Applying the Lack of Fit Model to Reduce Gender Discrimination

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/03

|20

|14609

|25

Report

AI Summary

This report examines gender discrimination in the workplace, highlighting the persistence of gender inequalities and the significant role of gender bias. It introduces the lack of fit model as a framework for understanding how gender stereotypes and perceived job requirements create incongruity, leading to negative expectations about women's performance and biased employment decisions. The report explores intervention strategies to reduce these perceptions, including eliminating stereotype-based characterizations and breaking the link between expectations and biased evaluations. It discusses the importance of addressing the factors that drive gender discrimination, with a focus on organizational interventions to promote fair and equitable practices, providing insights into their potential impact and effectiveness. The report emphasizes the need for vigilance in monitoring the effects of these strategies and provides a theoretical context for understanding gender bias in evaluative decision-making.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218761587

Group Processes & Intergroup Relation

2018, Vol. 21(5) 725–744

© The Author(s) 2018

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1368430218761587

journals.sagepub.com/home/gpi

G

P

I

R

Group Processes &

Intergroup Relations

The past 50 years have been marked by consider-

able progressfor womenin the workplace,

reflected in increased labor force participation

rates and a shrinking wage gap (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, 2017). Yet, these advances can

sometimes be deceptive in their implications.

Although a holistic view of organizations might

suggest that gender parity has been achieved, a

segmented breakdown of professions, positions,

and industries offers a far less favorable picture.

Today, women remain underrepresented in many

prestigious and high-status jobs. They comprise

only 5.8% of S&P 500 CEOs (Catalyst, 2017)

and, in the United States, represent less than 20%

of technicalrolesin majortech companies

(Mundy, 2017) and 11% of tenured professors in

engineering (National Science Foundation, 2015).

Changes in the wage gap, too, have stalled (U.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017).

Although there are many possible contrib

tors to the perpetuation of gender inequality i

the workplace, research suggests that gender

criminationplaysa significantrole (Heilman,

2012). Organizations appear motivated to com

bat gender discrimination, with many publi

carrying out efforts to increase gender equ

Open about their lagging numbers, for exampl

Combatting gender discrimination:

A lack of fit framework

Madeline E. Heilman1 and Suzette Caleo2

Abstract

Gender inequalities in the workplace persist, and scholars point to gender discriminat

contributor. As organizations attempt to address this problem, we argue that theory c

on potential solutions. This paper discusses how the lack of fit model can be used by o

a framework to understand the process that facilitates gender discrimination in emplo

and to identify intervention strategies to combat it. We describe two sets of strategies

at reducing the perception that women are not suited for male-typed positions. The se

preventing the negative performance expectations that derive from this perception of

influencing evaluative judgments. Also included is a discussion of several unintentiona

that may follow from enacting these strategies. We conclude by arguing for the impor

interplay between theory and practice in targeting gender discrimination in the workp

Keywords

gender bias, gender discrimination, gender stereotypes, lack of fit

Paper received 11 May 2017; revised version accepted 2 February 2018

1New York University

2Louisiana State University

Corresponding author:

Madeline Heilman, Department of Psychology, New York

University, 6 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003, US

Email: madeline.heilman@nyu.edu

761587GPI0010.1177/1368430218761587Group Processe s & Intergroup Relations Heilman and Caleo

research-article2018

Article

Group Processes & Intergroup Relation

2018, Vol. 21(5) 725–744

© The Author(s) 2018

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1368430218761587

journals.sagepub.com/home/gpi

G

P

I

R

Group Processes &

Intergroup Relations

The past 50 years have been marked by consider-

able progressfor womenin the workplace,

reflected in increased labor force participation

rates and a shrinking wage gap (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, 2017). Yet, these advances can

sometimes be deceptive in their implications.

Although a holistic view of organizations might

suggest that gender parity has been achieved, a

segmented breakdown of professions, positions,

and industries offers a far less favorable picture.

Today, women remain underrepresented in many

prestigious and high-status jobs. They comprise

only 5.8% of S&P 500 CEOs (Catalyst, 2017)

and, in the United States, represent less than 20%

of technicalrolesin majortech companies

(Mundy, 2017) and 11% of tenured professors in

engineering (National Science Foundation, 2015).

Changes in the wage gap, too, have stalled (U.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017).

Although there are many possible contrib

tors to the perpetuation of gender inequality i

the workplace, research suggests that gender

criminationplaysa significantrole (Heilman,

2012). Organizations appear motivated to com

bat gender discrimination, with many publi

carrying out efforts to increase gender equ

Open about their lagging numbers, for exampl

Combatting gender discrimination:

A lack of fit framework

Madeline E. Heilman1 and Suzette Caleo2

Abstract

Gender inequalities in the workplace persist, and scholars point to gender discriminat

contributor. As organizations attempt to address this problem, we argue that theory c

on potential solutions. This paper discusses how the lack of fit model can be used by o

a framework to understand the process that facilitates gender discrimination in emplo

and to identify intervention strategies to combat it. We describe two sets of strategies

at reducing the perception that women are not suited for male-typed positions. The se

preventing the negative performance expectations that derive from this perception of

influencing evaluative judgments. Also included is a discussion of several unintentiona

that may follow from enacting these strategies. We conclude by arguing for the impor

interplay between theory and practice in targeting gender discrimination in the workp

Keywords

gender bias, gender discrimination, gender stereotypes, lack of fit

Paper received 11 May 2017; revised version accepted 2 February 2018

1New York University

2Louisiana State University

Corresponding author:

Madeline Heilman, Department of Psychology, New York

University, 6 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003, US

Email: madeline.heilman@nyu.edu

761587GPI0010.1177/1368430218761587Group Processe s & Intergroup Relations Heilman and Caleo

research-article2018

Article

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

726 Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

male-dominated companies in Silicon Valley have

recently pledged to dedicate millions of dollars to

efforts intended to create more inclusive climates

and improve the representation of women in

technology (Mundy, 2017). Yet, these attempts

are proving to be slow going (Isaac, 2015; Wells,

2016). Although more time is needed to deter-

mine if they have had their intended effect, it is

clear that overcoming discrimination is not a sim-

ple task.

Taking a proactive approach to combatting

genderdiscriminationis laudable.However,

intention does not always translate into effective-

ness. If organizations are to effectively address

the shortage of women in male-dominated posi-

tions, the interventions they design have the best

likelihood of succeeding if they take into account

the factors that drive gender discrimination and

target them directly. To this end, this paper draws

from the tenets of the lack of fit model (Heilman,

1983, 2001, 2012) to provide a framework for

identifying strategies for curtailing the effects of

gender stereotyping and gender bias on employ-

ment decisions.

We draw on the lack of fit model for several

reasons. First, it has been specifically tailored to

understand gender discrimination, which is argu-

ably distinct from other forms of discrimination

(Paluck & Green, 2009). Second, the ideas posed

by the model are widely studied and supported by

decades of research (Heilman, 2012), offering

assurance that the strategies we propose are both

theoretically and empirically grounded. Finally,

working from a single theory allows for a system-

atic approach to the design of organizational

intervention strategies. As we will discuss, the

lack of fit model specifies a process underlying

gender bias in evaluative decision making and is

suggestive of various conditions that determine

whether or not this process takes hold. It there-

fore enables a consideration of why and when

discriminatoryemploymentdecisionsoccur,

pointing to contributory factors that can become

the focal point for intervention.

We begin with an overview of the lack of fit

model and its key propositions, later describing

these propositions in more detail as we present

intervention strategies that derive from them. W

will review interventions that already are part o

the organizational arsenal and also propose new

interventions that emerge from a systematic co

sideration of the theory. It is our hope tha

putting these interventions into a theoretical co

text we will provide insight into what they migh

accomplish and when they will be most effectiv

expanding the choices open to organizations

Lastly, we discuss unintended consequences th

could arise from these interventions, emphasizi

the need for vigilance in monitoring their effect

It is of note that our focus is on organization

as the instruments of change. We identify inter

ventions in which organizations can engage tha

impede the processes that perpetuate gender b

and give rise to gender discrimination, not thos

aimed at encouraging women themselves to con

front and overcome the biases they encount

Furthermore, the strategies we propose seek t

address gender discrimination in the formal eva

uative decisions made within organizations,

in the impromptu daily interactions and ass

ments that no doubt also affect women’s career

prospects.

The Lack of Fit Model

Almost 35 years have elapsed since the introdu

tion of the lack of fit model (Heilman, 1983), b

its propositionscontinueto ring true today.

According to the model, outcomes that are dis-

criminatory against women stem from a mis

match between the attributes that women a

thought to possess and the attributes seen as n

essary for success in male-typed positions a

fields. This resulting incongruity forms the basi

of negative expectations about women’s perfor

mance, which thereby bias the processing o

information and, consequently, facilitate discrim

natory behavior.

Central to the model is a consideration of gen

der stereotypes—preconceptions regarding w

men and women are like. Gender stereotypes p

tray men as agentic and women as commun

(Haines, Deaux, & Lofaro, 2016). Whereas m

are thought to be assertive, bold, and aggressiv

male-dominated companies in Silicon Valley have

recently pledged to dedicate millions of dollars to

efforts intended to create more inclusive climates

and improve the representation of women in

technology (Mundy, 2017). Yet, these attempts

are proving to be slow going (Isaac, 2015; Wells,

2016). Although more time is needed to deter-

mine if they have had their intended effect, it is

clear that overcoming discrimination is not a sim-

ple task.

Taking a proactive approach to combatting

genderdiscriminationis laudable.However,

intention does not always translate into effective-

ness. If organizations are to effectively address

the shortage of women in male-dominated posi-

tions, the interventions they design have the best

likelihood of succeeding if they take into account

the factors that drive gender discrimination and

target them directly. To this end, this paper draws

from the tenets of the lack of fit model (Heilman,

1983, 2001, 2012) to provide a framework for

identifying strategies for curtailing the effects of

gender stereotyping and gender bias on employ-

ment decisions.

We draw on the lack of fit model for several

reasons. First, it has been specifically tailored to

understand gender discrimination, which is argu-

ably distinct from other forms of discrimination

(Paluck & Green, 2009). Second, the ideas posed

by the model are widely studied and supported by

decades of research (Heilman, 2012), offering

assurance that the strategies we propose are both

theoretically and empirically grounded. Finally,

working from a single theory allows for a system-

atic approach to the design of organizational

intervention strategies. As we will discuss, the

lack of fit model specifies a process underlying

gender bias in evaluative decision making and is

suggestive of various conditions that determine

whether or not this process takes hold. It there-

fore enables a consideration of why and when

discriminatoryemploymentdecisionsoccur,

pointing to contributory factors that can become

the focal point for intervention.

We begin with an overview of the lack of fit

model and its key propositions, later describing

these propositions in more detail as we present

intervention strategies that derive from them. W

will review interventions that already are part o

the organizational arsenal and also propose new

interventions that emerge from a systematic co

sideration of the theory. It is our hope tha

putting these interventions into a theoretical co

text we will provide insight into what they migh

accomplish and when they will be most effectiv

expanding the choices open to organizations

Lastly, we discuss unintended consequences th

could arise from these interventions, emphasizi

the need for vigilance in monitoring their effect

It is of note that our focus is on organization

as the instruments of change. We identify inter

ventions in which organizations can engage tha

impede the processes that perpetuate gender b

and give rise to gender discrimination, not thos

aimed at encouraging women themselves to con

front and overcome the biases they encount

Furthermore, the strategies we propose seek t

address gender discrimination in the formal eva

uative decisions made within organizations,

in the impromptu daily interactions and ass

ments that no doubt also affect women’s career

prospects.

The Lack of Fit Model

Almost 35 years have elapsed since the introdu

tion of the lack of fit model (Heilman, 1983), b

its propositionscontinueto ring true today.

According to the model, outcomes that are dis-

criminatory against women stem from a mis

match between the attributes that women a

thought to possess and the attributes seen as n

essary for success in male-typed positions a

fields. This resulting incongruity forms the basi

of negative expectations about women’s perfor

mance, which thereby bias the processing o

information and, consequently, facilitate discrim

natory behavior.

Central to the model is a consideration of gen

der stereotypes—preconceptions regarding w

men and women are like. Gender stereotypes p

tray men as agentic and women as commun

(Haines, Deaux, & Lofaro, 2016). Whereas m

are thought to be assertive, bold, and aggressiv

Heilman and Caleo 727

women are thought to be relationship-oriented,

nurturing, and kind. These stereotypical depictions

also tend to be oppositional, with both women and

men viewed as lacking what is thought to be most

prevalent in the other sex. Thus, women are seen

not only as communal but also as not agentic.

Stereotypic beliefs about men and women are both

widely and consistently held, and have proven to

be resistant to change despite decades of social

progress (Haines et al., 2016).

Genderstereotypescreatedifficultiesfor

womenpursuingtraditionallymale work,as

femalestereotypesare incompatiblewith the

attributes and behaviors thought necessary for

successin thosefields.In additionto being

numerically dominated by men, these male-typed

fields and occupations are conceived of as neces-

sitating stereotypically masculine attributes (Cejka

& Eagly, 1999; Johnson, Murphy, Zewdie, &

Reichard, 2008). Thus, in contrast to men, who

likely are advantaged by the overlap between per-

ceivedattributesand job requirements (Kray,

Galinsky, & Thompson, 2002; Ryan et al., 2016),

women are disadvantaged. The inconsistency, or

lack of fit, between stereotypes about women and

the perceived requirements for success in male-

typedpositionsleadsto the perceptionthat

women are not well suited for them, producing

negative expectations about their likely perfor-

mance. These expectations in turn lead to the

presumption that women lack the competence

necessary to do well in these positions and that

they are unlikely to succeed (Heilman, 2012).

Stereotype-based expectations about women’s

competence can bias the ways in which individu-

als make decisions about applicants and employ-

ees. They are self-perpetuating,skewing

information processing in a direction that vali-

dates decision makers’ initial stereotypic beliefs.

Thus, negativeperformanceexpectationscan

impact the kinds of information that evaluators

recall (Hollingshead & Fraidin, 2003; Martell,

1996) and attendto (Biernat,Fuegen,&

Kobrynowicz,2010),and can influencehow

informationis interpreted(Madera,Hebl, &

Martin, 2009). They also can affect how individu-

als weight and reconcile different sources and

typesof information(Norton,Vandello,&

Darley, 2004). These effects on information pr

cessing are fueled by ambiguity in the evaluat

process, which increases reliance on expectati

and thereforefacilitatescognitivedistortion

(Heilman & Haynes, 2008).

Because information processing is funda-

mental to a range of human resource manage

ment decisions (Murphy & Cleveland, 1995

the negativeperformanceexpectationsthat

arise from the perception of lack of fit betwee

what women are like and what is required

perform in a male-typed position are likely

promotegenderbias in evaluativedecision

making and prompt discrimination in recru

ment (Gaucher, Friesen, & Kay, 2011), selectio

(Biernat & Fuegen, 2001), performance

appraisal (Bauer & Baltes, 2002), promotio

(Lyness & Heilman, 2006), and compensati

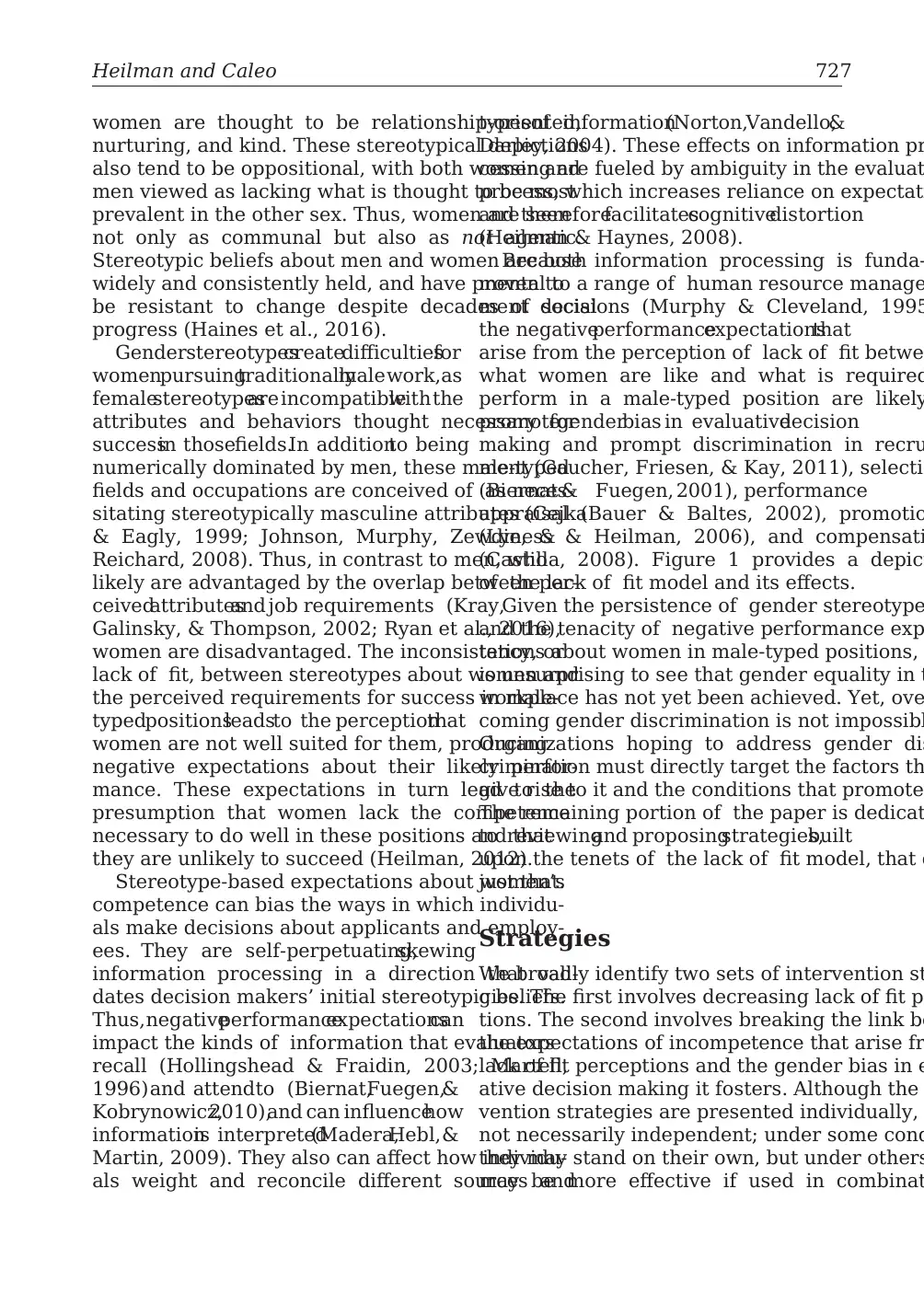

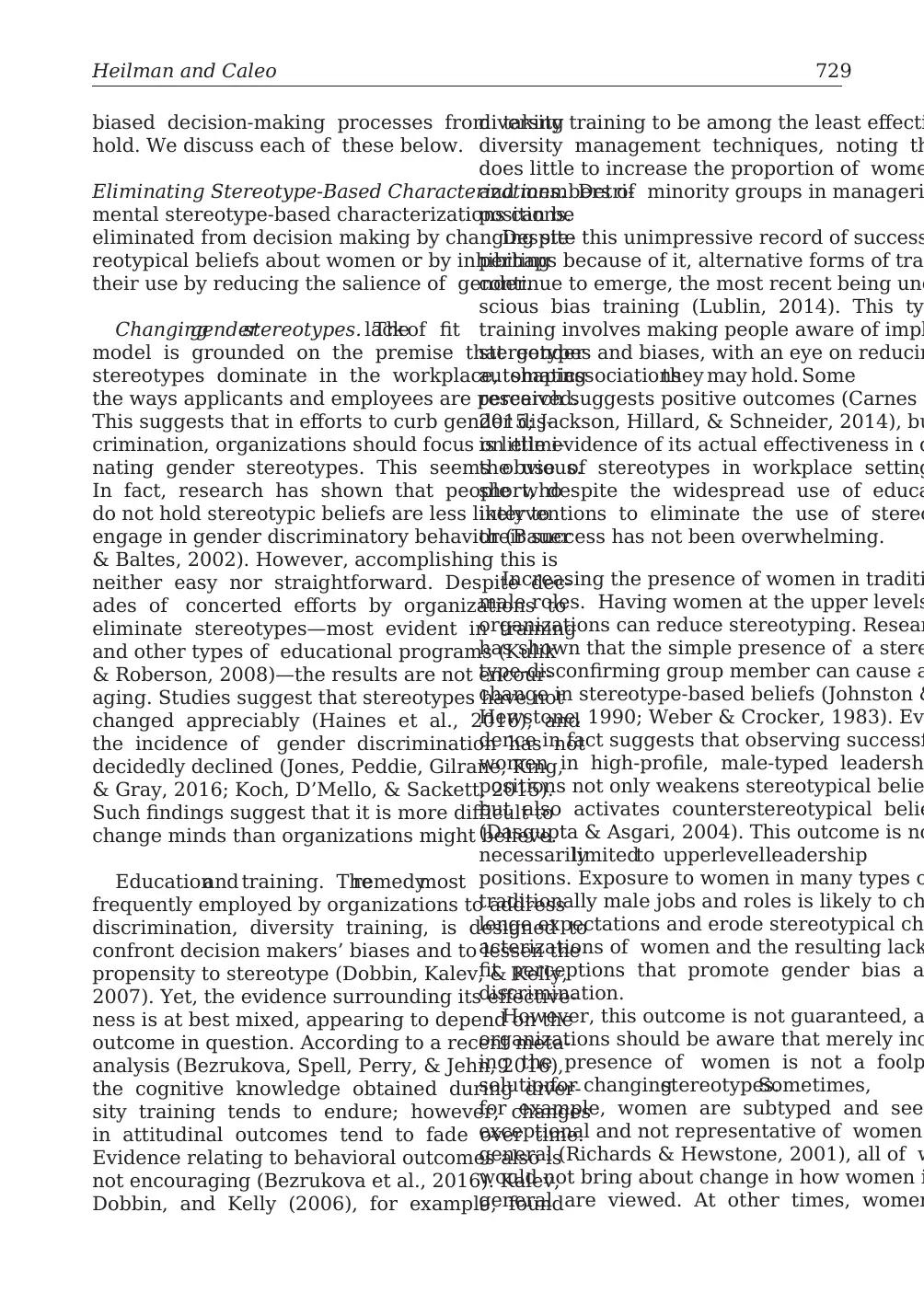

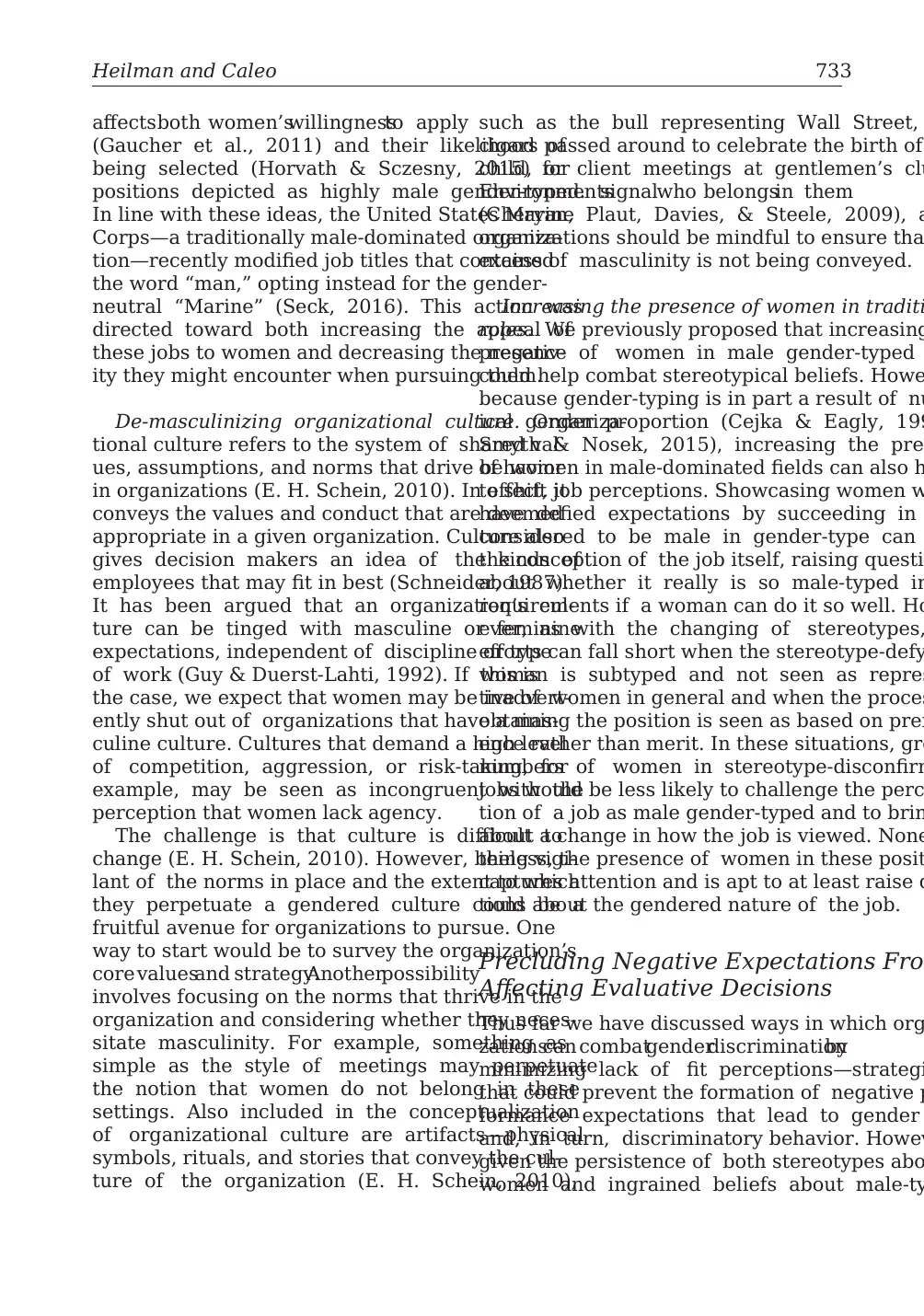

(Castilla, 2008). Figure 1 provides a depict

of the lack of fit model and its effects.

Given the persistence of gender stereotype

and the tenacity of negative performance exp

tations about women in male-typed positions,

is unsurprising to see that gender equality in t

workplace has not yet been achieved. Yet, ove

coming gender discrimination is not impossibl

Organizations hoping to address gender dis

crimination must directly target the factors th

give rise to it and the conditions that promote

The remaining portion of the paper is dedicat

to reviewingand proposingstrategies,built

upon the tenets of the lack of fit model, that d

just that.

Strategies

We broadly identify two sets of intervention st

gies. The first involves decreasing lack of fit pe

tions. The second involves breaking the link be

the expectations of incompetence that arise fr

lack of fit perceptions and the gender bias in e

ative decision making it fosters. Although the

vention strategies are presented individually,

not necessarily independent; under some cond

they may stand on their own, but under others

may be more effective if used in combinat

women are thought to be relationship-oriented,

nurturing, and kind. These stereotypical depictions

also tend to be oppositional, with both women and

men viewed as lacking what is thought to be most

prevalent in the other sex. Thus, women are seen

not only as communal but also as not agentic.

Stereotypic beliefs about men and women are both

widely and consistently held, and have proven to

be resistant to change despite decades of social

progress (Haines et al., 2016).

Genderstereotypescreatedifficultiesfor

womenpursuingtraditionallymale work,as

femalestereotypesare incompatiblewith the

attributes and behaviors thought necessary for

successin thosefields.In additionto being

numerically dominated by men, these male-typed

fields and occupations are conceived of as neces-

sitating stereotypically masculine attributes (Cejka

& Eagly, 1999; Johnson, Murphy, Zewdie, &

Reichard, 2008). Thus, in contrast to men, who

likely are advantaged by the overlap between per-

ceivedattributesand job requirements (Kray,

Galinsky, & Thompson, 2002; Ryan et al., 2016),

women are disadvantaged. The inconsistency, or

lack of fit, between stereotypes about women and

the perceived requirements for success in male-

typedpositionsleadsto the perceptionthat

women are not well suited for them, producing

negative expectations about their likely perfor-

mance. These expectations in turn lead to the

presumption that women lack the competence

necessary to do well in these positions and that

they are unlikely to succeed (Heilman, 2012).

Stereotype-based expectations about women’s

competence can bias the ways in which individu-

als make decisions about applicants and employ-

ees. They are self-perpetuating,skewing

information processing in a direction that vali-

dates decision makers’ initial stereotypic beliefs.

Thus, negativeperformanceexpectationscan

impact the kinds of information that evaluators

recall (Hollingshead & Fraidin, 2003; Martell,

1996) and attendto (Biernat,Fuegen,&

Kobrynowicz,2010),and can influencehow

informationis interpreted(Madera,Hebl, &

Martin, 2009). They also can affect how individu-

als weight and reconcile different sources and

typesof information(Norton,Vandello,&

Darley, 2004). These effects on information pr

cessing are fueled by ambiguity in the evaluat

process, which increases reliance on expectati

and thereforefacilitatescognitivedistortion

(Heilman & Haynes, 2008).

Because information processing is funda-

mental to a range of human resource manage

ment decisions (Murphy & Cleveland, 1995

the negativeperformanceexpectationsthat

arise from the perception of lack of fit betwee

what women are like and what is required

perform in a male-typed position are likely

promotegenderbias in evaluativedecision

making and prompt discrimination in recru

ment (Gaucher, Friesen, & Kay, 2011), selectio

(Biernat & Fuegen, 2001), performance

appraisal (Bauer & Baltes, 2002), promotio

(Lyness & Heilman, 2006), and compensati

(Castilla, 2008). Figure 1 provides a depict

of the lack of fit model and its effects.

Given the persistence of gender stereotype

and the tenacity of negative performance exp

tations about women in male-typed positions,

is unsurprising to see that gender equality in t

workplace has not yet been achieved. Yet, ove

coming gender discrimination is not impossibl

Organizations hoping to address gender dis

crimination must directly target the factors th

give rise to it and the conditions that promote

The remaining portion of the paper is dedicat

to reviewingand proposingstrategies,built

upon the tenets of the lack of fit model, that d

just that.

Strategies

We broadly identify two sets of intervention st

gies. The first involves decreasing lack of fit pe

tions. The second involves breaking the link be

the expectations of incompetence that arise fr

lack of fit perceptions and the gender bias in e

ative decision making it fosters. Although the

vention strategies are presented individually,

not necessarily independent; under some cond

they may stand on their own, but under others

may be more effective if used in combinat

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

728 Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

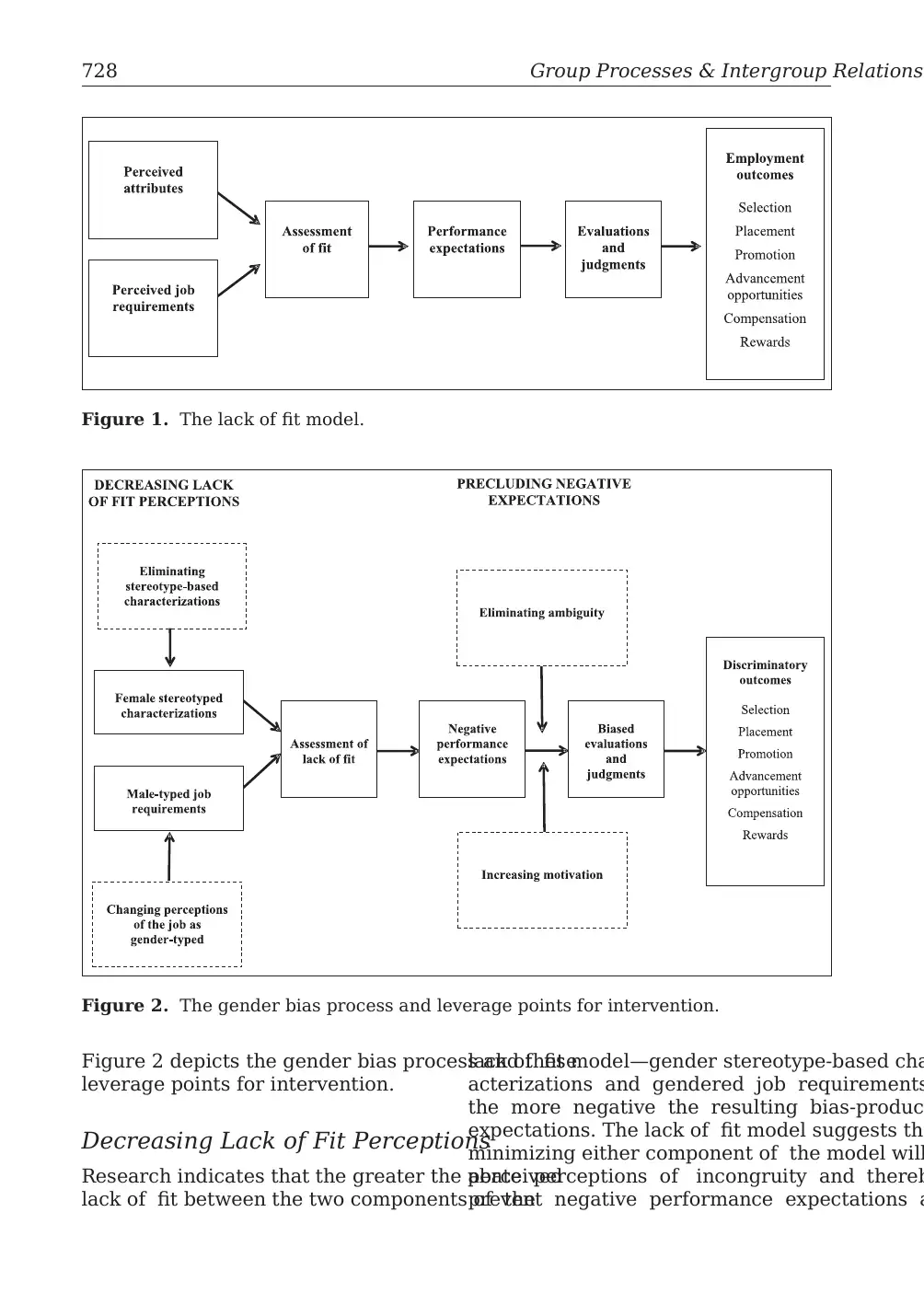

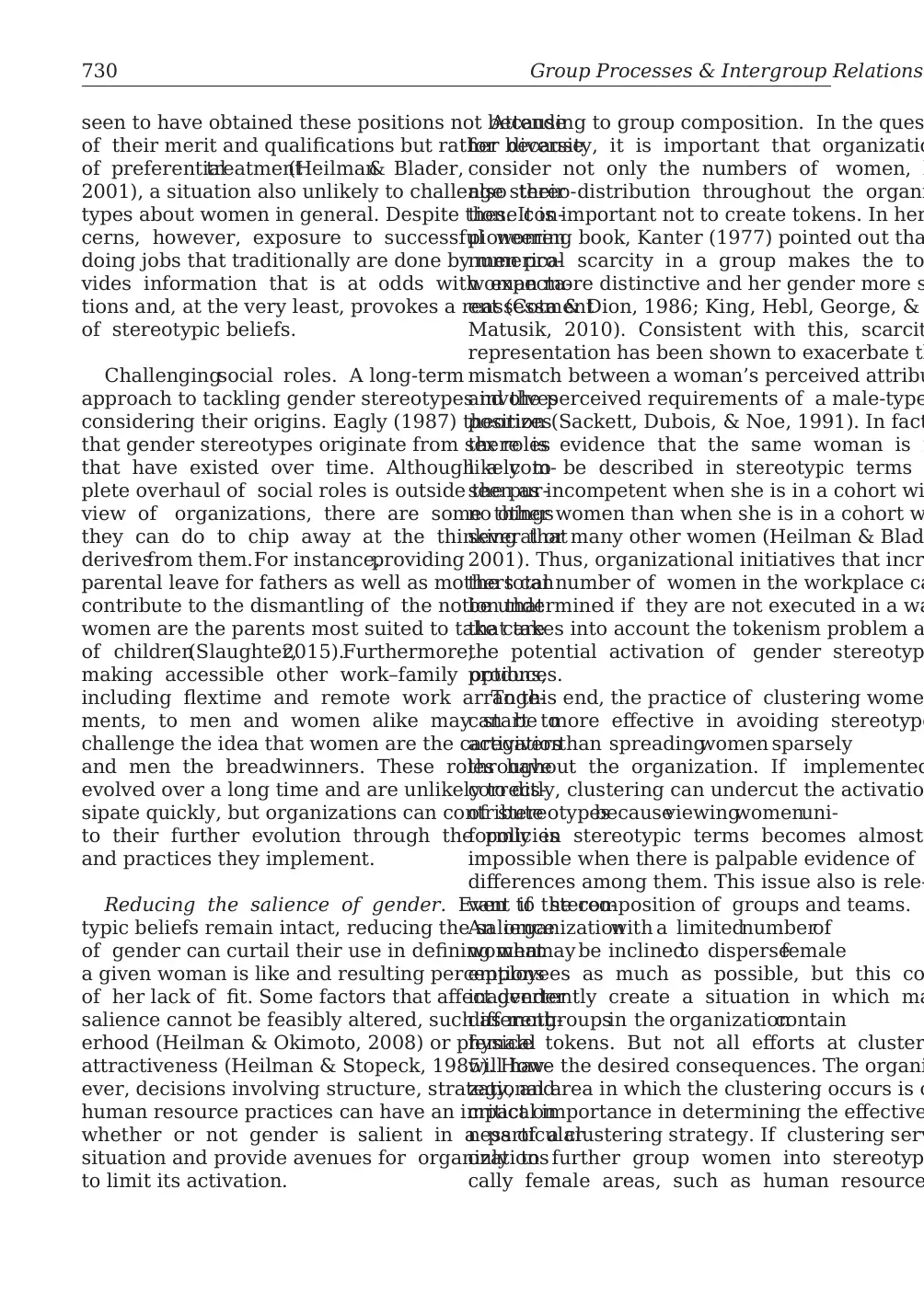

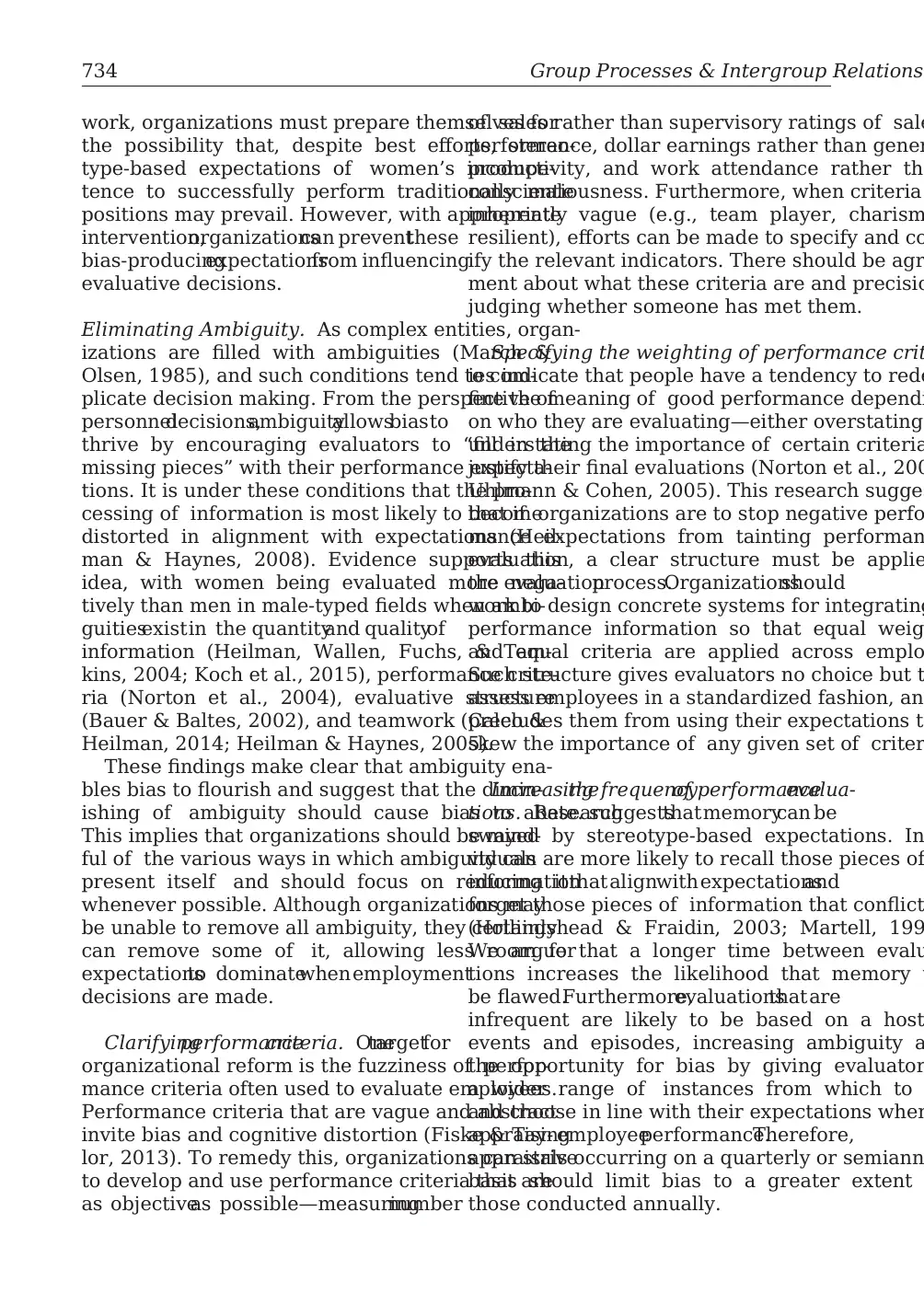

Figure 2 depicts the gender bias process and these

leverage points for intervention.

Decreasing Lack of Fit Perceptions

Research indicates that the greater the perceived

lack of fit between the two components of the

lack of fit model—gender stereotype-based cha

acterizations and gendered job requirements

the more negative the resulting bias-produci

expectations. The lack of fit model suggests tha

minimizing either component of the model will

abate perceptions of incongruity and thereb

prevent negative performance expectations a

Figure 1. The lack of fit model.

Figure 2. The gender bias process and leverage points for intervention.

Figure 2 depicts the gender bias process and these

leverage points for intervention.

Decreasing Lack of Fit Perceptions

Research indicates that the greater the perceived

lack of fit between the two components of the

lack of fit model—gender stereotype-based cha

acterizations and gendered job requirements

the more negative the resulting bias-produci

expectations. The lack of fit model suggests tha

minimizing either component of the model will

abate perceptions of incongruity and thereb

prevent negative performance expectations a

Figure 1. The lack of fit model.

Figure 2. The gender bias process and leverage points for intervention.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Heilman and Caleo 729

biased decision-making processes from taking

hold. We discuss each of these below.

Eliminating Stereotype-Based Characterizations. Detri-

mental stereotype-based characterizations can be

eliminated from decision making by changing ste-

reotypical beliefs about women or by inhibiting

their use by reducing the salience of gender.

Changinggenderstereotypes. Thelack of fit

model is grounded on the premise that gender

stereotypes dominate in the workplace, shaping

the ways applicants and employees are perceived.

This suggests that in efforts to curb gender dis-

crimination, organizations should focus on elimi-

nating gender stereotypes. This seems obvious.

In fact, research has shown that people who

do not hold stereotypic beliefs are less likely to

engage in gender discriminatory behavior (Bauer

& Baltes, 2002). However, accomplishing this is

neither easy nor straightforward. Despite dec-

ades of concerted efforts by organizations to

eliminate stereotypes—most evident in training

and other types of educational programs (Kulik

& Roberson, 2008)—the results are not encour-

aging. Studies suggest that stereotypes have not

changed appreciably (Haines et al., 2016), and

the incidence of gender discrimination has not

decidedly declined (Jones, Peddie, Gilrane, King,

& Gray, 2016; Koch, D’Mello, & Sackett, 2015).

Such findings suggest that it is more difficult to

change minds than organizations might believe.

Educationand training. Theremedymost

frequently employed by organizations to address

discrimination, diversity training, is designed to

confront decision makers’ biases and to lessen the

propensity to stereotype (Dobbin, Kalev, & Kelly,

2007). Yet, the evidence surrounding its effective-

ness is at best mixed, appearing to depend on the

outcome in question. According to a recent meta-

analysis (Bezrukova, Spell, Perry, & Jehn, 2016),

the cognitive knowledge obtained during diver-

sity training tends to endure; however, changes

in attitudinal outcomes tend to fade over time.

Evidence relating to behavioral outcomes also is

not encouraging (Bezrukova et al., 2016). Kalev,

Dobbin, and Kelly (2006), for example, found

diversity training to be among the least effecti

diversity management techniques, noting th

does little to increase the proportion of wome

and members of minority groups in manageri

positions.

Despite this unimpressive record of success

perhaps because of it, alternative forms of trai

continue to emerge, the most recent being unc

scious bias training (Lublin, 2014). This ty

training involves making people aware of impl

stereotypes and biases, with an eye on reducin

automaticassociationsthey may hold. Some

research suggests positive outcomes (Carnes e

2015; Jackson, Hillard, & Schneider, 2014), bu

is little evidence of its actual effectiveness in q

the use of stereotypes in workplace setting

short, despite the widespread use of educa

interventions to eliminate the use of stereo

their success has not been overwhelming.

Increasing the presence of women in traditi

male roles. Having women at the upper levels

organizations can reduce stereotyping. Resear

has shown that the simple presence of a stere

type-disconfirming group member can cause a

change in stereotype-based beliefs (Johnston &

Hewstone, 1990; Weber & Crocker, 1983). Ev

dence in fact suggests that observing successf

women in high-profile, male-typed leadershi

positions not only weakens stereotypical belie

but also activates counterstereotypical belie

(Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004). This outcome is no

necessarilylimitedto upperlevelleadership

positions. Exposure to women in many types o

traditionally male jobs and roles is likely to ch

lenge expectations and erode stereotypical cha

acterizations of women and the resulting lack

fit perceptions that promote gender bias a

discrimination.

However, this outcome is not guaranteed, a

organizations should be aware that merely inc

ing the presence of women is not a foolp

solutionfor changingstereotypes.Sometimes,

for example, women are subtyped and seen

exceptional and not representative of women

general (Richards & Hewstone, 2001), all of w

would not bring about change in how women i

general are viewed. At other times, women

biased decision-making processes from taking

hold. We discuss each of these below.

Eliminating Stereotype-Based Characterizations. Detri-

mental stereotype-based characterizations can be

eliminated from decision making by changing ste-

reotypical beliefs about women or by inhibiting

their use by reducing the salience of gender.

Changinggenderstereotypes. Thelack of fit

model is grounded on the premise that gender

stereotypes dominate in the workplace, shaping

the ways applicants and employees are perceived.

This suggests that in efforts to curb gender dis-

crimination, organizations should focus on elimi-

nating gender stereotypes. This seems obvious.

In fact, research has shown that people who

do not hold stereotypic beliefs are less likely to

engage in gender discriminatory behavior (Bauer

& Baltes, 2002). However, accomplishing this is

neither easy nor straightforward. Despite dec-

ades of concerted efforts by organizations to

eliminate stereotypes—most evident in training

and other types of educational programs (Kulik

& Roberson, 2008)—the results are not encour-

aging. Studies suggest that stereotypes have not

changed appreciably (Haines et al., 2016), and

the incidence of gender discrimination has not

decidedly declined (Jones, Peddie, Gilrane, King,

& Gray, 2016; Koch, D’Mello, & Sackett, 2015).

Such findings suggest that it is more difficult to

change minds than organizations might believe.

Educationand training. Theremedymost

frequently employed by organizations to address

discrimination, diversity training, is designed to

confront decision makers’ biases and to lessen the

propensity to stereotype (Dobbin, Kalev, & Kelly,

2007). Yet, the evidence surrounding its effective-

ness is at best mixed, appearing to depend on the

outcome in question. According to a recent meta-

analysis (Bezrukova, Spell, Perry, & Jehn, 2016),

the cognitive knowledge obtained during diver-

sity training tends to endure; however, changes

in attitudinal outcomes tend to fade over time.

Evidence relating to behavioral outcomes also is

not encouraging (Bezrukova et al., 2016). Kalev,

Dobbin, and Kelly (2006), for example, found

diversity training to be among the least effecti

diversity management techniques, noting th

does little to increase the proportion of wome

and members of minority groups in manageri

positions.

Despite this unimpressive record of success

perhaps because of it, alternative forms of trai

continue to emerge, the most recent being unc

scious bias training (Lublin, 2014). This ty

training involves making people aware of impl

stereotypes and biases, with an eye on reducin

automaticassociationsthey may hold. Some

research suggests positive outcomes (Carnes e

2015; Jackson, Hillard, & Schneider, 2014), bu

is little evidence of its actual effectiveness in q

the use of stereotypes in workplace setting

short, despite the widespread use of educa

interventions to eliminate the use of stereo

their success has not been overwhelming.

Increasing the presence of women in traditi

male roles. Having women at the upper levels

organizations can reduce stereotyping. Resear

has shown that the simple presence of a stere

type-disconfirming group member can cause a

change in stereotype-based beliefs (Johnston &

Hewstone, 1990; Weber & Crocker, 1983). Ev

dence in fact suggests that observing successf

women in high-profile, male-typed leadershi

positions not only weakens stereotypical belie

but also activates counterstereotypical belie

(Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004). This outcome is no

necessarilylimitedto upperlevelleadership

positions. Exposure to women in many types o

traditionally male jobs and roles is likely to ch

lenge expectations and erode stereotypical cha

acterizations of women and the resulting lack

fit perceptions that promote gender bias a

discrimination.

However, this outcome is not guaranteed, a

organizations should be aware that merely inc

ing the presence of women is not a foolp

solutionfor changingstereotypes.Sometimes,

for example, women are subtyped and seen

exceptional and not representative of women

general (Richards & Hewstone, 2001), all of w

would not bring about change in how women i

general are viewed. At other times, women

730 Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

seen to have obtained these positions not because

of their merit and qualifications but rather because

of preferentialtreatment(Heilman& Blader,

2001), a situation also unlikely to challenge stereo-

types about women in general. Despite these con-

cerns, however, exposure to successful women

doing jobs that traditionally are done by men pro-

vides information that is at odds with expecta-

tions and, at the very least, provokes a reassessment

of stereotypic beliefs.

Challengingsocial roles. A long-term

approach to tackling gender stereotypes involves

considering their origins. Eagly (1987) theorizes

that gender stereotypes originate from sex roles

that have existed over time. Although a com-

plete overhaul of social roles is outside the pur-

view of organizations, there are some things

they can do to chip away at the thinking that

derivesfrom them. For instance,providing

parental leave for fathers as well as mothers can

contribute to the dismantling of the notion that

women are the parents most suited to take care

of children(Slaughter,2015).Furthermore,

making accessible other work–family options,

including flextime and remote work arrange-

ments, to men and women alike may start to

challenge the idea that women are the caregivers

and men the breadwinners. These roles have

evolved over a long time and are unlikely to dis-

sipate quickly, but organizations can contribute

to their further evolution through the policies

and practices they implement.

Reducing the salience of gender. Even if stereo-

typic beliefs remain intact, reducing the salience

of gender can curtail their use in defining what

a given woman is like and resulting perceptions

of her lack of fit. Some factors that affect gender

salience cannot be feasibly altered, such as moth-

erhood (Heilman & Okimoto, 2008) or physical

attractiveness (Heilman & Stopeck, 1985). How-

ever, decisions involving structure, strategy, and

human resource practices can have an impact on

whether or not gender is salient in a particular

situation and provide avenues for organizations

to limit its activation.

Attending to group composition. In the ques

for diversity, it is important that organizatio

consider not only the numbers of women, b

also their distribution throughout the organi

tion. It is important not to create tokens. In her

pioneering book, Kanter (1977) pointed out tha

numerical scarcity in a group makes the to

woman more distinctive and her gender more s

ent (Cota & Dion, 1986; King, Hebl, George, &

Matusik, 2010). Consistent with this, scarcit

representation has been shown to exacerbate th

mismatch between a woman’s perceived attribu

and the perceived requirements of a male-type

position (Sackett, Dubois, & Noe, 1991). In fact

there is evidence that the same woman is m

likely to be described in stereotypic terms

seen as incompetent when she is in a cohort wi

no other women than when she is in a cohort w

several or many other women (Heilman & Blad

2001). Thus, organizational initiatives that incr

the total number of women in the workplace ca

be undermined if they are not executed in a wa

that takes into account the tokenism problem a

the potential activation of gender stereotyp

produces.

To this end, the practice of clustering wome

can be more effective in avoiding stereotype

activationthan spreadingwomen sparsely

throughout the organization. If implemented

correctly, clustering can undercut the activatio

of stereotypesbecauseviewingwomenuni-

formly in stereotypic terms becomes almost

impossible when there is palpable evidence of

differences among them. This issue also is rele-

vant to the composition of groups and teams.

An organizationwith a limitednumberof

womenmay be inclinedto dispersefemale

employees as much as possible, but this co

inadvertently create a situation in which ma

differentgroupsin the organizationcontain

female tokens. But not all efforts at cluster

will have the desired consequences. The organi

zational area in which the clustering occurs is o

critical importance in determining the effective

ness of a clustering strategy. If clustering serv

only to further group women into stereotyp

cally female areas, such as human resource

seen to have obtained these positions not because

of their merit and qualifications but rather because

of preferentialtreatment(Heilman& Blader,

2001), a situation also unlikely to challenge stereo-

types about women in general. Despite these con-

cerns, however, exposure to successful women

doing jobs that traditionally are done by men pro-

vides information that is at odds with expecta-

tions and, at the very least, provokes a reassessment

of stereotypic beliefs.

Challengingsocial roles. A long-term

approach to tackling gender stereotypes involves

considering their origins. Eagly (1987) theorizes

that gender stereotypes originate from sex roles

that have existed over time. Although a com-

plete overhaul of social roles is outside the pur-

view of organizations, there are some things

they can do to chip away at the thinking that

derivesfrom them. For instance,providing

parental leave for fathers as well as mothers can

contribute to the dismantling of the notion that

women are the parents most suited to take care

of children(Slaughter,2015).Furthermore,

making accessible other work–family options,

including flextime and remote work arrange-

ments, to men and women alike may start to

challenge the idea that women are the caregivers

and men the breadwinners. These roles have

evolved over a long time and are unlikely to dis-

sipate quickly, but organizations can contribute

to their further evolution through the policies

and practices they implement.

Reducing the salience of gender. Even if stereo-

typic beliefs remain intact, reducing the salience

of gender can curtail their use in defining what

a given woman is like and resulting perceptions

of her lack of fit. Some factors that affect gender

salience cannot be feasibly altered, such as moth-

erhood (Heilman & Okimoto, 2008) or physical

attractiveness (Heilman & Stopeck, 1985). How-

ever, decisions involving structure, strategy, and

human resource practices can have an impact on

whether or not gender is salient in a particular

situation and provide avenues for organizations

to limit its activation.

Attending to group composition. In the ques

for diversity, it is important that organizatio

consider not only the numbers of women, b

also their distribution throughout the organi

tion. It is important not to create tokens. In her

pioneering book, Kanter (1977) pointed out tha

numerical scarcity in a group makes the to

woman more distinctive and her gender more s

ent (Cota & Dion, 1986; King, Hebl, George, &

Matusik, 2010). Consistent with this, scarcit

representation has been shown to exacerbate th

mismatch between a woman’s perceived attribu

and the perceived requirements of a male-type

position (Sackett, Dubois, & Noe, 1991). In fact

there is evidence that the same woman is m

likely to be described in stereotypic terms

seen as incompetent when she is in a cohort wi

no other women than when she is in a cohort w

several or many other women (Heilman & Blad

2001). Thus, organizational initiatives that incr

the total number of women in the workplace ca

be undermined if they are not executed in a wa

that takes into account the tokenism problem a

the potential activation of gender stereotyp

produces.

To this end, the practice of clustering wome

can be more effective in avoiding stereotype

activationthan spreadingwomen sparsely

throughout the organization. If implemented

correctly, clustering can undercut the activatio

of stereotypesbecauseviewingwomenuni-

formly in stereotypic terms becomes almost

impossible when there is palpable evidence of

differences among them. This issue also is rele-

vant to the composition of groups and teams.

An organizationwith a limitednumberof

womenmay be inclinedto dispersefemale

employees as much as possible, but this co

inadvertently create a situation in which ma

differentgroupsin the organizationcontain

female tokens. But not all efforts at cluster

will have the desired consequences. The organi

zational area in which the clustering occurs is o

critical importance in determining the effective

ness of a clustering strategy. If clustering serv

only to further group women into stereotyp

cally female areas, such as human resource

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Heilman and Caleo 731

marketing,or publicrelations,and not into

those that typically are dominated by men, it will

do little to undercut the activation of stereo-

types and could actually exacerbate it.

Keeping blind. Researchers have found that

the mere provision of a male or female name can

induce the use of gender stereotypes and gender

bias through lack of fit processes (e.g., Heilman

& Haynes, 2005). If a name alone is sufficient to

activate gender stereotypes, one possibility is to

eliminate identifiers from applications. Leaving a

person’s name or identification out of materials

precludes decision makers from making gender

stereotypical inferences because they lack knowl-

edge of the person’s gender. One notable exam-

ple by Goldin and Rouse (2000) involved blind

auditions for an orchestra, where a screen was

used to conceal the identity of the candidate.

The researchers found blind auditions to result

in a higher number of women selected for the

position.

Though it would be unfeasible for organiza-

tions to hide an applicant’s identity during an

interview, it is certainly possible to eliminate iden-

tifying information during the early stages of the

selectionprocess—applications,résumés,and

cover letters. To the extent that it is possible, gen-

der identifiers also can be eliminated from reports

and other work outcomes until evaluations have

been made. However, these procedures should be

engaged in with care. Removing gender markers

can increase the propensity for people to search

for cues that may be related to gender, making

them less likely, for instance, to excuse an appli-

cant with unexplained time off from work in a

résumé. Although more research is needed to

identify when this is most likely to happen, exist-

ing work hints that blind résumés may not always

result in more minority hires (Behaghel, Crepon,

& Le Barbachon, 2015).

Highlighting other ingroup affiliations. People

have many group affiliations—gender is just one

of them. Because gender is so noticeable and

information about it so readily available, it is very

often a primary dimension along which people

are categorized (Ito & Urland, 2003; Stang

Lynch, Duan, & Glas, 1992). But in many situa

tions, cross-cutting ingroup affiliations, such

school attended or place of birth, can superse

gender (van Bavel & Cunningham, 2009). T

malleability of group identity has been am

demonstrated by social identity theorists, a

Tajfel’s (1970) minimal group paradigm ma

clear the feasibility of creating alternative ing

affiliations. Thus, it should be possible to distr

from the salience of gender by emphasizing e

ments of identity other than gender, such

organizational function (e.g., accountant), orga

zational unit (e.g., sales), or organizational loc

(e.g., the uptown group), when evaluative

sion making is occurring. This can be achieved

the type of information about a woman that is

made available to decision makers and the pro

nence and priority given to different aspects o

her identity. Yet, organizations must exercise

tion to ensurethat the emphasizedidentity

dimension is not itself gendered. Some ingrou

affiliations, such as engineer or parent (Heilm

& Okimoto, 2008), can inadvertently increase

salience of gender, therefore working against

intended effect.

Avoiding overt emphasis on diversity goals a

policies. Ironically, despite the positive con

quences of diversity goals and policies (Thom

2004), the use of the diversity label can activa

stereotypes by making salient a woman’s gend

In a study focusing on this issue, a female grou

memberwas characterizedas lesscompetent

when she participated in a workgroup that

assembled to heighten the organization’s dem

graphic diversity as opposed to workgroups th

were assembled either to ensure the organ

tion’s best resources and expertise were re

sented or on the basis of convenience (Heilma

& Welle, 2006). These findings make clear tha

focus on diversity to the exclusion of otherfac

tors can make gender salient, activating st

typesand negativelyaffectingthe ostensible

beneficiary of the diversity effort. A similar ca

can be made for affirmative action program

which also highlight gender and activate gend

marketing,or publicrelations,and not into

those that typically are dominated by men, it will

do little to undercut the activation of stereo-

types and could actually exacerbate it.

Keeping blind. Researchers have found that

the mere provision of a male or female name can

induce the use of gender stereotypes and gender

bias through lack of fit processes (e.g., Heilman

& Haynes, 2005). If a name alone is sufficient to

activate gender stereotypes, one possibility is to

eliminate identifiers from applications. Leaving a

person’s name or identification out of materials

precludes decision makers from making gender

stereotypical inferences because they lack knowl-

edge of the person’s gender. One notable exam-

ple by Goldin and Rouse (2000) involved blind

auditions for an orchestra, where a screen was

used to conceal the identity of the candidate.

The researchers found blind auditions to result

in a higher number of women selected for the

position.

Though it would be unfeasible for organiza-

tions to hide an applicant’s identity during an

interview, it is certainly possible to eliminate iden-

tifying information during the early stages of the

selectionprocess—applications,résumés,and

cover letters. To the extent that it is possible, gen-

der identifiers also can be eliminated from reports

and other work outcomes until evaluations have

been made. However, these procedures should be

engaged in with care. Removing gender markers

can increase the propensity for people to search

for cues that may be related to gender, making

them less likely, for instance, to excuse an appli-

cant with unexplained time off from work in a

résumé. Although more research is needed to

identify when this is most likely to happen, exist-

ing work hints that blind résumés may not always

result in more minority hires (Behaghel, Crepon,

& Le Barbachon, 2015).

Highlighting other ingroup affiliations. People

have many group affiliations—gender is just one

of them. Because gender is so noticeable and

information about it so readily available, it is very

often a primary dimension along which people

are categorized (Ito & Urland, 2003; Stang

Lynch, Duan, & Glas, 1992). But in many situa

tions, cross-cutting ingroup affiliations, such

school attended or place of birth, can superse

gender (van Bavel & Cunningham, 2009). T

malleability of group identity has been am

demonstrated by social identity theorists, a

Tajfel’s (1970) minimal group paradigm ma

clear the feasibility of creating alternative ing

affiliations. Thus, it should be possible to distr

from the salience of gender by emphasizing e

ments of identity other than gender, such

organizational function (e.g., accountant), orga

zational unit (e.g., sales), or organizational loc

(e.g., the uptown group), when evaluative

sion making is occurring. This can be achieved

the type of information about a woman that is

made available to decision makers and the pro

nence and priority given to different aspects o

her identity. Yet, organizations must exercise

tion to ensurethat the emphasizedidentity

dimension is not itself gendered. Some ingrou

affiliations, such as engineer or parent (Heilm

& Okimoto, 2008), can inadvertently increase

salience of gender, therefore working against

intended effect.

Avoiding overt emphasis on diversity goals a

policies. Ironically, despite the positive con

quences of diversity goals and policies (Thom

2004), the use of the diversity label can activa

stereotypes by making salient a woman’s gend

In a study focusing on this issue, a female grou

memberwas characterizedas lesscompetent

when she participated in a workgroup that

assembled to heighten the organization’s dem

graphic diversity as opposed to workgroups th

were assembled either to ensure the organ

tion’s best resources and expertise were re

sented or on the basis of convenience (Heilma

& Welle, 2006). These findings make clear tha

focus on diversity to the exclusion of otherfac

tors can make gender salient, activating st

typesand negativelyaffectingthe ostensible

beneficiary of the diversity effort. A similar ca

can be made for affirmative action program

which also highlight gender and activate gend

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

732 Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

stereotypes and can promote a “stigma of incom-

petence” for their intended beneficiaries (Heil-

man, Block, & Stathatos, 1997). This also has

implications for quota policies, now so prevalent

internationally. Sometimes an explicit focus on

diversity can backfire, with unintended but none-

theless detrimental, consequences for stereotype

activation.

Changing Perceptions of the Field or Job as Male Gender-

Typed. The second component of the lack of fit

model is the perception of the job. Not only are

some positions populated primarily by men, but

they also are perceived to require stereotypically

male attributes and behaviors that are consistent

with what men are thought to be like and incon-

sistent with what women are thought to be like

(Cejka & Eagly, 1999; Smyth & Nosek, 2015).

There is much evidence, for instance, that the

qualities that are thought necessary to be a suc-

cessful manager overlap with aspects of the male

stereotype but not with aspects of the female ste-

reotype (V. E. Schein, 2001). Consistent with lack

of fit ideas, there is a wealth of research showing

that gender discrimination occurs more frequently

in jobs that are seen as male gender-typed (Koch

et al., 2015; Lyness & Heilman, 2006; Pazy &

Oron, 2001). Although there is some evidence

that there have been shifts in gender-typing, such

as in the lessening of the masculine construal of

the leadership role (Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, &

Ristikari, 2011), there remains a well delineated set

of jobs and positions that are considered to be

“male” and, more often than not, they are the

ones that are higher paying and more prestigious.

Because stereotypes are most problematic to

women in jobs that are considered male gender-

typed, organizations can work to alter the percep-

tion of the particular position or occupation.

Althoughit may be unrealisticto expectan

organization to change the total perception of a

position or occupation, it can target a range of

practices that support and reinforce the percep-

tion of a field as male gender-typed. Some of

theseinvolvedecisionstraditionallymadeby

human resource departments and others involve

more pervasive images that are perpetuated by

corporate strategies or institutional contexts

this section, we discuss how organizations c

work to transformgenderedviewsof jobs,

organizations, and industries.

Gender-neutralizingjob descriptionsand job

titles. Decades ago, Bem and Bem (1973) d

cussed the prevalence of gender-biased wordin

in organizations—a practice they found to d

courage men and women from applying to cer-

tain positions. The use of gendered language in

their studies was anything but subtle: job adver

tisements in an actual newspaper were segrega

by sex, and job advertisements for a major

ephone company explicitly sought men for t

position of lineman and women for the position

of operator. Although these practices are m

understated today, research suggests that orga

zations continue to use gender-biased wordi

in job advertisements. Gaucher et al. (2011)

for example, found that job advertisements

male-typed positions used more masculine word

ing (e.g., competitive, dominant) than those

female-typed positions. These discrepancies als

appear in languages that are grammatically

linguistically gendered in nature, with research

in Europe finding that many organizations tend

to convey job titles by using the generic mascu-

line form instead of a gender-neutral equivalen

(Sczesny, Formanowicz, & Moser, 2016).

The implications of these subtle practices ar

striking, contributing to lack of fit percepti

and giving rise to discriminatory decisions a

early as recruitment. Importantly, scrutiny o

actual job responsibilities, and what it takes to

fill them, most often suggests a more gende

balanced picture. Even jobs considered to b

unequivocally male in character, such as firefig

ers, have been found to require behavior that is

considered to be stereotypically female—in this

case, compassion (Danbold & Bendersky, 2015)

Job descriptions that are dominated by male-ge

dered language perpetuate the image that t

positions necessitate stereotypically male beha

ior exclusively—an image that conveys the job a

inappropriate for women. In fact, research indi-

cates that gendered language in job description

stereotypes and can promote a “stigma of incom-

petence” for their intended beneficiaries (Heil-

man, Block, & Stathatos, 1997). This also has

implications for quota policies, now so prevalent

internationally. Sometimes an explicit focus on

diversity can backfire, with unintended but none-

theless detrimental, consequences for stereotype

activation.

Changing Perceptions of the Field or Job as Male Gender-

Typed. The second component of the lack of fit

model is the perception of the job. Not only are

some positions populated primarily by men, but

they also are perceived to require stereotypically

male attributes and behaviors that are consistent

with what men are thought to be like and incon-

sistent with what women are thought to be like

(Cejka & Eagly, 1999; Smyth & Nosek, 2015).

There is much evidence, for instance, that the

qualities that are thought necessary to be a suc-

cessful manager overlap with aspects of the male

stereotype but not with aspects of the female ste-

reotype (V. E. Schein, 2001). Consistent with lack

of fit ideas, there is a wealth of research showing

that gender discrimination occurs more frequently

in jobs that are seen as male gender-typed (Koch

et al., 2015; Lyness & Heilman, 2006; Pazy &

Oron, 2001). Although there is some evidence

that there have been shifts in gender-typing, such

as in the lessening of the masculine construal of

the leadership role (Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, &

Ristikari, 2011), there remains a well delineated set

of jobs and positions that are considered to be

“male” and, more often than not, they are the

ones that are higher paying and more prestigious.

Because stereotypes are most problematic to

women in jobs that are considered male gender-

typed, organizations can work to alter the percep-

tion of the particular position or occupation.

Althoughit may be unrealisticto expectan

organization to change the total perception of a

position or occupation, it can target a range of

practices that support and reinforce the percep-

tion of a field as male gender-typed. Some of

theseinvolvedecisionstraditionallymadeby

human resource departments and others involve

more pervasive images that are perpetuated by

corporate strategies or institutional contexts

this section, we discuss how organizations c

work to transformgenderedviewsof jobs,

organizations, and industries.

Gender-neutralizingjob descriptionsand job

titles. Decades ago, Bem and Bem (1973) d

cussed the prevalence of gender-biased wordin

in organizations—a practice they found to d

courage men and women from applying to cer-

tain positions. The use of gendered language in

their studies was anything but subtle: job adver

tisements in an actual newspaper were segrega

by sex, and job advertisements for a major

ephone company explicitly sought men for t

position of lineman and women for the position

of operator. Although these practices are m

understated today, research suggests that orga

zations continue to use gender-biased wordi

in job advertisements. Gaucher et al. (2011)

for example, found that job advertisements

male-typed positions used more masculine word

ing (e.g., competitive, dominant) than those

female-typed positions. These discrepancies als

appear in languages that are grammatically

linguistically gendered in nature, with research

in Europe finding that many organizations tend

to convey job titles by using the generic mascu-

line form instead of a gender-neutral equivalen

(Sczesny, Formanowicz, & Moser, 2016).

The implications of these subtle practices ar

striking, contributing to lack of fit percepti

and giving rise to discriminatory decisions a

early as recruitment. Importantly, scrutiny o

actual job responsibilities, and what it takes to

fill them, most often suggests a more gende

balanced picture. Even jobs considered to b

unequivocally male in character, such as firefig

ers, have been found to require behavior that is

considered to be stereotypically female—in this

case, compassion (Danbold & Bendersky, 2015)

Job descriptions that are dominated by male-ge

dered language perpetuate the image that t

positions necessitate stereotypically male beha

ior exclusively—an image that conveys the job a

inappropriate for women. In fact, research indi-

cates that gendered language in job description

Heilman and Caleo 733

affects both women’swillingnessto apply

(Gaucher et al., 2011) and their likelihood of

being selected (Horvath & Sczesny, 2015) for

positions depicted as highly male gender-typed.

In line with these ideas, the United States Marine

Corps—a traditionally male-dominated organiza-

tion—recently modified job titles that contained

the word “man,” opting instead for the gender-

neutral “Marine” (Seck, 2016). This action was

directed toward both increasing the appeal of

these jobs to women and decreasing the negativ-

ity they might encounter when pursuing them.

De-masculinizing organizational culture. Organiza-

tional culture refers to the system of shared val-

ues, assumptions, and norms that drive behavior

in organizations (E. H. Schein, 2010). In effect, it

conveys the values and conduct that are deemed

appropriate in a given organization. Culture also

gives decision makers an idea of the kinds of

employees that may fit in best (Schneider, 1987).

It has been argued that an organization’s cul-

ture can be tinged with masculine or feminine

expectations, independent of discipline or type

of work (Guy & Duerst-Lahti, 1992). If this is

the case, we expect that women may be inadvert-

ently shut out of organizations that have a mas-

culine culture. Cultures that demand a high level

of competition, aggression, or risk-taking, for

example, may be seen as incongruent with the

perception that women lack agency.

The challenge is that culture is difficult to

change (E. H. Schein, 2010). However, being vigi-

lant of the norms in place and the extent to which

they perpetuate a gendered culture could be a

fruitful avenue for organizations to pursue. One

way to start would be to survey the organization’s

core valuesand strategy.Anotherpossibility

involves focusing on the norms that thrive in the

organization and considering whether they neces-

sitate masculinity. For example, something as

simple as the style of meetings may perpetuate

the notion that women do not belong in these

settings. Also included in the conceptualization

of organizational culture are artifacts—physical

symbols, rituals, and stories that convey the cul-

ture of the organization (E. H. Schein, 2010),

such as the bull representing Wall Street,

cigars passed around to celebrate the birth of

child, or client meetings at gentlemen’s clu

Environmentssignalwho belongsin them

(Cheryan, Plaut, Davies, & Steele, 2009), a

organizations should be mindful to ensure tha

excess of masculinity is not being conveyed.

Increasing the presence of women in traditi

roles. We previously proposed that increasing

presence of women in male gender-typed

could help combat stereotypical beliefs. Howe

because gender-typing is in part a result of nu

ical gender proportion (Cejka & Eagly, 199

Smyth & Nosek, 2015), increasing the pres

of women in male-dominated fields can also h

to shift job perceptions. Showcasing women w

have defied expectations by succeeding in

considered to be male in gender-type can

the conception of the job itself, raising questio

about whether it really is so male-typed in

requirements if a woman can do it so well. Ho

ever, as with the changing of stereotypes,

efforts can fall short when the stereotype-defy

woman is subtyped and not seen as repres

tive of women in general and when the proces

obtaining the position is seen as based on pref

ence rather than merit. In these situations, gre

numbers of women in stereotype-disconfirm

jobs would be less likely to challenge the perc

tion of a job as male gender-typed and to brin

about a change in how the job is viewed. None

theless, the presence of women in these posit

captures attention and is apt to at least raise q

tions about the gendered nature of the job.

Precluding Negative Expectations From

Affecting Evaluative Decisions

Thus far we have discussed ways in which org

zationscan combatgenderdiscriminationby

minimizing lack of fit perceptions—strategi

that could prevent the formation of negative p

formance expectations that lead to gender

and, in turn, discriminatory behavior. Howev

given the persistence of both stereotypes abo

women and ingrained beliefs about male-ty

affects both women’swillingnessto apply

(Gaucher et al., 2011) and their likelihood of

being selected (Horvath & Sczesny, 2015) for

positions depicted as highly male gender-typed.

In line with these ideas, the United States Marine

Corps—a traditionally male-dominated organiza-

tion—recently modified job titles that contained

the word “man,” opting instead for the gender-

neutral “Marine” (Seck, 2016). This action was

directed toward both increasing the appeal of

these jobs to women and decreasing the negativ-

ity they might encounter when pursuing them.

De-masculinizing organizational culture. Organiza-

tional culture refers to the system of shared val-

ues, assumptions, and norms that drive behavior

in organizations (E. H. Schein, 2010). In effect, it

conveys the values and conduct that are deemed

appropriate in a given organization. Culture also

gives decision makers an idea of the kinds of

employees that may fit in best (Schneider, 1987).

It has been argued that an organization’s cul-

ture can be tinged with masculine or feminine

expectations, independent of discipline or type

of work (Guy & Duerst-Lahti, 1992). If this is

the case, we expect that women may be inadvert-

ently shut out of organizations that have a mas-

culine culture. Cultures that demand a high level

of competition, aggression, or risk-taking, for

example, may be seen as incongruent with the

perception that women lack agency.

The challenge is that culture is difficult to

change (E. H. Schein, 2010). However, being vigi-

lant of the norms in place and the extent to which

they perpetuate a gendered culture could be a

fruitful avenue for organizations to pursue. One

way to start would be to survey the organization’s

core valuesand strategy.Anotherpossibility

involves focusing on the norms that thrive in the

organization and considering whether they neces-

sitate masculinity. For example, something as

simple as the style of meetings may perpetuate

the notion that women do not belong in these

settings. Also included in the conceptualization

of organizational culture are artifacts—physical

symbols, rituals, and stories that convey the cul-

ture of the organization (E. H. Schein, 2010),

such as the bull representing Wall Street,

cigars passed around to celebrate the birth of

child, or client meetings at gentlemen’s clu

Environmentssignalwho belongsin them

(Cheryan, Plaut, Davies, & Steele, 2009), a

organizations should be mindful to ensure tha

excess of masculinity is not being conveyed.

Increasing the presence of women in traditi

roles. We previously proposed that increasing

presence of women in male gender-typed

could help combat stereotypical beliefs. Howe

because gender-typing is in part a result of nu

ical gender proportion (Cejka & Eagly, 199

Smyth & Nosek, 2015), increasing the pres

of women in male-dominated fields can also h

to shift job perceptions. Showcasing women w

have defied expectations by succeeding in

considered to be male in gender-type can

the conception of the job itself, raising questio

about whether it really is so male-typed in

requirements if a woman can do it so well. Ho

ever, as with the changing of stereotypes,

efforts can fall short when the stereotype-defy

woman is subtyped and not seen as repres

tive of women in general and when the proces

obtaining the position is seen as based on pref

ence rather than merit. In these situations, gre

numbers of women in stereotype-disconfirm

jobs would be less likely to challenge the perc

tion of a job as male gender-typed and to brin

about a change in how the job is viewed. None

theless, the presence of women in these posit

captures attention and is apt to at least raise q

tions about the gendered nature of the job.

Precluding Negative Expectations From

Affecting Evaluative Decisions

Thus far we have discussed ways in which org

zationscan combatgenderdiscriminationby

minimizing lack of fit perceptions—strategi

that could prevent the formation of negative p

formance expectations that lead to gender

and, in turn, discriminatory behavior. Howev

given the persistence of both stereotypes abo

women and ingrained beliefs about male-ty

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

734 Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

work, organizations must prepare themselves for

the possibility that, despite best efforts, stereo-

type-based expectations of women’s incompe-

tence to successfully perform traditionally male

positions may prevail. However, with appropriate

intervention,organizationscan preventthese

bias-producingexpectationsfrom influencing

evaluative decisions.

Eliminating Ambiguity. As complex entities, organ-

izations are filled with ambiguities (March &

Olsen, 1985), and such conditions tend to com-

plicate decision making. From the perspective of

personneldecisions,ambiguityallowsbias to

thrive by encouraging evaluators to “fill in the

missing pieces” with their performance expecta-

tions. It is under these conditions that the pro-

cessing of information is most likely to become

distorted in alignment with expectations (Heil-

man & Haynes, 2008). Evidence supports this

idea, with women being evaluated more nega-

tively than men in male-typed fields when ambi-

guitiesexist in the quantityand qualityof

information (Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs, & Tam-

kins, 2004; Koch et al., 2015), performance crite-

ria (Norton et al., 2004), evaluative structure

(Bauer & Baltes, 2002), and teamwork (Caleo &

Heilman, 2014; Heilman & Haynes, 2005).

These findings make clear that ambiguity ena-

bles bias to flourish and suggest that the dimin-

ishing of ambiguity should cause bias to abate.

This implies that organizations should be mind-

ful of the various ways in which ambiguity can

present itself and should focus on reducing it

whenever possible. Although organizations may

be unable to remove all ambiguity, they certainly

can remove some of it, allowing less room for

expectationsto dominatewhen employment

decisions are made.

Clarifyingperformancecriteria. Onetargetfor

organizational reform is the fuzziness of perfor-

mance criteria often used to evaluate employees.

Performance criteria that are vague and abstract

invite bias and cognitive distortion (Fiske & Tay-

lor, 2013). To remedy this, organizations can strive

to develop and use performance criteria that are

as objectiveas possible—measuringnumber

of sales rather than supervisory ratings of sale

performance, dollar earnings rather than gener

productivity, and work attendance rather tha

conscientiousness. Furthermore, when criteria

inherently vague (e.g., team player, charism

resilient), efforts can be made to specify and co

ify the relevant indicators. There should be agr

ment about what these criteria are and precisio

judging whether someone has met them.

Specifying the weighting of performance crit