Australian Milk Market: Competitive Structure and Policy Essay

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/13

|6

|1464

|14

Essay

AI Summary

This essay provides an in-depth analysis of the Australian milk market, arguing that it likely operates under perfect competition. The essay supports this claim by examining key characteristics such as the large number of sellers, homogeneous products, price-taking behavior, free entry and exit, perfect market knowledge, and the absence of government intervention. It further explores how the exit of milk farmers impacts market supply and prices, illustrating these effects with supply and demand graphs. The essay then delves into the concept of demand elasticity for milk, categorizing it as an inelastic good, and discusses the implications of price changes on consumer demand. Finally, the essay proposes several policy measures that could support Australian milk farmers, including the implementation of price floors and the establishment of cooperatives to enhance their market power and negotiate fairer prices. The essay concludes by referencing relevant academic literature to support its arguments.

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 1

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY

Student’s Name

Institution Affiliation

Course

Facilitator

Date

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY

Student’s Name

Institution Affiliation

Course

Facilitator

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 2

The Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market where no single

seller can affect the market price (Azevedo and Gottlieb 2017, p.67). A perfectively competitive

market structure describes a market which has a vast number of buyers and sellers trading

products which are homogeneous at a single price set in the entire market. The following features

suggest a perfectly competitive market structure for the Australian milk market. Firstly, the

market is made up of a vast number of sellers. From the article, the Australian milk market

currently has 5669 dairy firms which is quite a huge number but it’s still a decrease as compared

with the year 2010 where the number of dairy farms was high at 7511. Secondly, the Australian

milk market involves the buying and selling of homogeneous products (that is milk) (Mirman,

Salgueiro and Santugini 2015). This therefore means that consumers are indifferent when it

comes to buying the Australian milk market products and they end up purchasing the product

which is sold cheaply. It therefore calls for production efficiency among the Australian dairy

farms in order to minimize production costs and maximize profits. Thirdly, the milk market

involves price taking by the dairy farmers. The Australian dairy farmers have to accept the price

offered for sale in the market by the processors and supermarkets (for example “Murray

Goulburn, Fonterra and Coles and Woolworths”). The dairy farmers have little bargaining power

in the market and therefore they have to accept the prevailing market price or else risk not selling

their milk at all. Fourthly, the Australian milk market is free for entry and exit (Geroski and

Jacquemin 2013) by dairy farmers. Dairy farmers are free to enter the industry if they can bear

the competition and leave if they make unsustainable losses. For instance, from the article, since

2010, the Australian dairy farms have exited the market due to losses decreasing the number of

Australian dairy farms from 7511 in 2010 to 5669 currently. Fifthly, the milk market involves a

perfect knowledge about the prevailing market prices by both the buyers and sellers. From the

The Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market where no single

seller can affect the market price (Azevedo and Gottlieb 2017, p.67). A perfectively competitive

market structure describes a market which has a vast number of buyers and sellers trading

products which are homogeneous at a single price set in the entire market. The following features

suggest a perfectly competitive market structure for the Australian milk market. Firstly, the

market is made up of a vast number of sellers. From the article, the Australian milk market

currently has 5669 dairy firms which is quite a huge number but it’s still a decrease as compared

with the year 2010 where the number of dairy farms was high at 7511. Secondly, the Australian

milk market involves the buying and selling of homogeneous products (that is milk) (Mirman,

Salgueiro and Santugini 2015). This therefore means that consumers are indifferent when it

comes to buying the Australian milk market products and they end up purchasing the product

which is sold cheaply. It therefore calls for production efficiency among the Australian dairy

farms in order to minimize production costs and maximize profits. Thirdly, the milk market

involves price taking by the dairy farmers. The Australian dairy farmers have to accept the price

offered for sale in the market by the processors and supermarkets (for example “Murray

Goulburn, Fonterra and Coles and Woolworths”). The dairy farmers have little bargaining power

in the market and therefore they have to accept the prevailing market price or else risk not selling

their milk at all. Fourthly, the Australian milk market is free for entry and exit (Geroski and

Jacquemin 2013) by dairy farmers. Dairy farmers are free to enter the industry if they can bear

the competition and leave if they make unsustainable losses. For instance, from the article, since

2010, the Australian dairy farms have exited the market due to losses decreasing the number of

Australian dairy farms from 7511 in 2010 to 5669 currently. Fifthly, the milk market involves a

perfect knowledge about the prevailing market prices by both the buyers and sellers. From the

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 3

article, the Australian dairy farms and customers know supermarkets sell a litre of milk for $1

and buyers know their expected return from the sale. Lastly, the Australian milk market is free

from government intervention since it has been deregulated for the last two decades. The absence

of government intervention is a strong feature of the perfectly competitive market structure and

hence the Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market.

A milk farmer may decide to stay in the industry even if they make a loss. In the short-

run period, the total business cost is made up of the variable and fixed costs and the business

must pay its fixed costs whether it operates or not. If a business is making losses in the short-run

but its revenue is greater than its average variable costs, then it means it can pay its variable costs

and use the remaining revenue to pay all or part of its fixed costs (Mas-Colell 2014). This

therefore means, a milk farmer’s revenue exceeds his or her average variable costs and therefore

he or she can pay the variable costs and all or part of the fixed costs and therefore, he or she can

stay in the market since in the long-run he or she may end covering all the costs and even make a

profit.

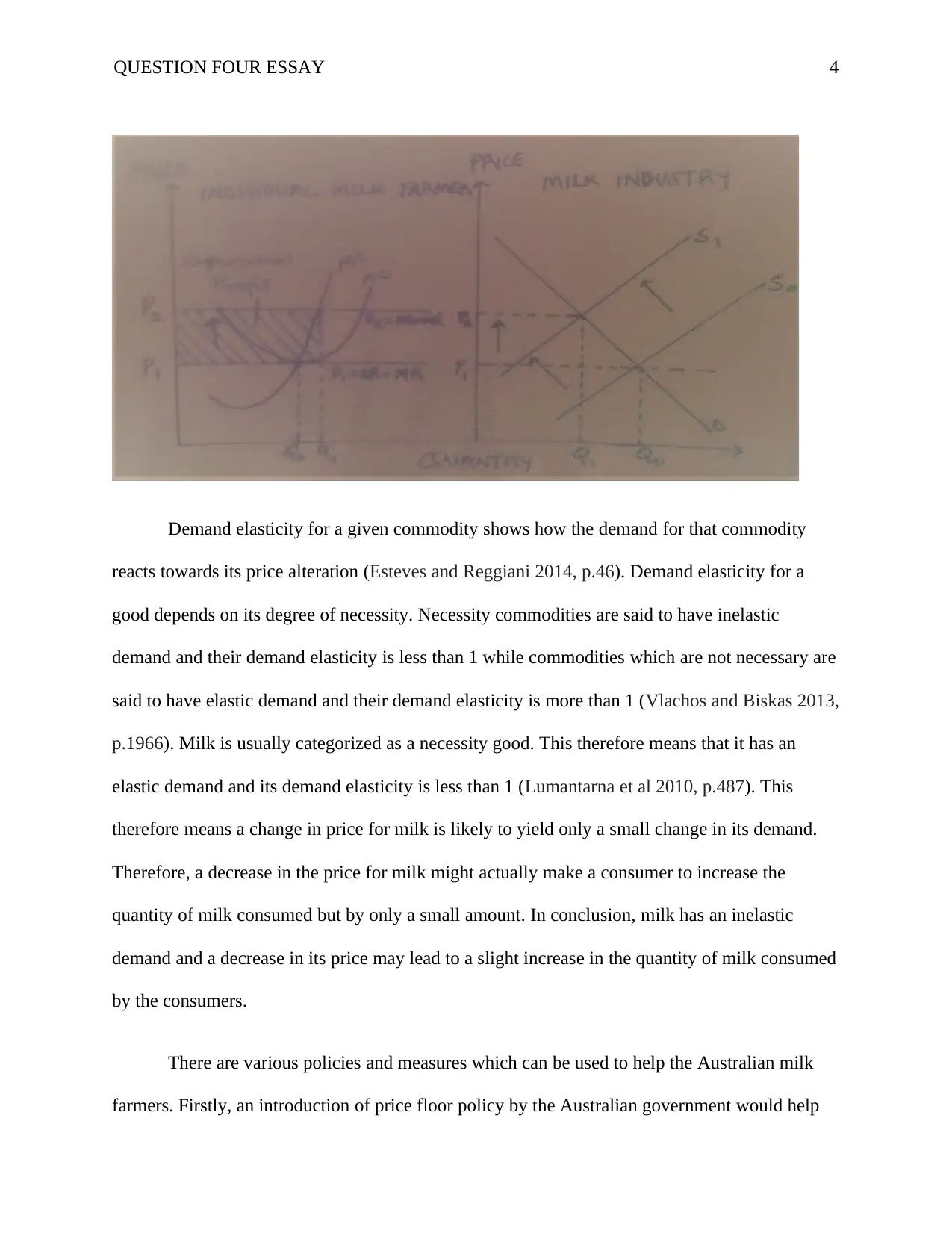

Since the Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market structure,

the graph for an individual milk farm and the milk industry has been used to explain that the exit

of some milk farmers from the industry in the long-run period will lead to an increase in milk

price. When some farmers exit the industry in the long-run period, the supply of milk in the

industry will decrease and as a result the supply curve will shift from S0 to S1 towards the left

direction. This will decrease the quantity of milk in the milk market from Q0 to Q1. As a result,

the demand for milk in the market will increase and push milk prices upwards from P0 to P1 as

indicated in the diagram below.

article, the Australian dairy farms and customers know supermarkets sell a litre of milk for $1

and buyers know their expected return from the sale. Lastly, the Australian milk market is free

from government intervention since it has been deregulated for the last two decades. The absence

of government intervention is a strong feature of the perfectly competitive market structure and

hence the Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market.

A milk farmer may decide to stay in the industry even if they make a loss. In the short-

run period, the total business cost is made up of the variable and fixed costs and the business

must pay its fixed costs whether it operates or not. If a business is making losses in the short-run

but its revenue is greater than its average variable costs, then it means it can pay its variable costs

and use the remaining revenue to pay all or part of its fixed costs (Mas-Colell 2014). This

therefore means, a milk farmer’s revenue exceeds his or her average variable costs and therefore

he or she can pay the variable costs and all or part of the fixed costs and therefore, he or she can

stay in the market since in the long-run he or she may end covering all the costs and even make a

profit.

Since the Australian milk market is likely to be a perfectly competitive market structure,

the graph for an individual milk farm and the milk industry has been used to explain that the exit

of some milk farmers from the industry in the long-run period will lead to an increase in milk

price. When some farmers exit the industry in the long-run period, the supply of milk in the

industry will decrease and as a result the supply curve will shift from S0 to S1 towards the left

direction. This will decrease the quantity of milk in the milk market from Q0 to Q1. As a result,

the demand for milk in the market will increase and push milk prices upwards from P0 to P1 as

indicated in the diagram below.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 4

Demand elasticity for a given commodity shows how the demand for that commodity

reacts towards its price alteration (Esteves and Reggiani 2014, p.46). Demand elasticity for a

good depends on its degree of necessity. Necessity commodities are said to have inelastic

demand and their demand elasticity is less than 1 while commodities which are not necessary are

said to have elastic demand and their demand elasticity is more than 1 (Vlachos and Biskas 2013,

p.1966). Milk is usually categorized as a necessity good. This therefore means that it has an

elastic demand and its demand elasticity is less than 1 (Lumantarna et al 2010, p.487). This

therefore means a change in price for milk is likely to yield only a small change in its demand.

Therefore, a decrease in the price for milk might actually make a consumer to increase the

quantity of milk consumed but by only a small amount. In conclusion, milk has an inelastic

demand and a decrease in its price may lead to a slight increase in the quantity of milk consumed

by the consumers.

There are various policies and measures which can be used to help the Australian milk

farmers. Firstly, an introduction of price floor policy by the Australian government would help

Demand elasticity for a given commodity shows how the demand for that commodity

reacts towards its price alteration (Esteves and Reggiani 2014, p.46). Demand elasticity for a

good depends on its degree of necessity. Necessity commodities are said to have inelastic

demand and their demand elasticity is less than 1 while commodities which are not necessary are

said to have elastic demand and their demand elasticity is more than 1 (Vlachos and Biskas 2013,

p.1966). Milk is usually categorized as a necessity good. This therefore means that it has an

elastic demand and its demand elasticity is less than 1 (Lumantarna et al 2010, p.487). This

therefore means a change in price for milk is likely to yield only a small change in its demand.

Therefore, a decrease in the price for milk might actually make a consumer to increase the

quantity of milk consumed but by only a small amount. In conclusion, milk has an inelastic

demand and a decrease in its price may lead to a slight increase in the quantity of milk consumed

by the consumers.

There are various policies and measures which can be used to help the Australian milk

farmers. Firstly, an introduction of price floor policy by the Australian government would help

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 5

the milk farmers. Price floors indicate the lowest possible legal price for selling a commodity

(Bilotkach 2014, p.231). Price floors would help the Australian milk farmers to at least recover

their production costs even if it will end up regulating the unregulated industry for the last two

decades. Secondly, the Australian government should come up with programs aimed at

establishing new cooperatives. For instance, in Australian, there are only a few major processors

like Murray Goulburn, Norco and Fonterra and more than 60% of the Australian dairy farmers

supply their milk to the two processors who have been accused of anti-competitive behavior

(Aghion et al 2015, p.1). Establishment of more cooperatives would intensify competition in the

Australian dairy milk processing and this will see fair prices being offered to milk farmers.

Thirdly, the Australian milk farmers should form their association and legally register it in order

to voice their problems in unity. This will enable them to gain market power and address their

problems strongly.

the milk farmers. Price floors indicate the lowest possible legal price for selling a commodity

(Bilotkach 2014, p.231). Price floors would help the Australian milk farmers to at least recover

their production costs even if it will end up regulating the unregulated industry for the last two

decades. Secondly, the Australian government should come up with programs aimed at

establishing new cooperatives. For instance, in Australian, there are only a few major processors

like Murray Goulburn, Norco and Fonterra and more than 60% of the Australian dairy farmers

supply their milk to the two processors who have been accused of anti-competitive behavior

(Aghion et al 2015, p.1). Establishment of more cooperatives would intensify competition in the

Australian dairy milk processing and this will see fair prices being offered to milk farmers.

Thirdly, the Australian milk farmers should form their association and legally register it in order

to voice their problems in unity. This will enable them to gain market power and address their

problems strongly.

QUESTION FOUR ESSAY 6

References

Aghion, P., Cai, J., Dewatripont, M., Du, L., Harrison, A. and Legros, P., 2015. Industrial policy

and competition. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(4), pp.1-32.

Azevedo, E.M. and Gottlieb, D., 2017. Perfect competition in markets with adverse

selection. Econometrica, 85(1), pp.67-105.

Bilotkach, V., 2014. Price Floors and Quality Choice. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(3),

pp.231-245.

Esteves, R.B. and Reggiani, C., 2014. Elasticity of demand and behaviour-based price

discrimination. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 32, pp.46-56.

Geroski, P.G. and Jacquemin, A., 2013. Barriers to entry and strategic competition. Routledge.

Lumantarna, E., Lam, N., Wilson, J. and Griffith, M., 2010. Inelastic displacement demand of

strength-degraded structures. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 14(4), pp.487-511.

Mas-Colell, A. ed., 2014. Noncooperative approaches to the theory of perfect competition (Vol.

3). Academic Press.

Mirman, L.J., Salgueiro, E. and Santugini, M., 2015. Learning: Perfectly Competitive Market.

Vlachos, A.G. and Biskas, P.N., 2013. Demand response in a real-time balancing market clearing

with pay-as-bid pricing. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 4(4), pp.1966-1975.

References

Aghion, P., Cai, J., Dewatripont, M., Du, L., Harrison, A. and Legros, P., 2015. Industrial policy

and competition. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(4), pp.1-32.

Azevedo, E.M. and Gottlieb, D., 2017. Perfect competition in markets with adverse

selection. Econometrica, 85(1), pp.67-105.

Bilotkach, V., 2014. Price Floors and Quality Choice. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(3),

pp.231-245.

Esteves, R.B. and Reggiani, C., 2014. Elasticity of demand and behaviour-based price

discrimination. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 32, pp.46-56.

Geroski, P.G. and Jacquemin, A., 2013. Barriers to entry and strategic competition. Routledge.

Lumantarna, E., Lam, N., Wilson, J. and Griffith, M., 2010. Inelastic displacement demand of

strength-degraded structures. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 14(4), pp.487-511.

Mas-Colell, A. ed., 2014. Noncooperative approaches to the theory of perfect competition (Vol.

3). Academic Press.

Mirman, L.J., Salgueiro, E. and Santugini, M., 2015. Learning: Perfectly Competitive Market.

Vlachos, A.G. and Biskas, P.N., 2013. Demand response in a real-time balancing market clearing

with pay-as-bid pricing. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 4(4), pp.1966-1975.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.