Analysis of Capital Budgeting Techniques in Southern Italian Firms

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/12

|15

|6971

|3

Report

AI Summary

This report examines capital budgeting practices in Southern Italy, based on a survey of 71 firms. It reviews the importance of capital budgeting in financial management and explores techniques like Payback Period (PP), Net Present Value (NPV), and Internal Rate of Return (IRR). The study found that PP, followed by NPV, is the most used method, with more complex methods favored by larger enterprises. The research highlights the weakness in defining the cost of capital, as approximately 70% of firms use non-quantitative techniques for risk assessment. The study provides insights into common pitfalls in capital budgeting, offering valuable knowledge for those evaluating investment projects and developing capital budgeting policies. The research methodology included a survey of CFOs, and the findings are analyzed using descriptive approaches and chi-square tests. The report also discusses the influence of firm size and industry sector on capital budgeting choices, offering a foundation for further research in the field.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277655349

The use of capital budgeting techniques: An outlook from Italy

Article in International Journal of Management Practice · January 2015

DOI: 10.1504/IJMP.2015.068302

CITATIONS

10

READS

5,147

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Venture CapitalView project

Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and ManagementView project

Matteo Rossi

Università degli Studi del Sannio

52PUBLICATIONS496CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Matteo Rossi on 04 January 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The use of capital budgeting techniques: An outlook from Italy

Article in International Journal of Management Practice · January 2015

DOI: 10.1504/IJMP.2015.068302

CITATIONS

10

READS

5,147

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Venture CapitalView project

Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and ManagementView project

Matteo Rossi

Università degli Studi del Sannio

52PUBLICATIONS496CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Matteo Rossi on 04 January 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Int. J. Management Practice, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2015 43

Copyright © 2015 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.

The use of capital budgeting techniques: an outlook

from Italy

Matteo Rossi

DEMM Department,

University of Sannio,

Via delle Puglie, 82, 82100 Benevento, Italy

Email: mrossi@unisannio.it

Abstract: Capital budgeting is one of the most important areas of financial

management. Different techniques are used to evaluate capital budgeting

projects: the Payback Period (PP), the Net Present Value (NPV) and the

Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Graham and Harvey (2002) highlight that

financial managers favour methods such as the IRR or non-discounted Payback

Period (PP). The results of this research revealed that PP, followed by NPV, is

the most used method. The more complex methods are most favoured by the

large enterprises. The principal weakness of the evaluation process is the

definition of cost of capital: approximately 70% of the enterprises considered

use non-quantitative techniques to consider risk. This study provides those

evaluating investment projects or conceiving capital budgeting manuals or

policies with knowledge about common pitfalls that, if acted upon, could

improve decision making. This study is exploratory research and the results

represent a basis for further research.

Keywords: capital budgeting; NPV; net present value; IRR; internal rate of

return; payback period; WACC.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Rossi, M. (2015) ‘The use

of capital budgeting techniques: an outlook from Italy’, Int. J. Management

Practice, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.43–56.

Biographical notes: Matteo Rossi is an Assistant Professor of Corporate

Finance at the University of Sannio, Italy. He holds a PhD in Corporate

Governance, and his prime research interests are corporate finance, financing

innovation and finance for SMEs. He is Vice President of the EuroMed

Research Business Institute. He is an Associate Editor of Global Business and

Economics, International Journal of Bond and Derivatives and International

Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting. In 2014, he won the highly

commended paper award of the International Journal of Organizational

Analysis (Emerald) for the paper ‘Mergers and acquisitions in the high-tech

industry: a literature review’.

1 Introduction

Capital budgeting plays a fundamental role in any firm’s financial management strategy.

Capital budgeting is the “process of evaluating and selecting long term investments that

are consistent with the business’s goal of maximising owner wealth” (Gitman, 2007,

p.380).

Copyright © 2015 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.

The use of capital budgeting techniques: an outlook

from Italy

Matteo Rossi

DEMM Department,

University of Sannio,

Via delle Puglie, 82, 82100 Benevento, Italy

Email: mrossi@unisannio.it

Abstract: Capital budgeting is one of the most important areas of financial

management. Different techniques are used to evaluate capital budgeting

projects: the Payback Period (PP), the Net Present Value (NPV) and the

Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Graham and Harvey (2002) highlight that

financial managers favour methods such as the IRR or non-discounted Payback

Period (PP). The results of this research revealed that PP, followed by NPV, is

the most used method. The more complex methods are most favoured by the

large enterprises. The principal weakness of the evaluation process is the

definition of cost of capital: approximately 70% of the enterprises considered

use non-quantitative techniques to consider risk. This study provides those

evaluating investment projects or conceiving capital budgeting manuals or

policies with knowledge about common pitfalls that, if acted upon, could

improve decision making. This study is exploratory research and the results

represent a basis for further research.

Keywords: capital budgeting; NPV; net present value; IRR; internal rate of

return; payback period; WACC.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Rossi, M. (2015) ‘The use

of capital budgeting techniques: an outlook from Italy’, Int. J. Management

Practice, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.43–56.

Biographical notes: Matteo Rossi is an Assistant Professor of Corporate

Finance at the University of Sannio, Italy. He holds a PhD in Corporate

Governance, and his prime research interests are corporate finance, financing

innovation and finance for SMEs. He is Vice President of the EuroMed

Research Business Institute. He is an Associate Editor of Global Business and

Economics, International Journal of Bond and Derivatives and International

Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting. In 2014, he won the highly

commended paper award of the International Journal of Organizational

Analysis (Emerald) for the paper ‘Mergers and acquisitions in the high-tech

industry: a literature review’.

1 Introduction

Capital budgeting plays a fundamental role in any firm’s financial management strategy.

Capital budgeting is the “process of evaluating and selecting long term investments that

are consistent with the business’s goal of maximising owner wealth” (Gitman, 2007,

p.380).

44 M. Rossi

These decisions require that a firm define all of the necessary steps to ensure that its

decision-making criteria support the business’s strategy: “the realisation that a business

leverages its competitive advantage on its resources and on how it undertakes decisions

relating to the use of its resources, such as financial resources call for managers to make

informed decisions” (Brijlal and Llorente Quesada, 2008). Today, it is necessary – in a

highly competitive environment – to make each decision after acquiring information.

This paper is based on a survey of managers of firms in Southern Italy on how they

undertook capital budgeting practices. The research follows similar surveys conducted

around the globe (such as Kester et al., 1999; Kester and Chong, 2001; Sandahl and

Sjogren, 2002; Brijlal and Llorente Quesada, 2008; Bennouna et al., 2010; Hartwig,

2012).

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review on capital

budgeting techniques. Section 3 presents the research methodology and objectives and

Section 4 presents the main results of our research. Section 5 presents some managerial

implications, and the final Section 6 draws conclusions from the research findings and

investigates future directions.

2 Literature review

Many scholars (Arya et al., 1998; Swain and Haka, 2000; Brijlal and Llorente Quesada,

2008) maintain that capital budgeting decisions are crucial to a business’s performance.

In fact, capital budgeting plays a vital role in a business’s competitive model. Kwak et al.

(1996) thus states that capital budgeting is not a banal decision. A business, whose ability

to effectively develop a possible mechanism for capital budgeting, may realise a better

competitive advantage over its rivals in an environment that is characterised by change

and volatility (Lazaridis, 2004).

Many studies have been conducted worldwide that provide interesting results on

capital budgeting practices (Jog and Srivastava, 1995; Pike, 1996; Drury and Tayles,

1996; Block, 1997; Kester et al., 1999; Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl and Sjogren,

2002; Brounen et al., 2004; Lazaridis, 2004; Hermes et al., 2007; Truong et al., 2008;

Bennouna et al., 2010; Andor et al., 2012). The major international research is

concentrated on capital budgeting practices in large firms. Only some research has

considered small and medium enterprises. Managers use different techniques to facilitate

capital budgeting procedures. In practice, capital budgeting differs from industry-to-

industry and firm-to-firm, but in managerial decision making, that theory seems to be

ignored in practice.

Important studies on capital budgeting were conducted by Drury and Tayles (1996),

Maccarrone (1996), Kester et al. (1999), Sandahl and Sjogren (2002), Lazaridis (2004),

Hermes et al. (2007) and Danielson and Scott (2006). These studies focus on different

countries such as Italy, Cyprus, the Netherlands, China, Singapore and other Asiatic

countries, Sweden, Canada, the USA, and UK. These surveys have shown that the

sophistication of the analytical techniques used by executives has increased over time.

Particularly, Kester et al. (1999) affirm that Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) techniques –

such as Net Present Value (NPV) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – have become the

dominant methods of evaluating capital investment.

These decisions require that a firm define all of the necessary steps to ensure that its

decision-making criteria support the business’s strategy: “the realisation that a business

leverages its competitive advantage on its resources and on how it undertakes decisions

relating to the use of its resources, such as financial resources call for managers to make

informed decisions” (Brijlal and Llorente Quesada, 2008). Today, it is necessary – in a

highly competitive environment – to make each decision after acquiring information.

This paper is based on a survey of managers of firms in Southern Italy on how they

undertook capital budgeting practices. The research follows similar surveys conducted

around the globe (such as Kester et al., 1999; Kester and Chong, 2001; Sandahl and

Sjogren, 2002; Brijlal and Llorente Quesada, 2008; Bennouna et al., 2010; Hartwig,

2012).

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review on capital

budgeting techniques. Section 3 presents the research methodology and objectives and

Section 4 presents the main results of our research. Section 5 presents some managerial

implications, and the final Section 6 draws conclusions from the research findings and

investigates future directions.

2 Literature review

Many scholars (Arya et al., 1998; Swain and Haka, 2000; Brijlal and Llorente Quesada,

2008) maintain that capital budgeting decisions are crucial to a business’s performance.

In fact, capital budgeting plays a vital role in a business’s competitive model. Kwak et al.

(1996) thus states that capital budgeting is not a banal decision. A business, whose ability

to effectively develop a possible mechanism for capital budgeting, may realise a better

competitive advantage over its rivals in an environment that is characterised by change

and volatility (Lazaridis, 2004).

Many studies have been conducted worldwide that provide interesting results on

capital budgeting practices (Jog and Srivastava, 1995; Pike, 1996; Drury and Tayles,

1996; Block, 1997; Kester et al., 1999; Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl and Sjogren,

2002; Brounen et al., 2004; Lazaridis, 2004; Hermes et al., 2007; Truong et al., 2008;

Bennouna et al., 2010; Andor et al., 2012). The major international research is

concentrated on capital budgeting practices in large firms. Only some research has

considered small and medium enterprises. Managers use different techniques to facilitate

capital budgeting procedures. In practice, capital budgeting differs from industry-to-

industry and firm-to-firm, but in managerial decision making, that theory seems to be

ignored in practice.

Important studies on capital budgeting were conducted by Drury and Tayles (1996),

Maccarrone (1996), Kester et al. (1999), Sandahl and Sjogren (2002), Lazaridis (2004),

Hermes et al. (2007) and Danielson and Scott (2006). These studies focus on different

countries such as Italy, Cyprus, the Netherlands, China, Singapore and other Asiatic

countries, Sweden, Canada, the USA, and UK. These surveys have shown that the

sophistication of the analytical techniques used by executives has increased over time.

Particularly, Kester et al. (1999) affirm that Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) techniques –

such as Net Present Value (NPV) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – have become the

dominant methods of evaluating capital investment.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The use of capital budgeting techniques 45

Concerning the result of capital budgeting decisions on a firm’s performance, an

important contribution comes from the study of Hatfield et al. (1998). They investigate

the importance of PP, ARR, IRR, and NPV capital budgeting techniques on the

performance and value measures of firms. Hatfield et al. (1998) stress that enterprises

analysed each project had a higher share price on average compared with those that did

not. A second result of Hatfield et al.’s study is that the NPV technique did not maximise

the value of the business. This conclusion contrasts with the theory of finance. In

conclusion, their results suggest that firms should not use only one capital budgeting

technique but should apply at least two or three methods when evaluating a project.

In interesting research, Block (1997) focuses on the capital budgeting techniques

used by small companies. The results, based on a sample of 232 small businesses, reveal

that the payback method is still the preferred approach in 42.7% of the firms. Unlike

many larger firms, these firms’ time horizon is often the period over which a financial

institution will extend them funding.

Graham and Harvey (2001, 2002) survey 392 CFOs about the cost of capital, capital

budgeting and capital structure. The results disclose that “large firms rely heavily on

present value techniques and the capital asset pricing model, while small firms are

relatively likely to use the payback criterion” (Graham and Harvey, 2001, p.187). The

authors find that IRR and NPV were the most frequently used capital budgeting

techniques. Other techniques such as the payback period were less popular but were still

used by many companies.

Brounen et al. (2004) conduct a survey of 313 CFOs across four European countries

(the UK, the Netherlands, Germany and France) on capital budgeting, cost of capital,

capital structure and corporate governance. Their results indicate that “[w]hile large firms

frequently use present value techniques and the capital asset pricing model when

assessing the financial feasibility of an investment opportunity, CFOs of small firms still

rely on the payback criterion” (Brounen et al., 2004, p.71).

More recently, Truong et al. (2008) perform an important study on capital budgeting

in Australia. They use a sample survey to analyse the capital-budgeting practices of 356

Australian-listed companies and find that NPV, IRR and payback are the most popular

evaluation techniques.

Bennouna et al. (2010) focus on the capital budgeting decision making of Canadian

firms, including 88 large firms. The results show that the trends towards sophisticated

techniques have continued; however, even in large firms, 17% did not use DCF. Of those

that did use DCF, the majority favoured NPV and IRR.

Hartwig (2012) conducts a similar study, analysing the use f capital budgeting and

cost of capital estimation methods in Swedish-listed companies to study the relationship

between company characteristics and their choice of methods, making both within-

country longitudinal and cross-country comparisons. The results reveal that larger

companies seem to use capital budgeting methods more frequently than smaller

companies. Compared with the US and continental European companies, Swedish-listed

companies employed capital budgeting methods less frequently.

Andor et al. (2012) perform another important study on capital budgeting techniques

in European countries. They conduct a survey of 400 executives in ten countries of

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) – Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia,

Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic and Slovenia. They find that the capital

Concerning the result of capital budgeting decisions on a firm’s performance, an

important contribution comes from the study of Hatfield et al. (1998). They investigate

the importance of PP, ARR, IRR, and NPV capital budgeting techniques on the

performance and value measures of firms. Hatfield et al. (1998) stress that enterprises

analysed each project had a higher share price on average compared with those that did

not. A second result of Hatfield et al.’s study is that the NPV technique did not maximise

the value of the business. This conclusion contrasts with the theory of finance. In

conclusion, their results suggest that firms should not use only one capital budgeting

technique but should apply at least two or three methods when evaluating a project.

In interesting research, Block (1997) focuses on the capital budgeting techniques

used by small companies. The results, based on a sample of 232 small businesses, reveal

that the payback method is still the preferred approach in 42.7% of the firms. Unlike

many larger firms, these firms’ time horizon is often the period over which a financial

institution will extend them funding.

Graham and Harvey (2001, 2002) survey 392 CFOs about the cost of capital, capital

budgeting and capital structure. The results disclose that “large firms rely heavily on

present value techniques and the capital asset pricing model, while small firms are

relatively likely to use the payback criterion” (Graham and Harvey, 2001, p.187). The

authors find that IRR and NPV were the most frequently used capital budgeting

techniques. Other techniques such as the payback period were less popular but were still

used by many companies.

Brounen et al. (2004) conduct a survey of 313 CFOs across four European countries

(the UK, the Netherlands, Germany and France) on capital budgeting, cost of capital,

capital structure and corporate governance. Their results indicate that “[w]hile large firms

frequently use present value techniques and the capital asset pricing model when

assessing the financial feasibility of an investment opportunity, CFOs of small firms still

rely on the payback criterion” (Brounen et al., 2004, p.71).

More recently, Truong et al. (2008) perform an important study on capital budgeting

in Australia. They use a sample survey to analyse the capital-budgeting practices of 356

Australian-listed companies and find that NPV, IRR and payback are the most popular

evaluation techniques.

Bennouna et al. (2010) focus on the capital budgeting decision making of Canadian

firms, including 88 large firms. The results show that the trends towards sophisticated

techniques have continued; however, even in large firms, 17% did not use DCF. Of those

that did use DCF, the majority favoured NPV and IRR.

Hartwig (2012) conducts a similar study, analysing the use f capital budgeting and

cost of capital estimation methods in Swedish-listed companies to study the relationship

between company characteristics and their choice of methods, making both within-

country longitudinal and cross-country comparisons. The results reveal that larger

companies seem to use capital budgeting methods more frequently than smaller

companies. Compared with the US and continental European companies, Swedish-listed

companies employed capital budgeting methods less frequently.

Andor et al. (2012) perform another important study on capital budgeting techniques

in European countries. They conduct a survey of 400 executives in ten countries of

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) – Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia,

Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic and Slovenia. They find that the capital

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

46 M. Rossi

budgeting practices in CEE countries are influenced most by firm size, multinational

culture, a firm’s goals, code of ethics; and to a lesser extent, executive ownership,

number of projects analysed, and target leverage.

This research presents a description of capital budgeting practices in the Southern

Italy. The principal motivation of this study is the small amount of empirical research on

capital budgeting practices compared with other regions of other countries such as the

USA, UK, Canada, China and Singapore. Through this research, additional empirical

evidence relating to capital budgeting practices in Southern Italy was sought. A number

of variables and associations relating to capital budgeting practices in business firms in

the South of Italy were investigated.

3 Research methods

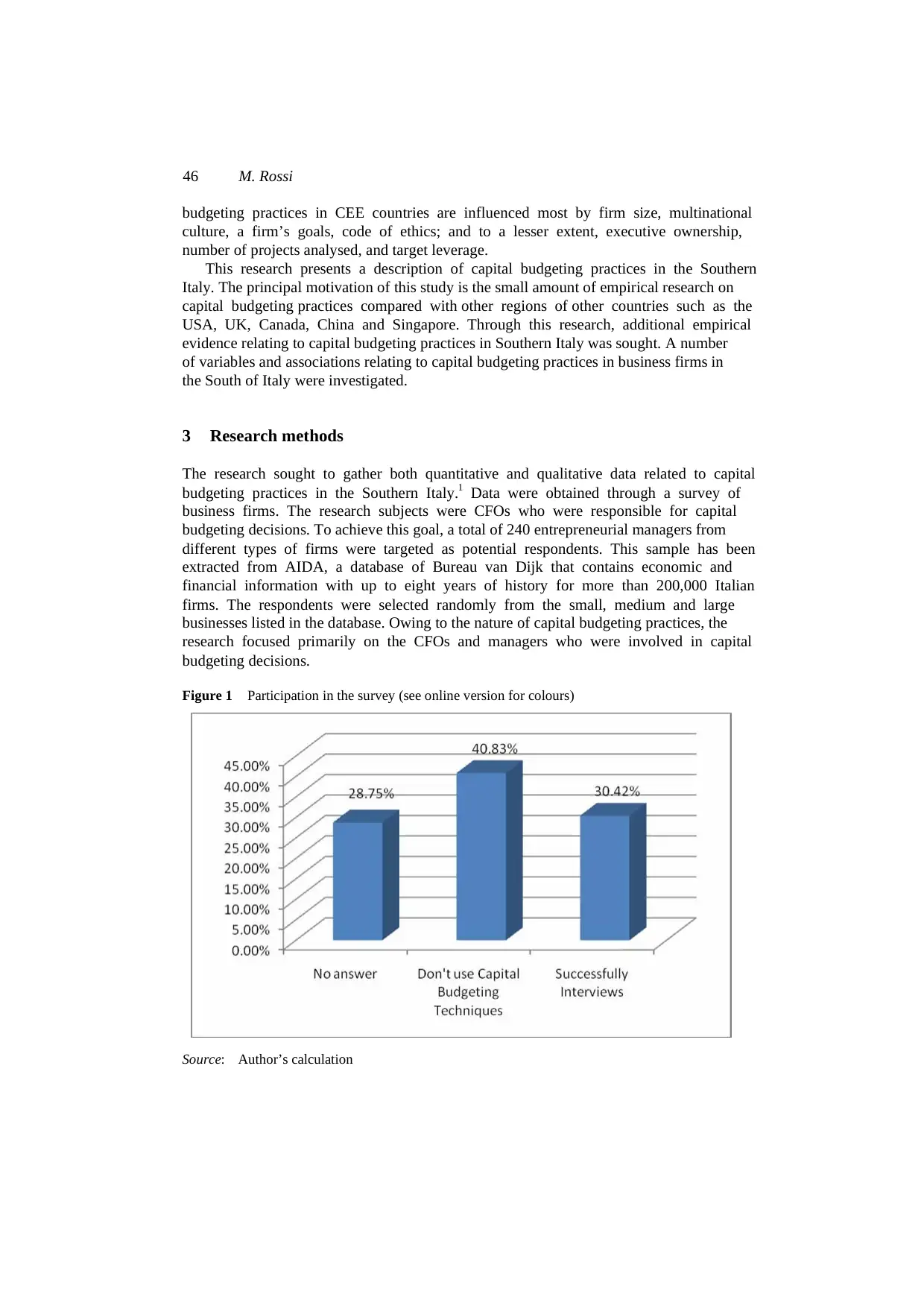

The research sought to gather both quantitative and qualitative data related to capital

budgeting practices in the Southern Italy.1 Data were obtained through a survey of

business firms. The research subjects were CFOs who were responsible for capital

budgeting decisions. To achieve this goal, a total of 240 entrepreneurial managers from

different types of firms were targeted as potential respondents. This sample has been

extracted from AIDA, a database of Bureau van Dijk that contains economic and

financial information with up to eight years of history for more than 200,000 Italian

firms. The respondents were selected randomly from the small, medium and large

businesses listed in the database. Owing to the nature of capital budgeting practices, the

research focused primarily on the CFOs and managers who were involved in capital

budgeting decisions.

Figure 1 Participation in the survey (see online version for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

budgeting practices in CEE countries are influenced most by firm size, multinational

culture, a firm’s goals, code of ethics; and to a lesser extent, executive ownership,

number of projects analysed, and target leverage.

This research presents a description of capital budgeting practices in the Southern

Italy. The principal motivation of this study is the small amount of empirical research on

capital budgeting practices compared with other regions of other countries such as the

USA, UK, Canada, China and Singapore. Through this research, additional empirical

evidence relating to capital budgeting practices in Southern Italy was sought. A number

of variables and associations relating to capital budgeting practices in business firms in

the South of Italy were investigated.

3 Research methods

The research sought to gather both quantitative and qualitative data related to capital

budgeting practices in the Southern Italy.1 Data were obtained through a survey of

business firms. The research subjects were CFOs who were responsible for capital

budgeting decisions. To achieve this goal, a total of 240 entrepreneurial managers from

different types of firms were targeted as potential respondents. This sample has been

extracted from AIDA, a database of Bureau van Dijk that contains economic and

financial information with up to eight years of history for more than 200,000 Italian

firms. The respondents were selected randomly from the small, medium and large

businesses listed in the database. Owing to the nature of capital budgeting practices, the

research focused primarily on the CFOs and managers who were involved in capital

budgeting decisions.

Figure 1 Participation in the survey (see online version for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

The use of capital budgeting techniques 47

A pilot test of the survey interview schedule was first administered to eight managers

(one for each region of Southern Italy). The purpose of pilot testing was to check the

relevance of the questions before interviewing. A descriptive approach to the research

finding was adopted. This was augmented by the chi square test, which was used to

measure the association between variables. Quantitative analysis of the data obtained was

carried out using the SPSS software. The qualitative issues raised during the research are

incorporated to explain the associations and other relationships that were suggested by

the research findings. Of the 240 targeted interviews, 71 interviews were successfully

conducted, giving a response rate of approximately 30%. The first important result is that

98 firms declared that they do not use capital budgeting techniques (Figure 1).

4 Main results

The following section discusses the main findings and results of the survey on the capital

budgeting techniques used by Southern Italian firms.

The first classification considers the business size and sector of the firms involved.

From a total of 71 respondents, 11.26% qualified as large firms, while 40.85% were

medium enterprises, and the remaining 47.89% were categorised as small businesses.

The respondents were further categorised according to industry. Of the firms in the

survey, 52.11% represented the service sector, 29.58% were in retail, and the remaining

18.31% were involved in manufacturing activities.

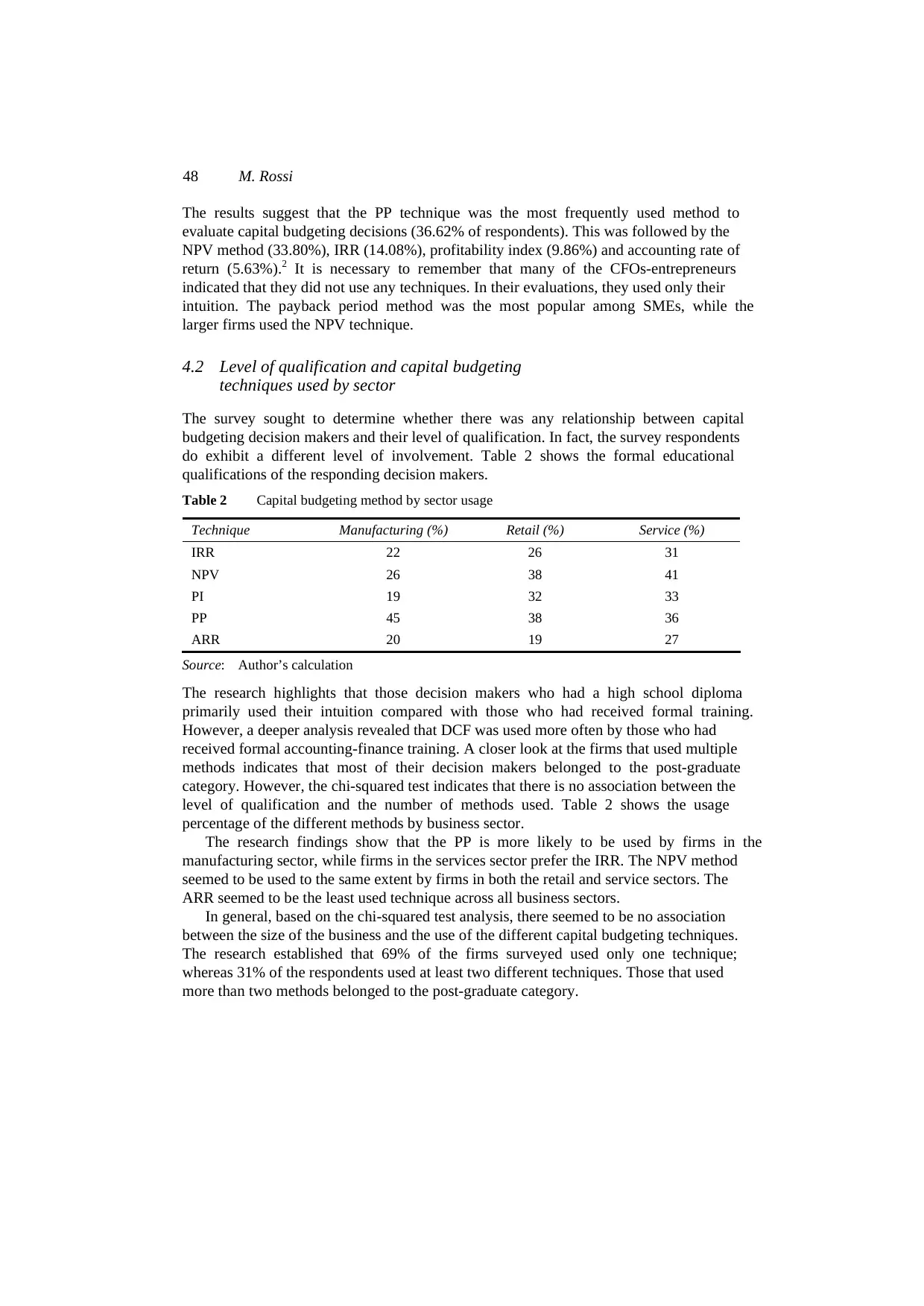

4.1 Capital budgeting techniques employed

In the literature, scholars distinguish between two DCF techniques: traditional and

modern. Managers can use either of these techniques or a combination of both. Capital

budgeting theory favours the use of DCF techniques based on the time value of money.

As Brealey et al. (2011) explain, managers make capital budgeting decisions based on the

assumption that the primary goal of the business is to maximise the shareholders’ wealth.

If this consideration is true, firms will invest in projects that will yield a positive NPV.

Some important research supports this point of view. Kester et al. (1999), Graham and

Harvey (2001) and others explain why DCF techniques have become a dominant

technique for evaluating capital budgeting decisions, particularly in large and more

structured enterprises. However, in their research, Graham and Harvey (2001) conclude

that due to limited managerial skills (particularly in SMEs), less complicated techniques

such as the payback method continue to dominate capital budgeting decision making. In

this study, the survey covered the use of all different techniques, including both capital

budgeting discounted and non-discounted capital budgeting methods. Table 1 shows the

results.

Table 1 Capital budgeting techniques used by firms

Method IRR NPV PI PP ARR

Number of firm 10 24 7 26 4

Source: Author’s calculation

A pilot test of the survey interview schedule was first administered to eight managers

(one for each region of Southern Italy). The purpose of pilot testing was to check the

relevance of the questions before interviewing. A descriptive approach to the research

finding was adopted. This was augmented by the chi square test, which was used to

measure the association between variables. Quantitative analysis of the data obtained was

carried out using the SPSS software. The qualitative issues raised during the research are

incorporated to explain the associations and other relationships that were suggested by

the research findings. Of the 240 targeted interviews, 71 interviews were successfully

conducted, giving a response rate of approximately 30%. The first important result is that

98 firms declared that they do not use capital budgeting techniques (Figure 1).

4 Main results

The following section discusses the main findings and results of the survey on the capital

budgeting techniques used by Southern Italian firms.

The first classification considers the business size and sector of the firms involved.

From a total of 71 respondents, 11.26% qualified as large firms, while 40.85% were

medium enterprises, and the remaining 47.89% were categorised as small businesses.

The respondents were further categorised according to industry. Of the firms in the

survey, 52.11% represented the service sector, 29.58% were in retail, and the remaining

18.31% were involved in manufacturing activities.

4.1 Capital budgeting techniques employed

In the literature, scholars distinguish between two DCF techniques: traditional and

modern. Managers can use either of these techniques or a combination of both. Capital

budgeting theory favours the use of DCF techniques based on the time value of money.

As Brealey et al. (2011) explain, managers make capital budgeting decisions based on the

assumption that the primary goal of the business is to maximise the shareholders’ wealth.

If this consideration is true, firms will invest in projects that will yield a positive NPV.

Some important research supports this point of view. Kester et al. (1999), Graham and

Harvey (2001) and others explain why DCF techniques have become a dominant

technique for evaluating capital budgeting decisions, particularly in large and more

structured enterprises. However, in their research, Graham and Harvey (2001) conclude

that due to limited managerial skills (particularly in SMEs), less complicated techniques

such as the payback method continue to dominate capital budgeting decision making. In

this study, the survey covered the use of all different techniques, including both capital

budgeting discounted and non-discounted capital budgeting methods. Table 1 shows the

results.

Table 1 Capital budgeting techniques used by firms

Method IRR NPV PI PP ARR

Number of firm 10 24 7 26 4

Source: Author’s calculation

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

48 M. Rossi

The results suggest that the PP technique was the most frequently used method to

evaluate capital budgeting decisions (36.62% of respondents). This was followed by the

NPV method (33.80%), IRR (14.08%), profitability index (9.86%) and accounting rate of

return (5.63%).2 It is necessary to remember that many of the CFOs-entrepreneurs

indicated that they did not use any techniques. In their evaluations, they used only their

intuition. The payback period method was the most popular among SMEs, while the

larger firms used the NPV technique.

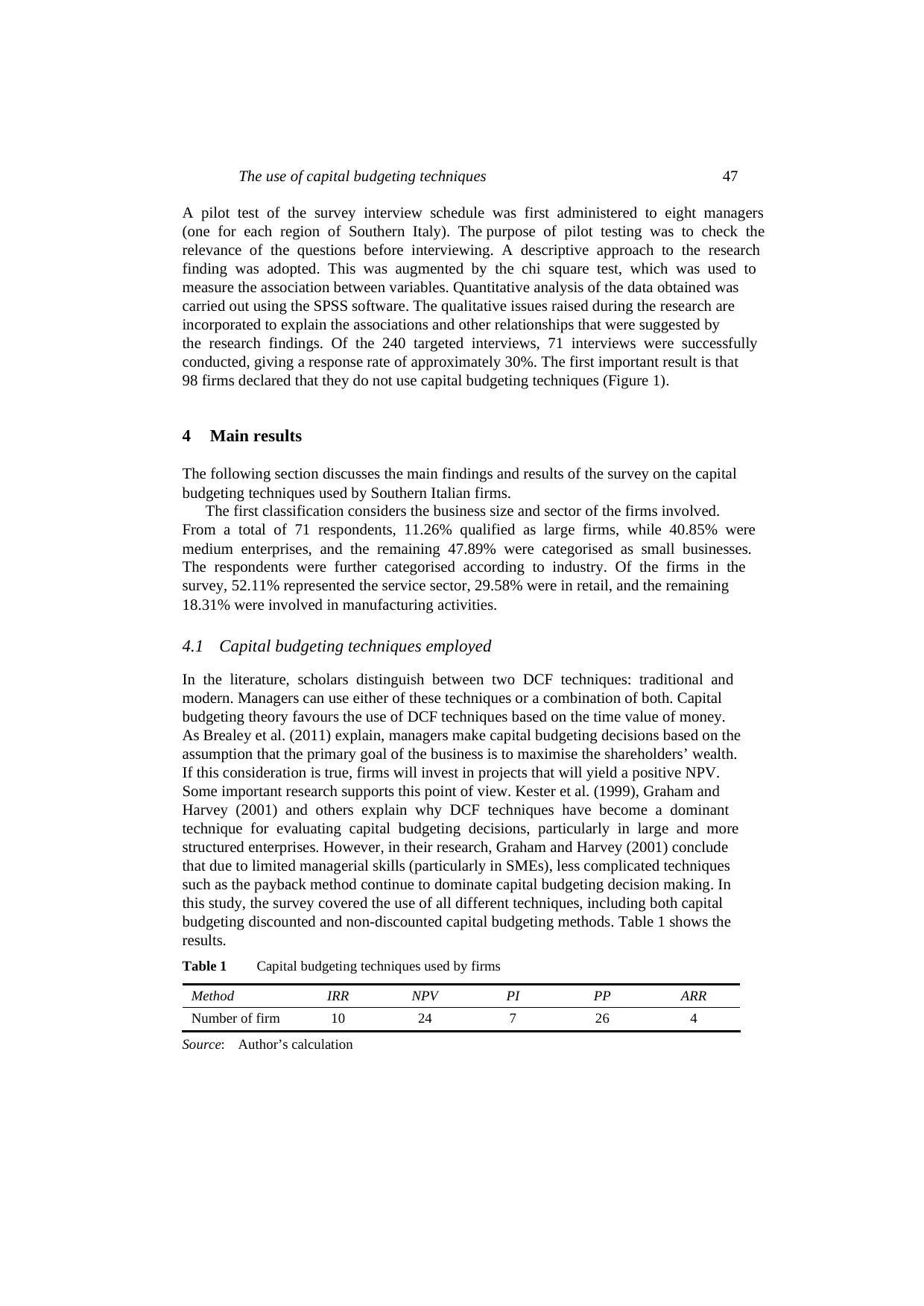

4.2 Level of qualification and capital budgeting

techniques used by sector

The survey sought to determine whether there was any relationship between capital

budgeting decision makers and their level of qualification. In fact, the survey respondents

do exhibit a different level of involvement. Table 2 shows the formal educational

qualifications of the responding decision makers.

Table 2 Capital budgeting method by sector usage

Technique Manufacturing (%) Retail (%) Service (%)

IRR 22 26 31

NPV 26 38 41

PI 19 32 33

PP 45 38 36

ARR 20 19 27

Source: Author’s calculation

The research highlights that those decision makers who had a high school diploma

primarily used their intuition compared with those who had received formal training.

However, a deeper analysis revealed that DCF was used more often by those who had

received formal accounting-finance training. A closer look at the firms that used multiple

methods indicates that most of their decision makers belonged to the post-graduate

category. However, the chi-squared test indicates that there is no association between the

level of qualification and the number of methods used. Table 2 shows the usage

percentage of the different methods by business sector.

The research findings show that the PP is more likely to be used by firms in the

manufacturing sector, while firms in the services sector prefer the IRR. The NPV method

seemed to be used to the same extent by firms in both the retail and service sectors. The

ARR seemed to be the least used technique across all business sectors.

In general, based on the chi-squared test analysis, there seemed to be no association

between the size of the business and the use of the different capital budgeting techniques.

The research established that 69% of the firms surveyed used only one technique;

whereas 31% of the respondents used at least two different techniques. Those that used

more than two methods belonged to the post-graduate category.

The results suggest that the PP technique was the most frequently used method to

evaluate capital budgeting decisions (36.62% of respondents). This was followed by the

NPV method (33.80%), IRR (14.08%), profitability index (9.86%) and accounting rate of

return (5.63%).2 It is necessary to remember that many of the CFOs-entrepreneurs

indicated that they did not use any techniques. In their evaluations, they used only their

intuition. The payback period method was the most popular among SMEs, while the

larger firms used the NPV technique.

4.2 Level of qualification and capital budgeting

techniques used by sector

The survey sought to determine whether there was any relationship between capital

budgeting decision makers and their level of qualification. In fact, the survey respondents

do exhibit a different level of involvement. Table 2 shows the formal educational

qualifications of the responding decision makers.

Table 2 Capital budgeting method by sector usage

Technique Manufacturing (%) Retail (%) Service (%)

IRR 22 26 31

NPV 26 38 41

PI 19 32 33

PP 45 38 36

ARR 20 19 27

Source: Author’s calculation

The research highlights that those decision makers who had a high school diploma

primarily used their intuition compared with those who had received formal training.

However, a deeper analysis revealed that DCF was used more often by those who had

received formal accounting-finance training. A closer look at the firms that used multiple

methods indicates that most of their decision makers belonged to the post-graduate

category. However, the chi-squared test indicates that there is no association between the

level of qualification and the number of methods used. Table 2 shows the usage

percentage of the different methods by business sector.

The research findings show that the PP is more likely to be used by firms in the

manufacturing sector, while firms in the services sector prefer the IRR. The NPV method

seemed to be used to the same extent by firms in both the retail and service sectors. The

ARR seemed to be the least used technique across all business sectors.

In general, based on the chi-squared test analysis, there seemed to be no association

between the size of the business and the use of the different capital budgeting techniques.

The research established that 69% of the firms surveyed used only one technique;

whereas 31% of the respondents used at least two different techniques. Those that used

more than two methods belonged to the post-graduate category.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The use of capital budgeting techniques 49

Figure 2 Qualifications of personnel responsible for capital budgeting (see online version

for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

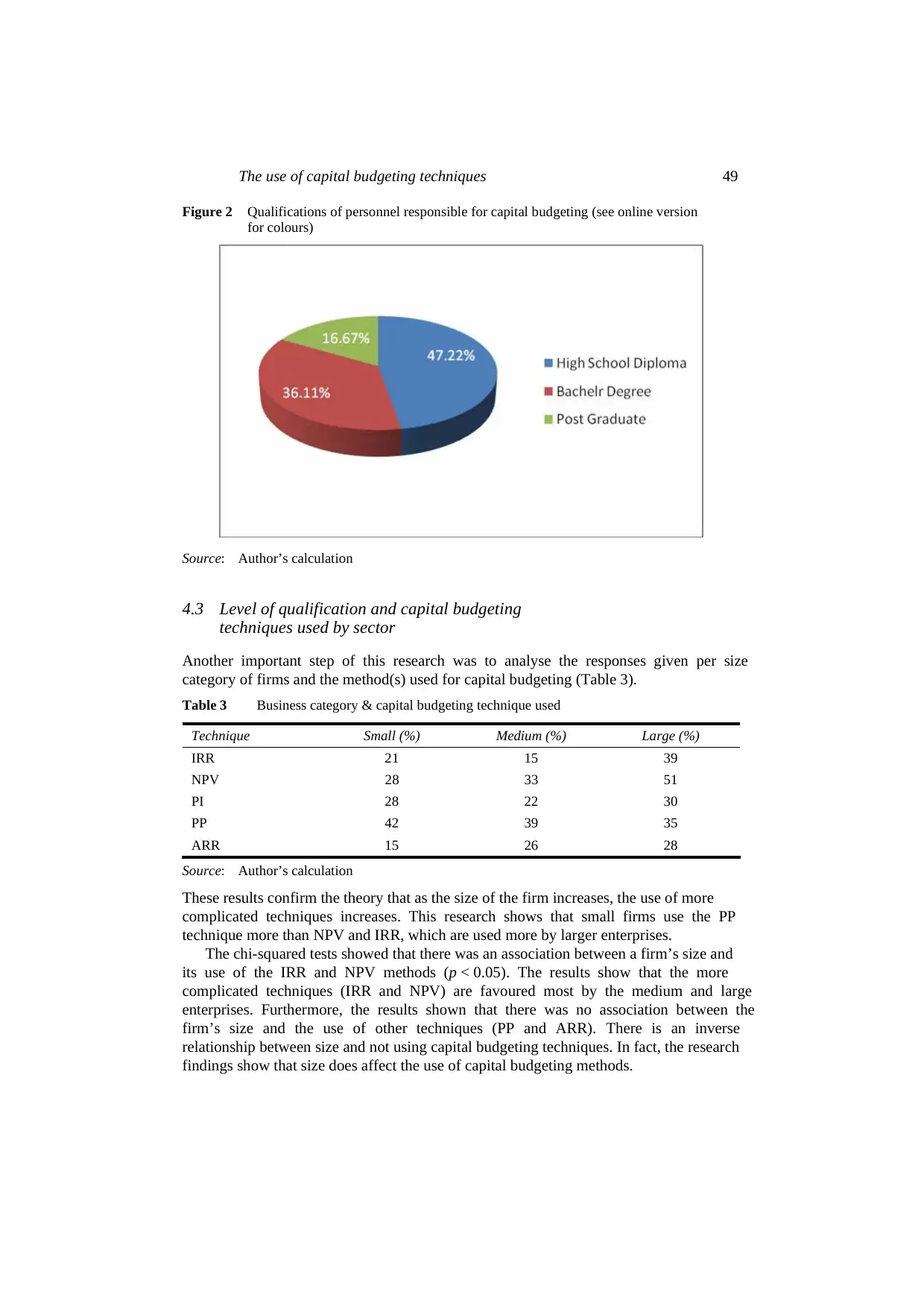

4.3 Level of qualification and capital budgeting

techniques used by sector

Another important step of this research was to analyse the responses given per size

category of firms and the method(s) used for capital budgeting (Table 3).

Table 3 Business category & capital budgeting technique used

Technique Small (%) Medium (%) Large (%)

IRR 21 15 39

NPV 28 33 51

PI 28 22 30

PP 42 39 35

ARR 15 26 28

Source: Author’s calculation

These results confirm the theory that as the size of the firm increases, the use of more

complicated techniques increases. This research shows that small firms use the PP

technique more than NPV and IRR, which are used more by larger enterprises.

The chi-squared tests showed that there was an association between a firm’s size and

its use of the IRR and NPV methods (p < 0.05). The results show that the more

complicated techniques (IRR and NPV) are favoured most by the medium and large

enterprises. Furthermore, the results shown that there was no association between the

firm’s size and the use of other techniques (PP and ARR). There is an inverse

relationship between size and not using capital budgeting techniques. In fact, the research

findings show that size does affect the use of capital budgeting methods.

Figure 2 Qualifications of personnel responsible for capital budgeting (see online version

for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

4.3 Level of qualification and capital budgeting

techniques used by sector

Another important step of this research was to analyse the responses given per size

category of firms and the method(s) used for capital budgeting (Table 3).

Table 3 Business category & capital budgeting technique used

Technique Small (%) Medium (%) Large (%)

IRR 21 15 39

NPV 28 33 51

PI 28 22 30

PP 42 39 35

ARR 15 26 28

Source: Author’s calculation

These results confirm the theory that as the size of the firm increases, the use of more

complicated techniques increases. This research shows that small firms use the PP

technique more than NPV and IRR, which are used more by larger enterprises.

The chi-squared tests showed that there was an association between a firm’s size and

its use of the IRR and NPV methods (p < 0.05). The results show that the more

complicated techniques (IRR and NPV) are favoured most by the medium and large

enterprises. Furthermore, the results shown that there was no association between the

firm’s size and the use of other techniques (PP and ARR). There is an inverse

relationship between size and not using capital budgeting techniques. In fact, the research

findings show that size does affect the use of capital budgeting methods.

50 M. Rossi

In particular, the results show the following:

1 The PP method was equally used across enterprises of all sizes, and

2 The smaller the size of a business, the less likely the business is to use capital

budgeting techniques (p < 0.05).

4.4 Sector of business and the most important stage in capital budgeting

Capital budgeting techniques are complex processes based on different steps. Some

authors define five interrelated stages: “namely proposal generation, review and analysis,

decision making, implementation and follow-up” (Gitman, 2007, p.380).

In this study, capital budgeting decisions were categorised into four steps:

project definition,

analysis and selection,

implementation, and

review.

Each of these stages is important, but managers–entrepreneurs give different weights to

each of these steps. To verify the importance attached to each stage in the capital

budgeting process, the respondents were asked to rate each of the four stages in order of

importance on a scale of 1–4 (with 4 being most important). Table 4 summarises the

responses.

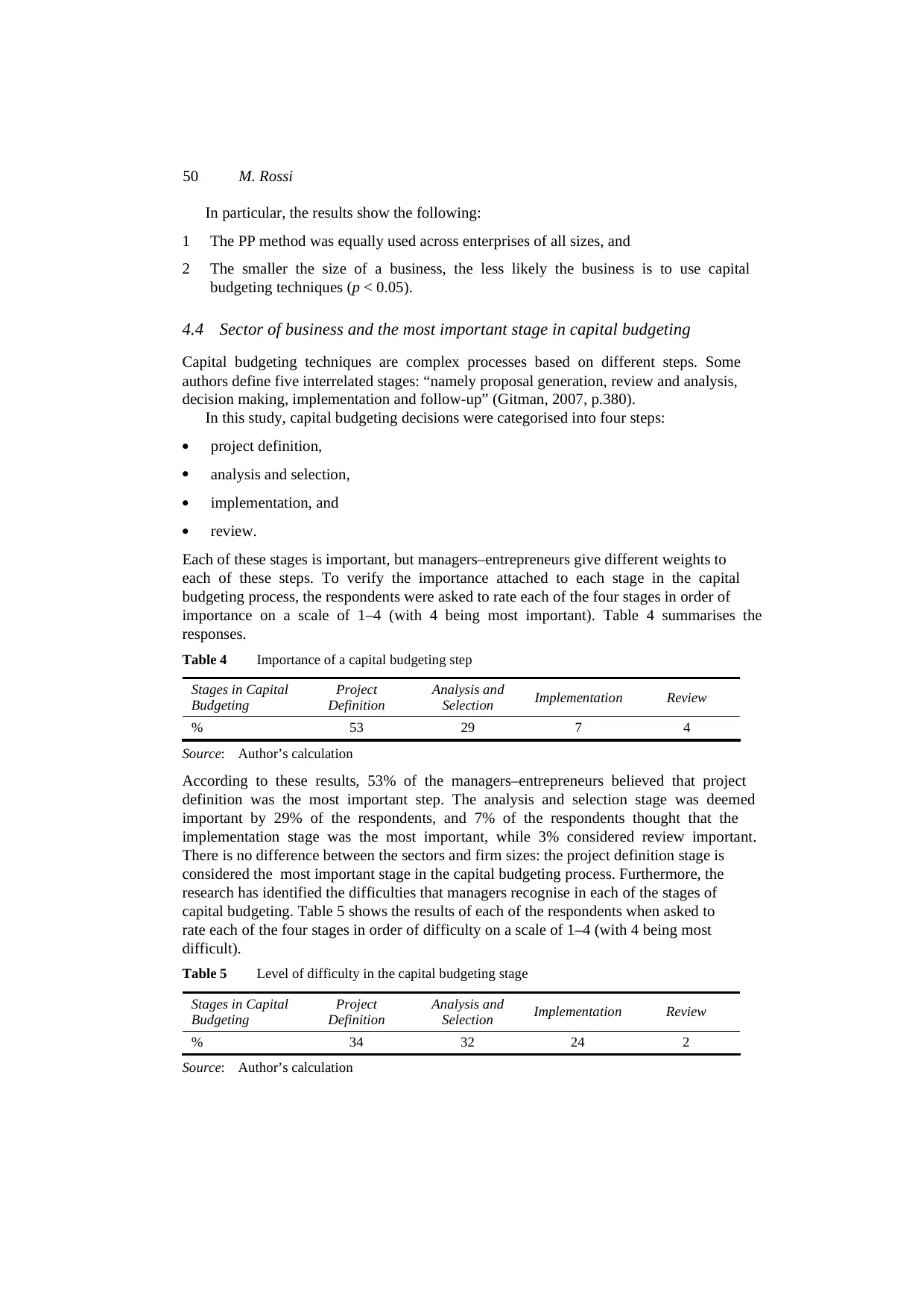

Table 4 Importance of a capital budgeting step

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

% 53 29 7 4

Source: Author’s calculation

According to these results, 53% of the managers–entrepreneurs believed that project

definition was the most important step. The analysis and selection stage was deemed

important by 29% of the respondents, and 7% of the respondents thought that the

implementation stage was the most important, while 3% considered review important.

There is no difference between the sectors and firm sizes: the project definition stage is

considered the most important stage in the capital budgeting process. Furthermore, the

research has identified the difficulties that managers recognise in each of the stages of

capital budgeting. Table 5 shows the results of each of the respondents when asked to

rate each of the four stages in order of difficulty on a scale of 1–4 (with 4 being most

difficult).

Table 5 Level of difficulty in the capital budgeting stage

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

% 34 32 24 2

Source: Author’s calculation

In particular, the results show the following:

1 The PP method was equally used across enterprises of all sizes, and

2 The smaller the size of a business, the less likely the business is to use capital

budgeting techniques (p < 0.05).

4.4 Sector of business and the most important stage in capital budgeting

Capital budgeting techniques are complex processes based on different steps. Some

authors define five interrelated stages: “namely proposal generation, review and analysis,

decision making, implementation and follow-up” (Gitman, 2007, p.380).

In this study, capital budgeting decisions were categorised into four steps:

project definition,

analysis and selection,

implementation, and

review.

Each of these stages is important, but managers–entrepreneurs give different weights to

each of these steps. To verify the importance attached to each stage in the capital

budgeting process, the respondents were asked to rate each of the four stages in order of

importance on a scale of 1–4 (with 4 being most important). Table 4 summarises the

responses.

Table 4 Importance of a capital budgeting step

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

% 53 29 7 4

Source: Author’s calculation

According to these results, 53% of the managers–entrepreneurs believed that project

definition was the most important step. The analysis and selection stage was deemed

important by 29% of the respondents, and 7% of the respondents thought that the

implementation stage was the most important, while 3% considered review important.

There is no difference between the sectors and firm sizes: the project definition stage is

considered the most important stage in the capital budgeting process. Furthermore, the

research has identified the difficulties that managers recognise in each of the stages of

capital budgeting. Table 5 shows the results of each of the respondents when asked to

rate each of the four stages in order of difficulty on a scale of 1–4 (with 4 being most

difficult).

Table 5 Level of difficulty in the capital budgeting stage

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

% 34 32 24 2

Source: Author’s calculation

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The use of capital budgeting techniques 51

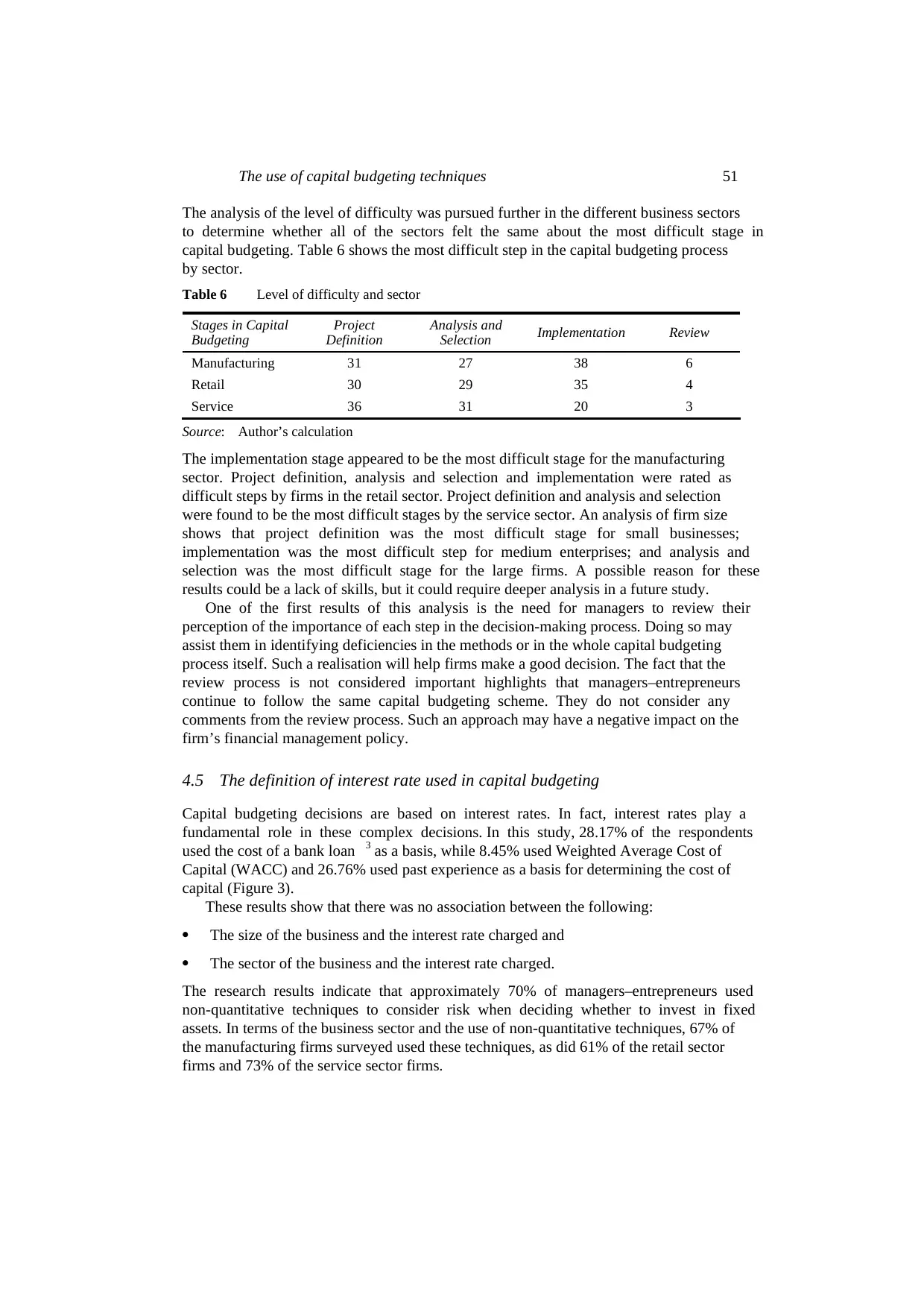

The analysis of the level of difficulty was pursued further in the different business sectors

to determine whether all of the sectors felt the same about the most difficult stage in

capital budgeting. Table 6 shows the most difficult step in the capital budgeting process

by sector.

Table 6 Level of difficulty and sector

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

Manufacturing 31 27 38 6

Retail 30 29 35 4

Service 36 31 20 3

Source: Author’s calculation

The implementation stage appeared to be the most difficult stage for the manufacturing

sector. Project definition, analysis and selection and implementation were rated as

difficult steps by firms in the retail sector. Project definition and analysis and selection

were found to be the most difficult stages by the service sector. An analysis of firm size

shows that project definition was the most difficult stage for small businesses;

implementation was the most difficult step for medium enterprises; and analysis and

selection was the most difficult stage for the large firms. A possible reason for these

results could be a lack of skills, but it could require deeper analysis in a future study.

One of the first results of this analysis is the need for managers to review their

perception of the importance of each step in the decision-making process. Doing so may

assist them in identifying deficiencies in the methods or in the whole capital budgeting

process itself. Such a realisation will help firms make a good decision. The fact that the

review process is not considered important highlights that managers–entrepreneurs

continue to follow the same capital budgeting scheme. They do not consider any

comments from the review process. Such an approach may have a negative impact on the

firm’s financial management policy.

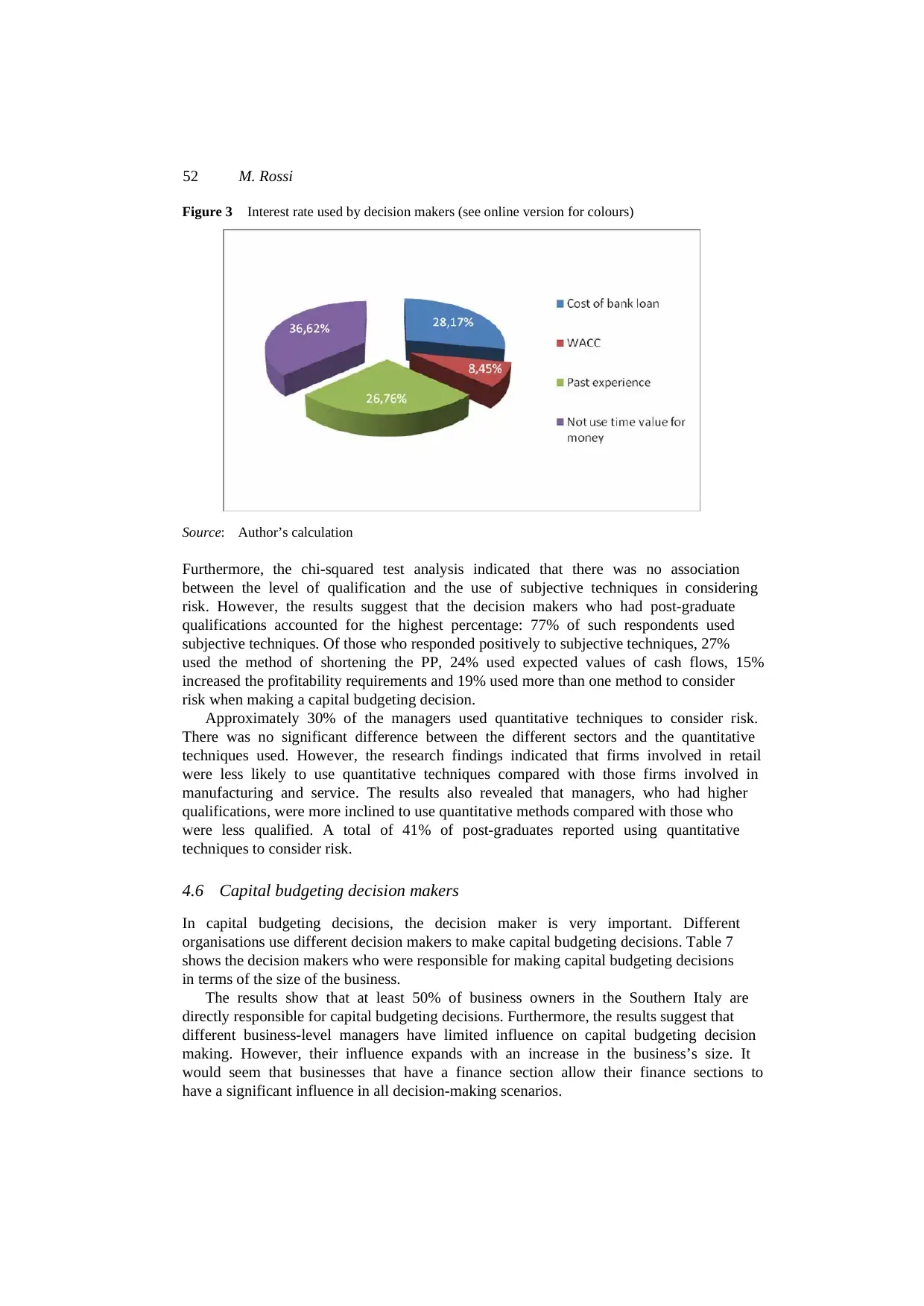

4.5 The definition of interest rate used in capital budgeting

Capital budgeting decisions are based on interest rates. In fact, interest rates play a

fundamental role in these complex decisions. In this study, 28.17% of the respondents

used the cost of a bank loan 3 as a basis, while 8.45% used Weighted Average Cost of

Capital (WACC) and 26.76% used past experience as a basis for determining the cost of

capital (Figure 3).

These results show that there was no association between the following:

The size of the business and the interest rate charged and

The sector of the business and the interest rate charged.

The research results indicate that approximately 70% of managers–entrepreneurs used

non-quantitative techniques to consider risk when deciding whether to invest in fixed

assets. In terms of the business sector and the use of non-quantitative techniques, 67% of

the manufacturing firms surveyed used these techniques, as did 61% of the retail sector

firms and 73% of the service sector firms.

The analysis of the level of difficulty was pursued further in the different business sectors

to determine whether all of the sectors felt the same about the most difficult stage in

capital budgeting. Table 6 shows the most difficult step in the capital budgeting process

by sector.

Table 6 Level of difficulty and sector

Stages in Capital

Budgeting

Project

Definition

Analysis and

Selection Implementation Review

Manufacturing 31 27 38 6

Retail 30 29 35 4

Service 36 31 20 3

Source: Author’s calculation

The implementation stage appeared to be the most difficult stage for the manufacturing

sector. Project definition, analysis and selection and implementation were rated as

difficult steps by firms in the retail sector. Project definition and analysis and selection

were found to be the most difficult stages by the service sector. An analysis of firm size

shows that project definition was the most difficult stage for small businesses;

implementation was the most difficult step for medium enterprises; and analysis and

selection was the most difficult stage for the large firms. A possible reason for these

results could be a lack of skills, but it could require deeper analysis in a future study.

One of the first results of this analysis is the need for managers to review their

perception of the importance of each step in the decision-making process. Doing so may

assist them in identifying deficiencies in the methods or in the whole capital budgeting

process itself. Such a realisation will help firms make a good decision. The fact that the

review process is not considered important highlights that managers–entrepreneurs

continue to follow the same capital budgeting scheme. They do not consider any

comments from the review process. Such an approach may have a negative impact on the

firm’s financial management policy.

4.5 The definition of interest rate used in capital budgeting

Capital budgeting decisions are based on interest rates. In fact, interest rates play a

fundamental role in these complex decisions. In this study, 28.17% of the respondents

used the cost of a bank loan 3 as a basis, while 8.45% used Weighted Average Cost of

Capital (WACC) and 26.76% used past experience as a basis for determining the cost of

capital (Figure 3).

These results show that there was no association between the following:

The size of the business and the interest rate charged and

The sector of the business and the interest rate charged.

The research results indicate that approximately 70% of managers–entrepreneurs used

non-quantitative techniques to consider risk when deciding whether to invest in fixed

assets. In terms of the business sector and the use of non-quantitative techniques, 67% of

the manufacturing firms surveyed used these techniques, as did 61% of the retail sector

firms and 73% of the service sector firms.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

52 M. Rossi

Figure 3 Interest rate used by decision makers (see online version for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

Furthermore, the chi-squared test analysis indicated that there was no association

between the level of qualification and the use of subjective techniques in considering

risk. However, the results suggest that the decision makers who had post-graduate

qualifications accounted for the highest percentage: 77% of such respondents used

subjective techniques. Of those who responded positively to subjective techniques, 27%

used the method of shortening the PP, 24% used expected values of cash flows, 15%

increased the profitability requirements and 19% used more than one method to consider

risk when making a capital budgeting decision.

Approximately 30% of the managers used quantitative techniques to consider risk.

There was no significant difference between the different sectors and the quantitative

techniques used. However, the research findings indicated that firms involved in retail

were less likely to use quantitative techniques compared with those firms involved in

manufacturing and service. The results also revealed that managers, who had higher

qualifications, were more inclined to use quantitative methods compared with those who

were less qualified. A total of 41% of post-graduates reported using quantitative

techniques to consider risk.

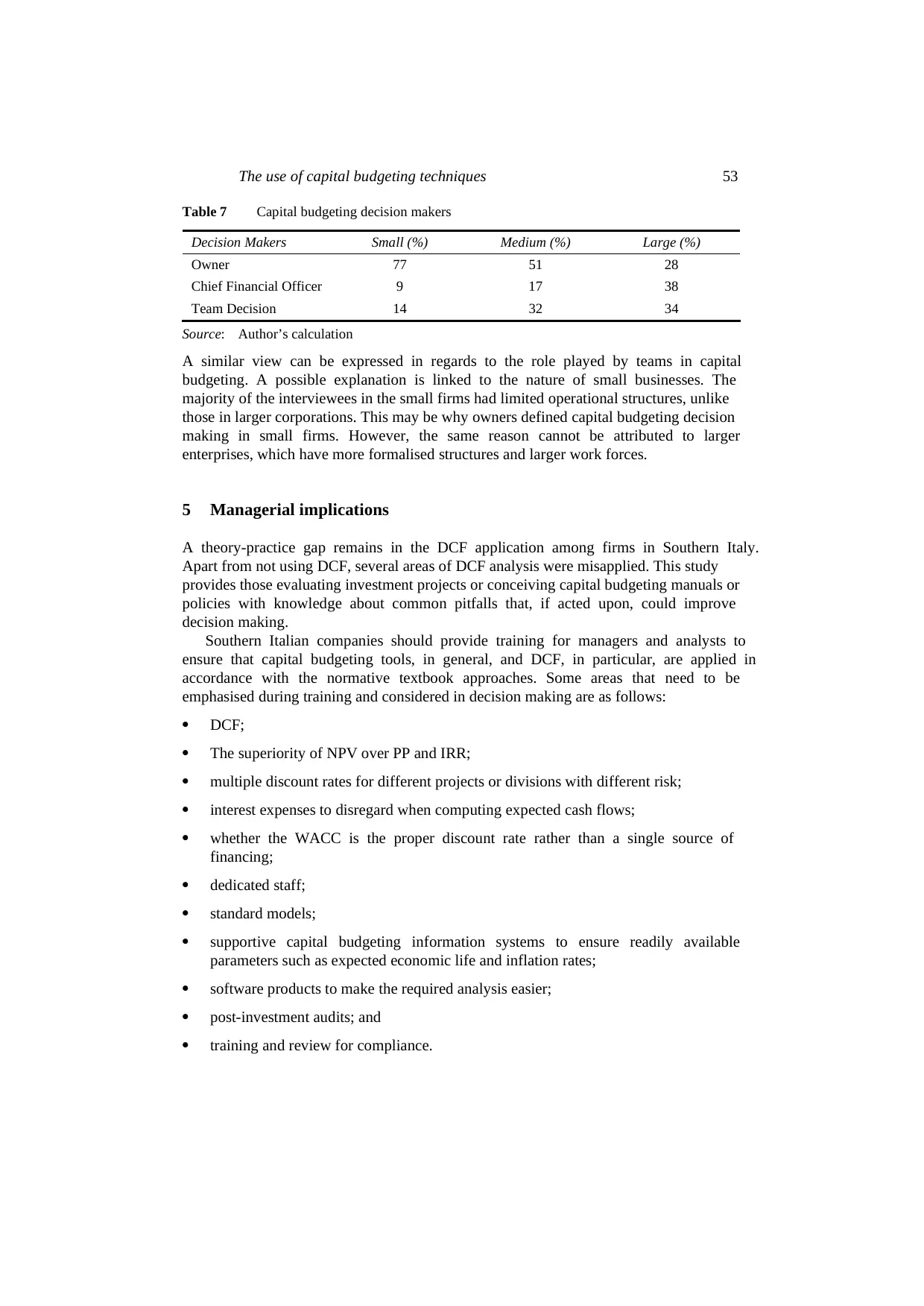

4.6 Capital budgeting decision makers

In capital budgeting decisions, the decision maker is very important. Different

organisations use different decision makers to make capital budgeting decisions. Table 7

shows the decision makers who were responsible for making capital budgeting decisions

in terms of the size of the business.

The results show that at least 50% of business owners in the Southern Italy are

directly responsible for capital budgeting decisions. Furthermore, the results suggest that

different business-level managers have limited influence on capital budgeting decision

making. However, their influence expands with an increase in the business’s size. It

would seem that businesses that have a finance section allow their finance sections to

have a significant influence in all decision-making scenarios.

Figure 3 Interest rate used by decision makers (see online version for colours)

Source: Author’s calculation

Furthermore, the chi-squared test analysis indicated that there was no association

between the level of qualification and the use of subjective techniques in considering

risk. However, the results suggest that the decision makers who had post-graduate

qualifications accounted for the highest percentage: 77% of such respondents used

subjective techniques. Of those who responded positively to subjective techniques, 27%

used the method of shortening the PP, 24% used expected values of cash flows, 15%

increased the profitability requirements and 19% used more than one method to consider

risk when making a capital budgeting decision.

Approximately 30% of the managers used quantitative techniques to consider risk.

There was no significant difference between the different sectors and the quantitative

techniques used. However, the research findings indicated that firms involved in retail

were less likely to use quantitative techniques compared with those firms involved in

manufacturing and service. The results also revealed that managers, who had higher

qualifications, were more inclined to use quantitative methods compared with those who

were less qualified. A total of 41% of post-graduates reported using quantitative

techniques to consider risk.

4.6 Capital budgeting decision makers

In capital budgeting decisions, the decision maker is very important. Different

organisations use different decision makers to make capital budgeting decisions. Table 7

shows the decision makers who were responsible for making capital budgeting decisions

in terms of the size of the business.

The results show that at least 50% of business owners in the Southern Italy are

directly responsible for capital budgeting decisions. Furthermore, the results suggest that

different business-level managers have limited influence on capital budgeting decision

making. However, their influence expands with an increase in the business’s size. It

would seem that businesses that have a finance section allow their finance sections to

have a significant influence in all decision-making scenarios.

The use of capital budgeting techniques 53

Table 7 Capital budgeting decision makers

Decision Makers Small (%) Medium (%) Large (%)

Owner 77 51 28

Chief Financial Officer 9 17 38

Team Decision 14 32 34

Source: Author’s calculation

A similar view can be expressed in regards to the role played by teams in capital

budgeting. A possible explanation is linked to the nature of small businesses. The

majority of the interviewees in the small firms had limited operational structures, unlike

those in larger corporations. This may be why owners defined capital budgeting decision

making in small firms. However, the same reason cannot be attributed to larger

enterprises, which have more formalised structures and larger work forces.

5 Managerial implications

A theory-practice gap remains in the DCF application among firms in Southern Italy.

Apart from not using DCF, several areas of DCF analysis were misapplied. This study

provides those evaluating investment projects or conceiving capital budgeting manuals or

policies with knowledge about common pitfalls that, if acted upon, could improve

decision making.

Southern Italian companies should provide training for managers and analysts to

ensure that capital budgeting tools, in general, and DCF, in particular, are applied in

accordance with the normative textbook approaches. Some areas that need to be

emphasised during training and considered in decision making are as follows:

DCF;

The superiority of NPV over PP and IRR;

multiple discount rates for different projects or divisions with different risk;

interest expenses to disregard when computing expected cash flows;

whether the WACC is the proper discount rate rather than a single source of

financing;

dedicated staff;

standard models;

supportive capital budgeting information systems to ensure readily available

parameters such as expected economic life and inflation rates;

software products to make the required analysis easier;

post-investment audits; and

training and review for compliance.

Table 7 Capital budgeting decision makers

Decision Makers Small (%) Medium (%) Large (%)

Owner 77 51 28

Chief Financial Officer 9 17 38

Team Decision 14 32 34

Source: Author’s calculation

A similar view can be expressed in regards to the role played by teams in capital

budgeting. A possible explanation is linked to the nature of small businesses. The

majority of the interviewees in the small firms had limited operational structures, unlike

those in larger corporations. This may be why owners defined capital budgeting decision

making in small firms. However, the same reason cannot be attributed to larger

enterprises, which have more formalised structures and larger work forces.

5 Managerial implications

A theory-practice gap remains in the DCF application among firms in Southern Italy.

Apart from not using DCF, several areas of DCF analysis were misapplied. This study

provides those evaluating investment projects or conceiving capital budgeting manuals or

policies with knowledge about common pitfalls that, if acted upon, could improve

decision making.

Southern Italian companies should provide training for managers and analysts to

ensure that capital budgeting tools, in general, and DCF, in particular, are applied in

accordance with the normative textbook approaches. Some areas that need to be

emphasised during training and considered in decision making are as follows:

DCF;

The superiority of NPV over PP and IRR;

multiple discount rates for different projects or divisions with different risk;

interest expenses to disregard when computing expected cash flows;

whether the WACC is the proper discount rate rather than a single source of

financing;

dedicated staff;

standard models;

supportive capital budgeting information systems to ensure readily available

parameters such as expected economic life and inflation rates;

software products to make the required analysis easier;

post-investment audits; and

training and review for compliance.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.