Case Study: CMAJ Analysis of Cannabis Legalization and Public Health

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/14

|6

|6409

|266

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study analyzes cannabis legalization policies through a public health lens, drawing on experiences from countries like Uruguay, the Netherlands, and the United States. It uses a framework based on tobacco and alcohol regulation to assess the potential harms and benefits of different legalization approaches. The analysis emphasizes that the primary goal of cannabis legalization should be public health promotion and protection, including delaying youth use, reducing risky use, and minimizing addiction. The study also cautions against the rise of 'Big Cannabis' and advocates for government control over production, distribution, and marketing to prevent commercialization and prioritize public health objectives. Ultimately, the case study provides a resource for policymakers and researchers to evaluate cannabis policies and their outcomes, promoting evidence-based decision-making in the context of cannabis legalization.

AnalysisCMAJ

©2015 8872147 Canada Inc. or its licensors CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1211

According to the 2011 United Nations

World Drug Report, the prevalence of

cannabis use in the Netherlands, where

cannabis has been de facto legal for the last 40

years, is lower than in many other European

countries, the United States and Canada.1 Juris-

dictions that have recently legalized cannabis

(Uruguay and four US states) or redefined can-

nabis legalization policies (Catalonia) may be

expecting a similar result. However, if their poli-

cies governing cannabis are different, they may

see different outcomes.

In this article, we analyze cannabis legaliza-

tion policies through a public health lens using a

framework2 created from extensive data on to-

bacco3 and alcohol regulation.4 The aim of this

article, and indeed the framework, is to go be-

yond reduction in use and include minimization

of harms and realization of benefits.5 Cannabis

policy will be a topic of debate in Canada in the

lead-up to the federal election in October. The

governing party favours the status quo, one of

the competing political parties has promised

decriminalization, and another party supports le-

galization.6 Surveys have shown that most Can-

adians are looking for change.7,8 We provide a

resource for Canadian policy-makers looking to

reform cannabis laws and a tool for researchers

evaluating cannabis policies and their outcomes.

A broad picture of cannabis use

and legality

A 2013 UNICEF study found that the prevalence

of cannabis use among youth in the preceding

year was highest in Canada (28%) and lower in

Spain (24%), the US (22%) and the Netherlands

(17%).9 A 2014 survey in Uruguay found that

17% of secondary school children reported using

cannabis in the preceding year.10 According to the

2011 UN World Drug Report, cannabis use in the

general population was higher in Canada, the US

and Spain than in Uruguay and the Netherlands.1

There are an estimated 180.6 million cannabis

users worldwide,11 most living in jurisdictions

where cannabis is illegal.

In the past three years, Uruguay and four US

states have gone beyond the limited legalization

policies in Spain and the Netherlands to fully legal-

ize the possession, production and sale of cannabis.

Many other jurisdictions have removed criminal

penalties for possession or have legalized cannabis

for medical use, or both. Canada legalized the use

of cannabis for medical indications in 2001 and

implemented updated regulations for medical use

and production in 2014.12 Possession of cannabis

for nonmedical use remains a criminal offence, and

about 60 000 Canadians are charged yearly.13

Legalization of cannabis for nonmedical use

remains contrary to the 1961 UN Single Conven-

tion on Narcotic Drugs. Signatory countries can

address this by renegotiating, withdrawing from

or ignoring the treaty. Uruguay has chosen the

third approach, arguing that its legalization

framework follows the more important UN val-

ues of human rights, public health and safety.14

What are the harms from cannabis

use and its prohibition?

Policies that prohibit cannabis cause harm.15 They

funnel money into the illegal market and drive

criminal activity. They harm individuals through

imprisonment, marginalization and the creation of

barriers to treatment. This burden falls dispropor-

tionately on vulnerable groups; even though white

and black Americans use cannabis at about the

Cannabis legalization: adhering to public health best p

Sheryl Spithoff MD, Brian Emerson MD MHSc, Andrea Spithoff MA

Competing interests: None

declared.

This article has been peer

reviewed.

Correspondence to:

Sheryl Spithoff,

sheryl.spithoff@wchospital.ca

CMAJ 2015. DOI:10.1503

/cmaj.150657

• Prohibition of cannabis has failed to achieve its goal of reducing use

and causes substantial public health and societal harm.

• Two of Canada’s three main political parties promise to reform

cannabis policies if voted into power.

• If Canadian policy-makers move away from prohibitionist policies and

create a legal framework for cannabis, public health promotion and

protection must be the primary goals.

• Lessons learned from permissive alcohol and tobacco regulation can

guide public health–oriented policy-making; in particular, a ban on

promotion and advertising of cannabis to prevent commercialization

will be important.

• Policy-makers should look to jurisdictions with legalized cannabis that

prioritize public health and use evidence, not ideology, to guide policies.

Key points

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/150657-ana

©2015 8872147 Canada Inc. or its licensors CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1211

According to the 2011 United Nations

World Drug Report, the prevalence of

cannabis use in the Netherlands, where

cannabis has been de facto legal for the last 40

years, is lower than in many other European

countries, the United States and Canada.1 Juris-

dictions that have recently legalized cannabis

(Uruguay and four US states) or redefined can-

nabis legalization policies (Catalonia) may be

expecting a similar result. However, if their poli-

cies governing cannabis are different, they may

see different outcomes.

In this article, we analyze cannabis legaliza-

tion policies through a public health lens using a

framework2 created from extensive data on to-

bacco3 and alcohol regulation.4 The aim of this

article, and indeed the framework, is to go be-

yond reduction in use and include minimization

of harms and realization of benefits.5 Cannabis

policy will be a topic of debate in Canada in the

lead-up to the federal election in October. The

governing party favours the status quo, one of

the competing political parties has promised

decriminalization, and another party supports le-

galization.6 Surveys have shown that most Can-

adians are looking for change.7,8 We provide a

resource for Canadian policy-makers looking to

reform cannabis laws and a tool for researchers

evaluating cannabis policies and their outcomes.

A broad picture of cannabis use

and legality

A 2013 UNICEF study found that the prevalence

of cannabis use among youth in the preceding

year was highest in Canada (28%) and lower in

Spain (24%), the US (22%) and the Netherlands

(17%).9 A 2014 survey in Uruguay found that

17% of secondary school children reported using

cannabis in the preceding year.10 According to the

2011 UN World Drug Report, cannabis use in the

general population was higher in Canada, the US

and Spain than in Uruguay and the Netherlands.1

There are an estimated 180.6 million cannabis

users worldwide,11 most living in jurisdictions

where cannabis is illegal.

In the past three years, Uruguay and four US

states have gone beyond the limited legalization

policies in Spain and the Netherlands to fully legal-

ize the possession, production and sale of cannabis.

Many other jurisdictions have removed criminal

penalties for possession or have legalized cannabis

for medical use, or both. Canada legalized the use

of cannabis for medical indications in 2001 and

implemented updated regulations for medical use

and production in 2014.12 Possession of cannabis

for nonmedical use remains a criminal offence, and

about 60 000 Canadians are charged yearly.13

Legalization of cannabis for nonmedical use

remains contrary to the 1961 UN Single Conven-

tion on Narcotic Drugs. Signatory countries can

address this by renegotiating, withdrawing from

or ignoring the treaty. Uruguay has chosen the

third approach, arguing that its legalization

framework follows the more important UN val-

ues of human rights, public health and safety.14

What are the harms from cannabis

use and its prohibition?

Policies that prohibit cannabis cause harm.15 They

funnel money into the illegal market and drive

criminal activity. They harm individuals through

imprisonment, marginalization and the creation of

barriers to treatment. This burden falls dispropor-

tionately on vulnerable groups; even though white

and black Americans use cannabis at about the

Cannabis legalization: adhering to public health best p

Sheryl Spithoff MD, Brian Emerson MD MHSc, Andrea Spithoff MA

Competing interests: None

declared.

This article has been peer

reviewed.

Correspondence to:

Sheryl Spithoff,

sheryl.spithoff@wchospital.ca

CMAJ 2015. DOI:10.1503

/cmaj.150657

• Prohibition of cannabis has failed to achieve its goal of reducing use

and causes substantial public health and societal harm.

• Two of Canada’s three main political parties promise to reform

cannabis policies if voted into power.

• If Canadian policy-makers move away from prohibitionist policies and

create a legal framework for cannabis, public health promotion and

protection must be the primary goals.

• Lessons learned from permissive alcohol and tobacco regulation can

guide public health–oriented policy-making; in particular, a ban on

promotion and advertising of cannabis to prevent commercialization

will be important.

• Policy-makers should look to jurisdictions with legalized cannabis that

prioritize public health and use evidence, not ideology, to guide policies.

Key points

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/150657-ana

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Analysis

1212 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

same rate, the latter are 3.73 times more likely to

be arrested for possession.16 Finally, society pays

with high policing, court and prison costs.15,17

Harms from regular cannabis use may be less

than those associated with other psychoactive

substances,18 but they are still substantial at a pop-

ulation level. At higher doses, cannabis is a well-

established risk for motor vehicle crashes.19,20

Combining alcohol with cannabis results in

greater impairment than either substance alone.21

A recent study estimated that 6825–20 475 inju-

ries from cannabis-attributed motor vehicle

crashes occur in Canada annually.19 Each year in

Canada, 76 000–95 000 people undergo cannabis

addiction treatment and 219–547 cannabis-related

deaths occur (from injuries in motor vehicle

crashes and lung disease).19 Youth are particularly

vulnerable to the effects of cannabis: regular users

frequently report loss of control over their canna-

bis use,22 have lower educational attainment23 and

may have, according to one cohort study, a drop

in IQ that persists into adulthood.24

Often the harms from prohibition versus harms

from potential increased use of cannabis are

falsely pitted against each other. Evidence shows,

however, that cannabis prohibition has no effect

on rates of use, at least in developed countries.25–28

Some have advocated for the removal of crimi-

nal penalties for possession instead of legalization.

With Portugal’s experience in decriminalizing can-

nabis, users benefit from reduced marginalization,

imprisonment and barriers to treatment, and soci-

ety benefits from reduced policing, court and

prison costs.17 The illegal supply chain, however,

continues to fund criminal activity. In addition, be-

cause the government does not control the produc-

tion, processing, supply or price of cannabis, it has

a limited ability to achieve public health goals.

What objectives should underpin

legalization?

If policy-makers opt to legalize cannabis, careful

planning and comprehensive governmental con-

trols would provide the greatest likelihood of

minimizing harms and maximizing benefits. A

cannabis legalization framework should explic-

itly state that public health promotion and pro-

tection are its primary goals. It should list spe-

cific objectives,5,29,30

including delayed onset of

use by youth; reduced demand; reduced risky

use (e.g., reduced impaired driving); decreased

rates of problematic use, addiction and concur-

rent risky use of other substances; reduced con-

sumption of products with contaminants and un-

certain potency; increased public safety (e.g.,

reduced drug-related crime); reduced discrimina-

tion, stigmatization and marginalization of user

and realization of therapeutic benefits.

A frequently cited concern with legalization i

that it will allow the rise of Big Cannabis,31 simi-

lar to Big Tobacco and Big Alcohol. These pow-

erful multinational corporations have revenu

and market expansion as their primary goals, w

little consideration of the impact on public hea

They increase tobacco and alcohol use by lobb

ing for favourable regulations32 and funding huge

marketing campaigns.33 It is important that the

regulations actively work against the establish-

ment of Big Cannabis.

Evaluating cannabis regulations

through a public health lens

There is scant direct evidence to guide the cre-

ation of public health–oriented cannabis policie

Fortunately, there is an extensive evidence bas

for two other substances with potential for add

tion and other harms: tobacco3 and alcohol.4

With these data, researchers have proposed po

icy frameworks for cannabis.28–30,34

For our analysis, we built on previous

work,29,35–38

using a framework created by Can-

adian public health researchers2 that was based

on a report by the Health Officers Council

British Columbia.5 We included jurisdictions

with well-articulated cannabis policies and regu

lations, which we analyzed from a public health

perspective using a systematic method (Table

Uruguay

Uruguay follows the key public health best prac

tices.40 It has established a central, governmenta

arm’s length commission to purchase cannabis

from producers and sell to distributors. The com

mission will have control over production, qual

and prices, and the ability to undercut the illeg

market.41 Uruguay has banned cannabis-impaired

driving and has set the cut-off for impaired driv

ing to a serum tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) leve

of 10 ng/mL. Because of its zero-tolerance polic

for alcohol-impaired driving, the country has cr

ated a lower threshold for the combination of c

nabis and alcohol. Tax revenues will fund t

commission and a public health campaign. (Ca

nabis will initially be sold tax free to undercut t

illegal market.) Uruguay bans all promotion of

cannabis products. Pharmacies will sell bulk ca

nabis in plain bags, labelled only with the THC

percentage and warnings. (Sales are slated to

early in 2016.) Individuals are permitted to gro

their own cannabis and to form growing co

operatives. People who purchase or grow cann

bis will be registered and fingerprinted to preve

1212 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

same rate, the latter are 3.73 times more likely to

be arrested for possession.16 Finally, society pays

with high policing, court and prison costs.15,17

Harms from regular cannabis use may be less

than those associated with other psychoactive

substances,18 but they are still substantial at a pop-

ulation level. At higher doses, cannabis is a well-

established risk for motor vehicle crashes.19,20

Combining alcohol with cannabis results in

greater impairment than either substance alone.21

A recent study estimated that 6825–20 475 inju-

ries from cannabis-attributed motor vehicle

crashes occur in Canada annually.19 Each year in

Canada, 76 000–95 000 people undergo cannabis

addiction treatment and 219–547 cannabis-related

deaths occur (from injuries in motor vehicle

crashes and lung disease).19 Youth are particularly

vulnerable to the effects of cannabis: regular users

frequently report loss of control over their canna-

bis use,22 have lower educational attainment23 and

may have, according to one cohort study, a drop

in IQ that persists into adulthood.24

Often the harms from prohibition versus harms

from potential increased use of cannabis are

falsely pitted against each other. Evidence shows,

however, that cannabis prohibition has no effect

on rates of use, at least in developed countries.25–28

Some have advocated for the removal of crimi-

nal penalties for possession instead of legalization.

With Portugal’s experience in decriminalizing can-

nabis, users benefit from reduced marginalization,

imprisonment and barriers to treatment, and soci-

ety benefits from reduced policing, court and

prison costs.17 The illegal supply chain, however,

continues to fund criminal activity. In addition, be-

cause the government does not control the produc-

tion, processing, supply or price of cannabis, it has

a limited ability to achieve public health goals.

What objectives should underpin

legalization?

If policy-makers opt to legalize cannabis, careful

planning and comprehensive governmental con-

trols would provide the greatest likelihood of

minimizing harms and maximizing benefits. A

cannabis legalization framework should explic-

itly state that public health promotion and pro-

tection are its primary goals. It should list spe-

cific objectives,5,29,30

including delayed onset of

use by youth; reduced demand; reduced risky

use (e.g., reduced impaired driving); decreased

rates of problematic use, addiction and concur-

rent risky use of other substances; reduced con-

sumption of products with contaminants and un-

certain potency; increased public safety (e.g.,

reduced drug-related crime); reduced discrimina-

tion, stigmatization and marginalization of user

and realization of therapeutic benefits.

A frequently cited concern with legalization i

that it will allow the rise of Big Cannabis,31 simi-

lar to Big Tobacco and Big Alcohol. These pow-

erful multinational corporations have revenu

and market expansion as their primary goals, w

little consideration of the impact on public hea

They increase tobacco and alcohol use by lobb

ing for favourable regulations32 and funding huge

marketing campaigns.33 It is important that the

regulations actively work against the establish-

ment of Big Cannabis.

Evaluating cannabis regulations

through a public health lens

There is scant direct evidence to guide the cre-

ation of public health–oriented cannabis policie

Fortunately, there is an extensive evidence bas

for two other substances with potential for add

tion and other harms: tobacco3 and alcohol.4

With these data, researchers have proposed po

icy frameworks for cannabis.28–30,34

For our analysis, we built on previous

work,29,35–38

using a framework created by Can-

adian public health researchers2 that was based

on a report by the Health Officers Council

British Columbia.5 We included jurisdictions

with well-articulated cannabis policies and regu

lations, which we analyzed from a public health

perspective using a systematic method (Table

Uruguay

Uruguay follows the key public health best prac

tices.40 It has established a central, governmenta

arm’s length commission to purchase cannabis

from producers and sell to distributors. The com

mission will have control over production, qual

and prices, and the ability to undercut the illeg

market.41 Uruguay has banned cannabis-impaired

driving and has set the cut-off for impaired driv

ing to a serum tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) leve

of 10 ng/mL. Because of its zero-tolerance polic

for alcohol-impaired driving, the country has cr

ated a lower threshold for the combination of c

nabis and alcohol. Tax revenues will fund t

commission and a public health campaign. (Ca

nabis will initially be sold tax free to undercut t

illegal market.) Uruguay bans all promotion of

cannabis products. Pharmacies will sell bulk ca

nabis in plain bags, labelled only with the THC

percentage and warnings. (Sales are slated to

early in 2016.) Individuals are permitted to gro

their own cannabis and to form growing co

operatives. People who purchase or grow cann

bis will be registered and fingerprinted to preve

Analysis

CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1213

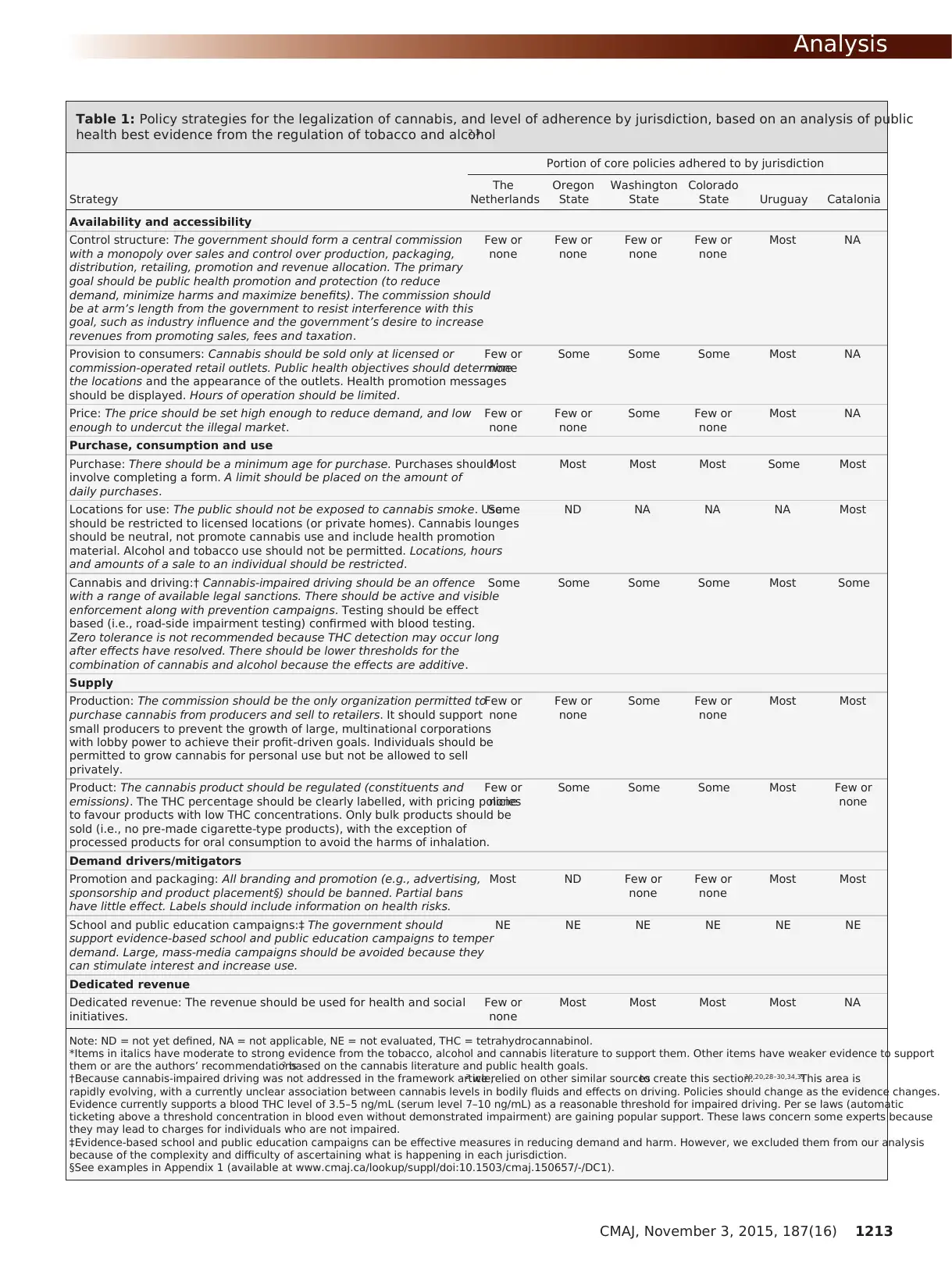

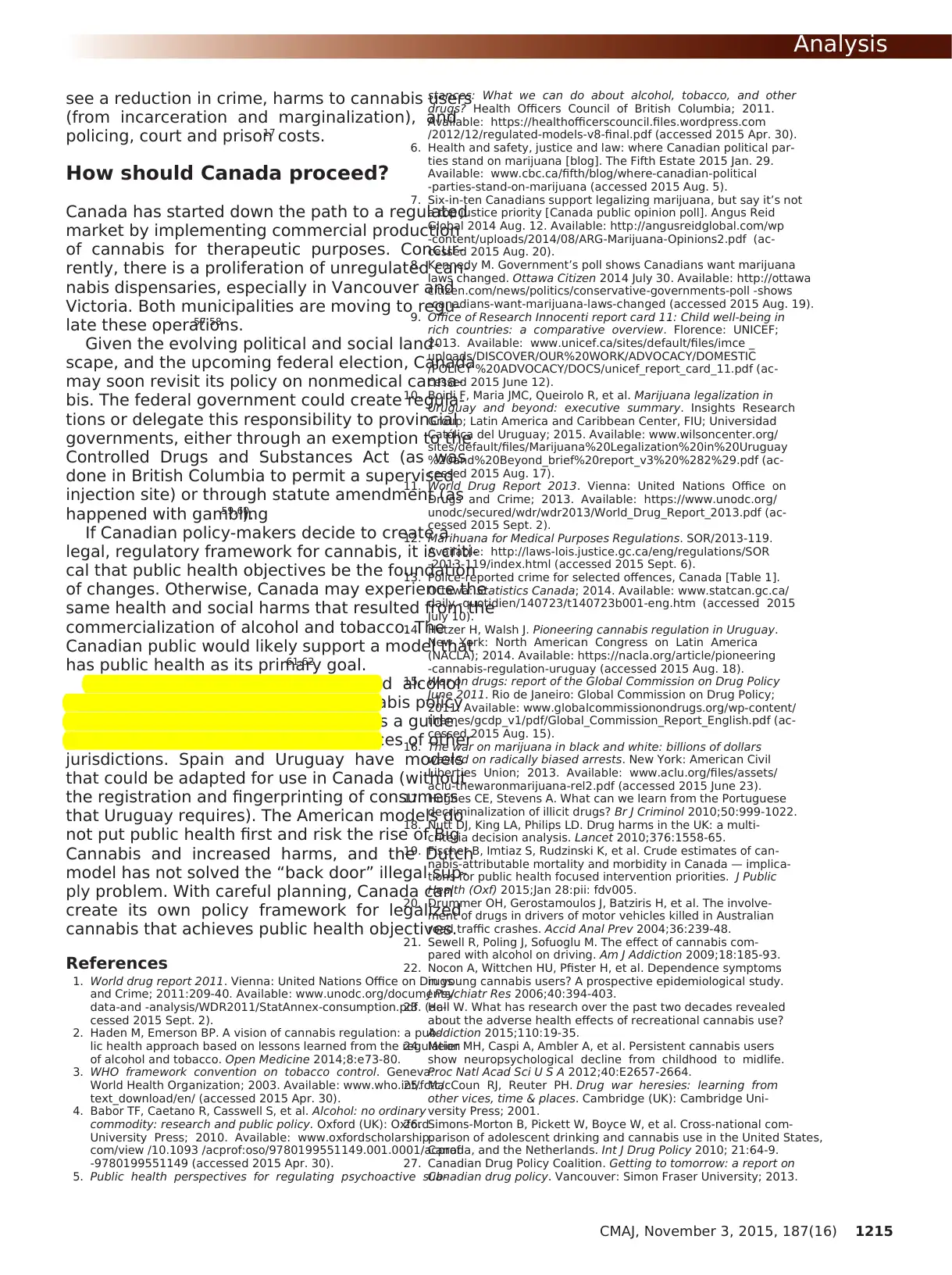

Table 1: Policy strategies for the legalization of cannabis, and level of adherence by jurisdiction, based on an analysis of public

health best evidence from the regulation of tobacco and alcohol2,3

Portion of core policies adhered to by jurisdiction

Strategy

The

Netherlands

Oregon

State

Washington

State

Colorado

State Uruguay Catalonia

Availability and accessibility

Control structure: The government should form a central commission

with a monopoly over sales and control over production, packaging,

distribution, retailing, promotion and revenue allocation. The primary

goal should be public health promotion and protection (to reduce

demand, minimize harms and maximize benefits). The commission should

be at arm’s length from the government to resist interference with this

goal, such as industry influence and the government’s desire to increase

revenues from promoting sales, fees and taxation.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Few or

none

Few or

none

Most NA

Provision to consumers: Cannabis should be sold only at licensed or

commission-operated retail outlets. Public health objectives should determine

the locations and the appearance of the outlets. Health promotion messages

should be displayed. Hours of operation should be limited.

Few or

none

Some Some Some Most NA

Price: The price should be set high enough to reduce demand, and low

enough to undercut the illegal market.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Some Few or

none

Most NA

Purchase, consumption and use

Purchase: There should be a minimum age for purchase. Purchases should

involve completing a form. A limit should be placed on the amount of

daily purchases.

Most Most Most Most Some Most

Locations for use: The public should not be exposed to cannabis smoke. Use

should be restricted to licensed locations (or private homes). Cannabis lounges

should be neutral, not promote cannabis use and include health promotion

material. Alcohol and tobacco use should not be permitted. Locations, hours

and amounts of a sale to an individual should be restricted.

Some ND NA NA NA Most

Cannabis and driving:† Cannabis-impaired driving should be an offence

with a range of available legal sanctions. There should be active and visible

enforcement along with prevention campaigns. Testing should be effect

based (i.e., road-side impairment testing) confirmed with blood testing.

Zero tolerance is not recommended because THC detection may occur long

after effects have resolved. There should be lower thresholds for the

combination of cannabis and alcohol because the effects are additive.

Some Some Some Some Most Some

Supply

Production: The commission should be the only organization permitted to

purchase cannabis from producers and sell to retailers. It should support

small producers to prevent the growth of large, multinational corporations

with lobby power to achieve their profit-driven goals. Individuals should be

permitted to grow cannabis for personal use but not be allowed to sell

privately.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Some Few or

none

Most Most

Product: The cannabis product should be regulated (constituents and

emissions). The THC percentage should be clearly labelled, with pricing policies

to favour products with low THC concentrations. Only bulk products should be

sold (i.e., no pre-made cigarette-type products), with the exception of

processed products for oral consumption to avoid the harms of inhalation.

Few or

none

Some Some Some Most Few or

none

Demand drivers/mitigators

Promotion and packaging: All branding and promotion (e.g., advertising,

sponsorship and product placement§) should be banned. Partial bans

have little effect. Labels should include information on health risks.

Most ND Few or

none

Few or

none

Most Most

School and public education campaigns:‡ The government should

support evidence-based school and public education campaigns to temper

demand. Large, mass-media campaigns should be avoided because they

can stimulate interest and increase use.

NE NE NE NE NE NE

Dedicated revenue

Dedicated revenue: The revenue should be used for health and social

initiatives.

Few or

none

Most Most Most Most NA

Note: ND = not yet defined, NA = not applicable, NE = not evaluated, THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

*Items in italics have moderate to strong evidence from the tobacco, alcohol and cannabis literature to support them. Other items have weaker evidence to support

them or are the authors’ recommendations2 based on the cannabis literature and public health goals.

†Because cannabis-impaired driving was not addressed in the framework article,2 we relied on other similar sourcesto create this section.19,20,28–30,34,39

This area is

rapidly evolving, with a currently unclear association between cannabis levels in bodily fluids and effects on driving. Policies should change as the evidence changes.

Evidence currently supports a blood THC level of 3.5–5 ng/mL (serum level 7–10 ng/mL) as a reasonable threshold for impaired driving. Per se laws (automatic

ticketing above a threshold concentration in blood even without demonstrated impairment) are gaining popular support. These laws concern some experts because

they may lead to charges for individuals who are not impaired.

‡Evidence-based school and public education campaigns can be effective measures in reducing demand and harm. However, we excluded them from our analysis

because of the complexity and difficulty of ascertaining what is happening in each jurisdiction.

§See examples in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150657/-/DC1).

CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1213

Table 1: Policy strategies for the legalization of cannabis, and level of adherence by jurisdiction, based on an analysis of public

health best evidence from the regulation of tobacco and alcohol2,3

Portion of core policies adhered to by jurisdiction

Strategy

The

Netherlands

Oregon

State

Washington

State

Colorado

State Uruguay Catalonia

Availability and accessibility

Control structure: The government should form a central commission

with a monopoly over sales and control over production, packaging,

distribution, retailing, promotion and revenue allocation. The primary

goal should be public health promotion and protection (to reduce

demand, minimize harms and maximize benefits). The commission should

be at arm’s length from the government to resist interference with this

goal, such as industry influence and the government’s desire to increase

revenues from promoting sales, fees and taxation.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Few or

none

Few or

none

Most NA

Provision to consumers: Cannabis should be sold only at licensed or

commission-operated retail outlets. Public health objectives should determine

the locations and the appearance of the outlets. Health promotion messages

should be displayed. Hours of operation should be limited.

Few or

none

Some Some Some Most NA

Price: The price should be set high enough to reduce demand, and low

enough to undercut the illegal market.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Some Few or

none

Most NA

Purchase, consumption and use

Purchase: There should be a minimum age for purchase. Purchases should

involve completing a form. A limit should be placed on the amount of

daily purchases.

Most Most Most Most Some Most

Locations for use: The public should not be exposed to cannabis smoke. Use

should be restricted to licensed locations (or private homes). Cannabis lounges

should be neutral, not promote cannabis use and include health promotion

material. Alcohol and tobacco use should not be permitted. Locations, hours

and amounts of a sale to an individual should be restricted.

Some ND NA NA NA Most

Cannabis and driving:† Cannabis-impaired driving should be an offence

with a range of available legal sanctions. There should be active and visible

enforcement along with prevention campaigns. Testing should be effect

based (i.e., road-side impairment testing) confirmed with blood testing.

Zero tolerance is not recommended because THC detection may occur long

after effects have resolved. There should be lower thresholds for the

combination of cannabis and alcohol because the effects are additive.

Some Some Some Some Most Some

Supply

Production: The commission should be the only organization permitted to

purchase cannabis from producers and sell to retailers. It should support

small producers to prevent the growth of large, multinational corporations

with lobby power to achieve their profit-driven goals. Individuals should be

permitted to grow cannabis for personal use but not be allowed to sell

privately.

Few or

none

Few or

none

Some Few or

none

Most Most

Product: The cannabis product should be regulated (constituents and

emissions). The THC percentage should be clearly labelled, with pricing policies

to favour products with low THC concentrations. Only bulk products should be

sold (i.e., no pre-made cigarette-type products), with the exception of

processed products for oral consumption to avoid the harms of inhalation.

Few or

none

Some Some Some Most Few or

none

Demand drivers/mitigators

Promotion and packaging: All branding and promotion (e.g., advertising,

sponsorship and product placement§) should be banned. Partial bans

have little effect. Labels should include information on health risks.

Most ND Few or

none

Few or

none

Most Most

School and public education campaigns:‡ The government should

support evidence-based school and public education campaigns to temper

demand. Large, mass-media campaigns should be avoided because they

can stimulate interest and increase use.

NE NE NE NE NE NE

Dedicated revenue

Dedicated revenue: The revenue should be used for health and social

initiatives.

Few or

none

Most Most Most Most NA

Note: ND = not yet defined, NA = not applicable, NE = not evaluated, THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

*Items in italics have moderate to strong evidence from the tobacco, alcohol and cannabis literature to support them. Other items have weaker evidence to support

them or are the authors’ recommendations2 based on the cannabis literature and public health goals.

†Because cannabis-impaired driving was not addressed in the framework article,2 we relied on other similar sourcesto create this section.19,20,28–30,34,39

This area is

rapidly evolving, with a currently unclear association between cannabis levels in bodily fluids and effects on driving. Policies should change as the evidence changes.

Evidence currently supports a blood THC level of 3.5–5 ng/mL (serum level 7–10 ng/mL) as a reasonable threshold for impaired driving. Per se laws (automatic

ticketing above a threshold concentration in blood even without demonstrated impairment) are gaining popular support. These laws concern some experts because

they may lead to charges for individuals who are not impaired.

‡Evidence-based school and public education campaigns can be effective measures in reducing demand and harm. However, we excluded them from our analysis

because of the complexity and difficulty of ascertaining what is happening in each jurisdiction.

§See examples in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150657/-/DC1).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Analysis

1214 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

consumers from buying more than 480 g per year.

This approach, however, gives rise to concerns

around privacy and may encourage some to pur-

chase cannabis from the illegal market.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has a complex system gov-

erned by accepted practice rather than explicit

policy. It decriminalized cannabis almost 40

years ago. Around the same time, it started to

tolerate the buying and selling of small amounts

in strictly controlled locations (the production

and importing of cannabis remains illegal).42 As

long as these coffee shops sold small amounts,

did not advertise or market, did not sell to

minors and were “good neighbours,” they were

permitted to sell cannabis.43 This is still the

practice 40 years later, and the Netherlands con-

tinues to struggle with the “back door” problem

of an illegal supply chain.44 The government

does not control production, packaging or price,

nor is it able to legally tax cannabis products.

The illegal supply chain continues to fund the

illegal market. The government does, however,

ban all promotion. This ban may be an impor-

tant contributor to the low rates of use among

youth in the Netherlands.

Spain

Spain has taken a different approach: it permits

people to grow their own cannabis but prohibits

private for-profit cannabis enterprises.45 The coun-

try’s Supreme Court ruling in the 1970s opened

the door for nonprofit cannabis co-operatives, or

cannabis social clubs. The first such club opened

in Barcelona in 2001, and until recently, the clubs

were guided by voluntary adherence to a code of

practice. Many clubs, however, had lax enforce-

ment of the membership rules. As a result, the

government in Catalonia (an autonomous region in

Spain where most of the cannabis social clubs are

located) recently passed recommendations to

guide municipalities in licensing the clubs.46,47

These recommendations include limits on monthly

personal amounts of cannabis, hours of operation

and membership. They also ban all promotion.

Catalonia’s approach uses elements of a public

health framework and eliminates the risk of harms

associated with the involvement of profit-driven

corporations. However, because production and

use occur in private locations, the government has

limited ability to ensure safety and quality, and to

ensure that the focus remains on public health

promotion inside the club doors. In addition,

because the model restricts access to people who

grow cannabis for personal use or are invited into

a cannabis social club, some people may be

excluded from obtaining cannabis legally.

Oregon, Washington State, Colorado

The US states of Oregon, Washington and Colo

rado all have an arm’s-length commission to cr

and police cannabis policies, and to license pro

ducers and sellers.48–51The commissions control

the sellers’ locations and hours and amount of

sales, and they prohibit sales to people less tha

years old. The states ban cannabis-impaired dr

ing. Washington and Colorado have per se laws

with automatic ticketing for a blood THC conce

tration above 5 ng/mL. Colorado allows drivers

rebut the charges if they can show they were n

impaired. All three states control the product c

stituents and set labelling requirements. They

mit the sale of pre-made cigarette-type cannab

products, not just bulk products. Most revenue

earmarked for health and social programs.

The commissions do not have a monopoly on

supply. (This monopoly model has precedent in

the US: many states have a central governmen

monopoly for liquor). Instead, the states permi

rect sales from producers to retailers. Colorado

and Oregon go one step further and permit pro

ducers to be retailers. The commissions therefo

have little control over supply and prices. In ad

tion, they do not control cannabis taxation and

must appeal to the state legislature for change

Accordingly, Colorado and Washington State in

tially struggled with a price of legal cannabis th

was much higher than the price of illegal canna

bis. If the price of legal cannabis falls because

more efficient production, the opposite problem

may occur: cheap legal cannabis, a known de-

mand driver.52 Washington State has taken steps

to counteract the lack of control and the risk of

oversupply by limiting the number of producer

and total production capacity.53

The states have set few controls over other d

mand drivers. Washington and Colorado permi

forms of promotion (advertising, branding and

sponsorship) with few limits except on promoti

to youth. Colorado asks industry “to refrain fro

advertising where more than approximately 30

percent of the audience is reasonably expected

be under the age of 21.”50 Washington’s regula-

tions state that youth under age 21 should not

exposed to mass-media advertising, but they d

not explain how this is to be done.54 The states are

hampered in creating stricter regulations by co

tutional protection of commercial free speech.55,56

Because the states have limited control over

supply and price, and permit promotion, there

little to stop the rise of Big Cannabis and its as

ciated lobbying and marketing power. Washing

ton State may be somewhat protected with lim

it has placed on producer size and production.

states are at risk of an increase in cannabis use

over time. On the positive side, these states sh

1214 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

consumers from buying more than 480 g per year.

This approach, however, gives rise to concerns

around privacy and may encourage some to pur-

chase cannabis from the illegal market.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has a complex system gov-

erned by accepted practice rather than explicit

policy. It decriminalized cannabis almost 40

years ago. Around the same time, it started to

tolerate the buying and selling of small amounts

in strictly controlled locations (the production

and importing of cannabis remains illegal).42 As

long as these coffee shops sold small amounts,

did not advertise or market, did not sell to

minors and were “good neighbours,” they were

permitted to sell cannabis.43 This is still the

practice 40 years later, and the Netherlands con-

tinues to struggle with the “back door” problem

of an illegal supply chain.44 The government

does not control production, packaging or price,

nor is it able to legally tax cannabis products.

The illegal supply chain continues to fund the

illegal market. The government does, however,

ban all promotion. This ban may be an impor-

tant contributor to the low rates of use among

youth in the Netherlands.

Spain

Spain has taken a different approach: it permits

people to grow their own cannabis but prohibits

private for-profit cannabis enterprises.45 The coun-

try’s Supreme Court ruling in the 1970s opened

the door for nonprofit cannabis co-operatives, or

cannabis social clubs. The first such club opened

in Barcelona in 2001, and until recently, the clubs

were guided by voluntary adherence to a code of

practice. Many clubs, however, had lax enforce-

ment of the membership rules. As a result, the

government in Catalonia (an autonomous region in

Spain where most of the cannabis social clubs are

located) recently passed recommendations to

guide municipalities in licensing the clubs.46,47

These recommendations include limits on monthly

personal amounts of cannabis, hours of operation

and membership. They also ban all promotion.

Catalonia’s approach uses elements of a public

health framework and eliminates the risk of harms

associated with the involvement of profit-driven

corporations. However, because production and

use occur in private locations, the government has

limited ability to ensure safety and quality, and to

ensure that the focus remains on public health

promotion inside the club doors. In addition,

because the model restricts access to people who

grow cannabis for personal use or are invited into

a cannabis social club, some people may be

excluded from obtaining cannabis legally.

Oregon, Washington State, Colorado

The US states of Oregon, Washington and Colo

rado all have an arm’s-length commission to cr

and police cannabis policies, and to license pro

ducers and sellers.48–51The commissions control

the sellers’ locations and hours and amount of

sales, and they prohibit sales to people less tha

years old. The states ban cannabis-impaired dr

ing. Washington and Colorado have per se laws

with automatic ticketing for a blood THC conce

tration above 5 ng/mL. Colorado allows drivers

rebut the charges if they can show they were n

impaired. All three states control the product c

stituents and set labelling requirements. They

mit the sale of pre-made cigarette-type cannab

products, not just bulk products. Most revenue

earmarked for health and social programs.

The commissions do not have a monopoly on

supply. (This monopoly model has precedent in

the US: many states have a central governmen

monopoly for liquor). Instead, the states permi

rect sales from producers to retailers. Colorado

and Oregon go one step further and permit pro

ducers to be retailers. The commissions therefo

have little control over supply and prices. In ad

tion, they do not control cannabis taxation and

must appeal to the state legislature for change

Accordingly, Colorado and Washington State in

tially struggled with a price of legal cannabis th

was much higher than the price of illegal canna

bis. If the price of legal cannabis falls because

more efficient production, the opposite problem

may occur: cheap legal cannabis, a known de-

mand driver.52 Washington State has taken steps

to counteract the lack of control and the risk of

oversupply by limiting the number of producer

and total production capacity.53

The states have set few controls over other d

mand drivers. Washington and Colorado permi

forms of promotion (advertising, branding and

sponsorship) with few limits except on promoti

to youth. Colorado asks industry “to refrain fro

advertising where more than approximately 30

percent of the audience is reasonably expected

be under the age of 21.”50 Washington’s regula-

tions state that youth under age 21 should not

exposed to mass-media advertising, but they d

not explain how this is to be done.54 The states are

hampered in creating stricter regulations by co

tutional protection of commercial free speech.55,56

Because the states have limited control over

supply and price, and permit promotion, there

little to stop the rise of Big Cannabis and its as

ciated lobbying and marketing power. Washing

ton State may be somewhat protected with lim

it has placed on producer size and production.

states are at risk of an increase in cannabis use

over time. On the positive side, these states sh

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Analysis

CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1215

see a reduction in crime, harms to cannabis users

(from incarceration and marginalization), and

policing, court and prison costs.17

How should Canada proceed?

Canada has started down the path to a regulated

market by implementing commercial production

of cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Concur-

rently, there is a proliferation of unregulated can-

nabis dispensaries, especially in Vancouver and

Victoria. Both municipalities are moving to regu-

late these operations.57,58

Given the evolving political and social land-

scape, and the upcoming federal election, Canada

may soon revisit its policy on nonmedical canna-

bis. The federal government could create regula-

tions or delegate this responsibility to provincial

governments, either through an exemption to the

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (as was

done in British Columbia to permit a supervised

injection site) or through statute amendment (as

happened with gambling59,60

).

If Canadian policy-makers decide to create a

legal, regulatory framework for cannabis, it is criti-

cal that public health objectives be the foundation

of changes. Otherwise, Canada may experience the

same health and social harms that resulted from the

commercialization of alcohol and tobacco. The

Canadian public would likely support a model that

has public health as its primary goal.61,62

Policy-makers can use tobacco and alcohol

research and the frameworks for cannabis policy

created by public health researchers as a guide.

They can also learn from the experiences of other

jurisdictions. Spain and Uruguay have models

that could be adapted for use in Canada (without

the registration and fingerprinting of consumers

that Uruguay requires). The American models do

not put public health first and risk the rise of Big

Cannabis and increased harms, and the Dutch

model has not solved the “back door” illegal sup-

ply problem. With careful planning, Canada can

create its own policy framework for legalized

cannabis that achieves public health objectives.

References

1. World drug report 2011. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime; 2011:209-40. Available: www.unodc.org/documents/

data-and -analysis/WDR2011/StatAnnex-consumption.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Sept. 2).

2. Haden M, Emerson BP. A vision of cannabis regulation: a pub-

lic health approach based on lessons learned from the regulation

of alcohol and tobacco. Open Medicine 2014;8:e73-80.

3. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva:

World Health Organization; 2003. Available: www.who.int/fctc/

text_download/en/ (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

4. Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary

commodity: research and public policy. Oxford (UK): Oxford

University Press; 2010. Available: www.oxfordscholarship.

com/view /10.1093 /acprof:oso/9780199551149.001.0001/acprof

-9780199551149 (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

5. Public health perspectives for regulating psychoactive sub-

stances: What we can do about alcohol, tobacco, and other

drugs? Health Officers Council of British Columbia; 2011.

Available: https://healthofficerscouncil.files.wordpress.com

/2012/12/regulated-models-v8-final.pdf (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

6. Health and safety, justice and law: where Canadian political par-

ties stand on marijuana [blog]. The Fifth Estate 2015 Jan. 29.

Available: www.cbc.ca/fifth/blog/where-canadian-political

-parties-stand-on-marijuana (accessed 2015 Aug. 5).

7. Six-in-ten Canadians support legalizing marijuana, but say it’s not

a top justice priority [Canada public opinion poll]. Angus Reid

Global 2014 Aug. 12. Available: http://angusreidglobal.com/wp

-content/uploads/2014/08/ARG-Marijuana-Opinions2.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 20).

8. Kennedy M. Government’s poll shows Canadians want marijuana

laws changed. Ottawa Citizen 2014 July 30. Available: http://ottawa

citizen.com/news/politics/conservative-governments-poll -shows

-canadians-want-marijuana-laws-changed (accessed 2015 Aug. 19).

9. Office of Research Innocenti report card 11: Child well-being in

rich countries: a comparative overview. Florence: UNICEF;

2013. Available: www.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/imce _

uploads/DISCOVER/OUR%20WORK/ADVOCACY/DOMESTIC

/POLICY %20ADVOCACY/DOCS/unicef_report_card_11.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 June 12).

10. Boidi F, Maria JMC, Queirolo R, et al. Marijuana legalization in

Uruguay and beyond: executive summary. Insights Research

Group; Latin America and Caribbean Center, FIU; Universidad

Católica del Uruguay; 2015. Available: www.wilsoncenter.org/

sites/default/files/Marijuana%20Legalization%20in%20Uruguay

%20and%20Beyond_brief%20report_v3%20%282%29.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 17).

11. World Drug Report 2013. Vienna: United Nations Office on

Drugs and Crime; 2013. Available: https://www.unodc.org/

unodc/secured/wdr/wdr2013/World_Drug_Report_2013.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Sept. 2).

12. Marihuana for Medical Purposes Regulations. SOR/2013-119.

Available: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR

-2013-119/index.html (accessed 2015 Sept. 6).

13. Police-reported crime for selected offences, Canada [Table 1].

Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2014. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/

daily -quotidien/140723/t140723b001-eng.htm (accessed 2015

July 10).

14. Hetzer H, Walsh J. Pioneering cannabis regulation in Uruguay.

New York: North American Congress on Latin America

(NACLA); 2014. Available: https://nacla.org/article/pioneering

-cannabis-regulation-uruguay (accessed 2015 Aug. 18).

15. War on drugs: report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy

June 2011. Rio de Janeiro: Global Commission on Drug Policy;

2011. Available: www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/wp-content/

themes/gcdp_v1/pdf/Global_Commission_Report_English.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 15).

16. The war on marijuana in black and white: billions of dollars

wasted on radically biased arrests. New York: American Civil

Liberties Union; 2013. Available: www.aclu.org/files/assets/

aclu-thewaronmarijuana-rel2.pdf (accessed 2015 June 23).

17. Hughes CE, Stevens A. What can we learn from the Portuguese

decriminalization of illicit drugs? Br J Criminol 2010;50:999-1022.

18. Nutt DJ, King LA, Philips LD. Drug harms in the UK: a multi-

criteria decision analysis. Lancet 2010;376:1558-65.

19. Fischer B, Imtiaz S, Rudzinski K, et al. Crude estimates of can-

nabis-attributable mortality and morbidity in Canada — implica-

tions for public health focused intervention priorities. J Public

Health (Oxf) 2015;Jan 28:pii: fdv005.

20. Drummer OH, Gerostamoulos J, Batziris H, et al. The involve-

ment of drugs in drivers of motor vehicles killed in Australian

road traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev 2004;36:239-48.

21. Sewell R, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis com-

pared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addiction 2009;18:185-93.

22. Nocon A, Wittchen HU, Pfister H, et al. Dependence symptoms

in young cannabis users? A prospective epidemiological study.

J Psychiatr Res 2006;40:394-403.

23. Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed

about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use?

Addiction 2015;110:19-35.

24. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users

show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;40:E2657-2664.

25. MacCoun RJ, Reuter PH. Drug war heresies: learning from

other vices, time & places. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge Uni-

versity Press; 2001.

26. Simons-Morton B, Pickett W, Boyce W, et al. Cross-national com-

parison of adolescent drinking and cannabis use in the United States,

Canada, and the Netherlands. Int J Drug Policy 2010; 21:64-9.

27. Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. Getting to tomorrow: a report on

Canadian drug policy. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University; 2013.

CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16) 1215

see a reduction in crime, harms to cannabis users

(from incarceration and marginalization), and

policing, court and prison costs.17

How should Canada proceed?

Canada has started down the path to a regulated

market by implementing commercial production

of cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Concur-

rently, there is a proliferation of unregulated can-

nabis dispensaries, especially in Vancouver and

Victoria. Both municipalities are moving to regu-

late these operations.57,58

Given the evolving political and social land-

scape, and the upcoming federal election, Canada

may soon revisit its policy on nonmedical canna-

bis. The federal government could create regula-

tions or delegate this responsibility to provincial

governments, either through an exemption to the

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (as was

done in British Columbia to permit a supervised

injection site) or through statute amendment (as

happened with gambling59,60

).

If Canadian policy-makers decide to create a

legal, regulatory framework for cannabis, it is criti-

cal that public health objectives be the foundation

of changes. Otherwise, Canada may experience the

same health and social harms that resulted from the

commercialization of alcohol and tobacco. The

Canadian public would likely support a model that

has public health as its primary goal.61,62

Policy-makers can use tobacco and alcohol

research and the frameworks for cannabis policy

created by public health researchers as a guide.

They can also learn from the experiences of other

jurisdictions. Spain and Uruguay have models

that could be adapted for use in Canada (without

the registration and fingerprinting of consumers

that Uruguay requires). The American models do

not put public health first and risk the rise of Big

Cannabis and increased harms, and the Dutch

model has not solved the “back door” illegal sup-

ply problem. With careful planning, Canada can

create its own policy framework for legalized

cannabis that achieves public health objectives.

References

1. World drug report 2011. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime; 2011:209-40. Available: www.unodc.org/documents/

data-and -analysis/WDR2011/StatAnnex-consumption.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Sept. 2).

2. Haden M, Emerson BP. A vision of cannabis regulation: a pub-

lic health approach based on lessons learned from the regulation

of alcohol and tobacco. Open Medicine 2014;8:e73-80.

3. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva:

World Health Organization; 2003. Available: www.who.int/fctc/

text_download/en/ (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

4. Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary

commodity: research and public policy. Oxford (UK): Oxford

University Press; 2010. Available: www.oxfordscholarship.

com/view /10.1093 /acprof:oso/9780199551149.001.0001/acprof

-9780199551149 (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

5. Public health perspectives for regulating psychoactive sub-

stances: What we can do about alcohol, tobacco, and other

drugs? Health Officers Council of British Columbia; 2011.

Available: https://healthofficerscouncil.files.wordpress.com

/2012/12/regulated-models-v8-final.pdf (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

6. Health and safety, justice and law: where Canadian political par-

ties stand on marijuana [blog]. The Fifth Estate 2015 Jan. 29.

Available: www.cbc.ca/fifth/blog/where-canadian-political

-parties-stand-on-marijuana (accessed 2015 Aug. 5).

7. Six-in-ten Canadians support legalizing marijuana, but say it’s not

a top justice priority [Canada public opinion poll]. Angus Reid

Global 2014 Aug. 12. Available: http://angusreidglobal.com/wp

-content/uploads/2014/08/ARG-Marijuana-Opinions2.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 20).

8. Kennedy M. Government’s poll shows Canadians want marijuana

laws changed. Ottawa Citizen 2014 July 30. Available: http://ottawa

citizen.com/news/politics/conservative-governments-poll -shows

-canadians-want-marijuana-laws-changed (accessed 2015 Aug. 19).

9. Office of Research Innocenti report card 11: Child well-being in

rich countries: a comparative overview. Florence: UNICEF;

2013. Available: www.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/imce _

uploads/DISCOVER/OUR%20WORK/ADVOCACY/DOMESTIC

/POLICY %20ADVOCACY/DOCS/unicef_report_card_11.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 June 12).

10. Boidi F, Maria JMC, Queirolo R, et al. Marijuana legalization in

Uruguay and beyond: executive summary. Insights Research

Group; Latin America and Caribbean Center, FIU; Universidad

Católica del Uruguay; 2015. Available: www.wilsoncenter.org/

sites/default/files/Marijuana%20Legalization%20in%20Uruguay

%20and%20Beyond_brief%20report_v3%20%282%29.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 17).

11. World Drug Report 2013. Vienna: United Nations Office on

Drugs and Crime; 2013. Available: https://www.unodc.org/

unodc/secured/wdr/wdr2013/World_Drug_Report_2013.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Sept. 2).

12. Marihuana for Medical Purposes Regulations. SOR/2013-119.

Available: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR

-2013-119/index.html (accessed 2015 Sept. 6).

13. Police-reported crime for selected offences, Canada [Table 1].

Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2014. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/

daily -quotidien/140723/t140723b001-eng.htm (accessed 2015

July 10).

14. Hetzer H, Walsh J. Pioneering cannabis regulation in Uruguay.

New York: North American Congress on Latin America

(NACLA); 2014. Available: https://nacla.org/article/pioneering

-cannabis-regulation-uruguay (accessed 2015 Aug. 18).

15. War on drugs: report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy

June 2011. Rio de Janeiro: Global Commission on Drug Policy;

2011. Available: www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/wp-content/

themes/gcdp_v1/pdf/Global_Commission_Report_English.pdf (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 15).

16. The war on marijuana in black and white: billions of dollars

wasted on radically biased arrests. New York: American Civil

Liberties Union; 2013. Available: www.aclu.org/files/assets/

aclu-thewaronmarijuana-rel2.pdf (accessed 2015 June 23).

17. Hughes CE, Stevens A. What can we learn from the Portuguese

decriminalization of illicit drugs? Br J Criminol 2010;50:999-1022.

18. Nutt DJ, King LA, Philips LD. Drug harms in the UK: a multi-

criteria decision analysis. Lancet 2010;376:1558-65.

19. Fischer B, Imtiaz S, Rudzinski K, et al. Crude estimates of can-

nabis-attributable mortality and morbidity in Canada — implica-

tions for public health focused intervention priorities. J Public

Health (Oxf) 2015;Jan 28:pii: fdv005.

20. Drummer OH, Gerostamoulos J, Batziris H, et al. The involve-

ment of drugs in drivers of motor vehicles killed in Australian

road traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev 2004;36:239-48.

21. Sewell R, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis com-

pared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addiction 2009;18:185-93.

22. Nocon A, Wittchen HU, Pfister H, et al. Dependence symptoms

in young cannabis users? A prospective epidemiological study.

J Psychiatr Res 2006;40:394-403.

23. Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed

about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use?

Addiction 2015;110:19-35.

24. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users

show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;40:E2657-2664.

25. MacCoun RJ, Reuter PH. Drug war heresies: learning from

other vices, time & places. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge Uni-

versity Press; 2001.

26. Simons-Morton B, Pickett W, Boyce W, et al. Cross-national com-

parison of adolescent drinking and cannabis use in the United States,

Canada, and the Netherlands. Int J Drug Policy 2010; 21:64-9.

27. Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. Getting to tomorrow: a report on

Canadian drug policy. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University; 2013.

Analysis

1216 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

28. Room R, Fischer B, Hall W, et al. Cannabis policy: moving beyond

stalemate. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press/Beckley Founda-

tion Press; 2010.

29. Rolles S, Murkin G. How to regulate cannabis: a practical guide.

Bristol (UK): Transform Drug Policy Foundation; 2013. Avail-

able: www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016/Contributions/Civil/

Transform-Drug-Policy-Foundation/How-to-Regulate-Cannabis

-Guide.pdf (accessed 2015 Aug. 16).

30. Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, et al. Developing public

health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and

tobacco. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1021-8.

31. Carroll R. Big Cannabis: Will legal weed grow to be America’s

next corporate titan? The Guardian [UK] 2014 Jan. 3. Available:

www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jan/03/legal-marijuana

-colorado-big-tobacco-lobbying (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

32. Gornall J. Europe under the Influence. BMJ 2014;348:g1166.

33. Jernigan DH. The global alcohol industry: an overview. Addic-

tion 2009;104(Suppl 1):6-12.

34. Cannabis policy framework. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and

Mental Health; 2014. Available: www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_

camh/influencing_public_policy/Documents/CAMHCannabis

PolicyFramework.pdf (accessed 2015 June 12).

35. Room R. Legalizing a market for cannabis for pleasure: Colorado,

Washington, Uruguay and beyond. Addiction 2014;109:345-51.

36. Pardo B. Cannabis policy reforms in the Americas: a compara-

tive analysis of Colorado, Washington, and Uruguay. Int J Drug

Policy 2014;25:727-35.

37. Kilmer B, Kruithof K, Pardal M, et al. Multinational overview of

cannabis production regimes. Research and Documentation

Centre (WODC), Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice; 2013.

Available: www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR510.html

(accessed 2015 June 12).

38. Walsh J, Ramsey G. Uruguay’s drug policy: major innovations,

major challenges. Washington (DC): Brookings/WALA; 2015.

Available: www.brookings.edu/~/media/Research/Files/Papers

/2015/04/global-drug-policy/Walsh--Uruguay-final.pdf?la=en (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 14).

39. Grotenhermen F, Leson G, Berghaus G, et al. Developing limits

for driving under cannabis. Addiction 2007;102:1910-7.

40. Marihuana y sus derivados: control y regulación del estado de

la importación, producción, adquisición, almacenamiento, com-

ercialización y distribución. Law no. 19.172. Senate and House

of Representatives of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, meeting

in Assembly General. Available: www.correo.com.uy/otrosdoc-

umentos/pdf/Ley_19.172.pdf (accessed 2015 June 2).

41. Castaldi M. Uruguay to sell marijuana tax-free to undercut

drug traffickers. Reuters 2014 May 19. Available: www.

reuters.com/article/2014/05/19/us-uruguay-marijuana

-idUSKBN0DZ17Z20140519 (accessed 2015 June 11).

42. Bieleman B, Nijkamp R, Reimer J, et al. Coffeeshops in Neder-

land 2012 [Dutch]. Groningen (the Netherlands): WODC, min-

isterie van Veiligheid en Justitie, Den Haag; 2013. Available:

http://voc-nederland.org/persberichten_pdf/rapport-coffeeshops

-in-nederland-2012-2.pdf (accessed 2015 Sept. 8).

43. Toleration policy regarding soft drugs and coffee shops. Govern-

ment of the Netherlands. Available: www.government.nl/topics/

drugs/contents/toleration-policy-regarding-soft-drugs-and-coffee

-shops (accessed 2015 June 4).

44. Police discover more marijuana plantations in Randstad region.

DutchNews.nl 2015 Jan. 15. Available: www.dutchnews.nl/news/

archives /2014/01/police_discover_more_marijuana/ (accessed

2015 May 29).

45. Murkin G. Cannabis social clubs in Spain: legalisation without

commercialization. Transform 2015 Jan. 6. Available: www.tdpf

.org .uk/blog/cannabis-social-clubs-spain-legalisation-without

-commercialisation #.VLeZjsGV5R8.twitter (accessed 2015

May 16).

46. Resolución Slt/32/2015, De 15 de enero, por la que se aprueban

criterios en materia de salud pública para orientar a las aso-

ciaciones cannábicas y sus clubes sociales y las condiciones del

ejercicio de su actividad para los ayuntamientos de Cataluña.

Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Official Gazette of the

Autonomous Government of Catalonia]. 2015 Jan. 29. Available:

http://portaldogc.gencat.cat/utilsEADOP/PDF/6799/1402549.pdf

(accessed 2015 Aug. 31).

47. Taylor H. Legislation passed to formally license Catalonia’s

cannabis clubs for first time. TalkingDrugs 2015 Feb. 3. Avail-

able: www.talkingdrugs.org/catalonia-cannabis-clubs-gain-formal

-licensing (accessed 2015 May 16).

48. Measure 91: Control, regulation, and taxation of marijuana and

industrial hemp act. People of the State of Oregon; 2014. Avail-

able: www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Documents /Measure91.

pdf (accessed 2015 May 22).

49. Colorado Amendment 64: Use and regulation of marijuana.

People of the State of Colorado; 2011. Available: www.fcgov.

com/mmj/pdf/amendment64.pdf (accessed 2015 May 11).

50. Marijuana Enforcement Division 1 CCR 212-2: Permanent rules

related to the Colorado Retail Marijuana Code. Denver: Colorad

Department of Revenue: Marijuana Enforcement Division;

2013:109. Available: www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/file

Retail%20Marijuana%20Rules,%20Adopted% 20090913,%20

Effective%20101513%5B1%5D_0.pdf (accessed 2015 May 12)

51. Initiative measure no. 502. People of the State of Washington;

2011. Available: http://sos.wa.gov/_assets/elections/initiatives/

i502.pdf (accessed 2015 May 23).

52. Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, MacCoun RJ, et al. Design consider-

ations for legalizing cannabis: lessons inspired by analysis of

California’s Proposition 19. Addiction 2012;107:865-71.

53. Liquor Control Board clarifies next steps in its preparation to is

sue marijuana licenses [press release]. Olympia (WA): Washing

ton State Liquor and Cannabis Board; 2014 Feb. 19. Available:

www.liq.wa.gov/content/liquor-control-board-clarifies -next-ste

-its-preparation-issue-marijuana-licenses (accessed 2015 May

54. Frequently asked questions about I-502 advertising. Olymp

(WA): Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board; 2015.

Available: http://liq.wa.gov/marijuana/faq_i502_advertising

#advertisingrules (accessed 2015 May 11).

55. Trans-High Corporation, D.B.A. High Times Magazine, The Daily

Doobie, LLC a corporate entity; and The Hemp Connoisseur, LLC,

a corporate entity v.The state of Colorado and John Hickenlooper

[civil action suit] 2013 May 29. Available: http://kln -law.

com/images /news_images/Marijuana-Magazines-Complaint .pd

(accessed 2015 June 17).

56. Kilmer B. 7 key questions on marijuana legalization [blog]. San

Monica (CA): Rand; 2013. Available: www.rand.org/blog

/2013/04/7-key-questions-on-marijuana-legalization.html (ac-

cessed 2015 June 17).

57. Bula F. Vancouver to become first city to regulate medical pot

pensaries. The Globe and Mail [Toronto] 2015 Apr. 22. Availabl

www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/vancouver-t

-become-first-city-to-regulate-medical-pot-dispensaries/article

24071461/%3b/ (accessed 2015 June 29).

58. Bailey I. Victoria mulling new bylaws for marijuana dispensarie

The Globe and Mail [Toronto] 2015 May 7. Available: www.

theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/victoria-mulling-n

-bylaws-for-marijuana-dispensaries/article24324753/ (accessed

2015 June 23).

59. Campbell CS, Smith GJ. Gambling in Canada — from vice to

disease to responsibility: a negotiated history. Can Bull Me

Hist 2003;20:121-49.

60. Lower the stakes: a public health approach to gambling in Briti

Columbia: Provincial health officer’s 2009 annual report. Victo-

ria: Office of the Provincial Health Officer BC; 2013. Available:

www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/DownloadAsset?assetId=EB445906BC214

EB4A44C1A075E3733&filename=gambling-in-bc.pdf (accessed

2015 June 21.

61. Majority supports study to evaluate taxation and regulation of

marijuana. Vancouver: Stop the Violence BC; 2013. Avail-

able: http://stoptheviolencebc.org/2013/04/18/majority-of

-british -columbians-support-pilot-study-to-evaluate-taxation-a

-regulation-of-marijuana (accessed 2015 Aug. 13).

62. Majority supports safe-injection sites. The Gazette [Montréal]

2008 June 7. Available: www.canada.com/montrealgazette/

story.html?id=f585e4fe-c262-41a8-b79a-d8329c379f26 (ac-

cessed 2015 June 5).

Affiliations: Department of Familiy Medicine (S. Spithoff)

Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Ont.; Division of Popu

lation and Public Health (Emerson), BC Ministry of Health,

Victoria, BC; Not For Sale — the Netherlands (A. Spithoff),

Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Contributors: Sheryl Spithoff conceived of and designed

article and wrote the first draft. Andrea Spithoff did most o

the acquisition of data and critically revised the article. Br

Emerson contributed substantially to the analysis and inte

pretation of data and critically revised the article. All of th

authors approved the final version to be published and ag

to act as guarantors of the work.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Raquel Peyrau

Rebecca Jesseman, Meldon Kahan and the Women’s Colleg

Academic Family Health Team Peer Support Writing Group

for reviewing and providing helpful suggestions on earlier

drafts of this paper. The authors also thank Pim Imenkamp

Laura Gutierrez and Rebecca Abavi for assisting in the bac

ground research for this paper.

Disclaimer: The opinions stated in this commentary

those of the authors and not of their affiliated organization

1216 CMAJ, November 3, 2015, 187(16)

28. Room R, Fischer B, Hall W, et al. Cannabis policy: moving beyond

stalemate. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press/Beckley Founda-

tion Press; 2010.

29. Rolles S, Murkin G. How to regulate cannabis: a practical guide.

Bristol (UK): Transform Drug Policy Foundation; 2013. Avail-

able: www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016/Contributions/Civil/

Transform-Drug-Policy-Foundation/How-to-Regulate-Cannabis

-Guide.pdf (accessed 2015 Aug. 16).

30. Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, et al. Developing public

health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and

tobacco. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1021-8.

31. Carroll R. Big Cannabis: Will legal weed grow to be America’s

next corporate titan? The Guardian [UK] 2014 Jan. 3. Available:

www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jan/03/legal-marijuana

-colorado-big-tobacco-lobbying (accessed 2015 Apr. 30).

32. Gornall J. Europe under the Influence. BMJ 2014;348:g1166.

33. Jernigan DH. The global alcohol industry: an overview. Addic-

tion 2009;104(Suppl 1):6-12.

34. Cannabis policy framework. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and

Mental Health; 2014. Available: www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_

camh/influencing_public_policy/Documents/CAMHCannabis

PolicyFramework.pdf (accessed 2015 June 12).

35. Room R. Legalizing a market for cannabis for pleasure: Colorado,

Washington, Uruguay and beyond. Addiction 2014;109:345-51.

36. Pardo B. Cannabis policy reforms in the Americas: a compara-

tive analysis of Colorado, Washington, and Uruguay. Int J Drug

Policy 2014;25:727-35.

37. Kilmer B, Kruithof K, Pardal M, et al. Multinational overview of

cannabis production regimes. Research and Documentation

Centre (WODC), Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice; 2013.

Available: www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR510.html

(accessed 2015 June 12).

38. Walsh J, Ramsey G. Uruguay’s drug policy: major innovations,

major challenges. Washington (DC): Brookings/WALA; 2015.

Available: www.brookings.edu/~/media/Research/Files/Papers

/2015/04/global-drug-policy/Walsh--Uruguay-final.pdf?la=en (ac-

cessed 2015 Aug. 14).

39. Grotenhermen F, Leson G, Berghaus G, et al. Developing limits

for driving under cannabis. Addiction 2007;102:1910-7.

40. Marihuana y sus derivados: control y regulación del estado de

la importación, producción, adquisición, almacenamiento, com-

ercialización y distribución. Law no. 19.172. Senate and House

of Representatives of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, meeting

in Assembly General. Available: www.correo.com.uy/otrosdoc-

umentos/pdf/Ley_19.172.pdf (accessed 2015 June 2).

41. Castaldi M. Uruguay to sell marijuana tax-free to undercut

drug traffickers. Reuters 2014 May 19. Available: www.

reuters.com/article/2014/05/19/us-uruguay-marijuana

-idUSKBN0DZ17Z20140519 (accessed 2015 June 11).

42. Bieleman B, Nijkamp R, Reimer J, et al. Coffeeshops in Neder-

land 2012 [Dutch]. Groningen (the Netherlands): WODC, min-

isterie van Veiligheid en Justitie, Den Haag; 2013. Available:

http://voc-nederland.org/persberichten_pdf/rapport-coffeeshops

-in-nederland-2012-2.pdf (accessed 2015 Sept. 8).

43. Toleration policy regarding soft drugs and coffee shops. Govern-

ment of the Netherlands. Available: www.government.nl/topics/

drugs/contents/toleration-policy-regarding-soft-drugs-and-coffee

-shops (accessed 2015 June 4).

44. Police discover more marijuana plantations in Randstad region.

DutchNews.nl 2015 Jan. 15. Available: www.dutchnews.nl/news/

archives /2014/01/police_discover_more_marijuana/ (accessed

2015 May 29).

45. Murkin G. Cannabis social clubs in Spain: legalisation without