brazil’s growth performance during 2003-2009

1996-2003 2003-2009 2009-2015

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

1.5 0.9 0.8

0.7

0.8 0.4

0.7 0.8 1.5

-0.6

1.6

-1.0

(real GDP growth and contributions, percentage

points)

Labor Human Capital per Labor

Capital Total Factor Productivity

Real GDP

Source: IBGE, world bank staff calculation

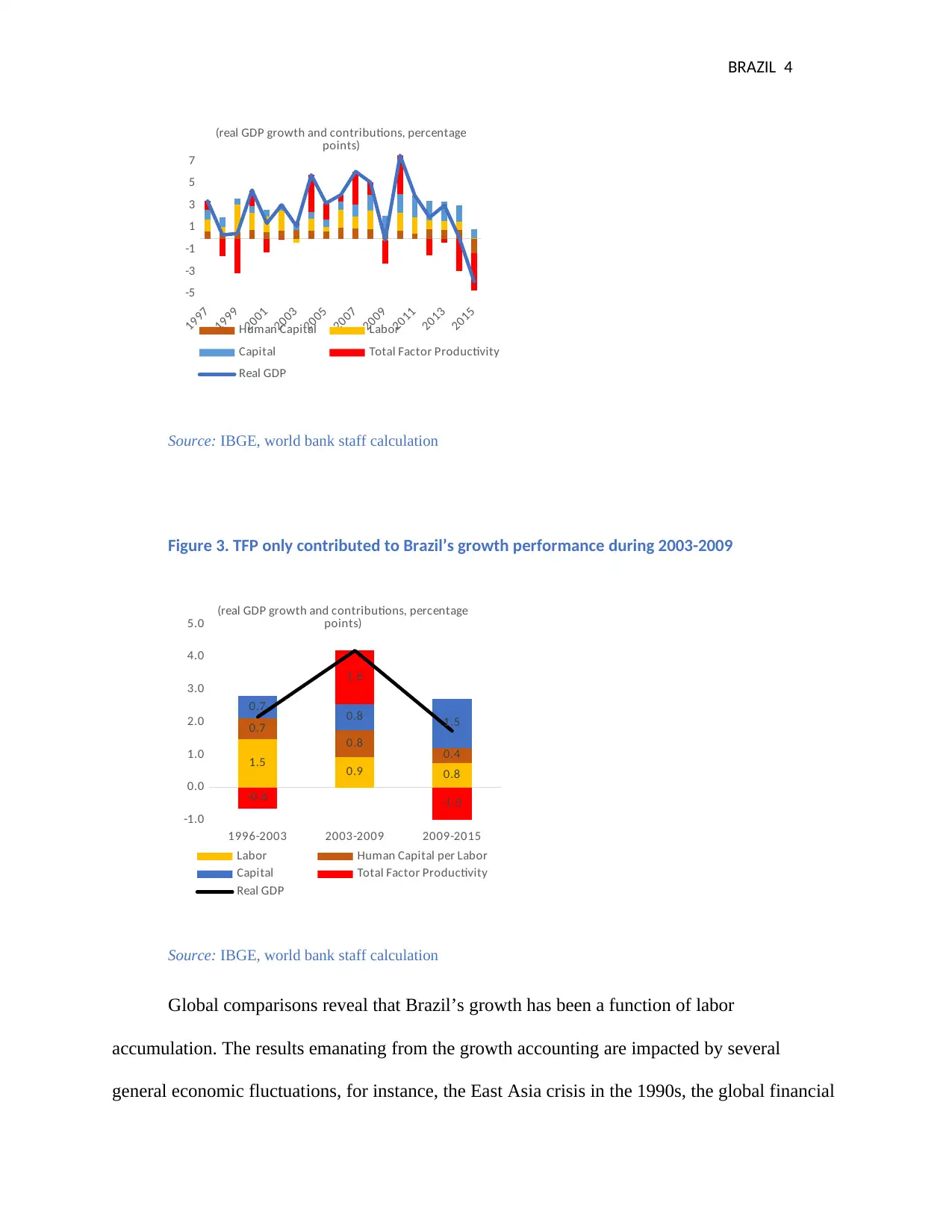

Global comparisons reveal that Brazil’s growth has been a function of labor

accumulation. The results emanating from the growth accounting are impacted by several

general economic fluctuations, for instance, the East Asia crisis in the 1990s, the global financial

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

(real GDP growth and contributions, percentage

points)

Human Capital Labor

Capital Total Factor Productivity

Real GDP

Source: IBGE, world bank staff calculation

Figure 3. TFP only contributed to Brazil’s growth performance during 2003-2009

1996-2003 2003-2009 2009-2015

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

1.5 0.9 0.8

0.7

0.8 0.4

0.7 0.8 1.5

-0.6

1.6

-1.0

(real GDP growth and contributions, percentage

points)

Labor Human Capital per Labor

Capital Total Factor Productivity

Real GDP

Source: IBGE, world bank staff calculation

Global comparisons reveal that Brazil’s growth has been a function of labor

accumulation. The results emanating from the growth accounting are impacted by several

general economic fluctuations, for instance, the East Asia crisis in the 1990s, the global financial

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

BRAZIL 5

crisis witnessed in 2008 and the prevailing recession in Brazil (Araújo , et al., 2018). However,

several clear findings suffice. One is that capital accumulation has downplayed a significant role

in all comparator nations irrespective of analyzing OECD average, LAC average, and China.

Labour contribution in Brazil has been significant compared to any comparator. The improved

quality of human capital was generally in tandem with the rest of the LAC region; however, it

was more significant than that experienced in countries such as China and India where capital

commanded a driving function and also in the growth of productivity.

Figure 4. TFP contribution to growth was above LAC and OECD averages but well below Asian

countries’

1996-

2015

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

Brazil OECD avg LAC East Asia

Avg

China India

-25

-15

-5

5

15

25

35

45

55

65

(contribution to growth, percent)

Capital Stock

Labor

Source: IBGE, WDI, world bank staff calculation

Note: countries included in OECD: OECD members; in LAC: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru; in East

Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Philippines.

crisis witnessed in 2008 and the prevailing recession in Brazil (Araújo , et al., 2018). However,

several clear findings suffice. One is that capital accumulation has downplayed a significant role

in all comparator nations irrespective of analyzing OECD average, LAC average, and China.

Labour contribution in Brazil has been significant compared to any comparator. The improved

quality of human capital was generally in tandem with the rest of the LAC region; however, it

was more significant than that experienced in countries such as China and India where capital

commanded a driving function and also in the growth of productivity.

Figure 4. TFP contribution to growth was above LAC and OECD averages but well below Asian

countries’

1996-

2015

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

1996-

2013

Brazil OECD avg LAC East Asia

Avg

China India

-25

-15

-5

5

15

25

35

45

55

65

(contribution to growth, percent)

Capital Stock

Labor

Source: IBGE, WDI, world bank staff calculation

Note: countries included in OECD: OECD members; in LAC: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru; in East

Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Philippines.

BRAZIL 6

Brazil recorded low TFP as portrayed by the country’s labor productivity which grew less

compared to advanced economies and other emerging nations in the past two decades. This

entails computing value-added per employee as a proxy for labor productivity. The valued-added

per employee in Brazil in between 1995 and 2015 has been rising at approximately the same rate

as the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) nations, though slightly below that reported in

advanced and emerging economies (Araújo , et al., 2018). However, it declined in 2009 in

comparison to other countries in the world. Nevertheless, since 2014, while other emerging and

developed economies exhibited an upward trend in the value-added per employee, the trend in

Brazil and LAC reversed, where Brazil’s rate declined faster compared to LAC. Also, during this

period, the gap regarding labor productivity entailing Brazil and LAC and developed and

emerging economies continued widening. This was contrary to other emerging nations that

recorded productivity in labor growing faster compared to developed economies since 2014, thus

moving to bridge their productivity gap eventually.

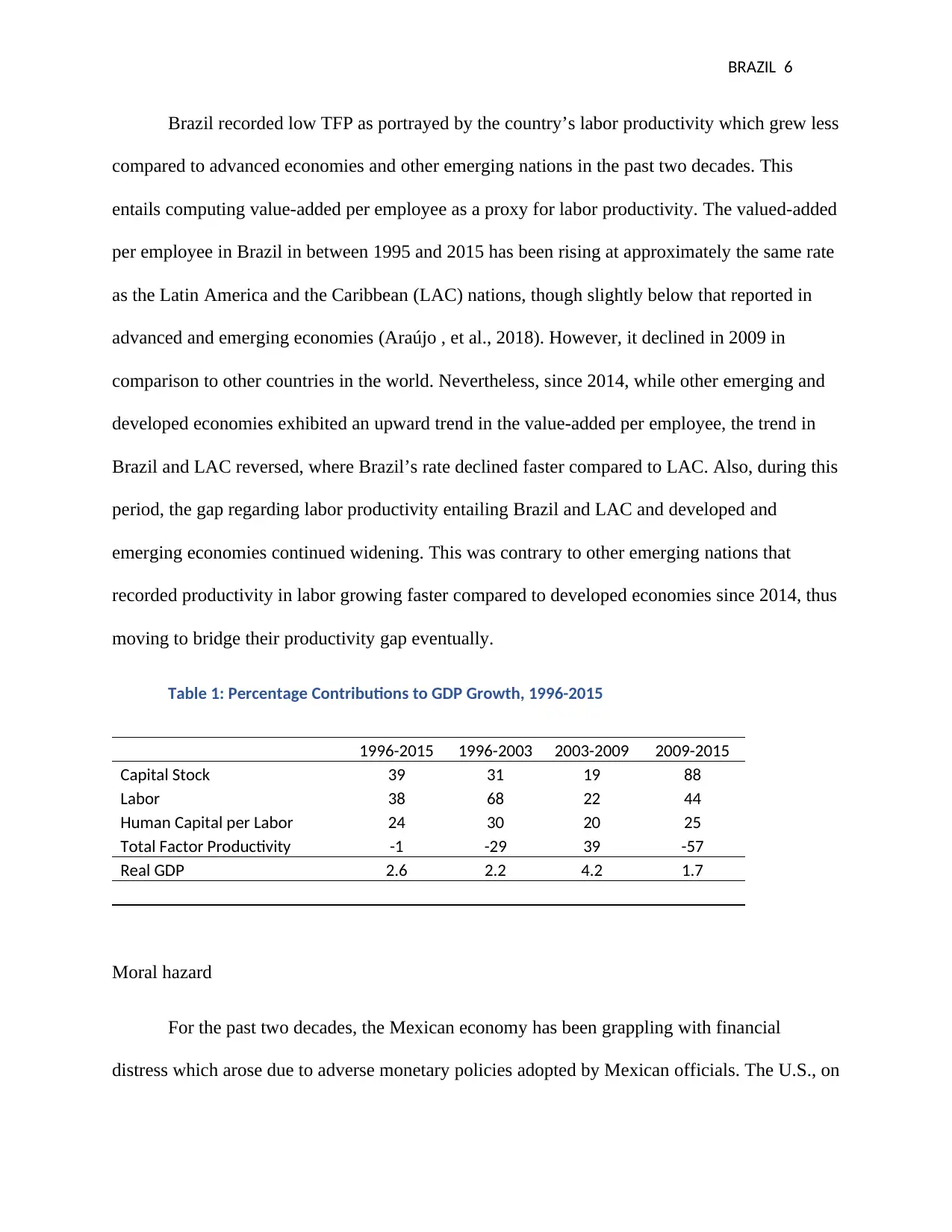

Table 1: Percentage Contributions to GDP Growth, 1996-2015

1996-2015 1996-2003 2003-2009 2009-2015

Capital Stock 39 31 19 88

Labor 38 68 22 44

Human Capital per Labor 24 30 20 25

Total Factor Productivity -1 -29 39 -57

Real GDP 2.6 2.2 4.2 1.7

Moral hazard

For the past two decades, the Mexican economy has been grappling with financial

distress which arose due to adverse monetary policies adopted by Mexican officials. The U.S., on

Brazil recorded low TFP as portrayed by the country’s labor productivity which grew less

compared to advanced economies and other emerging nations in the past two decades. This

entails computing value-added per employee as a proxy for labor productivity. The valued-added

per employee in Brazil in between 1995 and 2015 has been rising at approximately the same rate

as the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) nations, though slightly below that reported in

advanced and emerging economies (Araújo , et al., 2018). However, it declined in 2009 in

comparison to other countries in the world. Nevertheless, since 2014, while other emerging and

developed economies exhibited an upward trend in the value-added per employee, the trend in

Brazil and LAC reversed, where Brazil’s rate declined faster compared to LAC. Also, during this

period, the gap regarding labor productivity entailing Brazil and LAC and developed and

emerging economies continued widening. This was contrary to other emerging nations that

recorded productivity in labor growing faster compared to developed economies since 2014, thus

moving to bridge their productivity gap eventually.

Table 1: Percentage Contributions to GDP Growth, 1996-2015

1996-2015 1996-2003 2003-2009 2009-2015

Capital Stock 39 31 19 88

Labor 38 68 22 44

Human Capital per Labor 24 30 20 25

Total Factor Productivity -1 -29 39 -57

Real GDP 2.6 2.2 4.2 1.7

Moral hazard

For the past two decades, the Mexican economy has been grappling with financial

distress which arose due to adverse monetary policies adopted by Mexican officials. The U.S., on

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

BRAZIL 7

the other hand, acted by lending more money to the government of Mexico as an immediate

palliative. The overall effect is a set of controversial incentives for Mexican administrators and

international investors that facilitates that the crisis resurfaces on a larger magnitude (Meltzer,

2011). Also, the application of Exchange Stabilization Fund by the Treasury and the Federal

Reserve to finance an administration’s international ventures leads to concerns regarding

constitutional matters regarding the separation of authority and ignores the fundamentals of

Central bank autonomy.

Unfortunately, there is no caveat to avoiding the expenses imposed by adverse economic

policies created in the past. The only alternative is to promote market forces, promote the

existence of robust private property rights, stabilize prices, and use a floating exchange rate for

the peso. It by strengthening the institutions that yield such outcomes will Mexico improve its

standards of living.

Loans from international bodies such as the IMF and World Bank are imperative in

addressing a crisis only in short-term but get counterproductive in the long run. The new global

order is that of market solutions as opposed to intrusion by the state.

Rules vs. discretion

Discretionary vs rule in monetary policy in Mexico

As of 1994, the monetary base of Mexico remained relatively stable and subsequently

increased in October despite shrinking of its foreign reserves. This demonstrated that Mexico

was less conservative in accepting divisions from the rules adopted the current board. The

MB$FR ratio moved to the accepted limit of 1.62 in Mexico in December the day prior to

devaluation. It was obvious that a devaluation was more probable in a nation that was backed

the other hand, acted by lending more money to the government of Mexico as an immediate

palliative. The overall effect is a set of controversial incentives for Mexican administrators and

international investors that facilitates that the crisis resurfaces on a larger magnitude (Meltzer,

2011). Also, the application of Exchange Stabilization Fund by the Treasury and the Federal

Reserve to finance an administration’s international ventures leads to concerns regarding

constitutional matters regarding the separation of authority and ignores the fundamentals of

Central bank autonomy.

Unfortunately, there is no caveat to avoiding the expenses imposed by adverse economic

policies created in the past. The only alternative is to promote market forces, promote the

existence of robust private property rights, stabilize prices, and use a floating exchange rate for

the peso. It by strengthening the institutions that yield such outcomes will Mexico improve its

standards of living.

Loans from international bodies such as the IMF and World Bank are imperative in

addressing a crisis only in short-term but get counterproductive in the long run. The new global

order is that of market solutions as opposed to intrusion by the state.

Rules vs. discretion

Discretionary vs rule in monetary policy in Mexico

As of 1994, the monetary base of Mexico remained relatively stable and subsequently

increased in October despite shrinking of its foreign reserves. This demonstrated that Mexico

was less conservative in accepting divisions from the rules adopted the current board. The

MB$FR ratio moved to the accepted limit of 1.62 in Mexico in December the day prior to

devaluation. It was obvious that a devaluation was more probable in a nation that was backed

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

BRAZIL 8

only 20% of its monetary base with foreign reserves as was the case with Mexico towards the

end of 1994; compared to a state that backs 80% or more of its monetary base with foreign

reserves. Surprisingly, until October 1994, Mexico was accustomed to managing its monetary

base using a rule that was beyond the rigor of the standards set by the currency board. Prior to

the fourth-quarter in 1994, MB$FR ratio in Mexico was tagged below one, which implied that

Mexico’s foreign reserves were more than its monetary base. After 1994, Mexico repudiated its

policy without any warnings. The high ratio exhibited in the MB$FR in the fourth quarter

implied that Mexico’s Central Bank was no longer in charge of exchanging the country’s

monetary base for dollars at the pledged exchange rate, rendering Mexico open to speculative

attack, thus, Mexico had to devalue its currency by more than 60%.

The uncertainty associated with a speculative attack became self-fulfilling, leading to a

string of events that facilitated devaluation towards the end of 1994 (Zarazaga, 1996). It is the

continuous drain of Mexico’s foreign exchange that led to the banking industry getting exposed

to the risk entailing liquidity crunch. Thus, the Mexican monetary institutions attempted

preempting the financial uncertainty by operating as the country’s lender of last resort. The

discount window loans ended up expanding the monetary base above the foreign reserves

threshold and this rendered Mexico susceptible to devaluation and speculative attacks

(Kocherlakota, 2016). The expansion of the monetary base via Mexico’s supreme bank discount

window amidst shrinking foreign exchange reserves seems counteractive with the pegged

exchange rate regime that was effective at the time. However, such responses were not

inconsistent depending on the reasons provided by the monetary authorities that the capital

outflows and subsequent decline of foreign reserves were short-term and would normalize once

the worries of political catastrophe were over and that the threshold for local currency had also

only 20% of its monetary base with foreign reserves as was the case with Mexico towards the

end of 1994; compared to a state that backs 80% or more of its monetary base with foreign

reserves. Surprisingly, until October 1994, Mexico was accustomed to managing its monetary

base using a rule that was beyond the rigor of the standards set by the currency board. Prior to

the fourth-quarter in 1994, MB$FR ratio in Mexico was tagged below one, which implied that

Mexico’s foreign reserves were more than its monetary base. After 1994, Mexico repudiated its

policy without any warnings. The high ratio exhibited in the MB$FR in the fourth quarter

implied that Mexico’s Central Bank was no longer in charge of exchanging the country’s

monetary base for dollars at the pledged exchange rate, rendering Mexico open to speculative

attack, thus, Mexico had to devalue its currency by more than 60%.

The uncertainty associated with a speculative attack became self-fulfilling, leading to a

string of events that facilitated devaluation towards the end of 1994 (Zarazaga, 1996). It is the

continuous drain of Mexico’s foreign exchange that led to the banking industry getting exposed

to the risk entailing liquidity crunch. Thus, the Mexican monetary institutions attempted

preempting the financial uncertainty by operating as the country’s lender of last resort. The

discount window loans ended up expanding the monetary base above the foreign reserves

threshold and this rendered Mexico susceptible to devaluation and speculative attacks

(Kocherlakota, 2016). The expansion of the monetary base via Mexico’s supreme bank discount

window amidst shrinking foreign exchange reserves seems counteractive with the pegged

exchange rate regime that was effective at the time. However, such responses were not

inconsistent depending on the reasons provided by the monetary authorities that the capital

outflows and subsequent decline of foreign reserves were short-term and would normalize once

the worries of political catastrophe were over and that the threshold for local currency had also

BRAZIL 9

increased. However, some problems arose as pointed out by Banco de Mexico as the impact of

Mexico’s political uncertainty regarding creditworthiness was underestimated, and the increase

in demand for pesos got overestimated.

Something seemed awkward. Mexico most probably experienced the same challenge that

several countries had faced, their currencies getting devalued following miscalculations by

policymakers about expanding the money base unbacked by foreign reserves (Aragon &

Portugal, 2009). Regarding the case of Mexico, the monetary authorities had allowed the use of

discount window and thus the increase of the unbacked monetary supply to a quantity that was

beyond what the market was willing to accommodate. Since the source of the problem may not

have been unskilled policymakers but the discretion they enjoyed while imposing monetary

policy. For instance, preempting bank runs, then the only remedy to fix the problem would

involve removing the discretion enjoyed by policymakers. This is the logic behind favoring

currency board rules as opposed to discretion.

In conclusion, it is evident how discretionary monetary policy in Mexico led to the

country devaluing its currency following less backing with foreign currency. The result was the

country had limited foreign exchange reserves. In terms of total factor productivity, Mexico has a

lot to remedy to experience growth in its economy.

increased. However, some problems arose as pointed out by Banco de Mexico as the impact of

Mexico’s political uncertainty regarding creditworthiness was underestimated, and the increase

in demand for pesos got overestimated.

Something seemed awkward. Mexico most probably experienced the same challenge that

several countries had faced, their currencies getting devalued following miscalculations by

policymakers about expanding the money base unbacked by foreign reserves (Aragon &

Portugal, 2009). Regarding the case of Mexico, the monetary authorities had allowed the use of

discount window and thus the increase of the unbacked monetary supply to a quantity that was

beyond what the market was willing to accommodate. Since the source of the problem may not

have been unskilled policymakers but the discretion they enjoyed while imposing monetary

policy. For instance, preempting bank runs, then the only remedy to fix the problem would

involve removing the discretion enjoyed by policymakers. This is the logic behind favoring

currency board rules as opposed to discretion.

In conclusion, it is evident how discretionary monetary policy in Mexico led to the

country devaluing its currency following less backing with foreign currency. The result was the

country had limited foreign exchange reserves. In terms of total factor productivity, Mexico has a

lot to remedy to experience growth in its economy.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

BRAZIL 10

References

Aragon, E. K. & Portugal, M. S., 2009. Central bank preferences and monetary rules under the

inflation targeting regime in Brazil. Brazilian Review of Econometrics, 29(1), pp. 79-109.

Araújo , J. T., Qian, R. & Nucifora, A., 2018. Brazil's Productivity Dynamics, s.l.: s.n.

de Souza, T. A. A. & da Cunha, M. S., 2018. Performance of Brazilian total factor productivity

from 2004 to 2014: a sectoral and regional analysis. Journal of Economic Structures, 7(24), pp.

102-125.

Kocherlakota, N., 2016. Rules versus Discretion: A Reconsideration. Rochester, s.n.

Meltzer, A., 2011. Moral Hazard, the IMF, Mexico and Asia. [Online]

Available at: https://kilthub.cmu.edu/articles/Moral_Hazard_the_IMF_Mexico_and_Asia/

6706994/1

[Accessed 25 September 2019].

Zarazaga, C. E., 1996. Argentina, Mexico,And Currency Boards: Another Case of Rules Versus

Discretion. [Online]

Available at:

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f94/1e60a7a68f701ee14862eb204788e48001c0.pdf

[Accessed 25 September 2019].

References

Aragon, E. K. & Portugal, M. S., 2009. Central bank preferences and monetary rules under the

inflation targeting regime in Brazil. Brazilian Review of Econometrics, 29(1), pp. 79-109.

Araújo , J. T., Qian, R. & Nucifora, A., 2018. Brazil's Productivity Dynamics, s.l.: s.n.

de Souza, T. A. A. & da Cunha, M. S., 2018. Performance of Brazilian total factor productivity

from 2004 to 2014: a sectoral and regional analysis. Journal of Economic Structures, 7(24), pp.

102-125.

Kocherlakota, N., 2016. Rules versus Discretion: A Reconsideration. Rochester, s.n.

Meltzer, A., 2011. Moral Hazard, the IMF, Mexico and Asia. [Online]

Available at: https://kilthub.cmu.edu/articles/Moral_Hazard_the_IMF_Mexico_and_Asia/

6706994/1

[Accessed 25 September 2019].

Zarazaga, C. E., 1996. Argentina, Mexico,And Currency Boards: Another Case of Rules Versus

Discretion. [Online]

Available at:

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f94/1e60a7a68f701ee14862eb204788e48001c0.pdf

[Accessed 25 September 2019].

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.