Examining CAMH's Cannabis Policy Framework: A Public Health Approach

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/14

|22

|8721

|488

Report

AI Summary

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Cannabis Policy Framework from October 2014 presents a comprehensive analysis of cannabis use in Canada, its associated health risks, and the need for legal reform. The report highlights that while cannabis use carries significant health risks, particularly for frequent users and those who start at a young age, criminalization exacerbates these harms. CAMH advocates for a public health approach focused on high-risk users, similar to strategies used for alcohol and tobacco, and argues that legalization combined with strict, health-focused regulation offers the best opportunity to reduce harms associated with cannabis use. The framework emphasizes the importance of finding the right balance of regulations and effectively implementing them to ensure public health and safety, while protecting vulnerable populations from cannabis-related harms. The report concludes that a shift from prohibition to regulation is necessary to address the realities of cannabis use in Canada and mitigate its negative consequences.

1

Centre for Addiction and

Mental Health

1001 Queen St. West

Toronto, Ontario

Canada M6J 1H4

Tel: 416.535.8501

www.camh.ca

A PAHO / WHO

Collaborating Centre

Fully affiliated with the

University of Toronto

CANNABIS POLICY FRAMEWORK

October 2014

Centre for Addiction and

Mental Health

1001 Queen St. West

Toronto, Ontario

Canada M6J 1H4

Tel: 416.535.8501

www.camh.ca

A PAHO / WHO

Collaborating Centre

Fully affiliated with the

University of Toronto

CANNABIS POLICY FRAMEWORK

October 2014

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

0

Table of contents

Executive summary ................................................................................................................. 1

What we know ........................................................................................................................ 2

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in Canada ..................................................... 2

Cannabis use carries health risks ................................................................................................ 3

Cannabis related harm is concentrated among a limited group of high risk users ................... 5‐ ‐

Criminalization of cannabis use causes additional harms, without dissuading it ...................... 6

Legal reform of cannabis control is needed ............................................................................... 7

Why legalize and regulate? ...................................................................................................... 8

Decriminalization: a half measure .............................................................................................. 9

Legalization: an opportunity for evidence based regulation ................................................... 11‐

Moving from prohibition to regulation ....................................................................................... 12

Principles to guide health focused cannabis control ................................................................ 12‐

Potential risks, and how to mitigate them ............................................................................... 13

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 16

About CAMH ......................................................................................................................... 17

References............................................................................................................................. 18

Table of contents

Executive summary ................................................................................................................. 1

What we know ........................................................................................................................ 2

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in Canada ..................................................... 2

Cannabis use carries health risks ................................................................................................ 3

Cannabis related harm is concentrated among a limited group of high risk users ................... 5‐ ‐

Criminalization of cannabis use causes additional harms, without dissuading it ...................... 6

Legal reform of cannabis control is needed ............................................................................... 7

Why legalize and regulate? ...................................................................................................... 8

Decriminalization: a half measure .............................................................................................. 9

Legalization: an opportunity for evidence based regulation ................................................... 11‐

Moving from prohibition to regulation ....................................................................................... 12

Principles to guide health focused cannabis control ................................................................ 12‐

Potential risks, and how to mitigate them ............................................................................... 13

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 16

About CAMH ......................................................................................................................... 17

References............................................................................................................................. 18

1

Executive summary

Cannabis is a favourite recreational drug of Canadians, along with alcohol and tobacco. Like

those drugs, cannabis (popularly known as marijuana) is associated with a variety of health

harms. Unlike those drugs, cannabis is illegal, prohibited under the same federal and

international drug statutes as heroin and cocaine.

The landscape of cannabis policy is changing. The Netherlands, Portugal, and more recently

Uruguay and US states Colorado and Washington have reformed their approach to cannabis

control. Here in Canada, changes to the rules of the federal Medical Use of Marijuana program

are expected to lead to an increase in the number of registered users over the next few years.

Public support for reform of Canada’s cannabis laws continues to grow. Meanwhile, we

continue to improve our understanding of the health risks of cannabis use.

As Canada’s leading hospital for mental illness, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

(CAMH) offers evidence based conclusions about cannabis and measures aimed at reducing‐

harm. CAMH has reviewed the evidence on cannabis control and drawn the following

conclusions:

Cannabis use carries significant health risks, especially for people who use it frequently

and/or begin to use it at an early age.

Criminalization heightens these health harms and causes social harms.

A public health approach focused on high risk users and practices – similar to the‐

approach favoured with alcohol and tobacco – allows for more control over the risk

factors associated with cannabis related harm.‐

From these conclusions follows another:

Legalization, combined with strict health focused regulation, provides an opportunity to‐

reduce the harms associated with cannabis use.

This approach is not without risks. A legal and unregulated or under regulated approach may‐

lead to an increase in cannabis use. Finding the right balance of regulations and effectively

implementing and enforcing them is the key to ensuring that a legalization approach results in a

net benefit to public health and safety while protecting those who are vulnerable to cannabis‐

related harms.

CAMH neither makes a moral statement on cannabis nor encourages its use. Despite the

prohibition of cannabis, more than one third of young adults are users, and our current

approach exacerbates the harms. It’s time to reconsider our approach to cannabis control.

Executive summary

Cannabis is a favourite recreational drug of Canadians, along with alcohol and tobacco. Like

those drugs, cannabis (popularly known as marijuana) is associated with a variety of health

harms. Unlike those drugs, cannabis is illegal, prohibited under the same federal and

international drug statutes as heroin and cocaine.

The landscape of cannabis policy is changing. The Netherlands, Portugal, and more recently

Uruguay and US states Colorado and Washington have reformed their approach to cannabis

control. Here in Canada, changes to the rules of the federal Medical Use of Marijuana program

are expected to lead to an increase in the number of registered users over the next few years.

Public support for reform of Canada’s cannabis laws continues to grow. Meanwhile, we

continue to improve our understanding of the health risks of cannabis use.

As Canada’s leading hospital for mental illness, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

(CAMH) offers evidence based conclusions about cannabis and measures aimed at reducing‐

harm. CAMH has reviewed the evidence on cannabis control and drawn the following

conclusions:

Cannabis use carries significant health risks, especially for people who use it frequently

and/or begin to use it at an early age.

Criminalization heightens these health harms and causes social harms.

A public health approach focused on high risk users and practices – similar to the‐

approach favoured with alcohol and tobacco – allows for more control over the risk

factors associated with cannabis related harm.‐

From these conclusions follows another:

Legalization, combined with strict health focused regulation, provides an opportunity to‐

reduce the harms associated with cannabis use.

This approach is not without risks. A legal and unregulated or under regulated approach may‐

lead to an increase in cannabis use. Finding the right balance of regulations and effectively

implementing and enforcing them is the key to ensuring that a legalization approach results in a

net benefit to public health and safety while protecting those who are vulnerable to cannabis‐

related harms.

CAMH neither makes a moral statement on cannabis nor encourages its use. Despite the

prohibition of cannabis, more than one third of young adults are users, and our current

approach exacerbates the harms. It’s time to reconsider our approach to cannabis control.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

2

What we know

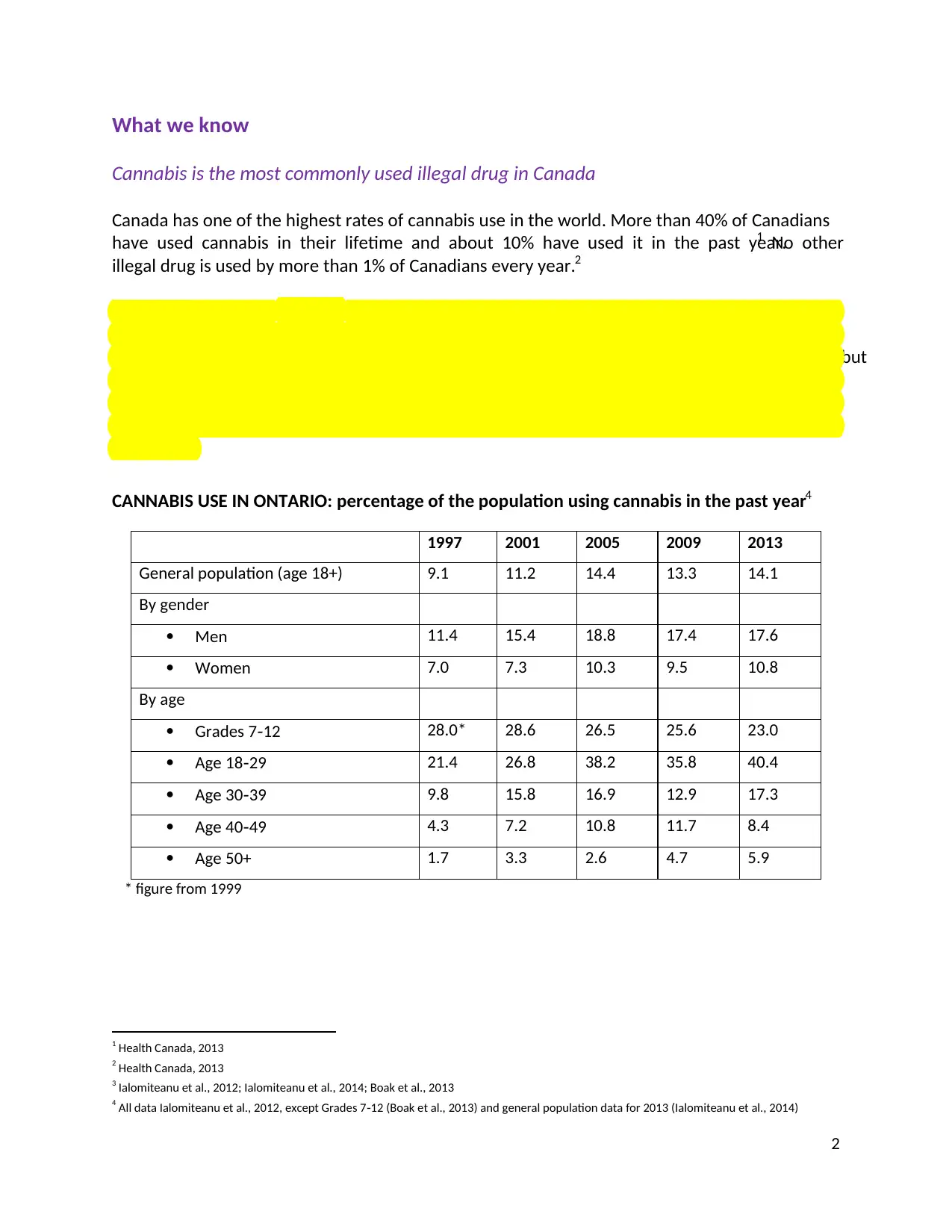

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in Canada

Canada has one of the highest rates of cannabis use in the world. More than 40% of Canadians

have used cannabis in their lifetime and about 10% have used it in the past year.1 No other

illegal drug is used by more than 1% of Canadians every year.2

Population surveys in Ontario3 indicate that 14% of adults and 23% of high school students used

cannabis in 2013. As shown in the table below, men are nearly 50% more likely to be past year‐

users than women. Cannabis use is most common among adolescents and young adults, but

half of the province’s users are age 30 or older. Between 1997 and 2005, cannabis use among

adults trended upward – particularly among 18 to 29 year olds – but has levelled off since then.‐

Among high school students there has been a steady and significant decrease in past year use‐

since 2003.

CANNABIS USE IN ONTARIO: percentage of the population using cannabis in the past year4

1997 2001 2005 2009 2013

General population (age 18+) 9.1 11.2 14.4 13.3 14.1

By gender

Men 11.4 15.4 18.8 17.4 17.6

Women 7.0 7.3 10.3 9.5 10.8

By age

Grades 7 12‐ 28.0* 28.6 26.5 25.6 23.0

Age 18 29‐ 21.4 26.8 38.2 35.8 40.4

Age 30 39‐ 9.8 15.8 16.9 12.9 17.3

Age 40 49‐ 4.3 7.2 10.8 11.7 8.4

Age 50+ 1.7 3.3 2.6 4.7 5.9

* figure from 1999

1 Health Canada, 2013

2 Health Canada, 2013

3 Ialomiteanu et al., 2012; Ialomiteanu et al., 2014; Boak et al., 2013

4 All data Ialomiteanu et al., 2012, except Grades 7 12 (Boak et al., 2013) and general population data for 2013 (Ialomiteanu et al., 2014)‐

What we know

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in Canada

Canada has one of the highest rates of cannabis use in the world. More than 40% of Canadians

have used cannabis in their lifetime and about 10% have used it in the past year.1 No other

illegal drug is used by more than 1% of Canadians every year.2

Population surveys in Ontario3 indicate that 14% of adults and 23% of high school students used

cannabis in 2013. As shown in the table below, men are nearly 50% more likely to be past year‐

users than women. Cannabis use is most common among adolescents and young adults, but

half of the province’s users are age 30 or older. Between 1997 and 2005, cannabis use among

adults trended upward – particularly among 18 to 29 year olds – but has levelled off since then.‐

Among high school students there has been a steady and significant decrease in past year use‐

since 2003.

CANNABIS USE IN ONTARIO: percentage of the population using cannabis in the past year4

1997 2001 2005 2009 2013

General population (age 18+) 9.1 11.2 14.4 13.3 14.1

By gender

Men 11.4 15.4 18.8 17.4 17.6

Women 7.0 7.3 10.3 9.5 10.8

By age

Grades 7 12‐ 28.0* 28.6 26.5 25.6 23.0

Age 18 29‐ 21.4 26.8 38.2 35.8 40.4

Age 30 39‐ 9.8 15.8 16.9 12.9 17.3

Age 40 49‐ 4.3 7.2 10.8 11.7 8.4

Age 50+ 1.7 3.3 2.6 4.7 5.9

* figure from 1999

1 Health Canada, 2013

2 Health Canada, 2013

3 Ialomiteanu et al., 2012; Ialomiteanu et al., 2014; Boak et al., 2013

4 All data Ialomiteanu et al., 2012, except Grades 7 12 (Boak et al., 2013) and general population data for 2013 (Ialomiteanu et al., 2014)‐

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3

60% of past year adult cannabis users in Ontario use it at least once a month,‐ 5 and about 27%,

or nearly 4% of the total adult population, use it every day. 6 From other jurisdictions we know

that a small proportion of cannabis users is responsible for the bulk of consumption; it is

estimated that 20% of users account for 80 90% of consumption.‐ 7

Most people who use cannabis do not use other illegal drugs, and cannabis use alone does not

increase the likelihood that a person will progress to using other illegal substances.8

Public opinion on cannabis control has shifted considerably in the past decade. Ten years ago

about half of Canadians believed cannabis use should be decriminalized or legalized; today,

about two thirds of Canadians hold this view.9

Cannabis use carries health risks

Cannabis is not a benign substance. Its health harms increase with intensity of use. Particularly

when used frequently (daily or near daily),‐ cannabis is associated with increased risk of

problems with cognitive and psychomotor functioning, respiratory problems, dependence, and

mental health problems.

Problems with cognitive and psychomotor functioning

Cannabis use is known to negatively affect memory, attention span, and psychomotor

performance. Frequent use may reduce motivation and learning performance, and work or

study can be negatively affected as a result. 10 In adults, these changes are not generally

permanent; effects usually dissipate several weeks after use is discontinued.

Most significant from a public health perspective is the impact of cannabis use on the skills

necessary for safe driving and the substantial increase of risk of motor vehicle accidents.‐ 11 In

Ontario, an estimated 9% of licensed drivers aged 18 to 29 and 10% of those in grades 10 to 12

report having driven within an hour of using cannabis in the past year.12 Rates of cannabis‐

impaired driving exceed rates of alcohol impaired driving for both age groups. Although the‐

accident risk associated with cannabis impaired driving is significantly lower than that of‐

alcohol impaired driving, it is a serious concern: motor vehicle accidents due to impaired‐ ‐

driving are the main contribution of cannabis to Canada’s burden of disease and injury.

5 Ialomiteanu et al., 2014

6 Health Canada, 2013

7 Room et al., 2010

8 Room et al., 2010

9 National Post, 2013; Ottawa Citizen, 2014

10 Block et al., 2002; Pope et al., 1996

11 Hartman and Huestis, 2013; Hall and Degenhardt, 2009

12 Ialomiteanu et al., 2012; Boak et al., 2013

60% of past year adult cannabis users in Ontario use it at least once a month,‐ 5 and about 27%,

or nearly 4% of the total adult population, use it every day. 6 From other jurisdictions we know

that a small proportion of cannabis users is responsible for the bulk of consumption; it is

estimated that 20% of users account for 80 90% of consumption.‐ 7

Most people who use cannabis do not use other illegal drugs, and cannabis use alone does not

increase the likelihood that a person will progress to using other illegal substances.8

Public opinion on cannabis control has shifted considerably in the past decade. Ten years ago

about half of Canadians believed cannabis use should be decriminalized or legalized; today,

about two thirds of Canadians hold this view.9

Cannabis use carries health risks

Cannabis is not a benign substance. Its health harms increase with intensity of use. Particularly

when used frequently (daily or near daily),‐ cannabis is associated with increased risk of

problems with cognitive and psychomotor functioning, respiratory problems, dependence, and

mental health problems.

Problems with cognitive and psychomotor functioning

Cannabis use is known to negatively affect memory, attention span, and psychomotor

performance. Frequent use may reduce motivation and learning performance, and work or

study can be negatively affected as a result. 10 In adults, these changes are not generally

permanent; effects usually dissipate several weeks after use is discontinued.

Most significant from a public health perspective is the impact of cannabis use on the skills

necessary for safe driving and the substantial increase of risk of motor vehicle accidents.‐ 11 In

Ontario, an estimated 9% of licensed drivers aged 18 to 29 and 10% of those in grades 10 to 12

report having driven within an hour of using cannabis in the past year.12 Rates of cannabis‐

impaired driving exceed rates of alcohol impaired driving for both age groups. Although the‐

accident risk associated with cannabis impaired driving is significantly lower than that of‐

alcohol impaired driving, it is a serious concern: motor vehicle accidents due to impaired‐ ‐

driving are the main contribution of cannabis to Canada’s burden of disease and injury.

5 Ialomiteanu et al., 2014

6 Health Canada, 2013

7 Room et al., 2010

8 Room et al., 2010

9 National Post, 2013; Ottawa Citizen, 2014

10 Block et al., 2002; Pope et al., 1996

11 Hartman and Huestis, 2013; Hall and Degenhardt, 2009

12 Ialomiteanu et al., 2012; Boak et al., 2013

4

Respiratory problems

Like tobacco, cannabis smoke contains tar and other known cancer causing agents. Regular,‐

long term cannabis smoking is linked to bronchitis and cancer.‐ 13 Cannabis smokers often hold

unfiltered smoke in their lungs for maximum effect, which adds to these risks. About half of

past year users also smoke tobacco and it is likely that tobacco smoking contributes greatly to –‐

or is the primary cause of – many of these respiratory problems.14

Dependence

About 9% of cannabis users develop dependence. 15 People who develop cannabis dependence

may have difficulty quitting or cutting down and may persist in using it despite negative

consequences; those who stop suddenly may experience mild withdrawal symptoms including

irritability, anxiety, upset stomach, loss of appetite, disturbed sleep, and depression.16 Long‐

term frequent users have a higher risk of dependence than occasional users. By way of

comparison, the estimated probability of developing dependence is 68% for nicotine, 23% for

alcohol, and 21% for cocaine.17

Mental health problems

Frequent cannabis use has been found by many studies to be associated with mental illness.18 It

is thought to increase the likelihood of mental illness in people with a pre existing vulnerability‐

to it and to exacerbate symptoms in people already experiencing mental illness.19 Even

occasional use can increase these risks: it has been estimated that cannabis users have a 40%

higher risk of psychosis than non users.‐ 20 Frequent users have an even higher risk – 50% to

200% higher than non users – indicating a possible dose response. High potency cannabis –‐ ‐

that is, cannabis with a high concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main

psychoactive component of cannabis – places users at higher risk of mental health problems

than low potency cannabis.‐ 21 This association between cannabis use and mental illness is

robust but not yet well understood. Causality has not been determined.22

13 Tetrault et al., 2007

14 Fischer et al., 2011

15 Lopez Quintero et al., 2011‐

16 Anthony, 2006; Kalant, 2004

17 Lopez Quintero et al., 2011‐

18 For a summary see Volkow et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 2011.

19 McLaren et al., 2009; Hall et al., 2004

20 Moore et al., 2007

21 Di Forti et al., 2009

22 McLaren et al., 2009

Respiratory problems

Like tobacco, cannabis smoke contains tar and other known cancer causing agents. Regular,‐

long term cannabis smoking is linked to bronchitis and cancer.‐ 13 Cannabis smokers often hold

unfiltered smoke in their lungs for maximum effect, which adds to these risks. About half of

past year users also smoke tobacco and it is likely that tobacco smoking contributes greatly to –‐

or is the primary cause of – many of these respiratory problems.14

Dependence

About 9% of cannabis users develop dependence. 15 People who develop cannabis dependence

may have difficulty quitting or cutting down and may persist in using it despite negative

consequences; those who stop suddenly may experience mild withdrawal symptoms including

irritability, anxiety, upset stomach, loss of appetite, disturbed sleep, and depression.16 Long‐

term frequent users have a higher risk of dependence than occasional users. By way of

comparison, the estimated probability of developing dependence is 68% for nicotine, 23% for

alcohol, and 21% for cocaine.17

Mental health problems

Frequent cannabis use has been found by many studies to be associated with mental illness.18 It

is thought to increase the likelihood of mental illness in people with a pre existing vulnerability‐

to it and to exacerbate symptoms in people already experiencing mental illness.19 Even

occasional use can increase these risks: it has been estimated that cannabis users have a 40%

higher risk of psychosis than non users.‐ 20 Frequent users have an even higher risk – 50% to

200% higher than non users – indicating a possible dose response. High potency cannabis –‐ ‐

that is, cannabis with a high concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main

psychoactive component of cannabis – places users at higher risk of mental health problems

than low potency cannabis.‐ 21 This association between cannabis use and mental illness is

robust but not yet well understood. Causality has not been determined.22

13 Tetrault et al., 2007

14 Fischer et al., 2011

15 Lopez Quintero et al., 2011‐

16 Anthony, 2006; Kalant, 2004

17 Lopez Quintero et al., 2011‐

18 For a summary see Volkow et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 2011.

19 McLaren et al., 2009; Hall et al., 2004

20 Moore et al., 2007

21 Di Forti et al., 2009

22 McLaren et al., 2009

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

5

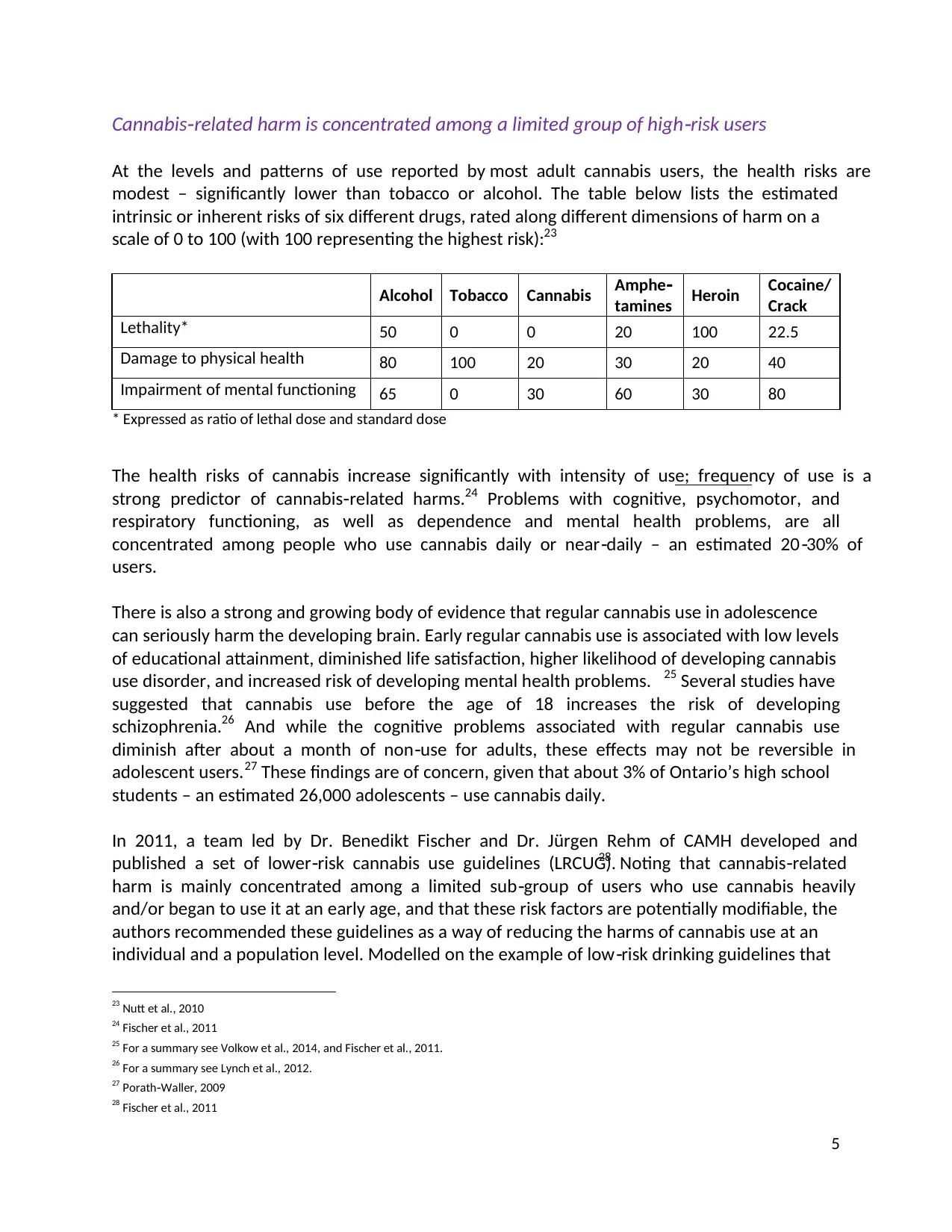

Cannabis related harm is concentrated among a limited group of high risk users‐ ‐

At the levels and patterns of use reported by most adult cannabis users, the health risks are

modest – significantly lower than tobacco or alcohol. The table below lists the estimated

intrinsic or inherent risks of six different drugs, rated along different dimensions of harm on a

scale of 0 to 100 (with 100 representing the highest risk):23

Alcohol Tobacco Cannabis Amphe‐

tamines Heroin Cocaine/

Crack

Lethality* 50 0 0 20 100 22.5

Damage to physical health 80 100 20 30 20 40

Impairment of mental functioning 65 0 30 60 30 80

* Expressed as ratio of lethal dose and standard dose

The health risks of cannabis increase significantly with intensity of use; frequency of use is a

strong predictor of cannabis related‐ harms.24 Problems with cognitive, psychomotor, and

respiratory functioning, as well as dependence and mental health problems, are all

concentrated among people who use cannabis daily or near daily – an estimated 20 30% of‐ ‐

users.

There is also a strong and growing body of evidence that regular cannabis use in adolescence

can seriously harm the developing brain. Early regular cannabis use is associated with low levels

of educational attainment, diminished life satisfaction, higher likelihood of developing cannabis

use disorder, and increased risk of developing mental health problems. 25 Several studies have

suggested that cannabis use before the age of 18 increases the risk of developing

schizophrenia.26 And while the cognitive problems associated with regular cannabis use

diminish after about a month of non use for adults, these effects may not be reversible in‐

adolescent users.27 These findings are of concern, given that about 3% of Ontario’s high school

students – an estimated 26,000 adolescents – use cannabis daily.

In 2011, a team led by Dr. Benedikt Fischer and Dr. Jürgen Rehm of CAMH developed and

published a set of lower risk cannabis use guidelines (LRCUG).‐ 28 Noting that cannabis related‐

harm is mainly concentrated among a limited sub group of users who use cannabis heavily‐

and/or began to use it at an early age, and that these risk factors are potentially modifiable, the

authors recommended these guidelines as a way of reducing the harms of cannabis use at an

individual and a population level. Modelled on the example of low risk drinking guidelines that‐

23 Nutt et al., 2010

24 Fischer et al., 2011

25 For a summary see Volkow et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 2011.

26 For a summary see Lynch et al., 2012.

27 Porath Waller, 2009‐

28 Fischer et al., 2011

Cannabis related harm is concentrated among a limited group of high risk users‐ ‐

At the levels and patterns of use reported by most adult cannabis users, the health risks are

modest – significantly lower than tobacco or alcohol. The table below lists the estimated

intrinsic or inherent risks of six different drugs, rated along different dimensions of harm on a

scale of 0 to 100 (with 100 representing the highest risk):23

Alcohol Tobacco Cannabis Amphe‐

tamines Heroin Cocaine/

Crack

Lethality* 50 0 0 20 100 22.5

Damage to physical health 80 100 20 30 20 40

Impairment of mental functioning 65 0 30 60 30 80

* Expressed as ratio of lethal dose and standard dose

The health risks of cannabis increase significantly with intensity of use; frequency of use is a

strong predictor of cannabis related‐ harms.24 Problems with cognitive, psychomotor, and

respiratory functioning, as well as dependence and mental health problems, are all

concentrated among people who use cannabis daily or near daily – an estimated 20 30% of‐ ‐

users.

There is also a strong and growing body of evidence that regular cannabis use in adolescence

can seriously harm the developing brain. Early regular cannabis use is associated with low levels

of educational attainment, diminished life satisfaction, higher likelihood of developing cannabis

use disorder, and increased risk of developing mental health problems. 25 Several studies have

suggested that cannabis use before the age of 18 increases the risk of developing

schizophrenia.26 And while the cognitive problems associated with regular cannabis use

diminish after about a month of non use for adults, these effects may not be reversible in‐

adolescent users.27 These findings are of concern, given that about 3% of Ontario’s high school

students – an estimated 26,000 adolescents – use cannabis daily.

In 2011, a team led by Dr. Benedikt Fischer and Dr. Jürgen Rehm of CAMH developed and

published a set of lower risk cannabis use guidelines (LRCUG).‐ 28 Noting that cannabis related‐

harm is mainly concentrated among a limited sub group of users who use cannabis heavily‐

and/or began to use it at an early age, and that these risk factors are potentially modifiable, the

authors recommended these guidelines as a way of reducing the harms of cannabis use at an

individual and a population level. Modelled on the example of low risk drinking guidelines that‐

23 Nutt et al., 2010

24 Fischer et al., 2011

25 For a summary see Volkow et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 2011.

26 For a summary see Lynch et al., 2012.

27 Porath Waller, 2009‐

28 Fischer et al., 2011

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

6

have been introduced in Canada and elsewhere, this proposal for LRCUG can be summarized as

follows:

Although abstinence is the only way to completely avoid the health risks of cannabis use,

for those who do use it, the risks are expected to be reduced if:

use is delayed until early adulthood

frequent (daily or near daily) use is avoided‐

users shift away from smoking cannabis towards less harmful (smokeless) delivery

systems such as vaporizers

less potent products are used, or THC dose is titrated

driving is avoided for 3 to 4 hours after use, or longer if needed

people with higher risk of cannabis related problems (e.g. people with a personal or‐

family history of psychosis, people with cardiovascular problems, and pregnant

women) abstain altogether

These guidelines have been endorsed by a number of organizations including CAMH and the

Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) as an educational means of reducing high risk‐

cannabis uses and practices.

Criminalization of cannabis use causes additional harms, without dissuading it

In Canada criminal law governs the production and possession of cannabis via the Controlled

Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Recreational cannabis users must either buy it on the black

market or grow it themselves, both of which constitute production / trafficking offenses under

the CDSA. This prohibition introduces individual and social costs beyond the health risks.

Around 60,000 Canadians are arrested for simple possession of cannabis every year, accounting

for nearly 3% of all arrests. 29 The maximum sentence for first time offenders is a $1,000 fine‐

and six months in jail. At least 500,000 Canadians carry a criminal record for this offense, which

can significantly limit a person’s employment opportunities and place restrictions on their

ability to travel.30 The enforcement of cannabis laws is very costly: for 2002, the annual cost of

enforcing cannabis possession laws (including police, courts, and corrections) in Canada was

estimated at $1.2 billion.31

29 Statistics Canada, 2013

30 Erickson and Fischer, 1995

31 Rehm et al., 2006

have been introduced in Canada and elsewhere, this proposal for LRCUG can be summarized as

follows:

Although abstinence is the only way to completely avoid the health risks of cannabis use,

for those who do use it, the risks are expected to be reduced if:

use is delayed until early adulthood

frequent (daily or near daily) use is avoided‐

users shift away from smoking cannabis towards less harmful (smokeless) delivery

systems such as vaporizers

less potent products are used, or THC dose is titrated

driving is avoided for 3 to 4 hours after use, or longer if needed

people with higher risk of cannabis related problems (e.g. people with a personal or‐

family history of psychosis, people with cardiovascular problems, and pregnant

women) abstain altogether

These guidelines have been endorsed by a number of organizations including CAMH and the

Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) as an educational means of reducing high risk‐

cannabis uses and practices.

Criminalization of cannabis use causes additional harms, without dissuading it

In Canada criminal law governs the production and possession of cannabis via the Controlled

Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Recreational cannabis users must either buy it on the black

market or grow it themselves, both of which constitute production / trafficking offenses under

the CDSA. This prohibition introduces individual and social costs beyond the health risks.

Around 60,000 Canadians are arrested for simple possession of cannabis every year, accounting

for nearly 3% of all arrests. 29 The maximum sentence for first time offenders is a $1,000 fine‐

and six months in jail. At least 500,000 Canadians carry a criminal record for this offense, which

can significantly limit a person’s employment opportunities and place restrictions on their

ability to travel.30 The enforcement of cannabis laws is very costly: for 2002, the annual cost of

enforcing cannabis possession laws (including police, courts, and corrections) in Canada was

estimated at $1.2 billion.31

29 Statistics Canada, 2013

30 Erickson and Fischer, 1995

31 Rehm et al., 2006

7

The prohibition of cannabis and criminalization of its users does not deter people from

consuming it. The evidence on this point is clear: tougher penalties do not lead to lower rates of

cannabis use.32 In jurisdictions like Canada where cannabis use is prohibited, large proportions

of the population use it nonetheless – often at higher levels than jurisdictions with more

relaxed cannabis control regimes – exposing themselves to criminality and risking being caught

up in the criminal justice system. People who are already vulnerable are affected

disproportionately; evidence suggests that “police often use the charge of cannabis possession

as an easy way of harassing or making life difficult for marginalized populations.”33

Legal reform of cannabis control is needed

All available evidence indicates that criminalization of cannabis use is ineffective, costly, and

constitutes poor public policy. This viewpoint is far from new, having notably been articulated

in Canada by the federal government’s Le Dain Commission in 1972, the Senate in 1974, the

Canadian Bar Association in 1994, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse in 1998, CAMH in

2000, the Fraser Institute in 2001, the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs in 2002, the

Canadian Drug Policy Coalition in 2013, and the Canadian Public Health Association in 2014. The

case for change generally rests on four evidence based propositions:‐ 34

1) Prohibition has not succeeded in deterring cannabis use.

2) The risks and harms of cannabis are lower than those of tobacco or alcohol.

3) Cannabis can and should be separated from illicit drug markets, in which users are

exposed to other (more dangerous) illegal drugs.

4) The resources spent enforcing laws against personal cannabis use are better allocated

elsewhere.

It is clear from the evidence that Canada needs legal reform in order to implement a public

health approach to cannabis that reduces its harms to individuals and society.

32 Room et al., 2010

33 Room et al., 2010: 72

34 Room et al., 2010

The prohibition of cannabis and criminalization of its users does not deter people from

consuming it. The evidence on this point is clear: tougher penalties do not lead to lower rates of

cannabis use.32 In jurisdictions like Canada where cannabis use is prohibited, large proportions

of the population use it nonetheless – often at higher levels than jurisdictions with more

relaxed cannabis control regimes – exposing themselves to criminality and risking being caught

up in the criminal justice system. People who are already vulnerable are affected

disproportionately; evidence suggests that “police often use the charge of cannabis possession

as an easy way of harassing or making life difficult for marginalized populations.”33

Legal reform of cannabis control is needed

All available evidence indicates that criminalization of cannabis use is ineffective, costly, and

constitutes poor public policy. This viewpoint is far from new, having notably been articulated

in Canada by the federal government’s Le Dain Commission in 1972, the Senate in 1974, the

Canadian Bar Association in 1994, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse in 1998, CAMH in

2000, the Fraser Institute in 2001, the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs in 2002, the

Canadian Drug Policy Coalition in 2013, and the Canadian Public Health Association in 2014. The

case for change generally rests on four evidence based propositions:‐ 34

1) Prohibition has not succeeded in deterring cannabis use.

2) The risks and harms of cannabis are lower than those of tobacco or alcohol.

3) Cannabis can and should be separated from illicit drug markets, in which users are

exposed to other (more dangerous) illegal drugs.

4) The resources spent enforcing laws against personal cannabis use are better allocated

elsewhere.

It is clear from the evidence that Canada needs legal reform in order to implement a public

health approach to cannabis that reduces its harms to individuals and society.

32 Room et al., 2010

33 Room et al., 2010: 72

34 Room et al., 2010

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

8

Why legalize and regulate?

In Canada the government’s approach to substance use has been that it’s mainly a criminal

justice issue. Cannabis and other drugs are viewed through a law enforcement lens. There’s no

disputing that cannabis use can, in some cases and for some people, be harmful. It does not

follow that prohibition is the most sensible or healthy policy. As Room et al. point out, “In

modern societies, a finding of adverse effects does not settle the issue of the legal status of a

commodity; if it did, alcohol, automobiles, and stairways, for instance, would all be prohibited,

since use of each of these results in substantial casualties.”35

A public health approach to substance use treats it as a health issue – not a criminal one. Such

an approach is based on evidence informed policy and practice, addressing the underlying‐

determinants of health and putting health promotion and the prevention of death, disease,

injury, and disability as its central mission.36 It seeks to maximize benefit for the largest number

of people through a mix of population level policies and targeted interventions. This philosophy‐

guides Canadian approaches to alcohol and tobacco, and it should guide our approach to

cannabis as well:

“The [current] policy approach to cannabis is fundamentally different from current

approaches to other popular drugs like alcohol, where a public health approach instead

focuses on high risk users, risky use practices and settings, and especially on modifiable‐

risk factors, to reduce harms to individuals and society. Given that the majority of harms

related to cannabis use appear to occur in selected high risk users or in conjunction with‐

high risk use practices, a similar public health oriented approach to cannabis use should‐ ‐

be considered. Such an approach would rely on targeted and health oriented‐

interventions mainly aimed at those users at high risk for harms, and not criminalization

of use – and its limited effectiveness and undesirable side effects – as the main

intervention paradigm, therefore increasing benefits for society.”37

With a wide range of options for reforming cannabis control, the question before us is this:

What legal and regulatory approach can best reduce the risks of health and social harms

associated with cannabis use? For a detailed discussion of the range of possible reforms both

within and beyond the current international drug regime, see Room et al., 2010. This section

will discuss decriminalization (i.e. prohibition with civil rather than criminal penalties) and

legalization with strict regulation – and why the evidence favours the latter.

35 Room et al., 2010: 15

36 Canadian Public Health Association, 2014

37 Fischer et al., 2011: 324

Why legalize and regulate?

In Canada the government’s approach to substance use has been that it’s mainly a criminal

justice issue. Cannabis and other drugs are viewed through a law enforcement lens. There’s no

disputing that cannabis use can, in some cases and for some people, be harmful. It does not

follow that prohibition is the most sensible or healthy policy. As Room et al. point out, “In

modern societies, a finding of adverse effects does not settle the issue of the legal status of a

commodity; if it did, alcohol, automobiles, and stairways, for instance, would all be prohibited,

since use of each of these results in substantial casualties.”35

A public health approach to substance use treats it as a health issue – not a criminal one. Such

an approach is based on evidence informed policy and practice, addressing the underlying‐

determinants of health and putting health promotion and the prevention of death, disease,

injury, and disability as its central mission.36 It seeks to maximize benefit for the largest number

of people through a mix of population level policies and targeted interventions. This philosophy‐

guides Canadian approaches to alcohol and tobacco, and it should guide our approach to

cannabis as well:

“The [current] policy approach to cannabis is fundamentally different from current

approaches to other popular drugs like alcohol, where a public health approach instead

focuses on high risk users, risky use practices and settings, and especially on modifiable‐

risk factors, to reduce harms to individuals and society. Given that the majority of harms

related to cannabis use appear to occur in selected high risk users or in conjunction with‐

high risk use practices, a similar public health oriented approach to cannabis use should‐ ‐

be considered. Such an approach would rely on targeted and health oriented‐

interventions mainly aimed at those users at high risk for harms, and not criminalization

of use – and its limited effectiveness and undesirable side effects – as the main

intervention paradigm, therefore increasing benefits for society.”37

With a wide range of options for reforming cannabis control, the question before us is this:

What legal and regulatory approach can best reduce the risks of health and social harms

associated with cannabis use? For a detailed discussion of the range of possible reforms both

within and beyond the current international drug regime, see Room et al., 2010. This section

will discuss decriminalization (i.e. prohibition with civil rather than criminal penalties) and

legalization with strict regulation – and why the evidence favours the latter.

35 Room et al., 2010: 15

36 Canadian Public Health Association, 2014

37 Fischer et al., 2011: 324

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

9

Decriminalization: a half measure

Models of cannabis decriminalization vary greatly, but generally they involve removing

possession of small amounts of cannabis from the sphere of criminal law. Prohibition remains

the rule, but sanctions for possession and use of cannabis instead become civil violations

punishable by a small fine.

Evidence suggests that a decriminalization approach can reduce some of the adverse social

impacts of criminalization. 38 Removing criminal penalties for cannabis possession should result

in a reduction in both the number of people caught up in the criminal justice system and the

cost of enforcement, thus reducing the burden to individuals and to the legal system. There is

little evidence that decriminalization causes an increase in the consumption of cannabis or the

prevalence of cannabis dependence.39

In Portugal, possession and use of all drugs have been decriminalized since 2001. The

Portuguese model focuses on diversion: drug use is formally prohibited but authorities refer

users to a three person panel whose primary aim is to direct people with substance use‐

problems to treatment. These panels are also empowered to apply civil penalties such as fines.

Since the implementation of this system, Portugal has seen declines in substance misuse and in

drug related harm, a reduced burden on the criminal justice system, and a reduction in the use‐

of illicit drugs by adolescents.40 Although it is not possible to conclusively attribute these trends

in Portugal to the shift to decriminalization and diversion, these findings present a strong

challenge to the notion that decriminalizing drugs – whether cannabis or others – must result in

increased misuse, dependence, and harm.

These advantages of decriminalization are significant. But this model fails to address several of

the harms associated with prohibition of cannabis use:

Under decriminalization, cannabis remains unregulated, meaning that users know little

or nothing about its potency or quality.

As long as cannabis use is illegal, it is difficult for health care or education professionals

to effectively address and help prevent problematic use. The law enforcement focus of

prohibition drives cannabis users away from prevention, risk reduction and treatment

services.

Decriminalization may encourage commercialization of cannabis production and

distribution – without giving government additional regulatory tools. Those activities

remain under the control of criminal elements, and for the most part users must still

obtain cannabis in the illicit market where they may be exposed to other drugs and to

criminal activity.

38 Room et al., 2010

39 Room et al., 2010

40 Hughes and Stevens, 2010

Decriminalization: a half measure

Models of cannabis decriminalization vary greatly, but generally they involve removing

possession of small amounts of cannabis from the sphere of criminal law. Prohibition remains

the rule, but sanctions for possession and use of cannabis instead become civil violations

punishable by a small fine.

Evidence suggests that a decriminalization approach can reduce some of the adverse social

impacts of criminalization. 38 Removing criminal penalties for cannabis possession should result

in a reduction in both the number of people caught up in the criminal justice system and the

cost of enforcement, thus reducing the burden to individuals and to the legal system. There is

little evidence that decriminalization causes an increase in the consumption of cannabis or the

prevalence of cannabis dependence.39

In Portugal, possession and use of all drugs have been decriminalized since 2001. The

Portuguese model focuses on diversion: drug use is formally prohibited but authorities refer

users to a three person panel whose primary aim is to direct people with substance use‐

problems to treatment. These panels are also empowered to apply civil penalties such as fines.

Since the implementation of this system, Portugal has seen declines in substance misuse and in

drug related harm, a reduced burden on the criminal justice system, and a reduction in the use‐

of illicit drugs by adolescents.40 Although it is not possible to conclusively attribute these trends

in Portugal to the shift to decriminalization and diversion, these findings present a strong

challenge to the notion that decriminalizing drugs – whether cannabis or others – must result in

increased misuse, dependence, and harm.

These advantages of decriminalization are significant. But this model fails to address several of

the harms associated with prohibition of cannabis use:

Under decriminalization, cannabis remains unregulated, meaning that users know little

or nothing about its potency or quality.

As long as cannabis use is illegal, it is difficult for health care or education professionals

to effectively address and help prevent problematic use. The law enforcement focus of

prohibition drives cannabis users away from prevention, risk reduction and treatment

services.

Decriminalization may encourage commercialization of cannabis production and

distribution – without giving government additional regulatory tools. Those activities

remain under the control of criminal elements, and for the most part users must still

obtain cannabis in the illicit market where they may be exposed to other drugs and to

criminal activity.

38 Room et al., 2010

39 Room et al., 2010

40 Hughes and Stevens, 2010

10

The experiences of jurisdictions that have decriminalized cannabis possession also suggest that

there can be unintended consequences. In many such places the advantages of

decriminalization have been undermined by “police practices that increase the number of users

who are penalized.”41 This phenomenon is referred to as “net widening”: “more people are

getting caught up in the enforcement net, even if they suffer less serious consequences on

average.”42 In addition, fines are a regressive penalty in the sense that they place a

disproportionate burden on low income‐ individuals. There is a risk of “secondary

criminalization” if people who are unable to pay a fine are then charged criminally. 43 Thus the

main theoretical benefit of decriminalization – a reduction in adverse social impacts – is unlikely

to be equally spread through society.

Following the publication of the results of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health in

2008, the World Health Organization has placed a high emphasis on health equity and has

made a commitment to implementing a Social Determinants of Health approach to reducing

health inequities.44 This involves the routine examination and evaluation of whether health

policy measures are not only effective in reducing a jurisdiction’s health burden, but also in

reducing health inequities.45 In this context, any policy change for cannabis should be examined

on its potential to reduce or increase health inequity. The current system of cannabis control in

Canada causes high levels of inequity, with racialized minorities having a higher chance of being

arrested and prosecuted for cannabis use offences. 46 Decriminalization, being prone to police

discretion and to racial profiling, is unlikely to remove or improve this inequity.

The unintended consequences of decriminalization are particularly important in view of a

model proposed by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) in August 2013. Police

would be given the option to issue a ticket under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act for

possession of small amounts of cannabis, but would also retain the ability to lay criminal

charges under the Act. According to the CACP, this proposal would “expand the range of

enforcement options available to more effectively and efficiently address the illicit possession

of cannabis while maintaining the ability to lay formal court process charges.” 47 In view of what

we know about the disproportionate targeting of marginalized and vulnerable populations,

giving police discretion to apply more or less severe enforcement options for the same offense

is unlikely to positively impact health equity.

41 Room et al., 2010: 127

42 Room et al., 2010: 147

43 Room et al., 2010

44 Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; see also the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health.

45 Blas and Kurup, 2010

46 Wortley and Owusu Bempah, 2012; Khenti, 2014‐

47 Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, 2013

The experiences of jurisdictions that have decriminalized cannabis possession also suggest that

there can be unintended consequences. In many such places the advantages of

decriminalization have been undermined by “police practices that increase the number of users

who are penalized.”41 This phenomenon is referred to as “net widening”: “more people are

getting caught up in the enforcement net, even if they suffer less serious consequences on

average.”42 In addition, fines are a regressive penalty in the sense that they place a

disproportionate burden on low income‐ individuals. There is a risk of “secondary

criminalization” if people who are unable to pay a fine are then charged criminally. 43 Thus the

main theoretical benefit of decriminalization – a reduction in adverse social impacts – is unlikely

to be equally spread through society.

Following the publication of the results of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health in

2008, the World Health Organization has placed a high emphasis on health equity and has

made a commitment to implementing a Social Determinants of Health approach to reducing

health inequities.44 This involves the routine examination and evaluation of whether health

policy measures are not only effective in reducing a jurisdiction’s health burden, but also in

reducing health inequities.45 In this context, any policy change for cannabis should be examined

on its potential to reduce or increase health inequity. The current system of cannabis control in

Canada causes high levels of inequity, with racialized minorities having a higher chance of being

arrested and prosecuted for cannabis use offences. 46 Decriminalization, being prone to police

discretion and to racial profiling, is unlikely to remove or improve this inequity.

The unintended consequences of decriminalization are particularly important in view of a

model proposed by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) in August 2013. Police

would be given the option to issue a ticket under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act for

possession of small amounts of cannabis, but would also retain the ability to lay criminal

charges under the Act. According to the CACP, this proposal would “expand the range of

enforcement options available to more effectively and efficiently address the illicit possession

of cannabis while maintaining the ability to lay formal court process charges.” 47 In view of what

we know about the disproportionate targeting of marginalized and vulnerable populations,

giving police discretion to apply more or less severe enforcement options for the same offense

is unlikely to positively impact health equity.

41 Room et al., 2010: 127

42 Room et al., 2010: 147

43 Room et al., 2010

44 Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; see also the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health.

45 Blas and Kurup, 2010

46 Wortley and Owusu Bempah, 2012; Khenti, 2014‐

47 Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, 2013

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 22

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.