Historical Development and Types of Companies: A Report

VerifiedAdded on 2020/09/18

|64

|29496

|192

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the historical development of company law in Australia, tracing its origins from the British colonies to the Corporations Act 2001. It outlines key milestones such as the Federation of Australia and the establishment of regulatory bodies like ASIC. The report describes the essential characteristics of a company, including the limited liability company and the concept of a separate legal entity. It differentiates between public and private companies, detailing their distinct requirements and obligations. Furthermore, it explores various types of companies operating in Australia, such as companies limited by shares, companies limited by guarantee, unlimited companies, and no liability companies, along with the criteria for small and large private companies. The report also touches on trustee companies and the role of the company constitution and replaceable rules, providing a comprehensive overview of the legal framework governing companies in Australia.

LAW20004- Company Law

Week 1:

• Outline the historical development of corporations law in

Australia

The name corporation is derived from the Latin word corpus, meaning body.

➢ A corporation is a body of persons but with its own legal identity and long-

term existence and ownership of property separate from and beyond the life of

any individual.

➢ Australia was initially comprised of six separate British colonies; each with

their own parliament and law-making powers. Each colony's set of laws were

based on the Companies Act 1862 (UK).

➢ In 1901 the colonies agreed to unite into a federation of states to form the

nation of Australia. Even so, each state still controlled its own corporations

law. For a long time companies had to register separately in each state and

each state had its own stock exchange.

➢ The Corporations Act 2001 reinstated the jurisdiction of the Federal Court

resulting in one centralised set of laws for the whole of Australia. This has

been essential in providing a consistent environment for Australian businesses

to function within.

➢ The Corporations Act makes a formal distinction between ownership and

control of companies.

➢ The corporation Act and company constitutions give shareholders significant

rights.

• Explain the key milestones that contributed to the development of

company law in Australia

• Federation of Australia

• Corporations Act (2001) (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.2

• Australian Securities and Investments Commission (Links to an

external site.)Links to an external site. (ASIC; pp. 10–14)3

• The takeovers panel (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site. (pp.15-16)4

• Australian Securities Exchange (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site. (ASX; pp. 14-15)5

• Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (Links to an external

site.)Links to an external site. (APRA)6

• Australian Accounting Standards Board (Links to an external

site.)Links to an external site. (AASB; p. 17)7

• Financial regulation (pp. 16–18)

• Describe the essential characteristics of a company.

Week 1:

• Outline the historical development of corporations law in

Australia

The name corporation is derived from the Latin word corpus, meaning body.

➢ A corporation is a body of persons but with its own legal identity and long-

term existence and ownership of property separate from and beyond the life of

any individual.

➢ Australia was initially comprised of six separate British colonies; each with

their own parliament and law-making powers. Each colony's set of laws were

based on the Companies Act 1862 (UK).

➢ In 1901 the colonies agreed to unite into a federation of states to form the

nation of Australia. Even so, each state still controlled its own corporations

law. For a long time companies had to register separately in each state and

each state had its own stock exchange.

➢ The Corporations Act 2001 reinstated the jurisdiction of the Federal Court

resulting in one centralised set of laws for the whole of Australia. This has

been essential in providing a consistent environment for Australian businesses

to function within.

➢ The Corporations Act makes a formal distinction between ownership and

control of companies.

➢ The corporation Act and company constitutions give shareholders significant

rights.

• Explain the key milestones that contributed to the development of

company law in Australia

• Federation of Australia

• Corporations Act (2001) (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site.2

• Australian Securities and Investments Commission (Links to an

external site.)Links to an external site. (ASIC; pp. 10–14)3

• The takeovers panel (Links to an external site.)Links to an external

site. (pp.15-16)4

• Australian Securities Exchange (Links to an external site.)Links to an

external site. (ASX; pp. 14-15)5

• Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (Links to an external

site.)Links to an external site. (APRA)6

• Australian Accounting Standards Board (Links to an external

site.)Links to an external site. (AASB; p. 17)7

• Financial regulation (pp. 16–18)

• Describe the essential characteristics of a company.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

• Companies come in all shapes and sizes, from your local small business to

large multinational corporations. They may exist for an extensive range of

purposes, have a variety of shareholders, undertake differing activities and

have variable employee numbers.

• Even so, all companies have some essential core characteristics.

• The modern limited liability company has shaped the way that modern society

functions.

• It allows for the pooling of large sums of capital from investors who buy

shares, for use by entrepreneurs and managers to develop businesses.

• These businesses are the main drivers of employment and wealth in our

society.

• The limited liability company (pp. 29-32)

• The company as a separate legal entity (pp. 33-39)

• Application to subsidiaries (pp. 39–41)

• The corporate 'veil' (pp. 41-42)

• How statute law allows the 'veil' to be lifted (pp. 42-46)

WEEK 2:

1. Understand the differences between different company types.

2. Understand what the company constitution is.

3. Be aware that a constitution with an objects clause, memorandum of

association and articles of association has not been required since 1988.

4. Understand what replaceable rules are. Understand the nature of the ‘contract’

that they create.

5. Understand how replaceable rules can be changed.

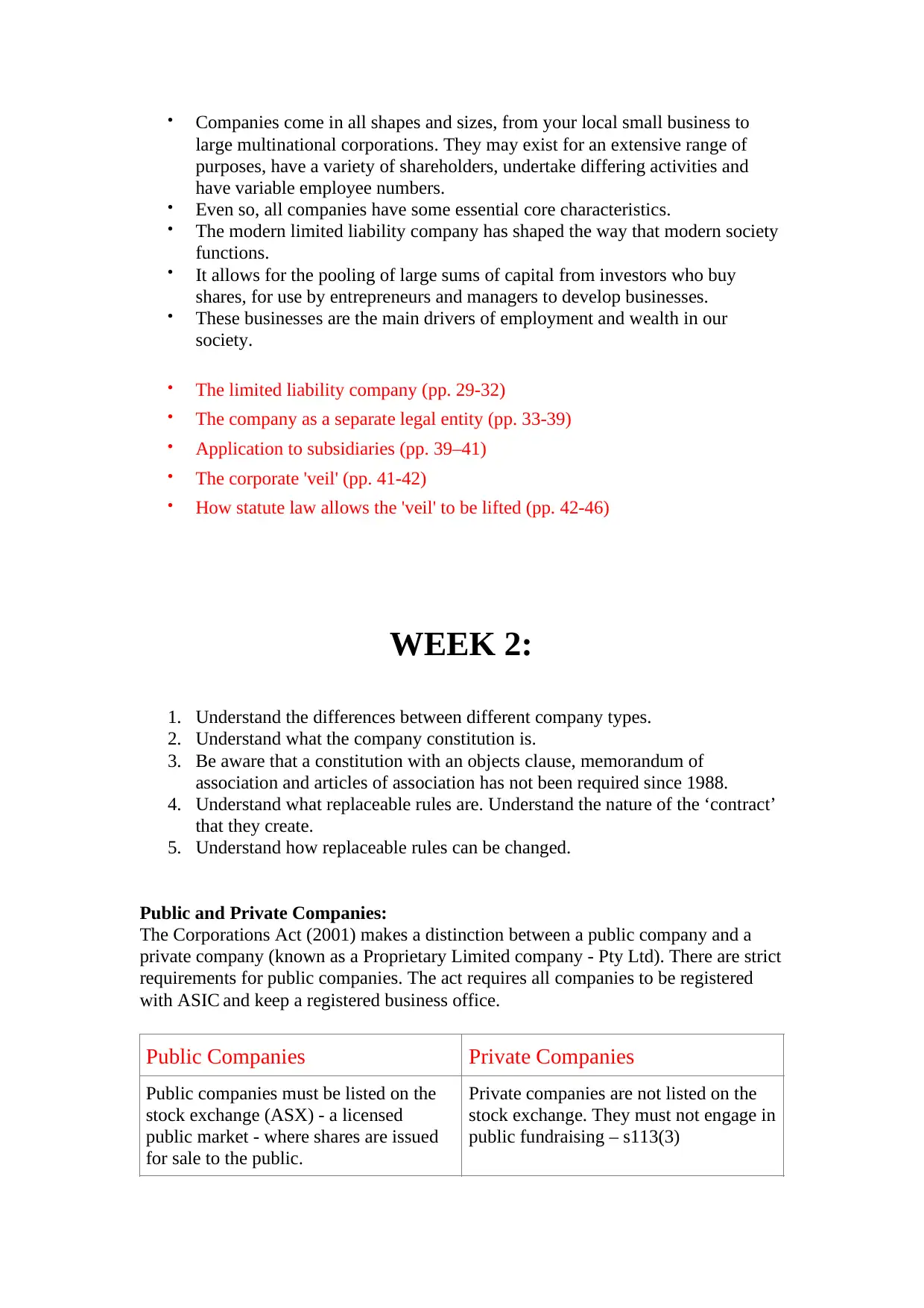

Public and Private Companies:

The Corporations Act (2001) makes a distinction between a public company and a

private company (known as a Proprietary Limited company - Pty Ltd). There are strict

requirements for public companies. The act requires all companies to be registered

with ASIC and keep a registered business office.

Public Companies Private Companies

Public companies must be listed on the

stock exchange (ASX) - a licensed

public market - where shares are issued

for sale to the public.

Private companies are not listed on the

stock exchange. They must not engage in

public fundraising – s113(3)

large multinational corporations. They may exist for an extensive range of

purposes, have a variety of shareholders, undertake differing activities and

have variable employee numbers.

• Even so, all companies have some essential core characteristics.

• The modern limited liability company has shaped the way that modern society

functions.

• It allows for the pooling of large sums of capital from investors who buy

shares, for use by entrepreneurs and managers to develop businesses.

• These businesses are the main drivers of employment and wealth in our

society.

• The limited liability company (pp. 29-32)

• The company as a separate legal entity (pp. 33-39)

• Application to subsidiaries (pp. 39–41)

• The corporate 'veil' (pp. 41-42)

• How statute law allows the 'veil' to be lifted (pp. 42-46)

WEEK 2:

1. Understand the differences between different company types.

2. Understand what the company constitution is.

3. Be aware that a constitution with an objects clause, memorandum of

association and articles of association has not been required since 1988.

4. Understand what replaceable rules are. Understand the nature of the ‘contract’

that they create.

5. Understand how replaceable rules can be changed.

Public and Private Companies:

The Corporations Act (2001) makes a distinction between a public company and a

private company (known as a Proprietary Limited company - Pty Ltd). There are strict

requirements for public companies. The act requires all companies to be registered

with ASIC and keep a registered business office.

Public Companies Private Companies

Public companies must be listed on the

stock exchange (ASX) - a licensed

public market - where shares are issued

for sale to the public.

Private companies are not listed on the

stock exchange. They must not engage in

public fundraising – s113(3)

What types of companies operate in Australia?

• Characteristics of public and private companies (pp. 85-92)

The Corporations act imposes greater disclosure obligations on public companies

because they may raise money from large numbers of people. Family run businesses

are usually able to raise funds from their own internal sources or from lenders.

Both public and private must have at least 1 member s114. Section 113 specifies 50 as

the maximum number of non-employee shareholders of a private company. Public has

no limit.

Private companies are prohibited by s113(3) from engaging in any activity that would

require disclosure to investors under Ch6D. this means that private companies cannot

raise funds by offering its shares or debentures to a large number of people. Public

companies that wish to issue shares, debentures or other securities must comply with

the fundraising provisions CH 6D.

• Companies limited by shares (pp. 80-81)

Most common type of company. A company limited by shares is defined in s9 as a

company formed on the principle of having the liability of its members limited to the

amount, if any, unpaid on the shares respectively held by them.

Public companies must comply with

ASX listing rules – s793C (regular

disclosures).

Private companies are not required to

prepare annual reports and audits (unless

the members request otherwise – s292

but they must still prepare profit and loss

statements

Public companies must hold an Annual

General Meeting (AGM) and publish an

Annual Report for members with a

statement of audited Financial Accounts

s301

Private companies do not have to hold

Annual Meetings.

Public companies must appoint a

Company Secretary as administrator

204A

Private companies are not required to

appoint a Company Secretary as

administrator.

Public companies must have a minimum

of three directors.

Private companies only need one

director and one member. Resolutions

can be passed by the signing of

circulating documents s 249A

For a public company, s203D and s203E

require an ordinary resolution of

members for the removal of any

directors; they cannot be removed by

other directors.

Private companies do not require an

ordinary resolution of members for the

removal of directors.

• Characteristics of public and private companies (pp. 85-92)

The Corporations act imposes greater disclosure obligations on public companies

because they may raise money from large numbers of people. Family run businesses

are usually able to raise funds from their own internal sources or from lenders.

Both public and private must have at least 1 member s114. Section 113 specifies 50 as

the maximum number of non-employee shareholders of a private company. Public has

no limit.

Private companies are prohibited by s113(3) from engaging in any activity that would

require disclosure to investors under Ch6D. this means that private companies cannot

raise funds by offering its shares or debentures to a large number of people. Public

companies that wish to issue shares, debentures or other securities must comply with

the fundraising provisions CH 6D.

• Companies limited by shares (pp. 80-81)

Most common type of company. A company limited by shares is defined in s9 as a

company formed on the principle of having the liability of its members limited to the

amount, if any, unpaid on the shares respectively held by them.

Public companies must comply with

ASX listing rules – s793C (regular

disclosures).

Private companies are not required to

prepare annual reports and audits (unless

the members request otherwise – s292

but they must still prepare profit and loss

statements

Public companies must hold an Annual

General Meeting (AGM) and publish an

Annual Report for members with a

statement of audited Financial Accounts

s301

Private companies do not have to hold

Annual Meetings.

Public companies must appoint a

Company Secretary as administrator

204A

Private companies are not required to

appoint a Company Secretary as

administrator.

Public companies must have a minimum

of three directors.

Private companies only need one

director and one member. Resolutions

can be passed by the signing of

circulating documents s 249A

For a public company, s203D and s203E

require an ordinary resolution of

members for the removal of any

directors; they cannot be removed by

other directors.

Private companies do not require an

ordinary resolution of members for the

removal of directors.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The issue price for a share is determined by agreement between the company and the

investor. Shares may be issued on the basis that the investor pays the entire issue price

in one instalment. Referred to as fully paid shares- shareholder that has these has no

liability to contribute any further amounts to the company.

Partly paid shares- shareholder only pays part of the issue price immediately. Liable

to pay the balance of the issue price if the company makes the call.

The shareholders of a company limited by shares have limited liability, creditors of

such a company do not have access to the personal property of the shareholders in

order to satisfy their debts.

Therefore s148(2) requires the word “limited” or “ltd” as a part of and at the end of its

name. This shows possible creditors that the liability of the shareholders in limited

and debts of the company can only be satisfied from the assets of the company.

• Companies limited by guarantee (pp. 81-84)

A company whose members have their liability limited to the amounts that they have

undertaken to contribute to the property of the company in the event of it being

wound up: s9.

They do not have a share capital so members do not contribute capital while the

company is operating. Still maintain the advantages of being legal entities with the

liability of their members limited to the amount of the guarantee. However if a

company cant meet its liabilities, its members are liable to pay up to the amount

specified as the members’ guarantees: s 517.

The limitation of this type of company is that it does not raise initial or working

capital from its members. Very rarely used for this reason. Used for non-profit

organisations (charities, sporting organisations).

Past members of the company may also be liable if the assets of the company are

insufficient to meet its debts and the present members are unable to meet the

company’s liabilities. Past members only have to contribute to debts from the time

they were involved as members, not debts since they have left.

Companies limited by guarantee do not have share capital so they can not be private

companies, have to be public.

• Unlimited companies (p. 84)

An unlimited company is defined in s 9 as a company whose members have no limit

placed on their liability to the company.

Members are liable in a winding up for the debts of the company without limit if the

company has insufficient assets to meet its debts. Similar to a partnership in a way,

however is considered a separate legal entity.

• No liability companies (pp. 84-85)

A no liability company must:

• Have a share capital

• State in its constitution that its sole objects are mining purposes

• Have no contractual right under its constitution to recover calls made on its

shares from a member who fails to pay a call.

investor. Shares may be issued on the basis that the investor pays the entire issue price

in one instalment. Referred to as fully paid shares- shareholder that has these has no

liability to contribute any further amounts to the company.

Partly paid shares- shareholder only pays part of the issue price immediately. Liable

to pay the balance of the issue price if the company makes the call.

The shareholders of a company limited by shares have limited liability, creditors of

such a company do not have access to the personal property of the shareholders in

order to satisfy their debts.

Therefore s148(2) requires the word “limited” or “ltd” as a part of and at the end of its

name. This shows possible creditors that the liability of the shareholders in limited

and debts of the company can only be satisfied from the assets of the company.

• Companies limited by guarantee (pp. 81-84)

A company whose members have their liability limited to the amounts that they have

undertaken to contribute to the property of the company in the event of it being

wound up: s9.

They do not have a share capital so members do not contribute capital while the

company is operating. Still maintain the advantages of being legal entities with the

liability of their members limited to the amount of the guarantee. However if a

company cant meet its liabilities, its members are liable to pay up to the amount

specified as the members’ guarantees: s 517.

The limitation of this type of company is that it does not raise initial or working

capital from its members. Very rarely used for this reason. Used for non-profit

organisations (charities, sporting organisations).

Past members of the company may also be liable if the assets of the company are

insufficient to meet its debts and the present members are unable to meet the

company’s liabilities. Past members only have to contribute to debts from the time

they were involved as members, not debts since they have left.

Companies limited by guarantee do not have share capital so they can not be private

companies, have to be public.

• Unlimited companies (p. 84)

An unlimited company is defined in s 9 as a company whose members have no limit

placed on their liability to the company.

Members are liable in a winding up for the debts of the company without limit if the

company has insufficient assets to meet its debts. Similar to a partnership in a way,

however is considered a separate legal entity.

• No liability companies (pp. 84-85)

A no liability company must:

• Have a share capital

• State in its constitution that its sole objects are mining purposes

• Have no contractual right under its constitution to recover calls made on its

shares from a member who fails to pay a call.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A no liability company is prohibited from engaging in activities that are outside its

mining purposes objectives s 112(3). The name must contain “no liability” or “NL”

s148(4).

Shares in a no liability company are issued on the basis that if a company is wound

up, any surplus must be distributed among the shareholders in proportion to the

number of shares held by them irrespective of the amounts paid up.

• Large and small private companies (pp. 90-92).

Under s 45A(2) a private company is regarded as a small private company for a

financial year if it satisfies at least 2 of the following criteria:

1. The consolidated operating revenue for the financial year of the company and the

entities it controls in less than $25 million;

2. The value of the consolidated gross assets at the end of the financial year of the

company and the entities it controls is less than 12.5 million;

3. The company and the entities it controls have fewer than 50 employees at the end

of the financial year.

The first 2 criteria are calculated in accordance with applicable accounting standards s

45A(6).

In counting employees for purposes of the s 45A definition, part-time are taken into

account as an appropriate fraction of a full-time equivalent s 45A(5).

The main advantages of the small private companies are:

• They are subject to fewer requirements in relation to preparation, lodgement

and audit of financial reports.

• Not required to prepare annual financial reports or appoint an auditor.

Significant saving costs. (the only need to provide them is if the shareholders

vote for them, or they are asked by ASIC).

• They are required to prepare profit and loss statements for taxation purposes.

• Company audits (p. 89).

• Public companies and large private companies must appoint an independent

auditor to audit their financial reports. In some circumstances ASIC may

relieve a large private company from the requirement to appoint an auditor.

Trustee Companies: (page 98-99)

• The development of Equity Law in the 16th century saw the creation of the Law

of Trusts for charitable institutions.

• The concept of a trust has expanded and is widely used in modern business and

corporations.

• In a trust, a trustee is appointed to hold and manage property on behalf of

beneficiaries.

• A trustee can be liable for shortfalls in the trust funds.

• As companies are considered a separate legal entity they can act as a trustee of a

managed fund. Companies are used because of their limited liability, tax benefits

and perpetual succession.

mining purposes objectives s 112(3). The name must contain “no liability” or “NL”

s148(4).

Shares in a no liability company are issued on the basis that if a company is wound

up, any surplus must be distributed among the shareholders in proportion to the

number of shares held by them irrespective of the amounts paid up.

• Large and small private companies (pp. 90-92).

Under s 45A(2) a private company is regarded as a small private company for a

financial year if it satisfies at least 2 of the following criteria:

1. The consolidated operating revenue for the financial year of the company and the

entities it controls in less than $25 million;

2. The value of the consolidated gross assets at the end of the financial year of the

company and the entities it controls is less than 12.5 million;

3. The company and the entities it controls have fewer than 50 employees at the end

of the financial year.

The first 2 criteria are calculated in accordance with applicable accounting standards s

45A(6).

In counting employees for purposes of the s 45A definition, part-time are taken into

account as an appropriate fraction of a full-time equivalent s 45A(5).

The main advantages of the small private companies are:

• They are subject to fewer requirements in relation to preparation, lodgement

and audit of financial reports.

• Not required to prepare annual financial reports or appoint an auditor.

Significant saving costs. (the only need to provide them is if the shareholders

vote for them, or they are asked by ASIC).

• They are required to prepare profit and loss statements for taxation purposes.

• Company audits (p. 89).

• Public companies and large private companies must appoint an independent

auditor to audit their financial reports. In some circumstances ASIC may

relieve a large private company from the requirement to appoint an auditor.

Trustee Companies: (page 98-99)

• The development of Equity Law in the 16th century saw the creation of the Law

of Trusts for charitable institutions.

• The concept of a trust has expanded and is widely used in modern business and

corporations.

• In a trust, a trustee is appointed to hold and manage property on behalf of

beneficiaries.

• A trustee can be liable for shortfalls in the trust funds.

• As companies are considered a separate legal entity they can act as a trustee of a

managed fund. Companies are used because of their limited liability, tax benefits

and perpetual succession.

The company constitution and replaceable rules

• Initially an Australian company had to submit a written constitution when

applying for registration. In order to achieve greater uniformity and improvements

in standards of governance the Corporations Act now defines a set of default

internal governance rules s 134. These rules are called ‘replaceable rules’ and are

set out in s 141 of the act.

• These rules make the requirement for a constitution for new companies obsolete.

Some are mandatory, some only apply to public companies and some only apply

to private companies. Most rules however can be replaced thereby allowing a

company to develop its own constitution based on the default rules s 135.

• If a company no longer wishes to follow its own rules it needs to follow the

appropriate process to change them. A special resolution must be passed to alter

the rules in the constitution. S9 defines a ‘special resolution’ as one which is

passed by at least 75% of the votes of members entitled to cast a vote.

Additionally, any changes made to their rules or constitution should be ‘fair’.

• The company constitution (pp. 108-110)

Prior July 1998- all companies were required to have a constitution consisting of two

documents: the memorandum of association and the articles of association.

Companies formed after July 1998 have a choice regarding the rules governing their

internal administration. Under s 134 those rules may comprise a constitution specially

drafted to suit a company’s particular needs, or the replaceable rules in the

Corporations Act or a combination of both. Post 1998 consists of one document.

Companies may adopt a constitution in any of the following three ways:

1. A new company may adopt a constitution on registration if the persons named in

the application for the company’s registration as having consented to become

members, agree in writing to the terms of the constitution before the application is

lodged

2. A company that is registered without a constitution may adopt one by passing a

special resolution

3. A court order is made under s 233 that requires the company to adopt a

constitution.

Public companies that have a constitution are required to lodge a copy with ASIC.

Contents of constitution:

There are no mandatory content requirements for constitutions.

The constitution is a contract between:

• The company and each member

• The company and each director

• The company and the company secretary, and

• A member and each other member.

A company can adopt a constitution before or after registration. If it is adopted before

registration, each member must agree (in writing) to the terms of the constitution. If a

• Initially an Australian company had to submit a written constitution when

applying for registration. In order to achieve greater uniformity and improvements

in standards of governance the Corporations Act now defines a set of default

internal governance rules s 134. These rules are called ‘replaceable rules’ and are

set out in s 141 of the act.

• These rules make the requirement for a constitution for new companies obsolete.

Some are mandatory, some only apply to public companies and some only apply

to private companies. Most rules however can be replaced thereby allowing a

company to develop its own constitution based on the default rules s 135.

• If a company no longer wishes to follow its own rules it needs to follow the

appropriate process to change them. A special resolution must be passed to alter

the rules in the constitution. S9 defines a ‘special resolution’ as one which is

passed by at least 75% of the votes of members entitled to cast a vote.

Additionally, any changes made to their rules or constitution should be ‘fair’.

• The company constitution (pp. 108-110)

Prior July 1998- all companies were required to have a constitution consisting of two

documents: the memorandum of association and the articles of association.

Companies formed after July 1998 have a choice regarding the rules governing their

internal administration. Under s 134 those rules may comprise a constitution specially

drafted to suit a company’s particular needs, or the replaceable rules in the

Corporations Act or a combination of both. Post 1998 consists of one document.

Companies may adopt a constitution in any of the following three ways:

1. A new company may adopt a constitution on registration if the persons named in

the application for the company’s registration as having consented to become

members, agree in writing to the terms of the constitution before the application is

lodged

2. A company that is registered without a constitution may adopt one by passing a

special resolution

3. A court order is made under s 233 that requires the company to adopt a

constitution.

Public companies that have a constitution are required to lodge a copy with ASIC.

Contents of constitution:

There are no mandatory content requirements for constitutions.

The constitution is a contract between:

• The company and each member

• The company and each director

• The company and the company secretary, and

• A member and each other member.

A company can adopt a constitution before or after registration. If it is adopted before

registration, each member must agree (in writing) to the terms of the constitution. If a

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

constitution is adopted after registration, the company must pass a special resolution

to adopt the constitution.

The following companies must be governed by a constitution:

• 'No Liability' public companies

• 'special purpose companies' that want a reduced annual review fee.

A private company (that is a special purpose company) must have a constitution. It

doesn’t need to be lodged with us, but a copy must be kept with the company's

records.

A company must provide a current copy of the constitution to any member who

requests it within seven days. If a fee is charged, the constitution must be provided

within seven days of payment.

Section 112 requires the constitution of a no liability company to state that its sole

objects are mining purposes and that the company has no contractual right to recover

calls made on its shares from a shareholder who fails to pay them.

Replaceable rules (pp. 105-108)

• Replaceable rules are in the Corporations Act and are a basic guide

for managing your company. If you're a private company, they can be an easy

way to manage your company's governance.

• Replaceable rules do not apply to a private company if the same person is

the sole director as well as the sole shareholder.

• Most companies can choose to use the rules to guide their internal governance.

However, a company with a single member and single director who is the

same person cannot use the rules. Of course, not all companies do choose to

use them. They may wish to draft a constitution.

• However, in these instances, the rules can guide the drafting because they

describe the kinds of rules and provide the essential standards that any

constitution needs.

• While the rules are available to all companies, typically proprietary companies

choose to use them. Public companies are larger entities with the resources

required to both draft a constitution and keep it current.

• The greatest advantage of the rules is that a company who uses them is always

up to date with developments and changes in regulation. If the government

amends the rules, their organisation is automatically on top of, and can

implement these developments. That saves the time and expense of modifying

a constitution. As smaller businesses have fewer resources than larger ones,

this is particularly beneficial.

• The rules are also popular for small companies in the setting up phase because

they are a relatively inexpensive means of acquiring rules for internal

governance. Of course, they likely need a lawyer to explain the rules to them.

Nonetheless, they do not have to pay for a precisely drafted constitution.

• Alteration of the constitution and replaceable rules (pp. 119-123)

• A company can change or repeal its constitution by passing a special

resolution. A special resolution needs at least 28 days notice for publicly listed

to adopt the constitution.

The following companies must be governed by a constitution:

• 'No Liability' public companies

• 'special purpose companies' that want a reduced annual review fee.

A private company (that is a special purpose company) must have a constitution. It

doesn’t need to be lodged with us, but a copy must be kept with the company's

records.

A company must provide a current copy of the constitution to any member who

requests it within seven days. If a fee is charged, the constitution must be provided

within seven days of payment.

Section 112 requires the constitution of a no liability company to state that its sole

objects are mining purposes and that the company has no contractual right to recover

calls made on its shares from a shareholder who fails to pay them.

Replaceable rules (pp. 105-108)

• Replaceable rules are in the Corporations Act and are a basic guide

for managing your company. If you're a private company, they can be an easy

way to manage your company's governance.

• Replaceable rules do not apply to a private company if the same person is

the sole director as well as the sole shareholder.

• Most companies can choose to use the rules to guide their internal governance.

However, a company with a single member and single director who is the

same person cannot use the rules. Of course, not all companies do choose to

use them. They may wish to draft a constitution.

• However, in these instances, the rules can guide the drafting because they

describe the kinds of rules and provide the essential standards that any

constitution needs.

• While the rules are available to all companies, typically proprietary companies

choose to use them. Public companies are larger entities with the resources

required to both draft a constitution and keep it current.

• The greatest advantage of the rules is that a company who uses them is always

up to date with developments and changes in regulation. If the government

amends the rules, their organisation is automatically on top of, and can

implement these developments. That saves the time and expense of modifying

a constitution. As smaller businesses have fewer resources than larger ones,

this is particularly beneficial.

• The rules are also popular for small companies in the setting up phase because

they are a relatively inexpensive means of acquiring rules for internal

governance. Of course, they likely need a lawyer to explain the rules to them.

Nonetheless, they do not have to pay for a precisely drafted constitution.

• Alteration of the constitution and replaceable rules (pp. 119-123)

• A company can change or repeal its constitution by passing a special

resolution. A special resolution needs at least 28 days notice for publicly listed

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

companies and 21 days notice for other company types. For the resolution to

pass, at least 75% of the votes cast must be in favour.

• Section 136(3) recognises that a company’s constitution may contain

provisions that restrict the company’s ability to modify or repeal its

constitution by imposing further requirements for such alterations over and

above a special resolution. E.g. greater majority than 75%, and obtaining the

consent of a particular person.

WEEK 3:

1. Understand the concept of the “directing mind and will” of a company.

2. Be familiar with Turquand’s case and the ‘indoor management’ rule to protect

outsiders.

3. Be familiar with the statutory assumptions presented in sec 128 and 129.4.

Understand the powers of directors to bind the company in contracts with

outsiders.

4. Be familiar with:

• Direct Authority

• Implied Authority

• Customary Authority

• Apparent authority

The Directing mind and will of a company. (129-131)

• A company can enter into contracts and property dealings as if it were a real

person s124. However the separate legal entity of a company is a legal fiction

and it needs a board of directors to manage its affairs, a constitution and rules

by which to operate and agents to carry out its relations with outsiders. This

creates problems for those who make agreements with the company.

• A company does not have a guilty mind and cannot be put in prison, therefore

the law has developed ways in which those who manage the company can be

held liable as the ‘directing mind and will of the company’.

Who is the directing mind and will? (pp. 131-135)

• A company may be likened to a human being. It has a brain that controls what

it does. It also has hands that act in accordance with directions from the centre.

• The directing mind of the company could be considered to be various people.

It could be considered to be the director or directors/ senior management or in

some cases the company secretary.

• Ascertaining who is the directing mind and will of a large corporation is

generally more difficult than in the case of a company with few directors and

shareholders. In large corporations, control of he company’s business is

typically delegated to a large number of executive and managers in the

organisational hierarchy. The actions and intentions of senior management are

pass, at least 75% of the votes cast must be in favour.

• Section 136(3) recognises that a company’s constitution may contain

provisions that restrict the company’s ability to modify or repeal its

constitution by imposing further requirements for such alterations over and

above a special resolution. E.g. greater majority than 75%, and obtaining the

consent of a particular person.

WEEK 3:

1. Understand the concept of the “directing mind and will” of a company.

2. Be familiar with Turquand’s case and the ‘indoor management’ rule to protect

outsiders.

3. Be familiar with the statutory assumptions presented in sec 128 and 129.4.

Understand the powers of directors to bind the company in contracts with

outsiders.

4. Be familiar with:

• Direct Authority

• Implied Authority

• Customary Authority

• Apparent authority

The Directing mind and will of a company. (129-131)

• A company can enter into contracts and property dealings as if it were a real

person s124. However the separate legal entity of a company is a legal fiction

and it needs a board of directors to manage its affairs, a constitution and rules

by which to operate and agents to carry out its relations with outsiders. This

creates problems for those who make agreements with the company.

• A company does not have a guilty mind and cannot be put in prison, therefore

the law has developed ways in which those who manage the company can be

held liable as the ‘directing mind and will of the company’.

Who is the directing mind and will? (pp. 131-135)

• A company may be likened to a human being. It has a brain that controls what

it does. It also has hands that act in accordance with directions from the centre.

• The directing mind of the company could be considered to be various people.

It could be considered to be the director or directors/ senior management or in

some cases the company secretary.

• Ascertaining who is the directing mind and will of a large corporation is

generally more difficult than in the case of a company with few directors and

shareholders. In large corporations, control of he company’s business is

typically delegated to a large number of executive and managers in the

organisational hierarchy. The actions and intentions of senior management are

relevant to determining the state of mind of a corporation and more than one

person may be regarded as its directing mind and will.

How does a company undertake relations with outsiders?

• Historically, a company’s objects clause was the most important part of its

‘Memorandum of Association’ in its constitution. It set out the nature and

scope of the company’s business objectives. If a company officer or agent

entered into a contract or property transaction that was outside the scope of its

objects clause then the company could argue that the transaction was not

binding. It could claim that the transaction was outside the powers set out in

the constitution and therefore ultra vires or out of power.

• This biased any transaction with outsiders in the company's favour.

Companies could easily get out of contracts with outside businesses by

arguing that there was no proper authority.

Indoor management rule

Persons dealing with a company in good faith should be able to assume that acts

within its constitution and powers have been properly and duly performed and should

not be bound to inquire whether acts of internal management have been validly

executed. This is given legal force through the indoor management rule.

▪ It is a rule designed for the protection of those who are entitled to assume,

just because they cannot know, that the person with whom they deal has

the authority which he claims

▪ Not applicable when:

▪ Person is aware of irregularities

▪ Persons 'put on inquiry' - ie, if there was something to make a reasonable

person in the position of the person suspicious about a possible regularity,

and investigate the matter further.

▪ The rule cannot benefit the company.

S 128 and 129 are the statutory equivalent with the indoor management rule.

Originally, the rule was not recognised. Cases such as Ernest v Nicholls said the

opposite:

▪ All persons must take notice of the deed and the provisions of the Act - if

they do not chose to acquaint themselves with the powers of the directors,

it is their own fault and if the give credit to an unauthorised person they

must be contended to look to them only, and not to the company at large.

The rule became more recognised in Royal British Bank v Turquand:[6]

▪ Facts: RBB lent money to T (company) on security of bond signed by two

directors and bearing company seal. Company’s deed of settlement

authorised directors to grant bonds only when authorised by resolution of

general meeting of company. Company pleaded that there had been no

such resolution, so the transaction should be voided.

▪ Held (Jervis CJ): parties dealing with companies are bound to read the

statute and the deed of settlement, but are bound to do nothing more.

person may be regarded as its directing mind and will.

How does a company undertake relations with outsiders?

• Historically, a company’s objects clause was the most important part of its

‘Memorandum of Association’ in its constitution. It set out the nature and

scope of the company’s business objectives. If a company officer or agent

entered into a contract or property transaction that was outside the scope of its

objects clause then the company could argue that the transaction was not

binding. It could claim that the transaction was outside the powers set out in

the constitution and therefore ultra vires or out of power.

• This biased any transaction with outsiders in the company's favour.

Companies could easily get out of contracts with outside businesses by

arguing that there was no proper authority.

Indoor management rule

Persons dealing with a company in good faith should be able to assume that acts

within its constitution and powers have been properly and duly performed and should

not be bound to inquire whether acts of internal management have been validly

executed. This is given legal force through the indoor management rule.

▪ It is a rule designed for the protection of those who are entitled to assume,

just because they cannot know, that the person with whom they deal has

the authority which he claims

▪ Not applicable when:

▪ Person is aware of irregularities

▪ Persons 'put on inquiry' - ie, if there was something to make a reasonable

person in the position of the person suspicious about a possible regularity,

and investigate the matter further.

▪ The rule cannot benefit the company.

S 128 and 129 are the statutory equivalent with the indoor management rule.

Originally, the rule was not recognised. Cases such as Ernest v Nicholls said the

opposite:

▪ All persons must take notice of the deed and the provisions of the Act - if

they do not chose to acquaint themselves with the powers of the directors,

it is their own fault and if the give credit to an unauthorised person they

must be contended to look to them only, and not to the company at large.

The rule became more recognised in Royal British Bank v Turquand:[6]

▪ Facts: RBB lent money to T (company) on security of bond signed by two

directors and bearing company seal. Company’s deed of settlement

authorised directors to grant bonds only when authorised by resolution of

general meeting of company. Company pleaded that there had been no

such resolution, so the transaction should be voided.

▪ Held (Jervis CJ): parties dealing with companies are bound to read the

statute and the deed of settlement, but are bound to do nothing more.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Finding that authority might be made complete by resolution, he would

have right to infer fact of such as resolution authorising that which on face

of document appeared to be legitimately done - people dealing with a

company have constructive notice of requirements of its memorandum and

articles of association but are not to be affected by irregularities which

take place in internal management of company.

▪ Note: constructive notice is now abolished in relation to company

documents: s 130, 129(1)

Who has the authority to act on behalf of a company?

Companies may directly enter into contracts:

• By use of the company seal s123(1), where two directors or one director and

the company secretary fix the seal, and witness the fixing of the seal.

• Since 1998 the use of a seal has been made optional. Companies may now

enter into a contract using the same procedure as above, but by just a signing

the document rather than fixing the company seal, see s127(1)

But who has the authority to enter into a contract with an outsider?

• A company may give express actual authority to a particular person.

• To do this the board of directors would need to pass a resolution in an

appropriate form. Particular company officers may also enter into a contract

with an outsider using implied authority (based on their role in the business).

People who have implied authority are outlined in the table below.

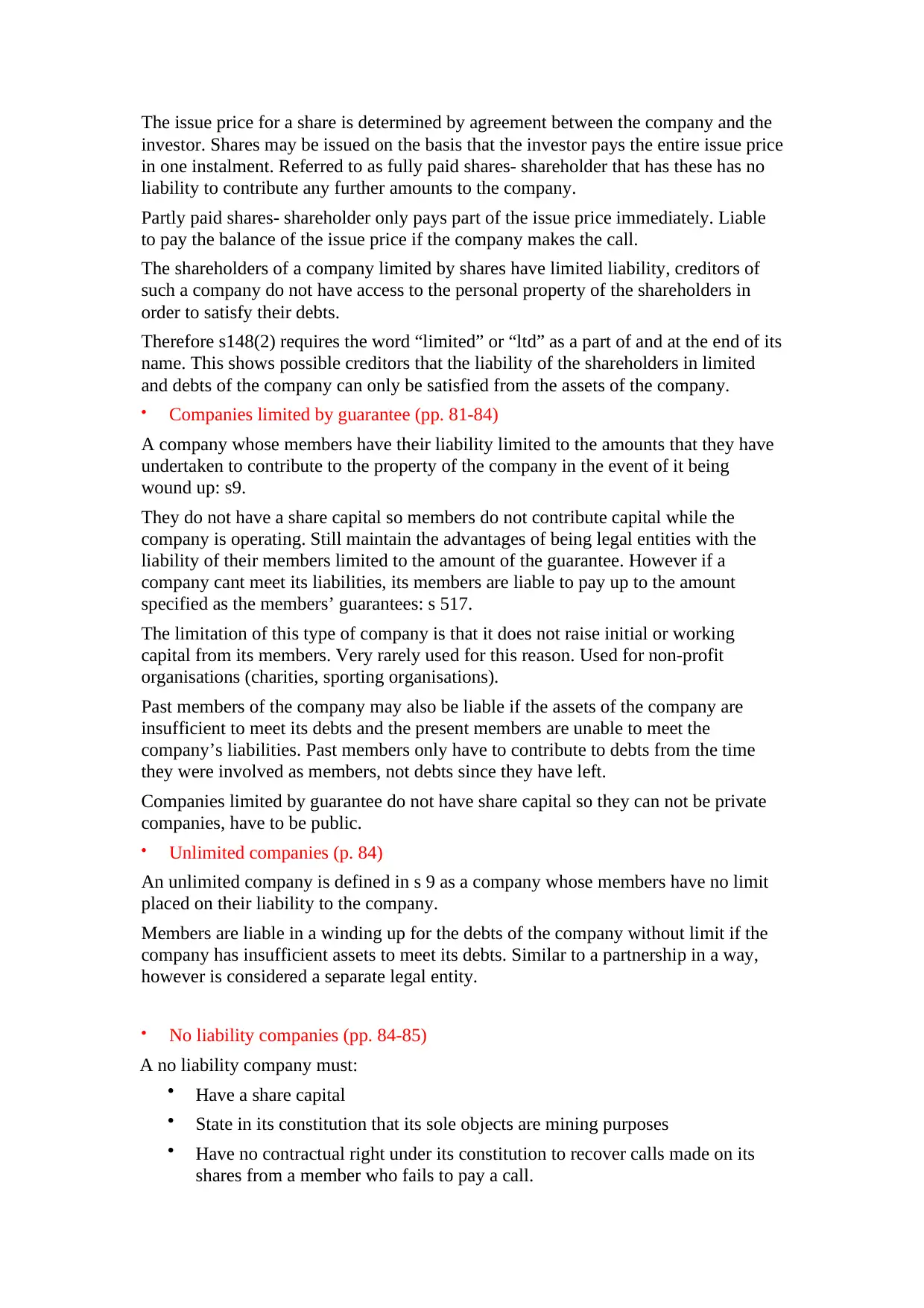

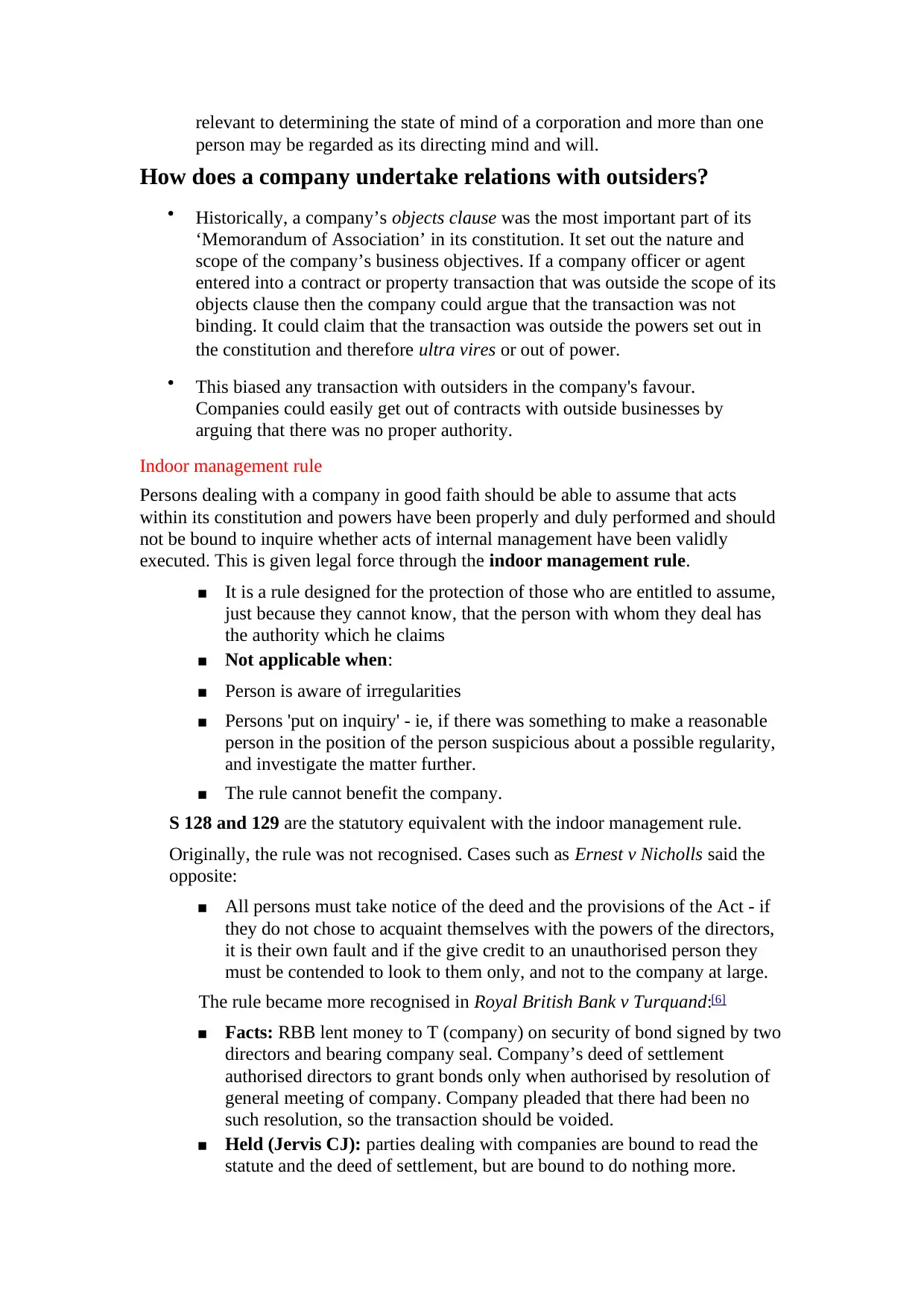

Managing Director Authority

Managing Director Have all the powers of the company

necessary to deal with the day to day

operations of the company including

delegation to others, employment of

others, the borrowing of money and the

giving of guarantees, in the ordinary

course of business.

CEO A CEO who is not on the board may still

have the same authority as a managing

director.

Individual Director (executive or non-

executive)

Has no usual authority to bind the

company unless they act collectively

with other directors as a board.

have right to infer fact of such as resolution authorising that which on face

of document appeared to be legitimately done - people dealing with a

company have constructive notice of requirements of its memorandum and

articles of association but are not to be affected by irregularities which

take place in internal management of company.

▪ Note: constructive notice is now abolished in relation to company

documents: s 130, 129(1)

Who has the authority to act on behalf of a company?

Companies may directly enter into contracts:

• By use of the company seal s123(1), where two directors or one director and

the company secretary fix the seal, and witness the fixing of the seal.

• Since 1998 the use of a seal has been made optional. Companies may now

enter into a contract using the same procedure as above, but by just a signing

the document rather than fixing the company seal, see s127(1)

But who has the authority to enter into a contract with an outsider?

• A company may give express actual authority to a particular person.

• To do this the board of directors would need to pass a resolution in an

appropriate form. Particular company officers may also enter into a contract

with an outsider using implied authority (based on their role in the business).

People who have implied authority are outlined in the table below.

Managing Director Authority

Managing Director Have all the powers of the company

necessary to deal with the day to day

operations of the company including

delegation to others, employment of

others, the borrowing of money and the

giving of guarantees, in the ordinary

course of business.

CEO A CEO who is not on the board may still

have the same authority as a managing

director.

Individual Director (executive or non-

executive)

Has no usual authority to bind the

company unless they act collectively

with other directors as a board.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

• Actual authority (p. 141; pp. 145-146)

• Specific powers, expressly conferred by a principal (often an insurance

company) to an agent to act on the principal's behalf. This power may be

broad, general power or it may be limited, special power.

• An agent receives actual authority either orally or in writing. Written authority

is preferable, as it is somewhat difficult to establish authority that is given

verbally. In a corporation, written express authority includes bylaws and

resolutions from directors' meetings which grant the authorized person

permission to carry out a definite act on behalf of the corporation.

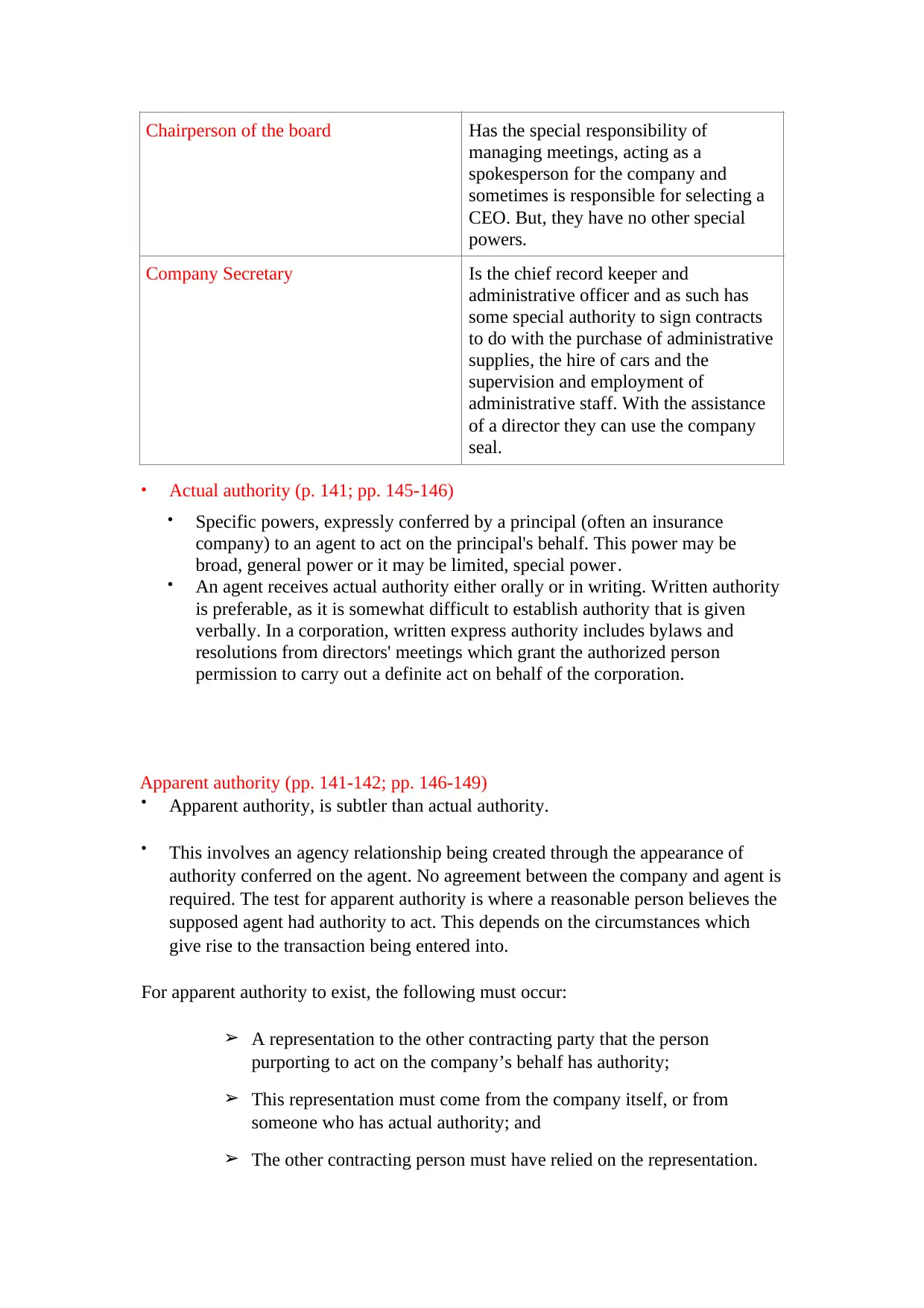

Apparent authority (pp. 141-142; pp. 146-149)

• Apparent authority, is subtler than actual authority.

• This involves an agency relationship being created through the appearance of

authority conferred on the agent. No agreement between the company and agent is

required. The test for apparent authority is where a reasonable person believes the

supposed agent had authority to act. This depends on the circumstances which

give rise to the transaction being entered into.

For apparent authority to exist, the following must occur:

➢ A representation to the other contracting party that the person

purporting to act on the company’s behalf has authority;

➢ This representation must come from the company itself, or from

someone who has actual authority; and

➢ The other contracting person must have relied on the representation.

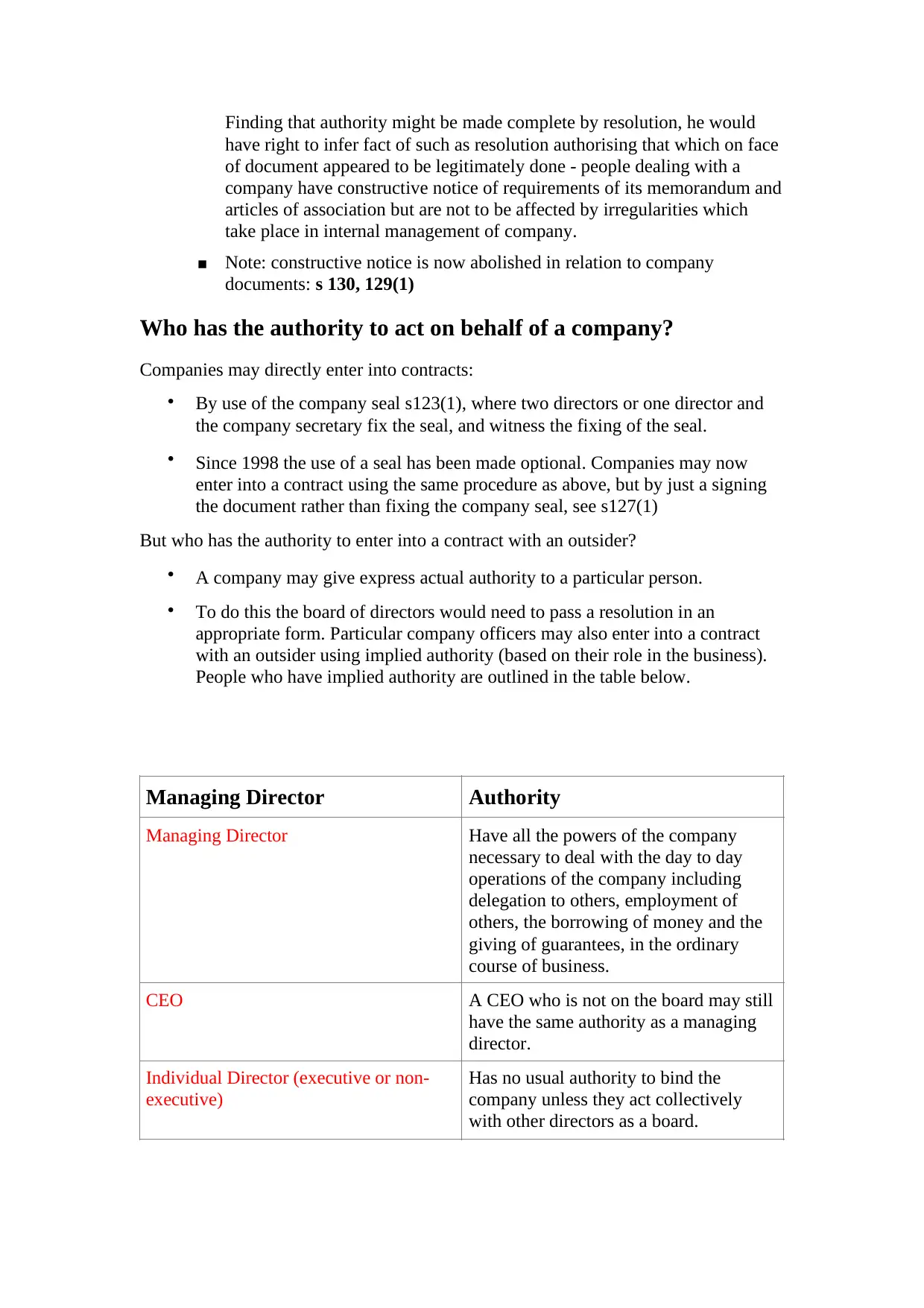

Chairperson of the board Has the special responsibility of

managing meetings, acting as a

spokesperson for the company and

sometimes is responsible for selecting a

CEO. But, they have no other special

powers.

Company Secretary Is the chief record keeper and

administrative officer and as such has

some special authority to sign contracts

to do with the purchase of administrative

supplies, the hire of cars and the

supervision and employment of

administrative staff. With the assistance

of a director they can use the company

seal.

• Specific powers, expressly conferred by a principal (often an insurance

company) to an agent to act on the principal's behalf. This power may be

broad, general power or it may be limited, special power.

• An agent receives actual authority either orally or in writing. Written authority

is preferable, as it is somewhat difficult to establish authority that is given

verbally. In a corporation, written express authority includes bylaws and

resolutions from directors' meetings which grant the authorized person

permission to carry out a definite act on behalf of the corporation.

Apparent authority (pp. 141-142; pp. 146-149)

• Apparent authority, is subtler than actual authority.

• This involves an agency relationship being created through the appearance of

authority conferred on the agent. No agreement between the company and agent is

required. The test for apparent authority is where a reasonable person believes the

supposed agent had authority to act. This depends on the circumstances which

give rise to the transaction being entered into.

For apparent authority to exist, the following must occur:

➢ A representation to the other contracting party that the person

purporting to act on the company’s behalf has authority;

➢ This representation must come from the company itself, or from

someone who has actual authority; and

➢ The other contracting person must have relied on the representation.

Chairperson of the board Has the special responsibility of

managing meetings, acting as a

spokesperson for the company and

sometimes is responsible for selecting a

CEO. But, they have no other special

powers.

Company Secretary Is the chief record keeper and

administrative officer and as such has

some special authority to sign contracts

to do with the purchase of administrative

supplies, the hire of cars and the

supervision and employment of

administrative staff. With the assistance

of a director they can use the company

seal.

• For companies involved in heavy contracting, such as the fuel industry,

apparent authority is an important risk that needs to be controlled.

• Companies are advised to continually review who is listed in documents,

websites and the like as having authority to enter into contracts to ensure that

outside parties are not misinformed. While this takes vigilance, the alternative

is binding!

Customary authority (pp. 158-160)

Individual directors:

• Witness the fixing of the company’s common seal (s127(2))

• Sign the company’s negotiable instruments, including cheques: s 198B

• Does not have customary authority to make contracts on the company’s

behalf.

Managing Director:

• Has the customary authority to make any contracts related to the day-to-day

management of the company’s business. This includes engaging persons to do

work for the company.

• Cannot enter a purported sale of the entire business of the company.

The chair:

• The chair has the same customary authority as any other individual director

and consequently does not have the customary authority to contract on the

company’s behalf.

Secretary:

• The customary authority of a company secretary is not as wide as that of a

director. The role is limited to matters of an administrative, internal nature

required for day-to-day running of the company’s affairs such as employing

staff, and ordering cars.

• Does not include authority to mortgage the company’s land.

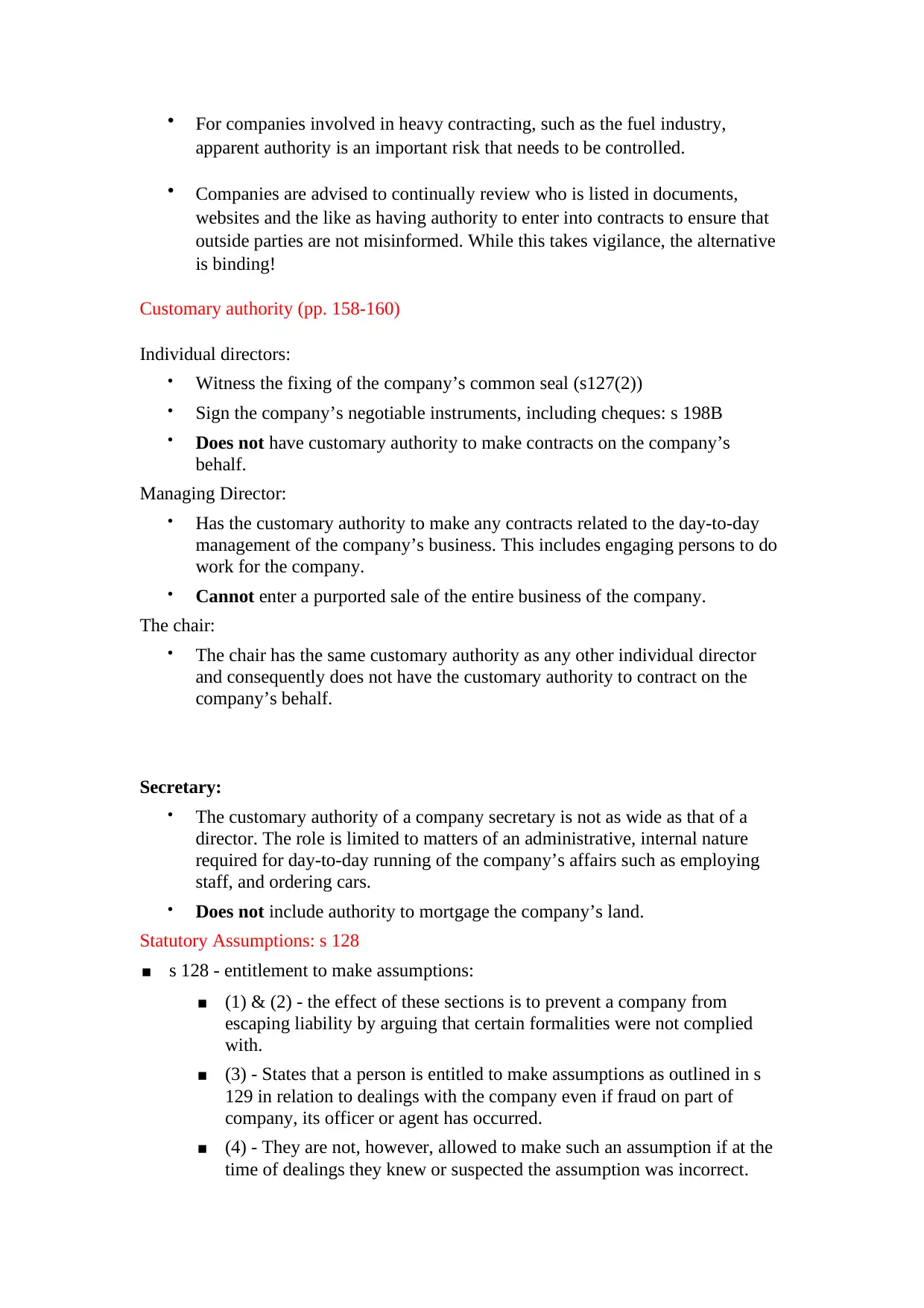

Statutory Assumptions: s 128

▪ s 128 - entitlement to make assumptions:

▪ (1) & (2) - the effect of these sections is to prevent a company from

escaping liability by arguing that certain formalities were not complied

with.

▪ (3) - States that a person is entitled to make assumptions as outlined in s

129 in relation to dealings with the company even if fraud on part of

company, its officer or agent has occurred.

▪ (4) - They are not, however, allowed to make such an assumption if at the

time of dealings they knew or suspected the assumption was incorrect.

apparent authority is an important risk that needs to be controlled.

• Companies are advised to continually review who is listed in documents,

websites and the like as having authority to enter into contracts to ensure that

outside parties are not misinformed. While this takes vigilance, the alternative

is binding!

Customary authority (pp. 158-160)

Individual directors:

• Witness the fixing of the company’s common seal (s127(2))

• Sign the company’s negotiable instruments, including cheques: s 198B

• Does not have customary authority to make contracts on the company’s

behalf.

Managing Director:

• Has the customary authority to make any contracts related to the day-to-day

management of the company’s business. This includes engaging persons to do

work for the company.

• Cannot enter a purported sale of the entire business of the company.

The chair:

• The chair has the same customary authority as any other individual director

and consequently does not have the customary authority to contract on the

company’s behalf.

Secretary:

• The customary authority of a company secretary is not as wide as that of a

director. The role is limited to matters of an administrative, internal nature

required for day-to-day running of the company’s affairs such as employing

staff, and ordering cars.

• Does not include authority to mortgage the company’s land.

Statutory Assumptions: s 128

▪ s 128 - entitlement to make assumptions:

▪ (1) & (2) - the effect of these sections is to prevent a company from

escaping liability by arguing that certain formalities were not complied

with.

▪ (3) - States that a person is entitled to make assumptions as outlined in s

129 in relation to dealings with the company even if fraud on part of

company, its officer or agent has occurred.

▪ (4) - They are not, however, allowed to make such an assumption if at the

time of dealings they knew or suspected the assumption was incorrect.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 64

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.