Review of the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference and Negotiations

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/29

|27

|15145

|110

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Change Conference from the perspective of a government delegate. It details the complex political dynamics, key policy issues, and the positions of major countries and coalitions during the UN climate negotiations. The report offers an insider's account of the heated debates and the dramatic collapse of the conference, highlighting the failure to produce a global climate treaty. It contrasts the stagnation of the UN process with the progress in aggregate climate policy and multilevel climate governance. The report also examines the background and context of the conference, the stakes involved, the consequences of climate change, and the policy ramifications. It concludes by assessing the outcomes of Copenhagen, identifying policy achievements and failures, and evaluating the current state of global climate politics.

Inside UN Climate Change Negotiations:

The Copenhagen Conferenceropr_472 795..822

Radoslav S. Dimitrov

University of Western Ontario

Abstract

UN negotiations on climate change entaila fundamentaltransformation of the globaleconomy and

constitute the single most important process in world politics. This is an account of the 2009 C

summitfrom the perspective ofa governmentdelegate.The article offersa guide to globalclimate

negotiations,tells the story of Copenhagen from behind closed doors,and assesses the currentstate of

globalclimate governance.It outlineskey policy issuesunder negotiation,the positionsand policy

preferences of key countries and coalitions, the outcomes of Copenhagen, and achievements

in climate negotiationsto date.The Copenhagen Accord isa weak agreementdesigned to mask the

political failure of the international community to create a global climate treaty. However, clim

around the world is making considerable progress.While the UN negotiations process is deadlocked,

multilevel climate governance is thriving.

KEY WORDS: climate change,climate politics,internationalnegotiations,environmentalpolicy,

Copenhagen Accord

Introduction

The UN Climate Change Conference of December 2009 in Copenhagen brought

togetherthe global political elite to launch humankind’s response to global

warming.The conference was the largest summit in the history ofinternational

diplomacy.One hundred and nineteen kings,presidents,and prime ministers in

the same building constituted the highest concentration of robust decision-making

power the world had seen. Their presence on a highly visible political arena raised

high hopes for a successful outcome: Copenhagen was “condemned to success.”1 By

the middle of the second week,however,we knew the only outstanding question

was concerning the exact shape of failure.

This is an account of the Copenhagen negotiations from behind closed doors,

from the perspective of a government delegate.2 UN climate change negotiations

are not “environmental”:they are aboutthe economic future ofnations.Today

governments are negotiating a fundamental transformation of the global economy

toward low-carbon development.Climate politics is reshaping our world and the

new climate treaty willlikely be the mostimportantinternationalagreementin

human history.Having been privy to consequentialpolitical discussionswhere

neither the globalmedia nor civilsociety had access,I would like to share obser-

vations concerning the political dynamics and policy outcomes that affect all people

around the world.

The article offers a guide to global climate change negotiations. After describing

the problem and clarifying the economic and ecological stakes, it explains key policy

issues in UN climate negotiations and the positions of major countries and political

coalitions. The article provides an insider’s account of the Copenhagen conference

and retells some of the heated debates among states. The story lets countries speak

for themselves and relies on direct quotes from delegation statements to illustrate

795

Review of Policy Research, Volume 27, Number 6 (2010)

© 2010 by The Policy Studies Organization. All rights reserved.

The Copenhagen Conferenceropr_472 795..822

Radoslav S. Dimitrov

University of Western Ontario

Abstract

UN negotiations on climate change entaila fundamentaltransformation of the globaleconomy and

constitute the single most important process in world politics. This is an account of the 2009 C

summitfrom the perspective ofa governmentdelegate.The article offersa guide to globalclimate

negotiations,tells the story of Copenhagen from behind closed doors,and assesses the currentstate of

globalclimate governance.It outlineskey policy issuesunder negotiation,the positionsand policy

preferences of key countries and coalitions, the outcomes of Copenhagen, and achievements

in climate negotiationsto date.The Copenhagen Accord isa weak agreementdesigned to mask the

political failure of the international community to create a global climate treaty. However, clim

around the world is making considerable progress.While the UN negotiations process is deadlocked,

multilevel climate governance is thriving.

KEY WORDS: climate change,climate politics,internationalnegotiations,environmentalpolicy,

Copenhagen Accord

Introduction

The UN Climate Change Conference of December 2009 in Copenhagen brought

togetherthe global political elite to launch humankind’s response to global

warming.The conference was the largest summit in the history ofinternational

diplomacy.One hundred and nineteen kings,presidents,and prime ministers in

the same building constituted the highest concentration of robust decision-making

power the world had seen. Their presence on a highly visible political arena raised

high hopes for a successful outcome: Copenhagen was “condemned to success.”1 By

the middle of the second week,however,we knew the only outstanding question

was concerning the exact shape of failure.

This is an account of the Copenhagen negotiations from behind closed doors,

from the perspective of a government delegate.2 UN climate change negotiations

are not “environmental”:they are aboutthe economic future ofnations.Today

governments are negotiating a fundamental transformation of the global economy

toward low-carbon development.Climate politics is reshaping our world and the

new climate treaty willlikely be the mostimportantinternationalagreementin

human history.Having been privy to consequentialpolitical discussionswhere

neither the globalmedia nor civilsociety had access,I would like to share obser-

vations concerning the political dynamics and policy outcomes that affect all people

around the world.

The article offers a guide to global climate change negotiations. After describing

the problem and clarifying the economic and ecological stakes, it explains key policy

issues in UN climate negotiations and the positions of major countries and political

coalitions. The article provides an insider’s account of the Copenhagen conference

and retells some of the heated debates among states. The story lets countries speak

for themselves and relies on direct quotes from delegation statements to illustrate

795

Review of Policy Research, Volume 27, Number 6 (2010)

© 2010 by The Policy Studies Organization. All rights reserved.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

their positions and to convey the highly emotionalexchange that led to the dra-

matic collapse of the conference.3 The final sections summarize the Copenhagen

outcomes, identify policy achievements and failures, and assess the current state of

affairs in global climate politics.

The Short Story

The sheer size of the summit was staggering.There were 37,000 registered

participants including 10,500 government delegates,13,500 observers from civil

society, and 3,000 journalists.4 Security was so tight that the Chinese Minister of the

Environment could not enter the Bella Conference Center for two days because he

had been issued the wrong conference pass.Government delegations conducted

more than 1,000 official and informal meetings over the two weeks and held 300

press conferences.The record number of premiers and ministers required 1,200

limousines and 400 helicopters. And while the world’s attention was justifiably on

Copenhagen,the conference produced perhapsthe most ambiguousoutcome

in diplomatic history, leaving governments and observers alike wondering how to

assess the results (Averchenkova, 2010; Egenhofer & Georgiev, 2009).

The brief story of Copenhagen, in my view, contains three main political devel-

opments.First, Western countriesmade considerable contributionsto a strong

global agreement. All industrialized nations, with the exception of the United States

and Canada, laid the ground for a treaty by offering ambitious national emissions

reductions and providing considerable amounts ofmoney for climate policy in

developing countries.Second,China, India, and Brazilprevented an agreement.

They consistently blocked substantive policy proposals and refused to reciprocate to

Western concessions with any policy commitments of their own. Third, the Copen-

hagen Accord was created as a face-saving device to “greenwash” the absence of a

substantive agreement. The Accord was not adopted due to opposition by several

politically weak countries like Bolivia and Sudan who thwarted an arrangement by

great powers. And while the wee-hour battle over the adoption of the Copenhagen

Accord stole the headlines, this fight should not obscure the more important story

of failing to produce a global climate treaty due to opposition by large developing

country emitters.

The conference was a failure whose magnitude exceeded our worst fears and

the resulting Copenhagen Accord was a desperate attempt to mask that failure.

However,there is a sharp contrast between multilateralclimate governance and

“aggregate” climate governance.Today we face two concurrent realities: the UN

climate processis seriously damaged while aggregate climate policy ismaking

significant progress. All countries with major emissions have ambitious policy plans

for emission reductions,billions of dollars for climate policy are being mobilized,

and subnationalpolicies are thriving.The trajectory ofthe internationalpolicy

path matters more than single conference events, and recent developments display

distinctly positive trends.This contrastbetween a stagnantUN process and a

vibrant multilevelpolicy realm underscores the need for a global“barometer” of

climate policy worldwide thatprovidesa composite measure ofglobal climate

governance (Dimitrov, 2010).

796 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

matic collapse of the conference.3 The final sections summarize the Copenhagen

outcomes, identify policy achievements and failures, and assess the current state of

affairs in global climate politics.

The Short Story

The sheer size of the summit was staggering.There were 37,000 registered

participants including 10,500 government delegates,13,500 observers from civil

society, and 3,000 journalists.4 Security was so tight that the Chinese Minister of the

Environment could not enter the Bella Conference Center for two days because he

had been issued the wrong conference pass.Government delegations conducted

more than 1,000 official and informal meetings over the two weeks and held 300

press conferences.The record number of premiers and ministers required 1,200

limousines and 400 helicopters. And while the world’s attention was justifiably on

Copenhagen,the conference produced perhapsthe most ambiguousoutcome

in diplomatic history, leaving governments and observers alike wondering how to

assess the results (Averchenkova, 2010; Egenhofer & Georgiev, 2009).

The brief story of Copenhagen, in my view, contains three main political devel-

opments.First, Western countriesmade considerable contributionsto a strong

global agreement. All industrialized nations, with the exception of the United States

and Canada, laid the ground for a treaty by offering ambitious national emissions

reductions and providing considerable amounts ofmoney for climate policy in

developing countries.Second,China, India, and Brazilprevented an agreement.

They consistently blocked substantive policy proposals and refused to reciprocate to

Western concessions with any policy commitments of their own. Third, the Copen-

hagen Accord was created as a face-saving device to “greenwash” the absence of a

substantive agreement. The Accord was not adopted due to opposition by several

politically weak countries like Bolivia and Sudan who thwarted an arrangement by

great powers. And while the wee-hour battle over the adoption of the Copenhagen

Accord stole the headlines, this fight should not obscure the more important story

of failing to produce a global climate treaty due to opposition by large developing

country emitters.

The conference was a failure whose magnitude exceeded our worst fears and

the resulting Copenhagen Accord was a desperate attempt to mask that failure.

However,there is a sharp contrast between multilateralclimate governance and

“aggregate” climate governance.Today we face two concurrent realities: the UN

climate processis seriously damaged while aggregate climate policy ismaking

significant progress. All countries with major emissions have ambitious policy plans

for emission reductions,billions of dollars for climate policy are being mobilized,

and subnationalpolicies are thriving.The trajectory ofthe internationalpolicy

path matters more than single conference events, and recent developments display

distinctly positive trends.This contrastbetween a stagnantUN process and a

vibrant multilevelpolicy realm underscores the need for a global“barometer” of

climate policy worldwide thatprovidesa composite measure ofglobal climate

governance (Dimitrov, 2010).

796 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

Background and Context

The Copenhagen conference was the culmination oftwo years ofintense inter-

nationalnegotiations on a new globalclimate agreement.The new treaty would

likely strengthen climate policy through stringent emission reductions in advanced

economies,concrete actions by developing countries,and internationalfinancial

and technological support for climate policy. While the UN is the main negotiation

forum, multilateral discussions take place also at the Major Economies’Forum on

Energy and Climate Change, the G-8 and the G-20 meetings, among others. The

stakes are uniquely high:the widespread consequences ofclimate change mean

political decisions would affect most human communities around the world as well

as future generations.

The Climate Problem

Climate change is the defining challenge of our times, for two reasons. First, it is the

only global problem whose grave consequences occur on a planetary scale and affec

the prosperity and security of allhuman communities.The cumulative economic

impact of climate impacts will be overwhelming. Under a business-as-usual scenario,

climate change can reduce global GDP by 5–20 percent each year (Stern, 2007). The

World Bank calculates globaladaptation costs at 75–100 billion per year between

2010 and 2050 (World Bank, 2009). Second, the policy package required to tackle

the problem has profound socioeconomic consequences. These policies are already

triggering a fundamentaltransformation ofmodern societies toward low-carbon

developmentbased on new energy production and consumption.Quite simply,

climate change and the global policy response to the problem will reshape our world

The realities of global warming now accepted by the global political elite and the

international scientific community threaten economic growth, long-term prosper-

ity,and the physicalsurvivalof human populations.5 Average globaltemperature

has increased by 0.74 degrees Celsius over the course of the twentieth century and

is projected to increase another 1.8–4 degrees according to the best estimate and

possibly up to 6.4 degrees by the end of this century relative to 1980–99 (IPCC,

2007; Schneider,Rosencranz,Mastrandrea,& Kuntz-Duriseti,2010).6 Expected

consequences ofglobal warming include:decline in food production from dis-

ruption of agriculture; water scarcity; human health problems on epidemic scales;

increase in the intensity and frequency of natural disasters; disappearance of sea ice

and elimination ofthe Greenland ice sheet by the latter part ofthe twenty-first

century; sea-level rise and inundation of agricultural lands; and refugee waves.

Rising seas will lead to loss of territory and decline in agriculture affecting the 25

percent of global human populations who live in low-lying coastal areas. Especially

vulnerable are island nations in the Caribbean; Pacific and Indian Oceans; and river

deltas of the Nile, Ganges,and the Mekong where food production is heavily

concentrated (IPCC,2007).Such changes threaten the physicalsurvivalof entire

human communities in low-lying coastal nations like Bangladesh and island states

such as Micronesia, the Maldives Islands, and Samoa.

The consequences are not hypothetical, they are occurring today. Heat-related

casualties in the EU were 35,000 people in the summer of 2003, which is projected

The Copenhagen Conference797

The Copenhagen conference was the culmination oftwo years ofintense inter-

nationalnegotiations on a new globalclimate agreement.The new treaty would

likely strengthen climate policy through stringent emission reductions in advanced

economies,concrete actions by developing countries,and internationalfinancial

and technological support for climate policy. While the UN is the main negotiation

forum, multilateral discussions take place also at the Major Economies’Forum on

Energy and Climate Change, the G-8 and the G-20 meetings, among others. The

stakes are uniquely high:the widespread consequences ofclimate change mean

political decisions would affect most human communities around the world as well

as future generations.

The Climate Problem

Climate change is the defining challenge of our times, for two reasons. First, it is the

only global problem whose grave consequences occur on a planetary scale and affec

the prosperity and security of allhuman communities.The cumulative economic

impact of climate impacts will be overwhelming. Under a business-as-usual scenario,

climate change can reduce global GDP by 5–20 percent each year (Stern, 2007). The

World Bank calculates globaladaptation costs at 75–100 billion per year between

2010 and 2050 (World Bank, 2009). Second, the policy package required to tackle

the problem has profound socioeconomic consequences. These policies are already

triggering a fundamentaltransformation ofmodern societies toward low-carbon

developmentbased on new energy production and consumption.Quite simply,

climate change and the global policy response to the problem will reshape our world

The realities of global warming now accepted by the global political elite and the

international scientific community threaten economic growth, long-term prosper-

ity,and the physicalsurvivalof human populations.5 Average globaltemperature

has increased by 0.74 degrees Celsius over the course of the twentieth century and

is projected to increase another 1.8–4 degrees according to the best estimate and

possibly up to 6.4 degrees by the end of this century relative to 1980–99 (IPCC,

2007; Schneider,Rosencranz,Mastrandrea,& Kuntz-Duriseti,2010).6 Expected

consequences ofglobal warming include:decline in food production from dis-

ruption of agriculture; water scarcity; human health problems on epidemic scales;

increase in the intensity and frequency of natural disasters; disappearance of sea ice

and elimination ofthe Greenland ice sheet by the latter part ofthe twenty-first

century; sea-level rise and inundation of agricultural lands; and refugee waves.

Rising seas will lead to loss of territory and decline in agriculture affecting the 25

percent of global human populations who live in low-lying coastal areas. Especially

vulnerable are island nations in the Caribbean; Pacific and Indian Oceans; and river

deltas of the Nile, Ganges,and the Mekong where food production is heavily

concentrated (IPCC,2007).Such changes threaten the physicalsurvivalof entire

human communities in low-lying coastal nations like Bangladesh and island states

such as Micronesia, the Maldives Islands, and Samoa.

The consequences are not hypothetical, they are occurring today. Heat-related

casualties in the EU were 35,000 people in the summer of 2003, which is projected

The Copenhagen Conference797

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

to be the average summer by 2050. The global food crisis of 2007–08 began when

crops failed on severalcontinentssimultaneously and triggered riotsin many

countries. Between 2006 and 2008 average world prices of rice rose by 217 percent,

wheat by 136 percent, and corn by 125 percent (Steinberg, 2008).

The future is like the present, just longer. The IPCC estimates that crop yields

will decline by up to 20 percent in East and Southeast Asia and 50 percent in some

African countries by 2020 (IPCC, 2007). Water stress will affect 20–25 percent of the

global population and will affect 75–250 million people in Africa alone. Freshwater

will decrease in semi-arid areas such as Southern Europe,western United States,

southern Africa,and north-eastern Brazil.The opposite effectswill take place

in other areas such as Canada,Russia,and most of Asia where precipitation will

increase. More than 20 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters in

the year 2008. Climate-related migration is expected to reach 200 million by 2050,

increasing the likelihood of failed states and violent conflicts over scarce food and

water resources both within and between countries.

Policy Ramifications

To avoid the most catastrophic impacts and limit temperature rise to below 2°C,

advanced economies would need to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions 25–40

percent by 2020, and global emissions need to be reduced 50–80 percent by 2050.

These IPCC-derived goals were officially adopted by developed countries at the G-8

Summit and the Major Economies’ Forum on Energy and Climate. The main causes

of climate change are human activities emitting GHGs such as carbon dioxide,

methane,and nitrous oxides. Main sources of GHGs are energy sectors(26

percent), industrial production (19 percent), forestry (17 percent), and agriculture

(13 percent). Because the root causes of the problem are related to energy, remedial

policies will affect most aspectsof modern societies:agriculture and food

production, industrial manufacturing,transportation,cooling, heating, and

lighting.

The process ofclimate negotiations can lead to major economic and political

changes on a global scale. Strong policies under an ambitious climate treaty would

entaila transition to a low-carbon economy.Many advanced societies are already

embarking on industrialrestructuring for a new mode of development based on

renewable energy,energy efficiency,and green technologies(Schneideret al.,

2010).Climate policies would lift nationaleconomies offtheir current fossil-fuel

platforms and base them on a different energy paradigm.And changing energy

means changing everything.This transition entails a fundamentalsocioeconomic

transformation of the human world and this global transition is the subject matter

of UN negotiations.

The geopolitical ramifications are equally significant. A shift from fossil fuels to

renewable energy coupled with improved energy efficiency would decrease global

demand for oiland increase energy security and economic self-sufficiency in the

West. Today the oil connection between the West and the Middle East is one of the

key pillars in the current structure of global geopolitics. Imagine a world in which

the United States does notneed Middle Eastern oiland Europe does notneed

Russian natural gas. The green shift will create political independence of advanced

798 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

crops failed on severalcontinentssimultaneously and triggered riotsin many

countries. Between 2006 and 2008 average world prices of rice rose by 217 percent,

wheat by 136 percent, and corn by 125 percent (Steinberg, 2008).

The future is like the present, just longer. The IPCC estimates that crop yields

will decline by up to 20 percent in East and Southeast Asia and 50 percent in some

African countries by 2020 (IPCC, 2007). Water stress will affect 20–25 percent of the

global population and will affect 75–250 million people in Africa alone. Freshwater

will decrease in semi-arid areas such as Southern Europe,western United States,

southern Africa,and north-eastern Brazil.The opposite effectswill take place

in other areas such as Canada,Russia,and most of Asia where precipitation will

increase. More than 20 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters in

the year 2008. Climate-related migration is expected to reach 200 million by 2050,

increasing the likelihood of failed states and violent conflicts over scarce food and

water resources both within and between countries.

Policy Ramifications

To avoid the most catastrophic impacts and limit temperature rise to below 2°C,

advanced economies would need to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions 25–40

percent by 2020, and global emissions need to be reduced 50–80 percent by 2050.

These IPCC-derived goals were officially adopted by developed countries at the G-8

Summit and the Major Economies’ Forum on Energy and Climate. The main causes

of climate change are human activities emitting GHGs such as carbon dioxide,

methane,and nitrous oxides. Main sources of GHGs are energy sectors(26

percent), industrial production (19 percent), forestry (17 percent), and agriculture

(13 percent). Because the root causes of the problem are related to energy, remedial

policies will affect most aspectsof modern societies:agriculture and food

production, industrial manufacturing,transportation,cooling, heating, and

lighting.

The process ofclimate negotiations can lead to major economic and political

changes on a global scale. Strong policies under an ambitious climate treaty would

entaila transition to a low-carbon economy.Many advanced societies are already

embarking on industrialrestructuring for a new mode of development based on

renewable energy,energy efficiency,and green technologies(Schneideret al.,

2010).Climate policies would lift nationaleconomies offtheir current fossil-fuel

platforms and base them on a different energy paradigm.And changing energy

means changing everything.This transition entails a fundamentalsocioeconomic

transformation of the human world and this global transition is the subject matter

of UN negotiations.

The geopolitical ramifications are equally significant. A shift from fossil fuels to

renewable energy coupled with improved energy efficiency would decrease global

demand for oiland increase energy security and economic self-sufficiency in the

West. Today the oil connection between the West and the Middle East is one of the

key pillars in the current structure of global geopolitics. Imagine a world in which

the United States does notneed Middle Eastern oiland Europe does notneed

Russian natural gas. The green shift will create political independence of advanced

798 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

economies in the West from OPEC countries in the Middle East, and could increase

the potential for conflict between them.

Existing Agreements

There are two currently existing internationalagreementson climate change.

The first is the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC or

just “the Convention”) that contains no concrete policy obligations. All governments

have ratified the Convention and are bound by its provisions, including a require-

ment that member “Parties” meetonce a year at a Conference of the Parties

(COP) to review progress in policy implementation and renegotiate agreements.

Copenhagen was the fifteenth Conference of the Parties (and commonly referred

to as COP-15).

The second treaty is the 1997 Kyoto Protocolto the UNFCCC that specifies

binding targets for emission reductions in industrialized countries and economies in

transition (Annex I countries).The Protocol exempts developing countries and

imposes mandatory targets for developed countries that would result in aggregate

emission reductions of 5 percent between 1990 and 2012. Individual countries have

differentialemission targets such as 8 percentcuts for the European Union,6

percent for Japan,and 0 percent in Russia.The Protocolalso has provisions for

achieving reductions by emissions trading and green investments in developing

countries (the Clean DevelopmentMechanism)or in other developed countries

( Joint Implementation). The Kyoto protocol came into force in February 2005 and

effectively expires in 2012 when its first “commitment period” ends.

Legal Mandate: The Bali Road Map

Today,governments are busy negotiating new policies beyond 2012.The process

began in 2007 when countries launched the Bali Action Plan that provides the legal

mandate for UN negotiations and establishes the agenda and scope of discussions.

The mandate requiresgovernmentsto produce an agreementcontaining four

building blocks of policies: mitigation (GHG emissions reductions), adaptation (to

the consequences of climate change),and financialand technologicalsupport for

developing country actions (Clémençon, 2008).

The Bali Action Plan stipulates a two-track approach to negotiations and two

parallel processes offormal negotiations are currently under way.One aims at

renegotiating emission reductionsby industrialized countriesunder the Kyoto

Protocol. This “Kyoto track” was launched in December 2005 and conducted in the

Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the

Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP). The second, “Convention track” is a broader reconsid-

eration of long-term commitments by all countries, including developing countries.

It was launched in December 2007 and negotiations take place in the Ad Hoc

Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA).

The AWG-KP and AWG-LCA are legally separate butpolitically intertwined.

They work parallelto each other in the same building ateach conference and

involve more or less the same negotiators from government delegations. A serious

political obstacle to progress was the reluctance of either group to complete its work

The Copenhagen Conference799

the potential for conflict between them.

Existing Agreements

There are two currently existing internationalagreementson climate change.

The first is the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC or

just “the Convention”) that contains no concrete policy obligations. All governments

have ratified the Convention and are bound by its provisions, including a require-

ment that member “Parties” meetonce a year at a Conference of the Parties

(COP) to review progress in policy implementation and renegotiate agreements.

Copenhagen was the fifteenth Conference of the Parties (and commonly referred

to as COP-15).

The second treaty is the 1997 Kyoto Protocolto the UNFCCC that specifies

binding targets for emission reductions in industrialized countries and economies in

transition (Annex I countries).The Protocol exempts developing countries and

imposes mandatory targets for developed countries that would result in aggregate

emission reductions of 5 percent between 1990 and 2012. Individual countries have

differentialemission targets such as 8 percentcuts for the European Union,6

percent for Japan,and 0 percent in Russia.The Protocolalso has provisions for

achieving reductions by emissions trading and green investments in developing

countries (the Clean DevelopmentMechanism)or in other developed countries

( Joint Implementation). The Kyoto protocol came into force in February 2005 and

effectively expires in 2012 when its first “commitment period” ends.

Legal Mandate: The Bali Road Map

Today,governments are busy negotiating new policies beyond 2012.The process

began in 2007 when countries launched the Bali Action Plan that provides the legal

mandate for UN negotiations and establishes the agenda and scope of discussions.

The mandate requiresgovernmentsto produce an agreementcontaining four

building blocks of policies: mitigation (GHG emissions reductions), adaptation (to

the consequences of climate change),and financialand technologicalsupport for

developing country actions (Clémençon, 2008).

The Bali Action Plan stipulates a two-track approach to negotiations and two

parallel processes offormal negotiations are currently under way.One aims at

renegotiating emission reductionsby industrialized countriesunder the Kyoto

Protocol. This “Kyoto track” was launched in December 2005 and conducted in the

Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the

Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP). The second, “Convention track” is a broader reconsid-

eration of long-term commitments by all countries, including developing countries.

It was launched in December 2007 and negotiations take place in the Ad Hoc

Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA).

The AWG-KP and AWG-LCA are legally separate butpolitically intertwined.

They work parallelto each other in the same building ateach conference and

involve more or less the same negotiators from government delegations. A serious

political obstacle to progress was the reluctance of either group to complete its work

The Copenhagen Conference799

before the other:industrialized countriesin AWG-KP would not finalize their

commitments before guarantees of developing country commitments in AWG-LCA.

Similarly,developing countries insist on finalizing the AWG-KP talks on Western

obligations before making commitments themselves. In Copenhagen, the two nego-

tiation tracks were presumably supposed to come together for a trade-off of policy

commitments between developed and developing countries.

Key Issues under Negotiation

What do states argue about in climate talks? The building blocks of the next treaty

under negotiation are: policies for mitigation (i.e., reducing GHG emissions), adap-

tation (to the consequences ofclimate change),and financialand technological

support for developing country actions.The negotiations address a large range

of highly technicalpolicy issues detailed better elsewhere (Fry,2008;Kulovesi&

Gutiérrez,2009; Rajamani,2009).Here, I focus on the broader politicaldebates

regarding what to do, who should do it and how, and who would pay for it.

Global Policy Targets

A fundamental disagreement pertains to the overall goal of the global policy effort.

Article 2 of the UNFCCC states the goalis to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic

interference” but leaves the meaning of “dangerous” to subjective interpretation.

All Western countries,China, India, Brazil, and others support limiting average

globaltemperature rise to 2°C above 1,900 levels thatwould require restricting

concentrations of atmospheric carbon to 450 ppm (parts per million). The Alliance

of Small Island States,and many other vulnerable countries insist on 1.5°C and

carbon concentrations below 350 ppm,respectively.According to a Plenary state-

ment by Grenada,up to 100 countries or half of UN membership endorse that

goal. Finally, the ALBA group of Latin American countries support an even more

ambitious limit to temperature rise of 1°C.7

Legal Architecture

The legal nature of the next climate agreement is a matter of considerable conse-

quence. The negotiation output could be a new treaty, an amendment to the Kyoto

Protocol, a nonbinding political declaration, or a set of legally binding “decisions”

by the Conference of the Parties. A big fight in global climate politics is whether to

negotiate one or two climate change agreements.Most Western countries (and

especially Japan,Russia,and Canada) demand a single globaltreaty binding all

major emitters in developed and developing countries alike (read China and India)

that could entaila long ratification process.Developing countries demand two

separate agreementsand insist on renegotiating the Kyoto Protocolfirst, with

policies for a second commitment period beyond 2012 (Kyoto 2). Indeed, replacing

Kyoto altogether would likely leave a gap in climate governance since a new treaty

would require a prolonged ratification process that may take many years and whose

outcome is uncertain.

800 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

commitments before guarantees of developing country commitments in AWG-LCA.

Similarly,developing countries insist on finalizing the AWG-KP talks on Western

obligations before making commitments themselves. In Copenhagen, the two nego-

tiation tracks were presumably supposed to come together for a trade-off of policy

commitments between developed and developing countries.

Key Issues under Negotiation

What do states argue about in climate talks? The building blocks of the next treaty

under negotiation are: policies for mitigation (i.e., reducing GHG emissions), adap-

tation (to the consequences ofclimate change),and financialand technological

support for developing country actions.The negotiations address a large range

of highly technicalpolicy issues detailed better elsewhere (Fry,2008;Kulovesi&

Gutiérrez,2009; Rajamani,2009).Here, I focus on the broader politicaldebates

regarding what to do, who should do it and how, and who would pay for it.

Global Policy Targets

A fundamental disagreement pertains to the overall goal of the global policy effort.

Article 2 of the UNFCCC states the goalis to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic

interference” but leaves the meaning of “dangerous” to subjective interpretation.

All Western countries,China, India, Brazil, and others support limiting average

globaltemperature rise to 2°C above 1,900 levels thatwould require restricting

concentrations of atmospheric carbon to 450 ppm (parts per million). The Alliance

of Small Island States,and many other vulnerable countries insist on 1.5°C and

carbon concentrations below 350 ppm,respectively.According to a Plenary state-

ment by Grenada,up to 100 countries or half of UN membership endorse that

goal. Finally, the ALBA group of Latin American countries support an even more

ambitious limit to temperature rise of 1°C.7

Legal Architecture

The legal nature of the next climate agreement is a matter of considerable conse-

quence. The negotiation output could be a new treaty, an amendment to the Kyoto

Protocol, a nonbinding political declaration, or a set of legally binding “decisions”

by the Conference of the Parties. A big fight in global climate politics is whether to

negotiate one or two climate change agreements.Most Western countries (and

especially Japan,Russia,and Canada) demand a single globaltreaty binding all

major emitters in developed and developing countries alike (read China and India)

that could entaila long ratification process.Developing countries demand two

separate agreementsand insist on renegotiating the Kyoto Protocolfirst, with

policies for a second commitment period beyond 2012 (Kyoto 2). Indeed, replacing

Kyoto altogether would likely leave a gap in climate governance since a new treaty

would require a prolonged ratification process that may take many years and whose

outcome is uncertain.

800 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Who Should Take Action

The globaldivision of labor in mitigating climate change is the most contentious

issue in the talks as global competitiveness concerns generate prolonged debates on

“comparability of efforts” and a “shared vision” for long-term policy goals. The high

economic stakes and policy costs generate acute relative gains concerns: everyone

demands guarantees ofcomparable emission reductions in other countries,and

attribute paramount importance to transparency in verifying compliance.

Developing Country Actions—The terms of participation by developing countries in

internationalclimate policy have been a major theme in the lasttwo decades.

Governments embrace the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”

enshrined in the Convention but disagree on what “common” means. While aggre-

gate emissions from industrialized countries since the 18th century are the main

cause of the problem, roughly 50 percent of current emissions originate in devel-

oping countries. China, India, and Brazil’s participation is therefore indispensable

for avoiding catastrophic climate impacts. Developed countries acknowledge their

historic responsibility for pastemissionsand agree to take the lead but insist

everyone must take some action. Today everyone agrees to let developing countries

choose their policies freely but whether these “nationally appropriate mitigation

actions” should be quantified, measured and reported (MRV) to the international

community to provide transparency and ensure compliance remains contentious.8

Developed Country Actions—New,quantified economy-wide emission reductions in

advanced economies will be a centerpiece of future climate policy and the size and

timing of such reductions is under negotiation. The EU and many other countries

endorse 25–40 percent cuts by 2020 as consistent with the IPCC estimate and 80–95

percent by 2050.Central American countries support 45 percent by 2020 while

Bolivia, Cuba, and others demand 49 percentreductions.States argue intransi-

gently about the method of determining targets. Industrialized countries generally

support a “bottom-up” approach wherein governmentsdetermine their own

national goals. Developing countries prefer a “top-down,” science-based approach

that guaranteesenvironmentalresultsby fixing aggregate emission reductions

necessary to preventtemperature rise above 2°C or 1.5°C and then negotiating

individual countries’share of the burden.

Mitigation Policy Options—The UN process involves highly technical discussions on

mechanisms for policy implementation and accounting rules, including: emissions

trading, national emission caps, energy intensity targets, sectoral approaches, poli-

cies and measures such as a carbon tax, land use and land use change (LULUCF),

and reducing emissions from deforestation (Bodansky, 2003). The role of interna-

tional “offsets” is an ever-present theme and concerns whether advanced economie

must reduce emissionsby strictly domestic actionsor be permitted to finance

emission cuts in developing countries and receive credit.One point of political

consensus is that forestry (accounting for 17 percent of globalemissions and 50

percentof the mitigation potential)providesa cost-effective way to ameliorate

climate change and will be an integral part of the new climate agreement. Devel-

The Copenhagen Conference801

The globaldivision of labor in mitigating climate change is the most contentious

issue in the talks as global competitiveness concerns generate prolonged debates on

“comparability of efforts” and a “shared vision” for long-term policy goals. The high

economic stakes and policy costs generate acute relative gains concerns: everyone

demands guarantees ofcomparable emission reductions in other countries,and

attribute paramount importance to transparency in verifying compliance.

Developing Country Actions—The terms of participation by developing countries in

internationalclimate policy have been a major theme in the lasttwo decades.

Governments embrace the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”

enshrined in the Convention but disagree on what “common” means. While aggre-

gate emissions from industrialized countries since the 18th century are the main

cause of the problem, roughly 50 percent of current emissions originate in devel-

oping countries. China, India, and Brazil’s participation is therefore indispensable

for avoiding catastrophic climate impacts. Developed countries acknowledge their

historic responsibility for pastemissionsand agree to take the lead but insist

everyone must take some action. Today everyone agrees to let developing countries

choose their policies freely but whether these “nationally appropriate mitigation

actions” should be quantified, measured and reported (MRV) to the international

community to provide transparency and ensure compliance remains contentious.8

Developed Country Actions—New,quantified economy-wide emission reductions in

advanced economies will be a centerpiece of future climate policy and the size and

timing of such reductions is under negotiation. The EU and many other countries

endorse 25–40 percent cuts by 2020 as consistent with the IPCC estimate and 80–95

percent by 2050.Central American countries support 45 percent by 2020 while

Bolivia, Cuba, and others demand 49 percentreductions.States argue intransi-

gently about the method of determining targets. Industrialized countries generally

support a “bottom-up” approach wherein governmentsdetermine their own

national goals. Developing countries prefer a “top-down,” science-based approach

that guaranteesenvironmentalresultsby fixing aggregate emission reductions

necessary to preventtemperature rise above 2°C or 1.5°C and then negotiating

individual countries’share of the burden.

Mitigation Policy Options—The UN process involves highly technical discussions on

mechanisms for policy implementation and accounting rules, including: emissions

trading, national emission caps, energy intensity targets, sectoral approaches, poli-

cies and measures such as a carbon tax, land use and land use change (LULUCF),

and reducing emissions from deforestation (Bodansky, 2003). The role of interna-

tional “offsets” is an ever-present theme and concerns whether advanced economie

must reduce emissionsby strictly domestic actionsor be permitted to finance

emission cuts in developing countries and receive credit.One point of political

consensus is that forestry (accounting for 17 percent of globalemissions and 50

percentof the mitigation potential)providesa cost-effective way to ameliorate

climate change and will be an integral part of the new climate agreement. Devel-

The Copenhagen Conference801

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

oping countries regard reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degrada-

tion (REDD) as a future source of financial rewards (money in exchange for forest

protection) and eagerly negotiate eligible forest activities, accounting mechanisms,

and institutional arrangements (Fry, 2008).

Adaptation—Developing countries seek a comprehensive globaladaptation frame-

work that provides financialsupport for coping with naturaldisasters and other

climate change impacts. An Adaptation Fund under the Kyoto Protocol is fed by a

2 percent levy on transactions under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

Current talks focus on a possible second fund under the Convention,levels of

funding, developmentof nationaladaptation plans,an internationalinsurance

mechanism for loss and damage, and how to differentiate adaptation activities from

development policy for purposes of funding.

Finance—The World Bank estimates the costs of adapting to a 2-degree temperature

rise at 75–100 billion dollars per year between 2010 and 2050. Climate mitigation

policies in developing countries alone require 140 to 175 billion dollars per year

in the next 20 years (World Bank, 2010). All industrialized countries endorsed an

estimate by the European Union to provide 100 billion per year by 2020.Least

developed countries suggest at least 1.5 percent of GDP that is additional to official

development assistance9 while the ALBA group suggested financial contributions by

developed countries of 6 percent of their GDP.

Apart from the level of funding, countries also debate sources of funding: market

mechanisms and private investment (as preferred by developed countries) or public

funds (advocated by developing countries). Proposals include: a global carbon tax

around $2/tonne (Switzerland);auction ofemission allowances to raise revenue

(Norway); and a Green Fund financed through assessed contributions by developed

countries (Mexico). The third debate is on the “chicken-or-egg” question of timing:

whether policy actions by developing countries are contingent on prior Western

funding, or whether funding is offered after actual policy development.

TechnologyTransfer—The developmentand dissemination ofclean technologies

are central to long-term solutions. Vigorous discussions address the role of research

and development and intellectual property rights (IPRs), market access, and tech-

nology financing. Developing country proposals include a multilateral technology

fund, compulsory licensing,patent pooling,and government incentives for tech-

nology transfer to developing countries. Developed countries uphold the current

IPR regime, firmly reject the proposed technology fund,and propose globalor

regional centers for exchange of information.

Positions of Key Players

The European Union

Considered the globalleader on climate policy,the EU advocates a strong global

agreement with stringent economy-wide emissions reductions, substantial financial

support, and robust compliance mechanisms. Europeans stress “win-win” solutions

802 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

tion (REDD) as a future source of financial rewards (money in exchange for forest

protection) and eagerly negotiate eligible forest activities, accounting mechanisms,

and institutional arrangements (Fry, 2008).

Adaptation—Developing countries seek a comprehensive globaladaptation frame-

work that provides financialsupport for coping with naturaldisasters and other

climate change impacts. An Adaptation Fund under the Kyoto Protocol is fed by a

2 percent levy on transactions under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

Current talks focus on a possible second fund under the Convention,levels of

funding, developmentof nationaladaptation plans,an internationalinsurance

mechanism for loss and damage, and how to differentiate adaptation activities from

development policy for purposes of funding.

Finance—The World Bank estimates the costs of adapting to a 2-degree temperature

rise at 75–100 billion dollars per year between 2010 and 2050. Climate mitigation

policies in developing countries alone require 140 to 175 billion dollars per year

in the next 20 years (World Bank, 2010). All industrialized countries endorsed an

estimate by the European Union to provide 100 billion per year by 2020.Least

developed countries suggest at least 1.5 percent of GDP that is additional to official

development assistance9 while the ALBA group suggested financial contributions by

developed countries of 6 percent of their GDP.

Apart from the level of funding, countries also debate sources of funding: market

mechanisms and private investment (as preferred by developed countries) or public

funds (advocated by developing countries). Proposals include: a global carbon tax

around $2/tonne (Switzerland);auction ofemission allowances to raise revenue

(Norway); and a Green Fund financed through assessed contributions by developed

countries (Mexico). The third debate is on the “chicken-or-egg” question of timing:

whether policy actions by developing countries are contingent on prior Western

funding, or whether funding is offered after actual policy development.

TechnologyTransfer—The developmentand dissemination ofclean technologies

are central to long-term solutions. Vigorous discussions address the role of research

and development and intellectual property rights (IPRs), market access, and tech-

nology financing. Developing country proposals include a multilateral technology

fund, compulsory licensing,patent pooling,and government incentives for tech-

nology transfer to developing countries. Developed countries uphold the current

IPR regime, firmly reject the proposed technology fund,and propose globalor

regional centers for exchange of information.

Positions of Key Players

The European Union

Considered the globalleader on climate policy,the EU advocates a strong global

agreement with stringent economy-wide emissions reductions, substantial financial

support, and robust compliance mechanisms. Europeans stress “win-win” solutions

802 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

to climate change that benefit the economy and the environment,and economic

advantage from energy savings and clean technologies.In Copenhagen,the EU

stated:

European Union: Let us agree to the 2 degree objective and to global emissions reductions

of at least 50 percent as well as aggregate developed emission reductions of at least 80–95

percentby 2050 compared to 1990 levels,and in the order of 30 percentby 2020.

Developing countries as a group should committo actions thatachieve a substantial

deviation below the currently predicted emissionsgrowth rate in the order 15–30

percent.10

On international finance, Europe has the most detailed position among indus-

trialized countries and pledged to provide 2 to 15 billion Euros per year by 2020.

Their position was outlined in their opening statement:

European Union:The net incrementalcost for adaptation and mitigation has been esti-

mated at around 100 billion Euros per annum in developing countries by 2020, including

internationalpublic supportin the range of22–50 billion Euros.All countries,except

the least developed,should contribute to such internationalpublic financing through a

comprehensive, global distribution key based on emission levels and GDP.

In 2007 Europe committed to unilateral20 percentcuts by 2020 compared

to 1990 regardlessof negotiation outcomes,and up to 30 percentif other major

economies reciprocate.In December 2008,the European Parliamentapproved

their “Energy and Climate” policy package that became law in June 2009 and is now

legally binding on its 27 country members.The European Commission expects

savings of 100 billion Euro per year from improved energy efficiency,50 billion

from reduced oil exports and projects 1 million new jobs in green industries.11

The Umbrella Group consists ofAustralia,Canada,Iceland, Japan, Kazakhstan,

New Zealand, Norway, Russian Federation, the Ukraine, and the United States who

seek to coordinate positions and deliver common statements.The group wants a

single global legally binding treaty that locks major emitters into transparent actions

that are subject to internationalverification.Their opening statement in Copen-

hagen, delivered by Australia, summarized the group’s preferences

Madame President, we, the Umbrella Group, want a success at Copenhagen. In fact, we

want a resounding success. . . . Our vision is simple: we recognize the scientific view that

the increase in global average temperature above pre-industrial levels ought not to exceed

2 degrees Celsius. We want a global outcome that puts the world on a path to 50 percent

reduction in emissions by 2050,and peaking emissions as soon as possible.We want all

countries to act according to their national ability . . . in the context of post-2012 outcome

we’re resolved to support quick, substantial and high-impact financing to assist the most

vulnerable developing countries, both from public and private funding sources, including

carbon markets.

The United States cannot participate in renegotiating the Kyoto Protocolin the

AWG-KP talks because they have not ratified the Protocol. After having stayed out

of the climate regime during the Bush years, the United States changed course in

2009 and now seeks a comprehensive agreement involving all countries, reliance on

market mechanisms and existing global financial institutions, low-carbon technol-

ogy research and development, and a global “climate technology hub” for exchange

of information on clean technologies. Domestically, the Barack Obama administra-

The Copenhagen Conference803

advantage from energy savings and clean technologies.In Copenhagen,the EU

stated:

European Union: Let us agree to the 2 degree objective and to global emissions reductions

of at least 50 percent as well as aggregate developed emission reductions of at least 80–95

percentby 2050 compared to 1990 levels,and in the order of 30 percentby 2020.

Developing countries as a group should committo actions thatachieve a substantial

deviation below the currently predicted emissionsgrowth rate in the order 15–30

percent.10

On international finance, Europe has the most detailed position among indus-

trialized countries and pledged to provide 2 to 15 billion Euros per year by 2020.

Their position was outlined in their opening statement:

European Union:The net incrementalcost for adaptation and mitigation has been esti-

mated at around 100 billion Euros per annum in developing countries by 2020, including

internationalpublic supportin the range of22–50 billion Euros.All countries,except

the least developed,should contribute to such internationalpublic financing through a

comprehensive, global distribution key based on emission levels and GDP.

In 2007 Europe committed to unilateral20 percentcuts by 2020 compared

to 1990 regardlessof negotiation outcomes,and up to 30 percentif other major

economies reciprocate.In December 2008,the European Parliamentapproved

their “Energy and Climate” policy package that became law in June 2009 and is now

legally binding on its 27 country members.The European Commission expects

savings of 100 billion Euro per year from improved energy efficiency,50 billion

from reduced oil exports and projects 1 million new jobs in green industries.11

The Umbrella Group consists ofAustralia,Canada,Iceland, Japan, Kazakhstan,

New Zealand, Norway, Russian Federation, the Ukraine, and the United States who

seek to coordinate positions and deliver common statements.The group wants a

single global legally binding treaty that locks major emitters into transparent actions

that are subject to internationalverification.Their opening statement in Copen-

hagen, delivered by Australia, summarized the group’s preferences

Madame President, we, the Umbrella Group, want a success at Copenhagen. In fact, we

want a resounding success. . . . Our vision is simple: we recognize the scientific view that

the increase in global average temperature above pre-industrial levels ought not to exceed

2 degrees Celsius. We want a global outcome that puts the world on a path to 50 percent

reduction in emissions by 2050,and peaking emissions as soon as possible.We want all

countries to act according to their national ability . . . in the context of post-2012 outcome

we’re resolved to support quick, substantial and high-impact financing to assist the most

vulnerable developing countries, both from public and private funding sources, including

carbon markets.

The United States cannot participate in renegotiating the Kyoto Protocolin the

AWG-KP talks because they have not ratified the Protocol. After having stayed out

of the climate regime during the Bush years, the United States changed course in

2009 and now seeks a comprehensive agreement involving all countries, reliance on

market mechanisms and existing global financial institutions, low-carbon technol-

ogy research and development, and a global “climate technology hub” for exchange

of information on clean technologies. Domestically, the Barack Obama administra-

The Copenhagen Conference803

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

tion seeks a nationalpolicy to reduce emissions by 17 percentby 2020 and 83

percent by 2050, compared to 2005 levels.

Japan also made a U-turn on domestic emission reductions. In September 2009,

the Hatoyama governmentannounced plans to reduce its own emissions by 25

percent below 1990 levels by 2020, contingent on a global policy framework involv-

ing all major economies. Japan favors “sectoral approaches” to emission reductions,

that is, international agreement to target particular economic sectors and thus allay

competitiveness concerns for those sectors. The Japanese are strongly against Kyoto

2 but appear committed to creating an ambitious new treaty and generally played

a constructive role in the talks. At Copenhagen they provided 11 billion dollars of

public funding for internationalpolicy,and the head of their delegation spoke

earnestly and passionately when he said:

Japan: We are here neither to accuse each other nor to blame each other.We are here

assembled to do our utmost to save the Earth. It is shameful of ourselves condemning each

other. The whole world is watching us. Our delegation has grave concerns on the life and

death threat facing small islands, vulnerable countries on the surface of the Earth. We are

here not just to save these nations but also to save ourselves, our children and our future

generation.

The Russian Federation is generally uninvolved in debates and rarely takes the floor

to make statements. They advocate voluntary bottom-up approaches that allow each

country to determine so-called “no-lose” targets whose achievement would bring

rewards butwherein noncompliance brings no penalties.Domestically,Russia is

currently considering national emission reduction goals.

Developing countriesnegotiate effectively asa powerful coalition (the G-77/

China).12 They are united in advocating Kyoto 2 with stringent binding policy in the

North, voluntary policy in the South, substantial international financial and tech-

nological support, and no MRV for policies that are unsupported internationally.

The G-77 demand firm legal obligations for developed economies before making any

policy commitments themselves, and decry demands for a global treaty as attempts

by industrialized nations to “destroy Kyoto” and shun their historical responsibility

for global warming. Delivering a formal opening statement on behalf of the coali-

tion (G-77), Sudan stated:

G-77/China: We reject attempts of developed countries to shift the responsibility of address-

ing climate change and its adverse effects on developing countries, and we equally object

to their objective of concluding anotherlegally-binding instrumentthat would put

together the obligationsof developed countriesunder the KP and similar actionsof

developing countries.This would revoke the principle of“common,but differentiated

responsibilities” and “historicalresponsibility” under the Convention by imposing these

obligations as well on developing countries under the guise of a “shared-vision.”

The coalition is fractured by fundamentalconflictsof interestamong heavy

industrial emitters like China and India, forested countries, fossil-dependent OPEC

members,and the Alliance of Small Island Nations (AOSIS). These conflicting

interests are deliberately suppressed for the sake of unity but they ruptured the

coalition in Copenhagen.

Brazil,South Africa,India,and China (the BASIC group) are heavyweight GHG

emitters with strong influence on the G-77 coalition. Unlike other G-77 members

804 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

percent by 2050, compared to 2005 levels.

Japan also made a U-turn on domestic emission reductions. In September 2009,

the Hatoyama governmentannounced plans to reduce its own emissions by 25

percent below 1990 levels by 2020, contingent on a global policy framework involv-

ing all major economies. Japan favors “sectoral approaches” to emission reductions,

that is, international agreement to target particular economic sectors and thus allay

competitiveness concerns for those sectors. The Japanese are strongly against Kyoto

2 but appear committed to creating an ambitious new treaty and generally played

a constructive role in the talks. At Copenhagen they provided 11 billion dollars of

public funding for internationalpolicy,and the head of their delegation spoke

earnestly and passionately when he said:

Japan: We are here neither to accuse each other nor to blame each other.We are here

assembled to do our utmost to save the Earth. It is shameful of ourselves condemning each

other. The whole world is watching us. Our delegation has grave concerns on the life and

death threat facing small islands, vulnerable countries on the surface of the Earth. We are

here not just to save these nations but also to save ourselves, our children and our future

generation.

The Russian Federation is generally uninvolved in debates and rarely takes the floor

to make statements. They advocate voluntary bottom-up approaches that allow each

country to determine so-called “no-lose” targets whose achievement would bring

rewards butwherein noncompliance brings no penalties.Domestically,Russia is

currently considering national emission reduction goals.

Developing countriesnegotiate effectively asa powerful coalition (the G-77/

China).12 They are united in advocating Kyoto 2 with stringent binding policy in the

North, voluntary policy in the South, substantial international financial and tech-

nological support, and no MRV for policies that are unsupported internationally.

The G-77 demand firm legal obligations for developed economies before making any

policy commitments themselves, and decry demands for a global treaty as attempts

by industrialized nations to “destroy Kyoto” and shun their historical responsibility

for global warming. Delivering a formal opening statement on behalf of the coali-

tion (G-77), Sudan stated:

G-77/China: We reject attempts of developed countries to shift the responsibility of address-

ing climate change and its adverse effects on developing countries, and we equally object

to their objective of concluding anotherlegally-binding instrumentthat would put

together the obligationsof developed countriesunder the KP and similar actionsof

developing countries.This would revoke the principle of“common,but differentiated

responsibilities” and “historicalresponsibility” under the Convention by imposing these

obligations as well on developing countries under the guise of a “shared-vision.”

The coalition is fractured by fundamentalconflictsof interestamong heavy

industrial emitters like China and India, forested countries, fossil-dependent OPEC

members,and the Alliance of Small Island Nations (AOSIS). These conflicting

interests are deliberately suppressed for the sake of unity but they ruptured the

coalition in Copenhagen.

Brazil,South Africa,India,and China (the BASIC group) are heavyweight GHG

emitters with strong influence on the G-77 coalition. Unlike other G-77 members

804 Radoslav S. Dimitrov

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

who emphasize internationalfinancialand technologicalsupport, money is not

their priority: BASIC countries want freedom of nationaleconomic development

unencumbered by legaltreaty obligations.They insist their actionsshould be

discussed after finalizing negotiations on developed country actions.Notably,all

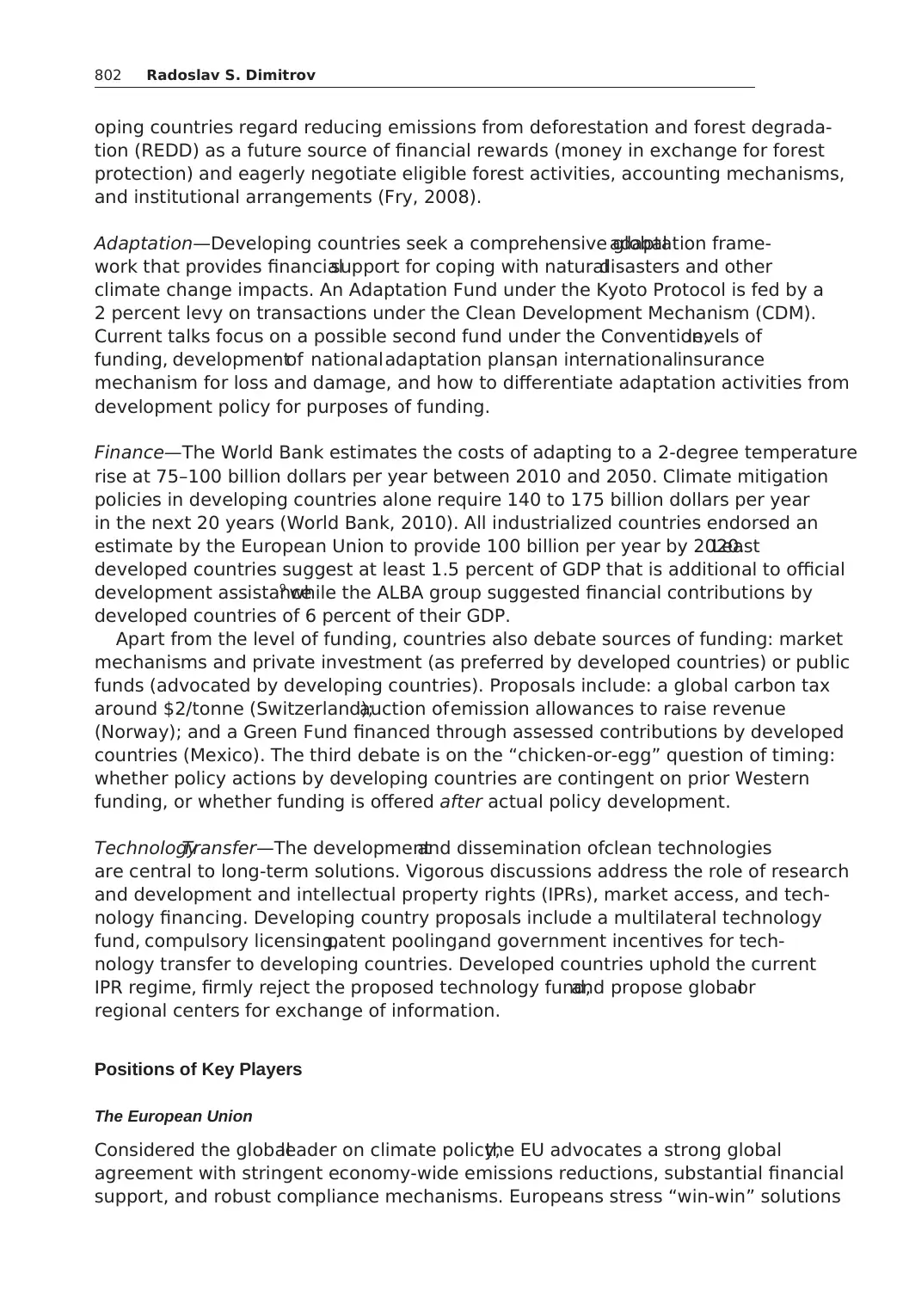

four appear positioned to take domestic action (see Table 1). The year 2009 marks

the first time in the history ofclimate negotiations developing country emitters

accepted the idea of quantified targets. China, for instance, plans for 40–45 percent

cuts in carbon dioxide emission intensity of GDP and derive 15 percent of their

energy from renewable sources and nuclear by 2020.

Indonesia, Congo, Brazil, and other heavily forested countries can reap consider-

able financialbenefitsfrom a global agreementrewarding forestconservation

for the sake ofclimate change abatement.They carefully negotiate institutional

arrangements and financialdetails and,given the rightincentives,would break

ranks with the G-77 on the need for developing country actions. Saudi Arabia, on

the other hand,seeks to obstruct negotiations in every possible way,engaging in

diplomatic carpet-bombing ofsorts.Heavy reliance on fossilfuels makestheir

economy extremely vulnerable to prospective energy efficiency and alternative

energy policies. Their delegation champions discussions on negative consequences

of climate policy and compensation for “spillover effects” of low-carbon develop-

ment strategies in advanced economies.

The Alliance ofSmallIsland Stateswant action as strong and swiftas possible,

due to their extreme vulnerability to sea levelrise. The group includes some of

the most proactive players in the negotiations, and many of the innovative policy

ideasand key substantive textproposalscome from the delegationsof Tuvalu

and Micronesia.AOSIS advocate 45 percent emission cuts by 2020 and limiting

global temperature increase to below 1.5 C. On the opening day of Copenhagen,

Grenada stated:

Alliance of Small Island States: We have a moral imperative to act. All of us face this. But as

small island states going under water,losing our territorialintegrity,facing increased

poverty, and frankly, given that our very survival is threatened, we stand to lose the most

if nothing happens here. . . . A final agreement has to address emissions reductions by all

major emitting countries based on the principle of “common, but differentiated respon-

sibilities.” This is critical and this requires a limit to temperature rise to no more than 1.5

degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which then requires greenhouse gas concen-

trations to be returned to 350 parts per million . . . Madame,AOSIS will not accepta

made-for-television solution.

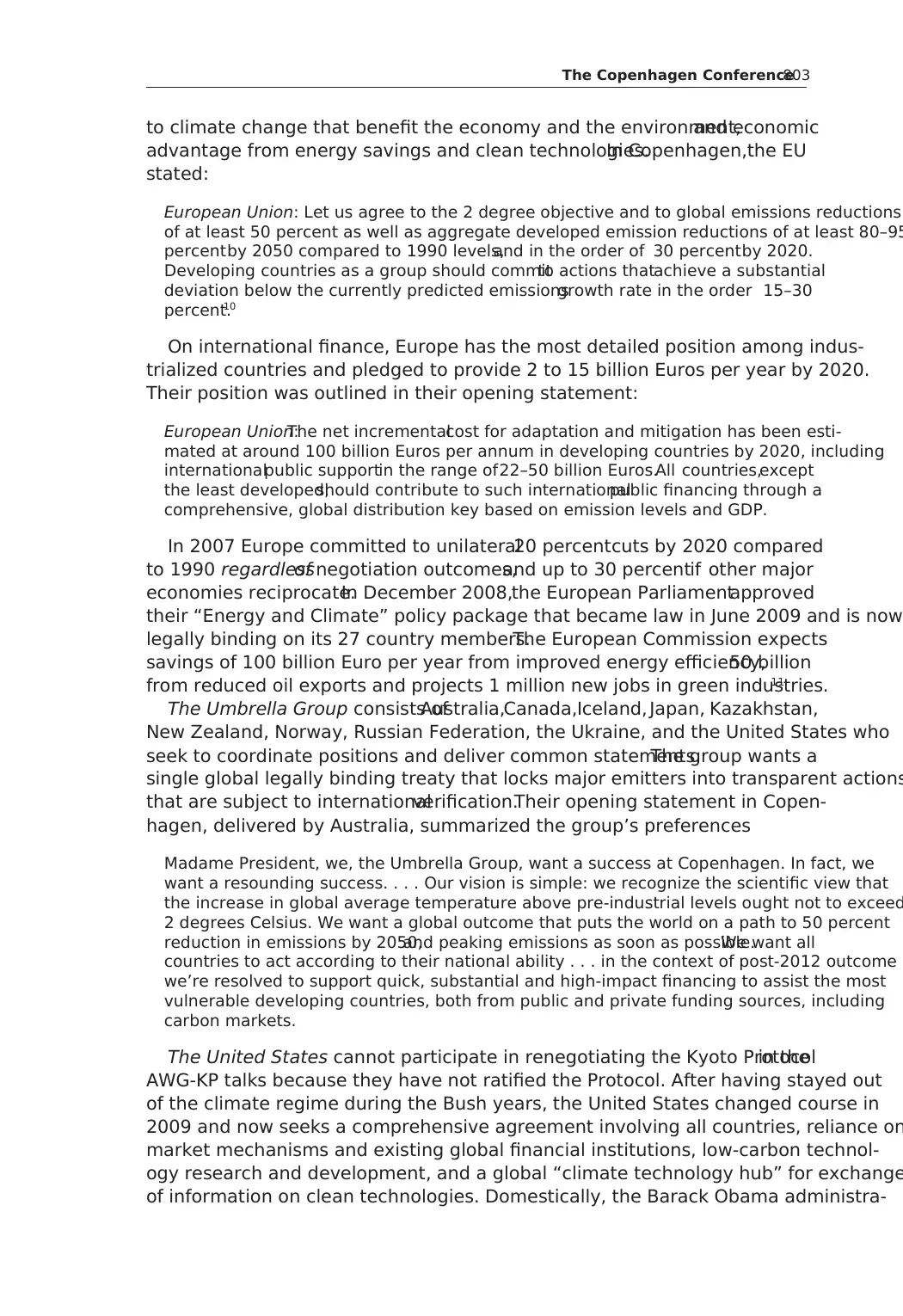

Table 1.National Policy Plans by Major Developing Country

Emitters.

Country Policy Plan by 2020

Brazil 36–39% emission reductions below 1994

China 40–45% cuts in carbon dioxide emission intensity of

GDP and 15% renewable energy share of energy

consumption

India 20–25% cuts in emission intensity of GDP

Korea 30% cuts below 1990

Mexico 30% cuts below 1990

South Africa 34% cuts below current levels

The Copenhagen Conference805

their priority: BASIC countries want freedom of nationaleconomic development

unencumbered by legaltreaty obligations.They insist their actionsshould be

discussed after finalizing negotiations on developed country actions.Notably,all

four appear positioned to take domestic action (see Table 1). The year 2009 marks

the first time in the history ofclimate negotiations developing country emitters

accepted the idea of quantified targets. China, for instance, plans for 40–45 percent

cuts in carbon dioxide emission intensity of GDP and derive 15 percent of their

energy from renewable sources and nuclear by 2020.

Indonesia, Congo, Brazil, and other heavily forested countries can reap consider-

able financialbenefitsfrom a global agreementrewarding forestconservation

for the sake ofclimate change abatement.They carefully negotiate institutional

arrangements and financialdetails and,given the rightincentives,would break

ranks with the G-77 on the need for developing country actions. Saudi Arabia, on

the other hand,seeks to obstruct negotiations in every possible way,engaging in

diplomatic carpet-bombing ofsorts.Heavy reliance on fossilfuels makestheir

economy extremely vulnerable to prospective energy efficiency and alternative

energy policies. Their delegation champions discussions on negative consequences

of climate policy and compensation for “spillover effects” of low-carbon develop-

ment strategies in advanced economies.

The Alliance ofSmallIsland Stateswant action as strong and swiftas possible,

due to their extreme vulnerability to sea levelrise. The group includes some of

the most proactive players in the negotiations, and many of the innovative policy

ideasand key substantive textproposalscome from the delegationsof Tuvalu

and Micronesia.AOSIS advocate 45 percent emission cuts by 2020 and limiting

global temperature increase to below 1.5 C. On the opening day of Copenhagen,

Grenada stated:

Alliance of Small Island States: We have a moral imperative to act. All of us face this. But as

small island states going under water,losing our territorialintegrity,facing increased

poverty, and frankly, given that our very survival is threatened, we stand to lose the most

if nothing happens here. . . . A final agreement has to address emissions reductions by all

major emitting countries based on the principle of “common, but differentiated respon-

sibilities.” This is critical and this requires a limit to temperature rise to no more than 1.5

degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which then requires greenhouse gas concen-

trations to be returned to 350 parts per million . . . Madame,AOSIS will not accepta

made-for-television solution.

Table 1.National Policy Plans by Major Developing Country

Emitters.

Country Policy Plan by 2020

Brazil 36–39% emission reductions below 1994

China 40–45% cuts in carbon dioxide emission intensity of

GDP and 15% renewable energy share of energy

consumption

India 20–25% cuts in emission intensity of GDP

Korea 30% cuts below 1990

Mexico 30% cuts below 1990

South Africa 34% cuts below current levels

The Copenhagen Conference805

Copenhagen: The Long Story

Nine rounds of global negotiationstook place between Baliand Copenhagen.

Between December 2007 and December 2009, AWG-LCA and AWG-KP held ses-

sions in Bonn, Accra, Poznan, Bangkok, and Barcelona. These two years brought

little progress in key policy debates and much of the exchange consisted of countries

reiterating well-known positions and wrangling on procedural issues. In the three

months before Copenhagen,however,an avalanche of positive developments

occurred. Following European leadership,Japan pledged highly ambitious25

percentemission cuts below 1990 levels by 2020 while US Congress considered

legislation for 30 percent below 2005 by 2025 and 42 percent by 2030. The global

media reported quantitative policy pledges by major developing country emitters:

first Brazil with 36–39 percent cuts by 2020 below business-as-usual,followed by

China with 40–45 percent and India with 20–25 percent decline in carbon intensity