University of Potomac: Tech Changes and Student Impact - COMP640

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/09

|28

|9710

|15

Project

AI Summary

This capstone project investigates the multifaceted effects of technological advancements on students, focusing on the increasing dependency on technology and its implications for learning and daily life. The project explores the problem of technology overuse and its impact on students' cognitive abilities and learning outcomes. The research includes a literature review, methodology, findings, and conclusions. It examines the role of technology in education, including e-learning and the use of artificial intelligence, and discusses the impact of technology on students in higher education. The project aims to analyze the positive and negative impacts of technology, providing insights into the ways technology shapes the student experience. The project also includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, findings, conclusions and a list of references.

45© The Author(s) 2020

J. Seale (ed.), Improving Accessible Digital Practices in Higher

Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37125-8_3

CHAPTER 3

Accessibility Frameworks and Models:

Exploring the Potential for a Paradigm Shift

Sheryl Burgstahler, Alice Havel, Jane Seale,

and Dorit Olenik-Shemesh

Abstract The focus of this chapter is accessibility frameworks and mode

that have the potential to promote a paradigm shift whereby the design o

ICT and related practices that ensure the needs of students with disabili-

ties are fully addressed. In order to examine the potential of models and

frameworks to bring about such a paradigm shift and transform practice

this chapter will: (1) review common frameworks and associated models

that influence the design and delivery of accessibility services, (2) discuss

S. Burgstahler (* )

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

e-mail: sherylb@uw.edu

A. Havel

Adaptech Research Network, Montreal, QC, Canada

J. Seale

Faculty of Wellness, Education and Language Studies, The Open University,

Milton Keynes, UK

e-mail: jane.seale@open.ac.uk

D. Olenik-Shemesh

The Open University, Ra’anana, Israel

Burgstahler, S., Havel, A., Seale, J., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2020).

Accessibility frameworks and models: Exploring the potential for a

paradigm shift. In J. Seale (Ed.), Improving accessible digital practices in

higher education – Challenges and new practices for inclusion (pp.

45-72). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37125-8

J. Seale (ed.), Improving Accessible Digital Practices in Higher

Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37125-8_3

CHAPTER 3

Accessibility Frameworks and Models:

Exploring the Potential for a Paradigm Shift

Sheryl Burgstahler, Alice Havel, Jane Seale,

and Dorit Olenik-Shemesh

Abstract The focus of this chapter is accessibility frameworks and mode

that have the potential to promote a paradigm shift whereby the design o

ICT and related practices that ensure the needs of students with disabili-

ties are fully addressed. In order to examine the potential of models and

frameworks to bring about such a paradigm shift and transform practice

this chapter will: (1) review common frameworks and associated models

that influence the design and delivery of accessibility services, (2) discuss

S. Burgstahler (* )

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

e-mail: sherylb@uw.edu

A. Havel

Adaptech Research Network, Montreal, QC, Canada

J. Seale

Faculty of Wellness, Education and Language Studies, The Open University,

Milton Keynes, UK

e-mail: jane.seale@open.ac.uk

D. Olenik-Shemesh

The Open University, Ra’anana, Israel

Burgstahler, S., Havel, A., Seale, J., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2020).

Accessibility frameworks and models: Exploring the potential for a

paradigm shift. In J. Seale (Ed.), Improving accessible digital practices in

higher education – Challenges and new practices for inclusion (pp.

45-72). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37125-8

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

46

whether something other than (or in addition to) existing frameworks and

associated models is needed in order to activate a paradigm shift toward

more inclusive ICT and practices, and (3) discuss the implications fo

future research and practice.

Keywords ICT • Disability • Higher education • Accessibility •

Models • Frameworks

Common Frameworks ThaT InFluenCe The DesIgn

oF aCCessIbIlITy servICes

While many commentators in the field use the terms model and frame-

work interchangeably, we use the term “model” to refer to a practical or

conceptual representation of systems and processes; in our case, those t

are relevant to the provision and support of ICTs that contribute to suc-

cessful educational and employment outcomes for students with disabili-

ties. Models may describe existing practices (what is currently happening

or prescribe practices (what should be happening). “Frameworks” provide

foundational elements (e.g., principles or assumptions) of a model.

Adoption of frameworks and models on a campus can contribute to

“paradigm,” which refers to a widely accepted group of ideas about how

something should be done or thought about as an organization routinely

conducts business. The paradigm provides an almost unconscious, inter-

nalized way of thinking about how things should work, and what prob-

lems should be addressed. Common frameworks within higher education

(HE) reflect different views of disability, accommodation, and inclusion.

“Medical” or “deficit” views of disability rely on a medical diagnosis

and build on the assumption that the problems and difficulties that peopl

with disabilities experience are a direct result of their individual physical,

sensory, or cognitive impairments. As a response to this view, the major

task of professionals is to adjust the individual (e.g., through surge

medication, rehabilitation) or, at institutions of HE, provide accommoda-

tions that allow the person with a disability to access instruction and othe

campus offerings as much as is reasonable (Shakespeare, 1996). The locu

of change is the individual. In contrast, in the “social” and related views o

disability, barriers faced by people with disabilities are caused, to a large

part, by the failure of designers of social, physical, and technological prod

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

whether something other than (or in addition to) existing frameworks and

associated models is needed in order to activate a paradigm shift toward

more inclusive ICT and practices, and (3) discuss the implications fo

future research and practice.

Keywords ICT • Disability • Higher education • Accessibility •

Models • Frameworks

Common Frameworks ThaT InFluenCe The DesIgn

oF aCCessIbIlITy servICes

While many commentators in the field use the terms model and frame-

work interchangeably, we use the term “model” to refer to a practical or

conceptual representation of systems and processes; in our case, those t

are relevant to the provision and support of ICTs that contribute to suc-

cessful educational and employment outcomes for students with disabili-

ties. Models may describe existing practices (what is currently happening

or prescribe practices (what should be happening). “Frameworks” provide

foundational elements (e.g., principles or assumptions) of a model.

Adoption of frameworks and models on a campus can contribute to

“paradigm,” which refers to a widely accepted group of ideas about how

something should be done or thought about as an organization routinely

conducts business. The paradigm provides an almost unconscious, inter-

nalized way of thinking about how things should work, and what prob-

lems should be addressed. Common frameworks within higher education

(HE) reflect different views of disability, accommodation, and inclusion.

“Medical” or “deficit” views of disability rely on a medical diagnosis

and build on the assumption that the problems and difficulties that peopl

with disabilities experience are a direct result of their individual physical,

sensory, or cognitive impairments. As a response to this view, the major

task of professionals is to adjust the individual (e.g., through surge

medication, rehabilitation) or, at institutions of HE, provide accommoda-

tions that allow the person with a disability to access instruction and othe

campus offerings as much as is reasonable (Shakespeare, 1996). The locu

of change is the individual. In contrast, in the “social” and related views o

disability, barriers faced by people with disabilities are caused, to a large

part, by the failure of designers of social, physical, and technological prod

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

47

ucts and environments to take into account the needs of individuals with

a wide range of abilities. The locus of change is mainstream produ

environments, and related policies and social structures (Oliver, 199

Shakespeare, 2010). Acceptance of this view has resulted in disabili

related legislation in many countries requiring the accessible design

physical spaces including those in HE.

Disability service offices within HE institutions tend to rely on a medi-

cal view of disability, which can lead to an individualistic framework for

service provision, where the focus is on determining the functional limita-

tions of individuals with disabilities and then providing reasonable accom

modations to facilitate their access to a facility, service, course, or

technological resource. The provision of such services is typically depen-

dent on the person with a disability securing a “diagnosis” of a disability

by a recognized professional, providing a disability services office w

documentation of the disability, and securing approval for reasonabl

accommodations. An accommodations-only framework for service deliv-

ery with respect to ICT can lead to a focus on providing assistive technol-

ogy (AT) for specific individuals with disabilities, rather than on reducing

accessibility barriers imposed by mainstream ICT. A framework that relies

only or mainly on accommodations in institutions of HE today has been

criticized for focusing only on the perceived “deficit” of an individua

rather than looking to designing or redesigning educational products and

environments to be more accessible to individuals with disabilities (Loewe

& Pollard, 2010). Most proponents of the social view of disability in HE,

however, recognize that sometimes there is still a need to provide accom

modations to individuals in specific circumstances (e.g., sign langua

interpreters for students who are deaf attending lectures); suggesting tha

there is value in combining both frameworks, but where the social view o

disability is more dominant or prevalent.

Universal Design: An Example of Combining Frameworks

One well-known approach to service provision that prioritizes social and

related views of disability, while acknowledging accommodations may sti

be needed sometimes, is commonly labeled universal design (UD). UD is

the general term, and other terms are used when it pertains to specific

applications. For example, applications to teaching and learning have bee

referred to with labels that include Universal Design of Learning (UDL),

Universal Design for Instruction, Universal Design of Instruction,

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

ucts and environments to take into account the needs of individuals with

a wide range of abilities. The locus of change is mainstream produ

environments, and related policies and social structures (Oliver, 199

Shakespeare, 2010). Acceptance of this view has resulted in disabili

related legislation in many countries requiring the accessible design

physical spaces including those in HE.

Disability service offices within HE institutions tend to rely on a medi-

cal view of disability, which can lead to an individualistic framework for

service provision, where the focus is on determining the functional limita-

tions of individuals with disabilities and then providing reasonable accom

modations to facilitate their access to a facility, service, course, or

technological resource. The provision of such services is typically depen-

dent on the person with a disability securing a “diagnosis” of a disability

by a recognized professional, providing a disability services office w

documentation of the disability, and securing approval for reasonabl

accommodations. An accommodations-only framework for service deliv-

ery with respect to ICT can lead to a focus on providing assistive technol-

ogy (AT) for specific individuals with disabilities, rather than on reducing

accessibility barriers imposed by mainstream ICT. A framework that relies

only or mainly on accommodations in institutions of HE today has been

criticized for focusing only on the perceived “deficit” of an individua

rather than looking to designing or redesigning educational products and

environments to be more accessible to individuals with disabilities (Loewe

& Pollard, 2010). Most proponents of the social view of disability in HE,

however, recognize that sometimes there is still a need to provide accom

modations to individuals in specific circumstances (e.g., sign langua

interpreters for students who are deaf attending lectures); suggesting tha

there is value in combining both frameworks, but where the social view o

disability is more dominant or prevalent.

Universal Design: An Example of Combining Frameworks

One well-known approach to service provision that prioritizes social and

related views of disability, while acknowledging accommodations may sti

be needed sometimes, is commonly labeled universal design (UD). UD is

the general term, and other terms are used when it pertains to specific

applications. For example, applications to teaching and learning have bee

referred to with labels that include Universal Design of Learning (UDL),

Universal Design for Instruction, Universal Design of Instruction,

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

48

Universally Designed Instruction, Universally Designed Teaching, and

Inclusive Design for Learning. These practices build on, to varying

degrees, the work of the Center for Universal Design (CUD) at North

Carolina State University, which defines UD as “the design of products

and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possi

ble, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Center for

Universal Design, 1997). Each approach has adopted principles for the

design of inclusive practices. For example, the Centre for UD proposes

seven principles that guide UD applications to products and environment

(flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, toler-

ance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for approach and

use). The Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) proposes that

teaching and learning practices apply three principles of UDL—multiple

means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (Black,

Weinberg,& Brodwin, 2015; Rose, Harbour, Johnston, Daley, &

Abarbanell, 2006).

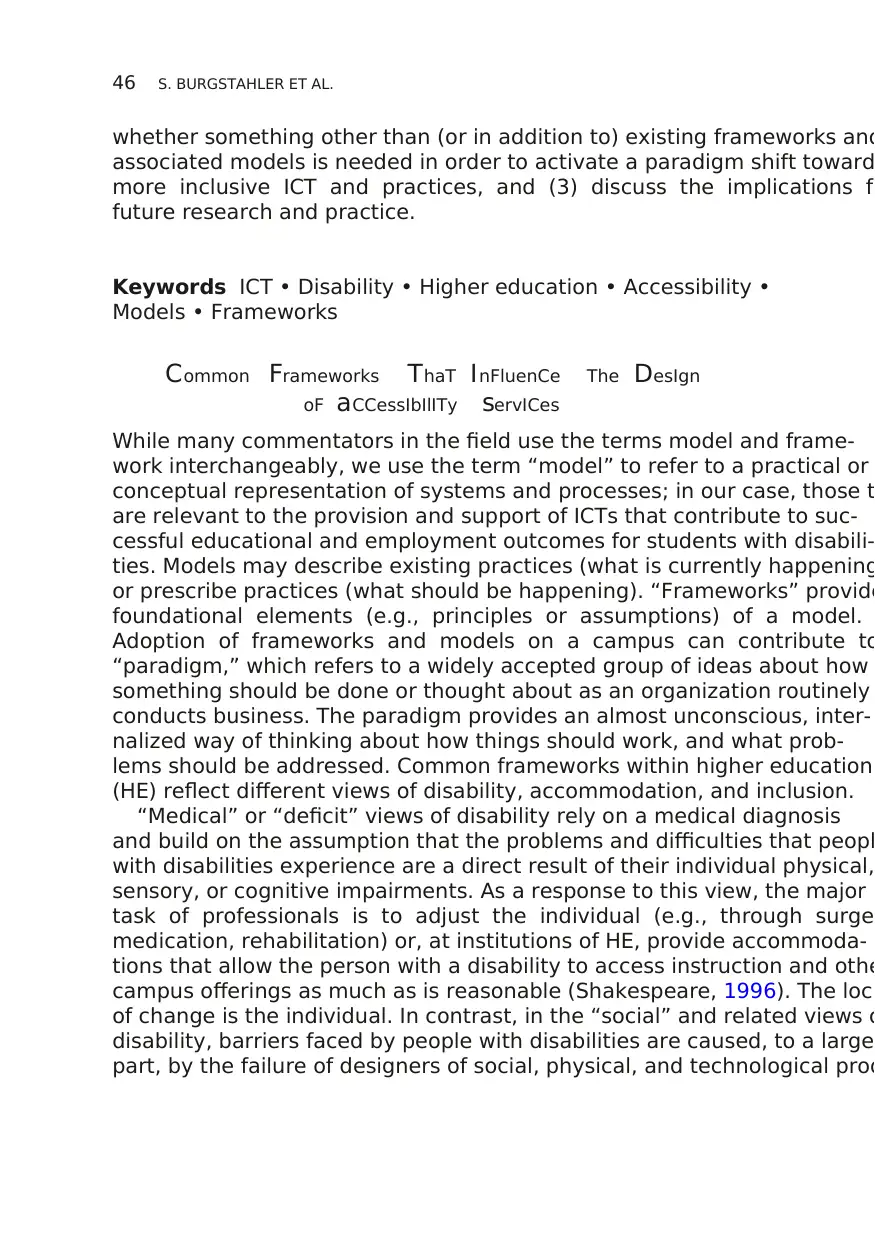

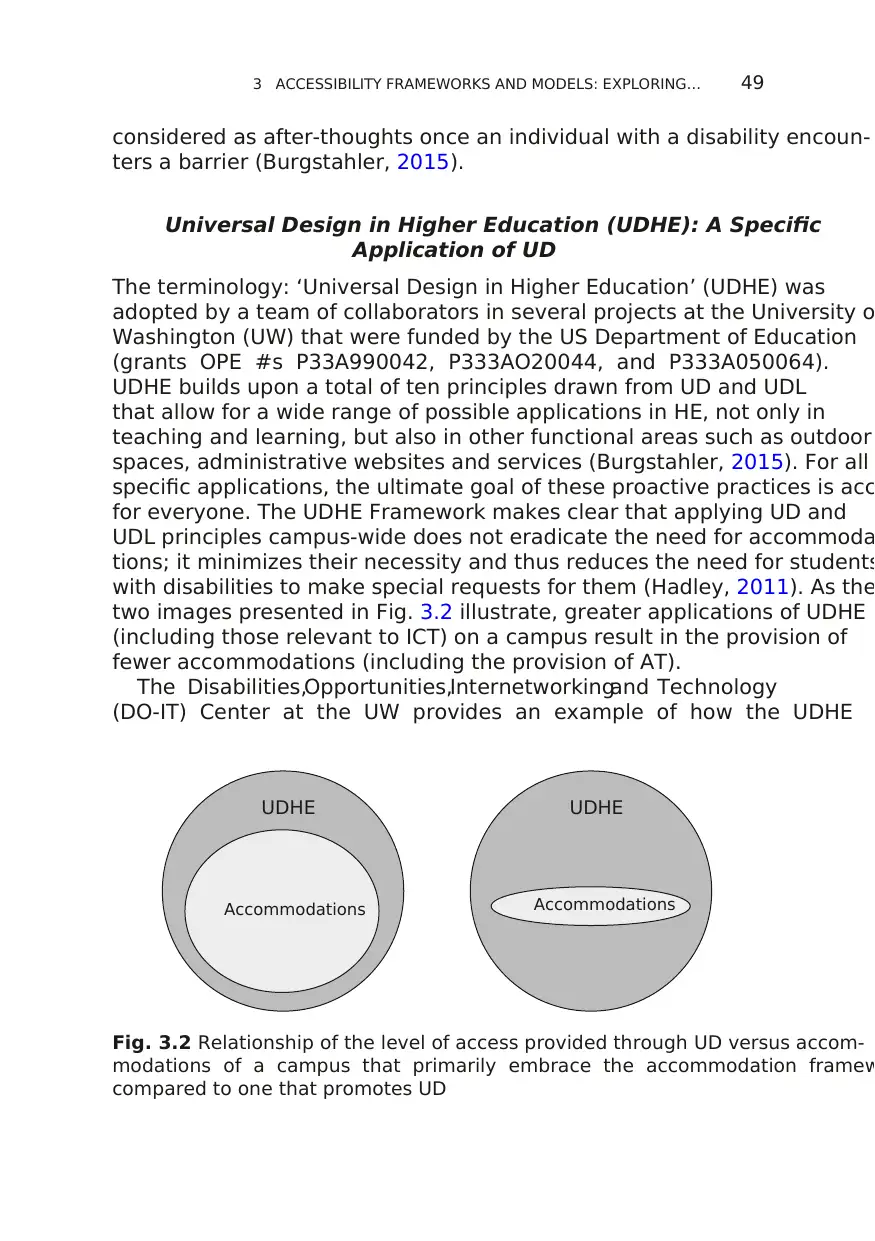

Common characteristics of any UD practice are accessibility, usability,

and inclusiveness, as illustrated in Fig. 3.1. UD is positioned as inclusive

because it values diversity, equity, and integration (Hockings, 2010). This

approach provides a way to conceptualize these common characteristics

a routine part of the design of campus-wide applications rather than bein

Fig. 3.1 Characteristics

of a UD strategy: It is

accessible, usable, and

inclusive. (Burgstahler,

2015, p. 15)

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

Universally Designed Instruction, Universally Designed Teaching, and

Inclusive Design for Learning. These practices build on, to varying

degrees, the work of the Center for Universal Design (CUD) at North

Carolina State University, which defines UD as “the design of products

and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possi

ble, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Center for

Universal Design, 1997). Each approach has adopted principles for the

design of inclusive practices. For example, the Centre for UD proposes

seven principles that guide UD applications to products and environment

(flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, toler-

ance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for approach and

use). The Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) proposes that

teaching and learning practices apply three principles of UDL—multiple

means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (Black,

Weinberg,& Brodwin, 2015; Rose, Harbour, Johnston, Daley, &

Abarbanell, 2006).

Common characteristics of any UD practice are accessibility, usability,

and inclusiveness, as illustrated in Fig. 3.1. UD is positioned as inclusive

because it values diversity, equity, and integration (Hockings, 2010). This

approach provides a way to conceptualize these common characteristics

a routine part of the design of campus-wide applications rather than bein

Fig. 3.1 Characteristics

of a UD strategy: It is

accessible, usable, and

inclusive. (Burgstahler,

2015, p. 15)

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

49

considered as after-thoughts once an individual with a disability encoun-

ters a barrier (Burgstahler, 2015).

Universal Design in Higher Education (UDHE): A Specific

Application of UD

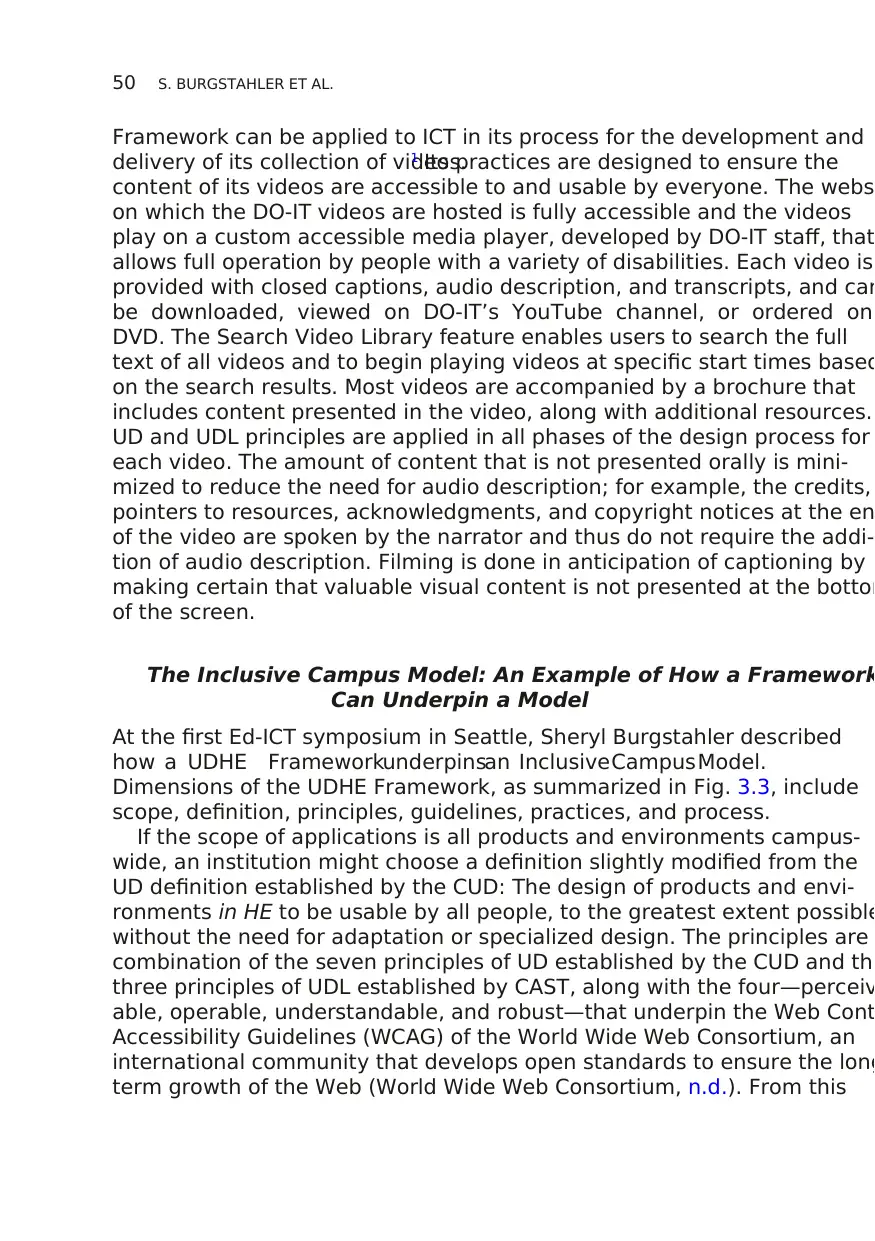

The terminology: ‘Universal Design in Higher Education’ (UDHE) was

adopted by a team of collaborators in several projects at the University o

Washington (UW) that were funded by the US Department of Education

(grants OPE #s P33A990042, P333AO20044, and P333A050064).

UDHE builds upon a total of ten principles drawn from UD and UDL

that allow for a wide range of possible applications in HE, not only in

teaching and learning, but also in other functional areas such as outdoor

spaces, administrative websites and services (Burgstahler, 2015). For all

specific applications, the ultimate goal of these proactive practices is acc

for everyone. The UDHE Framework makes clear that applying UD and

UDL principles campus-wide does not eradicate the need for accommoda

tions; it minimizes their necessity and thus reduces the need for students

with disabilities to make special requests for them (Hadley, 2011). As the

two images presented in Fig. 3.2 illustrate, greater applications of UDHE

(including those relevant to ICT) on a campus result in the provision of

fewer accommodations (including the provision of AT).

The Disabilities,Opportunities,Internetworkingand Technology

(DO-IT) Center at the UW provides an example of how the UDHE

UDHE

Accommodations

UDHE

Accommodations

Fig. 3.2 Relationship of the level of access provided through UD versus accom-

modations of a campus that primarily embrace the accommodation framew

compared to one that promotes UD

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

considered as after-thoughts once an individual with a disability encoun-

ters a barrier (Burgstahler, 2015).

Universal Design in Higher Education (UDHE): A Specific

Application of UD

The terminology: ‘Universal Design in Higher Education’ (UDHE) was

adopted by a team of collaborators in several projects at the University o

Washington (UW) that were funded by the US Department of Education

(grants OPE #s P33A990042, P333AO20044, and P333A050064).

UDHE builds upon a total of ten principles drawn from UD and UDL

that allow for a wide range of possible applications in HE, not only in

teaching and learning, but also in other functional areas such as outdoor

spaces, administrative websites and services (Burgstahler, 2015). For all

specific applications, the ultimate goal of these proactive practices is acc

for everyone. The UDHE Framework makes clear that applying UD and

UDL principles campus-wide does not eradicate the need for accommoda

tions; it minimizes their necessity and thus reduces the need for students

with disabilities to make special requests for them (Hadley, 2011). As the

two images presented in Fig. 3.2 illustrate, greater applications of UDHE

(including those relevant to ICT) on a campus result in the provision of

fewer accommodations (including the provision of AT).

The Disabilities,Opportunities,Internetworkingand Technology

(DO-IT) Center at the UW provides an example of how the UDHE

UDHE

Accommodations

UDHE

Accommodations

Fig. 3.2 Relationship of the level of access provided through UD versus accom-

modations of a campus that primarily embrace the accommodation framew

compared to one that promotes UD

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

50

Framework can be applied to ICT in its process for the development and

delivery of its collection of videos.1 Its practices are designed to ensure the

content of its videos are accessible to and usable by everyone. The webs

on which the DO-IT videos are hosted is fully accessible and the videos

play on a custom accessible media player, developed by DO-IT staff, that

allows full operation by people with a variety of disabilities. Each video is

provided with closed captions, audio description, and transcripts, and can

be downloaded, viewed on DO-IT’s YouTube channel, or ordered on

DVD. The Search Video Library feature enables users to search the full

text of all videos and to begin playing videos at specific start times based

on the search results. Most videos are accompanied by a brochure that

includes content presented in the video, along with additional resources.

UD and UDL principles are applied in all phases of the design process for

each video. The amount of content that is not presented orally is mini-

mized to reduce the need for audio description; for example, the credits,

pointers to resources, acknowledgments, and copyright notices at the en

of the video are spoken by the narrator and thus do not require the addi-

tion of audio description. Filming is done in anticipation of captioning by

making certain that valuable visual content is not presented at the bottom

of the screen.

The Inclusive Campus Model: An Example of How a Framework

Can Underpin a Model

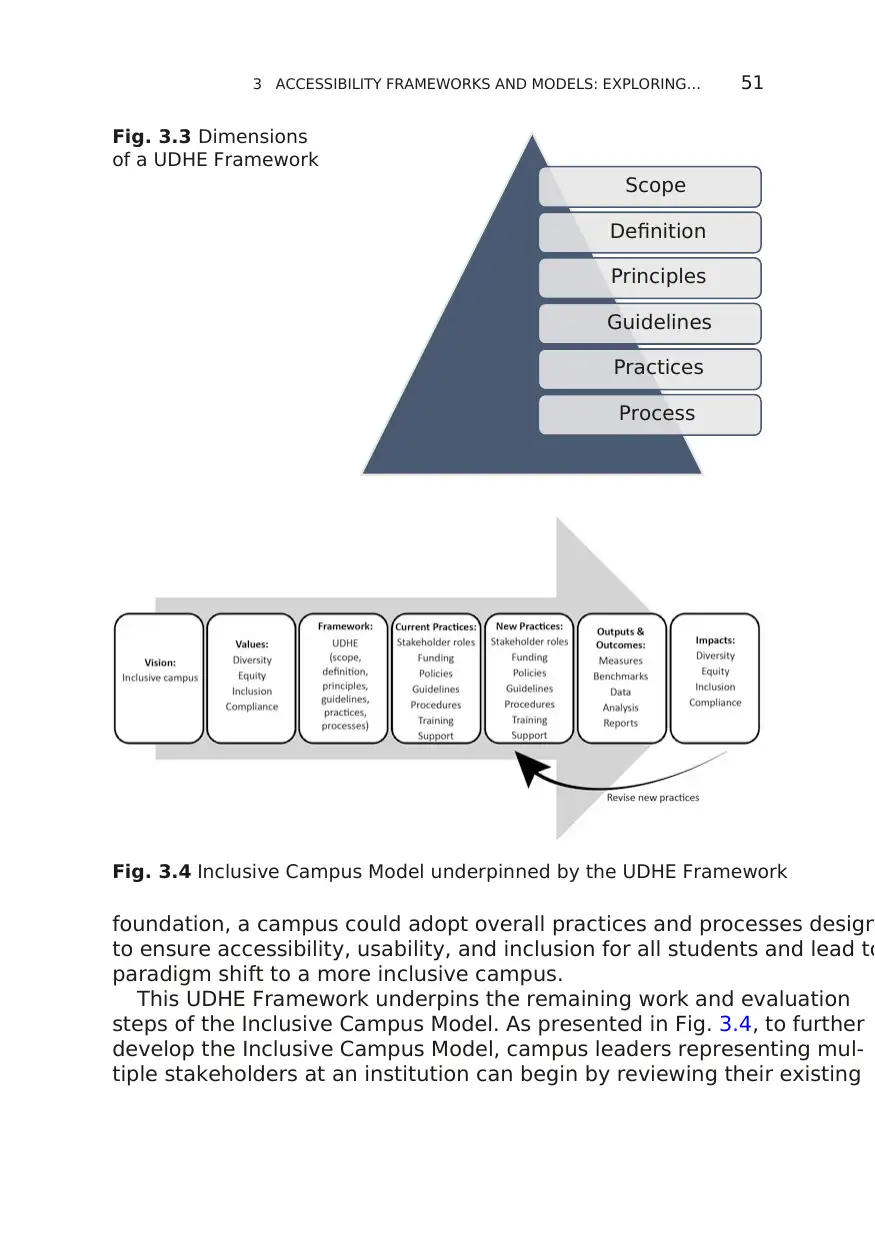

At the first Ed-ICT symposium in Seattle, Sheryl Burgstahler described

how a UDHE Frameworkunderpinsan Inclusive Campus Model.

Dimensions of the UDHE Framework, as summarized in Fig. 3.3, include

scope, definition, principles, guidelines, practices, and process.

If the scope of applications is all products and environments campus-

wide, an institution might choose a definition slightly modified from the

UD definition established by the CUD: The design of products and envi-

ronments in HE to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible

without the need for adaptation or specialized design. The principles are

combination of the seven principles of UD established by the CUD and the

three principles of UDL established by CAST, along with the four—perceiv

able, operable, understandable, and robust—that underpin the Web Cont

Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) of the World Wide Web Consortium, an

international community that develops open standards to ensure the long

term growth of the Web (World Wide Web Consortium, n.d.). From this

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

Framework can be applied to ICT in its process for the development and

delivery of its collection of videos.1 Its practices are designed to ensure the

content of its videos are accessible to and usable by everyone. The webs

on which the DO-IT videos are hosted is fully accessible and the videos

play on a custom accessible media player, developed by DO-IT staff, that

allows full operation by people with a variety of disabilities. Each video is

provided with closed captions, audio description, and transcripts, and can

be downloaded, viewed on DO-IT’s YouTube channel, or ordered on

DVD. The Search Video Library feature enables users to search the full

text of all videos and to begin playing videos at specific start times based

on the search results. Most videos are accompanied by a brochure that

includes content presented in the video, along with additional resources.

UD and UDL principles are applied in all phases of the design process for

each video. The amount of content that is not presented orally is mini-

mized to reduce the need for audio description; for example, the credits,

pointers to resources, acknowledgments, and copyright notices at the en

of the video are spoken by the narrator and thus do not require the addi-

tion of audio description. Filming is done in anticipation of captioning by

making certain that valuable visual content is not presented at the bottom

of the screen.

The Inclusive Campus Model: An Example of How a Framework

Can Underpin a Model

At the first Ed-ICT symposium in Seattle, Sheryl Burgstahler described

how a UDHE Frameworkunderpinsan Inclusive Campus Model.

Dimensions of the UDHE Framework, as summarized in Fig. 3.3, include

scope, definition, principles, guidelines, practices, and process.

If the scope of applications is all products and environments campus-

wide, an institution might choose a definition slightly modified from the

UD definition established by the CUD: The design of products and envi-

ronments in HE to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible

without the need for adaptation or specialized design. The principles are

combination of the seven principles of UD established by the CUD and the

three principles of UDL established by CAST, along with the four—perceiv

able, operable, understandable, and robust—that underpin the Web Cont

Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) of the World Wide Web Consortium, an

international community that develops open standards to ensure the long

term growth of the Web (World Wide Web Consortium, n.d.). From this

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

51

foundation, a campus could adopt overall practices and processes design

to ensure accessibility, usability, and inclusion for all students and lead to

paradigm shift to a more inclusive campus.

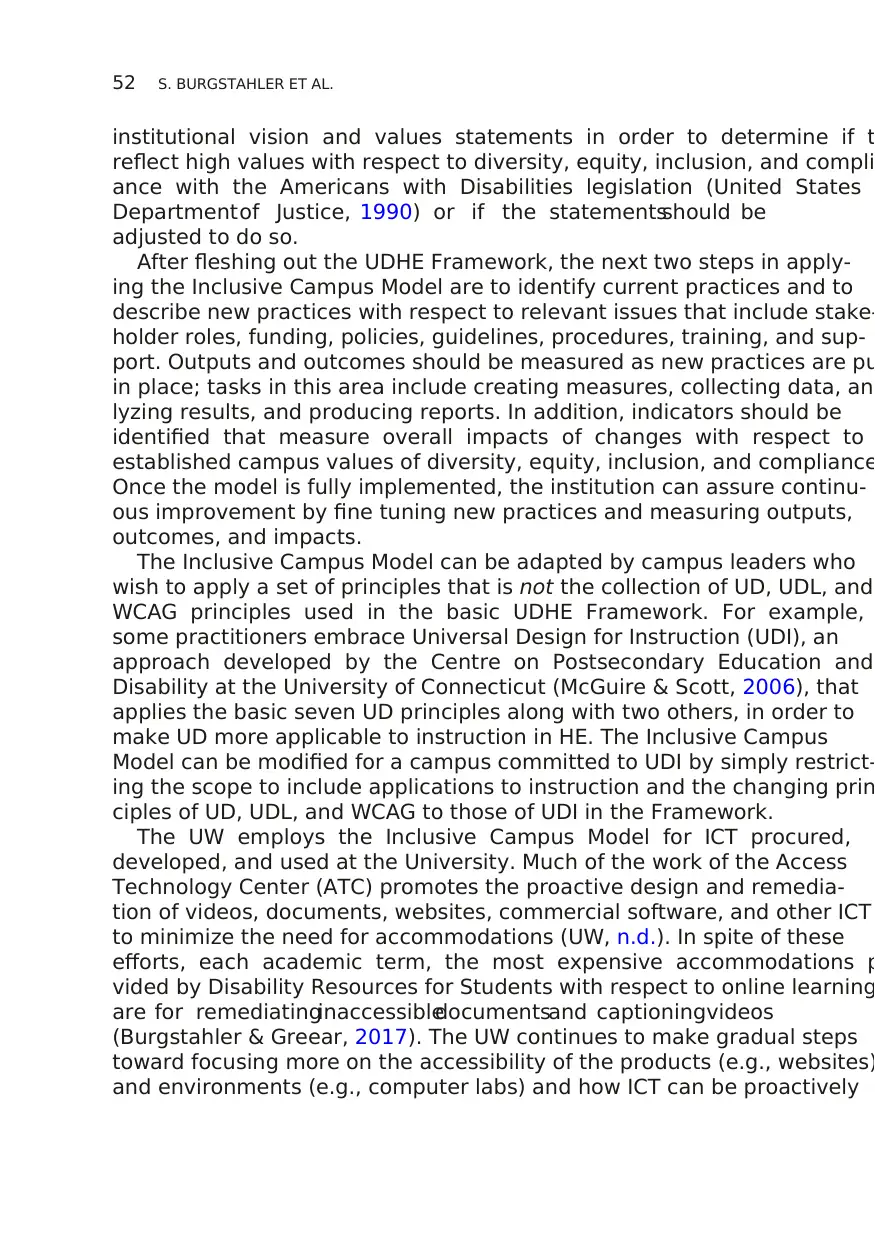

This UDHE Framework underpins the remaining work and evaluation

steps of the Inclusive Campus Model. As presented in Fig. 3.4, to further

develop the Inclusive Campus Model, campus leaders representing mul-

tiple stakeholders at an institution can begin by reviewing their existing

Scope

Definition

Principles

Guidelines

Practices

Process

Fig. 3.3 Dimensions

of a UDHE Framework

Fig. 3.4 Inclusive Campus Model underpinned by the UDHE Framework

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

foundation, a campus could adopt overall practices and processes design

to ensure accessibility, usability, and inclusion for all students and lead to

paradigm shift to a more inclusive campus.

This UDHE Framework underpins the remaining work and evaluation

steps of the Inclusive Campus Model. As presented in Fig. 3.4, to further

develop the Inclusive Campus Model, campus leaders representing mul-

tiple stakeholders at an institution can begin by reviewing their existing

Scope

Definition

Principles

Guidelines

Practices

Process

Fig. 3.3 Dimensions

of a UDHE Framework

Fig. 3.4 Inclusive Campus Model underpinned by the UDHE Framework

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

52

institutional vision and values statements in order to determine if t

reflect high values with respect to diversity, equity, inclusion, and compli

ance with the Americans with Disabilities legislation (United States

Department of Justice, 1990) or if the statementsshould be

adjusted to do so.

After fleshing out the UDHE Framework, the next two steps in apply-

ing the Inclusive Campus Model are to identify current practices and to

describe new practices with respect to relevant issues that include stake-

holder roles, funding, policies, guidelines, procedures, training, and sup-

port. Outputs and outcomes should be measured as new practices are pu

in place; tasks in this area include creating measures, collecting data, ana

lyzing results, and producing reports. In addition, indicators should be

identified that measure overall impacts of changes with respect to

established campus values of diversity, equity, inclusion, and compliance

Once the model is fully implemented, the institution can assure continu-

ous improvement by fine tuning new practices and measuring outputs,

outcomes, and impacts.

The Inclusive Campus Model can be adapted by campus leaders who

wish to apply a set of principles that is not the collection of UD, UDL, and

WCAG principles used in the basic UDHE Framework. For example,

some practitioners embrace Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), an

approach developed by the Centre on Postsecondary Education and

Disability at the University of Connecticut (McGuire & Scott, 2006), that

applies the basic seven UD principles along with two others, in order to

make UD more applicable to instruction in HE. The Inclusive Campus

Model can be modified for a campus committed to UDI by simply restrict-

ing the scope to include applications to instruction and the changing prin

ciples of UD, UDL, and WCAG to those of UDI in the Framework.

The UW employs the Inclusive Campus Model for ICT procured,

developed, and used at the University. Much of the work of the Access

Technology Center (ATC) promotes the proactive design and remedia-

tion of videos, documents, websites, commercial software, and other ICT

to minimize the need for accommodations (UW, n.d.). In spite of these

efforts, each academic term, the most expensive accommodations p

vided by Disability Resources for Students with respect to online learning

are for remediatinginaccessibledocumentsand captioningvideos

(Burgstahler & Greear, 2017). The UW continues to make gradual steps

toward focusing more on the accessibility of the products (e.g., websites)

and environments (e.g., computer labs) and how ICT can be proactively

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

institutional vision and values statements in order to determine if t

reflect high values with respect to diversity, equity, inclusion, and compli

ance with the Americans with Disabilities legislation (United States

Department of Justice, 1990) or if the statementsshould be

adjusted to do so.

After fleshing out the UDHE Framework, the next two steps in apply-

ing the Inclusive Campus Model are to identify current practices and to

describe new practices with respect to relevant issues that include stake-

holder roles, funding, policies, guidelines, procedures, training, and sup-

port. Outputs and outcomes should be measured as new practices are pu

in place; tasks in this area include creating measures, collecting data, ana

lyzing results, and producing reports. In addition, indicators should be

identified that measure overall impacts of changes with respect to

established campus values of diversity, equity, inclusion, and compliance

Once the model is fully implemented, the institution can assure continu-

ous improvement by fine tuning new practices and measuring outputs,

outcomes, and impacts.

The Inclusive Campus Model can be adapted by campus leaders who

wish to apply a set of principles that is not the collection of UD, UDL, and

WCAG principles used in the basic UDHE Framework. For example,

some practitioners embrace Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), an

approach developed by the Centre on Postsecondary Education and

Disability at the University of Connecticut (McGuire & Scott, 2006), that

applies the basic seven UD principles along with two others, in order to

make UD more applicable to instruction in HE. The Inclusive Campus

Model can be modified for a campus committed to UDI by simply restrict-

ing the scope to include applications to instruction and the changing prin

ciples of UD, UDL, and WCAG to those of UDI in the Framework.

The UW employs the Inclusive Campus Model for ICT procured,

developed, and used at the University. Much of the work of the Access

Technology Center (ATC) promotes the proactive design and remedia-

tion of videos, documents, websites, commercial software, and other ICT

to minimize the need for accommodations (UW, n.d.). In spite of these

efforts, each academic term, the most expensive accommodations p

vided by Disability Resources for Students with respect to online learning

are for remediatinginaccessibledocumentsand captioningvideos

(Burgstahler & Greear, 2017). The UW continues to make gradual steps

toward focusing more on the accessibility of the products (e.g., websites)

and environments (e.g., computer labs) and how ICT can be proactively

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

53

designed to be accessible to a broad audience. Nationwide, resolutions to

the hundreds of lawsuits and civil right complaints brought to the Office

of Civil Rights, the Department of Justice, and courts of law have pro-

moted this approach, as legislation has required that associated institu-

tions proactively design their websites, videos, documents, and other ICT

to be accessible(Beaver, 2017; Sieben-Schneider& Hamilton-

Brodie, 2016).

Anecdotal evidence gleaned from the Ed-ICT collaborative meetings,

at conferences, and from reports in the literature suggests an increasing

interest in UD, UDL, UDHE, or similar frameworks built on UD. For

example, in the first Ed-ICT symposium in Seattle, Alice Havel presented

another example of a framework that integrates medical and social mode

of disability, along with the addition of accommodations and univers

design.2 The Human Development Model-Disability Creation Process

(HDM-DCP) is based on the work of Fougeyrollas (International Network

on the Disability Creation Process, n.d.). This conceptual model, not well

known outside Quebec, does not downplay the impact of an impairment

itself and expounds that life skills are achieved not only by enhancing abi

ties and compensating for disabilities, but also by reducing environmenta

obstacles. It is similar to the International Classification of Impairments,

Disabilities, and Handicaps published by the World Health Organization

(World Health Organization, 2018), which is still used in some countries

today. Although the HDM-DCP model, along with its classification sys-

tem, is employed by many health, rehabilitation, and social service organ

zations in Quebec, it has had limited influence on HE. This may be due to

a pragmatic reason: eligibility for government funding of disability service

in colleges and universities is based exclusively on a medical model. In

addition, the complexity of implementing the HDM-DCP model brings

no obvious advantages for students, faculty, or service providers. For var

ous reasons, mostly financial, government guidelines for service delivery

strongly suggest a needs-based organizational model when determining

accommodations, taking into account a student’s strengths, abilities, and

needs, while at the same time emphasizing the necessity to eliminate en

ronmental barriers. In spite of the energy dedicated to developing a uniqu

Quebec approach, due to the significant increase in the number of stu-

dents with disabilities in HE, the prohibitive cost of psycho-educational

assessments for diagnosing a learning disability and the desire for a more

diverse and inclusive society, many service providers and a growing num

ber of faculty are now seriously exploring the UD framework. Sever

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

designed to be accessible to a broad audience. Nationwide, resolutions to

the hundreds of lawsuits and civil right complaints brought to the Office

of Civil Rights, the Department of Justice, and courts of law have pro-

moted this approach, as legislation has required that associated institu-

tions proactively design their websites, videos, documents, and other ICT

to be accessible(Beaver, 2017; Sieben-Schneider& Hamilton-

Brodie, 2016).

Anecdotal evidence gleaned from the Ed-ICT collaborative meetings,

at conferences, and from reports in the literature suggests an increasing

interest in UD, UDL, UDHE, or similar frameworks built on UD. For

example, in the first Ed-ICT symposium in Seattle, Alice Havel presented

another example of a framework that integrates medical and social mode

of disability, along with the addition of accommodations and univers

design.2 The Human Development Model-Disability Creation Process

(HDM-DCP) is based on the work of Fougeyrollas (International Network

on the Disability Creation Process, n.d.). This conceptual model, not well

known outside Quebec, does not downplay the impact of an impairment

itself and expounds that life skills are achieved not only by enhancing abi

ties and compensating for disabilities, but also by reducing environmenta

obstacles. It is similar to the International Classification of Impairments,

Disabilities, and Handicaps published by the World Health Organization

(World Health Organization, 2018), which is still used in some countries

today. Although the HDM-DCP model, along with its classification sys-

tem, is employed by many health, rehabilitation, and social service organ

zations in Quebec, it has had limited influence on HE. This may be due to

a pragmatic reason: eligibility for government funding of disability service

in colleges and universities is based exclusively on a medical model. In

addition, the complexity of implementing the HDM-DCP model brings

no obvious advantages for students, faculty, or service providers. For var

ous reasons, mostly financial, government guidelines for service delivery

strongly suggest a needs-based organizational model when determining

accommodations, taking into account a student’s strengths, abilities, and

needs, while at the same time emphasizing the necessity to eliminate en

ronmental barriers. In spite of the energy dedicated to developing a uniqu

Quebec approach, due to the significant increase in the number of stu-

dents with disabilities in HE, the prohibitive cost of psycho-educational

assessments for diagnosing a learning disability and the desire for a more

diverse and inclusive society, many service providers and a growing num

ber of faculty are now seriously exploring the UD framework. Sever

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

54

province-wide organizations have created websites to support this trend

implement UDL across French and English Quebec colleges and universi-

ties (CAPRES, 2015; Portail du réseau collegial du Québec, 2016; McGill

University3).

Despite the increasing interest in UD or similar frameworks, the vast

majority of campuses world-wide primarily adopt an accommodation

only framework in their designs of disability service offerings. Even when

there are widely accepted guidelines, such as WCAG in the case of ICT,

focus is on compliance (e.g., what do we need to do to be “ADA compli-

ant”?) rather than moving beyond compliance and accommodations to

embrace UD practices to ensure ICT is not just accessible, but also usable

and inclusive.

Do we n eeD someThIng o Ther Than (or In aDDITIon

To ) exIsTIng Frameworks anD assoCIaTeD moDels

In o rDer To aCTIvaTe a ParaDIgm shIFT TowarD more

I nClusIve ICT anD PraCTICes ?

In the first Ed-ICT Symposium, Jane Seale (2017) proposed that existing

frameworks and associated models might be replaced, or at least enriche

if they incorporated wider views of the HE context. She presented the

results of a literature review that identified additional models that were

considered relevant to the provision of ICT in HE, but which were cur-

rently widely ignored. She argued that the field might further progress if

practitioners and researchers considered how aspects of models could co

tribute something beyond accommodations-only and UD frameworks for

underpinning practices toward a stance that considers the possibility that

best practices might emerge from combining a number of frameworks an

models that take into account issues perhaps not yet widely considered.

this section, we briefly outline seven frameworks and models and contras

them to one another and to the Inclusive Campus Model (which is under-

pinned by a UDHE Framework) and share how additional views on acces-

sibility—such as adaptability, integration and segregation, change agents

and holistic approaches—can inform future research and practice.

The Holistic Model of Accessibility for e-Learning Applications

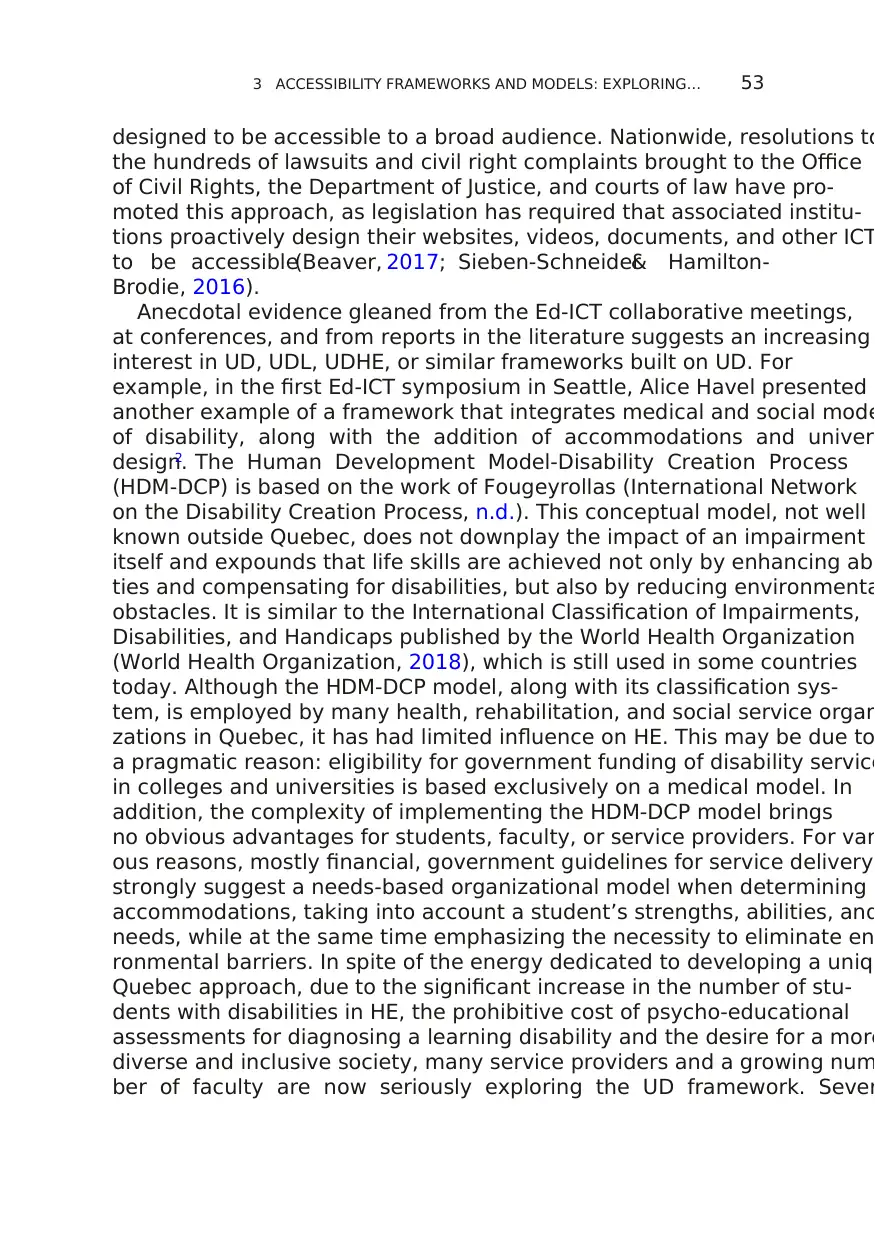

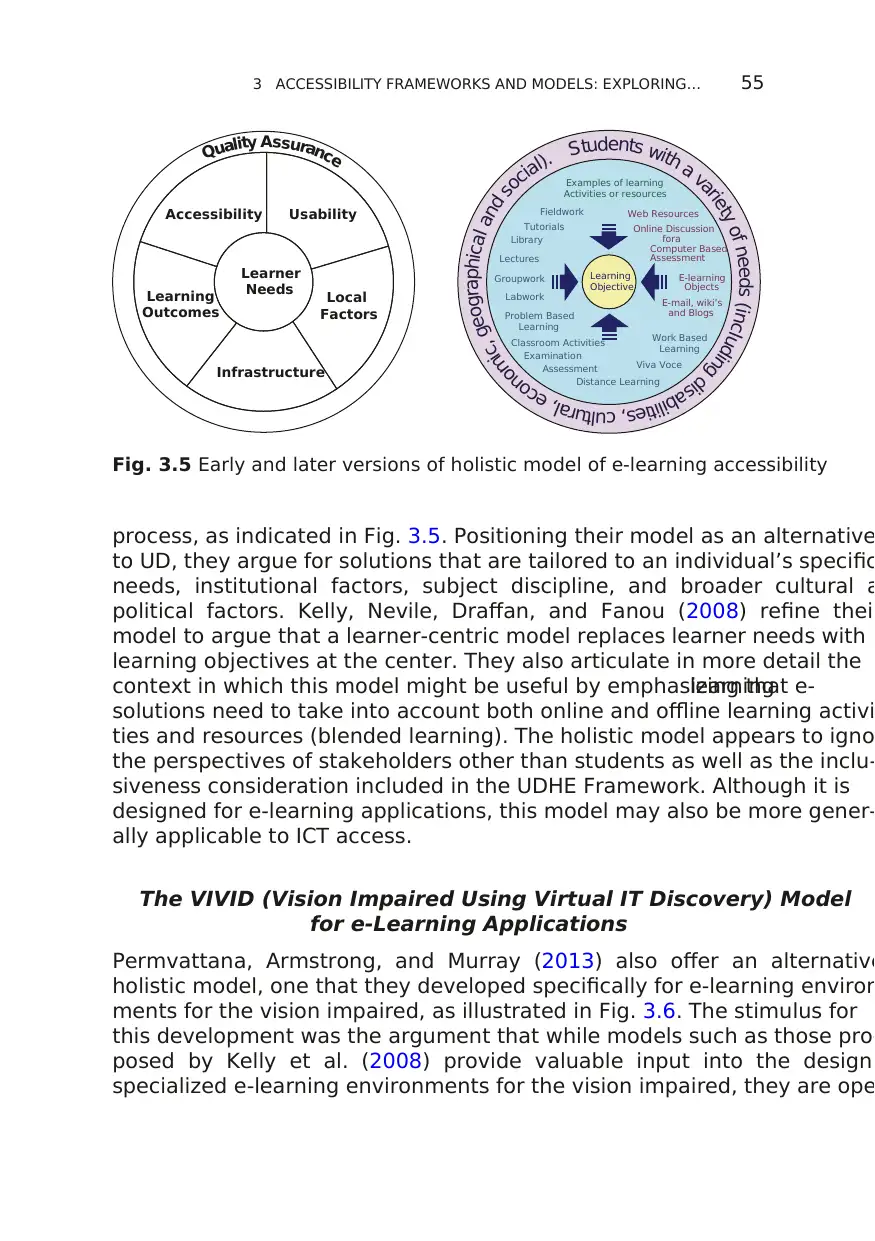

Kelly, Phipps, and Swift (2004) proposed a holistic model for e-learning

accessibility, which places the learner at the center of the developm

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

province-wide organizations have created websites to support this trend

implement UDL across French and English Quebec colleges and universi-

ties (CAPRES, 2015; Portail du réseau collegial du Québec, 2016; McGill

University3).

Despite the increasing interest in UD or similar frameworks, the vast

majority of campuses world-wide primarily adopt an accommodation

only framework in their designs of disability service offerings. Even when

there are widely accepted guidelines, such as WCAG in the case of ICT,

focus is on compliance (e.g., what do we need to do to be “ADA compli-

ant”?) rather than moving beyond compliance and accommodations to

embrace UD practices to ensure ICT is not just accessible, but also usable

and inclusive.

Do we n eeD someThIng o Ther Than (or In aDDITIon

To ) exIsTIng Frameworks anD assoCIaTeD moDels

In o rDer To aCTIvaTe a ParaDIgm shIFT TowarD more

I nClusIve ICT anD PraCTICes ?

In the first Ed-ICT Symposium, Jane Seale (2017) proposed that existing

frameworks and associated models might be replaced, or at least enriche

if they incorporated wider views of the HE context. She presented the

results of a literature review that identified additional models that were

considered relevant to the provision of ICT in HE, but which were cur-

rently widely ignored. She argued that the field might further progress if

practitioners and researchers considered how aspects of models could co

tribute something beyond accommodations-only and UD frameworks for

underpinning practices toward a stance that considers the possibility that

best practices might emerge from combining a number of frameworks an

models that take into account issues perhaps not yet widely considered.

this section, we briefly outline seven frameworks and models and contras

them to one another and to the Inclusive Campus Model (which is under-

pinned by a UDHE Framework) and share how additional views on acces-

sibility—such as adaptability, integration and segregation, change agents

and holistic approaches—can inform future research and practice.

The Holistic Model of Accessibility for e-Learning Applications

Kelly, Phipps, and Swift (2004) proposed a holistic model for e-learning

accessibility, which places the learner at the center of the developm

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

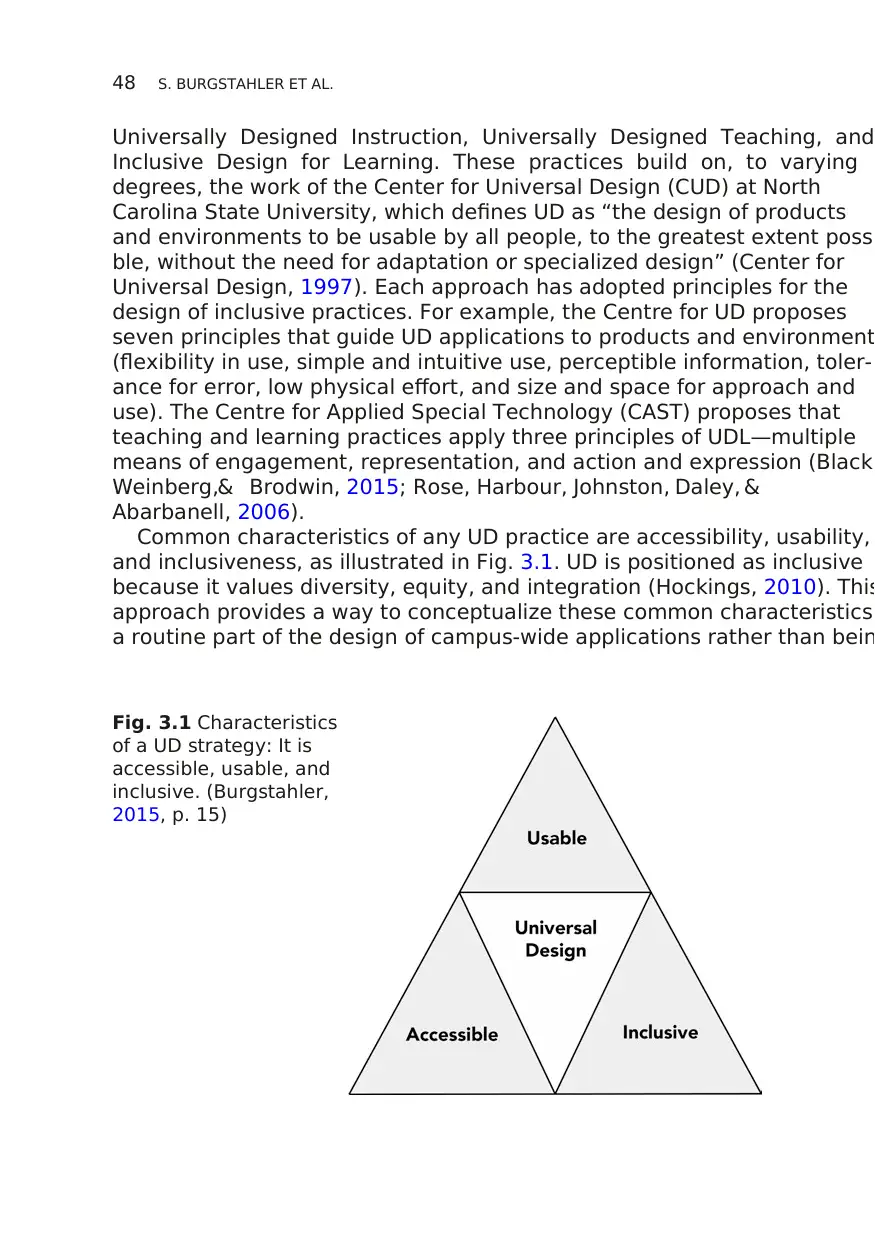

55

process, as indicated in Fig. 3.5. Positioning their model as an alternative

to UD, they argue for solutions that are tailored to an individual’s specific

needs, institutional factors, subject discipline, and broader cultural a

political factors. Kelly, Nevile, Draffan, and Fanou (2008) refine their

model to argue that a learner-centric model replaces learner needs with

learning objectives at the center. They also articulate in more detail the

context in which this model might be useful by emphasizing that e-learning

solutions need to take into account both online and offline learning activi

ties and resources (blended learning). The holistic model appears to igno

the perspectives of stakeholders other than students as well as the inclu-

siveness consideration included in the UDHE Framework. Although it is

designed for e-learning applications, this model may also be more gener-

ally applicable to ICT access.

The VIVID (Vision Impaired Using Virtual IT Discovery) Model

for e-Learning Applications

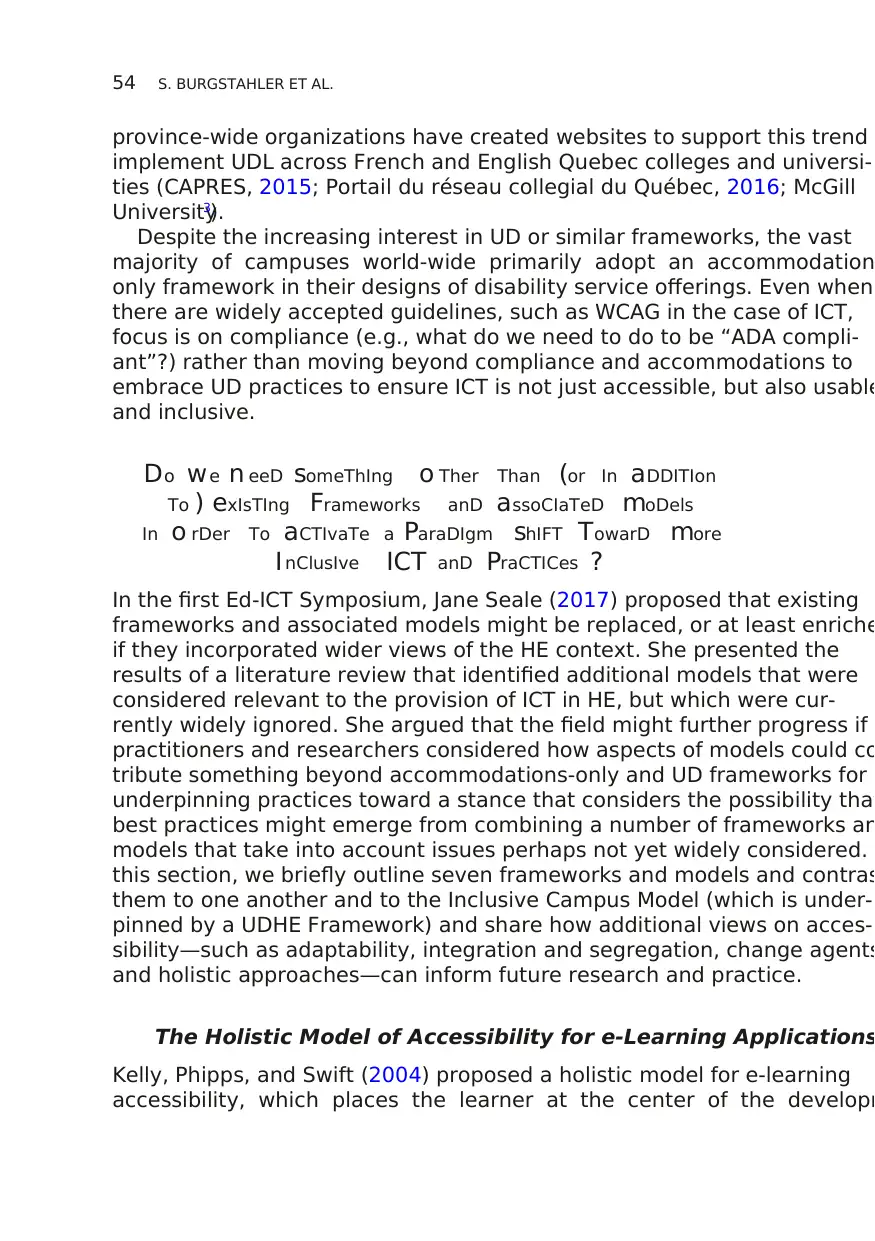

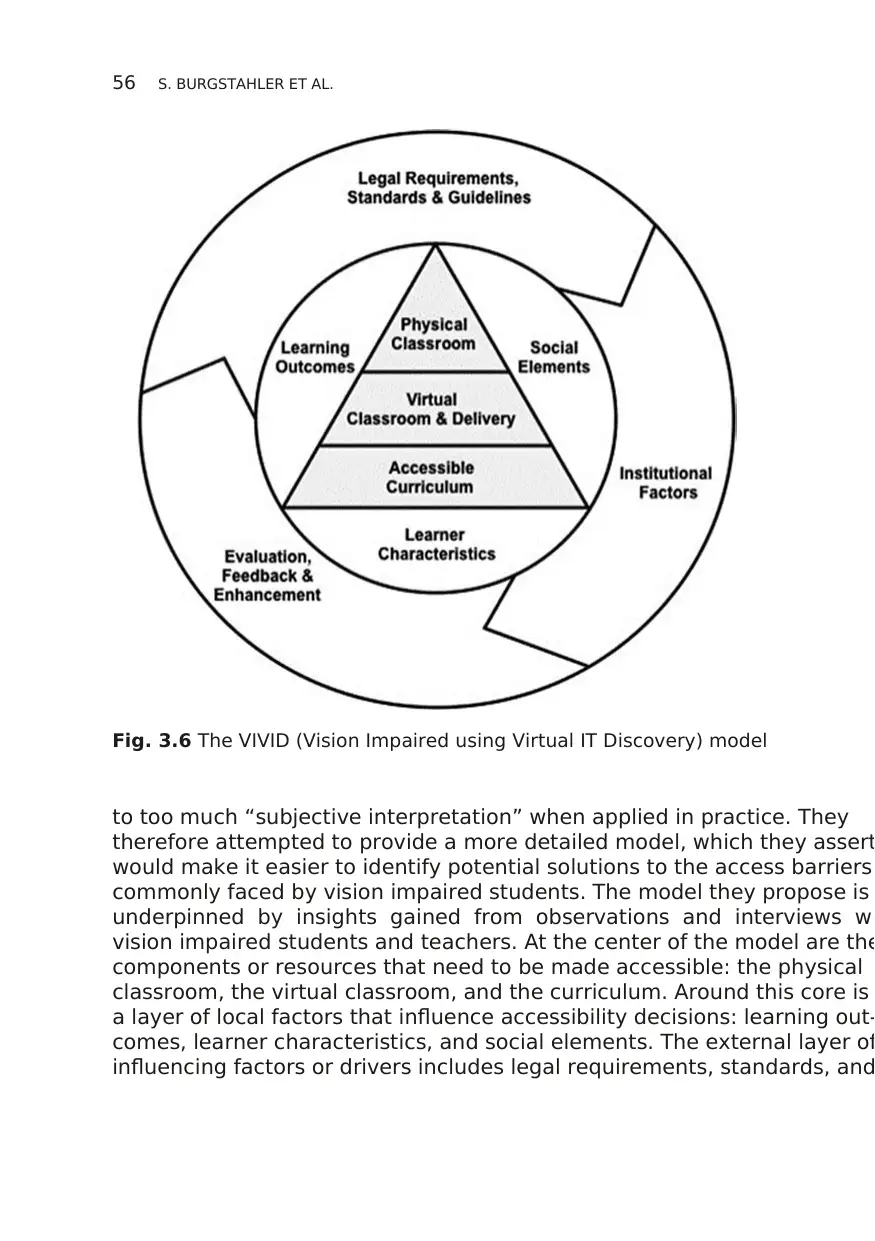

Permvattana, Armstrong, and Murray (2013) also offer an alternative

holistic model, one that they developed specifically for e-learning environ

ments for the vision impaired, as illustrated in Fig. 3.6. The stimulus for

this development was the argument that while models such as those pro-

posed by Kelly et al. (2008) provide valuable input into the design

specialized e-learning environments for the vision impaired, they are ope

Examples of learning

Activities or resources

Fieldwork Web Resources

Online Discussion

fora

E-learning

Objects

E-mail, wiki’s

and Blogs

Computer Based

Assessment

Tutorials

Library

Lectures

Groupwork

Labwork

Problem Based

Learning

Classroom Activities

Examination

Assessment

Distance Learning

Viva Voce

Work Based

Learning

S

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

w

itha

v

a

r

i

e

t

y

o

f

n

e

e

d

s

(

i

n

c

l

u

d

i

n

g

d

i

s

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

,

c

u

l t

u

r

a l , e c o n o

m

i

c

,

g

e

o

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

a

l

a

n

d

s

o

c

i

a

l

)

.

Learning

Objective

Q

u

a

l

i

t

y

A

s

suran

c

e

Accessibility Usability

Infrastructure

Learner

NeedsLearning

Outcomes

Local

Factors

Fig. 3.5 Early and later versions of holistic model of e-learning accessibility

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

process, as indicated in Fig. 3.5. Positioning their model as an alternative

to UD, they argue for solutions that are tailored to an individual’s specific

needs, institutional factors, subject discipline, and broader cultural a

political factors. Kelly, Nevile, Draffan, and Fanou (2008) refine their

model to argue that a learner-centric model replaces learner needs with

learning objectives at the center. They also articulate in more detail the

context in which this model might be useful by emphasizing that e-learning

solutions need to take into account both online and offline learning activi

ties and resources (blended learning). The holistic model appears to igno

the perspectives of stakeholders other than students as well as the inclu-

siveness consideration included in the UDHE Framework. Although it is

designed for e-learning applications, this model may also be more gener-

ally applicable to ICT access.

The VIVID (Vision Impaired Using Virtual IT Discovery) Model

for e-Learning Applications

Permvattana, Armstrong, and Murray (2013) also offer an alternative

holistic model, one that they developed specifically for e-learning environ

ments for the vision impaired, as illustrated in Fig. 3.6. The stimulus for

this development was the argument that while models such as those pro-

posed by Kelly et al. (2008) provide valuable input into the design

specialized e-learning environments for the vision impaired, they are ope

Examples of learning

Activities or resources

Fieldwork Web Resources

Online Discussion

fora

E-learning

Objects

E-mail, wiki’s

and Blogs

Computer Based

Assessment

Tutorials

Library

Lectures

Groupwork

Labwork

Problem Based

Learning

Classroom Activities

Examination

Assessment

Distance Learning

Viva Voce

Work Based

Learning

S

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

w

itha

v

a

r

i

e

t

y

o

f

n

e

e

d

s

(

i

n

c

l

u

d

i

n

g

d

i

s

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

,

c

u

l t

u

r

a l , e c o n o

m

i

c

,

g

e

o

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

a

l

a

n

d

s

o

c

i

a

l

)

.

Learning

Objective

Q

u

a

l

i

t

y

A

s

suran

c

e

Accessibility Usability

Infrastructure

Learner

NeedsLearning

Outcomes

Local

Factors

Fig. 3.5 Early and later versions of holistic model of e-learning accessibility

3 ACCESSIBILITY FRAMEWORKS AND MODELS: EXPLORING…

56

to too much “subjective interpretation” when applied in practice. They

therefore attempted to provide a more detailed model, which they assert

would make it easier to identify potential solutions to the access barriers

commonly faced by vision impaired students. The model they propose is

underpinned by insights gained from observations and interviews wi

vision impaired students and teachers. At the center of the model are the

components or resources that need to be made accessible: the physical

classroom, the virtual classroom, and the curriculum. Around this core is

a layer of local factors that influence accessibility decisions: learning out-

comes, learner characteristics, and social elements. The external layer of

influencing factors or drivers includes legal requirements, standards, and

Fig. 3.6 The VIVID (Vision Impaired using Virtual IT Discovery) model

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

to too much “subjective interpretation” when applied in practice. They

therefore attempted to provide a more detailed model, which they assert

would make it easier to identify potential solutions to the access barriers

commonly faced by vision impaired students. The model they propose is

underpinned by insights gained from observations and interviews wi

vision impaired students and teachers. At the center of the model are the

components or resources that need to be made accessible: the physical

classroom, the virtual classroom, and the curriculum. Around this core is

a layer of local factors that influence accessibility decisions: learning out-

comes, learner characteristics, and social elements. The external layer of

influencing factors or drivers includes legal requirements, standards, and

Fig. 3.6 The VIVID (Vision Impaired using Virtual IT Discovery) model

S. BURGSTAHLER ET AL.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 28

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.