Comparative Analysis of Vaccine Mandates in US, Europe, and Australia

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|8

|9373

|13

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a comparative analysis of recent vaccine mandates implemented in the United States, Europe, and Australia. It examines the diverse forms these mandates take, including their structure, exemptions, target populations, consequences, and enforcement mechanisms. The study compares policies in California, Italy, France, Germany, Australia, and Washington, ranking them by restrictiveness and highlighting differences in their approach. The analysis considers the political and cultural contexts influencing policy decisions, emphasizing the importance of public trust and historical precedent. The report also discusses the mechanisms by which vaccine mandates are constructed and implemented, including the involvement of stakeholder groups. The report identifies key considerations for policymakers when implementing or reforming vaccine mandates, including the need to address both access and acceptance issues related to vaccination and provides insights into the effectiveness of different policy approaches in increasing immunization coverage and addressing vaccine hesitancy. The report also highlights unintended consequences and enforcement challenges associated with different mandate policies.

Recent vaccine mandates in the United States,Europe and Australia:

A comparative study

Katie Attwella,⇑

, Mark C. Navin b, Pier Luigi Lopalcoc, Christine Jestind, Sabine Reitere, Saad B.Omerf

a Political Science and International Relations,University of Western Australia,35 Stirling Highway,Crawley 6009,Australia

b Department of Philosophy,Oakland University,146 Library Drive,Rochester,MI 48309-4479,USA

c Department of Translational Research on New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery,University of Pisa,Lungarno Antonio Pacinotti,43, 56126 Pisa Pl,Italy

d Sante Publique France,12 rue du Val d’Osne,94415 Saint-Maurice Cedex,France

e Infectious Diseases,Antimicrobial Resistance,Hygiene,Vaccination Federal Ministry of Health,Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Referat,322 Friedrichstraße 108,10117

Berlin,Germany

f Rollins School of Public Health,Emory University,1518 Clifton Road NE,Atlanta,GA 20211,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 18 June 2018

Received in revised form 3 October 2018

Accepted 4 October 2018

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Vaccination

Immunization

Mandatory

Mandates

Policy

a b s t r a c t

Background:In response to recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and concerns around vac-

cine refusal,several high-income countries have adopted or reformed vaccine mandate policies.While

all make it more difficult for parents to refuse vaccines, the nature and scope of ‘mandatory vaccination’

is heterogeneous,and there has been no attempt to develop a detailed,comparative systematic account

of the possible forms mandates can take.

Methods:We compare the construction, introduction/amendment, and operation of six new high profile

vaccine mandates in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, California, and Washington. We rank these policie

in order of their relative restrictiveness and analyze other differences between them.

Results:New mandate instruments differ in their effects on behavior, and with regard to their structure,

exemptions,target populations,consequences and enforcement.We identify diverse means by which

vaccine mandates can restrict behaviors, various degrees of severity, and different gradations of intensit

in enforcement.

Conclusion:We suggest that politico-cultural context and vaccine policy history are centrally important

factors for vaccine mandate policymakers to consider.It matters whether citizens trust their govern-

ments to limit individual freedom in the name of public health,and whether citizens have previously

been subjected to vaccine mandates.Furthermore,political communities mustconsider the diverse

mechanisms by which they may construct vaccine mandate policies;whether through emergency

decrees or ordinary statutes,and how (or whether) to involve various stakeholder groups in developing

and implementing new vaccine mandate policies.

Ó 2018 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases have recently

occurred in many countries,e.g.measles in France,mumps in Ire-

land, and pertussis in the US. Several governments have responded

by introducing or strengthening vaccine mandates; other jurisdic-

tions are considering similar policies.Mandate instruments are

heterogeneous in how they operate to organise and change behav-

ior, with regard to structure,exemptions,target populations,con-

sequences and enforcement. Yet the nature and scope of

‘mandatory vaccination’is indeterminate,and there has not yet

been a systematic comparative synthesis of mandate policy devel-

opment, implementation and structure.Debates about vaccine

mandates ought to be informed by accurate accounts of the diverse

aims and requirements that vaccine mandate policies involve.In

this article, we compare new vaccine mandate policies adopted

in four countries and two US states in the last two years. We have

chosen our case studies as high profile exemplars of policy changes

in response to vaccine rejection and/or disease outbreaks; policy-

makers within these jurisdictions reference each other’s policies

as trends or templates [1]. We outline these new mandatory

policies in order of their relative restrictiveness, based on how dif-

ficult they make it for parents to refuse vaccines for their children.

Our comparison yields clear lessons for jurisdictions considering

implementing or reforming vaccine mandates,including a need

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

0264-410X/Ó 2018 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

⇑ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Katie.attwell@uwa.edu.au (K.Attwell).

Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / v a c c i n e

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

A comparative study

Katie Attwella,⇑

, Mark C. Navin b, Pier Luigi Lopalcoc, Christine Jestind, Sabine Reitere, Saad B.Omerf

a Political Science and International Relations,University of Western Australia,35 Stirling Highway,Crawley 6009,Australia

b Department of Philosophy,Oakland University,146 Library Drive,Rochester,MI 48309-4479,USA

c Department of Translational Research on New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery,University of Pisa,Lungarno Antonio Pacinotti,43, 56126 Pisa Pl,Italy

d Sante Publique France,12 rue du Val d’Osne,94415 Saint-Maurice Cedex,France

e Infectious Diseases,Antimicrobial Resistance,Hygiene,Vaccination Federal Ministry of Health,Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Referat,322 Friedrichstraße 108,10117

Berlin,Germany

f Rollins School of Public Health,Emory University,1518 Clifton Road NE,Atlanta,GA 20211,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 18 June 2018

Received in revised form 3 October 2018

Accepted 4 October 2018

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Vaccination

Immunization

Mandatory

Mandates

Policy

a b s t r a c t

Background:In response to recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and concerns around vac-

cine refusal,several high-income countries have adopted or reformed vaccine mandate policies.While

all make it more difficult for parents to refuse vaccines, the nature and scope of ‘mandatory vaccination’

is heterogeneous,and there has been no attempt to develop a detailed,comparative systematic account

of the possible forms mandates can take.

Methods:We compare the construction, introduction/amendment, and operation of six new high profile

vaccine mandates in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, California, and Washington. We rank these policie

in order of their relative restrictiveness and analyze other differences between them.

Results:New mandate instruments differ in their effects on behavior, and with regard to their structure,

exemptions,target populations,consequences and enforcement.We identify diverse means by which

vaccine mandates can restrict behaviors, various degrees of severity, and different gradations of intensit

in enforcement.

Conclusion:We suggest that politico-cultural context and vaccine policy history are centrally important

factors for vaccine mandate policymakers to consider.It matters whether citizens trust their govern-

ments to limit individual freedom in the name of public health,and whether citizens have previously

been subjected to vaccine mandates.Furthermore,political communities mustconsider the diverse

mechanisms by which they may construct vaccine mandate policies;whether through emergency

decrees or ordinary statutes,and how (or whether) to involve various stakeholder groups in developing

and implementing new vaccine mandate policies.

Ó 2018 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases have recently

occurred in many countries,e.g.measles in France,mumps in Ire-

land, and pertussis in the US. Several governments have responded

by introducing or strengthening vaccine mandates; other jurisdic-

tions are considering similar policies.Mandate instruments are

heterogeneous in how they operate to organise and change behav-

ior, with regard to structure,exemptions,target populations,con-

sequences and enforcement. Yet the nature and scope of

‘mandatory vaccination’is indeterminate,and there has not yet

been a systematic comparative synthesis of mandate policy devel-

opment, implementation and structure.Debates about vaccine

mandates ought to be informed by accurate accounts of the diverse

aims and requirements that vaccine mandate policies involve.In

this article, we compare new vaccine mandate policies adopted

in four countries and two US states in the last two years. We have

chosen our case studies as high profile exemplars of policy changes

in response to vaccine rejection and/or disease outbreaks; policy-

makers within these jurisdictions reference each other’s policies

as trends or templates [1]. We outline these new mandatory

policies in order of their relative restrictiveness, based on how dif-

ficult they make it for parents to refuse vaccines for their children.

Our comparison yields clear lessons for jurisdictions considering

implementing or reforming vaccine mandates,including a need

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

0264-410X/Ó 2018 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

⇑ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Katie.attwell@uwa.edu.au (K.Attwell).

Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / v a c c i n e

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

to pay attention to political and policy considerations of path

dependency.

2. Mandates come in different shapes and sizes

Courts in countries around the world have long recognized the

legitimacy of liberty-infringing public health efforts, in light of the

priority that communities place on avoiding disease [2,3].Such

efforts include vaccine mandates,which have only rarely been

overturned by courts [1]. When considering mandates, policymak-

ers must address divergentaccess and acceptance reasons that

populations may remain under-vaccinated.Access refers to the

availability, affordability and convenience of services; parental

complacency may also fit here.Acceptance,by contrast,relates to

vaccine hesitancy [4]. Parents fear ingredients, distrust authorities,

or do not regard vaccination as congruent with their parenting

practices [5]. Vaccine mandates can address acceptance by making

it harder – or more consequential – for parents to refuse vaccines.

However, mandates govern access (complacency)too, as we

explain below.

We can better understand jurisdictions’vaccine mandates by

locating them on an ideal-type continuum (Fig. 1). At one end, vac-

cination is voluntary, and state interventions merely nudge or per-

suade individuals to vaccinate.At the other end,vaccine refusers

are fined or imprisoned. Here, the state’s coercive power motivates

individuals to utilise available vaccination services.

Between these ends ofthe continuum are positively framed

requirements.The first links vaccine uptake to public goods such

as state-subsidised daycare and public schools,while the second

links uptake to financial incentives.Both function as ‘carrots’that

only the vaccinated can obtain;compliers are offered a benefit

which is denied to non-compliers.

We can then differentiate ‘carrot’ policies on the basis of

exemptions.Towards the voluntary end of the spectrum,compli-

ance means an individualattains the benefit,but non-compliers

can obtain it after performing specified actions.This overcomes

complacency,whilst constructing an exemption process for non-

compliers to follow. Towards the coercive end ofthe spectrum,

exemption processes are removed (except in the case of medical

contra-indications to vaccination).As ‘carrot’policies move along

the spectrum towards coercion, there is no change to the

governance of compliers,who might have access barriers or need

motivation.However,vaccine rejection meets consequences that

cannot be ‘worked around’with exemptions.In the next section,

we compare mandate policies in six jurisdictions that have

recently introduced or strengthened them,starting with what we

rank as the most restrictive and moving to the least restrictive poli-

cies. We note that while we use a terminology of restrictiveness,

other scholars have recently employed a terminology ofrigidity

(from hard to soft) [6].

3. Country case studies

3.1.California

All US states require children to receive vaccines to attend day-

care or school (specific vaccines for the states in this study are

listed in Table 1).Since September 23,2010,the Affordable Care

Act has required vaccines recommended by the Advisory Commit-

tee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to be covered by insurance.

The Vaccines for Children Program (a federally-funded and state-

administered program)provides free vaccines for children who

are uninsured or Medicaid eligible.Most US states permit parents

and guardians to receive nonmedical exemptions (NMEs) to immu-

nization mandates [7]. A 2010 national survey of US parents found

that 77% of parents with children aged 1–6 had a vaccine concern,

which included beliefs that vaccine ingredients may be unsafe

(26%) and that vaccines may cause learning disabilities such as aut-

ism (30%). In light of rising NME rates in California, the state legis-

lature recently passed two laws to successively restrict parents’

access to them.

Assembly Bill 2109 (in effect January 1, 2014 to January 1, 2016)

made it more difficult for parents or guardians to receive NMEs by

requiring applicants to submit an officialstate form on which a

physician attested that they provided information regarding the

benefits/risks ofimmunization [8].At the time of Assembly Bill

2109’s introduction,90.2% ofentering Kindergarteners were up-

to-date on all required vaccines.The rate of nonmedicalexemp-

tions was 3.1% [9]. Assembly Bill 2109 aimed to reduce NME rates

by targeting the complacent;parents and guardians with only

moderate objections might decide to vaccinate rather than

complete burdensome paperwork,as previous research indicated

was likely [10]. Assembly Bill 2109 was associated with a 25%

reduction in California’s NME rates (from 3.1% to 2.3%), and signif-

icant increases up-to-date status for entering Kindergarteners,

Fig. 1. The conceptual continuum of options available to policymakers for vaccine mandates.

2 K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

dependency.

2. Mandates come in different shapes and sizes

Courts in countries around the world have long recognized the

legitimacy of liberty-infringing public health efforts, in light of the

priority that communities place on avoiding disease [2,3].Such

efforts include vaccine mandates,which have only rarely been

overturned by courts [1]. When considering mandates, policymak-

ers must address divergentaccess and acceptance reasons that

populations may remain under-vaccinated.Access refers to the

availability, affordability and convenience of services; parental

complacency may also fit here.Acceptance,by contrast,relates to

vaccine hesitancy [4]. Parents fear ingredients, distrust authorities,

or do not regard vaccination as congruent with their parenting

practices [5]. Vaccine mandates can address acceptance by making

it harder – or more consequential – for parents to refuse vaccines.

However, mandates govern access (complacency)too, as we

explain below.

We can better understand jurisdictions’vaccine mandates by

locating them on an ideal-type continuum (Fig. 1). At one end, vac-

cination is voluntary, and state interventions merely nudge or per-

suade individuals to vaccinate.At the other end,vaccine refusers

are fined or imprisoned. Here, the state’s coercive power motivates

individuals to utilise available vaccination services.

Between these ends ofthe continuum are positively framed

requirements.The first links vaccine uptake to public goods such

as state-subsidised daycare and public schools,while the second

links uptake to financial incentives.Both function as ‘carrots’that

only the vaccinated can obtain;compliers are offered a benefit

which is denied to non-compliers.

We can then differentiate ‘carrot’ policies on the basis of

exemptions.Towards the voluntary end of the spectrum,compli-

ance means an individualattains the benefit,but non-compliers

can obtain it after performing specified actions.This overcomes

complacency,whilst constructing an exemption process for non-

compliers to follow. Towards the coercive end ofthe spectrum,

exemption processes are removed (except in the case of medical

contra-indications to vaccination).As ‘carrot’policies move along

the spectrum towards coercion, there is no change to the

governance of compliers,who might have access barriers or need

motivation.However,vaccine rejection meets consequences that

cannot be ‘worked around’with exemptions.In the next section,

we compare mandate policies in six jurisdictions that have

recently introduced or strengthened them,starting with what we

rank as the most restrictive and moving to the least restrictive poli-

cies. We note that while we use a terminology of restrictiveness,

other scholars have recently employed a terminology ofrigidity

(from hard to soft) [6].

3. Country case studies

3.1.California

All US states require children to receive vaccines to attend day-

care or school (specific vaccines for the states in this study are

listed in Table 1).Since September 23,2010,the Affordable Care

Act has required vaccines recommended by the Advisory Commit-

tee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to be covered by insurance.

The Vaccines for Children Program (a federally-funded and state-

administered program)provides free vaccines for children who

are uninsured or Medicaid eligible.Most US states permit parents

and guardians to receive nonmedical exemptions (NMEs) to immu-

nization mandates [7]. A 2010 national survey of US parents found

that 77% of parents with children aged 1–6 had a vaccine concern,

which included beliefs that vaccine ingredients may be unsafe

(26%) and that vaccines may cause learning disabilities such as aut-

ism (30%). In light of rising NME rates in California, the state legis-

lature recently passed two laws to successively restrict parents’

access to them.

Assembly Bill 2109 (in effect January 1, 2014 to January 1, 2016)

made it more difficult for parents or guardians to receive NMEs by

requiring applicants to submit an officialstate form on which a

physician attested that they provided information regarding the

benefits/risks ofimmunization [8].At the time of Assembly Bill

2109’s introduction,90.2% ofentering Kindergarteners were up-

to-date on all required vaccines.The rate of nonmedicalexemp-

tions was 3.1% [9]. Assembly Bill 2109 aimed to reduce NME rates

by targeting the complacent;parents and guardians with only

moderate objections might decide to vaccinate rather than

complete burdensome paperwork,as previous research indicated

was likely [10]. Assembly Bill 2109 was associated with a 25%

reduction in California’s NME rates (from 3.1% to 2.3%), and signif-

icant increases up-to-date status for entering Kindergarteners,

Fig. 1. The conceptual continuum of options available to policymakers for vaccine mandates.

2 K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

from 90.2% to 92.9% [9].However,this decline was not uniform,

and left major geographic exemptions clusters undisturbed [11].

Subsequently,Senate Bill 277 (enacted June 30,2015) elimi-

nated access to NMEs entirely in California [12].With this new

law, California joined West Virginia and Mississippias the only

US states not to provide NMEs [7]. Advocates argued that eliminat-

ing NMEs was necessary to further increase California’s immuniza-

tion coverage [13].However,it seems likely that they were also

motivated by the high-profile 2014–15 Disneyland measles out-

break [9,14],which may explain why the Bill’s authors (Richard

Pan and Ben Allen) were unwilling to wait to see the impact of

the earlier Assembly Bill 2109 on California’s NME rates (outlined

above) [9].

While there is some preliminary evidence that SB 277 has fur-

ther increased immunization coverage beyond the gains realized

by AB 2109,questions remain about enforcement and unintended

consequences.Financially vulnerable private schools may decide

not to enforce immunization requirements rather than risk school

closure due to declining tuition revenues from vaccine refusers

[15].Some physicians may support marginal or fraudulent claims

for medical exemptions, which likely explains why medical exemp-

tion rates in California have tripled since the passage of Senate Bill

277 [16].Also, Senate Bill 277 may cultivate political polarization

surrounding vaccination policy and science:most Democrats in

the California Senate voted for it,while most Republicans voted

against it,reversing a history of bipartisan vaccination policies in

the US [17].

3.2.Italy

Italy has a history of mandates for some vaccines for older chil-

dren, including diphtheria (1939), polio (1966), tetanus (1968), and

hepatitis B (1991). Mandated vaccines were offered at no cost, and

statutes authorized fines and school exclusion for children who did

not receive them.Persistent parents,however,could receive per-

mission for non-compliant children to enrol in school, after parents

attended meetings with public health officers or the Minors Court.

Fines were rarely applied. A suite of additional ‘recommended’ vac-

cines were also offered for free,notably MMR and pertussis.

Policy shifts occurred from 1999 onwards,with a Ministry of

Education decree that children who had not received mandatory

vaccinations should still be allowed to attend school. This was

based on Italy’s constitution, in which a right to education is equal

to the right to health. From here, mandates remained ‘on the

books’,but not enforced.

In 2007, the Veneto region piloted a mandate suspension,

reflecting popular opinion that the state ought to affirm the impor-

tance of vaccination,but not mandate it [18].However,in 2013,a

local court in Rimini ruled that vaccines caused a child’s autism,

which prompted significant media coverage and internet search

activity [19]. The subsequent2015 overturning of the case did

not receive the same media coverage [20].Starting from 2013,

nation-wide vaccination coverage dropped significantly (Fig.2).

In 2016 a cross-sectional survey showed that 15.6% of Italian par-

ents were vaccine hesitant and 0.7% strongly vaccine opposed [21].

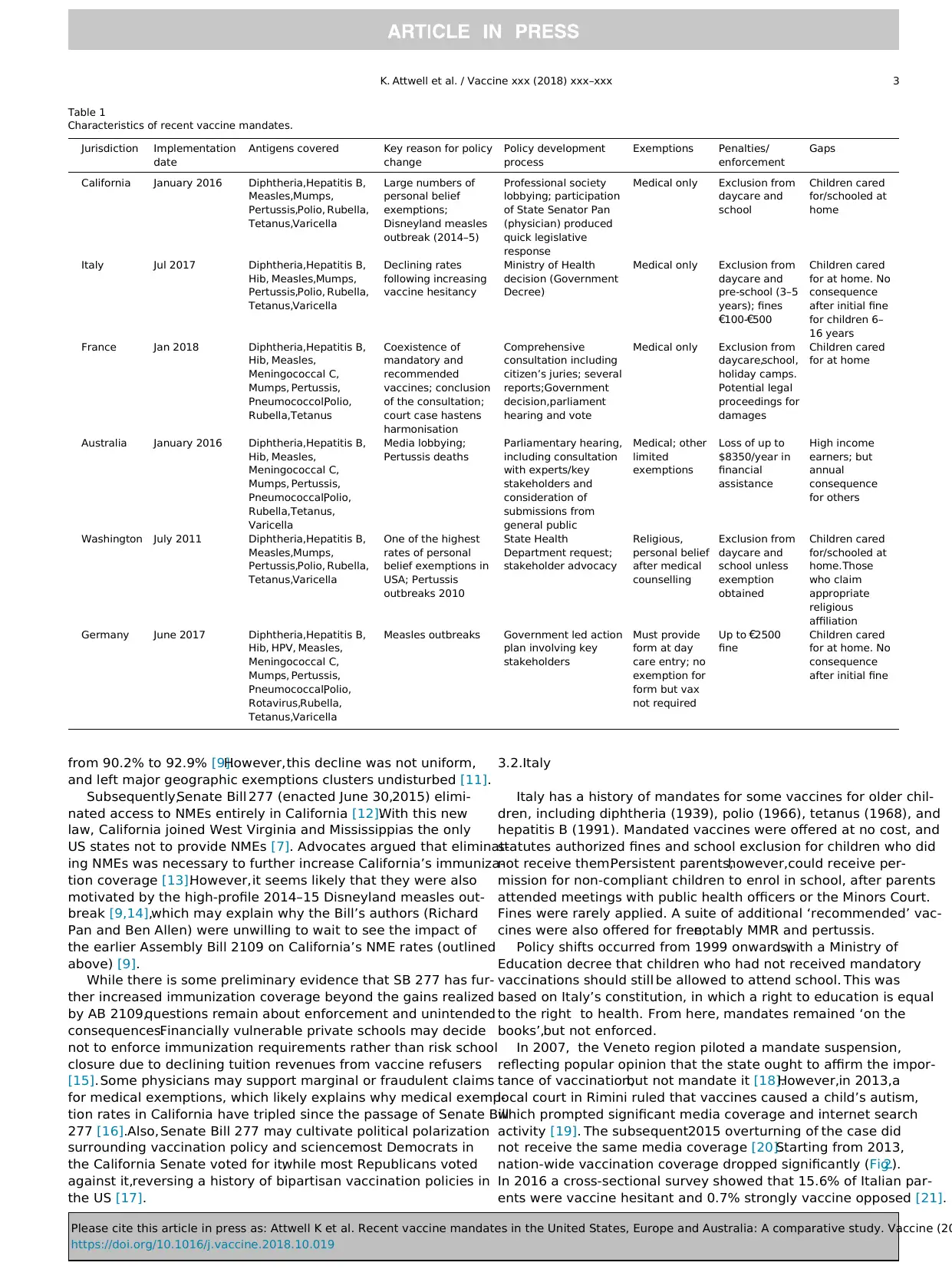

Table 1

Characteristics of recent vaccine mandates.

Jurisdiction Implementation

date

Antigens covered Key reason for policy

change

Policy development

process

Exemptions Penalties/

enforcement

Gaps

California January 2016 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Large numbers of

personal belief

exemptions;

Disneyland measles

outbreak (2014–5)

Professional society

lobbying; participation

of State Senator Pan

(physician) produced

quick legislative

response

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare and

school

Children cared

for/schooled at

home

Italy Jul 2017 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Declining rates

following increasing

vaccine hesitancy

Ministry of Health

decision (Government

Decree)

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare and

pre-school (3–5

years); fines

€100-€500

Children cared

for at home. No

consequence

after initial fine

for children 6–

16 years

France Jan 2018 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcol,Polio,

Rubella,Tetanus

Coexistence of

mandatory and

recommended

vaccines; conclusion

of the consultation;

court case hastens

harmonisation

Comprehensive

consultation including

citizen’s juries; several

reports;Government

decision,parliament

hearing and vote

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare,school,

holiday camps.

Potential legal

proceedings for

damages

Children cared

for at home

Australia January 2016 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcal,Polio,

Rubella,Tetanus,

Varicella

Media lobbying;

Pertussis deaths

Parliamentary hearing,

including consultation

with experts/key

stakeholders and

consideration of

submissions from

general public

Medical; other

limited

exemptions

Loss of up to

$8350/year in

financial

assistance

High income

earners; but

annual

consequence

for others

Washington July 2011 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

One of the highest

rates of personal

belief exemptions in

USA; Pertussis

outbreaks 2010

State Health

Department request;

stakeholder advocacy

Religious,

personal belief

after medical

counselling

Exclusion from

daycare and

school unless

exemption

obtained

Children cared

for/schooled at

home.Those

who claim

appropriate

religious

affiliation

Germany June 2017 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, HPV, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcal,Polio,

Rotavirus,Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Measles outbreaks Government led action

plan involving key

stakeholders

Must provide

form at day

care entry; no

exemption for

form but vax

not required

Up to €2500

fine

Children cared

for at home. No

consequence

after initial fine

K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx 3

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

and left major geographic exemptions clusters undisturbed [11].

Subsequently,Senate Bill 277 (enacted June 30,2015) elimi-

nated access to NMEs entirely in California [12].With this new

law, California joined West Virginia and Mississippias the only

US states not to provide NMEs [7]. Advocates argued that eliminat-

ing NMEs was necessary to further increase California’s immuniza-

tion coverage [13].However,it seems likely that they were also

motivated by the high-profile 2014–15 Disneyland measles out-

break [9,14],which may explain why the Bill’s authors (Richard

Pan and Ben Allen) were unwilling to wait to see the impact of

the earlier Assembly Bill 2109 on California’s NME rates (outlined

above) [9].

While there is some preliminary evidence that SB 277 has fur-

ther increased immunization coverage beyond the gains realized

by AB 2109,questions remain about enforcement and unintended

consequences.Financially vulnerable private schools may decide

not to enforce immunization requirements rather than risk school

closure due to declining tuition revenues from vaccine refusers

[15].Some physicians may support marginal or fraudulent claims

for medical exemptions, which likely explains why medical exemp-

tion rates in California have tripled since the passage of Senate Bill

277 [16].Also, Senate Bill 277 may cultivate political polarization

surrounding vaccination policy and science:most Democrats in

the California Senate voted for it,while most Republicans voted

against it,reversing a history of bipartisan vaccination policies in

the US [17].

3.2.Italy

Italy has a history of mandates for some vaccines for older chil-

dren, including diphtheria (1939), polio (1966), tetanus (1968), and

hepatitis B (1991). Mandated vaccines were offered at no cost, and

statutes authorized fines and school exclusion for children who did

not receive them.Persistent parents,however,could receive per-

mission for non-compliant children to enrol in school, after parents

attended meetings with public health officers or the Minors Court.

Fines were rarely applied. A suite of additional ‘recommended’ vac-

cines were also offered for free,notably MMR and pertussis.

Policy shifts occurred from 1999 onwards,with a Ministry of

Education decree that children who had not received mandatory

vaccinations should still be allowed to attend school. This was

based on Italy’s constitution, in which a right to education is equal

to the right to health. From here, mandates remained ‘on the

books’,but not enforced.

In 2007, the Veneto region piloted a mandate suspension,

reflecting popular opinion that the state ought to affirm the impor-

tance of vaccination,but not mandate it [18].However,in 2013,a

local court in Rimini ruled that vaccines caused a child’s autism,

which prompted significant media coverage and internet search

activity [19]. The subsequent2015 overturning of the case did

not receive the same media coverage [20].Starting from 2013,

nation-wide vaccination coverage dropped significantly (Fig.2).

In 2016 a cross-sectional survey showed that 15.6% of Italian par-

ents were vaccine hesitant and 0.7% strongly vaccine opposed [21].

Table 1

Characteristics of recent vaccine mandates.

Jurisdiction Implementation

date

Antigens covered Key reason for policy

change

Policy development

process

Exemptions Penalties/

enforcement

Gaps

California January 2016 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Large numbers of

personal belief

exemptions;

Disneyland measles

outbreak (2014–5)

Professional society

lobbying; participation

of State Senator Pan

(physician) produced

quick legislative

response

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare and

school

Children cared

for/schooled at

home

Italy Jul 2017 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Declining rates

following increasing

vaccine hesitancy

Ministry of Health

decision (Government

Decree)

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare and

pre-school (3–5

years); fines

€100-€500

Children cared

for at home. No

consequence

after initial fine

for children 6–

16 years

France Jan 2018 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcol,Polio,

Rubella,Tetanus

Coexistence of

mandatory and

recommended

vaccines; conclusion

of the consultation;

court case hastens

harmonisation

Comprehensive

consultation including

citizen’s juries; several

reports;Government

decision,parliament

hearing and vote

Medical only Exclusion from

daycare,school,

holiday camps.

Potential legal

proceedings for

damages

Children cared

for at home

Australia January 2016 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcal,Polio,

Rubella,Tetanus,

Varicella

Media lobbying;

Pertussis deaths

Parliamentary hearing,

including consultation

with experts/key

stakeholders and

consideration of

submissions from

general public

Medical; other

limited

exemptions

Loss of up to

$8350/year in

financial

assistance

High income

earners; but

annual

consequence

for others

Washington July 2011 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Measles,Mumps,

Pertussis,Polio, Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

One of the highest

rates of personal

belief exemptions in

USA; Pertussis

outbreaks 2010

State Health

Department request;

stakeholder advocacy

Religious,

personal belief

after medical

counselling

Exclusion from

daycare and

school unless

exemption

obtained

Children cared

for/schooled at

home.Those

who claim

appropriate

religious

affiliation

Germany June 2017 Diphtheria,Hepatitis B,

Hib, HPV, Measles,

Meningococcal C,

Mumps, Pertussis,

Pneumococcal,Polio,

Rotavirus,Rubella,

Tetanus,Varicella

Measles outbreaks Government led action

plan involving key

stakeholders

Must provide

form at day

care entry; no

exemption for

form but vax

not required

Up to €2500

fine

Children cared

for at home. No

consequence

after initial fine

K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx 3

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

In 2016 the Ministry of Health and Istituto Superiore di Sanita

began to deliberate emergency measures to address this.In July

2017, the Italian parliament passed a Ministerial Decree establish-

ing new mandates for kindergarten attendance covering six vacci-

nes that had previously only been ‘recommended’. The emergency

measure was justified by both the worrying vaccine coverage drop

and by the serious measles outbreak that spread across the coun-

try, causing approximately 5000 cases and four deaths in 2017

[22,23].The policy came into effect immediately.Furthermore,

parents who refuse vaccines for nonmedical reasons now face fines

of €100-500 [24]. Only medical exemptions are available. However,

Italy’s mandatory vaccination policy has evolved following a

change of government, with the Senate amending the bill in August

2018. Parents can now verify their children’s vaccines for them-

selves [24]. The ‘mandate’ now moves to being the least restrictive

in our analysis, but we have left in the place it occupied until these

very recent changes.

The policy change imposing mandates was influenced by polit-

ical factors,with large populist parties supporting and embolden-

ing anti-vaccination groups.(The subsequentwatering-down of

the mandate follows the political ascendancy of these forces.)

Notwithstanding strong reactionsby the latter – with a mob

assaulting pro-vaccine physicians after the law was passed [25] –

a survey conducted by Observa and published in the national

newspaper Repubblica reported rising acceptance ofmandatory

vaccines by the majority of Italians, with only 8.1% averse to man-

dates [26].A study of pregnant women conducted in 15 Italian

cities just prior to the new mandatory policy found that 81.6% of

them favoured mandatory vaccination [27].

3.3.France

As in Italy,France has a history of vaccine mandates,including

smallpox (1902),diphtheria (1938),tetanus (1940),tuberculosis

(1950) and polio (1964).Vaccination was required for admission

to schools, kindergartens,daycare centres and summercamps.

While non-compliers faced punishmentof two years imprison-

ment and a€30,000 fine,enforcement was rare [28].

In 1966, with the introduction of pertussis vaccine,French

health authorities began to embrace recommendations rather than

mandates as preferred means for increasing vaccination compli-

ance, but the older vaccines remained mandatory. Both mandatory

and recommended vaccines are subsidised by the Health Insurance

system and complementary insurance,and provisions for children

without social protection mean that families do not have to pay for

vaccines.In recent times,coverage was high for mandatory vacci-

nes (and recommended vaccines combined with them) but lower

for vaccines that were only recommended (Table 2) For example,

in 2017,coverage at 2 years of age was 73% for meningococcus C

and in 2016,coverage for MMR was 90.3% (first dose) and 80.1%

(second dose)[29]. Since 1992,regular attitudinalstudies have

shown significant changes in vaccine confidence and vaccine hesi-

tancy.In 2016,almost 75% of respondents said they were favour-

able to vaccination in general[30]. While this was a significant

increase from the low of 61.2% in 2010, when there had been con-

troversy regarding the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic vaccination

campaign,it still did not represent support akin to the coverage

required for community immunity.A measles outbreak occurring

between 2008 and 2012 is predicted to have generated over

40,000 cases, resulting in 10 deaths, and a resurgence was reported

in 2017–8 resulting in three further deaths. Most deaths were

attributed to insufficient community immunity [1], especially

among young adults who did not receive the vaccination and the

second dose (introduced in 2011 for people born before 1992).

These epidemiological drivers [1] were a factor in consolidating

France’s new mandatory vaccination policy, but change was

already in motion due to factors arising in previous years regarding

the mix of recommended and required vaccines. Specifically, DTpo-

lio was still classified as mandatory,but was only available com-

bined with recommended vaccines (Hib,pertussis,hepatitis B).In

2015, a government report recognised a need for France to harmo-

nize vaccine status either by making recommended vaccines

mandatory,or by removing mandates [31].In January 2016,the

Health Minister announced a citizen consultation process to con-

sider the issue [32]. The consultation process,which aimed to

improve vaccine confidence and coverage,included juries of citi-

zens and health professionals,a web platform for public contribu-

tions, and qualitative and quantitative studies [33].A summary

report showed that qualitative study participants wanted to retain

vaccine mandates because they did not want the burden of making

decisions about individual vaccines [33]. Individual decision-

making requires information, and participants were concerned

about equity in accessing it; they also feared that cost-cutting

could restrict it.Rather than being ‘left alone’,then, participants

preferred the state to make the decision for them.Additionally,

quantitative studies found that if mandates were abolished,13%

Fig. 2. Trends in vaccine coverage – Italy.Figure produced by authors using data publically available from Ministry of Health,Italy.

4 K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

began to deliberate emergency measures to address this.In July

2017, the Italian parliament passed a Ministerial Decree establish-

ing new mandates for kindergarten attendance covering six vacci-

nes that had previously only been ‘recommended’. The emergency

measure was justified by both the worrying vaccine coverage drop

and by the serious measles outbreak that spread across the coun-

try, causing approximately 5000 cases and four deaths in 2017

[22,23].The policy came into effect immediately.Furthermore,

parents who refuse vaccines for nonmedical reasons now face fines

of €100-500 [24]. Only medical exemptions are available. However,

Italy’s mandatory vaccination policy has evolved following a

change of government, with the Senate amending the bill in August

2018. Parents can now verify their children’s vaccines for them-

selves [24]. The ‘mandate’ now moves to being the least restrictive

in our analysis, but we have left in the place it occupied until these

very recent changes.

The policy change imposing mandates was influenced by polit-

ical factors,with large populist parties supporting and embolden-

ing anti-vaccination groups.(The subsequentwatering-down of

the mandate follows the political ascendancy of these forces.)

Notwithstanding strong reactionsby the latter – with a mob

assaulting pro-vaccine physicians after the law was passed [25] –

a survey conducted by Observa and published in the national

newspaper Repubblica reported rising acceptance ofmandatory

vaccines by the majority of Italians, with only 8.1% averse to man-

dates [26].A study of pregnant women conducted in 15 Italian

cities just prior to the new mandatory policy found that 81.6% of

them favoured mandatory vaccination [27].

3.3.France

As in Italy,France has a history of vaccine mandates,including

smallpox (1902),diphtheria (1938),tetanus (1940),tuberculosis

(1950) and polio (1964).Vaccination was required for admission

to schools, kindergartens,daycare centres and summercamps.

While non-compliers faced punishmentof two years imprison-

ment and a€30,000 fine,enforcement was rare [28].

In 1966, with the introduction of pertussis vaccine,French

health authorities began to embrace recommendations rather than

mandates as preferred means for increasing vaccination compli-

ance, but the older vaccines remained mandatory. Both mandatory

and recommended vaccines are subsidised by the Health Insurance

system and complementary insurance,and provisions for children

without social protection mean that families do not have to pay for

vaccines.In recent times,coverage was high for mandatory vacci-

nes (and recommended vaccines combined with them) but lower

for vaccines that were only recommended (Table 2) For example,

in 2017,coverage at 2 years of age was 73% for meningococcus C

and in 2016,coverage for MMR was 90.3% (first dose) and 80.1%

(second dose)[29]. Since 1992,regular attitudinalstudies have

shown significant changes in vaccine confidence and vaccine hesi-

tancy.In 2016,almost 75% of respondents said they were favour-

able to vaccination in general[30]. While this was a significant

increase from the low of 61.2% in 2010, when there had been con-

troversy regarding the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic vaccination

campaign,it still did not represent support akin to the coverage

required for community immunity.A measles outbreak occurring

between 2008 and 2012 is predicted to have generated over

40,000 cases, resulting in 10 deaths, and a resurgence was reported

in 2017–8 resulting in three further deaths. Most deaths were

attributed to insufficient community immunity [1], especially

among young adults who did not receive the vaccination and the

second dose (introduced in 2011 for people born before 1992).

These epidemiological drivers [1] were a factor in consolidating

France’s new mandatory vaccination policy, but change was

already in motion due to factors arising in previous years regarding

the mix of recommended and required vaccines. Specifically, DTpo-

lio was still classified as mandatory,but was only available com-

bined with recommended vaccines (Hib,pertussis,hepatitis B).In

2015, a government report recognised a need for France to harmo-

nize vaccine status either by making recommended vaccines

mandatory,or by removing mandates [31].In January 2016,the

Health Minister announced a citizen consultation process to con-

sider the issue [32]. The consultation process,which aimed to

improve vaccine confidence and coverage,included juries of citi-

zens and health professionals,a web platform for public contribu-

tions, and qualitative and quantitative studies [33].A summary

report showed that qualitative study participants wanted to retain

vaccine mandates because they did not want the burden of making

decisions about individual vaccines [33]. Individual decision-

making requires information, and participants were concerned

about equity in accessing it; they also feared that cost-cutting

could restrict it.Rather than being ‘left alone’,then, participants

preferred the state to make the decision for them.Additionally,

quantitative studies found that if mandates were abolished,13%

Fig. 2. Trends in vaccine coverage – Italy.Figure produced by authors using data publically available from Ministry of Health,Italy.

4 K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

of parents would no longer vaccinate their children for DTPolio,

and that socio-economically disadvantaged parentswould be

over-represented in that population [33].As a result,participants

favoured extending mandatory vaccination to allvaccines for a

limited period. In return,they required transparency,information,

listening and communication,an official website, education and

training for health professionals to enhance their commitment,

vaccine education at schools,simplification of access,and expan-

sion of a vaccine injury compensation scheme [33].

The issue came to a head in February 2017. Vaccine refusers had

contested the mix of mandatory/recommended vaccines,and the

Council of State advised that the state must make mandated vacci-

nes available without combined recommended vaccines within six

months [34].Thus,on 5 July 2017 the Health Minister announced

that all recommended vaccines for children under 18 months age

old would become mandatory in 2018 (see Table 1).While the

specific criminal sanction for refusing vaccines has been abolished

[1], parents can still be prosecuted for putting their children or

others at risk [35].The decision was made to focus on new birth

cohorts rather than catch up schemes for older children,for epi-

demiological and enforcement reasons. Regarding the latter,

excluding older children from school was regarded as socially

unacceptable and risked inflaming the anti-vaccination movement

[1]. Further detail and perspectives on the French policy response

and process can be found here [36,37].

3.4.Australia

Australian vaccination policy has linked vaccination compliance

to financial incentives since 1998. This started with a non-means-

tested designated vaccination payment at age-based milestones. In

2012 the financial incentive was instead linked to annual means

tested end of financial year supplements [38]. Since 1998 vaccina-

tion status has also determined eligibility for childcare subsidies,

including a non-means-tested annual rebate [39]. Vaccine refusers

could submit a Conscientious Objector Form following counselling

by an immunisation provider,and still access incentives and ben-

efits. All recommended vaccines were covered by these policies,

and were available free of charge. Vaccination coverage in Australia

sat around 91% but refusers clustered in regions with coverage as

low as 50% [40]. In 2012, a representative national study found that

over one-fifth of adult Australians believed were concerned that

vaccines were insufficiently safety-tested,could cause autism,or

would weaken their child’s immune system [41].

In 2013,the main newspaper in New South Wales began cam-

paigning to deny vaccine refusers access to uptake-linked benefits.

They mobilised a discourse of collective responsibility and utilised

the high profile pertussis deaths of Australian infants in low cover-

age areas [42]. The ‘No Jab, No Pay’ campaign achieved popular and

government support. The latter aligned with a discourse of ‘mutual

obligation’ linking benefits to responsibilities [43], and recognition

that budget savings ofover $500 million in five years could be

made by withdrawing resources from refusers [44].

The sole purpose of the policy change was to govern vaccine

refusal; access and complacency were already governed by existing

administrative procedures. The ‘No Jab, No Pay’law – named after

the Daily Telegraph’scampaign (to which the Prime Minister

explicitly alluded in his announcement) – came into effect on 1

January 2016 [45,46].In its journey through Parliament,it was

referred to the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee,

which invited submissions and held two 25 min public hearings

[47]. Experts, activists and members of the public presented a

range of views, but the legislation passed, removing Conscientious

Objection and leaving medical exemptions as the only way for the

unvaccinated to access entitlements [48]. Refusers stood to lose up

to approximately $8350 per year, which increased with changes to

childcare subsidies in 2018 [49]. Neither the old nor the new policy

delivered any consequences for medium-to-high income vaccine

refusers whose children were not in daycare,which is attended

by approximately one quarter of Australian children [50].

‘No Jab, No Pay’ met popular approval,although some public

intellectuals lamented the loss of parental choice [51]. The Govern-

ment claimed the policy’s success in a subsequent release of fig-

ures showing vaccination coverage had climbed to 92–93%

[52,53].State-based ‘No Jab,No Play’ policy changes,advocated

by the FederalGovernment,limit unvaccinated children’s access

to childcare centres [54].It is beyond the scope of this article to

analyze these additionalstate-levelpolicies, suffice to say that

they, like the other mandates explored here,vary with regard to

structure,severity and enforcement.

3.5.Washington

We have provided an overview ofUS vaccination policy and

national rates of vaccine hesitancy in the section on California,

above. Washington state was one state that made nonmedical

exemptions readily available,and historically had some of the

highest rates in the U.S [55].In the three years leading up to the

introduction of a new policy, exemption rates for schoolentry

mandates in Washington ranged from approximately 7–9%. (While

this figure includes medical exemptions,these made up a very

small fraction of the total number of exemptions.) [56]. In the con-

text of large pertussis outbreaks in multiple states in 2010 that

included Washington,the state health department submitted an

agency request to the legislature for a change in the state’s exemp-

tion law. They sought to ‘‘Reduce the convenience of nonmedical

exemptions only to the extent exempting is equalto the effort

required to vaccinate (or provide proof of vaccination)” and

‘‘Increase public education and awareness of the dangers of

vaccine-preventable disease and the benefits ofimmunization.”

[57].

Senate Bill 5005 (SB5005) was implemented in July 2011 and

required parents seeking an exemption to submit a ‘‘Certificate of

Exemption” or a letter signed by a licensed healthcare provider

(23) verifying that the provider has discussed the benefits/risks

of vaccines with the parent(s). However, parents who demonstrate

affiliation with a religious entity that does not permit medical

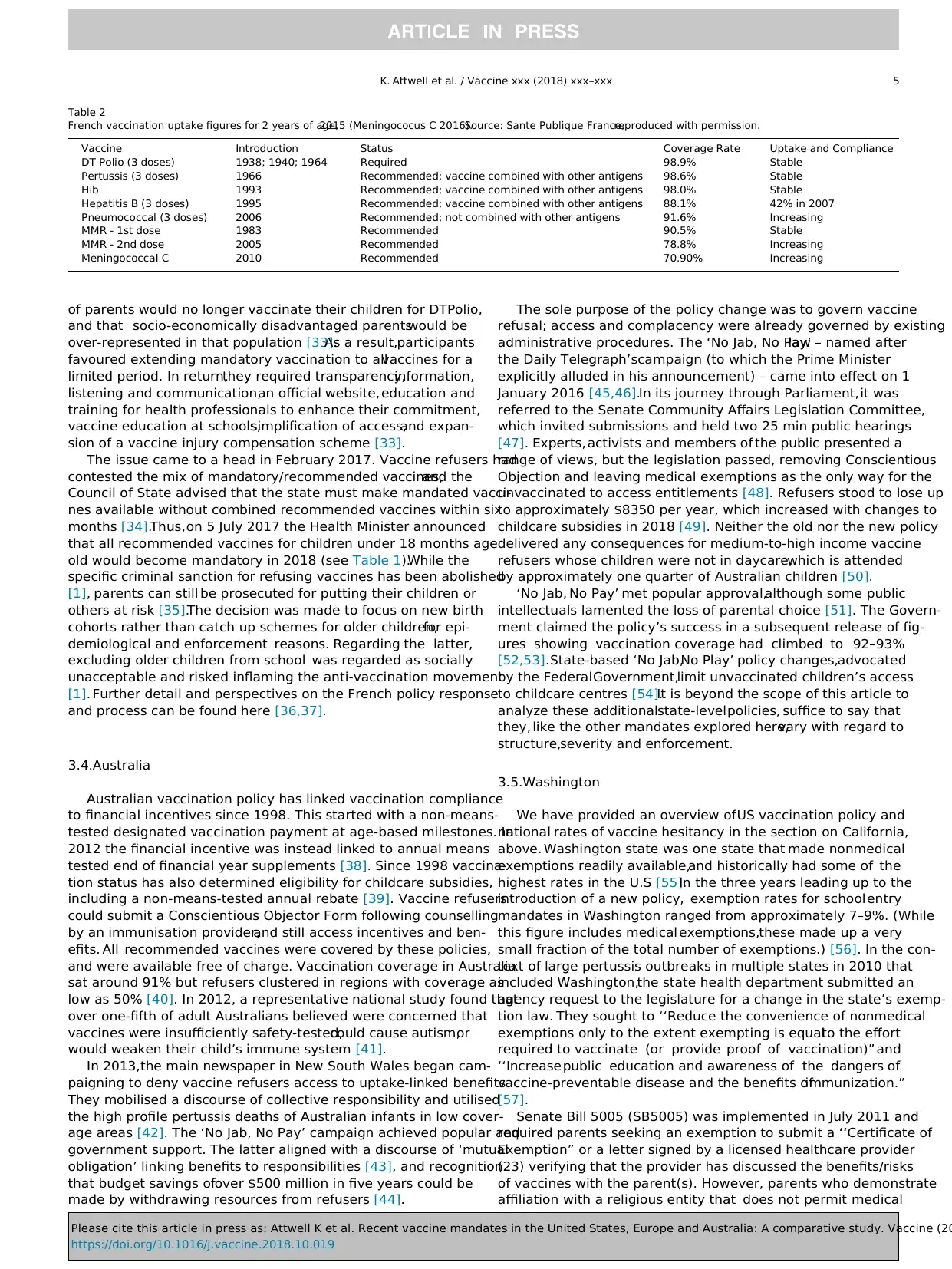

Table 2

French vaccination uptake figures for 2 years of age,2015 (Meningococus C 2016).Source: Sante Publique France,reproduced with permission.

Vaccine Introduction Status Coverage Rate Uptake and Compliance

DT Polio (3 doses) 1938; 1940; 1964 Required 98.9% Stable

Pertussis (3 doses) 1966 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 98.6% Stable

Hib 1993 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 98.0% Stable

Hepatitis B (3 doses) 1995 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 88.1% 42% in 2007

Pneumococcal (3 doses) 2006 Recommended; not combined with other antigens 91.6% Increasing

MMR - 1st dose 1983 Recommended 90.5% Stable

MMR - 2nd dose 2005 Recommended 78.8% Increasing

Meningococcal C 2010 Recommended 70.90% Increasing

K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx 5

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

and that socio-economically disadvantaged parentswould be

over-represented in that population [33].As a result,participants

favoured extending mandatory vaccination to allvaccines for a

limited period. In return,they required transparency,information,

listening and communication,an official website, education and

training for health professionals to enhance their commitment,

vaccine education at schools,simplification of access,and expan-

sion of a vaccine injury compensation scheme [33].

The issue came to a head in February 2017. Vaccine refusers had

contested the mix of mandatory/recommended vaccines,and the

Council of State advised that the state must make mandated vacci-

nes available without combined recommended vaccines within six

months [34].Thus,on 5 July 2017 the Health Minister announced

that all recommended vaccines for children under 18 months age

old would become mandatory in 2018 (see Table 1).While the

specific criminal sanction for refusing vaccines has been abolished

[1], parents can still be prosecuted for putting their children or

others at risk [35].The decision was made to focus on new birth

cohorts rather than catch up schemes for older children,for epi-

demiological and enforcement reasons. Regarding the latter,

excluding older children from school was regarded as socially

unacceptable and risked inflaming the anti-vaccination movement

[1]. Further detail and perspectives on the French policy response

and process can be found here [36,37].

3.4.Australia

Australian vaccination policy has linked vaccination compliance

to financial incentives since 1998. This started with a non-means-

tested designated vaccination payment at age-based milestones. In

2012 the financial incentive was instead linked to annual means

tested end of financial year supplements [38]. Since 1998 vaccina-

tion status has also determined eligibility for childcare subsidies,

including a non-means-tested annual rebate [39]. Vaccine refusers

could submit a Conscientious Objector Form following counselling

by an immunisation provider,and still access incentives and ben-

efits. All recommended vaccines were covered by these policies,

and were available free of charge. Vaccination coverage in Australia

sat around 91% but refusers clustered in regions with coverage as

low as 50% [40]. In 2012, a representative national study found that

over one-fifth of adult Australians believed were concerned that

vaccines were insufficiently safety-tested,could cause autism,or

would weaken their child’s immune system [41].

In 2013,the main newspaper in New South Wales began cam-

paigning to deny vaccine refusers access to uptake-linked benefits.

They mobilised a discourse of collective responsibility and utilised

the high profile pertussis deaths of Australian infants in low cover-

age areas [42]. The ‘No Jab, No Pay’ campaign achieved popular and

government support. The latter aligned with a discourse of ‘mutual

obligation’ linking benefits to responsibilities [43], and recognition

that budget savings ofover $500 million in five years could be

made by withdrawing resources from refusers [44].

The sole purpose of the policy change was to govern vaccine

refusal; access and complacency were already governed by existing

administrative procedures. The ‘No Jab, No Pay’law – named after

the Daily Telegraph’scampaign (to which the Prime Minister

explicitly alluded in his announcement) – came into effect on 1

January 2016 [45,46].In its journey through Parliament,it was

referred to the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee,

which invited submissions and held two 25 min public hearings

[47]. Experts, activists and members of the public presented a

range of views, but the legislation passed, removing Conscientious

Objection and leaving medical exemptions as the only way for the

unvaccinated to access entitlements [48]. Refusers stood to lose up

to approximately $8350 per year, which increased with changes to

childcare subsidies in 2018 [49]. Neither the old nor the new policy

delivered any consequences for medium-to-high income vaccine

refusers whose children were not in daycare,which is attended

by approximately one quarter of Australian children [50].

‘No Jab, No Pay’ met popular approval,although some public

intellectuals lamented the loss of parental choice [51]. The Govern-

ment claimed the policy’s success in a subsequent release of fig-

ures showing vaccination coverage had climbed to 92–93%

[52,53].State-based ‘No Jab,No Play’ policy changes,advocated

by the FederalGovernment,limit unvaccinated children’s access

to childcare centres [54].It is beyond the scope of this article to

analyze these additionalstate-levelpolicies, suffice to say that

they, like the other mandates explored here,vary with regard to

structure,severity and enforcement.

3.5.Washington

We have provided an overview ofUS vaccination policy and

national rates of vaccine hesitancy in the section on California,

above. Washington state was one state that made nonmedical

exemptions readily available,and historically had some of the

highest rates in the U.S [55].In the three years leading up to the

introduction of a new policy, exemption rates for schoolentry

mandates in Washington ranged from approximately 7–9%. (While

this figure includes medical exemptions,these made up a very

small fraction of the total number of exemptions.) [56]. In the con-

text of large pertussis outbreaks in multiple states in 2010 that

included Washington,the state health department submitted an

agency request to the legislature for a change in the state’s exemp-

tion law. They sought to ‘‘Reduce the convenience of nonmedical

exemptions only to the extent exempting is equalto the effort

required to vaccinate (or provide proof of vaccination)” and

‘‘Increase public education and awareness of the dangers of

vaccine-preventable disease and the benefits ofimmunization.”

[57].

Senate Bill 5005 (SB5005) was implemented in July 2011 and

required parents seeking an exemption to submit a ‘‘Certificate of

Exemption” or a letter signed by a licensed healthcare provider

(23) verifying that the provider has discussed the benefits/risks

of vaccines with the parent(s). However, parents who demonstrate

affiliation with a religious entity that does not permit medical

Table 2

French vaccination uptake figures for 2 years of age,2015 (Meningococus C 2016).Source: Sante Publique France,reproduced with permission.

Vaccine Introduction Status Coverage Rate Uptake and Compliance

DT Polio (3 doses) 1938; 1940; 1964 Required 98.9% Stable

Pertussis (3 doses) 1966 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 98.6% Stable

Hib 1993 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 98.0% Stable

Hepatitis B (3 doses) 1995 Recommended; vaccine combined with other antigens 88.1% 42% in 2007

Pneumococcal (3 doses) 2006 Recommended; not combined with other antigens 91.6% Increasing

MMR - 1st dose 1983 Recommended 90.5% Stable

MMR - 2nd dose 2005 Recommended 78.8% Increasing

Meningococcal C 2010 Recommended 70.90% Increasing

K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx 5

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (20

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

treatment to children are exempted. This bill passed with the sup-

port of a substantial majority of both houses of the state legisla-

ture. While a substantially higher proportion of Democratic

legislators voted for this bill compared to their Republican peers,

there was still significant Republican support [58,59].

Support from local immunization groups,and state affiliates of

professional medical associations, such as the Washington chapter

of American Academy of Pediatrics, played a major role in generat-

ing support for this legislation.Moreover,Washington’s Vaccine

Advisory Committee – an advisory body comprised of professional

organizations,government agencies,and other healthcare stake-

holders – and local health departments supported this legislation.

After SB5005 was implemented,there was a relative decline of

more than 40% in nonmedical exemptions [56]. Moreover, with the

exception of Hepatitis B vaccine, state-level vaccine coverage

increased for all vaccines required for schoolentrance.Equally

importantly,SB5005 was associated with a decline in geographic

clustering of children with vaccine exemptions [56].

3.6.Germany

In West Germany,smallpox vaccination was mandatory until

1982. In East Germany,all childhood vaccines were mandatory,

but a generous list of medical contraindications was generally

interpreted to include religious objections. Following reunification

in 1990, all vaccines became voluntary. Vaccines recommended by

Germany’s Standing Committee of Vaccination,its technical advi-

sory body,are free of charge since they are covered by a universal

health insurance scheme (Table 1).

German vaccine coverage at school entry has been high; over

90% for all vaccines except hepatitis B. However, coverage in

younger children has been lower and variable across Germany’s

decentralised federal regions,demonstrating that children are not

being vaccinated in accordance with the vaccine schedule [60].

Attitudinal studies show that up to 18% of people are undecided

about vaccines and are rejecting some,such as varicella [61]. Ger-

many has repeatedly faced outbreaks of measles, including

amongst poorly reached migrant communities. This led to an

update of the National Action Plan for the Elimination Measles

and Rubella Elimination (2015) with all important stakeholders

involved and legal initiatives to improve vaccination coverage.

In 2015 the Federal Government passed the National Preventa-

tive Healthcare Act to strengthen health promotion.Parents now

have to provide evidence of routine check-ups, which include

counselling by a physician about vaccination, before their children

can attend daycare. This provision was tightened in July 2017 with

a requirement that kindergartens notify public health authorities if

parents have not provided the required evidence.Public health

authorities can then invite non-compliant parents for consulta-

tions or fine them up to€2500.A similar policy had already been

employed in some Länder,where it was associated with increased

vaccination coverage [62].

It is noteworthy that,as in Washington,the policy instrument

governing uptake penalises non-compliance with administrative

process,rather than vaccination.The policy therefore permits par-

ental rejection of vaccines,but only following counselling.It gov-

erns access (parents must visit a physician either way) and

governs acceptance with a focus on informed refusal. It also resem-

bles the Australian policy prior to ‘No Jab,No Pay,’although non-

compliance in Germany attracts sanctions rather than the loss of

entitlements or benefits.However,93% of German children aged

3–6 and 32% of children aged 0–3 are enrolled in daycare, meaning

that the sanctions should have a wide reach [63].Germans con-

tinue to debate the merits and disadvantages of mandatory vacci-

nation [64]. However, at present the strategy remains one of

enhancing trust, improving service delivery, filling adult immunity

gaps and utilising the daycare certificates.

4. Discussion

The new mandate instruments adopted by governments come

in a variety of shapes and sizes.Some govern vaccination itself;

others merely require rejecters to comply with administrative bur-

dens, which themselves can vary. Mandate instruments also oper-

ate across several dimensions that cannot be captured by merely

analysing written laws or regulations.The simplified continuum

we introduced earlier could be supplemented with additional axes,

relating to the severity of consequences for non-compliance,and

the intensity of enforcement.This would help us to consider the

complexity of how mandates operate.For example,fines for non-

compliance might seem like a severe outcome of refusal, but if they

are low and only applied once, then that particular mandate instru-

ment may prove less consequentialthan one which excludes

unvaccinated children from school for the duration of their educa-

tion. Likewise, a mandate that is not enforced (as was the case with

some European regimes prior to recent changes) might not really

‘exist’,although its presence likely affects social norms.

Politico-cultural context and vaccine policy history are also rel-

evant to governments’ decisions about vaccine mandates. East Ger-

many’s history ofoppressive state controlmay inform a unified

Germany’s current commitment to voluntarism.Meanwhile, the

phenomenon of path dependency can help to explain why other

jurisdictions in this study implemented mandatory systems build-

ing upon and modifying earlier regimes, and hence retaining differ-

ences with regard to target populations and instruments.Path

dependency illuminates how earlier decisions inform later ones,

directing decision-makers to continue down established pathways

[65].For example,Australia has a decades-old policy of providing

financial incentives to parents for their children’s vaccination sta-

tus from birth, which is one reason why its recent reforms focused

on this system of incentives,and therefore had impact on even

very young children.Meanwhile,the practice in the US of linking

vaccination to primary school entry is a primary reason why school

immunization requirements are the ‘obvious’site for mandatory

policy tightening in jurisdictions there,which results in policies

that cannot effect mass change on the vaccination coverage rates

of infants and toddlers.Path dependency can also inform publics’

levels of familiarity or comfort with mandates,emboldening poli-

cymakers to institute them.For example,the uncontroversial his-

tory of selective (and largely unenforced)vaccine mandates in

Italy and France may have primed the populace for their reinvigo-

ration in the face of measles outbreaks [1], even if this did generate

some vocalopposition.Australia also has compulsory voting for

Federal and State elections,suggesting some level of comfort with

compulsion that serves the collective there. Finally, it is also note-

worthy that public commitments to promote equality and eradi-

cate disadvantageinformed citizen consultation participants’

support for mandates in France, a country whose nationalist myths

centre on collective action and solidarity.

There are also distinctions in enforcementmechanisms and

agents responsible for enforcement between the mandate models

explored here. There is a comprehensive research program evident

even just focusing on the latter.Do health-care workers responsi-

ble for signing exemption forms work directly for the state or

receive arms-length subsidies? How does the state regulate their

actions with regard to reporting non-compliance? What about

the administrators of schools and daycare centres,now co-opted

as enforcement agents in some jurisdictions and required to pass

information about non-compliance to authorities? Clearly,there

are far greater level of complexity than we have the opportunity

6 K. Attwell et al. / Vaccine xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article in press as: Attwell K et al. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine (2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.019

port of a substantial majority of both houses of the state legisla-

ture. While a substantially higher proportion of Democratic

legislators voted for this bill compared to their Republican peers,

there was still significant Republican support [58,59].

Support from local immunization groups,and state affiliates of

professional medical associations, such as the Washington chapter

of American Academy of Pediatrics, played a major role in generat-

ing support for this legislation.Moreover,Washington’s Vaccine

Advisory Committee – an advisory body comprised of professional

organizations,government agencies,and other healthcare stake-

holders – and local health departments supported this legislation.

After SB5005 was implemented,there was a relative decline of

more than 40% in nonmedical exemptions [56]. Moreover, with the

exception of Hepatitis B vaccine, state-level vaccine coverage

increased for all vaccines required for schoolentrance.Equally

importantly,SB5005 was associated with a decline in geographic

clustering of children with vaccine exemptions [56].

3.6.Germany

In West Germany,smallpox vaccination was mandatory until

1982. In East Germany,all childhood vaccines were mandatory,

but a generous list of medical contraindications was generally

interpreted to include religious objections. Following reunification

in 1990, all vaccines became voluntary. Vaccines recommended by

Germany’s Standing Committee of Vaccination,its technical advi-

sory body,are free of charge since they are covered by a universal

health insurance scheme (Table 1).

German vaccine coverage at school entry has been high; over

90% for all vaccines except hepatitis B. However, coverage in

younger children has been lower and variable across Germany’s

decentralised federal regions,demonstrating that children are not

being vaccinated in accordance with the vaccine schedule [60].

Attitudinal studies show that up to 18% of people are undecided

about vaccines and are rejecting some,such as varicella [61]. Ger-

many has repeatedly faced outbreaks of measles, including

amongst poorly reached migrant communities. This led to an

update of the National Action Plan for the Elimination Measles

and Rubella Elimination (2015) with all important stakeholders

involved and legal initiatives to improve vaccination coverage.

In 2015 the Federal Government passed the National Preventa-

tive Healthcare Act to strengthen health promotion.Parents now

have to provide evidence of routine check-ups, which include

counselling by a physician about vaccination, before their children

can attend daycare. This provision was tightened in July 2017 with

a requirement that kindergartens notify public health authorities if

parents have not provided the required evidence.Public health

authorities can then invite non-compliant parents for consulta-

tions or fine them up to€2500.A similar policy had already been

employed in some Länder,where it was associated with increased

vaccination coverage [62].

It is noteworthy that,as in Washington,the policy instrument

governing uptake penalises non-compliance with administrative

process,rather than vaccination.The policy therefore permits par-

ental rejection of vaccines,but only following counselling.It gov-

erns access (parents must visit a physician either way) and

governs acceptance with a focus on informed refusal. It also resem-

bles the Australian policy prior to ‘No Jab,No Pay,’although non-

compliance in Germany attracts sanctions rather than the loss of

entitlements or benefits.However,93% of German children aged

3–6 and 32% of children aged 0–3 are enrolled in daycare, meaning

that the sanctions should have a wide reach [63].Germans con-

tinue to debate the merits and disadvantages of mandatory vacci-