Capital Budgeting Practices: A Survey of CEE Companies

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/12

|25

|19103

|406

Report

AI Summary

This report presents the findings of a comprehensive survey on capital budgeting practices in Central and Eastern European (CEE) firms. The study, conducted across ten CEE countries, examines how firms make investment decisions, focusing on the use of discounted cash flow (DCF), payback period, and accounting-based methods. The research explores the influence of firm size, multinational culture, firm goals, code of ethics, executive ownership, and other factors on capital budgeting choices. The survey reveals significant variations in practices compared to those in developed economies, highlighting the impact of national culture, legal systems, and market characteristics. The results indicate that the use of DCF is positively correlated with firm size, management culture, and business ethics. Furthermore, the study compares these practices with those in 25 other countries and discusses the implications for both practitioners and investors. The research also considers how factors such as lack of financial resources, strategic fit, and trust in data can influence project acceptance, even when advanced techniques are used. The report provides valuable insights into the capital budgeting landscape in transitional economies and contributes to the understanding of corporate finance practices globally.

Capital budgeting practices: A survey of Central

and Eastern European firms☆

Gyorgy Andora, Sunil K. Mohantyb,⁎, Tamas Totha

a Department of Finance, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary

b Department of Finance, Brooklyn College, City University of New York (CUNY), Brooklyn, NY 11210, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 17 November 2013

Received in revised form 22 February 2015

Accepted 2 April 2015

Available online 10 April 2015

We survey 400 executives in ten countries in Central and Eastern Europe

(CEE) and report the results of their companies'capital budgeting

practices. We find that capital budgeting practices in CEE countries are

influenced mostly by firm size, multinational culture, firms' goals, and

the presence of code of ethics, and to a lesser extent, by executive own-

ership, number of projects analyzed, and target leverage. We compare

our results with prior studies and find significant variations in capital

budgeting practices across 35 countries,among high,upper middle,

and lower middle income countries,and across seven geographic

regions.

© 2015 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification:

G31

G32

F23

Keywords:

Capital budgeting

Cost of capital

Central and Eastern Europe

1. Introduction

Capital budgeting decisions are among the most important decisions that the financial manager of a firm

has to make. Capital budgeting process refers to the process of selection of investment projects that maximize

shareholder value. Prior studies related to capital budgeting practices have mostly focused on developed

Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Emerging Markets Review

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e m r

and Eastern European firms☆

Gyorgy Andora, Sunil K. Mohantyb,⁎, Tamas Totha

a Department of Finance, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary

b Department of Finance, Brooklyn College, City University of New York (CUNY), Brooklyn, NY 11210, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 17 November 2013

Received in revised form 22 February 2015

Accepted 2 April 2015

Available online 10 April 2015

We survey 400 executives in ten countries in Central and Eastern Europe

(CEE) and report the results of their companies'capital budgeting

practices. We find that capital budgeting practices in CEE countries are

influenced mostly by firm size, multinational culture, firms' goals, and

the presence of code of ethics, and to a lesser extent, by executive own-

ership, number of projects analyzed, and target leverage. We compare

our results with prior studies and find significant variations in capital

budgeting practices across 35 countries,among high,upper middle,

and lower middle income countries,and across seven geographic

regions.

© 2015 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification:

G31

G32

F23

Keywords:

Capital budgeting

Cost of capital

Central and Eastern Europe

1. Introduction

Capital budgeting decisions are among the most important decisions that the financial manager of a firm

has to make. Capital budgeting process refers to the process of selection of investment projects that maximize

shareholder value. Prior studies related to capital budgeting practices have mostly focused on developed

Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Emerging Markets Review

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e m r

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

economies (e.g., U.S., Canada, Australia, and Western European countries). However, much less is known

about how capital budgeting decisions are made in transitional economies (e.g., post-communist countries

in Central and Eastern Europe), which is the topic of this paper.

Previous research (e.g., Bennouna et al., 2010; Brounen et al., 2004; Graham and Harvey, 2001) addresses

how corporate finance theories have been adopted by financial managers in practice. However, one would

argue that most of the stylized facts are likely to be rooted in the U.S. and Western European empirical evi-

dence. Several studies document fundamental differences between financial markets, legal systems, and insti-

tutional settings, when comparing the U.S. with Western Europe (e.g., La Porta et al., 1997, 1998). Among

countries and regions, there are significant differences in the extent to which investors are protected from ex-

propriation by managers (e.g., La Porta et al., 2000). Rajan and Zingales (2003) indicate that institution-heavy

relationship-based system is more prevalent in continental Europe, while the market-intensive arms' length

system is more prevalent in the U.S. and Canada. Chew (1997) finds that market-based corporate governance

system differs significantly from the insider-based or relationship-based governance system. For example,

Brounen et al. (2004) provide survey evidence that firms in the U.K. and the Netherlands strive to maximize

shareholders' wealth, while German and French firms attach a low priority to this corporate goal. Licht et al.

(2005, 2007) show how culture, law, and corporate governance mechanisms affect corporate management

decisions. Stulz and Williamson (2003) suggest that corporate financial practices are influenced by national

culture. Similarly, Li et al. (2013) provide theoretic model and empirical evidence on how national culture in-

fluences corporate risk-taking behavior. Finally, most of corporate finance theories have been developed

under the assumption that capital markets are “semi-strong” efficient. However, this assumption seems to

be questionable when it is applied to emerging markets that are typically characterized by higher information

asymmetries, higher transaction costs, relatively concentrated ownership with small and medium enter-

prises, and relatively low market liquidity. For example, Maquieira et al. (2012) and Mendes-Da-Silva and

Saito (2014) find evidence that capital budgeting practices of firms in Latin America where capital markets

are still emerging are significantly different from those of developed countries.

In this study, we conduct a comprehensive survey that asks business executives from a wide range of firms

in the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region1 to describe their choices related to capital budgeting analysis

and decisions. We measure the extent to which corporate finance theories explain the capital budgeting prac-

tices in Central and Eastern European countries. The CEE region consists of several small, open economies

where most of the GDP is produced by small- and medium-sized companies with a strong interdependence

on multinational companies. We include ten CEE countries in our survey. These countries are considered

either high or middle income countries based on the OECD classification.2 CEE countries are characterized

by diverse culture, languages, legal systems, institutional settings, and corporate governance mechanisms.

These countries tend to have a well-developed banking system, but they tend to have less developed capital

markets that are likely be less efficient and less liquid than developed capital markets. The levels of economic

and financial development in CEE countries tend to be lower than those of developed countries in North

America and Western Europe. Most firms in CEE countries tend to be small or medium private enterprises.

Given the significant differences between developed and emerging economies; between efficient and less-

149G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

about how capital budgeting decisions are made in transitional economies (e.g., post-communist countries

in Central and Eastern Europe), which is the topic of this paper.

Previous research (e.g., Bennouna et al., 2010; Brounen et al., 2004; Graham and Harvey, 2001) addresses

how corporate finance theories have been adopted by financial managers in practice. However, one would

argue that most of the stylized facts are likely to be rooted in the U.S. and Western European empirical evi-

dence. Several studies document fundamental differences between financial markets, legal systems, and insti-

tutional settings, when comparing the U.S. with Western Europe (e.g., La Porta et al., 1997, 1998). Among

countries and regions, there are significant differences in the extent to which investors are protected from ex-

propriation by managers (e.g., La Porta et al., 2000). Rajan and Zingales (2003) indicate that institution-heavy

relationship-based system is more prevalent in continental Europe, while the market-intensive arms' length

system is more prevalent in the U.S. and Canada. Chew (1997) finds that market-based corporate governance

system differs significantly from the insider-based or relationship-based governance system. For example,

Brounen et al. (2004) provide survey evidence that firms in the U.K. and the Netherlands strive to maximize

shareholders' wealth, while German and French firms attach a low priority to this corporate goal. Licht et al.

(2005, 2007) show how culture, law, and corporate governance mechanisms affect corporate management

decisions. Stulz and Williamson (2003) suggest that corporate financial practices are influenced by national

culture. Similarly, Li et al. (2013) provide theoretic model and empirical evidence on how national culture in-

fluences corporate risk-taking behavior. Finally, most of corporate finance theories have been developed

under the assumption that capital markets are “semi-strong” efficient. However, this assumption seems to

be questionable when it is applied to emerging markets that are typically characterized by higher information

asymmetries, higher transaction costs, relatively concentrated ownership with small and medium enter-

prises, and relatively low market liquidity. For example, Maquieira et al. (2012) and Mendes-Da-Silva and

Saito (2014) find evidence that capital budgeting practices of firms in Latin America where capital markets

are still emerging are significantly different from those of developed countries.

In this study, we conduct a comprehensive survey that asks business executives from a wide range of firms

in the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region1 to describe their choices related to capital budgeting analysis

and decisions. We measure the extent to which corporate finance theories explain the capital budgeting prac-

tices in Central and Eastern European countries. The CEE region consists of several small, open economies

where most of the GDP is produced by small- and medium-sized companies with a strong interdependence

on multinational companies. We include ten CEE countries in our survey. These countries are considered

either high or middle income countries based on the OECD classification.2 CEE countries are characterized

by diverse culture, languages, legal systems, institutional settings, and corporate governance mechanisms.

These countries tend to have a well-developed banking system, but they tend to have less developed capital

markets that are likely be less efficient and less liquid than developed capital markets. The levels of economic

and financial development in CEE countries tend to be lower than those of developed countries in North

America and Western Europe. Most firms in CEE countries tend to be small or medium private enterprises.

Given the significant differences between developed and emerging economies; between efficient and less-

149G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

2001); in South America: Argentina,Brazil, Chile, Colombia,Ecuador,Uruguay,Peru, and Venezuela

(Maquieira et al., 2012; Mendes-Da-Silva and Saito, 2014); in East Asia and Pacific: Australia, China, Hong

Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore (Hermes et al., 2007; Kester et al., 1999; Truong

et al., 2008); in South Asia: India (Singh et al., 2012); in Africa: South Africa (Correia and Cramer, 2008);

and in Western Europe: the U.K.,the Netherlands,Germany,France,Finland,and Sweden (Arnold and

Hatzopoulos, 2000; Brounen et al., 2004; Daunfeldt and Hartwig, 2014; Hermes et al., 2007; Holmén and

Pramborg, 2009; Liljeblom and Vaihekoski, 2004).

Our paper contributes to the corporate finance literature in a number of ways. First, we use the field study

method in finance, which to date remains a relatively rare approach in corporate finance literature. Second,

many previous studies applying comprehensive survey approaches focus only on developed countries such

as the USA, U.K. and Western Europe. In this study, we survey a large number of financial executives in ten

countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and report the results of their companies' capital budgeting

practices.We examine the use of different capital budgeting methods,and the relation between capital

budgeting practices and the general goals of firms. Therefore, our survey results are useful to both practi-

tioners and investors because they will learn more about capital budgeting practices of firms in CEE countries.

To our knowledge, none of the empirical studies has yet addressed capital budgeting practices of firms in CEE

countries that are next to the most developed economies in terms of GDP per capita except for Hernádi and

Ormos' (2012) study which provides an analysis and discussion on capital structure decisions in CEE coun-

tries. Third, this study is broader in scope than other capital budgeting surveys. We compare the corporate fi-

nance practices of 35 countries in seven geographic regions (Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe,

North America, South America, East Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and Africa) around the world. We also com-

pare capital budgeting practices among countries by economic development (high income, upper middle in-

come, and lower middle income).

We sample a large cross section of approximately 70,000 firms (excluding micro-firms) representing a

wide variety of firms and industries across ten CEE countries — Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary,

Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia. We collect 400 responses by conducting a

telephone survey. Then, we restrict our analysis to 333 sample firms that follow a formal capital budgeting

practice and thus create a sample size representing one of the largest survey samples in the financial litera-

ture.3 We analyze responses conditional on several key firm characteristics such as firm size, number of pro-

jects analyzed in a year,executive ownership,code of ethics,target leverage,and the role of Western

management culture. We also examine the relation between capital budgeting practices and general goals

of the companies. Our empirical evidence is consistent with several theoretical predictions and empirical find-

ings of earlier studies. The main results of our survey indicate that the use of discounted cash flow (DCF)

method in CEE countries is positively related to firm size (e.g., Brounen et al., 2004; Graham and Harvey,

2001; Hermes et al., 2007), management culture, and business ethics (e.g., Li et al., 2013; Licht et al., 2005;

Stulz and Williamson, 2003), and to a lesser extent, to the executive ownership, number of projects analyzed,

and target leverage. Our survey results suggest that that top executives of firms in CEE countries are mostly

concerned with the long-term performance (stability) and solvency (liquidity) of their firms instead of

150 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

(Maquieira et al., 2012; Mendes-Da-Silva and Saito, 2014); in East Asia and Pacific: Australia, China, Hong

Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore (Hermes et al., 2007; Kester et al., 1999; Truong

et al., 2008); in South Asia: India (Singh et al., 2012); in Africa: South Africa (Correia and Cramer, 2008);

and in Western Europe: the U.K.,the Netherlands,Germany,France,Finland,and Sweden (Arnold and

Hatzopoulos, 2000; Brounen et al., 2004; Daunfeldt and Hartwig, 2014; Hermes et al., 2007; Holmén and

Pramborg, 2009; Liljeblom and Vaihekoski, 2004).

Our paper contributes to the corporate finance literature in a number of ways. First, we use the field study

method in finance, which to date remains a relatively rare approach in corporate finance literature. Second,

many previous studies applying comprehensive survey approaches focus only on developed countries such

as the USA, U.K. and Western Europe. In this study, we survey a large number of financial executives in ten

countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and report the results of their companies' capital budgeting

practices.We examine the use of different capital budgeting methods,and the relation between capital

budgeting practices and the general goals of firms. Therefore, our survey results are useful to both practi-

tioners and investors because they will learn more about capital budgeting practices of firms in CEE countries.

To our knowledge, none of the empirical studies has yet addressed capital budgeting practices of firms in CEE

countries that are next to the most developed economies in terms of GDP per capita except for Hernádi and

Ormos' (2012) study which provides an analysis and discussion on capital structure decisions in CEE coun-

tries. Third, this study is broader in scope than other capital budgeting surveys. We compare the corporate fi-

nance practices of 35 countries in seven geographic regions (Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe,

North America, South America, East Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and Africa) around the world. We also com-

pare capital budgeting practices among countries by economic development (high income, upper middle in-

come, and lower middle income).

We sample a large cross section of approximately 70,000 firms (excluding micro-firms) representing a

wide variety of firms and industries across ten CEE countries — Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary,

Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia. We collect 400 responses by conducting a

telephone survey. Then, we restrict our analysis to 333 sample firms that follow a formal capital budgeting

practice and thus create a sample size representing one of the largest survey samples in the financial litera-

ture.3 We analyze responses conditional on several key firm characteristics such as firm size, number of pro-

jects analyzed in a year,executive ownership,code of ethics,target leverage,and the role of Western

management culture. We also examine the relation between capital budgeting practices and general goals

of the companies. Our empirical evidence is consistent with several theoretical predictions and empirical find-

ings of earlier studies. The main results of our survey indicate that the use of discounted cash flow (DCF)

method in CEE countries is positively related to firm size (e.g., Brounen et al., 2004; Graham and Harvey,

2001; Hermes et al., 2007), management culture, and business ethics (e.g., Li et al., 2013; Licht et al., 2005;

Stulz and Williamson, 2003), and to a lesser extent, to the executive ownership, number of projects analyzed,

and target leverage. Our survey results suggest that that top executives of firms in CEE countries are mostly

concerned with the long-term performance (stability) and solvency (liquidity) of their firms instead of

150 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

budgeting practices of six other geographic regions (e.g., Western Europe, North America, South America, East

Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and Africa). Consistent with findings of previous studies (e.g., La Porta et al. (1997,

1998, 2000), Hermes et al. (2007), and Maquieira et al. (2012)), we report significant variations in capital

budgeting practices across geographic regions and levels of economic development.4

The paper is organized as follows.In the next section, we provide a brief overview of prior studies on

capital budgeting practices. In Section 3, we present our methodology and describe our data set, sample de-

sign, and collection procedure. In Section 4, we offer a comprehensive overview of the survey results for

CEE countries and how they compare with findings of previous international studies. Finally, in Section 5,

we offer some concluding remarks.

2. Prior studies on capital budgeting practices: a brief overview

Over the past four decades, numerous capital budgeting surveys have been conducted to confront corpo-

rate finance theory with practice by financial managers. The following includes a summary of major studies on

capital budgeting practices around the world.

Graham and Harvey (2001) conduct a comprehensive field study on the practice of corporate finance. They

survey financial executives who are members of the Financial Executives Institute (FEI) and have held policy-

making positions as CFOs, treasurers, and controllers in 8000 companies throughout the USA and Canada.

They sent questionnaires to 4440 FEI members (including 313 CFOs of Fortune 500 companies). They received

392 completed questionnaires with a response rate of nearly 9%. Approximately 67% of the responding firms

were publicly traded and about half of them had sales greater than 500 million USD. In later years, Graham

et al.(2005) surveyed 401 U.S.financial executives on corporate financial reporting,Brav et al.(2005)

surveyed 384 financialexecutives to determine the factors that drive dividend and share repurchase

decisions, and more recently Graham et al. (2010) surveyed more than 1000 CEOs and CFOs to understand

how capital is allocated and decision-making authority is delegated within firms.

Another study includes Bennouna et al.(2010) who conducted a mail survey in Canada.The survey

population included the 500 largest firms that were listed in the Financial Post magazine.Their sample

contained 88 firms with a response rate of 18.4%. The sales revenues of the sample firms varied from 1000

to 1999 million Canadian dollars.

Brounen et al. (2004) chose 6000 firms in the U.K., Germany, and France and 500 firms in the Netherlands

for a total of 6500 firms. These firms were publicly traded as well as privately held. Their sample firms includ-

ed demographic data about the CFOs from the Amadeus data sets. The response rate for their survey was only

5% (313 responses), which is quite low compared to other surveys. Only 30% of the responding firms were

publicly listed and about half of the responding firms had sales more than 100 million Euros.

Hermes et al.(2007) conducted a survey on China and the Netherlands that mostly focused on listed

companies. They received 42 responses from Dutch firms of which 69% were publicly traded firms, while

93% of Chinese responding firms were publicly traded ones. Almost half of the Dutch firms had sales more

151G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and Africa). Consistent with findings of previous studies (e.g., La Porta et al. (1997,

1998, 2000), Hermes et al. (2007), and Maquieira et al. (2012)), we report significant variations in capital

budgeting practices across geographic regions and levels of economic development.4

The paper is organized as follows.In the next section, we provide a brief overview of prior studies on

capital budgeting practices. In Section 3, we present our methodology and describe our data set, sample de-

sign, and collection procedure. In Section 4, we offer a comprehensive overview of the survey results for

CEE countries and how they compare with findings of previous international studies. Finally, in Section 5,

we offer some concluding remarks.

2. Prior studies on capital budgeting practices: a brief overview

Over the past four decades, numerous capital budgeting surveys have been conducted to confront corpo-

rate finance theory with practice by financial managers. The following includes a summary of major studies on

capital budgeting practices around the world.

Graham and Harvey (2001) conduct a comprehensive field study on the practice of corporate finance. They

survey financial executives who are members of the Financial Executives Institute (FEI) and have held policy-

making positions as CFOs, treasurers, and controllers in 8000 companies throughout the USA and Canada.

They sent questionnaires to 4440 FEI members (including 313 CFOs of Fortune 500 companies). They received

392 completed questionnaires with a response rate of nearly 9%. Approximately 67% of the responding firms

were publicly traded and about half of them had sales greater than 500 million USD. In later years, Graham

et al.(2005) surveyed 401 U.S.financial executives on corporate financial reporting,Brav et al.(2005)

surveyed 384 financialexecutives to determine the factors that drive dividend and share repurchase

decisions, and more recently Graham et al. (2010) surveyed more than 1000 CEOs and CFOs to understand

how capital is allocated and decision-making authority is delegated within firms.

Another study includes Bennouna et al.(2010) who conducted a mail survey in Canada.The survey

population included the 500 largest firms that were listed in the Financial Post magazine.Their sample

contained 88 firms with a response rate of 18.4%. The sales revenues of the sample firms varied from 1000

to 1999 million Canadian dollars.

Brounen et al. (2004) chose 6000 firms in the U.K., Germany, and France and 500 firms in the Netherlands

for a total of 6500 firms. These firms were publicly traded as well as privately held. Their sample firms includ-

ed demographic data about the CFOs from the Amadeus data sets. The response rate for their survey was only

5% (313 responses), which is quite low compared to other surveys. Only 30% of the responding firms were

publicly listed and about half of the responding firms had sales more than 100 million Euros.

Hermes et al.(2007) conducted a survey on China and the Netherlands that mostly focused on listed

companies. They received 42 responses from Dutch firms of which 69% were publicly traded firms, while

93% of Chinese responding firms were publicly traded ones. Almost half of the Dutch firms had sales more

151G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

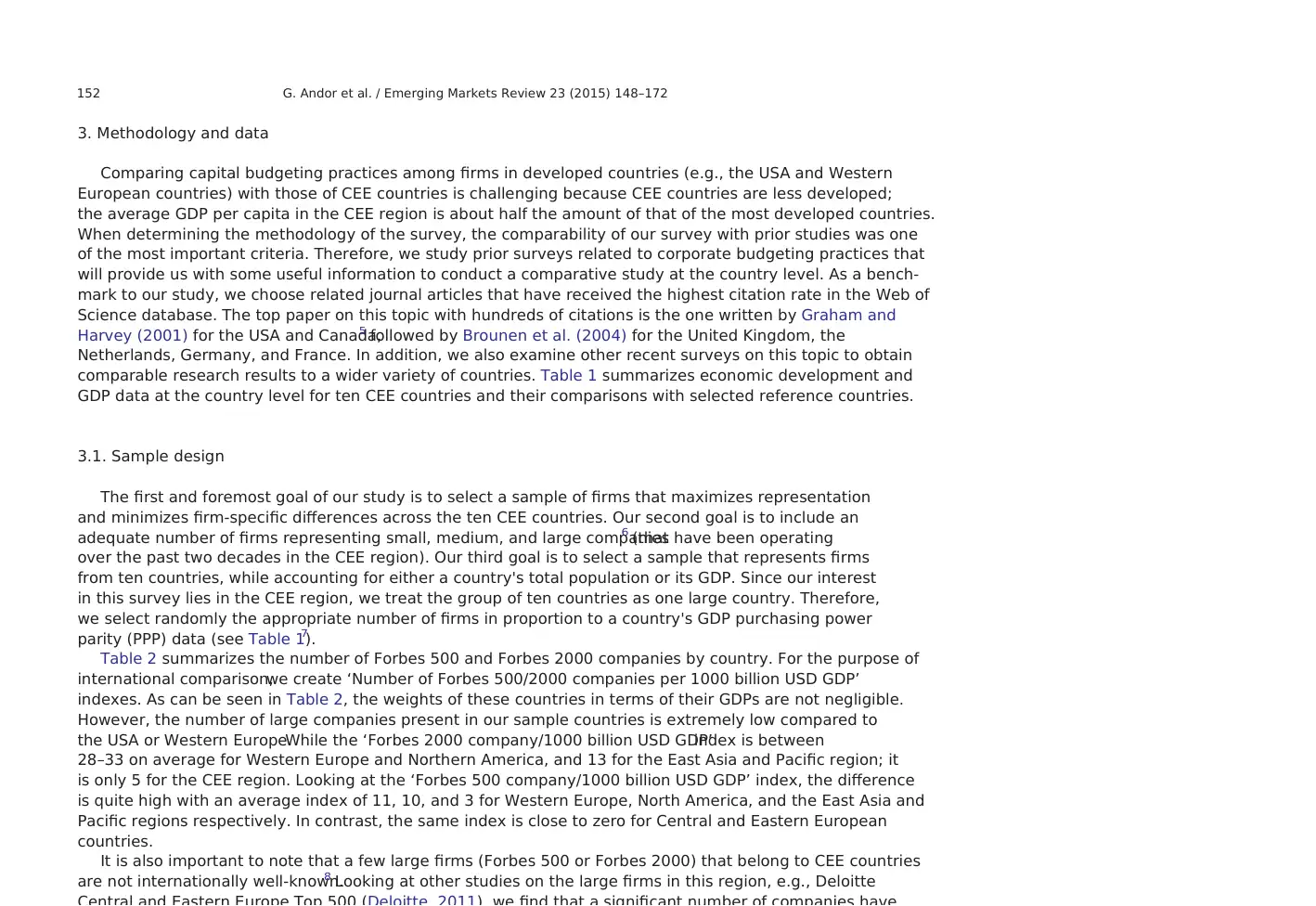

3. Methodology and data

Comparing capital budgeting practices among firms in developed countries (e.g., the USA and Western

European countries) with those of CEE countries is challenging because CEE countries are less developed;

the average GDP per capita in the CEE region is about half the amount of that of the most developed countries.

When determining the methodology of the survey, the comparability of our survey with prior studies was one

of the most important criteria. Therefore, we study prior surveys related to corporate budgeting practices that

will provide us with some useful information to conduct a comparative study at the country level. As a bench-

mark to our study, we choose related journal articles that have received the highest citation rate in the Web of

Science database. The top paper on this topic with hundreds of citations is the one written by Graham and

Harvey (2001) for the USA and Canada,5 followed by Brounen et al. (2004) for the United Kingdom, the

Netherlands, Germany, and France. In addition, we also examine other recent surveys on this topic to obtain

comparable research results to a wider variety of countries. Table 1 summarizes economic development and

GDP data at the country level for ten CEE countries and their comparisons with selected reference countries.

3.1. Sample design

The first and foremost goal of our study is to select a sample of firms that maximizes representation

and minimizes firm-specific differences across the ten CEE countries. Our second goal is to include an

adequate number of firms representing small, medium, and large companies6 (that have been operating

over the past two decades in the CEE region). Our third goal is to select a sample that represents firms

from ten countries, while accounting for either a country's total population or its GDP. Since our interest

in this survey lies in the CEE region, we treat the group of ten countries as one large country. Therefore,

we select randomly the appropriate number of firms in proportion to a country's GDP purchasing power

parity (PPP) data (see Table 1).7

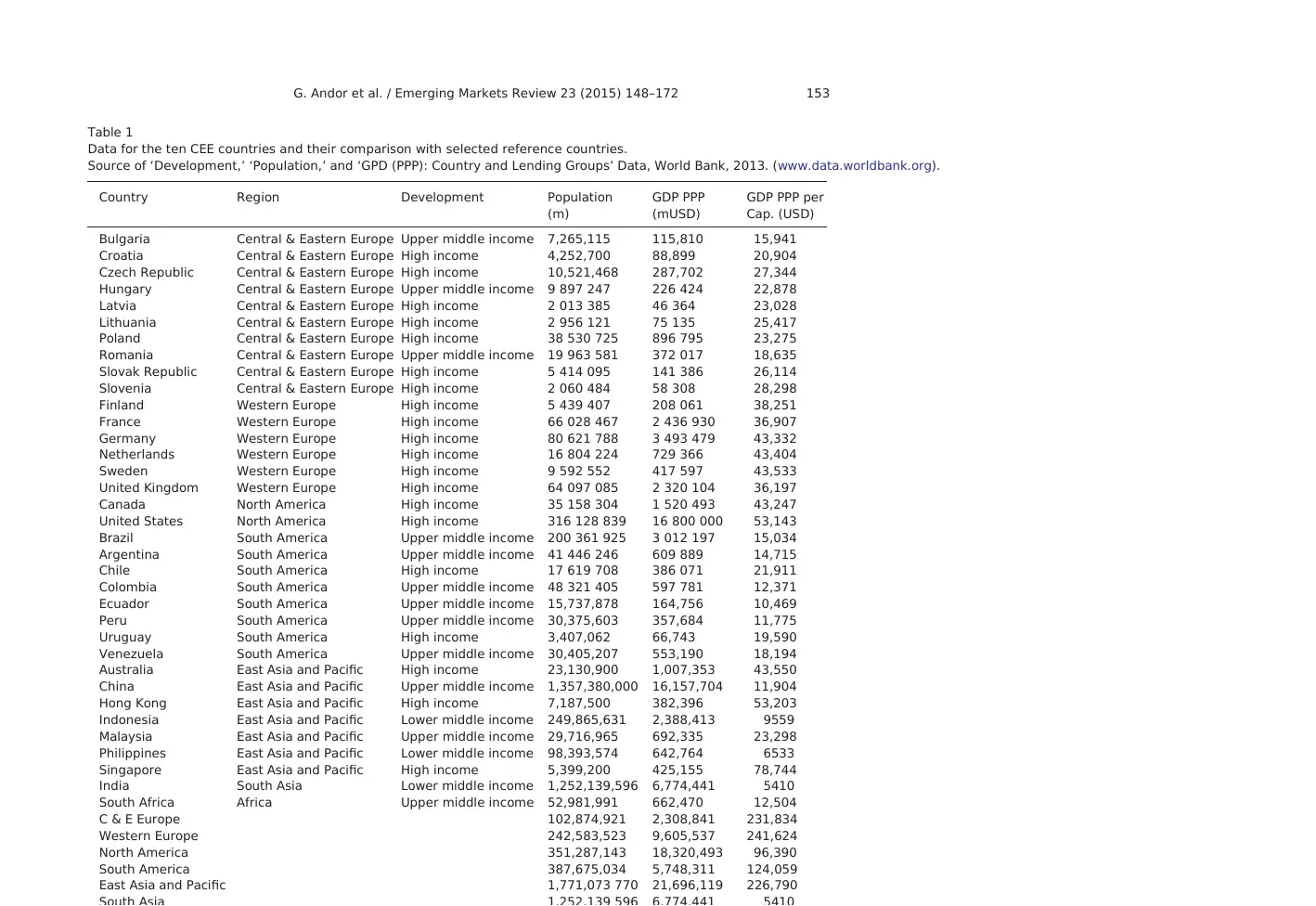

Table 2 summarizes the number of Forbes 500 and Forbes 2000 companies by country. For the purpose of

international comparison,we create ‘Number of Forbes 500/2000 companies per 1000 billion USD GDP’

indexes. As can be seen in Table 2, the weights of these countries in terms of their GDPs are not negligible.

However, the number of large companies present in our sample countries is extremely low compared to

the USA or Western Europe.While the ‘Forbes 2000 company/1000 billion USD GDP’index is between

28–33 on average for Western Europe and Northern America, and 13 for the East Asia and Pacific region; it

is only 5 for the CEE region. Looking at the ‘Forbes 500 company/1000 billion USD GDP’ index, the difference

is quite high with an average index of 11, 10, and 3 for Western Europe, North America, and the East Asia and

Pacific regions respectively. In contrast, the same index is close to zero for Central and Eastern European

countries.

It is also important to note that a few large firms (Forbes 500 or Forbes 2000) that belong to CEE countries

are not internationally well-known.8 Looking at other studies on the large firms in this region, e.g., Deloitte

152 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Comparing capital budgeting practices among firms in developed countries (e.g., the USA and Western

European countries) with those of CEE countries is challenging because CEE countries are less developed;

the average GDP per capita in the CEE region is about half the amount of that of the most developed countries.

When determining the methodology of the survey, the comparability of our survey with prior studies was one

of the most important criteria. Therefore, we study prior surveys related to corporate budgeting practices that

will provide us with some useful information to conduct a comparative study at the country level. As a bench-

mark to our study, we choose related journal articles that have received the highest citation rate in the Web of

Science database. The top paper on this topic with hundreds of citations is the one written by Graham and

Harvey (2001) for the USA and Canada,5 followed by Brounen et al. (2004) for the United Kingdom, the

Netherlands, Germany, and France. In addition, we also examine other recent surveys on this topic to obtain

comparable research results to a wider variety of countries. Table 1 summarizes economic development and

GDP data at the country level for ten CEE countries and their comparisons with selected reference countries.

3.1. Sample design

The first and foremost goal of our study is to select a sample of firms that maximizes representation

and minimizes firm-specific differences across the ten CEE countries. Our second goal is to include an

adequate number of firms representing small, medium, and large companies6 (that have been operating

over the past two decades in the CEE region). Our third goal is to select a sample that represents firms

from ten countries, while accounting for either a country's total population or its GDP. Since our interest

in this survey lies in the CEE region, we treat the group of ten countries as one large country. Therefore,

we select randomly the appropriate number of firms in proportion to a country's GDP purchasing power

parity (PPP) data (see Table 1).7

Table 2 summarizes the number of Forbes 500 and Forbes 2000 companies by country. For the purpose of

international comparison,we create ‘Number of Forbes 500/2000 companies per 1000 billion USD GDP’

indexes. As can be seen in Table 2, the weights of these countries in terms of their GDPs are not negligible.

However, the number of large companies present in our sample countries is extremely low compared to

the USA or Western Europe.While the ‘Forbes 2000 company/1000 billion USD GDP’index is between

28–33 on average for Western Europe and Northern America, and 13 for the East Asia and Pacific region; it

is only 5 for the CEE region. Looking at the ‘Forbes 500 company/1000 billion USD GDP’ index, the difference

is quite high with an average index of 11, 10, and 3 for Western Europe, North America, and the East Asia and

Pacific regions respectively. In contrast, the same index is close to zero for Central and Eastern European

countries.

It is also important to note that a few large firms (Forbes 500 or Forbes 2000) that belong to CEE countries

are not internationally well-known.8 Looking at other studies on the large firms in this region, e.g., Deloitte

152 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Table 1

Data for the ten CEE countries and their comparison with selected reference countries.

Source of ‘Development,’ ‘Population,’ and ‘GPD (PPP): Country and Lending Groups’ Data, World Bank, 2013. (www.data.worldbank.org).

Country Region Development Population

(m)

GDP PPP

(mUSD)

GDP PPP per

Cap. (USD)

Bulgaria Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 7,265,115 115,810 15,941

Croatia Central & Eastern Europe High income 4,252,700 88,899 20,904

Czech Republic Central & Eastern Europe High income 10,521,468 287,702 27,344

Hungary Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 9 897 247 226 424 22,878

Latvia Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 013 385 46 364 23,028

Lithuania Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 956 121 75 135 25,417

Poland Central & Eastern Europe High income 38 530 725 896 795 23,275

Romania Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 19 963 581 372 017 18,635

Slovak Republic Central & Eastern Europe High income 5 414 095 141 386 26,114

Slovenia Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 060 484 58 308 28,298

Finland Western Europe High income 5 439 407 208 061 38,251

France Western Europe High income 66 028 467 2 436 930 36,907

Germany Western Europe High income 80 621 788 3 493 479 43,332

Netherlands Western Europe High income 16 804 224 729 366 43,404

Sweden Western Europe High income 9 592 552 417 597 43,533

United Kingdom Western Europe High income 64 097 085 2 320 104 36,197

Canada North America High income 35 158 304 1 520 493 43,247

United States North America High income 316 128 839 16 800 000 53,143

Brazil South America Upper middle income 200 361 925 3 012 197 15,034

Argentina South America Upper middle income 41 446 246 609 889 14,715

Chile South America High income 17 619 708 386 071 21,911

Colombia South America Upper middle income 48 321 405 597 781 12,371

Ecuador South America Upper middle income 15,737,878 164,756 10,469

Peru South America Upper middle income 30,375,603 357,684 11,775

Uruguay South America High income 3,407,062 66,743 19,590

Venezuela South America Upper middle income 30,405,207 553,190 18,194

Australia East Asia and Pacific High income 23,130,900 1,007,353 43,550

China East Asia and Pacific Upper middle income 1,357,380,000 16,157,704 11,904

Hong Kong East Asia and Pacific High income 7,187,500 382,396 53,203

Indonesia East Asia and Pacific Lower middle income 249,865,631 2,388,413 9559

Malaysia East Asia and Pacific Upper middle income 29,716,965 692,335 23,298

Philippines East Asia and Pacific Lower middle income 98,393,574 642,764 6533

Singapore East Asia and Pacific High income 5,399,200 425,155 78,744

India South Asia Lower middle income 1,252,139,596 6,774,441 5410

South Africa Africa Upper middle income 52,981,991 662,470 12,504

C & E Europe 102,874,921 2,308,841 231,834

Western Europe 242,583,523 9,605,537 241,624

North America 351,287,143 18,320,493 96,390

South America 387,675,034 5,748,311 124,059

East Asia and Pacific 1,771,073 770 21,696,119 226,790

153G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Data for the ten CEE countries and their comparison with selected reference countries.

Source of ‘Development,’ ‘Population,’ and ‘GPD (PPP): Country and Lending Groups’ Data, World Bank, 2013. (www.data.worldbank.org).

Country Region Development Population

(m)

GDP PPP

(mUSD)

GDP PPP per

Cap. (USD)

Bulgaria Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 7,265,115 115,810 15,941

Croatia Central & Eastern Europe High income 4,252,700 88,899 20,904

Czech Republic Central & Eastern Europe High income 10,521,468 287,702 27,344

Hungary Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 9 897 247 226 424 22,878

Latvia Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 013 385 46 364 23,028

Lithuania Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 956 121 75 135 25,417

Poland Central & Eastern Europe High income 38 530 725 896 795 23,275

Romania Central & Eastern Europe Upper middle income 19 963 581 372 017 18,635

Slovak Republic Central & Eastern Europe High income 5 414 095 141 386 26,114

Slovenia Central & Eastern Europe High income 2 060 484 58 308 28,298

Finland Western Europe High income 5 439 407 208 061 38,251

France Western Europe High income 66 028 467 2 436 930 36,907

Germany Western Europe High income 80 621 788 3 493 479 43,332

Netherlands Western Europe High income 16 804 224 729 366 43,404

Sweden Western Europe High income 9 592 552 417 597 43,533

United Kingdom Western Europe High income 64 097 085 2 320 104 36,197

Canada North America High income 35 158 304 1 520 493 43,247

United States North America High income 316 128 839 16 800 000 53,143

Brazil South America Upper middle income 200 361 925 3 012 197 15,034

Argentina South America Upper middle income 41 446 246 609 889 14,715

Chile South America High income 17 619 708 386 071 21,911

Colombia South America Upper middle income 48 321 405 597 781 12,371

Ecuador South America Upper middle income 15,737,878 164,756 10,469

Peru South America Upper middle income 30,375,603 357,684 11,775

Uruguay South America High income 3,407,062 66,743 19,590

Venezuela South America Upper middle income 30,405,207 553,190 18,194

Australia East Asia and Pacific High income 23,130,900 1,007,353 43,550

China East Asia and Pacific Upper middle income 1,357,380,000 16,157,704 11,904

Hong Kong East Asia and Pacific High income 7,187,500 382,396 53,203

Indonesia East Asia and Pacific Lower middle income 249,865,631 2,388,413 9559

Malaysia East Asia and Pacific Upper middle income 29,716,965 692,335 23,298

Philippines East Asia and Pacific Lower middle income 98,393,574 642,764 6533

Singapore East Asia and Pacific High income 5,399,200 425,155 78,744

India South Asia Lower middle income 1,252,139,596 6,774,441 5410

South Africa Africa Upper middle income 52,981,991 662,470 12,504

C & E Europe 102,874,921 2,308,841 231,834

Western Europe 242,583,523 9,605,537 241,624

North America 351,287,143 18,320,493 96,390

South America 387,675,034 5,748,311 124,059

East Asia and Pacific 1,771,073 770 21,696,119 226,790

153G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 2

Forbes 500 and Forbes 2000 companies in the CEE countries and in the selected reference countries.

Source of ‘Forbes 500 company’ and ‘Forbes 2000 company’: Forbes.com, Business, ‘The World's Leading Companies’, Global 500, Global

2000, (www.forbes.com).

Country Region Forbes 500

company

Forbes 500

company/1000

billion USD GDP

Forbes 2000

company

Forbes 2000

company/1000

billion USD GDP

Bulgaria Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Croatia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Czech Republic Central & Eastern Europe 1 3 1 3

Hungary Central & Eastern Europe – – 2 9

Latvia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Lithuania Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Poland Central & Eastern Europe – – 8 9

Romania Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Slovak Republic Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Slovenia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Finland Western Europe 2 10 12 58

France Western Europe 27 11 64 26

Germany Western Europe 23 7 50 14

Netherlands Western Europe 10 14 24 33

Sweden Western Europe 9 22 26 62

United Kingdom Western Europe 30 13 95 41

Canada North America 23 15 65 43

United States North America 159 9 543 32

Brazil South America 6 2 31 10

Argentina South America – – – –

Chile South America – – 9 23

Colombia South America 1 2 6 10

Ecuador South America – – – –

Peru South America – – 2 6

Uruguay South America – – – –

Venezuela South America – – 1 2

Australia East Asia and Pacific 14 14 42 42

China East Asia and Pacific 31 2 136 8

Hong Kong East Asia and Pacific 8 21 46 120

Indonesia East Asia and Pacific 2 1 9 4

Malaysia East Asia and Pacific 2 3 20 29

Philippines East Asia and Pacific – – 8 12

Singapore East Asia and Pacific 6 14 20 47

India South Asia 10 1 56 8

South Africa Africa 4 6 19 29

C & E Europe 1 0 11 5

Western Europe 101 11 271 28

North America 182 10 608 33

154 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Forbes 500 and Forbes 2000 companies in the CEE countries and in the selected reference countries.

Source of ‘Forbes 500 company’ and ‘Forbes 2000 company’: Forbes.com, Business, ‘The World's Leading Companies’, Global 500, Global

2000, (www.forbes.com).

Country Region Forbes 500

company

Forbes 500

company/1000

billion USD GDP

Forbes 2000

company

Forbes 2000

company/1000

billion USD GDP

Bulgaria Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Croatia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Czech Republic Central & Eastern Europe 1 3 1 3

Hungary Central & Eastern Europe – – 2 9

Latvia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Lithuania Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Poland Central & Eastern Europe – – 8 9

Romania Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Slovak Republic Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Slovenia Central & Eastern Europe – – – –

Finland Western Europe 2 10 12 58

France Western Europe 27 11 64 26

Germany Western Europe 23 7 50 14

Netherlands Western Europe 10 14 24 33

Sweden Western Europe 9 22 26 62

United Kingdom Western Europe 30 13 95 41

Canada North America 23 15 65 43

United States North America 159 9 543 32

Brazil South America 6 2 31 10

Argentina South America – – – –

Chile South America – – 9 23

Colombia South America 1 2 6 10

Ecuador South America – – – –

Peru South America – – 2 6

Uruguay South America – – – –

Venezuela South America – – 1 2

Australia East Asia and Pacific 14 14 42 42

China East Asia and Pacific 31 2 136 8

Hong Kong East Asia and Pacific 8 21 46 120

Indonesia East Asia and Pacific 2 1 9 4

Malaysia East Asia and Pacific 2 3 20 29

Philippines East Asia and Pacific – – 8 12

Singapore East Asia and Pacific 6 14 20 47

India South Asia 10 1 56 8

South Africa Africa 4 6 19 29

C & E Europe 1 0 11 5

Western Europe 101 11 271 28

North America 182 10 608 33

154 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

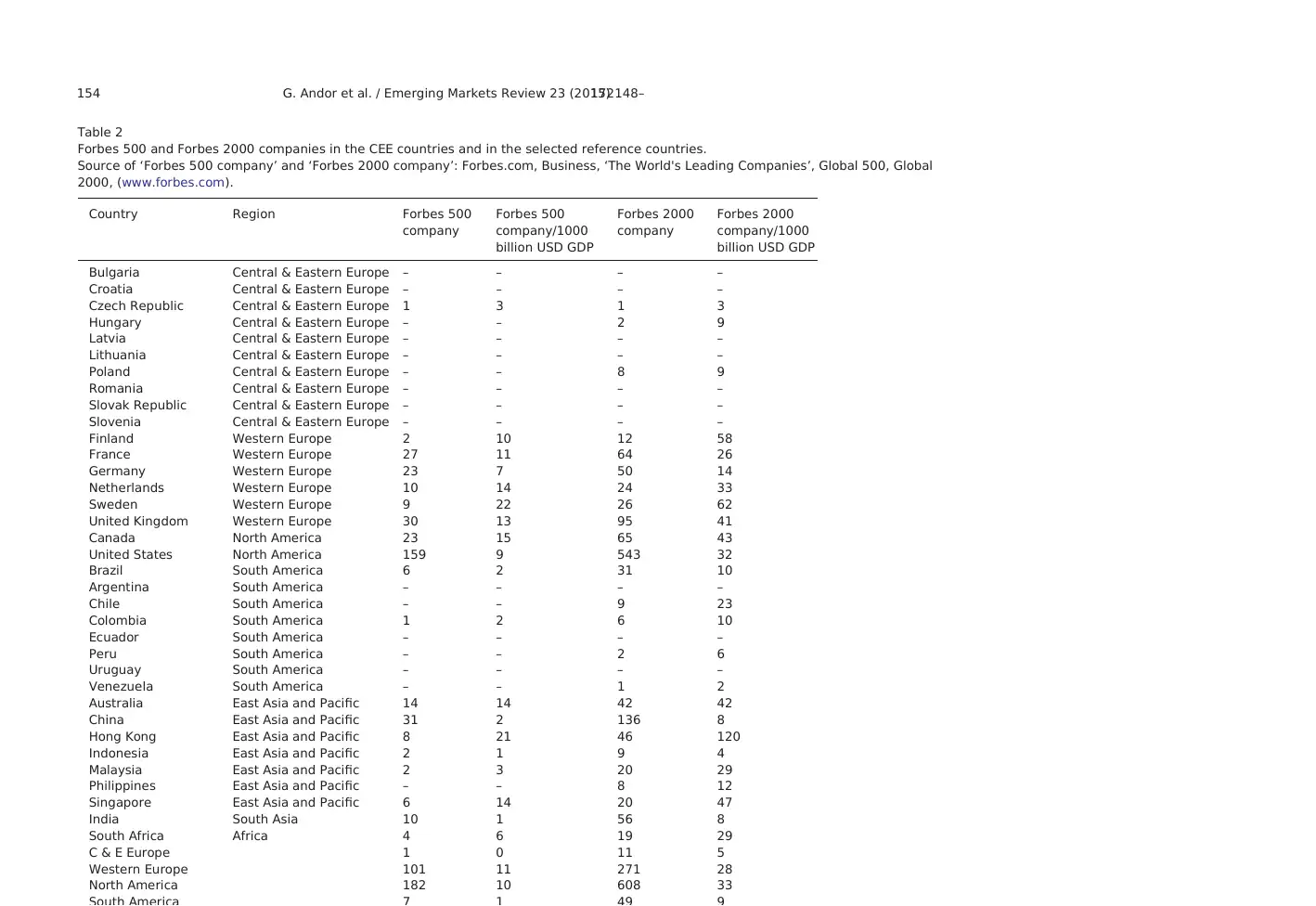

Table 3

Design and selection of sample firms from CEE countries.

Country Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Romania Slovakia Slovenia Total

Number of firms in the data set 4434 3676 13,467 2682 2359 3533 16,055 18,547 3242 1918 69,913

1st population (25–50 employees) 1706 138 5174 968 794 1242 372 8864 888 663 25,399

Responses from the 1st population 2 2 6 4 1 1 14 6 3 1 40

Responses with formal analysis

from 1st population

0 2 2 4 0 1 11 3 3 0 26

2nd population (51–250 employees) 1721 1841 6759 1252 1294 1979 9034 8174 1888 949 34,891

Responses from the 2nd population 3 2 8 7 2 2 21 9 4 2 60

Responses with formal analysis from

2nd population

3 3 6 7 2 1 19 7 2 0 50

3rd population (251–375 employees) 334 152 511 156 91 104 1101 503 155 102 3209

4th population (376–650 employees) 339 152 511 155 90 104 1100 503 156 102 3212

5th population (650 employees) 335 152 511 151 90 104 1100 503 155 102 3203

Responses from the 3rd, 4th, and 5th pop.5–5–5 4–4–4 15–14–14 12–12–11 2–2–2 4–3–4 36–36–36 14–14–14 6–6–6 3–3–4 300

Responses with formal analysis

from 3rd, 4th, and 5th

5 11 28 32 4 10 105 36 16 10 257

Total responses 20 16 57 46 9 14 143 57 25 13 400

Responses with formal analysis 8 16 36 43 6 12 135 46 21 10 333

155G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Design and selection of sample firms from CEE countries.

Country Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Romania Slovakia Slovenia Total

Number of firms in the data set 4434 3676 13,467 2682 2359 3533 16,055 18,547 3242 1918 69,913

1st population (25–50 employees) 1706 138 5174 968 794 1242 372 8864 888 663 25,399

Responses from the 1st population 2 2 6 4 1 1 14 6 3 1 40

Responses with formal analysis

from 1st population

0 2 2 4 0 1 11 3 3 0 26

2nd population (51–250 employees) 1721 1841 6759 1252 1294 1979 9034 8174 1888 949 34,891

Responses from the 2nd population 3 2 8 7 2 2 21 9 4 2 60

Responses with formal analysis from

2nd population

3 3 6 7 2 1 19 7 2 0 50

3rd population (251–375 employees) 334 152 511 156 91 104 1101 503 155 102 3209

4th population (376–650 employees) 339 152 511 155 90 104 1100 503 156 102 3212

5th population (650 employees) 335 152 511 151 90 104 1100 503 155 102 3203

Responses from the 3rd, 4th, and 5th pop.5–5–5 4–4–4 15–14–14 12–12–11 2–2–2 4–3–4 36–36–36 14–14–14 6–6–6 3–3–4 300

Responses with formal analysis

from 3rd, 4th, and 5th

5 11 28 32 4 10 105 36 16 10 257

Total responses 20 16 57 46 9 14 143 57 25 13 400

Responses with formal analysis 8 16 36 43 6 12 135 46 21 10 333

155G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

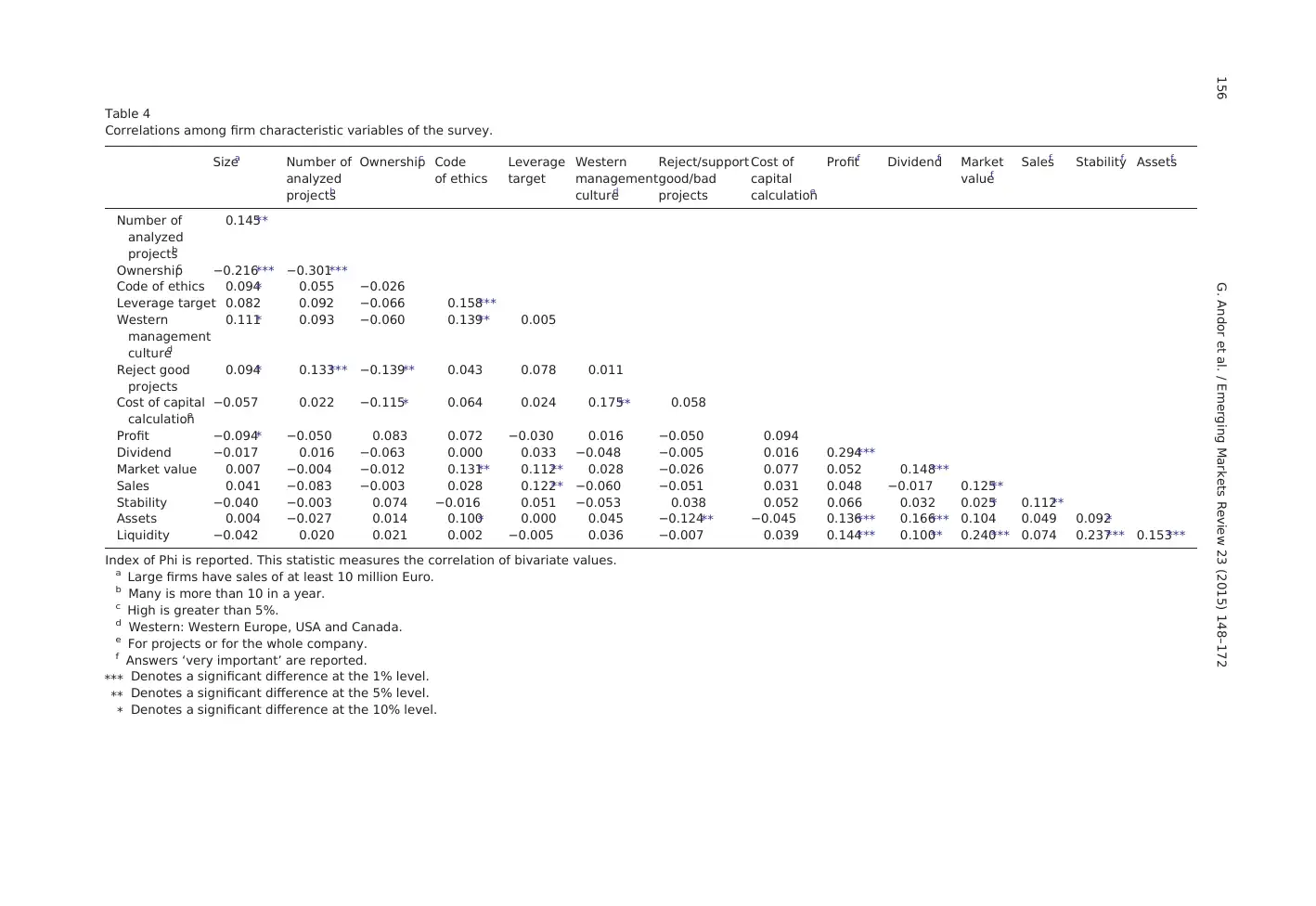

Table 4

Correlations among firm characteristic variables of the survey.

Sizea Number of

analyzed

projectsb

Ownershipc Code

of ethics

Leverage

target

Western

management

cultured

Reject/support

good/bad

projects

Cost of

capital

calculatione

Profitf Dividendf Market

valuef

Salesf Stabilityf Assetsf

Number of

analyzed

projectsb

0.145⁎⁎

Ownershipc −0.216⁎⁎⁎ −0.301⁎⁎⁎

Code of ethics 0.094⁎ 0.055 −0.026

Leverage target 0.082 0.092 −0.066 0.158⁎⁎⁎

Western

management

cultured

0.111⁎ 0.093 −0.060 0.139⁎⁎ 0.005

Reject good

projects

0.094⁎ 0.133⁎⁎⁎ −0.139⁎⁎ 0.043 0.078 0.011

Cost of capital

calculatione

−0.057 0.022 −0.115⁎ 0.064 0.024 0.175⁎⁎ 0.058

Profit −0.094⁎ −0.050 0.083 0.072 −0.030 0.016 −0.050 0.094

Dividend −0.017 0.016 −0.063 0.000 0.033 −0.048 −0.005 0.016 0.294⁎⁎⁎

Market value 0.007 −0.004 −0.012 0.131⁎⁎ 0.112⁎⁎ 0.028 −0.026 0.077 0.052 0.148⁎⁎⁎

Sales 0.041 −0.083 −0.003 0.028 0.122⁎⁎ −0.060 −0.051 0.031 0.048 −0.017 0.125⁎⁎

Stability −0.040 −0.003 0.074 −0.016 0.051 −0.053 0.038 0.052 0.066 0.032 0.025⁎ 0.112⁎⁎

Assets 0.004 −0.027 0.014 0.100⁎ 0.000 0.045 −0.124⁎⁎ −0.045 0.136⁎⁎⁎ 0.166⁎⁎⁎ 0.104 0.049 0.092⁎

Liquidity −0.042 0.020 0.021 0.002 −0.005 0.036 −0.007 0.039 0.144⁎⁎⁎ 0.100⁎⁎ 0.240⁎⁎⁎ 0.074 0.237⁎⁎⁎ 0.153⁎⁎⁎

Index of Phi is reported. This statistic measures the correlation of bivariate values.

a Large firms have sales of at least 10 million Euro.

b Many is more than 10 in a year.

c High is greater than 5%.

d Western: Western Europe, USA and Canada.

e For projects or for the whole company.

f Answers ‘very important’ are reported.

⁎⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 1% level.

⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 5% level.

⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 10% level.

156 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Correlations among firm characteristic variables of the survey.

Sizea Number of

analyzed

projectsb

Ownershipc Code

of ethics

Leverage

target

Western

management

cultured

Reject/support

good/bad

projects

Cost of

capital

calculatione

Profitf Dividendf Market

valuef

Salesf Stabilityf Assetsf

Number of

analyzed

projectsb

0.145⁎⁎

Ownershipc −0.216⁎⁎⁎ −0.301⁎⁎⁎

Code of ethics 0.094⁎ 0.055 −0.026

Leverage target 0.082 0.092 −0.066 0.158⁎⁎⁎

Western

management

cultured

0.111⁎ 0.093 −0.060 0.139⁎⁎ 0.005

Reject good

projects

0.094⁎ 0.133⁎⁎⁎ −0.139⁎⁎ 0.043 0.078 0.011

Cost of capital

calculatione

−0.057 0.022 −0.115⁎ 0.064 0.024 0.175⁎⁎ 0.058

Profit −0.094⁎ −0.050 0.083 0.072 −0.030 0.016 −0.050 0.094

Dividend −0.017 0.016 −0.063 0.000 0.033 −0.048 −0.005 0.016 0.294⁎⁎⁎

Market value 0.007 −0.004 −0.012 0.131⁎⁎ 0.112⁎⁎ 0.028 −0.026 0.077 0.052 0.148⁎⁎⁎

Sales 0.041 −0.083 −0.003 0.028 0.122⁎⁎ −0.060 −0.051 0.031 0.048 −0.017 0.125⁎⁎

Stability −0.040 −0.003 0.074 −0.016 0.051 −0.053 0.038 0.052 0.066 0.032 0.025⁎ 0.112⁎⁎

Assets 0.004 −0.027 0.014 0.100⁎ 0.000 0.045 −0.124⁎⁎ −0.045 0.136⁎⁎⁎ 0.166⁎⁎⁎ 0.104 0.049 0.092⁎

Liquidity −0.042 0.020 0.021 0.002 −0.005 0.036 −0.007 0.039 0.144⁎⁎⁎ 0.100⁎⁎ 0.240⁎⁎⁎ 0.074 0.237⁎⁎⁎ 0.153⁎⁎⁎

Index of Phi is reported. This statistic measures the correlation of bivariate values.

a Large firms have sales of at least 10 million Euro.

b Many is more than 10 in a year.

c High is greater than 5%.

d Western: Western Europe, USA and Canada.

e For projects or for the whole company.

f Answers ‘very important’ are reported.

⁎⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 1% level.

⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 5% level.

⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 10% level.

156 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of employees between 251 and 375 belong to the 3rd population, large firms with number of employees be-

tween 376 to 650 belong to the 4th, and large firms with number of employees over 650 are put into the 5th

population. We drop the firms with missing data. As a result, we lose about 10% of the total firms from the data

set. However, the number of firms included in each population is at least ten times larger than the expected

response numbers. Finally, we include only those firms that conduct formal capital budgeting analysis.

The number of expected responses for each population is determined in advance. Our goal is to collect 400

usable responses that represent small, medium, and large firms from each of the ten CEE countries. We choose

10% of the total responses from the first population, 15% from the second population, and 25% from each of the

third, fourth, and fifth populations. This implies that our sample consists of 100 responses (that is, 25%) from

smaller companies and 300 (that is, 75%) from larger companies — considering the typical company size for

this region. Table 3 reports the population and expected number of responses from each of the five popula-

tions for each country. A separate row in Table 3 shows the number of respondent firms from each of the

ten countries. For example, the largest number of firms represented in our sample is drawn from Poland

(143 firms), while the smallest number of firms is drawn from Latvia (9 firms).

3.2. Delivery and response

Following Graham and Harvey's (2001) survey, we initially developed our questionnaires in English and

then have them translated into ten languages. This process has raised some challenging issues here. Although

these countries have relatively small populations and are located in close proximity to each other, languages

spoken in the CEE region vary significantly across countries. Moreover, there is no common spoken language

in the CEE region even though the knowledge of English has become increasingly important over the past de-

cade. Given the low level of proficiency and comprehension of the English language among native people in

this region, we do not use an English form of the questionnaire. Instead, we develop questionnaires in ten

native languages for each country in the CEE region. However, when we translate the questionnaires we

face several other challenges. First, even though business managers from CEE countries are more likely to

be familiar with modern corporate finance literature in terms of their local language, they are less likely to

be familiar with the terminology written in the English language. Second, business managers may use special

words in their local language as the equivalent to a given English term. Third, there have been large gaps

between newly developed academic jargons and everyday slangs used by local managers in these countries.

To overcome such challenges encountered in translating the survey questionnaires, we conduct a phone

survey in the respondents' native languages instead of conducting mail surveys. Oral interviews provide us

the opportunity to interact with respondents and help them understand the terminology and special

meanings associated with corporate finance theory and practice.

Phone interviews were carried out during the 2007–2009 period with the assistance of a multinational

polling company that had a professional call center. Operators are native speakers of the local languages

and are trained on the corporate finance aspects of the survey by the authors of this study.For example,

prior to conducting any phone interviews, each caller had to take part in a special professional course present-

157G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

tween 376 to 650 belong to the 4th, and large firms with number of employees over 650 are put into the 5th

population. We drop the firms with missing data. As a result, we lose about 10% of the total firms from the data

set. However, the number of firms included in each population is at least ten times larger than the expected

response numbers. Finally, we include only those firms that conduct formal capital budgeting analysis.

The number of expected responses for each population is determined in advance. Our goal is to collect 400

usable responses that represent small, medium, and large firms from each of the ten CEE countries. We choose

10% of the total responses from the first population, 15% from the second population, and 25% from each of the

third, fourth, and fifth populations. This implies that our sample consists of 100 responses (that is, 25%) from

smaller companies and 300 (that is, 75%) from larger companies — considering the typical company size for

this region. Table 3 reports the population and expected number of responses from each of the five popula-

tions for each country. A separate row in Table 3 shows the number of respondent firms from each of the

ten countries. For example, the largest number of firms represented in our sample is drawn from Poland

(143 firms), while the smallest number of firms is drawn from Latvia (9 firms).

3.2. Delivery and response

Following Graham and Harvey's (2001) survey, we initially developed our questionnaires in English and

then have them translated into ten languages. This process has raised some challenging issues here. Although

these countries have relatively small populations and are located in close proximity to each other, languages

spoken in the CEE region vary significantly across countries. Moreover, there is no common spoken language

in the CEE region even though the knowledge of English has become increasingly important over the past de-

cade. Given the low level of proficiency and comprehension of the English language among native people in

this region, we do not use an English form of the questionnaire. Instead, we develop questionnaires in ten

native languages for each country in the CEE region. However, when we translate the questionnaires we

face several other challenges. First, even though business managers from CEE countries are more likely to

be familiar with modern corporate finance literature in terms of their local language, they are less likely to

be familiar with the terminology written in the English language. Second, business managers may use special

words in their local language as the equivalent to a given English term. Third, there have been large gaps

between newly developed academic jargons and everyday slangs used by local managers in these countries.

To overcome such challenges encountered in translating the survey questionnaires, we conduct a phone

survey in the respondents' native languages instead of conducting mail surveys. Oral interviews provide us

the opportunity to interact with respondents and help them understand the terminology and special

meanings associated with corporate finance theory and practice.

Phone interviews were carried out during the 2007–2009 period with the assistance of a multinational

polling company that had a professional call center. Operators are native speakers of the local languages

and are trained on the corporate finance aspects of the survey by the authors of this study.For example,

prior to conducting any phone interviews, each caller had to take part in a special professional course present-

157G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

details about capital budgeting practices are not asked at all, and we collect these questionnaires separately.

Our survey finds that 83% of the respondents (333 out of 400 sample firms) do make formal capital budgeting

analyses. It is surprising that some of the large firms in the CEE region make capital budgeting decisions with-

out making any formal written or quantitative analyses. These findings may be attributed to lack of availability

of reliable data.

4. Survey results

4.1. Correlation analysis of demographic variables

We use several binary dummy variables to describe sample firm characteristics. The variable used to mea-

sure the effect of firm size is ‘size.’ Size is equal to one (large) if a firm's sales revenue is greater than 10 million

Euros; otherwise it is zero (small). Based on this criterion, our survey shows that one-third of our sample firms

in CEE countries are ‘small’ and two-thirds of our sample firms are ‘large.’ The variable used to describe the

number of projects analyzed by a firm in a given year is ‘number of analyzed projects.’ Number of analyzed

projects is equal to one (many) if a firm analyzes more than ten projects in a year11; otherwise it is zero

(few). The variable used to measure the effect of executive ownership is ‘ownership.’ Ownership is equal to

one (high) if the management owns more than 5% of the company; otherwise it is zero (low). Firms respond

‘yes’ to the question related to code of ethics if they have written documents on ethical considerations.12‘Code

of ethics’ is equal to one (yes) if a firm adheres to a written code of ethics; otherwise it is zero (no). Similarly, if

the firm has a target financial leverage ratio, the variable ‘leverage target’ is equal to one (yes); otherwise it is

zero (no).13 The ‘Western management culture’ variable is used to measure the influence of Western manage-

ment culture on capital budgeting practices of CEE firms. Western management culture is equal to one (yes) if

the company reports a dominance of a foreign management culture that is rooted in Western culture such as

Western Europe, USA, or Canada14; otherwise it is zero. The variable ‘reject (support) bad (good) project’ is

designed to address other factors beyond formal capital budgeting analysis that may affect management

decisions on the rejection of a ‘good’ project or acceptance of a ‘bad’ project.15 Reject (support) bad (good)

project is equal to one (yes) if the firm rejects a good project or accepts a bad project; otherwise it is zero.

We also ask whether firms use a given value for cost of capital for all projects or different costs of capitals

for each project. The response to the ‘cost of capital calculation’ variable is ‘projects’ when the company

makes calculations for each project and ‘cost of capital calculation’ is ‘company’ when firms make only one

calculation for the entire firm and use this rate for all its projects.‘Cost of capital calculation’ variable is

equal to one (projects); otherwise it is zero (company).

Table 4 presents correlations among the demographic variables. The results show that large firms have a

lower proportion of management ownership, which is consistent with evidence reported in Graham and

Harvey (2001) study. Even though large companies operating in CEE countries are more likely to evaluate a

higher number of projects than small–medium firms, a number of good projects can be rejected by top man-

158 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Our survey finds that 83% of the respondents (333 out of 400 sample firms) do make formal capital budgeting

analyses. It is surprising that some of the large firms in the CEE region make capital budgeting decisions with-

out making any formal written or quantitative analyses. These findings may be attributed to lack of availability

of reliable data.

4. Survey results

4.1. Correlation analysis of demographic variables

We use several binary dummy variables to describe sample firm characteristics. The variable used to mea-

sure the effect of firm size is ‘size.’ Size is equal to one (large) if a firm's sales revenue is greater than 10 million

Euros; otherwise it is zero (small). Based on this criterion, our survey shows that one-third of our sample firms

in CEE countries are ‘small’ and two-thirds of our sample firms are ‘large.’ The variable used to describe the

number of projects analyzed by a firm in a given year is ‘number of analyzed projects.’ Number of analyzed

projects is equal to one (many) if a firm analyzes more than ten projects in a year11; otherwise it is zero

(few). The variable used to measure the effect of executive ownership is ‘ownership.’ Ownership is equal to

one (high) if the management owns more than 5% of the company; otherwise it is zero (low). Firms respond

‘yes’ to the question related to code of ethics if they have written documents on ethical considerations.12‘Code

of ethics’ is equal to one (yes) if a firm adheres to a written code of ethics; otherwise it is zero (no). Similarly, if

the firm has a target financial leverage ratio, the variable ‘leverage target’ is equal to one (yes); otherwise it is

zero (no).13 The ‘Western management culture’ variable is used to measure the influence of Western manage-

ment culture on capital budgeting practices of CEE firms. Western management culture is equal to one (yes) if

the company reports a dominance of a foreign management culture that is rooted in Western culture such as

Western Europe, USA, or Canada14; otherwise it is zero. The variable ‘reject (support) bad (good) project’ is

designed to address other factors beyond formal capital budgeting analysis that may affect management

decisions on the rejection of a ‘good’ project or acceptance of a ‘bad’ project.15 Reject (support) bad (good)

project is equal to one (yes) if the firm rejects a good project or accepts a bad project; otherwise it is zero.

We also ask whether firms use a given value for cost of capital for all projects or different costs of capitals

for each project. The response to the ‘cost of capital calculation’ variable is ‘projects’ when the company

makes calculations for each project and ‘cost of capital calculation’ is ‘company’ when firms make only one

calculation for the entire firm and use this rate for all its projects.‘Cost of capital calculation’ variable is

equal to one (projects); otherwise it is zero (company).

Table 4 presents correlations among the demographic variables. The results show that large firms have a

lower proportion of management ownership, which is consistent with evidence reported in Graham and

Harvey (2001) study. Even though large companies operating in CEE countries are more likely to evaluate a

higher number of projects than small–medium firms, a number of good projects can be rejected by top man-

158 G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

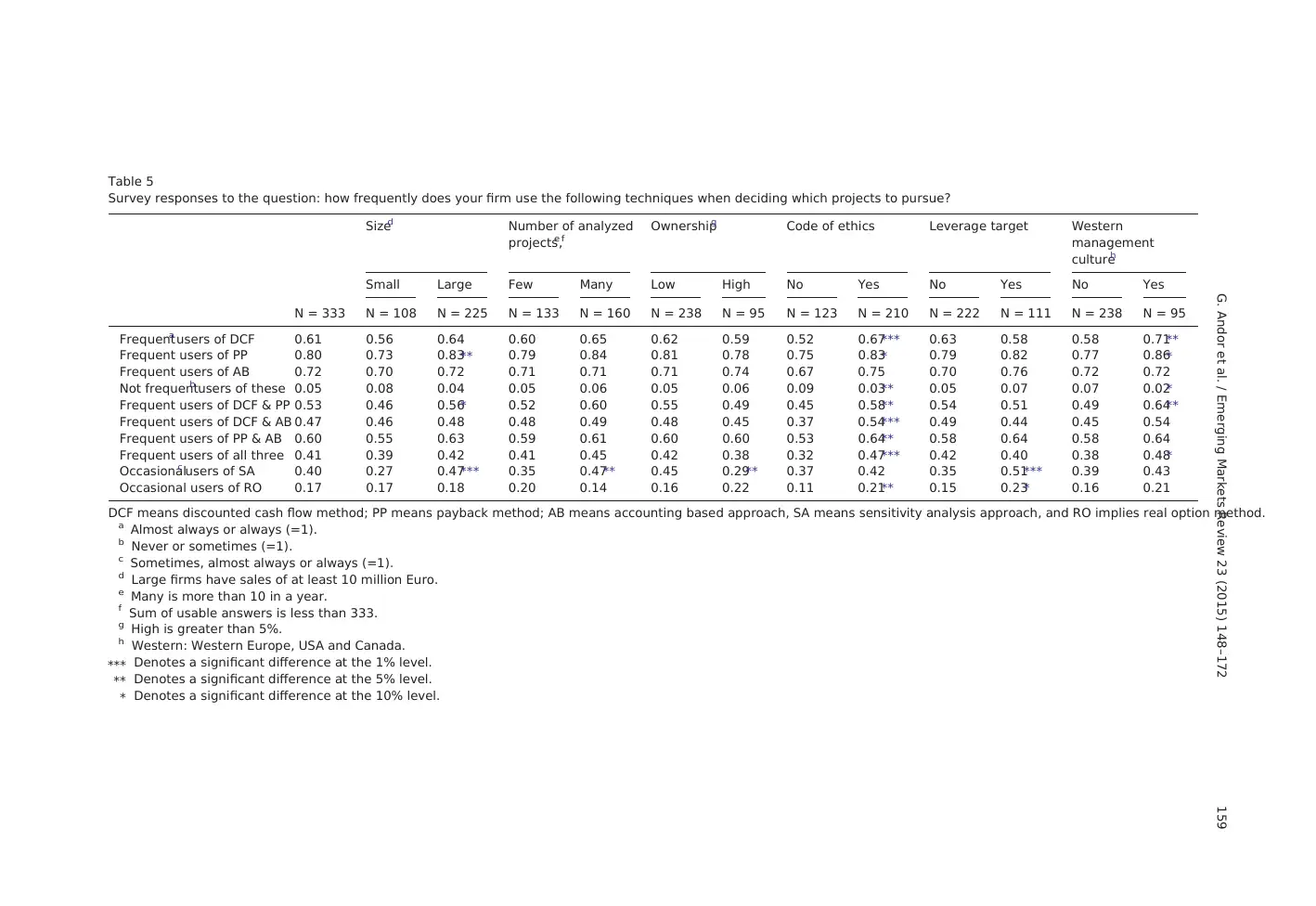

Table 5

Survey responses to the question: how frequently does your firm use the following techniques when deciding which projects to pursue?

Sized Number of analyzed

projectse,f

Ownershipg Code of ethics Leverage target Western

management

cultureh

Small Large Few Many Low High No Yes No Yes No Yes

N = 333 N = 108 N = 225 N = 133 N = 160 N = 238 N = 95 N = 123 N = 210 N = 222 N = 111 N = 238 N = 95

Frequenta users of DCF 0.61 0.56 0.64 0.60 0.65 0.62 0.59 0.52 0.67⁎⁎⁎ 0.63 0.58 0.58 0.71⁎⁎

Frequent users of PP 0.80 0.73 0.83⁎⁎ 0.79 0.84 0.81 0.78 0.75 0.83⁎ 0.79 0.82 0.77 0.86⁎

Frequent users of AB 0.72 0.70 0.72 0.71 0.71 0.71 0.74 0.67 0.75 0.70 0.76 0.72 0.72

Not frequentb users of these 0.05 0.08 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.05 0.06 0.09 0.03⁎⁎ 0.05 0.07 0.07 0.02⁎

Frequent users of DCF & PP 0.53 0.46 0.56⁎ 0.52 0.60 0.55 0.49 0.45 0.58⁎⁎ 0.54 0.51 0.49 0.64⁎⁎

Frequent users of DCF & AB 0.47 0.46 0.48 0.48 0.49 0.48 0.45 0.37 0.54⁎⁎⁎ 0.49 0.44 0.45 0.54

Frequent users of PP & AB 0.60 0.55 0.63 0.59 0.61 0.60 0.60 0.53 0.64⁎⁎ 0.58 0.64 0.58 0.64

Frequent users of all three 0.41 0.39 0.42 0.41 0.45 0.42 0.38 0.32 0.47⁎⁎⁎ 0.42 0.40 0.38 0.48⁎

Occasionalc users of SA 0.40 0.27 0.47⁎⁎⁎ 0.35 0.47⁎⁎ 0.45 0.29⁎⁎ 0.37 0.42 0.35 0.51⁎⁎⁎ 0.39 0.43

Occasional users of RO 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.20 0.14 0.16 0.22 0.11 0.21⁎⁎ 0.15 0.23⁎ 0.16 0.21

DCF means discounted cash flow method; PP means payback method; AB means accounting based approach, SA means sensitivity analysis approach, and RO implies real option method.

a Almost always or always (=1).

b Never or sometimes (=1).

c Sometimes, almost always or always (=1).

d Large firms have sales of at least 10 million Euro.

e Many is more than 10 in a year.

f Sum of usable answers is less than 333.

g High is greater than 5%.

h Western: Western Europe, USA and Canada.

⁎⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 1% level.

⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 5% level.

⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 10% level.

159G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

Survey responses to the question: how frequently does your firm use the following techniques when deciding which projects to pursue?

Sized Number of analyzed

projectse,f

Ownershipg Code of ethics Leverage target Western

management

cultureh

Small Large Few Many Low High No Yes No Yes No Yes

N = 333 N = 108 N = 225 N = 133 N = 160 N = 238 N = 95 N = 123 N = 210 N = 222 N = 111 N = 238 N = 95

Frequenta users of DCF 0.61 0.56 0.64 0.60 0.65 0.62 0.59 0.52 0.67⁎⁎⁎ 0.63 0.58 0.58 0.71⁎⁎

Frequent users of PP 0.80 0.73 0.83⁎⁎ 0.79 0.84 0.81 0.78 0.75 0.83⁎ 0.79 0.82 0.77 0.86⁎

Frequent users of AB 0.72 0.70 0.72 0.71 0.71 0.71 0.74 0.67 0.75 0.70 0.76 0.72 0.72

Not frequentb users of these 0.05 0.08 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.05 0.06 0.09 0.03⁎⁎ 0.05 0.07 0.07 0.02⁎

Frequent users of DCF & PP 0.53 0.46 0.56⁎ 0.52 0.60 0.55 0.49 0.45 0.58⁎⁎ 0.54 0.51 0.49 0.64⁎⁎

Frequent users of DCF & AB 0.47 0.46 0.48 0.48 0.49 0.48 0.45 0.37 0.54⁎⁎⁎ 0.49 0.44 0.45 0.54

Frequent users of PP & AB 0.60 0.55 0.63 0.59 0.61 0.60 0.60 0.53 0.64⁎⁎ 0.58 0.64 0.58 0.64

Frequent users of all three 0.41 0.39 0.42 0.41 0.45 0.42 0.38 0.32 0.47⁎⁎⁎ 0.42 0.40 0.38 0.48⁎

Occasionalc users of SA 0.40 0.27 0.47⁎⁎⁎ 0.35 0.47⁎⁎ 0.45 0.29⁎⁎ 0.37 0.42 0.35 0.51⁎⁎⁎ 0.39 0.43

Occasional users of RO 0.17 0.17 0.18 0.20 0.14 0.16 0.22 0.11 0.21⁎⁎ 0.15 0.23⁎ 0.16 0.21

DCF means discounted cash flow method; PP means payback method; AB means accounting based approach, SA means sensitivity analysis approach, and RO implies real option method.

a Almost always or always (=1).

b Never or sometimes (=1).

c Sometimes, almost always or always (=1).

d Large firms have sales of at least 10 million Euro.

e Many is more than 10 in a year.

f Sum of usable answers is less than 333.

g High is greater than 5%.

h Western: Western Europe, USA and Canada.

⁎⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 1% level.

⁎⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 5% level.

⁎ Denotes a significant difference at the 10% level.

159G. Andor et al. / Emerging Markets Review 23 (2015) 148–172

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 25

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.