Literature Review: A Conceptual Framework for Tourism in Mountains

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|22

|11653

|57

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review delves into a conceptual framework designed to address tourism and recreation in mountainous regions. It begins by outlining six mountain-specific resource characteristics: diversity, marginality, difficulty of access, fragility, niche, and aesthetics, arguing that these unique features significantly impact mountain recreation and tourism development. The review then examines the evolving landscape of recreation and tourism in mountains, particularly the increasing demand from local recreationists, tourists, and amenity migrants, and the implications for planning and management. A three-class system of recreation and tourism land-use settings—nodal center, frontcountry, and backcountry—is proposed to resolve the challenges arising from the diverse needs of these users. The framework emphasizes that effective tourism planning and management in mountainous regions must consider and integrate these mountain-specific resource characteristics. Ultimately, the review posits that this framework not only fosters an integrated perspective on mountain tourism planning and management but also propels research in areas concerning mountain resource characteristics, amenity users, and recreational zoning.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235953348

Mountain Tourism: Toward a Conceptual Framework

Data in Tourism Geographies · August 2005

DOI: 10.1080/14616680500164849

CITATIONS

79

READS

1,712

2 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Cultural and Social Capital, and Natural Disasters in Tourism-dependent Communities in AsiaView project

Sanjay Nepal

University of Waterloo

75 PUBLICATIONS 2,283 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sanjay Nepal on 31 May 2014.

Mountain Tourism: Toward a Conceptual Framework

Data in Tourism Geographies · August 2005

DOI: 10.1080/14616680500164849

CITATIONS

79

READS

1,712

2 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Cultural and Social Capital, and Natural Disasters in Tourism-dependent Communities in AsiaView project

Sanjay Nepal

University of Waterloo

75 PUBLICATIONS 2,283 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sanjay Nepal on 31 May 2014.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Tourism Geographies

Vol. 7, No. 3, 313–333, 2005

Mountain Tourism: Toward a Conceptual

Framework

SANJAY K. NEPAL∗ & RAYMOND CHIPENIUK∗∗

∗Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences, Texas A&M University, USA

∗∗School of Environmental Planning, University of Northern British Columbia, Canada

ABSTRACT A conceptual framework is proposed to examine tourism and recreation issues

in mountainous regions. First, six mountain-specific resource characteristics are discussed,

which include diversity, marginality, difficulty of access, fragility, niche and aesthetics. It is

argued that these characteristics are unique to mountainous regions and, as such, have specific

implications for mountain recreation and tourism development. The paper then examines the

changing nature of recreation and tourism use in the mountains, especially increasing levels of

recreation and tourism activities sought by local recreationists, tourists and amenity migrants,

and the implications of these activities for mountain tourism planning and management. A

three-class system of recreation and tourism land-use settings is proposed to resolve planning

and management challenges associated with increasingly diverse needs of these users. Tourism

planning and management in mountainous regions should consider and incorporate mountain-

specific resource characteristics. It is argued that the proposed framework not only assists in

developing an integrated perspective on mountain tourism planning and management but also

advances research fronts in areas of mountain resource characteristics, mountain amenity users

and mountain recreational zoning.

KEY WORDS: Mountain tourism, mountain resource characteristics, outdoor recreation,

tourism, amenity migration, recreation and tourism land use

Introduction

There has been a slow but steady effort towards increasing global awareness concern-

ing mountain issues. In recent years, mountain issues have come to the forefront in the

policy agenda of many national and international agencies and governments (Godde

et al. 2000). As a unified response to increasing global awareness of mountains and

tourism issues, the year 2002 was declared the International Year of the Mountains

and also the International Year of Ecotourism.

Mountains, with their spectacular scenery, majestic beauty and unique amenity val-

ues, are one of the most popular destinations for tourists. The development of tourism

Correspondence Address: Sanjay K. Nepal, Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences, Texas

A&M University, 2261 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-2261, USA. Fax:+979 845 0446; Tel.: +979

862 4080; Email: sknepal@tamu.edu

ISSN 1461-6688 Print/1470-1340 Online /05/03/00313–21 C 2005 Taylor & Francis Group Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/14616680500164849

Vol. 7, No. 3, 313–333, 2005

Mountain Tourism: Toward a Conceptual

Framework

SANJAY K. NEPAL∗ & RAYMOND CHIPENIUK∗∗

∗Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences, Texas A&M University, USA

∗∗School of Environmental Planning, University of Northern British Columbia, Canada

ABSTRACT A conceptual framework is proposed to examine tourism and recreation issues

in mountainous regions. First, six mountain-specific resource characteristics are discussed,

which include diversity, marginality, difficulty of access, fragility, niche and aesthetics. It is

argued that these characteristics are unique to mountainous regions and, as such, have specific

implications for mountain recreation and tourism development. The paper then examines the

changing nature of recreation and tourism use in the mountains, especially increasing levels of

recreation and tourism activities sought by local recreationists, tourists and amenity migrants,

and the implications of these activities for mountain tourism planning and management. A

three-class system of recreation and tourism land-use settings is proposed to resolve planning

and management challenges associated with increasingly diverse needs of these users. Tourism

planning and management in mountainous regions should consider and incorporate mountain-

specific resource characteristics. It is argued that the proposed framework not only assists in

developing an integrated perspective on mountain tourism planning and management but also

advances research fronts in areas of mountain resource characteristics, mountain amenity users

and mountain recreational zoning.

KEY WORDS: Mountain tourism, mountain resource characteristics, outdoor recreation,

tourism, amenity migration, recreation and tourism land use

Introduction

There has been a slow but steady effort towards increasing global awareness concern-

ing mountain issues. In recent years, mountain issues have come to the forefront in the

policy agenda of many national and international agencies and governments (Godde

et al. 2000). As a unified response to increasing global awareness of mountains and

tourism issues, the year 2002 was declared the International Year of the Mountains

and also the International Year of Ecotourism.

Mountains, with their spectacular scenery, majestic beauty and unique amenity val-

ues, are one of the most popular destinations for tourists. The development of tourism

Correspondence Address: Sanjay K. Nepal, Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences, Texas

A&M University, 2261 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-2261, USA. Fax:+979 845 0446; Tel.: +979

862 4080; Email: sknepal@tamu.edu

ISSN 1461-6688 Print/1470-1340 Online /05/03/00313–21 C 2005 Taylor & Francis Group Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/14616680500164849

314 S. K. Nepal & R. Chipeniuk

in the mountains can be a key factor in the focal concern for overall improvement

in people’s quality of life through sustainable economic development initiatives and

environmental conservation. In socio-economic and environmental terms, tourism in

mountain regions is a mixed blessing: it can be a source of problems, but it also offers

many opportunities.

Mountain regions, in most cases, are inaccessible, fragile, marginal to political

and economic decision-making and home to some of the poorest people in the world

(Messerli and Ives 1997). While steepness, fragility and marginality are often con-

straints, exposing mountains to pervasive degradation, some of these attributes may

also attract the ‘adventure tourists’. Tourism development is an obvious means for

achieving sustainable mountain development, particularly where other economic re-

sources necessary for development are limited.

Until very recently, tourism studies concerned with mountain landscapes were

mainly limited to physical, ecological and environmental processes (Smethurst 2000).

Recent discussions on The Mountain Forum – an online forum which facilitates the

discussion of mountain-specific development issues at an international level, more

recent issues of the Mountain Research and Development – an international journal

devoted to mountain-specific issues, and recent publications with a mountain theme

(see Allan et al. 1988; Allan 1995; Messerli and Ives 1997; Funnell and Parish 2001)

all indicate a gradual shift in emphasis from the physical to the policy and devel-

opment arenas. A tourism perspective on mountain development policies, within the

broader framework of human–nature interactions in mountain environments, is now

essential. However, although mountains have often been places to visit for recreation

and tourism, and although interest in the development of mountain tourism has in-

tensified in many countries, hardly any attempts have been made to conceptualize

mountain tourism, unlike seaside or coastal tourism (Wong 1993; Orams 1998). It is

somewhat perplexing that even The Encyclopedia of Tourism (Jafari 2003) does not

make any reference to mountain tourism, mentioning only ‘mountaineering’. How-

ever, this situation is gradually improving, as more researchers become interested in

mountain tourism issues (Price et al. 1997; Godde et al. 2000; Beedie and Hudson

2003; Nepal 2000, 2003).

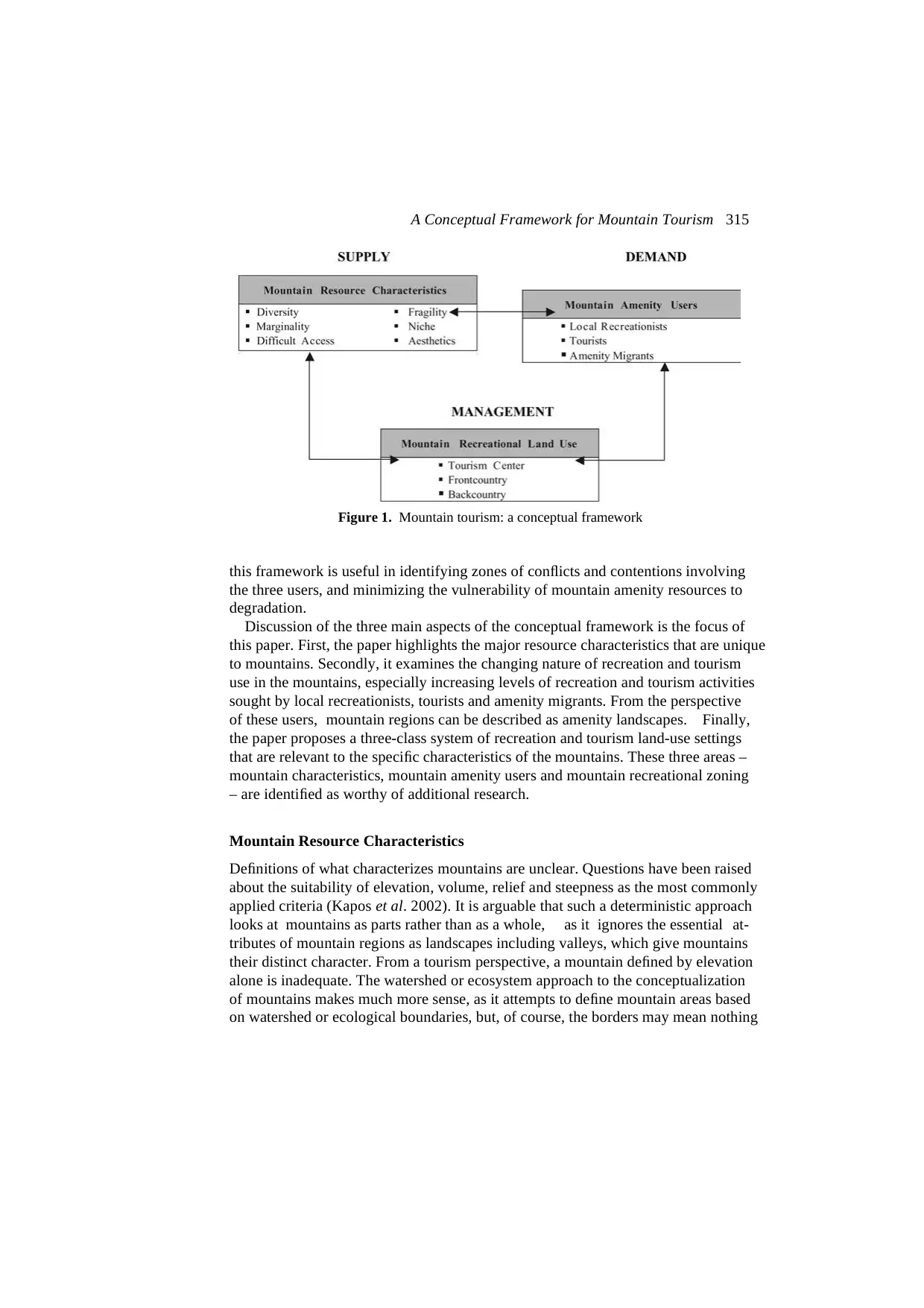

This paper proposes a conceptual framework to examine recreation and tourism is-

sues in mountainous regions. This framework views the planning and management of

mountain amenity landscapes as essentially issues about supply, demand and manage-

ment (Figure 1). Within this framework, the supply of recreational opportunities in a

mountainous region is seen as influenced by its six resource characteristics: diversity,

marginality, difficult access, fragility, niche and aesthetics. The demand for recre-

ational activities is conceived as an outcome of the combined influences of the three

principal users: the local recreationists, the tourists and the amenity migrants. The

management of the supply and demand of mountain recreational opportunities can be

achieved best through a land-use zonation concept, which divides mountain amenity

landscapes into a nodal centre, a ‘frontcountry’ and a ‘backcountry’. It is argued that

in the mountains can be a key factor in the focal concern for overall improvement

in people’s quality of life through sustainable economic development initiatives and

environmental conservation. In socio-economic and environmental terms, tourism in

mountain regions is a mixed blessing: it can be a source of problems, but it also offers

many opportunities.

Mountain regions, in most cases, are inaccessible, fragile, marginal to political

and economic decision-making and home to some of the poorest people in the world

(Messerli and Ives 1997). While steepness, fragility and marginality are often con-

straints, exposing mountains to pervasive degradation, some of these attributes may

also attract the ‘adventure tourists’. Tourism development is an obvious means for

achieving sustainable mountain development, particularly where other economic re-

sources necessary for development are limited.

Until very recently, tourism studies concerned with mountain landscapes were

mainly limited to physical, ecological and environmental processes (Smethurst 2000).

Recent discussions on The Mountain Forum – an online forum which facilitates the

discussion of mountain-specific development issues at an international level, more

recent issues of the Mountain Research and Development – an international journal

devoted to mountain-specific issues, and recent publications with a mountain theme

(see Allan et al. 1988; Allan 1995; Messerli and Ives 1997; Funnell and Parish 2001)

all indicate a gradual shift in emphasis from the physical to the policy and devel-

opment arenas. A tourism perspective on mountain development policies, within the

broader framework of human–nature interactions in mountain environments, is now

essential. However, although mountains have often been places to visit for recreation

and tourism, and although interest in the development of mountain tourism has in-

tensified in many countries, hardly any attempts have been made to conceptualize

mountain tourism, unlike seaside or coastal tourism (Wong 1993; Orams 1998). It is

somewhat perplexing that even The Encyclopedia of Tourism (Jafari 2003) does not

make any reference to mountain tourism, mentioning only ‘mountaineering’. How-

ever, this situation is gradually improving, as more researchers become interested in

mountain tourism issues (Price et al. 1997; Godde et al. 2000; Beedie and Hudson

2003; Nepal 2000, 2003).

This paper proposes a conceptual framework to examine recreation and tourism is-

sues in mountainous regions. This framework views the planning and management of

mountain amenity landscapes as essentially issues about supply, demand and manage-

ment (Figure 1). Within this framework, the supply of recreational opportunities in a

mountainous region is seen as influenced by its six resource characteristics: diversity,

marginality, difficult access, fragility, niche and aesthetics. The demand for recre-

ational activities is conceived as an outcome of the combined influences of the three

principal users: the local recreationists, the tourists and the amenity migrants. The

management of the supply and demand of mountain recreational opportunities can be

achieved best through a land-use zonation concept, which divides mountain amenity

landscapes into a nodal centre, a ‘frontcountry’ and a ‘backcountry’. It is argued that

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A Conceptual Framework for Mountain Tourism 315

Figure 1. Mountain tourism: a conceptual framework

this framework is useful in identifying zones of conflicts and contentions involving

the three users, and minimizing the vulnerability of mountain amenity resources to

degradation.

Discussion of the three main aspects of the conceptual framework is the focus of

this paper. First, the paper highlights the major resource characteristics that are unique

to mountains. Secondly, it examines the changing nature of recreation and tourism

use in the mountains, especially increasing levels of recreation and tourism activities

sought by local recreationists, tourists and amenity migrants. From the perspective

of these users, mountain regions can be described as amenity landscapes. Finally,

the paper proposes a three-class system of recreation and tourism land-use settings

that are relevant to the specific characteristics of the mountains. These three areas –

mountain characteristics, mountain amenity users and mountain recreational zoning

– are identified as worthy of additional research.

Mountain Resource Characteristics

Definitions of what characterizes mountains are unclear. Questions have been raised

about the suitability of elevation, volume, relief and steepness as the most commonly

applied criteria (Kapos et al. 2002). It is arguable that such a deterministic approach

looks at mountains as parts rather than as a whole, as it ignores the essential at-

tributes of mountain regions as landscapes including valleys, which give mountains

their distinct character. From a tourism perspective, a mountain defined by elevation

alone is inadequate. The watershed or ecosystem approach to the conceptualization

of mountains makes much more sense, as it attempts to define mountain areas based

on watershed or ecological boundaries, but, of course, the borders may mean nothing

Figure 1. Mountain tourism: a conceptual framework

this framework is useful in identifying zones of conflicts and contentions involving

the three users, and minimizing the vulnerability of mountain amenity resources to

degradation.

Discussion of the three main aspects of the conceptual framework is the focus of

this paper. First, the paper highlights the major resource characteristics that are unique

to mountains. Secondly, it examines the changing nature of recreation and tourism

use in the mountains, especially increasing levels of recreation and tourism activities

sought by local recreationists, tourists and amenity migrants. From the perspective

of these users, mountain regions can be described as amenity landscapes. Finally,

the paper proposes a three-class system of recreation and tourism land-use settings

that are relevant to the specific characteristics of the mountains. These three areas –

mountain characteristics, mountain amenity users and mountain recreational zoning

– are identified as worthy of additional research.

Mountain Resource Characteristics

Definitions of what characterizes mountains are unclear. Questions have been raised

about the suitability of elevation, volume, relief and steepness as the most commonly

applied criteria (Kapos et al. 2002). It is arguable that such a deterministic approach

looks at mountains as parts rather than as a whole, as it ignores the essential at-

tributes of mountain regions as landscapes including valleys, which give mountains

their distinct character. From a tourism perspective, a mountain defined by elevation

alone is inadequate. The watershed or ecosystem approach to the conceptualization

of mountains makes much more sense, as it attempts to define mountain areas based

on watershed or ecological boundaries, but, of course, the borders may mean nothing

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

316 S. K. Nepal & R. Chipeniuk

from a human perspective (ICIMOD 2004). Consider a community that is located in

the valley but uses its mountain backdrop to promote tourism inasmuch as the moun-

tain provides ideal recreation opportunities and other types of amenities, and other

primary resources (e.g. forests and minerals) that are important to local residents as

well as outsiders. The community could be located on adjacent plains and may not be

characterized as a mountain community if the elevation criterion is followed strictly.

The watershed or ecosystem approach could make sense, as the community may be

dependent on resources that are located in the mountains, while being physically

located on the plains; this approach implies that human–nature interactions are not

bounded by the physical transitions imposed by certain natural features.

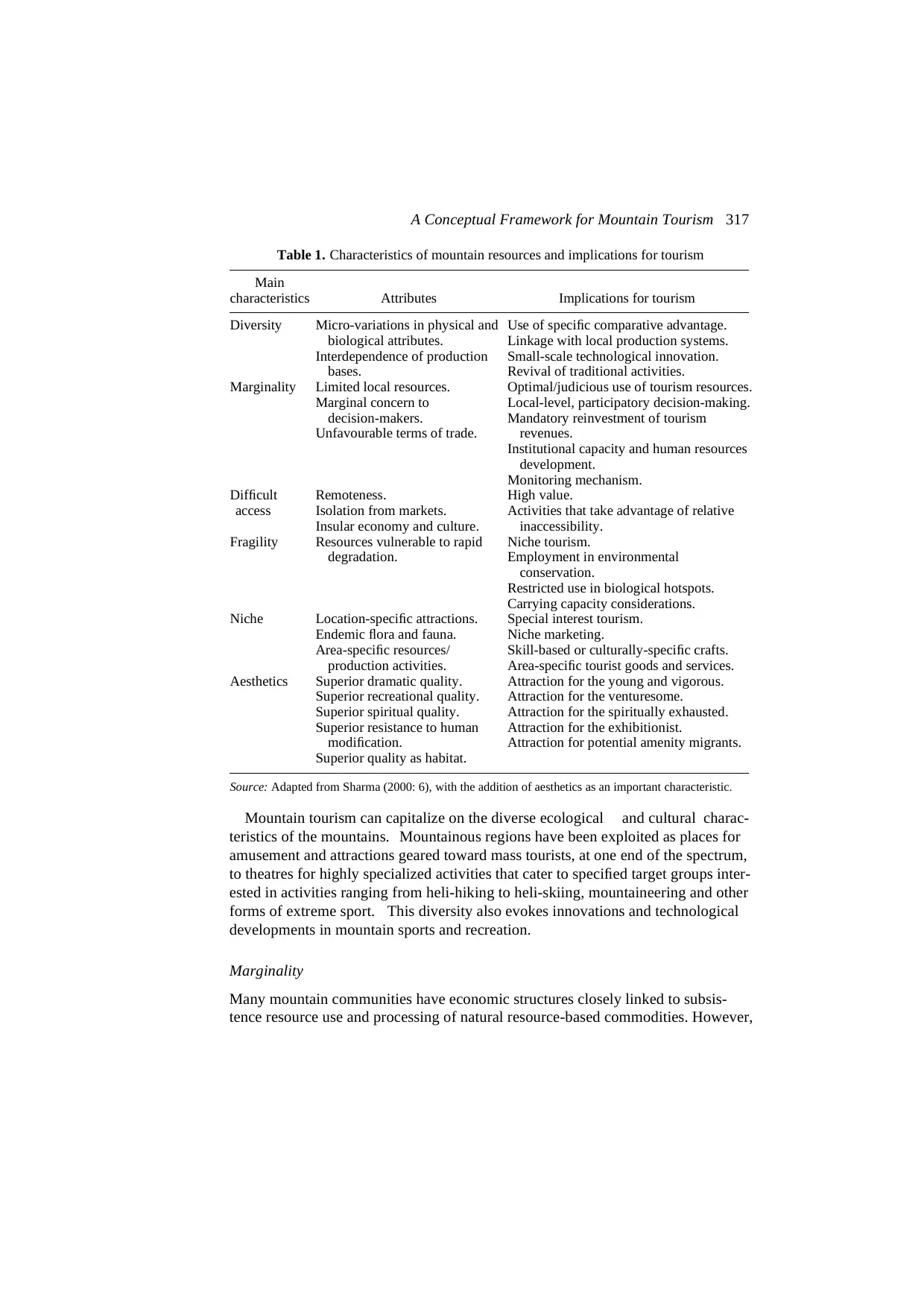

Jodha (1991) has argued that mountain areas are quite distinct from other phys-

iographic units and that ‘specificities’ such as diversity, marginality, inaccessibility,

fragility and niche have influenced the level of development of the mountains. Sharma

(2000) has applied these concepts to tourism development issues in mountainous re-

gions. To this one can add a further characteristic, namely the superior aesthetic

quality of mountain landscapes. Discussed primarily in the context of mountainous

regions in the developing economies, this concept of mountain specificities is relevant

to the developed economies as well, especially in terms of its potential application

to mountain ecotourism (Nepal 2002). Mountain diversity, marginality, inaccessibil-

ity, fragility, niche and aesthetics are interrelated and are dynamic concepts, as these

characteristics are influenced by one another and change over time and space depend-

ing on the level of tourism development (Table 1). Each of these issues is discussed

below.

Diversity

Mountain regions have high levels of both ecological and cultural diversity (Stepp

2000). The compression of life zones into a small horizontal distance has produced

a high level of diversity in landscapes, flora and fauna (Price and Neville 2003).

Ecological diversity has influenced the cultural diversity of the mountains, as people

have adapted to or changed their natural environments to ensure their survival (Pohle

1992). Many factors combine to create high levels of natural and cultural diversity at

the regional scale. The combination of steep altitudinal gradient, topographic variation

and range of aspects provides a rich variety of habitats at all scales (Etter and Villa

2000). As mountain ranges have risen over millions of years, many species have been

able to migrate along new pathways, exploiting new ecological niches. Geological

upheavals and climatic changes have repeatedly isolated populations, with the effect

that many mountain regions have high levels of endemic species. Various levels of

restrictions on human activities posed by physical challenges have produced a wide

spectrum of virtually unmodified to significantly altered landscapes. Regardless of

the degree of modification, mountain regions often have a higher level of diversity

than do the lowlands.

from a human perspective (ICIMOD 2004). Consider a community that is located in

the valley but uses its mountain backdrop to promote tourism inasmuch as the moun-

tain provides ideal recreation opportunities and other types of amenities, and other

primary resources (e.g. forests and minerals) that are important to local residents as

well as outsiders. The community could be located on adjacent plains and may not be

characterized as a mountain community if the elevation criterion is followed strictly.

The watershed or ecosystem approach could make sense, as the community may be

dependent on resources that are located in the mountains, while being physically

located on the plains; this approach implies that human–nature interactions are not

bounded by the physical transitions imposed by certain natural features.

Jodha (1991) has argued that mountain areas are quite distinct from other phys-

iographic units and that ‘specificities’ such as diversity, marginality, inaccessibility,

fragility and niche have influenced the level of development of the mountains. Sharma

(2000) has applied these concepts to tourism development issues in mountainous re-

gions. To this one can add a further characteristic, namely the superior aesthetic

quality of mountain landscapes. Discussed primarily in the context of mountainous

regions in the developing economies, this concept of mountain specificities is relevant

to the developed economies as well, especially in terms of its potential application

to mountain ecotourism (Nepal 2002). Mountain diversity, marginality, inaccessibil-

ity, fragility, niche and aesthetics are interrelated and are dynamic concepts, as these

characteristics are influenced by one another and change over time and space depend-

ing on the level of tourism development (Table 1). Each of these issues is discussed

below.

Diversity

Mountain regions have high levels of both ecological and cultural diversity (Stepp

2000). The compression of life zones into a small horizontal distance has produced

a high level of diversity in landscapes, flora and fauna (Price and Neville 2003).

Ecological diversity has influenced the cultural diversity of the mountains, as people

have adapted to or changed their natural environments to ensure their survival (Pohle

1992). Many factors combine to create high levels of natural and cultural diversity at

the regional scale. The combination of steep altitudinal gradient, topographic variation

and range of aspects provides a rich variety of habitats at all scales (Etter and Villa

2000). As mountain ranges have risen over millions of years, many species have been

able to migrate along new pathways, exploiting new ecological niches. Geological

upheavals and climatic changes have repeatedly isolated populations, with the effect

that many mountain regions have high levels of endemic species. Various levels of

restrictions on human activities posed by physical challenges have produced a wide

spectrum of virtually unmodified to significantly altered landscapes. Regardless of

the degree of modification, mountain regions often have a higher level of diversity

than do the lowlands.

A Conceptual Framework for Mountain Tourism 317

Table 1. Characteristics of mountain resources and implications for tourism

Main

characteristics Attributes Implications for tourism

Diversity Micro-variations in physical and

biological attributes.

Interdependence of production

bases.

Use of specific comparative advantage.

Linkage with local production systems.

Small-scale technological innovation.

Revival of traditional activities.

Marginality Limited local resources.

Marginal concern to

decision-makers.

Unfavourable terms of trade.

Optimal/judicious use of tourism resources.

Local-level, participatory decision-making.

Mandatory reinvestment of tourism

revenues.

Institutional capacity and human resources

development.

Monitoring mechanism.

Difficult

access

Remoteness.

Isolation from markets.

Insular economy and culture.

High value.

Activities that take advantage of relative

inaccessibility.

Fragility Resources vulnerable to rapid

degradation.

Niche tourism.

Employment in environmental

conservation.

Restricted use in biological hotspots.

Carrying capacity considerations.

Niche Location-specific attractions.

Endemic flora and fauna.

Area-specific resources/

production activities.

Special interest tourism.

Niche marketing.

Skill-based or culturally-specific crafts.

Area-specific tourist goods and services.

Aesthetics Superior dramatic quality.

Superior recreational quality.

Superior spiritual quality.

Superior resistance to human

modification.

Superior quality as habitat.

Attraction for the young and vigorous.

Attraction for the venturesome.

Attraction for the spiritually exhausted.

Attraction for the exhibitionist.

Attraction for potential amenity migrants.

Source: Adapted from Sharma (2000: 6), with the addition of aesthetics as an important characteristic.

Mountain tourism can capitalize on the diverse ecological and cultural charac-

teristics of the mountains. Mountainous regions have been exploited as places for

amusement and attractions geared toward mass tourists, at one end of the spectrum,

to theatres for highly specialized activities that cater to specified target groups inter-

ested in activities ranging from heli-hiking to heli-skiing, mountaineering and other

forms of extreme sport. This diversity also evokes innovations and technological

developments in mountain sports and recreation.

Marginality

Many mountain communities have economic structures closely linked to subsis-

tence resource use and processing of natural resource-based commodities. However,

Table 1. Characteristics of mountain resources and implications for tourism

Main

characteristics Attributes Implications for tourism

Diversity Micro-variations in physical and

biological attributes.

Interdependence of production

bases.

Use of specific comparative advantage.

Linkage with local production systems.

Small-scale technological innovation.

Revival of traditional activities.

Marginality Limited local resources.

Marginal concern to

decision-makers.

Unfavourable terms of trade.

Optimal/judicious use of tourism resources.

Local-level, participatory decision-making.

Mandatory reinvestment of tourism

revenues.

Institutional capacity and human resources

development.

Monitoring mechanism.

Difficult

access

Remoteness.

Isolation from markets.

Insular economy and culture.

High value.

Activities that take advantage of relative

inaccessibility.

Fragility Resources vulnerable to rapid

degradation.

Niche tourism.

Employment in environmental

conservation.

Restricted use in biological hotspots.

Carrying capacity considerations.

Niche Location-specific attractions.

Endemic flora and fauna.

Area-specific resources/

production activities.

Special interest tourism.

Niche marketing.

Skill-based or culturally-specific crafts.

Area-specific tourist goods and services.

Aesthetics Superior dramatic quality.

Superior recreational quality.

Superior spiritual quality.

Superior resistance to human

modification.

Superior quality as habitat.

Attraction for the young and vigorous.

Attraction for the venturesome.

Attraction for the spiritually exhausted.

Attraction for the exhibitionist.

Attraction for potential amenity migrants.

Source: Adapted from Sharma (2000: 6), with the addition of aesthetics as an important characteristic.

Mountain tourism can capitalize on the diverse ecological and cultural charac-

teristics of the mountains. Mountainous regions have been exploited as places for

amusement and attractions geared toward mass tourists, at one end of the spectrum,

to theatres for highly specialized activities that cater to specified target groups inter-

ested in activities ranging from heli-hiking to heli-skiing, mountaineering and other

forms of extreme sport. This diversity also evokes innovations and technological

developments in mountain sports and recreation.

Marginality

Many mountain communities have economic structures closely linked to subsis-

tence resource use and processing of natural resource-based commodities. However,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

318 S. K. Nepal & R. Chipeniuk

mountain communities have historically been neglected in development priorities, as

they are often located in peripheral regions. Increased dependency, unequal terms of

exchange and gradual loss of autonomy over resource use or decision-making are

common characteristics of many mountain communities (Sharma 2000). The result

is poverty, a characteristic shared by all mountain peoples, even in the Swiss Alps

(Ives 1996). Outsiders often perceive mountain regions as lands where opportunities

for earning a livelihood are marginal (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987). Moreover, many

mountain regions are borderlands between states and between regions and political

units within a state. As such, mountain regions are characterized by economic, po-

litical and cultural uncertainty and instability (Smethurst 2000). The last decade has

seen an increase in incidents of violence and ethnic conflicts in several mountain

communities around the world, most notably in Central and South Asia, making the

poorer communities there even more vulnerable to displacement, poverty and human

rights abuse.

The development of mountain tourism in these contexts implies that decentralized

decision-making processes and reinvestment of tourism-generated revenues at the

local level to diversify the economic base are important considerations when the

goal is to achieve restructuring of mountain economies. Participatory approaches to

mountain tourism planning processes, local level consultations with key stakeholders,

local inputs in the monitoring of key ecological (e.g. waste disposal, wildlife impacts)

and social indicators (e.g. affordable housing, fair wages and jobs, local skills) and

preferential treatment in income and employment opportunities in the local tourism

industry are essential to ensure long-term sustainability of mountain tourism projects.

Difficult Access

Difficult access to and relatively undeveloped infrastructure within mountain regions

have traditionally restricted the external linkages of mountain economies. Where

transport corridors have been established, net outflow of resources from the moun-

tains has occurred (Blaikie et al. 1980). In some cases, emphasis on high-value,

low-bulk products has been the adaptive response of mountain communities. While

difficult access usually means a low volume of tourists, it also provides opportunities

for developing high-value tourism products. For example, many remote mountain

locations in the Canadian Rockies, Interior Ranges, and British Columbia (BC) Coast

Range attract tourists who are willing to pay substantial amounts of money for their

visits. Elsewhere, mountain tourism activities that thrive on relative inaccessibility,

such as trekking, mountaineering and other forms of adventure tourism, can provide

new forms of adaptation to conditions of inaccessibility. Various forms of ecotourism

activities that take advantage of relative isolation and difficult access are constantly

developing in the mountainous regions of the world (Mountain Agenda 1999).

On the other hand, many mountain communities that were previously thought to

be located remotely are now connected to large urban centres due to expanded air

mountain communities have historically been neglected in development priorities, as

they are often located in peripheral regions. Increased dependency, unequal terms of

exchange and gradual loss of autonomy over resource use or decision-making are

common characteristics of many mountain communities (Sharma 2000). The result

is poverty, a characteristic shared by all mountain peoples, even in the Swiss Alps

(Ives 1996). Outsiders often perceive mountain regions as lands where opportunities

for earning a livelihood are marginal (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987). Moreover, many

mountain regions are borderlands between states and between regions and political

units within a state. As such, mountain regions are characterized by economic, po-

litical and cultural uncertainty and instability (Smethurst 2000). The last decade has

seen an increase in incidents of violence and ethnic conflicts in several mountain

communities around the world, most notably in Central and South Asia, making the

poorer communities there even more vulnerable to displacement, poverty and human

rights abuse.

The development of mountain tourism in these contexts implies that decentralized

decision-making processes and reinvestment of tourism-generated revenues at the

local level to diversify the economic base are important considerations when the

goal is to achieve restructuring of mountain economies. Participatory approaches to

mountain tourism planning processes, local level consultations with key stakeholders,

local inputs in the monitoring of key ecological (e.g. waste disposal, wildlife impacts)

and social indicators (e.g. affordable housing, fair wages and jobs, local skills) and

preferential treatment in income and employment opportunities in the local tourism

industry are essential to ensure long-term sustainability of mountain tourism projects.

Difficult Access

Difficult access to and relatively undeveloped infrastructure within mountain regions

have traditionally restricted the external linkages of mountain economies. Where

transport corridors have been established, net outflow of resources from the moun-

tains has occurred (Blaikie et al. 1980). In some cases, emphasis on high-value,

low-bulk products has been the adaptive response of mountain communities. While

difficult access usually means a low volume of tourists, it also provides opportunities

for developing high-value tourism products. For example, many remote mountain

locations in the Canadian Rockies, Interior Ranges, and British Columbia (BC) Coast

Range attract tourists who are willing to pay substantial amounts of money for their

visits. Elsewhere, mountain tourism activities that thrive on relative inaccessibility,

such as trekking, mountaineering and other forms of adventure tourism, can provide

new forms of adaptation to conditions of inaccessibility. Various forms of ecotourism

activities that take advantage of relative isolation and difficult access are constantly

developing in the mountainous regions of the world (Mountain Agenda 1999).

On the other hand, many mountain communities that were previously thought to

be located remotely are now connected to large urban centres due to expanded air

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A Conceptual Framework for Mountain Tourism 319

transport networks. Better air connections have enabled many urban residents to buy

homes in scenic mountain environments (e.g. Vail and Aspen), primarily because

residents in such places now have the option and the ability to travel conveniently

to large cities. In some mountain communities the advent of the Internet has made

information vastly easier to obtain, encouraging metropolitan-to-mountain migration.

However, for the vast majority of people in remote communities difficult access

remains a problem.

Fragility

Fragility is a key attribute of ecological processes in the mountains and it refers to

a stress and response condition, i.e. the response of the mountain environment to

natural and human activities. Although the concept is potentially ambiguous, as dif-

ferent activities have different stress–response conditions (Buckley 2000), in general,

mountain resources are characterized by low carrying capacities and they are vul-

nerable to accelerated land degradation. Mountains are fragile mainly due to steep

topography, altitude, geology and climatic extremes. Increased rates of erosion, fre-

quent landslides, avalanches and floods, and loss of flora and fauna are examples

of fragility. The implication is that particular activities can be undertaken only at a

certain scale and at specified locations. However, due to increasing pressure for de-

velopment, issues of fragility have often been overlooked and this is especially true

in the development of tourism-related infrastructure.

Fragility of mountain environments can itself be a tourism asset and thus requires

protection. For example, a rock cliff which is used for climbing needs protection, as do

collection areas above avalanche chutes, which can be opened for recreation activities

only at certain times of the year. Fragility requires that tourism development must

emphasize environmental conservation and regeneration, in the absence of which

irreversible damage to resources can occur (Cole and Sinclair 2002). In the tourism

context, assessment of fragility involves the identification of conservation values of the

environment where development is proposed, selection of key indicators to measure

changes, determination of the types of tourist activity that can be accommodated,

the examination of indicators responding to various intensities of recreation and the

establishment of effective monitoring programmes that can assess the stress–response

relationship reliably (Buckley 2000). However, the reality is that recreation activities

such as hiking, heli-skiing, cat-skiing and snowmobiling are on the rise in backcountry

areas of some mountain ranges, and the control and management of them are more the

exception rather than the rule. Backcountry recreation is an important issue and must

be addressed if managers are to avoid irreversible damage to mountain resources.

Niche

A concomitant of diversity is the relative or absolute comparative advantage or niche

afforded by particular locations and areas for recreation activity specialization. Some

transport networks. Better air connections have enabled many urban residents to buy

homes in scenic mountain environments (e.g. Vail and Aspen), primarily because

residents in such places now have the option and the ability to travel conveniently

to large cities. In some mountain communities the advent of the Internet has made

information vastly easier to obtain, encouraging metropolitan-to-mountain migration.

However, for the vast majority of people in remote communities difficult access

remains a problem.

Fragility

Fragility is a key attribute of ecological processes in the mountains and it refers to

a stress and response condition, i.e. the response of the mountain environment to

natural and human activities. Although the concept is potentially ambiguous, as dif-

ferent activities have different stress–response conditions (Buckley 2000), in general,

mountain resources are characterized by low carrying capacities and they are vul-

nerable to accelerated land degradation. Mountains are fragile mainly due to steep

topography, altitude, geology and climatic extremes. Increased rates of erosion, fre-

quent landslides, avalanches and floods, and loss of flora and fauna are examples

of fragility. The implication is that particular activities can be undertaken only at a

certain scale and at specified locations. However, due to increasing pressure for de-

velopment, issues of fragility have often been overlooked and this is especially true

in the development of tourism-related infrastructure.

Fragility of mountain environments can itself be a tourism asset and thus requires

protection. For example, a rock cliff which is used for climbing needs protection, as do

collection areas above avalanche chutes, which can be opened for recreation activities

only at certain times of the year. Fragility requires that tourism development must

emphasize environmental conservation and regeneration, in the absence of which

irreversible damage to resources can occur (Cole and Sinclair 2002). In the tourism

context, assessment of fragility involves the identification of conservation values of the

environment where development is proposed, selection of key indicators to measure

changes, determination of the types of tourist activity that can be accommodated,

the examination of indicators responding to various intensities of recreation and the

establishment of effective monitoring programmes that can assess the stress–response

relationship reliably (Buckley 2000). However, the reality is that recreation activities

such as hiking, heli-skiing, cat-skiing and snowmobiling are on the rise in backcountry

areas of some mountain ranges, and the control and management of them are more the

exception rather than the rule. Backcountry recreation is an important issue and must

be addressed if managers are to avoid irreversible damage to mountain resources.

Niche

A concomitant of diversity is the relative or absolute comparative advantage or niche

afforded by particular locations and areas for recreation activity specialization. Some

320 S. K. Nepal & R. Chipeniuk

types of outdoor recreation activities, such as paragliding, rock climbing, moun-

taineering, trekking, heli-ski and heli-hike, glacier walking, ice climbing, downhill

ski and mountain biking, are possible only in the mountains. The tourism industry has

exploited this niche with the constant invention, promotion and effective marketing

of new trends, sporting equipment and types of activity in the mountains. However,

consideration should be given to the exploitation of this niche within the limits of

carrying capacities, which are a function of the fragility and diversity of mountain

resources. By focusing development on the unique natural and cultural resources of

the mountains, communities may successfully increase income, enhance their ability

to adjust to change and achieve important community-level objectives (McCool and

Lachapelle 2000).

Aesthetics

Mountain landscapes typically strike people as being of exceptional aesthetic quality.

Why this should be so is unclear. For some reason landscape preference studies have

not examined preferences for mountain landscapes in the same fashion as preferences

for scenes with water or savanna (cf. for example the landmark research of Kaplan

and Kaplan (1989)). At one time, history-of-ideas explanations (e.g. Nicolson 1997;

Glacken 1967; Nash 1982) were considered adequate when they appealed to the

Romantic artistic and literary tradition, but today they do not measure up against

the new standards of evolutionary psychology or cross-cultural research (e.g. Orians

1980; Balling and Falk 1982; Cosmides et al. 1992; Orians and Heerwagen 1992).

Across a wide range of cultures, people regard mountain landscapes as superior

in their dramatic quality and their ability to evoke a sense of the numinous. People

in many cultures also regard mountains as superior in the quality and range of op-

portunities they offer for recreation, partly because mountains tend to be in a more

natural condition than flatter lands which offer less resistance to human modification.

Finally, mountains often strike visitors as highly desirable as residential locations,

sometimes for the same reasons as those which attracted them as tourists, sometimes

for amenities (such as a high proportion of amenity migrants already settled in the

area) that they do not demand in the destinations to which they travel as tourists.

The above-mentioned mountain resource characteristics have significant implica-

tions for planning mountain tourism, especially when one considers the diverse needs

and activities of various users. Diversity, in turn, implies that sustainable tourism man-

agement in the mountains must consider resolution of potential conflicts between the

recreation needs of these users and between the needs of these users and the needs of

residents and amenity migrants.

Mountains as Amenity Landscapes

Many popular mountain destinations in North America (e.g. Whistler, Aspen, Vail)

have evolved as local attractions for outdoor recreation, only to be discovered later

types of outdoor recreation activities, such as paragliding, rock climbing, moun-

taineering, trekking, heli-ski and heli-hike, glacier walking, ice climbing, downhill

ski and mountain biking, are possible only in the mountains. The tourism industry has

exploited this niche with the constant invention, promotion and effective marketing

of new trends, sporting equipment and types of activity in the mountains. However,

consideration should be given to the exploitation of this niche within the limits of

carrying capacities, which are a function of the fragility and diversity of mountain

resources. By focusing development on the unique natural and cultural resources of

the mountains, communities may successfully increase income, enhance their ability

to adjust to change and achieve important community-level objectives (McCool and

Lachapelle 2000).

Aesthetics

Mountain landscapes typically strike people as being of exceptional aesthetic quality.

Why this should be so is unclear. For some reason landscape preference studies have

not examined preferences for mountain landscapes in the same fashion as preferences

for scenes with water or savanna (cf. for example the landmark research of Kaplan

and Kaplan (1989)). At one time, history-of-ideas explanations (e.g. Nicolson 1997;

Glacken 1967; Nash 1982) were considered adequate when they appealed to the

Romantic artistic and literary tradition, but today they do not measure up against

the new standards of evolutionary psychology or cross-cultural research (e.g. Orians

1980; Balling and Falk 1982; Cosmides et al. 1992; Orians and Heerwagen 1992).

Across a wide range of cultures, people regard mountain landscapes as superior

in their dramatic quality and their ability to evoke a sense of the numinous. People

in many cultures also regard mountains as superior in the quality and range of op-

portunities they offer for recreation, partly because mountains tend to be in a more

natural condition than flatter lands which offer less resistance to human modification.

Finally, mountains often strike visitors as highly desirable as residential locations,

sometimes for the same reasons as those which attracted them as tourists, sometimes

for amenities (such as a high proportion of amenity migrants already settled in the

area) that they do not demand in the destinations to which they travel as tourists.

The above-mentioned mountain resource characteristics have significant implica-

tions for planning mountain tourism, especially when one considers the diverse needs

and activities of various users. Diversity, in turn, implies that sustainable tourism man-

agement in the mountains must consider resolution of potential conflicts between the

recreation needs of these users and between the needs of these users and the needs of

residents and amenity migrants.

Mountains as Amenity Landscapes

Many popular mountain destinations in North America (e.g. Whistler, Aspen, Vail)

have evolved as local attractions for outdoor recreation, only to be discovered later

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A Conceptual Framework for Mountain Tourism 321

by tourists, to emerge, with time and development pressure, as major international

tourism destinations. Mountain tourism destinations have quickly become locations

of seasonal residences for many tourists and, in some cases, they have attracted people

who want to settle permanently in and around areas with significant amenity values

– amenity migrants. Gill (1998) has classified residents of mountain resorts into four

categories: permanent residents, second-home owners, seasonal workers and tourists.

In the context of this paper, three primary groups of recreation users are identified.

First are the locals who pursue a variety of outdoor recreation activities. Gill refers to

these people as permanent residents; however, it should be acknowledged that not all

permanent residents may be local recreationists. The second group includes amenity

migrants by some definitions, in which second-home owners and seasonal workers

are included (e.g. Glorioso 2000). Most authors consider amenity migration to en-

tail permanent residence, although some do include second-home owners within the

meaning of the term (Moss 1994; Glorioso 2000; Moss and Godde 2000). Amenity

migrants are referred to here as those who have moved to a place and became per-

manent residents not because of a job or other economic reasons but for the natural

or social amenities found at that place (Chipeniuk 2005). Amenity migration is fast

becoming an interesting area of research within the larger context of leisure, recre-

ation, tourism and planning, as indicated by the recent publication of a book on this

subject (Hall and M¨uller 2004). The third category of users comprises the tourists. In

short, outdoor recreation, amenity migration and tourism are essential characteristics

of many established and evolving mountain tourism destinations. This association,

in turn, gives rise to conflict and co-existence among outdoor recreation, amenity

migration and tourism.

Five potential kinds of conflict exist: (1) conflicts between local residents (who use

mountain amenities for their recreation) and tourists; (2) conflicts between amenity

migrants (those who settle permanently) and local residents; (3) conflicts between

amenity migrants and tourists; (4) conflicts within each category of recreationists;

and (5) conflicts involving all three groups of recreationists. Additionally, conflicts

may exist between people engaged in recreational pursuits in the mountains and local

residents not engaged in mountain-based recreation due to differences in perspectives,

values, traditions and beliefs about local mountains (Jurowski 1994; Jurowski et al.

1997; Lankford et al. 1997). For example, mountains are often regarded as ‘sacred’

grounds by local residents who prefer not to climb them, while visitors may perceive

them as ‘pleasure’ grounds, to be attacked, assaulted or commercialized (Ortner 2001).

The present discussion is limited to the conflicts between users of mountain recreation

resources. This complexity affords enormous challenges to tourism planners when

dealing with mountain tourism issues.

While current research on tourism is focused overwhelmingly on conflicts between

local residents and tourists (Smith 1989; Smith and Brent 2001; Lankford et al. 2003)

or between urban and rural residents who use the same resources (Saremba and Gill

1991), outdoor recreation literature is focused on conflicts between various types of

by tourists, to emerge, with time and development pressure, as major international

tourism destinations. Mountain tourism destinations have quickly become locations

of seasonal residences for many tourists and, in some cases, they have attracted people

who want to settle permanently in and around areas with significant amenity values

– amenity migrants. Gill (1998) has classified residents of mountain resorts into four

categories: permanent residents, second-home owners, seasonal workers and tourists.

In the context of this paper, three primary groups of recreation users are identified.

First are the locals who pursue a variety of outdoor recreation activities. Gill refers to

these people as permanent residents; however, it should be acknowledged that not all

permanent residents may be local recreationists. The second group includes amenity

migrants by some definitions, in which second-home owners and seasonal workers

are included (e.g. Glorioso 2000). Most authors consider amenity migration to en-

tail permanent residence, although some do include second-home owners within the

meaning of the term (Moss 1994; Glorioso 2000; Moss and Godde 2000). Amenity

migrants are referred to here as those who have moved to a place and became per-

manent residents not because of a job or other economic reasons but for the natural

or social amenities found at that place (Chipeniuk 2005). Amenity migration is fast

becoming an interesting area of research within the larger context of leisure, recre-

ation, tourism and planning, as indicated by the recent publication of a book on this

subject (Hall and M¨uller 2004). The third category of users comprises the tourists. In

short, outdoor recreation, amenity migration and tourism are essential characteristics

of many established and evolving mountain tourism destinations. This association,

in turn, gives rise to conflict and co-existence among outdoor recreation, amenity

migration and tourism.

Five potential kinds of conflict exist: (1) conflicts between local residents (who use

mountain amenities for their recreation) and tourists; (2) conflicts between amenity

migrants (those who settle permanently) and local residents; (3) conflicts between

amenity migrants and tourists; (4) conflicts within each category of recreationists;

and (5) conflicts involving all three groups of recreationists. Additionally, conflicts

may exist between people engaged in recreational pursuits in the mountains and local

residents not engaged in mountain-based recreation due to differences in perspectives,

values, traditions and beliefs about local mountains (Jurowski 1994; Jurowski et al.

1997; Lankford et al. 1997). For example, mountains are often regarded as ‘sacred’

grounds by local residents who prefer not to climb them, while visitors may perceive

them as ‘pleasure’ grounds, to be attacked, assaulted or commercialized (Ortner 2001).

The present discussion is limited to the conflicts between users of mountain recreation

resources. This complexity affords enormous challenges to tourism planners when

dealing with mountain tourism issues.

While current research on tourism is focused overwhelmingly on conflicts between

local residents and tourists (Smith 1989; Smith and Brent 2001; Lankford et al. 2003)

or between urban and rural residents who use the same resources (Saremba and Gill

1991), outdoor recreation literature is focused on conflicts between various types of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

322 S. K. Nepal & R. Chipeniuk

recreationists, for example, between hikers and mountain bikers (Ramthun 1995) or

between skiers and snowmobilers (Wilson and Seney 1994; Vittersø et al. 2004).

There is very little research on conflicts between tourists and amenity migrants, even

though they compete for and share the same space and facilities and they may attach

different sets of values to tourism and amenity resources. Examples of such conflicts

are already found in the mountains of BC, Canada where many local backcountry

skiers and snowmobilers resent heli-ski tourism because it excludes them from certain

areas. Indeed, similar conflicts between cross-country skiers and snowmobilers have

been well documented in Alberta, Canada (Jackson and Wong 1982). Saremba and

Gill (1991) have documented value conflicts between rural and urban residents in the

context of a mountain park setting near Whistler, Canada, and similar examples can

be found elsewhere. One source of the current resistance to development at Jumbo

in southern BC (a proposed downhill ski development) is this kind of conflict, and

the same is true of opposition to heli-ski operations in the Bulkley Valley in north-

western BC. Local residents, especially those who live there to earn a living or whose

families have been there for generations, often have mixed feelings about tourists and

amenity migrants because they drive up property values (of course, this has its good

side too) and compete with locals for recreational space. Concerns such as these were

expressed openly at a community hall meeting in Valemount, a mountain commu-

nity west of Jasper National Park, where a substantial resort complex was proposed

and recently approved after very little consultation with local residents (Nepal 2004).

Other concerns may include increased environmental pollution, increased costs of

recreation and resistance to foreign cultures or sub-cultures. In Smithers, a small

town in the Bulkley Valley, some residents speaking at public meetings opposed the

proposed expansion of a downhill ski resort meant to attract more tourists because it

would increase the cost of lift tickets greatly and increase the amount of time spent

waiting in lift lines. Similarly, conflicts between different sorts of local recreation-

ists are common, for example between skiers and snowmobilers. Conflicts between

commercially guided canoeists and non-guided canoeists on high-quality wilderness

rivers, such as the Nahanni in the Northwest Territories of Canada, represent a type

of conflict between groups of tourists (Shelby and Heberlein 1986). There is also

the potential for conflict between rich amenity migrants and low- or middle-income

amenity migrants, because the rich may outbid the less well off for desirable rural

property. Conflicts among the three categories of amenity users may also be common,

although research examining such multi-dimensional conflicts does not exist. Such

conflicts arise primarily due to differences in personal values, lifestyle choice, attitude

towards nature and people or community and other intrinsic and extrinsic character-

istics of the users (Jacob and Schreyer 1980; Saremba and Gill 1991; Williams 2000).

A generic descriptor of the three types of amenity users –local recreationists, tourists

and amenity migrants – is shown in Table 2.

Based on Table 2, some hypotheses about the characteristics of local economic

residents, tourists and amenity migrants are proposed in the following sections. Local

recreationists, for example, between hikers and mountain bikers (Ramthun 1995) or

between skiers and snowmobilers (Wilson and Seney 1994; Vittersø et al. 2004).

There is very little research on conflicts between tourists and amenity migrants, even

though they compete for and share the same space and facilities and they may attach

different sets of values to tourism and amenity resources. Examples of such conflicts

are already found in the mountains of BC, Canada where many local backcountry

skiers and snowmobilers resent heli-ski tourism because it excludes them from certain

areas. Indeed, similar conflicts between cross-country skiers and snowmobilers have

been well documented in Alberta, Canada (Jackson and Wong 1982). Saremba and

Gill (1991) have documented value conflicts between rural and urban residents in the

context of a mountain park setting near Whistler, Canada, and similar examples can

be found elsewhere. One source of the current resistance to development at Jumbo

in southern BC (a proposed downhill ski development) is this kind of conflict, and

the same is true of opposition to heli-ski operations in the Bulkley Valley in north-

western BC. Local residents, especially those who live there to earn a living or whose

families have been there for generations, often have mixed feelings about tourists and

amenity migrants because they drive up property values (of course, this has its good

side too) and compete with locals for recreational space. Concerns such as these were

expressed openly at a community hall meeting in Valemount, a mountain commu-

nity west of Jasper National Park, where a substantial resort complex was proposed

and recently approved after very little consultation with local residents (Nepal 2004).

Other concerns may include increased environmental pollution, increased costs of

recreation and resistance to foreign cultures or sub-cultures. In Smithers, a small

town in the Bulkley Valley, some residents speaking at public meetings opposed the

proposed expansion of a downhill ski resort meant to attract more tourists because it

would increase the cost of lift tickets greatly and increase the amount of time spent

waiting in lift lines. Similarly, conflicts between different sorts of local recreation-

ists are common, for example between skiers and snowmobilers. Conflicts between

commercially guided canoeists and non-guided canoeists on high-quality wilderness

rivers, such as the Nahanni in the Northwest Territories of Canada, represent a type

of conflict between groups of tourists (Shelby and Heberlein 1986). There is also

the potential for conflict between rich amenity migrants and low- or middle-income

amenity migrants, because the rich may outbid the less well off for desirable rural

property. Conflicts among the three categories of amenity users may also be common,

although research examining such multi-dimensional conflicts does not exist. Such

conflicts arise primarily due to differences in personal values, lifestyle choice, attitude

towards nature and people or community and other intrinsic and extrinsic character-

istics of the users (Jacob and Schreyer 1980; Saremba and Gill 1991; Williams 2000).

A generic descriptor of the three types of amenity users –local recreationists, tourists

and amenity migrants – is shown in Table 2.

Based on Table 2, some hypotheses about the characteristics of local economic

residents, tourists and amenity migrants are proposed in the following sections. Local

A Conceptual Framework for Mountain Tourism 323

Table 2. Characteristics of amenity users in the mountains

Outdoor

recreationists (local) Tourists Amenity migrants

Sense of place and place

attachment

Images of place Sense of place; strong sense

of place as self-expression

High degree of familiarity

with local customs and

environments

Low degree of familiarity

with local cultures and

environments; exploration

and discovery

Moderate degree of

familiarity with local

cultures and environments

Unrestricted use of space Restricted and regulated

access to recreational space

Regulated access

Easy access Escapism Pioneers of new forms and

styles of recreation

Well-defined pattern of

recreation frequency and

intensity

Intensive use of facilities, but

at unpredictable

frequencies

Strong ties to other places

May exhibit the NIMBY

syndrome; strongly

territorial

Less territorial Moderate territoriality and

resistance to change

High degree of participation

in civic life

No participation in civic life High degree of participation

in civic life

High quality environments

important

High quality environments

desired

Demand for high-quality

environments

Likely to be displaced by

tourists

Some will be repeat visitors,

most will likely not return

Likely to be displaced by

tourists but minimal

susceptibility to economic

conditions

residents in many mountain communities have a strong sense of place and are rooted

firmly in their community (Jordon 1980). Recent literature on sense of place and place

attachment supports this hypothesis (Kyle et al. 2004). Residents are highly familiar

with their recreational environments and are knowledgeable about access and restric-

tions on access to certain areas (e.g. sacred burial grounds). Patterns of recreational

preferences, including the type of recreation, duration of recreation, frequency and

utilization of space, are fairly predictable and well defined. Residents exhibit symp-

toms of territoriality and the not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) syndrome. They are not

supportive of tourism development if the development diminishes opportunities for

outdoor recreation for local residents (Lankford et al. 2003).

Tourists, on the other hand, visit the mountains with acquired (through media

and tour promotional packages) images of a place and its inhabitants. Although not

discussed in the context of mountains, Herbert (2001) has found that perceived images

of a place are an important determinant of a visitor’s satisfaction. This satisfaction

may be achieved through exploration and discovery at a superficial level. Thus, real

immersion into local cultures and environments may not be required to attain complete

Table 2. Characteristics of amenity users in the mountains

Outdoor

recreationists (local) Tourists Amenity migrants

Sense of place and place

attachment

Images of place Sense of place; strong sense

of place as self-expression

High degree of familiarity

with local customs and

environments

Low degree of familiarity

with local cultures and

environments; exploration

and discovery

Moderate degree of

familiarity with local

cultures and environments

Unrestricted use of space Restricted and regulated

access to recreational space

Regulated access

Easy access Escapism Pioneers of new forms and

styles of recreation

Well-defined pattern of

recreation frequency and

intensity

Intensive use of facilities, but

at unpredictable

frequencies

Strong ties to other places

May exhibit the NIMBY

syndrome; strongly

territorial

Less territorial Moderate territoriality and

resistance to change

High degree of participation

in civic life

No participation in civic life High degree of participation

in civic life

High quality environments

important

High quality environments

desired

Demand for high-quality

environments

Likely to be displaced by

tourists

Some will be repeat visitors,

most will likely not return

Likely to be displaced by

tourists but minimal

susceptibility to economic

conditions

residents in many mountain communities have a strong sense of place and are rooted

firmly in their community (Jordon 1980). Recent literature on sense of place and place

attachment supports this hypothesis (Kyle et al. 2004). Residents are highly familiar

with their recreational environments and are knowledgeable about access and restric-

tions on access to certain areas (e.g. sacred burial grounds). Patterns of recreational

preferences, including the type of recreation, duration of recreation, frequency and

utilization of space, are fairly predictable and well defined. Residents exhibit symp-

toms of territoriality and the not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) syndrome. They are not

supportive of tourism development if the development diminishes opportunities for

outdoor recreation for local residents (Lankford et al. 2003).

Tourists, on the other hand, visit the mountains with acquired (through media

and tour promotional packages) images of a place and its inhabitants. Although not

discussed in the context of mountains, Herbert (2001) has found that perceived images

of a place are an important determinant of a visitor’s satisfaction. This satisfaction

may be achieved through exploration and discovery at a superficial level. Thus, real

immersion into local cultures and environments may not be required to attain complete

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 22

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.