A Diary Study of Conflict, Negative Emotions, and Performance at Work

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|18

|10898

|145

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review examines a diary study investigating the impact of daily workplace conflicts on employees' emotions and performance. The study, conducted in the Netherlands, explores how different types of conflict (task, relationship, and process) relate to both active (anger, contempt) and passive (sadness, guilt) negative emotions. It also introduces the concept of conflict detachment as a coping mechanism and analyzes its moderating effect on the relationship between conflict and negative emotions. The findings reveal that daily relationship and process conflicts are positively linked to negative emotions, and passive negative emotions have a lagged effect on in-role and extra-role performance. Furthermore, conflict detachment is found to mitigate the impact of conflict on negative emotions. The review highlights the study's contributions to understanding the psychological processes involved in workplace conflict and its implications for organizational practices. Desklib offers a variety of resources for students, including similar solved assignments and past papers.

Conflict at work, negative emotions, and performan

Rispens, S.; Demerouti, E.

Published in:

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research

DOI:

10.1111/ncmr.12069

Published: 01/05/2016

Document Version

Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume number

Please check the document version of this publication:

• A submitted manuscript is the author's version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be imp

between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised

author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website.

• The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review.

• The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers.

Link to publication

Citation for published version (APA):

Rispens, S., & Demerouti, E. (2016). Conflict at work, negative emotions, and performance: a diar

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(2), 103-119. DOI: 10.1111/ncmr.12069

General rights

Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or oth

and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with th

• Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study

Rispens, S.; Demerouti, E.

Published in:

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research

DOI:

10.1111/ncmr.12069

Published: 01/05/2016

Document Version

Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume number

Please check the document version of this publication:

• A submitted manuscript is the author's version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be imp

between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised

author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website.

• The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review.

• The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers.

Link to publication

Citation for published version (APA):

Rispens, S., & Demerouti, E. (2016). Conflict at work, negative emotions, and performance: a diar

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(2), 103-119. DOI: 10.1111/ncmr.12069

General rights

Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or oth

and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with th

• Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Conflict at Work, Negative Emotions, and

Performance: A Diary Study

Sonja Rispens and Evangelia Demerouti

Department of Industrial Engineering and Innovation Sciences – Human Performance Management Group, Eindhoven

University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Keywords

interpersonal conflict, emotions.

Correspondence

Sonja Rispens, Department of

Industrial Engineering and

Innovation Sciences – Human

Performance Management

Group, Eindhoven University of

Technology, PO Box 513, 5600

MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands;

e-mail: s.rispens@tue.nl.

Abstract

This study examines how daily conflictevents atwork affectpeople’s

active (anger,contempt) and passive (sadness,guilt) negative emotions

and in- and extra-role performance. We introduce the concept of confl

detachmentand examined whetherthis coping strategy alleviatesthe

degree of negative emotions a person feels due to a conflict experien

Sixty-two individuals from various professions in the Netherlands pro

vided questionnaire and daily survey measures during five consecutiv

workdays.Multilevel analyses showed that daily relationship and proce

conflict experiences at work were positively related to daily negative

tions. In addition, the results demonstrated a lagged effect of passive

ative emotions:feelings of guilt and sadness predicted lower in-role and

extra-role performance the following day.We also found thatconflict

detachment moderated the relationship between daily conflict and ne

tive emotions.We discuss the implications of our findings for organiza-

tional practice and suggest possible ways for future research.

It seems intuitive that experiencing workplace conflicts elicits negative emotions in people, ye

evidence is rather scarce (Nair,2007).Although some studies investigated the emotionalcorrelates of

workplace conflict, they mainly focused on anger (Jehn, Greer, Levine, & Szulanski, 2008; Risp

Spector and Bruk-Lee 2008).However,given the differentissues centralin workplace conflicts (i.e.,

regarding the task,the work process,or the relationship;Jehn,1997), it may be that different emotions

are triggered depending on what the conflict is about. Past work suggests conflicts are one of

stressors people face in the workplace (Hahn, 2000). What is even more, conflicts seem to be

in today’s organization because of an increasingly diversifying workforce and the accompanyin

ences in values and beliefs (cf.Dijkstra,Beersma,& Cornelissen,2012).In addition,past research sug-

gests emotions have important direct and indirect motivationalconsequences (Beal,Weiss,Barros,&

MacDermid, 2005; Rothbard & Wilk, 2011; Seo, Feldmann Barrett, & Bartunek, 2004) and nega

tions in particular have negative consequences for individuals’ motivation and behavior (BrowWest-

brook,& Challagalla,2005).Given the assumed negative emotions associated with workplace confl

experiences,the suspected rise of conflicts in the workplace,and the negative motivationaland perfor-

mance consequencesof negative emotions,we think itis paramountto investigate the relationship

between workplace conflict and emotions.

In general, conflict is defined as incompatibilities between two or more people (Boulding, 19

vious studies on workplace conflict have examined the consequences of general levels of confl

pointin time (see for a meta-analysis De Wit,Greer,& Jehn,2012) and did notfocus on people’s

responses to specific conflict events (for exceptions see Hahn,2000;Ilies,Johnson,Judge,& Keeney,

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119

© 2016 InternationalAssociation for Conflict Management and Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 103

Performance: A Diary Study

Sonja Rispens and Evangelia Demerouti

Department of Industrial Engineering and Innovation Sciences – Human Performance Management Group, Eindhoven

University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Keywords

interpersonal conflict, emotions.

Correspondence

Sonja Rispens, Department of

Industrial Engineering and

Innovation Sciences – Human

Performance Management

Group, Eindhoven University of

Technology, PO Box 513, 5600

MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands;

e-mail: s.rispens@tue.nl.

Abstract

This study examines how daily conflictevents atwork affectpeople’s

active (anger,contempt) and passive (sadness,guilt) negative emotions

and in- and extra-role performance. We introduce the concept of confl

detachmentand examined whetherthis coping strategy alleviatesthe

degree of negative emotions a person feels due to a conflict experien

Sixty-two individuals from various professions in the Netherlands pro

vided questionnaire and daily survey measures during five consecutiv

workdays.Multilevel analyses showed that daily relationship and proce

conflict experiences at work were positively related to daily negative

tions. In addition, the results demonstrated a lagged effect of passive

ative emotions:feelings of guilt and sadness predicted lower in-role and

extra-role performance the following day.We also found thatconflict

detachment moderated the relationship between daily conflict and ne

tive emotions.We discuss the implications of our findings for organiza-

tional practice and suggest possible ways for future research.

It seems intuitive that experiencing workplace conflicts elicits negative emotions in people, ye

evidence is rather scarce (Nair,2007).Although some studies investigated the emotionalcorrelates of

workplace conflict, they mainly focused on anger (Jehn, Greer, Levine, & Szulanski, 2008; Risp

Spector and Bruk-Lee 2008).However,given the differentissues centralin workplace conflicts (i.e.,

regarding the task,the work process,or the relationship;Jehn,1997), it may be that different emotions

are triggered depending on what the conflict is about. Past work suggests conflicts are one of

stressors people face in the workplace (Hahn, 2000). What is even more, conflicts seem to be

in today’s organization because of an increasingly diversifying workforce and the accompanyin

ences in values and beliefs (cf.Dijkstra,Beersma,& Cornelissen,2012).In addition,past research sug-

gests emotions have important direct and indirect motivationalconsequences (Beal,Weiss,Barros,&

MacDermid, 2005; Rothbard & Wilk, 2011; Seo, Feldmann Barrett, & Bartunek, 2004) and nega

tions in particular have negative consequences for individuals’ motivation and behavior (BrowWest-

brook,& Challagalla,2005).Given the assumed negative emotions associated with workplace confl

experiences,the suspected rise of conflicts in the workplace,and the negative motivationaland perfor-

mance consequencesof negative emotions,we think itis paramountto investigate the relationship

between workplace conflict and emotions.

In general, conflict is defined as incompatibilities between two or more people (Boulding, 19

vious studies on workplace conflict have examined the consequences of general levels of confl

pointin time (see for a meta-analysis De Wit,Greer,& Jehn,2012) and did notfocus on people’s

responses to specific conflict events (for exceptions see Hahn,2000;Ilies,Johnson,Judge,& Keeney,

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119

© 2016 InternationalAssociation for Conflict Management and Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 103

2011).That is unfortunate,because conflicts are omnipresent rather than rare episodes.Therefore,to

fully understand how conflict experiences affect employees, we propose to study people’s co

ences over time and close to its occurrence. To evaluate how far-reaching and possibly detrim

flicts are, our aim was to examine conflict experiences of employees during five consecutive

Given the often detrimentaleffects of conflict for individuals (De Wit et al.,2012),it is necessary to

examine factors thatmitigate these consequences.We examine whether mentally detaching from the

conflict situation (i.e., psychological conflict detachment) buffers the expected negative cons

conflict. Surprisingly, little is known about how people themselves manage workplace conflic

their occurrence.We believe that this is important to examine because learning how people red

tension closely after conflict occurrences generates new knowledge that guides developing i

interventions.

This study aimed to contribute to the literature in severalways.First,the within-person approach

allows gaining a deeper understanding of the psychologicalprocesses that are pivotalwhen employees

experience a conflict event and allows us to directly connect employees’responses to a specific conflict

event(i.e.,less recollection bias).Frameworks such as the affective events theory also highlightthe

importance of studying within-person experiences (Bealet al.,2005;Weiss & Cropanzano,1996).Sec-

ond, although it is widely assumed that workplace conflict stirs negative emotions, empirical

rather scarce.Furthermore,we examine whether different types of conflict bring about different e

tions and we therefore include two classes of negative emotions:passive and active negative emotions

(Russell & Barrett, 1999). Finally, we contribute to the existing body of research by examinin

ical conflict detachment as a coping strategy for conflict experiences at work.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Conflict and emotions

Past research on workplace conflict distinguished between task, relationship, and process co

Mannix,2001).Task conflicts are disagreements over task-related issues.An example is when two

coauthors disagree about the theoreticalframework for their study.Relationship conflicts are about

issues unrelated to the task that deal with personalvalues and issues (e.g.,politicalviews) underlying

people’s relationships in the workplace.Process conflicts dealwith logisticalissues related to the task

(e.g.,who is responsible for which task or when to schedule a meeting).This distinction is important

because different types of conflict have been related to different outcomes (cf.Jehn & Rispens,2008).

Although not often examined (Nair, 2007), workplace conflict is assumed to incite negative

(Jehn & Bendersky,2003).Workplace disagreements—even those about the task or work process

not just factual, but involve people’s perceptions of the facts and personal views about what

proceed (Yang & Mossholder,2004).Socialverification theory suggests that individuals interpret co

flicts aboutviewpoints,values,or beliefs as a negative taxation oftheir capabilities or personalities

(Swann, Polzer, Seyle, & Ko, 2004). For example, people may hear in a task conflict that thei

wrong,according to the opposing conflict party.Even when this comment is made neutrally,it may

threaten people’s positive self-view (i.e., being competent). Thus, conflicts likely increase pe

ences related to skills, personalities, or competencies, creating a threatening situation. And w

perceive situations as threatening,negative emotions and other stress reactions are likely (Blascovi

Tomaka, 1996).

Recently, researchers started recognizing the importance of studying emotional reactions t

conflict.Studies report that perceptions of a high level of conflict among coworkers are associ

increased negative emotions (Greer & Jehn, 2007; Todorova et al., 2014). Additionally, the fe

daily-levelconflict suggest conflict experience fluctuations are associated with fluctuations in n

affect(Bolger,DeLongis,Kessler,& Schilling,1989;Brissette & Cohen,2002;Ilies et al.,2011) and

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119104

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

fully understand how conflict experiences affect employees, we propose to study people’s co

ences over time and close to its occurrence. To evaluate how far-reaching and possibly detrim

flicts are, our aim was to examine conflict experiences of employees during five consecutive

Given the often detrimentaleffects of conflict for individuals (De Wit et al.,2012),it is necessary to

examine factors thatmitigate these consequences.We examine whether mentally detaching from the

conflict situation (i.e., psychological conflict detachment) buffers the expected negative cons

conflict. Surprisingly, little is known about how people themselves manage workplace conflic

their occurrence.We believe that this is important to examine because learning how people red

tension closely after conflict occurrences generates new knowledge that guides developing i

interventions.

This study aimed to contribute to the literature in severalways.First,the within-person approach

allows gaining a deeper understanding of the psychologicalprocesses that are pivotalwhen employees

experience a conflict event and allows us to directly connect employees’responses to a specific conflict

event(i.e.,less recollection bias).Frameworks such as the affective events theory also highlightthe

importance of studying within-person experiences (Bealet al.,2005;Weiss & Cropanzano,1996).Sec-

ond, although it is widely assumed that workplace conflict stirs negative emotions, empirical

rather scarce.Furthermore,we examine whether different types of conflict bring about different e

tions and we therefore include two classes of negative emotions:passive and active negative emotions

(Russell & Barrett, 1999). Finally, we contribute to the existing body of research by examinin

ical conflict detachment as a coping strategy for conflict experiences at work.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Conflict and emotions

Past research on workplace conflict distinguished between task, relationship, and process co

Mannix,2001).Task conflicts are disagreements over task-related issues.An example is when two

coauthors disagree about the theoreticalframework for their study.Relationship conflicts are about

issues unrelated to the task that deal with personalvalues and issues (e.g.,politicalviews) underlying

people’s relationships in the workplace.Process conflicts dealwith logisticalissues related to the task

(e.g.,who is responsible for which task or when to schedule a meeting).This distinction is important

because different types of conflict have been related to different outcomes (cf.Jehn & Rispens,2008).

Although not often examined (Nair, 2007), workplace conflict is assumed to incite negative

(Jehn & Bendersky,2003).Workplace disagreements—even those about the task or work process

not just factual, but involve people’s perceptions of the facts and personal views about what

proceed (Yang & Mossholder,2004).Socialverification theory suggests that individuals interpret co

flicts aboutviewpoints,values,or beliefs as a negative taxation oftheir capabilities or personalities

(Swann, Polzer, Seyle, & Ko, 2004). For example, people may hear in a task conflict that thei

wrong,according to the opposing conflict party.Even when this comment is made neutrally,it may

threaten people’s positive self-view (i.e., being competent). Thus, conflicts likely increase pe

ences related to skills, personalities, or competencies, creating a threatening situation. And w

perceive situations as threatening,negative emotions and other stress reactions are likely (Blascovi

Tomaka, 1996).

Recently, researchers started recognizing the importance of studying emotional reactions t

conflict.Studies report that perceptions of a high level of conflict among coworkers are associ

increased negative emotions (Greer & Jehn, 2007; Todorova et al., 2014). Additionally, the fe

daily-levelconflict suggest conflict experience fluctuations are associated with fluctuations in n

affect(Bolger,DeLongis,Kessler,& Schilling,1989;Brissette & Cohen,2002;Ilies et al.,2011) and

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119104

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

discrete emotions (Hahn,2000).Notably,only the work ofHahn (2000) and Ilies et al.(2011) have

examined workplace conflict,while Bolger et al.(1989) examined conflicts both at work and at home.

Based on the reviewed literature, we formulated the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Daily conflict (task, relationship, and process conflict) is positively related to d

tive emotions.

Coping with Conflict: Psychological Conflict Detachment

Conflicts are work stressors with substantial effects for the individual (Jex,1998);thus,it is essential to

investigate employees’strategies to minimize the costs ofconflict.People can apply cognitive and/or

behavioral strategies to manage the external demands of conflict (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988);

ple have different ways to cope with these stressors. We examined one such strategy namely

conflict detachment defined as the ability to mentally disconnect from the conflict event durin

time.

Our concept of conflict detachment is inspired by the concept of psychological detachment f

used in the literature on work stress and recovery (Sonnentag & Bayer, 2005). Detachment fro

defined as disengaging oneself from work and to stop thinking about job-related problems (So

Fritz,2007).Employees who apply the strategy ofpsychologicaldetachment are prevented from pro-

longed worry over stressfulevents (Sonnentag & Bayer,2005).In the current study,detachment refers

explicitly to workplace conflict experiences rather than stressful events in general. Rumination

conflict extends its negative effects (cf.Brosschot,Gerin,& Thayer,2006;McCullough,Orsulak,Bran-

don, & Akers, 2007), increasing the experienced negative emotions (Koole, Smeets, van Knipp

Dijksterhuis, 1999; Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). Rather, being able to mentally disconne

from the conflict situation should leave individuals with more cognitive resources and the abili

on their work tasks instead of the conflict. Conflict detachment means not engaging in fighting

nor searching for resolution and refraining from thinking excessively about the conflict.We think con-

flict detachment will decrease individuals’ level of negative emotions. Indeed, recent studies s

psychologicaldetachment from work is positively related to a positive mood at bedtime (Sonnen

Bayer, 2005) and seems a useful strategy to buffer the negative effects of job stressors on peo

logical strain (Sonnentag, Unger, & N€agel, 2013). Similarly, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between daily conflict and negative emotions is moderated b

logical conflict detachment, such that those who are able to detach themselves from the con

rience less negative emotions compared to those who cannot detach.

Negative Emotions and Performance

According to affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), negative emotions influence

als’ attitudes and behaviors more than positive emotions. Negative emotions are passing state

performance (Beal et al., 2005) and motivational consequences (Seo et al., 2004). People who

negative emotions are preoccupied with these emotions, and behaviors are triggered that aim

with these emotions (Weiss & Cropanzano,1996).Such behaviors (e.g.,revengefulacts,continuously

avoiding the other party) are incompatible with expected behaviors at work.

Active negative emotions trigger action tendencies toward an individual’s urge to preserve o

one’s self-esteem,whereas disgustenhances people’s impulse to eliminate the cause ofthe emotion

(Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, 2008). When caused by workplace conflict, attitudes and behavio

or contemptuousindividualsare focused on retaliation orrevengeand distracttime,effort,and

commitment from the task (cf. Jehn & Bendersky, 2003). Passive negative emotions, such as s

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 105

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

examined workplace conflict,while Bolger et al.(1989) examined conflicts both at work and at home.

Based on the reviewed literature, we formulated the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Daily conflict (task, relationship, and process conflict) is positively related to d

tive emotions.

Coping with Conflict: Psychological Conflict Detachment

Conflicts are work stressors with substantial effects for the individual (Jex,1998);thus,it is essential to

investigate employees’strategies to minimize the costs ofconflict.People can apply cognitive and/or

behavioral strategies to manage the external demands of conflict (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988);

ple have different ways to cope with these stressors. We examined one such strategy namely

conflict detachment defined as the ability to mentally disconnect from the conflict event durin

time.

Our concept of conflict detachment is inspired by the concept of psychological detachment f

used in the literature on work stress and recovery (Sonnentag & Bayer, 2005). Detachment fro

defined as disengaging oneself from work and to stop thinking about job-related problems (So

Fritz,2007).Employees who apply the strategy ofpsychologicaldetachment are prevented from pro-

longed worry over stressfulevents (Sonnentag & Bayer,2005).In the current study,detachment refers

explicitly to workplace conflict experiences rather than stressful events in general. Rumination

conflict extends its negative effects (cf.Brosschot,Gerin,& Thayer,2006;McCullough,Orsulak,Bran-

don, & Akers, 2007), increasing the experienced negative emotions (Koole, Smeets, van Knipp

Dijksterhuis, 1999; Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). Rather, being able to mentally disconne

from the conflict situation should leave individuals with more cognitive resources and the abili

on their work tasks instead of the conflict. Conflict detachment means not engaging in fighting

nor searching for resolution and refraining from thinking excessively about the conflict.We think con-

flict detachment will decrease individuals’ level of negative emotions. Indeed, recent studies s

psychologicaldetachment from work is positively related to a positive mood at bedtime (Sonnen

Bayer, 2005) and seems a useful strategy to buffer the negative effects of job stressors on peo

logical strain (Sonnentag, Unger, & N€agel, 2013). Similarly, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between daily conflict and negative emotions is moderated b

logical conflict detachment, such that those who are able to detach themselves from the con

rience less negative emotions compared to those who cannot detach.

Negative Emotions and Performance

According to affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), negative emotions influence

als’ attitudes and behaviors more than positive emotions. Negative emotions are passing state

performance (Beal et al., 2005) and motivational consequences (Seo et al., 2004). People who

negative emotions are preoccupied with these emotions, and behaviors are triggered that aim

with these emotions (Weiss & Cropanzano,1996).Such behaviors (e.g.,revengefulacts,continuously

avoiding the other party) are incompatible with expected behaviors at work.

Active negative emotions trigger action tendencies toward an individual’s urge to preserve o

one’s self-esteem,whereas disgustenhances people’s impulse to eliminate the cause ofthe emotion

(Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, 2008). When caused by workplace conflict, attitudes and behavio

or contemptuousindividualsare focused on retaliation orrevengeand distracttime,effort,and

commitment from the task (cf. Jehn & Bendersky, 2003). Passive negative emotions, such as s

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 105

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

guilt,activate withdrawaland disengagement(when feeling sad) or pondering the conflictsituation

(when feeling guilty). Conflict threatens a collaborative relationship, and the sadness and gu

may induce thinking abouthow to alter their personalcircumstances(Ashton-James& Ashkanasy,

2008), which also occurs at the costs of attention and effort invested in the task.

Additionally,we expect negative emotions to be negatively related to extra-role performanceExtra-

role performance is defined as the discretionary behaviors performed by an employee that a

promote the effective functioning of an organization (e.g., organizational citizenship behavio

initiative, constructive voice behavior; Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010). Negative emotions m

fairness perceptions (Weiss & Cropanzano,1996),and research on extra-role performance has under

scored the importance of fairness;people who feelfairly treated are more likely to perform extra-role

behaviors than people who do not feelfairly treated (Organ,1990).Indeed,negative emotions predict

deviant behaviors (Lee & Allen, 2002), specifically active negative emotions. In general, peop

toward conflict experiences includes disengagement or revenge behaviors (Fitness, 2000) ra

forming beyond one’s job description.Therefore,we expecta negative relationship between negative

emotions and in-role and extra-role performance:

Hypothesis 3a:Daily negative emotions are negatively associated with daily in-role and extra

performance.

In addition,we hypothesize lagged effects of negative emotions on performance.Day-levelresearch

suggests thatexperiences during 1 day can impactbehaviors the following day (Fritz & Sonnentag,

2009). The reason why someone felt angry (i.e., the other conflict party) is likely to still be th

day; therefore, the negative emotions raised yesterday may be reactivated the following day

distracting attention and energy from the tasks. People who felt sad or guilty because of the

yesterday may still ruminate about how to repair the damaged relationship the following day

who felt angry may have lost sleep or other recovery opportunities after work because of the

plotting revenge strategies to restore perceived injustice.Indeed,research has suggested that conflicts

experienced at work inhibit recovery from work (Volmer,Binnewies,Sonnentag,& Niessen,2012) and

deteriorate sleep quality (Thomsen,Mehlsen,Christensen,& Zachariae,2003).Therefore,we expect a

lagged effect of negative emotions on the in-role and extra-role performance of the following

ted formally:

Hypothesis 3b: Negative emotions of the previous day negatively affect individuals’ in-role

role performance the next day.

Regarding negative emotions, we explore whether all types of conflict elicit identical negat

(as suggested in past conflict research) or that differences are possible depending on the typ

The literature distinguishes between passive and active negative emotions (Russell& Barrett,1999).

Active negative emotions activate a sense of mobilization or energy (e.g.,anger or contempt) whereas

passive negative emotions are not associated with high levels of energy (e.g., sadness or gu

its approach tendencies (Carver & Harmon-Jones,2009),and contempt typically increases activities to

socially exclude the other party such as gossiping or slandering (Fischer & Roseman, 2007).

guilt,on the other hand,do not increase arousal(Shields,1984) rather they inhibit ongoing behavior.

We think thatboth types ofnegative emotions can occur in the face ofconflictand are interested

whether the experience of emotions is dependent upon the conflict type. Lacking theoretical

empiricalevidence that link specific negative emotions to specific conflict types,we willonly explore

whether different negative emotional responses depend on the type of daily conflict. To state

RQ 1: Do different types of conflict trigger different negative emotional responses?

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119106

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

(when feeling guilty). Conflict threatens a collaborative relationship, and the sadness and gu

may induce thinking abouthow to alter their personalcircumstances(Ashton-James& Ashkanasy,

2008), which also occurs at the costs of attention and effort invested in the task.

Additionally,we expect negative emotions to be negatively related to extra-role performanceExtra-

role performance is defined as the discretionary behaviors performed by an employee that a

promote the effective functioning of an organization (e.g., organizational citizenship behavio

initiative, constructive voice behavior; Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010). Negative emotions m

fairness perceptions (Weiss & Cropanzano,1996),and research on extra-role performance has under

scored the importance of fairness;people who feelfairly treated are more likely to perform extra-role

behaviors than people who do not feelfairly treated (Organ,1990).Indeed,negative emotions predict

deviant behaviors (Lee & Allen, 2002), specifically active negative emotions. In general, peop

toward conflict experiences includes disengagement or revenge behaviors (Fitness, 2000) ra

forming beyond one’s job description.Therefore,we expecta negative relationship between negative

emotions and in-role and extra-role performance:

Hypothesis 3a:Daily negative emotions are negatively associated with daily in-role and extra

performance.

In addition,we hypothesize lagged effects of negative emotions on performance.Day-levelresearch

suggests thatexperiences during 1 day can impactbehaviors the following day (Fritz & Sonnentag,

2009). The reason why someone felt angry (i.e., the other conflict party) is likely to still be th

day; therefore, the negative emotions raised yesterday may be reactivated the following day

distracting attention and energy from the tasks. People who felt sad or guilty because of the

yesterday may still ruminate about how to repair the damaged relationship the following day

who felt angry may have lost sleep or other recovery opportunities after work because of the

plotting revenge strategies to restore perceived injustice.Indeed,research has suggested that conflicts

experienced at work inhibit recovery from work (Volmer,Binnewies,Sonnentag,& Niessen,2012) and

deteriorate sleep quality (Thomsen,Mehlsen,Christensen,& Zachariae,2003).Therefore,we expect a

lagged effect of negative emotions on the in-role and extra-role performance of the following

ted formally:

Hypothesis 3b: Negative emotions of the previous day negatively affect individuals’ in-role

role performance the next day.

Regarding negative emotions, we explore whether all types of conflict elicit identical negat

(as suggested in past conflict research) or that differences are possible depending on the typ

The literature distinguishes between passive and active negative emotions (Russell& Barrett,1999).

Active negative emotions activate a sense of mobilization or energy (e.g.,anger or contempt) whereas

passive negative emotions are not associated with high levels of energy (e.g., sadness or gu

its approach tendencies (Carver & Harmon-Jones,2009),and contempt typically increases activities to

socially exclude the other party such as gossiping or slandering (Fischer & Roseman, 2007).

guilt,on the other hand,do not increase arousal(Shields,1984) rather they inhibit ongoing behavior.

We think thatboth types ofnegative emotions can occur in the face ofconflictand are interested

whether the experience of emotions is dependent upon the conflict type. Lacking theoretical

empiricalevidence that link specific negative emotions to specific conflict types,we willonly explore

whether different negative emotional responses depend on the type of daily conflict. To state

RQ 1: Do different types of conflict trigger different negative emotional responses?

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119106

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

Method

Procedure and Sample

Participantswere employeesfrom variousDutch organizations.Suitable participantswere 18 years

or olderand partof the paid laborforce.Research assistantsrecruited the participantsand dis-

tributed questionnairesand diariesvia theirpersonalcontacts,which guaranteed heterogeneity of

the sample.Participantsreceived a packagethat included a letterexplaining thepurposeof the

study and assuring anonymity and confidentiality oftheirresponses,instructionsaboutthe com-

pletion ofthe surveys,a generalquestionnaire,a diary questionnaire,and a return envelope.Par-

ticipation was voluntary.

Participants first filled in the generalquestionnaire,after which they completed the daily question-

naires for five consecutive workdays (at the end of their workday).Sixty-four participants returned the

packages. Because of incomplete data (missing 3 or more daily questionnaires), the responses

were removed,resulting in a finalsample of62 respondents.This sample size is sufficient because it

exceeds the minimum of 50 observations on Level 2 (Maas & Hox, 2005).

The majority ofthe participantswasmale (53.9%),and respondents’average age was36 years

(SD = 12.27).Most respondents worked in the financialsector (17%),business services (14%),or the

educationalsector (12%).On average,respondents had 14 years of work experience (SD = 10.64) an

worked 35.4 hr per week (SD = 11.01).

General Questionnaire Measures

Participants completed a general questionnaire before the daily surveys. In the general questi

asked respondents about their demographic background.

Daily Questionnaire Measures

To keep the daily surveys as shortas possible,we used abbreviated scales and single-item measures

which is common practice in diary study research (Ohly, Sonnentag, Niessen, & Zapf, 2010). R

were given on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 = not true at all, 5 = totally true) except for the res

the daily in-role and extra-role performance scales which were given on a 7-point Likert scale

all, 6 = very much).

Conflict Types

Respondents first read an introduction (following Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001) that resp

can help to understand how often conflicts occur,what conflicts are about,and how conflicts are dealt

with.We then told that conflicts are not necessarily bad and that they can be functionalin helping to

understand others as well as ourselves.We also told participants that conflicts vary between differenc

of opinion to full-blown fights. We measured whether participants experienced a task conflict,

ship conflict,or a process conflict during their workday.Following earlier research (Hahn,2000;Van

Doorn,Branje,Hox,& Meeus,2009),we used one item for each of the types of Jehn’s (1995;Jehn &

Mannix, 2001) conflict typology. We introduced each type of conflict before presenting the item

ing Jehn et al.,2008).The items for task,relationship,and process conflict were “It was a task-related

conflict,” “We disagreed about personal issues,” and “We disagreed on how to do the task,” re

Conflict Detachment

We measured participants’ability to detach themselves mentally from the conflict soon after the ev

occurred and during working hours with the following items based on Sonnentag and Fritz’s (2

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 107

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Procedure and Sample

Participantswere employeesfrom variousDutch organizations.Suitable participantswere 18 years

or olderand partof the paid laborforce.Research assistantsrecruited the participantsand dis-

tributed questionnairesand diariesvia theirpersonalcontacts,which guaranteed heterogeneity of

the sample.Participantsreceived a packagethat included a letterexplaining thepurposeof the

study and assuring anonymity and confidentiality oftheirresponses,instructionsaboutthe com-

pletion ofthe surveys,a generalquestionnaire,a diary questionnaire,and a return envelope.Par-

ticipation was voluntary.

Participants first filled in the generalquestionnaire,after which they completed the daily question-

naires for five consecutive workdays (at the end of their workday).Sixty-four participants returned the

packages. Because of incomplete data (missing 3 or more daily questionnaires), the responses

were removed,resulting in a finalsample of62 respondents.This sample size is sufficient because it

exceeds the minimum of 50 observations on Level 2 (Maas & Hox, 2005).

The majority ofthe participantswasmale (53.9%),and respondents’average age was36 years

(SD = 12.27).Most respondents worked in the financialsector (17%),business services (14%),or the

educationalsector (12%).On average,respondents had 14 years of work experience (SD = 10.64) an

worked 35.4 hr per week (SD = 11.01).

General Questionnaire Measures

Participants completed a general questionnaire before the daily surveys. In the general questi

asked respondents about their demographic background.

Daily Questionnaire Measures

To keep the daily surveys as shortas possible,we used abbreviated scales and single-item measures

which is common practice in diary study research (Ohly, Sonnentag, Niessen, & Zapf, 2010). R

were given on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 = not true at all, 5 = totally true) except for the res

the daily in-role and extra-role performance scales which were given on a 7-point Likert scale

all, 6 = very much).

Conflict Types

Respondents first read an introduction (following Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001) that resp

can help to understand how often conflicts occur,what conflicts are about,and how conflicts are dealt

with.We then told that conflicts are not necessarily bad and that they can be functionalin helping to

understand others as well as ourselves.We also told participants that conflicts vary between differenc

of opinion to full-blown fights. We measured whether participants experienced a task conflict,

ship conflict,or a process conflict during their workday.Following earlier research (Hahn,2000;Van

Doorn,Branje,Hox,& Meeus,2009),we used one item for each of the types of Jehn’s (1995;Jehn &

Mannix, 2001) conflict typology. We introduced each type of conflict before presenting the item

ing Jehn et al.,2008).The items for task,relationship,and process conflict were “It was a task-related

conflict,” “We disagreed about personal issues,” and “We disagreed on how to do the task,” re

Conflict Detachment

We measured participants’ability to detach themselves mentally from the conflict soon after the ev

occurred and during working hours with the following items based on Sonnentag and Fritz’s (2

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 107

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

detachment from work scale: “Because of my work I forgot about the conflict I experienced t

to my work I did not think about the conflict I experienced today”;and “My work enabled me to dis-

tance myself from the conflict I experienced today”. The Cronbach’s a = .89.

In-Role Performance

We used two items to measure in-role performance (Xanthopoulou,Bakker,Heuven,Demerouti,&

Schaufeli, 2008): “Today, I have performed well” and “Today, I achieved the objectives of my

correlation between these items was r = .62, p < .001, and the Cronbach’s a = .76.

Extra-Role Performance

We measured participants’ extra-role performance with two items (Xanthopoulou et al., 2008

I volunteered to take on extra work” and “Today,I helped colleagues who had too much work to do.”

The correlation between these items was r = .43, p < .001, and the Cronbach’s a = .60.

Negative Emotions

We asked respondentshow they feltabouttheiropponentat the end oftheirwork day.Respon-

dentsindicated on a 5-pointscale (1 = completely disagree,5 = completely agree)how much they

feltcontempt,anger,guilt,or sadnessanswering the question “When Ithink aboutthe conflicting

party now,I feel. . .”.We performed an exploratory factoranalysiswhich indicated thattwo fac-

tors bestrepresented thisdata.The factorloading fordaily contemptwas.81 and fordaily anger

.76 on factor1 (active negativeemotions);for daily sadness.85 and daily guilt.56 on factor2

(passive negative emotions).The active negative emotionsfactoraccounted for58.3% ofthe vari-

anceand thepassivenegativeemotionsfactorexplained an additional20.6% ofthe variancein

our data.We combined sadnessand guilt(r = .51,p < .001;Cronbach’sa = .67)and contempt

and anger(r = .64,p < .001;Cronbach’sa = .77)to create passive and active negative emotions,

respectively.

Control Variables

There is the possibility that conflict gets resolved quickly which minimizes respondents’negative emo-

tions (Kross,Ayduk,& Mischel,2005).Additionally,time spent resolving the issue and repairing the

relationship may distract time and effort otherwise invested in task execution (Jehn & Bende

Therefore,we controlled for daily conflict resolution.Conflict resolution was measured with one item:

“The conflict has been completely resolved” (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree

we controlled for whether the conflict respondents experienced was with their supervisor (or

boss) or not.Studies have suggested that conflicts with supervisors may spur task effort (Fitne2000;

Sy, Cote,& Saavedra,2005).We also controlled forthe person-levelvariablestenure and gender

(Dijkstra, Beersma, & Evers, 2011; Jehn, 1995).

We performed a Harman’s single factor test which revealed that a single factor did not acc

majority of the variance in our data, thereby alleviating potential concerns about single sourc

Analytical Strategy

Our data have a hierarchicalstructure.Level1 is composed of data collected at the day-levelwhereas

Level 2 is composed of measurements at the person-level. Day-level data are nested within p

the appropriate approach is multilevelanalysis (Bryk & Raudenbush,1992),and we used the MLwiN

program (Rashbash, Browne, Healy, Cameron, & Charlton, 2000). We centered predictor vari

day level around the respective person mean.

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119108

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

to my work I did not think about the conflict I experienced today”;and “My work enabled me to dis-

tance myself from the conflict I experienced today”. The Cronbach’s a = .89.

In-Role Performance

We used two items to measure in-role performance (Xanthopoulou,Bakker,Heuven,Demerouti,&

Schaufeli, 2008): “Today, I have performed well” and “Today, I achieved the objectives of my

correlation between these items was r = .62, p < .001, and the Cronbach’s a = .76.

Extra-Role Performance

We measured participants’ extra-role performance with two items (Xanthopoulou et al., 2008

I volunteered to take on extra work” and “Today,I helped colleagues who had too much work to do.”

The correlation between these items was r = .43, p < .001, and the Cronbach’s a = .60.

Negative Emotions

We asked respondentshow they feltabouttheiropponentat the end oftheirwork day.Respon-

dentsindicated on a 5-pointscale (1 = completely disagree,5 = completely agree)how much they

feltcontempt,anger,guilt,or sadnessanswering the question “When Ithink aboutthe conflicting

party now,I feel. . .”.We performed an exploratory factoranalysiswhich indicated thattwo fac-

tors bestrepresented thisdata.The factorloading fordaily contemptwas.81 and fordaily anger

.76 on factor1 (active negativeemotions);for daily sadness.85 and daily guilt.56 on factor2

(passive negative emotions).The active negative emotionsfactoraccounted for58.3% ofthe vari-

anceand thepassivenegativeemotionsfactorexplained an additional20.6% ofthe variancein

our data.We combined sadnessand guilt(r = .51,p < .001;Cronbach’sa = .67)and contempt

and anger(r = .64,p < .001;Cronbach’sa = .77)to create passive and active negative emotions,

respectively.

Control Variables

There is the possibility that conflict gets resolved quickly which minimizes respondents’negative emo-

tions (Kross,Ayduk,& Mischel,2005).Additionally,time spent resolving the issue and repairing the

relationship may distract time and effort otherwise invested in task execution (Jehn & Bende

Therefore,we controlled for daily conflict resolution.Conflict resolution was measured with one item:

“The conflict has been completely resolved” (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree

we controlled for whether the conflict respondents experienced was with their supervisor (or

boss) or not.Studies have suggested that conflicts with supervisors may spur task effort (Fitne2000;

Sy, Cote,& Saavedra,2005).We also controlled forthe person-levelvariablestenure and gender

(Dijkstra, Beersma, & Evers, 2011; Jehn, 1995).

We performed a Harman’s single factor test which revealed that a single factor did not acc

majority of the variance in our data, thereby alleviating potential concerns about single sourc

Analytical Strategy

Our data have a hierarchicalstructure.Level1 is composed of data collected at the day-levelwhereas

Level 2 is composed of measurements at the person-level. Day-level data are nested within p

the appropriate approach is multilevelanalysis (Bryk & Raudenbush,1992),and we used the MLwiN

program (Rashbash, Browne, Healy, Cameron, & Charlton, 2000). We centered predictor vari

day level around the respective person mean.

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119108

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Results

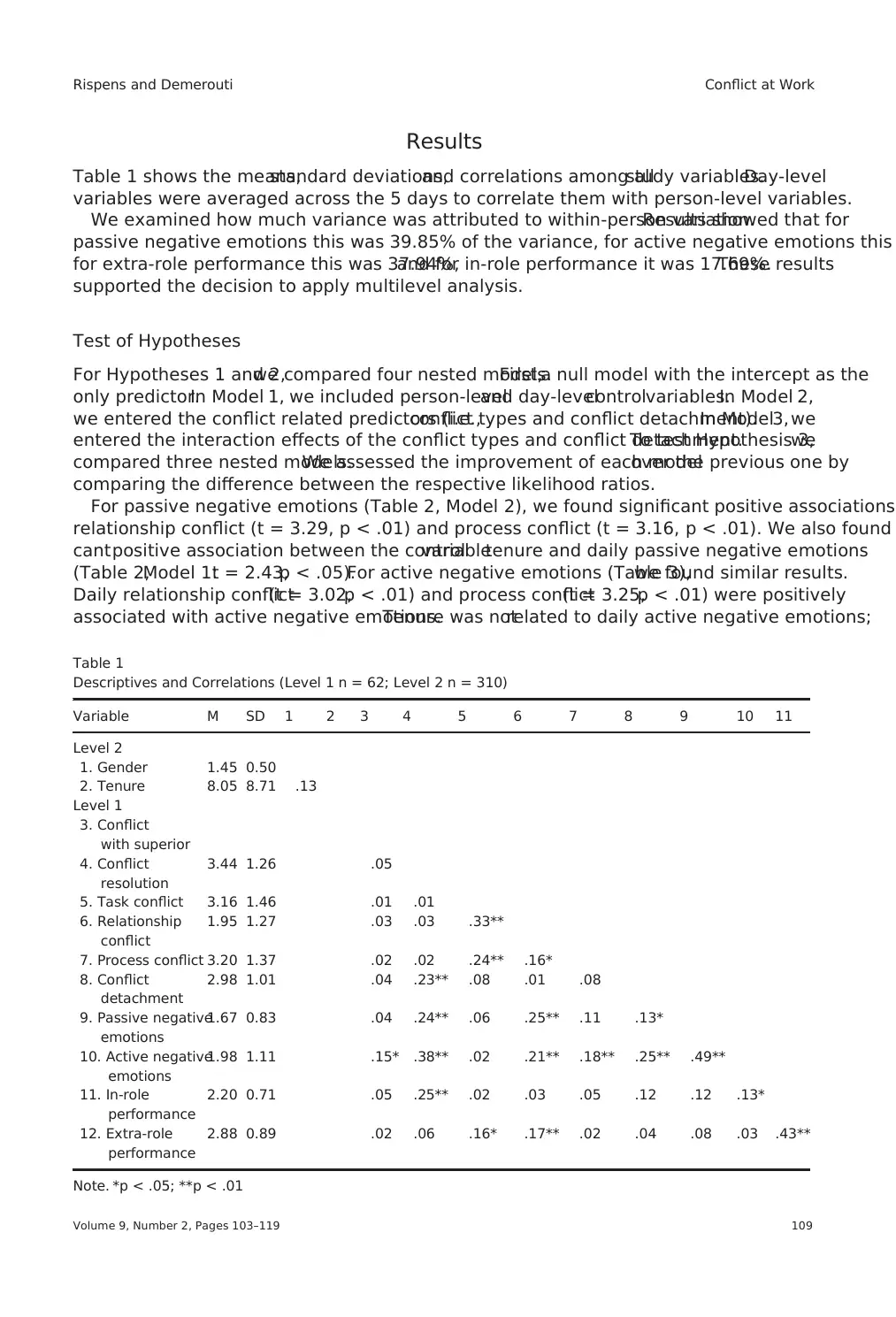

Table 1 shows the means,standard deviations,and correlations among allstudy variables.Day-level

variables were averaged across the 5 days to correlate them with person-level variables.

We examined how much variance was attributed to within-person variation.Results showed that for

passive negative emotions this was 39.85% of the variance, for active negative emotions this

for extra-role performance this was 37.94%,and for in-role performance it was 17.69%.These results

supported the decision to apply multilevel analysis.

Test of Hypotheses

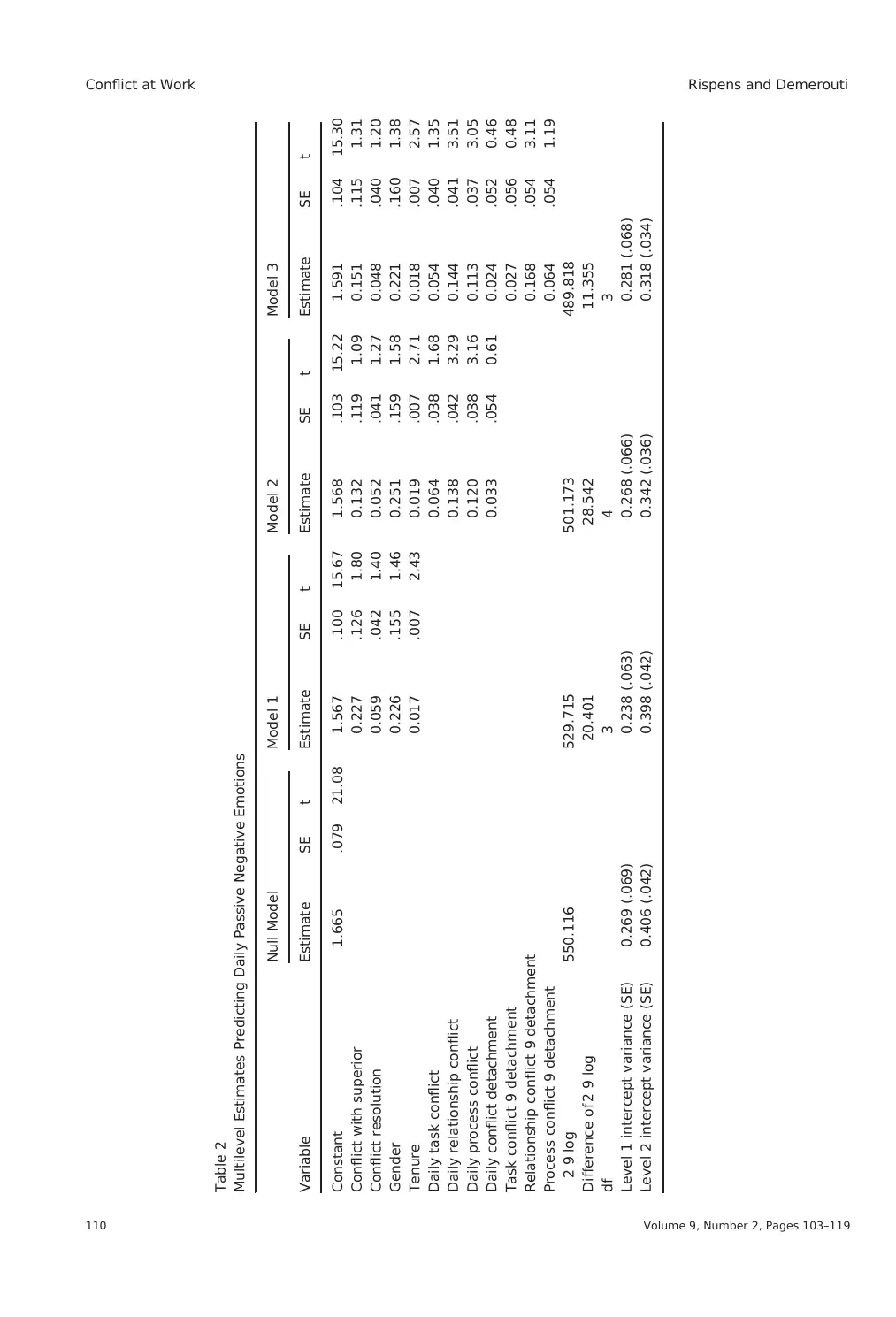

For Hypotheses 1 and 2,we compared four nested models.First,a null model with the intercept as the

only predictor.In Model 1, we included person-leveland day-levelcontrolvariables.In Model 2,

we entered the conflict related predictors (i.e.,conflict types and conflict detachment).In Model3, we

entered the interaction effects of the conflict types and conflict detachment.To test Hypothesis 3,we

compared three nested models.We assessed the improvement of each modelover the previous one by

comparing the difference between the respective likelihood ratios.

For passive negative emotions (Table 2, Model 2), we found significant positive associations

relationship conflict (t = 3.29, p < .01) and process conflict (t = 3.16, p < .01). We also found

cantpositive association between the controlvariabletenure and daily passive negative emotions

(Table 2,Model 1:t = 2.43,p < .05).For active negative emotions (Table 3),we found similar results.

Daily relationship conflict(t = 3.02,p < .01) and process conflict(t = 3.25,p < .01) were positively

associated with active negative emotions.Tenure was notrelated to daily active negative emotions;

Table 1

Descriptives and Correlations (Level 1 n = 62; Level 2 n = 310)

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Level 2

1. Gender 1.45 0.50

2. Tenure 8.05 8.71 .13

Level 1

3. Conflict

with superior

4. Conflict

resolution

3.44 1.26 .05

5. Task conflict 3.16 1.46 .01 .01

6. Relationship

conflict

1.95 1.27 .03 .03 .33**

7. Process conflict 3.20 1.37 .02 .02 .24** .16*

8. Conflict

detachment

2.98 1.01 .04 .23** .08 .01 .08

9. Passive negative

emotions

1.67 0.83 .04 .24** .06 .25** .11 .13*

10. Active negative

emotions

1.98 1.11 .15* .38** .02 .21** .18** .25** .49**

11. In-role

performance

2.20 0.71 .05 .25** .02 .03 .05 .12 .12 .13*

12. Extra-role

performance

2.88 0.89 .02 .06 .16* .17** .02 .04 .08 .03 .43**

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 109

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Table 1 shows the means,standard deviations,and correlations among allstudy variables.Day-level

variables were averaged across the 5 days to correlate them with person-level variables.

We examined how much variance was attributed to within-person variation.Results showed that for

passive negative emotions this was 39.85% of the variance, for active negative emotions this

for extra-role performance this was 37.94%,and for in-role performance it was 17.69%.These results

supported the decision to apply multilevel analysis.

Test of Hypotheses

For Hypotheses 1 and 2,we compared four nested models.First,a null model with the intercept as the

only predictor.In Model 1, we included person-leveland day-levelcontrolvariables.In Model 2,

we entered the conflict related predictors (i.e.,conflict types and conflict detachment).In Model3, we

entered the interaction effects of the conflict types and conflict detachment.To test Hypothesis 3,we

compared three nested models.We assessed the improvement of each modelover the previous one by

comparing the difference between the respective likelihood ratios.

For passive negative emotions (Table 2, Model 2), we found significant positive associations

relationship conflict (t = 3.29, p < .01) and process conflict (t = 3.16, p < .01). We also found

cantpositive association between the controlvariabletenure and daily passive negative emotions

(Table 2,Model 1:t = 2.43,p < .05).For active negative emotions (Table 3),we found similar results.

Daily relationship conflict(t = 3.02,p < .01) and process conflict(t = 3.25,p < .01) were positively

associated with active negative emotions.Tenure was notrelated to daily active negative emotions;

Table 1

Descriptives and Correlations (Level 1 n = 62; Level 2 n = 310)

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Level 2

1. Gender 1.45 0.50

2. Tenure 8.05 8.71 .13

Level 1

3. Conflict

with superior

4. Conflict

resolution

3.44 1.26 .05

5. Task conflict 3.16 1.46 .01 .01

6. Relationship

conflict

1.95 1.27 .03 .03 .33**

7. Process conflict 3.20 1.37 .02 .02 .24** .16*

8. Conflict

detachment

2.98 1.01 .04 .23** .08 .01 .08

9. Passive negative

emotions

1.67 0.83 .04 .24** .06 .25** .11 .13*

10. Active negative

emotions

1.98 1.11 .15* .38** .02 .21** .18** .25** .49**

11. In-role

performance

2.20 0.71 .05 .25** .02 .03 .05 .12 .12 .13*

12. Extra-role

performance

2.88 0.89 .02 .06 .16* .17** .02 .04 .08 .03 .43**

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 109

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Table 2

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Passive Negative Emotions

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 1.665 .079 21.08 1.567 .100 15.67 1.568 .103 15.22 1.591 .104 15.30

Conflict with superior 0.227 .126 1.80 0.132 .119 1.09 0.151 .115 1.31

Conflict resolution 0.059 .042 1.40 0.052 .041 1.27 0.048 .040 1.20

Gender 0.226 .155 1.46 0.251 .159 1.58 0.221 .160 1.38

Tenure 0.017 .007 2.43 0.019 .007 2.71 0.018 .007 2.57

Daily task conflict 0.064 .038 1.68 0.054 .040 1.35

Daily relationship conflict 0.138 .042 3.29 0.144 .041 3.51

Daily process conflict 0.120 .038 3.16 0.113 .037 3.05

Daily conflict detachment 0.033 .054 0.61 0.024 .052 0.46

Task conflict 9 detachment 0.027 .056 0.48

Relationship conflict 9 detachment 0.168 .054 3.11

Process conflict 9 detachment 0.064 .054 1.19

2 9 log 550.116 529.715 501.173 489.818

Difference of 2 9 log 20.401 28.542 11.355

df 3 4 3

Level 1 intercept variance (SE) 0.269 (.069) 0.238 (.063) 0.268 (.066) 0.281 (.068)

Level 2 intercept variance (SE) 0.406 (.042) 0.398 (.042) 0.342 (.036) 0.318 (.034)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119110

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Passive Negative Emotions

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 1.665 .079 21.08 1.567 .100 15.67 1.568 .103 15.22 1.591 .104 15.30

Conflict with superior 0.227 .126 1.80 0.132 .119 1.09 0.151 .115 1.31

Conflict resolution 0.059 .042 1.40 0.052 .041 1.27 0.048 .040 1.20

Gender 0.226 .155 1.46 0.251 .159 1.58 0.221 .160 1.38

Tenure 0.017 .007 2.43 0.019 .007 2.71 0.018 .007 2.57

Daily task conflict 0.064 .038 1.68 0.054 .040 1.35

Daily relationship conflict 0.138 .042 3.29 0.144 .041 3.51

Daily process conflict 0.120 .038 3.16 0.113 .037 3.05

Daily conflict detachment 0.033 .054 0.61 0.024 .052 0.46

Task conflict 9 detachment 0.027 .056 0.48

Relationship conflict 9 detachment 0.168 .054 3.11

Process conflict 9 detachment 0.064 .054 1.19

2 9 log 550.116 529.715 501.173 489.818

Difference of 2 9 log 20.401 28.542 11.355

df 3 4 3

Level 1 intercept variance (SE) 0.269 (.069) 0.238 (.063) 0.268 (.066) 0.281 (.068)

Level 2 intercept variance (SE) 0.406 (.042) 0.398 (.042) 0.342 (.036) 0.318 (.034)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119110

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

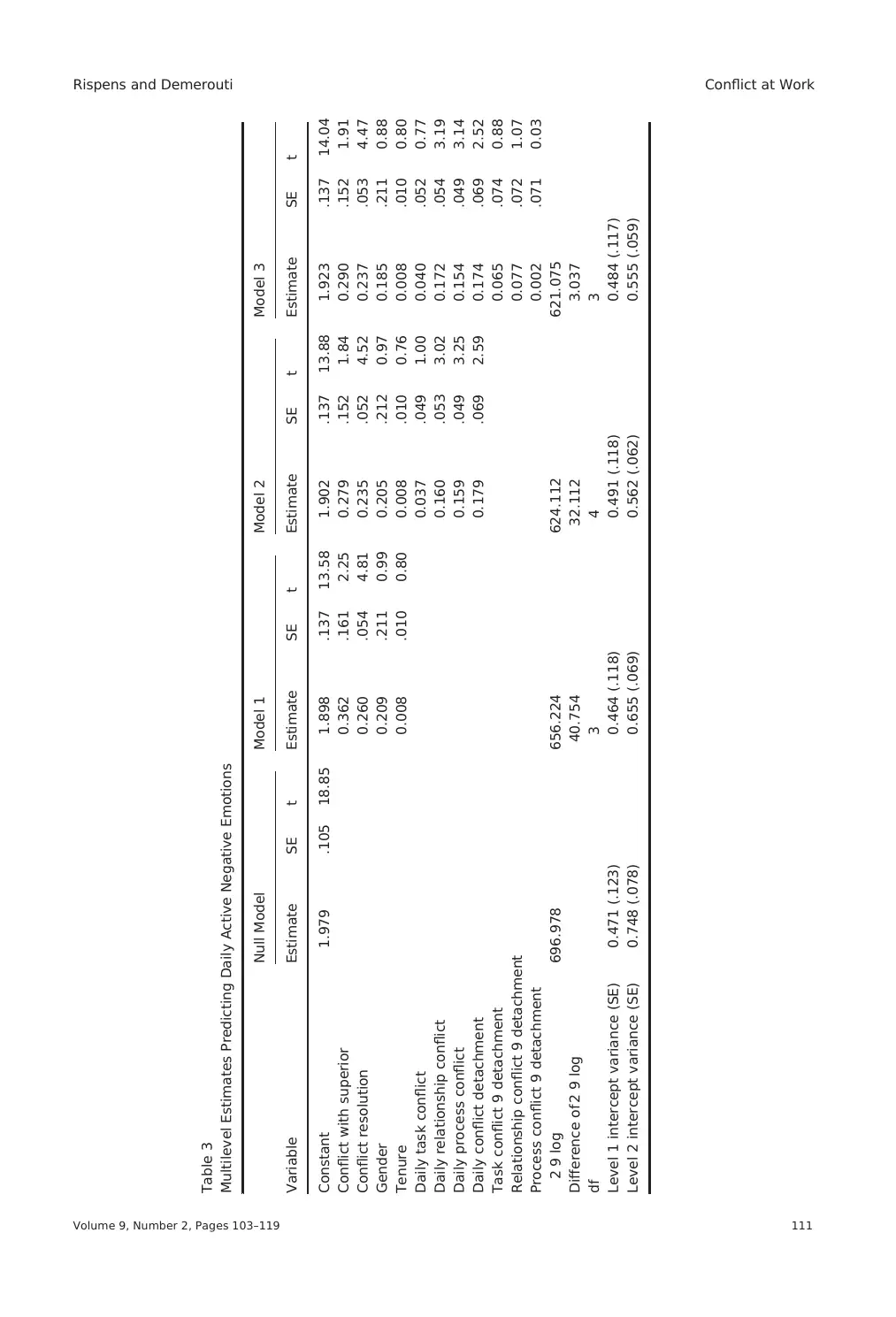

Table 3

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Active Negative Emotions

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 1.979 .105 18.85 1.898 .137 13.58 1.902 .137 13.88 1.923 .137 14.04

Conflict with superior 0.362 .161 2.25 0.279 .152 1.84 0.290 .152 1.91

Conflict resolution 0.260 .054 4.81 0.235 .052 4.52 0.237 .053 4.47

Gender 0.209 .211 0.99 0.205 .212 0.97 0.185 .211 0.88

Tenure 0.008 .010 0.80 0.008 .010 0.76 0.008 .010 0.80

Daily task conflict 0.037 .049 1.00 0.040 .052 0.77

Daily relationship conflict 0.160 .053 3.02 0.172 .054 3.19

Daily process conflict 0.159 .049 3.25 0.154 .049 3.14

Daily conflict detachment 0.179 .069 2.59 0.174 .069 2.52

Task conflict 9 detachment 0.065 .074 0.88

Relationship conflict 9 detachment 0.077 .072 1.07

Process conflict 9 detachment 0.002 .071 0.03

2 9 log 696.978 656.224 624.112 621.075

Difference of 2 9 log 40.754 32.112 3.037

df 3 4 3

Level 1 intercept variance (SE) 0.471 (.123) 0.464 (.118) 0.491 (.118) 0.484 (.117)

Level 2 intercept variance (SE) 0.748 (.078) 0.655 (.069) 0.562 (.062) 0.555 (.059)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 111

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Active Negative Emotions

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 1.979 .105 18.85 1.898 .137 13.58 1.902 .137 13.88 1.923 .137 14.04

Conflict with superior 0.362 .161 2.25 0.279 .152 1.84 0.290 .152 1.91

Conflict resolution 0.260 .054 4.81 0.235 .052 4.52 0.237 .053 4.47

Gender 0.209 .211 0.99 0.205 .212 0.97 0.185 .211 0.88

Tenure 0.008 .010 0.80 0.008 .010 0.76 0.008 .010 0.80

Daily task conflict 0.037 .049 1.00 0.040 .052 0.77

Daily relationship conflict 0.160 .053 3.02 0.172 .054 3.19

Daily process conflict 0.159 .049 3.25 0.154 .049 3.14

Daily conflict detachment 0.179 .069 2.59 0.174 .069 2.52

Task conflict 9 detachment 0.065 .074 0.88

Relationship conflict 9 detachment 0.077 .072 1.07

Process conflict 9 detachment 0.002 .071 0.03

2 9 log 696.978 656.224 624.112 621.075

Difference of 2 9 log 40.754 32.112 3.037

df 3 4 3

Level 1 intercept variance (SE) 0.471 (.123) 0.464 (.118) 0.491 (.118) 0.484 (.117)

Level 2 intercept variance (SE) 0.748 (.078) 0.655 (.069) 0.562 (.062) 0.555 (.059)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 111

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

however,conflict resolution was negatively related to daily active negative emotions (Table 2,Model 1;

t = 4.81, p < .01). These findings largely confirm Hypothesis 1: Daily relationship and proce

are related to an increase in daily active and passive negative emotions.

These results also answer our Research Question whether different types of conflict stir diff

of negative emotions. We found no relationship between daily task conflict and negative emo

ever,relationship and process conflicts were both positively related to passive as well as activ

emotions.Thus,we did not find strong evidence that different types of daily conflict prompt diff

classes of negative emotions.

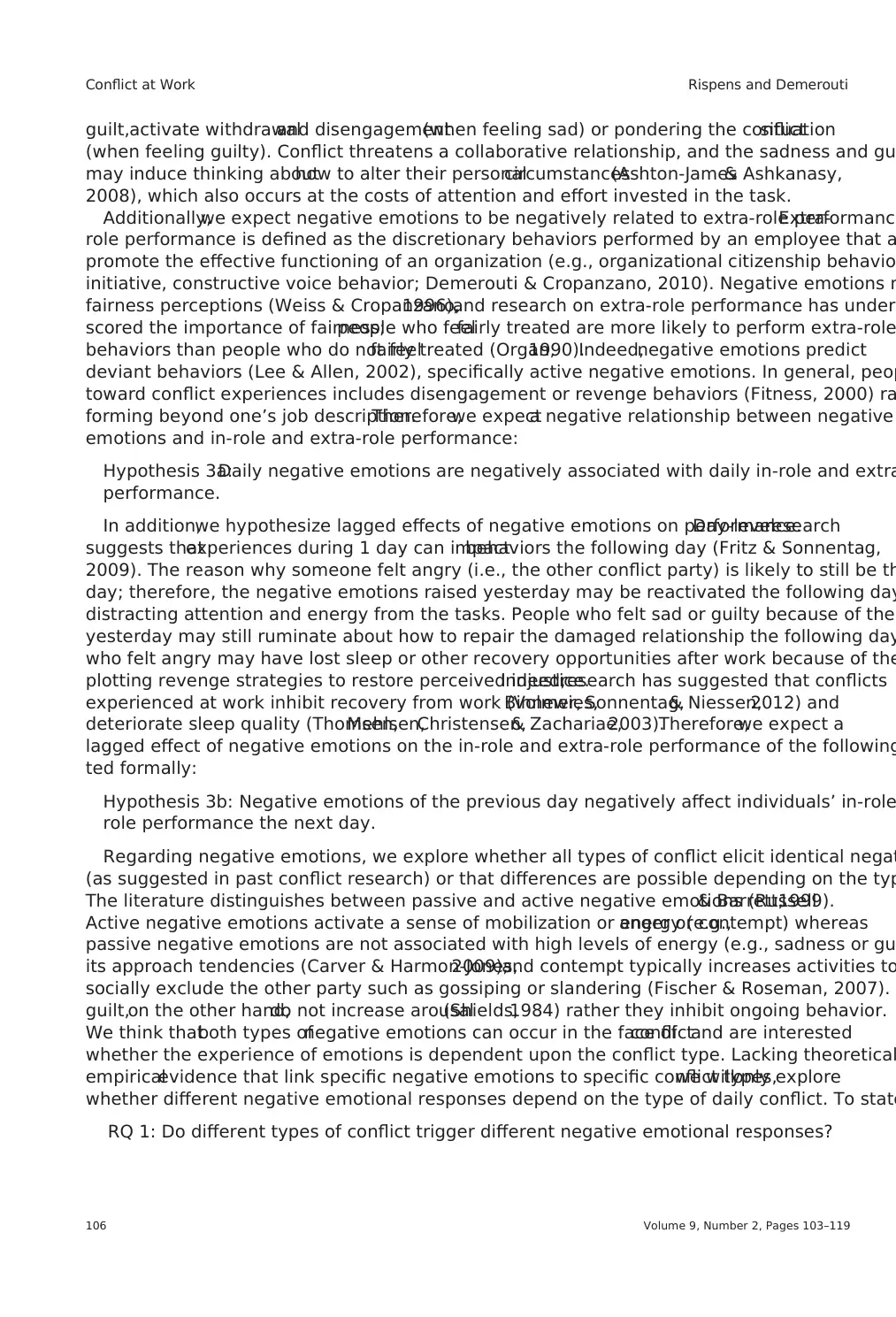

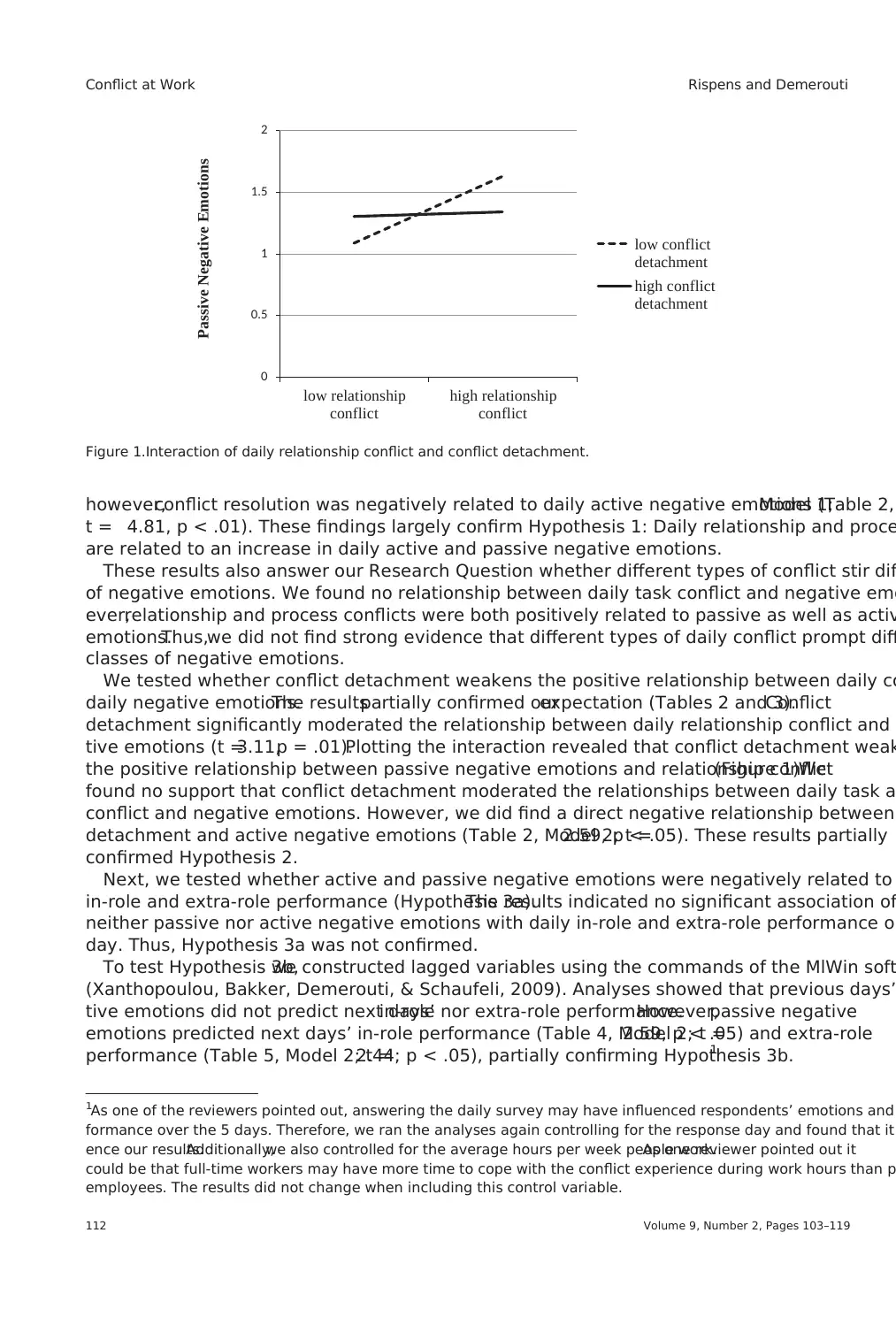

We tested whether conflict detachment weakens the positive relationship between daily co

daily negative emotions.The resultspartially confirmed ourexpectation (Tables 2 and 3).Conflict

detachment significantly moderated the relationship between daily relationship conflict and

tive emotions (t =3.11,p = .01).Plotting the interaction revealed that conflict detachment weak

the positive relationship between passive negative emotions and relationship conflict(Figure 1).We

found no support that conflict detachment moderated the relationships between daily task a

conflict and negative emotions. However, we did find a direct negative relationship between

detachment and active negative emotions (Table 2, Model 2; t =2.59, p < .05). These results partially

confirmed Hypothesis 2.

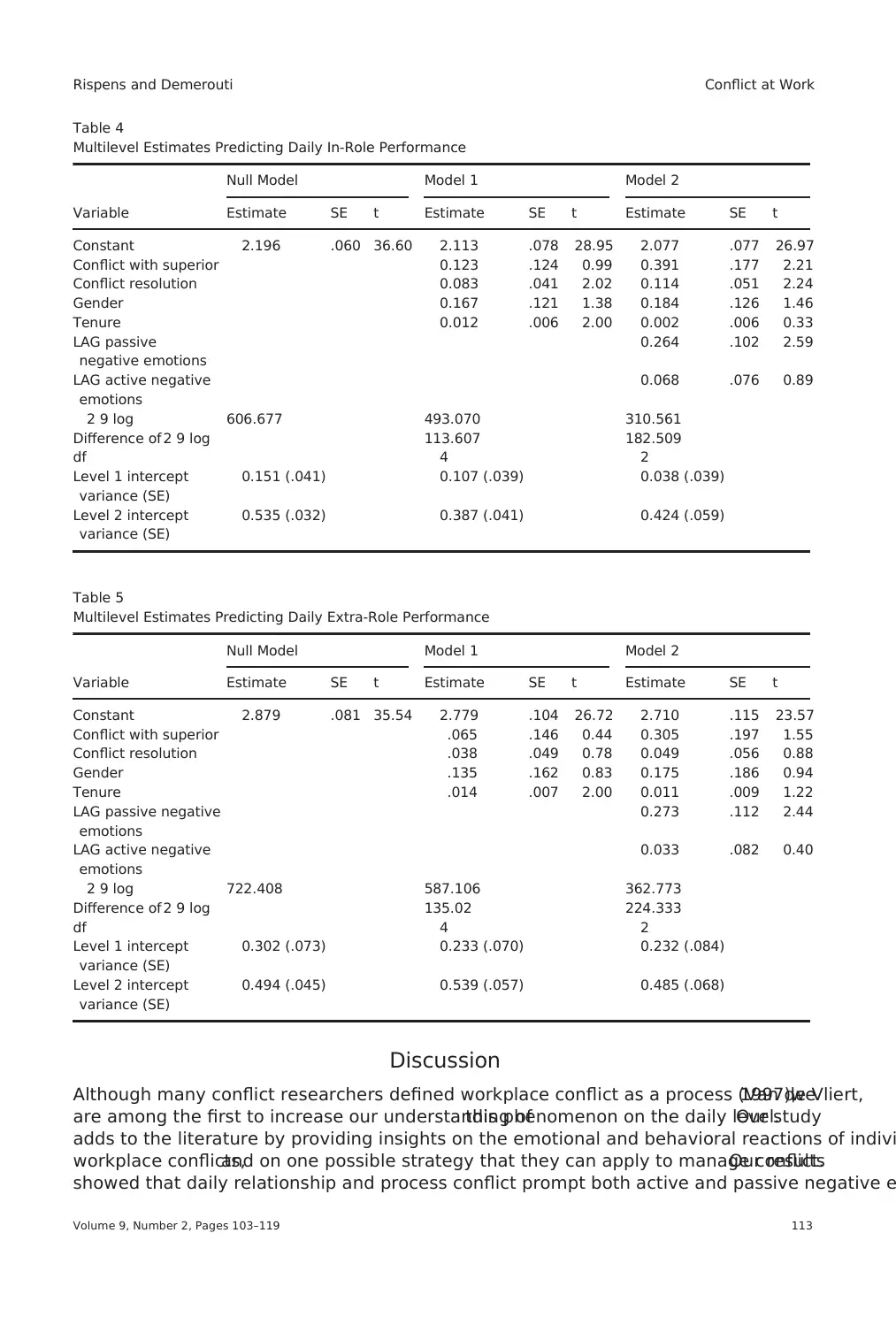

Next, we tested whether active and passive negative emotions were negatively related to

in-role and extra-role performance (Hypothesis 3a).The results indicated no significant association of

neither passive nor active negative emotions with daily in-role and extra-role performance on

day. Thus, Hypothesis 3a was not confirmed.

To test Hypothesis 3b,we constructed lagged variables using the commands of the MlWin soft

(Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009). Analyses showed that previous days’

tive emotions did not predict next days’in-role nor extra-role performance.However,passive negative

emotions predicted next days’ in-role performance (Table 4, Model 2; t =2.59, p < .05) and extra-role

performance (Table 5, Model 2; t =2.44; p < .05), partially confirming Hypothesis 3b.1

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

low relationship

conflict

high relationship

conflict

low conflict

detachment

high conflict

detachment

Passive Negative Emotions

Figure 1.Interaction of daily relationship conflict and conflict detachment.

1As one of the reviewers pointed out, answering the daily survey may have influenced respondents’ emotions and

formance over the 5 days. Therefore, we ran the analyses again controlling for the response day and found that it

ence our results.Additionally,we also controlled for the average hours per week people work.As one reviewer pointed out it

could be that full-time workers may have more time to cope with the conflict experience during work hours than p

employees. The results did not change when including this control variable.

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119112

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

t = 4.81, p < .01). These findings largely confirm Hypothesis 1: Daily relationship and proce

are related to an increase in daily active and passive negative emotions.

These results also answer our Research Question whether different types of conflict stir diff

of negative emotions. We found no relationship between daily task conflict and negative emo

ever,relationship and process conflicts were both positively related to passive as well as activ

emotions.Thus,we did not find strong evidence that different types of daily conflict prompt diff

classes of negative emotions.

We tested whether conflict detachment weakens the positive relationship between daily co

daily negative emotions.The resultspartially confirmed ourexpectation (Tables 2 and 3).Conflict

detachment significantly moderated the relationship between daily relationship conflict and

tive emotions (t =3.11,p = .01).Plotting the interaction revealed that conflict detachment weak

the positive relationship between passive negative emotions and relationship conflict(Figure 1).We

found no support that conflict detachment moderated the relationships between daily task a

conflict and negative emotions. However, we did find a direct negative relationship between

detachment and active negative emotions (Table 2, Model 2; t =2.59, p < .05). These results partially

confirmed Hypothesis 2.

Next, we tested whether active and passive negative emotions were negatively related to

in-role and extra-role performance (Hypothesis 3a).The results indicated no significant association of

neither passive nor active negative emotions with daily in-role and extra-role performance on

day. Thus, Hypothesis 3a was not confirmed.

To test Hypothesis 3b,we constructed lagged variables using the commands of the MlWin soft

(Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009). Analyses showed that previous days’

tive emotions did not predict next days’in-role nor extra-role performance.However,passive negative

emotions predicted next days’ in-role performance (Table 4, Model 2; t =2.59, p < .05) and extra-role

performance (Table 5, Model 2; t =2.44; p < .05), partially confirming Hypothesis 3b.1

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

low relationship

conflict

high relationship

conflict

low conflict

detachment

high conflict

detachment

Passive Negative Emotions

Figure 1.Interaction of daily relationship conflict and conflict detachment.

1As one of the reviewers pointed out, answering the daily survey may have influenced respondents’ emotions and

formance over the 5 days. Therefore, we ran the analyses again controlling for the response day and found that it

ence our results.Additionally,we also controlled for the average hours per week people work.As one reviewer pointed out it

could be that full-time workers may have more time to cope with the conflict experience during work hours than p

employees. The results did not change when including this control variable.

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119112

Conflict at Work Rispens and Demerouti

Discussion

Although many conflict researchers defined workplace conflict as a process (Van de Vliert,1997),we

are among the first to increase our understanding ofthis phenomenon on the daily level.Our study

adds to the literature by providing insights on the emotional and behavioral reactions of indivi

workplace conflicts,and on one possible strategy that they can apply to manage conflict.Our results

showed that daily relationship and process conflict prompt both active and passive negative e

Table 4

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily In-Role Performance

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 2.196 .060 36.60 2.113 .078 28.95 2.077 .077 26.97

Conflict with superior 0.123 .124 0.99 0.391 .177 2.21

Conflict resolution 0.083 .041 2.02 0.114 .051 2.24

Gender 0.167 .121 1.38 0.184 .126 1.46

Tenure 0.012 .006 2.00 0.002 .006 0.33

LAG passive

negative emotions

0.264 .102 2.59

LAG active negative

emotions

0.068 .076 0.89

2 9 log 606.677 493.070 310.561

Difference of 2 9 log 113.607 182.509

df 4 2

Level 1 intercept

variance (SE)

0.151 (.041) 0.107 (.039) 0.038 (.039)

Level 2 intercept

variance (SE)

0.535 (.032) 0.387 (.041) 0.424 (.059)

Table 5

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Extra-Role Performance

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 2.879 .081 35.54 2.779 .104 26.72 2.710 .115 23.57

Conflict with superior .065 .146 0.44 0.305 .197 1.55

Conflict resolution .038 .049 0.78 0.049 .056 0.88

Gender .135 .162 0.83 0.175 .186 0.94

Tenure .014 .007 2.00 0.011 .009 1.22

LAG passive negative

emotions

0.273 .112 2.44

LAG active negative

emotions

0.033 .082 0.40

2 9 log 722.408 587.106 362.773

Difference of 2 9 log 135.02 224.333

df 4 2

Level 1 intercept

variance (SE)

0.302 (.073) 0.233 (.070) 0.232 (.084)

Level 2 intercept

variance (SE)

0.494 (.045) 0.539 (.057) 0.485 (.068)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 113

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

Although many conflict researchers defined workplace conflict as a process (Van de Vliert,1997),we

are among the first to increase our understanding ofthis phenomenon on the daily level.Our study

adds to the literature by providing insights on the emotional and behavioral reactions of indivi

workplace conflicts,and on one possible strategy that they can apply to manage conflict.Our results

showed that daily relationship and process conflict prompt both active and passive negative e

Table 4

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily In-Role Performance

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 2.196 .060 36.60 2.113 .078 28.95 2.077 .077 26.97

Conflict with superior 0.123 .124 0.99 0.391 .177 2.21

Conflict resolution 0.083 .041 2.02 0.114 .051 2.24

Gender 0.167 .121 1.38 0.184 .126 1.46

Tenure 0.012 .006 2.00 0.002 .006 0.33

LAG passive

negative emotions

0.264 .102 2.59

LAG active negative

emotions

0.068 .076 0.89

2 9 log 606.677 493.070 310.561

Difference of 2 9 log 113.607 182.509

df 4 2

Level 1 intercept

variance (SE)

0.151 (.041) 0.107 (.039) 0.038 (.039)

Level 2 intercept

variance (SE)

0.535 (.032) 0.387 (.041) 0.424 (.059)

Table 5

Multilevel Estimates Predicting Daily Extra-Role Performance

Variable

Null Model Model 1 Model 2

Estimate SE t Estimate SE t Estimate SE t

Constant 2.879 .081 35.54 2.779 .104 26.72 2.710 .115 23.57

Conflict with superior .065 .146 0.44 0.305 .197 1.55

Conflict resolution .038 .049 0.78 0.049 .056 0.88

Gender .135 .162 0.83 0.175 .186 0.94

Tenure .014 .007 2.00 0.011 .009 1.22

LAG passive negative

emotions

0.273 .112 2.44

LAG active negative

emotions

0.033 .082 0.40

2 9 log 722.408 587.106 362.773

Difference of 2 9 log 135.02 224.333

df 4 2

Level 1 intercept

variance (SE)

0.302 (.073) 0.233 (.070) 0.232 (.084)

Level 2 intercept

variance (SE)

0.494 (.045) 0.539 (.057) 0.485 (.068)

Volume 9, Number 2, Pages 103–119 113

Rispens and Demerouti Conflict at Work

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 18

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.