NRSG139 Reflective Report: Overcoming Clinical Assessment Challenges

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|14

|9116

|218

Report

AI Summary

This assignment is a reflective report from a nursing student (NRSG139) focusing on the challenges encountered during clinical assessments. The reflection is structured using Gibb's Cycle of Reflection and references the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) Registered Nurse Standards for Practice, specifically Standard 2 (Engages in therapeutic and professional relationships) or Standard 4 (Comprehensively conducts assessments). The report aims to analyze the difficulties in achieving objective and accurate clinical assessments and their implications for future clinical placements. The student is expected to write in the first person, use APA 6th edition referencing, and include the reflection in their professional portfolio. The provided document also includes context regarding registered nurse standards, fitness for practice, and confidentiality declarations within the Australian healthcare system. This document is available for students looking for solved assignments and past papers on Desklib.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283811254

Students experienced help from preservative care. A reflective case study

of two nursing students caring from a nursing framework on good care

Article · November 2015

DOI: 10.19043/ipdj.52.006

CITATIONS

3

READS

85

3 authors, including:

Jan S Jukema

Saxion University of Applied Sciences

52 PUBLICATIONS 106 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Jan S Jukema on 18 November 2015.

Students experienced help from preservative care. A reflective case study

of two nursing students caring from a nursing framework on good care

Article · November 2015

DOI: 10.19043/ipdj.52.006

CITATIONS

3

READS

85

3 authors, including:

Jan S Jukema

Saxion University of Applied Sciences

52 PUBLICATIONS 106 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Jan S Jukema on 18 November 2015.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

1

ORIGINAL PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH

Students experienced help from preservative care. A reflective case study of two nursing

students caring from a nursing framework on good care for older people

Jan S. Jukema*, Netty van Veelen and Rinda Vonk

*Corresponding author: Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, Zwolle, Netherlands

Email: js.jukema@windesheim.nl

Submitted for publication: 8th December 2014

Accepted for publication: 4th August 2015

Publication date: 18th November 2015

doi:10.19043/ipdj.52.006

Abstract

Background: The practice of nursing is shaped partly by nurses’ professional perspective of good care,

guided by a nursing framework. An example is the framework of preservative care, which defines good

nursing care for vulnerable older people in nursing homes. Currently we lack an understanding of how

this framework could help nurses in training; it may be a useful developmental aid for undergraduate

nursing students but so far there are no empirical data to support this.

Aim: The purpose of this study is to explore how helpful a particular framework can be in the

learning journey of two undergraduate nursing students. The study draws on narrative and reflective

accounts, guided by the question: ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good care help two

undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’

Methods: This was a reflective case study, in which two students – experienced registered nurses

(non-graduates) following a part-time education programme – reflected on their practices, using

preservative care as a framework for taking care of older people. They kept reflective journals and

received constructive feedback from the author of the preservative care framework (the first author).

Their data were analysed in three steps.

Findings: Both students reported gaining profound help from the framework in their evaluations of daily

practices, although they rated the help differently in terms of demanding and rewarding experiences.

The framework was particularly helpful in developing qualities in three domains: person-centredness,

professional role and specific nursing competencies.

Conclusions: The results of our study indicate how using a particular nursing framework made a

difference to the practice of two undergraduate nursing students. Exploring the meaning and place of

particular nursing frameworks in nursing education is necessary to establish their potential benefits

for students.

Implications for practice:

• Further development is needed of reflective tools to highlight specific dimensions of nursing

practice and support transformation of students’ learning and practice

• Nursing lecturers could determine how dominant a role a nursing framework should play in

lesson content and how this would contribute to the current requirements that care recipients,

care providers and health organisations have of good care

Keywords: Nursing frameworks, preservative care, reflection, case study, undergraduate nursing

education

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

1

ORIGINAL PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH

Students experienced help from preservative care. A reflective case study of two nursing

students caring from a nursing framework on good care for older people

Jan S. Jukema*, Netty van Veelen and Rinda Vonk

*Corresponding author: Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, Zwolle, Netherlands

Email: js.jukema@windesheim.nl

Submitted for publication: 8th December 2014

Accepted for publication: 4th August 2015

Publication date: 18th November 2015

doi:10.19043/ipdj.52.006

Abstract

Background: The practice of nursing is shaped partly by nurses’ professional perspective of good care,

guided by a nursing framework. An example is the framework of preservative care, which defines good

nursing care for vulnerable older people in nursing homes. Currently we lack an understanding of how

this framework could help nurses in training; it may be a useful developmental aid for undergraduate

nursing students but so far there are no empirical data to support this.

Aim: The purpose of this study is to explore how helpful a particular framework can be in the

learning journey of two undergraduate nursing students. The study draws on narrative and reflective

accounts, guided by the question: ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good care help two

undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’

Methods: This was a reflective case study, in which two students – experienced registered nurses

(non-graduates) following a part-time education programme – reflected on their practices, using

preservative care as a framework for taking care of older people. They kept reflective journals and

received constructive feedback from the author of the preservative care framework (the first author).

Their data were analysed in three steps.

Findings: Both students reported gaining profound help from the framework in their evaluations of daily

practices, although they rated the help differently in terms of demanding and rewarding experiences.

The framework was particularly helpful in developing qualities in three domains: person-centredness,

professional role and specific nursing competencies.

Conclusions: The results of our study indicate how using a particular nursing framework made a

difference to the practice of two undergraduate nursing students. Exploring the meaning and place of

particular nursing frameworks in nursing education is necessary to establish their potential benefits

for students.

Implications for practice:

• Further development is needed of reflective tools to highlight specific dimensions of nursing

practice and support transformation of students’ learning and practice

• Nursing lecturers could determine how dominant a role a nursing framework should play in

lesson content and how this would contribute to the current requirements that care recipients,

care providers and health organisations have of good care

Keywords: Nursing frameworks, preservative care, reflection, case study, undergraduate nursing

education

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

2

Introduction

Nurses, like other healthcare professionals, act and speak in a certain way, expressing how well they

do or do not care for others and what they consider inappropriate or unwanted from their point of

view (Mol, 2010). A nursing point of view stems from several sources: the personal character of the

nurse; work culture; professional guidelines; personal life and work experiences; and formal nursing

education. This last source, nursing education, is aimed at preparing students to meet the standards

of the nursing profession. These standards are partly determined by prevailing attitudes within

the profession to nursing and care. One important reference source for these attitudes is nursing

theories and models (Fawcett, 2005; Meleis, 2007). These provide conceptual and thus substantive

content to the how, what and why of the nursing profession. To Risjord (2010), following Uys (1987),

nursing theories and conceptual models are to be understood as relatively concrete philosophies. This

means the questions posed by theories and models, such as ‘What is nursing?’ cannot be answered

empirically; rather, they remain concrete philosophical questions. Nursing philosophies articulate,

among other things, what the distinctive function, purpose or role of a nurse ought to be (Risjord,

2010). A nursing philosophy can be regarded as a framework through which to see and depict the

professional world. Consequently, certain aspects or dimensions of a given nursing situation come

to the fore, while others move to the background (Jukema, 2011). In a nursing framework that puts

the patient and nurse centre stage, the focus is on the uniqueness of the situation and less on the

technical aspects of care. However, with a framework that emphasises using proven interventions

and achieving standard results, the specific care interactions between nurses and patients receive less

attention. Thus, the framework of nursing care that is most prominent in nurses’ education makes a

difference to the development of their professional identity.

Goal and research question

The first author developed a nursing framework based on the ethics of care and the perspective of

person-centred care. It closely describes good daily nursing care for older people residing in a nursing

home (Jukema, 2011). Called preservative care, this framework gives a description of good care in the

specific context of people who are vulnerable living in a nursing home, and indicates how nurses can

apply the framework. Preservative care is not a skill or a method; rather, it implies a quality, a specific

way of carrying out nursing responsibilities. It is expressed by the caring behaviour of the nurse during

the actual caring interaction with a particular person. Preservative care is both value reinforcing (it

allows people to sustain the value of personhood) and an ethical expression (it is good to work with

people who are vulnerable and dependent). The moral test of this care is ‘recognising the uniqueness

of the other in this particular community’. Preservative care may help nurses and nursing students

provide grounded help in evaluating existing nursing practices for nursing home residents, to criticise

or renew practices and to support the development of new nursing practices. This framework aims

to motivate and inspire nurses to examine daily routines in nursing homes that may seem simple

and dull, and allow them to regard what they are doing as meaningful and valuable, not only to the

residents but to themselves (Jukema, 2011).

Nursing education programmes can employ this specific nursing framework in training nursing

students to become skilled in nursing home care in particular and for vulnerable older persons in

general. Currently, there are no examples of educational materials that could be used for this purpose.

Knowledge is required about the meaning this framework could have for nurses in training, and

this study is intended to provide an initial contribution to obtaining this knowledge. So, the aim of

this explorative reflective study is to exemplify, drawing on narrative and reflective accounts, how

preservative care as a nursing framework can help the learning journey of undergraduate nursing

students. The study is guided by the question: ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good

care help two undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

2

Introduction

Nurses, like other healthcare professionals, act and speak in a certain way, expressing how well they

do or do not care for others and what they consider inappropriate or unwanted from their point of

view (Mol, 2010). A nursing point of view stems from several sources: the personal character of the

nurse; work culture; professional guidelines; personal life and work experiences; and formal nursing

education. This last source, nursing education, is aimed at preparing students to meet the standards

of the nursing profession. These standards are partly determined by prevailing attitudes within

the profession to nursing and care. One important reference source for these attitudes is nursing

theories and models (Fawcett, 2005; Meleis, 2007). These provide conceptual and thus substantive

content to the how, what and why of the nursing profession. To Risjord (2010), following Uys (1987),

nursing theories and conceptual models are to be understood as relatively concrete philosophies. This

means the questions posed by theories and models, such as ‘What is nursing?’ cannot be answered

empirically; rather, they remain concrete philosophical questions. Nursing philosophies articulate,

among other things, what the distinctive function, purpose or role of a nurse ought to be (Risjord,

2010). A nursing philosophy can be regarded as a framework through which to see and depict the

professional world. Consequently, certain aspects or dimensions of a given nursing situation come

to the fore, while others move to the background (Jukema, 2011). In a nursing framework that puts

the patient and nurse centre stage, the focus is on the uniqueness of the situation and less on the

technical aspects of care. However, with a framework that emphasises using proven interventions

and achieving standard results, the specific care interactions between nurses and patients receive less

attention. Thus, the framework of nursing care that is most prominent in nurses’ education makes a

difference to the development of their professional identity.

Goal and research question

The first author developed a nursing framework based on the ethics of care and the perspective of

person-centred care. It closely describes good daily nursing care for older people residing in a nursing

home (Jukema, 2011). Called preservative care, this framework gives a description of good care in the

specific context of people who are vulnerable living in a nursing home, and indicates how nurses can

apply the framework. Preservative care is not a skill or a method; rather, it implies a quality, a specific

way of carrying out nursing responsibilities. It is expressed by the caring behaviour of the nurse during

the actual caring interaction with a particular person. Preservative care is both value reinforcing (it

allows people to sustain the value of personhood) and an ethical expression (it is good to work with

people who are vulnerable and dependent). The moral test of this care is ‘recognising the uniqueness

of the other in this particular community’. Preservative care may help nurses and nursing students

provide grounded help in evaluating existing nursing practices for nursing home residents, to criticise

or renew practices and to support the development of new nursing practices. This framework aims

to motivate and inspire nurses to examine daily routines in nursing homes that may seem simple

and dull, and allow them to regard what they are doing as meaningful and valuable, not only to the

residents but to themselves (Jukema, 2011).

Nursing education programmes can employ this specific nursing framework in training nursing

students to become skilled in nursing home care in particular and for vulnerable older persons in

general. Currently, there are no examples of educational materials that could be used for this purpose.

Knowledge is required about the meaning this framework could have for nurses in training, and

this study is intended to provide an initial contribution to obtaining this knowledge. So, the aim of

this explorative reflective study is to exemplify, drawing on narrative and reflective accounts, how

preservative care as a nursing framework can help the learning journey of undergraduate nursing

students. The study is guided by the question: ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good

care help two undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

3

Preservative care

The framework, categorised as a specific narrative of good care, was developed from a dialectic

process between empirical data and theoretical insights. Empirical data were collected through

participant observations and structured interviews in various care practices. Particular attention was

paid to the ways in which professionals carry out care, with the assumption that when caring for

nursing home residents, nurses express in some way what, in their opinion, is morally good or not

good. The theoretical insights are derived from the literature on person-centred care and the ethics

of care. Both accord a central position to care, to the context of giving and receiving care, and to

the interrelationships between those involved in the practice of care. In a spiralling research model,

empirical data and theoretical insight are continually connected, compared and tested against each

other, and then merged step by step into a coherent whole.

Preserving uniqueness

The framework of preservative care was developed in response to the observation that the vulnerability

of nursing home residents demands a specific form of protection. Without protection, these residents

risk losing their personhood – the unique way they lead their lives and distinguish themselves from

other people; the answer to ‘Who am I?’ To remain and thrive as unique individuals, nursing home

residents depend on the care of others. The vulnerability of their personhood requires protection.

Given that professional nurses are in the immediate vicinity of nursing home residents, day in, day out,

they are well placed to offer that protection. Preservation is a dynamic process of ‘continuation’ and

‘becoming’. In preservation as continuation, the priority lies in maintaining that which is precious and

familiar to someone. This can involve certain personal, familiar habits in the daily care of body and

environment. In preservation as becoming, the priority is to enable, where possible, the creation of

something new in the person’s life that contributes to who they are as a unique individual. Examples

are new hobbies, new skills or changes in a person’s character, such as from being egocentric to being

more open and sociable. After all, people’s lives do not have a final, rounded-off destination – well into

old age, people maintain the capacity to become unique. Through interaction with others, a person

can take a new direction or even add a new dimension to their identity. That is precisely the dynamic

of continuity and of becoming in preserving.

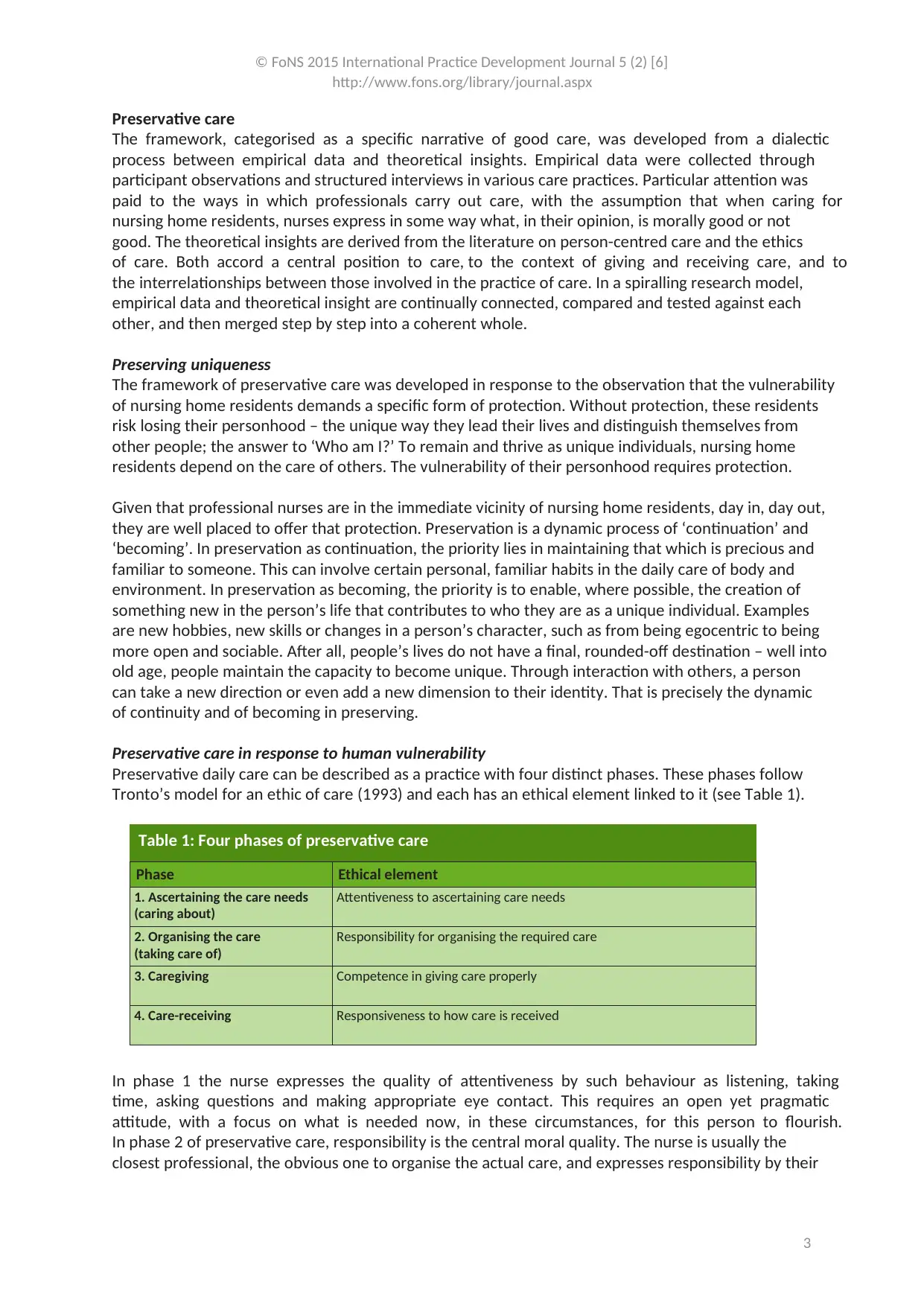

Preservative care in response to human vulnerability

Preservative daily care can be described as a practice with four distinct phases. These phases follow

Tronto’s model for an ethic of care (1993) and each has an ethical element linked to it (see Table 1).

Phase Ethical element

1. Ascertaining the care needs

(caring about)

Attentiveness to ascertaining care needs

2. Organising the care

(taking care of)

Responsibility for organising the required care

3. Caregiving Competence in giving care properly

4. Care-receiving Responsiveness to how care is received

Table 1: Four phases of preservative care

In phase 1 the nurse expresses the quality of attentiveness by such behaviour as listening, taking

time, asking questions and making appropriate eye contact. This requires an open yet pragmatic

attitude, with a focus on what is needed now, in these circumstances, for this person to flourish.

In phase 2 of preservative care, responsibility is the central moral quality. The nurse is usually the

closest professional, the obvious one to organise the actual care, and expresses responsibility by their

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

3

Preservative care

The framework, categorised as a specific narrative of good care, was developed from a dialectic

process between empirical data and theoretical insights. Empirical data were collected through

participant observations and structured interviews in various care practices. Particular attention was

paid to the ways in which professionals carry out care, with the assumption that when caring for

nursing home residents, nurses express in some way what, in their opinion, is morally good or not

good. The theoretical insights are derived from the literature on person-centred care and the ethics

of care. Both accord a central position to care, to the context of giving and receiving care, and to

the interrelationships between those involved in the practice of care. In a spiralling research model,

empirical data and theoretical insight are continually connected, compared and tested against each

other, and then merged step by step into a coherent whole.

Preserving uniqueness

The framework of preservative care was developed in response to the observation that the vulnerability

of nursing home residents demands a specific form of protection. Without protection, these residents

risk losing their personhood – the unique way they lead their lives and distinguish themselves from

other people; the answer to ‘Who am I?’ To remain and thrive as unique individuals, nursing home

residents depend on the care of others. The vulnerability of their personhood requires protection.

Given that professional nurses are in the immediate vicinity of nursing home residents, day in, day out,

they are well placed to offer that protection. Preservation is a dynamic process of ‘continuation’ and

‘becoming’. In preservation as continuation, the priority lies in maintaining that which is precious and

familiar to someone. This can involve certain personal, familiar habits in the daily care of body and

environment. In preservation as becoming, the priority is to enable, where possible, the creation of

something new in the person’s life that contributes to who they are as a unique individual. Examples

are new hobbies, new skills or changes in a person’s character, such as from being egocentric to being

more open and sociable. After all, people’s lives do not have a final, rounded-off destination – well into

old age, people maintain the capacity to become unique. Through interaction with others, a person

can take a new direction or even add a new dimension to their identity. That is precisely the dynamic

of continuity and of becoming in preserving.

Preservative care in response to human vulnerability

Preservative daily care can be described as a practice with four distinct phases. These phases follow

Tronto’s model for an ethic of care (1993) and each has an ethical element linked to it (see Table 1).

Phase Ethical element

1. Ascertaining the care needs

(caring about)

Attentiveness to ascertaining care needs

2. Organising the care

(taking care of)

Responsibility for organising the required care

3. Caregiving Competence in giving care properly

4. Care-receiving Responsiveness to how care is received

Table 1: Four phases of preservative care

In phase 1 the nurse expresses the quality of attentiveness by such behaviour as listening, taking

time, asking questions and making appropriate eye contact. This requires an open yet pragmatic

attitude, with a focus on what is needed now, in these circumstances, for this person to flourish.

In phase 2 of preservative care, responsibility is the central moral quality. The nurse is usually the

closest professional, the obvious one to organise the actual care, and expresses responsibility by their

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

4

motivated choices and the results of these. Competence is the key quality required in phase 3: being

competent is crucial in helping to preserve someone’s uniqueness. The more competent the nurse, the

larger their repertoire of actions, and the better the care can be. A sensitive attitude and the empathy

to attune to the person in context play important roles in competence. Phase 4 is characterised by

responsiveness – that is, the nurse’s ability to respond to the way care is received. Responsiveness

is necessary so that the preservative character of the care can be tested, and to answer the critical

question ‘Does this care meet what is needed to preserve this resident as a unique person in this

specific situation?’

Method

This study was designed and conducted by the lead author and developer of the preservative care

framework (Jukema, 2011). The author’s background includes more than 15 years as a lecturer and

researcher in higher education for nurses, with expertise in the field of care ethics and person-centred

care and a particular interest in the relational dimensions of care practices. From this involvement

stems a commitment to further developing the preservative care framework for nursing education. A

first step was conducting an exploratory study of students’ experiences in providing preservative care.

This required a reflective case study approach in line with Schön’s (1983) seminal work on the reflective

practitioner. Reflection is generally accepted in practice and education as an essential attribute of

competent professionals (Mann et al., 2009). In addition, critical reflexivity is viewed as a research

method (Freshwater and Rolfe, 2001).

This case study was made available to nursing students as an option in their training programme.

The purpose was to gain experience in providing care with the framework of preservative care, to

reflect systematically on the framework and to write a report about the experience. Whether and

to what extent the students would succeed in giving form to preservative care was not a criterion

for evaluation. The final report was evaluated for completeness and consistency. Two undergraduate

students, co-authors of this study Netty van Veelen and Rinda Vonk, volunteered for this elective

course lasting one academic semester in the final year of their training programme (see Box 1). They

were following the four-year, part-time undergraduate programme that leads to a bachelor’s degree

in nursing. Both were registered nurses with considerable experience of geriatric nursing. Neither

had consciously or deliberately worked from a particular framework of care provision before or been

taught to do so. Before following this course, the students were informed about the research purpose

of their assignment. They gave their permission for the results of their assignments to also serve as

research material.

Netty, female, aged 52 Rinda, female, aged 43

A nursing student who began her career as an

auxiliary nurse in a nursing home. After training as

a registered nurse, she took a certificate course in

cancer nursing care. Two years ago she began a part-

time BSc in nursing, while working as a registered

nurse in the same nursing home.

Netty’s main responsibility is supervising care

assistants and auxiliary nurses in their daily

caregiving. She is assigned to such tasks as

administering medications, treatment and

supervising complex care situations.

The nursing home does not hold or articulate a

specific philosophy on care for older persons.

A nursing student who also began her career as an

auxiliary nurse in a nursing home. She trained as a

registered nurse, and two years ago started a part-

time BSc in nursing.

She has worked for 10 years as a community

nurse, mostly at weekends and nights. Now she is

a case manager in community care and has special

responsibility for care improvement. Rinda is not

usually involved in providing daily nursing care.

The healthcare organisation she works for is

committed to the Planetree approach to patient-

centred care as its overall philosophy of caring.

Box 1: The two student nurse volunteers

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

4

motivated choices and the results of these. Competence is the key quality required in phase 3: being

competent is crucial in helping to preserve someone’s uniqueness. The more competent the nurse, the

larger their repertoire of actions, and the better the care can be. A sensitive attitude and the empathy

to attune to the person in context play important roles in competence. Phase 4 is characterised by

responsiveness – that is, the nurse’s ability to respond to the way care is received. Responsiveness

is necessary so that the preservative character of the care can be tested, and to answer the critical

question ‘Does this care meet what is needed to preserve this resident as a unique person in this

specific situation?’

Method

This study was designed and conducted by the lead author and developer of the preservative care

framework (Jukema, 2011). The author’s background includes more than 15 years as a lecturer and

researcher in higher education for nurses, with expertise in the field of care ethics and person-centred

care and a particular interest in the relational dimensions of care practices. From this involvement

stems a commitment to further developing the preservative care framework for nursing education. A

first step was conducting an exploratory study of students’ experiences in providing preservative care.

This required a reflective case study approach in line with Schön’s (1983) seminal work on the reflective

practitioner. Reflection is generally accepted in practice and education as an essential attribute of

competent professionals (Mann et al., 2009). In addition, critical reflexivity is viewed as a research

method (Freshwater and Rolfe, 2001).

This case study was made available to nursing students as an option in their training programme.

The purpose was to gain experience in providing care with the framework of preservative care, to

reflect systematically on the framework and to write a report about the experience. Whether and

to what extent the students would succeed in giving form to preservative care was not a criterion

for evaluation. The final report was evaluated for completeness and consistency. Two undergraduate

students, co-authors of this study Netty van Veelen and Rinda Vonk, volunteered for this elective

course lasting one academic semester in the final year of their training programme (see Box 1). They

were following the four-year, part-time undergraduate programme that leads to a bachelor’s degree

in nursing. Both were registered nurses with considerable experience of geriatric nursing. Neither

had consciously or deliberately worked from a particular framework of care provision before or been

taught to do so. Before following this course, the students were informed about the research purpose

of their assignment. They gave their permission for the results of their assignments to also serve as

research material.

Netty, female, aged 52 Rinda, female, aged 43

A nursing student who began her career as an

auxiliary nurse in a nursing home. After training as

a registered nurse, she took a certificate course in

cancer nursing care. Two years ago she began a part-

time BSc in nursing, while working as a registered

nurse in the same nursing home.

Netty’s main responsibility is supervising care

assistants and auxiliary nurses in their daily

caregiving. She is assigned to such tasks as

administering medications, treatment and

supervising complex care situations.

The nursing home does not hold or articulate a

specific philosophy on care for older persons.

A nursing student who also began her career as an

auxiliary nurse in a nursing home. She trained as a

registered nurse, and two years ago started a part-

time BSc in nursing.

She has worked for 10 years as a community

nurse, mostly at weekends and nights. Now she is

a case manager in community care and has special

responsibility for care improvement. Rinda is not

usually involved in providing daily nursing care.

The healthcare organisation she works for is

committed to the Planetree approach to patient-

centred care as its overall philosophy of caring.

Box 1: The two student nurse volunteers

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

5

The core of Netty and Rinda’s assignment was to look after their clients according to the framework

of preservative care, and subsequently reflect on and document their care practices. Netty cares

for older people in a nursing home, while Rinda looks after older people in the community. Both

combined the roles of practitioner and researcher for the purposes of this study. The study contained

five components:

1. An in-depth study of preservative care as a framework of good daily nursing care

2. Deliberate use of the framework in caring for older people

3. Keeping a structured reflective journal with the aid of a reflection tool

4. Receiving constructive feedback on the documented reflections from the author of the

framework

5. To go on taking care of people, applying new or deepened insights gained from their own

reflections

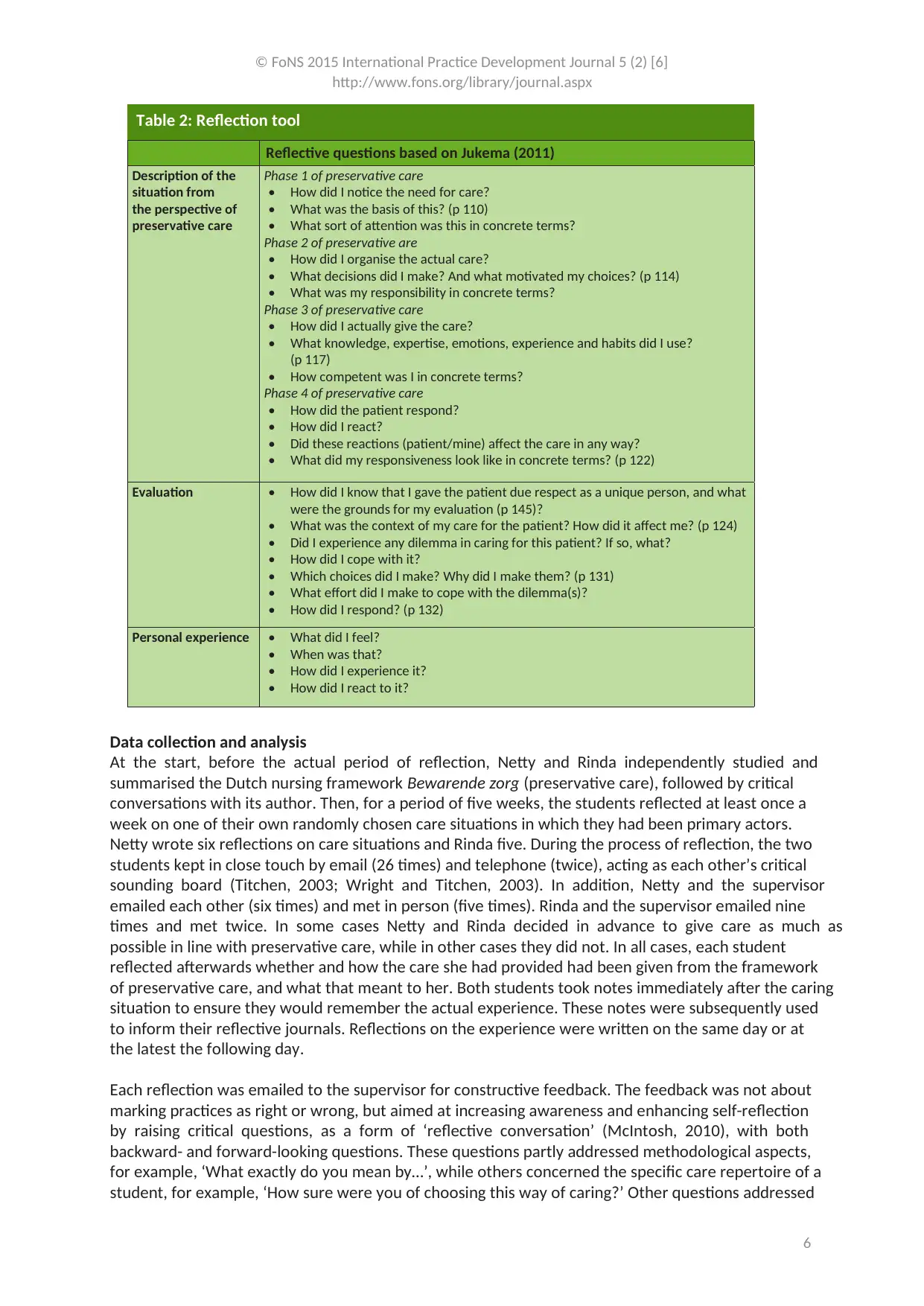

Reflection tool

Reflection is considered a key function in the professionalisation of nurses and the improvement of

nursing care practices. In particular, the process of practice development emphasises the value of

reflection and its importance in establishing practice objectives. Many, if not all, tools and methods of

reflection address the different layers and dimensions of nursing practices. These tools are designed

to be content-neutral. The reflection tool used in this study facilitated the data collection needed

to answer the research question. That was the reason for basing the tool on the reflection phase in

general and the central concepts of the preservative care framework. Each reflective question links

directly to the content by referring to specific pages of the book on the framework (Jukema, 2011). The

tool covers various domains of reflection as suggested by Johns (2009): description of the situation;

reflection; influencing factors; different scenarios; and learning. Reflective questions were formulated

as far as possible in line with the language (the same vocabulary) of preservative care (see Table 2).

These questions facilitated one layer of reflection, namely a dialogue with the story (Johns, 2006).

This dialogue is followed by another layer of reflection, namely a dialogue between texts with other

sources of knowing (Johns, 2006). In this case, an important source of knowing comes from the author

of preservative care, the first author of this paper.

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

5

The core of Netty and Rinda’s assignment was to look after their clients according to the framework

of preservative care, and subsequently reflect on and document their care practices. Netty cares

for older people in a nursing home, while Rinda looks after older people in the community. Both

combined the roles of practitioner and researcher for the purposes of this study. The study contained

five components:

1. An in-depth study of preservative care as a framework of good daily nursing care

2. Deliberate use of the framework in caring for older people

3. Keeping a structured reflective journal with the aid of a reflection tool

4. Receiving constructive feedback on the documented reflections from the author of the

framework

5. To go on taking care of people, applying new or deepened insights gained from their own

reflections

Reflection tool

Reflection is considered a key function in the professionalisation of nurses and the improvement of

nursing care practices. In particular, the process of practice development emphasises the value of

reflection and its importance in establishing practice objectives. Many, if not all, tools and methods of

reflection address the different layers and dimensions of nursing practices. These tools are designed

to be content-neutral. The reflection tool used in this study facilitated the data collection needed

to answer the research question. That was the reason for basing the tool on the reflection phase in

general and the central concepts of the preservative care framework. Each reflective question links

directly to the content by referring to specific pages of the book on the framework (Jukema, 2011). The

tool covers various domains of reflection as suggested by Johns (2009): description of the situation;

reflection; influencing factors; different scenarios; and learning. Reflective questions were formulated

as far as possible in line with the language (the same vocabulary) of preservative care (see Table 2).

These questions facilitated one layer of reflection, namely a dialogue with the story (Johns, 2006).

This dialogue is followed by another layer of reflection, namely a dialogue between texts with other

sources of knowing (Johns, 2006). In this case, an important source of knowing comes from the author

of preservative care, the first author of this paper.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

6

Reflective questions based on Jukema (2011)

Description of the

situation from

the perspective of

preservative care

Phase 1 of preservative care

• How did I notice the need for care?

• What was the basis of this? (p 110)

• What sort of attention was this in concrete terms?

Phase 2 of preservative are

• How did I organise the actual care?

• What decisions did I make? And what motivated my choices? (p 114)

• What was my responsibility in concrete terms?

Phase 3 of preservative care

• How did I actually give the care?

• What knowledge, expertise, emotions, experience and habits did I use?

(p 117)

• How competent was I in concrete terms?

Phase 4 of preservative care

• How did the patient respond?

• How did I react?

• Did these reactions (patient/mine) affect the care in any way?

• What did my responsiveness look like in concrete terms? (p 122)

Evaluation • How did I know that I gave the patient due respect as a unique person, and what

were the grounds for my evaluation (p 145)?

• What was the context of my care for the patient? How did it affect me? (p 124)

• Did I experience any dilemma in caring for this patient? If so, what?

• How did I cope with it?

• Which choices did I make? Why did I make them? (p 131)

• What effort did I make to cope with the dilemma(s)?

• How did I respond? (p 132)

Personal experience • What did I feel?

• When was that?

• How did I experience it?

• How did I react to it?

Table 2: Reflection tool

Data collection and analysis

At the start, before the actual period of reflection, Netty and Rinda independently studied and

summarised the Dutch nursing framework Bewarende zorg (preservative care), followed by critical

conversations with its author. Then, for a period of five weeks, the students reflected at least once a

week on one of their own randomly chosen care situations in which they had been primary actors.

Netty wrote six reflections on care situations and Rinda five. During the process of reflection, the two

students kept in close touch by email (26 times) and telephone (twice), acting as each other’s critical

sounding board (Titchen, 2003; Wright and Titchen, 2003). In addition, Netty and the supervisor

emailed each other (six times) and met in person (five times). Rinda and the supervisor emailed nine

times and met twice. In some cases Netty and Rinda decided in advance to give care as much as

possible in line with preservative care, while in other cases they did not. In all cases, each student

reflected afterwards whether and how the care she had provided had been given from the framework

of preservative care, and what that meant to her. Both students took notes immediately after the caring

situation to ensure they would remember the actual experience. These notes were subsequently used

to inform their reflective journals. Reflections on the experience were written on the same day or at

the latest the following day.

Each reflection was emailed to the supervisor for constructive feedback. The feedback was not about

marking practices as right or wrong, but aimed at increasing awareness and enhancing self-reflection

by raising critical questions, as a form of ‘reflective conversation’ (McIntosh, 2010), with both

backward- and forward-looking questions. These questions partly addressed methodological aspects,

for example, ‘What exactly do you mean by…’, while others concerned the specific care repertoire of a

student, for example, ‘How sure were you of choosing this way of caring?’ Other questions addressed

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

6

Reflective questions based on Jukema (2011)

Description of the

situation from

the perspective of

preservative care

Phase 1 of preservative care

• How did I notice the need for care?

• What was the basis of this? (p 110)

• What sort of attention was this in concrete terms?

Phase 2 of preservative are

• How did I organise the actual care?

• What decisions did I make? And what motivated my choices? (p 114)

• What was my responsibility in concrete terms?

Phase 3 of preservative care

• How did I actually give the care?

• What knowledge, expertise, emotions, experience and habits did I use?

(p 117)

• How competent was I in concrete terms?

Phase 4 of preservative care

• How did the patient respond?

• How did I react?

• Did these reactions (patient/mine) affect the care in any way?

• What did my responsiveness look like in concrete terms? (p 122)

Evaluation • How did I know that I gave the patient due respect as a unique person, and what

were the grounds for my evaluation (p 145)?

• What was the context of my care for the patient? How did it affect me? (p 124)

• Did I experience any dilemma in caring for this patient? If so, what?

• How did I cope with it?

• Which choices did I make? Why did I make them? (p 131)

• What effort did I make to cope with the dilemma(s)?

• How did I respond? (p 132)

Personal experience • What did I feel?

• When was that?

• How did I experience it?

• How did I react to it?

Table 2: Reflection tool

Data collection and analysis

At the start, before the actual period of reflection, Netty and Rinda independently studied and

summarised the Dutch nursing framework Bewarende zorg (preservative care), followed by critical

conversations with its author. Then, for a period of five weeks, the students reflected at least once a

week on one of their own randomly chosen care situations in which they had been primary actors.

Netty wrote six reflections on care situations and Rinda five. During the process of reflection, the two

students kept in close touch by email (26 times) and telephone (twice), acting as each other’s critical

sounding board (Titchen, 2003; Wright and Titchen, 2003). In addition, Netty and the supervisor

emailed each other (six times) and met in person (five times). Rinda and the supervisor emailed nine

times and met twice. In some cases Netty and Rinda decided in advance to give care as much as

possible in line with preservative care, while in other cases they did not. In all cases, each student

reflected afterwards whether and how the care she had provided had been given from the framework

of preservative care, and what that meant to her. Both students took notes immediately after the caring

situation to ensure they would remember the actual experience. These notes were subsequently used

to inform their reflective journals. Reflections on the experience were written on the same day or at

the latest the following day.

Each reflection was emailed to the supervisor for constructive feedback. The feedback was not about

marking practices as right or wrong, but aimed at increasing awareness and enhancing self-reflection

by raising critical questions, as a form of ‘reflective conversation’ (McIntosh, 2010), with both

backward- and forward-looking questions. These questions partly addressed methodological aspects,

for example, ‘What exactly do you mean by…’, while others concerned the specific care repertoire of a

student, for example, ‘How sure were you of choosing this way of caring?’ Other questions addressed

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

7

the impact or meaning of the particular framework of preservative care on the students’ own working

experience of caring for older people, such as ‘How did this make a difference to you?’

Analysis

The reflection reports were then analysed, following three steps. First, each student concretely and

carefully analysed their own work to determine what could constitute support generated by the

framework. The second step was to get both students to review each other’s reflection reports. The

third step was to discuss this review in a joint meeting, where the three of us finally reached consensus

on the labels.

Ethical considerations

Rinda and Netty’s participation in this study was voluntary. They received clear, detailed information

about the study’s purpose and method, as it counted as an elective course for them. The required final

product of the course was a portfolio that included reports of the method used, their reflections and

their learning experiences. After the study ended, the two students and supervisor ( the three authors)

came up with the idea to publish their findings. They agreed to use their own names in the published

article, as they viewed the study as an important turning point in their careers. The university’s consent

was not necessary given that the study was an approved teaching assignment.

Findings

The central question of this study is ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good care help two

undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’ We present first a personal,

detailed account of how Netty and Rinda experienced caring for older people from the framework,

and their experiences of the process of reflecting on this. This is followed by a description of specific

skills and qualities that, according to these two students, they developed during the reflection period.

Netty’s experiences

Based on an analysis of her own reflections, Netty summarised her experience of caring for older

people from the preservative care standpoint as follows:

‘Preservative care helped me to observe and listen better to a particular resident, as well as to

other residents and to my colleagues taking care of them. Preservative care resulted in my focusing

on looking and listening to the care needs of the resident; to see what the ‘hidden’ question or

need of this unique person is. It took heaps of mental and physical energy to provide preservative

care in a nursing home that didn’t work with this specific framework. It demanded my orientated

commitment and effort to notice the need for preservative care, to organise and subsequently

apply it. And this asked for my utmost best to escape from my usual daily routines and habits. The

satisfaction I gained from providing preservative care set against the context in which I had to apply

this quality of care confronted me with a dilemma. It threw me off balance because deep down I

want so badly to give good care, but [in my circumstances] it is virtually impossible to do so. I feel

inhibited and limited in this setting, because I can’t work to my full potential. It means also that I’m

not flourishing, which is not a pleasant discovery.

‘Giving preservative care brought me in touch with something beautiful, a deeply felt intention of

doing well for the other. That’s what I want to do, feel, experience and enjoy more often. When I

succeeded in giving preservative care, I was bursting with positive energy. That gives a nurse job

satisfaction. The residents’ responses gave me valuable moments of satisfaction, made me content

and happy as a person. Through the deliberate use of preservative care, I experienced what good

care is, in my opinion, and what happens to me when I don’t give preservative care. When I do, I am

untouched by moral tensions because the context is no longer an imposition. The positive responses

of the residents meant I did my work with more pleasure. I received energy and became energised.

I felt acknowledged in my own uniqueness. I can’t undo what I’ve learned from this study, and it will

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

7

the impact or meaning of the particular framework of preservative care on the students’ own working

experience of caring for older people, such as ‘How did this make a difference to you?’

Analysis

The reflection reports were then analysed, following three steps. First, each student concretely and

carefully analysed their own work to determine what could constitute support generated by the

framework. The second step was to get both students to review each other’s reflection reports. The

third step was to discuss this review in a joint meeting, where the three of us finally reached consensus

on the labels.

Ethical considerations

Rinda and Netty’s participation in this study was voluntary. They received clear, detailed information

about the study’s purpose and method, as it counted as an elective course for them. The required final

product of the course was a portfolio that included reports of the method used, their reflections and

their learning experiences. After the study ended, the two students and supervisor ( the three authors)

came up with the idea to publish their findings. They agreed to use their own names in the published

article, as they viewed the study as an important turning point in their careers. The university’s consent

was not necessary given that the study was an approved teaching assignment.

Findings

The central question of this study is ‘How does preservative care as a framework of good care help two

undergraduate nursing students develop their caring for older people?’ We present first a personal,

detailed account of how Netty and Rinda experienced caring for older people from the framework,

and their experiences of the process of reflecting on this. This is followed by a description of specific

skills and qualities that, according to these two students, they developed during the reflection period.

Netty’s experiences

Based on an analysis of her own reflections, Netty summarised her experience of caring for older

people from the preservative care standpoint as follows:

‘Preservative care helped me to observe and listen better to a particular resident, as well as to

other residents and to my colleagues taking care of them. Preservative care resulted in my focusing

on looking and listening to the care needs of the resident; to see what the ‘hidden’ question or

need of this unique person is. It took heaps of mental and physical energy to provide preservative

care in a nursing home that didn’t work with this specific framework. It demanded my orientated

commitment and effort to notice the need for preservative care, to organise and subsequently

apply it. And this asked for my utmost best to escape from my usual daily routines and habits. The

satisfaction I gained from providing preservative care set against the context in which I had to apply

this quality of care confronted me with a dilemma. It threw me off balance because deep down I

want so badly to give good care, but [in my circumstances] it is virtually impossible to do so. I feel

inhibited and limited in this setting, because I can’t work to my full potential. It means also that I’m

not flourishing, which is not a pleasant discovery.

‘Giving preservative care brought me in touch with something beautiful, a deeply felt intention of

doing well for the other. That’s what I want to do, feel, experience and enjoy more often. When I

succeeded in giving preservative care, I was bursting with positive energy. That gives a nurse job

satisfaction. The residents’ responses gave me valuable moments of satisfaction, made me content

and happy as a person. Through the deliberate use of preservative care, I experienced what good

care is, in my opinion, and what happens to me when I don’t give preservative care. When I do, I am

untouched by moral tensions because the context is no longer an imposition. The positive responses

of the residents meant I did my work with more pleasure. I received energy and became energised.

I felt acknowledged in my own uniqueness. I can’t undo what I’ve learned from this study, and it will

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

8

have a positive effect on how I deal with dependent people and my performance as a role model for

healthcare workers in the nursing home.’

To Netty, the process of taking care of older people from the preservative care perspective and

reflecting on what she was doing was both very demanding and rewarding. After three of her five

reflections, it became painfully clear to her that she now regarded her former way of caregiving – prior

to gaining expertise in giving preservative care – as an unconscious and unintentional act of hurting,

adding to the existing suffering of the nursing home residents. This experience had a huge impact on

her. She took a break for a week and, after consulting her supervisor, gradually took up her assignment

again. She ended her learning journey by stating:

‘Some hidden moral tensions were broken through caring from this framework. Today there is room

for awareness and professional growth... Applying the framework of preservative care challenged

me to think about my profession, my work in general, who I am, what I stand for and how I let my

context influence me.’

Rinda’s experiences

Based on an analysis of her reflections, Rinda summarised her experiences in caring for older people

from the preservative care standpoint as follows:

‘It helped me to consider the uniqueness of each client. I adjusted my actual caring based on what

was necessary at a particular moment, regardless of the mutually agreed nursing care plan. In

many cases, my care departed from the official nursing care plan. Working with preservative care

helped me give the client a central place in my caring. It encouraged me to deepen my way of

communication and observation. By taking a bit more time, I really enjoyed being with my clients.

My work deepened, and clients basked in my attentiveness and care. I experienced their joy and

gratitude as rewarding. Some days were marked by a golden touch! I was challenged far more

to rely on my ability to improvise. I was challenged to find out what a client really needed at a

particular moment. More than that, I had to find new ways of meeting those particular needs at

that moment. I cared more calmly and with more awareness, and really took time for people. It

supported my giving a “little bit extra”. Working with this framework helped me to face my own

“negative” feelings and emotions in caring. And facing them has helped me to realise I’m an ordinary

human too. Even if I have these “negative and bad” thoughts and feelings, I’m still a good nurse.

‘This particular way of caring takes more time and I had to deal with new tensions arising because

of that, although it didn’t cause me any dilemmas maybe because I can organise my own caring

in my community. My clients expressed their gratitude very clearly to me; they gave compliments.

They were happy to see me again. If I was away for a couple of days, they asked my colleagues what

had happened to me. This raised my self-esteem, and made me enjoy my job so much more. It made

me feel proud and really happy. It is so nice to give sincere attention and care. As a matter of fact,

it helps me build a real bond with my clients. To me, preservative care helps preserve a person’s

uniqueness. In short, it helps me give better care. The positive response of clients gives more joy

in my work, and I’m paid more respect as a nurse. This joy shines from me, as it were, and it has

a good effect on my colleagues as well. Even after this assignment ends, I’m going to continue my

preservative care as well as possible.’

For Rinda, the changes in her nursing care evolved more gradually. A possible explanation might be

the current climate of her healthcare organisation. This organisation promotes the delivery of care and

services described by Planetree, which has several commonalities with preservative care. However,

Rinda also reported a meaningful, positive change in her practice. She experienced a sense of liberation

that came about through her acknowledging and writing up her irritation at certain moments in caring

for others:

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

8

have a positive effect on how I deal with dependent people and my performance as a role model for

healthcare workers in the nursing home.’

To Netty, the process of taking care of older people from the preservative care perspective and

reflecting on what she was doing was both very demanding and rewarding. After three of her five

reflections, it became painfully clear to her that she now regarded her former way of caregiving – prior

to gaining expertise in giving preservative care – as an unconscious and unintentional act of hurting,

adding to the existing suffering of the nursing home residents. This experience had a huge impact on

her. She took a break for a week and, after consulting her supervisor, gradually took up her assignment

again. She ended her learning journey by stating:

‘Some hidden moral tensions were broken through caring from this framework. Today there is room

for awareness and professional growth... Applying the framework of preservative care challenged

me to think about my profession, my work in general, who I am, what I stand for and how I let my

context influence me.’

Rinda’s experiences

Based on an analysis of her reflections, Rinda summarised her experiences in caring for older people

from the preservative care standpoint as follows:

‘It helped me to consider the uniqueness of each client. I adjusted my actual caring based on what

was necessary at a particular moment, regardless of the mutually agreed nursing care plan. In

many cases, my care departed from the official nursing care plan. Working with preservative care

helped me give the client a central place in my caring. It encouraged me to deepen my way of

communication and observation. By taking a bit more time, I really enjoyed being with my clients.

My work deepened, and clients basked in my attentiveness and care. I experienced their joy and

gratitude as rewarding. Some days were marked by a golden touch! I was challenged far more

to rely on my ability to improvise. I was challenged to find out what a client really needed at a

particular moment. More than that, I had to find new ways of meeting those particular needs at

that moment. I cared more calmly and with more awareness, and really took time for people. It

supported my giving a “little bit extra”. Working with this framework helped me to face my own

“negative” feelings and emotions in caring. And facing them has helped me to realise I’m an ordinary

human too. Even if I have these “negative and bad” thoughts and feelings, I’m still a good nurse.

‘This particular way of caring takes more time and I had to deal with new tensions arising because

of that, although it didn’t cause me any dilemmas maybe because I can organise my own caring

in my community. My clients expressed their gratitude very clearly to me; they gave compliments.

They were happy to see me again. If I was away for a couple of days, they asked my colleagues what

had happened to me. This raised my self-esteem, and made me enjoy my job so much more. It made

me feel proud and really happy. It is so nice to give sincere attention and care. As a matter of fact,

it helps me build a real bond with my clients. To me, preservative care helps preserve a person’s

uniqueness. In short, it helps me give better care. The positive response of clients gives more joy

in my work, and I’m paid more respect as a nurse. This joy shines from me, as it were, and it has

a good effect on my colleagues as well. Even after this assignment ends, I’m going to continue my

preservative care as well as possible.’

For Rinda, the changes in her nursing care evolved more gradually. A possible explanation might be

the current climate of her healthcare organisation. This organisation promotes the delivery of care and

services described by Planetree, which has several commonalities with preservative care. However,

Rinda also reported a meaningful, positive change in her practice. She experienced a sense of liberation

that came about through her acknowledging and writing up her irritation at certain moments in caring

for others:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

9

‘It gave me a sense of freedom, writing down my irritations too. In my opinion, it gave me a more

“human face” as a nurse. It [nursing] is not only about irritations, it’s also a matter of compassion

and commitment.’

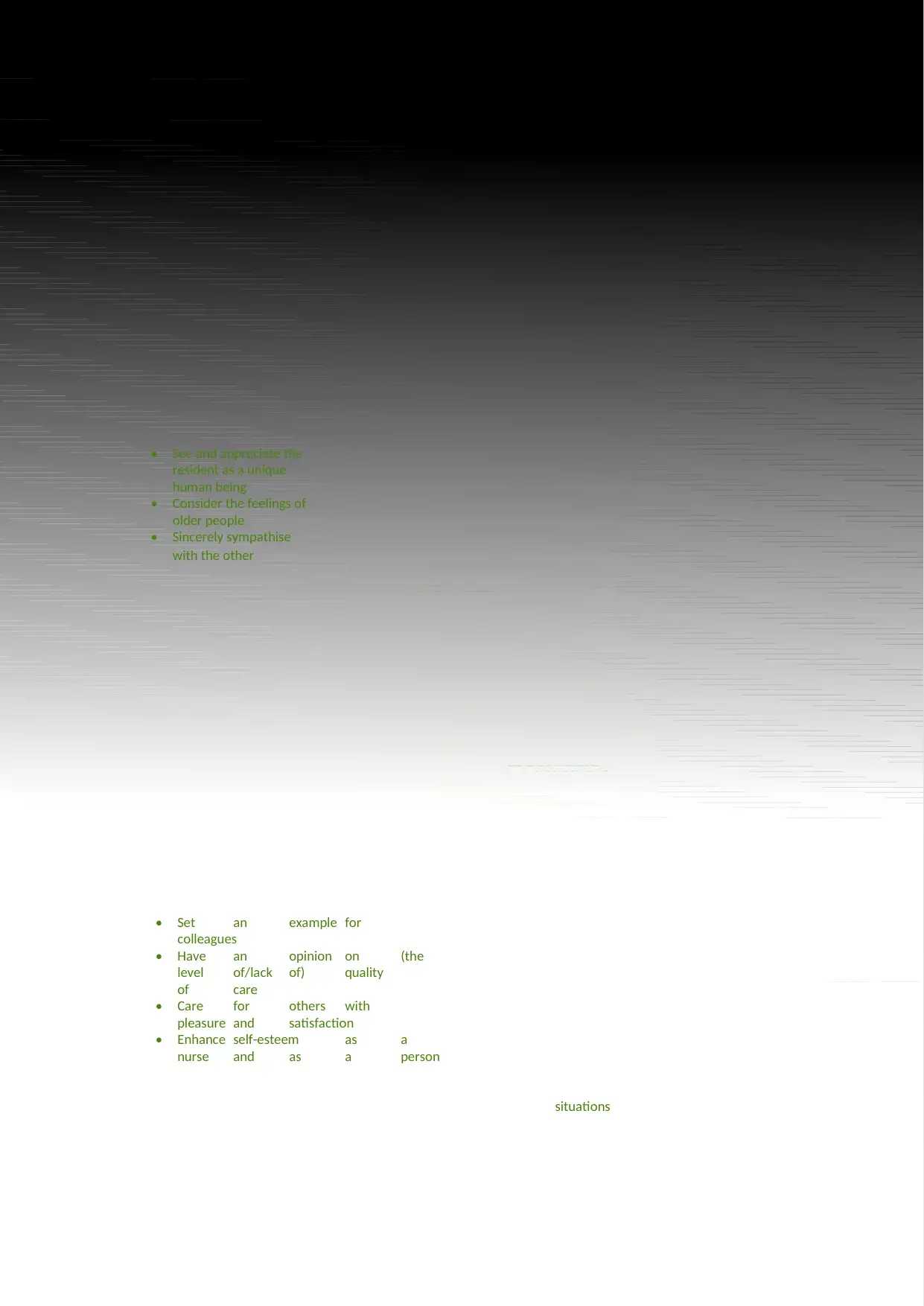

Particular help of preservative care

The two students felt that the preservative care framework was instrumental in their development

and in the deepening of specific skills and qualities. As a nursing framework, preservative care strongly

addresses the reasons for concrete nursing practices for a particularly vulnerable group of care-

dependent people. This framework refers to a specific quality of nursing care that arises from the

specific competencies, attitudes and intentions of nurses. Analyses of the available reflective accounts

revealed that the help these two nursing students experienced enabled them to act in a specific way

in three domains: person-centredness, professional role and competencies. Each domain represents a

number of skills and qualities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nurses’ experienced help in different domains

Professional

role

Person-

centredness

Competencies

• Tune into the unique

situation through

improvisation

• Develop specific skills

or qualities: fine-tuning;

attentiveness; taking

time; improvisation; and

reflection

• Enlarge the component of

loving care

• Respond empathetically to

situations

• Set an example for

colleagues

• Have an opinion on (the

level of/lack of) quality

of care

• Care for others with

pleasure and satisfaction

• Enhance self-esteem as a

nurse and as a person

• See and appreciate the

resident as a unique

human being

• Consider the feelings of

older people

• Sincerely sympathise

with the other

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

9

‘It gave me a sense of freedom, writing down my irritations too. In my opinion, it gave me a more

“human face” as a nurse. It [nursing] is not only about irritations, it’s also a matter of compassion

and commitment.’

Particular help of preservative care

The two students felt that the preservative care framework was instrumental in their development

and in the deepening of specific skills and qualities. As a nursing framework, preservative care strongly

addresses the reasons for concrete nursing practices for a particularly vulnerable group of care-

dependent people. This framework refers to a specific quality of nursing care that arises from the

specific competencies, attitudes and intentions of nurses. Analyses of the available reflective accounts

revealed that the help these two nursing students experienced enabled them to act in a specific way

in three domains: person-centredness, professional role and competencies. Each domain represents a

number of skills and qualities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nurses’ experienced help in different domains

Professional

role

Person-

centredness

Competencies

• Tune into the unique

situation through

improvisation

• Develop specific skills

or qualities: fine-tuning;

attentiveness; taking

time; improvisation; and

reflection

• Enlarge the component of

loving care

• Respond empathetically to

situations

• Set an example for

colleagues

• Have an opinion on (the

level of/lack of) quality

of care

• Care for others with

pleasure and satisfaction

• Enhance self-esteem as a

nurse and as a person

• See and appreciate the

resident as a unique

human being

• Consider the feelings of

older people

• Sincerely sympathise

with the other

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

© FoNS 2015 International Practice Development Journal 5 (2) [6]

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

10

Discussion

In this reflective case study we explored the help two nursing students gained from a particular nursing

framework in their education. Two mature, experienced nurses revitalised their practice by applying

a highly moral, value-laden framework to nursing care. The help it gave them, formulated as concrete

nursing activities and competencies, supports McCormack and McCance’s (2010) view that holistic care

also includes psychical and technical aspects. The help from preservative care that Netty and Rinda

experienced provides an integrated view on actual caregiving, directly considering the contextual,

relational, narrative and embodied dimensions of care practices. We address three issues:

• The impact of reflection on the personal development of Rinda and Netty

• The meaning of their experiences for the position of frameworks in nursing education

• The study’s methodological approach and its implications for nursing education and for

estimating the value of the presented results

Reflection and personal development

For both students, this study counted as an elective course for their BSc in nursing. Although Netty

and Rinda already had several years’ professional experience in caring for older people, they both

experienced a sense of enrichment and actual improvement in their practice through their reflections.

They each went on their own journey in caring using a nursing framework and in reflecting on that.

Netty and Rinda found this study a significant and powerful learning situation; in fact, to them it was

one of the most powerful assignments during their training. As students and practitioners commonly

experience (Mann et al., 2009), keeping a reflective journal further enriched the course. Describing the

situations they experienced turned their previously more detached, technical way of recordkeeping

into a more personal way of reflecting on situations, including specific facts, feelings, thoughts and

considerations in detail. Their experiences, reflections and mutual discussions, and the feedback and

support from their supervisor, not only encouraged them to deepen their current practice, it facilitated

the adding of new dimensions to their professional nursing roles. To be more precise, they experienced

their habitual practice changing in a new, positive way, as a challenging and enriching experience. They

learned to re-evaluate a number of specific skills and capabilities, and to deepen (enrich/intensify)

those that lie within the framework of preservative care.

However, for Netty especially, this achievement was an intense process. After a couple of weeks of

working on her reflections she felt high levels of stress that may be construed as expressions of moral

distress (Jameton, 1984; Burston and Tuckett, 2013). She blamed herself for the ‘poor’ quality of care

she used to deliver, now viewing her past practices through the fresh lens of preservative care. To Netty

and her supervisor – the author of preservative care – this was an unexpected reaction to her reflections

on the past, as was the depth of Netty’s examination of and feelings about her care. Consequently,

Netty was unable to work for a short while but after supportive consultation with the supervisor, she

was able to proceed with her work and her reflections. In the end, this learning experience turned out

to be very powerful and meaningful for her professional and personal development.

Although nursing education research does pay attention to causes of moral distress (Ganske, 2010),

we did not find any studies on a negative relationship between reflection and moral distress. Following

Netty’s experiences, we recommend explorative research on the negative and positive associations of

reflection with moral distress. A wider study on the experienced help of preservative care is currently

under way. It aims to explore whether this nursing framework would be helpful for a larger group of

novice and young undergraduate full-time nursing students.

Nursing frameworks in education

This reflective case study, although small in scale and descriptive, opens a discussion on the meaning

and value of studying and applying nursing philosophies to daily nursing practice. For Netty and Rinda,

this nursing framework became real, not something ‘theoretical’ or ‘abstract’, as is commonly said of

nursing philosophies and other theoretical approaches (Duff, 2011). Both students experienced that

http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx

10

Discussion

In this reflective case study we explored the help two nursing students gained from a particular nursing

framework in their education. Two mature, experienced nurses revitalised their practice by applying

a highly moral, value-laden framework to nursing care. The help it gave them, formulated as concrete

nursing activities and competencies, supports McCormack and McCance’s (2010) view that holistic care

also includes psychical and technical aspects. The help from preservative care that Netty and Rinda

experienced provides an integrated view on actual caregiving, directly considering the contextual,

relational, narrative and embodied dimensions of care practices. We address three issues:

• The impact of reflection on the personal development of Rinda and Netty

• The meaning of their experiences for the position of frameworks in nursing education

• The study’s methodological approach and its implications for nursing education and for

estimating the value of the presented results

Reflection and personal development

For both students, this study counted as an elective course for their BSc in nursing. Although Netty

and Rinda already had several years’ professional experience in caring for older people, they both

experienced a sense of enrichment and actual improvement in their practice through their reflections.

They each went on their own journey in caring using a nursing framework and in reflecting on that.

Netty and Rinda found this study a significant and powerful learning situation; in fact, to them it was

one of the most powerful assignments during their training. As students and practitioners commonly

experience (Mann et al., 2009), keeping a reflective journal further enriched the course. Describing the

situations they experienced turned their previously more detached, technical way of recordkeeping

into a more personal way of reflecting on situations, including specific facts, feelings, thoughts and

considerations in detail. Their experiences, reflections and mutual discussions, and the feedback and

support from their supervisor, not only encouraged them to deepen their current practice, it facilitated

the adding of new dimensions to their professional nursing roles. To be more precise, they experienced

their habitual practice changing in a new, positive way, as a challenging and enriching experience. They

learned to re-evaluate a number of specific skills and capabilities, and to deepen (enrich/intensify)

those that lie within the framework of preservative care.

However, for Netty especially, this achievement was an intense process. After a couple of weeks of

working on her reflections she felt high levels of stress that may be construed as expressions of moral

distress (Jameton, 1984; Burston and Tuckett, 2013). She blamed herself for the ‘poor’ quality of care

she used to deliver, now viewing her past practices through the fresh lens of preservative care. To Netty

and her supervisor – the author of preservative care – this was an unexpected reaction to her reflections

on the past, as was the depth of Netty’s examination of and feelings about her care. Consequently,

Netty was unable to work for a short while but after supportive consultation with the supervisor, she

was able to proceed with her work and her reflections. In the end, this learning experience turned out