BUS284: International Corporate Governance Chapter 1 Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2021/10/01

|24

|12602

|70

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This document is an analysis of Chapter 1 from the book "International corporate governance (2012)" by Marc Goergen, focusing on defining corporate governance and introducing key theoretical models. It explores various definitions of corporate governance, highlighting the main objective of a corporation and how corporate governance problems change with ownership and control concentration. The analysis covers the principal-agent model, agency problems of equity and debt, and corporate governance issues in countries with concentrated ownership. The document contrasts different definitions of corporate governance, including those emphasizing shareholder value maximization and those considering stakeholder interests. It also discusses the roles of the board of directors, the differences between Anglo-American and Continental European approaches, and the evolution of corporate governance practices. The document concludes by presenting a more neutral definition of corporate governance, which addresses conflicts of interest between finance providers and managers, shareholders and stakeholders, and different types of shareholders. The Cadbury Report's definition of corporate governance is also discussed.

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of

Murdoch University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1968 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further

reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright

protection under the Act.

Do not remove this notice

Course of Study:

(BUS284) Comparative Corporate Governance and International Operations

Title of work:

International corporate governance (2012)

Section:

Chapter 1: Defining corporate governance and key theoretical models pp. 3--24

Author/editor of work:

Goergen, Marc

Author of section:

Marc Goergen

Name of Publisher:

Pearson

WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of

Murdoch University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1968 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further

reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright

protection under the Act.

Do not remove this notice

Course of Study:

(BUS284) Comparative Corporate Governance and International Operations

Title of work:

International corporate governance (2012)

Section:

Chapter 1: Defining corporate governance and key theoretical models pp. 3--24

Author/editor of work:

Goergen, Marc

Author of section:

Marc Goergen

Name of Publisher:

Pearson

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PART I

Introduction to Corporate Governance

Introduction to Corporate Governance

Defining corporate governance and key

theoretical models

- Chapter aims

This chapter aims to introduce you to the subject area of corporate governance. The

chapter discusses the various definitions of corporate governance, reviews the main

objective of the corporation and explains how corporate governance problems

change with ownership and control concentration. The chapter also introduces

the main theories underpinning corporate governance. While the book focuses on

stock-exchange listed corporations, this chapter also discusses alternative forms of

organisations such as mutual organisations and partnerships.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Contrast the different definitions of corporate governance

2 Critically review the principal-agent model

3 Discuss the agency problems of equity and debt

4 Explain the corporate governance problem that prevails in countries

where corporate ownership and control are concentrated

5 Distinguish between ownership and control

- Introduction

While this chapter will briefly review alternative forms of organisation and own

ership, the focus of this book is on stock-exchange listed firms. These firms are

typically in the form of stock corporations, i.e. they have equitystocks or shares

outstanding which trade on a recognised stock exchange. Stocks or shares are cer

tificates of ownership and they also frequently havecontrol rights, i.e. voting

rights which enable their holders, the shareholders, to vote at the annual gen

eral shareholders' meeting (AGM). One of the important rights that voting shares

confer to their holders is the right to appoint the members of theboard of direc

tors. The board of directors is the ultimate governing body within the corporation.

Its role, and in particular the role of the non-executive directors on the board, is

to look after the interests of all the shareholders as well as sometimes those of other

stakeholders such as the corporation's employees or banks.More precisely, the

non-executives' role is to monitor the firm's top management, including the execu

tive directors which are the other type of directors sitting on the firm's board.1

theoretical models

- Chapter aims

This chapter aims to introduce you to the subject area of corporate governance. The

chapter discusses the various definitions of corporate governance, reviews the main

objective of the corporation and explains how corporate governance problems

change with ownership and control concentration. The chapter also introduces

the main theories underpinning corporate governance. While the book focuses on

stock-exchange listed corporations, this chapter also discusses alternative forms of

organisations such as mutual organisations and partnerships.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Contrast the different definitions of corporate governance

2 Critically review the principal-agent model

3 Discuss the agency problems of equity and debt

4 Explain the corporate governance problem that prevails in countries

where corporate ownership and control are concentrated

5 Distinguish between ownership and control

- Introduction

While this chapter will briefly review alternative forms of organisation and own

ership, the focus of this book is on stock-exchange listed firms. These firms are

typically in the form of stock corporations, i.e. they have equitystocks or shares

outstanding which trade on a recognised stock exchange. Stocks or shares are cer

tificates of ownership and they also frequently havecontrol rights, i.e. voting

rights which enable their holders, the shareholders, to vote at the annual gen

eral shareholders' meeting (AGM). One of the important rights that voting shares

confer to their holders is the right to appoint the members of theboard of direc

tors. The board of directors is the ultimate governing body within the corporation.

Its role, and in particular the role of the non-executive directors on the board, is

to look after the interests of all the shareholders as well as sometimes those of other

stakeholders such as the corporation's employees or banks.More precisely, the

non-executives' role is to monitor the firm's top management, including the execu

tive directors which are the other type of directors sitting on the firm's board.1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

While in the US non-executives are referred to as (independent or outside) directors

and executives are referred to as officers, this book adopts the internationally used

terminology of non-executive and executive directors.

- Defining corporate governance

Most definitions of corporate governance are based on implicit, if not explicit,

assumptions about what should be the main objective of the corporation. However,

there is no universal agreement as to what the main objective of a corporation

should be and this objective is likely to depend on a country's culture and elec

toral system and its government's political orientation as well as the country's legal

system. Chapter 4 of Part II will shed more light on how these cultural, political

and institutional factors may explain differences in corporate governance and con

trol across countries.

Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny define corporate governance as:

'the ways in which suppliers of fi.nance to corporations assure themselves of getting a

return on their investment.'2

Basing themselves on Oliver Williamson's work,3 Shleifer and Vishny's defini

tion clearly assumes that the main objective of the corporation is to maximise the

returns to the shareholders (as well as the debtholders). They justify their focus

by the argument that the investments in the firm by the providers of finance are

typically sunk funds, i.e. funds that the latter are likely to lose if the corporation

runs into trouble. On the contrary,-the corporation's other stakeholders, such as

its employees, suppliers and customers, can easily walk away from the corpora

tion without losing their investments. For example, an employee should be able to

find a job in another firm which values her human capital. While the providers of

finance lose the capital they have invested in the corporation, the employee does

not lose her human capital if the firm fails. Hence, the providers of finance, and

in particular the shareholders, are the residual risk bearers or theresidual claim

a nts to the firm's assets. In other words, if the firm gets into financial distress, the

claims of all the stakeholders other than the shareholders will be met first before

the claims of the latter can be met. Typically when the firm is in financial distress,

the firm's assets are insufficient to meet all of the claims it is facing and the share

holders will lose their initial investment. In contrast, the other claimants will walk

away with all or at least some of their capital.

In contrast to Shleifer and Vishny, Sarah Worthington argues that there is noth

ing in the legal status of a shareholder that justifies the focus on shareholder value

maximisation.4 Paddy Ireland goes one step further, arguing that corporate assets

should no longer be considered to be the private property of the shareholders but

rather as common property given that they are 'the product of the collective labour

of many generations' (p. 56).5 Marc Goergen and Luc Renneboog suggest a defini

tion which allows for differences across firms in terms of the actors or stakeholders

whose interests the corporation focuses on. According to their definition,

'[a] corporate governance system is the combination of mechanisms which ensure that

the management (the agent) runs the fi.rm for the benefi.t of one or several stakehold

ers (principals). Such stakeholders may cover shareholders, creditors, suppliers, clients,

employees and other parties with whom the fi.rm conducts its business.'6

While in the US non-executives are referred to as (independent or outside) directors

and executives are referred to as officers, this book adopts the internationally used

terminology of non-executive and executive directors.

- Defining corporate governance

Most definitions of corporate governance are based on implicit, if not explicit,

assumptions about what should be the main objective of the corporation. However,

there is no universal agreement as to what the main objective of a corporation

should be and this objective is likely to depend on a country's culture and elec

toral system and its government's political orientation as well as the country's legal

system. Chapter 4 of Part II will shed more light on how these cultural, political

and institutional factors may explain differences in corporate governance and con

trol across countries.

Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny define corporate governance as:

'the ways in which suppliers of fi.nance to corporations assure themselves of getting a

return on their investment.'2

Basing themselves on Oliver Williamson's work,3 Shleifer and Vishny's defini

tion clearly assumes that the main objective of the corporation is to maximise the

returns to the shareholders (as well as the debtholders). They justify their focus

by the argument that the investments in the firm by the providers of finance are

typically sunk funds, i.e. funds that the latter are likely to lose if the corporation

runs into trouble. On the contrary,-the corporation's other stakeholders, such as

its employees, suppliers and customers, can easily walk away from the corpora

tion without losing their investments. For example, an employee should be able to

find a job in another firm which values her human capital. While the providers of

finance lose the capital they have invested in the corporation, the employee does

not lose her human capital if the firm fails. Hence, the providers of finance, and

in particular the shareholders, are the residual risk bearers or theresidual claim

a nts to the firm's assets. In other words, if the firm gets into financial distress, the

claims of all the stakeholders other than the shareholders will be met first before

the claims of the latter can be met. Typically when the firm is in financial distress,

the firm's assets are insufficient to meet all of the claims it is facing and the share

holders will lose their initial investment. In contrast, the other claimants will walk

away with all or at least some of their capital.

In contrast to Shleifer and Vishny, Sarah Worthington argues that there is noth

ing in the legal status of a shareholder that justifies the focus on shareholder value

maximisation.4 Paddy Ireland goes one step further, arguing that corporate assets

should no longer be considered to be the private property of the shareholders but

rather as common property given that they are 'the product of the collective labour

of many generations' (p. 56).5 Marc Goergen and Luc Renneboog suggest a defini

tion which allows for differences across firms in terms of the actors or stakeholders

whose interests the corporation focuses on. According to their definition,

'[a] corporate governance system is the combination of mechanisms which ensure that

the management (the agent) runs the fi.rm for the benefi.t of one or several stakehold

ers (principals). Such stakeholders may cover shareholders, creditors, suppliers, clients,

employees and other parties with whom the fi.rm conducts its business.'6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

-

1.2 DEFINING CORPORORATE GOVERNANCE 5

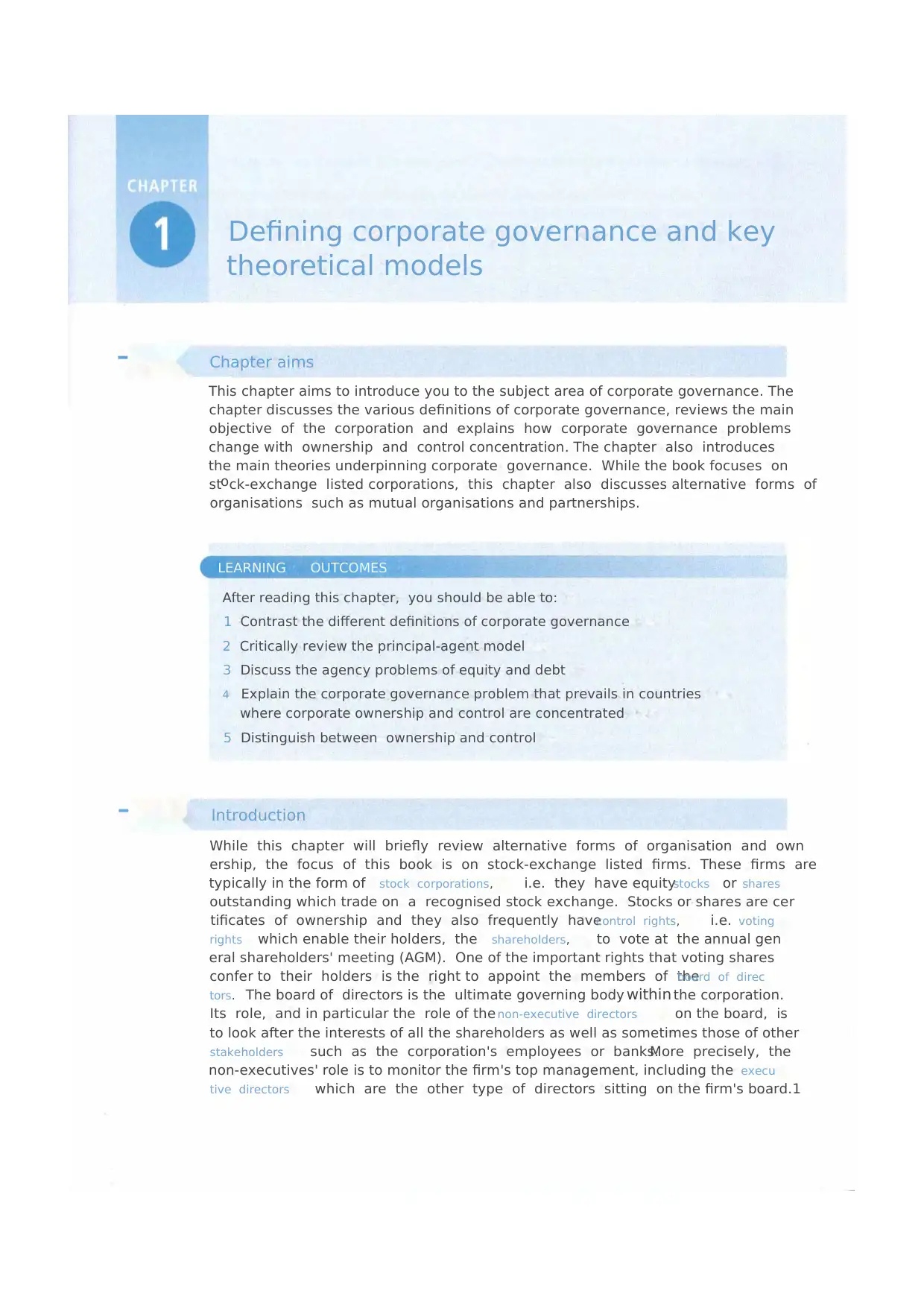

While Shleifer and Vishny's definition largely reflects the focus of the typi

cal American or British stock-exchange listed corporation, managers of most

Continental European firms also tend to take into account the interests of the

corporation's other stakeholders when running the firm. Although this statement

dates back more than 40 years and may now appear somewhat stereotypical, it nev

ertheless is a good illustration of what is frequently still managers' attitude outside

the Anglo-American world. The chief executive officer (CEO) of the German car

maker Volkswagen AG stated the following.

'Why should I care about the shareholders, who I see once a year at the general meet

ing. It is much more important that I care about the employees; I see them every day.17

Further, in Germany corporate law explicitly includes other stakeholder interests in

the firm's objective function. Indeed, the German Co-determination Law of 1976

requires firms with more than 2,000 workers to have 50% of employee representa

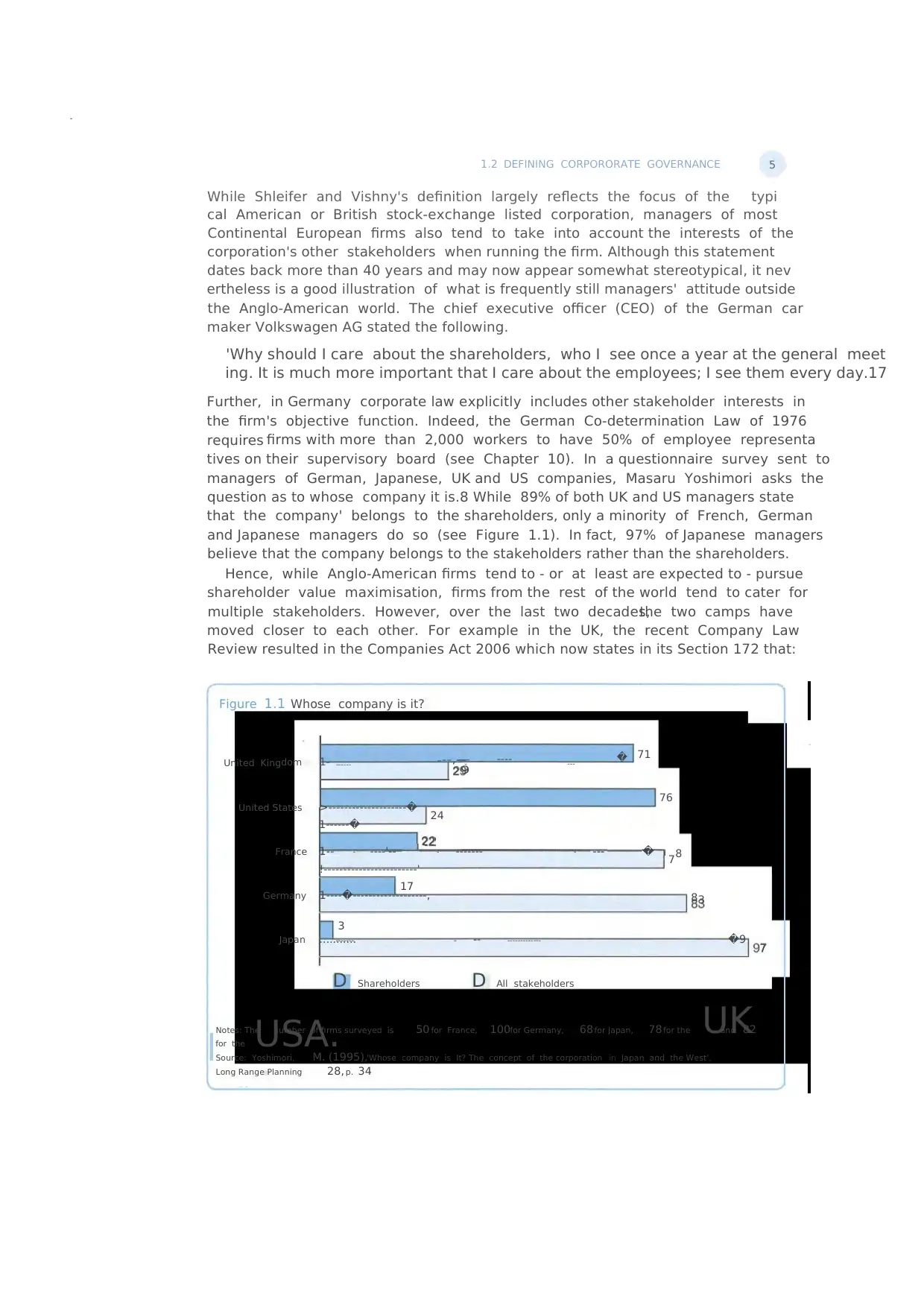

tives on their supervisory board (see Chapter 10). In a questionnaire survey sent to

managers of German, Japanese, UK and US companies, Masaru Yoshimori asks the

question as to whose company it is.8 While 89% of both UK and US managers state

that the company' belongs to the shareholders, only a minority of French, German

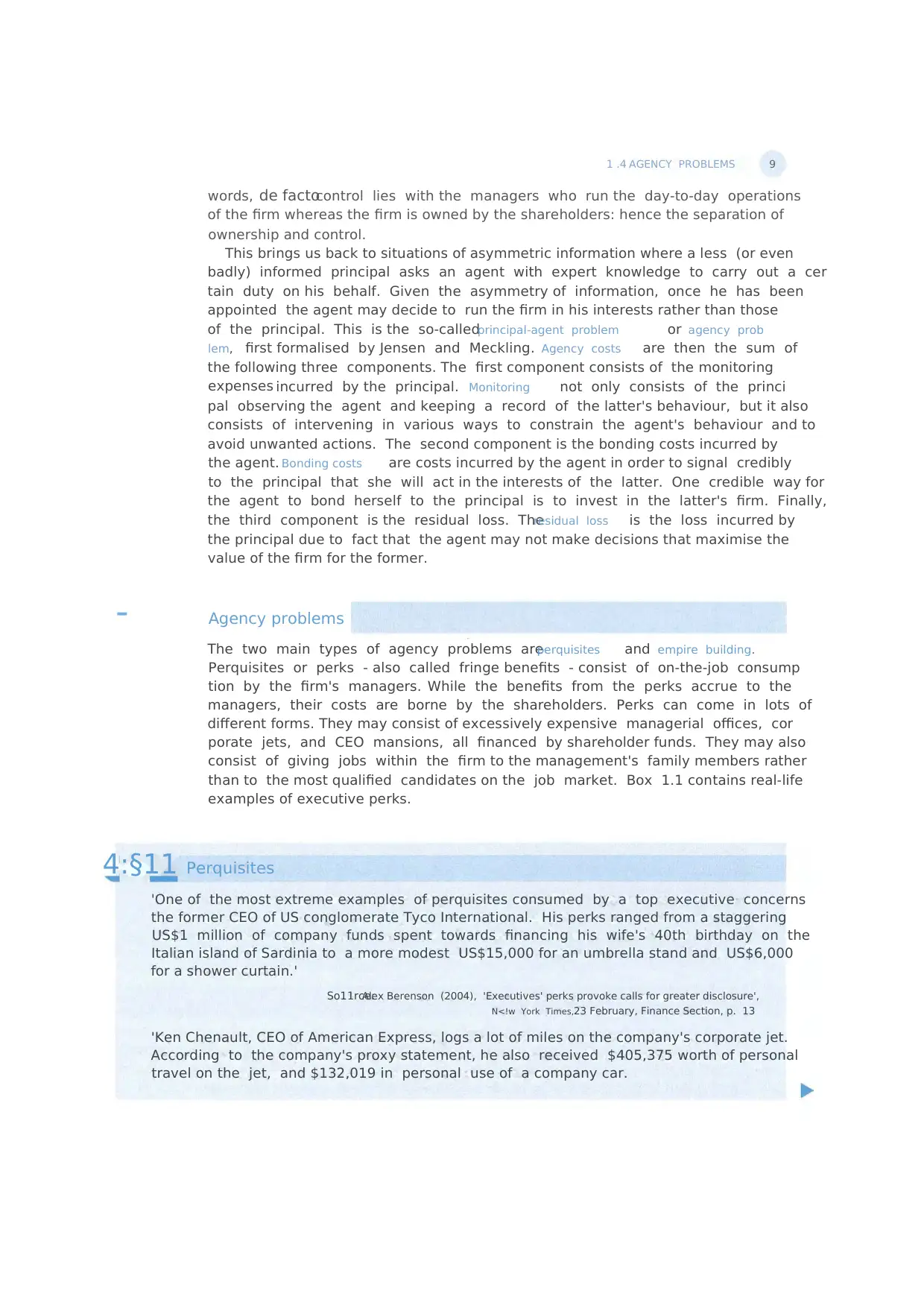

and Japanese managers do so (see Figure 1.1). In fact, 97% of Japanese managers

believe that the company belongs to the stakeholders rather than the shareholders.

Hence, while Anglo-American firms tend to - or at least are expected to - pursue

shareholder value maximisation, firms from the rest of the world tend to cater for

multiple stakeholders. However, over the last two decades,the two camps have

moved closer to each other. For example in the UK, the recent Company Law

Review resulted in the Companies Act 2006 which now states in its Section 172 that:

Figure 1.1 Whose company is it?

71

United Kingdom

1-

------

---,--

2

-

9

-

-

---- ---

�

76

United States >--------------------� 24

1------�

22

France 1-- - ----'-- - ------- - --- � 78

!------------------------'

17

Germany 1----�-------------------, 83

3

Japan ...........------- - -- ------------- �9 7

D Shareholders D All stakeholders

Notes: The number of firms surveyed is 50 for France, 100for Germany, 68 for Japan, 78 for the UKand 82

for the USA.lSource: Yoshimori, M. (1995),'Whose company is It? The concept of the corporation in Japan and the West',

Long Range Planning 28, p. 34

-- -

1.2 DEFINING CORPORORATE GOVERNANCE 5

While Shleifer and Vishny's definition largely reflects the focus of the typi

cal American or British stock-exchange listed corporation, managers of most

Continental European firms also tend to take into account the interests of the

corporation's other stakeholders when running the firm. Although this statement

dates back more than 40 years and may now appear somewhat stereotypical, it nev

ertheless is a good illustration of what is frequently still managers' attitude outside

the Anglo-American world. The chief executive officer (CEO) of the German car

maker Volkswagen AG stated the following.

'Why should I care about the shareholders, who I see once a year at the general meet

ing. It is much more important that I care about the employees; I see them every day.17

Further, in Germany corporate law explicitly includes other stakeholder interests in

the firm's objective function. Indeed, the German Co-determination Law of 1976

requires firms with more than 2,000 workers to have 50% of employee representa

tives on their supervisory board (see Chapter 10). In a questionnaire survey sent to

managers of German, Japanese, UK and US companies, Masaru Yoshimori asks the

question as to whose company it is.8 While 89% of both UK and US managers state

that the company' belongs to the shareholders, only a minority of French, German

and Japanese managers do so (see Figure 1.1). In fact, 97% of Japanese managers

believe that the company belongs to the stakeholders rather than the shareholders.

Hence, while Anglo-American firms tend to - or at least are expected to - pursue

shareholder value maximisation, firms from the rest of the world tend to cater for

multiple stakeholders. However, over the last two decades,the two camps have

moved closer to each other. For example in the UK, the recent Company Law

Review resulted in the Companies Act 2006 which now states in its Section 172 that:

Figure 1.1 Whose company is it?

71

United Kingdom

1-

------

---,--

2

-

9

-

-

---- ---

�

76

United States >--------------------� 24

1------�

22

France 1-- - ----'-- - ------- - --- � 78

!------------------------'

17

Germany 1----�-------------------, 83

3

Japan ...........------- - -- ------------- �9 7

D Shareholders D All stakeholders

Notes: The number of firms surveyed is 50 for France, 100for Germany, 68 for Japan, 78 for the UKand 82

for the USA.lSource: Yoshimori, M. (1995),'Whose company is It? The concept of the corporation in Japan and the West',

Long Range Planning 28, p. 34

-- -

6 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

'Directors should also recognise, as the circumstances require, the company's need t

fosterrelationships with its employees, customers and suppliers, its need to maintain its

businessreputation, and its need to consider the company's impact on the community

and the working environment.'

Nevertheless, company directors must actbona "fidein accordance to what would

most likely promote the success of the company for the benefit of the collective

body of shareholders. In other words, while directors are expected to take into

account the interests of other stakeholders, they should only do so if this is in the

long-term interest of the company, and ultimately its shareholders, i.e. its owners.

Hence, the principle of shareholder primacy is still pretty much intact in the

UK and also the USA. At the same time, Continental Europe has moved closer to

the shareholder-oriented system of corporate governance. In particular, European

Union (EU) law has moved the law of its 27 member states closer to UK law. An

example is the 2004 EU Takeovers Directive which was largely modelled on the

UK City Code on Mergers and Takeovers (see Chapter 7 for details). In turn, recent

pressure on (large) corporations to behave socially responsibly has moved stake

holder considerations to the forefront.

A more neutral and less politically charged definition of corporate governance is

that the latter deals with conflicts of interests between

• the providers of finance and the managers;

• the shareholders and the stakeholders;

• different types of shareholders (mainly the large shareholder and the minority

shareholders);

and the prevention or mitigation of these conflicts of interests. This is the defini

tion which is adopted in this book. Another important advantage of this definition

is that it can be applied to a variety of corporate governance systems. More pre

cisely, this definition does not assume that problems of corporate governance are

limited to the failure of the management to look after the interests of the firm's

shareholders, but it also covers other possible corporate governance problems·

which are more likely to emerge in countries where corporations are characterised

by concentrated ownership and control. These corporate governance problems nor

mally consist of conflicts of interests between the firm's large shareholder and its

minority shareholders.

One of the first codes of best practice on corporate governance, if not even the

very first one, was theCadbury Report which was issued in 1992 in the United

Kingdom.9 The Cadbury Report defines corporate governance as 'the system by

which companies are directed and controlled'. However, in the following sentences

the Report then goes on to mention what it considers to be the crucial role of

boards of directors in corporate governance:

'Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. The share

holders' role in governance is to appoint the directors and the auditors and to satisty

themselves that an appropriate governance structure is in place. The responsibilities of

the board include setting the company's strategic aims, providing the leadership to put

them into effect, supervising the management of the business and reporting to share

holders on their stewardship. The board's actions are subject to laws, regulations and

the shareholders in general meeting.'

'Directors should also recognise, as the circumstances require, the company's need t

fosterrelationships with its employees, customers and suppliers, its need to maintain its

businessreputation, and its need to consider the company's impact on the community

and the working environment.'

Nevertheless, company directors must actbona "fidein accordance to what would

most likely promote the success of the company for the benefit of the collective

body of shareholders. In other words, while directors are expected to take into

account the interests of other stakeholders, they should only do so if this is in the

long-term interest of the company, and ultimately its shareholders, i.e. its owners.

Hence, the principle of shareholder primacy is still pretty much intact in the

UK and also the USA. At the same time, Continental Europe has moved closer to

the shareholder-oriented system of corporate governance. In particular, European

Union (EU) law has moved the law of its 27 member states closer to UK law. An

example is the 2004 EU Takeovers Directive which was largely modelled on the

UK City Code on Mergers and Takeovers (see Chapter 7 for details). In turn, recent

pressure on (large) corporations to behave socially responsibly has moved stake

holder considerations to the forefront.

A more neutral and less politically charged definition of corporate governance is

that the latter deals with conflicts of interests between

• the providers of finance and the managers;

• the shareholders and the stakeholders;

• different types of shareholders (mainly the large shareholder and the minority

shareholders);

and the prevention or mitigation of these conflicts of interests. This is the defini

tion which is adopted in this book. Another important advantage of this definition

is that it can be applied to a variety of corporate governance systems. More pre

cisely, this definition does not assume that problems of corporate governance are

limited to the failure of the management to look after the interests of the firm's

shareholders, but it also covers other possible corporate governance problems·

which are more likely to emerge in countries where corporations are characterised

by concentrated ownership and control. These corporate governance problems nor

mally consist of conflicts of interests between the firm's large shareholder and its

minority shareholders.

One of the first codes of best practice on corporate governance, if not even the

very first one, was theCadbury Report which was issued in 1992 in the United

Kingdom.9 The Cadbury Report defines corporate governance as 'the system by

which companies are directed and controlled'. However, in the following sentences

the Report then goes on to mention what it considers to be the crucial role of

boards of directors in corporate governance:

'Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. The share

holders' role in governance is to appoint the directors and the auditors and to satisty

themselves that an appropriate governance structure is in place. The responsibilities of

the board include setting the company's strategic aims, providing the leadership to put

them into effect, supervising the management of the business and reporting to share

holders on their stewardship. The board's actions are subject to laws, regulations and

the shareholders in general meeting.'

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1.3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE T H EORY 7

As a result, this definition is less general than the one adopted in this book for at

least two reasons. First, it is built on the premise that boards of directors have a

crucial role in corporate governance. In Chapter 5 of this book, we shall see that

there is as yet very little empirical evidence that boards of directors are an effective

corporate governance mechanism. Second, the Cadbury definition also implicitly

assumes that individual shareholders are not powerful enough to take actions when

their company's management performs badly. In Chapter 2, we shall see that this

is typically not the case in stock-exchange listed corporations outside the UK and

the USA as these corporations tend to have large shareholders that have sufficient

voting power to fire inefficient management.

- Corporate governance theory

Corporate governance issues are not new. They date back to at least the 18th cen

tury when large stock corporations were emerging. In his treatise published in

1 7 76, the Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote the following.10

'It is in the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can; and if his

emoluments are to be precisely the same, whether he does, or does not perform some

laborious duty, it is certainly his interest, at least as interest is vulgarly understood,

either to neglect it altogether, or, if he is subject to some authority which will not suffer

him to do this, to perform it in as careless and slovenly a manner as that authority

will permit.'

This statement clearly illustrates the conflicts of interests that may exist between

a so-calledagent and the agent's principal. These conflicts of interests were later

formalised by Michael Jensen and William Meckling in their principal-agent

theory or model which was introduced in their seminal 1976 paper.11 While the

agent has been asked by the principal to carry out a specific duty, the agent may

not act in the best interest of the principal once the contract between the two par

ties has been signed and may prefer to pursue his own interests. This type of danger

is what economists normally refer to as moral hazard. Moral hazard consists of the

fact that once a contract has been signed it may be in the interests of the agent to

behave badly or at least less responsibly, i.e. in ways that may harm the principal

while clearly serving the interests of the agent. Cases of moral hazard are not just

limited to corporate governance. Indeed, they are also a major issue for insurance

companies. For example, as soon as you have taken out an insurance policy cover

ing yourself against burglary you may change your behaviour and be less careful

about locking the front door of your house in the mornings when you leave for

college or work. Rather than walking back home if you happen to be unsure about

whether you have locked the door as you would have done in the past, you may

decide not to do so as you are now covered against burglary by the insurance com

pany. If your front door happens to be unlocked and you get burgled, the cost will

be (at least partially) borne by the insurance company. If you walk back home you

will be late for college or work.Hence, you may just decide to act in your own

interests, i.e. save yourself the bother to go all the way back home, rather than act

as a responsible policyholder.

A potential way to mitigate or even avoid principal-agent problems is so-called

complete contracts. Complete contracts are contracts which specify exactly what

As a result, this definition is less general than the one adopted in this book for at

least two reasons. First, it is built on the premise that boards of directors have a

crucial role in corporate governance. In Chapter 5 of this book, we shall see that

there is as yet very little empirical evidence that boards of directors are an effective

corporate governance mechanism. Second, the Cadbury definition also implicitly

assumes that individual shareholders are not powerful enough to take actions when

their company's management performs badly. In Chapter 2, we shall see that this

is typically not the case in stock-exchange listed corporations outside the UK and

the USA as these corporations tend to have large shareholders that have sufficient

voting power to fire inefficient management.

- Corporate governance theory

Corporate governance issues are not new. They date back to at least the 18th cen

tury when large stock corporations were emerging. In his treatise published in

1 7 76, the Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote the following.10

'It is in the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can; and if his

emoluments are to be precisely the same, whether he does, or does not perform some

laborious duty, it is certainly his interest, at least as interest is vulgarly understood,

either to neglect it altogether, or, if he is subject to some authority which will not suffer

him to do this, to perform it in as careless and slovenly a manner as that authority

will permit.'

This statement clearly illustrates the conflicts of interests that may exist between

a so-calledagent and the agent's principal. These conflicts of interests were later

formalised by Michael Jensen and William Meckling in their principal-agent

theory or model which was introduced in their seminal 1976 paper.11 While the

agent has been asked by the principal to carry out a specific duty, the agent may

not act in the best interest of the principal once the contract between the two par

ties has been signed and may prefer to pursue his own interests. This type of danger

is what economists normally refer to as moral hazard. Moral hazard consists of the

fact that once a contract has been signed it may be in the interests of the agent to

behave badly or at least less responsibly, i.e. in ways that may harm the principal

while clearly serving the interests of the agent. Cases of moral hazard are not just

limited to corporate governance. Indeed, they are also a major issue for insurance

companies. For example, as soon as you have taken out an insurance policy cover

ing yourself against burglary you may change your behaviour and be less careful

about locking the front door of your house in the mornings when you leave for

college or work. Rather than walking back home if you happen to be unsure about

whether you have locked the door as you would have done in the past, you may

decide not to do so as you are now covered against burglary by the insurance com

pany. If your front door happens to be unlocked and you get burgled, the cost will

be (at least partially) borne by the insurance company. If you walk back home you

will be late for college or work.Hence, you may just decide to act in your own

interests, i.e. save yourself the bother to go all the way back home, rather than act

as a responsible policyholder.

A potential way to mitigate or even avoid principal-agent problems is so-called

complete contracts. Complete contracts are contracts which specify exactly what

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY T HEORETICAL MODELS

• the managers must do in each future contingency of the world; and

• what the distribution of profits will be in each contingency.

As first pointed out by Oliver Williamson, 12 in practice however, contracts are

unlikely to be complete as

• it is impossible to predict all future contingencies of the world;

• such contracts would be too complex to write; and

• they would be difficult or even impossible to monitor and reinforce by outsiders

such as a court of Iaw.13

A necessary condition for moral hazard to exist and for complete contracts to be an

impossibility is the existence of asymmetric information. Asymmetric informa

tion refers to situations where one party, typically the one that agrees to carry out

a certain duty or agrees to behave in a certain way, i.e. the agent, has more infor

mation than the other party, the principal. If both the agent and the principal had

access to the same information at all times, there would be no moral hazard issue.

In other words, moral hazard exists because the principal cannot keep track of the

agent's actions at all times. Evenex post,it can sometimes be difficult for a principal

to judge whether failure is due to the agent or due to circumstances that were out

of the control of the agent.

Returning to Jensen and Meckling's principal-agent model, apart from the

existence of asymmetric information the model also assumes that there is a sep

aration of ownership and control in the corporation. Adolf Berle and Gardiner

Means were the first to outline this separation of ownership and control in their

1932 book The Modern Corporation and Private Property.14They argue that at first a

firm starts off as a small business which is fully owned by its founder, typically an

entrepreneur. At this stage, there are no conflicts of interests within the firm as the

entrepreneur both owns and runs the firms. Hence, if the entrepreneur decides to

work harder, all of the additional revenue generated by this increased effort will go

into his own pockets. This implies that the entrepreneur has the perfect incentives

to work hard: all of the additional revenue generated by working harder will always

accrue to him.

As the firm grows, it becomes more and more difficult for the entrepreneur to

provide all the capital needed. At one point the entrepreneur will need to take the

firm to the stock market so that the latter can tap into external capital. Once the

firm has raised external capital, the entrepreneur's incentives have significantly

altered. As the entrepreneur no longer owns all of the firm's capital, he may now

be less inclined to work hard. In other words, if the entrepreneur works harder

some .of the fruits from his efforts will go to the firm's new shareholders. As the

firm becomes larger and larger, the separation of ownership and control is likely

to become more pronounced. Once the entrepreneur has sold all of his remaining

shares, there will come the point where the firm will be run by professional manag

ers who own none or very little of the firm's capital. These managers are the agents,

who are expected to run the firm on the behalf of the principals, the firm's owners

or shareholders. Hence, there is a clear 'division of labour' in the modern corpora

tion. On the one hand, the managers have the expertise to run the firm, but lack

the required funds to finance its operations. On the other hand, the shareholders

have the required funds, but typically are not qualified to run the firm. In other

• the managers must do in each future contingency of the world; and

• what the distribution of profits will be in each contingency.

As first pointed out by Oliver Williamson, 12 in practice however, contracts are

unlikely to be complete as

• it is impossible to predict all future contingencies of the world;

• such contracts would be too complex to write; and

• they would be difficult or even impossible to monitor and reinforce by outsiders

such as a court of Iaw.13

A necessary condition for moral hazard to exist and for complete contracts to be an

impossibility is the existence of asymmetric information. Asymmetric informa

tion refers to situations where one party, typically the one that agrees to carry out

a certain duty or agrees to behave in a certain way, i.e. the agent, has more infor

mation than the other party, the principal. If both the agent and the principal had

access to the same information at all times, there would be no moral hazard issue.

In other words, moral hazard exists because the principal cannot keep track of the

agent's actions at all times. Evenex post,it can sometimes be difficult for a principal

to judge whether failure is due to the agent or due to circumstances that were out

of the control of the agent.

Returning to Jensen and Meckling's principal-agent model, apart from the

existence of asymmetric information the model also assumes that there is a sep

aration of ownership and control in the corporation. Adolf Berle and Gardiner

Means were the first to outline this separation of ownership and control in their

1932 book The Modern Corporation and Private Property.14They argue that at first a

firm starts off as a small business which is fully owned by its founder, typically an

entrepreneur. At this stage, there are no conflicts of interests within the firm as the

entrepreneur both owns and runs the firms. Hence, if the entrepreneur decides to

work harder, all of the additional revenue generated by this increased effort will go

into his own pockets. This implies that the entrepreneur has the perfect incentives

to work hard: all of the additional revenue generated by working harder will always

accrue to him.

As the firm grows, it becomes more and more difficult for the entrepreneur to

provide all the capital needed. At one point the entrepreneur will need to take the

firm to the stock market so that the latter can tap into external capital. Once the

firm has raised external capital, the entrepreneur's incentives have significantly

altered. As the entrepreneur no longer owns all of the firm's capital, he may now

be less inclined to work hard. In other words, if the entrepreneur works harder

some .of the fruits from his efforts will go to the firm's new shareholders. As the

firm becomes larger and larger, the separation of ownership and control is likely

to become more pronounced. Once the entrepreneur has sold all of his remaining

shares, there will come the point where the firm will be run by professional manag

ers who own none or very little of the firm's capital. These managers are the agents,

who are expected to run the firm on the behalf of the principals, the firm's owners

or shareholders. Hence, there is a clear 'division of labour' in the modern corpora

tion. On the one hand, the managers have the expertise to run the firm, but lack

the required funds to finance its operations. On the other hand, the shareholders

have the required funds, but typically are not qualified to run the firm. In other

1 .4 AGENCY PROBLEMS 9

words, de factocontrol lies with the managers who run the day-to-day operations

of the firm whereas the firm is owned by the shareholders: hence the separation of

ownership and control.

This brings us back to situations of asymmetric information where a less (or even

badly) informed principal asks an agent with expert knowledge to carry out a cer

tain duty on his behalf. Given the asymmetry of information, once he has been

appointed the agent may decide to run the firm in his interests rather than those

of the principal. This is the so-calledprincipal-agent problem or agency prob

lem, first formalised by Jensen and Meckling. Agency costs are then the sum of

the following three components. The first component consists of the monitoring

expenses incurred by the principal. Monitoring not only consists of the princi

pal observing the agent and keeping a record of the latter's behaviour, but it also

consists of intervening in various ways to constrain the agent's behaviour and to

avoid unwanted actions. The second component is the bonding costs incurred by

the agent. Bonding costs are costs incurred by the agent in order to signal credibly

to the principal that she will act in the interests of the latter. One credible way for

the agent to bond herself to the principal is to invest in the latter's firm. Finally,

the third component is the residual loss. Theresidual loss is the loss incurred by

the principal due to fact that the agent may not make decisions that maximise the

value of the firm for the former.

- Agency problems

The two main types of agency problems areperquisites and empire building.

Perquisites or perks - also called fringe benefits - consist of on-the-job consump

tion by the firm's managers. While the benefits from the perks accrue to the

managers, their costs are borne by the shareholders. Perks can come in lots of

different forms. They may consist of excessively expensive managerial offices, cor

porate jets, and CEO mansions, all financed by shareholder funds. They may also

consist of giving jobs within the firm to the management's family members rather

than to the most qualified candidates on the job market. Box 1.1 contains real-life

examples of executive perks.

4:§11 Perquisites

'One of the most extreme examples of perquisites consumed by a top executive concerns

the former CEO of US conglomerate Tyco International. His perks ranged from a staggering

US$1 million of company funds spent towards financing his wife's 40th birthday on the

Italian island of Sardinia to a more modest US$15,000 for an umbrella stand and US$6,000

for a shower curtain.'

So11rce:Alex Berenson (2004), 'Executives' perks provoke calls for greater disclosure',

N<!w York Times,23 February, Finance Section, p. 13

'Ken Chenault, CEO of American Express, logs a lot of miles on the company's corporate jet.

According to the company's proxy statement, he also received $405,375 worth of personal

travel on the jet, and $132,019 in personal use of a company car.

words, de factocontrol lies with the managers who run the day-to-day operations

of the firm whereas the firm is owned by the shareholders: hence the separation of

ownership and control.

This brings us back to situations of asymmetric information where a less (or even

badly) informed principal asks an agent with expert knowledge to carry out a cer

tain duty on his behalf. Given the asymmetry of information, once he has been

appointed the agent may decide to run the firm in his interests rather than those

of the principal. This is the so-calledprincipal-agent problem or agency prob

lem, first formalised by Jensen and Meckling. Agency costs are then the sum of

the following three components. The first component consists of the monitoring

expenses incurred by the principal. Monitoring not only consists of the princi

pal observing the agent and keeping a record of the latter's behaviour, but it also

consists of intervening in various ways to constrain the agent's behaviour and to

avoid unwanted actions. The second component is the bonding costs incurred by

the agent. Bonding costs are costs incurred by the agent in order to signal credibly

to the principal that she will act in the interests of the latter. One credible way for

the agent to bond herself to the principal is to invest in the latter's firm. Finally,

the third component is the residual loss. Theresidual loss is the loss incurred by

the principal due to fact that the agent may not make decisions that maximise the

value of the firm for the former.

- Agency problems

The two main types of agency problems areperquisites and empire building.

Perquisites or perks - also called fringe benefits - consist of on-the-job consump

tion by the firm's managers. While the benefits from the perks accrue to the

managers, their costs are borne by the shareholders. Perks can come in lots of

different forms. They may consist of excessively expensive managerial offices, cor

porate jets, and CEO mansions, all financed by shareholder funds. They may also

consist of giving jobs within the firm to the management's family members rather

than to the most qualified candidates on the job market. Box 1.1 contains real-life

examples of executive perks.

4:§11 Perquisites

'One of the most extreme examples of perquisites consumed by a top executive concerns

the former CEO of US conglomerate Tyco International. His perks ranged from a staggering

US$1 million of company funds spent towards financing his wife's 40th birthday on the

Italian island of Sardinia to a more modest US$15,000 for an umbrella stand and US$6,000

for a shower curtain.'

So11rce:Alex Berenson (2004), 'Executives' perks provoke calls for greater disclosure',

N<!w York Times,23 February, Finance Section, p. 13

'Ken Chenault, CEO of American Express, logs a lot of miles on the company's corporate jet.

According to the company's proxy statement, he also received $405,375 worth of personal

travel on the jet, and $132,019 in personal use of a company car.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

Occidental's Irani got $562,589 worth of security services from the company. Also, in a

year when he took home $415 million, Irani racked up a bill of $556,470 for tax preparation

and financial-planning services, paid for by the company.

[ ...]

At Qwest, CEO Richard Notebaert got $332,000 for personal use of the corporate jet,

$62,000 for financial and tax-consulting services, and $56,000 fora personal assistant

and office expenses. Because those perks generated a tax liability for him, Qwest paid him

another $197,000 to cover those taxes.'

Source: Greg Farrell and Barbara Hansen (2007), 'A peek at the perks of the corner office',

USA Todny, 16 April, Money Section, p. lB

'The chairman of Starbucks Corporation, whose salary exceeded US$100 million, received a

total of US$ l.23 million in perks in 2006, which included security, life insurance and per

sonal use of a corporate jet. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com had his company spend

a total of US$1.1 million on security while his annual salary was a modest US$81,840.'

Source: Craig Harris and Andrea James (2007), 'Top execs rake in the perks. Region's biggest companies shell out for

jet use, security', Seattle Post- Intelligencer, 26 February, News Section, p. Al

'Angela Ahrendts, chief executive of fashion group Burberry [ ...], has received cash, benefits

and shares worth pounds 6. lm. Payouts included pounds 432,000 of perks including car and

clothing allowances.'

Source: Simon Bowers and Julia Finch (2010), 'The Guardian: Blue-chip companies braced for the great

boardroom pay rebellion: Shareholders likely to revolt at four meetings Targets of investor anger

include M&S and Burberry', G11ardian, 12 July, no page number stated

'Former Merrill CEO John Thain spent $1.2 million to renovate his offices, including instal

lation of a $35,000 toilet.

In January [2009], troubled Citigroup - the recipient of a [US] $45-billion U.S. government

bailout - cancelled its order for a 12-seat, $50-million corporate jet after bad publicity over the

purchase. [ ... ] Wells Fargo& Co. cancelled a 12-night retreat for staff at two pricey Las Vegas

resorts. The bank [in 2008] received $25 billion from the Troubled Assets Relief Program.'

So11rce:Sheldon Alberts (2009), 'Obama scolds Wall St. titans for taking lavish bonuses',

The Gazette (Montreal), 5 February, Business Section, p. Bl

'Andy Haste, chief executive of insurance giant RSA, today added to the growing election

furore over bosses' pay as he received an inflation-busting 14% rise to GBP2.33 million for

2009. RSA profits fell 27% to GBPS44 million last year. [ ...] RSA pointed out that while Haste

received a 5% rise in his basic salary to GBP955,000 last year he - and the other executive

directors - would get no basic increase this year. However, he received a GBPl.02 million

bonus last year and perks including pension contributions of GBP309,000 and car and travel

benefits worth GBP42,000.'

Source: Nick Goodway (2010), 'Outrage at RSA chief Haste's pay package',

Evening Standard, 12 April, no page number stated

While perquisites can cause public outrage as Box 1.1 illustrates, especially when

they are combined with lacklustre performance or, even worse, corporate failure,

the amount of shareholder funds they typically consume is, however, relatively

modest compared to the other main type of agency problems which is empire

building. Nevertheless, research by David Yermack suggests that when CEO perks

Occidental's Irani got $562,589 worth of security services from the company. Also, in a

year when he took home $415 million, Irani racked up a bill of $556,470 for tax preparation

and financial-planning services, paid for by the company.

[ ...]

At Qwest, CEO Richard Notebaert got $332,000 for personal use of the corporate jet,

$62,000 for financial and tax-consulting services, and $56,000 fora personal assistant

and office expenses. Because those perks generated a tax liability for him, Qwest paid him

another $197,000 to cover those taxes.'

Source: Greg Farrell and Barbara Hansen (2007), 'A peek at the perks of the corner office',

USA Todny, 16 April, Money Section, p. lB

'The chairman of Starbucks Corporation, whose salary exceeded US$100 million, received a

total of US$ l.23 million in perks in 2006, which included security, life insurance and per

sonal use of a corporate jet. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com had his company spend

a total of US$1.1 million on security while his annual salary was a modest US$81,840.'

Source: Craig Harris and Andrea James (2007), 'Top execs rake in the perks. Region's biggest companies shell out for

jet use, security', Seattle Post- Intelligencer, 26 February, News Section, p. Al

'Angela Ahrendts, chief executive of fashion group Burberry [ ...], has received cash, benefits

and shares worth pounds 6. lm. Payouts included pounds 432,000 of perks including car and

clothing allowances.'

Source: Simon Bowers and Julia Finch (2010), 'The Guardian: Blue-chip companies braced for the great

boardroom pay rebellion: Shareholders likely to revolt at four meetings Targets of investor anger

include M&S and Burberry', G11ardian, 12 July, no page number stated

'Former Merrill CEO John Thain spent $1.2 million to renovate his offices, including instal

lation of a $35,000 toilet.

In January [2009], troubled Citigroup - the recipient of a [US] $45-billion U.S. government

bailout - cancelled its order for a 12-seat, $50-million corporate jet after bad publicity over the

purchase. [ ... ] Wells Fargo& Co. cancelled a 12-night retreat for staff at two pricey Las Vegas

resorts. The bank [in 2008] received $25 billion from the Troubled Assets Relief Program.'

So11rce:Sheldon Alberts (2009), 'Obama scolds Wall St. titans for taking lavish bonuses',

The Gazette (Montreal), 5 February, Business Section, p. Bl

'Andy Haste, chief executive of insurance giant RSA, today added to the growing election

furore over bosses' pay as he received an inflation-busting 14% rise to GBP2.33 million for

2009. RSA profits fell 27% to GBPS44 million last year. [ ...] RSA pointed out that while Haste

received a 5% rise in his basic salary to GBP955,000 last year he - and the other executive

directors - would get no basic increase this year. However, he received a GBPl.02 million

bonus last year and perks including pension contributions of GBP309,000 and car and travel

benefits worth GBP42,000.'

Source: Nick Goodway (2010), 'Outrage at RSA chief Haste's pay package',

Evening Standard, 12 April, no page number stated

While perquisites can cause public outrage as Box 1.1 illustrates, especially when

they are combined with lacklustre performance or, even worse, corporate failure,

the amount of shareholder funds they typically consume is, however, relatively

modest compared to the other main type of agency problems which is empire

building. Nevertheless, research by David Yermack suggests that when CEO perks

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

---

1 .5 T H E AGENCY PROBLEMS OF D EBT AND EQUITY 1 1

are first disclosed the stock price decreases by roughly 1 %.15 Over the long run,

firms that allow their CEO to use their jets for personal use underperform by 4%

which is significantly more than the cost of the corporate resources the CEO con

sumes. Yermack justifies this decline in the stock price by the fact that perks are

typically disclosed beforebad news is disclosed to the shareholders. Yermack con

cludes that CEOs postpone the disclosure of bad news until they have secured the

perks. Funnily enough, Yermack finds a strong correlation between personal use of

corporate aircraft by CEOs and membership of long-distance golf clubs.

Empire building is also called thefree cash flow problem following Michael

Jensen's influential 1986 paper.16 Empire building consists of the management pur

suing growth rather than shareholder-value maximisation. While there is a link

between the two, growth does not necessarily generate shareholder value and vice

versa. If managers are to act in the interests of the shareholders, they should only

invest in so-called positive net present value (NPV) projects, i.e. projects whose

future expected cash flows exceed their initial investment outlay.17 Any cash flow

that remains after investing in all available positive-NPV projects is the so-called

free cash flow. Projects with negative NPVs are projects whose future expected

cash flows are lower than the initial investment outlay and hence destroy rather

than create shareholder value. Empire building may come in various forms, but

frequently consists of the management going on a shopping spree and buying up

other firms, sometimes even firms that operate in business sectors that are com

pletely unrelated to the business sector the management's firm operates in. Again,

empire building can be seen as the refusal of the company's management to pay

out the free cash flow when there are no positive NPV projects available. While

a company may have limited investment opportunities, this is typically not the

case for its shareholders, who have access to a wide range of investment opportu

nities. Hence, it makes sense for the company's management to pay out the free

cash flows to its shareholders and give the latter the opportunity to reinvest the

funds in positive-NPV projects. So why would managers be tempted to engage in

empire building? Managers derive benefits from increasing the size of their firm.

Such benefits include an increase in their power and social status from running a

larger firm. As we shall see in Chapter 5, managerial compensation has also been

reported to grow in line with company size. Hence, there are clear benefits that

managers derive from engaging in growth strategies whereas the costs are borne by

the shareholders.

Finally, managerial entrenchment, whereby managers shield themselves from

hostile takeovers and internal disciplinary actions, may also be a consequence of

the principal-agent problem. However, managerial entrenchment may also exist in

the presence of concentrated family control whereby top management posts within

the family are passed on to the next generation of the family rather than filled by

the most suitable candidate in the managerial labour market.

- The agency problems of debt and equity

So far, we have focused on the agency problem that may exist between the managers

and the shareholders. However, there exists a second type of agency problem. This

agency problem relates to the other main source of financing which is debt. When a

firm has very little equity financing left (such as in a situation of financial distress),

1 .5 T H E AGENCY PROBLEMS OF D EBT AND EQUITY 1 1

are first disclosed the stock price decreases by roughly 1 %.15 Over the long run,

firms that allow their CEO to use their jets for personal use underperform by 4%

which is significantly more than the cost of the corporate resources the CEO con

sumes. Yermack justifies this decline in the stock price by the fact that perks are

typically disclosed beforebad news is disclosed to the shareholders. Yermack con

cludes that CEOs postpone the disclosure of bad news until they have secured the

perks. Funnily enough, Yermack finds a strong correlation between personal use of

corporate aircraft by CEOs and membership of long-distance golf clubs.

Empire building is also called thefree cash flow problem following Michael

Jensen's influential 1986 paper.16 Empire building consists of the management pur

suing growth rather than shareholder-value maximisation. While there is a link

between the two, growth does not necessarily generate shareholder value and vice

versa. If managers are to act in the interests of the shareholders, they should only

invest in so-called positive net present value (NPV) projects, i.e. projects whose

future expected cash flows exceed their initial investment outlay.17 Any cash flow

that remains after investing in all available positive-NPV projects is the so-called

free cash flow. Projects with negative NPVs are projects whose future expected

cash flows are lower than the initial investment outlay and hence destroy rather

than create shareholder value. Empire building may come in various forms, but

frequently consists of the management going on a shopping spree and buying up

other firms, sometimes even firms that operate in business sectors that are com

pletely unrelated to the business sector the management's firm operates in. Again,

empire building can be seen as the refusal of the company's management to pay

out the free cash flow when there are no positive NPV projects available. While

a company may have limited investment opportunities, this is typically not the

case for its shareholders, who have access to a wide range of investment opportu

nities. Hence, it makes sense for the company's management to pay out the free

cash flows to its shareholders and give the latter the opportunity to reinvest the

funds in positive-NPV projects. So why would managers be tempted to engage in

empire building? Managers derive benefits from increasing the size of their firm.

Such benefits include an increase in their power and social status from running a

larger firm. As we shall see in Chapter 5, managerial compensation has also been

reported to grow in line with company size. Hence, there are clear benefits that

managers derive from engaging in growth strategies whereas the costs are borne by

the shareholders.

Finally, managerial entrenchment, whereby managers shield themselves from

hostile takeovers and internal disciplinary actions, may also be a consequence of

the principal-agent problem. However, managerial entrenchment may also exist in

the presence of concentrated family control whereby top management posts within

the family are passed on to the next generation of the family rather than filled by

the most suitable candidate in the managerial labour market.

- The agency problems of debt and equity

So far, we have focused on the agency problem that may exist between the managers

and the shareholders. However, there exists a second type of agency problem. This

agency problem relates to the other main source of financing which is debt. When a

firm has very little equity financing left (such as in a situation of financial distress),

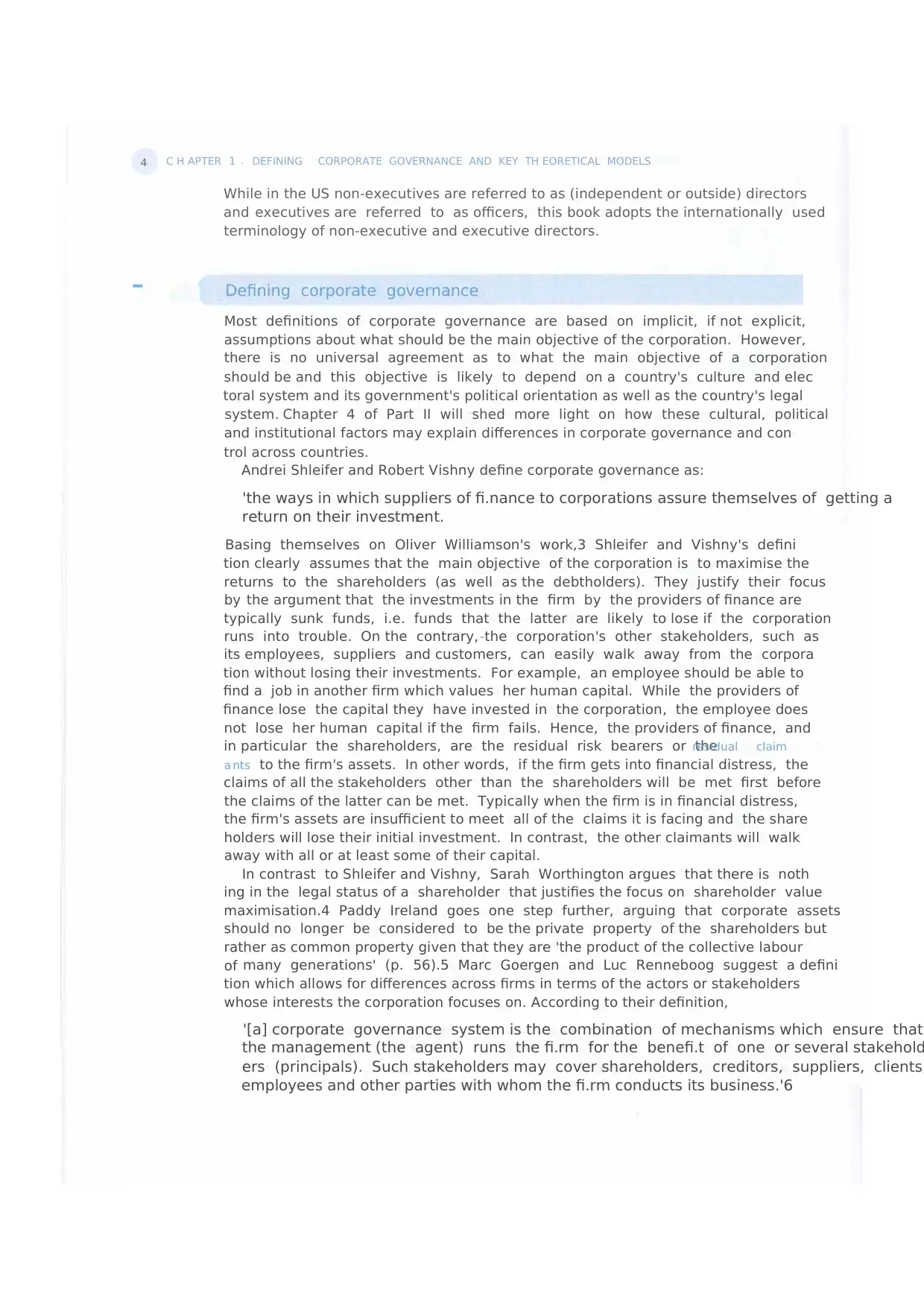

1 2 C HAPTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

the shareholders may be tempted to gamble with the debtholders' money by invest

ing the firm's funds into high-risk projects. If the risky projects fail, the major part of

the costs will be incurred by the debtholders. However, if these projects are success

ful and generate a massive payoff, most of this payoff will go to the shareholders.

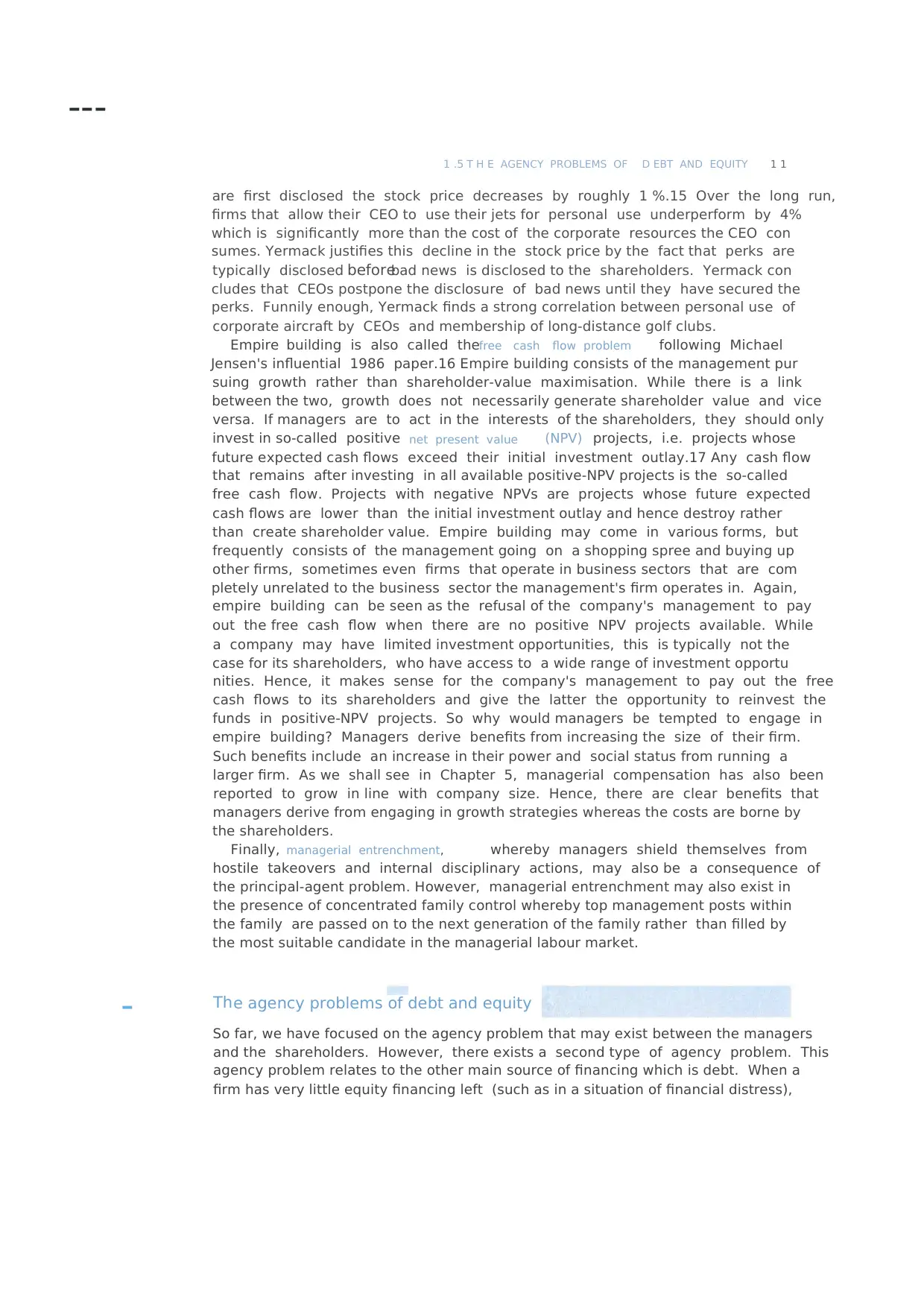

Figure 1.2 illustrates how this works. Remember that the debtholders' claims are

more senior than those of the shareholders. This implies that when the firm's assets

are insufficient to meet all the claims it is facing, it will first meet the claims of the

debtholders. Hence, the value of the debt increases as the value of the firm's assets

increases until it hits an upper bound. This upper bound consists of the situation

where the firm has at least sufficient assets to reimburse the debtholders and to pay

the contractual interest payments on the debt. In other words, the value of the debt

holders' claims has a limited upside. Conversely, the claims of the equity holders,

i.e. the shareholders, have an unlimited upside. This difference in the upside of the

two types of claims explains why it makes sense in certain situations for the share

holders to gamble with the money of the debtholders.18

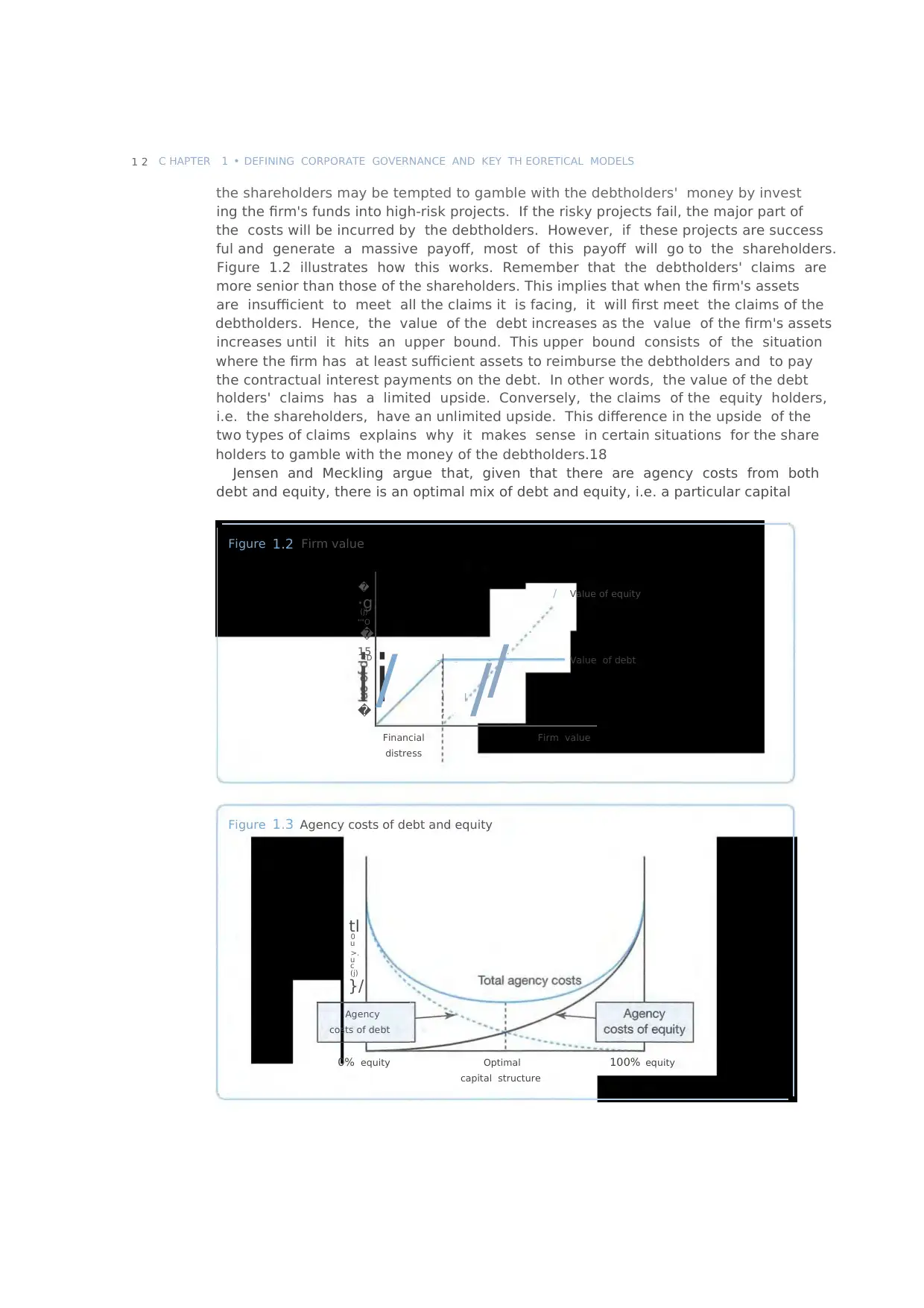

Jensen and Meckling argue that, given that there are agency costs from both

debt and equity, there is an optimal mix of debt and equity, i.e. a particular capital

Figure 1.2 Firm value

�

·g. / Value of equity

(j)

""O

� .

15 •

<D - -- - --- Value of debt

i i/ ! . //� : ,,'

' .

Financial

distress

Firm value

Figure 1.3 Agency costs of debt and equity

tl0

u

>.

u

c

(j)

}/

Agency

costs of debt

0% equity Optimal

capital structure

100% equity

the shareholders may be tempted to gamble with the debtholders' money by invest

ing the firm's funds into high-risk projects. If the risky projects fail, the major part of

the costs will be incurred by the debtholders. However, if these projects are success

ful and generate a massive payoff, most of this payoff will go to the shareholders.

Figure 1.2 illustrates how this works. Remember that the debtholders' claims are

more senior than those of the shareholders. This implies that when the firm's assets

are insufficient to meet all the claims it is facing, it will first meet the claims of the

debtholders. Hence, the value of the debt increases as the value of the firm's assets

increases until it hits an upper bound. This upper bound consists of the situation

where the firm has at least sufficient assets to reimburse the debtholders and to pay

the contractual interest payments on the debt. In other words, the value of the debt

holders' claims has a limited upside. Conversely, the claims of the equity holders,

i.e. the shareholders, have an unlimited upside. This difference in the upside of the

two types of claims explains why it makes sense in certain situations for the share

holders to gamble with the money of the debtholders.18

Jensen and Meckling argue that, given that there are agency costs from both

debt and equity, there is an optimal mix of debt and equity, i.e. a particular capital

Figure 1.2 Firm value

�

·g. / Value of equity

(j)

""O

� .

15 •

<D - -- - --- Value of debt

i i/ ! . //� : ,,'

' .

Financial

distress

Firm value

Figure 1.3 Agency costs of debt and equity

tl0

u

>.

u

c

(j)

}/

Agency

costs of debt

0% equity Optimal

capital structure

100% equity

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.