Analyzing the Canadian Housing Crisis: An Argumentative Essay

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/14

|19

|12711

|14

Essay

AI Summary

This essay delves into the pressing issue of the affordable housing crisis in Canada, arguing that the Federal Government must take control of the property market to improve affordability for renters. The author contends that this can be achieved by building more affordable housing units and implementing rent control measures. The essay further explores the opposition's viewpoint, acknowledging the private owners' desire for rental profits and the challenges this poses to government intervention. It then analyzes the potential impacts of the Federal Government's involvement in building affordable housing and introducing rent control on rent prices. The essay employs evidence-based arguments, incorporates concession and refutation, and utilizes diverse in-text citation methods to support its claims. Ultimately, the essay aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the crisis and propose actionable solutions to alleviate the financial burden on renters.

Environment and Planning A 2015, volume 47, pages 1624 – 1642

doi:10.1068/a130226p

The political economy of mortgage securitization and

the neoliberalization of housing policy in Canada

Alan Walks

University of Toronto Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6,

Canada; e-mail: alan.walks@utoronto.ca

Brian Clifford

Simon Fraser University, 2100-515 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 5K3,

Canada; e-mail: bcliffor@sfu.ca

Received 25 September 2013; in revised form 9 November 2014; published online 1 April 2015

Abstract: The Canadian case represents a distinct variety of financialization unde

capitalism, one conditioned by the structure of its mortgage markets and the domina

role played by the state in the process of mortgage securitization. Securitizat

been a key component of the neoliberalization of housing policy, with new state role

in the insuring, directing and funding of residential mortgage-backed securities

undergirding and justifying the federal shift from the provision of social rental housi

toward supporting a rental market increasingly characterized by private sector indivi

unit landlord-investors. It was primarily the state’s control over, and utilization of, th

securitization process that maintained the solvency of the financial system in the fac

the global financial crisis. However the resulting rapid uptake of liabilities on behalf

both the state and households brought forth new contradictions, necessitating new p

experimentation and reregulation, to which securitization was once again direct

which now articulate the political economy of housing in the country.

Keywords: securitization, neoliberalism, mortgage markets, financialization, governance

public policy, housing, financial crisis, Canada

Among the debates concerning the political economy of ‘financialization’, defined as the

increasing tendency for profit to accrue through financial channels as well as the increasing

importance of finance across the economy, (Epstein, 2005; Krippner 2005), the role played

by the securitization of loans is attracting new attention. Whether pursued by the private

sector or the state,(1) securitization is a method for widening private sector participation in the

funding of loans, facilitating increased access to credit, and for distributing lending risk among

different investors. Under securitization, various financial credit products are packaged into

commodities which can then be traded, including mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and

sometimes tranched into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)—the financial instruments

whose unstable and unknown values set off the global financial crisis (GFC) (Engelen et al,

2011). By stimulating the creation of secondary bond markets open to international investors,

securitization is (officially) meant to enhance financial stability by spreading risk, while

simultaneously facilitating ‘market completion’ by allowing the level of risk associated with

different borrowers to be ‘properly’ priced. Yet in reality, securitization encourages market

competition for yield while allowing debt issuers to offload credit risk, inducing ever-more

(1) While securitization in the United States was initiated and implemented by the Government

Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), over time the dominant trend in the US and elsewhere has been for

private sector financial institutions to package loans into securities for sale to investors. Regardless,

securitization could not occur without the policy and regulatory context being set by national states.

doi:10.1068/a130226p

The political economy of mortgage securitization and

the neoliberalization of housing policy in Canada

Alan Walks

University of Toronto Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6,

Canada; e-mail: alan.walks@utoronto.ca

Brian Clifford

Simon Fraser University, 2100-515 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 5K3,

Canada; e-mail: bcliffor@sfu.ca

Received 25 September 2013; in revised form 9 November 2014; published online 1 April 2015

Abstract: The Canadian case represents a distinct variety of financialization unde

capitalism, one conditioned by the structure of its mortgage markets and the domina

role played by the state in the process of mortgage securitization. Securitizat

been a key component of the neoliberalization of housing policy, with new state role

in the insuring, directing and funding of residential mortgage-backed securities

undergirding and justifying the federal shift from the provision of social rental housi

toward supporting a rental market increasingly characterized by private sector indivi

unit landlord-investors. It was primarily the state’s control over, and utilization of, th

securitization process that maintained the solvency of the financial system in the fac

the global financial crisis. However the resulting rapid uptake of liabilities on behalf

both the state and households brought forth new contradictions, necessitating new p

experimentation and reregulation, to which securitization was once again direct

which now articulate the political economy of housing in the country.

Keywords: securitization, neoliberalism, mortgage markets, financialization, governance

public policy, housing, financial crisis, Canada

Among the debates concerning the political economy of ‘financialization’, defined as the

increasing tendency for profit to accrue through financial channels as well as the increasing

importance of finance across the economy, (Epstein, 2005; Krippner 2005), the role played

by the securitization of loans is attracting new attention. Whether pursued by the private

sector or the state,(1) securitization is a method for widening private sector participation in the

funding of loans, facilitating increased access to credit, and for distributing lending risk among

different investors. Under securitization, various financial credit products are packaged into

commodities which can then be traded, including mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and

sometimes tranched into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)—the financial instruments

whose unstable and unknown values set off the global financial crisis (GFC) (Engelen et al,

2011). By stimulating the creation of secondary bond markets open to international investors,

securitization is (officially) meant to enhance financial stability by spreading risk, while

simultaneously facilitating ‘market completion’ by allowing the level of risk associated with

different borrowers to be ‘properly’ priced. Yet in reality, securitization encourages market

competition for yield while allowing debt issuers to offload credit risk, inducing ever-more

(1) While securitization in the United States was initiated and implemented by the Government

Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), over time the dominant trend in the US and elsewhere has been for

private sector financial institutions to package loans into securities for sale to investors. Regardless,

securitization could not occur without the policy and regulatory context being set by national states.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The political economy of mortgage securitization 1625

risky behavior among an assortment of players, including banks, mortgage brokers, and

households (Ashton, 2009; Engelen et al, 2011).

Understanding the historical and political evolution of securitization provides insights

into related processes of neoliberalization and financialization (and their cotravellers, rising

indebtedness and financial instability). Neoliberalization is often posed as the solution to

the problems which it itself throws up, with neoliberal public policies improvised in relation

to existing legislative and regulatory legacies, characterizing neoliberalism’s tendency to

‘fail forward’ (Peck, 2010; 2012). Debates remain, however, about how to understand the

path-dependent and scaler aspects of this process (Brenner et al, 2010; Peck and Tickell

2002), and how they pertain to financialization and/or financial crises. In contrast to scholars

who focus on either the greed of elites (supporting an explanation of ‘fiasco’) or misplaced

public policies (in which the financial crisis might be termed an ‘accident’), Engelen et al

(2011) invoke the concept of bricolage, supporting an explanation of ‘debacle’. Bricolage

presents an alternative rationality to that attributed to the scientist, planner, or engineer,

whereby structures are created in order to provide the means for attaining particular ends or

events. Instead, bricolage involves the creation of systems and structures in path-dependent

fashion “by means of events” and “the creative and resourceful use of materials at hand—

regardless of their original purpose” (page 51). Such structures develop and evolve as a result

of the incremental opportunist activities of interested agents in response to stimuli within

the confines of contexts not of their own making. The development of various financial

innovations, as well as their markets and the roles played by actors within them, were thus

dependent on how the interests, promises, and expectations of those agents interacted with

the evolving financial architecture.

The concept of bricolage works well as a heuristic for the confluence of factors that

stimulated financial innovations and the resulting debacle/crisis in the United States and

the United Kingdom (Engelen et al, 2011). However, given tendencies toward uneven

development and the variegated character of capitalism (Peck and Theodore, 2007), processes

of neoliberalization and financialization can be expected to take many different forms, and

display distinct path dependencies (Brenner et al, 2010). How are we to understand these

processes in the Canadian case? In Canada, which has seen its housing market become

one of the least affordable on the planet since the GFC (The Economist 2013), the state

has promoted neoliberalization through financialization, and has been a central player in

the institutionalization of mortgage securitization. The Canadian experience challenges

common views on neoliberalism that link it necessarily with deregulation or the withering

of the state. It was only through the fashioning of more complex regulatory structures and

deeper involvement of the state that securitization came to dominate mortgage finance in

Canada, and it is these state-driven changes that have been at the forefront of the incremental

neoliberalization of Canadian housing policy. Neoliberalization and financialization have

become mutually reinforcing, locking out alternative policy frameworks and creating vested

interests opposed to reform of the system. With the federal state and key state institutions as

core ‘bricoleurs’ in this system, we understand neoliberalization and financialization in the

Canadian context as reflecting a particular, state-centered, form of bricolage.

This paper has three main objectives. First, it seeks to uncover the political and legislative

events through which Canada’s peculiar state-driven program of securitization was fashioned.

Second, the paper interrogates the relationship between the rise of securitization and the

restructuring of housing policy, asking how the latter relates to processes of neoliberalization

and what role the former plays in this. Third, this paper draws on this empirical work to

examine the spatiopolitical structures and pressures acting on the system and guiding path-

dependent policy experimentation within the context of state, regional, and household strains

risky behavior among an assortment of players, including banks, mortgage brokers, and

households (Ashton, 2009; Engelen et al, 2011).

Understanding the historical and political evolution of securitization provides insights

into related processes of neoliberalization and financialization (and their cotravellers, rising

indebtedness and financial instability). Neoliberalization is often posed as the solution to

the problems which it itself throws up, with neoliberal public policies improvised in relation

to existing legislative and regulatory legacies, characterizing neoliberalism’s tendency to

‘fail forward’ (Peck, 2010; 2012). Debates remain, however, about how to understand the

path-dependent and scaler aspects of this process (Brenner et al, 2010; Peck and Tickell

2002), and how they pertain to financialization and/or financial crises. In contrast to scholars

who focus on either the greed of elites (supporting an explanation of ‘fiasco’) or misplaced

public policies (in which the financial crisis might be termed an ‘accident’), Engelen et al

(2011) invoke the concept of bricolage, supporting an explanation of ‘debacle’. Bricolage

presents an alternative rationality to that attributed to the scientist, planner, or engineer,

whereby structures are created in order to provide the means for attaining particular ends or

events. Instead, bricolage involves the creation of systems and structures in path-dependent

fashion “by means of events” and “the creative and resourceful use of materials at hand—

regardless of their original purpose” (page 51). Such structures develop and evolve as a result

of the incremental opportunist activities of interested agents in response to stimuli within

the confines of contexts not of their own making. The development of various financial

innovations, as well as their markets and the roles played by actors within them, were thus

dependent on how the interests, promises, and expectations of those agents interacted with

the evolving financial architecture.

The concept of bricolage works well as a heuristic for the confluence of factors that

stimulated financial innovations and the resulting debacle/crisis in the United States and

the United Kingdom (Engelen et al, 2011). However, given tendencies toward uneven

development and the variegated character of capitalism (Peck and Theodore, 2007), processes

of neoliberalization and financialization can be expected to take many different forms, and

display distinct path dependencies (Brenner et al, 2010). How are we to understand these

processes in the Canadian case? In Canada, which has seen its housing market become

one of the least affordable on the planet since the GFC (The Economist 2013), the state

has promoted neoliberalization through financialization, and has been a central player in

the institutionalization of mortgage securitization. The Canadian experience challenges

common views on neoliberalism that link it necessarily with deregulation or the withering

of the state. It was only through the fashioning of more complex regulatory structures and

deeper involvement of the state that securitization came to dominate mortgage finance in

Canada, and it is these state-driven changes that have been at the forefront of the incremental

neoliberalization of Canadian housing policy. Neoliberalization and financialization have

become mutually reinforcing, locking out alternative policy frameworks and creating vested

interests opposed to reform of the system. With the federal state and key state institutions as

core ‘bricoleurs’ in this system, we understand neoliberalization and financialization in the

Canadian context as reflecting a particular, state-centered, form of bricolage.

This paper has three main objectives. First, it seeks to uncover the political and legislative

events through which Canada’s peculiar state-driven program of securitization was fashioned.

Second, the paper interrogates the relationship between the rise of securitization and the

restructuring of housing policy, asking how the latter relates to processes of neoliberalization

and what role the former plays in this. Third, this paper draws on this empirical work to

examine the spatiopolitical structures and pressures acting on the system and guiding path-

dependent policy experimentation within the context of state, regional, and household strains

1626 A Walks, B Clifford

related to the financial crisis. In these objectives, this article empirically extends Walks’s

(2014) research on the state’s role in Canada’s housing system, by; (a) excavating the

legislative roots of neoliberal reforms to Canadian federal housing policy in the 1980s and

1990s; (b) interrogating the links between the new mortgage finance system centered on

securitization and the residualization of social-rental housing; and (c) analyzing the post-

GFC restructuring of mortgage insurance functions.

This paper begins with a discussion of the relationships between securitization,

financialization, and neoliberalism. It then moves on to examine the structure and history

of mortgage securitization in Canada, with a focus on key decisions, events, and institutions

as the main ‘bricoleurs’ of the system. The political history of securitization is excavated

from analysis of published reports, parliamentary standing committee minutes, debates, and

Hansard—the Canadian parliamentary record (all the data analyzed for this paper derive

from publicly available sources). The political economy of securitization in the post-GFC

era is then interrogated, with the implications of the shift of public policy toward further

marketization explored for the evolving sociospatial terrain of financialization. The paper

concludes by discussing the importance of this political history for an understanding of related

processes of financialization, state-centered bricolage, and neoliberalization in nations such

as Canada.

Securitization, financialization, and neoliberalism

The restructuring of mortgage markets and the practice of securitization have been

among the most salient processes associated with contemporary financialization. Particularly

in the period after the Asian currency crisis of the late 1990s, securitization (regardless of

the level of state involvement) enabled capital investment to switch between the primary

(production-based) and secondary (property development) circuits (see Gotham, 2009). Ease

of credit availability and declining interest rates spurred the take-up of mortgage credit, and

fuelled global housing bubbles as rising demand pushed up housing prices. This has resulted

in record levels of household debt in many nations, primarily but not only in the form of

mortgages. It is in this context that mortgage securitization represents the ‘financialization

of home’ (Aalbers, 2008), as the new liquid securities linked to residential real estate became

the ‘widgets’ of the financialized postindustrial economy (Newman, 2009). Securitization

is associated with more risky lending and higher loan-to-value ratios (Sufi, 2012). The

‘originate-and-distribute’ model of securitization reduces banks’ interest in fair and prudent

lending and, as the supply of low-risk borrowers dwindles, lenders are incentivized to search

out those with ever-lower credit scores, incomes, and employment prospects, leading over

time to declining lending standards (Sassen, 2009; Sufi, 2012). The growth of predatory

loans and rising indebtedness (and subsequent foreclosures) are linked to new class, race,

and generational inequalities (see Engel and McCoy, 2011; Immergluck, 2009; Sufi, 2012;

Walks, 2013; Wyly et al, 2006; 2012).

Key tenets of neoliberalism include prioritizing of private property, commodification,

and trust in price signals to provide valid information regarding underlying values, needs, and

preferences, combined with antagonism toward the welfare state and redistributive policies

(Hackworth, 2007; Harvey 2005; Peck, 2010). Neoliberalism has in practice been associated

with the deregulation of finance, and the rise in importance of derivatives and bond markets,

both as technologies for disciplining private and public actors (for instance, punishing the

bonds of states or firms that do not budget wisely), and for hedging investments and relaying

information about shifts in valuation through specialized price signals such as interest-rate

spreads, and credit default swap (CDS) spreads (Hackworth, 2007; Major, 2012). Peck and

Tickell (2002) distinguish between ‘roll-back’ neoliberalism, involving reductions in welfare

state benefits, deregulation, and the privatization or elimination of state-provided collective

related to the financial crisis. In these objectives, this article empirically extends Walks’s

(2014) research on the state’s role in Canada’s housing system, by; (a) excavating the

legislative roots of neoliberal reforms to Canadian federal housing policy in the 1980s and

1990s; (b) interrogating the links between the new mortgage finance system centered on

securitization and the residualization of social-rental housing; and (c) analyzing the post-

GFC restructuring of mortgage insurance functions.

This paper begins with a discussion of the relationships between securitization,

financialization, and neoliberalism. It then moves on to examine the structure and history

of mortgage securitization in Canada, with a focus on key decisions, events, and institutions

as the main ‘bricoleurs’ of the system. The political history of securitization is excavated

from analysis of published reports, parliamentary standing committee minutes, debates, and

Hansard—the Canadian parliamentary record (all the data analyzed for this paper derive

from publicly available sources). The political economy of securitization in the post-GFC

era is then interrogated, with the implications of the shift of public policy toward further

marketization explored for the evolving sociospatial terrain of financialization. The paper

concludes by discussing the importance of this political history for an understanding of related

processes of financialization, state-centered bricolage, and neoliberalization in nations such

as Canada.

Securitization, financialization, and neoliberalism

The restructuring of mortgage markets and the practice of securitization have been

among the most salient processes associated with contemporary financialization. Particularly

in the period after the Asian currency crisis of the late 1990s, securitization (regardless of

the level of state involvement) enabled capital investment to switch between the primary

(production-based) and secondary (property development) circuits (see Gotham, 2009). Ease

of credit availability and declining interest rates spurred the take-up of mortgage credit, and

fuelled global housing bubbles as rising demand pushed up housing prices. This has resulted

in record levels of household debt in many nations, primarily but not only in the form of

mortgages. It is in this context that mortgage securitization represents the ‘financialization

of home’ (Aalbers, 2008), as the new liquid securities linked to residential real estate became

the ‘widgets’ of the financialized postindustrial economy (Newman, 2009). Securitization

is associated with more risky lending and higher loan-to-value ratios (Sufi, 2012). The

‘originate-and-distribute’ model of securitization reduces banks’ interest in fair and prudent

lending and, as the supply of low-risk borrowers dwindles, lenders are incentivized to search

out those with ever-lower credit scores, incomes, and employment prospects, leading over

time to declining lending standards (Sassen, 2009; Sufi, 2012). The growth of predatory

loans and rising indebtedness (and subsequent foreclosures) are linked to new class, race,

and generational inequalities (see Engel and McCoy, 2011; Immergluck, 2009; Sufi, 2012;

Walks, 2013; Wyly et al, 2006; 2012).

Key tenets of neoliberalism include prioritizing of private property, commodification,

and trust in price signals to provide valid information regarding underlying values, needs, and

preferences, combined with antagonism toward the welfare state and redistributive policies

(Hackworth, 2007; Harvey 2005; Peck, 2010). Neoliberalism has in practice been associated

with the deregulation of finance, and the rise in importance of derivatives and bond markets,

both as technologies for disciplining private and public actors (for instance, punishing the

bonds of states or firms that do not budget wisely), and for hedging investments and relaying

information about shifts in valuation through specialized price signals such as interest-rate

spreads, and credit default swap (CDS) spreads (Hackworth, 2007; Major, 2012). Peck and

Tickell (2002) distinguish between ‘roll-back’ neoliberalism, involving reductions in welfare

state benefits, deregulation, and the privatization or elimination of state-provided collective

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The political economy of mortgage securitization 1627

consumption, and ‘roll-out’ neoliberalism, involving the reregulation of both private and

public functions via market-based technologies, pricing, management, and accounting

principles.

Securitization fits well with the logic of neoliberalism. It facilitates the extension and

broadening of private ownership through commodification of income streams separated from

underlying assets, as well as stimulating new secondary markets for trading such commodities.

Furthermore, it promises market-based pricing solutions to problems of credit risk caused

by imperfect markets and asymmetric information (Ashton, 2009; Wyly et al, 2012).

Securitization capitalizes on advanced mathematical and computing technologies to monitor,

score, and underwrite credit products, and to model delinquency and default, facilitating

the development of models to price credit risk more accurately as well as providing greater

investor choice of financial products by bundling loans with different risk portfolios into

different securities. The extension of credit to underserved borrowers, and new securities to

underserved investors, is discursively constructed as ‘market completion’ (see Ashton, 2009).

One irony (for neoliberalism) is that lack of trust in the accuracy of these pricing models and

the refusal of securities owners to own-up about their assets helped fuel the credit crunch

and GFC. Furthermore, securitization in particular leads to new ‘information asymmetries’

in which financial institutions have an incentive to hide information both from regulators and

from borrowers, a factor in predatory subprime lending at the heart of the crisis in the US

(Ashton, 2009; Engel and McCoy, 2011).

Structure of the Canadian mortgage market and the role of securitization

The Canadian mortgage finance system differs from its peers elsewhere in the developed

world. Perhaps most importantly, mortgage insurance and the securitization process have

been dominated by a state-owned Crown corporation, the Canada Mortgage and Housing

Corporation (CMHC). Canada is among few developed nations that did not formally

witness any bank failures, and which escaped the GFC relatively unharmed (Carter, 2012;

Ratnovski and Huang, 2009); yet it also witnessed rapidly rising housing values and levels of

indebtedness (Walks, 2013; 2014). The key to these contradictions is found in the structure

of Canada’s mortgage finance system, and the ability of the state to intervene decisively.

Unlike the situation in other Anglo nations, in Canada securitization has been dependent on the

federal state, not only for structuring and regulating mortgage finance, but also for insuring,

guaranteeing, and purchasing most of the mortgages that have been bundled into MBS.

CMHC was created in 1946 as a vehicle for the construction of affordable rental and

owner-occupied housing and for insuring mortgages in order to encourage lending by large

banks, more similar to the US Federal Housing Administration (FHA) than to the GSEs

that insure many mortgages in the US. There are six large banks in Canada, and banks have

issued roughly three quarters of mortgages originated, with the remaining quarter issued by a

series of nonbank institutions (CMHC, 2012, page A22). Since the early 1980s, when banks

were allowed to swallow trust companies and mortgage broker-dealers, the large banks have

simultaneously housed both deposit-taking and investment banking functions (representing

roughly 33% and 10% of bank earnings, respectively) (Blakely, 2009).

In Canada mortgages issued with loan-to-value (LTV) ratios above 80% must be insured.

It is the borrower who pays the insurance, but it is the lenders (not the borrowers) who are

protected from loss in the event of default.(2) CMHC provides the majority of this insurance,

but there are two main private insurers that also insure mortgages issued by traditional

lenders—the General Electric Capital Mortgage Insurance Corporation (Genworth),

(2) Borrowers can purchase separate private mortgage insurance to protect them from death, illness,

or personal injury, but not from job loss. There are no public programs that protect borrowers from

inability to pay due to lack of employment.

consumption, and ‘roll-out’ neoliberalism, involving the reregulation of both private and

public functions via market-based technologies, pricing, management, and accounting

principles.

Securitization fits well with the logic of neoliberalism. It facilitates the extension and

broadening of private ownership through commodification of income streams separated from

underlying assets, as well as stimulating new secondary markets for trading such commodities.

Furthermore, it promises market-based pricing solutions to problems of credit risk caused

by imperfect markets and asymmetric information (Ashton, 2009; Wyly et al, 2012).

Securitization capitalizes on advanced mathematical and computing technologies to monitor,

score, and underwrite credit products, and to model delinquency and default, facilitating

the development of models to price credit risk more accurately as well as providing greater

investor choice of financial products by bundling loans with different risk portfolios into

different securities. The extension of credit to underserved borrowers, and new securities to

underserved investors, is discursively constructed as ‘market completion’ (see Ashton, 2009).

One irony (for neoliberalism) is that lack of trust in the accuracy of these pricing models and

the refusal of securities owners to own-up about their assets helped fuel the credit crunch

and GFC. Furthermore, securitization in particular leads to new ‘information asymmetries’

in which financial institutions have an incentive to hide information both from regulators and

from borrowers, a factor in predatory subprime lending at the heart of the crisis in the US

(Ashton, 2009; Engel and McCoy, 2011).

Structure of the Canadian mortgage market and the role of securitization

The Canadian mortgage finance system differs from its peers elsewhere in the developed

world. Perhaps most importantly, mortgage insurance and the securitization process have

been dominated by a state-owned Crown corporation, the Canada Mortgage and Housing

Corporation (CMHC). Canada is among few developed nations that did not formally

witness any bank failures, and which escaped the GFC relatively unharmed (Carter, 2012;

Ratnovski and Huang, 2009); yet it also witnessed rapidly rising housing values and levels of

indebtedness (Walks, 2013; 2014). The key to these contradictions is found in the structure

of Canada’s mortgage finance system, and the ability of the state to intervene decisively.

Unlike the situation in other Anglo nations, in Canada securitization has been dependent on the

federal state, not only for structuring and regulating mortgage finance, but also for insuring,

guaranteeing, and purchasing most of the mortgages that have been bundled into MBS.

CMHC was created in 1946 as a vehicle for the construction of affordable rental and

owner-occupied housing and for insuring mortgages in order to encourage lending by large

banks, more similar to the US Federal Housing Administration (FHA) than to the GSEs

that insure many mortgages in the US. There are six large banks in Canada, and banks have

issued roughly three quarters of mortgages originated, with the remaining quarter issued by a

series of nonbank institutions (CMHC, 2012, page A22). Since the early 1980s, when banks

were allowed to swallow trust companies and mortgage broker-dealers, the large banks have

simultaneously housed both deposit-taking and investment banking functions (representing

roughly 33% and 10% of bank earnings, respectively) (Blakely, 2009).

In Canada mortgages issued with loan-to-value (LTV) ratios above 80% must be insured.

It is the borrower who pays the insurance, but it is the lenders (not the borrowers) who are

protected from loss in the event of default.(2) CMHC provides the majority of this insurance,

but there are two main private insurers that also insure mortgages issued by traditional

lenders—the General Electric Capital Mortgage Insurance Corporation (Genworth),

(2) Borrowers can purchase separate private mortgage insurance to protect them from death, illness,

or personal injury, but not from job loss. There are no public programs that protect borrowers from

inability to pay due to lack of employment.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1628 A Walks, B Clifford

and Canada Guaranty (arising out of AIG United Guaranty Insurance—AIGUG—which

entered Canada shortly before the financial crisis but then had to exit once it began). Because

CMHC is a Crown corporation, 100% of the value of the mortgages insured by CMHC is

guaranteed by the federal government. However, in order to stimulate ‘competition’ in the

mortgage-insurance business, the federal government also provides the private insurers a

guarantee of 90% of the value of the outstanding conforming mortgages they insure in the

event of default (with the first 10% of losses coming from a fund which the private insurers

must contribute to as a condition of their license). Thus, the Canadian public takes on all the

risk of the mortgages insured by CMHC, and 90% of the risk of the conforming mortgages

insured by the private lenders, leading Mohindra (2010) to characterize the Canadian

mortgage finance system as the ‘high taxpayer vulnerability model’.

Under the National Housing Act (NHA) only mortgages conforming to specific criteria

established by the federal government regarding LTVs, amortization terms, downpayments,

and gross-debt service (GDS) ratios, can be insured by CMHC, or packaged into MBS insured

by CMHC (the latter are termed ‘NHA–MBS’). For this reason, most mortgages issued by

traditional lenders are NHA-conforming mortgages, leaving a small subprime market for

the origination of nonconforming mortgages to nonbank/shadow lenders. Unlike the US and

many other nations, there is no mortgage-interest tax deduction on a primary residence in

Canada; but there are also no taxes on realized capital gains on the sale of one’s primary

residence.

Securitization evolved differently in Canada than in most other developed nations. While

there are a number of different models, the more common practice that arose in other nations

is for financial institutions themselves to create special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to purchase

and pool mortgages into MBS, and to service or tranche the MBS. In Canada since June

2001, through a special purpose trust of the CMHC called the Canada Housing Trust (CHT),

the state has performed these functions, which largely did not exist beforehand. CHT sells

nonamortizing bonds called Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMBs) to large-scale investors, and

uses the funds thus raised to directly purchase conforming mortgages in NHA–MBS from

banks, moving them off banks’ balance sheets and onto on the books of CHT/CMHC. Thus,

it is a public body that absorbs credit risk and reduces the amount of capital the banks are

required to hold in reserve, allowing them to ramp up their lending. As the CMBs are 100%

guaranteed (principal and interest) by the federal government, there is no risk to investors.

Banks also have the option of bundling mortgages into NHA–MBS and either keeping

them on their books, or selling them directly to large-scale private investors. Regardless,

they remain risk-free to lenders because the underlying mortgages are fully insured. Because

of the strong role of the state in guaranteeing the value of NHA–MBS, Canadian financial

institutions did not get into the habit of structuring CDOs. Furthermore, the success and

effectiveness (and triple-A ratings) of the public-label system led to low demand for private-

label securities. The use by Canadian financial institutions of asset-backed commercial paper

(ABCP) to fund private-label MBS and other debt hit C$122 billion in 2007, but the practice

slowed dramatically with the GFC (Perkins, 2013). By early 2013 the entire Canadian ABCP

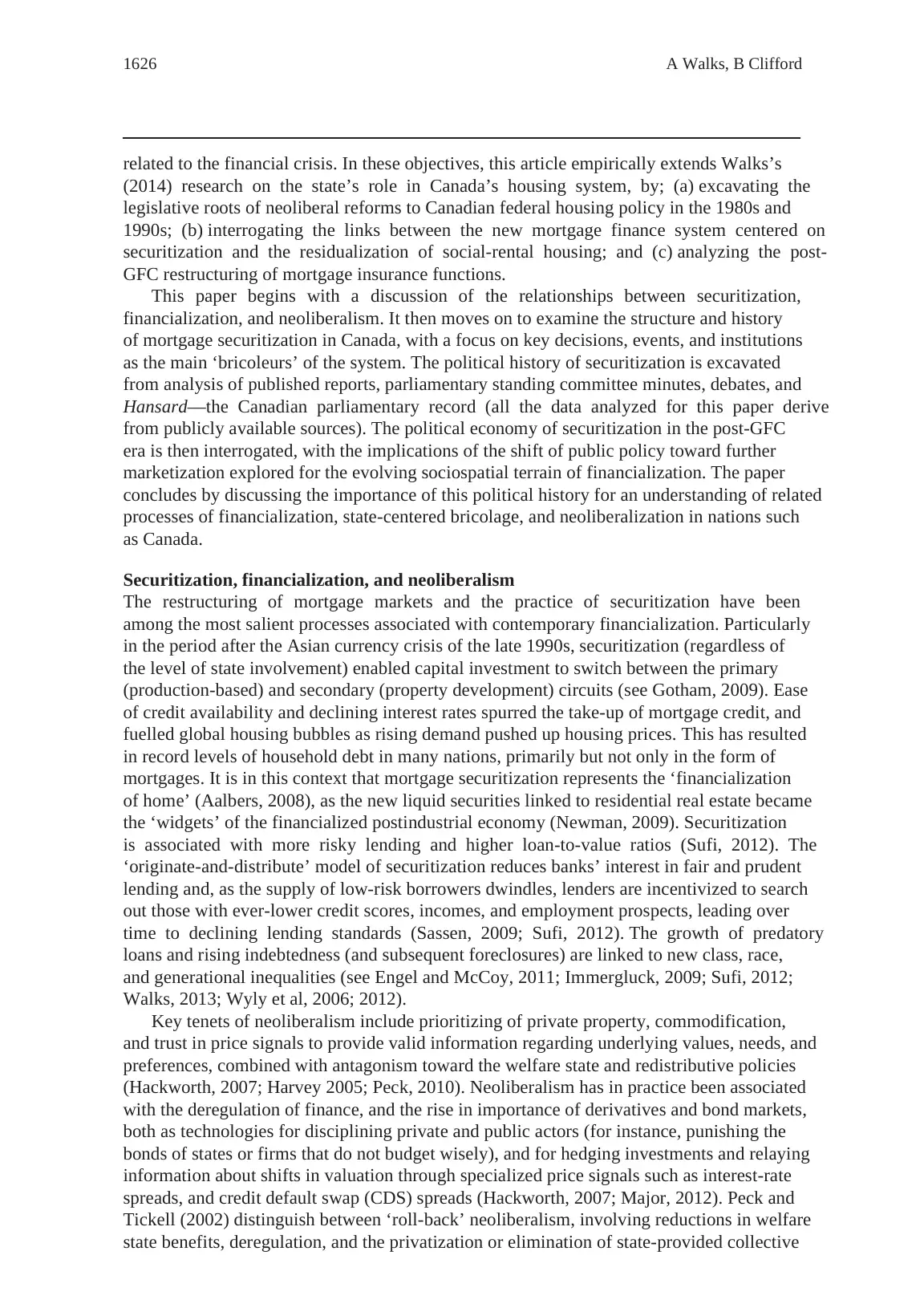

market was worth only C$26 billion (Perkins, 2013). Of the C$384.5 billion in outstanding

mortgage credit securitized in 2010, $16.2 billion, or just over 4.2%, derive from private-label

(non-NHA–MBS) securitizations (figure 1). Meanwhile, covered bonds—private securities

that banks sell to fund mortgages, but with more direct creditor access to the underlying

assets in the event of default (see CMHC, 2013)—were introduced in 2007 and have grown

rapidly since (discussed in the last section).

Just like Canadian Treasury Bonds, the CMBs come with a direct and unconditional

guarantee. If the NHA–MBS on the books of the CHT were to lose value or suffer defaults,

and Canada Guaranty (arising out of AIG United Guaranty Insurance—AIGUG—which

entered Canada shortly before the financial crisis but then had to exit once it began). Because

CMHC is a Crown corporation, 100% of the value of the mortgages insured by CMHC is

guaranteed by the federal government. However, in order to stimulate ‘competition’ in the

mortgage-insurance business, the federal government also provides the private insurers a

guarantee of 90% of the value of the outstanding conforming mortgages they insure in the

event of default (with the first 10% of losses coming from a fund which the private insurers

must contribute to as a condition of their license). Thus, the Canadian public takes on all the

risk of the mortgages insured by CMHC, and 90% of the risk of the conforming mortgages

insured by the private lenders, leading Mohindra (2010) to characterize the Canadian

mortgage finance system as the ‘high taxpayer vulnerability model’.

Under the National Housing Act (NHA) only mortgages conforming to specific criteria

established by the federal government regarding LTVs, amortization terms, downpayments,

and gross-debt service (GDS) ratios, can be insured by CMHC, or packaged into MBS insured

by CMHC (the latter are termed ‘NHA–MBS’). For this reason, most mortgages issued by

traditional lenders are NHA-conforming mortgages, leaving a small subprime market for

the origination of nonconforming mortgages to nonbank/shadow lenders. Unlike the US and

many other nations, there is no mortgage-interest tax deduction on a primary residence in

Canada; but there are also no taxes on realized capital gains on the sale of one’s primary

residence.

Securitization evolved differently in Canada than in most other developed nations. While

there are a number of different models, the more common practice that arose in other nations

is for financial institutions themselves to create special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to purchase

and pool mortgages into MBS, and to service or tranche the MBS. In Canada since June

2001, through a special purpose trust of the CMHC called the Canada Housing Trust (CHT),

the state has performed these functions, which largely did not exist beforehand. CHT sells

nonamortizing bonds called Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMBs) to large-scale investors, and

uses the funds thus raised to directly purchase conforming mortgages in NHA–MBS from

banks, moving them off banks’ balance sheets and onto on the books of CHT/CMHC. Thus,

it is a public body that absorbs credit risk and reduces the amount of capital the banks are

required to hold in reserve, allowing them to ramp up their lending. As the CMBs are 100%

guaranteed (principal and interest) by the federal government, there is no risk to investors.

Banks also have the option of bundling mortgages into NHA–MBS and either keeping

them on their books, or selling them directly to large-scale private investors. Regardless,

they remain risk-free to lenders because the underlying mortgages are fully insured. Because

of the strong role of the state in guaranteeing the value of NHA–MBS, Canadian financial

institutions did not get into the habit of structuring CDOs. Furthermore, the success and

effectiveness (and triple-A ratings) of the public-label system led to low demand for private-

label securities. The use by Canadian financial institutions of asset-backed commercial paper

(ABCP) to fund private-label MBS and other debt hit C$122 billion in 2007, but the practice

slowed dramatically with the GFC (Perkins, 2013). By early 2013 the entire Canadian ABCP

market was worth only C$26 billion (Perkins, 2013). Of the C$384.5 billion in outstanding

mortgage credit securitized in 2010, $16.2 billion, or just over 4.2%, derive from private-label

(non-NHA–MBS) securitizations (figure 1). Meanwhile, covered bonds—private securities

that banks sell to fund mortgages, but with more direct creditor access to the underlying

assets in the event of default (see CMHC, 2013)—were introduced in 2007 and have grown

rapidly since (discussed in the last section).

Just like Canadian Treasury Bonds, the CMBs come with a direct and unconditional

guarantee. If the NHA–MBS on the books of the CHT were to lose value or suffer defaults,

The political economy of mortgage securitization 1629

the difference has to be made up by the Canadian government, which makes the Canadian

state highly sensitive to the value of these assets. This is key to understanding the political

economy of securitization in Canada. In effect, the Canadian public, through federal

government institutions developed to securitize mortgages, has borrowed at fixed nominal

interest rates to collectively gamble on real estate. If real estate values continue to rise and

mortgagees continue to make their payments, the CMHC and the federal government reap

a profit, as do the speculators and households who might not have accessed mortgage credit

as easily in the absence of the program. If, on the other hand, the real-estate market were to

suffer defaults, this would effect a socialization of losses as the federal government would

have to make up the gap between the actual flows of mortgage payments and the full value of

the principal and interest of the bonds paid to private investors. The CMBs are mostly sold to

Canadian institutions (72% in 2011), or those in the US (14.5%), with insurance companies

and pension funds the most common form of investor (41.5%) (CMHC, 2012, page A27).

Thus, the pensions and insurance policies of many Canadians also largely depend on real-

estate values being maintained.

Securitization, CMHC, and the neoliberalization of housing policy 1985–2001

The history and evolution of the securitization process in Canada are implicated in the

incremental neoliberalization of housing policy, programs, and political rhetoric/discourse

at multiple scales (table 1). As in Bush’s ‘ownership society’ in the US, and ‘asset-based

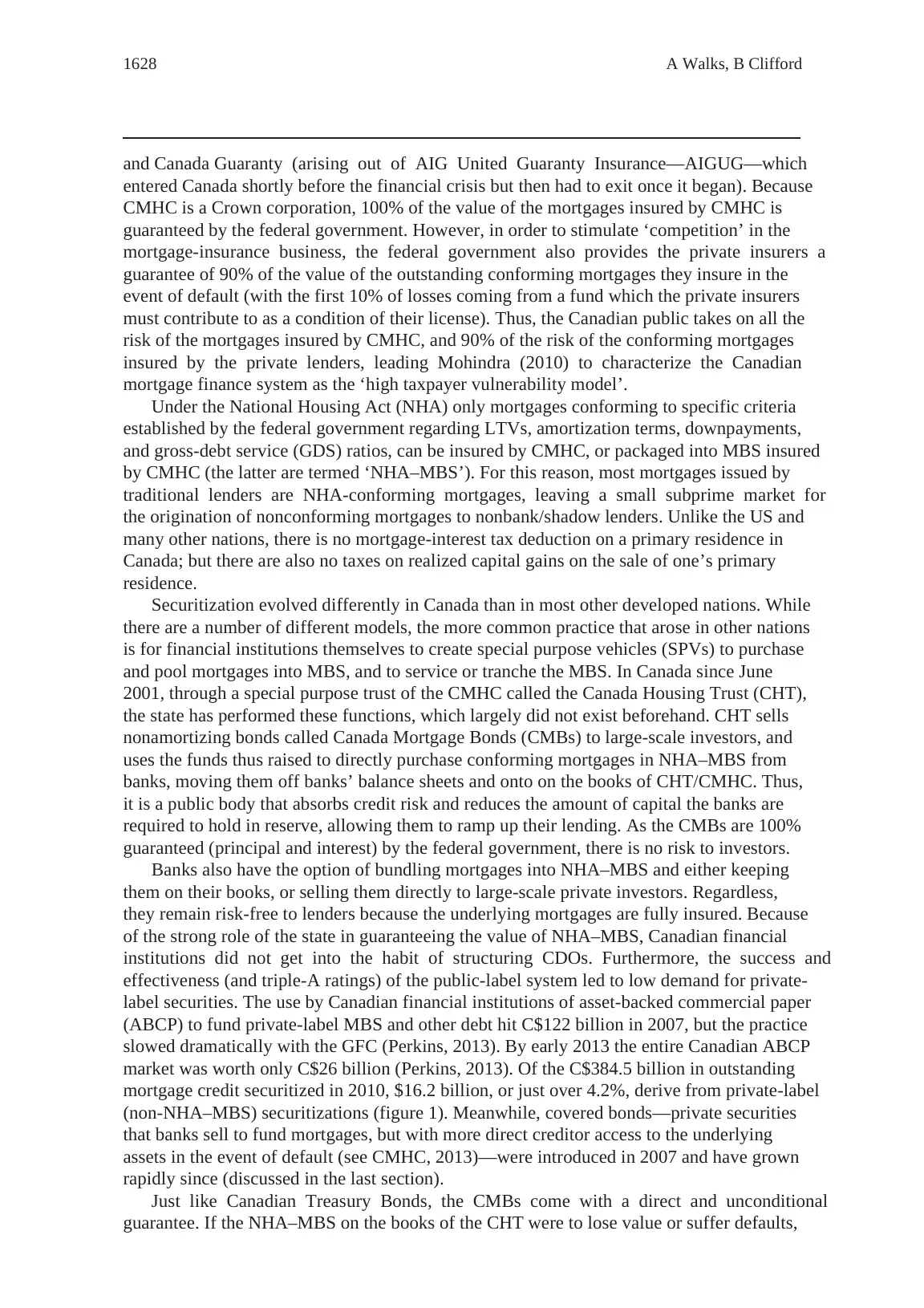

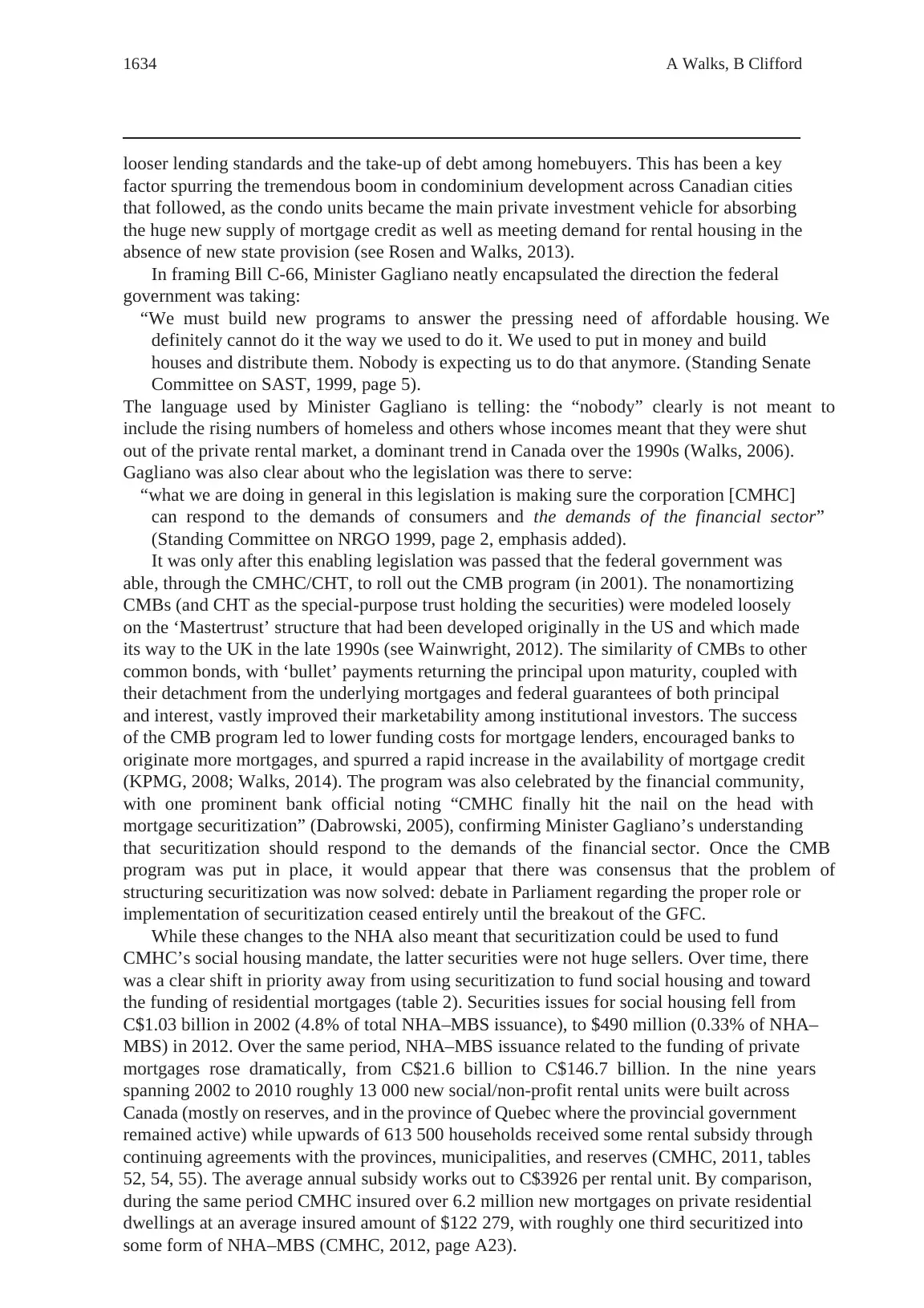

Figure 1. Total outstanding credit (C$ billions) by type of securitization, Canada 1987–2012 (source:

calculated from CMHC, 2012, pages A24–A27). ‘Regular NHA–MBS’ includes the NHA-MBS

purchased as part of the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program (IMPP) implemented as part of the

federal response to the GFC in 2008–09, and the latter is the main reason for the drastic increase in

NHA–MBS between 2007 and 2010. There is no difference in the qualifying criteria for residential

mortgages packaged into regular NHA–MBS, whether purchased through the IMPP or not, nor between

regular NHA–MBS and NHA–MBS purchased through the CMB program. All of these mortgages

must meet the minimum criteria for qualifying loans set by CMHC, including those for maximum

amortization terms, minimum downpayments (although these downpayments can often be ‘gifted’ by

the lenders and/or capitalized into the mortgages). Private-label MBS, on the other hand, in most cases

involve mortgages that would not qualify for inclusion in NHA–MBS. Covered bonds are issued by

the lenders, but the criteria for their issuance and registration is set by the CMHC.

Total outstanding credit (C$ billion)

200

160

120

80

40

0

Regular NHA–MBS

Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMB)

Private-label securitization

Covered bonds

1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

the difference has to be made up by the Canadian government, which makes the Canadian

state highly sensitive to the value of these assets. This is key to understanding the political

economy of securitization in Canada. In effect, the Canadian public, through federal

government institutions developed to securitize mortgages, has borrowed at fixed nominal

interest rates to collectively gamble on real estate. If real estate values continue to rise and

mortgagees continue to make their payments, the CMHC and the federal government reap

a profit, as do the speculators and households who might not have accessed mortgage credit

as easily in the absence of the program. If, on the other hand, the real-estate market were to

suffer defaults, this would effect a socialization of losses as the federal government would

have to make up the gap between the actual flows of mortgage payments and the full value of

the principal and interest of the bonds paid to private investors. The CMBs are mostly sold to

Canadian institutions (72% in 2011), or those in the US (14.5%), with insurance companies

and pension funds the most common form of investor (41.5%) (CMHC, 2012, page A27).

Thus, the pensions and insurance policies of many Canadians also largely depend on real-

estate values being maintained.

Securitization, CMHC, and the neoliberalization of housing policy 1985–2001

The history and evolution of the securitization process in Canada are implicated in the

incremental neoliberalization of housing policy, programs, and political rhetoric/discourse

at multiple scales (table 1). As in Bush’s ‘ownership society’ in the US, and ‘asset-based

Figure 1. Total outstanding credit (C$ billions) by type of securitization, Canada 1987–2012 (source:

calculated from CMHC, 2012, pages A24–A27). ‘Regular NHA–MBS’ includes the NHA-MBS

purchased as part of the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program (IMPP) implemented as part of the

federal response to the GFC in 2008–09, and the latter is the main reason for the drastic increase in

NHA–MBS between 2007 and 2010. There is no difference in the qualifying criteria for residential

mortgages packaged into regular NHA–MBS, whether purchased through the IMPP or not, nor between

regular NHA–MBS and NHA–MBS purchased through the CMB program. All of these mortgages

must meet the minimum criteria for qualifying loans set by CMHC, including those for maximum

amortization terms, minimum downpayments (although these downpayments can often be ‘gifted’ by

the lenders and/or capitalized into the mortgages). Private-label MBS, on the other hand, in most cases

involve mortgages that would not qualify for inclusion in NHA–MBS. Covered bonds are issued by

the lenders, but the criteria for their issuance and registration is set by the CMHC.

Total outstanding credit (C$ billion)

200

160

120

80

40

0

Regular NHA–MBS

Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMB)

Private-label securitization

Covered bonds

1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

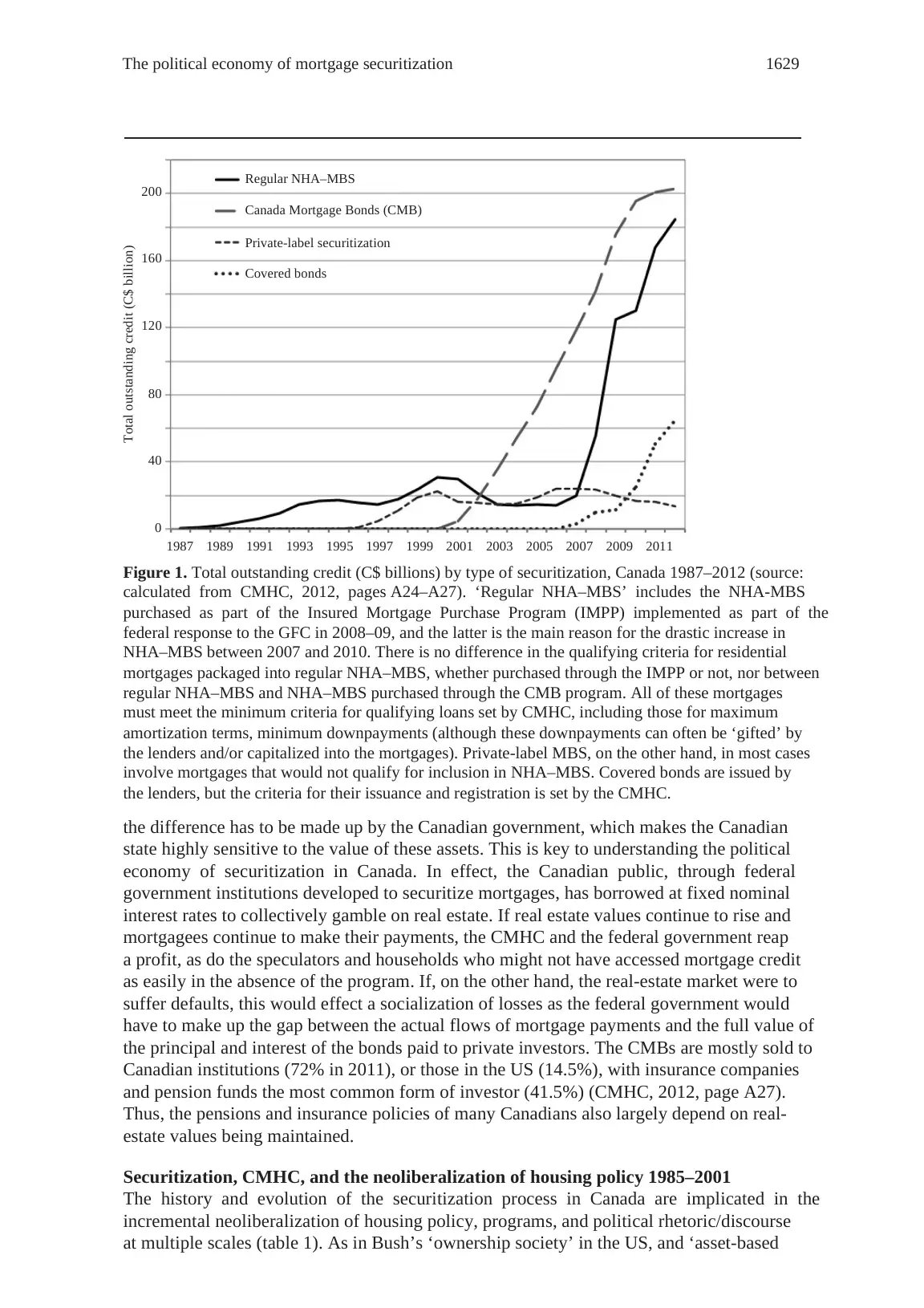

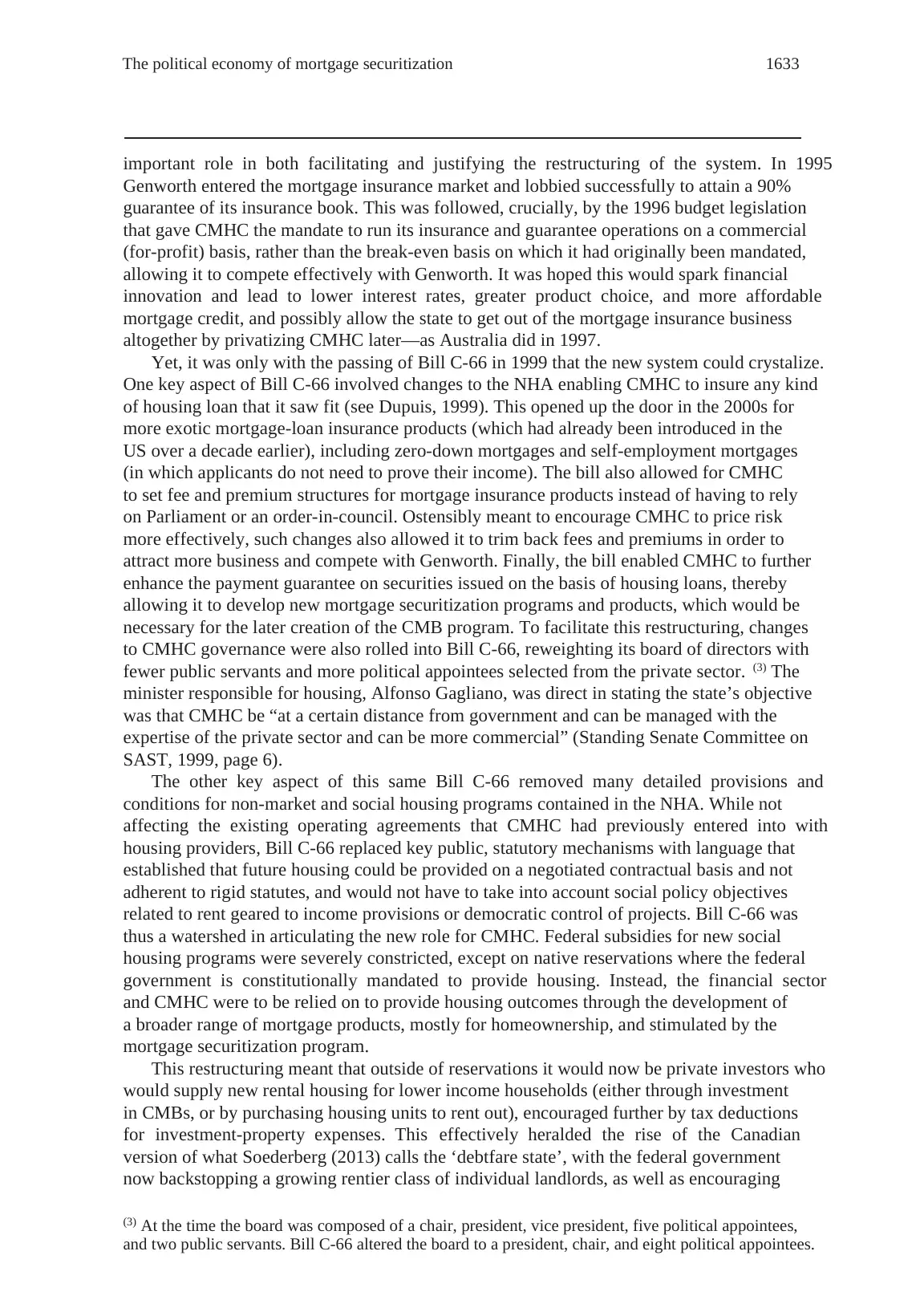

Table 1. Periodization of Canadian housing policy and governance, 1970–2012.

1970–84 1984–92 1992–2001 2001–08 2008–12 and after

Structural • Prosperity then

stagflation

• Early 1980s recession

and recovery

• Growing public debt

• Early globalization

• Rise of service-based ‘new’

economy

• Early 1990s recession

• Aggressive deficit reduction

• North American Free

Trade Agreement, new

international financial

regimes

• Dotcom (and US housing)

bubble

• Financial deregulation/

growth of financial markets

• Rising deindustrialization,

also household debt

• Global Financial Crisis

• Rapid deindustrialization

• Housing and finance as the new

leading sectors

• Canadian housing bubble

• Rapidly rising household

and government debt

Political/

rhetorical/

ideological

Keynesian/embedded

liberalism

• Housing framed as

a social right, state

has role in providing

subsidized housing

Neoliberal onset and

roll-back

• Discrediting of Keynesianism/

embedded liberalism

• Emphasis on deficit reduction,

‘efficiency’

• Need to harness private sector

Neoliberal roll-out

• Construction and

consolidation of market-

based approach

• Regulated financial

innovation and market

competition can meet social

objectives

• Emphasis on partnerships—

‘third way’ social policy

Deepening neoliberalization

through financialization, and

deregulation

• Euphoria over the power

of financial markets and

competition to deliver

housing outcomes

• Rhetoric: deficit problem

‘solved’

Crisis management and

government stimulus

• Rhetoric: banking system saved

by prudent regulation and prudent

private sector practices

• Government deficit once again a

problem

• Emphasis on austerity, further

welfare-state roll-back

Housing

policy

Emphasis on social

housing

• Subsidy-based

public, nonprofit, and

cooperative programs

• Subsidy-based

homeownership plans

(AHOP)

• Subsidy-based

programs to increase

private rental supply

(ARP)

Restructuring and cancellation of

social housing programs

• Questioning of Canada

Mortgage and Housing

Corporation’s proper role

• Mortgage securitization

launched to promote access

to mortgage credit (National

Housing Act—mortgage-backed

securities) (Bill C-37)

• Extension of mortgage insurance

on more products (Bill C-111)

Capping of social housing

subsidies

• Devolution of social

housing responsibility to the

provinces

• CMHC reformed to operate

like a competitive, private

insurance company

• Use of securitization,

mortgage insurance reforms

to achieve housing policy

objectives

• Commercialization of the

CMHC (Bill C-66)

Reliance on private sector to

supply rental housing

• Securitization and loose

credit becomes primary

affordable housing policy

• Canada Mortgage Bonds

(CMB) program

• New private mortgage

insurance competitors, yet

with state guarantees

• Extension of mortgage

insurance to ‘exotic’

products aimed at low-

income households

State bails out the mortgage-

finance system

• Insured Mortgage Purchase

Program (IMPP)

• Post-GFC, official silence on use

of securitization for recession

fighting

• Shift from CMHC to private-

sector mortgage insurers (while

maintaining state guarantees), and

to new private sector financial

vehicles (covered bonds, etc) as a

way of dealing with rapidly rising

state liabilities

1970–84 1984–92 1992–2001 2001–08 2008–12 and after

Structural • Prosperity then

stagflation

• Early 1980s recession

and recovery

• Growing public debt

• Early globalization

• Rise of service-based ‘new’

economy

• Early 1990s recession

• Aggressive deficit reduction

• North American Free

Trade Agreement, new

international financial

regimes

• Dotcom (and US housing)

bubble

• Financial deregulation/

growth of financial markets

• Rising deindustrialization,

also household debt

• Global Financial Crisis

• Rapid deindustrialization

• Housing and finance as the new

leading sectors

• Canadian housing bubble

• Rapidly rising household

and government debt

Political/

rhetorical/

ideological

Keynesian/embedded

liberalism

• Housing framed as

a social right, state

has role in providing

subsidized housing

Neoliberal onset and

roll-back

• Discrediting of Keynesianism/

embedded liberalism

• Emphasis on deficit reduction,

‘efficiency’

• Need to harness private sector

Neoliberal roll-out

• Construction and

consolidation of market-

based approach

• Regulated financial

innovation and market

competition can meet social

objectives

• Emphasis on partnerships—

‘third way’ social policy

Deepening neoliberalization

through financialization, and

deregulation

• Euphoria over the power

of financial markets and

competition to deliver

housing outcomes

• Rhetoric: deficit problem

‘solved’

Crisis management and

government stimulus

• Rhetoric: banking system saved

by prudent regulation and prudent

private sector practices

• Government deficit once again a

problem

• Emphasis on austerity, further

welfare-state roll-back

Housing

policy

Emphasis on social

housing

• Subsidy-based

public, nonprofit, and

cooperative programs

• Subsidy-based

homeownership plans

(AHOP)

• Subsidy-based

programs to increase

private rental supply

(ARP)

Restructuring and cancellation of

social housing programs

• Questioning of Canada

Mortgage and Housing

Corporation’s proper role

• Mortgage securitization

launched to promote access

to mortgage credit (National

Housing Act—mortgage-backed

securities) (Bill C-37)

• Extension of mortgage insurance

on more products (Bill C-111)

Capping of social housing

subsidies

• Devolution of social

housing responsibility to the

provinces

• CMHC reformed to operate

like a competitive, private

insurance company

• Use of securitization,

mortgage insurance reforms

to achieve housing policy

objectives

• Commercialization of the

CMHC (Bill C-66)

Reliance on private sector to

supply rental housing

• Securitization and loose

credit becomes primary

affordable housing policy

• Canada Mortgage Bonds

(CMB) program

• New private mortgage

insurance competitors, yet

with state guarantees

• Extension of mortgage

insurance to ‘exotic’

products aimed at low-

income households

State bails out the mortgage-

finance system

• Insured Mortgage Purchase

Program (IMPP)

• Post-GFC, official silence on use

of securitization for recession

fighting

• Shift from CMHC to private-

sector mortgage insurers (while

maintaining state guarantees), and

to new private sector financial

vehicles (covered bonds, etc) as a

way of dealing with rapidly rising

state liabilities

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The political economy of mortgage securitization 1631

welfare’ in the UK (Ronald, 2008), the Canadian state has increasingly relied on the

triumvirate of securitization, credit growth, and rising homeownership as the basis for

an asset-based approach to housing policy, and moved away from the direct funding of

purpose-built, subsidized social-rental housing. While CMHC, set up to maintain housing

affordability, insure mortgages, and build social housing, has been the key institution through

which the federal government has implemented and directed the securitization program, it is

the Canadian federal government which has been the core ‘bricoleur’ in building the unique

state-led yet neoliberal housing system.

From its early inception CMHC was tasked with achieving state social policy objectives

both in affordable social rental housing and in private mortgage insurance (Bacher, 1993).

The social role of CMHC was strengthened over the early postwar period as amendments

to the NHA increased its commitment to income redistribution through a raft of subsidy-

based programs and activities aimed at increasing the supply of social and nonprofit housing

(Government of Canada, 1979; Smith, 1981). However, these social policy objectives came

into question after the early 1980s recession and the election of a new federal government

in 1984. The embrace of neoliberalism began in earnest with the implementation of a

consultative review of the government’s role in the mortgage market in 1985 (CMHC,

1986), which de-emphasized subsidy-based housing programs and promoted the expansion

of the CMHC’s role in delivering housing policy outcomes through its mortgage insurance

activities. It was this review that recommended the creation of a system of mortgage-backed

securities (CMHC, 1986), in part as a tool for reducing the federal deficit in the face of high

nominal interest rates under the assumption that MBS insurance operations would not require

direct subsidies.

The original securitization program, begun in 1987, was mostly modeled on the public-

label securitization process then practiced by the US GSEs. Although implemented quietly

and without much public or media awareness of the program, securitization was touted as

“one of the most important initiatives in Canadian housing finance since the introduction of

public mortgage insurance” (CMHC, 1987, page 26). While other ways of structuring housing

finance could also have been proposed, securitization was already perceived as successful in

reducing US banks’ capital funding costs and freeing them to increase lending, increasing US

rates of homeownership and stabilizing their mortgage finance system, and so was looked

upon favorably (Government of Canada, 1985; O’Brien, 1988). The Canadian program also

sought to use securitization to provide a non-subsidy-based method of funding social-rental

housing, through amendments (in 1988) that allowed for exclusive social housing loan pools

for securities issues (CMHC, 1988, page 18, discussed below).

The initial securitization program experienced some success in the late 1980s and very

early 1990s, with the proportion of new mortgage originations securitized rising from zero

to over 15% in only five years. However, the early 1990s recession and rising interest rates

reduced investor demand for this form of NHA–MBS, while also squeezing public finances.

While the neoliberal ‘roll-back’ of the Canadian welfare state had begun earlier, it was only

when the recession hit that this came to be aggressively pursued through housing policy

reforms. This occurred in two ways. First, the federal government disentangled and devolved

itself from new social housing commitments, freezing subsidies in 1993, off-loading much of

its social housing portfolios onto the provinces (most of whom were also financially strapped,

and who then chose to limit or cancel new social housing commitments), discontinuing its

cooperative housing program, and restructuring federal transfer payments for social welfare

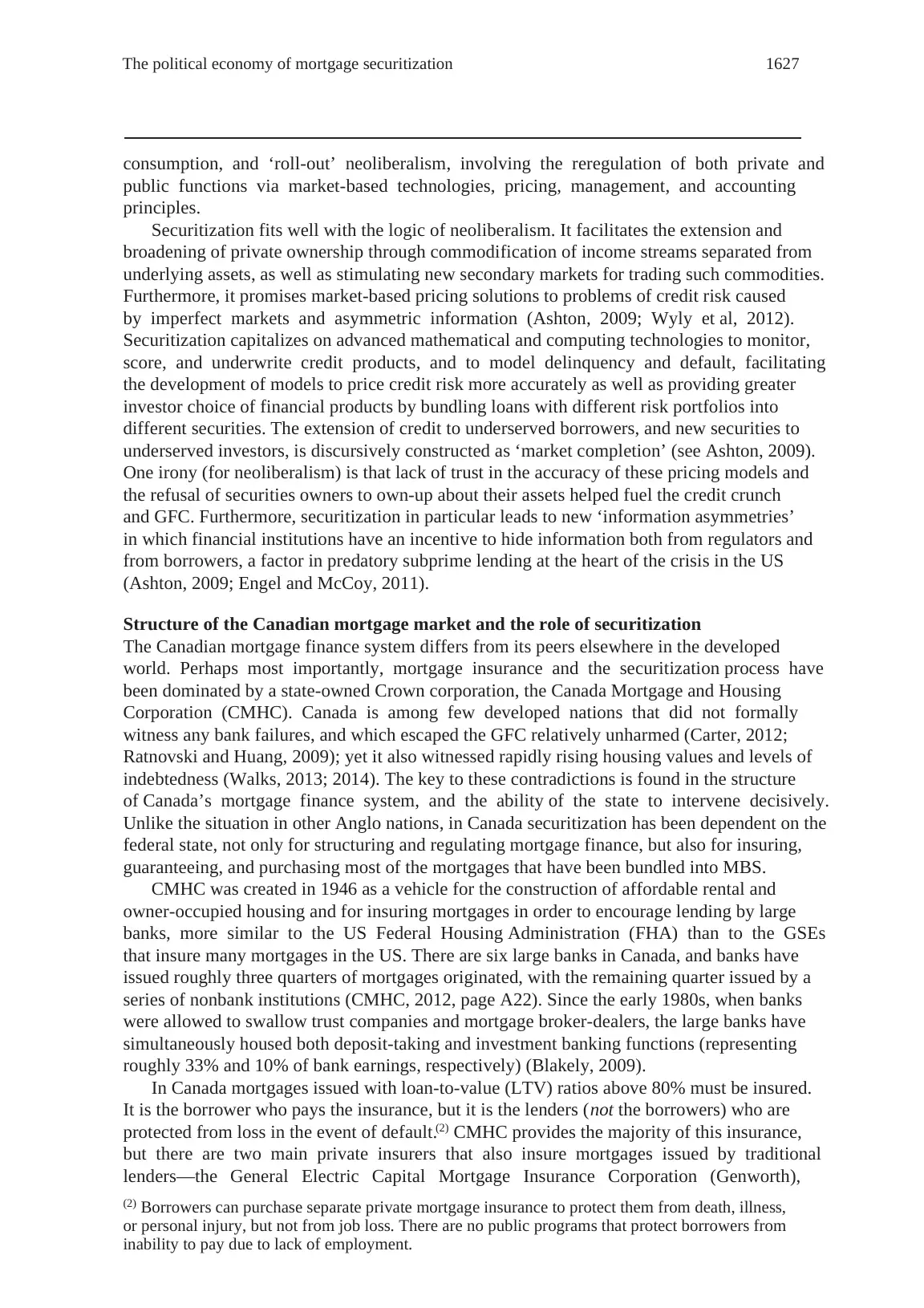

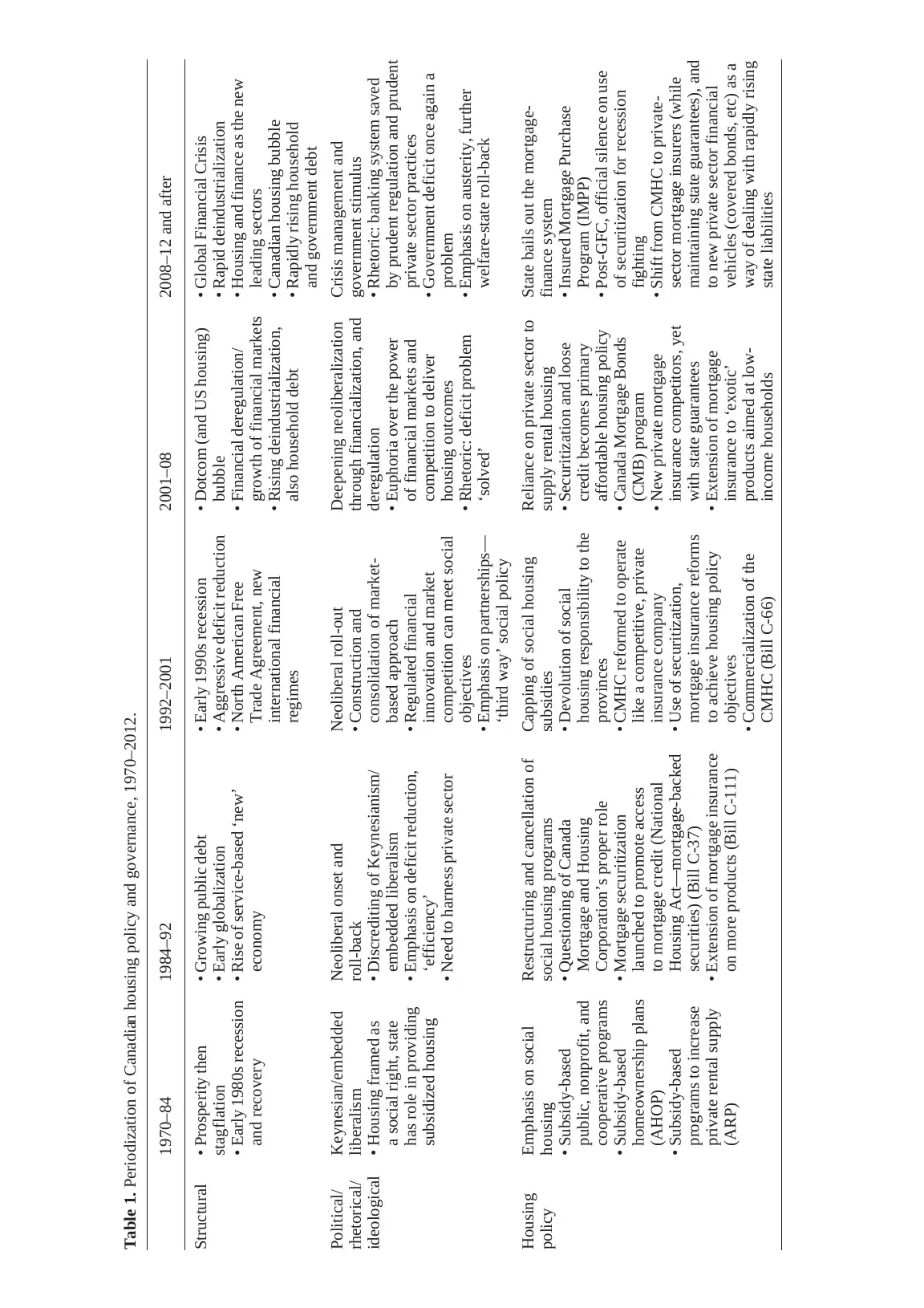

functions (see Colderly, 1999; Hackworth, 2008; McKeen and Porter, 2003). The result was

a drastic decline in the numbers of social-rental housing units built after 1993, a problem that

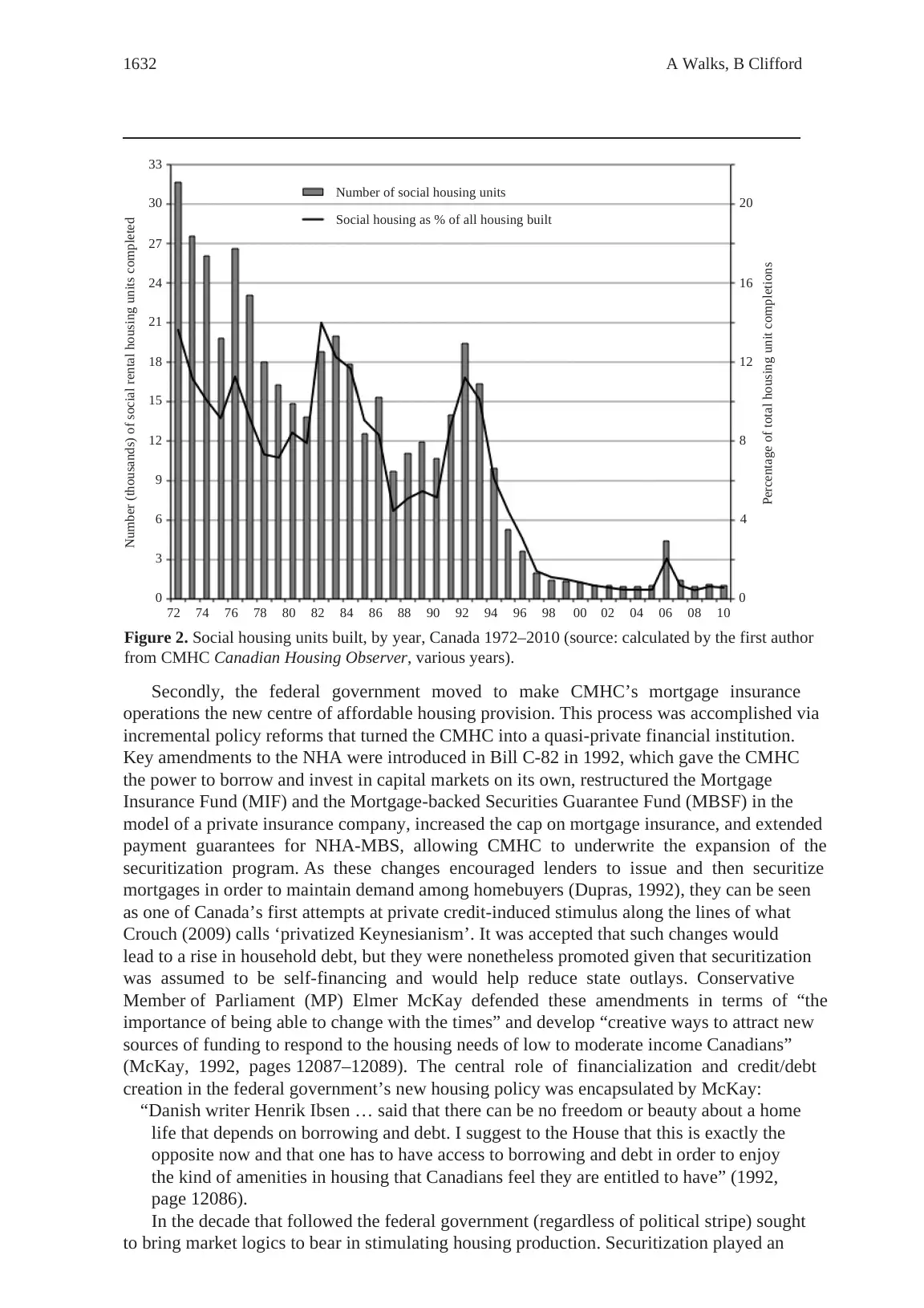

continues to this day (figure 2).

welfare’ in the UK (Ronald, 2008), the Canadian state has increasingly relied on the

triumvirate of securitization, credit growth, and rising homeownership as the basis for

an asset-based approach to housing policy, and moved away from the direct funding of

purpose-built, subsidized social-rental housing. While CMHC, set up to maintain housing

affordability, insure mortgages, and build social housing, has been the key institution through

which the federal government has implemented and directed the securitization program, it is

the Canadian federal government which has been the core ‘bricoleur’ in building the unique

state-led yet neoliberal housing system.

From its early inception CMHC was tasked with achieving state social policy objectives

both in affordable social rental housing and in private mortgage insurance (Bacher, 1993).

The social role of CMHC was strengthened over the early postwar period as amendments

to the NHA increased its commitment to income redistribution through a raft of subsidy-

based programs and activities aimed at increasing the supply of social and nonprofit housing

(Government of Canada, 1979; Smith, 1981). However, these social policy objectives came

into question after the early 1980s recession and the election of a new federal government

in 1984. The embrace of neoliberalism began in earnest with the implementation of a

consultative review of the government’s role in the mortgage market in 1985 (CMHC,

1986), which de-emphasized subsidy-based housing programs and promoted the expansion

of the CMHC’s role in delivering housing policy outcomes through its mortgage insurance

activities. It was this review that recommended the creation of a system of mortgage-backed

securities (CMHC, 1986), in part as a tool for reducing the federal deficit in the face of high

nominal interest rates under the assumption that MBS insurance operations would not require

direct subsidies.

The original securitization program, begun in 1987, was mostly modeled on the public-

label securitization process then practiced by the US GSEs. Although implemented quietly

and without much public or media awareness of the program, securitization was touted as

“one of the most important initiatives in Canadian housing finance since the introduction of

public mortgage insurance” (CMHC, 1987, page 26). While other ways of structuring housing

finance could also have been proposed, securitization was already perceived as successful in

reducing US banks’ capital funding costs and freeing them to increase lending, increasing US

rates of homeownership and stabilizing their mortgage finance system, and so was looked

upon favorably (Government of Canada, 1985; O’Brien, 1988). The Canadian program also

sought to use securitization to provide a non-subsidy-based method of funding social-rental

housing, through amendments (in 1988) that allowed for exclusive social housing loan pools

for securities issues (CMHC, 1988, page 18, discussed below).

The initial securitization program experienced some success in the late 1980s and very

early 1990s, with the proportion of new mortgage originations securitized rising from zero

to over 15% in only five years. However, the early 1990s recession and rising interest rates

reduced investor demand for this form of NHA–MBS, while also squeezing public finances.

While the neoliberal ‘roll-back’ of the Canadian welfare state had begun earlier, it was only

when the recession hit that this came to be aggressively pursued through housing policy

reforms. This occurred in two ways. First, the federal government disentangled and devolved

itself from new social housing commitments, freezing subsidies in 1993, off-loading much of

its social housing portfolios onto the provinces (most of whom were also financially strapped,

and who then chose to limit or cancel new social housing commitments), discontinuing its

cooperative housing program, and restructuring federal transfer payments for social welfare

functions (see Colderly, 1999; Hackworth, 2008; McKeen and Porter, 2003). The result was

a drastic decline in the numbers of social-rental housing units built after 1993, a problem that

continues to this day (figure 2).

1632 A Walks, B Clifford

Secondly, the federal government moved to make CMHC’s mortgage insurance

operations the new centre of affordable housing provision. This process was accomplished via

incremental policy reforms that turned the CMHC into a quasi-private financial institution.

Key amendments to the NHA were introduced in Bill C-82 in 1992, which gave the CMHC

the power to borrow and invest in capital markets on its own, restructured the Mortgage

Insurance Fund (MIF) and the Mortgage-backed Securities Guarantee Fund (MBSF) in the

model of a private insurance company, increased the cap on mortgage insurance, and extended

payment guarantees for NHA-MBS, allowing CMHC to underwrite the expansion of the

securitization program. As these changes encouraged lenders to issue and then securitize

mortgages in order to maintain demand among homebuyers (Dupras, 1992), they can be seen

as one of Canada’s first attempts at private credit-induced stimulus along the lines of what

Crouch (2009) calls ‘privatized Keynesianism’. It was accepted that such changes would

lead to a rise in household debt, but they were nonetheless promoted given that securitization

was assumed to be self-financing and would help reduce state outlays. Conservative

Member of Parliament (MP) Elmer McKay defended these amendments in terms of “the

importance of being able to change with the times” and develop “creative ways to attract new

sources of funding to respond to the housing needs of low to moderate income Canadians”

(McKay, 1992, pages 12087–12089). The central role of financialization and credit/debt

creation in the federal government’s new housing policy was encapsulated by McKay:

“Danish writer Henrik Ibsen … said that there can be no freedom or beauty about a home

life that depends on borrowing and debt. I suggest to the House that this is exactly the

opposite now and that one has to have access to borrowing and debt in order to enjoy

the kind of amenities in housing that Canadians feel they are entitled to have” (1992,

page 12086).

In the decade that followed the federal government (regardless of political stripe) sought

to bring market logics to bear in stimulating housing production. Securitization played an

Figure 2. Social housing units built, by year, Canada 1972–2010 (source: calculated by the first author

from CMHC Canadian Housing Observer, various years).

33

30

27

24

21

18

15

12

9

6

3

0

Number (thousands) of social rental housing units completed 20

16

12

8

4

0

Percentage of total housing unit completions

10080604020098969492888684828078767472 90

Number of social housing units

Social housing as % of all housing built

Secondly, the federal government moved to make CMHC’s mortgage insurance

operations the new centre of affordable housing provision. This process was accomplished via

incremental policy reforms that turned the CMHC into a quasi-private financial institution.

Key amendments to the NHA were introduced in Bill C-82 in 1992, which gave the CMHC

the power to borrow and invest in capital markets on its own, restructured the Mortgage

Insurance Fund (MIF) and the Mortgage-backed Securities Guarantee Fund (MBSF) in the

model of a private insurance company, increased the cap on mortgage insurance, and extended

payment guarantees for NHA-MBS, allowing CMHC to underwrite the expansion of the

securitization program. As these changes encouraged lenders to issue and then securitize

mortgages in order to maintain demand among homebuyers (Dupras, 1992), they can be seen

as one of Canada’s first attempts at private credit-induced stimulus along the lines of what

Crouch (2009) calls ‘privatized Keynesianism’. It was accepted that such changes would

lead to a rise in household debt, but they were nonetheless promoted given that securitization

was assumed to be self-financing and would help reduce state outlays. Conservative

Member of Parliament (MP) Elmer McKay defended these amendments in terms of “the

importance of being able to change with the times” and develop “creative ways to attract new

sources of funding to respond to the housing needs of low to moderate income Canadians”

(McKay, 1992, pages 12087–12089). The central role of financialization and credit/debt

creation in the federal government’s new housing policy was encapsulated by McKay:

“Danish writer Henrik Ibsen … said that there can be no freedom or beauty about a home

life that depends on borrowing and debt. I suggest to the House that this is exactly the

opposite now and that one has to have access to borrowing and debt in order to enjoy

the kind of amenities in housing that Canadians feel they are entitled to have” (1992,

page 12086).

In the decade that followed the federal government (regardless of political stripe) sought

to bring market logics to bear in stimulating housing production. Securitization played an

Figure 2. Social housing units built, by year, Canada 1972–2010 (source: calculated by the first author

from CMHC Canadian Housing Observer, various years).

33

30

27

24

21

18

15

12

9

6

3

0

Number (thousands) of social rental housing units completed 20

16

12

8

4

0

Percentage of total housing unit completions

10080604020098969492888684828078767472 90

Number of social housing units

Social housing as % of all housing built

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

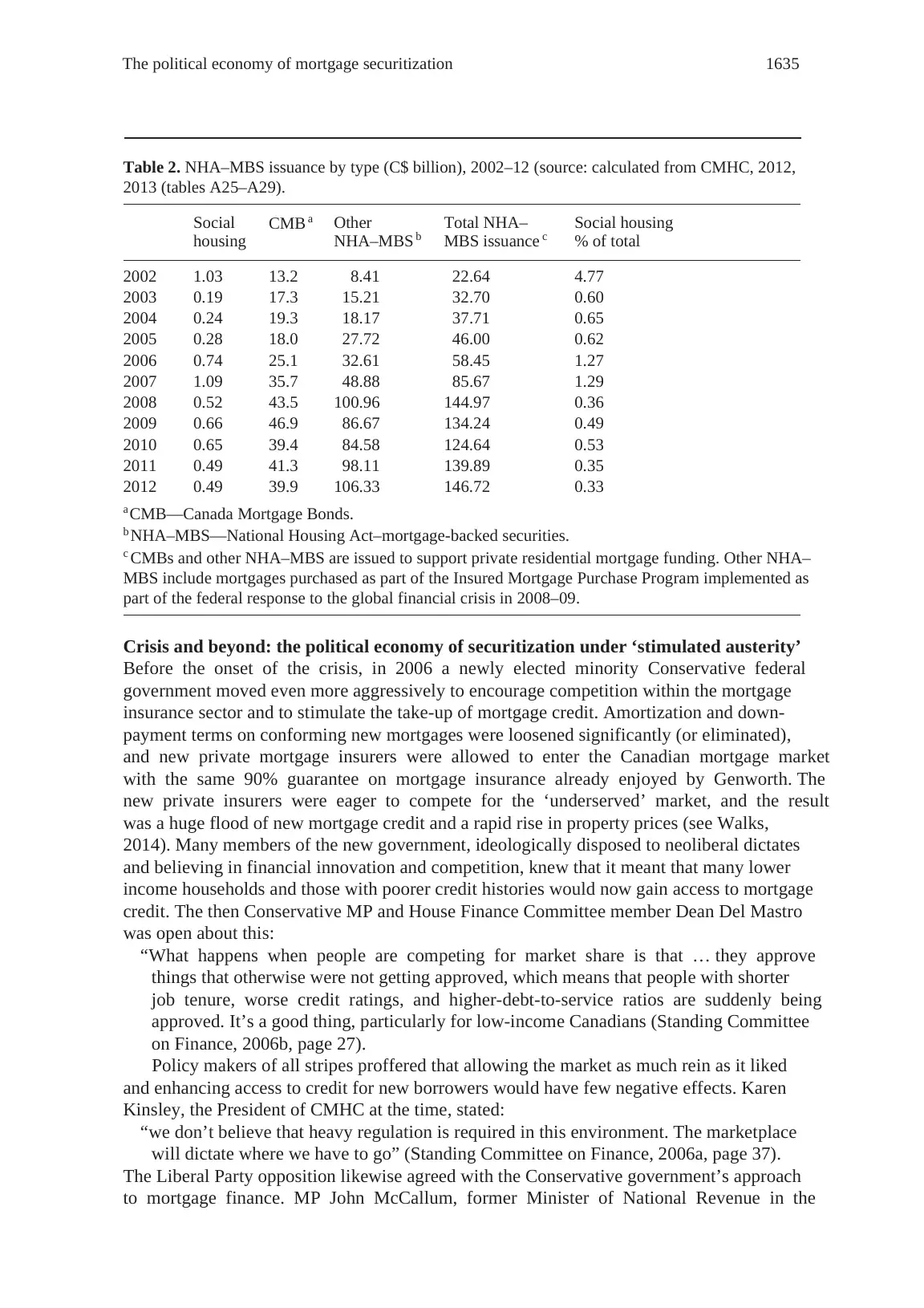

The political economy of mortgage securitization 1633

important role in both facilitating and justifying the restructuring of the system. In 1995

Genworth entered the mortgage insurance market and lobbied successfully to attain a 90%

guarantee of its insurance book. This was followed, crucially, by the 1996 budget legislation

that gave CMHC the mandate to run its insurance and guarantee operations on a commercial

(for-profit) basis, rather than the break-even basis on which it had originally been mandated,

allowing it to compete effectively with Genworth. It was hoped this would spark financial

innovation and lead to lower interest rates, greater product choice, and more affordable

mortgage credit, and possibly allow the state to get out of the mortgage insurance business

altogether by privatizing CMHC later—as Australia did in 1997.

Yet, it was only with the passing of Bill C-66 in 1999 that the new system could crystalize.

One key aspect of Bill C-66 involved changes to the NHA enabling CMHC to insure any kind

of housing loan that it saw fit (see Dupuis, 1999). This opened up the door in the 2000s for

more exotic mortgage-loan insurance products (which had already been introduced in the

US over a decade earlier), including zero-down mortgages and self-employment mortgages

(in which applicants do not need to prove their income). The bill also allowed for CMHC

to set fee and premium structures for mortgage insurance products instead of having to rely

on Parliament or an order-in-council. Ostensibly meant to encourage CMHC to price risk

more effectively, such changes also allowed it to trim back fees and premiums in order to

attract more business and compete with Genworth. Finally, the bill enabled CMHC to further

enhance the payment guarantee on securities issued on the basis of housing loans, thereby

allowing it to develop new mortgage securitization programs and products, which would be

necessary for the later creation of the CMB program. To facilitate this restructuring, changes

to CMHC governance were also rolled into Bill C-66, reweighting its board of directors with

fewer public servants and more political appointees selected from the private sector. (3) The

minister responsible for housing, Alfonso Gagliano, was direct in stating the state’s objective

was that CMHC be “at a certain distance from government and can be managed with the

expertise of the private sector and can be more commercial” (Standing Senate Committee on

SAST, 1999, page 6).

The other key aspect of this same Bill C-66 removed many detailed provisions and

conditions for non-market and social housing programs contained in the NHA. While not

affecting the existing operating agreements that CMHC had previously entered into with

housing providers, Bill C-66 replaced key public, statutory mechanisms with language that

established that future housing could be provided on a negotiated contractual basis and not

adherent to rigid statutes, and would not have to take into account social policy objectives

related to rent geared to income provisions or democratic control of projects. Bill C-66 was

thus a watershed in articulating the new role for CMHC. Federal subsidies for new social

housing programs were severely constricted, except on native reservations where the federal

government is constitutionally mandated to provide housing. Instead, the financial sector

and CMHC were to be relied on to provide housing outcomes through the development of

a broader range of mortgage products, mostly for homeownership, and stimulated by the

mortgage securitization program.

This restructuring meant that outside of reservations it would now be private investors who

would supply new rental housing for lower income households (either through investment

in CMBs, or by purchasing housing units to rent out), encouraged further by tax deductions

for investment-property expenses. This effectively heralded the rise of the Canadian