Integrating CSR into Corporate Governance: A Stakeholder Approach

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/08

|11

|6917

|187

Report

AI Summary

This report addresses the growing discord surrounding Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its potential to become a superficial part of corporate strategy. It introduces a new conceptual framework for embedding CSR within corporate governance using a stakeholder systems approach. The framework integrates company, shareholder, and wider stakeholder concerns, delineating key stages of the governance process to align profit-centered and social responsibility objectives. By incorporating stakeholder evaluations and focusing on organizational justice, the model aims to balance effectiveness and equity expectations, turning values into processes for sustainable business practices. It emphasizes the importance of multi-stakeholder perspectives and linking macro-level CSR activities with micro-level consequences, ultimately seeking to reconcile the conflicts between CSR rhetoric and the reality of corporate governance systems.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchga

Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility in

Corporate Governance: A Stakeholder Systems

Approach

Article in Journal of Business Ethics · January 2014

DOI: 10.1007/s10551-012-1615-9

CITATIONS

24

READS

1,467

2 authors, including:

Chris Mason

Swinburne University of Technology

28PUBLICATIONS200CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on Research

letting you access and read them immediately.

Available from: Chris Mason

Retrieved on: 19 September

Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility in

Corporate Governance: A Stakeholder Systems

Approach

Article in Journal of Business Ethics · January 2014

DOI: 10.1007/s10551-012-1615-9

CITATIONS

24

READS

1,467

2 authors, including:

Chris Mason

Swinburne University of Technology

28PUBLICATIONS200CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on Research

letting you access and read them immediately.

Available from: Chris Mason

Retrieved on: 19 September

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility in Corporate

Governance: A Stakeholder Systems Approach

Chris Mason• John Simmons

Received: 26 April 2012 / Accepted: 30 December 2012

Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract Currentresearch on corporate socialresponsi-

bility (CSR) illustrates the growing sense of discord sur-

roundingthe ‘businessof doing good’ (Dobersand

Springett,Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manage 17(2):

63–69,2010).Central to these concerns is that CSR risks

becoming an over-simplified and peripheralpartof cor-

porate strategy.Ratherthan transforming the dominant

corporate discourse,it is argued thatCSR and related

concepts are limited to ‘‘emancipatory rhetoric…defined

by narrow business interests and serve to curtail interests of

externalstakeholders.’’(Banerjee,Crit Sociol 34(1):52,

2008).The paperaddressesgapsin the literatureand

challenges currentthinking on corporate governance and

CSR by offering a new conceptualframeworkthat

responds to the concerns of researchers and practitioners.

The limited focus ofexisting analyses is extended by a

holistic approachto corporategovernanceand social

responsibility thatintegratescompany,shareholderand

wider stakeholder concerns.A defensive stance is avoided

by delineating key stages of the governance process and

aligning profit centred and social responsibility concerns to

produce a business-based rationale for minimising risk and

mainstreaming CSR.

Keywords Corporate governance Corporate social

responsibility Stakeholder systems

Introduction

Currentresearch on corporate socialresponsibility (CSR)

illustrates the growing sense ofdiscord surrounding the

businessof doing good (Dobersand Springett2010).

Centralto these concerns is thatCSR risks becoming an

over-simplified and peripheralpartof corporate strategy.

Rather than transforming the dominant corporate discours

it is argued thatCSR and related concepts are limited to

‘emancipatory rhetoric… defined by narrow business

interests and serve to curtailinterests ofexternalstake-

holders’ (Banerjee 2008,p. 52).The focalpointof criti-

cism on CSR is the boards of directors,as this key group

defines and implements corporate strategy,and serves to

safeguard theinterestsof key beneficiaries.Thus, we

contend that a gap in research knowledge exists relating t

CSR and its enactmentthroughcorporategovernance

systems. We respond to this gap by focusing on CSR’s role

in corporate governance by offering a new conceptual

framework.To addressthe limited knowledge we have

used a holistic approach to corporate governance and CSR

that integrates company, shareholder and wider stakehold

concerns.A defensive stance has been avoided by delin-

eating key stages of the governance process and aligning

profit-centred and social responsibility concerns to produc

a business-based rationale forminimising financialrisk

and mainstreaming CSR (Paulet2011;Katsoulakosand

Katsoulakos 2007).We have also addressed the discon-

nection of many salientstakeholders from company deci-

sions on CSR by incorporating stakeholder evaluation of

C. Mason (&)

Faculty of Business and Enterprise,Swinburne University

of Technology,Hawthorn Campus,Melbourne,VIC 3122,

Australia

e-mail: Chris.mason@swin.edu.au

J. Simmons

Liverpool Management School,University of Liverpool,

Chatham Street,Liverpool L69 7ZH,UK

123

J Bus Ethics

DOI 10.1007/s10551-012-1615-9

Governance: A Stakeholder Systems Approach

Chris Mason• John Simmons

Received: 26 April 2012 / Accepted: 30 December 2012

Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract Currentresearch on corporate socialresponsi-

bility (CSR) illustrates the growing sense of discord sur-

roundingthe ‘businessof doing good’ (Dobersand

Springett,Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manage 17(2):

63–69,2010).Central to these concerns is that CSR risks

becoming an over-simplified and peripheralpartof cor-

porate strategy.Ratherthan transforming the dominant

corporate discourse,it is argued thatCSR and related

concepts are limited to ‘‘emancipatory rhetoric…defined

by narrow business interests and serve to curtail interests of

externalstakeholders.’’(Banerjee,Crit Sociol 34(1):52,

2008).The paperaddressesgapsin the literatureand

challenges currentthinking on corporate governance and

CSR by offering a new conceptualframeworkthat

responds to the concerns of researchers and practitioners.

The limited focus ofexisting analyses is extended by a

holistic approachto corporategovernanceand social

responsibility thatintegratescompany,shareholderand

wider stakeholder concerns.A defensive stance is avoided

by delineating key stages of the governance process and

aligning profit centred and social responsibility concerns to

produce a business-based rationale for minimising risk and

mainstreaming CSR.

Keywords Corporate governance Corporate social

responsibility Stakeholder systems

Introduction

Currentresearch on corporate socialresponsibility (CSR)

illustrates the growing sense ofdiscord surrounding the

businessof doing good (Dobersand Springett2010).

Centralto these concerns is thatCSR risks becoming an

over-simplified and peripheralpartof corporate strategy.

Rather than transforming the dominant corporate discours

it is argued thatCSR and related concepts are limited to

‘emancipatory rhetoric… defined by narrow business

interests and serve to curtailinterests ofexternalstake-

holders’ (Banerjee 2008,p. 52).The focalpointof criti-

cism on CSR is the boards of directors,as this key group

defines and implements corporate strategy,and serves to

safeguard theinterestsof key beneficiaries.Thus, we

contend that a gap in research knowledge exists relating t

CSR and its enactmentthroughcorporategovernance

systems. We respond to this gap by focusing on CSR’s role

in corporate governance by offering a new conceptual

framework.To addressthe limited knowledge we have

used a holistic approach to corporate governance and CSR

that integrates company, shareholder and wider stakehold

concerns.A defensive stance has been avoided by delin-

eating key stages of the governance process and aligning

profit-centred and social responsibility concerns to produc

a business-based rationale forminimising financialrisk

and mainstreaming CSR (Paulet2011;Katsoulakosand

Katsoulakos 2007).We have also addressed the discon-

nection of many salientstakeholders from company deci-

sions on CSR by incorporating stakeholder evaluation of

C. Mason (&)

Faculty of Business and Enterprise,Swinburne University

of Technology,Hawthorn Campus,Melbourne,VIC 3122,

Australia

e-mail: Chris.mason@swin.edu.au

J. Simmons

Liverpool Management School,University of Liverpool,

Chatham Street,Liverpool L69 7ZH,UK

123

J Bus Ethics

DOI 10.1007/s10551-012-1615-9

the effectiveness and equity of system outcomes ateach

stage of the governance model that the paper proposes.

Corporate Governance and CSR: A Combined

Stakeholder Perspective

Corporate governance is conceptualised as the creation and

implementation of processes seeking to optimise returns to

shareholderswhile satisfying the legitimate demandsof

stakeholders (Durden 2008).Aligned with this,we have

adopted Sachs etal. (2006) approach thataligns a stake-

holderperspectiveof CSR and corporategovernance.

Viewing corporate governance through a stakeholder lens

broadenstraditionalshareholder-centricand hub-spoke

approachesto organisation–stakeholderrelationships

(Andriof et al. 2002). It facilitates consideration of a wider

rangeof corporategovernanceissues,contributesto

stakeholdermanagementdecisionson ‘who and what

really counts’ (Mitchell et al. 1997), and extends company

directorduties to include formalconsideration ofstake-

holder perspectives and agendas.Stakeholder approaches

also facilitate a heightened awareness ofCSR, business

ethics,and business practices thatenable more informed

decisions on stakeholder salience (Fassin 2010) and more

robust CSR evaluations (Fassin and Buelens 2011).

Greater recognition of stakeholder perceptions of CSR

may also addresses issues identified in recent research, that

stakeholder engagement in corporate governance is largely

characterised by low powerand low influence (Spitzeck

and Hansen 2010); that the salience of a stakeholder group

is a potent antecedent of an organisation’s perceived social

obligation to them (Mishra and Suar 2010); and that gov-

ernance processes generally failto accord to stakeholder

expectations(Law 2011).Stakeholdertheory also high-

lights organisationaljustice,and the awareness ofstake-

holder perspectives on the equity of corporate governance

(Freeman 2010).It also challenges the primacy thatcor-

porate governance traditionally accordsshareholders,of

being residual risk-takers.

Consequently,we synthesised a key rationale as com-

prising the need forCSR analysesto adopta systemic

approach to balance shareholder and stakeholder interests,

and to incorporate methods of corporate governance cor-

responding with CSR.There is significant support for this

rationale.Existing research advocates conceptualframe-

works that include ethical standards,structures,processes,

and performance (Svensson and Wood 2011), or ones that

differentiate system principles,procedures and effective-

ness (Cegarra-Navarroand Martinez-Martinez2009).

However,we are mindfulthatreplacing a shareholder-

centric mode of corporate governance with one focused on

ethicalconcernsis unlikely to find favourwithin the

business community. Yet acceptance that a wider range o

stakeholders have legitimate expectations has resulted in

proposals to align profitcentred and socialresponsibility

modelsof corporate governance (Waring 2008),and to

balance‘shareholdervalue creation’with ‘stakeholder

value protection’ (Law 2011). Indeed, some studies sugge

that the maximisation of shareholder value may well entai

company directors pursuing a widerrange ofsocialand

economic objectives that are consistent with CSR (Tudgay

and Pascal 2006).

A broader-based auditof CSR can evaluate corporate

governance systems,policies,and outcomes in relation to

their contribution to business effectiveness, as well as how

well they meet stakeholder expectations of customer care

employeeinvolvement,appropriaterelationshipswith

government,and sustainability.The corporate failures and

malfeasance of the 1990s, together with their reappearanc

in the recentbanking crisis,have increased systemic risk

(Paulet 2011). This has prompted calls from sections of the

business community, politicians, and the general public fo

more timely,comprehensiveand rigorousmethodsof

corporate governance thataccord with CSR principles of

inclusivity, materiality, and responsiveness (Rasche 2010)

We have responded to these calls by offering a combined

systemsapproach thatseeksto reconcilethe conflicts

between CSR rhetoric and the reality of corporate gover-

nance systems and their capabilities.

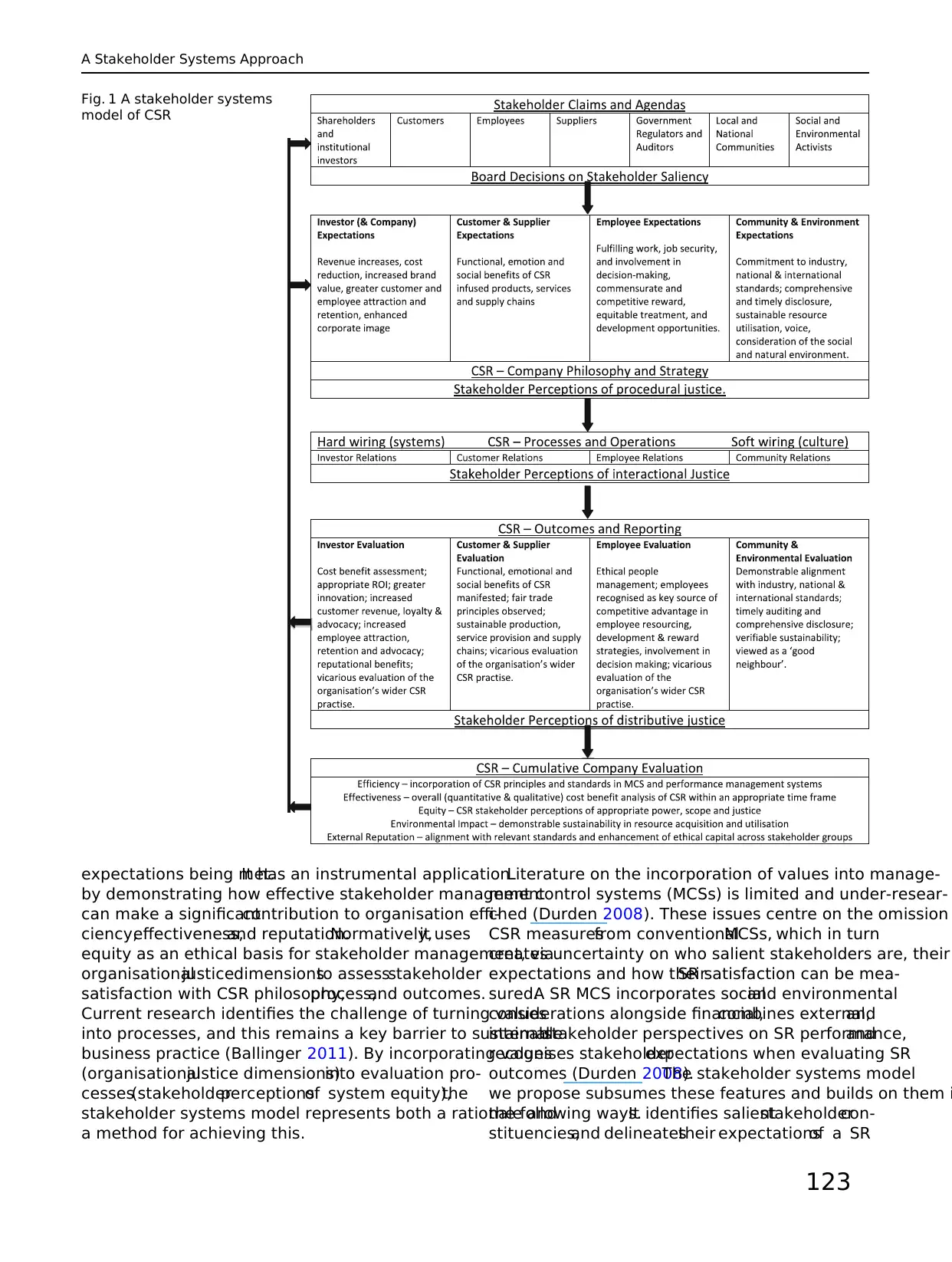

A Stakeholder Systems Model of CSR: Overview

Limitationsin currentpractice ofcorporate governance

require a new conceptualframework thatbalances effec-

tiveness and equity expectations ofCSR. Our approach

therefore aligns with longstanding views thatthe purpose

of organisations is to delivereconomic and ethicalper-

formance to society (Sherwin 1983). Effectiveness has been

assessedbasedon CSR’s contributionto organisation

objectives,and equity expectationsby stakeholderper-

ceptions ofhow they are treated by the organisation in

CSR-relatedcontexts.Donaldsonand Preston(1995)

claimed that all stakeholder theories contain three separat

attributes.‘Descriptive’ in thatthey involve a description

of how organisations operate;‘instrumental’in thatthey

examine how stakeholdermanagementcan contribute to

the achievement of organisation goals; and ‘normative’ in

thatthey provide an ethicalrationale forapproaches to

stakeholder management (Fig.1).

The stakeholder systems modelthatwe propose incor-

porates these three attributes. It can be used descriptively

identify particular stakeholder groups’ expectations of the

organisation,how organisations respond to these expecta-

tions,and theimplicationsfor both partieswith their

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

stage of the governance model that the paper proposes.

Corporate Governance and CSR: A Combined

Stakeholder Perspective

Corporate governance is conceptualised as the creation and

implementation of processes seeking to optimise returns to

shareholderswhile satisfying the legitimate demandsof

stakeholders (Durden 2008).Aligned with this,we have

adopted Sachs etal. (2006) approach thataligns a stake-

holderperspectiveof CSR and corporategovernance.

Viewing corporate governance through a stakeholder lens

broadenstraditionalshareholder-centricand hub-spoke

approachesto organisation–stakeholderrelationships

(Andriof et al. 2002). It facilitates consideration of a wider

rangeof corporategovernanceissues,contributesto

stakeholdermanagementdecisionson ‘who and what

really counts’ (Mitchell et al. 1997), and extends company

directorduties to include formalconsideration ofstake-

holder perspectives and agendas.Stakeholder approaches

also facilitate a heightened awareness ofCSR, business

ethics,and business practices thatenable more informed

decisions on stakeholder salience (Fassin 2010) and more

robust CSR evaluations (Fassin and Buelens 2011).

Greater recognition of stakeholder perceptions of CSR

may also addresses issues identified in recent research, that

stakeholder engagement in corporate governance is largely

characterised by low powerand low influence (Spitzeck

and Hansen 2010); that the salience of a stakeholder group

is a potent antecedent of an organisation’s perceived social

obligation to them (Mishra and Suar 2010); and that gov-

ernance processes generally failto accord to stakeholder

expectations(Law 2011).Stakeholdertheory also high-

lights organisationaljustice,and the awareness ofstake-

holder perspectives on the equity of corporate governance

(Freeman 2010).It also challenges the primacy thatcor-

porate governance traditionally accordsshareholders,of

being residual risk-takers.

Consequently,we synthesised a key rationale as com-

prising the need forCSR analysesto adopta systemic

approach to balance shareholder and stakeholder interests,

and to incorporate methods of corporate governance cor-

responding with CSR.There is significant support for this

rationale.Existing research advocates conceptualframe-

works that include ethical standards,structures,processes,

and performance (Svensson and Wood 2011), or ones that

differentiate system principles,procedures and effective-

ness (Cegarra-Navarroand Martinez-Martinez2009).

However,we are mindfulthatreplacing a shareholder-

centric mode of corporate governance with one focused on

ethicalconcernsis unlikely to find favourwithin the

business community. Yet acceptance that a wider range o

stakeholders have legitimate expectations has resulted in

proposals to align profitcentred and socialresponsibility

modelsof corporate governance (Waring 2008),and to

balance‘shareholdervalue creation’with ‘stakeholder

value protection’ (Law 2011). Indeed, some studies sugge

that the maximisation of shareholder value may well entai

company directors pursuing a widerrange ofsocialand

economic objectives that are consistent with CSR (Tudgay

and Pascal 2006).

A broader-based auditof CSR can evaluate corporate

governance systems,policies,and outcomes in relation to

their contribution to business effectiveness, as well as how

well they meet stakeholder expectations of customer care

employeeinvolvement,appropriaterelationshipswith

government,and sustainability.The corporate failures and

malfeasance of the 1990s, together with their reappearanc

in the recentbanking crisis,have increased systemic risk

(Paulet 2011). This has prompted calls from sections of the

business community, politicians, and the general public fo

more timely,comprehensiveand rigorousmethodsof

corporate governance thataccord with CSR principles of

inclusivity, materiality, and responsiveness (Rasche 2010)

We have responded to these calls by offering a combined

systemsapproach thatseeksto reconcilethe conflicts

between CSR rhetoric and the reality of corporate gover-

nance systems and their capabilities.

A Stakeholder Systems Model of CSR: Overview

Limitationsin currentpractice ofcorporate governance

require a new conceptualframework thatbalances effec-

tiveness and equity expectations ofCSR. Our approach

therefore aligns with longstanding views thatthe purpose

of organisations is to delivereconomic and ethicalper-

formance to society (Sherwin 1983). Effectiveness has been

assessedbasedon CSR’s contributionto organisation

objectives,and equity expectationsby stakeholderper-

ceptions ofhow they are treated by the organisation in

CSR-relatedcontexts.Donaldsonand Preston(1995)

claimed that all stakeholder theories contain three separat

attributes.‘Descriptive’ in thatthey involve a description

of how organisations operate;‘instrumental’in thatthey

examine how stakeholdermanagementcan contribute to

the achievement of organisation goals; and ‘normative’ in

thatthey provide an ethicalrationale forapproaches to

stakeholder management (Fig.1).

The stakeholder systems modelthatwe propose incor-

porates these three attributes. It can be used descriptively

identify particular stakeholder groups’ expectations of the

organisation,how organisations respond to these expecta-

tions,and theimplicationsfor both partieswith their

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

expectations being met.It has an instrumental application

by demonstrating how effective stakeholder management

can make a significantcontribution to organisation effi-

ciency,effectiveness,and reputation.Normatively,it uses

equity as an ethical basis for stakeholder management, via

organisationaljusticedimensionsto assessstakeholder

satisfaction with CSR philosophy,process,and outcomes.

Current research identifies the challenge of turning values

into processes, and this remains a key barrier to sustainable

business practice (Ballinger 2011). By incorporating values

(organisationaljustice dimensions)into evaluation pro-

cesses(stakeholderperceptionsof system equity),the

stakeholder systems model represents both a rationale and

a method for achieving this.

Literature on the incorporation of values into manage-

ment control systems (MCSs) is limited and under-resear-

ched (Durden 2008). These issues centre on the omission

CSR measuresfrom conventionalMCSs, which in turn

creates uncertainty on who salient stakeholders are, their

expectations and how theirSR satisfaction can be mea-

sured.A SR MCS incorporates socialand environmental

considerations alongside financial,combines external,and

internalstakeholder perspectives on SR performance,and

recognises stakeholderexpectations when evaluating SR

outcomes (Durden 2008).The stakeholder systems model

we propose subsumes these features and builds on them i

the following ways.It identifies salientstakeholdercon-

stituencies,and delineatestheir expectationsof a SR

Fig. 1 A stakeholder systems

model of CSR

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

by demonstrating how effective stakeholder management

can make a significantcontribution to organisation effi-

ciency,effectiveness,and reputation.Normatively,it uses

equity as an ethical basis for stakeholder management, via

organisationaljusticedimensionsto assessstakeholder

satisfaction with CSR philosophy,process,and outcomes.

Current research identifies the challenge of turning values

into processes, and this remains a key barrier to sustainable

business practice (Ballinger 2011). By incorporating values

(organisationaljustice dimensions)into evaluation pro-

cesses(stakeholderperceptionsof system equity),the

stakeholder systems model represents both a rationale and

a method for achieving this.

Literature on the incorporation of values into manage-

ment control systems (MCSs) is limited and under-resear-

ched (Durden 2008). These issues centre on the omission

CSR measuresfrom conventionalMCSs, which in turn

creates uncertainty on who salient stakeholders are, their

expectations and how theirSR satisfaction can be mea-

sured.A SR MCS incorporates socialand environmental

considerations alongside financial,combines external,and

internalstakeholder perspectives on SR performance,and

recognises stakeholderexpectations when evaluating SR

outcomes (Durden 2008).The stakeholder systems model

we propose subsumes these features and builds on them i

the following ways.It identifies salientstakeholdercon-

stituencies,and delineatestheir expectationsof a SR

Fig. 1 A stakeholder systems

model of CSR

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

organisation;specifies the design,operation,evaluation,

and reporting stages of a SR MCS; links stakeholder per-

ceptions of whether their expectations have been met with

organisationaljustice dimensions;and relates an organi-

sation’scumulative evaluation ofSR outcomesto the

ways in which this information is disseminated.Thus,it

respondsto recentcalls to evaluate CSR from multi-

stakeholderperspectives(Mishra and Suar,2010),and

to link macro levelactivity (CSR)with its micro level

consequences(perceptionsof organisationaljustice)

(Rupp et al. 2006).

Stakeholder salience and organisationaljustice provide

the frame of reference that underpins the stakeholder sys-

tems model.The modelrepresents a holistic approach to

corporate governance and CSR thatintegrates company,

shareholder,and wider stakeholder concerns. It recognises

the paradox thatsociety is demanding more ofbusiness

while simultaneously trusting itless (Rake and Grayson

2009). The implication is that responsible CSR is no longer

aboutindividualprojects or programmes,butrather how

the totality ofbusinessactivity impacts on organisation

stakeholderssuch as customers,suppliers,employees,

communities, government, and the environment (Rake and

Grayson 2009).

The main stagesof the stakeholdersystemsmodel

therefore comprise the following. First, the model identifies

the stakeholder groups that seek recognition of their CSR

claims and agendas in the corporate governance process.

Second,it analyses the factors thatinfluence board deci-

sionson stakeholdersalience and delineatesthe stake-

holder constituenciestypically accordedsaliencein

corporategovernance.Third, it providesa method of

evaluating stakeholder satisfaction with CSR effectiveness

and equity at the strategy, operations, and outcomes stages

of the corporate governance system.Finally,it offers a

framework forincorporating stakeholderassessmentsin

overall company evaluation of CSR, as well as determining

how effectively such evaluation is actioned and commu-

nicated to stakeholders.

Organisational Justice and the Socially Responsible

Organisation

We have utilised organisational justice to develop an ethical

framework thatcan be applied in CSR contexts,drawing

from a Rawlsian view of justice as the pre-eminent value of

socialinstitutions (Ahmed and Machold 2004).Organisa-

tionaljustice has been defined as the study of fairness at

work,and the literature suggests it has three distinct com-

ponents:distributive,procedural,and interactionaljustice

(Palaiologos et al. 2011). Distributive justice relates to the

perceived fairness of the outcomes that individuals or groups

receive from an organisational system, procedural justice

the perceived fairness of the processes used to determine

outcomes ofthe system,and interactionaljustice is the

perceived fairness of the interpersonal treatment individua

or groups receive from the organsation.

The concept of organisational justice can be extended b

applying itto stakeholderperceptions ofequitable treat-

mentin an organisation context,together with stakehold-

ers’ attitudinaland behaviouralresponsesto such

perceptions.Componentsof organisationaljusticeare

related to stakeholder perceptions of equity in the above

three CSR domains,and are therefore utilised at different

stages of the stakeholder systems model.The distribution

of organisation resources as an outcome of CSR decision-

making determinesthe levelof distributive justice;the

equity of CSR systems relates to stakeholder perceptions o

procedural justice; and how fairly managers treat employ-

ees in the enactment of CSR systems determines their lev

of interactionaljustice (Erdogan etal. 2001).The use of

organisationaljustice alignswith equity theory in sug-

gestingthat stakeholdersreducetheir commitmentto

organisation systems they believe treat them unfairly (Flin

1999).It also aligns with psychologicalcontractresearch

thatindicatesstakeholdersupportis more likely when

factors thatgive rise to mutuality are presentin the cor-

porate governance system (Rousseau 2001). Organisation

justice dimensions therefore represent strong rationales fo

stakeholder viewpoints to be recognised as key measures

the equity of CSR systems.

A normative rationale for the stakeholder systems mode

is further developed by utilising Niebuhr and Gustafson’s

concept of ‘the responsible self’ (1963). This suggests that

individuals act responsibly if they consider the consequenc

of envisaged actions for those affected by them in a mann

analogous to the ‘ethical foresight’ capability identified by

Nijhof and Jeurissen (2006). We relate this to CSR contexts

by proposing the concept of ‘the responsible organisation’

Responsible organisations are those whose corporate gov-

ernance systems recognise relationships with a range of

stakeholders,and establish systems to facilitate fairdis-

course with them on potential strategy initiatives (Simmon

2008). Such organisations demonstrate ethical foresight b

anticipating thepossibleconsequencesof their actions

within their sphere of influence (Nijhof and Jeurissen 2006

While many organisations recognise instrumental ratio-

nales for dialogue with stakeholders thatcan facilitate or

impede organisation actions,the responsible organisation

goes further by acknowledging a duty of care for all stake-

holders,including those who are affected by organisation

decision-making butwho have limited scope to influence

this.The participatory stance of responsible organisations

towards stakeholders is similar to Kohlberg’s (1969) ‘just

community’ theory, where members engage in meaningfu

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

and reporting stages of a SR MCS; links stakeholder per-

ceptions of whether their expectations have been met with

organisationaljustice dimensions;and relates an organi-

sation’scumulative evaluation ofSR outcomesto the

ways in which this information is disseminated.Thus,it

respondsto recentcalls to evaluate CSR from multi-

stakeholderperspectives(Mishra and Suar,2010),and

to link macro levelactivity (CSR)with its micro level

consequences(perceptionsof organisationaljustice)

(Rupp et al. 2006).

Stakeholder salience and organisationaljustice provide

the frame of reference that underpins the stakeholder sys-

tems model.The modelrepresents a holistic approach to

corporate governance and CSR thatintegrates company,

shareholder,and wider stakeholder concerns. It recognises

the paradox thatsociety is demanding more ofbusiness

while simultaneously trusting itless (Rake and Grayson

2009). The implication is that responsible CSR is no longer

aboutindividualprojects or programmes,butrather how

the totality ofbusinessactivity impacts on organisation

stakeholderssuch as customers,suppliers,employees,

communities, government, and the environment (Rake and

Grayson 2009).

The main stagesof the stakeholdersystemsmodel

therefore comprise the following. First, the model identifies

the stakeholder groups that seek recognition of their CSR

claims and agendas in the corporate governance process.

Second,it analyses the factors thatinfluence board deci-

sionson stakeholdersalience and delineatesthe stake-

holder constituenciestypically accordedsaliencein

corporategovernance.Third, it providesa method of

evaluating stakeholder satisfaction with CSR effectiveness

and equity at the strategy, operations, and outcomes stages

of the corporate governance system.Finally,it offers a

framework forincorporating stakeholderassessmentsin

overall company evaluation of CSR, as well as determining

how effectively such evaluation is actioned and commu-

nicated to stakeholders.

Organisational Justice and the Socially Responsible

Organisation

We have utilised organisational justice to develop an ethical

framework thatcan be applied in CSR contexts,drawing

from a Rawlsian view of justice as the pre-eminent value of

socialinstitutions (Ahmed and Machold 2004).Organisa-

tionaljustice has been defined as the study of fairness at

work,and the literature suggests it has three distinct com-

ponents:distributive,procedural,and interactionaljustice

(Palaiologos et al. 2011). Distributive justice relates to the

perceived fairness of the outcomes that individuals or groups

receive from an organisational system, procedural justice

the perceived fairness of the processes used to determine

outcomes ofthe system,and interactionaljustice is the

perceived fairness of the interpersonal treatment individua

or groups receive from the organsation.

The concept of organisational justice can be extended b

applying itto stakeholderperceptions ofequitable treat-

mentin an organisation context,together with stakehold-

ers’ attitudinaland behaviouralresponsesto such

perceptions.Componentsof organisationaljusticeare

related to stakeholder perceptions of equity in the above

three CSR domains,and are therefore utilised at different

stages of the stakeholder systems model.The distribution

of organisation resources as an outcome of CSR decision-

making determinesthe levelof distributive justice;the

equity of CSR systems relates to stakeholder perceptions o

procedural justice; and how fairly managers treat employ-

ees in the enactment of CSR systems determines their lev

of interactionaljustice (Erdogan etal. 2001).The use of

organisationaljustice alignswith equity theory in sug-

gestingthat stakeholdersreducetheir commitmentto

organisation systems they believe treat them unfairly (Flin

1999).It also aligns with psychologicalcontractresearch

thatindicatesstakeholdersupportis more likely when

factors thatgive rise to mutuality are presentin the cor-

porate governance system (Rousseau 2001). Organisation

justice dimensions therefore represent strong rationales fo

stakeholder viewpoints to be recognised as key measures

the equity of CSR systems.

A normative rationale for the stakeholder systems mode

is further developed by utilising Niebuhr and Gustafson’s

concept of ‘the responsible self’ (1963). This suggests that

individuals act responsibly if they consider the consequenc

of envisaged actions for those affected by them in a mann

analogous to the ‘ethical foresight’ capability identified by

Nijhof and Jeurissen (2006). We relate this to CSR contexts

by proposing the concept of ‘the responsible organisation’

Responsible organisations are those whose corporate gov-

ernance systems recognise relationships with a range of

stakeholders,and establish systems to facilitate fairdis-

course with them on potential strategy initiatives (Simmon

2008). Such organisations demonstrate ethical foresight b

anticipating thepossibleconsequencesof their actions

within their sphere of influence (Nijhof and Jeurissen 2006

While many organisations recognise instrumental ratio-

nales for dialogue with stakeholders thatcan facilitate or

impede organisation actions,the responsible organisation

goes further by acknowledging a duty of care for all stake-

holders,including those who are affected by organisation

decision-making butwho have limited scope to influence

this.The participatory stance of responsible organisations

towards stakeholders is similar to Kohlberg’s (1969) ‘just

community’ theory, where members engage in meaningfu

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

dialogue overmattersof moralsignificance (Maclagan

2007). We recognise that this view of the corporation and its

role in society represents a challenge to currentbusiness

models. However, this view is supported by others who have

a similar vision of the ‘responsible and sustainable corpo-

ration’, and whose point of departure is also the company’s

relationship with its stakeholders (e.g., Lozano 2008).

Integrating Normative and Instrumental Expectations

of CSR

A longstanding dichotomy in CSR literature is the basis on

which organisationsshould managetheir stakeholder

relationships (Roberts 1992). One school of thought adopts

a normative approach and evaluates CSR on whetherit

represents SR behaviourtowards stakeholders,while the

other (instrumental) approach assesses the extent to which

stakeholder awareness of an organisation’s CSR activities

enhances corporate performance and reputation. Mindful of

the two perspectives, we suggest that they do not represent

a ‘zero sum game’ whereby acceptance of one obviates the

other. Ethical principles are compatible with profit seeking

aims, as long-term,sustainablebusinessperformance

necessitates regard for the organisation’s impact on wider

society and the environment (Jones 2012).

Some current research suggests that a CSR perspective

on business performance is bestachieved by considering

the voice of multiple stakeholders (Lozano 2005),which

we concurwith. However,a holistic assessmentwould

incorporate stakeholder evaluation of the effectiveness and

equity of CSR atthree stages:CSR strategy,CSR opera-

tions, and CSR results. Strategydecisionsdetermine

stakeholderperspectivesof the legitimacy ofCSR, the

implementationof CSR operationsshapesstakeholder

evaluation ofthe processesand how stakeholdersare

treated by them,and at the resultsstagestakeholders

evaluate how closely CSR outcomes match their expecta-

tions.While recognising effectiveness and equity expec-

tations ofCSR, we concentrate on the latter—a central

critique of CSR is thatit lacks any principle of justice to

guide the processof mediationbetweenstakeholders

(Koslowski 2000).

Stakeholder Claims and Agendas

Stakeholder often seek to influence an organisation’s CSR

philosophy and practice,with particulargroupssuch as

local and nationalcommunities,the media,government

and government agencies being seen as having a lesser or

episodic impact(e.g.Simmons 2008).Broaderconsider-

ation of stakeholder expectations is appropriate,as Archel

et al. (2011)found in an empiricalstudy ofCSR pro-

grammes in Spain,where stakeholder consultations often

resulted in a silencing of divergent voices from the domi-

nantCSR discourse.Thus,we have guardedly theorised

broad interpretations of the stakeholder expectations,each

of which has the capability to exert instrumental or moral

leverage on the focal organisation.While recognising that

notall stakeholders prioritise CSR,studies show thatan

increasing proportion regard an organisation’s stance on

CSR as a significant influence on their relationship with it

(Drews 2010).

Externalconstituenciesincludeinvestorswho want

profitable and socially responsible investmentthatalso

enhances corporate reputation;customers who seek prod-

ucts,services,and supply chainsthathave ‘green’cre-

dentials (Hess and Warren 2008);suppliers thatseek to

work in partnership with companies that respect fair trade

principles and do notabuse their monopoly power;gov-

ernment, regulators, and auditors seeking compliance with

legislation and codes ofconduct,internalmonitoring of

CSR practice,and transparency in CSR reporting;and

communities and pressure groups that expect companies

recognise the impactof theirCSR decision-making on

employmentand the environment.Employees constitute

the organisation’s internalstakeholders,with expectations

of demonstrated SR in its people managementpractices

and in treating otherstakeholders in line with employee

social values (Cheng and Ahmad 2010). Research suggest

that employeedecisionson retention,motivation,and

advocacy are influenced by this evaluation (Drews 2010).

The significance ofstakeholderexpectations is deter-

mined via an evaluation thatassessesthe legitimacy,

leverage, and urgency of stakeholder claims (Mitchell et a

1997).Managementdecisionson stakeholdersaliency

mean thatcertain stakeholderperspectives are acknowl-

edgedas requiringreconciliationwith thoseof other

stakeholder groups.We have followed Papasolomou et al.

(2005) in focusing on three main categories of stakeholder

expectation thatare likely to be recognised by organisa-

tions: investors,customers,and suppliers; employees; and

socialand environmentalgroups.The precise nature and

saliency ofstakeholderclaims—andtheir organisation

responses(Laudal,2011)—areinfluenced by thesize,

industrial sector and resources of the focal organisation, th

CSR-related expectationslikely to emanate from stake-

holder are described below.

The CSR System: Stakeholder Expectations

Our focus on stakeholder enables a more holistic view of

CSR. Key stakeholdergroupsanticipatethe beneficial

impact of CSR in the following ways. Investor expectations

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

2007). We recognise that this view of the corporation and its

role in society represents a challenge to currentbusiness

models. However, this view is supported by others who have

a similar vision of the ‘responsible and sustainable corpo-

ration’, and whose point of departure is also the company’s

relationship with its stakeholders (e.g., Lozano 2008).

Integrating Normative and Instrumental Expectations

of CSR

A longstanding dichotomy in CSR literature is the basis on

which organisationsshould managetheir stakeholder

relationships (Roberts 1992). One school of thought adopts

a normative approach and evaluates CSR on whetherit

represents SR behaviourtowards stakeholders,while the

other (instrumental) approach assesses the extent to which

stakeholder awareness of an organisation’s CSR activities

enhances corporate performance and reputation. Mindful of

the two perspectives, we suggest that they do not represent

a ‘zero sum game’ whereby acceptance of one obviates the

other. Ethical principles are compatible with profit seeking

aims, as long-term,sustainablebusinessperformance

necessitates regard for the organisation’s impact on wider

society and the environment (Jones 2012).

Some current research suggests that a CSR perspective

on business performance is bestachieved by considering

the voice of multiple stakeholders (Lozano 2005),which

we concurwith. However,a holistic assessmentwould

incorporate stakeholder evaluation of the effectiveness and

equity of CSR atthree stages:CSR strategy,CSR opera-

tions, and CSR results. Strategydecisionsdetermine

stakeholderperspectivesof the legitimacy ofCSR, the

implementationof CSR operationsshapesstakeholder

evaluation ofthe processesand how stakeholdersare

treated by them,and at the resultsstagestakeholders

evaluate how closely CSR outcomes match their expecta-

tions.While recognising effectiveness and equity expec-

tations ofCSR, we concentrate on the latter—a central

critique of CSR is thatit lacks any principle of justice to

guide the processof mediationbetweenstakeholders

(Koslowski 2000).

Stakeholder Claims and Agendas

Stakeholder often seek to influence an organisation’s CSR

philosophy and practice,with particulargroupssuch as

local and nationalcommunities,the media,government

and government agencies being seen as having a lesser or

episodic impact(e.g.Simmons 2008).Broaderconsider-

ation of stakeholder expectations is appropriate,as Archel

et al. (2011)found in an empiricalstudy ofCSR pro-

grammes in Spain,where stakeholder consultations often

resulted in a silencing of divergent voices from the domi-

nantCSR discourse.Thus,we have guardedly theorised

broad interpretations of the stakeholder expectations,each

of which has the capability to exert instrumental or moral

leverage on the focal organisation.While recognising that

notall stakeholders prioritise CSR,studies show thatan

increasing proportion regard an organisation’s stance on

CSR as a significant influence on their relationship with it

(Drews 2010).

Externalconstituenciesincludeinvestorswho want

profitable and socially responsible investmentthatalso

enhances corporate reputation;customers who seek prod-

ucts,services,and supply chainsthathave ‘green’cre-

dentials (Hess and Warren 2008);suppliers thatseek to

work in partnership with companies that respect fair trade

principles and do notabuse their monopoly power;gov-

ernment, regulators, and auditors seeking compliance with

legislation and codes ofconduct,internalmonitoring of

CSR practice,and transparency in CSR reporting;and

communities and pressure groups that expect companies

recognise the impactof theirCSR decision-making on

employmentand the environment.Employees constitute

the organisation’s internalstakeholders,with expectations

of demonstrated SR in its people managementpractices

and in treating otherstakeholders in line with employee

social values (Cheng and Ahmad 2010). Research suggest

that employeedecisionson retention,motivation,and

advocacy are influenced by this evaluation (Drews 2010).

The significance ofstakeholderexpectations is deter-

mined via an evaluation thatassessesthe legitimacy,

leverage, and urgency of stakeholder claims (Mitchell et a

1997).Managementdecisionson stakeholdersaliency

mean thatcertain stakeholderperspectives are acknowl-

edgedas requiringreconciliationwith thoseof other

stakeholder groups.We have followed Papasolomou et al.

(2005) in focusing on three main categories of stakeholder

expectation thatare likely to be recognised by organisa-

tions: investors,customers,and suppliers; employees; and

socialand environmentalgroups.The precise nature and

saliency ofstakeholderclaims—andtheir organisation

responses(Laudal,2011)—areinfluenced by thesize,

industrial sector and resources of the focal organisation, th

CSR-related expectationslikely to emanate from stake-

holder are described below.

The CSR System: Stakeholder Expectations

Our focus on stakeholder enables a more holistic view of

CSR. Key stakeholdergroupsanticipatethe beneficial

impact of CSR in the following ways. Investor expectations

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of CSR relate to itsanticipated impacton otherstake-

holders and the benefits that should accrue to the company

as a result,and are therefore similarto those ofsenior

management.Customerexpectations centre on the func-

tional, social, and emotional benefits of CSR in relation to

the products or services that they purchase (Becker-Olsen

et al. 2006). When these customer benefits are forthcoming,

they enhance brand attributes and value that are reflected in

greatercustomerattraction,retention,and trust—and in

new marketingopportunities.Employeesseek similar

benefits in an employment context, and studies suggest that

employee recognition of socially responsible people man-

agement practices are reflected in higher quality and lower

costrecruitment,and improved levels of staff motivation

and retention (Collierand Esteban 2007).Similarly,the

higherregard ofcommunities and environmentalistsfor

organisations they see as recognising theirsocietalobli-

gations is likely to resultin greater marketing opportuni-

ties, minimisingrisk, and as a meansof enhancing

company value (Petersen and Vredenburg 2009).Cumu-

latively, the expected benefits to organisations that succeed

in meeting CSR expectations of key stakeholder groups are

increased company revenue and profitability,lower costs,

easier access to finance,and a greater capability to inno-

vate.The CSR expectationsof noninvestorstakeholder

groups are now considered in greater detail.

As noted previously, customers anticipate-specific func-

tional, social, and emotional benefits or ‘value drivers’ from

theirpurchaseof CSR-enhanced productsand services

(Green and Peloza 2011).Functional value is the tangible

benefit the customer obtains from using such products and

services (for example,a hybrid car will deliver lower fuel

consumption).Socialvalue is the additionalbenefitcus-

tomers anticipate when others recognise that their purchase

accords with relevant social norms (e.g. anticipated positive

regard forinstalling solarpanels).Emotionalvalueis

achieved when the customer’s self-worth is enhanced by the

belief that their purchase will also benefit wider society or

the environment.Recentresearch suggests thatthe func-

tionalvalue componentis more influentialon customer

attitudes and behaviour than the indirect impact of social and

emotional benefits (Ferreira et al. 2010).

Employees expectsimilar CSR values to those of cus-

tomers.A recentstudy attests thatemployees seek func-

tional,economic,psychological,and ethical benefits from

their employing organisations (Simmons 2009). Functional

benefits are obtained if employment provides challenging,

stimulating and fulfilling work;economicbenefitsare

derivedfrom competitivecompensation;psychological

benefits accrue from employee involvementin a valued

work role;and ethicalbenefits are anticipated from the

equitabletreatmentemployeeshope to experience.

Cumulatively,provisionof thesebenefitsis seen as

indicative of a socially responsible employer,and the sig-

nificance of employee expectation of socially responsible

behaviour by their employer is supported by a recent stud

identifying this as a main driver of CSR practice (Mont and

Leire 2009).

Community and environmentalgroup expectations of

socially responsible practice arebroaderthan those of

investors, customers, and employees. Moreover, the diffus

or nonhuman nature of these stakeholders means that the

interestsmay be advanced by ‘stakewatchers’,such as

regulators,pressure groups,or activists who legislate or

lobby on their behalf (Fassin 2010).Some of their expec-

tations span community and environmental constituencies

and communityconcernrelatesto particularlocal or

nationalcontexts,while the focus of environmentalists is

unlikely to be constrained by national boundaries.

Both stakeholder groups seek organisation compliance

with relevantlegislationand regulation,timely, and

transparent disclosure of information, scope for their views

to be taken into accountin organisation decision-making,

and safe practice, for example regarding effluent and wast

disposal.However,community pressure groups are likely

to have more specific expectations of companies on issues

such as nonpredatory pricing, the availability of capital for

smallbusinesses,and a generalised expectation thatcom-

panies willavoid the extremes oftax avoidance by rec-

ognising fiscalobligations.In contrast,those representing

environmentalinterests expecttheir broader and transna-

tionalconcerns such as sustainable resource acquisition,

utilisation and disposal to be respected by the organisation

Community influence on socially responsible practice may

also take the form of media,a rating agency or regulator

attention that can act as significant drivers for organisatio

to enhance their CSR performance (Mont and Leire 2009;

Fassin 2010).

The CSR System: Philosophy and Strategy

Having identified the expectations of key stakeholders, we

now propose that the degree of salience accorded to these

groups willdrive the developmentof CSR-focused phi-

losophy and strategy.At a board level,such key decisions

such be taken mindfulof the disparate and potentially

competing demands of these groups.We argue thatsuch

decisions invite consideration of stakeholder perceptions o

organisationaljustice—meaningthat the organisation’s

treatment of different stakeholder groups is contingent on

the just distribution ofresourcesamong thosegroups

(distributivejustice),equitablemethodsof determining

these groups(proceduraljustice),and fairtreatmentof

groupmembers(interactionaljustice)(Erdoganet al.

2001).In the model,the equity ofCSR philosophy and

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

holders and the benefits that should accrue to the company

as a result,and are therefore similarto those ofsenior

management.Customerexpectations centre on the func-

tional, social, and emotional benefits of CSR in relation to

the products or services that they purchase (Becker-Olsen

et al. 2006). When these customer benefits are forthcoming,

they enhance brand attributes and value that are reflected in

greatercustomerattraction,retention,and trust—and in

new marketingopportunities.Employeesseek similar

benefits in an employment context, and studies suggest that

employee recognition of socially responsible people man-

agement practices are reflected in higher quality and lower

costrecruitment,and improved levels of staff motivation

and retention (Collierand Esteban 2007).Similarly,the

higherregard ofcommunities and environmentalistsfor

organisations they see as recognising theirsocietalobli-

gations is likely to resultin greater marketing opportuni-

ties, minimisingrisk, and as a meansof enhancing

company value (Petersen and Vredenburg 2009).Cumu-

latively, the expected benefits to organisations that succeed

in meeting CSR expectations of key stakeholder groups are

increased company revenue and profitability,lower costs,

easier access to finance,and a greater capability to inno-

vate.The CSR expectationsof noninvestorstakeholder

groups are now considered in greater detail.

As noted previously, customers anticipate-specific func-

tional, social, and emotional benefits or ‘value drivers’ from

theirpurchaseof CSR-enhanced productsand services

(Green and Peloza 2011).Functional value is the tangible

benefit the customer obtains from using such products and

services (for example,a hybrid car will deliver lower fuel

consumption).Socialvalue is the additionalbenefitcus-

tomers anticipate when others recognise that their purchase

accords with relevant social norms (e.g. anticipated positive

regard forinstalling solarpanels).Emotionalvalueis

achieved when the customer’s self-worth is enhanced by the

belief that their purchase will also benefit wider society or

the environment.Recentresearch suggests thatthe func-

tionalvalue componentis more influentialon customer

attitudes and behaviour than the indirect impact of social and

emotional benefits (Ferreira et al. 2010).

Employees expectsimilar CSR values to those of cus-

tomers.A recentstudy attests thatemployees seek func-

tional,economic,psychological,and ethical benefits from

their employing organisations (Simmons 2009). Functional

benefits are obtained if employment provides challenging,

stimulating and fulfilling work;economicbenefitsare

derivedfrom competitivecompensation;psychological

benefits accrue from employee involvementin a valued

work role;and ethicalbenefits are anticipated from the

equitabletreatmentemployeeshope to experience.

Cumulatively,provisionof thesebenefitsis seen as

indicative of a socially responsible employer,and the sig-

nificance of employee expectation of socially responsible

behaviour by their employer is supported by a recent stud

identifying this as a main driver of CSR practice (Mont and

Leire 2009).

Community and environmentalgroup expectations of

socially responsible practice arebroaderthan those of

investors, customers, and employees. Moreover, the diffus

or nonhuman nature of these stakeholders means that the

interestsmay be advanced by ‘stakewatchers’,such as

regulators,pressure groups,or activists who legislate or

lobby on their behalf (Fassin 2010).Some of their expec-

tations span community and environmental constituencies

and communityconcernrelatesto particularlocal or

nationalcontexts,while the focus of environmentalists is

unlikely to be constrained by national boundaries.

Both stakeholder groups seek organisation compliance

with relevantlegislationand regulation,timely, and

transparent disclosure of information, scope for their views

to be taken into accountin organisation decision-making,

and safe practice, for example regarding effluent and wast

disposal.However,community pressure groups are likely

to have more specific expectations of companies on issues

such as nonpredatory pricing, the availability of capital for

smallbusinesses,and a generalised expectation thatcom-

panies willavoid the extremes oftax avoidance by rec-

ognising fiscalobligations.In contrast,those representing

environmentalinterests expecttheir broader and transna-

tionalconcerns such as sustainable resource acquisition,

utilisation and disposal to be respected by the organisation

Community influence on socially responsible practice may

also take the form of media,a rating agency or regulator

attention that can act as significant drivers for organisatio

to enhance their CSR performance (Mont and Leire 2009;

Fassin 2010).

The CSR System: Philosophy and Strategy

Having identified the expectations of key stakeholders, we

now propose that the degree of salience accorded to these

groups willdrive the developmentof CSR-focused phi-

losophy and strategy.At a board level,such key decisions

such be taken mindfulof the disparate and potentially

competing demands of these groups.We argue thatsuch

decisions invite consideration of stakeholder perceptions o

organisationaljustice—meaningthat the organisation’s

treatment of different stakeholder groups is contingent on

the just distribution ofresourcesamong thosegroups

(distributivejustice),equitablemethodsof determining

these groups(proceduraljustice),and fairtreatmentof

groupmembers(interactionaljustice)(Erdoganet al.

2001).In the model,the equity ofCSR philosophy and

C. Mason,J. Simmons

123

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

strategy isassessed by stakeholderperceptionsof their

procedural justice.

The CSR System: Process and Operations

More and more companies claim to be ‘doing the right

thing’ in relation to CSR and corporate governance, yet for

many the impactis restricted to an espoused philosophy

that has limited influence on business operations (Roberts

2001).Infusion of CSR into allaspects of business oper-

ationsrequiresthe integration ofhard wiring and soft

wiring approaches (de Wit et al.2006).

Hard wiring is grounding CSR in organisation systems

and protocols. Examples of these include the criteria used for

employee selection,promotion,and reward; promulgation

of codes of ethics and codes of conduct;the use of CSR

parameters in new productdevelopment;socialdue dili-

gence assessment of business projects; and regular reporting

on the socialand environmentalimpactof the business

(Greenwood 2001).Softwiring relates to the infusion of

CSR into cultural aspects of the business (de Wit et al. 2006).

Examples include senior managers acting as exemplars of

socially responsible business practice;sustainability as a

core cultural value in ‘the way things are done around here’;

supportfor CSR initiativesthatgo beyond the formal

boundaries of the organisation, facilitating socially respon-

sible supplier and logistics practices; a willingness to choice

influence orchoice editcustomertastes;and the use of

opinion surveys for periodic monitoring of staff attitudes

(Rodrigo and Arenas 2008).

The CSR System: Outcomes and Implications

Performance measurementhas been defined as ‘the com-

parison ofresultsagainstexpectationswith the implied

objective oflearning to do better’(Rouse and Putterill

2003, p. 275). This broaderperspectiveincorporates

financialand nonfinancialaspectsof performance,and

incorporates stakeholder expectations in the evaluation of

performance measures(Rouse and Putterill2003).Four

key perspectives on CSR outcomes are considered here:

investors,customers and suppliers,employees,and com-

munity and environmentgroups.Even thoughthese

stakeholder evaluation domains are considered separately,

it is recognised thatthere is significantinterrelationship

between them.Ethicalconcernsaboutbusinesspractice

involve a basic dislocation arising out of phenomenological

beliefsand experiencesthat‘thingsare out of place’

(Beverungen and Case 2011). This multi-source evaluation

represents ‘‘a broader view of corporate accountability in

which there are as many bottom lines as there are stake-

holders’’ (Pava 2011,p. 53).

The evaluation processes and outcomes are now consid

ered in more detail.Investors and customers seek confir-

mation of the functional,emotional,and social benefits of

CSR-related purchases,while both customer and supplier

commitment is influenced by whether the company is view

as evidencing sustainable manufacturing, service provision

and supply chains.The positive regard of customers and

suppliers is manifested in increased sales, loyalty, coopera

tion, and advocacy (Cuganesan 2006). Employees evaluat

the ethicality of the people management practices that th

experience (Collierand Esteban 2007),while employee

evaluation isalso influenced by theirperception ofthe

impactof the organisation’s wider CSR practice on cus-

tomers,communities,and the environment(Rupp etal.

2006).As noted above,favourable employee evaluation

resultsin enhanced attraction,loyalty,and commitment

(Davies and Chun 2002).Community and environmental

group evaluation isbased on the company’sperceived

alignment with industry, national or international standard

whether itembodies responsible and sustainable business

practice; the timeliness, transparency, and responsiveness

its reporting practices; and whether the organisation is con

sidered to be a ‘good neighbour’ by communities that coe

alongside it. Positive community and pressure group evalu

ation enhances organisation reputation and ethical capital

and the equity of CSR outcomes is assessed by stakeholde

perceptions of their distributive justice.

The CSR System: Company Evaluation and Reporting

We suggestthatresponsible organisationswill draw on

stakeholder perspectives in their cumulative evaluation of

CSR, and utilise these to assess CSR’s influence on the

organisation’sefficiency,effectiveness,equity,environ-

mental impact, and external reputation. Using these in tur

the efficiency ofCSR can be assessed by the extentto

which CSR principles and standards are incorporated into

organisation controland performance managementsys-

tems; CSR effectiveness by an overall cost-benefit analysis

of its organisational impact over an appropriate timescale;

CSR equity by utilising stakeholderperceptionsof the

justiceof CSR processes,interactions,and outcomes;

CSR’s environmental impact by the level of sustainability

in the organisation’s resource acquisition,utilisation and

disposal;and CSR’s externalreputation influence by the

extent to which its ethical capital has been enhanced acro

stakeholder groups.

An organisation’s obligations in relation to CSR remain

pertinent,comprising the dissemination of information to

and dialogue with key stakeholder groups.Dissemination

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

procedural justice.

The CSR System: Process and Operations

More and more companies claim to be ‘doing the right

thing’ in relation to CSR and corporate governance, yet for

many the impactis restricted to an espoused philosophy

that has limited influence on business operations (Roberts

2001).Infusion of CSR into allaspects of business oper-

ationsrequiresthe integration ofhard wiring and soft

wiring approaches (de Wit et al.2006).

Hard wiring is grounding CSR in organisation systems

and protocols. Examples of these include the criteria used for

employee selection,promotion,and reward; promulgation

of codes of ethics and codes of conduct;the use of CSR

parameters in new productdevelopment;socialdue dili-

gence assessment of business projects; and regular reporting

on the socialand environmentalimpactof the business

(Greenwood 2001).Softwiring relates to the infusion of

CSR into cultural aspects of the business (de Wit et al. 2006).

Examples include senior managers acting as exemplars of

socially responsible business practice;sustainability as a

core cultural value in ‘the way things are done around here’;

supportfor CSR initiativesthatgo beyond the formal

boundaries of the organisation, facilitating socially respon-

sible supplier and logistics practices; a willingness to choice

influence orchoice editcustomertastes;and the use of

opinion surveys for periodic monitoring of staff attitudes

(Rodrigo and Arenas 2008).

The CSR System: Outcomes and Implications

Performance measurementhas been defined as ‘the com-

parison ofresultsagainstexpectationswith the implied

objective oflearning to do better’(Rouse and Putterill

2003, p. 275). This broaderperspectiveincorporates

financialand nonfinancialaspectsof performance,and

incorporates stakeholder expectations in the evaluation of

performance measures(Rouse and Putterill2003).Four

key perspectives on CSR outcomes are considered here:

investors,customers and suppliers,employees,and com-

munity and environmentgroups.Even thoughthese

stakeholder evaluation domains are considered separately,

it is recognised thatthere is significantinterrelationship

between them.Ethicalconcernsaboutbusinesspractice

involve a basic dislocation arising out of phenomenological

beliefsand experiencesthat‘thingsare out of place’

(Beverungen and Case 2011). This multi-source evaluation

represents ‘‘a broader view of corporate accountability in

which there are as many bottom lines as there are stake-

holders’’ (Pava 2011,p. 53).

The evaluation processes and outcomes are now consid

ered in more detail.Investors and customers seek confir-

mation of the functional,emotional,and social benefits of

CSR-related purchases,while both customer and supplier

commitment is influenced by whether the company is view

as evidencing sustainable manufacturing, service provision

and supply chains.The positive regard of customers and

suppliers is manifested in increased sales, loyalty, coopera

tion, and advocacy (Cuganesan 2006). Employees evaluat

the ethicality of the people management practices that th

experience (Collierand Esteban 2007),while employee

evaluation isalso influenced by theirperception ofthe

impactof the organisation’s wider CSR practice on cus-

tomers,communities,and the environment(Rupp etal.

2006).As noted above,favourable employee evaluation

resultsin enhanced attraction,loyalty,and commitment

(Davies and Chun 2002).Community and environmental

group evaluation isbased on the company’sperceived

alignment with industry, national or international standard

whether itembodies responsible and sustainable business

practice; the timeliness, transparency, and responsiveness

its reporting practices; and whether the organisation is con

sidered to be a ‘good neighbour’ by communities that coe

alongside it. Positive community and pressure group evalu

ation enhances organisation reputation and ethical capital

and the equity of CSR outcomes is assessed by stakeholde

perceptions of their distributive justice.

The CSR System: Company Evaluation and Reporting

We suggestthatresponsible organisationswill draw on

stakeholder perspectives in their cumulative evaluation of

CSR, and utilise these to assess CSR’s influence on the

organisation’sefficiency,effectiveness,equity,environ-

mental impact, and external reputation. Using these in tur

the efficiency ofCSR can be assessed by the extentto

which CSR principles and standards are incorporated into

organisation controland performance managementsys-

tems; CSR effectiveness by an overall cost-benefit analysis

of its organisational impact over an appropriate timescale;

CSR equity by utilising stakeholderperceptionsof the

justiceof CSR processes,interactions,and outcomes;

CSR’s environmental impact by the level of sustainability

in the organisation’s resource acquisition,utilisation and

disposal;and CSR’s externalreputation influence by the

extent to which its ethical capital has been enhanced acro

stakeholder groups.

An organisation’s obligations in relation to CSR remain

pertinent,comprising the dissemination of information to

and dialogue with key stakeholder groups.Dissemination

A Stakeholder Systems Approach

123

involves reporting back to stakeholder constituencies via a

CSR version of the Balanced Scorecard(Kaplanand

Norton 1992). Dialogue is via organisation commitment to

involve stakeholders in the actions itintends to take as a

result of evaluating CSR.

Conclusion

Throughoutthis paper,we have proposed a conceptual

modelthatrepresentsa rationale forand a method of

embedding CSR in corporate governance.Adoption of a

stakeholder perspective identifies the limitations of current

CSR approaches, recognises the need to incorporate effec-

tiveness and equity assessments of CSR impact, and delin-

eates key stakeholderconstituencies and the factors that

determine their salience.The CSR-related expectations of

four stakeholder constituencies—investors,customers and

suppliers,employees,and community and environmental

groups—have been identified,and we contend thatthese

drive the development of CSR philosophy and strategy.

The paper’ssystemicapproach linksemergentCSR

strategy to its enactmentthrough CSR processes,which

then resultin a range ofCSR outcomes.Organisational

justice concepts are deployed to evaluate stakeholder per-

ceptions of system equity at each stage—with procedural,

interactional,and distributivejusticerelatingto CSR

strategy,process,and outcomes,respectively.We contend

that stakeholder groups compare CSR outcomes with their

expectations,and thatthese assessments have attitudinal

and behaviouralimplications.Subsequentorganisation

evaluation of CSR should draw on the same of its stake-

holders,and the resultantassessmentwill inform ofany

required revision to its CSR stance.Organisationalobli-

gations in relation to CSR continue via an acceptance of

the need to report back to stakeholders on CSR outcomes,

togetherwith a commitmentto remain in dialogue with

them on actions that the organisation may take as a result.

The significance ofour stakeholdersystems modelis

that it representsa formalised processof stakeholder

engagement that enables organisations to take stakeholder

views into accountwhen evaluating theirCSR-related

activities.Most organisations interactwith a network of

stakeholders to acquire resources and obtain legitimacy.

However, researchers have challenged the assumption that

stakeholder engagement is a responsible practice, as it may

or may not involve a moral dimension (Greenwood 2007),

and may or may not facilitate sustainability.

These concerns raise questions about the criteria for the

morally acceptable engagementof stakeholders(Noland

and Phillips 2010), and how to assess the extent to which a

business is socially responsible. Noland and Phillips (2010)

attested thatthe social and environmentalimpactthat

business organisations have on society implies thatthey

engage with stakeholders who have a legitimate stake in

the business.They thereforecompared two modesof

stakeholderengagementthatthey termed ‘Habermasian’

and ‘EthicalStrategist’.They believed thatwhile the

Habermasian approachis purerin a moral sense,its

requirementthatCSR decision-makersprioritise ethical

purity overcostand alignmentwith strategy rendersit

impracticalin a business context.Moreover,ethicalstrat-

egistsarguethatthe Habermasian distinction between

morality and strategy is misguided.

Conceivably a good strategy necessarily incorporates

moralconcerns,as the sustainability ofthe organisation

requires the creation of relevant value for all stakeholders

So how then can an organisation demonstrate that it creat

CSR value for its stakeholder constituencies? We contend

that stakeholderperceptionsof the ethicalityof CSR

strategy,process,and outcomeswhich ourstakeholder

systems modelprovides,are measures of corporate social

performance.Moreover,if an organisation modifiesits

CSR philosophy and practice as a resultof such stake-

holderfeedback,this evidences the leverage thatethical

stakeholder engagement can exert.

Our stakeholdersystemsmodelon CSR is also sup-

ported by two furthercritiquesof the prevailing CSR

orthodoxy.Rasche (2010) proposed a method of incorpo-

rating SR into organisations through a multi-stakeholder

consultation process that is underpinned by core values of

stakeholderengagement:inclusivity,materiality,and

responsiveness.Inclusivityrequiresrecognitionof an

organisation’saccountability to stakeholders—including

those who impact on it and those who are impacted by it.

Materiality isacceptance ofthe need to determine the

significanceof CSR-related issuesto stakeholders,by

identifying theirexpectations,and perspectives.Respon-

siveness is a commitment of accountability to stakeholder

in relation to CSR policy,process,and performance,as

well as through transparent,timely and dialogic commu-

nication processes. Scherer and Palazzo (2007) questioned

the adequacy of dominant approaches to CSR, by claiming

thatthey failto consider thatthe genesis,processes,and

consequences of CSR initiatives are shaped and delivered

by politicalprocesses.They attested thatthe descriptive

approach of most CSR fails to integrate more critical per-

spectives,which reinforces ‘business as usual’ stances of

researchersand practitioners.Instead they arguefor a