Cooperative Wound Clinic Model: Impact on Patient Outcomes & Care

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/26

|7

|8008

|333

Report

AI Summary

This report evaluates the impact of a Cooperative Wound Clinic (CWC) model on improving patient outcomes through enhanced wound management practices in primary health care. The study, employing a longitudinal pre-post design across multiple Australian states, focused on coaching general practitioners and practice nurses in evidence-based wound care. Key findings revealed increased confidence among health professionals in managing various wound types, attributed to repetitive coaching over six months. The CWC model, inspired by the 'Leg Club' approach, fostered a holistic environment emphasizing social interaction, education, and peer support. The intervention, which incorporated local wound experts for training and coaching, demonstrated a positive impact on patient outcomes, knowledge, and satisfaction. The report concludes that expanding this model could empower nurses, improve wound management capabilities, and ultimately lead to better patient care within primary health settings. Task 1 involves answering questions related to the nurse's role in observing and documenting healing progress, as well as criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of wound management strategies and dressing products.

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

Collegian xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Contentslists available at ScienceDirect

Collegian

j o u rn a l h om e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c o l l

Improving patient outcomesby coachingprimary health general

practitioners and practice nurses in evidencebasedwound

managementat on-site wound clinics

K. Innes-Walkera,b, C.N. Parkera,b,∗, K.J. Finlaysona,b, M. Brooksc, L. Youngd, N. Morley e,

D. Maresco-Pennisif, H.E. Edwardsa,b

a Wound ManagementInnovationCooperativeResearchCentre,OxleyHouse,25 Donkin St West End,QLD,Australia

b Facultyof Health,Instituteof Health& BiomedicalInnovation,QueenslandUniversityof Technology,60 Musk Ave.Kelvin Grove,QLD 4059,Australia

c World of Wounds,LatrobeUniversity,Bundoora,Victoria3086,Australia

d Wound ManagementNursePractitioner,TasmanianHealthService,SouthernRegion,Hobart,Tasmania,Australia

e VascularNursePractitioner,QueenslandHealth,BrisbaneSouth,QLD,Australia

f UniversityQueenslandCentrefor Clinical Research,Facultyof Medicine,Royal Brisbaneand Women’sHospital,Brisbane,QLD,Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received19 May 2017

Receivedin revised form 7 March 2018

Accepted18 March 2018

Available online xxx

Keywords:

Wound management

Primary health care

Wound clinic

Model of care

General practice

a b s t r a c t

Background:Wound management is frequently performed in the community and forms a large part

of daily activities of General Practice health professionals.However, previous research has acknowl-

edgeda need for further educationand training on evidencebasedwound managementfor these health

professionals.

Aim: The aim of this project was to develop and trial a CooperativeWound Clinic model of care in Gen-

eral Practices,using a nurse led, interdisciplinary, holistic approach; including training and coaching to

increasethe wound managementexpertiseand capacityof health professionalsworking in the primary

healthcareenvironment.

Methods:A longitudinal, pre-post design was used. Four CooperativeWound Clinic pilot sites and nine

wound clinics were establishedin General Practicesacrossthree Australian stateswith the intervention

of the study being the model of care and incorporating a local wound expert employed to provide the

training and coaching.Pre and post survey data were collectedon wound managementpractices,health

professional confidence in evidence based wound management,patient health, wellbeing and healing

outcomes.Longitudinal patient data were collectedfor 24 weeks.

Findings:Resultsincluded an increasein the confidenceof health professionalsto managewounds. Util-

isation of a repetitive coachingmodel over a six month period empowered the decision making process

and assessmentknowledge for a variety of wound types. A positive impact on patient outcomes for a

variety of wound types was also observed.

Conclusion:The potential for expandingthis model will bring many benefitsincluding: empowerment of

nurses’confidencein managingwounds, promoting the role of nurse led clinics; improved wound related

capabilityand confidenceof health professionals;improved wound management,patient knowledgeand

better patient satisfactionand outcomes.

© 2018 Australian Collegeof Nursing Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Problem

Primary Health is a high priority area requiring more education

and training particularly around evidence based wound manage-

ment practice.

∗ Corresponding author at: QueenslandUniversity of Technology,Victoria Park

Rd. Kelvin Grove, QLD 4059, Australia.

E-mail address:christina.parker@qut.edu.au(C.N. Parker).

What is already known

Wound managementoccurs primarily in the community with

wounds being a common admission diagnosis to community

nursing services and general practice where patients are seen

for frequent on-going visits. There are many barriers to nurses

updating their evidence based wound management knowledge

and significant social and economic benefits would be gained if

resourcesand strategieswere directed to facilitating implementa-

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

1322-7696/©2018 Australian Collegeof Nursing Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

Collegian xxx (2018) xxx–xxx

Contentslists available at ScienceDirect

Collegian

j o u rn a l h om e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c o l l

Improving patient outcomesby coachingprimary health general

practitioners and practice nurses in evidencebasedwound

managementat on-site wound clinics

K. Innes-Walkera,b, C.N. Parkera,b,∗, K.J. Finlaysona,b, M. Brooksc, L. Youngd, N. Morley e,

D. Maresco-Pennisif, H.E. Edwardsa,b

a Wound ManagementInnovationCooperativeResearchCentre,OxleyHouse,25 Donkin St West End,QLD,Australia

b Facultyof Health,Instituteof Health& BiomedicalInnovation,QueenslandUniversityof Technology,60 Musk Ave.Kelvin Grove,QLD 4059,Australia

c World of Wounds,LatrobeUniversity,Bundoora,Victoria3086,Australia

d Wound ManagementNursePractitioner,TasmanianHealthService,SouthernRegion,Hobart,Tasmania,Australia

e VascularNursePractitioner,QueenslandHealth,BrisbaneSouth,QLD,Australia

f UniversityQueenslandCentrefor Clinical Research,Facultyof Medicine,Royal Brisbaneand Women’sHospital,Brisbane,QLD,Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received19 May 2017

Receivedin revised form 7 March 2018

Accepted18 March 2018

Available online xxx

Keywords:

Wound management

Primary health care

Wound clinic

Model of care

General practice

a b s t r a c t

Background:Wound management is frequently performed in the community and forms a large part

of daily activities of General Practice health professionals.However, previous research has acknowl-

edgeda need for further educationand training on evidencebasedwound managementfor these health

professionals.

Aim: The aim of this project was to develop and trial a CooperativeWound Clinic model of care in Gen-

eral Practices,using a nurse led, interdisciplinary, holistic approach; including training and coaching to

increasethe wound managementexpertiseand capacityof health professionalsworking in the primary

healthcareenvironment.

Methods:A longitudinal, pre-post design was used. Four CooperativeWound Clinic pilot sites and nine

wound clinics were establishedin General Practicesacrossthree Australian stateswith the intervention

of the study being the model of care and incorporating a local wound expert employed to provide the

training and coaching.Pre and post survey data were collectedon wound managementpractices,health

professional confidence in evidence based wound management,patient health, wellbeing and healing

outcomes.Longitudinal patient data were collectedfor 24 weeks.

Findings:Resultsincluded an increasein the confidenceof health professionalsto managewounds. Util-

isation of a repetitive coachingmodel over a six month period empowered the decision making process

and assessmentknowledge for a variety of wound types. A positive impact on patient outcomes for a

variety of wound types was also observed.

Conclusion:The potential for expandingthis model will bring many benefitsincluding: empowerment of

nurses’confidencein managingwounds, promoting the role of nurse led clinics; improved wound related

capabilityand confidenceof health professionals;improved wound management,patient knowledgeand

better patient satisfactionand outcomes.

© 2018 Australian Collegeof Nursing Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Problem

Primary Health is a high priority area requiring more education

and training particularly around evidence based wound manage-

ment practice.

∗ Corresponding author at: QueenslandUniversity of Technology,Victoria Park

Rd. Kelvin Grove, QLD 4059, Australia.

E-mail address:christina.parker@qut.edu.au(C.N. Parker).

What is already known

Wound managementoccurs primarily in the community with

wounds being a common admission diagnosis to community

nursing services and general practice where patients are seen

for frequent on-going visits. There are many barriers to nurses

updating their evidence based wound management knowledge

and significant social and economic benefits would be gained if

resourcesand strategieswere directed to facilitating implementa-

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

1322-7696/©2018 Australian Collegeof Nursing Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

2 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

tion of strategies to increase evidence based practices in wound

managementin these health areas.

What this paper adds

The establishment of Cooperative Wound Clinics improved

patient outcomes by enhancing the capabilities of health profes-

sionals in primary health care settings to implement evidence

based wound management.

1. Introduction

The majority of wounds progress smoothly through the stages

of healing, however, some wounds will remain unhealed for

long periods of time. Wounds can occur as a disruption of skin

integrity, as part of a disease process, or from intentional or acci-

dental indications (Young & McNaught, 2011). Having a wound

can be debilitating and patients often suffer multiple symptoms

and effects,including pain, reduced mobility, lower limb oedema,

venous eczema, wound exudate, decreased quality of life and

depression (Jones, Barr, Robinson, & Carlisle, 2006; Parker, 2012).

The effects of chronic leg ulcers involves 1–3% of the population

(Briggs & Closs, 2003; Margolis, Bilker, Santanna, & Baumgarten,

2002) with many remaining unhealed for years or even decades.

Caring for acute and chronic wounds is a multi-billion dollar bur-

den on Australia’s health system with reported costs in excess of

A$3 billion (The Australian Wound Management Association Inc &

The New ZealandWound Care Society Inc, 2011).

Wound managementoccurs primarily in the community with

wounds being a common reason for admission to community nurs-

ing services (RDNS, 2008) and/or General Practice (GP), where

patients are seen for frequent, on-going visits. One study investi-

gating adults with leg ulcers who were visiting GPs for care of their

ulcers, found that 82%attended1–2 times/week for a median of 21

weeks (Edwards et al., 2014). The ageing of the Australian popula-

tion, the increasing incidence of chronic illnesses and recognised

inequities in accessto health care have prompted governmentsto

look for new ways to fund care that has more of a focus on pre-

vention and ongoing disease management (Jolly, 2007). This has

resulted in current health care policy that aims to transfer health

services from the hospital sector to primary care where possible.

With the number of nurses in GPs rapidly increasing from 7728 in

2007 to 10,683 in 2012 (Australian Medicare Local Alliance, 2012),

nursesare well placedto play a lead role in redesigningcareto meet

these challenges.

Wound managementis a large and important part of the daily

activities for most primary health care nurses (Australian Medicare

Local Alliance, 2012). The treatment of people with wounds is an

important issue for nearly every GP in Australia (Britt et al., 2012).

In 2011–12, a considerable proportion (33%) of Medicare claims

were for wound management item numbers (Britt et al., 2012).

Dressings accounted for 20%of all procedures performed by prac-

tice nurses and three of the five most common procedures in GPs

involved wound management(Britt et al., 2012).An education and

training needs analysis performed by the Wound Management

Innovation Cooperative Research Centre indicated that primary

health care was a high priority area requiring more education and

training around evidencebased best wound managementpractice

(Innes-Walker & Edwards,2013).There are many well documented

barriers to nurses updating their evidence based wound manage-

ment knowledge (Coyer, Edwards, & Finlayson, 2005), however, it

has been indicated that significant social and economic benefits

would be gained if resourcesand strategieswere directed to facil-

itating implementation of these strategies in GP (Edwards et al.,

2013; Graves,Finlayson, Gibb, O’Reilly, & Edwards, 2014).

This project implemented a Cooperative Wound Clinic (CWC)

model of care which was underpinned by the principles of the “Leg

Club®

” model of care, developed in the United Kingdom (Lindsay,

2004),and utilising a coachingmodel of education.The “LegClub®”

model provides wound managementfor patients with an emphasis

on social interaction, education,participation and peer support for

patients (Lindsay,2004).A randomised controlled trial in Australia

that compared this model of care to in-home wound care reported

significant improved outcomes in patient quality of life, morale,

self-esteem, healing, pain and functional ability of the patient

(Edwards,Courtney,Finlayson,Shuter,& Lindsay,2009).It was pro-

posed that a service delivery model based on the Leg Club® model

undertaken in a primary health care environment would also offer

improved outcomes for patients and the health care system.

The CWC model of care also utilised coaching strategies

designed to provide holistic, evidence based care and dedicated

wound management clinic time to patients through the utilisa-

tion of a coaching model of education with a wound care expert.

A coaching role in the delivery of education and clinical skills has

been used effectively and has been noted to encouragecommuni-

cation, leadership and adaptability (Johnson, Hamilton, Delaney,

& Pennington, 2011), while utilising skills in facilitation, prac-

tice development principles, adult learning strategies to support

a person centred approach to care (Faithfull-Byrne et al., 2016).

The successful utilisation of a coaching model has also been

shown to increase documented assessments and knowledge in

chronic conditions (Johnston et al., 2007) and health organisa-

tions (Faithfull-Byrne et al., 2016). The role of a practice nurse

in today’s medical environment often occurs in rapidly changing

circumstancesand contemporary demandsfor workplace learning

have been supported by coachingroles in teaching(Faithfull-Byrne

et al., 2016). One-on-one or small group coaching allows for health

professionals to be able to coach other staff through the wound

assessmentand managementprocess,allowing for questions to be

asked and critical decision making to be discussedthroughout the

process.This included staff developmenttraining, work integrated

learning and the development of organised referral pathways for

multidisciplinary care as appropriate.

Specifically, the expert attended the clinic and simultaneously

led education to the health professionals and care to patients to

facilitate the transfer of learning into practice. The wound expert

used a patient centred approach incorporating holistic assessment

and the development of plans with the health professional and

patients and families while also encouraging the socialisation of

patients and/or families and carerswith other patients and/or fam-

ilies and carers in the wound clinic environment as per the Leg

Club® model of care.

2. Aim

The aim of this project was to evaluateoutcomes following the

implementation of the CWC model on:

• Health professionals’knowledge and patients’satisfaction about

evidencebased practice in wound management;

• Feasibility and sustainability within the primary care setting; and

• Patient outcomes (healing and quality of life).

3. Methods

3.1. Design

A longitudinal, pre-post design was used where survey data

from health professionals and patients were collected prior

to implementation of the intervention and 24 weeks post-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

2 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

tion of strategies to increase evidence based practices in wound

managementin these health areas.

What this paper adds

The establishment of Cooperative Wound Clinics improved

patient outcomes by enhancing the capabilities of health profes-

sionals in primary health care settings to implement evidence

based wound management.

1. Introduction

The majority of wounds progress smoothly through the stages

of healing, however, some wounds will remain unhealed for

long periods of time. Wounds can occur as a disruption of skin

integrity, as part of a disease process, or from intentional or acci-

dental indications (Young & McNaught, 2011). Having a wound

can be debilitating and patients often suffer multiple symptoms

and effects,including pain, reduced mobility, lower limb oedema,

venous eczema, wound exudate, decreased quality of life and

depression (Jones, Barr, Robinson, & Carlisle, 2006; Parker, 2012).

The effects of chronic leg ulcers involves 1–3% of the population

(Briggs & Closs, 2003; Margolis, Bilker, Santanna, & Baumgarten,

2002) with many remaining unhealed for years or even decades.

Caring for acute and chronic wounds is a multi-billion dollar bur-

den on Australia’s health system with reported costs in excess of

A$3 billion (The Australian Wound Management Association Inc &

The New ZealandWound Care Society Inc, 2011).

Wound managementoccurs primarily in the community with

wounds being a common reason for admission to community nurs-

ing services (RDNS, 2008) and/or General Practice (GP), where

patients are seen for frequent, on-going visits. One study investi-

gating adults with leg ulcers who were visiting GPs for care of their

ulcers, found that 82%attended1–2 times/week for a median of 21

weeks (Edwards et al., 2014). The ageing of the Australian popula-

tion, the increasing incidence of chronic illnesses and recognised

inequities in accessto health care have prompted governmentsto

look for new ways to fund care that has more of a focus on pre-

vention and ongoing disease management (Jolly, 2007). This has

resulted in current health care policy that aims to transfer health

services from the hospital sector to primary care where possible.

With the number of nurses in GPs rapidly increasing from 7728 in

2007 to 10,683 in 2012 (Australian Medicare Local Alliance, 2012),

nursesare well placedto play a lead role in redesigningcareto meet

these challenges.

Wound managementis a large and important part of the daily

activities for most primary health care nurses (Australian Medicare

Local Alliance, 2012). The treatment of people with wounds is an

important issue for nearly every GP in Australia (Britt et al., 2012).

In 2011–12, a considerable proportion (33%) of Medicare claims

were for wound management item numbers (Britt et al., 2012).

Dressings accounted for 20%of all procedures performed by prac-

tice nurses and three of the five most common procedures in GPs

involved wound management(Britt et al., 2012).An education and

training needs analysis performed by the Wound Management

Innovation Cooperative Research Centre indicated that primary

health care was a high priority area requiring more education and

training around evidencebased best wound managementpractice

(Innes-Walker & Edwards,2013).There are many well documented

barriers to nurses updating their evidence based wound manage-

ment knowledge (Coyer, Edwards, & Finlayson, 2005), however, it

has been indicated that significant social and economic benefits

would be gained if resourcesand strategieswere directed to facil-

itating implementation of these strategies in GP (Edwards et al.,

2013; Graves,Finlayson, Gibb, O’Reilly, & Edwards, 2014).

This project implemented a Cooperative Wound Clinic (CWC)

model of care which was underpinned by the principles of the “Leg

Club®

” model of care, developed in the United Kingdom (Lindsay,

2004),and utilising a coachingmodel of education.The “LegClub®”

model provides wound managementfor patients with an emphasis

on social interaction, education,participation and peer support for

patients (Lindsay,2004).A randomised controlled trial in Australia

that compared this model of care to in-home wound care reported

significant improved outcomes in patient quality of life, morale,

self-esteem, healing, pain and functional ability of the patient

(Edwards,Courtney,Finlayson,Shuter,& Lindsay,2009).It was pro-

posed that a service delivery model based on the Leg Club® model

undertaken in a primary health care environment would also offer

improved outcomes for patients and the health care system.

The CWC model of care also utilised coaching strategies

designed to provide holistic, evidence based care and dedicated

wound management clinic time to patients through the utilisa-

tion of a coaching model of education with a wound care expert.

A coaching role in the delivery of education and clinical skills has

been used effectively and has been noted to encouragecommuni-

cation, leadership and adaptability (Johnson, Hamilton, Delaney,

& Pennington, 2011), while utilising skills in facilitation, prac-

tice development principles, adult learning strategies to support

a person centred approach to care (Faithfull-Byrne et al., 2016).

The successful utilisation of a coaching model has also been

shown to increase documented assessments and knowledge in

chronic conditions (Johnston et al., 2007) and health organisa-

tions (Faithfull-Byrne et al., 2016). The role of a practice nurse

in today’s medical environment often occurs in rapidly changing

circumstancesand contemporary demandsfor workplace learning

have been supported by coachingroles in teaching(Faithfull-Byrne

et al., 2016). One-on-one or small group coaching allows for health

professionals to be able to coach other staff through the wound

assessmentand managementprocess,allowing for questions to be

asked and critical decision making to be discussedthroughout the

process.This included staff developmenttraining, work integrated

learning and the development of organised referral pathways for

multidisciplinary care as appropriate.

Specifically, the expert attended the clinic and simultaneously

led education to the health professionals and care to patients to

facilitate the transfer of learning into practice. The wound expert

used a patient centred approach incorporating holistic assessment

and the development of plans with the health professional and

patients and families while also encouraging the socialisation of

patients and/or families and carerswith other patients and/or fam-

ilies and carers in the wound clinic environment as per the Leg

Club® model of care.

2. Aim

The aim of this project was to evaluateoutcomes following the

implementation of the CWC model on:

• Health professionals’knowledge and patients’satisfaction about

evidencebased practice in wound management;

• Feasibility and sustainability within the primary care setting; and

• Patient outcomes (healing and quality of life).

3. Methods

3.1. Design

A longitudinal, pre-post design was used where survey data

from health professionals and patients were collected prior

to implementation of the intervention and 24 weeks post-

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 3

implementation of the intervention. The outcome measures

included health professionals’ knowledge, confidence and prac-

tices re evidencebased wound management,and patient outcome

measures of wound healing and prevention measures and satis-

faction with care.The health professional survey collected data on

demographics,education, clinical practice details, confidence lev-

els and barriers and limitations in assessment,managementand

prevention of wounds. Patient data collected when attending the

wound clinic at the first visit with a wound or for prevention strate-

giesincluded demographic,medical history, wound characteristics,

wound managementand prevention strategies; and then further

data (wound characteristics)were collected from patients attend-

ing the clinic at least every two weeks or until healing for open

wounds.

3.2. Procedure

Nine nurse-led CWCs were established in a variety of GP

practices which were located across three Australian states

(Queensland,Victoria and Tasmania).A local wound expert in each

state was employed to assist health professionals to consult with

patients and to provide training and coachingat each of thesesites.

The role of the expert trainer was to provide evidence-basedwound

managementtraining and coaching for general health profession-

als as well as playing an active clinical role in the clinic for the time

that they were there. The expert trainer was in most casesa Nurse

Practitioner in wound management.

The expert trainer as part of the intervention in this study was

involved in the initial training of health professionals within each

of the clinics and then attended the clinic once/fortnight to coach

and mentor staff in clinical practice.The initial training in the prac-

tice included a workshop that covered the implementation of the

model of care,wound aetiologies,wound assessment,management

and prevention principles and evidence based practice including

the need for good documentation.The need for a multidisciplinary

approach to wound care was enforced and a referral pathway was

provided to health professionalsin chart form that included details

of specialist clinics and health professionals within the area that

could offer specialist wound care advice. This workshop utilised

PowerPoint presentationsthat also included case studies and real

life scenarios. To assist with staff education, a wound education

and training material package named the CWC ResourceKit was

developed as part of the project and was made available to health

professionals and patients. The training content was also specifi-

cally directed towards GP with the necessaryincorporation of the

relevant MBS item numbers that may be relevant to wound care

practice.

This was followed up by the wound expert attending wound

care appointmentsonce/fortnight where the wound expert worked

with the health professionalstaff to treat the patientsusing a coach-

ing model of teaching. The wound expert would work with the

health professionalsto complete an assessmentof a patient with a

wound followed by the planning and implementation of evidence

based care for that patient. The health professionals were encour-

aged over time to complete all skills themselveswith the ability to

ask questions and discuss options with the wound expert. Sociali-

sation of patients and carerswas encouragedby scheduling at least

two visits at the same time and in the same room. Referral path-

ways were developedin consultation with GP health professionals

and utilised for referral on to specialists as appropriate.

Follow up attendance at clinical appointments by the wound

expert, in conjunction with the health professional staff, ensured

repetitive coaching in a nurturing, safe non-judgemental learn-

ing environment while incorporating the patient and family/carer

within the plan of care.

3.3. Sample

As places were limited, General Practices were invited to sub-

mit expressions of interest and were recruited if they fitted the

following inclusion criteria:

– Clinic was large enough to accommodate two or more wound

patients simultaneously

– Clinic had an interest in wound managementand support from

GPs and practice managers.

– Clinic was willing to collect patient clinical and satisfaction data

and health professional surveys

Patients were recruited if they fitted the inclusion criteria:

– Patientswith an open wound of any type or who visited the clinic

specifically for prevention of a wound

3.4. Data collectionand measures

3.4.1. Health professionals

Data were collected from March 2013 to June 2015 to gather

information before implementation of the CWC model and after

implementation of the CWC model. The health professional survey

was developed to obtain data including demographic information

(i.e.ageand gender)and qualifications (i.e.what is the highest level

of school you have completed or the highest qualification you have

received)and current wound practices(i.e.what percentageof your

work time is currently taken up with providing clinical care or pre-

ventativemanagementto patients at risk of developing wounds or

with current wounds). The survey also asked questions in relation

to evidence based practice based on the validated Self-Efficacy in

EvidenceBasedPractice scale (Chang & Crowe, 2011) and included

items on attitudes (i.e. please indicate your level of agreementor

disagreementwith the following statement: An interprofessional

collaborative approach to wound management results in better

patient outcomes), confidence levels in assessment,management

and prevention of wounds as well as transfer of learning and evi-

dence based wound managementguidelines (i.e., please rate your

confidence level to undertake the following: Finding evidence on

wound managementand clinical practice)and barriers to education

and training.

3.4.2. Patients

Data were collected from March 2013 to June 2015 and con-

tained baselineand follow up data for up to 24 weeks obtainedfrom

medical records, clinical assessment and surveys. This informa-

tion included demographic (age, gender, medical characteristics),

health (medical history, medications, nutrition), clinical charac-

teristics of any wounds (aetiology, area, tissue type, progress in

healing), managementand socioeconomic information. The Pres-

sure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) tool (National Pressure Ulcer

Advisory Panel, 2013) was used to document ulcer severity in all

wounds as this scale has demonstratedreliability and found to be

responsive in different types of leg ulcers and diabetic ulcers (Hon

et al., 2010; Ratliff & Rodeheaver,2005; Santos,Sellmer,& Massulo,

2007). The PUSH tool takes into account the area, the amount of

exudate and wound bed tissue type/surface appearanceas deter-

mined by the clinician. The PUSH scalewas scoredfrom 0 to 17 with

an increasing score indicating deterioration of a wound (National

Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2013). Self-reported survey data

were collected on health-related quality of life (SF-12 v2) (Ware

et al., 1996) and the Patient Enablement and Satisfaction Survey

(PESS)(Desborough,Banfield, & Parker, 2014).

All clinics operatedby appointment only. Patients receivededu-

cation and wound treatment, which was documented; patients

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 3

implementation of the intervention. The outcome measures

included health professionals’ knowledge, confidence and prac-

tices re evidencebased wound management,and patient outcome

measures of wound healing and prevention measures and satis-

faction with care.The health professional survey collected data on

demographics,education, clinical practice details, confidence lev-

els and barriers and limitations in assessment,managementand

prevention of wounds. Patient data collected when attending the

wound clinic at the first visit with a wound or for prevention strate-

giesincluded demographic,medical history, wound characteristics,

wound managementand prevention strategies; and then further

data (wound characteristics)were collected from patients attend-

ing the clinic at least every two weeks or until healing for open

wounds.

3.2. Procedure

Nine nurse-led CWCs were established in a variety of GP

practices which were located across three Australian states

(Queensland,Victoria and Tasmania).A local wound expert in each

state was employed to assist health professionals to consult with

patients and to provide training and coachingat each of thesesites.

The role of the expert trainer was to provide evidence-basedwound

managementtraining and coaching for general health profession-

als as well as playing an active clinical role in the clinic for the time

that they were there. The expert trainer was in most casesa Nurse

Practitioner in wound management.

The expert trainer as part of the intervention in this study was

involved in the initial training of health professionals within each

of the clinics and then attended the clinic once/fortnight to coach

and mentor staff in clinical practice.The initial training in the prac-

tice included a workshop that covered the implementation of the

model of care,wound aetiologies,wound assessment,management

and prevention principles and evidence based practice including

the need for good documentation.The need for a multidisciplinary

approach to wound care was enforced and a referral pathway was

provided to health professionalsin chart form that included details

of specialist clinics and health professionals within the area that

could offer specialist wound care advice. This workshop utilised

PowerPoint presentationsthat also included case studies and real

life scenarios. To assist with staff education, a wound education

and training material package named the CWC ResourceKit was

developed as part of the project and was made available to health

professionals and patients. The training content was also specifi-

cally directed towards GP with the necessaryincorporation of the

relevant MBS item numbers that may be relevant to wound care

practice.

This was followed up by the wound expert attending wound

care appointmentsonce/fortnight where the wound expert worked

with the health professionalstaff to treat the patientsusing a coach-

ing model of teaching. The wound expert would work with the

health professionalsto complete an assessmentof a patient with a

wound followed by the planning and implementation of evidence

based care for that patient. The health professionals were encour-

aged over time to complete all skills themselveswith the ability to

ask questions and discuss options with the wound expert. Sociali-

sation of patients and carerswas encouragedby scheduling at least

two visits at the same time and in the same room. Referral path-

ways were developedin consultation with GP health professionals

and utilised for referral on to specialists as appropriate.

Follow up attendance at clinical appointments by the wound

expert, in conjunction with the health professional staff, ensured

repetitive coaching in a nurturing, safe non-judgemental learn-

ing environment while incorporating the patient and family/carer

within the plan of care.

3.3. Sample

As places were limited, General Practices were invited to sub-

mit expressions of interest and were recruited if they fitted the

following inclusion criteria:

– Clinic was large enough to accommodate two or more wound

patients simultaneously

– Clinic had an interest in wound managementand support from

GPs and practice managers.

– Clinic was willing to collect patient clinical and satisfaction data

and health professional surveys

Patients were recruited if they fitted the inclusion criteria:

– Patientswith an open wound of any type or who visited the clinic

specifically for prevention of a wound

3.4. Data collectionand measures

3.4.1. Health professionals

Data were collected from March 2013 to June 2015 to gather

information before implementation of the CWC model and after

implementation of the CWC model. The health professional survey

was developed to obtain data including demographic information

(i.e.ageand gender)and qualifications (i.e.what is the highest level

of school you have completed or the highest qualification you have

received)and current wound practices(i.e.what percentageof your

work time is currently taken up with providing clinical care or pre-

ventativemanagementto patients at risk of developing wounds or

with current wounds). The survey also asked questions in relation

to evidence based practice based on the validated Self-Efficacy in

EvidenceBasedPractice scale (Chang & Crowe, 2011) and included

items on attitudes (i.e. please indicate your level of agreementor

disagreementwith the following statement: An interprofessional

collaborative approach to wound management results in better

patient outcomes), confidence levels in assessment,management

and prevention of wounds as well as transfer of learning and evi-

dence based wound managementguidelines (i.e., please rate your

confidence level to undertake the following: Finding evidence on

wound managementand clinical practice)and barriers to education

and training.

3.4.2. Patients

Data were collected from March 2013 to June 2015 and con-

tained baselineand follow up data for up to 24 weeks obtainedfrom

medical records, clinical assessment and surveys. This informa-

tion included demographic (age, gender, medical characteristics),

health (medical history, medications, nutrition), clinical charac-

teristics of any wounds (aetiology, area, tissue type, progress in

healing), managementand socioeconomic information. The Pres-

sure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) tool (National Pressure Ulcer

Advisory Panel, 2013) was used to document ulcer severity in all

wounds as this scale has demonstratedreliability and found to be

responsive in different types of leg ulcers and diabetic ulcers (Hon

et al., 2010; Ratliff & Rodeheaver,2005; Santos,Sellmer,& Massulo,

2007). The PUSH tool takes into account the area, the amount of

exudate and wound bed tissue type/surface appearanceas deter-

mined by the clinician. The PUSH scalewas scoredfrom 0 to 17 with

an increasing score indicating deterioration of a wound (National

Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2013). Self-reported survey data

were collected on health-related quality of life (SF-12 v2) (Ware

et al., 1996) and the Patient Enablement and Satisfaction Survey

(PESS)(Desborough,Banfield, & Parker, 2014).

All clinics operatedby appointment only. Patients receivededu-

cation and wound treatment, which was documented; patients

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

4 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

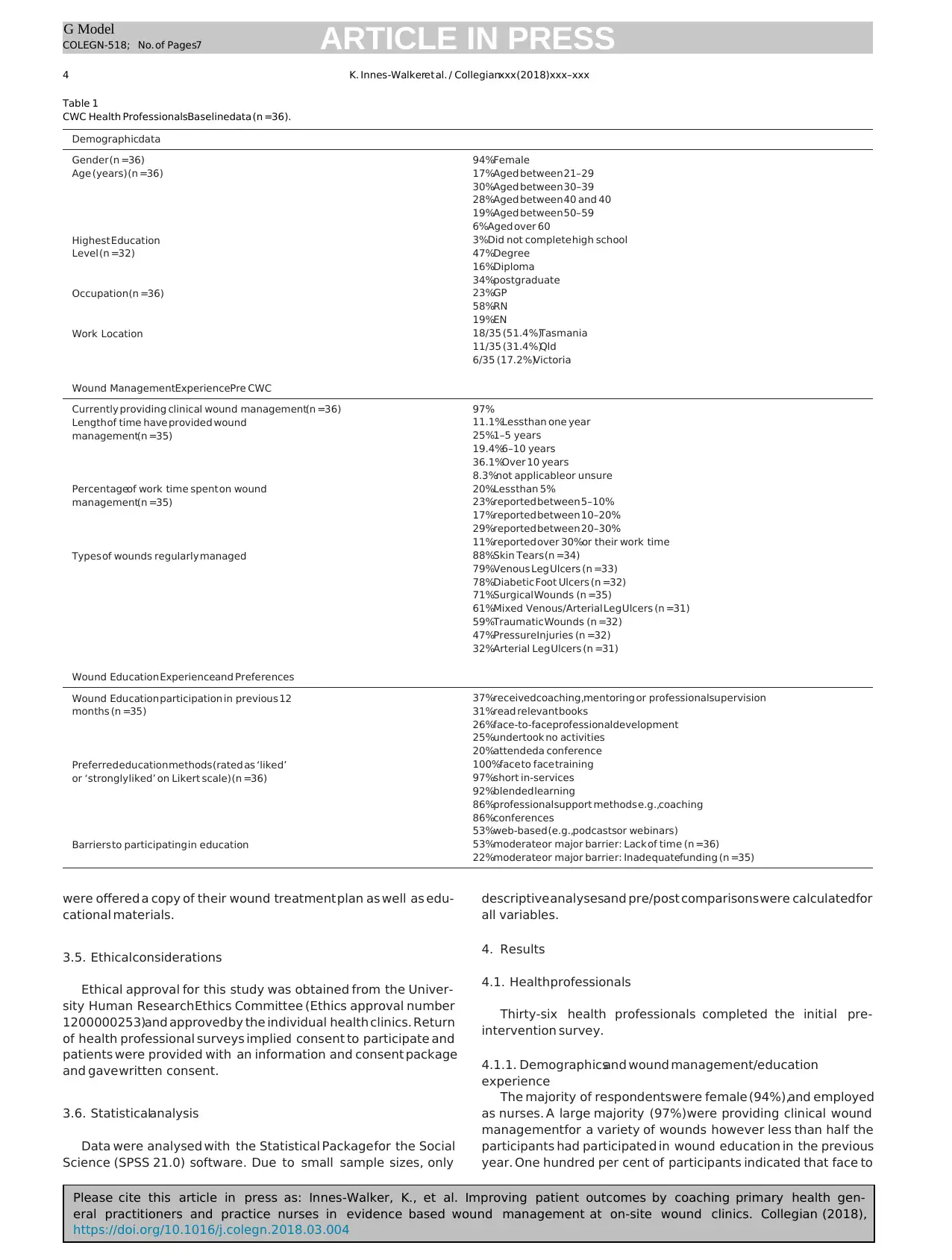

Table 1

CWC Health ProfessionalsBaselinedata (n =36).

Demographicdata

Gender (n =36) 94%Female

Age (years) (n =36) 17%Aged between 21–29

30%Aged between 30–39

28%Aged between 40 and 40

19%Aged between 50–59

6%Aged over 60

Highest Education

Level (n =32)

3%Did not complete high school

47%Degree

16%Diploma

34%postgraduate

Occupation(n =36) 23%GP

58%RN

19%EN

Work Location 18/35 (51.4%)Tasmania

11/35 (31.4%)Qld

6/35 (17.2%)Victoria

Wound ManagementExperiencePre CWC

Currently providing clinical wound management(n =36) 97%

Length of time have provided wound

management(n =35)

11.1%Lessthan one year

25%1–5 years

19.4%6–10 years

36.1%Over 10 years

8.3%not applicableor unsure

Percentageof work time spent on wound

management(n =35)

20%Lessthan 5%

23%reported between 5–10%

17%reported between 10–20%

29%reported between 20–30%

11%reported over 30%or their work time

Types of wounds regularly managed 88%Skin Tears (n =34)

79%Venous Leg Ulcers (n =33)

78%Diabetic Foot Ulcers (n =32)

71%Surgical Wounds (n =35)

61%Mixed Venous/Arterial Leg Ulcers (n =31)

59%Traumatic Wounds (n =32)

47%PressureInjuries (n =32)

32%Arterial Leg Ulcers (n =31)

Wound Education Experienceand Preferences

Wound Education participation in previous 12

months (n =35)

37%receivedcoaching,mentoring or professionalsupervision

31%read relevant books

26%face-to-faceprofessionaldevelopment

25%undertook no activities

20%attendeda conference

Preferred education methods (rated as ‘liked’

or ‘strongly liked’ on Likert scale) (n =36)

100%face to face training

97%short in-services

92%blended learning

86%professionalsupport methods e.g.,coaching

86%conferences

53%web-based (e.g.,podcastsor webinars)

Barriers to participating in education 53%moderateor major barrier: Lack of time (n =36)

22%moderateor major barrier: Inadequatefunding (n =35)

were offered a copy of their wound treatment plan as well as edu-

cational materials.

3.5. Ethicalconsiderations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Univer-

sity Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics approval number

1200000253)and approved by the individual health clinics. Return

of health professional surveys implied consent to participate and

patients were provided with an information and consent package

and gave written consent.

3.6. Statisticalanalysis

Data were analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social

Science (SPSS 21.0) software. Due to small sample sizes, only

descriptive analysesand pre/post comparisons were calculatedfor

all variables.

4. Results

4.1. Healthprofessionals

Thirty-six health professionals completed the initial pre-

intervention survey.

4.1.1. Demographicsand wound management/education

experience

The majority of respondentswere female (94%),and employed

as nurses. A large majority (97%)were providing clinical wound

managementfor a variety of wounds however less than half the

participants had participated in wound education in the previous

year. One hundred per cent of participants indicated that face to

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

4 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

Table 1

CWC Health ProfessionalsBaselinedata (n =36).

Demographicdata

Gender (n =36) 94%Female

Age (years) (n =36) 17%Aged between 21–29

30%Aged between 30–39

28%Aged between 40 and 40

19%Aged between 50–59

6%Aged over 60

Highest Education

Level (n =32)

3%Did not complete high school

47%Degree

16%Diploma

34%postgraduate

Occupation(n =36) 23%GP

58%RN

19%EN

Work Location 18/35 (51.4%)Tasmania

11/35 (31.4%)Qld

6/35 (17.2%)Victoria

Wound ManagementExperiencePre CWC

Currently providing clinical wound management(n =36) 97%

Length of time have provided wound

management(n =35)

11.1%Lessthan one year

25%1–5 years

19.4%6–10 years

36.1%Over 10 years

8.3%not applicableor unsure

Percentageof work time spent on wound

management(n =35)

20%Lessthan 5%

23%reported between 5–10%

17%reported between 10–20%

29%reported between 20–30%

11%reported over 30%or their work time

Types of wounds regularly managed 88%Skin Tears (n =34)

79%Venous Leg Ulcers (n =33)

78%Diabetic Foot Ulcers (n =32)

71%Surgical Wounds (n =35)

61%Mixed Venous/Arterial Leg Ulcers (n =31)

59%Traumatic Wounds (n =32)

47%PressureInjuries (n =32)

32%Arterial Leg Ulcers (n =31)

Wound Education Experienceand Preferences

Wound Education participation in previous 12

months (n =35)

37%receivedcoaching,mentoring or professionalsupervision

31%read relevant books

26%face-to-faceprofessionaldevelopment

25%undertook no activities

20%attendeda conference

Preferred education methods (rated as ‘liked’

or ‘strongly liked’ on Likert scale) (n =36)

100%face to face training

97%short in-services

92%blended learning

86%professionalsupport methods e.g.,coaching

86%conferences

53%web-based (e.g.,podcastsor webinars)

Barriers to participating in education 53%moderateor major barrier: Lack of time (n =36)

22%moderateor major barrier: Inadequatefunding (n =35)

were offered a copy of their wound treatment plan as well as edu-

cational materials.

3.5. Ethicalconsiderations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Univer-

sity Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics approval number

1200000253)and approved by the individual health clinics. Return

of health professional surveys implied consent to participate and

patients were provided with an information and consent package

and gave written consent.

3.6. Statisticalanalysis

Data were analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social

Science (SPSS 21.0) software. Due to small sample sizes, only

descriptive analysesand pre/post comparisons were calculatedfor

all variables.

4. Results

4.1. Healthprofessionals

Thirty-six health professionals completed the initial pre-

intervention survey.

4.1.1. Demographicsand wound management/education

experience

The majority of respondentswere female (94%),and employed

as nurses. A large majority (97%)were providing clinical wound

managementfor a variety of wounds however less than half the

participants had participated in wound education in the previous

year. One hundred per cent of participants indicated that face to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 5

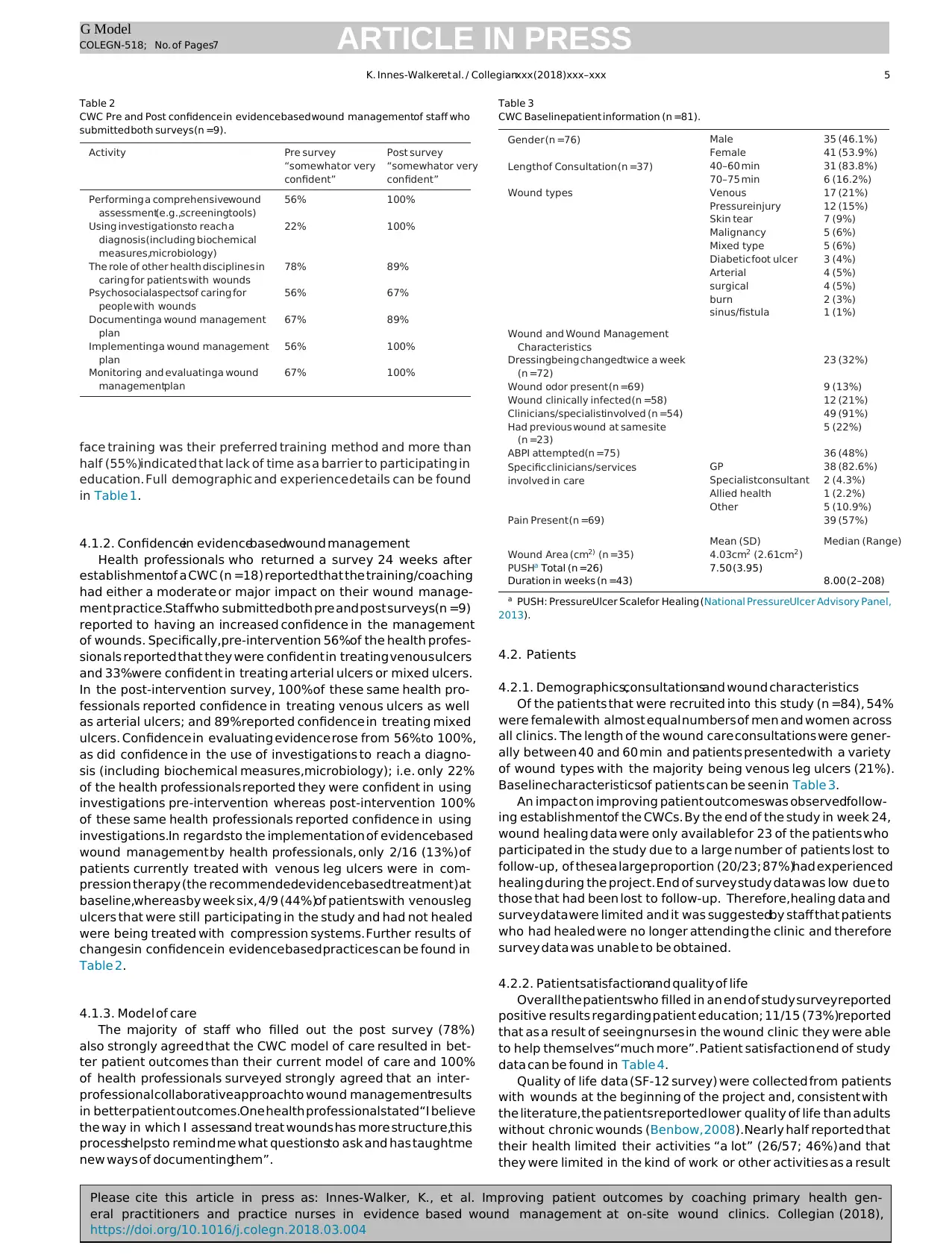

Table 2

CWC Pre and Post confidence in evidencebased wound managementof staff who

submitted both surveys(n =9).

Activity Pre survey

“somewhat or very

confident”

Post survey

“somewhat or very

confident”

Performing a comprehensivewound

assessment(e.g.,screeningtools)

56% 100%

Using investigationsto reach a

diagnosis(including biochemical

measures,microbiology)

22% 100%

The role of other health disciplines in

caring for patients with wounds

78% 89%

Psychosocialaspectsof caring for

people with wounds

56% 67%

Documentinga wound management

plan

67% 89%

Implementing a wound management

plan

56% 100%

Monitoring and evaluatinga wound

managementplan

67% 100%

face training was their preferred training method and more than

half (55%)indicated that lack of time as a barrier to participating in

education. Full demographic and experience details can be found

in Table 1.

4.1.2. Confidencein evidencebasedwound management

Health professionals who returned a survey 24 weeks after

establishmentof a CWC (n =18) reported that the training/coaching

had either a moderate or major impact on their wound manage-

ment practice.Staffwho submitted both pre and post surveys(n =9)

reported to having an increased confidence in the management

of wounds. Specifically,pre-intervention 56%of the health profes-

sionals reported that they were confident in treating venous ulcers

and 33%were confident in treating arterial ulcers or mixed ulcers.

In the post-intervention survey, 100%of these same health pro-

fessionals reported confidence in treating venous ulcers as well

as arterial ulcers; and 89%reported confidence in treating mixed

ulcers. Confidence in evaluating evidence rose from 56%to 100%,

as did confidence in the use of investigations to reach a diagno-

sis (including biochemical measures,microbiology); i.e. only 22%

of the health professionals reported they were confident in using

investigations pre-intervention whereas post-intervention 100%

of these same health professionals reported confidence in using

investigations.In regardsto the implementation of evidencebased

wound management by health professionals, only 2/16 (13%) of

patients currently treated with venous leg ulcers were in com-

pression therapy (the recommendedevidencebased treatment) at

baseline,whereasby week six, 4/9 (44%)of patientswith venousleg

ulcers that were still participating in the study and had not healed

were being treated with compression systems. Further results of

changesin confidence in evidence based practices can be found in

Table 2.

4.1.3. Model of care

The majority of staff who filled out the post survey (78%)

also strongly agreed that the CWC model of care resulted in bet-

ter patient outcomes than their current model of care and 100%

of health professionals surveyed strongly agreed that an inter-

professionalcollaborativeapproachto wound managementresults

in better patient outcomes.One health professionalstated“I believe

the way in which I assessand treat wounds has more structure,this

processhelpsto remind me what questionsto ask and has taughtme

new ways of documentingthem”.

Table 3

CWC Baselinepatient information (n =81).

Gender (n =76) Male 35 (46.1%)

Female 41 (53.9%)

Length of Consultation (n =37) 40–60 min 31 (83.8%)

70–75 min 6 (16.2%)

Wound types Venous 17 (21%)

Pressureinjury 12 (15%)

Skin tear 7 (9%)

Malignancy 5 (6%)

Mixed type 5 (6%)

Diabetic foot ulcer 3 (4%)

Arterial 4 (5%)

surgical 4 (5%)

burn 2 (3%)

sinus/fistula 1 (1%)

Wound and Wound Management

Characteristics

Dressingbeing changedtwice a week

(n =72)

23 (32%)

Wound odor present (n =69) 9 (13%)

Wound clinically infected (n =58) 12 (21%)

Clinicians/specialistinvolved (n =54) 49 (91%)

Had previous wound at same site

(n =23)

5 (22%)

ABPI attempted(n =75) 36 (48%)

Specific clinicians/services

involved in care

GP 38 (82.6%)

Specialistconsultant 2 (4.3%)

Allied health 1 (2.2%)

Other 5 (10.9%)

Pain Present (n =69) 39 (57%)

Mean (SD) Median (Range)

Wound Area (cm2) (n =35) 4.03cm2 (2.61cm2)

PUSHa Total (n =26) 7.50 (3.95)

Duration in weeks (n =43) 8.00 (2–208)

a PUSH: PressureUlcer Scalefor Healing (National PressureUlcer Advisory Panel,

2013).

4.2. Patients

4.2.1. Demographics,consultationsand wound characteristics

Of the patients that were recruited into this study (n =84), 54%

were female with almost equal numbers of men and women across

all clinics. The length of the wound care consultations were gener-

ally between 40 and 60 min and patients presented with a variety

of wound types with the majority being venous leg ulcers (21%).

Baseline characteristicsof patients can be seen in Table 3.

An impact on improving patient outcomeswas observedfollow-

ing establishmentof the CWCs. By the end of the study in week 24,

wound healing data were only available for 23 of the patients who

participated in the study due to a large number of patients lost to

follow-up, of thesea large proportion (20/23; 87%)had experienced

healing during the project. End of survey study data was low due to

those that had been lost to follow-up. Therefore,healing data and

survey data were limited and it was suggestedby staff that patients

who had healed were no longer attending the clinic and therefore

survey data was unable to be obtained.

4.2.2. Patientsatisfactionand quality of life

Overall the patientswho filled in an end of study surveyreported

positive results regarding patient education; 11/15 (73%)reported

that as a result of seeingnurses in the wound clinic they were able

to help themselves“much more”. Patient satisfaction end of study

data can be found in Table 4.

Quality of life data (SF-12 survey) were collected from patients

with wounds at the beginning of the project and, consistent with

the literature,the patients reported lower quality of life than adults

without chronic wounds (Benbow, 2008).Nearly half reported that

their health limited their activities “a lot” (26/57; 46%) and that

they were limited in the kind of work or other activities as a result

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 5

Table 2

CWC Pre and Post confidence in evidencebased wound managementof staff who

submitted both surveys(n =9).

Activity Pre survey

“somewhat or very

confident”

Post survey

“somewhat or very

confident”

Performing a comprehensivewound

assessment(e.g.,screeningtools)

56% 100%

Using investigationsto reach a

diagnosis(including biochemical

measures,microbiology)

22% 100%

The role of other health disciplines in

caring for patients with wounds

78% 89%

Psychosocialaspectsof caring for

people with wounds

56% 67%

Documentinga wound management

plan

67% 89%

Implementing a wound management

plan

56% 100%

Monitoring and evaluatinga wound

managementplan

67% 100%

face training was their preferred training method and more than

half (55%)indicated that lack of time as a barrier to participating in

education. Full demographic and experience details can be found

in Table 1.

4.1.2. Confidencein evidencebasedwound management

Health professionals who returned a survey 24 weeks after

establishmentof a CWC (n =18) reported that the training/coaching

had either a moderate or major impact on their wound manage-

ment practice.Staffwho submitted both pre and post surveys(n =9)

reported to having an increased confidence in the management

of wounds. Specifically,pre-intervention 56%of the health profes-

sionals reported that they were confident in treating venous ulcers

and 33%were confident in treating arterial ulcers or mixed ulcers.

In the post-intervention survey, 100%of these same health pro-

fessionals reported confidence in treating venous ulcers as well

as arterial ulcers; and 89%reported confidence in treating mixed

ulcers. Confidence in evaluating evidence rose from 56%to 100%,

as did confidence in the use of investigations to reach a diagno-

sis (including biochemical measures,microbiology); i.e. only 22%

of the health professionals reported they were confident in using

investigations pre-intervention whereas post-intervention 100%

of these same health professionals reported confidence in using

investigations.In regardsto the implementation of evidencebased

wound management by health professionals, only 2/16 (13%) of

patients currently treated with venous leg ulcers were in com-

pression therapy (the recommendedevidencebased treatment) at

baseline,whereasby week six, 4/9 (44%)of patientswith venousleg

ulcers that were still participating in the study and had not healed

were being treated with compression systems. Further results of

changesin confidence in evidence based practices can be found in

Table 2.

4.1.3. Model of care

The majority of staff who filled out the post survey (78%)

also strongly agreed that the CWC model of care resulted in bet-

ter patient outcomes than their current model of care and 100%

of health professionals surveyed strongly agreed that an inter-

professionalcollaborativeapproachto wound managementresults

in better patient outcomes.One health professionalstated“I believe

the way in which I assessand treat wounds has more structure,this

processhelpsto remind me what questionsto ask and has taughtme

new ways of documentingthem”.

Table 3

CWC Baselinepatient information (n =81).

Gender (n =76) Male 35 (46.1%)

Female 41 (53.9%)

Length of Consultation (n =37) 40–60 min 31 (83.8%)

70–75 min 6 (16.2%)

Wound types Venous 17 (21%)

Pressureinjury 12 (15%)

Skin tear 7 (9%)

Malignancy 5 (6%)

Mixed type 5 (6%)

Diabetic foot ulcer 3 (4%)

Arterial 4 (5%)

surgical 4 (5%)

burn 2 (3%)

sinus/fistula 1 (1%)

Wound and Wound Management

Characteristics

Dressingbeing changedtwice a week

(n =72)

23 (32%)

Wound odor present (n =69) 9 (13%)

Wound clinically infected (n =58) 12 (21%)

Clinicians/specialistinvolved (n =54) 49 (91%)

Had previous wound at same site

(n =23)

5 (22%)

ABPI attempted(n =75) 36 (48%)

Specific clinicians/services

involved in care

GP 38 (82.6%)

Specialistconsultant 2 (4.3%)

Allied health 1 (2.2%)

Other 5 (10.9%)

Pain Present (n =69) 39 (57%)

Mean (SD) Median (Range)

Wound Area (cm2) (n =35) 4.03cm2 (2.61cm2)

PUSHa Total (n =26) 7.50 (3.95)

Duration in weeks (n =43) 8.00 (2–208)

a PUSH: PressureUlcer Scalefor Healing (National PressureUlcer Advisory Panel,

2013).

4.2. Patients

4.2.1. Demographics,consultationsand wound characteristics

Of the patients that were recruited into this study (n =84), 54%

were female with almost equal numbers of men and women across

all clinics. The length of the wound care consultations were gener-

ally between 40 and 60 min and patients presented with a variety

of wound types with the majority being venous leg ulcers (21%).

Baseline characteristicsof patients can be seen in Table 3.

An impact on improving patient outcomeswas observedfollow-

ing establishmentof the CWCs. By the end of the study in week 24,

wound healing data were only available for 23 of the patients who

participated in the study due to a large number of patients lost to

follow-up, of thesea large proportion (20/23; 87%)had experienced

healing during the project. End of survey study data was low due to

those that had been lost to follow-up. Therefore,healing data and

survey data were limited and it was suggestedby staff that patients

who had healed were no longer attending the clinic and therefore

survey data was unable to be obtained.

4.2.2. Patientsatisfactionand quality of life

Overall the patientswho filled in an end of study surveyreported

positive results regarding patient education; 11/15 (73%)reported

that as a result of seeingnurses in the wound clinic they were able

to help themselves“much more”. Patient satisfaction end of study

data can be found in Table 4.

Quality of life data (SF-12 survey) were collected from patients

with wounds at the beginning of the project and, consistent with

the literature,the patients reported lower quality of life than adults

without chronic wounds (Benbow, 2008).Nearly half reported that

their health limited their activities “a lot” (26/57; 46%) and that

they were limited in the kind of work or other activities as a result

Please cite this article in press as: Innes-Walker, K., et al. Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health gen-

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

6 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

Table 4

CWC Patient End of study survey Data (Week 24).

Percent that “strongly agreed”

Patient reported that the treatmentsthey receivedwere of high quality 93%(n =15)

Patient reported that the decisionsregardingtheir health care were of high quality 87%(n =15)

Patient reported that overall they were satisfied with their wound care 87%(n =15)

Patient reported that the wound care they receivedfrom the nurse/s was of high quality 87%(n =15)

Patient reported they felt much more able to help themselvesas a result of seeingthe nurses 73%(n =15)

Patient’sulcer had healed by week 24 the end of the study 87%(n =23)

of their physical health 24/55 (43%).Quality of life data at the end

of the intervention period was collected and returned from a lim-

ited number of patients (n =5), however, within this group of 5

patients, there was a notable improvement in the overall health-

related Quality of Life score from a mean of 37.2 (SD 13.9) at the

beginning of the project, up to 47.3 (SD 9.7) after 24 weeks (total

scalefrom 0 to 100). In this small group at the end of the study only

one patient of the five reported their health limited their activities.

5. Discussion

GP settings are a central point of access for patients into the

health caresystem(Yelland, 2014) and health professionalsin these

settings are well placed to make a difference in the area of wound

care.Having specialistNurse Practitioners as leaderswithin wound

management are key to empowering and nurturing the skill set

capabilitiesfor health professionals.Support and guidancefor prac-

tice health professionals’ decision making processes, gains their

confidence through repetitive learning and coaching, this enables

autonomy, continuity in care and overall improvement in both

nurses and patient’s decision for optimal evidence based wound

care outcomes. This project has been able to provide evidence on

the different types of wounds cared for at GPs and a model to

educate health professionals and patients about evidence based

practice in wound management using a training and modelling

(coaching) model to facilitate research translation in the GP set-

ting. This model has been effective in being able to increasehealth

professionals’confidencein the assessment,managementand pre-

vention of a variety of wounds while also being able to facilitate

uptake of evidence based,best practice within the primary health

caresettingas required.The baselinedata supportedprevious stud-

ies (Edwards et al., 2013,2014) in that evidencebasedpracticesare

often not performed in general practice and has shown increased

rates of evidencebased practice post study.

6. Limitations

The participant and clinicians’ commitment to this project may

have influenced results, possibly indicating bias. There was sig-

nificant missing documentation in relation to follow up data on

patients and health professionals.The time that health profession-

als had with patients was often not considered adequategiven the

complexities of the patients referred i.e. medical history, language

barriers,if there were multiple wounds present,and lack of practice

nurse item numbers and remuneration limited what could reason-

ably be done. The GP setting is always very busy and finding the

time to ensure accuratedocumentation was often a challenge.

Referral pathways were developed specific for each area how-

ever in some cases,ensuring health professionalsfollowed this was

a challenge.A barrier to uptake of best practicewas the cost of some

treatments,where some treatmentswere not an affordable option

for the patient to purchase.One of the original aims of the project,

to increasesocialisation for patients,was difficult to managein the

general practice setting; as even when a treatment room was allo-

cated for a wound care clinic, emergencyadmissions often needed

to be accommodatedand therefore only one patient could be seen

at a time.

Although we note that an increase in staff confidence in this

study appears to have been accompanied by improved patient

outcomes, it is important to note that an increase in practitioner

confidence does always correlate with an increase in evidence

based practices (Flanagan,2005) or in wound healing. Education

has limited value if it is not sustained and applied to practice

(Flanagan,2005) in an appropriateway. This project shows encour-

aging results in regard to increasing confidence levels of health

practitioners as well as an increase in some evidence based prac-

tices. Further examination of other evidence-based practices is

necessaryand long term investigation of sustainability of this con-

fidence and use of evidence based practices would be beneficial.

7. Conclusion

The establishment of CWCs led to improved patient outcomes

by enhancing the capabilities of health professionals in primary

health care settingsto implement evidencebasedwound manage-

ment. Further uptake and evaluation of this model could benefit

patients in the community by facilitating the implementation of

evidence based wound care leading to improved health outcomes

and ultimately decreasingthe costs to the patients and the health

care system.The use of wound experts,mainly Nurse Practitioners

in wound care, was essential to this process and the use of Nurse

Practitioners in GP requires further exploration of the benefits to

practice and patient outcomes.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Wound Management Inno-

vation CRC (established and supported under the Australian

Government’sCooperativeResearchCentresProgram).

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Aus-

tralian Government’sCooperative ResearchCentres Program. The

authors would like to acknowledge and thank all the staff and par-

ticipants who were involved in contributing to the study. Namely,

South West Melbourne Medical Local (SWMML), Victoria; North-

ern Melbourne Medicare Local (NMML), Victoria; WestgateHealth

Co-op, Victoria; RosannaMedical Group, Victoria; Viewbank Med-

ical Group, Victoria; Tasmania Medicare Local (TML); Bellerive

Medical Centre,Tasmania; The Lindisfarne Clinic, Tasmania; Sandy

Bay Medical Centre, Tasmania; Lauderdale Doctors Surgery, Tas-

mania; Greater Brisbane Metro South Medicare Local (GBMSML),

Queensland; Calamvale Medical Centre, Queensland and Garden

City Medical Centre,Queensland.

eral practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.004

ARTICLE IN PRESSG Model

COLEGN-518; No. of Pages7

6 K. Innes-Walkeret al. / Collegianxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

Table 4

CWC Patient End of study survey Data (Week 24).

Percent that “strongly agreed”

Patient reported that the treatmentsthey receivedwere of high quality 93%(n =15)

Patient reported that the decisionsregardingtheir health care were of high quality 87%(n =15)

Patient reported that overall they were satisfied with their wound care 87%(n =15)

Patient reported that the wound care they receivedfrom the nurse/s was of high quality 87%(n =15)

Patient reported they felt much more able to help themselvesas a result of seeingthe nurses 73%(n =15)

Patient’sulcer had healed by week 24 the end of the study 87%(n =23)

of their physical health 24/55 (43%).Quality of life data at the end

of the intervention period was collected and returned from a lim-

ited number of patients (n =5), however, within this group of 5

patients, there was a notable improvement in the overall health-

related Quality of Life score from a mean of 37.2 (SD 13.9) at the

beginning of the project, up to 47.3 (SD 9.7) after 24 weeks (total

scalefrom 0 to 100). In this small group at the end of the study only

one patient of the five reported their health limited their activities.

5. Discussion

GP settings are a central point of access for patients into the

health caresystem(Yelland, 2014) and health professionalsin these

settings are well placed to make a difference in the area of wound

care.Having specialistNurse Practitioners as leaderswithin wound

management are key to empowering and nurturing the skill set

capabilitiesfor health professionals.Support and guidancefor prac-

tice health professionals’ decision making processes, gains their

confidence through repetitive learning and coaching, this enables

autonomy, continuity in care and overall improvement in both

nurses and patient’s decision for optimal evidence based wound

care outcomes. This project has been able to provide evidence on

the different types of wounds cared for at GPs and a model to

educate health professionals and patients about evidence based

practice in wound management using a training and modelling

(coaching) model to facilitate research translation in the GP set-

ting. This model has been effective in being able to increasehealth

professionals’confidencein the assessment,managementand pre-

vention of a variety of wounds while also being able to facilitate

uptake of evidence based,best practice within the primary health

caresettingas required.The baselinedata supportedprevious stud-

ies (Edwards et al., 2013,2014) in that evidencebasedpracticesare

often not performed in general practice and has shown increased

rates of evidencebased practice post study.

6. Limitations

The participant and clinicians’ commitment to this project may

have influenced results, possibly indicating bias. There was sig-

nificant missing documentation in relation to follow up data on

patients and health professionals.The time that health profession-

als had with patients was often not considered adequategiven the

complexities of the patients referred i.e. medical history, language

barriers,if there were multiple wounds present,and lack of practice

nurse item numbers and remuneration limited what could reason-

ably be done. The GP setting is always very busy and finding the

time to ensure accuratedocumentation was often a challenge.

Referral pathways were developed specific for each area how-

ever in some cases,ensuring health professionalsfollowed this was

a challenge.A barrier to uptake of best practicewas the cost of some

treatments,where some treatmentswere not an affordable option

for the patient to purchase.One of the original aims of the project,

to increasesocialisation for patients,was difficult to managein the

general practice setting; as even when a treatment room was allo-

cated for a wound care clinic, emergencyadmissions often needed

to be accommodatedand therefore only one patient could be seen

at a time.

Although we note that an increase in staff confidence in this

study appears to have been accompanied by improved patient

outcomes, it is important to note that an increase in practitioner

confidence does always correlate with an increase in evidence

based practices (Flanagan,2005) or in wound healing. Education

has limited value if it is not sustained and applied to practice

(Flanagan,2005) in an appropriateway. This project shows encour-

aging results in regard to increasing confidence levels of health

practitioners as well as an increase in some evidence based prac-

tices. Further examination of other evidence-based practices is

necessaryand long term investigation of sustainability of this con-

fidence and use of evidence based practices would be beneficial.

7. Conclusion

The establishment of CWCs led to improved patient outcomes

by enhancing the capabilities of health professionals in primary

health care settingsto implement evidencebasedwound manage-