Comparative Analysis: Cognitive Therapy and Drug Treatment Efficacy

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|25

|12416

|243

Literature Review

AI Summary

This document presents a meta-analysis examining whether pharmacologic treatment, added to CBT, can improve outcomes over CBT alone for anxiety and depressive disorders. The review synthesizes studies that randomized patients to CBT plus medication versus CBT plus placebo, considering concurrent medication use, stepped care approaches (medication after CBT non-response), and novel agents designed to potentiate CBT mechanisms. The analysis includes double-blind randomized controlled trials evaluating the effects of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and novel compounds on CBT outcomes, with a focus on studies using standardized measures and providing sufficient data for effect size calculation. The review also acknowledges the potential placebo and nocebo effects of adding medications to CBT and discusses the implications of these findings for clinical practice and future research. The clinical question addressed is whether, in patients with depressive disorder, supplementary cognitive behavior therapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy alone.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319908394

Can Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety and

Depression Be Improved with Pharmacotherapy? A

Meta-Analysis

Article in Psychiatric Clinics of North America · September 2017

DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.007

CITATIONS

0

READS

390

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

ENIGMA View project

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, emotion regulation, and anxietyView project

David F Tolin

Hartford Hospital

265 PUBLICATIONS 13,611 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by David F Tolin on 26 September 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319908394

Can Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety and

Depression Be Improved with Pharmacotherapy? A

Meta-Analysis

Article in Psychiatric Clinics of North America · September 2017

DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.007

CITATIONS

0

READS

390

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

ENIGMA View project

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, emotion regulation, and anxietyView project

David F Tolin

Hartford Hospital

265 PUBLICATIONS 13,611 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by David F Tolin on 26 September 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Can Cognitive-Behavioral

Therapy for Anxiety and

Depression Be Improved

with Pharmacotherapy?

A Meta-Analysis

David F. Tolin,PhD

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT IN COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is well established in the treatment o

anxiety and depressive disorders.Meta-analyses ofcontrolled trials indicates a

moderate-sized superiority for CBT versus placebo (PBO)treatment,1,2 and smallto

moderate-sized superiority over alternative psychological treatments such as psychody

namic therapy.3 However, there is clearly room for improvement: across trials, as many

as half of patients receiving CBT are considered nonresponders at posttreatment.4–7

THE POTENTIAL FOR PHARMACOLOGIC AUGMENTATION

Thus, an important question is whether pharmacologic treatment, added to CBT, can

improve outcomes over CBT alone. The efficacy of medications as monotherapies for

Disclosures: Dr D.F. Tolin has received recent research funding from Palo Alto Health Sciences,

Inc. and Pfizer. He receives royalties from Guilford Press, Oxford University Press, Turner Pub-

lishing, and Springer.

The Institute of Living, Anxiety Disorders Center, 200 Retreat Avenue, Hartford, CT 06106, USA

E-mail address: david.tolin@hhchealth.org

KEYWORDS

Cognitive-behavioraltherapy Drug treatment Antidepressants

Anxiety disorders Depression

KEY POINTS

Antidepressant and anxiolytic medications do not consistently or markedly enhance the

effects of CBT for patients with anxiety or depressive disorders.

Antidepressant medications may be efficacious second-line treatments for patients failing

to respond to CBT.

Novel agents that are thought to potentiate the neurobiologicalmechanisms of CBT are

promising but await further study.

Psychiatr Clin N Am- (2017)- –-

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.007 psych.theclinics.com

0193-953X/17/ª 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Therapy for Anxiety and

Depression Be Improved

with Pharmacotherapy?

A Meta-Analysis

David F. Tolin,PhD

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT IN COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is well established in the treatment o

anxiety and depressive disorders.Meta-analyses ofcontrolled trials indicates a

moderate-sized superiority for CBT versus placebo (PBO)treatment,1,2 and smallto

moderate-sized superiority over alternative psychological treatments such as psychody

namic therapy.3 However, there is clearly room for improvement: across trials, as many

as half of patients receiving CBT are considered nonresponders at posttreatment.4–7

THE POTENTIAL FOR PHARMACOLOGIC AUGMENTATION

Thus, an important question is whether pharmacologic treatment, added to CBT, can

improve outcomes over CBT alone. The efficacy of medications as monotherapies for

Disclosures: Dr D.F. Tolin has received recent research funding from Palo Alto Health Sciences,

Inc. and Pfizer. He receives royalties from Guilford Press, Oxford University Press, Turner Pub-

lishing, and Springer.

The Institute of Living, Anxiety Disorders Center, 200 Retreat Avenue, Hartford, CT 06106, USA

E-mail address: david.tolin@hhchealth.org

KEYWORDS

Cognitive-behavioraltherapy Drug treatment Antidepressants

Anxiety disorders Depression

KEY POINTS

Antidepressant and anxiolytic medications do not consistently or markedly enhance the

effects of CBT for patients with anxiety or depressive disorders.

Antidepressant medications may be efficacious second-line treatments for patients failing

to respond to CBT.

Novel agents that are thought to potentiate the neurobiologicalmechanisms of CBT are

promising but await further study.

Psychiatr Clin N Am- (2017)- –-

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.007 psych.theclinics.com

0193-953X/17/ª 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

anxiety and depressive disorders is reasonably wellestablished, although significant

concerns aboutreporting standards (some ofwhich could apply to CBT trials as

wellas pharmacotherapy trials)have been raised.8,9 Across studies, antidepressant

medications,including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs),serotonin-

norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and monoami

oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)show superiority over PBO for depression,10–12 although

the overalleffectis small,13 and may be clinically meaningfulonly in more severe

cases.14,15Among the anxiety disorders, the antidepressant medications, as wellas

anxiolytic medications including benzodiazepines and azapirones, also show a supe

riority to PBO across studies, with medium effects overall.16 When medications and

CBT have been compared directly, across studies the effects are roughly equivalent

at least in the short term.2,16–21

THE NEED TO EXAMINE PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIALS OF

PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC AUGMENTATION

Previous systematic reviews have examined whether the combination of these trea

ments is better than CBT alone. These reviews have generally shown a smalladvan-

tage of combined treatment over CBT alone, although there may be an increased ri

of relapse when medications are withdrawn.22–27Importantly, however, an examina-

tion ofCBT 1 medications versus CBT alone cannot facilitate an adequate under-

standing of the incrementalefficacy of medications.In the absence of a PBO

controlcondition, there is no way to determine the effects of the medication, either

positive or negative. The PBO response rate in anxiety disorders is substantial28; in

one systematic review,pill PBO was demonstrated to increase the probability of

response in panic disorder with agoraphobia (PD/A) by 26%.29

However, the PBO effect also may have the reverse effect in some cases: when pa

tients with PD/A treated with alprazolam (ALP) versus PBO plus CBT rated the exten

to which they believed that their treatment gains were attributable to medication o

their own efforts, those who attributed their gains to medication exhibited a greater

loss of gains following discontinuation than did those who had attributed their gains

to their own efforts during treatment.30 Additionally,when patients with specific

phobia (SpP) treated with exposure plus pill PBO were told that the pill had anxiolyt

properties that would make exposure easier, they were more likely to relapse (39%

after treatment than were patients who were told that the pillhad stimulating proper-

ties that would make exposure more difficult (0%), or those who were told that the

had no effect on exposure (0%).31 Thus, there may be both PBO and “nocebo”32 ef-

fects of adding medications to CBT, beyond the specific pharmacologic effects of th

medication itself. The aim of the present review was to examine the efficacy of pha

macologic augmentation of CBT by synthesizing studies that randomized patients to

CBT 1 medications versus CBT 1 PBO.

The present review considers 3 distinct methods of pharmacologic augmentation

CBT. First, studies in which CBT was applied concurrently with a medication also us

as a monotherapy (eg, CBT plus an SSRI) were examined. Second, studies in which

pharmacologic treatment was administered following CBT nonresponse, rather than

concurrentadministration forall patients,were examined.This strategy relates to

the practice of stepped care,33,34in which treatments are added sequentially only after

nonresponse to the initialtrial. Third, the analysis examines studies that used novel

agents,not prescribed as monotherapies,to augmentCBT. These studies were

limited to the anxiety disorders, in which there has been increasing interest in com-

pounds that do not treat the anxiety directly, but rather are thought to potentiate th

Tolin2

concerns aboutreporting standards (some ofwhich could apply to CBT trials as

wellas pharmacotherapy trials)have been raised.8,9 Across studies, antidepressant

medications,including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs),serotonin-

norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and monoami

oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)show superiority over PBO for depression,10–12 although

the overalleffectis small,13 and may be clinically meaningfulonly in more severe

cases.14,15Among the anxiety disorders, the antidepressant medications, as wellas

anxiolytic medications including benzodiazepines and azapirones, also show a supe

riority to PBO across studies, with medium effects overall.16 When medications and

CBT have been compared directly, across studies the effects are roughly equivalent

at least in the short term.2,16–21

THE NEED TO EXAMINE PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIALS OF

PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC AUGMENTATION

Previous systematic reviews have examined whether the combination of these trea

ments is better than CBT alone. These reviews have generally shown a smalladvan-

tage of combined treatment over CBT alone, although there may be an increased ri

of relapse when medications are withdrawn.22–27Importantly, however, an examina-

tion ofCBT 1 medications versus CBT alone cannot facilitate an adequate under-

standing of the incrementalefficacy of medications.In the absence of a PBO

controlcondition, there is no way to determine the effects of the medication, either

positive or negative. The PBO response rate in anxiety disorders is substantial28; in

one systematic review,pill PBO was demonstrated to increase the probability of

response in panic disorder with agoraphobia (PD/A) by 26%.29

However, the PBO effect also may have the reverse effect in some cases: when pa

tients with PD/A treated with alprazolam (ALP) versus PBO plus CBT rated the exten

to which they believed that their treatment gains were attributable to medication o

their own efforts, those who attributed their gains to medication exhibited a greater

loss of gains following discontinuation than did those who had attributed their gains

to their own efforts during treatment.30 Additionally,when patients with specific

phobia (SpP) treated with exposure plus pill PBO were told that the pill had anxiolyt

properties that would make exposure easier, they were more likely to relapse (39%

after treatment than were patients who were told that the pillhad stimulating proper-

ties that would make exposure more difficult (0%), or those who were told that the

had no effect on exposure (0%).31 Thus, there may be both PBO and “nocebo”32 ef-

fects of adding medications to CBT, beyond the specific pharmacologic effects of th

medication itself. The aim of the present review was to examine the efficacy of pha

macologic augmentation of CBT by synthesizing studies that randomized patients to

CBT 1 medications versus CBT 1 PBO.

The present review considers 3 distinct methods of pharmacologic augmentation

CBT. First, studies in which CBT was applied concurrently with a medication also us

as a monotherapy (eg, CBT plus an SSRI) were examined. Second, studies in which

pharmacologic treatment was administered following CBT nonresponse, rather than

concurrentadministration forall patients,were examined.This strategy relates to

the practice of stepped care,33,34in which treatments are added sequentially only after

nonresponse to the initialtrial. Third, the analysis examines studies that used novel

agents,not prescribed as monotherapies,to augmentCBT. These studies were

limited to the anxiety disorders, in which there has been increasing interest in com-

pounds that do not treat the anxiety directly, but rather are thought to potentiate th

Tolin2

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

mechanisms by which CBT (specifically exposure therapy)exerts its effects.35 Two

compounds that potentiate activity in the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor

in basolateralamygdala (implicated in fear extinction36) includeD-cycloserine (DCS),

which enhances fear extinction in animals,37 and Org 25,935 (ORG), a glycine uptake

inhibitor that enhances working memory in animals.38 Three other compounds pro-

posed to augment exposure therapy increase activity in the medialprefrontalcortex

(mPFC), thoughtto be critical to the extinction of learned fear39–41

: yohimbine

(YOH), an a2-adrenergic receptorantagonistthat enhances fearextinction in ani-

mals42,43

; methylene blue (MB), an autoxidizing agent that enhances fear extinction

in animals44,45

; and oxytocin (OXT),a neuropeptide thatdisrupts signals from the

amygdala to the autonomic nervous system46,47enhances (normalizes) resting state

functionalconnectivity.

METHOD

Data Selection

A search was conducted on PsycINFO (1967–January 2017) using the terms (Cogni-

tive Therapy or Cognitive Behavior Therapy or CBT or Behavior Therapy or Exposure

Therapy) and (Anxiety Disorders or Phobia or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder or Obses-

sive Compulsive Disorder or Panic Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder or Social

Anxiety or Major Depressive Disorder or Major Depression or Dysthymic Disorder or

Persistent Depressive Disorder) and (Medication or Drug Therapy or Antidepressant

or Benzodiazepines orAugmentation),limited to peer-reviewed journals published

in English and listed as clinical trials, empirical studies, longitudinal studies, prospec-

tive studies, or treatment outcome studies. Recent empirical and review articles were

also searched for additionalreferences. Criteria for inclusion were as follows:

1. Double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included a CBT 1 medication

condition and a CBT 1 PBO condition (otherarms, when included,were not

analyzed here).Studies ofadults or children were accepted.Medication lead-in

or extension periods were allowed, so long as there was a simultaneous application

of CBT 1 medications.

2. Clearly defined CBT protocol(Internet-based and self-directed CBT were also

included, but eclectic psychotherapies were not).

3. Participants had a clear primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor-

ders (DSM) diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (categorized according to DSM-IV48) or

unipolar depressive disorder (anxiety and depression within severe medical condi-

tions, comorbid with substance use or developmental disorders, remitted illnesses,

or treatments aimed atsymptoms otherthan anxiety and depression were not

included;student samples were also not included unless they met DSM criteria

for an anxiety or depressive disorder).

4. Used standardized (reliable and valid) self-report or interview-based measures of

the symptoms of the disorder being treated (global measures, functional outcomes,

behavioralavoidance tests,and biomarker outcomes were not analyzed).When

more than one such measure was included, effect sizes were aggregated across

outcome measures. Responder rates were included only when they were based

on a cutoff on a standardized measure of the symptoms of the disorder.

5. Study was judged to be a clinical trial rather than a preclinical study of mechanisms

of action.

6. Provided data (eg, means and SDs, or proportions of responders when such data

were not available) or statistics (eg, change scores or F values) that could be used

to calculate an effectsize. Posttreatmentwas defined as the lastassessment

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 3

compounds that potentiate activity in the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor

in basolateralamygdala (implicated in fear extinction36) includeD-cycloserine (DCS),

which enhances fear extinction in animals,37 and Org 25,935 (ORG), a glycine uptake

inhibitor that enhances working memory in animals.38 Three other compounds pro-

posed to augment exposure therapy increase activity in the medialprefrontalcortex

(mPFC), thoughtto be critical to the extinction of learned fear39–41

: yohimbine

(YOH), an a2-adrenergic receptorantagonistthat enhances fearextinction in ani-

mals42,43

; methylene blue (MB), an autoxidizing agent that enhances fear extinction

in animals44,45

; and oxytocin (OXT),a neuropeptide thatdisrupts signals from the

amygdala to the autonomic nervous system46,47enhances (normalizes) resting state

functionalconnectivity.

METHOD

Data Selection

A search was conducted on PsycINFO (1967–January 2017) using the terms (Cogni-

tive Therapy or Cognitive Behavior Therapy or CBT or Behavior Therapy or Exposure

Therapy) and (Anxiety Disorders or Phobia or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder or Obses-

sive Compulsive Disorder or Panic Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder or Social

Anxiety or Major Depressive Disorder or Major Depression or Dysthymic Disorder or

Persistent Depressive Disorder) and (Medication or Drug Therapy or Antidepressant

or Benzodiazepines orAugmentation),limited to peer-reviewed journals published

in English and listed as clinical trials, empirical studies, longitudinal studies, prospec-

tive studies, or treatment outcome studies. Recent empirical and review articles were

also searched for additionalreferences. Criteria for inclusion were as follows:

1. Double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included a CBT 1 medication

condition and a CBT 1 PBO condition (otherarms, when included,were not

analyzed here).Studies ofadults or children were accepted.Medication lead-in

or extension periods were allowed, so long as there was a simultaneous application

of CBT 1 medications.

2. Clearly defined CBT protocol(Internet-based and self-directed CBT were also

included, but eclectic psychotherapies were not).

3. Participants had a clear primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor-

ders (DSM) diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (categorized according to DSM-IV48) or

unipolar depressive disorder (anxiety and depression within severe medical condi-

tions, comorbid with substance use or developmental disorders, remitted illnesses,

or treatments aimed atsymptoms otherthan anxiety and depression were not

included;student samples were also not included unless they met DSM criteria

for an anxiety or depressive disorder).

4. Used standardized (reliable and valid) self-report or interview-based measures of

the symptoms of the disorder being treated (global measures, functional outcomes,

behavioralavoidance tests,and biomarker outcomes were not analyzed).When

more than one such measure was included, effect sizes were aggregated across

outcome measures. Responder rates were included only when they were based

on a cutoff on a standardized measure of the symptoms of the disorder.

5. Study was judged to be a clinical trial rather than a preclinical study of mechanisms

of action.

6. Provided data (eg, means and SDs, or proportions of responders when such data

were not available) or statistics (eg, change scores or F values) that could be used

to calculate an effectsize. Posttreatmentwas defined as the lastassessment

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

collected during (or immediately following) active treatment. Follow-up was defin

as the last assessment (up to 3 years)after treatment had been discontinued (in

some cases, the last follow-up analysis was published in a separate article).

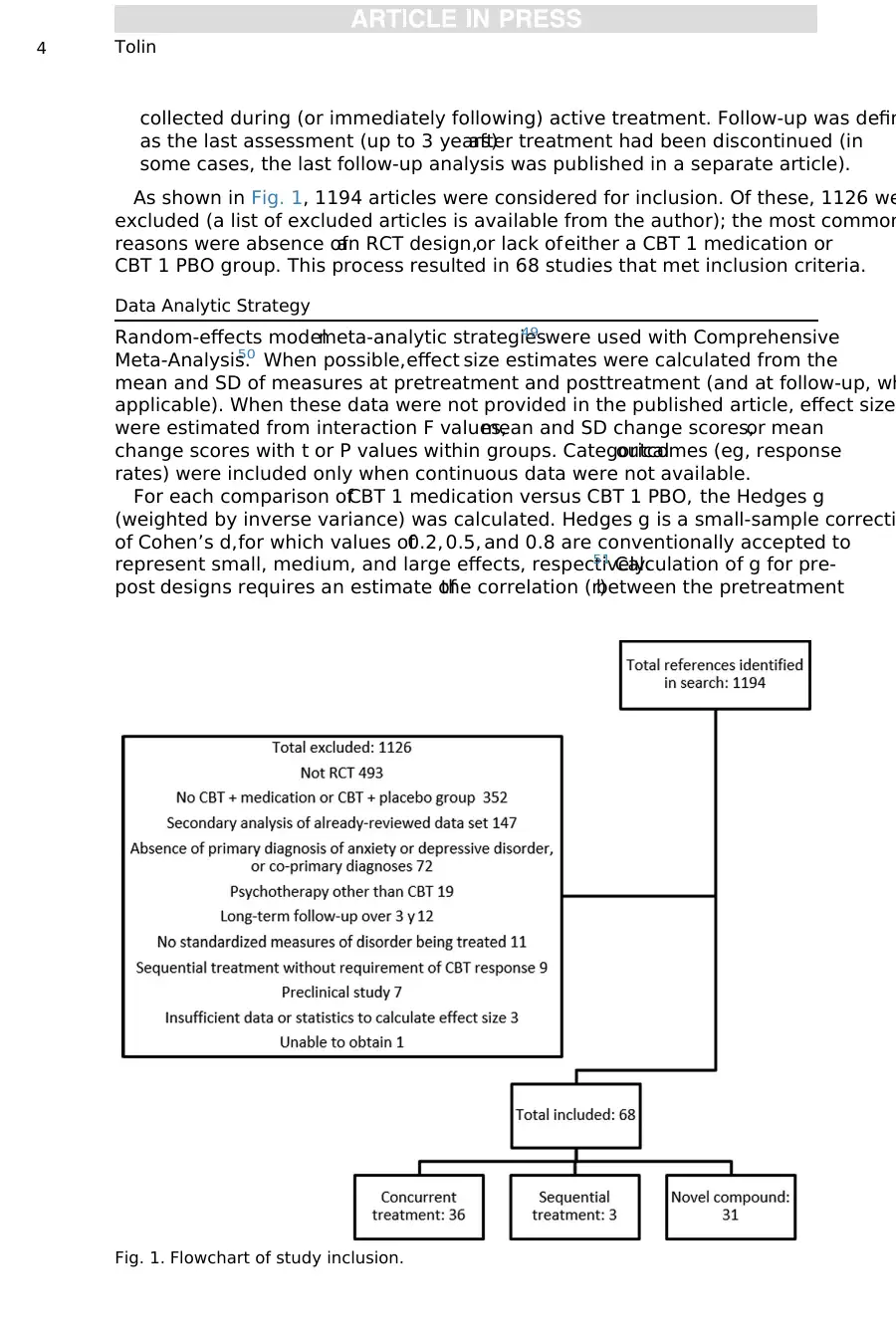

As shown in Fig. 1, 1194 articles were considered for inclusion. Of these, 1126 we

excluded (a list of excluded articles is available from the author); the most common

reasons were absence ofan RCT design,or lack ofeither a CBT 1 medication or

CBT 1 PBO group. This process resulted in 68 studies that met inclusion criteria.

Data Analytic Strategy

Random-effects modelmeta-analytic strategies49 were used with Comprehensive

Meta-Analysis.50 When possible,effect size estimates were calculated from the

mean and SD of measures at pretreatment and posttreatment (and at follow-up, wh

applicable). When these data were not provided in the published article, effect sizes

were estimated from interaction F values,mean and SD change scores,or mean

change scores with t or P values within groups. Categoricaloutcomes (eg, response

rates) were included only when continuous data were not available.

For each comparison ofCBT 1 medication versus CBT 1 PBO, the Hedges g

(weighted by inverse variance) was calculated. Hedges g is a small-sample correcti

of Cohen’s d,for which values of0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are conventionally accepted to

represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively.51 Calculation of g for pre-

post designs requires an estimate ofthe correlation (r)between the pretreatment

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study inclusion.

Tolin4

as the last assessment (up to 3 years)after treatment had been discontinued (in

some cases, the last follow-up analysis was published in a separate article).

As shown in Fig. 1, 1194 articles were considered for inclusion. Of these, 1126 we

excluded (a list of excluded articles is available from the author); the most common

reasons were absence ofan RCT design,or lack ofeither a CBT 1 medication or

CBT 1 PBO group. This process resulted in 68 studies that met inclusion criteria.

Data Analytic Strategy

Random-effects modelmeta-analytic strategies49 were used with Comprehensive

Meta-Analysis.50 When possible,effect size estimates were calculated from the

mean and SD of measures at pretreatment and posttreatment (and at follow-up, wh

applicable). When these data were not provided in the published article, effect sizes

were estimated from interaction F values,mean and SD change scores,or mean

change scores with t or P values within groups. Categoricaloutcomes (eg, response

rates) were included only when continuous data were not available.

For each comparison ofCBT 1 medication versus CBT 1 PBO, the Hedges g

(weighted by inverse variance) was calculated. Hedges g is a small-sample correcti

of Cohen’s d,for which values of0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are conventionally accepted to

represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively.51 Calculation of g for pre-

post designs requires an estimate ofthe correlation (r)between the pretreatment

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study inclusion.

Tolin4

and posttreatment scores; because this was not available in published reports, r was

conservatively estimated at 0.7 according to the recommendation of Rosenthal.52 For

ease of interpretation, pooled g estimates were also converted to number needed to

treat (NNT) using the formula provided by Furukawa,53,54using an estimated overall

50% response rate in CBT 1 PBO.4–7 NNT, in this case, refers to the number of pa-

tients who would have to receive CBT with medication to obtain 1 more favorable

outcome over CBT with PBO. The I2 statistic was used to assess the percentage of

variation due to true heterogeneity rather than chance and is interpreted as follows:

25% 5 little heterogeneity, 50% 5 moderate heterogeneity, and 75% 5 high hetero-

geneity.55 Significance of heterogeneity was established using the Q statistic.

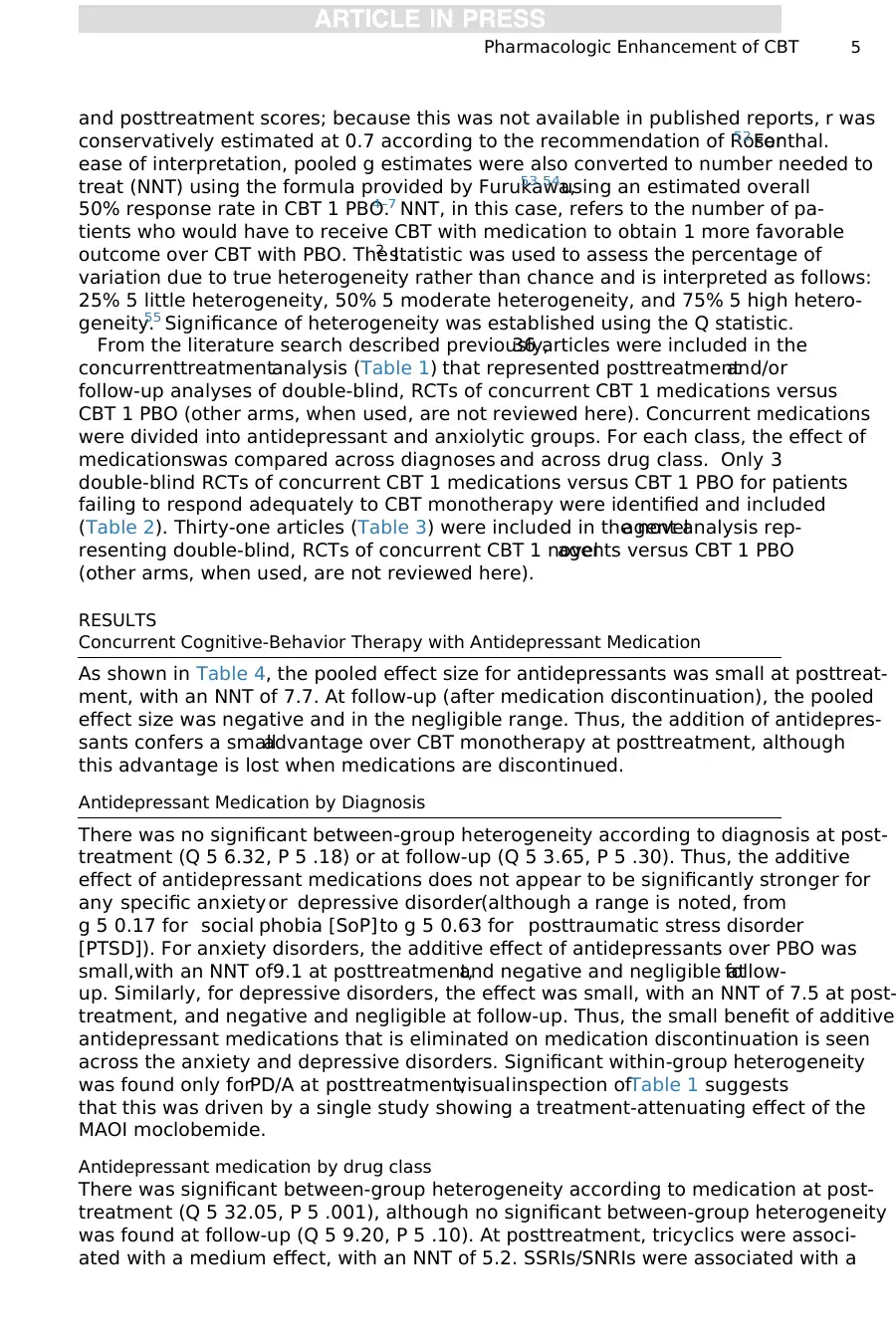

From the literature search described previously,36 articles were included in the

concurrenttreatmentanalysis (Table 1) that represented posttreatmentand/or

follow-up analyses of double-blind, RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 medications versus

CBT 1 PBO (other arms, when used, are not reviewed here). Concurrent medications

were divided into antidepressant and anxiolytic groups. For each class, the effect of

medicationswas compared across diagnoses and across drug class. Only 3

double-blind RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 medications versus CBT 1 PBO for patients

failing to respond adequately to CBT monotherapy were identified and included

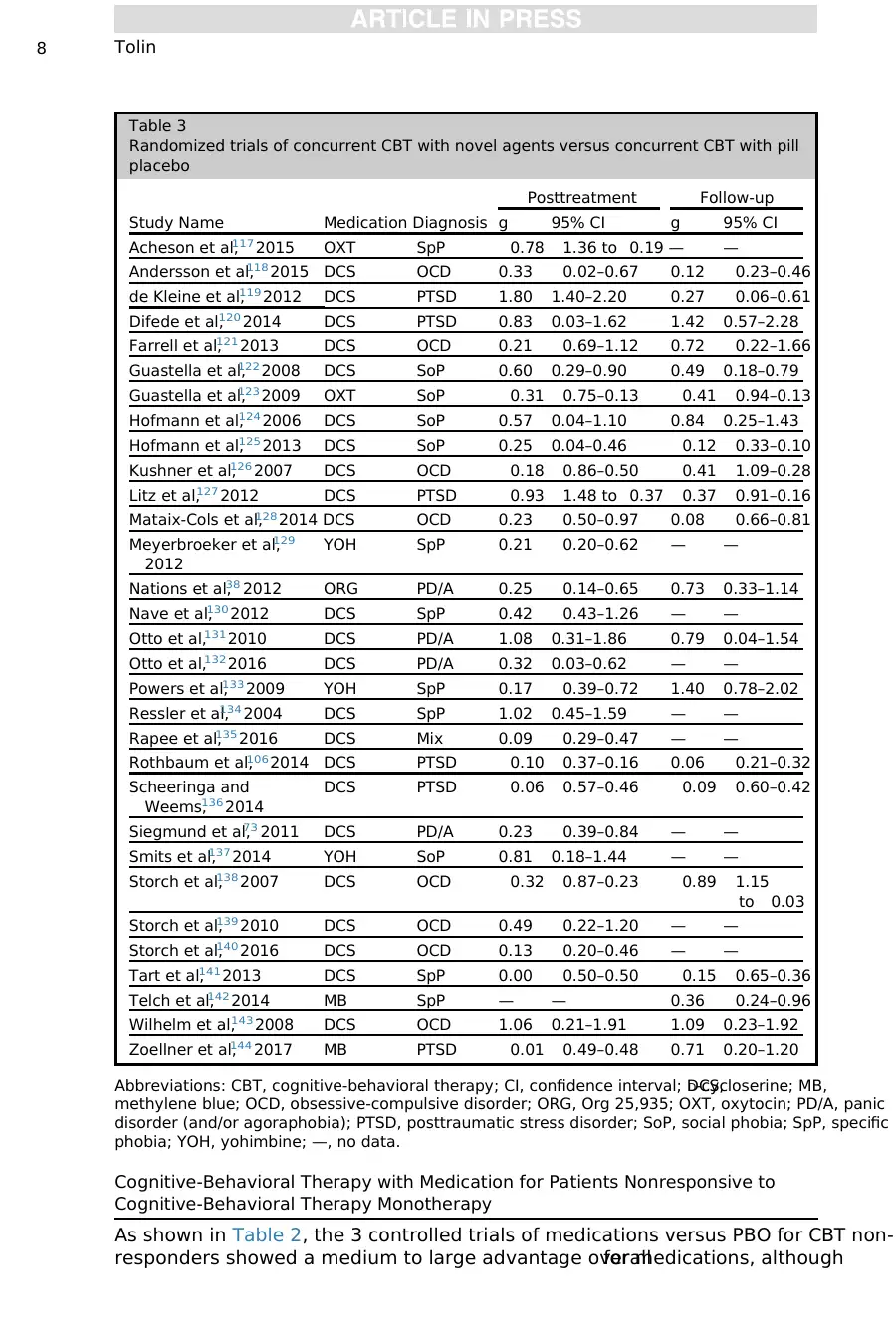

(Table 2). Thirty-one articles (Table 3) were included in the novelagent analysis rep-

resenting double-blind, RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 novelagents versus CBT 1 PBO

(other arms, when used, are not reviewed here).

RESULTS

Concurrent Cognitive-Behavior Therapy with Antidepressant Medication

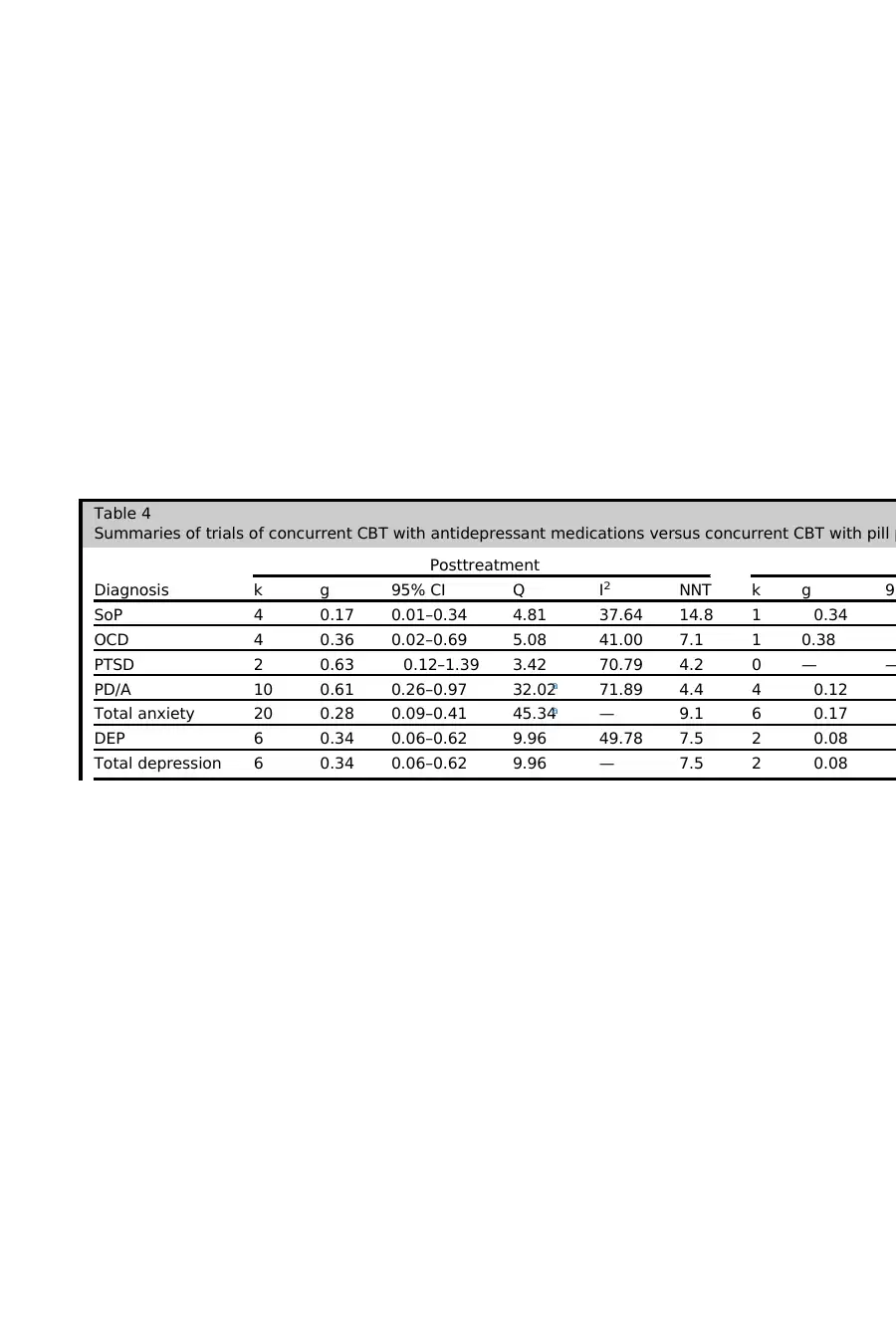

As shown in Table 4, the pooled effect size for antidepressants was small at posttreat-

ment, with an NNT of 7.7. At follow-up (after medication discontinuation), the pooled

effect size was negative and in the negligible range. Thus, the addition of antidepres-

sants confers a smalladvantage over CBT monotherapy at posttreatment, although

this advantage is lost when medications are discontinued.

Antidepressant Medication by Diagnosis

There was no significant between-group heterogeneity according to diagnosis at post-

treatment (Q 5 6.32, P 5 .18) or at follow-up (Q 5 3.65, P 5 .30). Thus, the additive

effect of antidepressant medications does not appear to be significantly stronger for

any specific anxiety or depressive disorder(although a range is noted, from

g 5 0.17 for social phobia [SoP] to g 5 0.63 for posttraumatic stress disorder

[PTSD]). For anxiety disorders, the additive effect of antidepressants over PBO was

small,with an NNT of9.1 at posttreatment,and negative and negligible atfollow-

up. Similarly, for depressive disorders, the effect was small, with an NNT of 7.5 at post-

treatment, and negative and negligible at follow-up. Thus, the small benefit of additive

antidepressant medications that is eliminated on medication discontinuation is seen

across the anxiety and depressive disorders. Significant within-group heterogeneity

was found only forPD/A at posttreatment;visualinspection ofTable 1 suggests

that this was driven by a single study showing a treatment-attenuating effect of the

MAOI moclobemide.

Antidepressant medication by drug class

There was significant between-group heterogeneity according to medication at post-

treatment (Q 5 32.05, P 5 .001), although no significant between-group heterogeneity

was found at follow-up (Q 5 9.20, P 5 .10). At posttreatment, tricyclics were associ-

ated with a medium effect, with an NNT of 5.2. SSRIs/SNRIs were associated with a

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 5

conservatively estimated at 0.7 according to the recommendation of Rosenthal.52 For

ease of interpretation, pooled g estimates were also converted to number needed to

treat (NNT) using the formula provided by Furukawa,53,54using an estimated overall

50% response rate in CBT 1 PBO.4–7 NNT, in this case, refers to the number of pa-

tients who would have to receive CBT with medication to obtain 1 more favorable

outcome over CBT with PBO. The I2 statistic was used to assess the percentage of

variation due to true heterogeneity rather than chance and is interpreted as follows:

25% 5 little heterogeneity, 50% 5 moderate heterogeneity, and 75% 5 high hetero-

geneity.55 Significance of heterogeneity was established using the Q statistic.

From the literature search described previously,36 articles were included in the

concurrenttreatmentanalysis (Table 1) that represented posttreatmentand/or

follow-up analyses of double-blind, RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 medications versus

CBT 1 PBO (other arms, when used, are not reviewed here). Concurrent medications

were divided into antidepressant and anxiolytic groups. For each class, the effect of

medicationswas compared across diagnoses and across drug class. Only 3

double-blind RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 medications versus CBT 1 PBO for patients

failing to respond adequately to CBT monotherapy were identified and included

(Table 2). Thirty-one articles (Table 3) were included in the novelagent analysis rep-

resenting double-blind, RCTs of concurrent CBT 1 novelagents versus CBT 1 PBO

(other arms, when used, are not reviewed here).

RESULTS

Concurrent Cognitive-Behavior Therapy with Antidepressant Medication

As shown in Table 4, the pooled effect size for antidepressants was small at posttreat-

ment, with an NNT of 7.7. At follow-up (after medication discontinuation), the pooled

effect size was negative and in the negligible range. Thus, the addition of antidepres-

sants confers a smalladvantage over CBT monotherapy at posttreatment, although

this advantage is lost when medications are discontinued.

Antidepressant Medication by Diagnosis

There was no significant between-group heterogeneity according to diagnosis at post-

treatment (Q 5 6.32, P 5 .18) or at follow-up (Q 5 3.65, P 5 .30). Thus, the additive

effect of antidepressant medications does not appear to be significantly stronger for

any specific anxiety or depressive disorder(although a range is noted, from

g 5 0.17 for social phobia [SoP] to g 5 0.63 for posttraumatic stress disorder

[PTSD]). For anxiety disorders, the additive effect of antidepressants over PBO was

small,with an NNT of9.1 at posttreatment,and negative and negligible atfollow-

up. Similarly, for depressive disorders, the effect was small, with an NNT of 7.5 at post-

treatment, and negative and negligible at follow-up. Thus, the small benefit of additive

antidepressant medications that is eliminated on medication discontinuation is seen

across the anxiety and depressive disorders. Significant within-group heterogeneity

was found only forPD/A at posttreatment;visualinspection ofTable 1 suggests

that this was driven by a single study showing a treatment-attenuating effect of the

MAOI moclobemide.

Antidepressant medication by drug class

There was significant between-group heterogeneity according to medication at post-

treatment (Q 5 32.05, P 5 .001), although no significant between-group heterogeneity

was found at follow-up (Q 5 9.20, P 5 .10). At posttreatment, tricyclics were associ-

ated with a medium effect, with an NNT of 5.2. SSRIs/SNRIs were associated with a

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

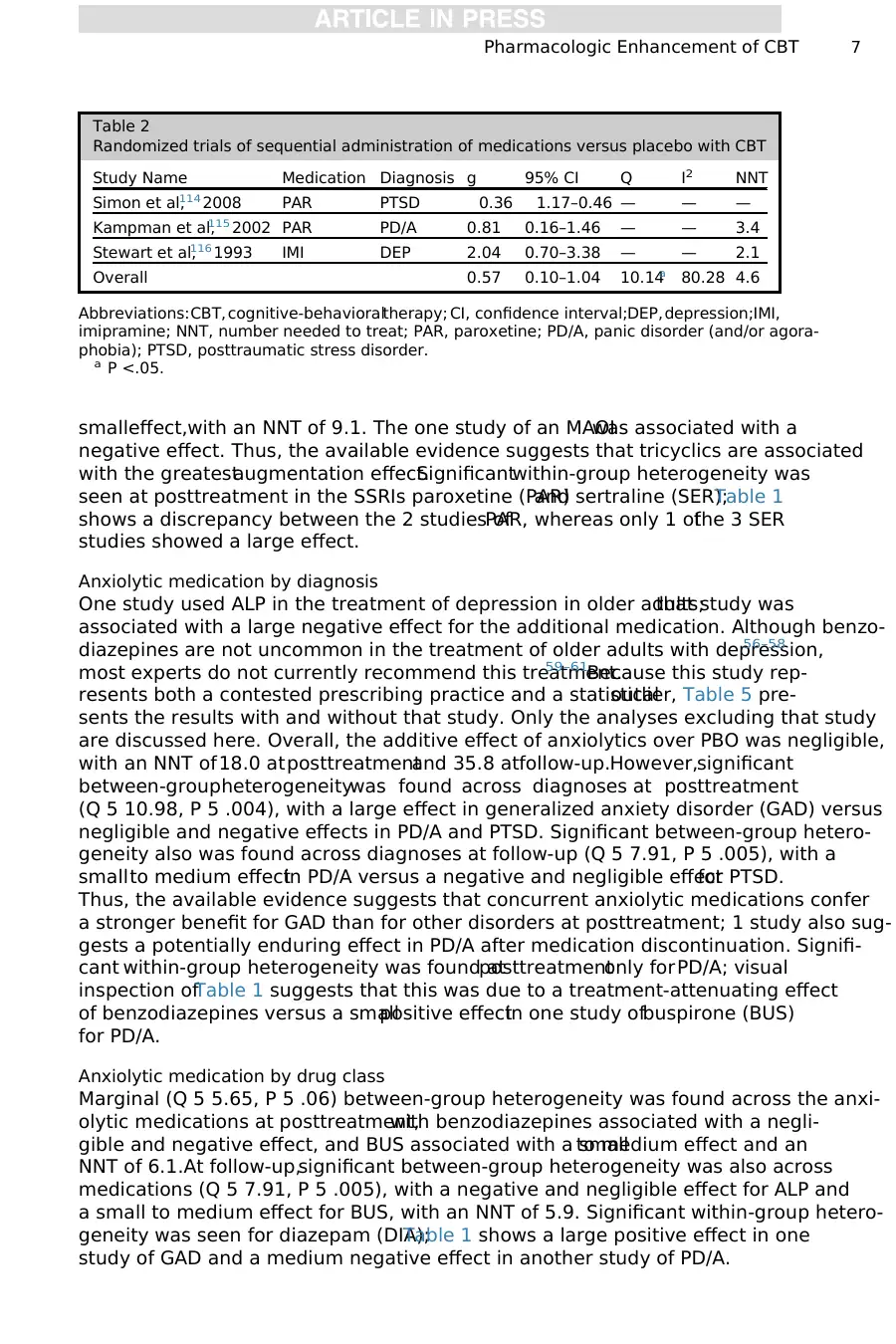

Table 1

Randomized trials of concurrent CBT with medication versus concurrent CBT with pill placebo

Study Name Medication Diagnosis

Posttreatment Follow-up

g 95% CI g 95% CI

Appleby et al,78 1997a FLU DEP 0.35 0.01–0.70 — —

Barlow et al,79 2000b IMI PD/A 0.71 0.35–1.06 0.23 0.57–0.12

Bellack et al,80 1981 AMI DEP 0.04 0.42–0.51 — —

Beutler et al,81 1987 ALP DEP 1.06 1.67

to 0.45

0.14 0.66–0.38

Blomhoff et al,82 2001;

Haug et al,83 2003

SER SoP 0.16 0.35–1.06 0.34 0.65 to 0.03

Bond et al,84 2002 BUS GAD 0.71 0.10–1.53 — —

Chaudhry et al,85 1998 AMN DEP 0.73 0.30–1.16 — —

Clark et al,86 2003 FLU SoP 0.28 0.33–0.89 — —

Cohen et al,87 2007 SER PTSD 0.28 0.18–0.75 — —

Cottraux et al,88 1990;

Cottraux et al,89 1993

FLV OCD 0.42 0.27–1.12 0.38 0.32–1.10

Cottraux et al,90 1995 BUS PD/A 0.38 0.10–1.53 0.44 0.10–0.77

Davidson et al,91 2004 FLU SoP 0.02 0.28–0.23 — —

de Beurs et al,92 1995;

de Beurs et al,93 1999

FLV PD/A 1.50 0.85–2.16 0.28 0.36–0.93

Echeburua et al,94 1993 ALP PD/A 0.11 1.04–0.82 — —

Fahy et al,95 1992 CMI PD/A 1.10 0.45–1.74 — —

Fahy et al,95 1992 LOF PD/A 0.47 0.14–1.08 — —

Gingnell et al,96 2016 ESC SoP 0.43 0.10–1.08 — —

Hohagen et al,97 1998 FLV OCD 0.53 0.03–1.09 — —

Loerch et al,98 1999 MOC PD/A 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.44 0.88–0.00

Marks et al,99 1983 IMI PD/A 0.54 0.05–1.12 0.18 0.40–0.77

Murphy et al,100 1984;

Simons et al,101 1986

NOR DEP 0.26 0.29–0.82 0.36 0.47–1.18

Peter et al,102 2000 FLV OCD 0.78 0.09–1.48 — —

Power et al,103 1990 DIA GAD 1.02 0.36–1.68 — —

Ravindran et al,104 1999 SER DEP 0.87 0.39–1.77 — —

Roth et al,105 1987 IMI PD/A 0.74 0.39–1.77 — —

Rothbaum et al,106 2014 ALP PTSD 0.06 0.33–0.21 0.18 0.46–0.09

Schneier et al,107 2012 PAR PTSD 1.06 0.38–1.73 — —

Sharp et al,108 1996 FLV PD/A 0.16 0.36–0.68 — —

Stein et al,109 2000 PAR PD/A 0.20 0.29–0.68 — —

Storch et al,110 2013 SER OCD 0.07 0.21–0.35 — —

Telch et al,111 1985 IMI PD/A 1.47 0.77–2.18 — —

Wardle et al,112 1994 DIA PD/A 0.63 1.13

to 0.12

— —

Wilson,113 1982 AMI DEP 0.16 0.76–0.44 0.43 1.03–0.18

P<.05.

Abbreviations: ALP, alprazolam; AMI, amitriptyline; AMN, amineptine; BUS, buspirone; CBT,

cognitive-behavioraltherapy;CI, confidence interval;CMI, clomipramine;DEP,depression;DIA,

diazepam; ESC, escitalopram; FLU, fluoxetine; FLV, fluvoxamine; GAD, generalized anxiety disor-

der; IMI, imipramine; LOF, lofepramine; MOC, moclobemide; NOR, nortriptyline; OCD, obsessive-

compulsive disorder; PAR, paroxetine; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttrau-

matic stress disorder; SER, sertraline; SoP, social phobia; —, no data.

a The 6-session CBT was included.

b The postmaintenance interview was included.

6

Randomized trials of concurrent CBT with medication versus concurrent CBT with pill placebo

Study Name Medication Diagnosis

Posttreatment Follow-up

g 95% CI g 95% CI

Appleby et al,78 1997a FLU DEP 0.35 0.01–0.70 — —

Barlow et al,79 2000b IMI PD/A 0.71 0.35–1.06 0.23 0.57–0.12

Bellack et al,80 1981 AMI DEP 0.04 0.42–0.51 — —

Beutler et al,81 1987 ALP DEP 1.06 1.67

to 0.45

0.14 0.66–0.38

Blomhoff et al,82 2001;

Haug et al,83 2003

SER SoP 0.16 0.35–1.06 0.34 0.65 to 0.03

Bond et al,84 2002 BUS GAD 0.71 0.10–1.53 — —

Chaudhry et al,85 1998 AMN DEP 0.73 0.30–1.16 — —

Clark et al,86 2003 FLU SoP 0.28 0.33–0.89 — —

Cohen et al,87 2007 SER PTSD 0.28 0.18–0.75 — —

Cottraux et al,88 1990;

Cottraux et al,89 1993

FLV OCD 0.42 0.27–1.12 0.38 0.32–1.10

Cottraux et al,90 1995 BUS PD/A 0.38 0.10–1.53 0.44 0.10–0.77

Davidson et al,91 2004 FLU SoP 0.02 0.28–0.23 — —

de Beurs et al,92 1995;

de Beurs et al,93 1999

FLV PD/A 1.50 0.85–2.16 0.28 0.36–0.93

Echeburua et al,94 1993 ALP PD/A 0.11 1.04–0.82 — —

Fahy et al,95 1992 CMI PD/A 1.10 0.45–1.74 — —

Fahy et al,95 1992 LOF PD/A 0.47 0.14–1.08 — —

Gingnell et al,96 2016 ESC SoP 0.43 0.10–1.08 — —

Hohagen et al,97 1998 FLV OCD 0.53 0.03–1.09 — —

Loerch et al,98 1999 MOC PD/A 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.44 0.88–0.00

Marks et al,99 1983 IMI PD/A 0.54 0.05–1.12 0.18 0.40–0.77

Murphy et al,100 1984;

Simons et al,101 1986

NOR DEP 0.26 0.29–0.82 0.36 0.47–1.18

Peter et al,102 2000 FLV OCD 0.78 0.09–1.48 — —

Power et al,103 1990 DIA GAD 1.02 0.36–1.68 — —

Ravindran et al,104 1999 SER DEP 0.87 0.39–1.77 — —

Roth et al,105 1987 IMI PD/A 0.74 0.39–1.77 — —

Rothbaum et al,106 2014 ALP PTSD 0.06 0.33–0.21 0.18 0.46–0.09

Schneier et al,107 2012 PAR PTSD 1.06 0.38–1.73 — —

Sharp et al,108 1996 FLV PD/A 0.16 0.36–0.68 — —

Stein et al,109 2000 PAR PD/A 0.20 0.29–0.68 — —

Storch et al,110 2013 SER OCD 0.07 0.21–0.35 — —

Telch et al,111 1985 IMI PD/A 1.47 0.77–2.18 — —

Wardle et al,112 1994 DIA PD/A 0.63 1.13

to 0.12

— —

Wilson,113 1982 AMI DEP 0.16 0.76–0.44 0.43 1.03–0.18

P<.05.

Abbreviations: ALP, alprazolam; AMI, amitriptyline; AMN, amineptine; BUS, buspirone; CBT,

cognitive-behavioraltherapy;CI, confidence interval;CMI, clomipramine;DEP,depression;DIA,

diazepam; ESC, escitalopram; FLU, fluoxetine; FLV, fluvoxamine; GAD, generalized anxiety disor-

der; IMI, imipramine; LOF, lofepramine; MOC, moclobemide; NOR, nortriptyline; OCD, obsessive-

compulsive disorder; PAR, paroxetine; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttrau-

matic stress disorder; SER, sertraline; SoP, social phobia; —, no data.

a The 6-session CBT was included.

b The postmaintenance interview was included.

6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

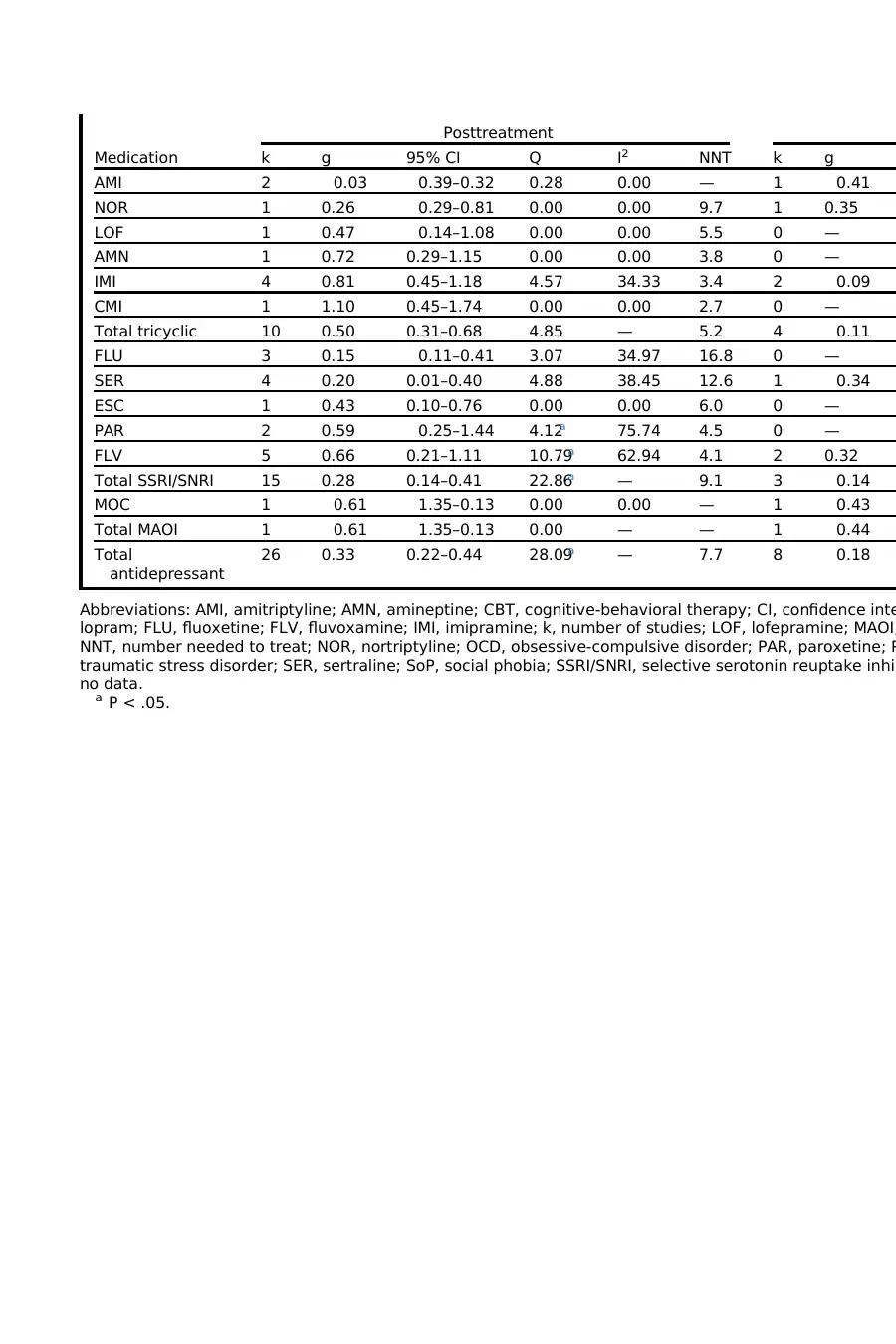

smalleffect,with an NNT of 9.1. The one study of an MAOIwas associated with a

negative effect. Thus, the available evidence suggests that tricyclics are associated

with the greatestaugmentation effect.Significantwithin-group heterogeneity was

seen at posttreatment in the SSRIs paroxetine (PAR)and sertraline (SER);Table 1

shows a discrepancy between the 2 studies ofPAR, whereas only 1 ofthe 3 SER

studies showed a large effect.

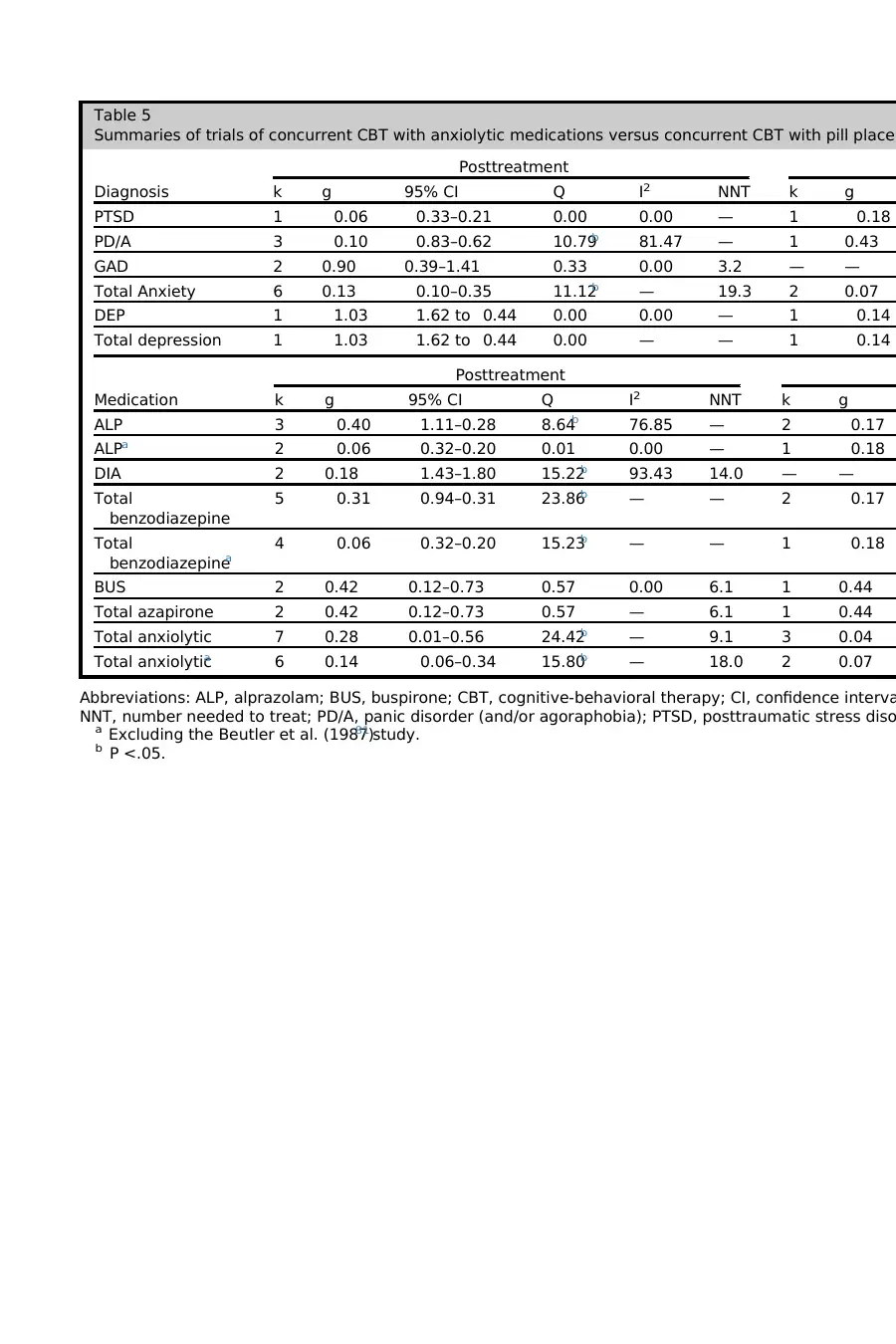

Anxiolytic medication by diagnosis

One study used ALP in the treatment of depression in older adults;that study was

associated with a large negative effect for the additional medication. Although benzo-

diazepines are not uncommon in the treatment of older adults with depression,56–58

most experts do not currently recommend this treatment.59–61Because this study rep-

resents both a contested prescribing practice and a statisticaloutlier, Table 5 pre-

sents the results with and without that study. Only the analyses excluding that study

are discussed here. Overall, the additive effect of anxiolytics over PBO was negligible,

with an NNT of18.0 atposttreatmentand 35.8 atfollow-up.However,significant

between-groupheterogeneitywas found across diagnoses at posttreatment

(Q 5 10.98, P 5 .004), with a large effect in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) versus

negligible and negative effects in PD/A and PTSD. Significant between-group hetero-

geneity also was found across diagnoses at follow-up (Q 5 7.91, P 5 .005), with a

smallto medium effectin PD/A versus a negative and negligible effectfor PTSD.

Thus, the available evidence suggests that concurrent anxiolytic medications confer

a stronger benefit for GAD than for other disorders at posttreatment; 1 study also sug-

gests a potentially enduring effect in PD/A after medication discontinuation. Signifi-

cant within-group heterogeneity was found atposttreatmentonly forPD/A; visual

inspection ofTable 1 suggests that this was due to a treatment-attenuating effect

of benzodiazepines versus a smallpositive effectin one study ofbuspirone (BUS)

for PD/A.

Anxiolytic medication by drug class

Marginal (Q 5 5.65, P 5 .06) between-group heterogeneity was found across the anxi-

olytic medications at posttreatment,with benzodiazepines associated with a negli-

gible and negative effect, and BUS associated with a smallto medium effect and an

NNT of 6.1.At follow-up,significant between-group heterogeneity was also across

medications (Q 5 7.91, P 5 .005), with a negative and negligible effect for ALP and

a small to medium effect for BUS, with an NNT of 5.9. Significant within-group hetero-

geneity was seen for diazepam (DIA);Table 1 shows a large positive effect in one

study of GAD and a medium negative effect in another study of PD/A.

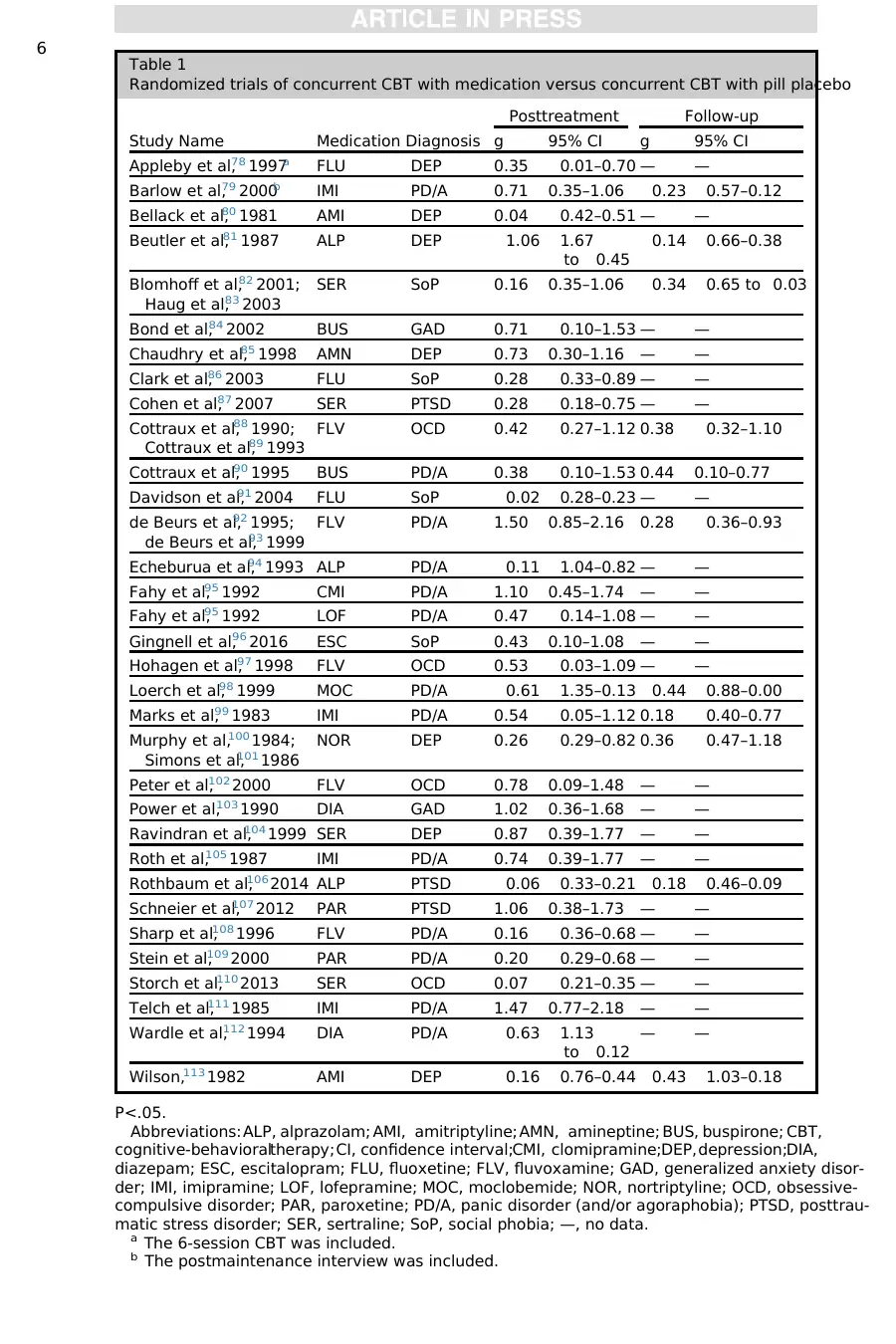

Table 2

Randomized trials of sequential administration of medications versus placebo with CBT

Study Name Medication Diagnosis g 95% CI Q I2 NNT

Simon et al,114 2008 PAR PTSD 0.36 1.17–0.46 — — —

Kampman et al,115 2002 PAR PD/A 0.81 0.16–1.46 — — 3.4

Stewart et al,116 1993 IMI DEP 2.04 0.70–3.38 — — 2.1

Overall 0.57 0.10–1.04 10.14a 80.28 4.6

Abbreviations:CBT, cognitive-behavioraltherapy; CI, confidence interval;DEP,depression;IMI,

imipramine; NNT, number needed to treat; PAR, paroxetine; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agora-

phobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

a P <.05.

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 7

negative effect. Thus, the available evidence suggests that tricyclics are associated

with the greatestaugmentation effect.Significantwithin-group heterogeneity was

seen at posttreatment in the SSRIs paroxetine (PAR)and sertraline (SER);Table 1

shows a discrepancy between the 2 studies ofPAR, whereas only 1 ofthe 3 SER

studies showed a large effect.

Anxiolytic medication by diagnosis

One study used ALP in the treatment of depression in older adults;that study was

associated with a large negative effect for the additional medication. Although benzo-

diazepines are not uncommon in the treatment of older adults with depression,56–58

most experts do not currently recommend this treatment.59–61Because this study rep-

resents both a contested prescribing practice and a statisticaloutlier, Table 5 pre-

sents the results with and without that study. Only the analyses excluding that study

are discussed here. Overall, the additive effect of anxiolytics over PBO was negligible,

with an NNT of18.0 atposttreatmentand 35.8 atfollow-up.However,significant

between-groupheterogeneitywas found across diagnoses at posttreatment

(Q 5 10.98, P 5 .004), with a large effect in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) versus

negligible and negative effects in PD/A and PTSD. Significant between-group hetero-

geneity also was found across diagnoses at follow-up (Q 5 7.91, P 5 .005), with a

smallto medium effectin PD/A versus a negative and negligible effectfor PTSD.

Thus, the available evidence suggests that concurrent anxiolytic medications confer

a stronger benefit for GAD than for other disorders at posttreatment; 1 study also sug-

gests a potentially enduring effect in PD/A after medication discontinuation. Signifi-

cant within-group heterogeneity was found atposttreatmentonly forPD/A; visual

inspection ofTable 1 suggests that this was due to a treatment-attenuating effect

of benzodiazepines versus a smallpositive effectin one study ofbuspirone (BUS)

for PD/A.

Anxiolytic medication by drug class

Marginal (Q 5 5.65, P 5 .06) between-group heterogeneity was found across the anxi-

olytic medications at posttreatment,with benzodiazepines associated with a negli-

gible and negative effect, and BUS associated with a smallto medium effect and an

NNT of 6.1.At follow-up,significant between-group heterogeneity was also across

medications (Q 5 7.91, P 5 .005), with a negative and negligible effect for ALP and

a small to medium effect for BUS, with an NNT of 5.9. Significant within-group hetero-

geneity was seen for diazepam (DIA);Table 1 shows a large positive effect in one

study of GAD and a medium negative effect in another study of PD/A.

Table 2

Randomized trials of sequential administration of medications versus placebo with CBT

Study Name Medication Diagnosis g 95% CI Q I2 NNT

Simon et al,114 2008 PAR PTSD 0.36 1.17–0.46 — — —

Kampman et al,115 2002 PAR PD/A 0.81 0.16–1.46 — — 3.4

Stewart et al,116 1993 IMI DEP 2.04 0.70–3.38 — — 2.1

Overall 0.57 0.10–1.04 10.14a 80.28 4.6

Abbreviations:CBT, cognitive-behavioraltherapy; CI, confidence interval;DEP,depression;IMI,

imipramine; NNT, number needed to treat; PAR, paroxetine; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agora-

phobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

a P <.05.

Pharmacologic Enhancement of CBT 7

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Medication for Patients Nonresponsive to

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Monotherapy

As shown in Table 2, the 3 controlled trials of medications versus PBO for CBT non-

responders showed a medium to large advantage overallfor medications, although

Table 3

Randomized trials of concurrent CBT with novel agents versus concurrent CBT with pill

placebo

Study Name Medication Diagnosis

Posttreatment Follow-up

g 95% CI g 95% CI

Acheson et al,117 2015 OXT SpP 0.78 1.36 to 0.19 — —

Andersson et al,118 2015 DCS OCD 0.33 0.02–0.67 0.12 0.23–0.46

de Kleine et al,119 2012 DCS PTSD 1.80 1.40–2.20 0.27 0.06–0.61

Difede et al,120 2014 DCS PTSD 0.83 0.03–1.62 1.42 0.57–2.28

Farrell et al,121 2013 DCS OCD 0.21 0.69–1.12 0.72 0.22–1.66

Guastella et al,122 2008 DCS SoP 0.60 0.29–0.90 0.49 0.18–0.79

Guastella et al,123 2009 OXT SoP 0.31 0.75–0.13 0.41 0.94–0.13

Hofmann et al,124 2006 DCS SoP 0.57 0.04–1.10 0.84 0.25–1.43

Hofmann et al,125 2013 DCS SoP 0.25 0.04–0.46 0.12 0.33–0.10

Kushner et al,126 2007 DCS OCD 0.18 0.86–0.50 0.41 1.09–0.28

Litz et al,127 2012 DCS PTSD 0.93 1.48 to 0.37 0.37 0.91–0.16

Mataix-Cols et al,128 2014 DCS OCD 0.23 0.50–0.97 0.08 0.66–0.81

Meyerbroeker et al,129

2012

YOH SpP 0.21 0.20–0.62 — —

Nations et al,38 2012 ORG PD/A 0.25 0.14–0.65 0.73 0.33–1.14

Nave et al,130 2012 DCS SpP 0.42 0.43–1.26 — —

Otto et al,131 2010 DCS PD/A 1.08 0.31–1.86 0.79 0.04–1.54

Otto et al,132 2016 DCS PD/A 0.32 0.03–0.62 — —

Powers et al,133 2009 YOH SpP 0.17 0.39–0.72 1.40 0.78–2.02

Ressler et al,134 2004 DCS SpP 1.02 0.45–1.59 — —

Rapee et al,135 2016 DCS Mix 0.09 0.29–0.47 — —

Rothbaum et al,106 2014 DCS PTSD 0.10 0.37–0.16 0.06 0.21–0.32

Scheeringa and

Weems,136 2014

DCS PTSD 0.06 0.57–0.46 0.09 0.60–0.42

Siegmund et al,73 2011 DCS PD/A 0.23 0.39–0.84 — —

Smits et al,137 2014 YOH SoP 0.81 0.18–1.44 — —

Storch et al,138 2007 DCS OCD 0.32 0.87–0.23 0.89 1.15

to 0.03

Storch et al,139 2010 DCS OCD 0.49 0.22–1.20 — —

Storch et al,140 2016 DCS OCD 0.13 0.20–0.46 — —

Tart et al,141 2013 DCS SpP 0.00 0.50–0.50 0.15 0.65–0.36

Telch et al,142 2014 MB SpP — — 0.36 0.24–0.96

Wilhelm et al,143 2008 DCS OCD 1.06 0.21–1.91 1.09 0.23–1.92

Zoellner et al,144 2017 MB PTSD 0.01 0.49–0.48 0.71 0.20–1.20

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interval; DCS,D-cycloserine; MB,

methylene blue; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ORG, Org 25,935; OXT, oxytocin; PD/A, panic

disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SoP, social phobia; SpP, specific

phobia; YOH, yohimbine; —, no data.

Tolin8

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Monotherapy

As shown in Table 2, the 3 controlled trials of medications versus PBO for CBT non-

responders showed a medium to large advantage overallfor medications, although

Table 3

Randomized trials of concurrent CBT with novel agents versus concurrent CBT with pill

placebo

Study Name Medication Diagnosis

Posttreatment Follow-up

g 95% CI g 95% CI

Acheson et al,117 2015 OXT SpP 0.78 1.36 to 0.19 — —

Andersson et al,118 2015 DCS OCD 0.33 0.02–0.67 0.12 0.23–0.46

de Kleine et al,119 2012 DCS PTSD 1.80 1.40–2.20 0.27 0.06–0.61

Difede et al,120 2014 DCS PTSD 0.83 0.03–1.62 1.42 0.57–2.28

Farrell et al,121 2013 DCS OCD 0.21 0.69–1.12 0.72 0.22–1.66

Guastella et al,122 2008 DCS SoP 0.60 0.29–0.90 0.49 0.18–0.79

Guastella et al,123 2009 OXT SoP 0.31 0.75–0.13 0.41 0.94–0.13

Hofmann et al,124 2006 DCS SoP 0.57 0.04–1.10 0.84 0.25–1.43

Hofmann et al,125 2013 DCS SoP 0.25 0.04–0.46 0.12 0.33–0.10

Kushner et al,126 2007 DCS OCD 0.18 0.86–0.50 0.41 1.09–0.28

Litz et al,127 2012 DCS PTSD 0.93 1.48 to 0.37 0.37 0.91–0.16

Mataix-Cols et al,128 2014 DCS OCD 0.23 0.50–0.97 0.08 0.66–0.81

Meyerbroeker et al,129

2012

YOH SpP 0.21 0.20–0.62 — —

Nations et al,38 2012 ORG PD/A 0.25 0.14–0.65 0.73 0.33–1.14

Nave et al,130 2012 DCS SpP 0.42 0.43–1.26 — —

Otto et al,131 2010 DCS PD/A 1.08 0.31–1.86 0.79 0.04–1.54

Otto et al,132 2016 DCS PD/A 0.32 0.03–0.62 — —

Powers et al,133 2009 YOH SpP 0.17 0.39–0.72 1.40 0.78–2.02

Ressler et al,134 2004 DCS SpP 1.02 0.45–1.59 — —

Rapee et al,135 2016 DCS Mix 0.09 0.29–0.47 — —

Rothbaum et al,106 2014 DCS PTSD 0.10 0.37–0.16 0.06 0.21–0.32

Scheeringa and

Weems,136 2014

DCS PTSD 0.06 0.57–0.46 0.09 0.60–0.42

Siegmund et al,73 2011 DCS PD/A 0.23 0.39–0.84 — —

Smits et al,137 2014 YOH SoP 0.81 0.18–1.44 — —

Storch et al,138 2007 DCS OCD 0.32 0.87–0.23 0.89 1.15

to 0.03

Storch et al,139 2010 DCS OCD 0.49 0.22–1.20 — —

Storch et al,140 2016 DCS OCD 0.13 0.20–0.46 — —

Tart et al,141 2013 DCS SpP 0.00 0.50–0.50 0.15 0.65–0.36

Telch et al,142 2014 MB SpP — — 0.36 0.24–0.96

Wilhelm et al,143 2008 DCS OCD 1.06 0.21–1.91 1.09 0.23–1.92

Zoellner et al,144 2017 MB PTSD 0.01 0.49–0.48 0.71 0.20–1.20

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interval; DCS,D-cycloserine; MB,

methylene blue; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ORG, Org 25,935; OXT, oxytocin; PD/A, panic

disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SoP, social phobia; SpP, specific

phobia; YOH, yohimbine; —, no data.

Tolin8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 4

Summaries of trials of concurrent CBT with antidepressant medications versus concurrent CBT with pill p

Diagnosis

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g 95

SoP 4 0.17 0.01–0.34 4.81 37.64 14.8 1 0.34

OCD 4 0.36 0.02–0.69 5.08 41.00 7.1 1 0.38

PTSD 2 0.63 0.12–1.39 3.42 70.79 4.2 0 — —

PD/A 10 0.61 0.26–0.97 32.02a 71.89 4.4 4 0.12

Total anxiety 20 0.28 0.09–0.41 45.34a — 9.1 6 0.17

DEP 6 0.34 0.06–0.62 9.96 49.78 7.5 2 0.08

Total depression 6 0.34 0.06–0.62 9.96 — 7.5 2 0.08

Summaries of trials of concurrent CBT with antidepressant medications versus concurrent CBT with pill p

Diagnosis

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g 95

SoP 4 0.17 0.01–0.34 4.81 37.64 14.8 1 0.34

OCD 4 0.36 0.02–0.69 5.08 41.00 7.1 1 0.38

PTSD 2 0.63 0.12–1.39 3.42 70.79 4.2 0 — —

PD/A 10 0.61 0.26–0.97 32.02a 71.89 4.4 4 0.12

Total anxiety 20 0.28 0.09–0.41 45.34a — 9.1 6 0.17

DEP 6 0.34 0.06–0.62 9.96 49.78 7.5 2 0.08

Total depression 6 0.34 0.06–0.62 9.96 — 7.5 2 0.08

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Medication

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

AMI 2 0.03 0.39–0.32 0.28 0.00 — 1 0.41

NOR 1 0.26 0.29–0.81 0.00 0.00 9.7 1 0.35

LOF 1 0.47 0.14–1.08 0.00 0.00 5.5 0 —

AMN 1 0.72 0.29–1.15 0.00 0.00 3.8 0 —

IMI 4 0.81 0.45–1.18 4.57 34.33 3.4 2 0.09

CMI 1 1.10 0.45–1.74 0.00 0.00 2.7 0 —

Total tricyclic 10 0.50 0.31–0.68 4.85 — 5.2 4 0.11

FLU 3 0.15 0.11–0.41 3.07 34.97 16.8 0 —

SER 4 0.20 0.01–0.40 4.88 38.45 12.6 1 0.34

ESC 1 0.43 0.10–0.76 0.00 0.00 6.0 0 —

PAR 2 0.59 0.25–1.44 4.12a 75.74 4.5 0 —

FLV 5 0.66 0.21–1.11 10.79a 62.94 4.1 2 0.32

Total SSRI/SNRI 15 0.28 0.14–0.41 22.86a — 9.1 3 0.14

MOC 1 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.43

Total MAOI 1 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.00 — — 1 0.44

Total

antidepressant

26 0.33 0.22–0.44 28.09a — 7.7 8 0.18

Abbreviations: AMI, amitriptyline; AMN, amineptine; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence inte

lopram; FLU, fluoxetine; FLV, fluvoxamine; IMI, imipramine; k, number of studies; LOF, lofepramine; MAOI,

NNT, number needed to treat; NOR, nortriptyline; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PAR, paroxetine; P

traumatic stress disorder; SER, sertraline; SoP, social phobia; SSRI/SNRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhib

no data.

a P < .05.

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

AMI 2 0.03 0.39–0.32 0.28 0.00 — 1 0.41

NOR 1 0.26 0.29–0.81 0.00 0.00 9.7 1 0.35

LOF 1 0.47 0.14–1.08 0.00 0.00 5.5 0 —

AMN 1 0.72 0.29–1.15 0.00 0.00 3.8 0 —

IMI 4 0.81 0.45–1.18 4.57 34.33 3.4 2 0.09

CMI 1 1.10 0.45–1.74 0.00 0.00 2.7 0 —

Total tricyclic 10 0.50 0.31–0.68 4.85 — 5.2 4 0.11

FLU 3 0.15 0.11–0.41 3.07 34.97 16.8 0 —

SER 4 0.20 0.01–0.40 4.88 38.45 12.6 1 0.34

ESC 1 0.43 0.10–0.76 0.00 0.00 6.0 0 —

PAR 2 0.59 0.25–1.44 4.12a 75.74 4.5 0 —

FLV 5 0.66 0.21–1.11 10.79a 62.94 4.1 2 0.32

Total SSRI/SNRI 15 0.28 0.14–0.41 22.86a — 9.1 3 0.14

MOC 1 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.43

Total MAOI 1 0.61 1.35–0.13 0.00 — — 1 0.44

Total

antidepressant

26 0.33 0.22–0.44 28.09a — 7.7 8 0.18

Abbreviations: AMI, amitriptyline; AMN, amineptine; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence inte

lopram; FLU, fluoxetine; FLV, fluvoxamine; IMI, imipramine; k, number of studies; LOF, lofepramine; MAOI,

NNT, number needed to treat; NOR, nortriptyline; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PAR, paroxetine; P

traumatic stress disorder; SER, sertraline; SoP, social phobia; SSRI/SNRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhib

no data.

a P < .05.

Table 5

Summaries of trials of concurrent CBT with anxiolytic medications versus concurrent CBT with pill placeb

Diagnosis

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

PTSD 1 0.06 0.33–0.21 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.18

PD/A 3 0.10 0.83–0.62 10.79b 81.47 — 1 0.43

GAD 2 0.90 0.39–1.41 0.33 0.00 3.2 — —

Total Anxiety 6 0.13 0.10–0.35 11.12b — 19.3 2 0.07

DEP 1 1.03 1.62 to 0.44 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.14

Total depression 1 1.03 1.62 to 0.44 0.00 — — 1 0.14

Medication

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

ALP 3 0.40 1.11–0.28 8.64b 76.85 — 2 0.17

ALPa 2 0.06 0.32–0.20 0.01 0.00 — 1 0.18

DIA 2 0.18 1.43–1.80 15.22b 93.43 14.0 — —

Total

benzodiazepine

5 0.31 0.94–0.31 23.86b — — 2 0.17

Total

benzodiazepinea

4 0.06 0.32–0.20 15.23b — — 1 0.18

BUS 2 0.42 0.12–0.73 0.57 0.00 6.1 1 0.44

Total azapirone 2 0.42 0.12–0.73 0.57 — 6.1 1 0.44

Total anxiolytic 7 0.28 0.01–0.56 24.42b — 9.1 3 0.04

Total anxiolytica 6 0.14 0.06–0.34 15.80b — 18.0 2 0.07

Abbreviations: ALP, alprazolam; BUS, buspirone; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interva

NNT, number needed to treat; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress diso

a Excluding the Beutler et al. (1987)81 study.

b P <.05.

Summaries of trials of concurrent CBT with anxiolytic medications versus concurrent CBT with pill placeb

Diagnosis

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

PTSD 1 0.06 0.33–0.21 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.18

PD/A 3 0.10 0.83–0.62 10.79b 81.47 — 1 0.43

GAD 2 0.90 0.39–1.41 0.33 0.00 3.2 — —

Total Anxiety 6 0.13 0.10–0.35 11.12b — 19.3 2 0.07

DEP 1 1.03 1.62 to 0.44 0.00 0.00 — 1 0.14

Total depression 1 1.03 1.62 to 0.44 0.00 — — 1 0.14

Medication

Posttreatment

k g 95% CI Q I2 NNT k g

ALP 3 0.40 1.11–0.28 8.64b 76.85 — 2 0.17

ALPa 2 0.06 0.32–0.20 0.01 0.00 — 1 0.18

DIA 2 0.18 1.43–1.80 15.22b 93.43 14.0 — —

Total

benzodiazepine

5 0.31 0.94–0.31 23.86b — — 2 0.17

Total

benzodiazepinea

4 0.06 0.32–0.20 15.23b — — 1 0.18

BUS 2 0.42 0.12–0.73 0.57 0.00 6.1 1 0.44

Total azapirone 2 0.42 0.12–0.73 0.57 — 6.1 1 0.44

Total anxiolytic 7 0.28 0.01–0.56 24.42b — 9.1 3 0.04

Total anxiolytica 6 0.14 0.06–0.34 15.80b — 18.0 2 0.07

Abbreviations: ALP, alprazolam; BUS, buspirone; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interva

NNT, number needed to treat; PD/A, panic disorder (and/or agoraphobia); PTSD, posttraumatic stress diso

a Excluding the Beutler et al. (1987)81 study.

b P <.05.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 25

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.