Burnout Prevalence and Determinants in Emergency Nurses: Review

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/17

|13

|11465

|250

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review, published in the International Journal of Nursing Studies, systematically examines the prevalence and determinants of burnout in emergency nurses. The review analyzed seventeen studies published between 1989 and 2014, revealing that an average of 26% of emergency nurses experience burnout. The study identifies both individual factors, such as demographic variables, personality characteristics, and coping strategies, and work-related factors, including exposure to traumatic events, job characteristics, and organizational variables, as significant predictors of burnout. Key determinants include job demands, job control, social support, and exposure to traumatic events. The review highlights the high burnout rates in this population and formulates specific action targets for hospital management to prevent turnover and burnout, emphasizing the need for interventions addressing these identified factors. The review underscores the importance of understanding and mitigating burnout within this high-stress healthcare environment, offering insights into potential interventions and management strategies.

Review

Determinantsand prevalenceof burnout in emergency

nurses: A systematicreview of 25 years of research

Jef Adriaenssensa,

*, Ve´ronique De Guchtb

, Stan Maesc

a LeidenUniversity,Instituteof PsychologyHealthPsychology,PO Box 9555,2300 RB Leiden,The Netherlands

b LeidenUniversity,Instituteof PsychologyHealthPsychology,2300 RB Leiden,The Netherlands

c LeidenUniversity,Instituteof Psychologyand LeidenUniversityMedicalCenterHealthPsychology,2300RB Leiden,The Netherlands

Contributions of the paper Burnout has important consequencesfor the health care

InternationalJournal of Nursing Studiesxxx (2014) xxx–xxx

A R T I C L E I N F O

Articlehistory:

Received12 April 2014

Receivedin revisedform 24 October2014

Accepted4 November2014

Keywords:

Burnout

Emergencynursing

Literaturereview

Occupationalstress

Work characteristics

A B S T R A C T

Background:Burnoutis an importantproblemin healthcareprofessionalsand is associated

with a decreasein occupationalwell-being and an increasein absenteeism,turnover and

illness.Nursesarefoundto be vulnerableto burnout,but emergencynursesareevenmoreso,

sinceemergencynursingis characterizedby unpredictability,overcrowdingand continuous

confrontationwith a broad rangeof diseases,injuries and traumaticevents.

Objectives:This systematic review aims (1) to explore the prevalence of burnout in

emergencynurses and (2) to identify specific(individual and work related)determinants

of burnout in this population.

Method: A systematicreview of empirical quantitativestudies on burnout in emergency

nurses, published in English between 1989 and 2014.

Data sources:The databasesNCBI PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge, Informa

HealthCare,Picarta, Cinahl and Scielo were searched.

Results:Seventeenstudieswere included in this review.On average26%of the emergency

nurses suffered from burnout. Individual factors such as demographic variables,

personality characteristics and coping strategies were predictive of burnout. Work

relatedfactorssuch as exposureto traumaticevents,job characteristicsand organizational

variableswere also found to be determinantsof burnout in this population.

Conclusions:Burnout ratesin emergencynursesare high. Job demands,job control, social

support and exposureto traumaticeventsare determinantsof burnout, as well as several

organizationalvariables.As a consequencespecific action targets for hospital manage-

ment are formulated to prevent turnover and burnout in emergencynurses.

ß 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

InternationalJournal of Nursing Studies

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/ijns

Determinantsand prevalenceof burnout in emergency

nurses: A systematicreview of 25 years of research

Jef Adriaenssensa,

*, Ve´ronique De Guchtb

, Stan Maesc

a LeidenUniversity,Instituteof PsychologyHealthPsychology,PO Box 9555,2300 RB Leiden,The Netherlands

b LeidenUniversity,Instituteof PsychologyHealthPsychology,2300 RB Leiden,The Netherlands

c LeidenUniversity,Instituteof Psychologyand LeidenUniversityMedicalCenterHealthPsychology,2300RB Leiden,The Netherlands

Contributions of the paper Burnout has important consequencesfor the health care

InternationalJournal of Nursing Studiesxxx (2014) xxx–xxx

A R T I C L E I N F O

Articlehistory:

Received12 April 2014

Receivedin revisedform 24 October2014

Accepted4 November2014

Keywords:

Burnout

Emergencynursing

Literaturereview

Occupationalstress

Work characteristics

A B S T R A C T

Background:Burnoutis an importantproblemin healthcareprofessionalsand is associated

with a decreasein occupationalwell-being and an increasein absenteeism,turnover and

illness.Nursesarefoundto be vulnerableto burnout,but emergencynursesareevenmoreso,

sinceemergencynursingis characterizedby unpredictability,overcrowdingand continuous

confrontationwith a broad rangeof diseases,injuries and traumaticevents.

Objectives:This systematic review aims (1) to explore the prevalence of burnout in

emergencynurses and (2) to identify specific(individual and work related)determinants

of burnout in this population.

Method: A systematicreview of empirical quantitativestudies on burnout in emergency

nurses, published in English between 1989 and 2014.

Data sources:The databasesNCBI PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge, Informa

HealthCare,Picarta, Cinahl and Scielo were searched.

Results:Seventeenstudieswere included in this review.On average26%of the emergency

nurses suffered from burnout. Individual factors such as demographic variables,

personality characteristics and coping strategies were predictive of burnout. Work

relatedfactorssuch as exposureto traumaticevents,job characteristicsand organizational

variableswere also found to be determinantsof burnout in this population.

Conclusions:Burnout ratesin emergencynursesare high. Job demands,job control, social

support and exposureto traumaticeventsare determinantsof burnout, as well as several

organizationalvariables.As a consequencespecific action targets for hospital manage-

ment are formulated to prevent turnover and burnout in emergencynurses.

ß 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

InternationalJournal of Nursing Studies

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/ijns

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A broad set of predictors for burnout in emergency

nurses was described: demographic and personality

characteristics,coping strategies,exposureto traumatic

events,job characteristicsand organizationalfactors.

Level of professionalautonomy,team spirit and social

support,quality of leadership,and frequencyof exposure

to traumaticeventswere found to be strongpredictorsof

burnout in emergencynurses.

1. Introduction

Severalstudies show that a positive experienceof the

work environment(low strain) is relatedto work engage-

ment and professional commitment, while a negative

perception(high strain) is relatedto a stateof depletionof

resources,called ‘burnout’(Ahola et al., 2009).In the early

’70sof the last century,Freudenbergerdefinedburnout as

‘the extinctionof motivationor incentive,especiallywhere

one’sdevotionto a causeor relationshipfails to producethe

desired results’ (Freudenberger, 1974). Shortly after,

Christina Maslach defined burnout as a psychological

stateresultingfrom prolongedemotionalor psychological

stresson the job (Maslach and Jackson,1981a,b;Maslach

et al.,2001).Maslachseesburnoutas an internalemotional

reaction (illness) caused by external factors, resulting in

loss of personal and/or social resources: ‘Burnoutis the

indexof the dislocationbetweenwhat peopleare and what

theyhaveto do.It representserosionin values,dignity,spirit,

and will—an erosionof the human soul. It’s a maladythat

spreadsgraduallyand continuouslyovertime,puttingpeople

into a downward spiral from which it’s hard to recover’

(Maslach and Leiter, 1997).

Burnout,as defined by Maslach,has three dimensions.

The first dimensionof the burnoutsyndromeis ‘‘emotional

exhaustion’’.When the emotional reservesare depleted,

employeesfeel that they are no longerableto providework

of good quality. They have feelingsof extremeenergyloss

and a senseof being completelydrained out of emotional

and physicalstrength(Maslachand Jackson,1981a,b).The

second dimension ‘‘depersonalization’’is defined as the

developmentof negativeattitudes,such as cynicism and

negativism,both in thinking as well as in behavior, in

which coworkers and service recipients are approached

with derogatory prejudices and treated accordingly

(Maslach and Jackson,1981a,b).The third aspectis ‘‘lack

of personal accomplishment’’.This is defined as lack of

feelingsregardingboth job and personalcompetenceand

2011). Finally, burnout can also lead to a significant

economic loss through increased absenteeism,higher

turnover rates and a rise in health care costs (Borritz

et al., 2006).

The prevalenceof burnout, assessedby use of a self-

report instrument in a general working population in

Western countries, ranges from 13% to 27% (Norlund

et al., 2010; Lindblom et al., 2006; Kant et al., 2004;

Houtmanet al., 2000;Aromaaand Koskinen,2004).Nurses

are known to be at higher risk for the developmentof

burnout then other occupations(Maslach,2003; Gelsema

et al., 2006). Researchshowed that nurses indeed report

high levels of work relatedstress(Hasselhornet al., 2003;

Smith et al., 2000; Clegg,2001; McVicar, 2003) and that

30%to 50%reach clinical levels of burnout (Aiken et al.,

2002; Poncetet al., 2007; Gelsemaet al., 2006).According

to severalauthors,the demandsthat burdenthe nurses(in

terms of work setting, task description, responsibility,

unpredictabilityand the exposureto potentiallytraumatic

situations)and the resourcesthey can rely on, are strongly

related to the content of their job and their nursing

specialty(Browninget al.,2007;Ergunet al.,2005;Eriksen,

2006; Kipping, 2000; Mealer et al., 2007).Emergency(ER)

nursing is a specialty that differs from other nursing

specialties: work in emergency departments is hectic,

unpredictable and constantly changing. ER-nurses are

confrontedwith a very broad range of diseases,injuries

and problems.Moreover,due to the hecticwork conditions

and overcrowding,emergencynurses often have to move

from one urgencyto another,with oftenlittle recoverytime

(Alexander and Klein, 2001; Gates et al., 2011). As a

consequence,rates of burnout are found to be very high in

emergencynursing settings (Hooper et al., 2010; Potter,

2006).

2. The review

2.1. Aim

The aim of the presentreview is (1) to examinethe level

of burnout in ER-nurses and (2) to identify specific

determinantsof burnout in thesenurses,includingvarious

individual and work-related factors.

2.2. Searchmethods

The databases NCBI PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx2

nurses was described: demographic and personality

characteristics,coping strategies,exposureto traumatic

events,job characteristicsand organizationalfactors.

Level of professionalautonomy,team spirit and social

support,quality of leadership,and frequencyof exposure

to traumaticeventswere found to be strongpredictorsof

burnout in emergencynurses.

1. Introduction

Severalstudies show that a positive experienceof the

work environment(low strain) is relatedto work engage-

ment and professional commitment, while a negative

perception(high strain) is relatedto a stateof depletionof

resources,called ‘burnout’(Ahola et al., 2009).In the early

’70sof the last century,Freudenbergerdefinedburnout as

‘the extinctionof motivationor incentive,especiallywhere

one’sdevotionto a causeor relationshipfails to producethe

desired results’ (Freudenberger, 1974). Shortly after,

Christina Maslach defined burnout as a psychological

stateresultingfrom prolongedemotionalor psychological

stresson the job (Maslach and Jackson,1981a,b;Maslach

et al.,2001).Maslachseesburnoutas an internalemotional

reaction (illness) caused by external factors, resulting in

loss of personal and/or social resources: ‘Burnoutis the

indexof the dislocationbetweenwhat peopleare and what

theyhaveto do.It representserosionin values,dignity,spirit,

and will—an erosionof the human soul. It’s a maladythat

spreadsgraduallyand continuouslyovertime,puttingpeople

into a downward spiral from which it’s hard to recover’

(Maslach and Leiter, 1997).

Burnout,as defined by Maslach,has three dimensions.

The first dimensionof the burnoutsyndromeis ‘‘emotional

exhaustion’’.When the emotional reservesare depleted,

employeesfeel that they are no longerableto providework

of good quality. They have feelingsof extremeenergyloss

and a senseof being completelydrained out of emotional

and physicalstrength(Maslachand Jackson,1981a,b).The

second dimension ‘‘depersonalization’’is defined as the

developmentof negativeattitudes,such as cynicism and

negativism,both in thinking as well as in behavior, in

which coworkers and service recipients are approached

with derogatory prejudices and treated accordingly

(Maslach and Jackson,1981a,b).The third aspectis ‘‘lack

of personal accomplishment’’.This is defined as lack of

feelingsregardingboth job and personalcompetenceand

2011). Finally, burnout can also lead to a significant

economic loss through increased absenteeism,higher

turnover rates and a rise in health care costs (Borritz

et al., 2006).

The prevalenceof burnout, assessedby use of a self-

report instrument in a general working population in

Western countries, ranges from 13% to 27% (Norlund

et al., 2010; Lindblom et al., 2006; Kant et al., 2004;

Houtmanet al., 2000;Aromaaand Koskinen,2004).Nurses

are known to be at higher risk for the developmentof

burnout then other occupations(Maslach,2003; Gelsema

et al., 2006). Researchshowed that nurses indeed report

high levels of work relatedstress(Hasselhornet al., 2003;

Smith et al., 2000; Clegg,2001; McVicar, 2003) and that

30%to 50%reach clinical levels of burnout (Aiken et al.,

2002; Poncetet al., 2007; Gelsemaet al., 2006).According

to severalauthors,the demandsthat burdenthe nurses(in

terms of work setting, task description, responsibility,

unpredictabilityand the exposureto potentiallytraumatic

situations)and the resourcesthey can rely on, are strongly

related to the content of their job and their nursing

specialty(Browninget al.,2007;Ergunet al.,2005;Eriksen,

2006; Kipping, 2000; Mealer et al., 2007).Emergency(ER)

nursing is a specialty that differs from other nursing

specialties: work in emergency departments is hectic,

unpredictable and constantly changing. ER-nurses are

confrontedwith a very broad range of diseases,injuries

and problems.Moreover,due to the hecticwork conditions

and overcrowding,emergencynurses often have to move

from one urgencyto another,with oftenlittle recoverytime

(Alexander and Klein, 2001; Gates et al., 2011). As a

consequence,rates of burnout are found to be very high in

emergencynursing settings (Hooper et al., 2010; Potter,

2006).

2. The review

2.1. Aim

The aim of the presentreview is (1) to examinethe level

of burnout in ER-nurses and (2) to identify specific

determinantsof burnout in thesenurses,includingvarious

individual and work-related factors.

2.2. Searchmethods

The databases NCBI PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx2

‘‘Nurses’’[Mesh],nursing staff, health professional,para-

medic, medical staff, critical incident, critical event,

traumatic event, predictor, determinant. The primary

outcome key words were burnout, exhaustion, fatigue,

‘‘Burnout, Professional’’[Mesh] and M.B.I. but also the

secondary outcomes job satisfaction, turnover, mental

health, occupationalhealth, anxiety,depression,somatic,

post-traumaticstress,secondarytraumatic stress,‘‘Stress

Disorders,Post-Traumatic’’[Mesh], PTSD and P.T.S.Dwere

taken into account.

Studieswere includedonly if the following criteriawere

met: the respondentsunder study (N 40) were nurses,

and a well-defined part of the respondentsworked in an

emergencyunit or in ambulancecare,(2) the focus of the

study had to be on determinants/predictorsof burnout,

(3) the study had to be empirical and quantitative and

(4) the responserate was higher than 25%.

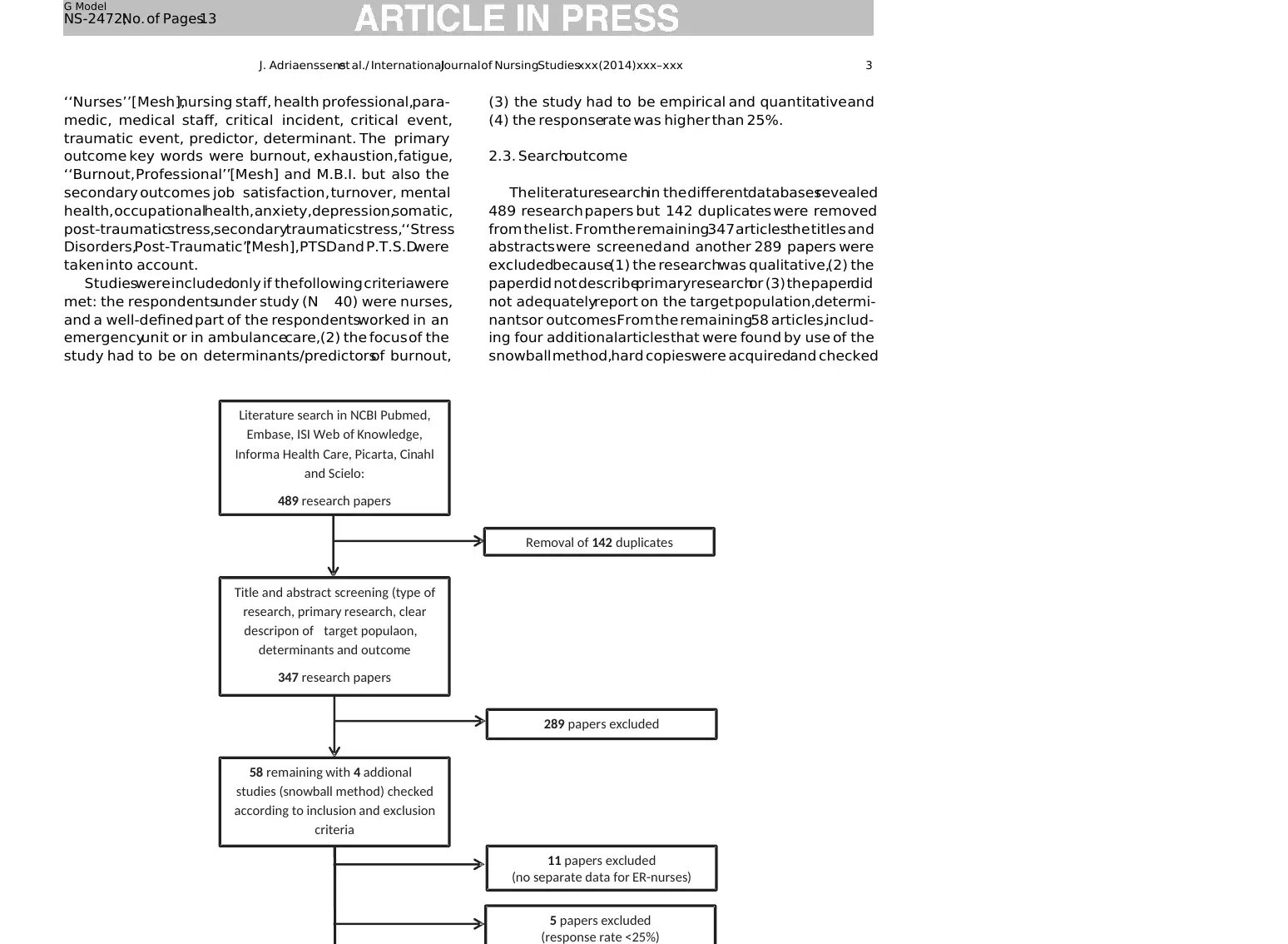

2.3. Searchoutcome

The literaturesearchin the differentdatabasesrevealed

489 research papers but 142 duplicates were removed

from the list. From the remaining347 articlesthe titles and

abstracts were screened and another 289 papers were

excludedbecause(1) the researchwas qualitative,(2) the

paperdid not describeprimaryresearchor (3) the paperdid

not adequatelyreport on the target population,determi-

nantsor outcomes.From the remaining58 articles,includ-

ing four additional articles that were found by use of the

snowball method,hard copieswere acquiredand checked

Literature search in NCBI Pubmed,

Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge,

Informa Health Care, Picarta, Cinahl

and Scielo:

489 research papers

Title and abstract screening (type of

research, primary research, clear

descripon of target populaon,

determinants and outcome

347 research papers

Removal of 142 duplicates

289 papers excluded

58 remaining with 4 addional

studies (snowball method) checked

according to inclusion and exclusion

criteria

11 papers excluded

(no separate data for ER-nurses)

5 papers excluded

(response rate <25%)

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 3

medic, medical staff, critical incident, critical event,

traumatic event, predictor, determinant. The primary

outcome key words were burnout, exhaustion, fatigue,

‘‘Burnout, Professional’’[Mesh] and M.B.I. but also the

secondary outcomes job satisfaction, turnover, mental

health, occupationalhealth, anxiety,depression,somatic,

post-traumaticstress,secondarytraumatic stress,‘‘Stress

Disorders,Post-Traumatic’’[Mesh], PTSD and P.T.S.Dwere

taken into account.

Studieswere includedonly if the following criteriawere

met: the respondentsunder study (N 40) were nurses,

and a well-defined part of the respondentsworked in an

emergencyunit or in ambulancecare,(2) the focus of the

study had to be on determinants/predictorsof burnout,

(3) the study had to be empirical and quantitative and

(4) the responserate was higher than 25%.

2.3. Searchoutcome

The literaturesearchin the differentdatabasesrevealed

489 research papers but 142 duplicates were removed

from the list. From the remaining347 articlesthe titles and

abstracts were screened and another 289 papers were

excludedbecause(1) the researchwas qualitative,(2) the

paperdid not describeprimaryresearchor (3) the paperdid

not adequatelyreport on the target population,determi-

nantsor outcomes.From the remaining58 articles,includ-

ing four additional articles that were found by use of the

snowball method,hard copieswere acquiredand checked

Literature search in NCBI Pubmed,

Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge,

Informa Health Care, Picarta, Cinahl

and Scielo:

489 research papers

Title and abstract screening (type of

research, primary research, clear

descripon of target populaon,

determinants and outcome

347 research papers

Removal of 142 duplicates

289 papers excluded

58 remaining with 4 addional

studies (snowball method) checked

according to inclusion and exclusion

criteria

11 papers excluded

(no separate data for ER-nurses)

5 papers excluded

(response rate <25%)

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

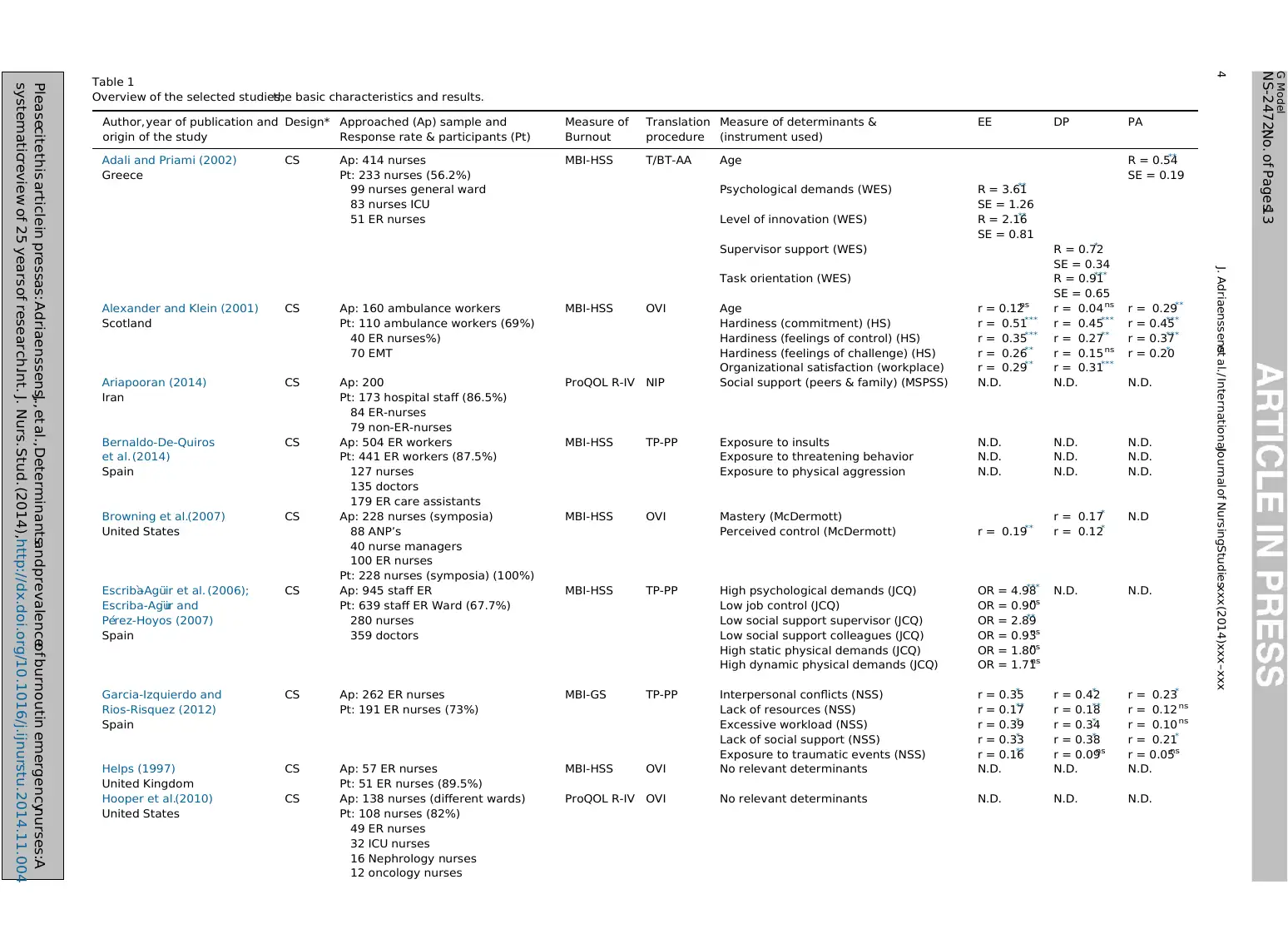

Table 1

Overview of the selected studies,the basic characteristics and results.

Author,year of publication and

origin of the study

Design* Approached (Ap) sample and

Response rate & participants (Pt)

Measure of

Burnout

Translation

procedure

Measure of determinants &

(instrument used)

EE DP PA

Adali and Priami (2002)

Greece

CS Ap: 414 nurses

Pt: 233 nurses (56.2%)

99 nurses general ward

83 nurses ICU

51 ER nurses

MBI-HSS T/BT-AA Age R = 0.54**

SE = 0.19

Psychological demands (WES) R = 3.61**

SE = 1.26

Level of innovation (WES) R = 2.16**

SE = 0.81

Supervisor support (WES) R = 0.72*

SE = 0.34

Task orientation (WES) R = 0.91***

SE = 0.65

Alexander and Klein (2001)

Scotland

CS Ap: 160 ambulance workers

Pt: 110 ambulance workers (69%)

40 ER nurses%)

70 EMT

MBI-HSS OVI Age

Hardiness (commitment) (HS)

Hardiness (feelings of control) (HS)

Hardiness (feelings of challenge) (HS)

Organizational satisfaction (workplace)

r = 0.12ns

r = 0.51***

r = 0.35***

r = 0.26**

r = 0.29**

r = 0.04 ns

r = 0.45***

r = 0.27**

r = 0.15 ns

r = 0.31***

r = 0.29**

r = 0.45***

r = 0.37***

r = 0.20*

Ariapooran (2014)

Iran

CS Ap: 200

Pt: 173 hospital staff (86.5%)

84 ER-nurses

79 non-ER-nurses

ProQOL R-IV NIP Social support (peers & family) (MSPSS) N.D. N.D. N.D.

Bernaldo-De-Quiros

et al. (2014)

Spain

CS Ap: 504 ER workers

Pt: 441 ER workers (87.5%)

127 nurses

135 doctors

179 ER care assistants

MBI-HSS TP-PP Exposure to insults

Exposure to threatening behavior

Exposure to physical aggression

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

Browning et al.(2007)

United States

CS Ap: 228 nurses (symposia)

88 ANP’s

40 nurse managers

100 ER nurses

Pt: 228 nurses (symposia) (100%)

MBI-HSS OVI Mastery (McDermott) r = 0.17*

r = 0.12*

N.D

Perceived control (McDermott) r = 0.19**

Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al. (2006);

Escriba-Agu¨ir and

Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007)

Spain

CS Ap: 945 staff ER

Pt: 639 staff ER Ward (67.7%)

280 nurses

359 doctors

MBI-HSS TP-PP High psychological demands (JCQ)

Low job control (JCQ)

Low social support supervisor (JCQ)

Low social support colleagues (JCQ)

High static physical demands (JCQ)

High dynamic physical demands (JCQ)

OR = 4.98***

OR = 0.90ns

OR = 2.89**

OR = 0.93ns

OR = 1.80ns

OR = 1.71ns

N.D. N.D.

Garcia-Izquierdo and

Rios-Risquez (2012)

Spain

CS Ap: 262 ER nurses

Pt: 191 ER nurses (73%)

MBI-GS TP-PP Interpersonal conflicts (NSS)

Lack of resources (NSS)

Excessive workload (NSS)

Lack of social support (NSS)

Exposure to traumatic events (NSS)

r = 0.35*

r = 0.17**

r = 0.39*

r = 0.33*

r = 0.16**

r = 0.42*

r = 0.18**

r = 0.34*

r = 0.38*

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.23*

r = 0.12 ns

r = 0.10 ns

r = 0.21*

r = 0.05ns

Helps (1997)

United Kingdom

CS Ap: 57 ER nurses

Pt: 51 ER nurses (89.5%)

MBI-HSS OVI No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Hooper et al.(2010)

United States

CS Ap: 138 nurses (different wards)

Pt: 108 nurses (82%)

49 ER nurses

32 ICU nurses

16 Nephrology nurses

12 oncology nurses

ProQOL R-IV OVI No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Pleasecite this article in pressas: Adriaenssens,J., et al.,Determinantsand prevalenceof burnoutin emergencynurses:A

systematicreview of 25 years of research.Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2014),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx4

Overview of the selected studies,the basic characteristics and results.

Author,year of publication and

origin of the study

Design* Approached (Ap) sample and

Response rate & participants (Pt)

Measure of

Burnout

Translation

procedure

Measure of determinants &

(instrument used)

EE DP PA

Adali and Priami (2002)

Greece

CS Ap: 414 nurses

Pt: 233 nurses (56.2%)

99 nurses general ward

83 nurses ICU

51 ER nurses

MBI-HSS T/BT-AA Age R = 0.54**

SE = 0.19

Psychological demands (WES) R = 3.61**

SE = 1.26

Level of innovation (WES) R = 2.16**

SE = 0.81

Supervisor support (WES) R = 0.72*

SE = 0.34

Task orientation (WES) R = 0.91***

SE = 0.65

Alexander and Klein (2001)

Scotland

CS Ap: 160 ambulance workers

Pt: 110 ambulance workers (69%)

40 ER nurses%)

70 EMT

MBI-HSS OVI Age

Hardiness (commitment) (HS)

Hardiness (feelings of control) (HS)

Hardiness (feelings of challenge) (HS)

Organizational satisfaction (workplace)

r = 0.12ns

r = 0.51***

r = 0.35***

r = 0.26**

r = 0.29**

r = 0.04 ns

r = 0.45***

r = 0.27**

r = 0.15 ns

r = 0.31***

r = 0.29**

r = 0.45***

r = 0.37***

r = 0.20*

Ariapooran (2014)

Iran

CS Ap: 200

Pt: 173 hospital staff (86.5%)

84 ER-nurses

79 non-ER-nurses

ProQOL R-IV NIP Social support (peers & family) (MSPSS) N.D. N.D. N.D.

Bernaldo-De-Quiros

et al. (2014)

Spain

CS Ap: 504 ER workers

Pt: 441 ER workers (87.5%)

127 nurses

135 doctors

179 ER care assistants

MBI-HSS TP-PP Exposure to insults

Exposure to threatening behavior

Exposure to physical aggression

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

N.D.

Browning et al.(2007)

United States

CS Ap: 228 nurses (symposia)

88 ANP’s

40 nurse managers

100 ER nurses

Pt: 228 nurses (symposia) (100%)

MBI-HSS OVI Mastery (McDermott) r = 0.17*

r = 0.12*

N.D

Perceived control (McDermott) r = 0.19**

Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al. (2006);

Escriba-Agu¨ir and

Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007)

Spain

CS Ap: 945 staff ER

Pt: 639 staff ER Ward (67.7%)

280 nurses

359 doctors

MBI-HSS TP-PP High psychological demands (JCQ)

Low job control (JCQ)

Low social support supervisor (JCQ)

Low social support colleagues (JCQ)

High static physical demands (JCQ)

High dynamic physical demands (JCQ)

OR = 4.98***

OR = 0.90ns

OR = 2.89**

OR = 0.93ns

OR = 1.80ns

OR = 1.71ns

N.D. N.D.

Garcia-Izquierdo and

Rios-Risquez (2012)

Spain

CS Ap: 262 ER nurses

Pt: 191 ER nurses (73%)

MBI-GS TP-PP Interpersonal conflicts (NSS)

Lack of resources (NSS)

Excessive workload (NSS)

Lack of social support (NSS)

Exposure to traumatic events (NSS)

r = 0.35*

r = 0.17**

r = 0.39*

r = 0.33*

r = 0.16**

r = 0.42*

r = 0.18**

r = 0.34*

r = 0.38*

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.23*

r = 0.12 ns

r = 0.10 ns

r = 0.21*

r = 0.05ns

Helps (1997)

United Kingdom

CS Ap: 57 ER nurses

Pt: 51 ER nurses (89.5%)

MBI-HSS OVI No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Hooper et al.(2010)

United States

CS Ap: 138 nurses (different wards)

Pt: 108 nurses (82%)

49 ER nurses

32 ICU nurses

16 Nephrology nurses

12 oncology nurses

ProQOL R-IV OVI No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Pleasecite this article in pressas: Adriaenssens,J., et al.,Determinantsand prevalenceof burnoutin emergencynurses:A

systematicreview of 25 years of research.Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2014),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

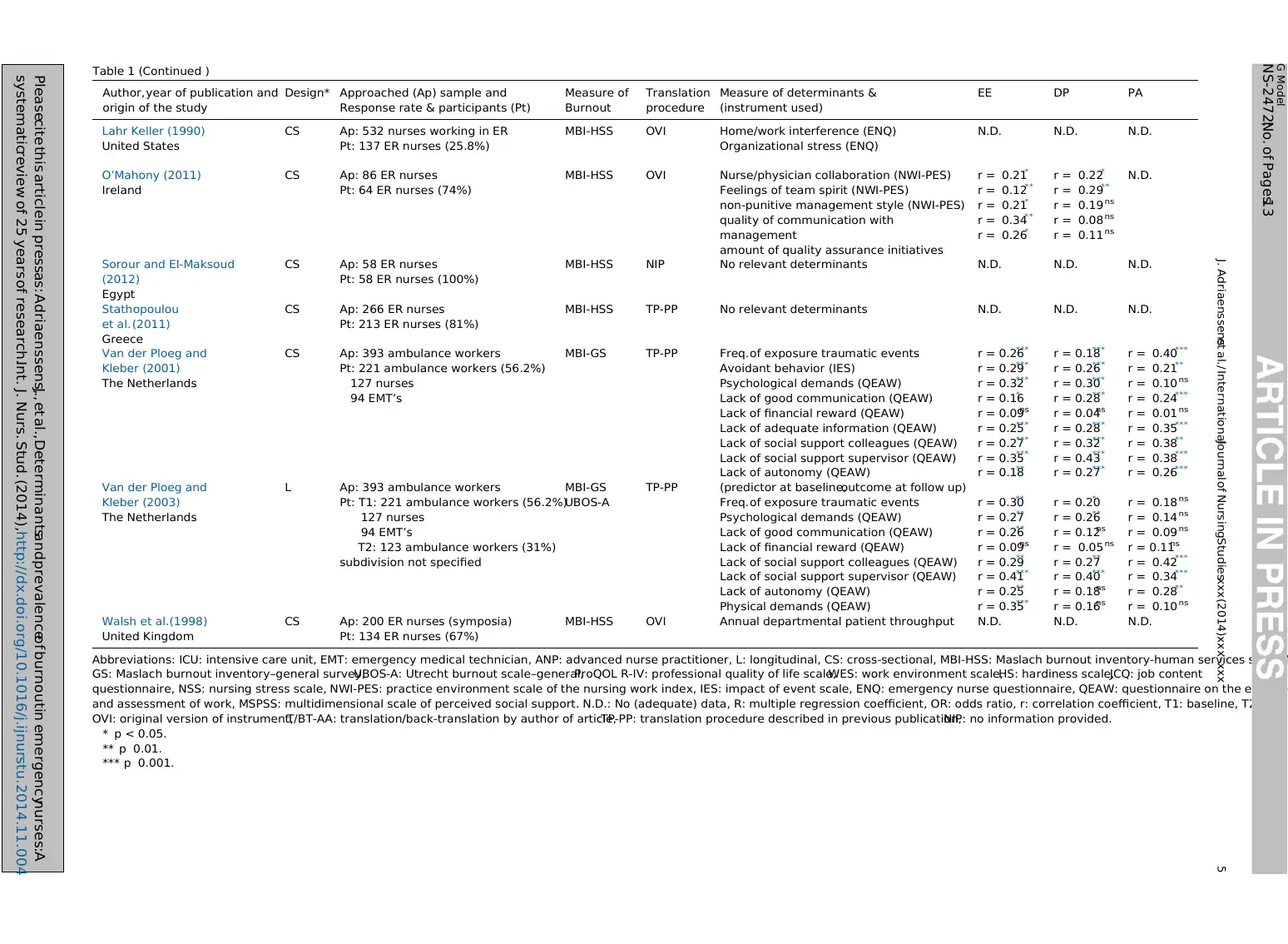

Table 1 (Continued )

Author,year of publication and

origin of the study

Design* Approached (Ap) sample and

Response rate & participants (Pt)

Measure of

Burnout

Translation

procedure

Measure of determinants &

(instrument used)

EE DP PA

Lahr Keller (1990)

United States

CS Ap: 532 nurses working in ER

Pt: 137 ER nurses (25.8%)

MBI-HSS OVI Home/work interference (ENQ)

Organizational stress (ENQ)

N.D. N.D. N.D.

O’Mahony (2011)

Ireland

CS Ap: 86 ER nurses

Pt: 64 ER nurses (74%)

MBI-HSS OVI Nurse/physician collaboration (NWI-PES)

Feelings of team spirit (NWI-PES)

non-punitive management style (NWI-PES)

quality of communication with

management

amount of quality assurance initiatives

r = 0.21*

r = 0.12**

r = 0.21*

r = 0.34**

r = 0.26*

r = 0.22*

r = 0.29**

r = 0.19 ns

r = 0.08 ns

r = 0.11 ns

N.D.

Sorour and El-Maksoud

(2012)

Egypt

CS Ap: 58 ER nurses

Pt: 58 ER nurses (100%)

MBI-HSS NIP No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Stathopoulou

et al. (2011)

Greece

CS Ap: 266 ER nurses

Pt: 213 ER nurses (81%)

MBI-HSS TP-PP No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2001)

The Netherlands

CS Ap: 393 ambulance workers

Pt: 221 ambulance workers (56.2%)

127 nurses

94 EMT’s

MBI-GS TP-PP Freq.of exposure traumatic events

Avoidant behavior (IES)

Psychological demands (QEAW)

Lack of good communication (QEAW)

Lack of financial reward (QEAW)

Lack of adequate information (QEAW)

Lack of social support colleagues (QEAW)

Lack of social support supervisor (QEAW)

Lack of autonomy (QEAW)

r = 0.26***

r = 0.29***

r = 0.32***

r = 0.16*

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.25***

r = 0.27***

r = 0.35***

r = 0.18**

r = 0.18***

r = 0.26***

r = 0.30***

r = 0.28***

r = 0.04ns

r = 0.28***

r = 0.32***

r = 0.43***

r = 0.27***

r = 0.40***

r = 0.21**

r = 0.10 ns

r = 0.24***

r = 0.01 ns

r = 0.35***

r = 0.38**

r = 0.38***

r = 0.26***

Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2003)

The Netherlands

L Ap: 393 ambulance workers

Pt: T1: 221 ambulance workers (56.2%)

127 nurses

94 EMT’s

T2: 123 ambulance workers (31%)

subdivision not specified

MBI-GS

UBOS-A

TP-PP (predictor at baseline,outcome at follow up)

Freq.of exposure traumatic events

Psychological demands (QEAW)

Lack of good communication (QEAW)

Lack of financial reward (QEAW)

Lack of social support colleagues (QEAW)

Lack of social support supervisor (QEAW)

Lack of autonomy (QEAW)

Physical demands (QEAW)

r = 0.30**

r = 0.27**

r = 0.26**

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.29**

r = 0.41***

r = 0.25**

r = 0.35***

r = 0.20*

r = 0.26**

r = 0.12ns

r = 0.05 ns

r = 0.27**

r = 0.40***

r = 0.18ns

r = 0.16ns

r = 0.18 ns

r = 0.14 ns

r = 0.09 ns

r = 0.11ns

r = 0.42***

r = 0.34***

r = 0.28**

r = 0.10 ns

Walsh et al.(1998)

United Kingdom

CS Ap: 200 ER nurses (symposia)

Pt: 134 ER nurses (67%)

MBI-HSS OVI Annual departmental patient throughput N.D. N.D. N.D.

Abbreviations: ICU: intensive care unit, EMT: emergency medical technician, ANP: advanced nurse practitioner, L: longitudinal, CS: cross-sectional, MBI-HSS: Maslach burnout inventory-human services scale, M

GS: Maslach burnout inventory–general survey,UBOS-A: Utrecht burnout scale–general,ProQOL R-IV: professional quality of life scale,WES: work environment scale,HS: hardiness scale,JCQ: job content

questionnaire, NSS: nursing stress scale, NWI-PES: practice environment scale of the nursing work index, IES: impact of event scale, ENQ: emergency nurse questionnaire, QEAW: questionnaire on the experie

and assessment of work, MSPSS: multidimensional scale of perceived social support. N.D.: No (adequate) data, R: multiple regression coefficient, OR: odds ratio, r: correlation coefficient, T1: baseline, T2: follo

OVI: original version of instrument,T/BT-AA: translation/back-translation by author of article,TP-PP: translation procedure described in previous publication,NIP: no information provided.

* p < 0.05.

** p 0.01.

*** p 0.001.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Pleasecite this article in pressas: Adriaenssens,J., et al.,Determinantsand prevalenceof burnoutin emergencynurses:A

systematicreview of 25 years of research.Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2014),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004

J. Adriaenssenset al. / InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 5

Author,year of publication and

origin of the study

Design* Approached (Ap) sample and

Response rate & participants (Pt)

Measure of

Burnout

Translation

procedure

Measure of determinants &

(instrument used)

EE DP PA

Lahr Keller (1990)

United States

CS Ap: 532 nurses working in ER

Pt: 137 ER nurses (25.8%)

MBI-HSS OVI Home/work interference (ENQ)

Organizational stress (ENQ)

N.D. N.D. N.D.

O’Mahony (2011)

Ireland

CS Ap: 86 ER nurses

Pt: 64 ER nurses (74%)

MBI-HSS OVI Nurse/physician collaboration (NWI-PES)

Feelings of team spirit (NWI-PES)

non-punitive management style (NWI-PES)

quality of communication with

management

amount of quality assurance initiatives

r = 0.21*

r = 0.12**

r = 0.21*

r = 0.34**

r = 0.26*

r = 0.22*

r = 0.29**

r = 0.19 ns

r = 0.08 ns

r = 0.11 ns

N.D.

Sorour and El-Maksoud

(2012)

Egypt

CS Ap: 58 ER nurses

Pt: 58 ER nurses (100%)

MBI-HSS NIP No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Stathopoulou

et al. (2011)

Greece

CS Ap: 266 ER nurses

Pt: 213 ER nurses (81%)

MBI-HSS TP-PP No relevant determinants N.D. N.D. N.D.

Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2001)

The Netherlands

CS Ap: 393 ambulance workers

Pt: 221 ambulance workers (56.2%)

127 nurses

94 EMT’s

MBI-GS TP-PP Freq.of exposure traumatic events

Avoidant behavior (IES)

Psychological demands (QEAW)

Lack of good communication (QEAW)

Lack of financial reward (QEAW)

Lack of adequate information (QEAW)

Lack of social support colleagues (QEAW)

Lack of social support supervisor (QEAW)

Lack of autonomy (QEAW)

r = 0.26***

r = 0.29***

r = 0.32***

r = 0.16*

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.25***

r = 0.27***

r = 0.35***

r = 0.18**

r = 0.18***

r = 0.26***

r = 0.30***

r = 0.28***

r = 0.04ns

r = 0.28***

r = 0.32***

r = 0.43***

r = 0.27***

r = 0.40***

r = 0.21**

r = 0.10 ns

r = 0.24***

r = 0.01 ns

r = 0.35***

r = 0.38**

r = 0.38***

r = 0.26***

Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2003)

The Netherlands

L Ap: 393 ambulance workers

Pt: T1: 221 ambulance workers (56.2%)

127 nurses

94 EMT’s

T2: 123 ambulance workers (31%)

subdivision not specified

MBI-GS

UBOS-A

TP-PP (predictor at baseline,outcome at follow up)

Freq.of exposure traumatic events

Psychological demands (QEAW)

Lack of good communication (QEAW)

Lack of financial reward (QEAW)

Lack of social support colleagues (QEAW)

Lack of social support supervisor (QEAW)

Lack of autonomy (QEAW)

Physical demands (QEAW)

r = 0.30**

r = 0.27**

r = 0.26**

r = 0.09ns

r = 0.29**

r = 0.41***

r = 0.25**

r = 0.35***

r = 0.20*

r = 0.26**

r = 0.12ns

r = 0.05 ns

r = 0.27**

r = 0.40***

r = 0.18ns

r = 0.16ns

r = 0.18 ns

r = 0.14 ns

r = 0.09 ns

r = 0.11ns

r = 0.42***

r = 0.34***

r = 0.28**

r = 0.10 ns

Walsh et al.(1998)

United Kingdom

CS Ap: 200 ER nurses (symposia)

Pt: 134 ER nurses (67%)

MBI-HSS OVI Annual departmental patient throughput N.D. N.D. N.D.

Abbreviations: ICU: intensive care unit, EMT: emergency medical technician, ANP: advanced nurse practitioner, L: longitudinal, CS: cross-sectional, MBI-HSS: Maslach burnout inventory-human services scale, M

GS: Maslach burnout inventory–general survey,UBOS-A: Utrecht burnout scale–general,ProQOL R-IV: professional quality of life scale,WES: work environment scale,HS: hardiness scale,JCQ: job content

questionnaire, NSS: nursing stress scale, NWI-PES: practice environment scale of the nursing work index, IES: impact of event scale, ENQ: emergency nurse questionnaire, QEAW: questionnaire on the experie

and assessment of work, MSPSS: multidimensional scale of perceived social support. N.D.: No (adequate) data, R: multiple regression coefficient, OR: odds ratio, r: correlation coefficient, T1: baseline, T2: follo

OVI: original version of instrument,T/BT-AA: translation/back-translation by author of article,TP-PP: translation procedure described in previous publication,NIP: no information provided.

* p < 0.05.

** p 0.01.

*** p 0.001.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

Pleasecite this article in pressas: Adriaenssens,J., et al.,Determinantsand prevalenceof burnoutin emergencynurses:A

systematicreview of 25 years of research.Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2014),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004

J. Adriaenssenset al. / InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 5

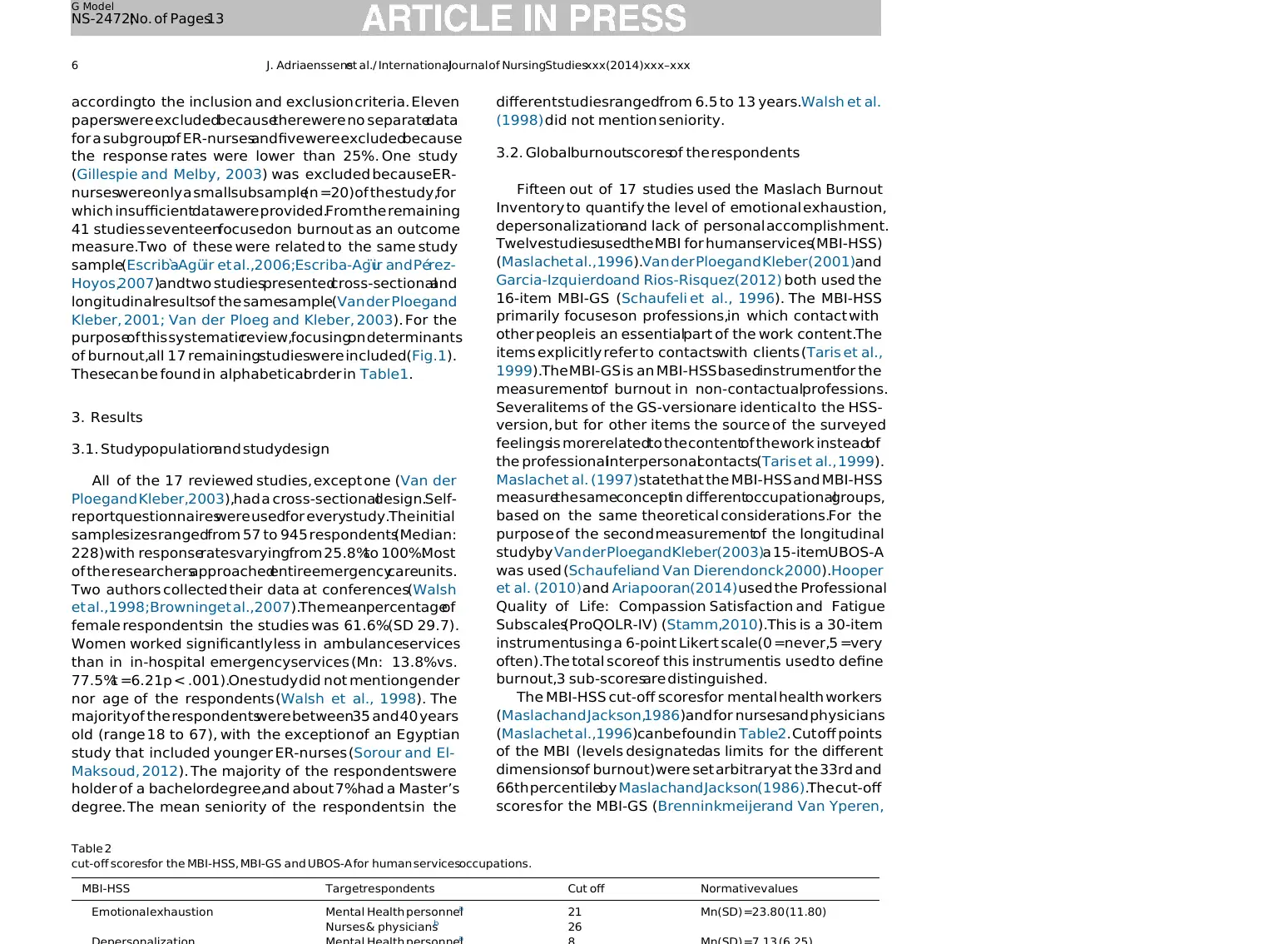

accordingto the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eleven

paperswere excludedbecausetherewere no separatedata

for a subgroupof ER-nursesand five were excludedbecause

the response rates were lower than 25%. One study

(Gillespie and Melby, 2003) was excluded because ER-

nurseswere only a smallsubsample(n =20) of the study,for

which insufficientdatawere provided.From the remaining

41 studies seventeenfocused on burnout as an outcome

measure.Two of these were related to the same study

sample(Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al.,2006;Escriba-Agu¨ir and Pe´rez-

Hoyos,2007)and two studiespresentedcross-sectionaland

longitudinalresultsof the samesample(Van der Ploegand

Kleber, 2001; Van der Ploeg and Kleber, 2003). For the

purposeof this systematicreview,focusingon determinants

of burnout,all 17 remainingstudieswere included(Fig. 1).

Thesecan be found in alphabeticalorder in Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Studypopulationand studydesign

All of the 17 reviewed studies, except one (Van der

Ploegand Kleber,2003),had a cross-sectionaldesign.Self-

reportquestionnaireswere usedfor everystudy.The initial

samplesizes rangedfrom 57 to 945 respondents(Median:

228) with responseratesvaryingfrom 25.8%to 100%.Most

of the researchersapproachedentire emergencycareunits.

Two authors collected their data at conferences(Walsh

et al.,1998; Browninget al.,2007).The meanpercentageof

female respondentsin the studies was 61.6%(SD 29.7).

Women worked significantly less in ambulanceservices

than in in-hospital emergency services (Mn: 13.8%vs.

77.5%t =6.21 p < .001).One study did not mention gender

nor age of the respondents (Walsh et al., 1998). The

majority of the respondentswere between35 and 40 years

old (range 18 to 67), with the exception of an Egyptian

study that included younger ER-nurses (Sorour and El-

Maksoud, 2012). The majority of the respondentswere

holder of a bachelordegree,and about 7%had a Master’s

degree. The mean seniority of the respondents in the

different studies rangedfrom 6.5 to 13 years.Walsh et al.

(1998) did not mention seniority.

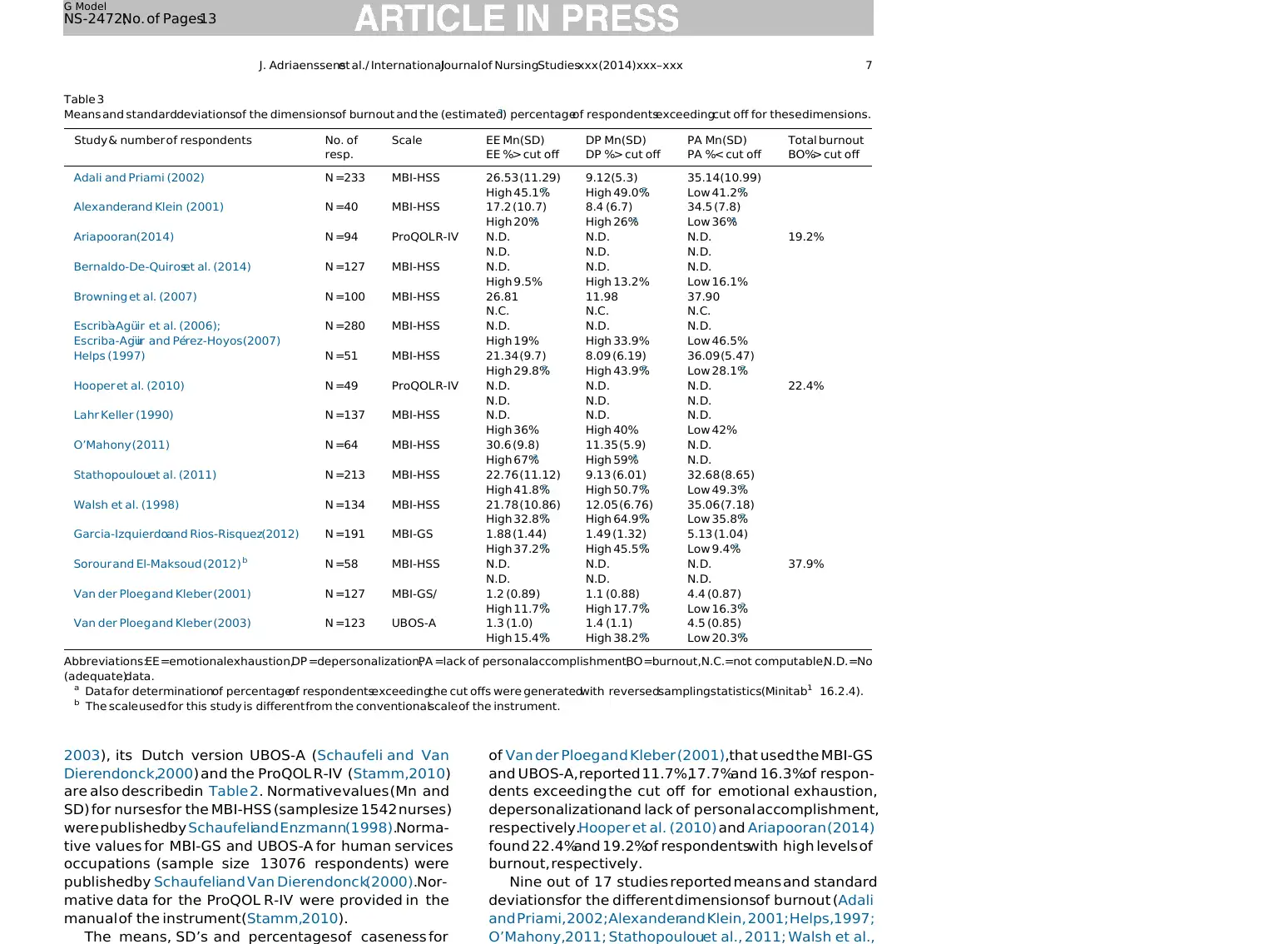

3.2. Globalburnoutscoresof the respondents

Fifteen out of 17 studies used the Maslach Burnout

Inventory to quantify the level of emotional exhaustion,

depersonalizationand lack of personal accomplishment.

Twelvestudiesusedthe MBI for humanservices(MBI-HSS)

(Maslachet al.,1996).Van der Ploegand Kleber (2001)and

Garcia-Izquierdoand Rios-Risquez(2012) both used the

16-item MBI-GS (Schaufeli et al., 1996). The MBI-HSS

primarily focuses on professions,in which contact with

other people is an essentialpart of the work content.The

items explicitly refer to contactswith clients (Taris et al.,

1999).The MBI-GS is an MBI-HSS basedinstrumentfor the

measurementof burnout in non-contactualprofessions.

Severalitems of the GS-versionare identical to the HSS-

version, but for other items the source of the surveyed

feelingsis morerelatedto the contentof the work insteadof

the professionalinterpersonalcontacts(Taris et al., 1999).

Maslach et al. (1997) statethat the MBI-HSS and MBI-HSS

measurethe sameconceptin differentoccupationalgroups,

based on the same theoretical considerations.For the

purpose of the second measurementof the longitudinal

studyby Van der Ploegand Kleber(2003)a 15-itemUBOS-A

was used (Schaufeliand Van Dierendonck,2000).Hooper

et al. (2010) and Ariapooran(2014) used the Professional

Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue

Subscales(ProQOLR-IV) (Stamm,2010).This is a 30-item

instrumentusing a 6-point Likert scale(0 =never,5 =very

often).The total score of this instrumentis used to define

burnout,3 sub-scoresare distinguished.

The MBI-HSS cut-off scoresfor mental health workers

(Maslachand Jackson,1986)and for nursesand physicians

(Maslachet al.,1996)can be found in Table2. Cut off points

of the MBI (levels designatedas limits for the different

dimensionsof burnout) were set arbitrary at the 33rd and

66th percentileby Maslachand Jackson(1986).The cut-off

scores for the MBI-GS (Brenninkmeijerand Van Yperen,

Table 2

cut-off scoresfor the MBI-HSS, MBI-GS and UBOS-A for human servicesoccupations.

MBI-HSS Targetrespondents Cut off Normativevalues

Emotional exhaustion Mental Health personnela

Nurses & physiciansb

21

26

Mn(SD) =23.80 (11.80)

a

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx6

paperswere excludedbecausetherewere no separatedata

for a subgroupof ER-nursesand five were excludedbecause

the response rates were lower than 25%. One study

(Gillespie and Melby, 2003) was excluded because ER-

nurseswere only a smallsubsample(n =20) of the study,for

which insufficientdatawere provided.From the remaining

41 studies seventeenfocused on burnout as an outcome

measure.Two of these were related to the same study

sample(Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al.,2006;Escriba-Agu¨ir and Pe´rez-

Hoyos,2007)and two studiespresentedcross-sectionaland

longitudinalresultsof the samesample(Van der Ploegand

Kleber, 2001; Van der Ploeg and Kleber, 2003). For the

purposeof this systematicreview,focusingon determinants

of burnout,all 17 remainingstudieswere included(Fig. 1).

Thesecan be found in alphabeticalorder in Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Studypopulationand studydesign

All of the 17 reviewed studies, except one (Van der

Ploegand Kleber,2003),had a cross-sectionaldesign.Self-

reportquestionnaireswere usedfor everystudy.The initial

samplesizes rangedfrom 57 to 945 respondents(Median:

228) with responseratesvaryingfrom 25.8%to 100%.Most

of the researchersapproachedentire emergencycareunits.

Two authors collected their data at conferences(Walsh

et al.,1998; Browninget al.,2007).The meanpercentageof

female respondentsin the studies was 61.6%(SD 29.7).

Women worked significantly less in ambulanceservices

than in in-hospital emergency services (Mn: 13.8%vs.

77.5%t =6.21 p < .001).One study did not mention gender

nor age of the respondents (Walsh et al., 1998). The

majority of the respondentswere between35 and 40 years

old (range 18 to 67), with the exception of an Egyptian

study that included younger ER-nurses (Sorour and El-

Maksoud, 2012). The majority of the respondentswere

holder of a bachelordegree,and about 7%had a Master’s

degree. The mean seniority of the respondents in the

different studies rangedfrom 6.5 to 13 years.Walsh et al.

(1998) did not mention seniority.

3.2. Globalburnoutscoresof the respondents

Fifteen out of 17 studies used the Maslach Burnout

Inventory to quantify the level of emotional exhaustion,

depersonalizationand lack of personal accomplishment.

Twelvestudiesusedthe MBI for humanservices(MBI-HSS)

(Maslachet al.,1996).Van der Ploegand Kleber (2001)and

Garcia-Izquierdoand Rios-Risquez(2012) both used the

16-item MBI-GS (Schaufeli et al., 1996). The MBI-HSS

primarily focuses on professions,in which contact with

other people is an essentialpart of the work content.The

items explicitly refer to contactswith clients (Taris et al.,

1999).The MBI-GS is an MBI-HSS basedinstrumentfor the

measurementof burnout in non-contactualprofessions.

Severalitems of the GS-versionare identical to the HSS-

version, but for other items the source of the surveyed

feelingsis morerelatedto the contentof the work insteadof

the professionalinterpersonalcontacts(Taris et al., 1999).

Maslach et al. (1997) statethat the MBI-HSS and MBI-HSS

measurethe sameconceptin differentoccupationalgroups,

based on the same theoretical considerations.For the

purpose of the second measurementof the longitudinal

studyby Van der Ploegand Kleber(2003)a 15-itemUBOS-A

was used (Schaufeliand Van Dierendonck,2000).Hooper

et al. (2010) and Ariapooran(2014) used the Professional

Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue

Subscales(ProQOLR-IV) (Stamm,2010).This is a 30-item

instrumentusing a 6-point Likert scale(0 =never,5 =very

often).The total score of this instrumentis used to define

burnout,3 sub-scoresare distinguished.

The MBI-HSS cut-off scoresfor mental health workers

(Maslachand Jackson,1986)and for nursesand physicians

(Maslachet al.,1996)can be found in Table2. Cut off points

of the MBI (levels designatedas limits for the different

dimensionsof burnout) were set arbitrary at the 33rd and

66th percentileby Maslachand Jackson(1986).The cut-off

scores for the MBI-GS (Brenninkmeijerand Van Yperen,

Table 2

cut-off scoresfor the MBI-HSS, MBI-GS and UBOS-A for human servicesoccupations.

MBI-HSS Targetrespondents Cut off Normativevalues

Emotional exhaustion Mental Health personnela

Nurses & physiciansb

21

26

Mn(SD) =23.80 (11.80)

a

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

2003), its Dutch version UBOS-A (Schaufeli and Van

Dierendonck,2000) and the ProQOL R-IV (Stamm,2010)

are also describedin Table 2. Normative values (Mn and

SD) for nurses for the MBI-HSS (samplesize 1542 nurses)

were publishedby Schaufeliand Enzmann(1998).Norma-

tive values for MBI-GS and UBOS-A for human services

occupations (sample size 13076 respondents) were

publishedby Schaufeliand Van Dierendonck(2000).Nor-

mative data for the ProQOL R-IV were provided in the

manual of the instrument (Stamm,2010).

The means, SD’s and percentages of caseness for

of Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2001),that used the MBI-GS

and UBOS-A, reported 11.7%,17.7%and 16.3%of respon-

dents exceeding the cut off for emotional exhaustion,

depersonalizationand lack of personal accomplishment,

respectively.Hooper et al. (2010) and Ariapooran (2014)

found 22.4%and 19.2%of respondentswith high levels of

burnout, respectively.

Nine out of 17 studies reported means and standard

deviationsfor the different dimensionsof burnout (Adali

and Priami, 2002; Alexanderand Klein, 2001; Helps,1997;

O’Mahony,2011; Stathopoulouet al., 2011; Walsh et al.,

Table 3

Means and standarddeviationsof the dimensionsof burnout and the (estimateda

) percentageof respondentsexceedingcut off for these dimensions.

Study & number of respondents No. of

resp.

Scale EE Mn(SD)

EE %> cut off

DP Mn(SD)

DP %> cut off

PA Mn(SD)

PA %< cut off

Total burnout

BO%> cut off

Adali and Priami (2002) N =233 MBI-HSS 26.53 (11.29) 9.12(5.3) 35.14(10.99)

High 45.1%a High 49.0%a Low 41.2%a

Alexanderand Klein (2001) N =40 MBI-HSS 17.2 (10.7) 8.4 (6.7) 34.5 (7.8)

High 20%a High 26%a Low 36%a

Ariapooran(2014) N =94 ProQOL R-IV N.D. N.D. N.D. 19.2%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Bernaldo-De-Quiroset al. (2014) N =127 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 9.5% High 13.2% Low 16.1%

Browning et al. (2007) N =100 MBI-HSS 26.81 11.98 37.90

N.C. N.C. N.C.

Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al. (2006);

Escriba-Agu¨ir and Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007)

N =280 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 19% High 33.9% Low 46.5%

Helps (1997) N =51 MBI-HSS 21.34 (9.7) 8.09 (6.19) 36.09 (5.47)

High 29.8%a High 43.9%a Low 28.1%a

Hooper et al. (2010) N =49 ProQOL R-IV N.D. N.D. N.D. 22.4%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Lahr Keller (1990) N =137 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 36% High 40% Low 42%

O’Mahony (2011) N =64 MBI-HSS 30.6 (9.8) 11.35 (5.9) N.D.

High 67%a High 59%a N.D.

Stathopoulouet al. (2011) N =213 MBI-HSS 22.76 (11.12) 9.13 (6.01) 32.68 (8.65)

High 41.8%a High 50.7%a Low 49.3%a

Walsh et al. (1998) N =134 MBI-HSS 21.78 (10.86) 12.05 (6.76) 35.06 (7.18)

High 32.8%a High 64.9%a Low 35.8%a

Garcia-Izquierdoand Rios-Risquez(2012) N =191 MBI-GS 1.88 (1.44) 1.49 (1.32) 5.13 (1.04)

High 37.2%a High 45.5%a Low 9.4%a

Sorour and El-Maksoud (2012) b N =58 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D. 37.9%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2001) N =127 MBI-GS/ 1.2 (0.89) 1.1 (0.88) 4.4 (0.87)

High 11.7%a High 17.7%a Low 16.3%a

Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2003) N =123 UBOS-A 1.3 (1.0) 1.4 (1.1) 4.5 (0.85)

High 15.4%a High 38.2%a Low 20.3%a

Abbreviations:EE =emotionalexhaustion,DP =depersonalization,PA =lack of personalaccomplishment,BO =burnout,N.C.=not computable,N.D. =No

(adequate)data.

a Data for determinationof percentageof respondentsexceedingthe cut offs were generatedwith reversedsamplingstatistics(Minitab1 16.2.4).

b The scale used for this study is different from the conventionalscale of the instrument.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 7

Dierendonck,2000) and the ProQOL R-IV (Stamm,2010)

are also describedin Table 2. Normative values (Mn and

SD) for nurses for the MBI-HSS (samplesize 1542 nurses)

were publishedby Schaufeliand Enzmann(1998).Norma-

tive values for MBI-GS and UBOS-A for human services

occupations (sample size 13076 respondents) were

publishedby Schaufeliand Van Dierendonck(2000).Nor-

mative data for the ProQOL R-IV were provided in the

manual of the instrument (Stamm,2010).

The means, SD’s and percentages of caseness for

of Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2001),that used the MBI-GS

and UBOS-A, reported 11.7%,17.7%and 16.3%of respon-

dents exceeding the cut off for emotional exhaustion,

depersonalizationand lack of personal accomplishment,

respectively.Hooper et al. (2010) and Ariapooran (2014)

found 22.4%and 19.2%of respondentswith high levels of

burnout, respectively.

Nine out of 17 studies reported means and standard

deviationsfor the different dimensionsof burnout (Adali

and Priami, 2002; Alexanderand Klein, 2001; Helps,1997;

O’Mahony,2011; Stathopoulouet al., 2011; Walsh et al.,

Table 3

Means and standarddeviationsof the dimensionsof burnout and the (estimateda

) percentageof respondentsexceedingcut off for these dimensions.

Study & number of respondents No. of

resp.

Scale EE Mn(SD)

EE %> cut off

DP Mn(SD)

DP %> cut off

PA Mn(SD)

PA %< cut off

Total burnout

BO%> cut off

Adali and Priami (2002) N =233 MBI-HSS 26.53 (11.29) 9.12(5.3) 35.14(10.99)

High 45.1%a High 49.0%a Low 41.2%a

Alexanderand Klein (2001) N =40 MBI-HSS 17.2 (10.7) 8.4 (6.7) 34.5 (7.8)

High 20%a High 26%a Low 36%a

Ariapooran(2014) N =94 ProQOL R-IV N.D. N.D. N.D. 19.2%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Bernaldo-De-Quiroset al. (2014) N =127 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 9.5% High 13.2% Low 16.1%

Browning et al. (2007) N =100 MBI-HSS 26.81 11.98 37.90

N.C. N.C. N.C.

Escriba`-Agu¨ir et al. (2006);

Escriba-Agu¨ir and Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007)

N =280 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 19% High 33.9% Low 46.5%

Helps (1997) N =51 MBI-HSS 21.34 (9.7) 8.09 (6.19) 36.09 (5.47)

High 29.8%a High 43.9%a Low 28.1%a

Hooper et al. (2010) N =49 ProQOL R-IV N.D. N.D. N.D. 22.4%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Lahr Keller (1990) N =137 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D.

High 36% High 40% Low 42%

O’Mahony (2011) N =64 MBI-HSS 30.6 (9.8) 11.35 (5.9) N.D.

High 67%a High 59%a N.D.

Stathopoulouet al. (2011) N =213 MBI-HSS 22.76 (11.12) 9.13 (6.01) 32.68 (8.65)

High 41.8%a High 50.7%a Low 49.3%a

Walsh et al. (1998) N =134 MBI-HSS 21.78 (10.86) 12.05 (6.76) 35.06 (7.18)

High 32.8%a High 64.9%a Low 35.8%a

Garcia-Izquierdoand Rios-Risquez(2012) N =191 MBI-GS 1.88 (1.44) 1.49 (1.32) 5.13 (1.04)

High 37.2%a High 45.5%a Low 9.4%a

Sorour and El-Maksoud (2012) b N =58 MBI-HSS N.D. N.D. N.D. 37.9%

N.D. N.D. N.D.

Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2001) N =127 MBI-GS/ 1.2 (0.89) 1.1 (0.88) 4.4 (0.87)

High 11.7%a High 17.7%a Low 16.3%a

Van der Ploeg and Kleber (2003) N =123 UBOS-A 1.3 (1.0) 1.4 (1.1) 4.5 (0.85)

High 15.4%a High 38.2%a Low 20.3%a

Abbreviations:EE =emotionalexhaustion,DP =depersonalization,PA =lack of personalaccomplishment,BO =burnout,N.C.=not computable,N.D. =No

(adequate)data.

a Data for determinationof percentageof respondentsexceedingthe cut offs were generatedwith reversedsamplingstatistics(Minitab1 16.2.4).

b The scale used for this study is different from the conventionalscale of the instrument.

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

while Van der Ploegand Kleber (2001)reportedthe lowest

values for all these dimensions.

For the purpose of this study and with the aim to

estimatethe prevalenceof burnout amongER-nurses,we

used reverse sampling statistics (Minitabß 16.2.4,Penn-

sylvania) to generaterandom data for the seven studies

that reportedonly meansand standarddeviationsfor the

MBI-dimensions. For this reverse sampling method we

assumed,based on previous findings, that the reported

data of the burnout dimensionshad a normal distribution

(Schaufeliet al., 2002; Langelaanet al., 2007; Camposand

Maroco, 2012). The cut off scores for the respective

instruments were used to determine the percentageof

respondentswith high emotionalexhaustion,high deper-

sonalization and low personal accomplishment. The

results of these analyses are reported in Table 3. A

weighted averagepercentageof casenessfor emotional

exhaustion, depersonalizationand lack of personal ac-

complishmentwas calculated.Basedupon the scores for

the reversely generated samples and the originally

reported cut off percentages,on average 25.9% of the

respondents exceededthe cut off scores for emotional

exhaustion,34.8%exceededthe cut offs for depersonali-

zation and 27.2%exceededthe cut off for lack of personal

accomplishment.Consideringthe generalconsensusthat

emotional exhaustion is the core dimension of burnout,

this review shows that 26% of the respondents in the

selectedstudies suffered from burnout.

3.3. Determinantsfor burnoutin emergencynurses

The studies that were included in this review used a

varietyof determinants.For the purposeof this review we

categorized these determinants in terms of ‘individual

factors’and ‘job related factors’,basedon an overview of

burnout by Maslach et al. (2001). For each category,a

generalintroduction is given,followed by the description

of the results for the selected studies on burnout in

emergency nurses. The results of these studies can be

found in Table 1.

3.3.1.Individualfactors

3.3.1.1.Demographiccharacteristics.In general popula-

tions, younger age was found to be related to a higher

risk of burnout.Genderwas also found to be predictiveof

burnout in several studies but the results were not

nor Hooper et al. (2010) found significant relationships

betweenage,seniorityor genderand burnout dimensions.

3.3.1.2.Personalitycharacteristics.In the job stress litera-

ture on a broad set of populations,personalitycharacter-

istics, such as neuroticism, extraversion,agreeableness,

conscientiousnessand openness,also called ‘The Big Five’

personalitytraits (McCraeand Costa,1987),were found to

be associatedwith burnout (Zellars et al., 2000; Bakker

et al., 2006; Swider and Zimmerman,2010; Shimizutani

et al., 2008; Maslach et al., 2001).Low levels of hardiness

(less involvement in daily activities, a lower sense of

control overevents,and lessopennessto change)were also

related to higher levels of emotionalexhaustion(Maslach

et al., 2001).

In the ER-nursesstudies,includedin the presentreview,

personalitycharacteristicswere not frequentlyreportedas

potential determinantsof burnout. Alexanderet al. found

personswith a hardy personalityto view eventsmore as

meaningful (leading to higher levels of commitment),

challengingand under their control than their colleagues.

This studyreportsa strongnegativecorrelationbetweenthe

level of commitment,perceivedcontrol,job challengeand

emotionalexhaustion.Also for depersonalizationnegative

relationshipswere found with commitment and control.

Personal accomplishmentwas positively related to com-

mitment,controlandchallenge(AlexanderandKlein,2001).

Lack of flexibility, stubbornness,judgmentalbehaviorand

difficulty in adaptation were also reported as potential

determinantsof burnout (Walsh et al., 1998).

3.3.1.3.Copingstrategies.In studies on occupationalwell-

being in nurses,copingstrategieswere found to be related

to well-being and performance.Active problem focused

copingwas found to be relatedto lower levelsof emotional

exhaustionand depersonalizationand to higher personal

accomplishment.Passiveavoidant and emotional coping

strategies,especially when used alone or as a dominant

mode of coping, were found to be ineffectivein dealing

with stress(Shirey,2006;Shimizutaniet al.,2008;Maslach

et al., 2001; Semmer,2003).

In the selectedstudiesin ER-nurses,Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2001) found significant positive correlationsbe-

tween avoidant behavior and emotional exhaustionand

depersonalization and reported a negative correlation

with personal accomplishment.They state that avoidant

behavior after exposureto traumatic eventsis not a good

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx8

values for all these dimensions.

For the purpose of this study and with the aim to

estimatethe prevalenceof burnout amongER-nurses,we

used reverse sampling statistics (Minitabß 16.2.4,Penn-

sylvania) to generaterandom data for the seven studies

that reportedonly meansand standarddeviationsfor the

MBI-dimensions. For this reverse sampling method we

assumed,based on previous findings, that the reported

data of the burnout dimensionshad a normal distribution

(Schaufeliet al., 2002; Langelaanet al., 2007; Camposand

Maroco, 2012). The cut off scores for the respective

instruments were used to determine the percentageof

respondentswith high emotionalexhaustion,high deper-

sonalization and low personal accomplishment. The

results of these analyses are reported in Table 3. A

weighted averagepercentageof casenessfor emotional

exhaustion, depersonalizationand lack of personal ac-

complishmentwas calculated.Basedupon the scores for

the reversely generated samples and the originally

reported cut off percentages,on average 25.9% of the

respondents exceededthe cut off scores for emotional

exhaustion,34.8%exceededthe cut offs for depersonali-

zation and 27.2%exceededthe cut off for lack of personal

accomplishment.Consideringthe generalconsensusthat

emotional exhaustion is the core dimension of burnout,

this review shows that 26% of the respondents in the

selectedstudies suffered from burnout.

3.3. Determinantsfor burnoutin emergencynurses

The studies that were included in this review used a

varietyof determinants.For the purposeof this review we

categorized these determinants in terms of ‘individual

factors’and ‘job related factors’,basedon an overview of

burnout by Maslach et al. (2001). For each category,a

generalintroduction is given,followed by the description

of the results for the selected studies on burnout in

emergency nurses. The results of these studies can be

found in Table 1.

3.3.1.Individualfactors

3.3.1.1.Demographiccharacteristics.In general popula-

tions, younger age was found to be related to a higher

risk of burnout.Genderwas also found to be predictiveof

burnout in several studies but the results were not

nor Hooper et al. (2010) found significant relationships

betweenage,seniorityor genderand burnout dimensions.

3.3.1.2.Personalitycharacteristics.In the job stress litera-

ture on a broad set of populations,personalitycharacter-

istics, such as neuroticism, extraversion,agreeableness,

conscientiousnessand openness,also called ‘The Big Five’

personalitytraits (McCraeand Costa,1987),were found to

be associatedwith burnout (Zellars et al., 2000; Bakker

et al., 2006; Swider and Zimmerman,2010; Shimizutani

et al., 2008; Maslach et al., 2001).Low levels of hardiness

(less involvement in daily activities, a lower sense of

control overevents,and lessopennessto change)were also

related to higher levels of emotionalexhaustion(Maslach

et al., 2001).

In the ER-nursesstudies,includedin the presentreview,

personalitycharacteristicswere not frequentlyreportedas

potential determinantsof burnout. Alexanderet al. found

personswith a hardy personalityto view eventsmore as

meaningful (leading to higher levels of commitment),

challengingand under their control than their colleagues.

This studyreportsa strongnegativecorrelationbetweenthe

level of commitment,perceivedcontrol,job challengeand

emotionalexhaustion.Also for depersonalizationnegative

relationshipswere found with commitment and control.

Personal accomplishmentwas positively related to com-

mitment,controlandchallenge(AlexanderandKlein,2001).

Lack of flexibility, stubbornness,judgmentalbehaviorand

difficulty in adaptation were also reported as potential

determinantsof burnout (Walsh et al., 1998).

3.3.1.3.Copingstrategies.In studies on occupationalwell-

being in nurses,copingstrategieswere found to be related

to well-being and performance.Active problem focused

copingwas found to be relatedto lower levelsof emotional

exhaustionand depersonalizationand to higher personal

accomplishment.Passiveavoidant and emotional coping

strategies,especially when used alone or as a dominant

mode of coping, were found to be ineffectivein dealing

with stress(Shirey,2006;Shimizutaniet al.,2008;Maslach

et al., 2001; Semmer,2003).

In the selectedstudiesin ER-nurses,Van der Ploeg and

Kleber (2001) found significant positive correlationsbe-

tween avoidant behavior and emotional exhaustionand

depersonalization and reported a negative correlation

with personal accomplishment.They state that avoidant

behavior after exposureto traumatic eventsis not a good

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx8

In none of the studies in ER-nurses,included in this

review, job attitudesand goal settingwere investigatedas

a predictor of burnout in ER nurses.

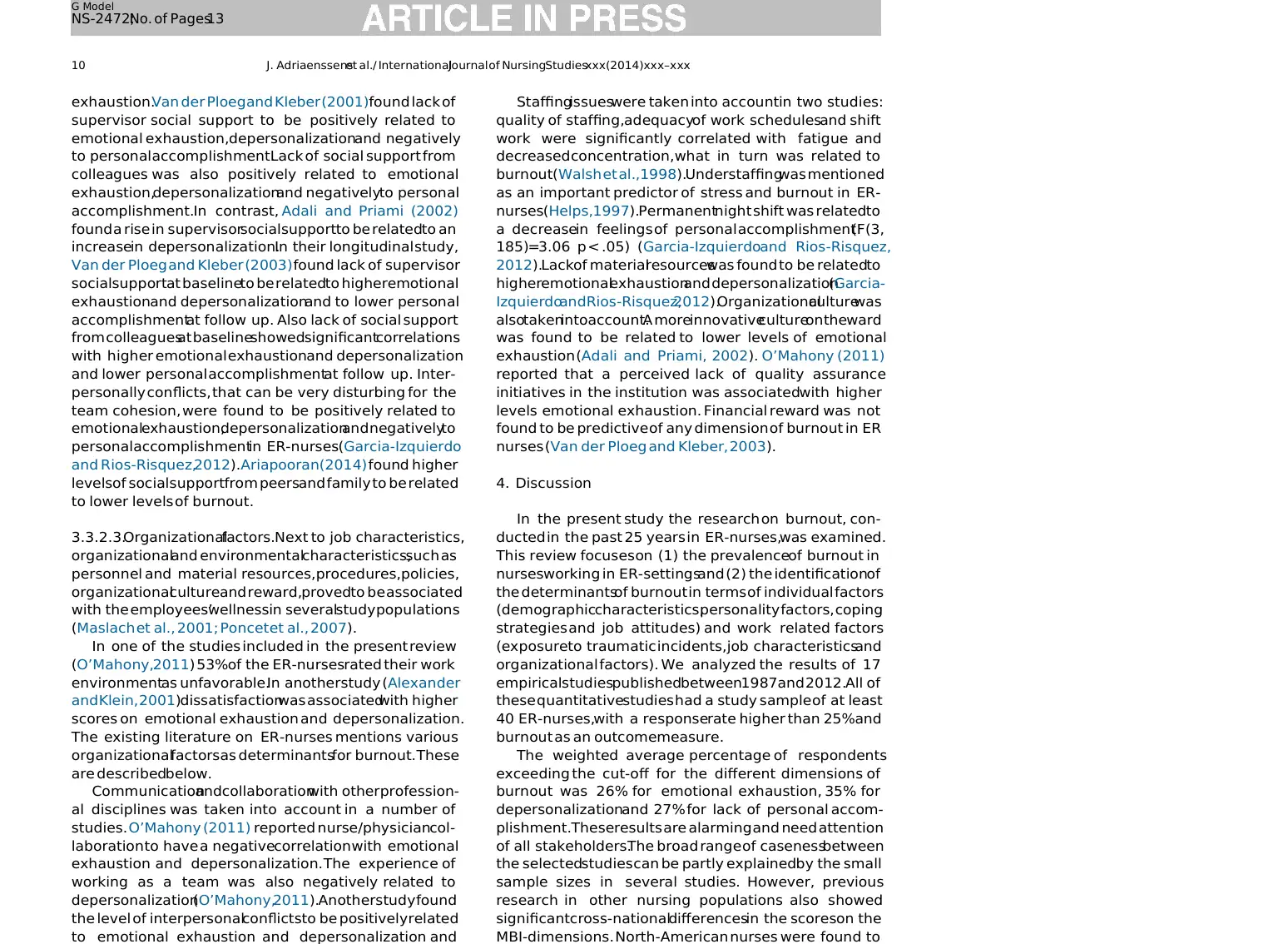

3.3.2.Work relatedfactors

3.3.2.1.Exposureto traumatic events.Repetitive profes-

sional exposureto traumaticevents,such as confrontation

with severe injuries, death, suicide, aggression and

suffering,was reported to be related to the development

of post-traumaticstress syndrome(PTSD) and burnout in

various nurses’populations (Donnelly and Siebert,2009;

Mealer et al., 2009; Collins and Long, 2003).

In one of the studies included in the present review,

Alexanderand Klein (2001) reported that ER-nurseswho

were exposedto traumaticeventsin the previous6 months

had higher levels of casenessfor high emotional exhaus-

tion (23%vs. 5%,p =.03) and high depersonalization(32%

vs. 0%,p =.003)but they found no differencesfor caseness

of low personal accomplishment(33% vs. 35%,p =.89),

comparedto non-exposedER-nurses.They reported that

69%of the exposedER-nursesmentionedthat they ‘never’

had sufficient time to recover emotionally between

traumatic events (Alexander and Klein, 2001). Van der

Ploeg and Kleber (2001) found the number of traumatic

eventsto be positively correlatedto posttraumaticstress

symptoms,emotional exhaustionand depersonalization.

In their longitudinal study (2003) they found a positive

long term relationshipbetween frequencyof exposureat

baselineand emotionalexhaustionand depersonalization

at follow up. Garcia-Izquierdo and Rios-Risquez (2012)

reported a positive correlation between frequency of

confrontation with death and suffering and emotional

exhaustion.Bernaldo-De-Quiroset al. (2014)found nurses

who were exposed more frequently to violence (insults,

threats and physical violence) to report higher levels of

emotional exhaustionand depersonalization.

3.3.2.2.Job characteristics.One of the most popular theo-

retical occupational stress models is the Job Demand

Control Support Model (JDCS),developedby Karasekand

Theorell (1990). This model defines three dimensions as

predictorsof occupationalstress:‘job demand’as a burden

and ‘job control’and ‘socialsupport’as potentialresources

or buffers.Job demandis definedas the psychologicalwork

load in terms of time pressure,role conflict and quantita-

tive workload. Job control, also called decision latitude,is

sub-dimensions:socialsupportprovidedby the colleagues

or co-workers and social support provided by the

supervisor. Previous research in multiple occupational

groups showed relationshipsbetween JDCS-variablesand

burnout (Mark and Smith, 2008). Researchin nurses also

revealedrelationshipsbetween JDCS-variablesand burn-

out (Ha¨usser et al., 2010; Gelsemaet al., 2006). In those

studies,burnout was seen as an end-stageof adaptation

failure resulting from the long-term imbalance between

job demandsand resources(McSherry et al., 2012).

A number of studies, included in this review on ER-

nursesreport JCDS-variablesto be relatedto burnout.The

results are describedby JDCS-variable.

Psychologicaldemands(work/time pressure)was found

to be related to burnout and its dimensions. Adali and

Priami (2002) found work pressure to be a significant

positivepredictorfor emotionalexhaustion.Escriba-Agu¨ir

and Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007) found high psychological

demands to be predictive of high levels of emotional

exhaustion. Garcia-Izquierdo and Rios-Risquez (2012)

found excessive workload to be related to higher

emotional exhaustion and depersonalizationbut found

no relationship with personal accomplishment.Van der

Ploeg and Kleber (2001) report positive correlations

between emotional demands and emotional exhaustion

and depersonalizationbut did not find any relationship

with personalaccomplishment.In their longitudinalstudy

emotionaldemandsat baselinewere positively related to

emotional exhaustionand depersonalizationat follow-up

(Van der Ploeg and Kleber, 2003). One study reported an

inverserelationship:an increasein the job demandscore

was related to a decreasein the general burnout score

(r =0.34,p < .01) (Sorour and El-Maksoud,2012).Physical

demandsin ER-nurses showed no relationship (dynamic

nor static) with burnout in the study of Escriba-Agu¨ir and

Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007).However, this variable was found to

be predictivefor higher emotional exhaustionin longitu-

dinal analysis(Van der Ploeg and Kleber, 2003).

Thelevelof JobControlwas foundto be negativelyrelated

to emotional exhaustionand depersonalizationand posi-

tively relatedto personalaccomplishment(Alexanderand

Klein, 2001). In the study of Browning et al. (2007),

perceived control moderated the relationship between

work stressorson the one hand and emotionalexhaustion

and depersonalizationon the otherhand.Escriba-Agu¨ir and

Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007) did not find a relationship between

controland emotionalexhaustion.Van der Ploegand Kleber

G Model

NS-2472;No. of Pages13

J. Adriaenssenset al./ InternationalJournal of NursingStudiesxxx (2014)xxx–xxx 9

review, job attitudesand goal settingwere investigatedas

a predictor of burnout in ER nurses.

3.3.2.Work relatedfactors

3.3.2.1.Exposureto traumatic events.Repetitive profes-

sional exposureto traumaticevents,such as confrontation

with severe injuries, death, suicide, aggression and

suffering,was reported to be related to the development

of post-traumaticstress syndrome(PTSD) and burnout in

various nurses’populations (Donnelly and Siebert,2009;

Mealer et al., 2009; Collins and Long, 2003).

In one of the studies included in the present review,

Alexanderand Klein (2001) reported that ER-nurseswho

were exposedto traumaticeventsin the previous6 months

had higher levels of casenessfor high emotional exhaus-

tion (23%vs. 5%,p =.03) and high depersonalization(32%

vs. 0%,p =.003)but they found no differencesfor caseness

of low personal accomplishment(33% vs. 35%,p =.89),

comparedto non-exposedER-nurses.They reported that

69%of the exposedER-nursesmentionedthat they ‘never’

had sufficient time to recover emotionally between

traumatic events (Alexander and Klein, 2001). Van der

Ploeg and Kleber (2001) found the number of traumatic

eventsto be positively correlatedto posttraumaticstress

symptoms,emotional exhaustionand depersonalization.

In their longitudinal study (2003) they found a positive

long term relationshipbetween frequencyof exposureat

baselineand emotionalexhaustionand depersonalization

at follow up. Garcia-Izquierdo and Rios-Risquez (2012)

reported a positive correlation between frequency of

confrontation with death and suffering and emotional

exhaustion.Bernaldo-De-Quiroset al. (2014)found nurses

who were exposed more frequently to violence (insults,

threats and physical violence) to report higher levels of

emotional exhaustionand depersonalization.

3.3.2.2.Job characteristics.One of the most popular theo-

retical occupational stress models is the Job Demand

Control Support Model (JDCS),developedby Karasekand

Theorell (1990). This model defines three dimensions as

predictorsof occupationalstress:‘job demand’as a burden

and ‘job control’and ‘socialsupport’as potentialresources

or buffers.Job demandis definedas the psychologicalwork

load in terms of time pressure,role conflict and quantita-

tive workload. Job control, also called decision latitude,is

sub-dimensions:socialsupportprovidedby the colleagues

or co-workers and social support provided by the

supervisor. Previous research in multiple occupational

groups showed relationshipsbetween JDCS-variablesand

burnout (Mark and Smith, 2008). Researchin nurses also

revealedrelationshipsbetween JDCS-variablesand burn-

out (Ha¨usser et al., 2010; Gelsemaet al., 2006). In those

studies,burnout was seen as an end-stageof adaptation

failure resulting from the long-term imbalance between

job demandsand resources(McSherry et al., 2012).

A number of studies, included in this review on ER-

nursesreport JCDS-variablesto be relatedto burnout.The

results are describedby JDCS-variable.

Psychologicaldemands(work/time pressure)was found

to be related to burnout and its dimensions. Adali and

Priami (2002) found work pressure to be a significant

positivepredictorfor emotionalexhaustion.Escriba-Agu¨ir

and Pe´rez-Hoyos (2007) found high psychological

demands to be predictive of high levels of emotional

exhaustion. Garcia-Izquierdo and Rios-Risquez (2012)

found excessive workload to be related to higher

emotional exhaustion and depersonalizationbut found

no relationship with personal accomplishment.Van der

Ploeg and Kleber (2001) report positive correlations

between emotional demands and emotional exhaustion

and depersonalizationbut did not find any relationship

with personalaccomplishment.In their longitudinalstudy

emotionaldemandsat baselinewere positively related to

emotional exhaustionand depersonalizationat follow-up

(Van der Ploeg and Kleber, 2003). One study reported an

inverserelationship:an increasein the job demandscore

was related to a decreasein the general burnout score

(r =0.34,p < .01) (Sorour and El-Maksoud,2012).Physical

demandsin ER-nurses showed no relationship (dynamic