Evaluating Composite Materials for Railway Track Construction

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/29

|9

|1475

|136

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the application of composite materials in railway track construction as a replacement for conventional materials. It discusses various composite materials such as asphalt, carbon epoxy, glass epoxy, and fiber epoxy, highlighting their high strength and load-bearing capabilities. The report delves into the properties of concrete, epoxy, and nanocomposites, including metal matrix composites (MMCs), and their advantages over traditional materials. Mathematical formulas for calculating mechanical properties like compressive strength, tensile strength, hardness, shear modulus, and bulk modulus are presented. The thermal properties of these composites are also examined, with equations for calculating thermal conductivity based on density and reinforcement. Models such as the Maxwell model, Yu & Choi model, and Hamilton & Crosser model are discussed. The report includes a CAD analysis of a beam with different outer layer materials (CFRP/GFRP/Epoxy) to assess load-bearing capability, stress, and deflection, along with a weight comparison. The results indicate that beams with GFRP layers exhibit less deformation and lower weight, demonstrating the benefits of using composite materials in railway track design. This report is available on Desklib, where students can find a wealth of similar assignments and study resources.

Material

Conventional materials (combination of elastic) used to manufacture the railway track are

being replaced by different composite materials like asphalt, carbon epoxy, glass epoxy, fiber

epoxy etc. Railway track made from these materials are called as ballastless track. These

composite materials possess high strength and load bearing capability compared to

conventional materials. These composite materials sometimes are also called as metal matrix

composites (MMCs). MMCs are the combination of the base material and reinforced small

size particles. These small size particles are nothing but the metal in powder form. Sometimes

concrete with aggregates is also used to make these ballastless.

Concrete

Concrete is generally made from Portland cement, aggregates, admixtures etc. Mostly utilized

cement is Portland cement which is made of silica, iron oxide, lime and alumina. Proportion

of these contents should be in accurate proportion otherwise it may result in disintegration of

cement. Some natural aggregates which come in concrete are basalt, granite etc. These

aggregates should be clean, inert & durable and should not have silica as availability of silica

may result in disintegration as stated above.

Epoxy

Epoxy is the end products of epoxy resins, these epoxy resins are also called as monomers or

prepolymers. Epoxy can be classified in various categories depending upon the type of

composite or material reinforced. They can be classified as carbon epoxy, glass epoxy fiber

epoxy etc. They can also be named as GFRP (glass fiber reinforced polymer), CFRP (carbon

fiber reinforced polymer) etc.

Nanocomposites

Some other nanocomposites can also be utilized to make ballastless track. These

nanocomposites are the powder of solid metal reinforced into the base material which also is

a metal. These nanocomposites can be aluminium oxide (Al2O3), silicon carbide (SiC), boron

carbide (B4C) etc. Advantages of these nanocomposites are that they are lighter in weight

compared with conventional materials like steel or iron. These nanocomposites have higher

mechanical, thermal and physical properties when compared with conventional materials

(Hangai, 2015; Jinnapat and Kennedy, 2011; Koizumi et al, 2011; Turan et al, 2012).

Mechanical properties of the materials

Table below shows some mathematical formulas to calculate some important properties like,

compressive strength, tensile strength, hardness, shear modulus and bulk modulus etc. These

all are the mechanical properties of the material. In the below mathematical formulas

subscript ‘s’ is for the base material while composite or reinforced material properties are

without any subscript.

Conventional materials (combination of elastic) used to manufacture the railway track are

being replaced by different composite materials like asphalt, carbon epoxy, glass epoxy, fiber

epoxy etc. Railway track made from these materials are called as ballastless track. These

composite materials possess high strength and load bearing capability compared to

conventional materials. These composite materials sometimes are also called as metal matrix

composites (MMCs). MMCs are the combination of the base material and reinforced small

size particles. These small size particles are nothing but the metal in powder form. Sometimes

concrete with aggregates is also used to make these ballastless.

Concrete

Concrete is generally made from Portland cement, aggregates, admixtures etc. Mostly utilized

cement is Portland cement which is made of silica, iron oxide, lime and alumina. Proportion

of these contents should be in accurate proportion otherwise it may result in disintegration of

cement. Some natural aggregates which come in concrete are basalt, granite etc. These

aggregates should be clean, inert & durable and should not have silica as availability of silica

may result in disintegration as stated above.

Epoxy

Epoxy is the end products of epoxy resins, these epoxy resins are also called as monomers or

prepolymers. Epoxy can be classified in various categories depending upon the type of

composite or material reinforced. They can be classified as carbon epoxy, glass epoxy fiber

epoxy etc. They can also be named as GFRP (glass fiber reinforced polymer), CFRP (carbon

fiber reinforced polymer) etc.

Nanocomposites

Some other nanocomposites can also be utilized to make ballastless track. These

nanocomposites are the powder of solid metal reinforced into the base material which also is

a metal. These nanocomposites can be aluminium oxide (Al2O3), silicon carbide (SiC), boron

carbide (B4C) etc. Advantages of these nanocomposites are that they are lighter in weight

compared with conventional materials like steel or iron. These nanocomposites have higher

mechanical, thermal and physical properties when compared with conventional materials

(Hangai, 2015; Jinnapat and Kennedy, 2011; Koizumi et al, 2011; Turan et al, 2012).

Mechanical properties of the materials

Table below shows some mathematical formulas to calculate some important properties like,

compressive strength, tensile strength, hardness, shear modulus and bulk modulus etc. These

all are the mechanical properties of the material. In the below mathematical formulas

subscript ‘s’ is for the base material while composite or reinforced material properties are

without any subscript.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Properties Open-cell type foam

Compressive strength σ c= ( 0.1−1.0 ) σ c ,s ( ρ

ρs ) 3

2

Tensile strength σ t ≈ ( 1.1−1.4 ) σ c

Bulk Modulus K ≈ 1.1 E

Shear Modulus G ≈ 3

8 E

Hardness H=σc (1+2 ρ

ρs )

Thermal properties of materials

Similar to mechanical properties thermal properties of these composite can also be calculated

using mathematical equation. They can be measured in two ways. In one way it can be

measured using density of the base material while in second way it can be measured for the

amount of composite reinforced into the base material using mathematical equations given by

well-known researchers (Garcia-Moreno et al, 2011; Granitzer and Rumpf, 2010; Güner,

Arıkan and Nebioglu, 2015)

In terms of density

In terms of density thermal properties can be using the mathematical equation given below

as,

k =k s ( ρ

ρs )q

In terms of reinforcement

There are wide verities of models given by researchers around the globe to calculate the

thermal properties of composite, but some well-known mathematical formulas are Hamilton

& Crosser model, Yu & Choi model, Maxwell model etc (Depczynski et al, 2016; Duarte and

Ferreira, 2016; Garcia-Avila and Rabiei, 2011; Kosti, 2014; Kosti and Malvi, 2018)

Maxwell model

k N =

[ ( k p +2 k s ) +2 ϕ ( k p−k s )

( k p +2 ks ) −ϕ ( k p−ks ) ] ks

Yu & Choi model

k N =

[ ( ke +2 ks ) +2 ϕ ( k e−ks ) ( 1+ β ) 3

( ke+2 k s ) −ϕ ( ke−k s ) ( 1+ β ) 3 ] k s

Compressive strength σ c= ( 0.1−1.0 ) σ c ,s ( ρ

ρs ) 3

2

Tensile strength σ t ≈ ( 1.1−1.4 ) σ c

Bulk Modulus K ≈ 1.1 E

Shear Modulus G ≈ 3

8 E

Hardness H=σc (1+2 ρ

ρs )

Thermal properties of materials

Similar to mechanical properties thermal properties of these composite can also be calculated

using mathematical equation. They can be measured in two ways. In one way it can be

measured using density of the base material while in second way it can be measured for the

amount of composite reinforced into the base material using mathematical equations given by

well-known researchers (Garcia-Moreno et al, 2011; Granitzer and Rumpf, 2010; Güner,

Arıkan and Nebioglu, 2015)

In terms of density

In terms of density thermal properties can be using the mathematical equation given below

as,

k =k s ( ρ

ρs )q

In terms of reinforcement

There are wide verities of models given by researchers around the globe to calculate the

thermal properties of composite, but some well-known mathematical formulas are Hamilton

& Crosser model, Yu & Choi model, Maxwell model etc (Depczynski et al, 2016; Duarte and

Ferreira, 2016; Garcia-Avila and Rabiei, 2011; Kosti, 2014; Kosti and Malvi, 2018)

Maxwell model

k N =

[ ( k p +2 k s ) +2 ϕ ( k p−k s )

( k p +2 ks ) −ϕ ( k p−ks ) ] ks

Yu & Choi model

k N =

[ ( ke +2 ks ) +2 ϕ ( k e−ks ) ( 1+ β ) 3

( ke+2 k s ) −ϕ ( ke−k s ) ( 1+ β ) 3 ] k s

Hamilton & Crosser model

k N =

[ k p + ( n−1 ) ks + ( n−1 ) ( k p−ks ) ϕ

k p + ( n−1 ) k s− ( k p −k s ) ϕ ] ks

Where:

k Thermal conductivity

ϕ Amount of composite reinforced

p and s Composite and solid metal

β It is the thickness to radius ratio of composite

n Shape factor

Composite K (W/m-K) Cp (J/kg-K) ρ (kg/m3)

B4C 42 1288 2550

Al2O3 36 773 3880

SiC 100 1300 3200

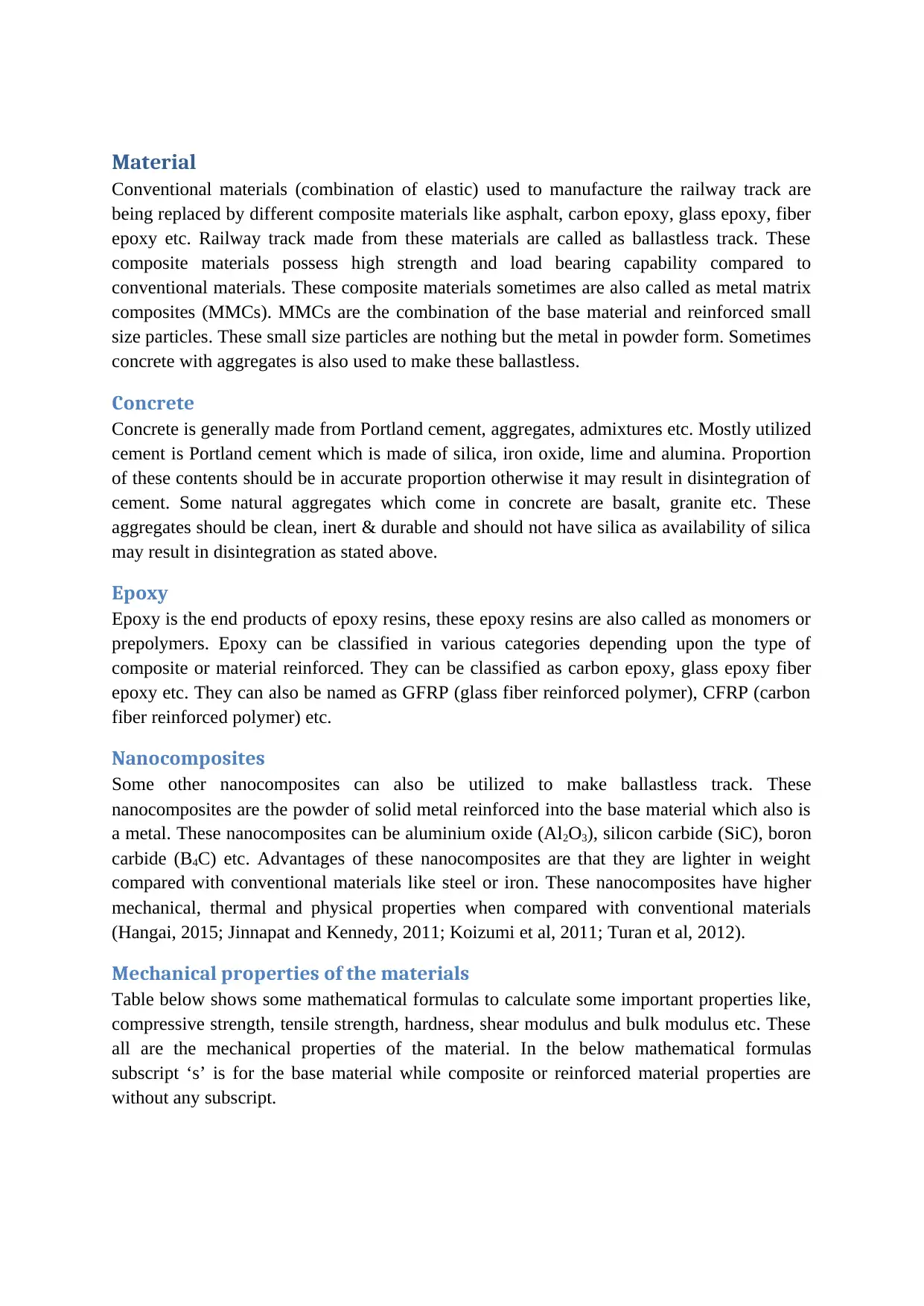

Analyse of materials

These composite materials can deviates the thermal properties. Figure 1 shows the variation

of compressive strength for some composite materials.

Figure 1 Compressive strength for different composite materials.

k N =

[ k p + ( n−1 ) ks + ( n−1 ) ( k p−ks ) ϕ

k p + ( n−1 ) k s− ( k p −k s ) ϕ ] ks

Where:

k Thermal conductivity

ϕ Amount of composite reinforced

p and s Composite and solid metal

β It is the thickness to radius ratio of composite

n Shape factor

Composite K (W/m-K) Cp (J/kg-K) ρ (kg/m3)

B4C 42 1288 2550

Al2O3 36 773 3880

SiC 100 1300 3200

Analyse of materials

These composite materials can deviates the thermal properties. Figure 1 shows the variation

of compressive strength for some composite materials.

Figure 1 Compressive strength for different composite materials.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

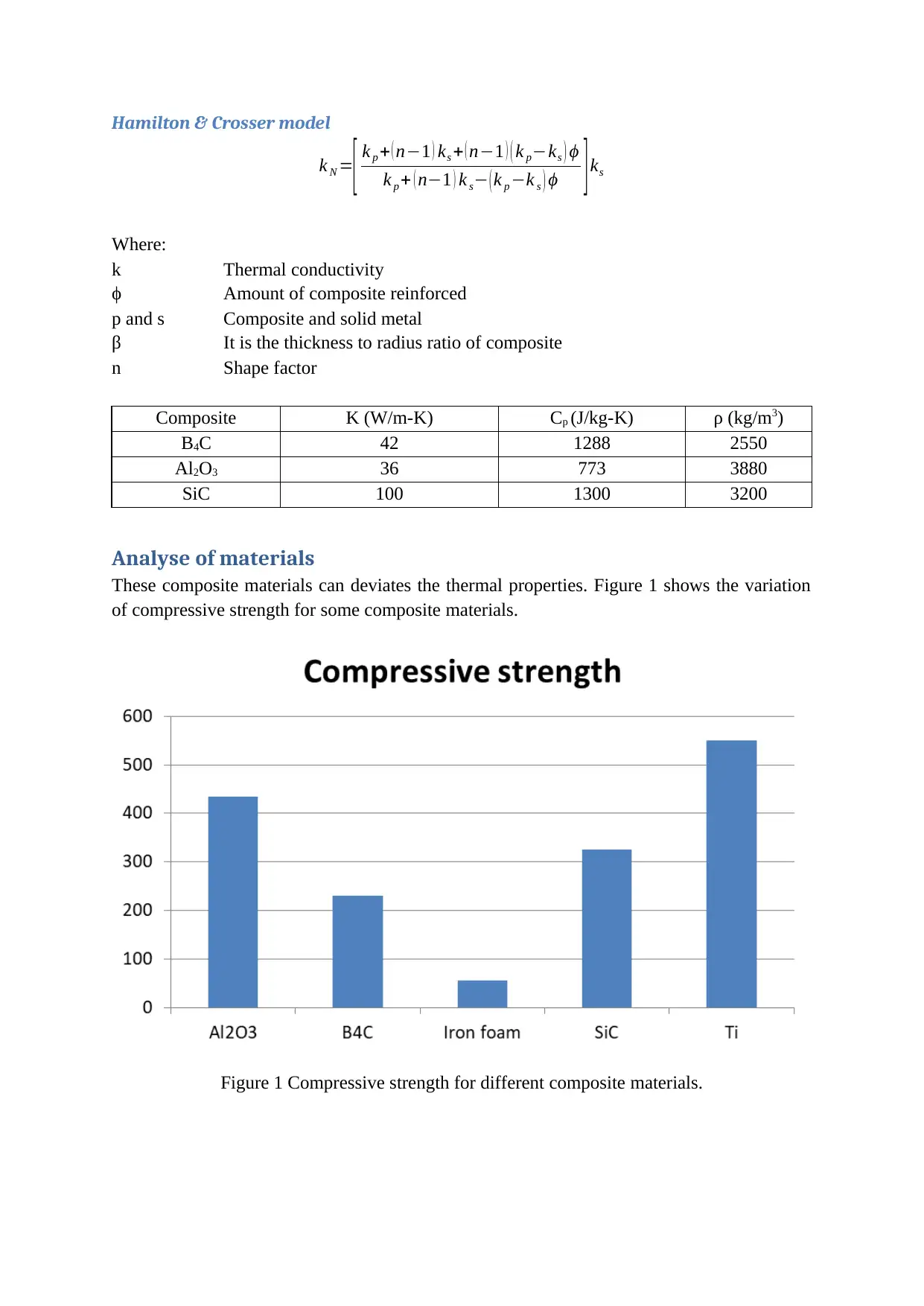

Figure 2 shows the variation of hardness for some composite materials.

Figure 2 Hardness for different composite materials.

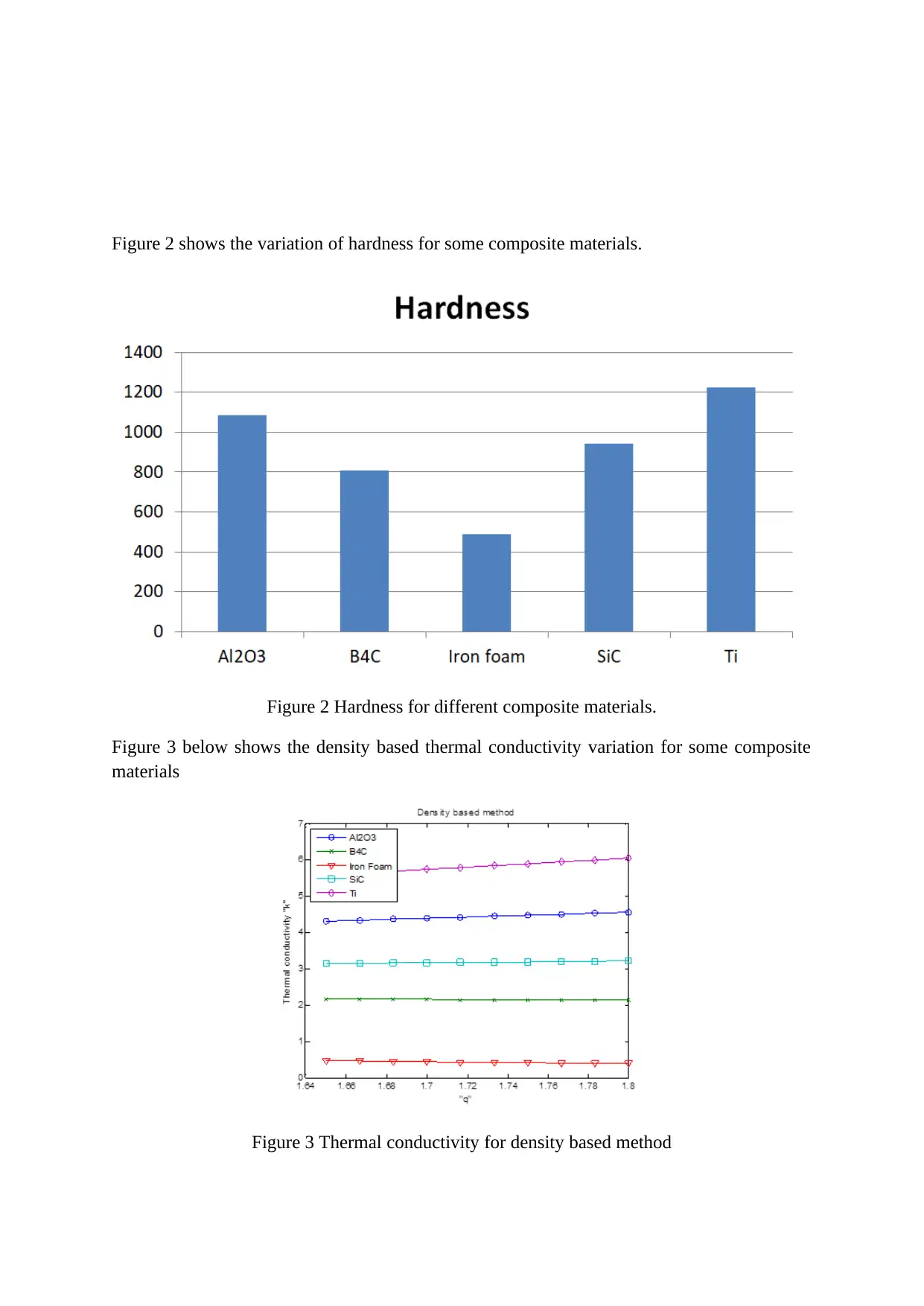

Figure 3 below shows the density based thermal conductivity variation for some composite

materials

Figure 3 Thermal conductivity for density based method

Figure 2 Hardness for different composite materials.

Figure 3 below shows the density based thermal conductivity variation for some composite

materials

Figure 3 Thermal conductivity for density based method

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

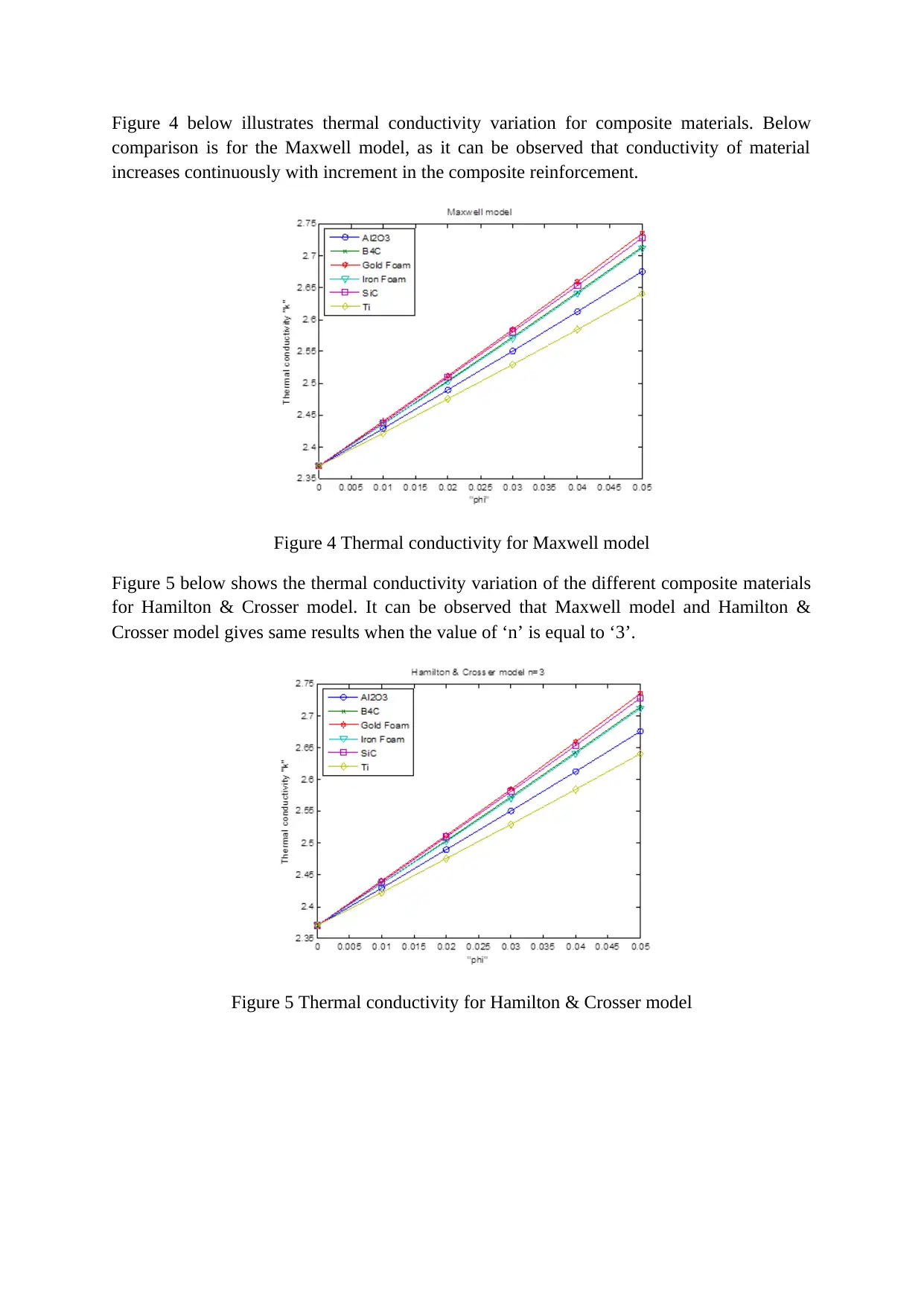

Figure 4 below illustrates thermal conductivity variation for composite materials. Below

comparison is for the Maxwell model, as it can be observed that conductivity of material

increases continuously with increment in the composite reinforcement.

Figure 4 Thermal conductivity for Maxwell model

Figure 5 below shows the thermal conductivity variation of the different composite materials

for Hamilton & Crosser model. It can be observed that Maxwell model and Hamilton &

Crosser model gives same results when the value of ‘n’ is equal to ‘3’.

Figure 5 Thermal conductivity for Hamilton & Crosser model

comparison is for the Maxwell model, as it can be observed that conductivity of material

increases continuously with increment in the composite reinforcement.

Figure 4 Thermal conductivity for Maxwell model

Figure 5 below shows the thermal conductivity variation of the different composite materials

for Hamilton & Crosser model. It can be observed that Maxwell model and Hamilton &

Crosser model gives same results when the value of ‘n’ is equal to ‘3’.

Figure 5 Thermal conductivity for Hamilton & Crosser model

CAD (computer aided drawing) analysis

To analyse the effect of these composite a beam is considered as shown in figure. To analyse

a student version software of ANSYS or SolidWorks can be utilized

Figure 6 Geometry of the beam with upper and inside layer of different material

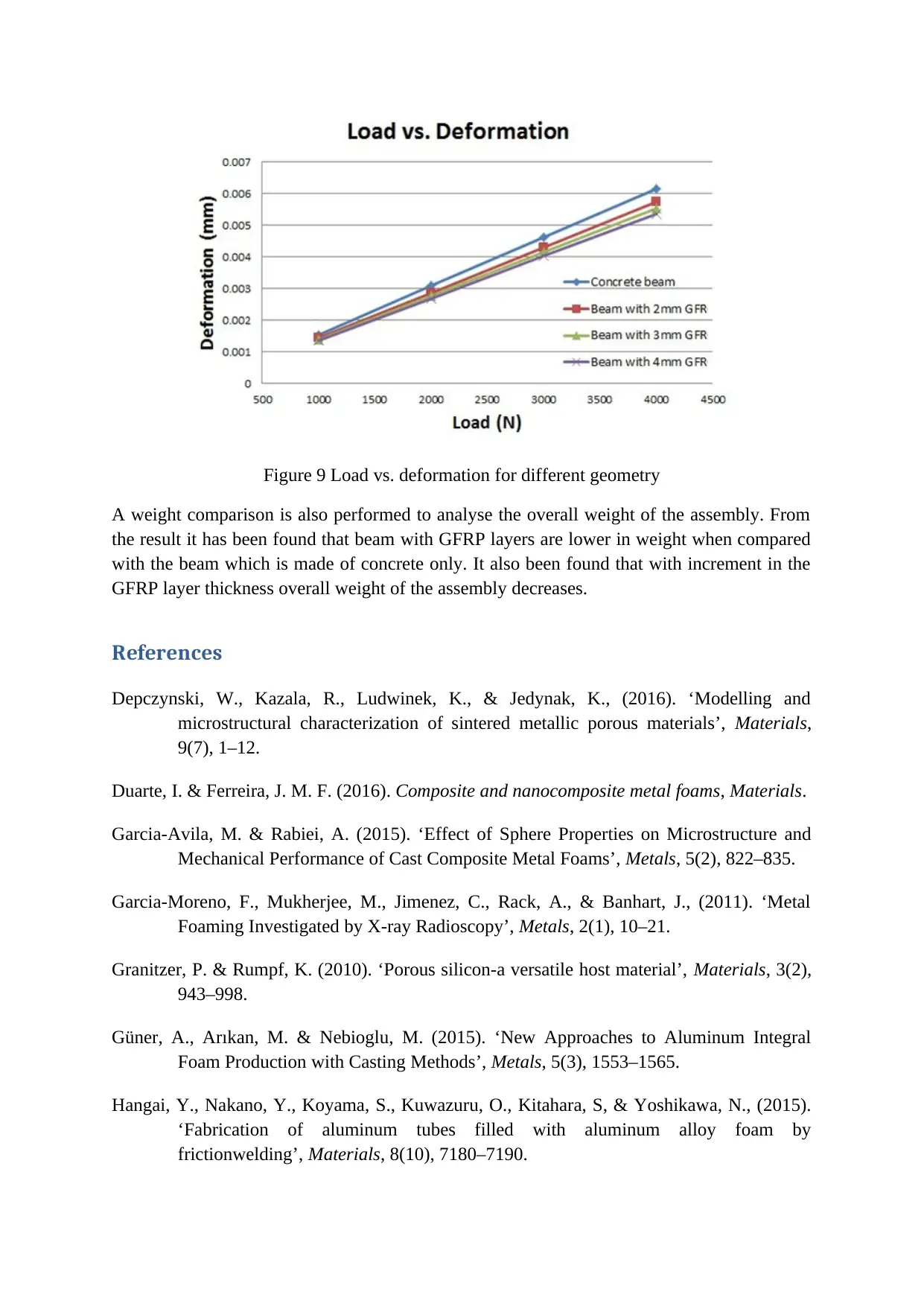

Above figure have two parts outer layer and inside layer. Inside layer is considered to be

made of same material (concrete) while material of the outer layer is changed

(CFRP/GFRP/Epoxy) to analyse its effect on the load bearing capability, stress and deflection

generation. Below figure shows the front view of the geometry to clearly illustrate the drawn

geometry. Thickness of the outer layer is also changed to analyse the effect of FRP material.

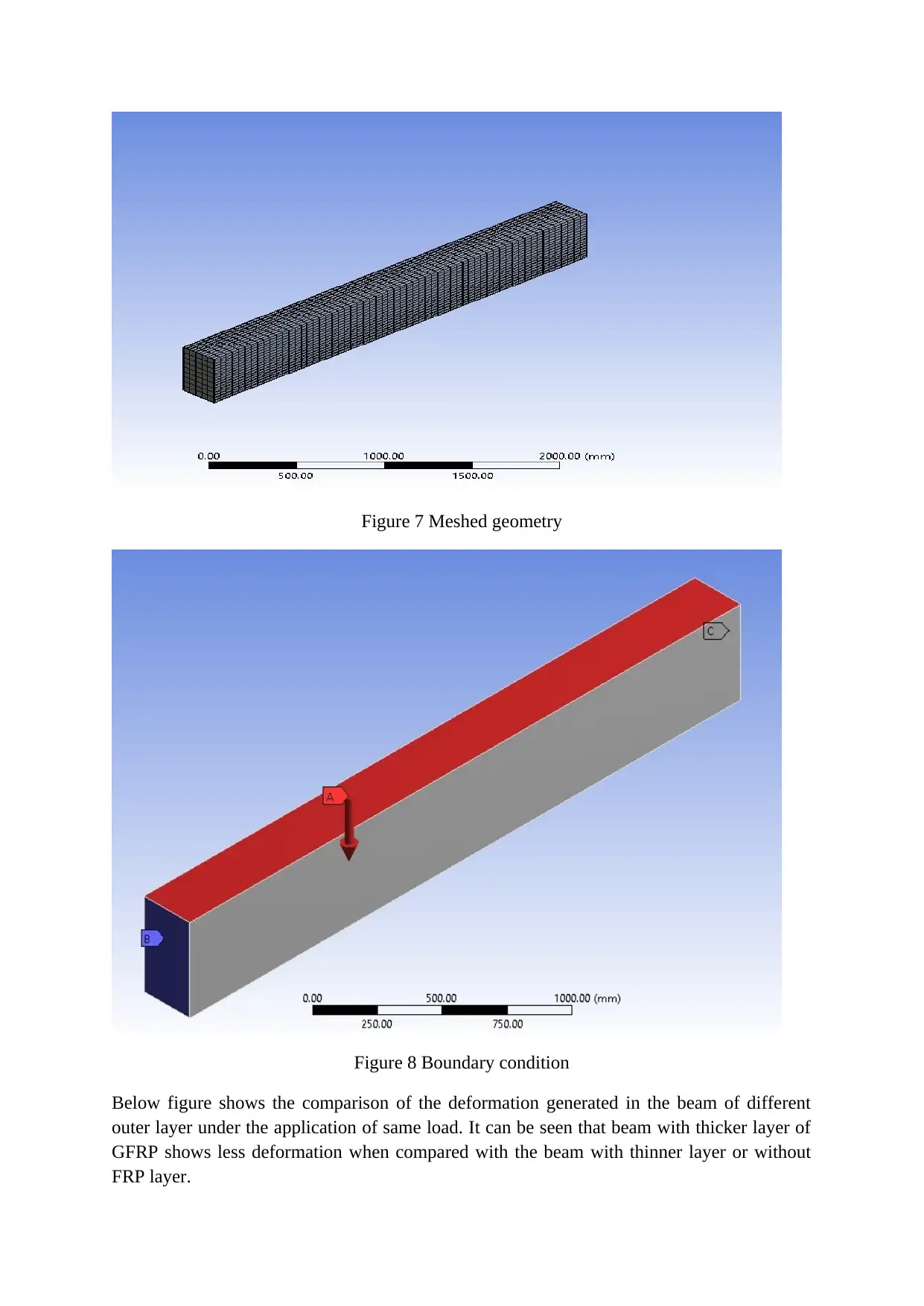

Above geometry is first meshed and a simple face load is applied on the face of the beam.

Below figures shows the meshed geometry and loaded beam.

To analyse the effect of these composite a beam is considered as shown in figure. To analyse

a student version software of ANSYS or SolidWorks can be utilized

Figure 6 Geometry of the beam with upper and inside layer of different material

Above figure have two parts outer layer and inside layer. Inside layer is considered to be

made of same material (concrete) while material of the outer layer is changed

(CFRP/GFRP/Epoxy) to analyse its effect on the load bearing capability, stress and deflection

generation. Below figure shows the front view of the geometry to clearly illustrate the drawn

geometry. Thickness of the outer layer is also changed to analyse the effect of FRP material.

Above geometry is first meshed and a simple face load is applied on the face of the beam.

Below figures shows the meshed geometry and loaded beam.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure 7 Meshed geometry

Figure 8 Boundary condition

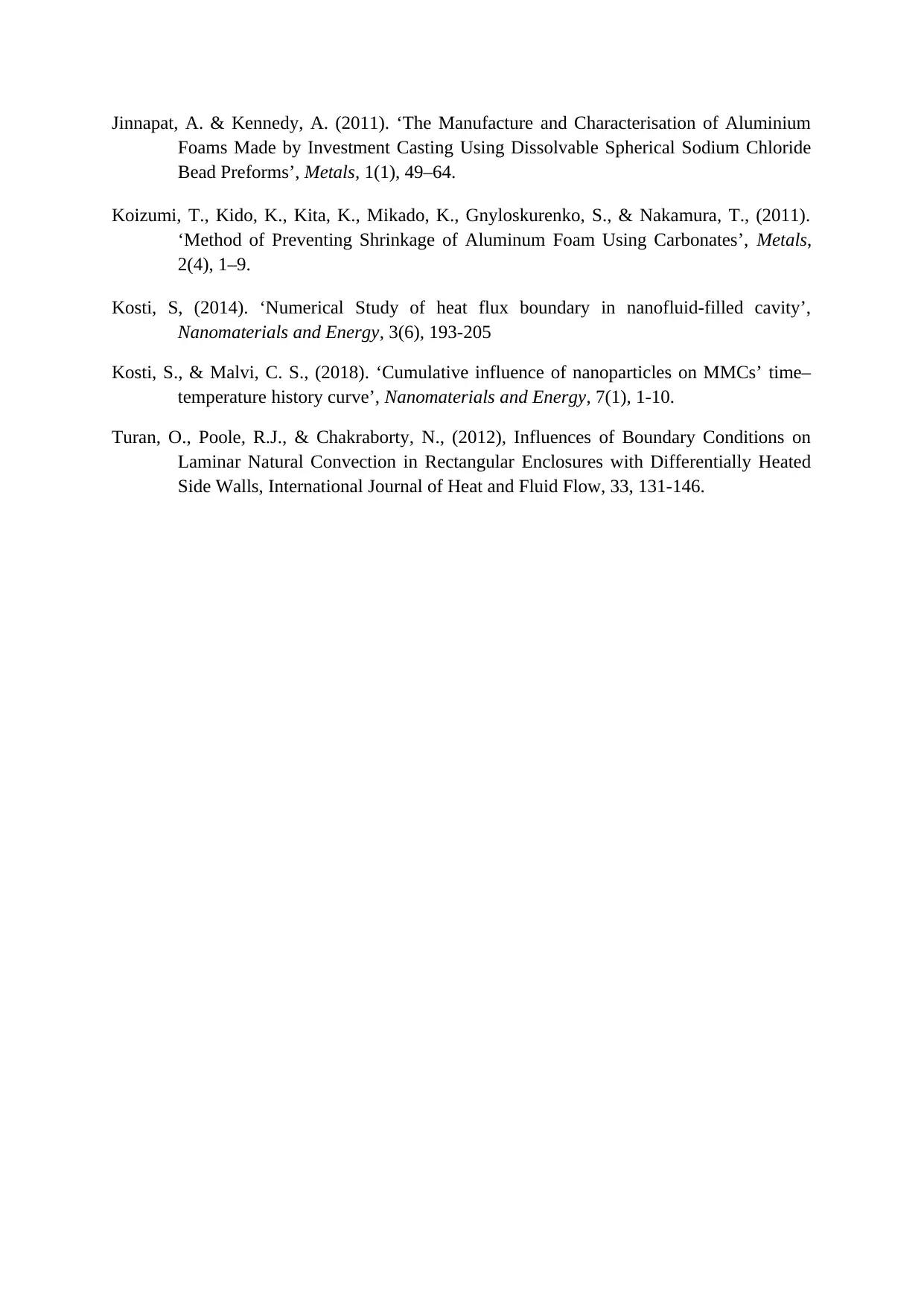

Below figure shows the comparison of the deformation generated in the beam of different

outer layer under the application of same load. It can be seen that beam with thicker layer of

GFRP shows less deformation when compared with the beam with thinner layer or without

FRP layer.

Figure 8 Boundary condition

Below figure shows the comparison of the deformation generated in the beam of different

outer layer under the application of same load. It can be seen that beam with thicker layer of

GFRP shows less deformation when compared with the beam with thinner layer or without

FRP layer.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Figure 9 Load vs. deformation for different geometry

A weight comparison is also performed to analyse the overall weight of the assembly. From

the result it has been found that beam with GFRP layers are lower in weight when compared

with the beam which is made of concrete only. It also been found that with increment in the

GFRP layer thickness overall weight of the assembly decreases.

References

Depczynski, W., Kazala, R., Ludwinek, K., & Jedynak, K., (2016). ‘Modelling and

microstructural characterization of sintered metallic porous materials’, Materials,

9(7), 1–12.

Duarte, I. & Ferreira, J. M. F. (2016). Composite and nanocomposite metal foams, Materials.

Garcia-Avila, M. & Rabiei, A. (2015). ‘Effect of Sphere Properties on Microstructure and

Mechanical Performance of Cast Composite Metal Foams’, Metals, 5(2), 822–835.

Garcia-Moreno, F., Mukherjee, M., Jimenez, C., Rack, A., & Banhart, J., (2011). ‘Metal

Foaming Investigated by X-ray Radioscopy’, Metals, 2(1), 10–21.

Granitzer, P. & Rumpf, K. (2010). ‘Porous silicon-a versatile host material’, Materials, 3(2),

943–998.

Güner, A., Arıkan, M. & Nebioglu, M. (2015). ‘New Approaches to Aluminum Integral

Foam Production with Casting Methods’, Metals, 5(3), 1553–1565.

Hangai, Y., Nakano, Y., Koyama, S., Kuwazuru, O., Kitahara, S, & Yoshikawa, N., (2015).

‘Fabrication of aluminum tubes filled with aluminum alloy foam by

frictionwelding’, Materials, 8(10), 7180–7190.

A weight comparison is also performed to analyse the overall weight of the assembly. From

the result it has been found that beam with GFRP layers are lower in weight when compared

with the beam which is made of concrete only. It also been found that with increment in the

GFRP layer thickness overall weight of the assembly decreases.

References

Depczynski, W., Kazala, R., Ludwinek, K., & Jedynak, K., (2016). ‘Modelling and

microstructural characterization of sintered metallic porous materials’, Materials,

9(7), 1–12.

Duarte, I. & Ferreira, J. M. F. (2016). Composite and nanocomposite metal foams, Materials.

Garcia-Avila, M. & Rabiei, A. (2015). ‘Effect of Sphere Properties on Microstructure and

Mechanical Performance of Cast Composite Metal Foams’, Metals, 5(2), 822–835.

Garcia-Moreno, F., Mukherjee, M., Jimenez, C., Rack, A., & Banhart, J., (2011). ‘Metal

Foaming Investigated by X-ray Radioscopy’, Metals, 2(1), 10–21.

Granitzer, P. & Rumpf, K. (2010). ‘Porous silicon-a versatile host material’, Materials, 3(2),

943–998.

Güner, A., Arıkan, M. & Nebioglu, M. (2015). ‘New Approaches to Aluminum Integral

Foam Production with Casting Methods’, Metals, 5(3), 1553–1565.

Hangai, Y., Nakano, Y., Koyama, S., Kuwazuru, O., Kitahara, S, & Yoshikawa, N., (2015).

‘Fabrication of aluminum tubes filled with aluminum alloy foam by

frictionwelding’, Materials, 8(10), 7180–7190.

Jinnapat, A. & Kennedy, A. (2011). ‘The Manufacture and Characterisation of Aluminium

Foams Made by Investment Casting Using Dissolvable Spherical Sodium Chloride

Bead Preforms’, Metals, 1(1), 49–64.

Koizumi, T., Kido, K., Kita, K., Mikado, K., Gnyloskurenko, S., & Nakamura, T., (2011).

‘Method of Preventing Shrinkage of Aluminum Foam Using Carbonates’, Metals,

2(4), 1–9.

Kosti, S, (2014). ‘Numerical Study of heat flux boundary in nanofluid-filled cavity’,

Nanomaterials and Energy, 3(6), 193-205

Kosti, S., & Malvi, C. S., (2018). ‘Cumulative influence of nanoparticles on MMCs’ time–

temperature history curve’, Nanomaterials and Energy, 7(1), 1-10.

Turan, O., Poole, R.J., & Chakraborty, N., (2012), Influences of Boundary Conditions on

Laminar Natural Convection in Rectangular Enclosures with Differentially Heated

Side Walls, International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 33, 131-146.

Foams Made by Investment Casting Using Dissolvable Spherical Sodium Chloride

Bead Preforms’, Metals, 1(1), 49–64.

Koizumi, T., Kido, K., Kita, K., Mikado, K., Gnyloskurenko, S., & Nakamura, T., (2011).

‘Method of Preventing Shrinkage of Aluminum Foam Using Carbonates’, Metals,

2(4), 1–9.

Kosti, S, (2014). ‘Numerical Study of heat flux boundary in nanofluid-filled cavity’,

Nanomaterials and Energy, 3(6), 193-205

Kosti, S., & Malvi, C. S., (2018). ‘Cumulative influence of nanoparticles on MMCs’ time–

temperature history curve’, Nanomaterials and Energy, 7(1), 1-10.

Turan, O., Poole, R.J., & Chakraborty, N., (2012), Influences of Boundary Conditions on

Laminar Natural Convection in Rectangular Enclosures with Differentially Heated

Side Walls, International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 33, 131-146.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.