Civil Engineering: BIM Understanding and Activities Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/15

|12

|6240

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a literature review, investigates the understanding and implementation of Building Information Modelling (BIM) within the AECOO (architects, engineers, contractors, operators, owners) industry. It explores the dominant perception of BIM, which often focuses on software usage and technical aspects rather than the broader process of information management and collaboration. The study utilizes Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions (IDDS) as a framework to analyze findings from scientific papers, industry newsletters, ISO standards, and BIM guidance. The research reveals a disparity between the industry's understanding of BIM as a technological tool versus a process for transforming industry practices. The report emphasizes the importance of a shared understanding of BIM to facilitate more effective implementation and achieve objectives for improving the AECOO industry. The study highlights the need for a shift in focus towards the development of skills in information management, collaboration, and the adoption of BIM as a process, not just a program.

BIM UNDERSTANDING AND ACTIVITIES

EILIF HJELSETH

Department of Civil Engineering and Energy Technology, Faculty of Technology, Art, and Design,

Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Norway

ABSTRACT

The AECOO (architects, engineers, contractors, operators, owners) industry is moving toward

increased digitalization. This unstoppable process requires a clear understanding of the important

elements required to reach the defined objectives. The change of process – how we work and interact

– is often highlighted as one of the most important objectives for the AECOO industry. BIM, which

can stand for building information model, modelling, or management, is one of the enablers and most

highlighted initiatives in digitalisation, but there is no joint understanding of BIM. However, our

understating of BIM, and especially the M, will directly influence our actions related to implementing

BIM with objectives that can be documented. This study is based on a literature review of scientific

papers, the buildingSMART Norway newsletter, an overview of BIM-related ISO standards and BIM

guidance, and experiences with the digital implementation of BIM guidance. Integrated design and

delivery solutions (IDDS) focus on the integration of collaboration between people, integrated

processes, and interoperable technology. It has, therefore, been used as a framework for exploring the

dominating understanding of BIM. The findings from this study indicate that BIM primary is

understood as the use of software programs. Activities for implementation are related to solving the

technical aspect of the development of software as well as the exchange of files. Software skills and

the use of software are used as indicators of the degree of BIM implementation. Activities related to

the development of skills for information management were hard to identify, except in large projects.

The understanding of BIM revealed in this study stands in contradiction to numerous statements

claiming BIM as a process for changing the AECOO industry. An increased awareness of our real

understanding and how this influences our activities can contribute to more targeted activities for

implementing BIM to realize objectives for improving the AECOO industry.

Keywords: BIM, building information model, building information modelling, building information

management, BIM guidance, BIM manuals, BIM standards.

1 IMPORTANCE OF JOINT UNDERSTANDING OF BIM

BIM is nowadays a widely used term in the AECOO (architects, engineers, contractors,

operators, owners) industry. However, “widely used” does not imply “well understood.”

Understanding a term has a direct influence on one’s response to it. This understanding is

often considered tacit knowledge, which makes it easy to underestimate the impact of the

term. There is general agreement in the AECOO industry that the current level of

implementation of BIM is far below what was expected about five or 10 years ago [1]–[5].

Could this have some connection to how we understand BIM and the efforts on which we

focus when implementing BIM in individual companies or in the industry in general?

This paper explores and critically reviews the use and understanding of BIM in the

AECOO industry. In the widely used BIM-handbook by Eastman et al. [6], BIM can be

treated as a single term, and not necessarily as an abbreviation for building information

modelling, building information model, or building information management. An alternative

approach is, of course, to state from the beginning that BIM is all three of these or to use all

of the words instead of the abbreviation. However, each of these elements/perspectives still

needs to be understood in full, not just recognized.

Numerous presentations state clearly that BIM is an abbreviation for building information

modelling, and where modelling indicates that BIM is about processes, it is a new way of

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 3

doi:10.2495/BIM170011

EILIF HJELSETH

Department of Civil Engineering and Energy Technology, Faculty of Technology, Art, and Design,

Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Norway

ABSTRACT

The AECOO (architects, engineers, contractors, operators, owners) industry is moving toward

increased digitalization. This unstoppable process requires a clear understanding of the important

elements required to reach the defined objectives. The change of process – how we work and interact

– is often highlighted as one of the most important objectives for the AECOO industry. BIM, which

can stand for building information model, modelling, or management, is one of the enablers and most

highlighted initiatives in digitalisation, but there is no joint understanding of BIM. However, our

understating of BIM, and especially the M, will directly influence our actions related to implementing

BIM with objectives that can be documented. This study is based on a literature review of scientific

papers, the buildingSMART Norway newsletter, an overview of BIM-related ISO standards and BIM

guidance, and experiences with the digital implementation of BIM guidance. Integrated design and

delivery solutions (IDDS) focus on the integration of collaboration between people, integrated

processes, and interoperable technology. It has, therefore, been used as a framework for exploring the

dominating understanding of BIM. The findings from this study indicate that BIM primary is

understood as the use of software programs. Activities for implementation are related to solving the

technical aspect of the development of software as well as the exchange of files. Software skills and

the use of software are used as indicators of the degree of BIM implementation. Activities related to

the development of skills for information management were hard to identify, except in large projects.

The understanding of BIM revealed in this study stands in contradiction to numerous statements

claiming BIM as a process for changing the AECOO industry. An increased awareness of our real

understanding and how this influences our activities can contribute to more targeted activities for

implementing BIM to realize objectives for improving the AECOO industry.

Keywords: BIM, building information model, building information modelling, building information

management, BIM guidance, BIM manuals, BIM standards.

1 IMPORTANCE OF JOINT UNDERSTANDING OF BIM

BIM is nowadays a widely used term in the AECOO (architects, engineers, contractors,

operators, owners) industry. However, “widely used” does not imply “well understood.”

Understanding a term has a direct influence on one’s response to it. This understanding is

often considered tacit knowledge, which makes it easy to underestimate the impact of the

term. There is general agreement in the AECOO industry that the current level of

implementation of BIM is far below what was expected about five or 10 years ago [1]–[5].

Could this have some connection to how we understand BIM and the efforts on which we

focus when implementing BIM in individual companies or in the industry in general?

This paper explores and critically reviews the use and understanding of BIM in the

AECOO industry. In the widely used BIM-handbook by Eastman et al. [6], BIM can be

treated as a single term, and not necessarily as an abbreviation for building information

modelling, building information model, or building information management. An alternative

approach is, of course, to state from the beginning that BIM is all three of these or to use all

of the words instead of the abbreviation. However, each of these elements/perspectives still

needs to be understood in full, not just recognized.

Numerous presentations state clearly that BIM is an abbreviation for building information

modelling, and where modelling indicates that BIM is about processes, it is a new way of

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 3

doi:10.2495/BIM170011

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

working and collaborating. These types of presentations have received recognizing nods and

applause. “BIM is a process that’s enabled by technology. You can’t buy it in a box, it’s not

a software solution, and it’s something you can’t do in isolation” [7, p. 349]. Also,

“Measuring BIM benefits and cost consistently apportioning to who get what’s benefit and

why is difficult. The reality is that everyone in the supply chain benefits when using BIM in

a collaborative way” [7, p. 352].

The BS PAS1192 series of standards for information management from the United

Kingdom (UK) is going to be developed as ISO [8] and CEN [9] standards. These standards

can have an important impact on the understanding of the BIM-based process in the AEC

industry.

This study focuses on whether BIM is understood as a program versus a process. A

program includes software tools, training and hardware, things that can be bought as generic

product or services. A process includes documented descriptions of procedures for ways of

working and collaborating with BIM in projects. The project (or company) specify this in

separate documents like BIM guidance (BIM manuals), or documents describing how

defined parts in specified standards, BIM guidance from third part (e.g. national or industry

BIM guidance) or other normative documents shall be used in the project.

This can be identified by exploring how much effort is placed on software versus

development of soft skills (implementing standards, procedures), versus new ways of

collaborating. The research question is aimed at uncovering this by exploring the options

of program versus process versus people.

The research question in this study is: What is the dominating understanding of BIM?

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

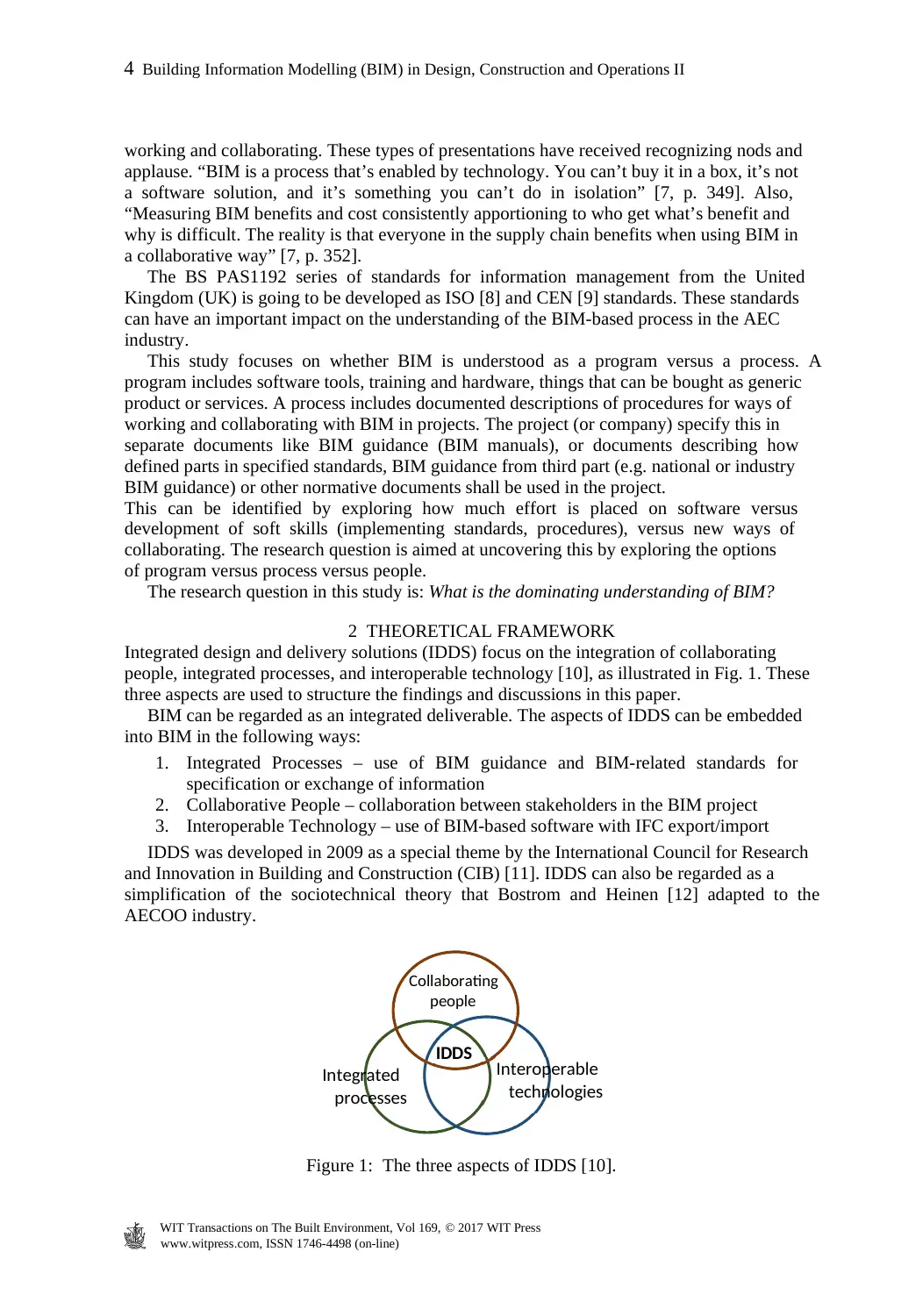

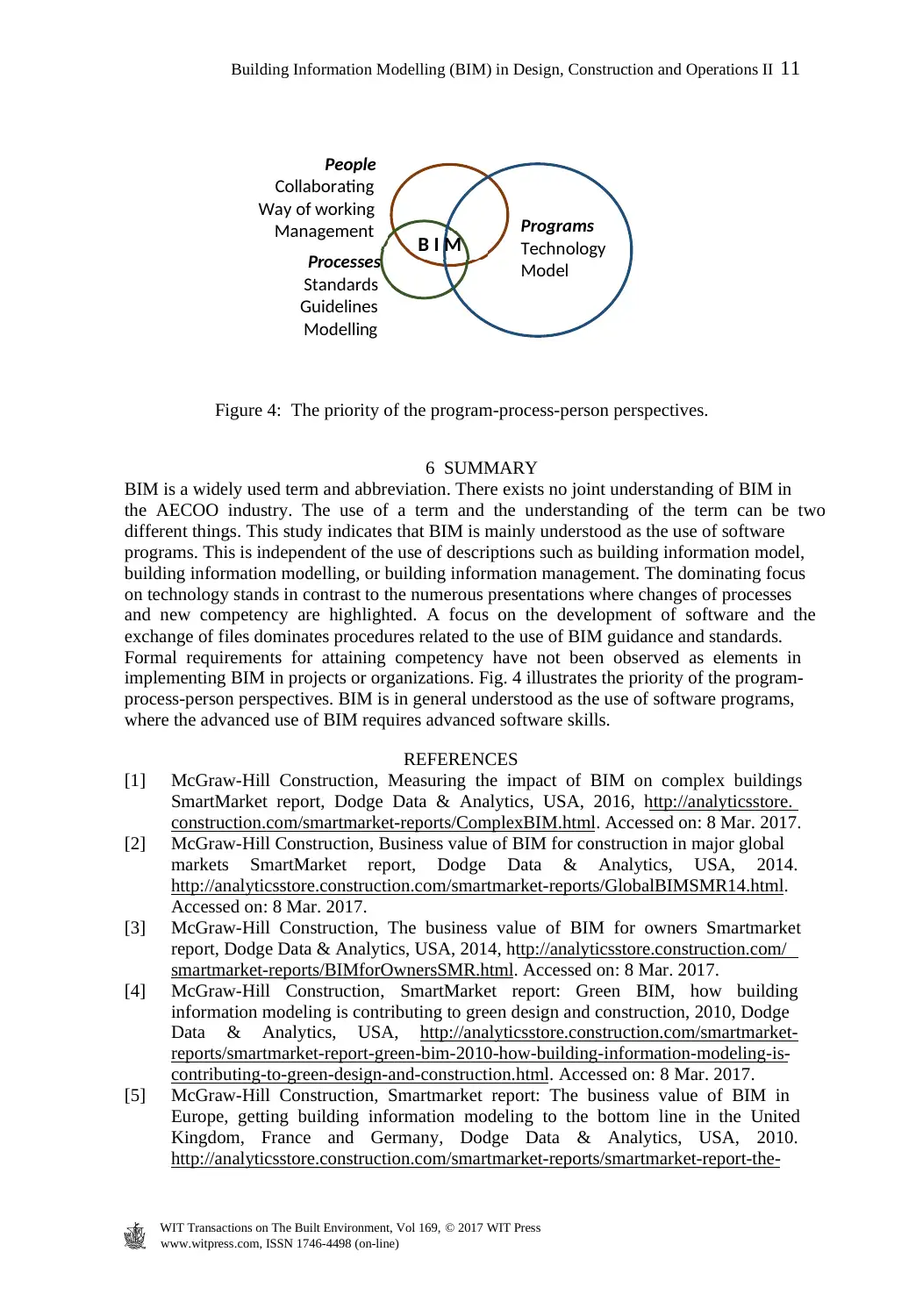

Integrated design and delivery solutions (IDDS) focus on the integration of collaborating

people, integrated processes, and interoperable technology [10], as illustrated in Fig. 1. These

three aspects are used to structure the findings and discussions in this paper.

BIM can be regarded as an integrated deliverable. The aspects of IDDS can be embedded

into BIM in the following ways:

1. Integrated Processes – use of BIM guidance and BIM-related standards for

specification or exchange of information

2. Collaborative People – collaboration between stakeholders in the BIM project

3. Interoperable Technology – use of BIM-based software with IFC export/import

IDDS was developed in 2009 as a special theme by the International Council for Research

and Innovation in Building and Construction (CIB) [11]. IDDS can also be regarded as a

simplification of the sociotechnical theory that Bostrom and Heinen [12] adapted to the

AECOO industry.

Figure 1: The three aspects of IDDS [10].

Collaborating

people

IDDS Interoperable

technologies

Integrated

processes

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

4 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

applause. “BIM is a process that’s enabled by technology. You can’t buy it in a box, it’s not

a software solution, and it’s something you can’t do in isolation” [7, p. 349]. Also,

“Measuring BIM benefits and cost consistently apportioning to who get what’s benefit and

why is difficult. The reality is that everyone in the supply chain benefits when using BIM in

a collaborative way” [7, p. 352].

The BS PAS1192 series of standards for information management from the United

Kingdom (UK) is going to be developed as ISO [8] and CEN [9] standards. These standards

can have an important impact on the understanding of the BIM-based process in the AEC

industry.

This study focuses on whether BIM is understood as a program versus a process. A

program includes software tools, training and hardware, things that can be bought as generic

product or services. A process includes documented descriptions of procedures for ways of

working and collaborating with BIM in projects. The project (or company) specify this in

separate documents like BIM guidance (BIM manuals), or documents describing how

defined parts in specified standards, BIM guidance from third part (e.g. national or industry

BIM guidance) or other normative documents shall be used in the project.

This can be identified by exploring how much effort is placed on software versus

development of soft skills (implementing standards, procedures), versus new ways of

collaborating. The research question is aimed at uncovering this by exploring the options

of program versus process versus people.

The research question in this study is: What is the dominating understanding of BIM?

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Integrated design and delivery solutions (IDDS) focus on the integration of collaborating

people, integrated processes, and interoperable technology [10], as illustrated in Fig. 1. These

three aspects are used to structure the findings and discussions in this paper.

BIM can be regarded as an integrated deliverable. The aspects of IDDS can be embedded

into BIM in the following ways:

1. Integrated Processes – use of BIM guidance and BIM-related standards for

specification or exchange of information

2. Collaborative People – collaboration between stakeholders in the BIM project

3. Interoperable Technology – use of BIM-based software with IFC export/import

IDDS was developed in 2009 as a special theme by the International Council for Research

and Innovation in Building and Construction (CIB) [11]. IDDS can also be regarded as a

simplification of the sociotechnical theory that Bostrom and Heinen [12] adapted to the

AECOO industry.

Figure 1: The three aspects of IDDS [10].

Collaborating

people

IDDS Interoperable

technologies

Integrated

processes

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

4 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

3 METHODS AND MATERIALS

This study used a qualitative approach based on a literature review of multiple sources to

obtain an overview of the situation in the AECOO industry. By using multiple sources, this

study identifies sources that could be applicable to further studies, either qualitative or

quantitative ones. Where numbers are compared, the precision of the numbers helps to

illustrate a situation and trend, not a short time comparison. The multiple sources used come

from around the world to provide a general impression either program of process is given

priority. This study therefore does not include national queries. National differences can be

expected, and more in-depth studies including queries could be used to explore and compare

situations, but this is not the scope of this study. IDDS is used as the framework for the

classification of findings.

This study includes (1) the classification of papers from AutoCON from 2013 to 2017 to

explore the focus on the research and to determine where the development in the industry has

taken place. To explore which themes are in focus in the industry, an (almost) bi-monthly

newsletter (2) from buildingSMART Norway has been used. An overview of ISO standards

(3) and BIM guidance (4), as well as when they were developed, is included to illustrate that

support for BIM as a process has been available for long time. BIM guidance is made for the

manual validation of content in BIM files. A survey (5) about the automatic validation

processing of BIM requirements is included to illustrate that processes can be supported by

programs such as BIM-based model checkers. Each (#) above refers to a subchapter of

Section 4 below.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Research perspectives in AutoCON papers

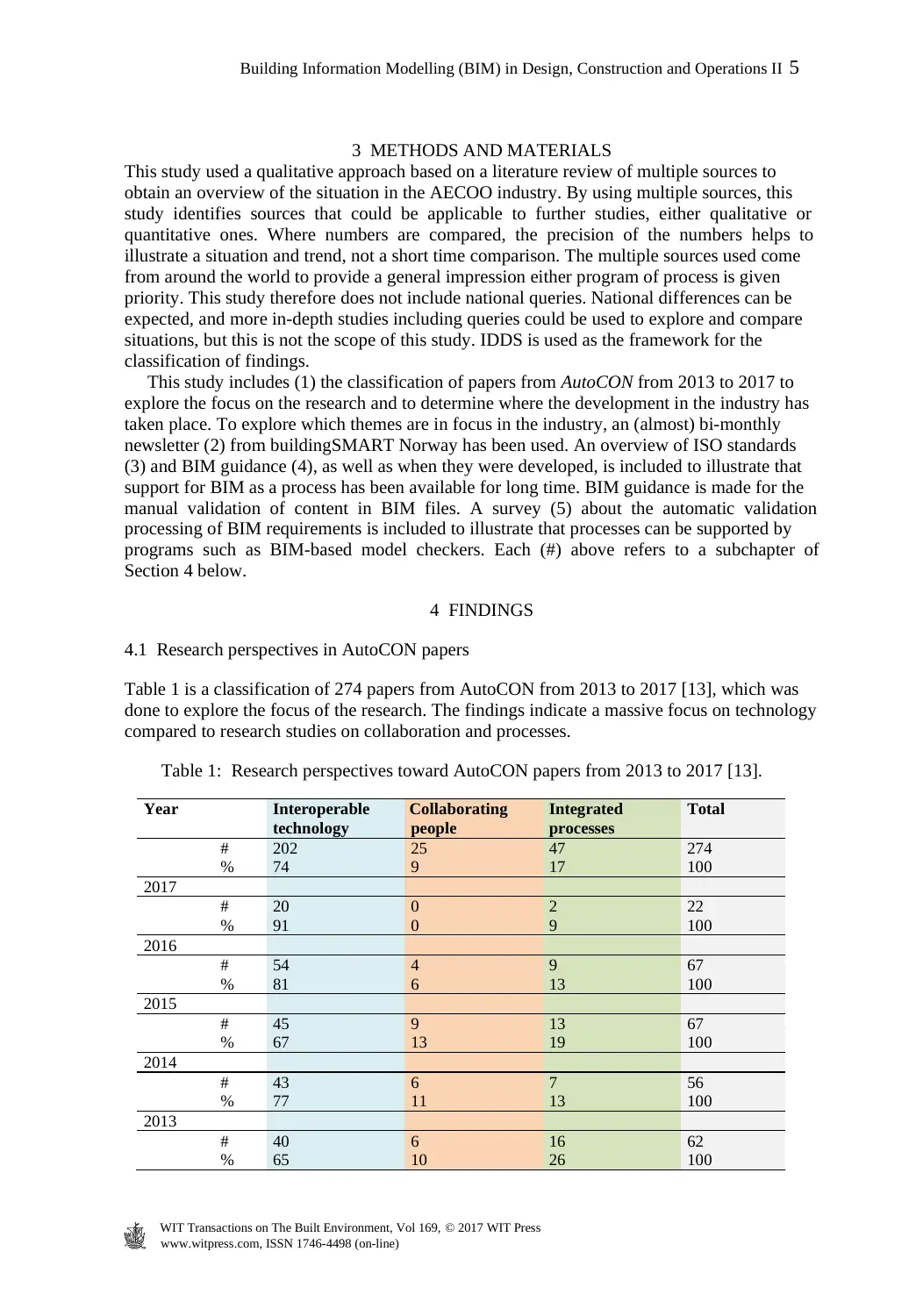

Table 1 is a classification of 274 papers from AutoCON from 2013 to 2017 [13], which was

done to explore the focus of the research. The findings indicate a massive focus on technology

compared to research studies on collaboration and processes.

Table 1: Research perspectives toward AutoCON papers from 2013 to 2017 [13].

Year Interoperable

technology

Collaborating

people

Integrated

processes

Total

# 202 25 47 274

% 74 9 17 100

2017

# 20 0 2 22

% 91 0 9 100

2016

# 54 4 9 67

% 81 6 13 100

2015

# 45 9 13 67

% 67 13 19 100

2014

# 43 6 7 56

% 77 11 13 100

2013

# 40 6 16 62

% 65 10 26 100

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 5

This study used a qualitative approach based on a literature review of multiple sources to

obtain an overview of the situation in the AECOO industry. By using multiple sources, this

study identifies sources that could be applicable to further studies, either qualitative or

quantitative ones. Where numbers are compared, the precision of the numbers helps to

illustrate a situation and trend, not a short time comparison. The multiple sources used come

from around the world to provide a general impression either program of process is given

priority. This study therefore does not include national queries. National differences can be

expected, and more in-depth studies including queries could be used to explore and compare

situations, but this is not the scope of this study. IDDS is used as the framework for the

classification of findings.

This study includes (1) the classification of papers from AutoCON from 2013 to 2017 to

explore the focus on the research and to determine where the development in the industry has

taken place. To explore which themes are in focus in the industry, an (almost) bi-monthly

newsletter (2) from buildingSMART Norway has been used. An overview of ISO standards

(3) and BIM guidance (4), as well as when they were developed, is included to illustrate that

support for BIM as a process has been available for long time. BIM guidance is made for the

manual validation of content in BIM files. A survey (5) about the automatic validation

processing of BIM requirements is included to illustrate that processes can be supported by

programs such as BIM-based model checkers. Each (#) above refers to a subchapter of

Section 4 below.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Research perspectives in AutoCON papers

Table 1 is a classification of 274 papers from AutoCON from 2013 to 2017 [13], which was

done to explore the focus of the research. The findings indicate a massive focus on technology

compared to research studies on collaboration and processes.

Table 1: Research perspectives toward AutoCON papers from 2013 to 2017 [13].

Year Interoperable

technology

Collaborating

people

Integrated

processes

Total

# 202 25 47 274

% 74 9 17 100

2017

# 20 0 2 22

% 91 0 9 100

2016

# 54 4 9 67

% 81 6 13 100

2015

# 45 9 13 67

% 67 13 19 100

2014

# 43 6 7 56

% 77 11 13 100

2013

# 40 6 16 62

% 65 10 26 100

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

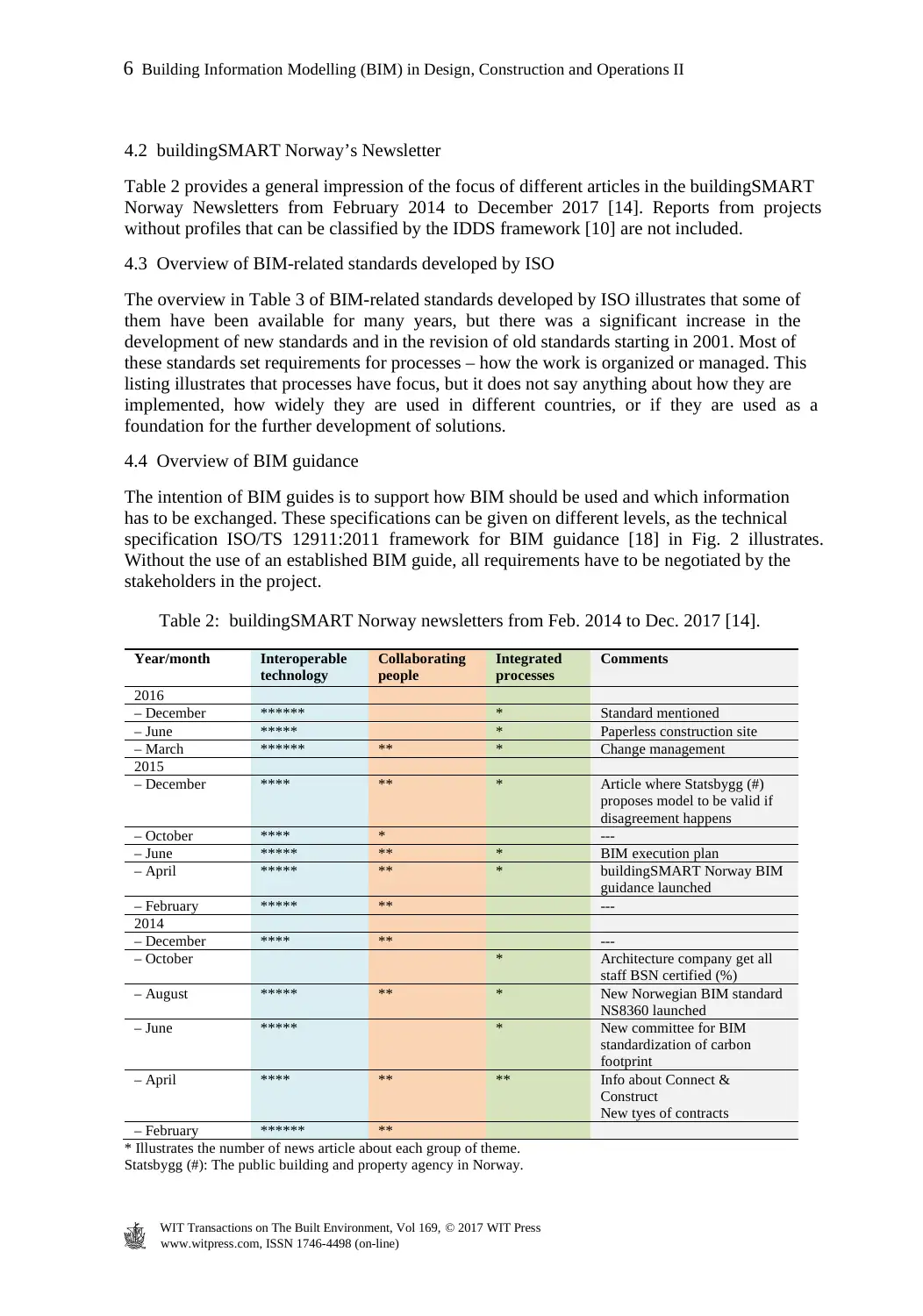

4.2 buildingSMART Norway’s Newsletter

Table 2 provides a general impression of the focus of different articles in the buildingSMART

Norway Newsletters from February 2014 to December 2017 [14]. Reports from projects

without profiles that can be classified by the IDDS framework [10] are not included.

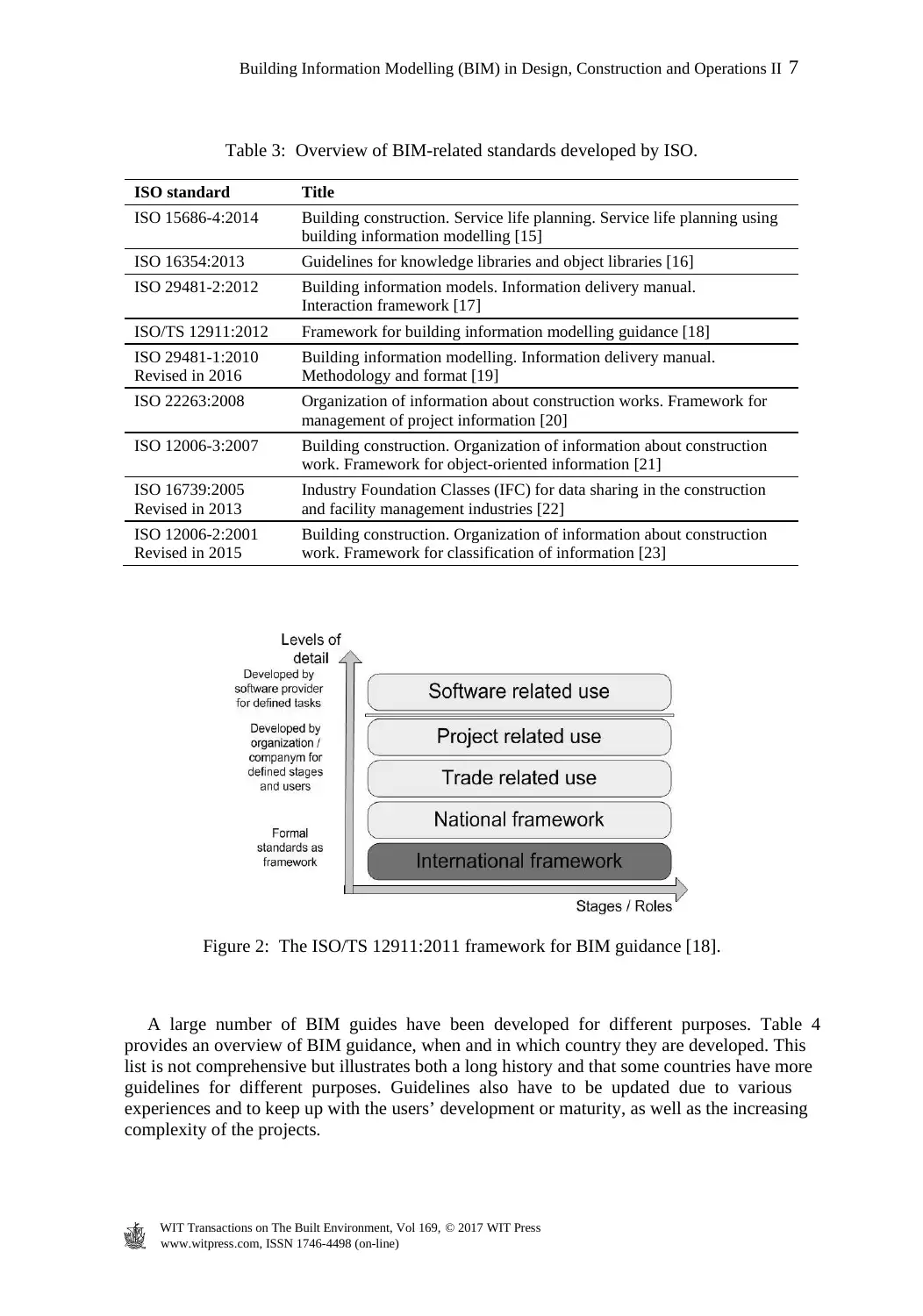

4.3 Overview of BIM-related standards developed by ISO

The overview in Table 3 of BIM-related standards developed by ISO illustrates that some of

them have been available for many years, but there was a significant increase in the

development of new standards and in the revision of old standards starting in 2001. Most of

these standards set requirements for processes – how the work is organized or managed. This

listing illustrates that processes have focus, but it does not say anything about how they are

implemented, how widely they are used in different countries, or if they are used as a

foundation for the further development of solutions.

4.4 Overview of BIM guidance

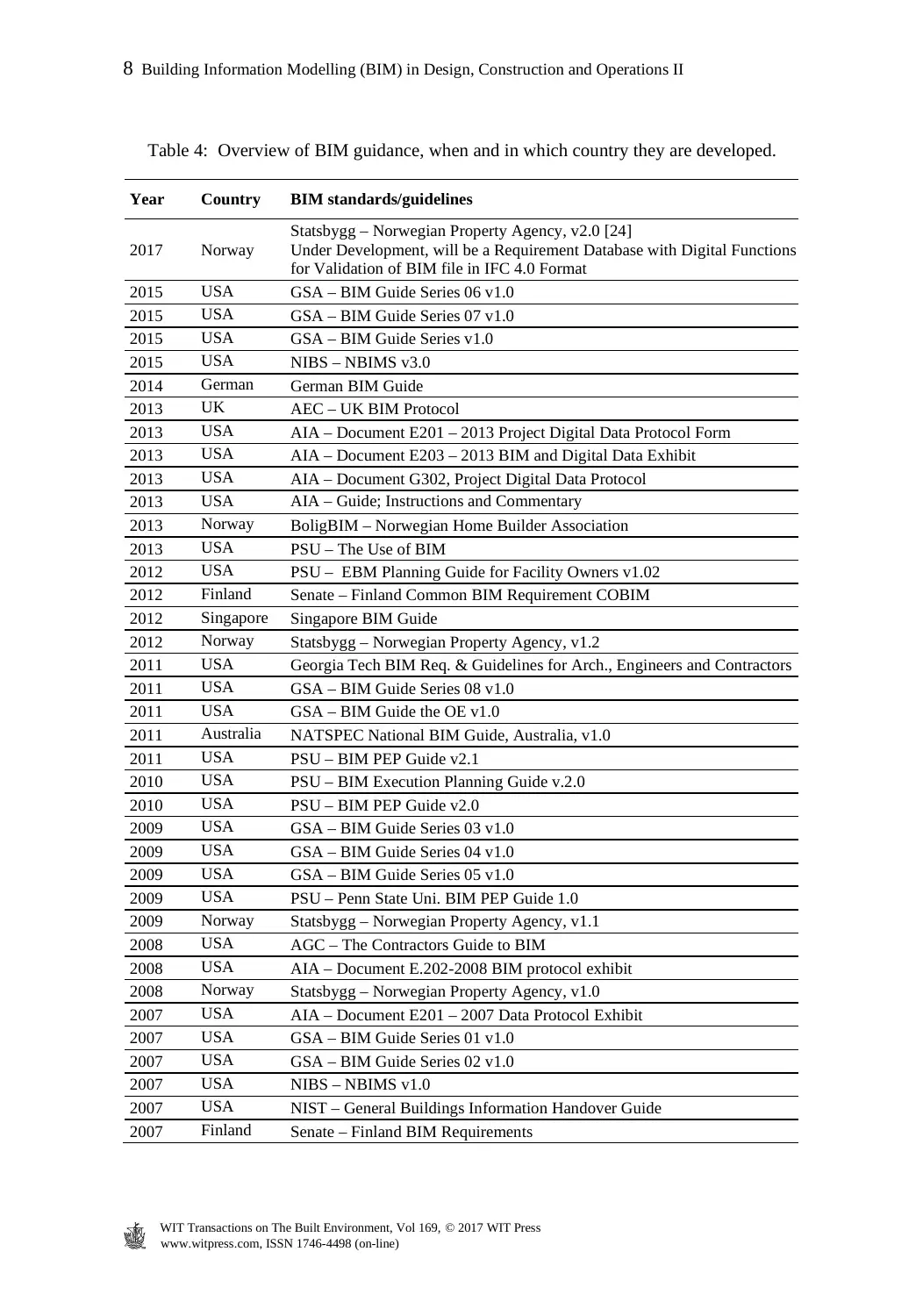

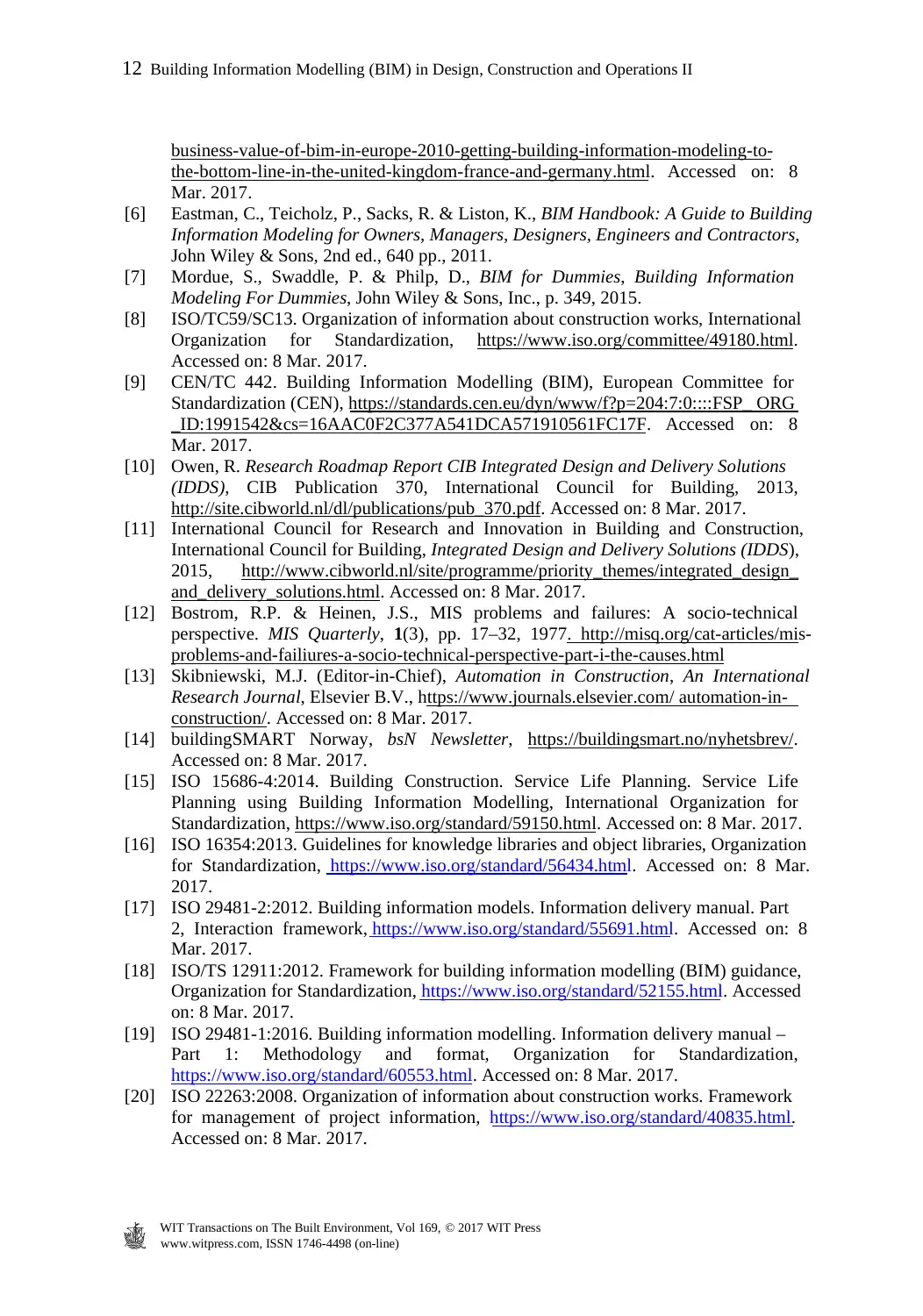

The intention of BIM guides is to support how BIM should be used and which information

has to be exchanged. These specifications can be given on different levels, as the technical

specification ISO/TS 12911:2011 framework for BIM guidance [18] in Fig. 2 illustrates.

Without the use of an established BIM guide, all requirements have to be negotiated by the

stakeholders in the project.

Table 2: buildingSMART Norway newsletters from Feb. 2014 to Dec. 2017 [14].

Year/month Interoperable

technology

Collaborating

people

Integrated

processes

Comments

2016

– December ****** * Standard mentioned

– June ***** * Paperless construction site

– March ****** ** * Change management

2015

– December **** ** * Article where Statsbygg (#)

proposes model to be valid if

disagreement happens

– October **** * ---

– June ***** ** * BIM execution plan

– April ***** ** * buildingSMART Norway BIM

guidance launched

– February ***** ** ---

2014

– December **** ** ---

– October * Architecture company get all

staff BSN certified (%)

– August ***** ** * New Norwegian BIM standard

NS8360 launched

– June ***** * New committee for BIM

standardization of carbon

footprint

– April **** ** ** Info about Connect &

Construct

New tyes of contracts

– February ****** **

* Illustrates the number of news article about each group of theme.

Statsbygg (#): The public building and property agency in Norway.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

6 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

Table 2 provides a general impression of the focus of different articles in the buildingSMART

Norway Newsletters from February 2014 to December 2017 [14]. Reports from projects

without profiles that can be classified by the IDDS framework [10] are not included.

4.3 Overview of BIM-related standards developed by ISO

The overview in Table 3 of BIM-related standards developed by ISO illustrates that some of

them have been available for many years, but there was a significant increase in the

development of new standards and in the revision of old standards starting in 2001. Most of

these standards set requirements for processes – how the work is organized or managed. This

listing illustrates that processes have focus, but it does not say anything about how they are

implemented, how widely they are used in different countries, or if they are used as a

foundation for the further development of solutions.

4.4 Overview of BIM guidance

The intention of BIM guides is to support how BIM should be used and which information

has to be exchanged. These specifications can be given on different levels, as the technical

specification ISO/TS 12911:2011 framework for BIM guidance [18] in Fig. 2 illustrates.

Without the use of an established BIM guide, all requirements have to be negotiated by the

stakeholders in the project.

Table 2: buildingSMART Norway newsletters from Feb. 2014 to Dec. 2017 [14].

Year/month Interoperable

technology

Collaborating

people

Integrated

processes

Comments

2016

– December ****** * Standard mentioned

– June ***** * Paperless construction site

– March ****** ** * Change management

2015

– December **** ** * Article where Statsbygg (#)

proposes model to be valid if

disagreement happens

– October **** * ---

– June ***** ** * BIM execution plan

– April ***** ** * buildingSMART Norway BIM

guidance launched

– February ***** ** ---

2014

– December **** ** ---

– October * Architecture company get all

staff BSN certified (%)

– August ***** ** * New Norwegian BIM standard

NS8360 launched

– June ***** * New committee for BIM

standardization of carbon

footprint

– April **** ** ** Info about Connect &

Construct

New tyes of contracts

– February ****** **

* Illustrates the number of news article about each group of theme.

Statsbygg (#): The public building and property agency in Norway.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

6 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 3: Overview of BIM-related standards developed by ISO.

ISO standard Title

ISO 15686-4:2014 Building construction. Service life planning. Service life planning using

building information modelling [15]

ISO 16354:2013 Guidelines for knowledge libraries and object libraries [16]

ISO 29481-2:2012 Building information models. Information delivery manual.

Interaction framework [17]

ISO/TS 12911:2012 Framework for building information modelling guidance [18]

ISO 29481-1:2010

Revised in 2016

Building information modelling. Information delivery manual.

Methodology and format [19]

ISO 22263:2008 Organization of information about construction works. Framework for

management of project information [20]

ISO 12006-3:2007 Building construction. Organization of information about construction

work. Framework for object-oriented information [21]

ISO 16739:2005

Revised in 2013

Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for data sharing in the construction

and facility management industries [22]

ISO 12006-2:2001

Revised in 2015

Building construction. Organization of information about construction

work. Framework for classification of information [23]

Figure 2: The ISO/TS 12911:2011 framework for BIM guidance [18].

A large number of BIM guides have been developed for different purposes. Table 4

provides an overview of BIM guidance, when and in which country they are developed. This

list is not comprehensive but illustrates both a long history and that some countries have more

guidelines for different purposes. Guidelines also have to be updated due to various

experiences and to keep up with the users’ development or maturity, as well as the increasing

complexity of the projects.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 7

ISO standard Title

ISO 15686-4:2014 Building construction. Service life planning. Service life planning using

building information modelling [15]

ISO 16354:2013 Guidelines for knowledge libraries and object libraries [16]

ISO 29481-2:2012 Building information models. Information delivery manual.

Interaction framework [17]

ISO/TS 12911:2012 Framework for building information modelling guidance [18]

ISO 29481-1:2010

Revised in 2016

Building information modelling. Information delivery manual.

Methodology and format [19]

ISO 22263:2008 Organization of information about construction works. Framework for

management of project information [20]

ISO 12006-3:2007 Building construction. Organization of information about construction

work. Framework for object-oriented information [21]

ISO 16739:2005

Revised in 2013

Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for data sharing in the construction

and facility management industries [22]

ISO 12006-2:2001

Revised in 2015

Building construction. Organization of information about construction

work. Framework for classification of information [23]

Figure 2: The ISO/TS 12911:2011 framework for BIM guidance [18].

A large number of BIM guides have been developed for different purposes. Table 4

provides an overview of BIM guidance, when and in which country they are developed. This

list is not comprehensive but illustrates both a long history and that some countries have more

guidelines for different purposes. Guidelines also have to be updated due to various

experiences and to keep up with the users’ development or maturity, as well as the increasing

complexity of the projects.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 7

Table 4: Overview of BIM guidance, when and in which country they are developed.

Year Country BIM standards/guidelines

2017 Norway

Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v2.0 [24]

Under Development, will be a Requirement Database with Digital Functions

for Validation of BIM file in IFC 4.0 Format

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 06 v1.0

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 07 v1.0

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series v1.0

2015 USA NIBS – NBIMS v3.0

2014 German German BIM Guide

2013 UK AEC – UK BIM Protocol

2013 USA AIA – Document E201 – 2013 Project Digital Data Protocol Form

2013 USA AIA – Document E203 – 2013 BIM and Digital Data Exhibit

2013 USA AIA – Document G302, Project Digital Data Protocol

2013 USA AIA – Guide; Instructions and Commentary

2013 Norway BoligBIM – Norwegian Home Builder Association

2013 USA PSU – The Use of BIM

2012 USA PSU – EBM Planning Guide for Facility Owners v1.02

2012 Finland Senate – Finland Common BIM Requirement COBIM

2012 Singapore Singapore BIM Guide

2012 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.2

2011 USA Georgia Tech BIM Req. & Guidelines for Arch., Engineers and Contractors

2011 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 08 v1.0

2011 USA GSA – BIM Guide the OE v1.0

2011 Australia NATSPEC National BIM Guide, Australia, v1.0

2011 USA PSU – BIM PEP Guide v2.1

2010 USA PSU – BIM Execution Planning Guide v.2.0

2010 USA PSU – BIM PEP Guide v2.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 03 v1.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 04 v1.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 05 v1.0

2009 USA PSU – Penn State Uni. BIM PEP Guide 1.0

2009 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.1

2008 USA AGC – The Contractors Guide to BIM

2008 USA AIA – Document E.202-2008 BIM protocol exhibit

2008 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.0

2007 USA AIA – Document E201 – 2007 Data Protocol Exhibit

2007 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 01 v1.0

2007 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 02 v1.0

2007 USA NIBS – NBIMS v1.0

2007 USA NIST – General Buildings Information Handover Guide

2007 Finland Senate – Finland BIM Requirements

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

8 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

Year Country BIM standards/guidelines

2017 Norway

Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v2.0 [24]

Under Development, will be a Requirement Database with Digital Functions

for Validation of BIM file in IFC 4.0 Format

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 06 v1.0

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 07 v1.0

2015 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series v1.0

2015 USA NIBS – NBIMS v3.0

2014 German German BIM Guide

2013 UK AEC – UK BIM Protocol

2013 USA AIA – Document E201 – 2013 Project Digital Data Protocol Form

2013 USA AIA – Document E203 – 2013 BIM and Digital Data Exhibit

2013 USA AIA – Document G302, Project Digital Data Protocol

2013 USA AIA – Guide; Instructions and Commentary

2013 Norway BoligBIM – Norwegian Home Builder Association

2013 USA PSU – The Use of BIM

2012 USA PSU – EBM Planning Guide for Facility Owners v1.02

2012 Finland Senate – Finland Common BIM Requirement COBIM

2012 Singapore Singapore BIM Guide

2012 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.2

2011 USA Georgia Tech BIM Req. & Guidelines for Arch., Engineers and Contractors

2011 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 08 v1.0

2011 USA GSA – BIM Guide the OE v1.0

2011 Australia NATSPEC National BIM Guide, Australia, v1.0

2011 USA PSU – BIM PEP Guide v2.1

2010 USA PSU – BIM Execution Planning Guide v.2.0

2010 USA PSU – BIM PEP Guide v2.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 03 v1.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 04 v1.0

2009 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 05 v1.0

2009 USA PSU – Penn State Uni. BIM PEP Guide 1.0

2009 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.1

2008 USA AGC – The Contractors Guide to BIM

2008 USA AIA – Document E.202-2008 BIM protocol exhibit

2008 Norway Statsbygg – Norwegian Property Agency, v1.0

2007 USA AIA – Document E201 – 2007 Data Protocol Exhibit

2007 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 01 v1.0

2007 USA GSA – BIM Guide Series 02 v1.0

2007 USA NIBS – NBIMS v1.0

2007 USA NIST – General Buildings Information Handover Guide

2007 Finland Senate – Finland BIM Requirements

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

8 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Please note that BIM guidance is presented as reports in pdf-format. The work has to be

done manually to validate whether or not specified requirements are fulfilled. This is a time-

consuming process that requires a high level of competence with BIM. Statsbygg, the

Norwegian property agency, is in its final phase of developing its new generation of BIM

guidance. This guidance will be a requirement database with digital functions for the

validation of BIM files in IFC 4.0 format [24]. This is a significant step toward enabling

digital-supported working processes.

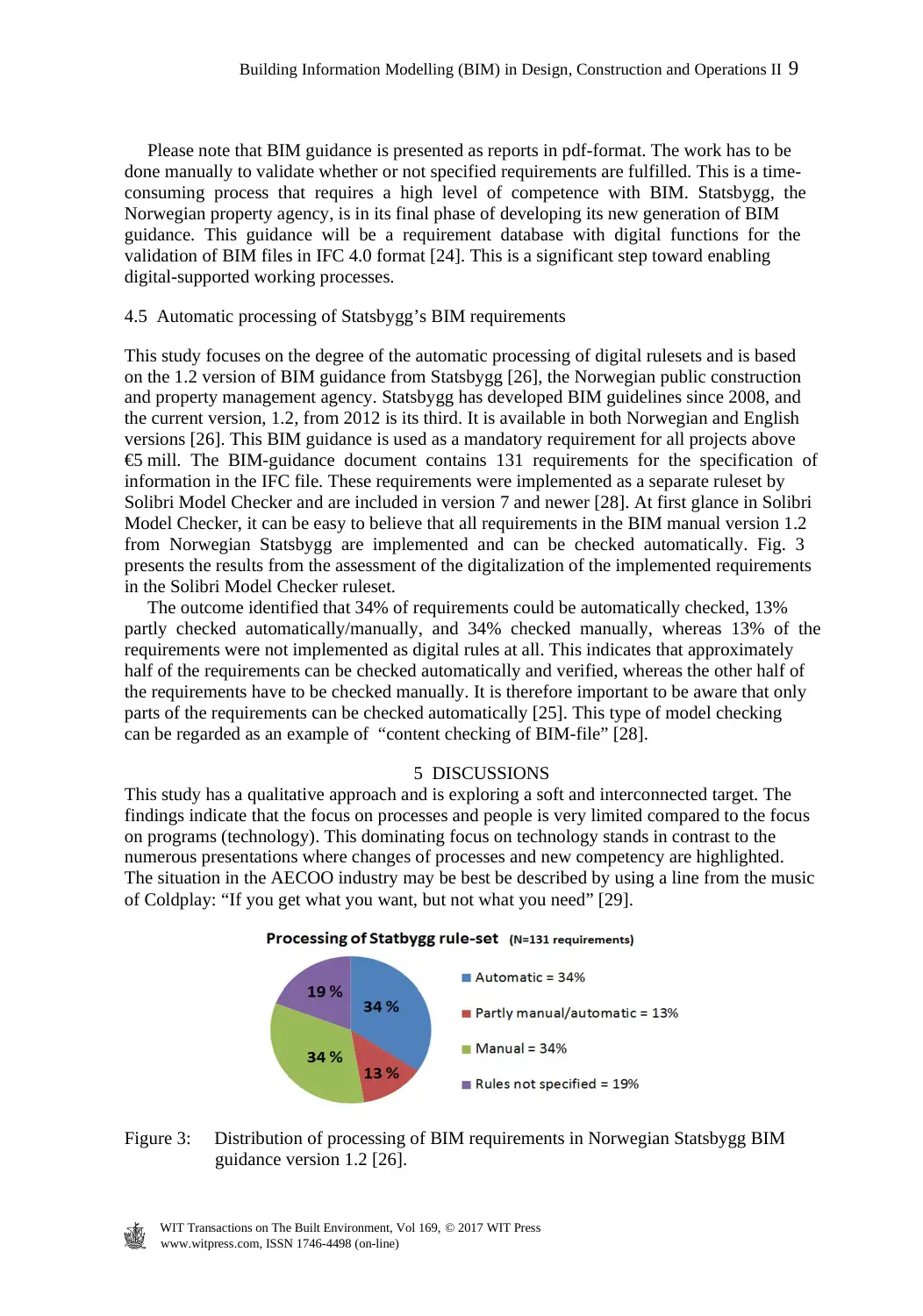

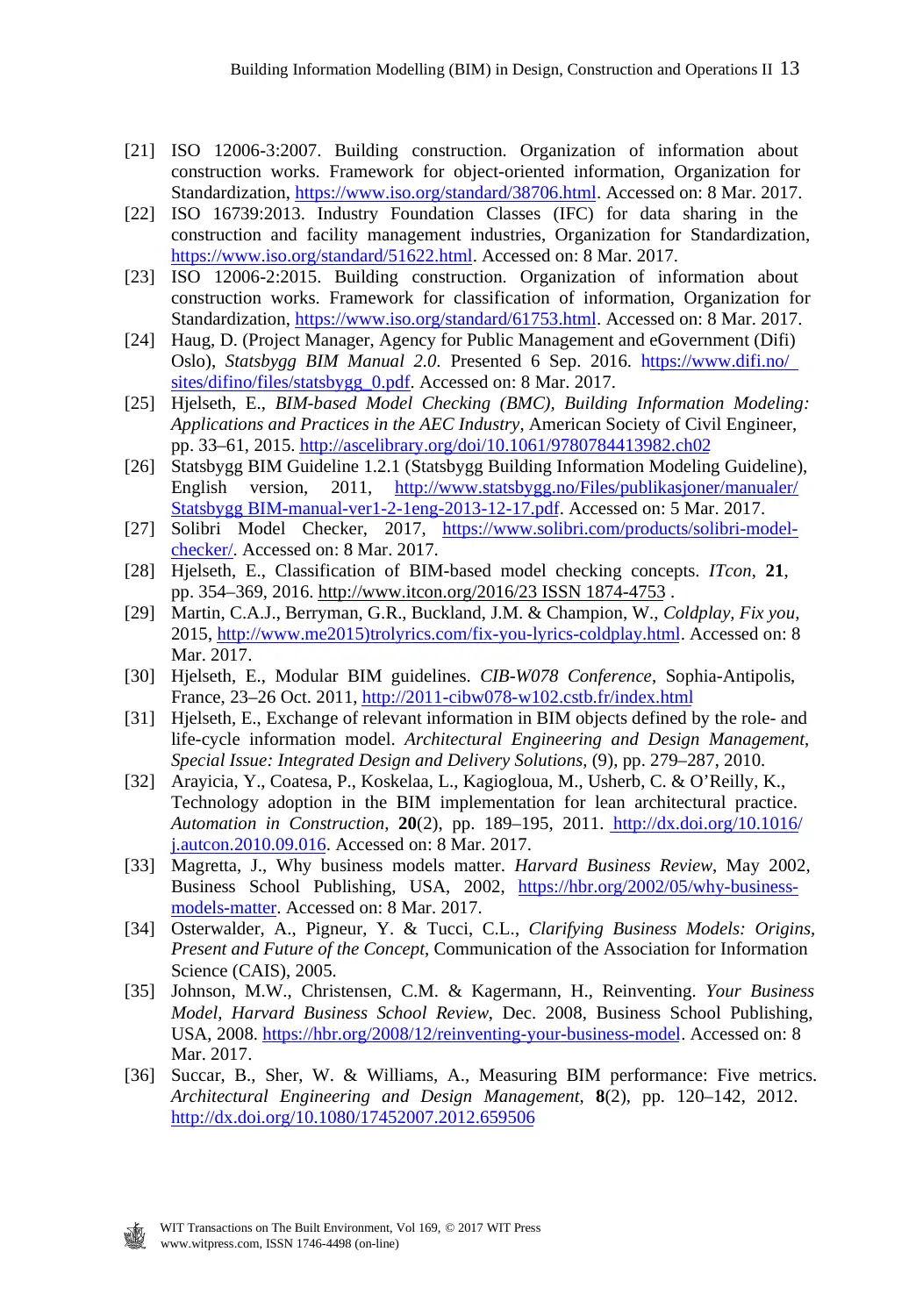

4.5 Automatic processing of Statsbygg’s BIM requirements

This study focuses on the degree of the automatic processing of digital rulesets and is based

on the 1.2 version of BIM guidance from Statsbygg [26], the Norwegian public construction

and property management agency. Statsbygg has developed BIM guidelines since 2008, and

the current version, 1.2, from 2012 is its third. It is available in both Norwegian and English

versions [26]. This BIM guidance is used as a mandatory requirement for all projects above

€5 mill. The BIM-guidance document contains 131 requirements for the specification of

information in the IFC file. These requirements were implemented as a separate ruleset by

Solibri Model Checker and are included in version 7 and newer [28]. At first glance in Solibri

Model Checker, it can be easy to believe that all requirements in the BIM manual version 1.2

from Norwegian Statsbygg are implemented and can be checked automatically. Fig. 3

presents the results from the assessment of the digitalization of the implemented requirements

in the Solibri Model Checker ruleset.

The outcome identified that 34% of requirements could be automatically checked, 13%

partly checked automatically/manually, and 34% checked manually, whereas 13% of the

requirements were not implemented as digital rules at all. This indicates that approximately

half of the requirements can be checked automatically and verified, whereas the other half of

the requirements have to be checked manually. It is therefore important to be aware that only

parts of the requirements can be checked automatically [25]. This type of model checking

can be regarded as an example of “content checking of BIM-file” [28].

5 DISCUSSIONS

This study has a qualitative approach and is exploring a soft and interconnected target. The

findings indicate that the focus on processes and people is very limited compared to the focus

on programs (technology). This dominating focus on technology stands in contrast to the

numerous presentations where changes of processes and new competency are highlighted.

The situation in the AECOO industry may be best be described by using a line from the music

of Coldplay: “If you get what you want, but not what you need” [29].

Figure 3: Distribution of processing of BIM requirements in Norwegian Statsbygg BIM

guidance version 1.2 [26].

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 9

done manually to validate whether or not specified requirements are fulfilled. This is a time-

consuming process that requires a high level of competence with BIM. Statsbygg, the

Norwegian property agency, is in its final phase of developing its new generation of BIM

guidance. This guidance will be a requirement database with digital functions for the

validation of BIM files in IFC 4.0 format [24]. This is a significant step toward enabling

digital-supported working processes.

4.5 Automatic processing of Statsbygg’s BIM requirements

This study focuses on the degree of the automatic processing of digital rulesets and is based

on the 1.2 version of BIM guidance from Statsbygg [26], the Norwegian public construction

and property management agency. Statsbygg has developed BIM guidelines since 2008, and

the current version, 1.2, from 2012 is its third. It is available in both Norwegian and English

versions [26]. This BIM guidance is used as a mandatory requirement for all projects above

€5 mill. The BIM-guidance document contains 131 requirements for the specification of

information in the IFC file. These requirements were implemented as a separate ruleset by

Solibri Model Checker and are included in version 7 and newer [28]. At first glance in Solibri

Model Checker, it can be easy to believe that all requirements in the BIM manual version 1.2

from Norwegian Statsbygg are implemented and can be checked automatically. Fig. 3

presents the results from the assessment of the digitalization of the implemented requirements

in the Solibri Model Checker ruleset.

The outcome identified that 34% of requirements could be automatically checked, 13%

partly checked automatically/manually, and 34% checked manually, whereas 13% of the

requirements were not implemented as digital rules at all. This indicates that approximately

half of the requirements can be checked automatically and verified, whereas the other half of

the requirements have to be checked manually. It is therefore important to be aware that only

parts of the requirements can be checked automatically [25]. This type of model checking

can be regarded as an example of “content checking of BIM-file” [28].

5 DISCUSSIONS

This study has a qualitative approach and is exploring a soft and interconnected target. The

findings indicate that the focus on processes and people is very limited compared to the focus

on programs (technology). This dominating focus on technology stands in contrast to the

numerous presentations where changes of processes and new competency are highlighted.

The situation in the AECOO industry may be best be described by using a line from the music

of Coldplay: “If you get what you want, but not what you need” [29].

Figure 3: Distribution of processing of BIM requirements in Norwegian Statsbygg BIM

guidance version 1.2 [26].

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Even if BIM guidance is a comprehensive document, all of the documents build on simple

modules connecting information to a task [30]. This can be further developed by connecting

exchanged or relevant information to both the role and life cycle in the project [31].

According to studies by Arayicia et al. [32], construction companies are facing barriers

and challenges with BIM adoption. There is no clear guidance or best practice study from

which they can learn and build up their capacity for BIM use to increase productivity,

efficiency, and quality; to attain competitive advantages in the global market; and to achieve

their targets in environmental sustainability [32].

There is also a limited focus on development of business models compared to solving the

technical aspects of BIM. Business models are fundamental to realizing the latent value of

new ideas or technologies. Magretta [33] described business models as “the story about how

an enterprise works,” defining who the target customers are, how the business makes money,

and what the customer values. More recent definitions include a componential perspective,

for example, the canvas model by Osterwalder et al. [34]. An article in Harvard Business

School illustrates the importance of the development of new business models by stating: “A

new model is often needed, however, to leverage a new technology is generally required

when the opportunity addresses an entirely new group of customers; and is surely in order

when an established company needs to fend off a successful disruptor” [35]. The

development of information models should therefore be supported by the development of

business models.

There is a need for monitoring the implementation of processes. The increased

use of maturity assessment criteria will in this respect be very useful. Works by Succar et

al. [36]–[38] can be used as foundations. If further studies on real implementation do not

indicate real improvements, the implementation strategy for the AECOO industry should

be challenged. Skills and plans for implementation of processes are what are missing.

Learning for other project-oriented industries, such as oil and gas, is highlighted as an

approach for the increased implementation of BIM [39]. A general experience is that

technology is just an enabler, whereas new business models or opportunities, public

regulations and standards, and a shift in market trends and the customer’s preference (e.g.

sustainability/green buildings) act as the real drivers of change.

Industry 4.0 will have a significant impact on the engineering and construction industry

in the next five years [40], challenging both technology and business models.

In this respect, the use of IDDS framework may prove invaluable [10]. IDDS is focused on

addressing complex and transformative development challenges through integrated solutions

that incorporate technology and innovation, the cross-practice delivery of solutions, and the

global sharing of knowledge and good practices.

There is a need for addressing implementation up to national or international strategies.

In this respect can the new BIM-related CEN standards under development by technical

committee TC442 – Building Information Modelling (BIM) [8] have a significant impact in

Europe. Likewise, will the implementation of the BIM-related standards from

ISO/TC59/SC13 – Organization of information about construction works [9] have an

international impact.

The AECOO industry has an “engineering” culture with a focus on quantitative factors

that can be calculated. When it comes to qualitative factors, the industry has reduced its

awareness. Even if some people agrees about importance of soft skills there is generally less

awareness about it compared to hard skills in use and development of BIM.

A joint understanding and the use of indicators for BIM processes are necessary to make

measurable deliverables similar to other project-related deliverables. This will transform the

process from having soft targets to having hard, measurable ones.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

10 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

modules connecting information to a task [30]. This can be further developed by connecting

exchanged or relevant information to both the role and life cycle in the project [31].

According to studies by Arayicia et al. [32], construction companies are facing barriers

and challenges with BIM adoption. There is no clear guidance or best practice study from

which they can learn and build up their capacity for BIM use to increase productivity,

efficiency, and quality; to attain competitive advantages in the global market; and to achieve

their targets in environmental sustainability [32].

There is also a limited focus on development of business models compared to solving the

technical aspects of BIM. Business models are fundamental to realizing the latent value of

new ideas or technologies. Magretta [33] described business models as “the story about how

an enterprise works,” defining who the target customers are, how the business makes money,

and what the customer values. More recent definitions include a componential perspective,

for example, the canvas model by Osterwalder et al. [34]. An article in Harvard Business

School illustrates the importance of the development of new business models by stating: “A

new model is often needed, however, to leverage a new technology is generally required

when the opportunity addresses an entirely new group of customers; and is surely in order

when an established company needs to fend off a successful disruptor” [35]. The

development of information models should therefore be supported by the development of

business models.

There is a need for monitoring the implementation of processes. The increased

use of maturity assessment criteria will in this respect be very useful. Works by Succar et

al. [36]–[38] can be used as foundations. If further studies on real implementation do not

indicate real improvements, the implementation strategy for the AECOO industry should

be challenged. Skills and plans for implementation of processes are what are missing.

Learning for other project-oriented industries, such as oil and gas, is highlighted as an

approach for the increased implementation of BIM [39]. A general experience is that

technology is just an enabler, whereas new business models or opportunities, public

regulations and standards, and a shift in market trends and the customer’s preference (e.g.

sustainability/green buildings) act as the real drivers of change.

Industry 4.0 will have a significant impact on the engineering and construction industry

in the next five years [40], challenging both technology and business models.

In this respect, the use of IDDS framework may prove invaluable [10]. IDDS is focused on

addressing complex and transformative development challenges through integrated solutions

that incorporate technology and innovation, the cross-practice delivery of solutions, and the

global sharing of knowledge and good practices.

There is a need for addressing implementation up to national or international strategies.

In this respect can the new BIM-related CEN standards under development by technical

committee TC442 – Building Information Modelling (BIM) [8] have a significant impact in

Europe. Likewise, will the implementation of the BIM-related standards from

ISO/TC59/SC13 – Organization of information about construction works [9] have an

international impact.

The AECOO industry has an “engineering” culture with a focus on quantitative factors

that can be calculated. When it comes to qualitative factors, the industry has reduced its

awareness. Even if some people agrees about importance of soft skills there is generally less

awareness about it compared to hard skills in use and development of BIM.

A joint understanding and the use of indicators for BIM processes are necessary to make

measurable deliverables similar to other project-related deliverables. This will transform the

process from having soft targets to having hard, measurable ones.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

10 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

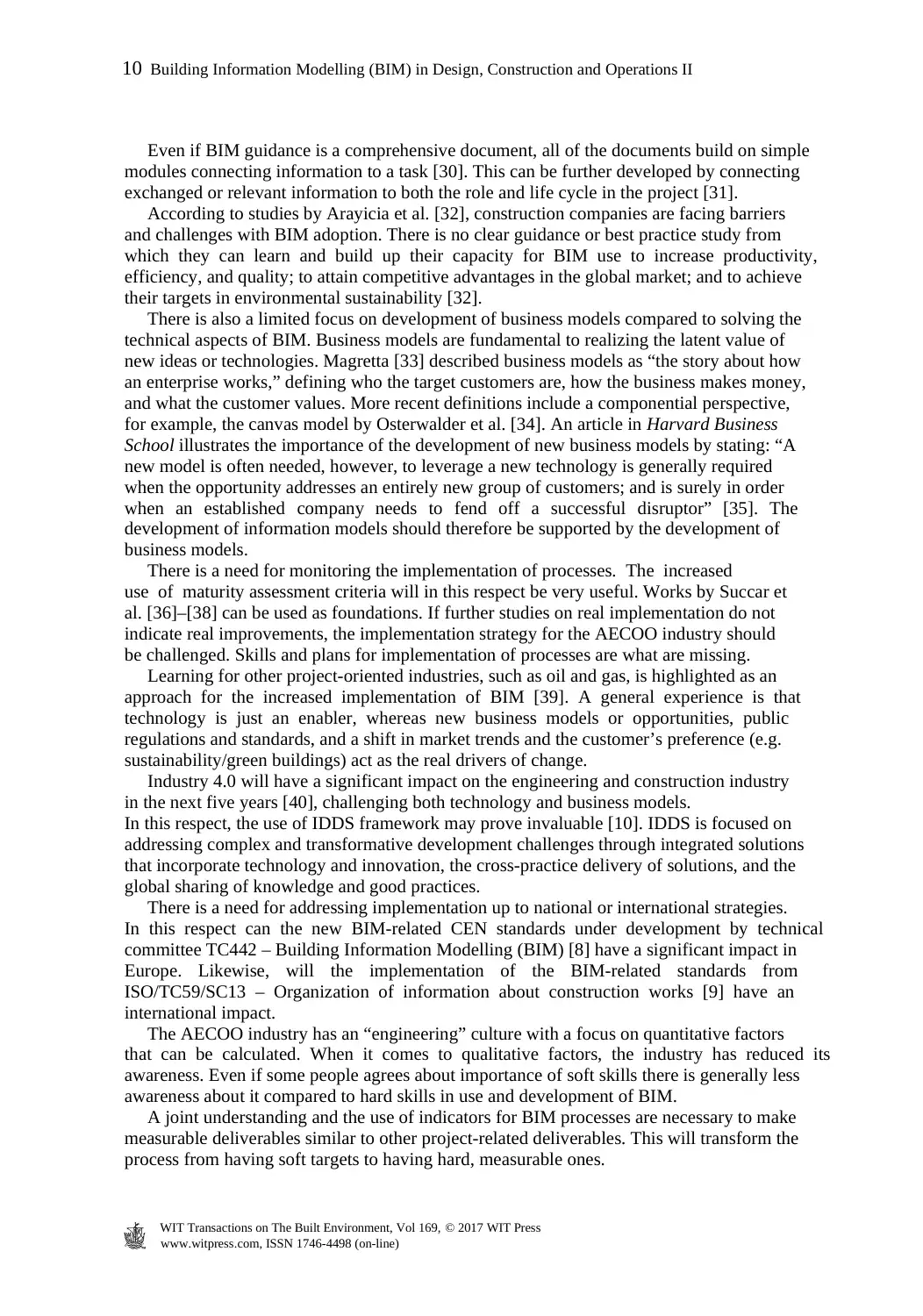

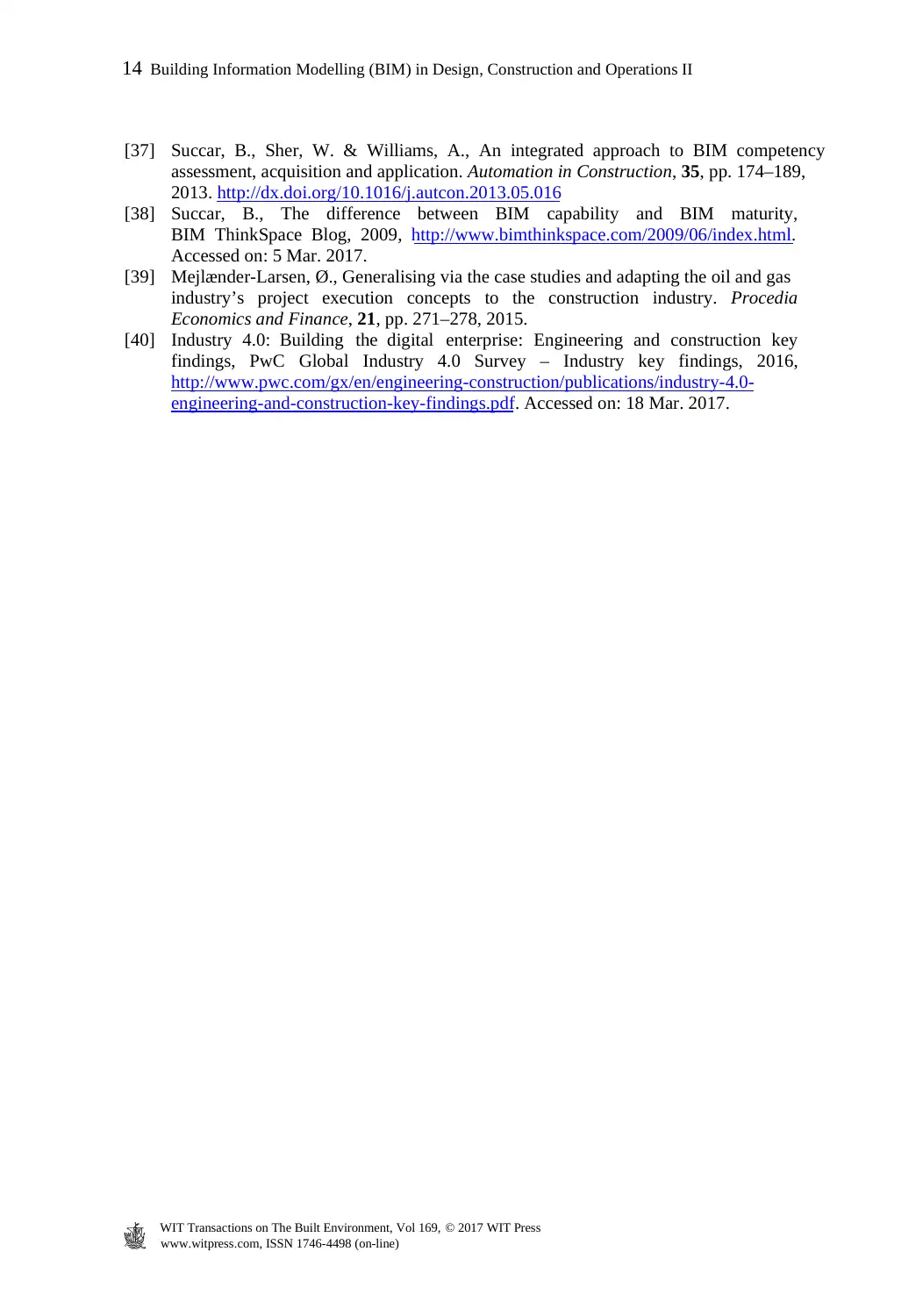

Figure 4: The priority of the program-process-person perspectives.

6 SUMMARY

BIM is a widely used term and abbreviation. There exists no joint understanding of BIM in

the AECOO industry. The use of a term and the understanding of the term can be two

different things. This study indicates that BIM is mainly understood as the use of software

programs. This is independent of the use of descriptions such as building information model,

building information modelling, or building information management. The dominating focus

on technology stands in contrast to the numerous presentations where changes of processes

and new competency are highlighted. A focus on the development of software and the

exchange of files dominates procedures related to the use of BIM guidance and standards.

Formal requirements for attaining competency have not been observed as elements in

implementing BIM in projects or organizations. Fig. 4 illustrates the priority of the program-

process-person perspectives. BIM is in general understood as the use of software programs,

where the advanced use of BIM requires advanced software skills.

REFERENCES

[1] McGraw-Hill Construction, Measuring the impact of BIM on complex buildings

SmartMarket report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2016, http://analyticsstore.

construction.com/smartmarket-reports/ComplexBIM.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[2] McGraw-Hill Construction, Business value of BIM for construction in major global

markets SmartMarket report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2014.

http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-reports/GlobalBIMSMR14.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[3] McGraw-Hill Construction, The business value of BIM for owners Smartmarket

report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2014, http://analyticsstore.construction.com/

smartmarket-reports/BIMforOwnersSMR.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[4] McGraw-Hill Construction, SmartMarket report: Green BIM, how building

information modeling is contributing to green design and construction, 2010, Dodge

Data & Analytics, USA, http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-

reports/smartmarket-report-green-bim-2010-how-building-information-modeling-is-

contributing-to-green-design-and-construction.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[5] McGraw-Hill Construction, Smartmarket report: The business value of BIM in

Europe, getting building information modeling to the bottom line in the United

Kingdom, France and Germany, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2010.

http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-reports/smartmarket-report-the-

People

Collaborating

Way of working

Management

Processes

Standards

Guidelines

Modelling

B I M Programs

Technology

Model

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 11

6 SUMMARY

BIM is a widely used term and abbreviation. There exists no joint understanding of BIM in

the AECOO industry. The use of a term and the understanding of the term can be two

different things. This study indicates that BIM is mainly understood as the use of software

programs. This is independent of the use of descriptions such as building information model,

building information modelling, or building information management. The dominating focus

on technology stands in contrast to the numerous presentations where changes of processes

and new competency are highlighted. A focus on the development of software and the

exchange of files dominates procedures related to the use of BIM guidance and standards.

Formal requirements for attaining competency have not been observed as elements in

implementing BIM in projects or organizations. Fig. 4 illustrates the priority of the program-

process-person perspectives. BIM is in general understood as the use of software programs,

where the advanced use of BIM requires advanced software skills.

REFERENCES

[1] McGraw-Hill Construction, Measuring the impact of BIM on complex buildings

SmartMarket report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2016, http://analyticsstore.

construction.com/smartmarket-reports/ComplexBIM.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[2] McGraw-Hill Construction, Business value of BIM for construction in major global

markets SmartMarket report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2014.

http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-reports/GlobalBIMSMR14.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[3] McGraw-Hill Construction, The business value of BIM for owners Smartmarket

report, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2014, http://analyticsstore.construction.com/

smartmarket-reports/BIMforOwnersSMR.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[4] McGraw-Hill Construction, SmartMarket report: Green BIM, how building

information modeling is contributing to green design and construction, 2010, Dodge

Data & Analytics, USA, http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-

reports/smartmarket-report-green-bim-2010-how-building-information-modeling-is-

contributing-to-green-design-and-construction.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[5] McGraw-Hill Construction, Smartmarket report: The business value of BIM in

Europe, getting building information modeling to the bottom line in the United

Kingdom, France and Germany, Dodge Data & Analytics, USA, 2010.

http://analyticsstore.construction.com/smartmarket-reports/smartmarket-report-the-

People

Collaborating

Way of working

Management

Processes

Standards

Guidelines

Modelling

B I M Programs

Technology

Model

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

business-value-of-bim-in-europe-2010-getting-building-information-modeling-to-

the-bottom-line-in-the-united-kingdom-france-and-germany.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[6] Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R. & Liston, K., BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building

Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors,

John Wiley & Sons, 2nd ed., 640 pp., 2011.

[7] Mordue, S., Swaddle, P. & Philp, D., BIM for Dummies, Building Information

Modeling For Dummies, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 349, 2015.

[8] ISO/TC59/SC13. Organization of information about construction works, International

Organization for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/committee/49180.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[9] CEN/TC 442. Building Information Modelling (BIM), European Committee for

Standardization (CEN), https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/f?p=204:7:0::::FSP_ ORG

_ID:1991542&cs=16AAC0F2C377A541DCA571910561FC17F. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[10] Owen, R. Research Roadmap Report CIB Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions

(IDDS), CIB Publication 370, International Council for Building, 2013,

http://site.cibworld.nl/dl/publications/pub_370.pdf. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[11] International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction,

International Council for Building, Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions (IDDS),

2015, http://www.cibworld.nl/site/programme/priority_themes/integrated_design_

and_delivery_solutions.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[12] Bostrom, R.P. & Heinen, J.S., MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical

perspective. MIS Quarterly, 1(3), pp. 17–32, 1977. http://misq.org/cat-articles/mis-

problems-and-failiures-a-socio-technical-perspective-part-i-the-causes.html

[13] Skibniewski, M.J. (Editor-in-Chief), Automation in Construction, An International

Research Journal, Elsevier B.V., https://www.journals.elsevier.com/ automation-in-

construction/. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[14] buildingSMART Norway, bsN Newsletter, https://buildingsmart.no/nyhetsbrev/.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[15] ISO 15686-4:2014. Building Construction. Service Life Planning. Service Life

Planning using Building Information Modelling, International Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/59150.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[16] ISO 16354:2013. Guidelines for knowledge libraries and object libraries, Organization

for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/56434.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar.

2017.

[17] ISO 29481-2:2012. Building information models. Information delivery manual. Part

2, Interaction framework, https://www.iso.org/standard/55691.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[18] ISO/TS 12911:2012. Framework for building information modelling (BIM) guidance,

Organization for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/52155.html. Accessed

on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[19] ISO 29481-1:2016. Building information modelling. Information delivery manual –

Part 1: Methodology and format, Organization for Standardization,

https://www.iso.org/standard/60553.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[20] ISO 22263:2008. Organization of information about construction works. Framework

for management of project information, https://www.iso.org/standard/40835.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

12 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

the-bottom-line-in-the-united-kingdom-france-and-germany.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[6] Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R. & Liston, K., BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building

Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors,

John Wiley & Sons, 2nd ed., 640 pp., 2011.

[7] Mordue, S., Swaddle, P. & Philp, D., BIM for Dummies, Building Information

Modeling For Dummies, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 349, 2015.

[8] ISO/TC59/SC13. Organization of information about construction works, International

Organization for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/committee/49180.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[9] CEN/TC 442. Building Information Modelling (BIM), European Committee for

Standardization (CEN), https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/f?p=204:7:0::::FSP_ ORG

_ID:1991542&cs=16AAC0F2C377A541DCA571910561FC17F. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[10] Owen, R. Research Roadmap Report CIB Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions

(IDDS), CIB Publication 370, International Council for Building, 2013,

http://site.cibworld.nl/dl/publications/pub_370.pdf. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[11] International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction,

International Council for Building, Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions (IDDS),

2015, http://www.cibworld.nl/site/programme/priority_themes/integrated_design_

and_delivery_solutions.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[12] Bostrom, R.P. & Heinen, J.S., MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical

perspective. MIS Quarterly, 1(3), pp. 17–32, 1977. http://misq.org/cat-articles/mis-

problems-and-failiures-a-socio-technical-perspective-part-i-the-causes.html

[13] Skibniewski, M.J. (Editor-in-Chief), Automation in Construction, An International

Research Journal, Elsevier B.V., https://www.journals.elsevier.com/ automation-in-

construction/. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[14] buildingSMART Norway, bsN Newsletter, https://buildingsmart.no/nyhetsbrev/.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[15] ISO 15686-4:2014. Building Construction. Service Life Planning. Service Life

Planning using Building Information Modelling, International Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/59150.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[16] ISO 16354:2013. Guidelines for knowledge libraries and object libraries, Organization

for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/56434.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar.

2017.

[17] ISO 29481-2:2012. Building information models. Information delivery manual. Part

2, Interaction framework, https://www.iso.org/standard/55691.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[18] ISO/TS 12911:2012. Framework for building information modelling (BIM) guidance,

Organization for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/52155.html. Accessed

on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[19] ISO 29481-1:2016. Building information modelling. Information delivery manual –

Part 1: Methodology and format, Organization for Standardization,

https://www.iso.org/standard/60553.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[20] ISO 22263:2008. Organization of information about construction works. Framework

for management of project information, https://www.iso.org/standard/40835.html.

Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

12 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[21] ISO 12006-3:2007. Building construction. Organization of information about

construction works. Framework for object-oriented information, Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/38706.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[22] ISO 16739:2013. Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for data sharing in the

construction and facility management industries, Organization for Standardization,

https://www.iso.org/standard/51622.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[23] ISO 12006-2:2015. Building construction. Organization of information about

construction works. Framework for classification of information, Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/61753.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[24] Haug, D. (Project Manager, Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi)

Oslo), Statsbygg BIM Manual 2.0. Presented 6 Sep. 2016. https://www.difi.no/

sites/difino/files/statsbygg_0.pdf. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[25] Hjelseth, E., BIM-based Model Checking (BMC), Building Information Modeling:

Applications and Practices in the AEC Industry, American Society of Civil Engineer,

pp. 33–61, 2015. http://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/9780784413982.ch02

[26] Statsbygg BIM Guideline 1.2.1 (Statsbygg Building Information Modeling Guideline),

English version, 2011, http://www.statsbygg.no/Files/publikasjoner/manualer/

Statsbygg BIM-manual-ver1-2-1eng-2013-12-17.pdf. Accessed on: 5 Mar. 2017.

[27] Solibri Model Checker, 2017, https://www.solibri.com/products/solibri-model-

checker/. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[28] Hjelseth, E., Classification of BIM-based model checking concepts. ITcon, 21,

pp. 354–369, 2016. http://www.itcon.org/2016/23 ISSN 1874-4753 .

[29] Martin, C.A.J., Berryman, G.R., Buckland, J.M. & Champion, W., Coldplay, Fix you,

2015, http://www.me2015)trolyrics.com/fix-you-lyrics-coldplay.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[30] Hjelseth, E., Modular BIM guidelines. CIB-W078 Conference, Sophia-Antipolis,

France, 23–26 Oct. 2011, http://2011-cibw078-w102.cstb.fr/index.html

[31] Hjelseth, E., Exchange of relevant information in BIM objects defined by the role- and

life-cycle information model. Architectural Engineering and Design Management,

Special Issue: Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions, (9), pp. 279–287, 2010.

[32] Arayicia, Y., Coatesa, P., Koskelaa, L., Kagiogloua, M., Usherb, C. & O’Reilly, K.,

Technology adoption in the BIM implementation for lean architectural practice.

Automation in Construction, 20(2), pp. 189–195, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.autcon.2010.09.016. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[33] Magretta, J., Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, May 2002,

Business School Publishing, USA, 2002, https://hbr.org/2002/05/why-business-

models-matter. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[34] Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. & Tucci, C.L., Clarifying Business Models: Origins,

Present and Future of the Concept, Communication of the Association for Information

Science (CAIS), 2005.

[35] Johnson, M.W., Christensen, C.M. & Kagermann, H., Reinventing. Your Business

Model, Harvard Business School Review, Dec. 2008, Business School Publishing,

USA, 2008. https://hbr.org/2008/12/reinventing-your-business-model. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[36] Succar, B., Sher, W. & Williams, A., Measuring BIM performance: Five metrics.

Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 8(2), pp. 120–142, 2012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2012.659506

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 13

construction works. Framework for object-oriented information, Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/38706.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[22] ISO 16739:2013. Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for data sharing in the

construction and facility management industries, Organization for Standardization,

https://www.iso.org/standard/51622.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[23] ISO 12006-2:2015. Building construction. Organization of information about

construction works. Framework for classification of information, Organization for

Standardization, https://www.iso.org/standard/61753.html. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[24] Haug, D. (Project Manager, Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi)

Oslo), Statsbygg BIM Manual 2.0. Presented 6 Sep. 2016. https://www.difi.no/

sites/difino/files/statsbygg_0.pdf. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[25] Hjelseth, E., BIM-based Model Checking (BMC), Building Information Modeling:

Applications and Practices in the AEC Industry, American Society of Civil Engineer,

pp. 33–61, 2015. http://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/9780784413982.ch02

[26] Statsbygg BIM Guideline 1.2.1 (Statsbygg Building Information Modeling Guideline),

English version, 2011, http://www.statsbygg.no/Files/publikasjoner/manualer/

Statsbygg BIM-manual-ver1-2-1eng-2013-12-17.pdf. Accessed on: 5 Mar. 2017.

[27] Solibri Model Checker, 2017, https://www.solibri.com/products/solibri-model-

checker/. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[28] Hjelseth, E., Classification of BIM-based model checking concepts. ITcon, 21,

pp. 354–369, 2016. http://www.itcon.org/2016/23 ISSN 1874-4753 .

[29] Martin, C.A.J., Berryman, G.R., Buckland, J.M. & Champion, W., Coldplay, Fix you,

2015, http://www.me2015)trolyrics.com/fix-you-lyrics-coldplay.html. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[30] Hjelseth, E., Modular BIM guidelines. CIB-W078 Conference, Sophia-Antipolis,

France, 23–26 Oct. 2011, http://2011-cibw078-w102.cstb.fr/index.html

[31] Hjelseth, E., Exchange of relevant information in BIM objects defined by the role- and

life-cycle information model. Architectural Engineering and Design Management,

Special Issue: Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions, (9), pp. 279–287, 2010.

[32] Arayicia, Y., Coatesa, P., Koskelaa, L., Kagiogloua, M., Usherb, C. & O’Reilly, K.,

Technology adoption in the BIM implementation for lean architectural practice.

Automation in Construction, 20(2), pp. 189–195, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.autcon.2010.09.016. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[33] Magretta, J., Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, May 2002,

Business School Publishing, USA, 2002, https://hbr.org/2002/05/why-business-

models-matter. Accessed on: 8 Mar. 2017.

[34] Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. & Tucci, C.L., Clarifying Business Models: Origins,

Present and Future of the Concept, Communication of the Association for Information

Science (CAIS), 2005.

[35] Johnson, M.W., Christensen, C.M. & Kagermann, H., Reinventing. Your Business

Model, Harvard Business School Review, Dec. 2008, Business School Publishing,

USA, 2008. https://hbr.org/2008/12/reinventing-your-business-model. Accessed on: 8

Mar. 2017.

[36] Succar, B., Sher, W. & Williams, A., Measuring BIM performance: Five metrics.

Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 8(2), pp. 120–142, 2012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2012.659506

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II 13

[37] Succar, B., Sher, W. & Williams, A., An integrated approach to BIM competency

assessment, acquisition and application. Automation in Construction, 35, pp. 174–189,

2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2013.05.016

[38] Succar, B., The difference between BIM capability and BIM maturity,

BIM ThinkSpace Blog, 2009, http://www.bimthinkspace.com/2009/06/index.html.

Accessed on: 5 Mar. 2017.

[39] Mejlænder-Larsen, Ø., Generalising via the case studies and adapting the oil and gas

industry’s project execution concepts to the construction industry. Procedia

Economics and Finance, 21, pp. 271–278, 2015.

[40] Industry 4.0: Building the digital enterprise: Engineering and construction key

findings, PwC Global Industry 4.0 Survey – Industry key findings, 2016,

http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/engineering-construction/publications/industry-4.0-

engineering-and-construction-key-findings.pdf. Accessed on: 18 Mar. 2017.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

14 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

assessment, acquisition and application. Automation in Construction, 35, pp. 174–189,

2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2013.05.016

[38] Succar, B., The difference between BIM capability and BIM maturity,

BIM ThinkSpace Blog, 2009, http://www.bimthinkspace.com/2009/06/index.html.

Accessed on: 5 Mar. 2017.

[39] Mejlænder-Larsen, Ø., Generalising via the case studies and adapting the oil and gas

industry’s project execution concepts to the construction industry. Procedia

Economics and Finance, 21, pp. 271–278, 2015.

[40] Industry 4.0: Building the digital enterprise: Engineering and construction key

findings, PwC Global Industry 4.0 Survey – Industry key findings, 2016,

http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/engineering-construction/publications/industry-4.0-

engineering-and-construction-key-findings.pdf. Accessed on: 18 Mar. 2017.

www.witpress.com, ISSN 1746-4498 (on-line)

WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 169, © 2017 WIT Press

14 Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations II

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.