RCM301: Corporate Social Responsibility in a Global Context Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/19

|24

|13266

|44

Report

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the critical topic of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) within a global framework. It meticulously examines the escalating prominence of CSR, scrutinizing its various definitions and core characteristics. The analysis extends to exploring CSR's application across diverse organizational and national contexts, providing a comprehensive understanding of its multifaceted nature. The assignment also investigates the evolution of CSR from its early roots in addressing worker conditions and philanthropy to its current, more coherent and professional approach, which is now central to business management. The report highlights the emergence of a CSR 'movement' with dedicated consultancies, standards, and interest groups, contributing to a worldwide network of CSR practitioners. It references key definitions from various organizations like the International Labour Organization and General Electric, and explores differing perspectives on CSR, from Davis's focus on responsibilities beyond economic requirements to Carroll's broader inclusion of economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations. The assignment aims to provide a coherent account of CSR, navigating through the vast and often contested literature on the subject.

C h a p t e r 1

Corporate social responsibility:

in a global context

IN THIS CHAPTER WE WILL:

● Examine the rise to prominence of corporate social responsibility

● Analyze different definitions of corporate social responsibility

● Outline six core characteristics of corporate social responsibility

● Explore corporate social responsibility in different organizational contexts

● Explore corporate social responsibility in different national contexts

● Explain the approach to corporate social responsibility adopted in the rest of

the book

Introduction: the recent rise of CSR

The role of corporations in society is clearly high on the agenda. Hardly a day goes

by without media reports on corporate misbehaviour and scandals or, more positively,

on contributions from business to wider society. A quick stroll to the local cinema

and films such as Inside Job, Margin Call, and Wall Street 2, reflect a growing

interest among the public in the impact of corporations on contemporary life.

Corporations are clearly taking up this challenge. This began with ‘the usual

suspects’ such as companies in the oil, chemical, and tobacco industries. As a result

of media pressure, major disasters, and sometimes governmental regulation, these

companies realized that propping up oppressive regimes, being implicated in human

rights violations, polluting the environment, or misinforming and deliberately harming

their customers, just to give a few examples, were practices that had to be recon-

sidered if they wanted to survive and prosper. Today, however, there is virtually no

industry, market, or business type that has not experienced increasing demands to

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 3

Corporate social responsibility:

in a global context

IN THIS CHAPTER WE WILL:

● Examine the rise to prominence of corporate social responsibility

● Analyze different definitions of corporate social responsibility

● Outline six core characteristics of corporate social responsibility

● Explore corporate social responsibility in different organizational contexts

● Explore corporate social responsibility in different national contexts

● Explain the approach to corporate social responsibility adopted in the rest of

the book

Introduction: the recent rise of CSR

The role of corporations in society is clearly high on the agenda. Hardly a day goes

by without media reports on corporate misbehaviour and scandals or, more positively,

on contributions from business to wider society. A quick stroll to the local cinema

and films such as Inside Job, Margin Call, and Wall Street 2, reflect a growing

interest among the public in the impact of corporations on contemporary life.

Corporations are clearly taking up this challenge. This began with ‘the usual

suspects’ such as companies in the oil, chemical, and tobacco industries. As a result

of media pressure, major disasters, and sometimes governmental regulation, these

companies realized that propping up oppressive regimes, being implicated in human

rights violations, polluting the environment, or misinforming and deliberately harming

their customers, just to give a few examples, were practices that had to be recon-

sidered if they wanted to survive and prosper. Today, however, there is virtually no

industry, market, or business type that has not experienced increasing demands to

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

legitimate its practices to society at large. For instance, banking, retailing, tourism,

food and beverages, entertainment, and healthcare industries – for long considered

to be fairly ‘clean’ and uncontroversial – now all face increasing expectations that

they institute more responsible practices.

In the context of the global economic crisis, which began in 2008 and rever-

berated for a number of years thereafter, questions regarding the responsibilities of

business have moved still further to the fore of the media, political and public interest

The focus here has been on financial institutions primarily, whose imprudent practice

are largely held to blame for igniting a wave of economic recession. As governments

bailed out failing businesses and popular protests such as ‘Occupy Wall Street’

spread globally, companies in the financial sector faced a new era of scrutiny of their

values, goals, and purpose.

Companies have responded to this agenda by advocating what is now a

common term in business: corporate social responsibility. More often known simply

as CSR, the concept of corporate social responsibility is a management idea that

has risen to unprecedented popularity throughout the global business community

during the last decades. Most large companies, and even some smaller ones, now

feature CSR reports, managers, departments, or at least CSR projects, and the

subject is increasingly promoted as a core area of management, next to marketing,

accounting, or finance.

If we take a closer look at the recent rise of CSR, some might well argue that

this ‘new’ management idea is little more than a recycled fashion, or as the old saying

goes, ‘old wine in new bottles’. And, in fact, one could certainly suggest that some

of the practices that fall under the label of CSR have indeed been relevant business

issues at least since the Industrial Revolution. Ensuring humane working conditions,

providing decent housing or healthcare, and donating to charity are activities that

many of the early industrialists in Europe and the US were involved in – without

necessarily shouting out about them in annual reports, let alone calling them CSR.

The involvement of business in social issues is not the prerogative of the West. In

India, for example, companies such as Tata can pride themselves on more than

100 years of responsible business practices, including far-reaching philanthropic

activities and community involvement (Elankumaran et al, 2005). What we discover

then in the area of CSR is that while many of the individual policies, practices, and

programmes are not new as such, corporations today are addressing their role in

society far more coherently, comprehensively, and professionally – an approach that

is contemporarily summarized by CSR.

As well as the rise to prominence of CSR in particular companies, we have also

witnessed the emergence of something like a CSR ‘movement’. There has been a

mushrooming of dedicated CSR consultancies, all of which see a business oppor-

tunity in the growing popularity of the concept. At the same time, we are witnessing

a burgeoning number of CSR standards, watchdogs, auditors, and certifiers aiming

at institutionalizing and harmonizing CSR practices globally. More and more industry

associations and interest groups have been set up in order to coordinate and create

synergies among individual business approaches to CSR. Meanwhile, a growing

number of dedicated magazines, newsletters, social media and websites not only

4 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 4

food and beverages, entertainment, and healthcare industries – for long considered

to be fairly ‘clean’ and uncontroversial – now all face increasing expectations that

they institute more responsible practices.

In the context of the global economic crisis, which began in 2008 and rever-

berated for a number of years thereafter, questions regarding the responsibilities of

business have moved still further to the fore of the media, political and public interest

The focus here has been on financial institutions primarily, whose imprudent practice

are largely held to blame for igniting a wave of economic recession. As governments

bailed out failing businesses and popular protests such as ‘Occupy Wall Street’

spread globally, companies in the financial sector faced a new era of scrutiny of their

values, goals, and purpose.

Companies have responded to this agenda by advocating what is now a

common term in business: corporate social responsibility. More often known simply

as CSR, the concept of corporate social responsibility is a management idea that

has risen to unprecedented popularity throughout the global business community

during the last decades. Most large companies, and even some smaller ones, now

feature CSR reports, managers, departments, or at least CSR projects, and the

subject is increasingly promoted as a core area of management, next to marketing,

accounting, or finance.

If we take a closer look at the recent rise of CSR, some might well argue that

this ‘new’ management idea is little more than a recycled fashion, or as the old saying

goes, ‘old wine in new bottles’. And, in fact, one could certainly suggest that some

of the practices that fall under the label of CSR have indeed been relevant business

issues at least since the Industrial Revolution. Ensuring humane working conditions,

providing decent housing or healthcare, and donating to charity are activities that

many of the early industrialists in Europe and the US were involved in – without

necessarily shouting out about them in annual reports, let alone calling them CSR.

The involvement of business in social issues is not the prerogative of the West. In

India, for example, companies such as Tata can pride themselves on more than

100 years of responsible business practices, including far-reaching philanthropic

activities and community involvement (Elankumaran et al, 2005). What we discover

then in the area of CSR is that while many of the individual policies, practices, and

programmes are not new as such, corporations today are addressing their role in

society far more coherently, comprehensively, and professionally – an approach that

is contemporarily summarized by CSR.

As well as the rise to prominence of CSR in particular companies, we have also

witnessed the emergence of something like a CSR ‘movement’. There has been a

mushrooming of dedicated CSR consultancies, all of which see a business oppor-

tunity in the growing popularity of the concept. At the same time, we are witnessing

a burgeoning number of CSR standards, watchdogs, auditors, and certifiers aiming

at institutionalizing and harmonizing CSR practices globally. More and more industry

associations and interest groups have been set up in order to coordinate and create

synergies among individual business approaches to CSR. Meanwhile, a growing

number of dedicated magazines, newsletters, social media and websites not only

4 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 4

contribute to providing an identity to CSR as a management concept, but also help

to build a worldwide network of CSR practitioners, academics, and activists.

Defining CSR: navigating through the jungle of definitions

In the context of such an inexorable rise to prominence of CSR, the literature on the

subject, both academic and practitioner, is understandably large and expanding.

There are now thousands of articles and reports on CSR from academics,

corporations, consultancies, the media, NGOs, and government departments; there

are innumerable conferences, books, journals, and magazines on the subject; and

last, but not least, there are literally millions of web-based formal and social media

contributions dealing with the topic from every conceivable interest group with a

stake in the debate.

How then to best make sense of this vast literature so as to construct a coherent

account of what CSR actually is? After all, few subjects in management arouse as

much controversy and contestation as CSR. For this reason, definitions of CSR

abound, and there are as many definitions of CSR as there are disagreements over

the appropriate role of the corporation in society. Hence there remains a lack of

consensus on a definition for CSR (Lindgreen & Swaen, 2010). The CSR page on

Wikipedia, the online encyclopaedia, has been in more or less permanent dispute

since 2007 (Ethical Performance, 2007) and continues to be challenged for its

neutrality.

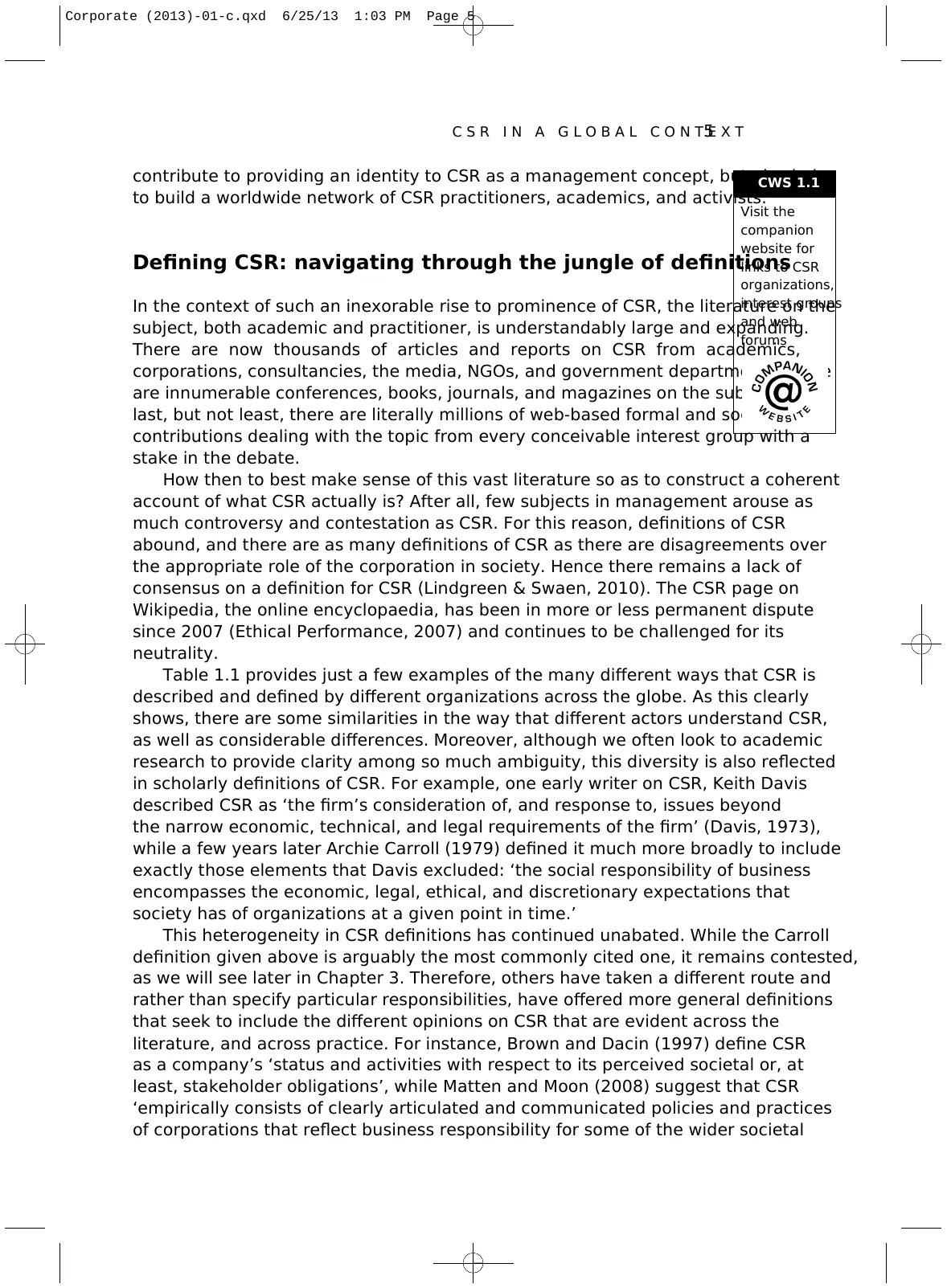

Table 1.1 provides just a few examples of the many different ways that CSR is

described and defined by different organizations across the globe. As this clearly

shows, there are some similarities in the way that different actors understand CSR,

as well as considerable differences. Moreover, although we often look to academic

research to provide clarity among so much ambiguity, this diversity is also reflected

in scholarly definitions of CSR. For example, one early writer on CSR, Keith Davis

described CSR as ‘the firm’s consideration of, and response to, issues beyond

the narrow economic, technical, and legal requirements of the firm’ (Davis, 1973),

while a few years later Archie Carroll (1979) defined it much more broadly to include

exactly those elements that Davis excluded: ‘the social responsibility of business

encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that

society has of organizations at a given point in time.’

This heterogeneity in CSR definitions has continued unabated. While the Carroll

definition given above is arguably the most commonly cited one, it remains contested,

as we will see later in Chapter 3. Therefore, others have taken a different route and

rather than specify particular responsibilities, have offered more general definitions

that seek to include the different opinions on CSR that are evident across the

literature, and across practice. For instance, Brown and Dacin (1997) define CSR

as a company’s ‘status and activities with respect to its perceived societal or, at

least, stakeholder obligations’, while Matten and Moon (2008) suggest that CSR

‘empirically consists of clearly articulated and communicated policies and practices

of corporations that reflect business responsibility for some of the wider societal

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Visit the

companion

website for

links to CSR

organizations,

interest groups

and web

forums

CWS 1.1

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 5

to build a worldwide network of CSR practitioners, academics, and activists.

Defining CSR: navigating through the jungle of definitions

In the context of such an inexorable rise to prominence of CSR, the literature on the

subject, both academic and practitioner, is understandably large and expanding.

There are now thousands of articles and reports on CSR from academics,

corporations, consultancies, the media, NGOs, and government departments; there

are innumerable conferences, books, journals, and magazines on the subject; and

last, but not least, there are literally millions of web-based formal and social media

contributions dealing with the topic from every conceivable interest group with a

stake in the debate.

How then to best make sense of this vast literature so as to construct a coherent

account of what CSR actually is? After all, few subjects in management arouse as

much controversy and contestation as CSR. For this reason, definitions of CSR

abound, and there are as many definitions of CSR as there are disagreements over

the appropriate role of the corporation in society. Hence there remains a lack of

consensus on a definition for CSR (Lindgreen & Swaen, 2010). The CSR page on

Wikipedia, the online encyclopaedia, has been in more or less permanent dispute

since 2007 (Ethical Performance, 2007) and continues to be challenged for its

neutrality.

Table 1.1 provides just a few examples of the many different ways that CSR is

described and defined by different organizations across the globe. As this clearly

shows, there are some similarities in the way that different actors understand CSR,

as well as considerable differences. Moreover, although we often look to academic

research to provide clarity among so much ambiguity, this diversity is also reflected

in scholarly definitions of CSR. For example, one early writer on CSR, Keith Davis

described CSR as ‘the firm’s consideration of, and response to, issues beyond

the narrow economic, technical, and legal requirements of the firm’ (Davis, 1973),

while a few years later Archie Carroll (1979) defined it much more broadly to include

exactly those elements that Davis excluded: ‘the social responsibility of business

encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that

society has of organizations at a given point in time.’

This heterogeneity in CSR definitions has continued unabated. While the Carroll

definition given above is arguably the most commonly cited one, it remains contested,

as we will see later in Chapter 3. Therefore, others have taken a different route and

rather than specify particular responsibilities, have offered more general definitions

that seek to include the different opinions on CSR that are evident across the

literature, and across practice. For instance, Brown and Dacin (1997) define CSR

as a company’s ‘status and activities with respect to its perceived societal or, at

least, stakeholder obligations’, while Matten and Moon (2008) suggest that CSR

‘empirically consists of clearly articulated and communicated policies and practices

of corporations that reflect business responsibility for some of the wider societal

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Visit the

companion

website for

links to CSR

organizations,

interest groups

and web

forums

CWS 1.1

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

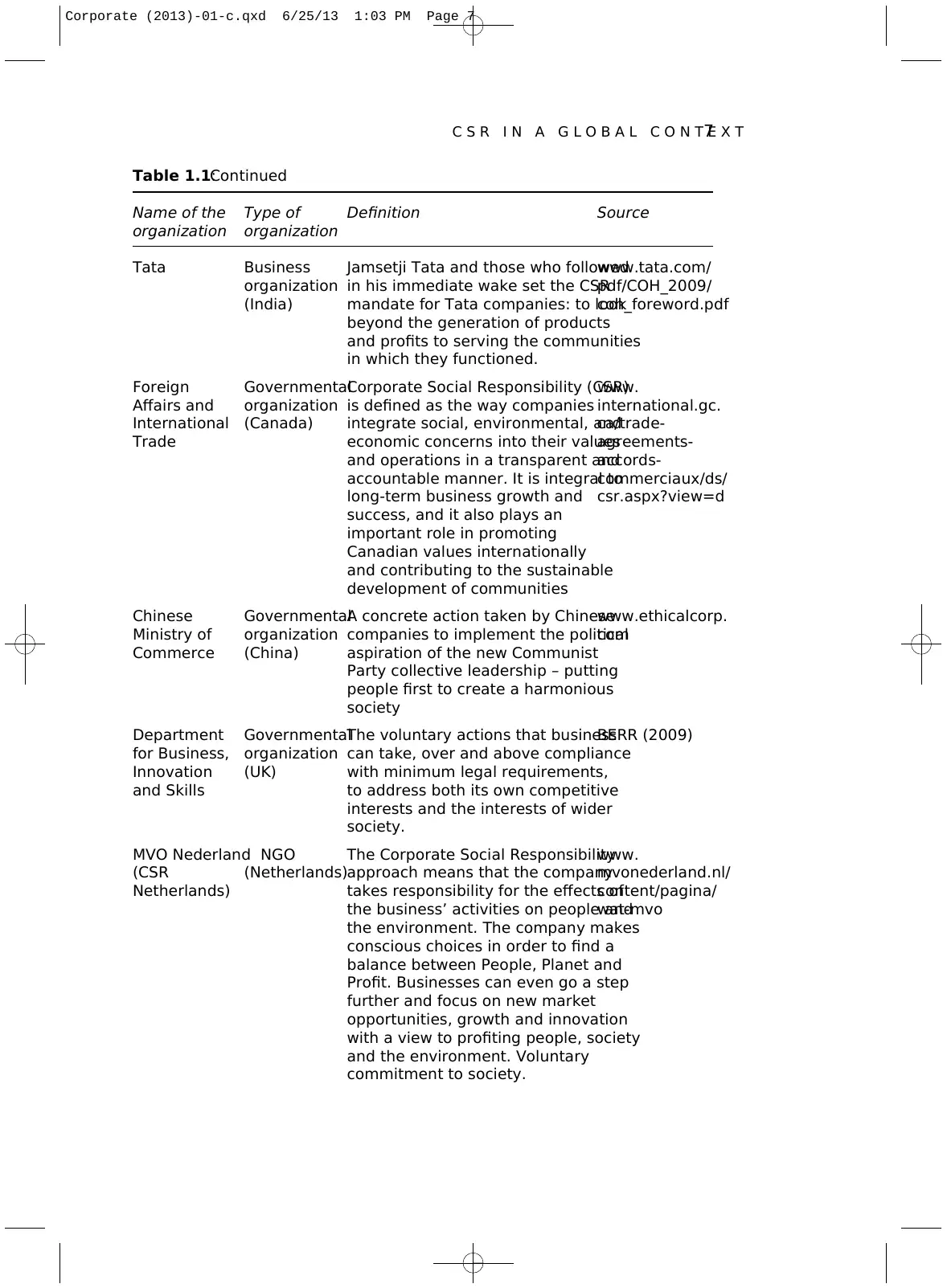

Table 1.1:CSR definitions

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

International Non- CSR as a way in which enterpriseswww.ilo.org/

Labour governmentalgive consideration to the impact ofwcmsp5/groups/

Organization organization their operations on society and public/---ed_

(international)affirm their principles and valuesemp/---emp_

both in their own internal methodsent/---multi/

and processes and in their documents/

interaction with other actors. publication/wcms

_116336.pdf

Corporate NGO Corporate Social Responsibility CORE (2011)

Responsibility coalition (CSR) has been promoted by

Coalition (UK) business as a way of realising its

(CORE) ‘social responsibilities’ beyond

making a profit for its shareholders.

In contrast to this view, NGOs and

trade unions tend to dismiss CSR as

a public relations tool at best, and at

worst a means for corporations to

avoid the creation of regulatory and

legal mechanisms as a means of

ensuring that they adhere to

acceptable standards of conduct.

Grameen Social Businesses are identifying themselves Yunus & Weber

Bank enterprise with the movement for Corporate(2009)

(Bangladesh) Social Responsibility (CSR), and

are trying to do good to the people

while conducting their business.

But profit-making still remains

their main goal, by definition.

Though they like to talk about

triple bottom lines of financial,

social, and environmental benefits,

ultimately only one bottom line

calls the shot: financial profit.

General Business GE businesses depend on the www.ge

Electric organization infrastructure, skills and institutionscitizenship.com/

(US) of stable, prosperous societies andabout-citizenship/

healthy environments. To succeed as

a global business, we need to be a

part of building these societies where

we operate. We do this through the

products and services we create, the

way we work with employees,

customers, suppliers and investors,

the public policies we advocate and

the philanthropic partnerships we

support.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Table 1.1:CSR definitions

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

International Non- CSR as a way in which enterpriseswww.ilo.org/

Labour governmentalgive consideration to the impact ofwcmsp5/groups/

Organization organization their operations on society and public/---ed_

(international)affirm their principles and valuesemp/---emp_

both in their own internal methodsent/---multi/

and processes and in their documents/

interaction with other actors. publication/wcms

_116336.pdf

Corporate NGO Corporate Social Responsibility CORE (2011)

Responsibility coalition (CSR) has been promoted by

Coalition (UK) business as a way of realising its

(CORE) ‘social responsibilities’ beyond

making a profit for its shareholders.

In contrast to this view, NGOs and

trade unions tend to dismiss CSR as

a public relations tool at best, and at

worst a means for corporations to

avoid the creation of regulatory and

legal mechanisms as a means of

ensuring that they adhere to

acceptable standards of conduct.

Grameen Social Businesses are identifying themselves Yunus & Weber

Bank enterprise with the movement for Corporate(2009)

(Bangladesh) Social Responsibility (CSR), and

are trying to do good to the people

while conducting their business.

But profit-making still remains

their main goal, by definition.

Though they like to talk about

triple bottom lines of financial,

social, and environmental benefits,

ultimately only one bottom line

calls the shot: financial profit.

General Business GE businesses depend on the www.ge

Electric organization infrastructure, skills and institutionscitizenship.com/

(US) of stable, prosperous societies andabout-citizenship/

healthy environments. To succeed as

a global business, we need to be a

part of building these societies where

we operate. We do this through the

products and services we create, the

way we work with employees,

customers, suppliers and investors,

the public policies we advocate and

the philanthropic partnerships we

support.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

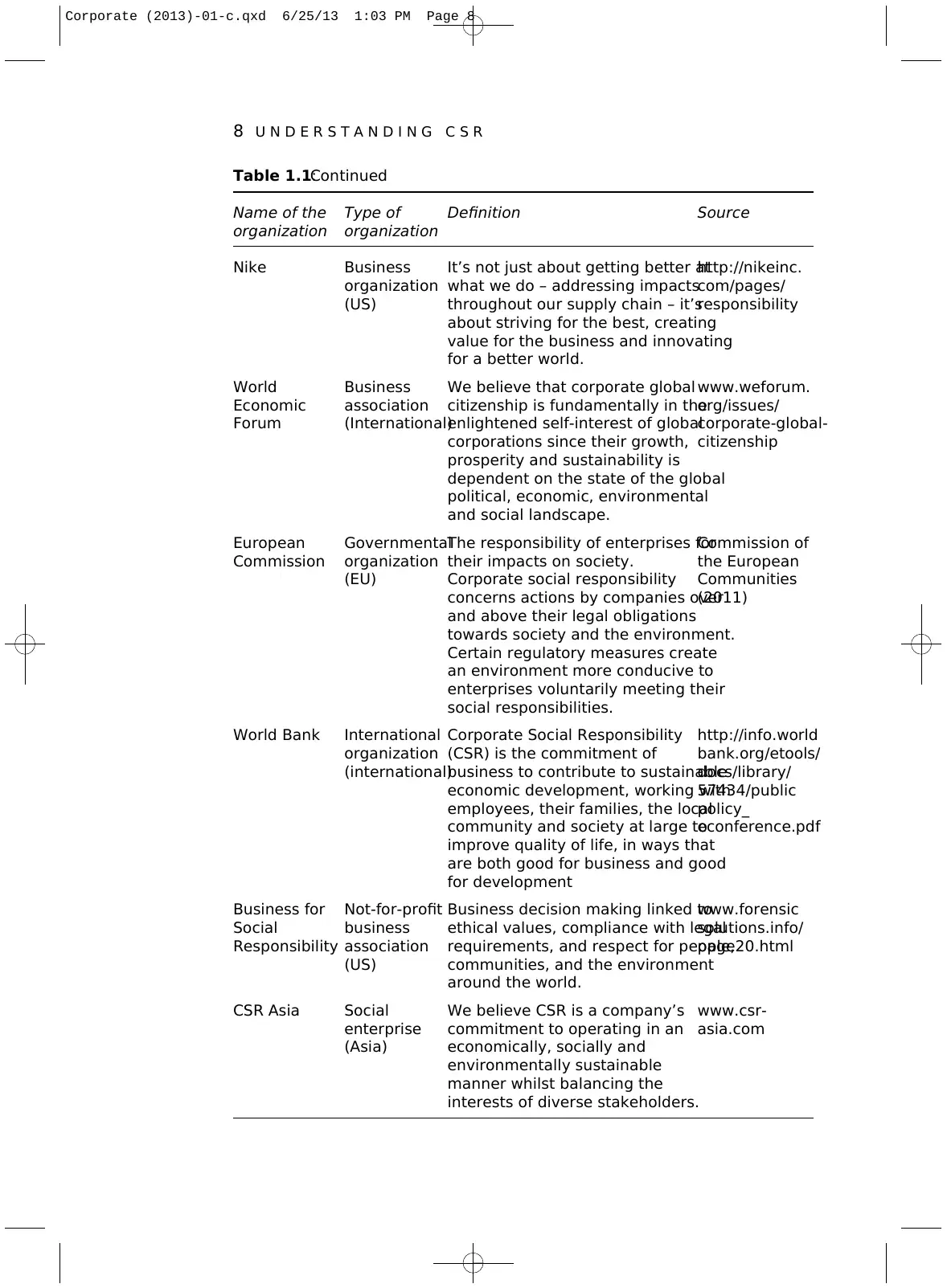

Table 1.1:Continued

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

Tata Business Jamsetji Tata and those who followedwww.tata.com/

organization in his immediate wake set the CSRpdf/COH_2009/

(India) mandate for Tata companies: to lookcoh_foreword.pdf

beyond the generation of products

and profits to serving the communities

in which they functioned.

Foreign GovernmentalCorporate Social Responsibility (CSR)www.

Affairs and organization is defined as the way companies international.gc.

International (Canada) integrate social, environmental, andca/trade-

Trade economic concerns into their valuesagreements-

and operations in a transparent andaccords-

accountable manner. It is integral tocommerciaux/ds/

long-term business growth and csr.aspx?view=d

success, and it also plays an

important role in promoting

Canadian values internationally

and contributing to the sustainable

development of communities

Chinese GovernmentalA concrete action taken by Chinesewww.ethicalcorp.

Ministry of organization companies to implement the politicalcom

Commerce (China) aspiration of the new Communist

Party collective leadership – putting

people first to create a harmonious

society

Department GovernmentalThe voluntary actions that businessBERR (2009)

for Business, organization can take, over and above compliance

Innovation (UK) with minimum legal requirements,

and Skills to address both its own competitive

interests and the interests of wider

society.

MVO Nederland NGO The Corporate Social Responsibilitywww.

(CSR (Netherlands)approach means that the companymvonederland.nl/

Netherlands) takes responsibility for the effects ofcontent/pagina/

the business’ activities on people andwat-mvo

the environment. The company makes

conscious choices in order to find a

balance between People, Planet and

Profit. Businesses can even go a step

further and focus on new market

opportunities, growth and innovation

with a view to profiting people, society

and the environment. Voluntary

commitment to society.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Table 1.1:Continued

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

Tata Business Jamsetji Tata and those who followedwww.tata.com/

organization in his immediate wake set the CSRpdf/COH_2009/

(India) mandate for Tata companies: to lookcoh_foreword.pdf

beyond the generation of products

and profits to serving the communities

in which they functioned.

Foreign GovernmentalCorporate Social Responsibility (CSR)www.

Affairs and organization is defined as the way companies international.gc.

International (Canada) integrate social, environmental, andca/trade-

Trade economic concerns into their valuesagreements-

and operations in a transparent andaccords-

accountable manner. It is integral tocommerciaux/ds/

long-term business growth and csr.aspx?view=d

success, and it also plays an

important role in promoting

Canadian values internationally

and contributing to the sustainable

development of communities

Chinese GovernmentalA concrete action taken by Chinesewww.ethicalcorp.

Ministry of organization companies to implement the politicalcom

Commerce (China) aspiration of the new Communist

Party collective leadership – putting

people first to create a harmonious

society

Department GovernmentalThe voluntary actions that businessBERR (2009)

for Business, organization can take, over and above compliance

Innovation (UK) with minimum legal requirements,

and Skills to address both its own competitive

interests and the interests of wider

society.

MVO Nederland NGO The Corporate Social Responsibilitywww.

(CSR (Netherlands)approach means that the companymvonederland.nl/

Netherlands) takes responsibility for the effects ofcontent/pagina/

the business’ activities on people andwat-mvo

the environment. The company makes

conscious choices in order to find a

balance between People, Planet and

Profit. Businesses can even go a step

further and focus on new market

opportunities, growth and innovation

with a view to profiting people, society

and the environment. Voluntary

commitment to society.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 7

8 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

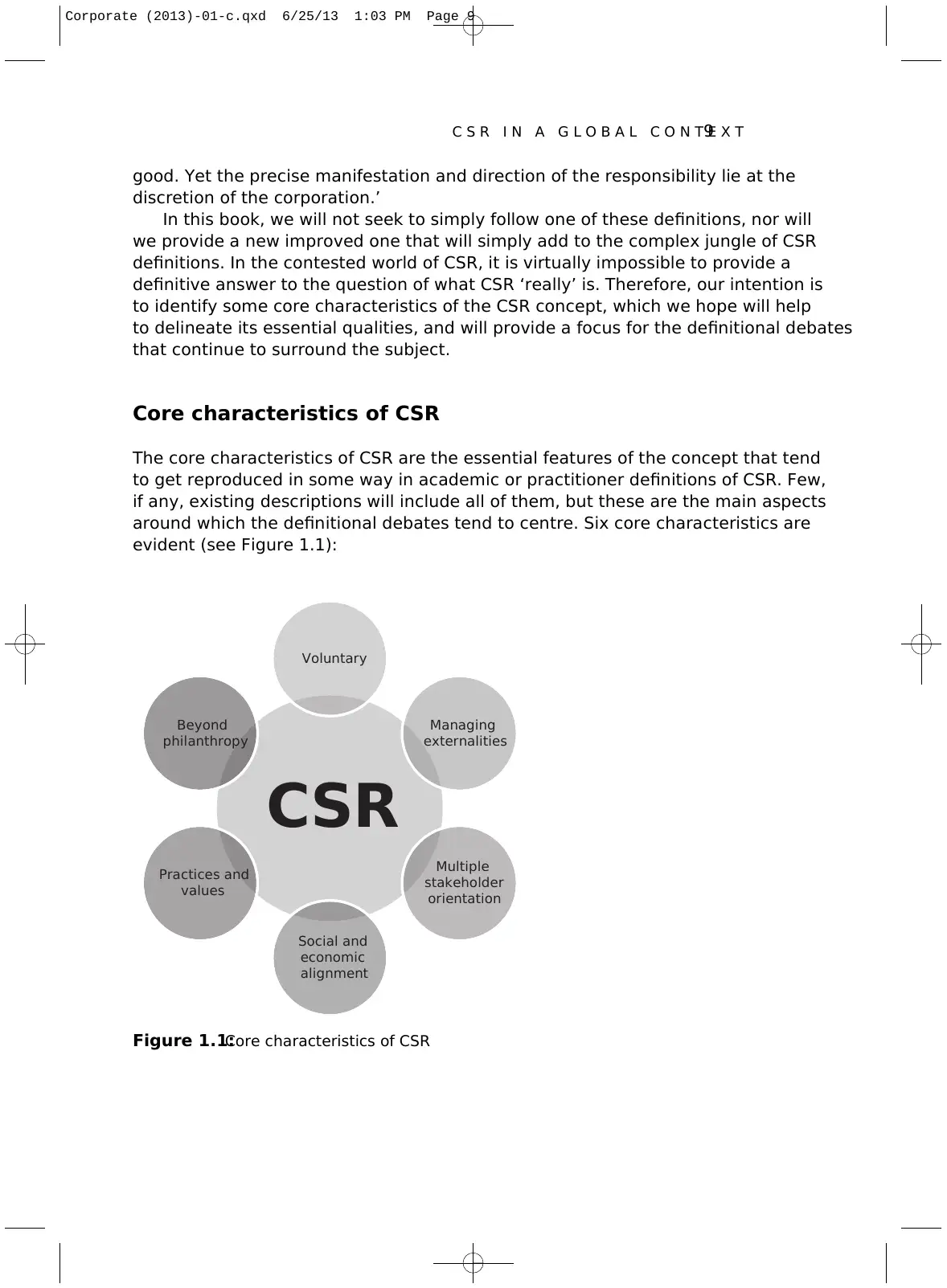

Table 1.1:Continued

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

Nike Business It’s not just about getting better athttp://nikeinc.

organization what we do – addressing impactscom/pages/

(US) throughout our supply chain – it’sresponsibility

about striving for the best, creating

value for the business and innovating

for a better world.

World Business We believe that corporate global www.weforum.

Economic association citizenship is fundamentally in theorg/issues/

Forum (International)enlightened self-interest of globalcorporate-global-

corporations since their growth, citizenship

prosperity and sustainability is

dependent on the state of the global

political, economic, environmental

and social landscape.

European GovernmentalThe responsibility of enterprises forCommission of

Commission organization their impacts on society. the European

(EU) Corporate social responsibility Communities

concerns actions by companies over(2011)

and above their legal obligations

towards society and the environment.

Certain regulatory measures create

an environment more conducive to

enterprises voluntarily meeting their

social responsibilities.

World Bank International Corporate Social Responsibility http://info.world

organization (CSR) is the commitment of bank.org/etools/

(international)business to contribute to sustainabledocs/library/

economic development, working with57434/public

employees, their families, the localpolicy_

community and society at large toeconference.pdf

improve quality of life, in ways that

are both good for business and good

for development

Business for Not-for-profit Business decision making linked towww.forensic

Social business ethical values, compliance with legalsolutions.info/

Responsibility association requirements, and respect for people,page20.html

(US) communities, and the environment

around the world.

CSR Asia Social We believe CSR is a company’s www.csr-

enterprise commitment to operating in an asia.com

(Asia) economically, socially and

environmentally sustainable

manner whilst balancing the

interests of diverse stakeholders.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Table 1.1:Continued

Name of the Type of Definition Source

organization organization

Nike Business It’s not just about getting better athttp://nikeinc.

organization what we do – addressing impactscom/pages/

(US) throughout our supply chain – it’sresponsibility

about striving for the best, creating

value for the business and innovating

for a better world.

World Business We believe that corporate global www.weforum.

Economic association citizenship is fundamentally in theorg/issues/

Forum (International)enlightened self-interest of globalcorporate-global-

corporations since their growth, citizenship

prosperity and sustainability is

dependent on the state of the global

political, economic, environmental

and social landscape.

European GovernmentalThe responsibility of enterprises forCommission of

Commission organization their impacts on society. the European

(EU) Corporate social responsibility Communities

concerns actions by companies over(2011)

and above their legal obligations

towards society and the environment.

Certain regulatory measures create

an environment more conducive to

enterprises voluntarily meeting their

social responsibilities.

World Bank International Corporate Social Responsibility http://info.world

organization (CSR) is the commitment of bank.org/etools/

(international)business to contribute to sustainabledocs/library/

economic development, working with57434/public

employees, their families, the localpolicy_

community and society at large toeconference.pdf

improve quality of life, in ways that

are both good for business and good

for development

Business for Not-for-profit Business decision making linked towww.forensic

Social business ethical values, compliance with legalsolutions.info/

Responsibility association requirements, and respect for people,page20.html

(US) communities, and the environment

around the world.

CSR Asia Social We believe CSR is a company’s www.csr-

enterprise commitment to operating in an asia.com

(Asia) economically, socially and

environmentally sustainable

manner whilst balancing the

interests of diverse stakeholders.

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

good. Yet the precise manifestation and direction of the responsibility lie at the

discretion of the corporation.’

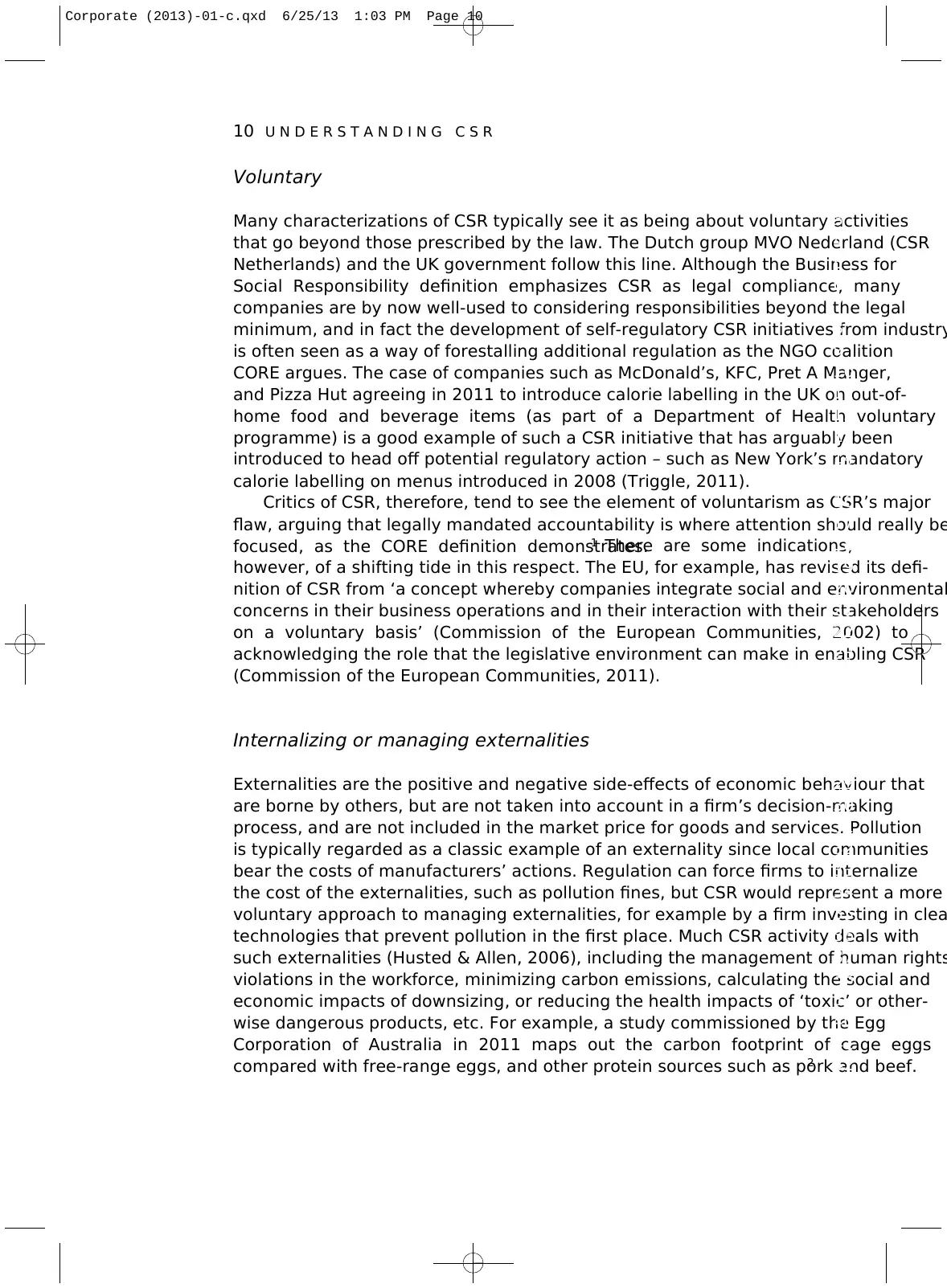

In this book, we will not seek to simply follow one of these definitions, nor will

we provide a new improved one that will simply add to the complex jungle of CSR

definitions. In the contested world of CSR, it is virtually impossible to provide a

definitive answer to the question of what CSR ‘really’ is. Therefore, our intention is

to identify some core characteristics of the CSR concept, which we hope will help

to delineate its essential qualities, and will provide a focus for the definitional debates

that continue to surround the subject.

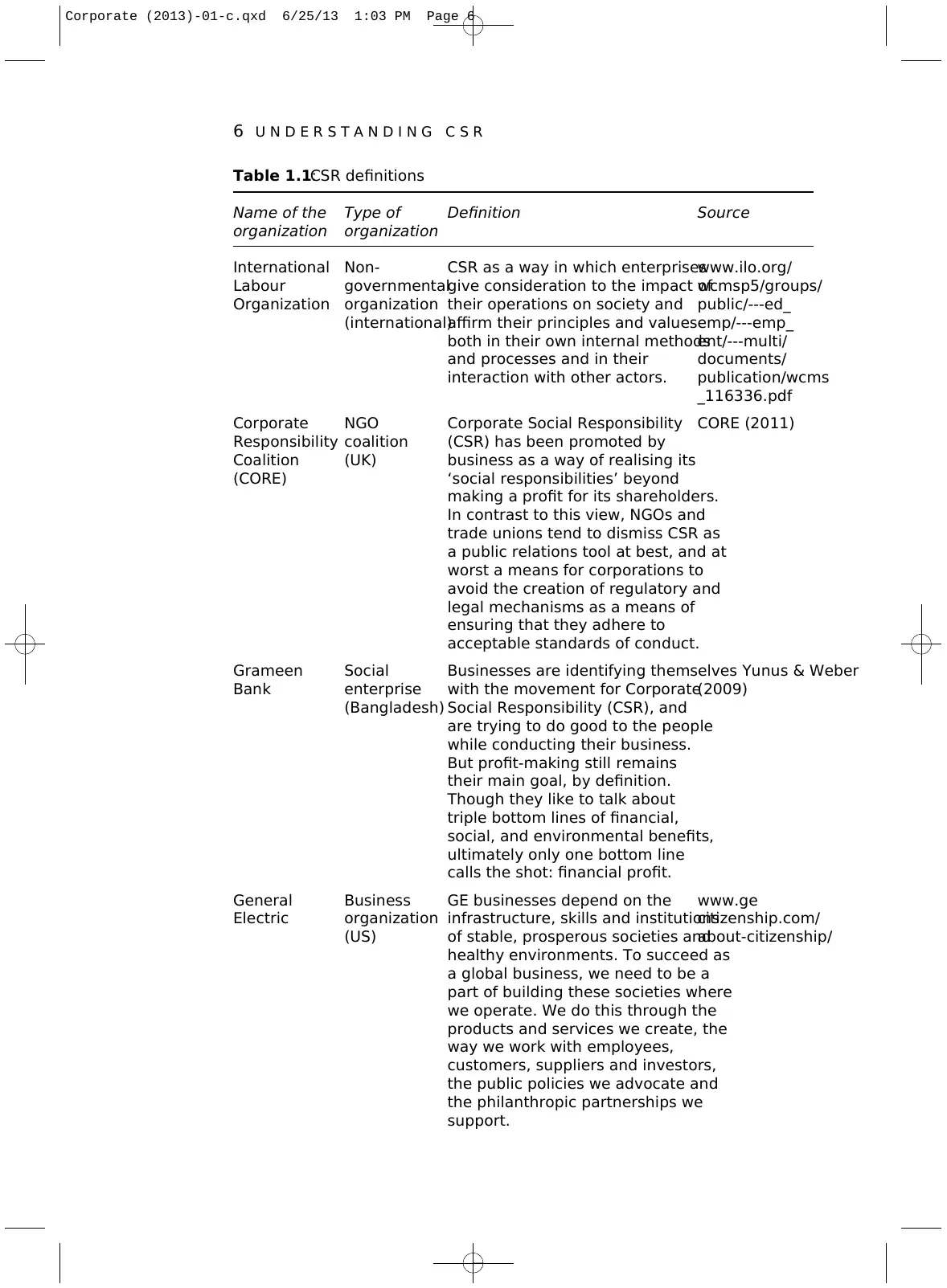

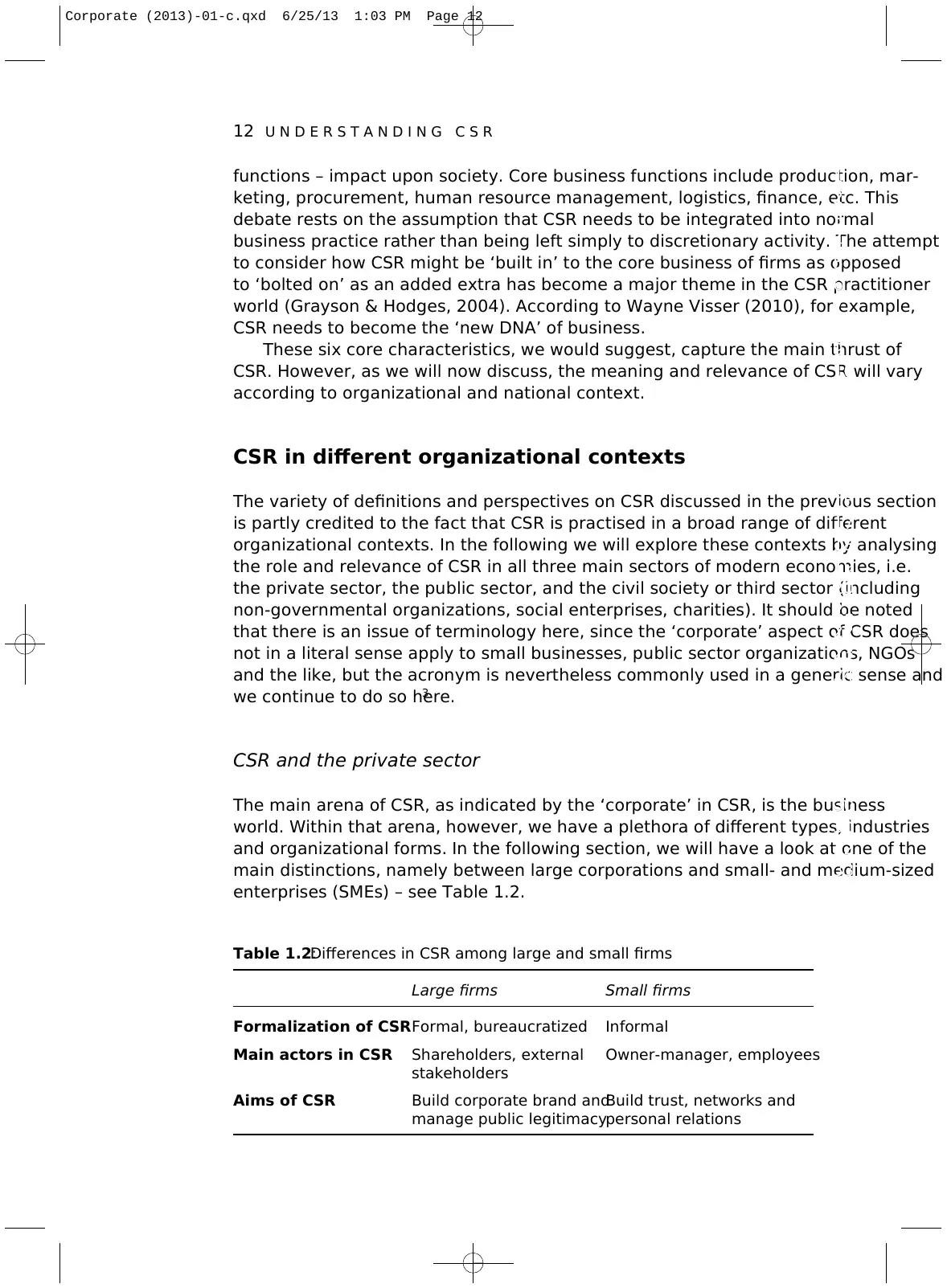

Core characteristics of CSR

The core characteristics of CSR are the essential features of the concept that tend

to get reproduced in some way in academic or practitioner definitions of CSR. Few,

if any, existing descriptions will include all of them, but these are the main aspects

around which the definitional debates tend to centre. Six core characteristics are

evident (see Figure 1.1):

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Voluntary

Beyond

philanthropy

Managing

externalities

CSR

Practices and

values

Social and

economic

alignment

Multiple

stakeholder

orientation

Figure 1.1:Core characteristics of CSR

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 9

discretion of the corporation.’

In this book, we will not seek to simply follow one of these definitions, nor will

we provide a new improved one that will simply add to the complex jungle of CSR

definitions. In the contested world of CSR, it is virtually impossible to provide a

definitive answer to the question of what CSR ‘really’ is. Therefore, our intention is

to identify some core characteristics of the CSR concept, which we hope will help

to delineate its essential qualities, and will provide a focus for the definitional debates

that continue to surround the subject.

Core characteristics of CSR

The core characteristics of CSR are the essential features of the concept that tend

to get reproduced in some way in academic or practitioner definitions of CSR. Few,

if any, existing descriptions will include all of them, but these are the main aspects

around which the definitional debates tend to centre. Six core characteristics are

evident (see Figure 1.1):

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Voluntary

Beyond

philanthropy

Managing

externalities

CSR

Practices and

values

Social and

economic

alignment

Multiple

stakeholder

orientation

Figure 1.1:Core characteristics of CSR

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

Voluntary

Many characterizations of CSR typically see it as being about voluntary activities

that go beyond those prescribed by the law. The Dutch group MVO Nederland (CSR

Netherlands) and the UK government follow this line. Although the Business for

Social Responsibility definition emphasizes CSR as legal compliance, many

companies are by now well-used to considering responsibilities beyond the legal

minimum, and in fact the development of self-regulatory CSR initiatives from industry

is often seen as a way of forestalling additional regulation as the NGO coalition

CORE argues. The case of companies such as McDonald’s, KFC, Pret A Manger,

and Pizza Hut agreeing in 2011 to introduce calorie labelling in the UK on out-of-

home food and beverage items (as part of a Department of Health voluntary

programme) is a good example of such a CSR initiative that has arguably been

introduced to head off potential regulatory action – such as New York’s mandatory

calorie labelling on menus introduced in 2008 (Triggle, 2011).

Critics of CSR, therefore, tend to see the element of voluntarism as CSR’s major

flaw, arguing that legally mandated accountability is where attention should really be

focused, as the CORE definition demonstrates.1 There are some indications,

however, of a shifting tide in this respect. The EU, for example, has revised its defi-

nition of CSR from ‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental

concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders

on a voluntary basis’ (Commission of the European Communities, 2002) to

acknowledging the role that the legislative environment can make in enabling CSR

(Commission of the European Communities, 2011).

Internalizing or managing externalities

Externalities are the positive and negative side-effects of economic behaviour that

are borne by others, but are not taken into account in a firm’s decision-making

process, and are not included in the market price for goods and services. Pollution

is typically regarded as a classic example of an externality since local communities

bear the costs of manufacturers’ actions. Regulation can force firms to internalize

the cost of the externalities, such as pollution fines, but CSR would represent a more

voluntary approach to managing externalities, for example by a firm investing in clea

technologies that prevent pollution in the first place. Much CSR activity deals with

such externalities (Husted & Allen, 2006), including the management of human rights

violations in the workforce, minimizing carbon emissions, calculating the social and

economic impacts of downsizing, or reducing the health impacts of ‘toxic’ or other-

wise dangerous products, etc. For example, a study commissioned by the Egg

Corporation of Australia in 2011 maps out the carbon footprint of cage eggs

compared with free-range eggs, and other protein sources such as pork and beef.2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 10

Voluntary

Many characterizations of CSR typically see it as being about voluntary activities

that go beyond those prescribed by the law. The Dutch group MVO Nederland (CSR

Netherlands) and the UK government follow this line. Although the Business for

Social Responsibility definition emphasizes CSR as legal compliance, many

companies are by now well-used to considering responsibilities beyond the legal

minimum, and in fact the development of self-regulatory CSR initiatives from industry

is often seen as a way of forestalling additional regulation as the NGO coalition

CORE argues. The case of companies such as McDonald’s, KFC, Pret A Manger,

and Pizza Hut agreeing in 2011 to introduce calorie labelling in the UK on out-of-

home food and beverage items (as part of a Department of Health voluntary

programme) is a good example of such a CSR initiative that has arguably been

introduced to head off potential regulatory action – such as New York’s mandatory

calorie labelling on menus introduced in 2008 (Triggle, 2011).

Critics of CSR, therefore, tend to see the element of voluntarism as CSR’s major

flaw, arguing that legally mandated accountability is where attention should really be

focused, as the CORE definition demonstrates.1 There are some indications,

however, of a shifting tide in this respect. The EU, for example, has revised its defi-

nition of CSR from ‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental

concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders

on a voluntary basis’ (Commission of the European Communities, 2002) to

acknowledging the role that the legislative environment can make in enabling CSR

(Commission of the European Communities, 2011).

Internalizing or managing externalities

Externalities are the positive and negative side-effects of economic behaviour that

are borne by others, but are not taken into account in a firm’s decision-making

process, and are not included in the market price for goods and services. Pollution

is typically regarded as a classic example of an externality since local communities

bear the costs of manufacturers’ actions. Regulation can force firms to internalize

the cost of the externalities, such as pollution fines, but CSR would represent a more

voluntary approach to managing externalities, for example by a firm investing in clea

technologies that prevent pollution in the first place. Much CSR activity deals with

such externalities (Husted & Allen, 2006), including the management of human rights

violations in the workforce, minimizing carbon emissions, calculating the social and

economic impacts of downsizing, or reducing the health impacts of ‘toxic’ or other-

wise dangerous products, etc. For example, a study commissioned by the Egg

Corporation of Australia in 2011 maps out the carbon footprint of cage eggs

compared with free-range eggs, and other protein sources such as pork and beef.2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 10

Multiple stakeholder orientation

CSR involves considering a range of interests and impacts among a variety of

different stakeholders other than just shareholders. The assumption that firms have

responsibilities to shareholders is usually not contested, but the point is that because

corporations rely on various other constituencies such as consumers, employees,

suppliers, and local communities in order to survive and prosper, they do not only

have responsibilities to shareholders. While many disagree on how much emphasis

should be given to shareholders in the CSR debate, and on the extent to which other

stakeholders should be taken into account, it is the expanding of corporate respon-

sibility to these other groups that characterizes much of the essential nature of CSR,

as illustrated by the CSR Asia definition in Table 1.1. We will discuss stakeholder

management in much more depth in Chapter 4

Alignment of social and economic responsibilities

This balancing of different stakeholder interests leads to a fourth facet. While CSR

may be about going beyond a narrow focus on shareholders and profitability, many

also believe that it should not, however, conflict with profitability. Although this is

much debated, many definitions of CSR from business and government stress that

it is about enlightened self-interest where social and economic responsibilities are

aligned. See, for example, the definitions of the Canadian Foreign Affairs and

International Trade, and General Electric. This feature has prompted much attention

to the business case for CSR – namely, how firms can benefit economically from

being socially responsible.

Practices and values

CSR is clearly about a particular set of business practices and strategies that deal

with social issues, but for many people it is also about something more than that –

namely a philosophy or set of values that underpins these practices. This perspective

is evident in both the BSR and Chinese Government definitions of CSR given in

Table 1.1. The values dimension of CSR is part of the reason why the subject raises

so much disagreement – if it were just about what companies did in the social arena,

it would not cause so much controversy as the debate about why they do it.

Beyond philanthropy

In some regions of the world, CSR is mainly about philanthropy – i.e. corporate

largesse towards the less fortunate. But the current debate on CSR has tended to

emphatically claim that ‘real’ CSR is about more than just philanthropy and com-

munity giving, but about how the entire operations of the firm – i.e. its core business

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T11

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 11

CSR involves considering a range of interests and impacts among a variety of

different stakeholders other than just shareholders. The assumption that firms have

responsibilities to shareholders is usually not contested, but the point is that because

corporations rely on various other constituencies such as consumers, employees,

suppliers, and local communities in order to survive and prosper, they do not only

have responsibilities to shareholders. While many disagree on how much emphasis

should be given to shareholders in the CSR debate, and on the extent to which other

stakeholders should be taken into account, it is the expanding of corporate respon-

sibility to these other groups that characterizes much of the essential nature of CSR,

as illustrated by the CSR Asia definition in Table 1.1. We will discuss stakeholder

management in much more depth in Chapter 4

Alignment of social and economic responsibilities

This balancing of different stakeholder interests leads to a fourth facet. While CSR

may be about going beyond a narrow focus on shareholders and profitability, many

also believe that it should not, however, conflict with profitability. Although this is

much debated, many definitions of CSR from business and government stress that

it is about enlightened self-interest where social and economic responsibilities are

aligned. See, for example, the definitions of the Canadian Foreign Affairs and

International Trade, and General Electric. This feature has prompted much attention

to the business case for CSR – namely, how firms can benefit economically from

being socially responsible.

Practices and values

CSR is clearly about a particular set of business practices and strategies that deal

with social issues, but for many people it is also about something more than that –

namely a philosophy or set of values that underpins these practices. This perspective

is evident in both the BSR and Chinese Government definitions of CSR given in

Table 1.1. The values dimension of CSR is part of the reason why the subject raises

so much disagreement – if it were just about what companies did in the social arena,

it would not cause so much controversy as the debate about why they do it.

Beyond philanthropy

In some regions of the world, CSR is mainly about philanthropy – i.e. corporate

largesse towards the less fortunate. But the current debate on CSR has tended to

emphatically claim that ‘real’ CSR is about more than just philanthropy and com-

munity giving, but about how the entire operations of the firm – i.e. its core business

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T11

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

functions – impact upon society. Core business functions include production, mar-

keting, procurement, human resource management, logistics, finance, etc. This

debate rests on the assumption that CSR needs to be integrated into normal

business practice rather than being left simply to discretionary activity. The attempt

to consider how CSR might be ‘built in’ to the core business of firms as opposed

to ‘bolted on’ as an added extra has become a major theme in the CSR practitioner

world (Grayson & Hodges, 2004). According to Wayne Visser (2010), for example,

CSR needs to become the ‘new DNA’ of business.

These six core characteristics, we would suggest, capture the main thrust of

CSR. However, as we will now discuss, the meaning and relevance of CSR will vary

according to organizational and national context.

CSR in different organizational contexts

The variety of definitions and perspectives on CSR discussed in the previous section

is partly credited to the fact that CSR is practised in a broad range of different

organizational contexts. In the following we will explore these contexts by analysing

the role and relevance of CSR in all three main sectors of modern economies, i.e.

the private sector, the public sector, and the civil society or third sector (including

non-governmental organizations, social enterprises, charities). It should be noted

that there is an issue of terminology here, since the ‘corporate’ aspect of CSR does

not in a literal sense apply to small businesses, public sector organizations, NGOs

and the like, but the acronym is nevertheless commonly used in a generic sense and

we continue to do so here.3

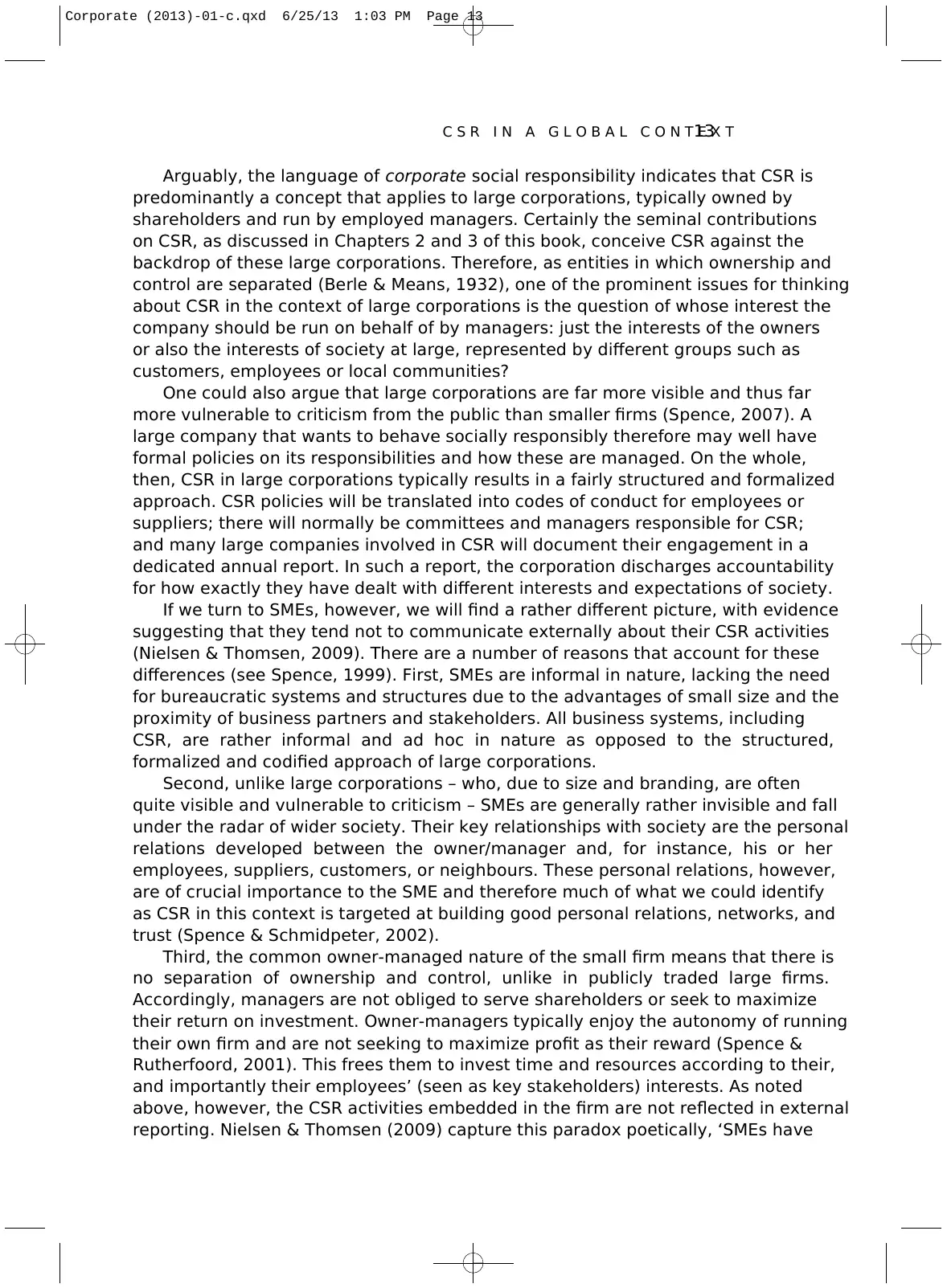

CSR and the private sector

The main arena of CSR, as indicated by the ‘corporate’ in CSR, is the business

world. Within that arena, however, we have a plethora of different types, industries

and organizational forms. In the following section, we will have a look at one of the

main distinctions, namely between large corporations and small- and medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs) – see Table 1.2.

12 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Table 1.2:Differences in CSR among large and small firms

Large firms Small firms

Formalization of CSRFormal, bureaucratized Informal

Main actors in CSR Shareholders, external Owner-manager, employees

stakeholders

Aims of CSR Build corporate brand andBuild trust, networks and

manage public legitimacypersonal relations

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 12

keting, procurement, human resource management, logistics, finance, etc. This

debate rests on the assumption that CSR needs to be integrated into normal

business practice rather than being left simply to discretionary activity. The attempt

to consider how CSR might be ‘built in’ to the core business of firms as opposed

to ‘bolted on’ as an added extra has become a major theme in the CSR practitioner

world (Grayson & Hodges, 2004). According to Wayne Visser (2010), for example,

CSR needs to become the ‘new DNA’ of business.

These six core characteristics, we would suggest, capture the main thrust of

CSR. However, as we will now discuss, the meaning and relevance of CSR will vary

according to organizational and national context.

CSR in different organizational contexts

The variety of definitions and perspectives on CSR discussed in the previous section

is partly credited to the fact that CSR is practised in a broad range of different

organizational contexts. In the following we will explore these contexts by analysing

the role and relevance of CSR in all three main sectors of modern economies, i.e.

the private sector, the public sector, and the civil society or third sector (including

non-governmental organizations, social enterprises, charities). It should be noted

that there is an issue of terminology here, since the ‘corporate’ aspect of CSR does

not in a literal sense apply to small businesses, public sector organizations, NGOs

and the like, but the acronym is nevertheless commonly used in a generic sense and

we continue to do so here.3

CSR and the private sector

The main arena of CSR, as indicated by the ‘corporate’ in CSR, is the business

world. Within that arena, however, we have a plethora of different types, industries

and organizational forms. In the following section, we will have a look at one of the

main distinctions, namely between large corporations and small- and medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs) – see Table 1.2.

12 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Table 1.2:Differences in CSR among large and small firms

Large firms Small firms

Formalization of CSRFormal, bureaucratized Informal

Main actors in CSR Shareholders, external Owner-manager, employees

stakeholders

Aims of CSR Build corporate brand andBuild trust, networks and

manage public legitimacypersonal relations

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 12

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Arguably, the language of corporate social responsibility indicates that CSR is

predominantly a concept that applies to large corporations, typically owned by

shareholders and run by employed managers. Certainly the seminal contributions

on CSR, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 of this book, conceive CSR against the

backdrop of these large corporations. Therefore, as entities in which ownership and

control are separated (Berle & Means, 1932), one of the prominent issues for thinking

about CSR in the context of large corporations is the question of whose interest the

company should be run on behalf of by managers: just the interests of the owners

or also the interests of society at large, represented by different groups such as

customers, employees or local communities?

One could also argue that large corporations are far more visible and thus far

more vulnerable to criticism from the public than smaller firms (Spence, 2007). A

large company that wants to behave socially responsibly therefore may well have

formal policies on its responsibilities and how these are managed. On the whole,

then, CSR in large corporations typically results in a fairly structured and formalized

approach. CSR policies will be translated into codes of conduct for employees or

suppliers; there will normally be committees and managers responsible for CSR;

and many large companies involved in CSR will document their engagement in a

dedicated annual report. In such a report, the corporation discharges accountability

for how exactly they have dealt with different interests and expectations of society.

If we turn to SMEs, however, we will find a rather different picture, with evidence

suggesting that they tend not to communicate externally about their CSR activities

(Nielsen & Thomsen, 2009). There are a number of reasons that account for these

differences (see Spence, 1999). First, SMEs are informal in nature, lacking the need

for bureaucratic systems and structures due to the advantages of small size and the

proximity of business partners and stakeholders. All business systems, including

CSR, are rather informal and ad hoc in nature as opposed to the structured,

formalized and codified approach of large corporations.

Second, unlike large corporations – who, due to size and branding, are often

quite visible and vulnerable to criticism – SMEs are generally rather invisible and fall

under the radar of wider society. Their key relationships with society are the personal

relations developed between the owner/manager and, for instance, his or her

employees, suppliers, customers, or neighbours. These personal relations, however,

are of crucial importance to the SME and therefore much of what we could identify

as CSR in this context is targeted at building good personal relations, networks, and

trust (Spence & Schmidpeter, 2002).

Third, the common owner-managed nature of the small firm means that there is

no separation of ownership and control, unlike in publicly traded large firms.

Accordingly, managers are not obliged to serve shareholders or seek to maximize

their return on investment. Owner-managers typically enjoy the autonomy of running

their own firm and are not seeking to maximize profit as their reward (Spence &

Rutherfoord, 2001). This frees them to invest time and resources according to their,

and importantly their employees’ (seen as key stakeholders) interests. As noted

above, however, the CSR activities embedded in the firm are not reflected in external

reporting. Nielsen & Thomsen (2009) capture this paradox poetically, ‘SMEs have

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T13

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 13

predominantly a concept that applies to large corporations, typically owned by

shareholders and run by employed managers. Certainly the seminal contributions

on CSR, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 of this book, conceive CSR against the

backdrop of these large corporations. Therefore, as entities in which ownership and

control are separated (Berle & Means, 1932), one of the prominent issues for thinking

about CSR in the context of large corporations is the question of whose interest the

company should be run on behalf of by managers: just the interests of the owners

or also the interests of society at large, represented by different groups such as

customers, employees or local communities?

One could also argue that large corporations are far more visible and thus far

more vulnerable to criticism from the public than smaller firms (Spence, 2007). A

large company that wants to behave socially responsibly therefore may well have

formal policies on its responsibilities and how these are managed. On the whole,

then, CSR in large corporations typically results in a fairly structured and formalized

approach. CSR policies will be translated into codes of conduct for employees or

suppliers; there will normally be committees and managers responsible for CSR;

and many large companies involved in CSR will document their engagement in a

dedicated annual report. In such a report, the corporation discharges accountability

for how exactly they have dealt with different interests and expectations of society.

If we turn to SMEs, however, we will find a rather different picture, with evidence

suggesting that they tend not to communicate externally about their CSR activities

(Nielsen & Thomsen, 2009). There are a number of reasons that account for these

differences (see Spence, 1999). First, SMEs are informal in nature, lacking the need

for bureaucratic systems and structures due to the advantages of small size and the

proximity of business partners and stakeholders. All business systems, including

CSR, are rather informal and ad hoc in nature as opposed to the structured,

formalized and codified approach of large corporations.

Second, unlike large corporations – who, due to size and branding, are often

quite visible and vulnerable to criticism – SMEs are generally rather invisible and fall

under the radar of wider society. Their key relationships with society are the personal

relations developed between the owner/manager and, for instance, his or her

employees, suppliers, customers, or neighbours. These personal relations, however,

are of crucial importance to the SME and therefore much of what we could identify

as CSR in this context is targeted at building good personal relations, networks, and

trust (Spence & Schmidpeter, 2002).

Third, the common owner-managed nature of the small firm means that there is

no separation of ownership and control, unlike in publicly traded large firms.

Accordingly, managers are not obliged to serve shareholders or seek to maximize

their return on investment. Owner-managers typically enjoy the autonomy of running

their own firm and are not seeking to maximize profit as their reward (Spence &

Rutherfoord, 2001). This frees them to invest time and resources according to their,

and importantly their employees’ (seen as key stakeholders) interests. As noted

above, however, the CSR activities embedded in the firm are not reflected in external

reporting. Nielsen & Thomsen (2009) capture this paradox poetically, ‘SMEs have

C S R I N A G L O B A L C O N T E X T13

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 13

no interest in turning their local and authentic practice into a forced marketing and

branding exercise.’

Overall, it is probably fair to say that given the importance of SMEs, which in

much of the world account for the majority of private sector employment and GDP

in their countries, the CSR literature has so far paid disproportionate attention to

larger organizations (Morsing & Perrini, 2009). This gap in research is highlighted

further where family businesses – also a majority form in the private sector and

relevant to both large and small firms – are taken into account. A range of issues

related to the mixing of public and private objectives and the influence of succession

issues and family legacy have important impacts on CSR which are yet to be fully

understood (Mitchell et al, 2011).

CSR and the public sector

At first sight, one would not necessarily expect CSR to be an issue for public sector

organizations, such as government ministries, agencies or local administrative bodies

After all, it is ‘corporate’ social responsibility. However, in most industrialized

countries, governments still supply a large amount of all goods and services, some-

where between 40–50 per cent of the GDP in many countries. Consequently, the

same demands made upon corporations to conduct their operations in a socially

responsible fashion are increasingly applied to public sector organizations as well.

For example, public sector organizations face the similar environmental demands,

similar claims for equal opportunities for employees, and similar expectations for

responsible sourcing as do private companies. Consequently, we increasingly find

public sector organizations adopting CSR policies, practices and tools very similar

to those found in the private sector.

In some ways, these demands for social responsibility in the public sector could

be considered more pronounced due in part to the public service ethos (Van der

Wal et al, 2008). Public organizations, such as schools, hospitals, or universities,

by definition have social aims and are mostly run on a not-for-profit basis. This

establishes the social dimension of their responsibility at the core of their operations.

Furthermore, given the size of many public bodies and agencies, as well as their

quasi-monopolistic position in many areas of services, they are likely to have an

impact on society that is often far beyond the impact of a single large corporation.

Consequently, the claim for responsible behaviour on the part of public bodies has

grown, as has the demand for greater accountability to society in the public sector.

Just as private sector companies are exhorted to become more accountable in their

reporting and communication to the public, so we now witness a steady rise in the

use of typical CSR instruments, such as social auditing and reporting, by public

bodies (Ball, 2004). The United States Postal Service, for example, has been

publishing social responsibility and sustainability reports since 2008.4

Apart from incorporating CSR into their own operations, many government

organizations also take an active role in promoting CSR within their sphere of

influence, including going beyond their borders. For example, the Sino-German CSR

14 U N D E R S T A N D I N G C S R

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Corporate (2013)-01-c.qxd 6/25/13 1:03 PM Page 14

branding exercise.’

Overall, it is probably fair to say that given the importance of SMEs, which in

much of the world account for the majority of private sector employment and GDP

in their countries, the CSR literature has so far paid disproportionate attention to

larger organizations (Morsing & Perrini, 2009). This gap in research is highlighted

further where family businesses – also a majority form in the private sector and

relevant to both large and small firms – are taken into account. A range of issues

related to the mixing of public and private objectives and the influence of succession

issues and family legacy have important impacts on CSR which are yet to be fully

understood (Mitchell et al, 2011).

CSR and the public sector

At first sight, one would not necessarily expect CSR to be an issue for public sector

organizations, such as government ministries, agencies or local administrative bodies

After all, it is ‘corporate’ social responsibility. However, in most industrialized

countries, governments still supply a large amount of all goods and services, some-

where between 40–50 per cent of the GDP in many countries. Consequently, the

same demands made upon corporations to conduct their operations in a socially

responsible fashion are increasingly applied to public sector organizations as well.

For example, public sector organizations face the similar environmental demands,

similar claims for equal opportunities for employees, and similar expectations for

responsible sourcing as do private companies. Consequently, we increasingly find

public sector organizations adopting CSR policies, practices and tools very similar

to those found in the private sector.

In some ways, these demands for social responsibility in the public sector could

be considered more pronounced due in part to the public service ethos (Van der

Wal et al, 2008). Public organizations, such as schools, hospitals, or universities,

by definition have social aims and are mostly run on a not-for-profit basis. This

establishes the social dimension of their responsibility at the core of their operations.

Furthermore, given the size of many public bodies and agencies, as well as their

quasi-monopolistic position in many areas of services, they are likely to have an

impact on society that is often far beyond the impact of a single large corporation.

Consequently, the claim for responsible behaviour on the part of public bodies has