Cantonese vs. English: A Linguistic Comparison and Personal Experience

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/23

|9

|2485

|21

Essay

AI Summary

This essay presents a comparative analysis of Cantonese and English languages, focusing on phonetics, grammar, and the influence of language on thought. The author, a native Cantonese speaker and learner of English as a second language, shares personal experiences and observations about the challenges and nuances of both languages. The essay delves into specific linguistic features such as fricatives, wh-movement, and nominal number agreement, highlighting the differences in how these concepts are expressed in each language. Furthermore, it explores how the structure of Cantonese and English affects the way speakers perceive time, referencing studies on bilingual individuals to demonstrate the interplay between language, culture, and cognition. The essay concludes by emphasizing the impact of language on abstract thought and the complexities of second language acquisition, noting that resources like this can be found on Desklib to aid in student learning and research.

Surname 1

Name

Tutor

Course

Date

Comparing English and Cantonese Language:

Introduction

This essay compares specific characteristics of Cantonese and English, and it highlights

certain things regarding the experience with English and Cantonese and how a persons’ ability in

such two languages is associated with such experiences. I am an international student from

Hong Kong. I speak Cantonese as my first language with English being my second language. My

native language is this Cantonese; however, I have been learning English as my second language

in school. I have my English-speaking friends in school, and this has encouraged me to learn

English as L2. I learned English-speaking from my classmates. This is because my English-

speaking friends were significantly speaking the English language in class and even during the

holidays when we went out together (Chan and David 52).

Non-Standard Language

I have always used some everyday American English slang in my communications. The

most common one is the “awesome”-as an adjective. I use it to express that something is

amazing or wonderful. I used in my sentences and a single word response. It is illustrated below:

When I am asked about my view on “Wolf of Wall Street,” my response has always been,

“It was awesome, and I love it!” This implies that the film is great in my view. I first heard of the

word when my fellow friend was asking about how he felt about a given, and he responded using

“awesome.”

Name

Tutor

Course

Date

Comparing English and Cantonese Language:

Introduction

This essay compares specific characteristics of Cantonese and English, and it highlights

certain things regarding the experience with English and Cantonese and how a persons’ ability in

such two languages is associated with such experiences. I am an international student from

Hong Kong. I speak Cantonese as my first language with English being my second language. My

native language is this Cantonese; however, I have been learning English as my second language

in school. I have my English-speaking friends in school, and this has encouraged me to learn

English as L2. I learned English-speaking from my classmates. This is because my English-

speaking friends were significantly speaking the English language in class and even during the

holidays when we went out together (Chan and David 52).

Non-Standard Language

I have always used some everyday American English slang in my communications. The

most common one is the “awesome”-as an adjective. I use it to express that something is

amazing or wonderful. I used in my sentences and a single word response. It is illustrated below:

When I am asked about my view on “Wolf of Wall Street,” my response has always been,

“It was awesome, and I love it!” This implies that the film is great in my view. I first heard of the

word when my fellow friend was asking about how he felt about a given, and he responded using

“awesome.”

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 2

Another slang I frequently use is the word “cool”- as an adjective. It implies “great” or

“fantastic. I always use it to show that I am okay with my idea. However, the standard meaning

of the word “cool” is a little cold. The example is: when I am asked about the weather in a given

place, I also say it is “cool.” I first heard of “cool” when my colleague replied as “cool” when

another friend asked him what he thought of her boyfriend.

The third slang I usually use is “wheels”-as a noun. Despite the many things with wheels,

however, when I refer to my wheels, I am always implying my car. For example, when my friend

asks me; “Would you pick me up at 4?” My reply has always been, “I am sorry, I wouldn’t

because I do not have my wheels.” I first heard of this slang from my friend who requested to be

picked up.

Comparison of Sounds: Fricatives

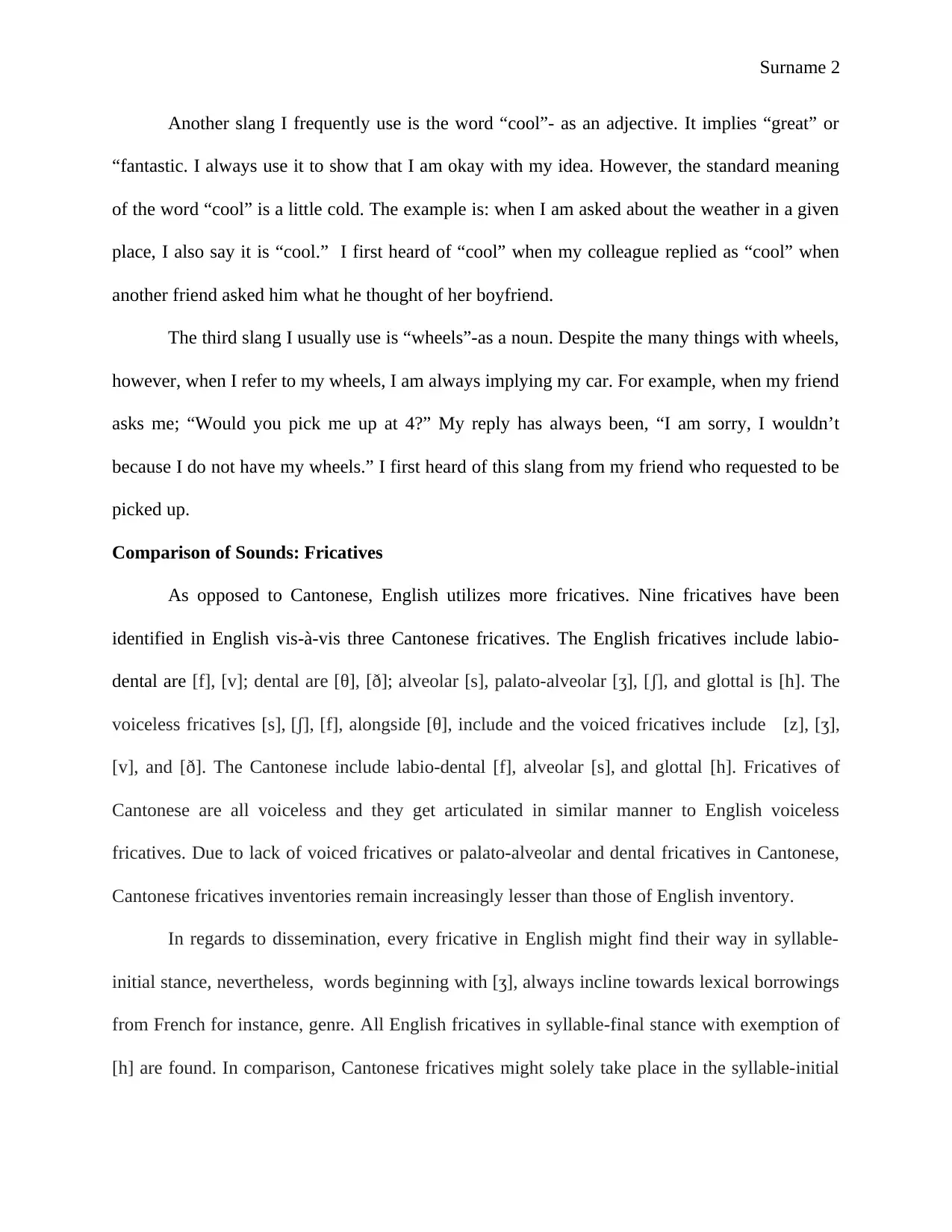

As opposed to Cantonese, English utilizes more fricatives. Nine fricatives have been

identified in English vis-à-vis three Cantonese fricatives. The English fricatives include labio-

dental are [f], [v]; dental are [θ], [ð]; alveolar [s], palato-alveolar [ʒ], [ʃ], and glottal is [h]. The

voiceless fricatives [s], [ʃ], [f], alongside [θ], include and the voiced fricatives include [z], [ʒ],

[v], and [ð]. The Cantonese include labio-dental [f], alveolar [s], and glottal [h]. Fricatives of

Cantonese are all voiceless and they get articulated in similar manner to English voiceless

fricatives. Due to lack of voiced fricatives or palato-alveolar and dental fricatives in Cantonese,

Cantonese fricatives inventories remain increasingly lesser than those of English inventory.

In regards to dissemination, every fricative in English might find their way in syllable-

initial stance, nevertheless, words beginning with [ʒ], always incline towards lexical borrowings

from French for instance, genre. All English fricatives in syllable-final stance with exemption of

[h] are found. In comparison, Cantonese fricatives might solely take place in the syllable-initial

Another slang I frequently use is the word “cool”- as an adjective. It implies “great” or

“fantastic. I always use it to show that I am okay with my idea. However, the standard meaning

of the word “cool” is a little cold. The example is: when I am asked about the weather in a given

place, I also say it is “cool.” I first heard of “cool” when my colleague replied as “cool” when

another friend asked him what he thought of her boyfriend.

The third slang I usually use is “wheels”-as a noun. Despite the many things with wheels,

however, when I refer to my wheels, I am always implying my car. For example, when my friend

asks me; “Would you pick me up at 4?” My reply has always been, “I am sorry, I wouldn’t

because I do not have my wheels.” I first heard of this slang from my friend who requested to be

picked up.

Comparison of Sounds: Fricatives

As opposed to Cantonese, English utilizes more fricatives. Nine fricatives have been

identified in English vis-à-vis three Cantonese fricatives. The English fricatives include labio-

dental are [f], [v]; dental are [θ], [ð]; alveolar [s], palato-alveolar [ʒ], [ʃ], and glottal is [h]. The

voiceless fricatives [s], [ʃ], [f], alongside [θ], include and the voiced fricatives include [z], [ʒ],

[v], and [ð]. The Cantonese include labio-dental [f], alveolar [s], and glottal [h]. Fricatives of

Cantonese are all voiceless and they get articulated in similar manner to English voiceless

fricatives. Due to lack of voiced fricatives or palato-alveolar and dental fricatives in Cantonese,

Cantonese fricatives inventories remain increasingly lesser than those of English inventory.

In regards to dissemination, every fricative in English might find their way in syllable-

initial stance, nevertheless, words beginning with [ʒ], always incline towards lexical borrowings

from French for instance, genre. All English fricatives in syllable-final stance with exemption of

[h] are found. In comparison, Cantonese fricatives might solely take place in the syllable-initial

Surname 3

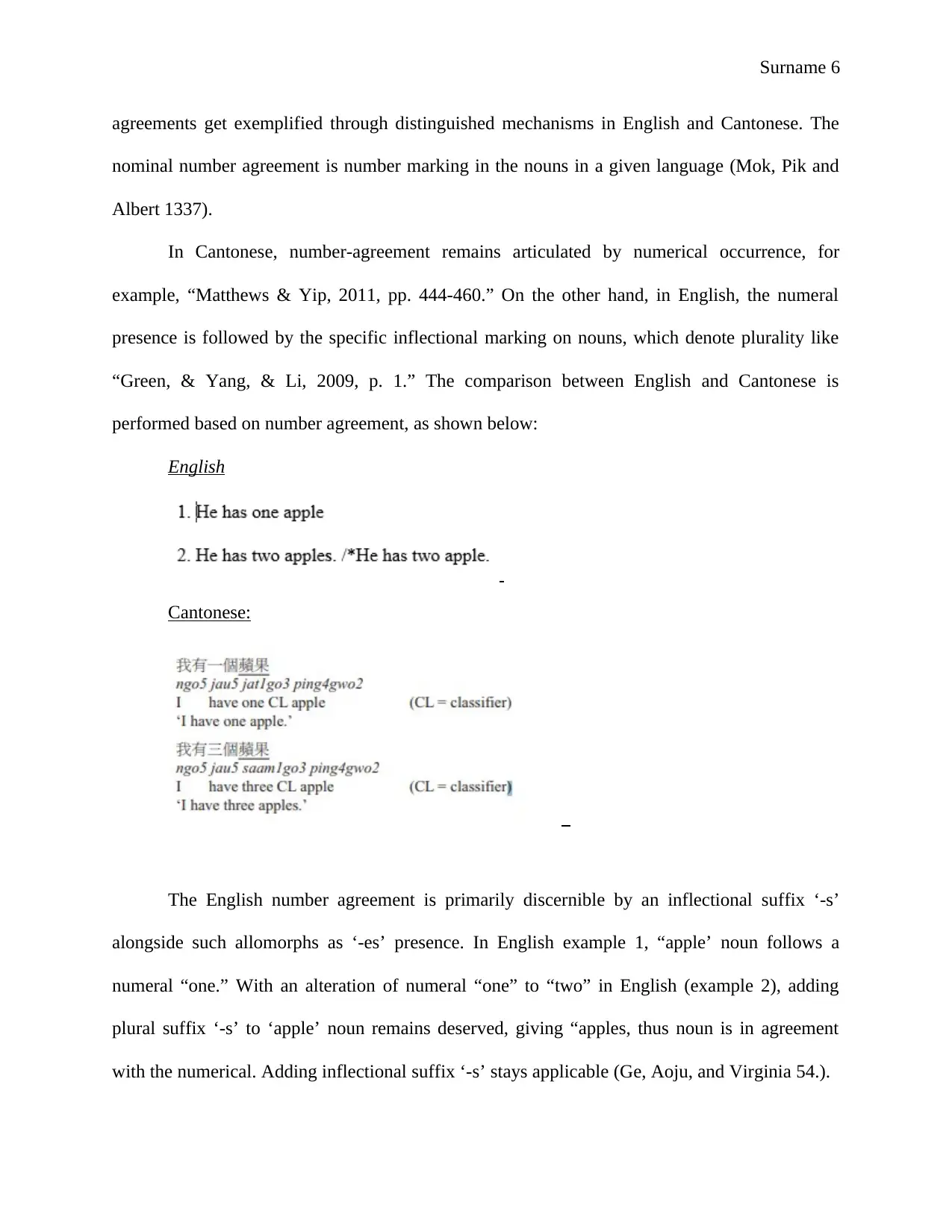

stance. Put differently, no Cantonese syllables are ending with a fricative. Table 1 below

illustrates certain fricatives examples in the word-initial stance.

Examples with fricative in word-initial position:

Comparison of Grammar

The word-formation in English and Cantonese is compared. English and Cantonese

straightforwardly compare in regards to wh-movement in the wh-interrogatives that stays

obligatory in English but not known in Cantonese. The wh-phrases are usually left in situ.

Language and Thought

This section compares whether the language spoken by English or Cantonese speakers

influences their thought. Cantonese and English deliberate about time in different manner-

English mainly talk regarding time as if it was horizontal, whereas Cantonese usually describes

time vertically. Such a difference between Cantonese and English remains manifested in a

manner their speakers think regarding time. Cantonese speakers tend to think regarding time in a

vertical way, even where they are considering for English (Miller 60).

The Cantonese speakers stood quicker to verify that March always precedes April when

they have merely observed a vertical objects range as opposed to when they have only viewed a

horizontal range, and the opposite hold for English speakers (Tsui and Chuck 40). The degree to

which Cantonese-English bilinguals vertically think regarding time is linked to their ages when

stance. Put differently, no Cantonese syllables are ending with a fricative. Table 1 below

illustrates certain fricatives examples in the word-initial stance.

Examples with fricative in word-initial position:

Comparison of Grammar

The word-formation in English and Cantonese is compared. English and Cantonese

straightforwardly compare in regards to wh-movement in the wh-interrogatives that stays

obligatory in English but not known in Cantonese. The wh-phrases are usually left in situ.

Language and Thought

This section compares whether the language spoken by English or Cantonese speakers

influences their thought. Cantonese and English deliberate about time in different manner-

English mainly talk regarding time as if it was horizontal, whereas Cantonese usually describes

time vertically. Such a difference between Cantonese and English remains manifested in a

manner their speakers think regarding time. Cantonese speakers tend to think regarding time in a

vertical way, even where they are considering for English (Miller 60).

The Cantonese speakers stood quicker to verify that March always precedes April when

they have merely observed a vertical objects range as opposed to when they have only viewed a

horizontal range, and the opposite hold for English speakers (Tsui and Chuck 40). The degree to

which Cantonese-English bilinguals vertically think regarding time is linked to their ages when

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Surname 4

they started learning English for the first time. Indigenous English speakers learn to talk

regarding time utilizing spatial phrases in a manner identical to Cantonese (Zhu and Peggy 752).

Native Cantonese and English think differently regarding time. This remains true despite

both groups being tested in English. The speakers of interest are quicker to confirm that March

precedes April following horizontal primes as opposed to after vertical primes. Such a habit of

horizontal thought about time is foretold by horizontal spatial metaphors’ preponderance utilized

to talk regarding time in English (Yip and Stephen 10).

The reverse holds for the Cantonese speakers. Cantonese speakers are quicker to confirm

that April proceeds March following vertical primes as compared to after horizontal primes.

Such a habit of thought regarding time is prophesied by vertical time metaphors’ preponderance

in Cantonese. In short, it seems that habits in language inspire speakers’ thought. Because

Cantonese speakers further showcased vertical bias even where they are thinking for English,

and thus it appears that language-inspired habits in thinking can operate irrespective of language

which a person is thinking for at present (Uchikoshi, Lu, and Siwei 390 ).

The experience with a given language shapes the manner a person thinks. The link

between language experience and thinking patterns have been examined. Learning novel

language, therefore, influences a person’s way of thinking. Testing Cantonese-English bilinguals

helps comprehend the relationship between language and thought. Cantonese. Where learning a

different language does alter the manner a person is thinking, then such a person who learns

English early on or even have more English experience need to showcase less of a “Cantonese”

bias to vertically think about time (Rezzonico et al. 537).

Such tests have shown that prejudice to think vertically regarding time stands more

enormous for Cantonese speakers who began to learn English at an advanced stage in their lives.

they started learning English for the first time. Indigenous English speakers learn to talk

regarding time utilizing spatial phrases in a manner identical to Cantonese (Zhu and Peggy 752).

Native Cantonese and English think differently regarding time. This remains true despite

both groups being tested in English. The speakers of interest are quicker to confirm that March

precedes April following horizontal primes as opposed to after vertical primes. Such a habit of

horizontal thought about time is foretold by horizontal spatial metaphors’ preponderance utilized

to talk regarding time in English (Yip and Stephen 10).

The reverse holds for the Cantonese speakers. Cantonese speakers are quicker to confirm

that April proceeds March following vertical primes as compared to after horizontal primes.

Such a habit of thought regarding time is prophesied by vertical time metaphors’ preponderance

in Cantonese. In short, it seems that habits in language inspire speakers’ thought. Because

Cantonese speakers further showcased vertical bias even where they are thinking for English,

and thus it appears that language-inspired habits in thinking can operate irrespective of language

which a person is thinking for at present (Uchikoshi, Lu, and Siwei 390 ).

The experience with a given language shapes the manner a person thinks. The link

between language experience and thinking patterns have been examined. Learning novel

language, therefore, influences a person’s way of thinking. Testing Cantonese-English bilinguals

helps comprehend the relationship between language and thought. Cantonese. Where learning a

different language does alter the manner a person is thinking, then such a person who learns

English early on or even have more English experience need to showcase less of a “Cantonese”

bias to vertically think about time (Rezzonico et al. 537).

Such tests have shown that prejudice to think vertically regarding time stands more

enormous for Cantonese speakers who began to learn English at an advanced stage in their lives.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 5

Vertical bias surprisingly seems independent when Cantonese are exposed to English. Cantonese

speakers who learn English later in their lives stand more probable to think regarding time

vertically. Thus, the propensity to think regarding time in a vertical way stands connected to the

duration of pure Cantonese experiencing before any English being learned, however, not to

English experience length (Rezzonico et al. 158).

Even though such results firmly suggest that language influences habitual thought,

concern still exists. The variation in time metaphors utilized in Cantonese and English is

precisely ever the individual variation between Cantonese and English speakers. Another factor

considered is writing direction since while English stays written horizontally towards the right,

Cantonese is conventionally written in terms of vertical columns running towards the left.

Besides writing direction, other cultural variation between native Cantonese and native English

speakers leading to differences in the way of thinking (Tsang 628).

Language remains a powerful technique or tool that shapes abstract thought. Whenever

sensory information stays scarce or inconclusive like the motion of time direction, language

could play a key role in shaping how speakers always think. Language-inspired mappings

between time and space get stored in the time domain. Therefore, if spatiotemporal metaphors

are the difference, many individuals have variation in terms of time. Language is thus powerful

in the determination of thought for more abstract domains, meaning, those that do not rely on

sensory (Ge et al. 237).

Acquisition

Amongst the several distinctions between Cantonese and English, nominal number

agreement remains a central distinction which has attracted much consideration amongst scholars

in the acquisition of the second language. This is narrowly linked to how such number

Vertical bias surprisingly seems independent when Cantonese are exposed to English. Cantonese

speakers who learn English later in their lives stand more probable to think regarding time

vertically. Thus, the propensity to think regarding time in a vertical way stands connected to the

duration of pure Cantonese experiencing before any English being learned, however, not to

English experience length (Rezzonico et al. 158).

Even though such results firmly suggest that language influences habitual thought,

concern still exists. The variation in time metaphors utilized in Cantonese and English is

precisely ever the individual variation between Cantonese and English speakers. Another factor

considered is writing direction since while English stays written horizontally towards the right,

Cantonese is conventionally written in terms of vertical columns running towards the left.

Besides writing direction, other cultural variation between native Cantonese and native English

speakers leading to differences in the way of thinking (Tsang 628).

Language remains a powerful technique or tool that shapes abstract thought. Whenever

sensory information stays scarce or inconclusive like the motion of time direction, language

could play a key role in shaping how speakers always think. Language-inspired mappings

between time and space get stored in the time domain. Therefore, if spatiotemporal metaphors

are the difference, many individuals have variation in terms of time. Language is thus powerful

in the determination of thought for more abstract domains, meaning, those that do not rely on

sensory (Ge et al. 237).

Acquisition

Amongst the several distinctions between Cantonese and English, nominal number

agreement remains a central distinction which has attracted much consideration amongst scholars

in the acquisition of the second language. This is narrowly linked to how such number

Surname 6

agreements get exemplified through distinguished mechanisms in English and Cantonese. The

nominal number agreement is number marking in the nouns in a given language (Mok, Pik and

Albert 1337).

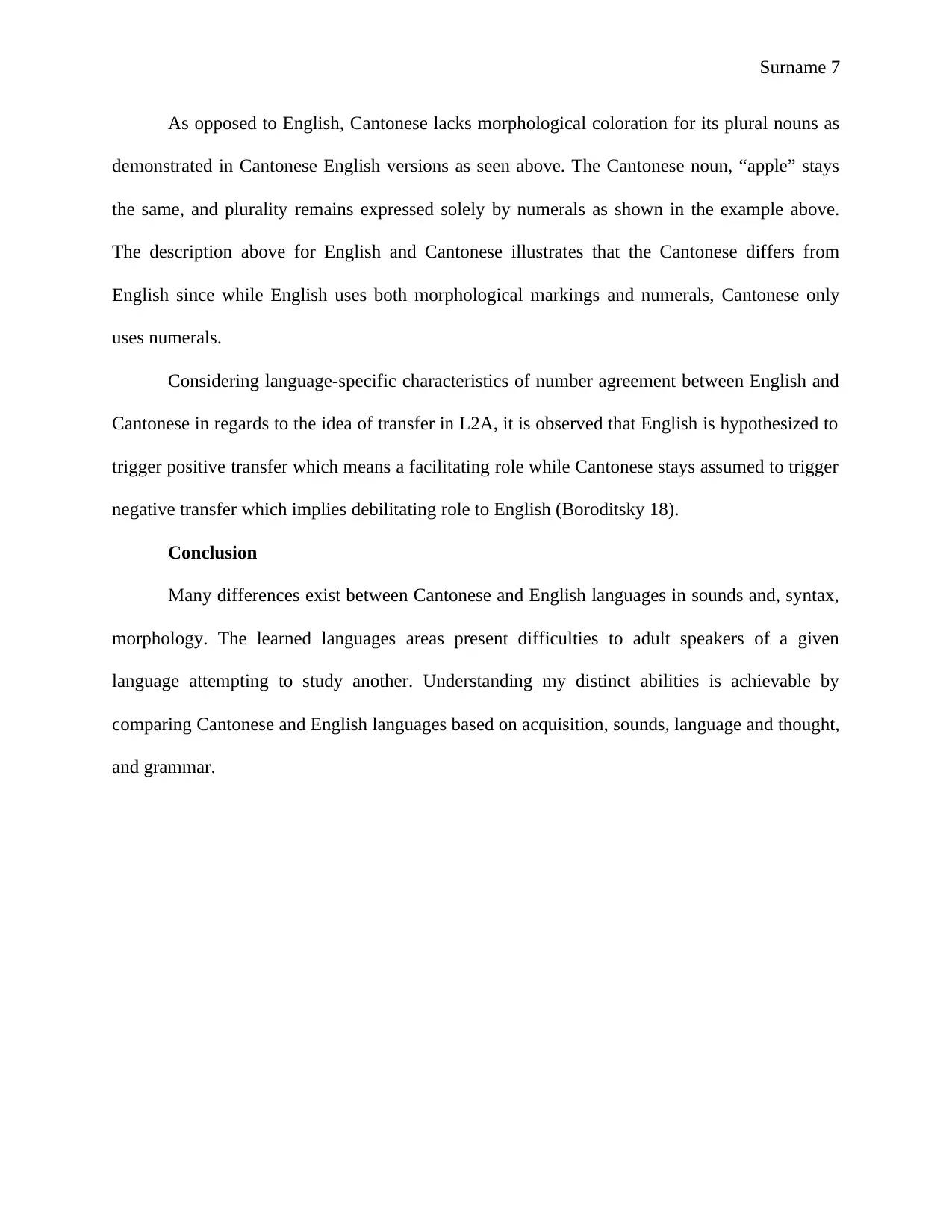

In Cantonese, number-agreement remains articulated by numerical occurrence, for

example, “Matthews & Yip, 2011, pp. 444-460.” On the other hand, in English, the numeral

presence is followed by the specific inflectional marking on nouns, which denote plurality like

“Green, & Yang, & Li, 2009, p. 1.” The comparison between English and Cantonese is

performed based on number agreement, as shown below:

English

Cantonese:

The English number agreement is primarily discernible by an inflectional suffix ‘-s’

alongside such allomorphs as ‘-es’ presence. In English example 1, “apple’ noun follows a

numeral “one.” With an alteration of numeral “one” to “two” in English (example 2), adding

plural suffix ‘-s’ to ‘apple’ noun remains deserved, giving “apples, thus noun is in agreement

with the numerical. Adding inflectional suffix ‘-s’ stays applicable (Ge, Aoju, and Virginia 54.).

agreements get exemplified through distinguished mechanisms in English and Cantonese. The

nominal number agreement is number marking in the nouns in a given language (Mok, Pik and

Albert 1337).

In Cantonese, number-agreement remains articulated by numerical occurrence, for

example, “Matthews & Yip, 2011, pp. 444-460.” On the other hand, in English, the numeral

presence is followed by the specific inflectional marking on nouns, which denote plurality like

“Green, & Yang, & Li, 2009, p. 1.” The comparison between English and Cantonese is

performed based on number agreement, as shown below:

English

Cantonese:

The English number agreement is primarily discernible by an inflectional suffix ‘-s’

alongside such allomorphs as ‘-es’ presence. In English example 1, “apple’ noun follows a

numeral “one.” With an alteration of numeral “one” to “two” in English (example 2), adding

plural suffix ‘-s’ to ‘apple’ noun remains deserved, giving “apples, thus noun is in agreement

with the numerical. Adding inflectional suffix ‘-s’ stays applicable (Ge, Aoju, and Virginia 54.).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Surname 7

As opposed to English, Cantonese lacks morphological coloration for its plural nouns as

demonstrated in Cantonese English versions as seen above. The Cantonese noun, “apple” stays

the same, and plurality remains expressed solely by numerals as shown in the example above.

The description above for English and Cantonese illustrates that the Cantonese differs from

English since while English uses both morphological markings and numerals, Cantonese only

uses numerals.

Considering language-specific characteristics of number agreement between English and

Cantonese in regards to the idea of transfer in L2A, it is observed that English is hypothesized to

trigger positive transfer which means a facilitating role while Cantonese stays assumed to trigger

negative transfer which implies debilitating role to English (Boroditsky 18).

Conclusion

Many differences exist between Cantonese and English languages in sounds and, syntax,

morphology. The learned languages areas present difficulties to adult speakers of a given

language attempting to study another. Understanding my distinct abilities is achievable by

comparing Cantonese and English languages based on acquisition, sounds, language and thought,

and grammar.

As opposed to English, Cantonese lacks morphological coloration for its plural nouns as

demonstrated in Cantonese English versions as seen above. The Cantonese noun, “apple” stays

the same, and plurality remains expressed solely by numerals as shown in the example above.

The description above for English and Cantonese illustrates that the Cantonese differs from

English since while English uses both morphological markings and numerals, Cantonese only

uses numerals.

Considering language-specific characteristics of number agreement between English and

Cantonese in regards to the idea of transfer in L2A, it is observed that English is hypothesized to

trigger positive transfer which means a facilitating role while Cantonese stays assumed to trigger

negative transfer which implies debilitating role to English (Boroditsky 18).

Conclusion

Many differences exist between Cantonese and English languages in sounds and, syntax,

morphology. The learned languages areas present difficulties to adult speakers of a given

language attempting to study another. Understanding my distinct abilities is achievable by

comparing Cantonese and English languages based on acquisition, sounds, language and thought,

and grammar.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 8

Works Cited

Boroditsky, Lera. "Does language shape thought?: Mandarin and English speakers' conceptions

of time." Cognitive psychology 43.1 (2013): 1-22.

Chan, Alice YW, and David CS Li. "English and Cantonese phonology in contrast: Explaining

Cantonese ESL learners' English pronunciation problems." Language Culture and

Curriculum 13.1 (2000): 67-85.

Ge, Haoyan, Aoju Chen, and Virginia Yip. "L1 Effects on L2 comprehension of focus-to-

prosody mapping: A comparison between Cantonese and Dutch learners of

English." Proc. 9th International Conference on Speech Prosody 2018. 2018.

Ge, Haoyan, et al. "Bidirectional cross-linguistic influence in Cantonese–English bilingual

children: the case of right-dislocation." First Language 37.3 (2017): 231-251.

Miller, Annaliese. "Language input in Cantonese-English bilingual preschoolers with language

impairment." (2017).

Mok, Peggy Pik Ki, and L. E. E. Albert. "The acquisition of lexical tones by Cantonese–English

bilingual children." Journal of child language 45.6 (2018): 1357-1376.

Rezzonico, Stefano, et al. "English Verb Accuracy of Bilingual Cantonese–English

Preschoolers." Language, speech, and hearing services in schools 48.3 (2017): 153-167.

Rezzonico, Stefano, et al. "Narratives in two languages: Storytelling of bilingual cantonese–

english preschoolers." Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 59.3 (2016):

521-532.

Tsang, Wai Lan. "Acquisition of English number agreement: L1 Cantonese–L2 English–L3

French speakers versus L1 Cantonese–L2 English speakers." International Journal of

Bilingualism 20.5 (2016): 611-635.

Works Cited

Boroditsky, Lera. "Does language shape thought?: Mandarin and English speakers' conceptions

of time." Cognitive psychology 43.1 (2013): 1-22.

Chan, Alice YW, and David CS Li. "English and Cantonese phonology in contrast: Explaining

Cantonese ESL learners' English pronunciation problems." Language Culture and

Curriculum 13.1 (2000): 67-85.

Ge, Haoyan, Aoju Chen, and Virginia Yip. "L1 Effects on L2 comprehension of focus-to-

prosody mapping: A comparison between Cantonese and Dutch learners of

English." Proc. 9th International Conference on Speech Prosody 2018. 2018.

Ge, Haoyan, et al. "Bidirectional cross-linguistic influence in Cantonese–English bilingual

children: the case of right-dislocation." First Language 37.3 (2017): 231-251.

Miller, Annaliese. "Language input in Cantonese-English bilingual preschoolers with language

impairment." (2017).

Mok, Peggy Pik Ki, and L. E. E. Albert. "The acquisition of lexical tones by Cantonese–English

bilingual children." Journal of child language 45.6 (2018): 1357-1376.

Rezzonico, Stefano, et al. "English Verb Accuracy of Bilingual Cantonese–English

Preschoolers." Language, speech, and hearing services in schools 48.3 (2017): 153-167.

Rezzonico, Stefano, et al. "Narratives in two languages: Storytelling of bilingual cantonese–

english preschoolers." Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 59.3 (2016):

521-532.

Tsang, Wai Lan. "Acquisition of English number agreement: L1 Cantonese–L2 English–L3

French speakers versus L1 Cantonese–L2 English speakers." International Journal of

Bilingualism 20.5 (2016): 611-635.

Surname 9

Tsui, Rachel Ka-Ying, Xiuli Tong, and Chuck Siu Ki Chan. "Impact of language dominance on

phonetic transfer in Cantonese–English bilingual language switching." Applied

Psycholinguistics 40.1 (2019): 29-58.

Uchikoshi, Yuuko, Lu Yang, and Siwei Liu. "Role of narrative skills on reading comprehension:

Spanish–English and Cantonese–English dual language learners." Reading and

writing 31.2 (2018): 381-404.

Yip, Virginia, and Stephen Matthews. "Parental Language Strategy and the Child's Code-Mixing

of English and Cantonese." Chinese Journal of Language Policy and Planning 6 (2017):

10.

Zhu, Yanjiao, and Peggy Pik Ki Mok. "Intonational Phrasing in a Third Language–The

Production of German by Cantonese-English Bilingual Learners." Speech Prosody

2016 (2016): 751-755.

Tsui, Rachel Ka-Ying, Xiuli Tong, and Chuck Siu Ki Chan. "Impact of language dominance on

phonetic transfer in Cantonese–English bilingual language switching." Applied

Psycholinguistics 40.1 (2019): 29-58.

Uchikoshi, Yuuko, Lu Yang, and Siwei Liu. "Role of narrative skills on reading comprehension:

Spanish–English and Cantonese–English dual language learners." Reading and

writing 31.2 (2018): 381-404.

Yip, Virginia, and Stephen Matthews. "Parental Language Strategy and the Child's Code-Mixing

of English and Cantonese." Chinese Journal of Language Policy and Planning 6 (2017):

10.

Zhu, Yanjiao, and Peggy Pik Ki Mok. "Intonational Phrasing in a Third Language–The

Production of German by Cantonese-English Bilingual Learners." Speech Prosody

2016 (2016): 751-755.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.