Case Competition: Craft Beer Industry Analysis, Johnson & Wales

VerifiedAdded on 2021/03/26

|10

|6196

|366

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines the competitive landscape of the U.S. craft beer industry during the 2010s, a period of rapid growth and change. It explores the rise of microbreweries and their impact on established brands like Budweiser, Miller, and Coors, detailing the shift in consumer preferences towards unique and high-quality beers. The case analyzes market trends, including the slowing growth in the industry, increasing competition, and the effects of consolidation and grain price fluctuations. It also delves into the beer production process, legal regulations, and the economics of scale for breweries of different sizes. Furthermore, the study highlights the impact of regulations on sales, distribution, and employment, and the challenges posed by lawsuits and trademark infringements. The case provides insights into the evolving market, competition, and the factors influencing the success of craft breweries.

Competition in the Craft

Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz

John D. Varlaro

Johnson & Wales University

John E. Gamble

Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi

Locally produced or regional craft beers caused a

seismic shift in the U.S. beer industry during the

early 2010s with the gains of the small, regional

newcomers coming at the expense of such well-known

brands as Budweiser, Miller, Coors, and Bud Light.

Craft breweries, which by definition sold fewer than

6 million barrels (bbls) per year, expanded rapidly

with the deregulation of intrastate alcohol distribution

and retail laws and a change in consumer preferences

toward unique and high-quality beers. The growing

popularity of craft beers led to an approximate 5 per-

cent sales volume increase in craft beer in 2017.1

Yet, the overall beer industry had remained flat

in 2017 with total beer sales dropping by 1.2 percent

in the United States.2 The craft beer industry, too,

had begun to show signs of a slowdown going into

2018. While volume sales had increased by 5 percent

in 2017 and annual growth had averaged 13.6 percent

from 2012 to 2017, projections had slowed dramati-

cally to 1.3 percent from 2017 to 2022.3 Yet there did

not seem to be a slowdown in the number of new

craft brewers entering the market. Industry com-

petition was increasing as grain price fluctuations

affected cost structures and growing consolidation

within the beer industry—led most notably by AB

InBev’s acquisition of several craft breweries, Grupo

Modelo, and its acquisition of SABMiller—and cre-

ated a battle for market share. While the market

for specialty beer was expected to gradually plateau

by 2020, it appeared that the slowing growth had

arrived by 2017. Nevertheless, craft breweries and

microbreweries were expected to expand in number

and in terms of market share as consumers sought

out new pale ales, stouts, wheat beers, pilsners, and

lagers with regional or local flairs.

THEŗBEERŗMARKET

The total economic impact of the beer market was

estimated to be 2.0 percent of total U.S. GDP in

2016 when variables such as jobs within beer pro-

duction, sales and distribution were included.4 Total

revenue for the craft beer industry was estimated at

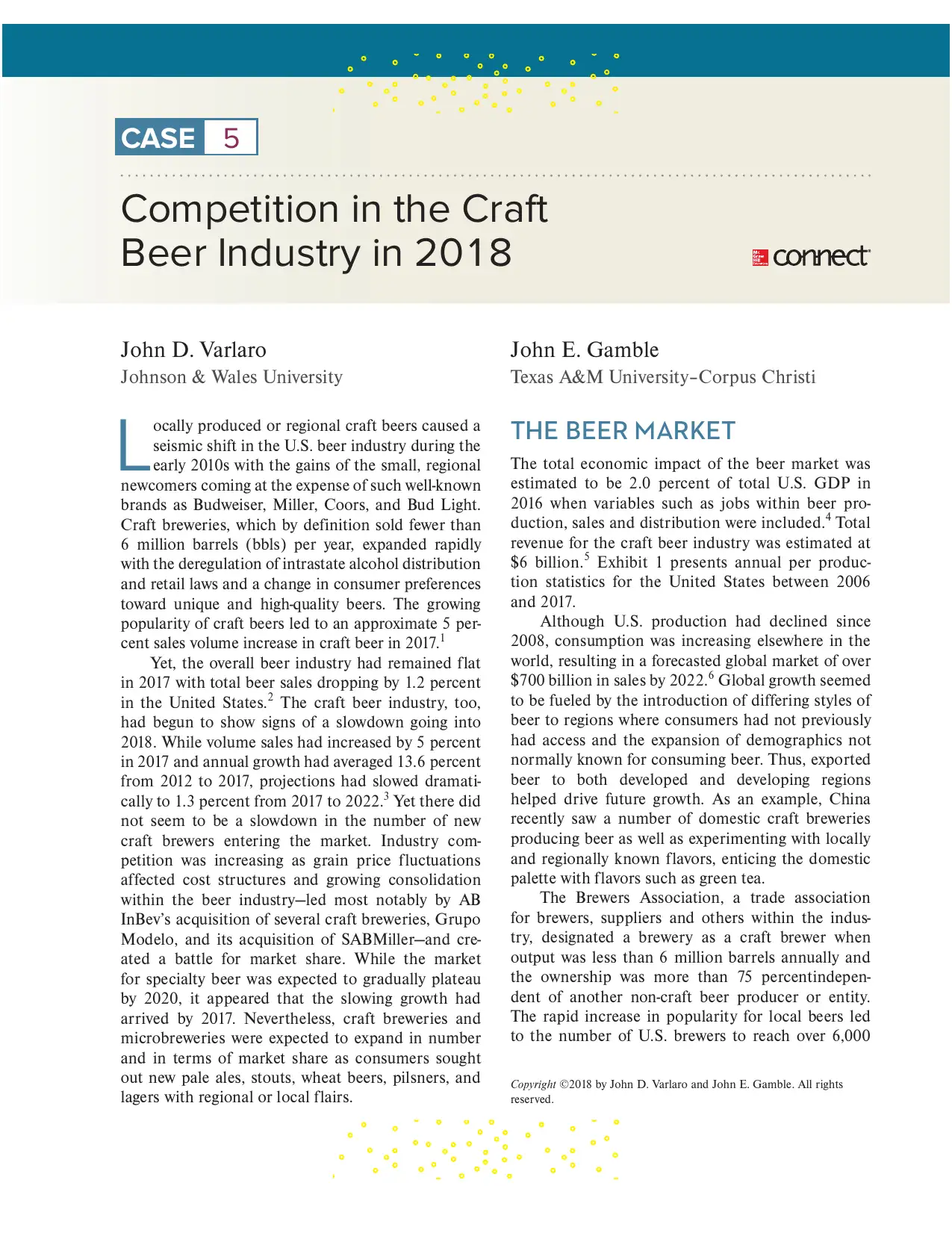

$6 billion.5 Exhibit 1 presents annual per produc-

tion statistics for the United States between 2006

and 2017.

Although U.S. production had declined since

2008, consumption was increasing elsewhere in the

world, resulting in a forecasted global market of over

$700 billion in sales by 2022.6 Global growth seemed

to be fueled by the introduction of differing styles of

beer to regions where consumers had not previously

had access and the expansion of demographics not

normally known for consuming beer. Thus, exported

beer to both developed and developing regions

helped drive future growth. As an example, China

recently saw a number of domestic craft breweries

producing beer as well as experimenting with locally

and regionally known flavors, enticing the domestic

palette with flavors such as green tea.

The Brewers Association, a trade association

for brewers, suppliers and others within the indus-

try, designated a brewery as a craft brewer when

output was less than 6 million barrels annually and

the ownership was more than 75 percentindepen-

dent of another non-craft beer producer or entity.

The rapid increase in popularity for local beers led

to the number of U.S. brewers to reach over 6,000

CASE ǰ

Copyright ©2018 by John D. Varlaro and John E. Gamble. All rights

reserved.

Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz

John D. Varlaro

Johnson & Wales University

John E. Gamble

Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi

Locally produced or regional craft beers caused a

seismic shift in the U.S. beer industry during the

early 2010s with the gains of the small, regional

newcomers coming at the expense of such well-known

brands as Budweiser, Miller, Coors, and Bud Light.

Craft breweries, which by definition sold fewer than

6 million barrels (bbls) per year, expanded rapidly

with the deregulation of intrastate alcohol distribution

and retail laws and a change in consumer preferences

toward unique and high-quality beers. The growing

popularity of craft beers led to an approximate 5 per-

cent sales volume increase in craft beer in 2017.1

Yet, the overall beer industry had remained flat

in 2017 with total beer sales dropping by 1.2 percent

in the United States.2 The craft beer industry, too,

had begun to show signs of a slowdown going into

2018. While volume sales had increased by 5 percent

in 2017 and annual growth had averaged 13.6 percent

from 2012 to 2017, projections had slowed dramati-

cally to 1.3 percent from 2017 to 2022.3 Yet there did

not seem to be a slowdown in the number of new

craft brewers entering the market. Industry com-

petition was increasing as grain price fluctuations

affected cost structures and growing consolidation

within the beer industry—led most notably by AB

InBev’s acquisition of several craft breweries, Grupo

Modelo, and its acquisition of SABMiller—and cre-

ated a battle for market share. While the market

for specialty beer was expected to gradually plateau

by 2020, it appeared that the slowing growth had

arrived by 2017. Nevertheless, craft breweries and

microbreweries were expected to expand in number

and in terms of market share as consumers sought

out new pale ales, stouts, wheat beers, pilsners, and

lagers with regional or local flairs.

THEŗBEERŗMARKET

The total economic impact of the beer market was

estimated to be 2.0 percent of total U.S. GDP in

2016 when variables such as jobs within beer pro-

duction, sales and distribution were included.4 Total

revenue for the craft beer industry was estimated at

$6 billion.5 Exhibit 1 presents annual per produc-

tion statistics for the United States between 2006

and 2017.

Although U.S. production had declined since

2008, consumption was increasing elsewhere in the

world, resulting in a forecasted global market of over

$700 billion in sales by 2022.6 Global growth seemed

to be fueled by the introduction of differing styles of

beer to regions where consumers had not previously

had access and the expansion of demographics not

normally known for consuming beer. Thus, exported

beer to both developed and developing regions

helped drive future growth. As an example, China

recently saw a number of domestic craft breweries

producing beer as well as experimenting with locally

and regionally known flavors, enticing the domestic

palette with flavors such as green tea.

The Brewers Association, a trade association

for brewers, suppliers and others within the indus-

try, designated a brewery as a craft brewer when

output was less than 6 million barrels annually and

the ownership was more than 75 percentindepen-

dent of another non-craft beer producer or entity.

The rapid increase in popularity for local beers led

to the number of U.S. brewers to reach over 6,000

CASE ǰ

Copyright ©2018 by John D. Varlaro and John E. Gamble. All rights

reserved.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

C-42 PARTƥƮ Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

EXHIBITŗş Barrels of Beer Produced in

the United States, 2006–2017

(millions of barrels)

Year Barrels produced (in millions)*

ǭǬǬDZ ɫǴdz

ǭǬǬDz ǭǬǬ

ǭǬǬdz ǭǬǬ

ǭǬǬǴ ɫǴDz

ǭǬɫǬ ɫǴǰ

ǭǬɫɫ ɫǴǮ

ǭǬɫǭ ɫǴDZ

ǭǬɫǮ ɫǴǭ

ǭǬɫǯ ɫǴǮ

ǭǬɫǰ ɫǴɫ

ǭǬɫDZ ɫǴǬ

ǭǬɫDz ɫdzDZ

*Rounded to the nearest million.

Source: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau website

EXHIBITŗŠ Top 10 U.S. Breweries in 2017

Rank Brewery

ɫ Anheuser-Busch, Inc

ǭ MillerCoors

Ǯ Constellation

ǯ Heineken

ǰ Pabst Brewing Company

DZ D.G. Yuengling and Son, Inc

Dz North American Breweries

dz Diageo

Ǵ Boston Beer Company

ɫǬ Sierra Nevada Brewing Company

Source: Brewers Association.

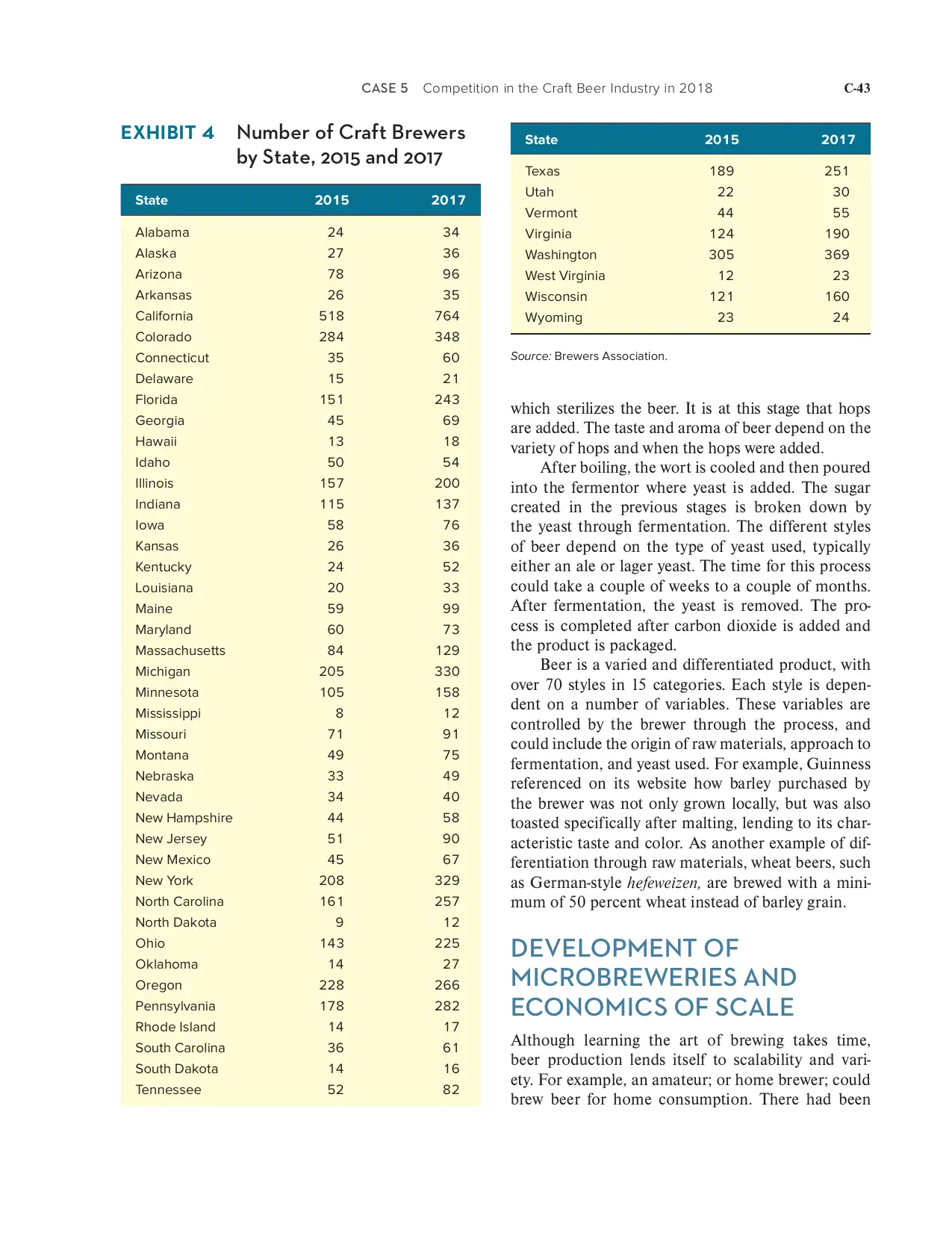

EXHIBITŗš Top 10 Global Beer

Producers by Volume,

2014–2016 (millions of

barrels)*

Rank Producer ǭǬɫǯ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDZ

ɫ Ab InBev** Ǯǰɫ ǮǰǮ ǯǮǰ

ǭ Heineken ɫdzǬ ɫdzDZ ɫǴǰ

Ǯ Carlsberg ɫɫǬ ɫǬDz ɫǬǭ

ǯ CR Snow*** N/A N/A ɫǬǬ

ǰ Molson Coors

Brewing Company

ǰǯ ǰǯ dzǭ

DZ Tsingtao (Group) Dzdz Dzǭ DZDz

Dz Asahi ǭDZ ǭǯ DZǬ

dz Beijing Yanjing ǯǰ ǯɫ Ǯdz

Ǵ Castel BGI ǭDZ ǭDZ ǭDZ

ɫǬ Kirin ǮDZ Ǯǰ ǭǯ

* Originally reported as hectoliters. Computed using ɫ hL = .dzǰǭ

barrel for comparison; to nearest million bbl.

** Now includes SABMiller; previous volumes for SABMiller in years

ǭǬɫǯ and ǭǬɫǰ prior to acquisition were ǭǯǴ and ǮǰǮ, respec-

tively, ranking it as second for both years.

*** Was not in top ɫǬ for ǭǬɫǯ and ǭǬɫǰ.

N/A: Not available.

Source: AB InBev ǭǬ-F SEC Document, ǭǬɫǰ, ǭǬɫDZ, ǭǬɫDz.

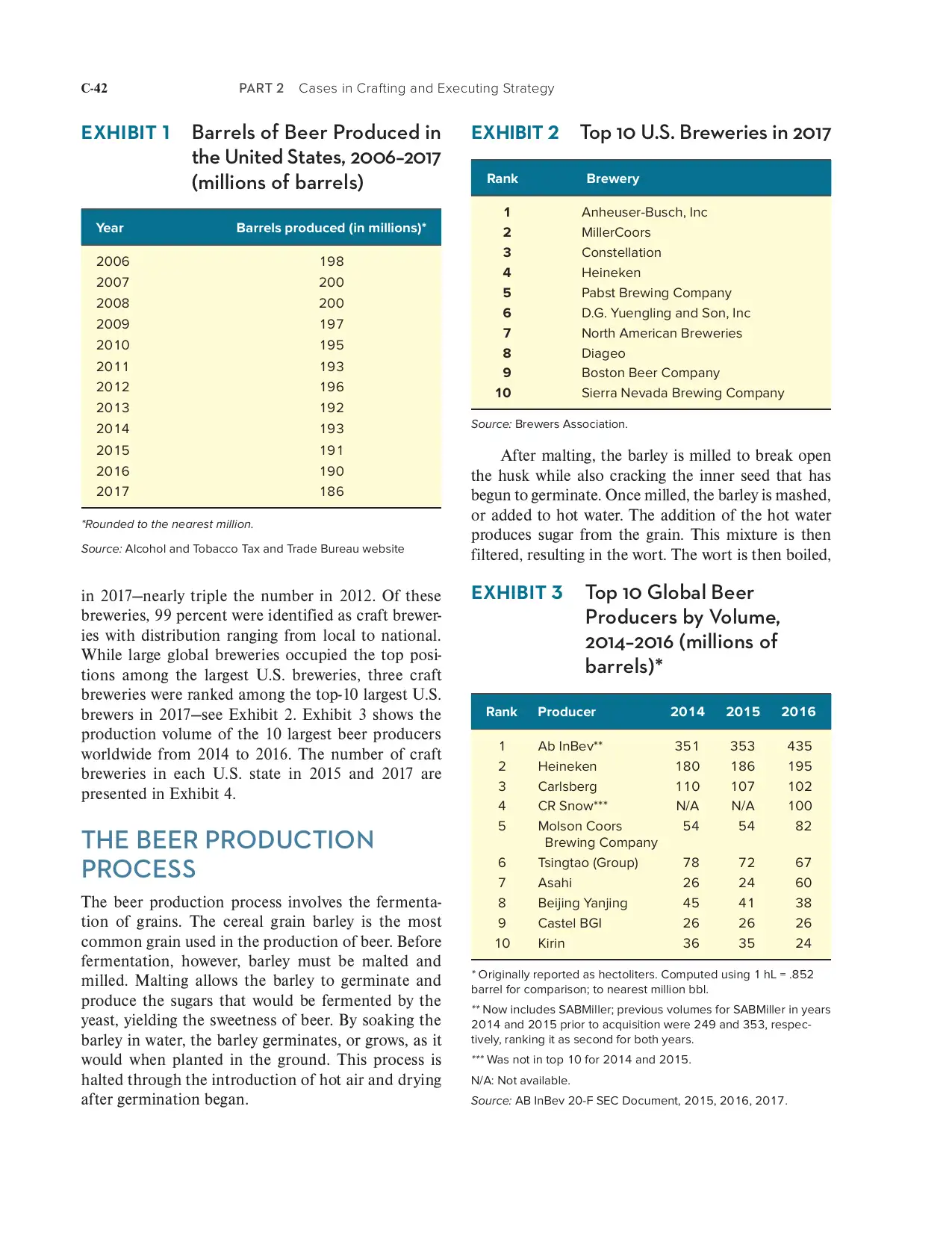

in 2017—nearly triple the number in 2012. Of these

breweries, 99 percent were identified as craft brewer-

ies with distribution ranging from local to national.

While large global breweries occupied the top posi-

tions among the largest U.S. breweries, three craft

breweries were ranked among the top-10 largest U.S.

brewers in 2017—see Exhibit 2. Exhibit 3 shows the

production volume of the 10 largest beer producers

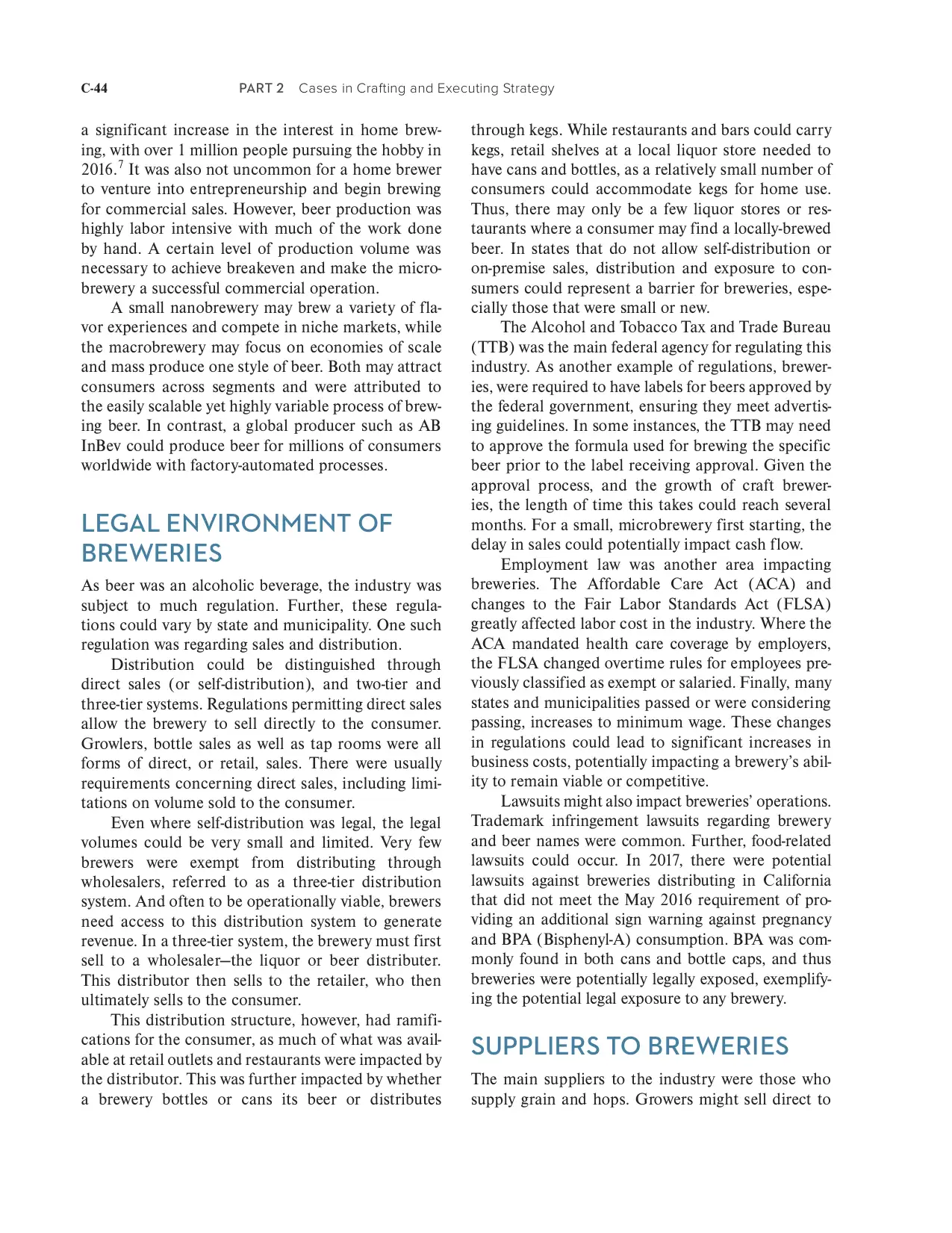

worldwide from 2014 to 2016. The number of craft

breweries in each U.S. state in 2015 and 2017 are

presented in Exhibit 4.

THEŗBEERŗPRODUCTIONŗ

PROCESS

The beer production process involves the fermenta-

tion of grains. The cereal grain barley is the most

common grain used in the production of beer. Before

fermentation, however, barley must be malted and

milled. Malting allows the barley to germinate and

produce the sugars that would be fermented by the

yeast, yielding the sweetness of beer. By soaking the

barley in water, the barley germinates, or grows, as it

would when planted in the ground. This process is

halted through the introduction of hot air and drying

after germination began.

After malting, the barley is milled to break open

the husk while also cracking the inner seed that has

begun to germinate. Once milled, the barley is mashed,

or added to hot water. The addition of the hot water

produces sugar from the grain. This mixture is then

filtered, resulting in the wort. The wort is then boiled,

EXHIBITŗş Barrels of Beer Produced in

the United States, 2006–2017

(millions of barrels)

Year Barrels produced (in millions)*

ǭǬǬDZ ɫǴdz

ǭǬǬDz ǭǬǬ

ǭǬǬdz ǭǬǬ

ǭǬǬǴ ɫǴDz

ǭǬɫǬ ɫǴǰ

ǭǬɫɫ ɫǴǮ

ǭǬɫǭ ɫǴDZ

ǭǬɫǮ ɫǴǭ

ǭǬɫǯ ɫǴǮ

ǭǬɫǰ ɫǴɫ

ǭǬɫDZ ɫǴǬ

ǭǬɫDz ɫdzDZ

*Rounded to the nearest million.

Source: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau website

EXHIBITŗŠ Top 10 U.S. Breweries in 2017

Rank Brewery

ɫ Anheuser-Busch, Inc

ǭ MillerCoors

Ǯ Constellation

ǯ Heineken

ǰ Pabst Brewing Company

DZ D.G. Yuengling and Son, Inc

Dz North American Breweries

dz Diageo

Ǵ Boston Beer Company

ɫǬ Sierra Nevada Brewing Company

Source: Brewers Association.

EXHIBITŗš Top 10 Global Beer

Producers by Volume,

2014–2016 (millions of

barrels)*

Rank Producer ǭǬɫǯ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDZ

ɫ Ab InBev** Ǯǰɫ ǮǰǮ ǯǮǰ

ǭ Heineken ɫdzǬ ɫdzDZ ɫǴǰ

Ǯ Carlsberg ɫɫǬ ɫǬDz ɫǬǭ

ǯ CR Snow*** N/A N/A ɫǬǬ

ǰ Molson Coors

Brewing Company

ǰǯ ǰǯ dzǭ

DZ Tsingtao (Group) Dzdz Dzǭ DZDz

Dz Asahi ǭDZ ǭǯ DZǬ

dz Beijing Yanjing ǯǰ ǯɫ Ǯdz

Ǵ Castel BGI ǭDZ ǭDZ ǭDZ

ɫǬ Kirin ǮDZ Ǯǰ ǭǯ

* Originally reported as hectoliters. Computed using ɫ hL = .dzǰǭ

barrel for comparison; to nearest million bbl.

** Now includes SABMiller; previous volumes for SABMiller in years

ǭǬɫǯ and ǭǬɫǰ prior to acquisition were ǭǯǴ and ǮǰǮ, respec-

tively, ranking it as second for both years.

*** Was not in top ɫǬ for ǭǬɫǯ and ǭǬɫǰ.

N/A: Not available.

Source: AB InBev ǭǬ-F SEC Document, ǭǬɫǰ, ǭǬɫDZ, ǭǬɫDz.

in 2017—nearly triple the number in 2012. Of these

breweries, 99 percent were identified as craft brewer-

ies with distribution ranging from local to national.

While large global breweries occupied the top posi-

tions among the largest U.S. breweries, three craft

breweries were ranked among the top-10 largest U.S.

brewers in 2017—see Exhibit 2. Exhibit 3 shows the

production volume of the 10 largest beer producers

worldwide from 2014 to 2016. The number of craft

breweries in each U.S. state in 2015 and 2017 are

presented in Exhibit 4.

THEŗBEERŗPRODUCTIONŗ

PROCESS

The beer production process involves the fermenta-

tion of grains. The cereal grain barley is the most

common grain used in the production of beer. Before

fermentation, however, barley must be malted and

milled. Malting allows the barley to germinate and

produce the sugars that would be fermented by the

yeast, yielding the sweetness of beer. By soaking the

barley in water, the barley germinates, or grows, as it

would when planted in the ground. This process is

halted through the introduction of hot air and drying

after germination began.

After malting, the barley is milled to break open

the husk while also cracking the inner seed that has

begun to germinate. Once milled, the barley is mashed,

or added to hot water. The addition of the hot water

produces sugar from the grain. This mixture is then

filtered, resulting in the wort. The wort is then boiled,

CASEƥƱ Competition in the Craft Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz C-43

which sterilizes the beer. It is at this stage that hops

are added. The taste and aroma of beer depend on the

variety of hops and when the hops were added.

After boiling, the wort is cooled and then poured

into the fermentor where yeast is added. The sugar

created in the previous stages is broken down by

the yeast through fermentation. The different styles

of beer depend on the type of yeast used, typically

either an ale or lager yeast. The time for this process

could take a couple of weeks to a couple of months.

After fermentation, the yeast is removed. The pro-

cess is completed after carbon dioxide is added and

the product is packaged.

Beer is a varied and differentiated product, with

over 70 styles in 15 categories. Each style is depen-

dent on a number of variables. These variables are

controlled by the brewer through the process, and

could include the origin of raw materials, approach to

fermentation, and yeast used. For example, Guinness

referenced on its website how barley purchased by

the brewer was not only grown locally, but was also

toasted specifically after malting, lending to its char-

acteristic taste and color. As another example of dif-

ferentiation through raw materials, wheat beers, such

as German-style hefeweizen, are brewed with a mini-

mum of 50 percent wheat instead of barley grain.

DEVELOPMENTŗOFŗ

MICROBREWERIESŗANDŗ

ECONOMICSŗOFŗSCALE

Although learning the art of brewing takes time,

beer production lends itself to scalability and vari-

ety. For example, an amateur; or home brewer; could

brew beer for home consumption. There had been

EXHIBITŗŢ Number of Craft Brewers

by State, 2015 and 2017

State ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDz

Alabama ǭǯ Ǯǯ

Alaska ǭDz ǮDZ

Arizona Dzdz ǴDZ

Arkansas ǭDZ Ǯǰ

California ǰɫdz DzDZǯ

Colorado ǭdzǯ Ǯǯdz

Connecticut Ǯǰ DZǬ

Delaware ɫǰ ǭɫ

Florida ɫǰɫ ǭǯǮ

Georgia ǯǰ DZǴ

Hawaii ɫǮ ɫdz

Idaho ǰǬ ǰǯ

Illinois ɫǰDz ǭǬǬ

Indiana ɫɫǰ ɫǮDz

Iowa ǰdz DzDZ

Kansas ǭDZ ǮDZ

Kentucky ǭǯ ǰǭ

Louisiana ǭǬ ǮǮ

Maine ǰǴ ǴǴ

Maryland DZǬ DzǮ

Massachusetts dzǯ ɫǭǴ

Michigan ǭǬǰ ǮǮǬ

Minnesota ɫǬǰ ɫǰdz

Mississippi dz ɫǭ

Missouri Dzɫ Ǵɫ

Montana ǯǴ Dzǰ

Nebraska ǮǮ ǯǴ

Nevada Ǯǯ ǯǬ

New Hampshire ǯǯ ǰdz

New Jersey ǰɫ ǴǬ

New Mexico ǯǰ DZDz

New York ǭǬdz ǮǭǴ

North Carolina ɫDZɫ ǭǰDz

North Dakota Ǵ ɫǭ

Ohio ɫǯǮ ǭǭǰ

Oklahoma ɫǯ ǭDz

Oregon ǭǭdz ǭDZDZ

Pennsylvania ɫDzdz ǭdzǭ

Rhode Island ɫǯ ɫDz

South Carolina ǮDZ DZɫ

South Dakota ɫǯ ɫDZ

Tennessee ǰǭ dzǭ

State ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDz

Texas ɫdzǴ ǭǰɫ

Utah ǭǭ ǮǬ

Vermont ǯǯ ǰǰ

Virginia ɫǭǯ ɫǴǬ

Washington ǮǬǰ ǮDZǴ

West Virginia ɫǭ ǭǮ

Wisconsin ɫǭɫ ɫDZǬ

Wyoming ǭǮ ǭǯ

Source: Brewers Association.

which sterilizes the beer. It is at this stage that hops

are added. The taste and aroma of beer depend on the

variety of hops and when the hops were added.

After boiling, the wort is cooled and then poured

into the fermentor where yeast is added. The sugar

created in the previous stages is broken down by

the yeast through fermentation. The different styles

of beer depend on the type of yeast used, typically

either an ale or lager yeast. The time for this process

could take a couple of weeks to a couple of months.

After fermentation, the yeast is removed. The pro-

cess is completed after carbon dioxide is added and

the product is packaged.

Beer is a varied and differentiated product, with

over 70 styles in 15 categories. Each style is depen-

dent on a number of variables. These variables are

controlled by the brewer through the process, and

could include the origin of raw materials, approach to

fermentation, and yeast used. For example, Guinness

referenced on its website how barley purchased by

the brewer was not only grown locally, but was also

toasted specifically after malting, lending to its char-

acteristic taste and color. As another example of dif-

ferentiation through raw materials, wheat beers, such

as German-style hefeweizen, are brewed with a mini-

mum of 50 percent wheat instead of barley grain.

DEVELOPMENTŗOFŗ

MICROBREWERIESŗANDŗ

ECONOMICSŗOFŗSCALE

Although learning the art of brewing takes time,

beer production lends itself to scalability and vari-

ety. For example, an amateur; or home brewer; could

brew beer for home consumption. There had been

EXHIBITŗŢ Number of Craft Brewers

by State, 2015 and 2017

State ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDz

Alabama ǭǯ Ǯǯ

Alaska ǭDz ǮDZ

Arizona Dzdz ǴDZ

Arkansas ǭDZ Ǯǰ

California ǰɫdz DzDZǯ

Colorado ǭdzǯ Ǯǯdz

Connecticut Ǯǰ DZǬ

Delaware ɫǰ ǭɫ

Florida ɫǰɫ ǭǯǮ

Georgia ǯǰ DZǴ

Hawaii ɫǮ ɫdz

Idaho ǰǬ ǰǯ

Illinois ɫǰDz ǭǬǬ

Indiana ɫɫǰ ɫǮDz

Iowa ǰdz DzDZ

Kansas ǭDZ ǮDZ

Kentucky ǭǯ ǰǭ

Louisiana ǭǬ ǮǮ

Maine ǰǴ ǴǴ

Maryland DZǬ DzǮ

Massachusetts dzǯ ɫǭǴ

Michigan ǭǬǰ ǮǮǬ

Minnesota ɫǬǰ ɫǰdz

Mississippi dz ɫǭ

Missouri Dzɫ Ǵɫ

Montana ǯǴ Dzǰ

Nebraska ǮǮ ǯǴ

Nevada Ǯǯ ǯǬ

New Hampshire ǯǯ ǰdz

New Jersey ǰɫ ǴǬ

New Mexico ǯǰ DZDz

New York ǭǬdz ǮǭǴ

North Carolina ɫDZɫ ǭǰDz

North Dakota Ǵ ɫǭ

Ohio ɫǯǮ ǭǭǰ

Oklahoma ɫǯ ǭDz

Oregon ǭǭdz ǭDZDZ

Pennsylvania ɫDzdz ǭdzǭ

Rhode Island ɫǯ ɫDz

South Carolina ǮDZ DZɫ

South Dakota ɫǯ ɫDZ

Tennessee ǰǭ dzǭ

State ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫDz

Texas ɫdzǴ ǭǰɫ

Utah ǭǭ ǮǬ

Vermont ǯǯ ǰǰ

Virginia ɫǭǯ ɫǴǬ

Washington ǮǬǰ ǮDZǴ

West Virginia ɫǭ ǭǮ

Wisconsin ɫǭɫ ɫDZǬ

Wyoming ǭǮ ǭǯ

Source: Brewers Association.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

C-44 PARTƥƮ Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

through kegs. While restaurants and bars could carry

kegs, retail shelves at a local liquor store needed to

have cans and bottles, as a relatively small number of

consumers could accommodate kegs for home use.

Thus, there may only be a few liquor stores or res-

taurants where a consumer may find a locally-brewed

beer. In states that do not allow self-distribution or

on-premise sales, distribution and exposure to con-

sumers could represent a barrier for breweries, espe-

cially those that were small or new.

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

(TTB) was the main federal agency for regulating this

industry. As another example of regulations, brewer-

ies, were required to have labels for beers approved by

the federal government, ensuring they meet advertis-

ing guidelines. In some instances, the TTB may need

to approve the formula used for brewing the specific

beer prior to the label receiving approval. Given the

approval process, and the growth of craft brewer-

ies, the length of time this takes could reach several

months. For a small, microbrewery first starting, the

delay in sales could potentially impact cash flow.

Employment law was another area impacting

breweries. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and

changes to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

greatly affected labor cost in the industry. Where the

ACA mandated health care coverage by employers,

the FLSA changed overtime rules for employees pre-

viously classified as exempt or salaried. Finally, many

states and municipalities passed or were considering

passing, increases to minimum wage. These changes

in regulations could lead to significant increases in

business costs, potentially impacting a brewery’s abil-

ity to remain viable or competitive.

Lawsuits might also impact breweries’ operations.

Trademark infringement lawsuits regarding brewery

and beer names were common. Further, food-related

lawsuits could occur. In 2017, there were potential

lawsuits against breweries distributing in California

that did not meet the May 2016 requirement of pro-

viding an additional sign warning against pregnancy

and BPA (Bisphenyl-A) consumption. BPA was com-

monly found in both cans and bottle caps, and thus

breweries were potentially legally exposed, exemplify-

ing the potential legal exposure to any brewery.

SUPPLIERSŗTOŗBREWERIES

The main suppliers to the industry were those who

supply grain and hops. Growers might sell direct to

a significant increase in the interest in home brew-

ing, with over 1 million people pursuing the hobby in

2016.7 It was also not uncommon for a home brewer

to venture into entrepreneurship and begin brewing

for commercial sales. However, beer production was

highly labor intensive with much of the work done

by hand. A certain level of production volume was

necessary to achieve breakeven and make the micro-

brewery a successful commercial operation.

A small nanobrewery may brew a variety of fla-

vor experiences and compete in niche markets, while

the macrobrewery may focus on economies of scale

and mass produce one style of beer. Both may attract

consumers across segments and were attributed to

the easily scalable yet highly variable process of brew-

ing beer. In contrast, a global producer such as AB

InBev could produce beer for millions of consumers

worldwide with factory-automated processes.

LEGALŗENVIRONMENTŗOFŗ

BREWERIES

As beer was an alcoholic beverage, the industry was

subject to much regulation. Further, these regula-

tions could vary by state and municipality. One such

regulation was regarding sales and distribution.

Distribution could be distinguished through

direct sales (or self-distribution), and two-tier and

three-tier systems. Regulations permitting direct sales

allow the brewery to sell directly to the consumer.

Growlers, bottle sales as well as tap rooms were all

forms of direct, or retail, sales. There were usually

requirements concerning direct sales, including limi-

tations on volume sold to the consumer.

Even where self-distribution was legal, the legal

volumes could be very small and limited. Very few

brewers were exempt from distributing through

wholesalers, referred to as a three-tier distribution

system. And often to be operationally viable, brewers

need access to this distribution system to generate

revenue. In a three-tier system, the brewery must first

sell to a wholesaler—the liquor or beer distributer.

This distributor then sells to the retailer, who then

ultimately sells to the consumer.

This distribution structure, however, had ramifi-

cations for the consumer, as much of what was avail-

able at retail outlets and restaurants were impacted by

the distributor. This was further impacted by whether

a brewery bottles or cans its beer or distributes

through kegs. While restaurants and bars could carry

kegs, retail shelves at a local liquor store needed to

have cans and bottles, as a relatively small number of

consumers could accommodate kegs for home use.

Thus, there may only be a few liquor stores or res-

taurants where a consumer may find a locally-brewed

beer. In states that do not allow self-distribution or

on-premise sales, distribution and exposure to con-

sumers could represent a barrier for breweries, espe-

cially those that were small or new.

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

(TTB) was the main federal agency for regulating this

industry. As another example of regulations, brewer-

ies, were required to have labels for beers approved by

the federal government, ensuring they meet advertis-

ing guidelines. In some instances, the TTB may need

to approve the formula used for brewing the specific

beer prior to the label receiving approval. Given the

approval process, and the growth of craft brewer-

ies, the length of time this takes could reach several

months. For a small, microbrewery first starting, the

delay in sales could potentially impact cash flow.

Employment law was another area impacting

breweries. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and

changes to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

greatly affected labor cost in the industry. Where the

ACA mandated health care coverage by employers,

the FLSA changed overtime rules for employees pre-

viously classified as exempt or salaried. Finally, many

states and municipalities passed or were considering

passing, increases to minimum wage. These changes

in regulations could lead to significant increases in

business costs, potentially impacting a brewery’s abil-

ity to remain viable or competitive.

Lawsuits might also impact breweries’ operations.

Trademark infringement lawsuits regarding brewery

and beer names were common. Further, food-related

lawsuits could occur. In 2017, there were potential

lawsuits against breweries distributing in California

that did not meet the May 2016 requirement of pro-

viding an additional sign warning against pregnancy

and BPA (Bisphenyl-A) consumption. BPA was com-

monly found in both cans and bottle caps, and thus

breweries were potentially legally exposed, exemplify-

ing the potential legal exposure to any brewery.

SUPPLIERSŗTOŗBREWERIES

The main suppliers to the industry were those who

supply grain and hops. Growers might sell direct to

a significant increase in the interest in home brew-

ing, with over 1 million people pursuing the hobby in

2016.7 It was also not uncommon for a home brewer

to venture into entrepreneurship and begin brewing

for commercial sales. However, beer production was

highly labor intensive with much of the work done

by hand. A certain level of production volume was

necessary to achieve breakeven and make the micro-

brewery a successful commercial operation.

A small nanobrewery may brew a variety of fla-

vor experiences and compete in niche markets, while

the macrobrewery may focus on economies of scale

and mass produce one style of beer. Both may attract

consumers across segments and were attributed to

the easily scalable yet highly variable process of brew-

ing beer. In contrast, a global producer such as AB

InBev could produce beer for millions of consumers

worldwide with factory-automated processes.

LEGALŗENVIRONMENTŗOFŗ

BREWERIES

As beer was an alcoholic beverage, the industry was

subject to much regulation. Further, these regula-

tions could vary by state and municipality. One such

regulation was regarding sales and distribution.

Distribution could be distinguished through

direct sales (or self-distribution), and two-tier and

three-tier systems. Regulations permitting direct sales

allow the brewery to sell directly to the consumer.

Growlers, bottle sales as well as tap rooms were all

forms of direct, or retail, sales. There were usually

requirements concerning direct sales, including limi-

tations on volume sold to the consumer.

Even where self-distribution was legal, the legal

volumes could be very small and limited. Very few

brewers were exempt from distributing through

wholesalers, referred to as a three-tier distribution

system. And often to be operationally viable, brewers

need access to this distribution system to generate

revenue. In a three-tier system, the brewery must first

sell to a wholesaler—the liquor or beer distributer.

This distributor then sells to the retailer, who then

ultimately sells to the consumer.

This distribution structure, however, had ramifi-

cations for the consumer, as much of what was avail-

able at retail outlets and restaurants were impacted by

the distributor. This was further impacted by whether

a brewery bottles or cans its beer or distributes

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CASEƥƱ Competition in the Craft Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz C-45

Yakima Valley was probably one of the more recogniz-

able geographic-growing regions. There were numer-

ous varieties of hops, however, and each contributes

a different aroma and flavor profile. Hop growers

have also trademarked names and varieties of hops.

Further, as with grains, some beer-styles require spe-

cific hops. Farmlands that were formerly known for

hops have started to see a rejuvenation of this crop,

such as in New England. In other areas, farmers were

introducing hops as a new, cash crop. Some hops

farms were also dual purpose, combining the grow-

ing operations with brewing, thus serving as both a

supplier of hops to breweries while also producing

their own beer for retail. Recent news reports, how-

ever, were citing current and future shortages of hops

due to the increased number of breweries. Rising

temperatures in Europe led to a diminished yield in

2015, further impacting hops supplies. For breweries

using recipes that require these specific hops, short-

ages could be detrimental to production. In some

instances, larger beer producers had vertically inte-

grated into hops farming to protect their supply.

Suppliers to the industry also include manufac-

turers and distributors of brewing equipment, such

as fermentation tanks and refrigeration equipment.

Purification equipment and testing tools were also

necessary, given the brewing process and the need to

ensure purity and safety of the product.

Depending on distribution and the distribution

channel, breweries might need bottling or canning

equipment. Thus, breweries might invest heavily in

automated bottling capabilities to expand capacity.

Recently, however, there had been shortages in the

16-ounce size of aluminum cans.

HOWŗBREWERIESŗCOMPETEŴŗ

INNOVATIONŗANDŗQUALITYŗ

VERSUSŗPRICE

The consumer might seek out a specific beer or

brewery’s name or purchase the lower-priced glob-

ally known brand. For some, beer drinking might

also be seasonal, as tastes change with the seasons.

Lighter beers were consumed in hotter months, while

heavier beers were consumed in the colder months.

Consumers might associate beer styles with the time

of year or season. Oktoberfest and German-style

beers were associated with fall, following the German-

traditional celebration of Oktoberfest. Finally, any

breweries or distribute through wholesalers. Brewers

who wish to produce a grain-specific beer would be

required to procure the specific grain. Further, reci-

pes might call for a variety of grains, including rye,

wheat, and corn. As previously mentioned, the defini-

tion of craft was changed not only to include a higher

threshold for annual production, but it also changed

to not exclude producers who used other grains, such

as corn, in their production. Finally, origin-specific

beers, such as German- or Belgian-styles might also

require specific grains.

The more specialized the grain or hop, the more

difficult it was to obtain. Those breweries, then,

competing based on specialized brewing would be

required to identify such suppliers. Conversely,

larger, global producers of single-style beers were

able to utilize economies of scale and demand lower

prices from suppliers. Organically-grown grains and

hops suppliers would also fall into this category of

providing specialized ingredients, and specialty brew-

ers tend to use such ingredients.

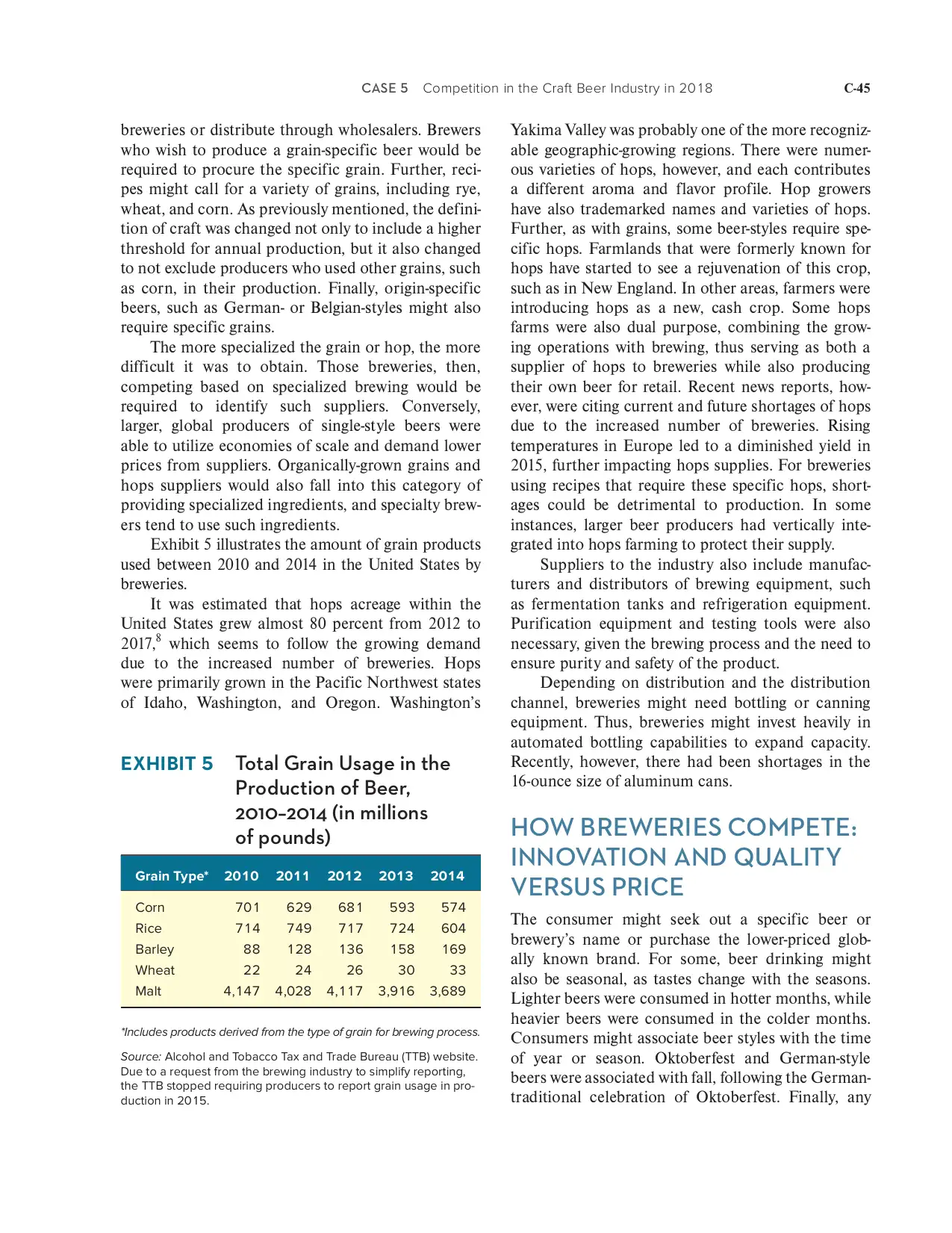

Exhibit 5 illustrates the amount of grain products

used between 2010 and 2014 in the United States by

breweries.

It was estimated that hops acreage within the

United States grew almost 80 percent from 2012 to

2017,8 which seems to follow the growing demand

due to the increased number of breweries. Hops

were primarily grown in the Pacific Northwest states

of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. Washington’s

EXHIBITŗţ Total Grain Usage in the

Production of Beer,

2010–2014 (in millions

of pounds)

Grain Type* ǭǬɫǬ ǭǬɫɫ ǭǬɫǭ ǭǬɫǮ ǭǬɫǯ

Corn DzǬɫ DZǭǴ DZdzɫ ǰǴǮ ǰDzǯ

Rice Dzɫǯ DzǯǴ DzɫDz Dzǭǯ DZǬǯ

Barley dzdz ɫǭdz ɫǮDZ ɫǰdz ɫDZǴ

Wheat ǭǭ ǭǯ ǭDZ ǮǬ ǮǮ

Malt ǯ,ɫǯDz ǯ,Ǭǭdz ǯ,ɫɫDz Ǯ,ǴɫDZ Ǯ,DZdzǴ

*Includes products derived from the type of grain for brewing process.

Source: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) website.

Due to a request from the brewing industry to simplify reporting,

the TTB stopped requiring producers to report grain usage in pro-

duction in ǭǬɫǰ.

Yakima Valley was probably one of the more recogniz-

able geographic-growing regions. There were numer-

ous varieties of hops, however, and each contributes

a different aroma and flavor profile. Hop growers

have also trademarked names and varieties of hops.

Further, as with grains, some beer-styles require spe-

cific hops. Farmlands that were formerly known for

hops have started to see a rejuvenation of this crop,

such as in New England. In other areas, farmers were

introducing hops as a new, cash crop. Some hops

farms were also dual purpose, combining the grow-

ing operations with brewing, thus serving as both a

supplier of hops to breweries while also producing

their own beer for retail. Recent news reports, how-

ever, were citing current and future shortages of hops

due to the increased number of breweries. Rising

temperatures in Europe led to a diminished yield in

2015, further impacting hops supplies. For breweries

using recipes that require these specific hops, short-

ages could be detrimental to production. In some

instances, larger beer producers had vertically inte-

grated into hops farming to protect their supply.

Suppliers to the industry also include manufac-

turers and distributors of brewing equipment, such

as fermentation tanks and refrigeration equipment.

Purification equipment and testing tools were also

necessary, given the brewing process and the need to

ensure purity and safety of the product.

Depending on distribution and the distribution

channel, breweries might need bottling or canning

equipment. Thus, breweries might invest heavily in

automated bottling capabilities to expand capacity.

Recently, however, there had been shortages in the

16-ounce size of aluminum cans.

HOWŗBREWERIESŗCOMPETEŴŗ

INNOVATIONŗANDŗQUALITYŗ

VERSUSŗPRICE

The consumer might seek out a specific beer or

brewery’s name or purchase the lower-priced glob-

ally known brand. For some, beer drinking might

also be seasonal, as tastes change with the seasons.

Lighter beers were consumed in hotter months, while

heavier beers were consumed in the colder months.

Consumers might associate beer styles with the time

of year or season. Oktoberfest and German-style

beers were associated with fall, following the German-

traditional celebration of Oktoberfest. Finally, any

breweries or distribute through wholesalers. Brewers

who wish to produce a grain-specific beer would be

required to procure the specific grain. Further, reci-

pes might call for a variety of grains, including rye,

wheat, and corn. As previously mentioned, the defini-

tion of craft was changed not only to include a higher

threshold for annual production, but it also changed

to not exclude producers who used other grains, such

as corn, in their production. Finally, origin-specific

beers, such as German- or Belgian-styles might also

require specific grains.

The more specialized the grain or hop, the more

difficult it was to obtain. Those breweries, then,

competing based on specialized brewing would be

required to identify such suppliers. Conversely,

larger, global producers of single-style beers were

able to utilize economies of scale and demand lower

prices from suppliers. Organically-grown grains and

hops suppliers would also fall into this category of

providing specialized ingredients, and specialty brew-

ers tend to use such ingredients.

Exhibit 5 illustrates the amount of grain products

used between 2010 and 2014 in the United States by

breweries.

It was estimated that hops acreage within the

United States grew almost 80 percent from 2012 to

2017,8 which seems to follow the growing demand

due to the increased number of breweries. Hops

were primarily grown in the Pacific Northwest states

of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. Washington’s

EXHIBITŗţ Total Grain Usage in the

Production of Beer,

2010–2014 (in millions

of pounds)

Grain Type* ǭǬɫǬ ǭǬɫɫ ǭǬɫǭ ǭǬɫǮ ǭǬɫǯ

Corn DzǬɫ DZǭǴ DZdzɫ ǰǴǮ ǰDzǯ

Rice Dzɫǯ DzǯǴ DzɫDz Dzǭǯ DZǬǯ

Barley dzdz ɫǭdz ɫǮDZ ɫǰdz ɫDZǴ

Wheat ǭǭ ǭǯ ǭDZ ǮǬ ǮǮ

Malt ǯ,ɫǯDz ǯ,Ǭǭdz ǯ,ɫɫDz Ǯ,ǴɫDZ Ǯ,DZdzǴ

*Includes products derived from the type of grain for brewing process.

Source: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) website.

Due to a request from the brewing industry to simplify reporting,

the TTB stopped requiring producers to report grain usage in pro-

duction in ǭǬɫǰ.

C-46 PARTƥƮ Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

increased significantly since 2006 following the rise

in craft beer popularity, competing against Boston

Beer Company’s Sam Adams in this better beer

segment. AB InBev had also acquired larger better-

known craft breweries, including Goose Island, in

2011. With a product portfolio that included both

low-price and premium craft beer brands, macro-

breweries were competing across the spectrum and

putting pressure on breweries within the better and

craft beer segments—segments demanding a higher

price point due to production.

However, a lawsuit claimed the marketing of Blue

Moon was misleading and its marketing obscured the

ownership structure. Although the case was dismissed,

it further illustrated consumer sentiment regarding

what was perceived as craft beer. It also illustrated the

power of marketing and how a macrobrewery might

position a brand within these segments.

CONSOLIDATIONSŗANDŗ

ACQUISITIONS

In 2015 AB InBev offered to purchase SABMiller for

$108 billion, which was approved by the European

Union in May 2016 and finalized in 2016. To allow

for the acquisition, many of SABMiller’s brands

were required to be divested. Asahi Group Holdings

Ltd. purchased the European brands Peroni and

Grolsch from SABMiller. Molson Coors purchased

SABMiller’s 58 percent ownership in MillCoors

LLC—originally a joint venture between Molson

Coors and SABMiller. This transaction provided

Molson Coors 100 percent ownership of MillerCoors.

It should be noted that AB InBev and MillerCoors

represented over 80 percent of the beer produced in

the United States for domestic consumption.

Purchases of craft breweries by larger companies

had also increased during the 2010s. AB InBev had

purchased around 10 craft breweries since 2011, includ-

ing Goose Island, Blue Point and Devil’s Backbone

Brewing. MillerCoors—whose brands already included

Killian’s Irish Red, Leinenkugel’s, and Foster’s—

acquired Saint Archer Brewing Company. Ballast Point

Brewing & Spirits was acquired by Constellations

Brands. Finally, Heineken NV purchased a stake in

Lagunitas Brewing Company. It would seem that craft

beer and breweries had not only obtained the atten-

tion of the consumer, but also the larger multinational

breweries and corporations.

one consumer might enjoy several styles, or choose to

be brewery or brand loyal.

The brewing process and the multiple varieties

and styles of beer allow for breweries to compete

across the strategy spectrum—low price and high

volume, or higher price and low volume. Industry

competitors, then, might target both price-point and

differentiation. The home brewer, who decided to

invest several thousand dollars in a small space to

produce very small quantities of their beer and start a

nanobrewery, might utilize a niche competitive strat-

egy. The consumer might patronize the brewery on

location or seek it out on tap at a restaurant given

the quality and the style of beer brewed. If allowed by

law, the brewery might offer tastings or sell onsite to

visitors. Further, the nanobrewer was free to explore

and experiment with unusual flavors. To drive aware-

ness, the brewer might enter competitions, attend

beer festivals, or host tastings and “tap takeovers”

at local restaurants. If successful, the brewer might

invest in larger facilities and equipment to increase

capacity with growing demand.

The larger, more established craft brewers, espe-

cially those considered regional breweries, might

compete through marketing and distribution, while

offering a higher value compared to the mass pro-

duction of macrobreweries. However, the consumer

might at times be sensitive to and desire the craft

beer experience through smaller breweries—so much

so that even craft breweries who by definition were

craft might draw the ire of the consumer due to its

size and scope. Boston Beer Company was one such

company. Even though James Koch had started it as

a microbrewery, pioneering the craft beer movement

in the 1980s, some craft beer consumers do not view

it as authentically craft.

Larger, macrobreweries mass produced and

competed using economies of scale and established

distribution systems. Thus, low cost preserves mar-

gins as lower price points drive volume sales. Many

of these brands were sold en masse at sporting and

entertainment venues, as well as larger restaurant

chains, driving volume sales.

Companies like AB InBev possessed brands

within the portfolio that were sold under the percep-

tion of craft beer, in what Boston Beer Company

deems the better beer category—beer with a higher

price point, but also of higher quality. For example,

Blue Moon, a Belgian-style wheat ale, was produced

by MillerCoors. Blue Moon’s market share had

increased significantly since 2006 following the rise

in craft beer popularity, competing against Boston

Beer Company’s Sam Adams in this better beer

segment. AB InBev had also acquired larger better-

known craft breweries, including Goose Island, in

2011. With a product portfolio that included both

low-price and premium craft beer brands, macro-

breweries were competing across the spectrum and

putting pressure on breweries within the better and

craft beer segments—segments demanding a higher

price point due to production.

However, a lawsuit claimed the marketing of Blue

Moon was misleading and its marketing obscured the

ownership structure. Although the case was dismissed,

it further illustrated consumer sentiment regarding

what was perceived as craft beer. It also illustrated the

power of marketing and how a macrobrewery might

position a brand within these segments.

CONSOLIDATIONSŗANDŗ

ACQUISITIONS

In 2015 AB InBev offered to purchase SABMiller for

$108 billion, which was approved by the European

Union in May 2016 and finalized in 2016. To allow

for the acquisition, many of SABMiller’s brands

were required to be divested. Asahi Group Holdings

Ltd. purchased the European brands Peroni and

Grolsch from SABMiller. Molson Coors purchased

SABMiller’s 58 percent ownership in MillCoors

LLC—originally a joint venture between Molson

Coors and SABMiller. This transaction provided

Molson Coors 100 percent ownership of MillerCoors.

It should be noted that AB InBev and MillerCoors

represented over 80 percent of the beer produced in

the United States for domestic consumption.

Purchases of craft breweries by larger companies

had also increased during the 2010s. AB InBev had

purchased around 10 craft breweries since 2011, includ-

ing Goose Island, Blue Point and Devil’s Backbone

Brewing. MillerCoors—whose brands already included

Killian’s Irish Red, Leinenkugel’s, and Foster’s—

acquired Saint Archer Brewing Company. Ballast Point

Brewing & Spirits was acquired by Constellations

Brands. Finally, Heineken NV purchased a stake in

Lagunitas Brewing Company. It would seem that craft

beer and breweries had not only obtained the atten-

tion of the consumer, but also the larger multinational

breweries and corporations.

one consumer might enjoy several styles, or choose to

be brewery or brand loyal.

The brewing process and the multiple varieties

and styles of beer allow for breweries to compete

across the strategy spectrum—low price and high

volume, or higher price and low volume. Industry

competitors, then, might target both price-point and

differentiation. The home brewer, who decided to

invest several thousand dollars in a small space to

produce very small quantities of their beer and start a

nanobrewery, might utilize a niche competitive strat-

egy. The consumer might patronize the brewery on

location or seek it out on tap at a restaurant given

the quality and the style of beer brewed. If allowed by

law, the brewery might offer tastings or sell onsite to

visitors. Further, the nanobrewer was free to explore

and experiment with unusual flavors. To drive aware-

ness, the brewer might enter competitions, attend

beer festivals, or host tastings and “tap takeovers”

at local restaurants. If successful, the brewer might

invest in larger facilities and equipment to increase

capacity with growing demand.

The larger, more established craft brewers, espe-

cially those considered regional breweries, might

compete through marketing and distribution, while

offering a higher value compared to the mass pro-

duction of macrobreweries. However, the consumer

might at times be sensitive to and desire the craft

beer experience through smaller breweries—so much

so that even craft breweries who by definition were

craft might draw the ire of the consumer due to its

size and scope. Boston Beer Company was one such

company. Even though James Koch had started it as

a microbrewery, pioneering the craft beer movement

in the 1980s, some craft beer consumers do not view

it as authentically craft.

Larger, macrobreweries mass produced and

competed using economies of scale and established

distribution systems. Thus, low cost preserves mar-

gins as lower price points drive volume sales. Many

of these brands were sold en masse at sporting and

entertainment venues, as well as larger restaurant

chains, driving volume sales.

Companies like AB InBev possessed brands

within the portfolio that were sold under the percep-

tion of craft beer, in what Boston Beer Company

deems the better beer category—beer with a higher

price point, but also of higher quality. For example,

Blue Moon, a Belgian-style wheat ale, was produced

by MillerCoors. Blue Moon’s market share had

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

CASEƥƱ Competition in the Craft Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz C-47

AB InBev invested heavily in sponsorships to

bolster marketing and brand recognition globally.

Budweiser planned to sponsor the 2018 and 2022

FIFA World Cups™, as it had sponsored the 2014

competition. Globally, the Budweiser brand expe-

rienced revenue growth of 4.1 percent, driven by

11 percent growth with sales outside of the United

States in 2017. Bud Light was the official sponsor of

the National Football League through 2022.

AB InBev had also actively acquired other brands

and breweries since the 1990s, including Labatt in

1995, Beck’s in 2002, Anheuser-Bush in 2008, and

Grupo Modelo in 2013. All of these acquisitions pro-

ceeded the SABMiller purchase. These acquisitions

provided AB InBev greater market share and penetra-

tion through combining marketing and operations to

all brands. The reacquisition of the Oriental Brewery

in 2014 was a good example of the potential syner-

gies garnered. Cass was the leading beer in Korea

and was produced by Oriental Brewery; however,

while Cass represented the local brand for AB InBev

in Korea, Hoegaarden was distributed in Korea,

along with the global brands of Budweiser, Corona,

and Stella Artois.

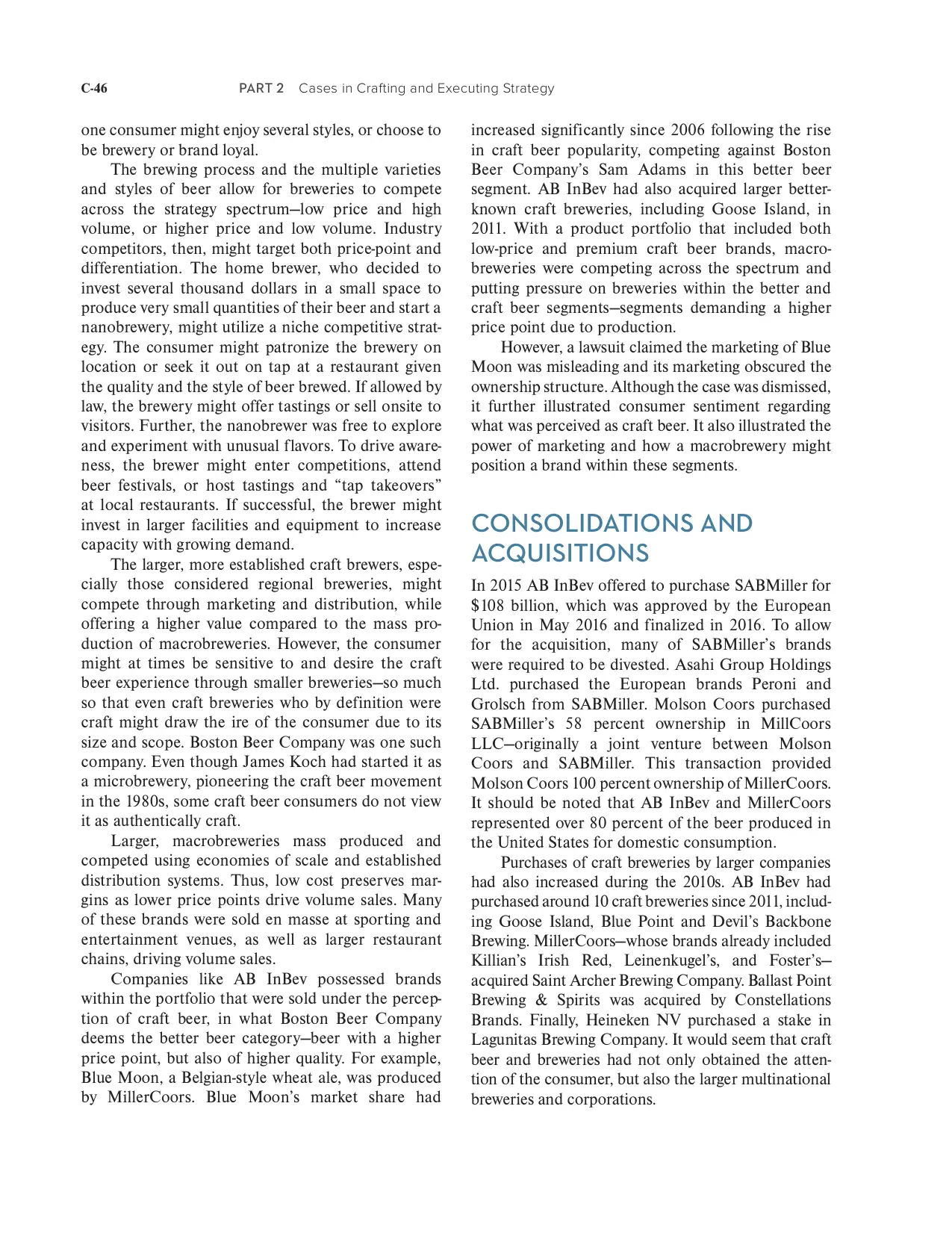

A summary of AB InBev’s financial performance

from 2014 to 2017 is presented in Exhibit 6.

Boston Beer Company

Boston Beer Company was the second largest craft

brewer by volume in the United States10 and reported

sales of less than 4 million barrels in 2017. The com-

pany’s 2017 sales volume declined by 6 percent from

2016, which was preceded by a decrease of over

5 percent from 2015 to 2016. Accordingly, it dropped

PROFILESŗOFŗBEERŗ

PRODUCERS

Anheuser-Busch InBev

As the world’s largest producer by volume, AB InBev

had 200,000 employees globally. The product port-

folio included the production, marketing, and dis-

tribution of over 500 beers, malt beverages, as well

as soft drinks in more than 150 countries. These

brands included Budweiser, Stella Artois, Leffe, and

Hoegaarden.

AB InBev managed its product portfolio through

three tiers. Global brands, such as Budweiser, Stella

Artois, and Corona, were distributed throughout the

world. International brands (Beck’s, Hoegaarden,

Leffe) were found in multiple countries. Local

champions (i.e., local brands) represented regional

or domestic brands acquired by AB InBev, such as

Goose Island in the United States and Cass in South

Korea. While some of the local brands were found in

different countries, it was due to geographic proxim-

ity and the potential to grow the brand larger.

AB InBev reported its 2017 revenues grew in all

its Latin America regions, Europe, Africa, and Asia,

but declined slightly in the United States and Canada.9

Its strength in brand recognition and focused market-

ing drove its global brands of Budweiser, Stella Artois,

and Corona to experience almost 10 percent revenue

growth. AB InBev had focused on growing brands out-

side of their respective home markets in 2017. Due to

this investment, Budweiser, Stella Artois, and Corona

experienced almost 17 percent revenue growth outside

of their home markets.

EXHIBITŗŤ Financial Summary for AB InBev, 2014–2017 (in millions of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $ ǰDZ,ǯǯǯ $ ǯǰ,ǰɫDz $ ǯǮ,DZǬǯ $ ǯDz,ǬDZǮ

Cost of sales (ǭɫ,ǮdzDZ) (ɫDz,dzǬǮ) (ɫDz,ɫǮDz) (ɫdz,DzǰDZ)

Gross Profit Ǯǰ,Ǭǰdz ǭDz,Dzɫǰ ǭDZ,ǯDZDz ǭdz,ǮǬDz

Selling, general and administrative expenses (ɫdz,ǬǴǴ) (ɫǰ,ɫDzɫ) (ɫǮ,DzǮǭ) (ɫǬ,ǭdzǰ)

Other operating income/expenses dzǰǯ DzǮǭ ɫ,ǬǮǭ ɫ,ǮdzDZ

Non-recurring items (DZDZǭ) (ǮǴǯ) ɫǮDZ (ɫǴDz)

Profit from operations (EBIT) ɫDz,ɫǰǭ ɫǭ,dzdzǭ ɫǮ,ǴǬǯ ɫǰ,ɫɫɫ

Depreciation, amortization and impairment ǯ,ǭDzDZ Ǯ,ǯDzǴ Ǯ,ɫǰǮ Ǯ,Ǯǰǯ

EBITDA $ ǭɫ,ǯǭǴ $ ɫDZ,ǮDZɫ $ ɫDz,ǬǰDz $ ɫdz,ǯDZǰ

Source: AB InBev Annual Reports, ǭǬɫǰ, ǭǬɫDZ, ǭǬɫDz.

AB InBev invested heavily in sponsorships to

bolster marketing and brand recognition globally.

Budweiser planned to sponsor the 2018 and 2022

FIFA World Cups™, as it had sponsored the 2014

competition. Globally, the Budweiser brand expe-

rienced revenue growth of 4.1 percent, driven by

11 percent growth with sales outside of the United

States in 2017. Bud Light was the official sponsor of

the National Football League through 2022.

AB InBev had also actively acquired other brands

and breweries since the 1990s, including Labatt in

1995, Beck’s in 2002, Anheuser-Bush in 2008, and

Grupo Modelo in 2013. All of these acquisitions pro-

ceeded the SABMiller purchase. These acquisitions

provided AB InBev greater market share and penetra-

tion through combining marketing and operations to

all brands. The reacquisition of the Oriental Brewery

in 2014 was a good example of the potential syner-

gies garnered. Cass was the leading beer in Korea

and was produced by Oriental Brewery; however,

while Cass represented the local brand for AB InBev

in Korea, Hoegaarden was distributed in Korea,

along with the global brands of Budweiser, Corona,

and Stella Artois.

A summary of AB InBev’s financial performance

from 2014 to 2017 is presented in Exhibit 6.

Boston Beer Company

Boston Beer Company was the second largest craft

brewer by volume in the United States10 and reported

sales of less than 4 million barrels in 2017. The com-

pany’s 2017 sales volume declined by 6 percent from

2016, which was preceded by a decrease of over

5 percent from 2015 to 2016. Accordingly, it dropped

PROFILESŗOFŗBEERŗ

PRODUCERS

Anheuser-Busch InBev

As the world’s largest producer by volume, AB InBev

had 200,000 employees globally. The product port-

folio included the production, marketing, and dis-

tribution of over 500 beers, malt beverages, as well

as soft drinks in more than 150 countries. These

brands included Budweiser, Stella Artois, Leffe, and

Hoegaarden.

AB InBev managed its product portfolio through

three tiers. Global brands, such as Budweiser, Stella

Artois, and Corona, were distributed throughout the

world. International brands (Beck’s, Hoegaarden,

Leffe) were found in multiple countries. Local

champions (i.e., local brands) represented regional

or domestic brands acquired by AB InBev, such as

Goose Island in the United States and Cass in South

Korea. While some of the local brands were found in

different countries, it was due to geographic proxim-

ity and the potential to grow the brand larger.

AB InBev reported its 2017 revenues grew in all

its Latin America regions, Europe, Africa, and Asia,

but declined slightly in the United States and Canada.9

Its strength in brand recognition and focused market-

ing drove its global brands of Budweiser, Stella Artois,

and Corona to experience almost 10 percent revenue

growth. AB InBev had focused on growing brands out-

side of their respective home markets in 2017. Due to

this investment, Budweiser, Stella Artois, and Corona

experienced almost 17 percent revenue growth outside

of their home markets.

EXHIBITŗŤ Financial Summary for AB InBev, 2014–2017 (in millions of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $ ǰDZ,ǯǯǯ $ ǯǰ,ǰɫDz $ ǯǮ,DZǬǯ $ ǯDz,ǬDZǮ

Cost of sales (ǭɫ,ǮdzDZ) (ɫDz,dzǬǮ) (ɫDz,ɫǮDz) (ɫdz,DzǰDZ)

Gross Profit Ǯǰ,Ǭǰdz ǭDz,Dzɫǰ ǭDZ,ǯDZDz ǭdz,ǮǬDz

Selling, general and administrative expenses (ɫdz,ǬǴǴ) (ɫǰ,ɫDzɫ) (ɫǮ,DzǮǭ) (ɫǬ,ǭdzǰ)

Other operating income/expenses dzǰǯ DzǮǭ ɫ,ǬǮǭ ɫ,ǮdzDZ

Non-recurring items (DZDZǭ) (ǮǴǯ) ɫǮDZ (ɫǴDz)

Profit from operations (EBIT) ɫDz,ɫǰǭ ɫǭ,dzdzǭ ɫǮ,ǴǬǯ ɫǰ,ɫɫɫ

Depreciation, amortization and impairment ǯ,ǭDzDZ Ǯ,ǯDzǴ Ǯ,ɫǰǮ Ǯ,Ǯǰǯ

EBITDA $ ǭɫ,ǯǭǴ $ ɫDZ,ǮDZɫ $ ɫDz,ǬǰDz $ ɫdz,ǯDZǰ

Source: AB InBev Annual Reports, ǭǬɫǰ, ǭǬɫDZ, ǭǬɫDz.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

C-48 PARTƥƮ Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

successful development and sales of beers under

the Traveler Beer Company brand. The incubator,

Alchemy and Science, also built Concrete Beach

Brewery and Coney Island Brewery. Alchemy and

Science contributed 7 percent of the total net sales in

2015 and 4 percent of net sales in 2016.

Boston Beer Company offered three non-beer

brands. The Twisted Tea brand was launched in 2001

and the Angry Orchard was originated in 2011. Truly

Spiked & Sparkling was a 5 percent alcohol sparkling

water launched in 2016. These other brands and

products compete in the flavored malt beverage and

the hard cider categories, respectively.

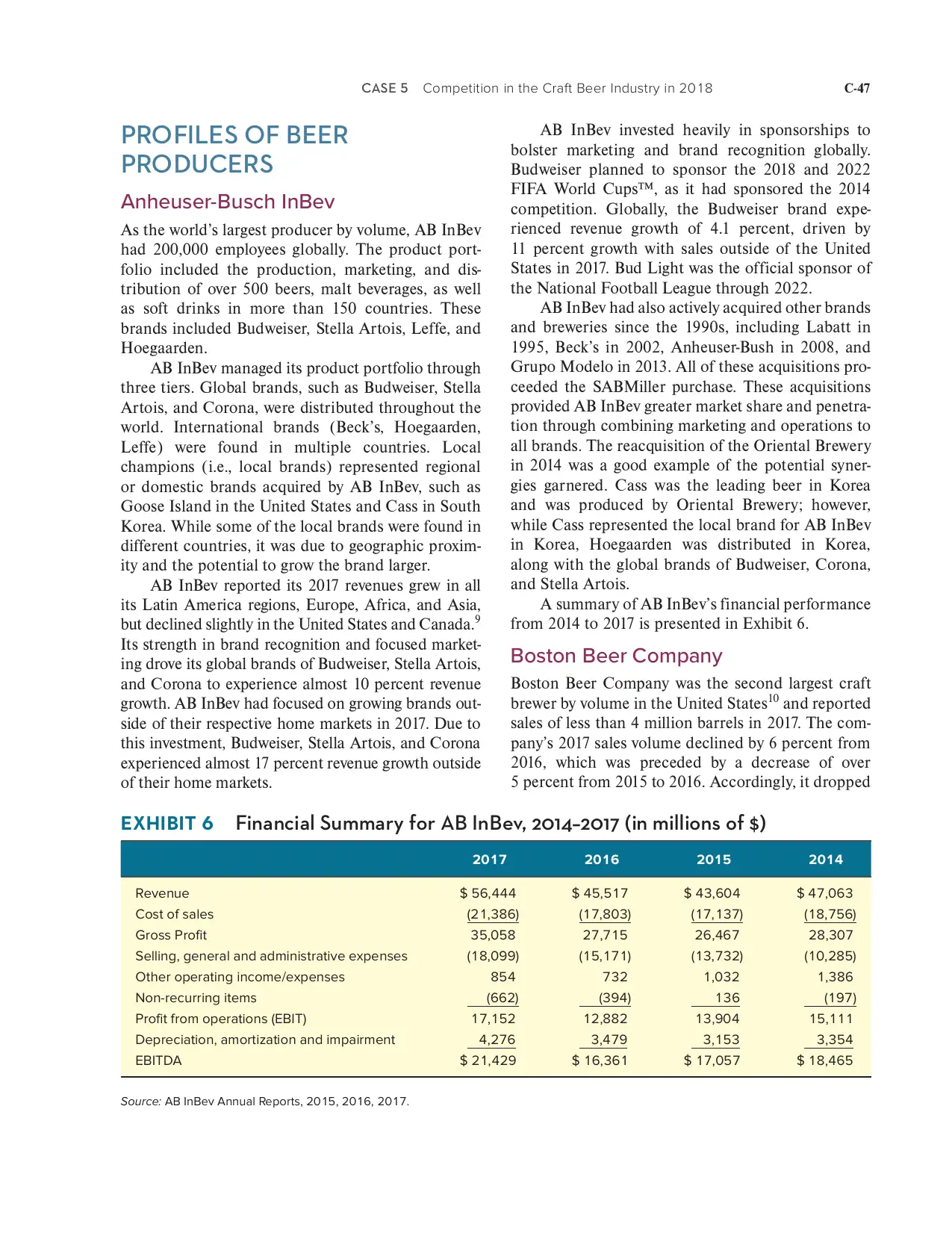

A summary of Boston Brewing Company’s finan-

cial performance from 2014 to 2017 is presented in

Exhibit 7.

Craft Brew Alliance

Craft Brew Alliance was ranked ninth for overall brew-

ing by volume in 2017.11 Founded in 2008, it resulted

from the mergers between Redhook Brewery, Widmer

Brothers Brewing, and Kona Brewing Company.

Each with substantial history, the decision to merge

was to help assist with growth and meeting demand.

The Craft Brew Alliance also included Omission

Brewery, Resignation Brewery, and Square Mile

Cider Company. In addition to these brands, Craft

Brew Alliance operated five brewpubs. In total, there

were 820 people employed at Craft Brew Alliance,

producing just over 1 million barrels in 2016.

from the fifth largest overall brewer in the United

States in 2015 to ninth in 2017—see Exhibit 2. The

company history states the recipe for Sam Adams

was actually company founder Jim Koch’s great-

great-grandfather’s recipe. The story of Boston Beer

Company and Jim Koch’s success was referenced at

times as the beginning of the craft beer movement,

often citing how Koch originally sold his beer to bars

with the beer and pitching on the spot.

This beginning seemed to underpin much of

Boston Beer Company’s strategy as it competed in

the higher value and higher price point category it

refers to as the better beer segment. Focusing on qual-

ity and taste, Boston Beer Company marketed Samuel

Adams Boston Lager as the original beer Koch first

discovered. The company also produced several Sam

Adams seasonal beers, such as Sam Adams Summer

Ale and Sam Adams Octoberfest. Other seasonal Sam

Adams beers have limited release in seasonal variety

packs, including Samuel Adams Harvest Pumpkin

and Samuel Adams Holiday Porter. In addition, there

was also a Samuel Adams Brewmaster’s Collection,

a much smaller, limited release set of beers at much

higher points, including the Small Batch Collection

and Barrel Room Collection. Utopia—its highest

priced beer—was branded as highly experimental and

under very limited release.

In the spirit of craft beer and innovation, several

years ago Boston Beer Company launched a craft

brew incubator as a subsidiary, which had led to the

EXHIBITŗť Financial Summary for Boston Brewing Company, 2014–2017

(in thousands of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $Ǵǭɫ,DzǮDZ $ǴDZdz,ǴǴǯ $ɫ,Ǭǭǯ,ǬǯǬ $ǴDZDZ,ǯDzdz

Excise taxes* (ǰdz,Dzǯǯ) (DZǭ,ǰǯdz) (DZǯ,ɫǬDZ) (DZǮ,ǯDzɫ)

Cost of goods sold (ǯɫǮ,ǬǴɫ) (ǯǯDZ,DzDzDZ) (ǯǰdz,ǮɫDz) (ǯǮDz,ǴǴDZ)

Gross Profit ǯǯǴ,ǴǬɫ ǯǰǴ,DZDzǬ ǰǬɫ,DZɫDz ǯDZǰ,Ǭɫɫ

Advertising, promotional and selling expenses ǭǰdz,DZǯǴ ǭǯǯ,ǭɫǮ ǭDzǮ,DZǭǴ ǭǰǬ,DZǴDZ

General and administrative expenses DzǮ,ɫǭDZ Dzdz,ǬǮǮ Dzɫ,ǰǰDZ DZǰ,ǴDzɫ

Impairment of assets ǭ,ǯǰɫ (ǭǮǰ) ǭǰdz ɫ,DzDzDz

Operating Income ɫɫǰ,DZDzǰ ɫǮDz,DZǰǴ ɫǰDZ,ɫDzǯ ɫǯDZ,ǰDZDz

Other expense, net ǯDZDz (ǰǮdz) (ɫ,ɫDZǯ) (ǴDzǮ)

Provision for income taxes ɫDz,ǬǴǮ ǯǴ,DzDzǭ ǰDZ,ǰǴDZ ǰǯ,dzǰɫ

Net Income $ ǴǴ,ǬǯǴ $ dzDz,ǮǯǴ $ Ǵdz,ǯɫǯ $ ǴǬ,DzǯǮ

Source: Boston Beer Company Annual Report, ǭǬɫDz.

successful development and sales of beers under

the Traveler Beer Company brand. The incubator,

Alchemy and Science, also built Concrete Beach

Brewery and Coney Island Brewery. Alchemy and

Science contributed 7 percent of the total net sales in

2015 and 4 percent of net sales in 2016.

Boston Beer Company offered three non-beer

brands. The Twisted Tea brand was launched in 2001

and the Angry Orchard was originated in 2011. Truly

Spiked & Sparkling was a 5 percent alcohol sparkling

water launched in 2016. These other brands and

products compete in the flavored malt beverage and

the hard cider categories, respectively.

A summary of Boston Brewing Company’s finan-

cial performance from 2014 to 2017 is presented in

Exhibit 7.

Craft Brew Alliance

Craft Brew Alliance was ranked ninth for overall brew-

ing by volume in 2017.11 Founded in 2008, it resulted

from the mergers between Redhook Brewery, Widmer

Brothers Brewing, and Kona Brewing Company.

Each with substantial history, the decision to merge

was to help assist with growth and meeting demand.

The Craft Brew Alliance also included Omission

Brewery, Resignation Brewery, and Square Mile

Cider Company. In addition to these brands, Craft

Brew Alliance operated five brewpubs. In total, there

were 820 people employed at Craft Brew Alliance,

producing just over 1 million barrels in 2016.

from the fifth largest overall brewer in the United

States in 2015 to ninth in 2017—see Exhibit 2. The

company history states the recipe for Sam Adams

was actually company founder Jim Koch’s great-

great-grandfather’s recipe. The story of Boston Beer

Company and Jim Koch’s success was referenced at

times as the beginning of the craft beer movement,

often citing how Koch originally sold his beer to bars

with the beer and pitching on the spot.

This beginning seemed to underpin much of

Boston Beer Company’s strategy as it competed in

the higher value and higher price point category it

refers to as the better beer segment. Focusing on qual-

ity and taste, Boston Beer Company marketed Samuel

Adams Boston Lager as the original beer Koch first

discovered. The company also produced several Sam

Adams seasonal beers, such as Sam Adams Summer

Ale and Sam Adams Octoberfest. Other seasonal Sam

Adams beers have limited release in seasonal variety

packs, including Samuel Adams Harvest Pumpkin

and Samuel Adams Holiday Porter. In addition, there

was also a Samuel Adams Brewmaster’s Collection,

a much smaller, limited release set of beers at much

higher points, including the Small Batch Collection

and Barrel Room Collection. Utopia—its highest

priced beer—was branded as highly experimental and

under very limited release.

In the spirit of craft beer and innovation, several

years ago Boston Beer Company launched a craft

brew incubator as a subsidiary, which had led to the

EXHIBITŗť Financial Summary for Boston Brewing Company, 2014–2017

(in thousands of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $Ǵǭɫ,DzǮDZ $ǴDZdz,ǴǴǯ $ɫ,Ǭǭǯ,ǬǯǬ $ǴDZDZ,ǯDzdz

Excise taxes* (ǰdz,Dzǯǯ) (DZǭ,ǰǯdz) (DZǯ,ɫǬDZ) (DZǮ,ǯDzɫ)

Cost of goods sold (ǯɫǮ,ǬǴɫ) (ǯǯDZ,DzDzDZ) (ǯǰdz,ǮɫDz) (ǯǮDz,ǴǴDZ)

Gross Profit ǯǯǴ,ǴǬɫ ǯǰǴ,DZDzǬ ǰǬɫ,DZɫDz ǯDZǰ,Ǭɫɫ

Advertising, promotional and selling expenses ǭǰdz,DZǯǴ ǭǯǯ,ǭɫǮ ǭDzǮ,DZǭǴ ǭǰǬ,DZǴDZ

General and administrative expenses DzǮ,ɫǭDZ Dzdz,ǬǮǮ Dzɫ,ǰǰDZ DZǰ,ǴDzɫ

Impairment of assets ǭ,ǯǰɫ (ǭǮǰ) ǭǰdz ɫ,DzDzDz

Operating Income ɫɫǰ,DZDzǰ ɫǮDz,DZǰǴ ɫǰDZ,ɫDzǯ ɫǯDZ,ǰDZDz

Other expense, net ǯDZDz (ǰǮdz) (ɫ,ɫDZǯ) (ǴDzǮ)

Provision for income taxes ɫDz,ǬǴǮ ǯǴ,DzDzǭ ǰDZ,ǰǴDZ ǰǯ,dzǰɫ

Net Income $ ǴǴ,ǬǯǴ $ dzDz,ǮǯǴ $ Ǵdz,ǯɫǯ $ ǴǬ,DzǯǮ

Source: Boston Beer Company Annual Report, ǭǬɫDz.

CASEƥƱ Competition in the Craft Beer Industry in ǭǬɫdz C-49

savings or solicited investments from friends and

family.

Given their entrepreneurial beginnings, these

microbreweries and even smaller nanobreweries

were usually located in industrial spaces. They were

solely operated by the brewer-turned-entrepreneur, or

a small staff of two or three. This staff would help

with brewing and production, as well as potentially

brewery tours and visits—probably the most common

marketing and consumer relations tactic utilized by

smaller breweries. While almost all breweries offered

tours and tastings, these became ever more critical to

the smaller brewery with limited capital for market-

ing and advertising. If onsite sales were available, the

brewer could sell growlers to visitors.

Social media websites also offered significant

exposure for free and had become a foundational ele-

ment of brewery marketing. These websites helped

the brewery reach the craft beer consumer, who

tended to seek out and follow new and upcoming

breweries. There were also mobile phone applica-

tions specific to the craft beer industry that could

help a startup gain exposure. Participating in craft

beer festivals, where local and regional breweries

were able to offer samples to attendees, was another

opportunity to gain exposure.

Some small microbreweries did not have enough

employees for bottling and labeling and had been

known to solicit volunteers through social media.

To gain exposure and boost sales, the brewery might

host events at local restaurants, such as tap-takeovers,

where several of its beers are featured on draft. If

Craft Brew Alliance utilized automated brewing

equipment and distributed nationally through the

Anheuser-Busch wholesaler network alliance, lever-

aging many of the logistics and thus cost advantages

associated. Yet, it remained independent, leveraging

both its craft brewery brands and the cost advantage

associated with larger distribution networks. It was

the only independent craft brewer to achieve this

relationship and sought to leverage the partnership to

distribute its products in international markets, lead-

ing to the beginning of Kona’s global distribution.

Craft Brew Alliance engaged in contract brewing—a

practice where spare capacity in production was uti-

lized to produce beer under contract for sale under a

different label or brand. In addition, it had partnerships

with retailers like Costco and Buffalo Wild Wings, gar-

nering further consumer exposure as well as sales.

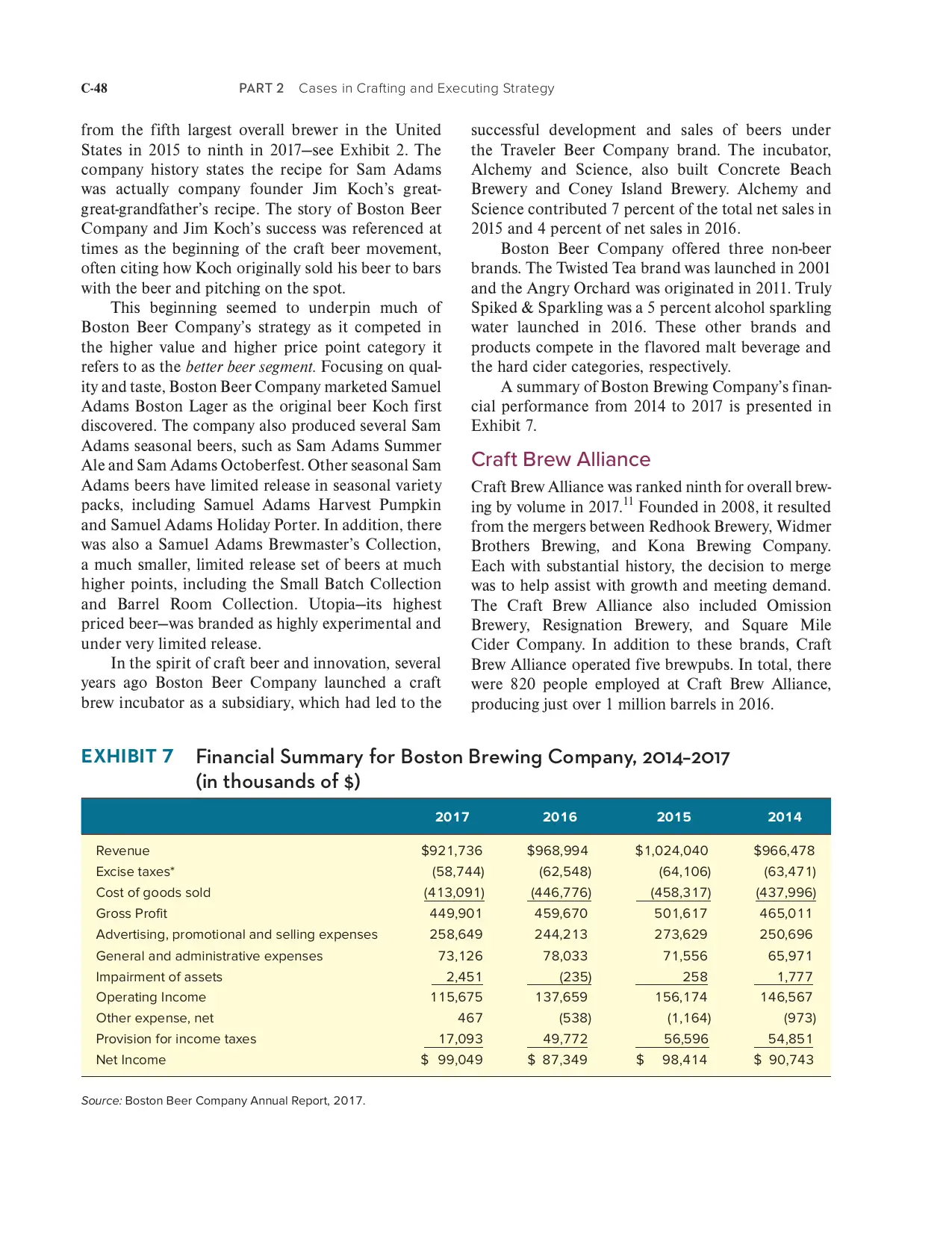

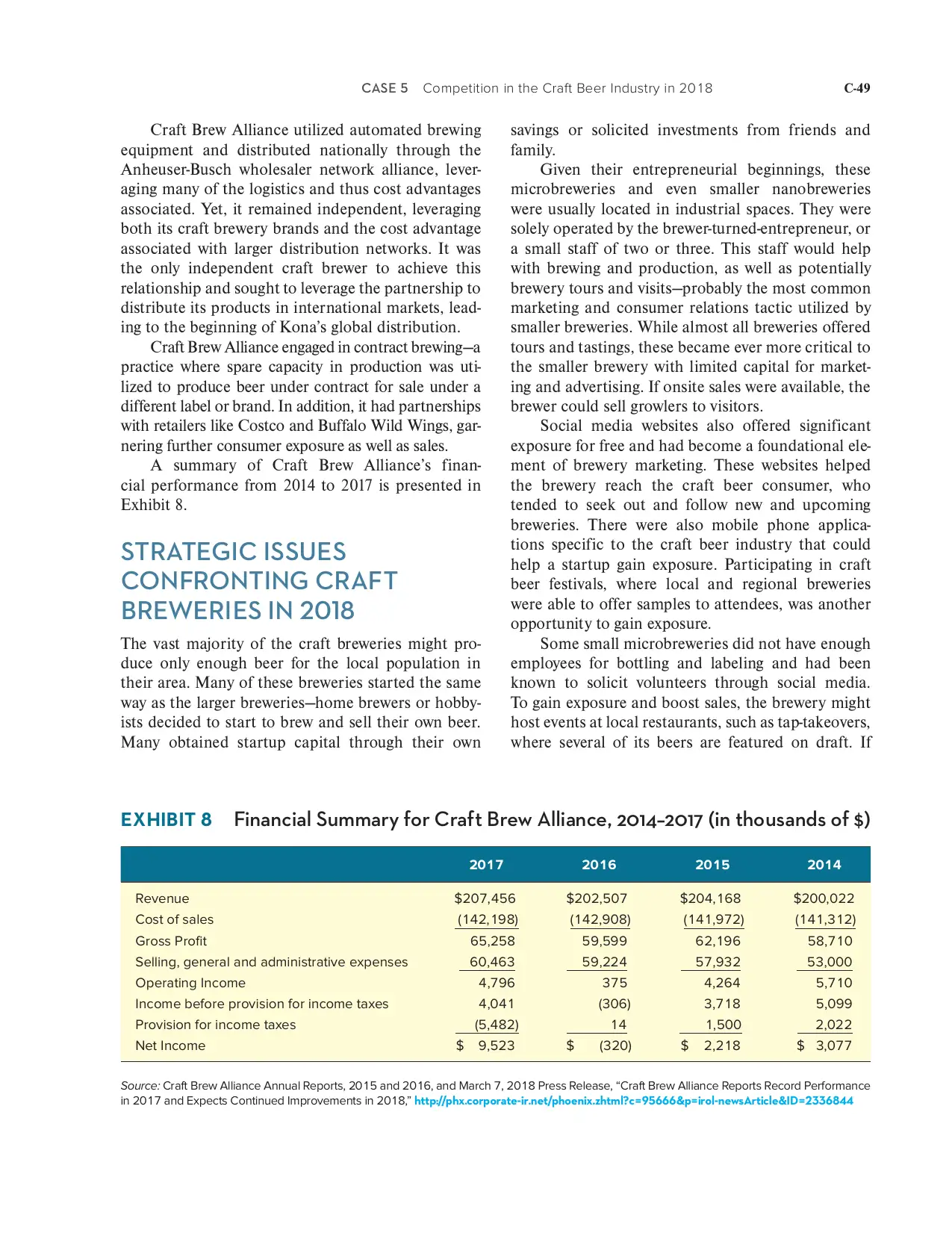

A summary of Craft Brew Alliance’s finan-

cial performance from 2014 to 2017 is presented in

Exhibit 8.

STRATEGICŗISSUESŗ

CONFRONTINGŗCRAFTŗ

BREWERIESŗINŗŠŞşŦ

The vast majority of the craft breweries might pro-

duce only enough beer for the local population in

their area. Many of these breweries started the same

way as the larger breweries—home brewers or hobby-

ists decided to start to brew and sell their own beer.

Many obtained startup capital through their own

EXHIBITŗŦ Financial Summary for Craft Brew Alliance, 2014–2017 (in thousands of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $ǭǬDz,ǯǰDZ $ǭǬǭ,ǰǬDz $ǭǬǯ,ɫDZdz $ǭǬǬ,Ǭǭǭ

Cost of sales (ɫǯǭ,ɫǴdz) (ɫǯǭ,ǴǬdz) (ɫǯɫ,ǴDzǭ) (ɫǯɫ,Ǯɫǭ)

Gross Profit DZǰ,ǭǰdz ǰǴ,ǰǴǴ DZǭ,ɫǴDZ ǰdz,DzɫǬ

Selling, general and administrative expenses DZǬ,ǯDZǮ ǰǴ,ǭǭǯ ǰDz,ǴǮǭ ǰǮ,ǬǬǬ

Operating Income ǯ,DzǴDZ ǮDzǰ ǯ,ǭDZǯ ǰ,DzɫǬ

Income before provision for income taxes ǯ,Ǭǯɫ (ǮǬDZ) Ǯ,Dzɫdz ǰ,ǬǴǴ

Provision for income taxes (ǰ,ǯdzǭ) ɫǯ ɫ,ǰǬǬ ǭ,Ǭǭǭ

Net Income $ Ǵ,ǰǭǮ $ (ǮǭǬ) $ ǭ,ǭɫdz $ Ǯ,ǬDzDz

Source: Craft Brew Alliance Annual Reports, ǭǬɫǰ and ǭǬɫDZ, and March Dz, ǭǬɫdz Press Release, “Craft Brew Alliance Reports Record Performance

in ǭǬɫDz and Expects Continued Improvements in ǭǬɫdz,” httpǂ//phxǀcorporateȟirǀnet/phoenixǀzhtml?cƼƵƱƲƲƲ&pƼirolȟnewsArticle&IDƼƮƯƯƲƴưư

savings or solicited investments from friends and

family.

Given their entrepreneurial beginnings, these

microbreweries and even smaller nanobreweries

were usually located in industrial spaces. They were

solely operated by the brewer-turned-entrepreneur, or

a small staff of two or three. This staff would help

with brewing and production, as well as potentially

brewery tours and visits—probably the most common

marketing and consumer relations tactic utilized by

smaller breweries. While almost all breweries offered

tours and tastings, these became ever more critical to

the smaller brewery with limited capital for market-

ing and advertising. If onsite sales were available, the

brewer could sell growlers to visitors.

Social media websites also offered significant

exposure for free and had become a foundational ele-

ment of brewery marketing. These websites helped

the brewery reach the craft beer consumer, who

tended to seek out and follow new and upcoming

breweries. There were also mobile phone applica-

tions specific to the craft beer industry that could

help a startup gain exposure. Participating in craft

beer festivals, where local and regional breweries

were able to offer samples to attendees, was another

opportunity to gain exposure.

Some small microbreweries did not have enough

employees for bottling and labeling and had been

known to solicit volunteers through social media.

To gain exposure and boost sales, the brewery might

host events at local restaurants, such as tap-takeovers,

where several of its beers are featured on draft. If

Craft Brew Alliance utilized automated brewing

equipment and distributed nationally through the

Anheuser-Busch wholesaler network alliance, lever-

aging many of the logistics and thus cost advantages

associated. Yet, it remained independent, leveraging

both its craft brewery brands and the cost advantage

associated with larger distribution networks. It was

the only independent craft brewer to achieve this

relationship and sought to leverage the partnership to

distribute its products in international markets, lead-

ing to the beginning of Kona’s global distribution.

Craft Brew Alliance engaged in contract brewing—a

practice where spare capacity in production was uti-

lized to produce beer under contract for sale under a

different label or brand. In addition, it had partnerships

with retailers like Costco and Buffalo Wild Wings, gar-

nering further consumer exposure as well as sales.

A summary of Craft Brew Alliance’s finan-

cial performance from 2014 to 2017 is presented in

Exhibit 8.

STRATEGICŗISSUESŗ

CONFRONTINGŗCRAFTŗ

BREWERIESŗINŗŠŞşŦ

The vast majority of the craft breweries might pro-

duce only enough beer for the local population in

their area. Many of these breweries started the same

way as the larger breweries—home brewers or hobby-

ists decided to start to brew and sell their own beer.

Many obtained startup capital through their own

EXHIBITŗŦ Financial Summary for Craft Brew Alliance, 2014–2017 (in thousands of $)

ǭǬɫDz ǭǬɫDZ ǭǬɫǰ ǭǬɫǯ

Revenue $ǭǬDz,ǯǰDZ $ǭǬǭ,ǰǬDz $ǭǬǯ,ɫDZdz $ǭǬǬ,Ǭǭǭ

Cost of sales (ɫǯǭ,ɫǴdz) (ɫǯǭ,ǴǬdz) (ɫǯɫ,ǴDzǭ) (ɫǯɫ,Ǯɫǭ)

Gross Profit DZǰ,ǭǰdz ǰǴ,ǰǴǴ DZǭ,ɫǴDZ ǰdz,DzɫǬ

Selling, general and administrative expenses DZǬ,ǯDZǮ ǰǴ,ǭǭǯ ǰDz,ǴǮǭ ǰǮ,ǬǬǬ

Operating Income ǯ,DzǴDZ ǮDzǰ ǯ,ǭDZǯ ǰ,DzɫǬ

Income before provision for income taxes ǯ,Ǭǯɫ (ǮǬDZ) Ǯ,Dzɫdz ǰ,ǬǴǴ

Provision for income taxes (ǰ,ǯdzǭ) ɫǯ ɫ,ǰǬǬ ǭ,Ǭǭǭ

Net Income $ Ǵ,ǰǭǮ $ (ǮǭǬ) $ ǭ,ǭɫdz $ Ǯ,ǬDzDz

Source: Craft Brew Alliance Annual Reports, ǭǬɫǰ and ǭǬɫDZ, and March Dz, ǭǬɫdz Press Release, “Craft Brew Alliance Reports Record Performance

in ǭǬɫDz and Expects Continued Improvements in ǭǬɫdz,” httpǂ//phxǀcorporateȟirǀnet/phoenixǀzhtml?cƼƵƱƲƲƲ&pƼirolȟnewsArticle&IDƼƮƯƯƲƴưư

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

C-50 PARTƥƮ Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy

of obtaining distribution and branding synergies,

while also mitigating the amount of direct competi-

tion. Complicating the competitive landscape were

increasing availability and price fluctuations of raw

materials. These sporadic shortages might impact the

industry’s growth and affect the production stability

of breweries, especially those smaller operations that

did not have capacity to purchase in bulk or outbid

larger competitors.