UCL Assignment: Critical Appraisal of Wakefield et al. (Lancet) Paper

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/03

|8

|6867

|79

Report

AI Summary

This report offers a critical appraisal of the Wakefield et al. paper, focusing on its relevance, originality, and research hypothesis. The analysis examines the paper's methodology, including the use of CASP checklists for qualitative research and randomized controlled trials. The appraisal assesses the study's validity, results, and local applicability, providing a systematic evaluation of the research. The report considers the importance of the topic, the study's originality, and the clarity of the research hypothesis. It evaluates the study's impact on healthcare and patient safety, highlighting the significance of critical appraisal in scientific publications. The report also includes an overview of the educational program that was conducted to improve patient safety culture. The study aimed to determine the effect of empowering nurses and supervisors through an educational program on patient safety culture in adult ICUs. The intervention consisted of a two-day workshop, hanging posters, and distributing pamphlets that covered topics such as patient safety, patient safety culture, speak up about safety issues, and the skills of Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

The effect of nurse empowerment

educationalprogram on patient safety

culture:a randomized controlled trial

Maryam Amiri1

, Zahra Khademian1* and Reza Nikandish2

Abstract

Background:The complexity of patients’condition and treatment processes in intensive care units (ICUs) predispo

patients to more hazardous events.Effective patient safety culture is related to lowering the rate of patients’

complications and fewer adverse events.The present study aimed to determine the effect of empowering nurses

and supervisors through an educationalprogram on patient safety culture in adult ICUs.

Methods:A randomized controlled trialwas conducted during April–September 2015 in 6 adult ICUs at Namazi

Hospital,Shiraz,Iran.A total of 60 nurses and 20 supervisors were selected through proportional stratified samp

census,respectively,and randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups.The intervention consisted of a

two-day workshop,hanging posters,and distributing pamphlets that covered topics such as patient safety,patient

safety culture,speak up about safety issues,and the skills of Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and

Patient Safety.Data were collected through a hospital survey on patient safety culture.Eventually,61 participants

completed the study.Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics,independent-samples t-test,paired-samples t-test,

and Chi-square test.P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: In the experimentalgroup,the totalpost-test mean scores of the patient safety culture (3.46 ± 0.26) was

significantly higher than that of the controlgroup (2.84 ± 0.37,P < 0.001).It was also higher than that of the pre-

test (2.91 ± 0.4,P < 0.001).Additionally,significant improvements were observed in 5 out of 12 dimensions in the

experimentalgroup.However,dimensions such as non-punitive response to errors and the events reported did

not improve significantly.

Conclusion:Empowering nurses and supervisors could improve the overallpatient safety culture.Nonetheless,

additional actions are required to improve areas such as reporting the events and non-punitive response to

Trial registration: IRCT2015053122494N1.Date registered:March 2,2016.

Keywords: Culture,Intensive care units,Nursing,Supervisory,Nurses,Patient safety,Patient safety culture,Safety

Background

Patient safetyis an importantelementin offering

high-qualityhealth careservices.However,it is esti-

mated that approximately 400,000 annualdeaths are re-

lated to preventableharms [1]. The complexityof

patients’condition and treatment processes in Intensive

Care Unit (ICU) predisposes patients to more hazardous

events [2].In a prospective study,during 2013–2014,the

rate ofadverse events per 1000 patient-days in an ICU

was 80.5 in which 45% were preventable [3].The epi-

demiology ofmedicalerrors in Iran is ambiguous.Zar-

garzadeh hasestimated that24,500 annualdeathsare

related to medicalerrors[4]. In addition,in an ICU,

among 307 medication doses,214 (69.7%)errors were

identified during administration (n = 132,42.99%),pre-

scription (n = 74,24.1%),and transcription (n = 8,2.61%)

of medications [5].Moreover,48 medication errors per

100 orders were observed in a pediatric ICU [6].

* Correspondence:Zahrakhademian@yahoo.com;khademian@sums.ac.ir;

zahrakhademian@gmail.com

1Department of Nursing,Schoolof Nursing and Midwifery,Shiraz University

of MedicalSciences,Shiraz,Iran

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1255-6

The effect of nurse empowerment

educationalprogram on patient safety

culture:a randomized controlled trial

Maryam Amiri1

, Zahra Khademian1* and Reza Nikandish2

Abstract

Background:The complexity of patients’condition and treatment processes in intensive care units (ICUs) predispo

patients to more hazardous events.Effective patient safety culture is related to lowering the rate of patients’

complications and fewer adverse events.The present study aimed to determine the effect of empowering nurses

and supervisors through an educationalprogram on patient safety culture in adult ICUs.

Methods:A randomized controlled trialwas conducted during April–September 2015 in 6 adult ICUs at Namazi

Hospital,Shiraz,Iran.A total of 60 nurses and 20 supervisors were selected through proportional stratified samp

census,respectively,and randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups.The intervention consisted of a

two-day workshop,hanging posters,and distributing pamphlets that covered topics such as patient safety,patient

safety culture,speak up about safety issues,and the skills of Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and

Patient Safety.Data were collected through a hospital survey on patient safety culture.Eventually,61 participants

completed the study.Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics,independent-samples t-test,paired-samples t-test,

and Chi-square test.P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: In the experimentalgroup,the totalpost-test mean scores of the patient safety culture (3.46 ± 0.26) was

significantly higher than that of the controlgroup (2.84 ± 0.37,P < 0.001).It was also higher than that of the pre-

test (2.91 ± 0.4,P < 0.001).Additionally,significant improvements were observed in 5 out of 12 dimensions in the

experimentalgroup.However,dimensions such as non-punitive response to errors and the events reported did

not improve significantly.

Conclusion:Empowering nurses and supervisors could improve the overallpatient safety culture.Nonetheless,

additional actions are required to improve areas such as reporting the events and non-punitive response to

Trial registration: IRCT2015053122494N1.Date registered:March 2,2016.

Keywords: Culture,Intensive care units,Nursing,Supervisory,Nurses,Patient safety,Patient safety culture,Safety

Background

Patient safetyis an importantelementin offering

high-qualityhealth careservices.However,it is esti-

mated that approximately 400,000 annualdeaths are re-

lated to preventableharms [1]. The complexityof

patients’condition and treatment processes in Intensive

Care Unit (ICU) predisposes patients to more hazardous

events [2].In a prospective study,during 2013–2014,the

rate ofadverse events per 1000 patient-days in an ICU

was 80.5 in which 45% were preventable [3].The epi-

demiology ofmedicalerrors in Iran is ambiguous.Zar-

garzadeh hasestimated that24,500 annualdeathsare

related to medicalerrors[4]. In addition,in an ICU,

among 307 medication doses,214 (69.7%)errors were

identified during administration (n = 132,42.99%),pre-

scription (n = 74,24.1%),and transcription (n = 8,2.61%)

of medications [5].Moreover,48 medication errors per

100 orders were observed in a pediatric ICU [6].

* Correspondence:Zahrakhademian@yahoo.com;khademian@sums.ac.ir;

zahrakhademian@gmail.com

1Department of Nursing,Schoolof Nursing and Midwifery,Shiraz University

of MedicalSciences,Shiraz,Iran

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1255-6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Poor communication and collaboration [7],lack of

knowledge,and inadequatetraining wereamongthe

main causes ofnursing errors in ICUs [8].Studies have

shown the lack ofcommunication skills in nurses and

nursing students [9,10].Hence,a training program for

nurses on patient safety alongside with strategies to im-

proveprofessionalcommunication isrequired to im-

prove patient safety.

High mortality and morbidity associated with medical

errors indicatethe importanceof promotingpatient

safety in critical care units.Nurses play a key role in im-

proving patientsafety due to their continuous presence

at patients’bedsides and interaction with their families

and otherhealthcareprofessionals[11].For instance,

criticalcare unitnurses have often reported thatthey

identified and corrected errors such as medication and

proceduralerrors related to nurses and other caregivers

[12].Henneman etal. identified multiple strategiesto

identify the patient,recognize other team members,and

the plan ofcare,which nurses used to detect,discon-

tinue,and correct errors in critical care settings [13].

Research findings indicated that a strong patient safety

culture is associated with a lower rate ofpatients’com-

plications and fewer adverse events [14,15].It is defined

as a culture whereby nurses are aware of errors and are

encouraged to discussthem.This, in turn, improves

their ability to learn from pastmistakes and take cor-

rective measures [16].

A meta-analysis,including 11 descriptive studieson

hospitalstaff,showed that only 8.3 and 32.3% of the re-

spondentsof the reviewed articleshave rated patient

safety culture in Iran as excellent and very good,respect-

ively [17].The importantrole of patientsafety culture

necessitates improvementof these strategies in clinical

settings.Nevertheless,interventionsthat may improve

patient safety culture are not adequately defined [18].In

a study,the positive effects ofsome interventions,such

as executive walk rounds[19] and the role of nurse

managersin regular assessmentand supportof the

safety culture were reported [20].Consequently,the par-

ticipation of nurse managers in the planning and imple-

mentationof strategies,to improve patient safety

culture,may reinforce these strategies [18].

Severalstudies have reported the effects ofnurse em-

powermentinterventionson patientsafety culture.A

type ofstrategy is an educationalprogram,such as on-

line module,addressing patientsafety which increases

positive scores ofnurses in two dimensions ofpatient

safety culture (i.e.“non-punitive response to errors” and

“frequency of event reporting”) [21].Teaching teamwork

also improves staff perception of patient safety culture in

the emergency department [22].Another empowerment

strategy is to encourage nurses to speak up.Sayre (2010)

reported thatnursesbehaviortowardspatientsafety

protection increased when encouraged to speak up in a

situation of a threat to patient safety [23].

In order to improve the quality ofcare and patient

safety,the Institute ofMedicine (2003)recommended a

reform in health profession education [24]. Accordingly,

the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) pro-

ject was introduced to train nurses on the required com-

petencies to improve the quality of care and patient safety

[25]. Considering the important role of nurses and leaders

in ensuring patient safety and in providing a strong patient

safety culture,we developed and studied the effects of an

innovative empowerment program on patient safety cul-

ture.This program is unique in a sense thatit involves

nurses and supervisors with an integrated exclusive educa-

tionalprogram which encourages them to speak up.The

present study aimed to determine the effect of empower-

ing nurses and supervisors through an educationalpro-

gram on patient safety culture in adult ICUs.

Methods

This randomized controlled trialwith a pre-testand

post-test control groups was conducted during

April–September2015 in 6 adult ICUs at Namazi

Hospital, Shiraz, Iran. All the above-mentioned ICUs were

similar in terms of patient safety policies. The study popu-

lation included 160 nurses and 20 supervisors. The nurse:-

patientratio in these wardswas 1:2.The sample size

consisted of60 nurses and 20 supervisors.The nurses

were selected based on proportionalstratified sampling.

Therefore,the number of selected nurses from each ICU

was proportionalto the total numberof its nurses.

Supervisors were nurses with atleasta Bachelor’s de-

gree and responsible for oversightnursing services in

the studied ICUs.Note that the supervisorsdid not

provide direct patient care.All supervisors at the hos-

pital participated in the study.To randomly allocate

nurses,a number was assigned to each ICU and catego-

rized into the controland experimentalgroups,based

on permuted block randomization.In total,30 nurses

from ICUs number 1,3, and 6 (surgical,neurosurgical,

and generalICU) were assigned to the experimental

group.In addition,30 nurses from ICUs number 2,4,

and 5 (medical,neurosurgical,and generalICU) were

assigned to thecontrol group. Based on permuted

block randomization,all supervisorsat the hospital

were assigned to the experimental(n = 10) and control

(n = 10)groups.The experimentalgroup,including 30

nurses (ICUs number 1,3, and 6)and 10 supervisors

received the educationalempowermentprogram.The

controlgroup included 30 nurses (ICUs number 2,4,

and 5) and 10 supervisorsthat did not receiveany

intervention.The inclusion criteria were having at least

6 monthsexperience in an adultICU and at leasta

Bachelor’sdegreein nursing. The exclusion criteria

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 2 of 8

knowledge,and inadequatetraining wereamongthe

main causes ofnursing errors in ICUs [8].Studies have

shown the lack ofcommunication skills in nurses and

nursing students [9,10].Hence,a training program for

nurses on patient safety alongside with strategies to im-

proveprofessionalcommunication isrequired to im-

prove patient safety.

High mortality and morbidity associated with medical

errors indicatethe importanceof promotingpatient

safety in critical care units.Nurses play a key role in im-

proving patientsafety due to their continuous presence

at patients’bedsides and interaction with their families

and otherhealthcareprofessionals[11].For instance,

criticalcare unitnurses have often reported thatthey

identified and corrected errors such as medication and

proceduralerrors related to nurses and other caregivers

[12].Henneman etal. identified multiple strategiesto

identify the patient,recognize other team members,and

the plan ofcare,which nurses used to detect,discon-

tinue,and correct errors in critical care settings [13].

Research findings indicated that a strong patient safety

culture is associated with a lower rate ofpatients’com-

plications and fewer adverse events [14,15].It is defined

as a culture whereby nurses are aware of errors and are

encouraged to discussthem.This, in turn, improves

their ability to learn from pastmistakes and take cor-

rective measures [16].

A meta-analysis,including 11 descriptive studieson

hospitalstaff,showed that only 8.3 and 32.3% of the re-

spondentsof the reviewed articleshave rated patient

safety culture in Iran as excellent and very good,respect-

ively [17].The importantrole of patientsafety culture

necessitates improvementof these strategies in clinical

settings.Nevertheless,interventionsthat may improve

patient safety culture are not adequately defined [18].In

a study,the positive effects ofsome interventions,such

as executive walk rounds[19] and the role of nurse

managersin regular assessmentand supportof the

safety culture were reported [20].Consequently,the par-

ticipation of nurse managers in the planning and imple-

mentationof strategies,to improve patient safety

culture,may reinforce these strategies [18].

Severalstudies have reported the effects ofnurse em-

powermentinterventionson patientsafety culture.A

type ofstrategy is an educationalprogram,such as on-

line module,addressing patientsafety which increases

positive scores ofnurses in two dimensions ofpatient

safety culture (i.e.“non-punitive response to errors” and

“frequency of event reporting”) [21].Teaching teamwork

also improves staff perception of patient safety culture in

the emergency department [22].Another empowerment

strategy is to encourage nurses to speak up.Sayre (2010)

reported thatnursesbehaviortowardspatientsafety

protection increased when encouraged to speak up in a

situation of a threat to patient safety [23].

In order to improve the quality ofcare and patient

safety,the Institute ofMedicine (2003)recommended a

reform in health profession education [24]. Accordingly,

the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) pro-

ject was introduced to train nurses on the required com-

petencies to improve the quality of care and patient safety

[25]. Considering the important role of nurses and leaders

in ensuring patient safety and in providing a strong patient

safety culture,we developed and studied the effects of an

innovative empowerment program on patient safety cul-

ture.This program is unique in a sense thatit involves

nurses and supervisors with an integrated exclusive educa-

tionalprogram which encourages them to speak up.The

present study aimed to determine the effect of empower-

ing nurses and supervisors through an educationalpro-

gram on patient safety culture in adult ICUs.

Methods

This randomized controlled trialwith a pre-testand

post-test control groups was conducted during

April–September2015 in 6 adult ICUs at Namazi

Hospital, Shiraz, Iran. All the above-mentioned ICUs were

similar in terms of patient safety policies. The study popu-

lation included 160 nurses and 20 supervisors. The nurse:-

patientratio in these wardswas 1:2.The sample size

consisted of60 nurses and 20 supervisors.The nurses

were selected based on proportionalstratified sampling.

Therefore,the number of selected nurses from each ICU

was proportionalto the total numberof its nurses.

Supervisors were nurses with atleasta Bachelor’s de-

gree and responsible for oversightnursing services in

the studied ICUs.Note that the supervisorsdid not

provide direct patient care.All supervisors at the hos-

pital participated in the study.To randomly allocate

nurses,a number was assigned to each ICU and catego-

rized into the controland experimentalgroups,based

on permuted block randomization.In total,30 nurses

from ICUs number 1,3, and 6 (surgical,neurosurgical,

and generalICU) were assigned to the experimental

group.In addition,30 nurses from ICUs number 2,4,

and 5 (medical,neurosurgical,and generalICU) were

assigned to thecontrol group. Based on permuted

block randomization,all supervisorsat the hospital

were assigned to the experimental(n = 10) and control

(n = 10)groups.The experimentalgroup,including 30

nurses (ICUs number 1,3, and 6)and 10 supervisors

received the educationalempowermentprogram.The

controlgroup included 30 nurses (ICUs number 2,4,

and 5) and 10 supervisorsthat did not receiveany

intervention.The inclusion criteria were having at least

6 monthsexperience in an adultICU and at leasta

Bachelor’sdegreein nursing. The exclusion criteria

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 2 of 8

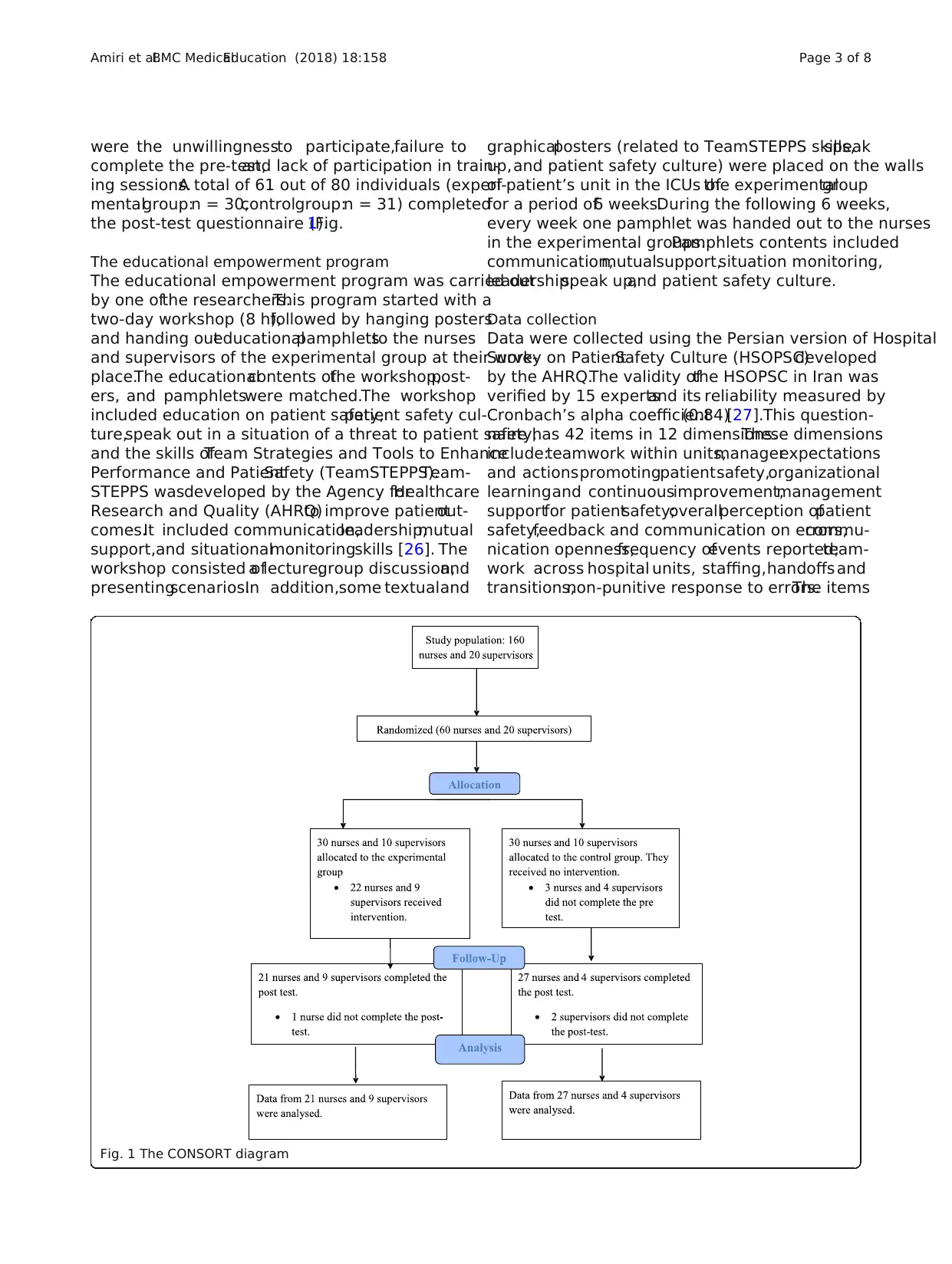

were the unwillingnessto participate,failure to

complete the pre-test,and lack of participation in train-

ing sessions.A total of 61 out of 80 individuals (experi-

mentalgroup:n = 30,controlgroup:n = 31) completed

the post-test questionnaire (Fig.1).

The educational empowerment program

The educational empowerment program was carried out

by one ofthe researchers.This program started with a

two-day workshop (8 h),followed by hanging posters

and handing outeducationalpamphletsto the nurses

and supervisors of the experimental group at their work-

place.The educationalcontents ofthe workshop,post-

ers, and pamphletswere matched.The workshop

included education on patient safety,patient safety cul-

ture,speak out in a situation of a threat to patient safety,

and the skills ofTeam Strategies and Tools to Enhance

Performance and PatientSafety (TeamSTEPPS).Team-

STEPPS wasdeveloped by the Agency forHealthcare

Research and Quality (AHRQ)to improve patientout-

comes.It included communication,leadership,mutual

support,and situationalmonitoringskills [26]. The

workshop consisted ofa lecture,group discussion,and

presentingscenarios.In addition,some textualand

graphicalposters (related to TeamSTEPPS skills,speak

up,and patient safety culture) were placed on the walls

of patient’s unit in the ICUs ofthe experimentalgroup

for a period of6 weeks.During the following 6 weeks,

every week one pamphlet was handed out to the nurses

in the experimental groups.Pamphlets contents included

communication,mutualsupport,situation monitoring,

leadership,speak up,and patient safety culture.

Data collection

Data were collected using the Persian version of Hospital

Survey on PatientSafety Culture (HSOPSC)developed

by the AHRQ.The validity ofthe HSOPSC in Iran was

verified by 15 expertsand its reliability measured by

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient(0.84)[27].This question-

naire has 42 items in 12 dimensions.These dimensions

include:teamwork within units,managerexpectations

and actionspromotingpatientsafety,organizational

learningand continuousimprovement,management

supportfor patientsafety;overallperception ofpatient

safety,feedback and communication on errors,commu-

nication openness,frequency ofevents reported;team-

work across hospital units, staffing,handoffs and

transitions,non-punitive response to errors.The items

Fig. 1 The CONSORT diagram

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 3 of 8

complete the pre-test,and lack of participation in train-

ing sessions.A total of 61 out of 80 individuals (experi-

mentalgroup:n = 30,controlgroup:n = 31) completed

the post-test questionnaire (Fig.1).

The educational empowerment program

The educational empowerment program was carried out

by one ofthe researchers.This program started with a

two-day workshop (8 h),followed by hanging posters

and handing outeducationalpamphletsto the nurses

and supervisors of the experimental group at their work-

place.The educationalcontents ofthe workshop,post-

ers, and pamphletswere matched.The workshop

included education on patient safety,patient safety cul-

ture,speak out in a situation of a threat to patient safety,

and the skills ofTeam Strategies and Tools to Enhance

Performance and PatientSafety (TeamSTEPPS).Team-

STEPPS wasdeveloped by the Agency forHealthcare

Research and Quality (AHRQ)to improve patientout-

comes.It included communication,leadership,mutual

support,and situationalmonitoringskills [26]. The

workshop consisted ofa lecture,group discussion,and

presentingscenarios.In addition,some textualand

graphicalposters (related to TeamSTEPPS skills,speak

up,and patient safety culture) were placed on the walls

of patient’s unit in the ICUs ofthe experimentalgroup

for a period of6 weeks.During the following 6 weeks,

every week one pamphlet was handed out to the nurses

in the experimental groups.Pamphlets contents included

communication,mutualsupport,situation monitoring,

leadership,speak up,and patient safety culture.

Data collection

Data were collected using the Persian version of Hospital

Survey on PatientSafety Culture (HSOPSC)developed

by the AHRQ.The validity ofthe HSOPSC in Iran was

verified by 15 expertsand its reliability measured by

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient(0.84)[27].This question-

naire has 42 items in 12 dimensions.These dimensions

include:teamwork within units,managerexpectations

and actionspromotingpatientsafety,organizational

learningand continuousimprovement,management

supportfor patientsafety;overallperception ofpatient

safety,feedback and communication on errors,commu-

nication openness,frequency ofevents reported;team-

work across hospital units, staffing,handoffs and

transitions,non-punitive response to errors.The items

Fig. 1 The CONSORT diagram

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 3 of 8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

were answered on a five-pointLikertscale,from com-

pletely disagree (1) to completely agree (5) or from never

(1) to always (5).There were a few negatively worded

items in the questionnaire thatwere reverse coded.If

the proportion of respondentswho answered “com-

pletely agree”/“agree”,or “always”/“most of the time” on

each item was more than 50%,this was considered as

strong,otherwise (below 50%) as the weak point ofthe

safety culture.In addition to these 42 questions,there

was a single item on patientsafety grading in the unit.

This item was answered on a five-point Likert scale from

excellent(score = 5)to failing (score = 1)and was ana-

lyzed separately as a single item [20,28].The pre-test

was completed individually before the workshop.Three

months after the workshop,the post-test was conducted

individually in both groups.

Data analysis

Statisticalanalysis was carried outusing the SPSS soft-

ware version 18.0. The results of One-Sample

Kolmogorov-Smirnovshowednormal distributionof

data before (P = 0.72)and after (P = 0.96)the interven-

tion,except for the single item on patient safety grading.

Descriptive statistics was used to describe age,sex,edu-

cation,position,and the total scores of the patient safety

culture and its dimensions.To compare the mean scores

between thetwo groupsand within each group,the

independent-samplest-test and paired-samplest-test

were used.The single item on patient safety grading was

compared between the controland experimentalgroups

using the Mann-Whitney test.This item was compared

before and after the intervention in each group using the

Wilcoxon test.The effect size for paired t-test was calcu-

lated by the Cohen (1988) equation as follows:

Effect size ¼ d ¼

M1‐M2

S pooled

; Spooled¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

S12 þ S22

2

r

Where M1 and M2 are post-test means of the experi-

mental and control groups,respectively.Spooled:Pooled

standard deviation,and S1 and S2:Post-teststandard

deviationsof the experimentaland control groups,

respectively.

The effectsize of 0.2,0.5,and 0.8 wasconsidered

small,medium,and large,respectively [29].P < 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

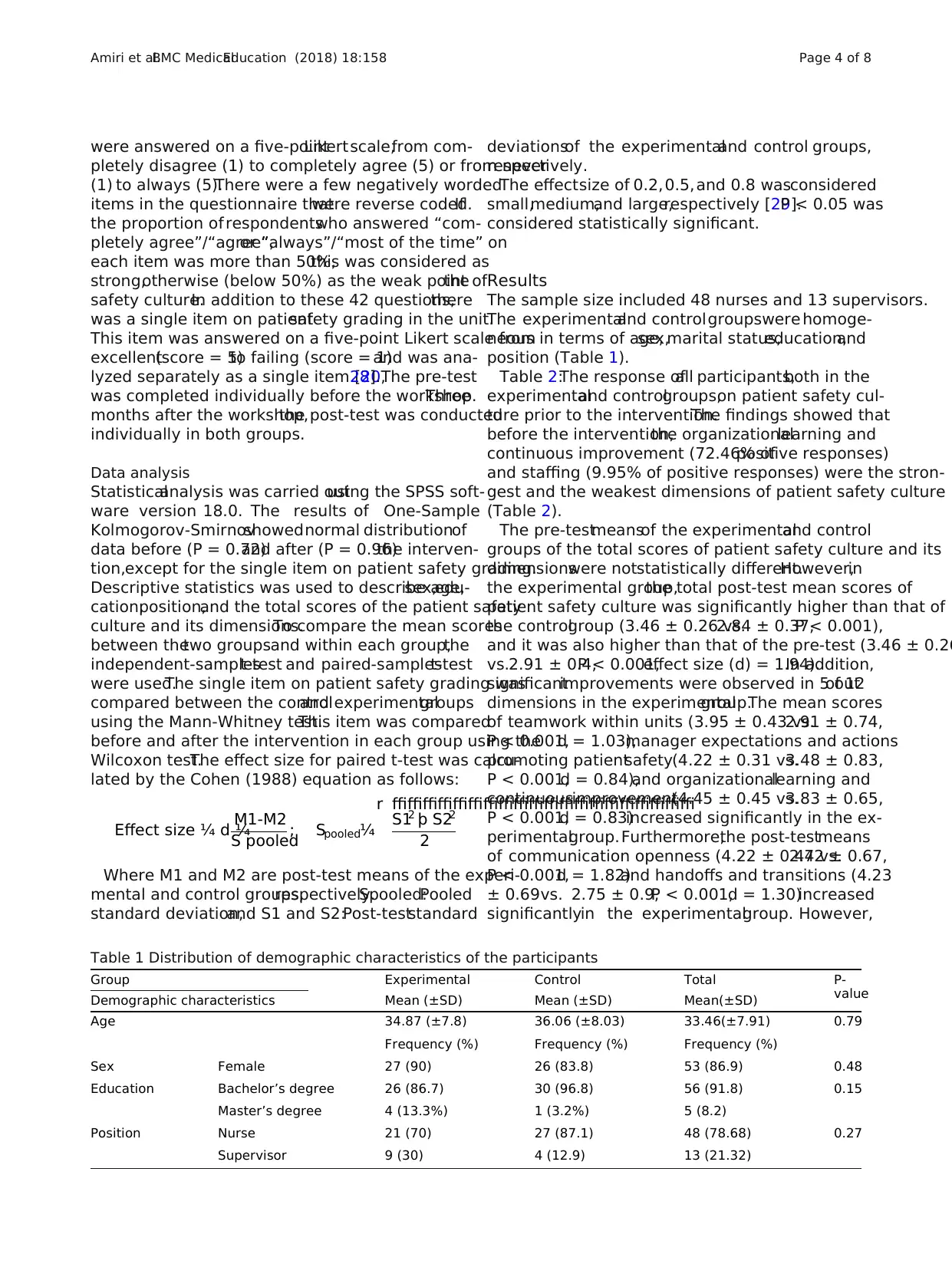

The sample size included 48 nurses and 13 supervisors.

The experimentaland controlgroupswere homoge-

neous in terms of age,sex,marital status,education,and

position (Table 1).

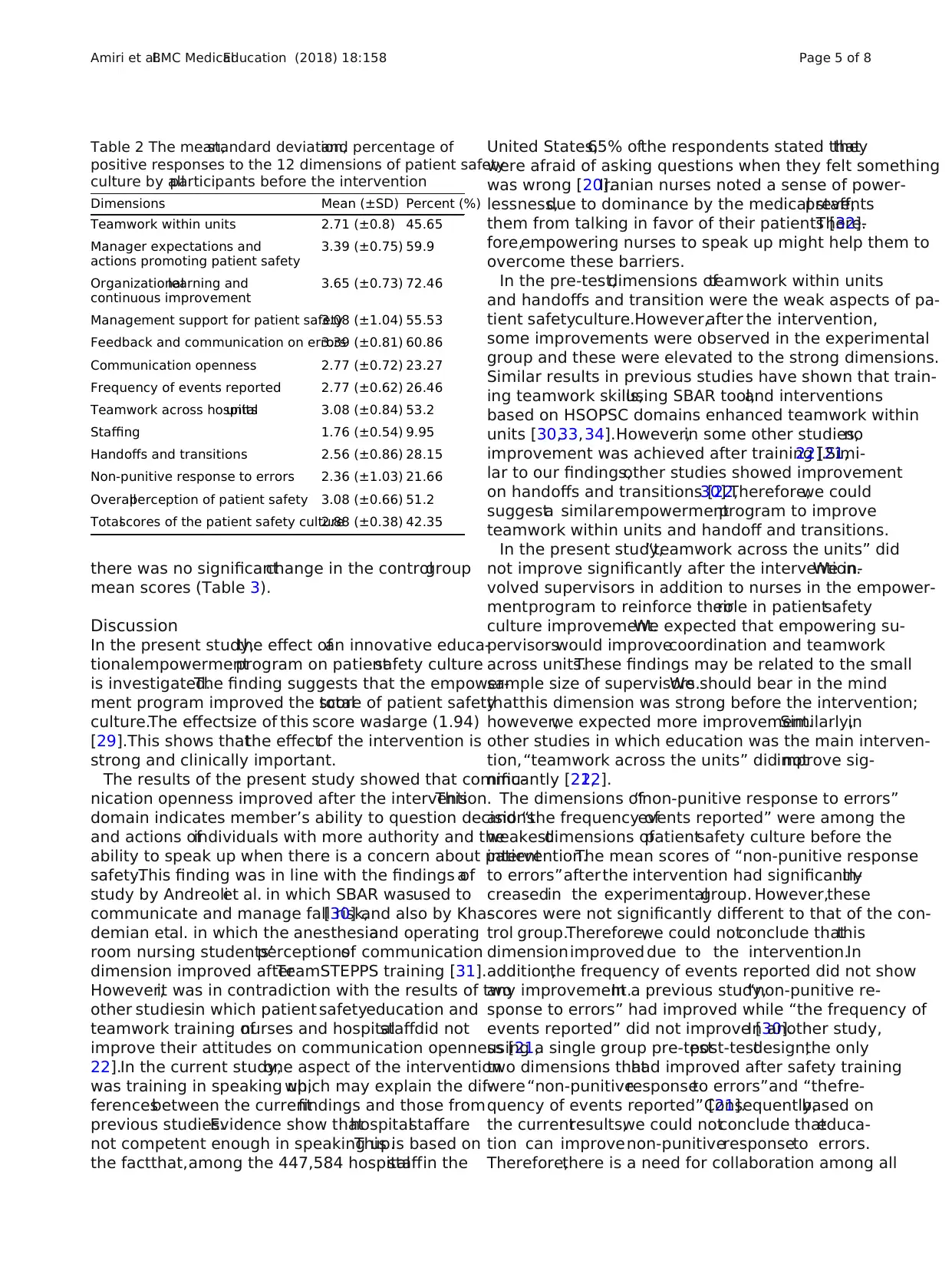

Table 2:The response ofall participants,both in the

experimentaland controlgroups,on patient safety cul-

ture prior to the intervention.The findings showed that

before the intervention,the organizationallearning and

continuous improvement (72.46% ofpositive responses)

and staffing (9.95% of positive responses) were the stron-

gest and the weakest dimensions of patient safety culture

(Table 2).

The pre-testmeansof the experimentaland control

groups of the total scores of patient safety culture and its

dimensionswere notstatistically different.However,in

the experimental group,the total post-test mean scores of

patient safety culture was significantly higher than that of

the controlgroup (3.46 ± 0.26 vs.2.84 ± 0.37,P < 0.001),

and it was also higher than that of the pre-test (3.46 ± 0.26

vs.2.91 ± 0.4,P < 0.001,effect size (d) = 1.94).In addition,

significantimprovements were observed in 5 outof 12

dimensions in the experimentalgroup.The mean scores

of teamwork within units (3.95 ± 0.43 vs.2.91 ± 0.74,

P < 0.001,d = 1.03),manager expectations and actions

promoting patientsafety(4.22 ± 0.31 vs.3.48 ± 0.83,

P < 0.001,d = 0.84),and organizationallearning and

continuousimprovement(4.45 ± 0.45 vs.3.83 ± 0.65,

P < 0.001,d = 0.83)increased significantly in the ex-

perimentalgroup.Furthermore,the post-testmeans

of communication openness (4.22 ± 0.44 vs.2.72 ± 0.67,

P < 0.001,d = 1.82)and handoffs and transitions (4.23

± 0.69vs. 2.75 ± 0.9,P < 0.001,d = 1.30)increased

significantlyin the experimentalgroup. However,

Table 1 Distribution of demographic characteristics of the participants

Group Experimental Control Total P-

value

Demographic characteristics Mean (±SD) Mean (±SD) Mean(±SD)

Age 34.87 (±7.8) 36.06 (±8.03) 33.46(±7.91) 0.79

Frequency (%) Frequency (%) Frequency (%)

Sex Female 27 (90) 26 (83.8) 53 (86.9) 0.48

Education Bachelor’s degree 26 (86.7) 30 (96.8) 56 (91.8) 0.15

Master’s degree 4 (13.3%) 1 (3.2%) 5 (8.2)

Position Nurse 21 (70) 27 (87.1) 48 (78.68) 0.27

Supervisor 9 (30) 4 (12.9) 13 (21.32)

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 4 of 8

pletely disagree (1) to completely agree (5) or from never

(1) to always (5).There were a few negatively worded

items in the questionnaire thatwere reverse coded.If

the proportion of respondentswho answered “com-

pletely agree”/“agree”,or “always”/“most of the time” on

each item was more than 50%,this was considered as

strong,otherwise (below 50%) as the weak point ofthe

safety culture.In addition to these 42 questions,there

was a single item on patientsafety grading in the unit.

This item was answered on a five-point Likert scale from

excellent(score = 5)to failing (score = 1)and was ana-

lyzed separately as a single item [20,28].The pre-test

was completed individually before the workshop.Three

months after the workshop,the post-test was conducted

individually in both groups.

Data analysis

Statisticalanalysis was carried outusing the SPSS soft-

ware version 18.0. The results of One-Sample

Kolmogorov-Smirnovshowednormal distributionof

data before (P = 0.72)and after (P = 0.96)the interven-

tion,except for the single item on patient safety grading.

Descriptive statistics was used to describe age,sex,edu-

cation,position,and the total scores of the patient safety

culture and its dimensions.To compare the mean scores

between thetwo groupsand within each group,the

independent-samplest-test and paired-samplest-test

were used.The single item on patient safety grading was

compared between the controland experimentalgroups

using the Mann-Whitney test.This item was compared

before and after the intervention in each group using the

Wilcoxon test.The effect size for paired t-test was calcu-

lated by the Cohen (1988) equation as follows:

Effect size ¼ d ¼

M1‐M2

S pooled

; Spooled¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

S12 þ S22

2

r

Where M1 and M2 are post-test means of the experi-

mental and control groups,respectively.Spooled:Pooled

standard deviation,and S1 and S2:Post-teststandard

deviationsof the experimentaland control groups,

respectively.

The effectsize of 0.2,0.5,and 0.8 wasconsidered

small,medium,and large,respectively [29].P < 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

The sample size included 48 nurses and 13 supervisors.

The experimentaland controlgroupswere homoge-

neous in terms of age,sex,marital status,education,and

position (Table 1).

Table 2:The response ofall participants,both in the

experimentaland controlgroups,on patient safety cul-

ture prior to the intervention.The findings showed that

before the intervention,the organizationallearning and

continuous improvement (72.46% ofpositive responses)

and staffing (9.95% of positive responses) were the stron-

gest and the weakest dimensions of patient safety culture

(Table 2).

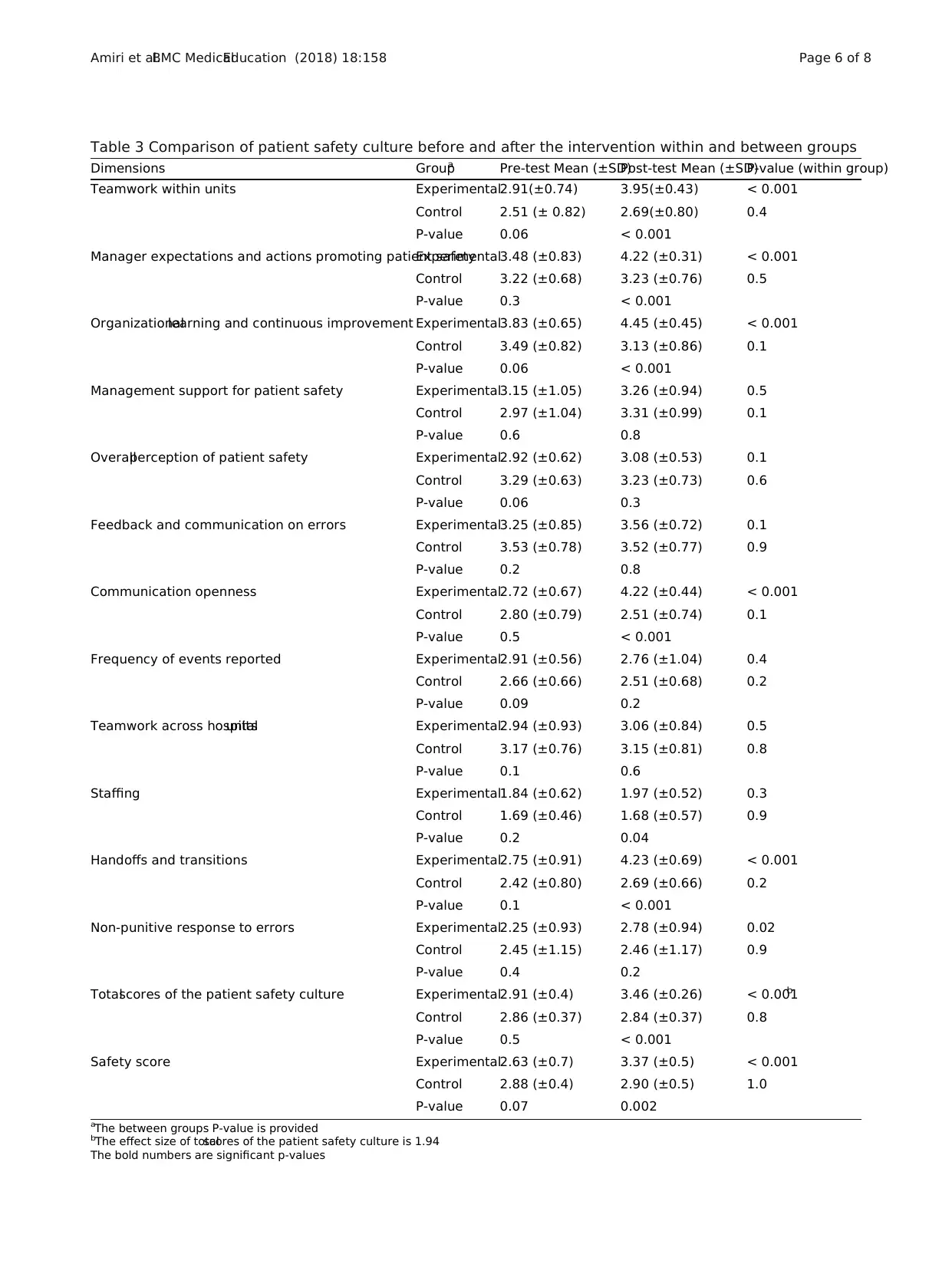

The pre-testmeansof the experimentaland control

groups of the total scores of patient safety culture and its

dimensionswere notstatistically different.However,in

the experimental group,the total post-test mean scores of

patient safety culture was significantly higher than that of

the controlgroup (3.46 ± 0.26 vs.2.84 ± 0.37,P < 0.001),

and it was also higher than that of the pre-test (3.46 ± 0.26

vs.2.91 ± 0.4,P < 0.001,effect size (d) = 1.94).In addition,

significantimprovements were observed in 5 outof 12

dimensions in the experimentalgroup.The mean scores

of teamwork within units (3.95 ± 0.43 vs.2.91 ± 0.74,

P < 0.001,d = 1.03),manager expectations and actions

promoting patientsafety(4.22 ± 0.31 vs.3.48 ± 0.83,

P < 0.001,d = 0.84),and organizationallearning and

continuousimprovement(4.45 ± 0.45 vs.3.83 ± 0.65,

P < 0.001,d = 0.83)increased significantly in the ex-

perimentalgroup.Furthermore,the post-testmeans

of communication openness (4.22 ± 0.44 vs.2.72 ± 0.67,

P < 0.001,d = 1.82)and handoffs and transitions (4.23

± 0.69vs. 2.75 ± 0.9,P < 0.001,d = 1.30)increased

significantlyin the experimentalgroup. However,

Table 1 Distribution of demographic characteristics of the participants

Group Experimental Control Total P-

value

Demographic characteristics Mean (±SD) Mean (±SD) Mean(±SD)

Age 34.87 (±7.8) 36.06 (±8.03) 33.46(±7.91) 0.79

Frequency (%) Frequency (%) Frequency (%)

Sex Female 27 (90) 26 (83.8) 53 (86.9) 0.48

Education Bachelor’s degree 26 (86.7) 30 (96.8) 56 (91.8) 0.15

Master’s degree 4 (13.3%) 1 (3.2%) 5 (8.2)

Position Nurse 21 (70) 27 (87.1) 48 (78.68) 0.27

Supervisor 9 (30) 4 (12.9) 13 (21.32)

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 4 of 8

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

there was no significantchange in the controlgroup

mean scores (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study,the effect ofan innovative educa-

tionalempowermentprogram on patientsafety culture

is investigated.The finding suggests that the empower-

ment program improved the totalscore of patient safety

culture.The effectsize of this score waslarge (1.94)

[29].This shows thatthe effectof the intervention is

strong and clinically important.

The results of the present study showed that commu-

nication openness improved after the intervention.This

domain indicates member’s ability to question decisions

and actions ofindividuals with more authority and the

ability to speak up when there is a concern about patient

safety.This finding was in line with the findings ofa

study by Andreoliet al. in which SBAR wasused to

communicate and manage fall risk,[30] and also by Kha-

demian etal. in which the anesthesiaand operating

room nursing students’perceptionsof communication

dimension improved afterTeamSTEPPS training [31].

However,it was in contradiction with the results of two

other studiesin which patient safetyeducation and

teamwork training ofnurses and hospitalstaffdid not

improve their attitudes on communication openness [21,

22].In the current study,one aspect of the intervention

was training in speaking up,which may explain the dif-

ferencesbetween the currentfindings and those from

previous studies.Evidence show thathospitalstaffare

not competent enough in speaking up.This is based on

the factthat,among the 447,584 hospitalstaffin the

United States,65% ofthe respondents stated thatthey

were afraid of asking questions when they felt something

was wrong [20].Iranian nurses noted a sense of power-

lessness,due to dominance by the medical staff,prevents

them from talking in favor of their patients [32].There-

fore,empowering nurses to speak up might help them to

overcome these barriers.

In the pre-test,dimensions ofteamwork within units

and handoffs and transition were the weak aspects of pa-

tient safetyculture.However,after the intervention,

some improvements were observed in the experimental

group and these were elevated to the strong dimensions.

Similar results in previous studies have shown that train-

ing teamwork skills,using SBAR tool,and interventions

based on HSOPSC domains enhanced teamwork within

units [30,33,34].However,in some other studies,no

improvement was achieved after training [21,22].Simi-

lar to our findings,other studies showed improvement

on handoffs and transitions [22,30].Therefore,we could

suggesta similarempowermentprogram to improve

teamwork within units and handoff and transitions.

In the present study,“teamwork across the units” did

not improve significantly after the intervention.We in-

volved supervisors in addition to nurses in the empower-

mentprogram to reinforce theirrole in patientsafety

culture improvement.We expected that empowering su-

pervisorswould improvecoordination and teamwork

across units.These findings may be related to the small

sample size of supervisors.We should bear in the mind

thatthis dimension was strong before the intervention;

however,we expected more improvement.Similarly,in

other studies in which education was the main interven-

tion,“teamwork across the units” did notimprove sig-

nificantly [21,22].

The dimensions of“non-punitive response to errors”

and “the frequency ofevents reported” were among the

weakestdimensions ofpatientsafety culture before the

intervention.The mean scores of “non-punitive response

to errors”after the intervention had significantlyin-

creasedin the experimentalgroup. However,these

scores were not significantly different to that of the con-

trol group.Therefore,we could notconclude thatthis

dimensionimproved due to the intervention.In

addition,the frequency of events reported did not show

any improvement.In a previous study,“non-punitive re-

sponse to errors” had improved while “the frequency of

events reported” did not improve [30].In another study,

using a single group pre-testpost-testdesign,the only

two dimensions thathad improved after safety training

were“non-punitiveresponseto errors”and “thefre-

quency of events reported” [21].Consequently,based on

the currentresults,we could notconclude thateduca-

tion can improvenon-punitiveresponseto errors.

Therefore,there is a need for collaboration among all

Table 2 The mean,standard deviation,and percentage of

positive responses to the 12 dimensions of patient safety

culture by allparticipants before the intervention

Dimensions Mean (±SD) Percent (%)

Teamwork within units 2.71 (±0.8) 45.65

Manager expectations and

actions promoting patient safety

3.39 (±0.75) 59.9

Organizationallearning and

continuous improvement

3.65 (±0.73) 72.46

Management support for patient safety3.08 (±1.04) 55.53

Feedback and communication on errors3.39 (±0.81) 60.86

Communication openness 2.77 (±0.72) 23.27

Frequency of events reported 2.77 (±0.62) 26.46

Teamwork across hospitalunits 3.08 (±0.84) 53.2

Staffing 1.76 (±0.54) 9.95

Handoffs and transitions 2.56 (±0.86) 28.15

Non-punitive response to errors 2.36 (±1.03) 21.66

Overallperception of patient safety 3.08 (±0.66) 51.2

Totalscores of the patient safety culture2.88 (±0.38) 42.35

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 5 of 8

mean scores (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study,the effect ofan innovative educa-

tionalempowermentprogram on patientsafety culture

is investigated.The finding suggests that the empower-

ment program improved the totalscore of patient safety

culture.The effectsize of this score waslarge (1.94)

[29].This shows thatthe effectof the intervention is

strong and clinically important.

The results of the present study showed that commu-

nication openness improved after the intervention.This

domain indicates member’s ability to question decisions

and actions ofindividuals with more authority and the

ability to speak up when there is a concern about patient

safety.This finding was in line with the findings ofa

study by Andreoliet al. in which SBAR wasused to

communicate and manage fall risk,[30] and also by Kha-

demian etal. in which the anesthesiaand operating

room nursing students’perceptionsof communication

dimension improved afterTeamSTEPPS training [31].

However,it was in contradiction with the results of two

other studiesin which patient safetyeducation and

teamwork training ofnurses and hospitalstaffdid not

improve their attitudes on communication openness [21,

22].In the current study,one aspect of the intervention

was training in speaking up,which may explain the dif-

ferencesbetween the currentfindings and those from

previous studies.Evidence show thathospitalstaffare

not competent enough in speaking up.This is based on

the factthat,among the 447,584 hospitalstaffin the

United States,65% ofthe respondents stated thatthey

were afraid of asking questions when they felt something

was wrong [20].Iranian nurses noted a sense of power-

lessness,due to dominance by the medical staff,prevents

them from talking in favor of their patients [32].There-

fore,empowering nurses to speak up might help them to

overcome these barriers.

In the pre-test,dimensions ofteamwork within units

and handoffs and transition were the weak aspects of pa-

tient safetyculture.However,after the intervention,

some improvements were observed in the experimental

group and these were elevated to the strong dimensions.

Similar results in previous studies have shown that train-

ing teamwork skills,using SBAR tool,and interventions

based on HSOPSC domains enhanced teamwork within

units [30,33,34].However,in some other studies,no

improvement was achieved after training [21,22].Simi-

lar to our findings,other studies showed improvement

on handoffs and transitions [22,30].Therefore,we could

suggesta similarempowermentprogram to improve

teamwork within units and handoff and transitions.

In the present study,“teamwork across the units” did

not improve significantly after the intervention.We in-

volved supervisors in addition to nurses in the empower-

mentprogram to reinforce theirrole in patientsafety

culture improvement.We expected that empowering su-

pervisorswould improvecoordination and teamwork

across units.These findings may be related to the small

sample size of supervisors.We should bear in the mind

thatthis dimension was strong before the intervention;

however,we expected more improvement.Similarly,in

other studies in which education was the main interven-

tion,“teamwork across the units” did notimprove sig-

nificantly [21,22].

The dimensions of“non-punitive response to errors”

and “the frequency ofevents reported” were among the

weakestdimensions ofpatientsafety culture before the

intervention.The mean scores of “non-punitive response

to errors”after the intervention had significantlyin-

creasedin the experimentalgroup. However,these

scores were not significantly different to that of the con-

trol group.Therefore,we could notconclude thatthis

dimensionimproved due to the intervention.In

addition,the frequency of events reported did not show

any improvement.In a previous study,“non-punitive re-

sponse to errors” had improved while “the frequency of

events reported” did not improve [30].In another study,

using a single group pre-testpost-testdesign,the only

two dimensions thathad improved after safety training

were“non-punitiveresponseto errors”and “thefre-

quency of events reported” [21].Consequently,based on

the currentresults,we could notconclude thateduca-

tion can improvenon-punitiveresponseto errors.

Therefore,there is a need for collaboration among all

Table 2 The mean,standard deviation,and percentage of

positive responses to the 12 dimensions of patient safety

culture by allparticipants before the intervention

Dimensions Mean (±SD) Percent (%)

Teamwork within units 2.71 (±0.8) 45.65

Manager expectations and

actions promoting patient safety

3.39 (±0.75) 59.9

Organizationallearning and

continuous improvement

3.65 (±0.73) 72.46

Management support for patient safety3.08 (±1.04) 55.53

Feedback and communication on errors3.39 (±0.81) 60.86

Communication openness 2.77 (±0.72) 23.27

Frequency of events reported 2.77 (±0.62) 26.46

Teamwork across hospitalunits 3.08 (±0.84) 53.2

Staffing 1.76 (±0.54) 9.95

Handoffs and transitions 2.56 (±0.86) 28.15

Non-punitive response to errors 2.36 (±1.03) 21.66

Overallperception of patient safety 3.08 (±0.66) 51.2

Totalscores of the patient safety culture2.88 (±0.38) 42.35

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 5 of 8

Table 3 Comparison of patient safety culture before and after the intervention within and between groups

Dimensions Groupa Pre-test Mean (±SD)Post-test Mean (±SD)P-value (within group)

Teamwork within units Experimental2.91(±0.74) 3.95(±0.43) < 0.001

Control 2.51 (± 0.82) 2.69(±0.80) 0.4

P-value 0.06 < 0.001

Manager expectations and actions promoting patient safetyExperimental3.48 (±0.83) 4.22 (±0.31) < 0.001

Control 3.22 (±0.68) 3.23 (±0.76) 0.5

P-value 0.3 < 0.001

Organizationallearning and continuous improvement Experimental3.83 (±0.65) 4.45 (±0.45) < 0.001

Control 3.49 (±0.82) 3.13 (±0.86) 0.1

P-value 0.06 < 0.001

Management support for patient safety Experimental3.15 (±1.05) 3.26 (±0.94) 0.5

Control 2.97 (±1.04) 3.31 (±0.99) 0.1

P-value 0.6 0.8

Overallperception of patient safety Experimental2.92 (±0.62) 3.08 (±0.53) 0.1

Control 3.29 (±0.63) 3.23 (±0.73) 0.6

P-value 0.06 0.3

Feedback and communication on errors Experimental3.25 (±0.85) 3.56 (±0.72) 0.1

Control 3.53 (±0.78) 3.52 (±0.77) 0.9

P-value 0.2 0.8

Communication openness Experimental2.72 (±0.67) 4.22 (±0.44) < 0.001

Control 2.80 (±0.79) 2.51 (±0.74) 0.1

P-value 0.5 < 0.001

Frequency of events reported Experimental2.91 (±0.56) 2.76 (±1.04) 0.4

Control 2.66 (±0.66) 2.51 (±0.68) 0.2

P-value 0.09 0.2

Teamwork across hospitalunits Experimental2.94 (±0.93) 3.06 (±0.84) 0.5

Control 3.17 (±0.76) 3.15 (±0.81) 0.8

P-value 0.1 0.6

Staffing Experimental1.84 (±0.62) 1.97 (±0.52) 0.3

Control 1.69 (±0.46) 1.68 (±0.57) 0.9

P-value 0.2 0.04

Handoffs and transitions Experimental2.75 (±0.91) 4.23 (±0.69) < 0.001

Control 2.42 (±0.80) 2.69 (±0.66) 0.2

P-value 0.1 < 0.001

Non-punitive response to errors Experimental2.25 (±0.93) 2.78 (±0.94) 0.02

Control 2.45 (±1.15) 2.46 (±1.17) 0.9

P-value 0.4 0.2

Totalscores of the patient safety culture Experimental2.91 (±0.4) 3.46 (±0.26) < 0.001b

Control 2.86 (±0.37) 2.84 (±0.37) 0.8

P-value 0.5 < 0.001

Safety score Experimental2.63 (±0.7) 3.37 (±0.5) < 0.001

Control 2.88 (±0.4) 2.90 (±0.5) 1.0

P-value 0.07 0.002

aThe between groups P-value is provided

bThe effect size of totalscores of the patient safety culture is 1.94

The bold numbers are significant p-values

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 6 of 8

Dimensions Groupa Pre-test Mean (±SD)Post-test Mean (±SD)P-value (within group)

Teamwork within units Experimental2.91(±0.74) 3.95(±0.43) < 0.001

Control 2.51 (± 0.82) 2.69(±0.80) 0.4

P-value 0.06 < 0.001

Manager expectations and actions promoting patient safetyExperimental3.48 (±0.83) 4.22 (±0.31) < 0.001

Control 3.22 (±0.68) 3.23 (±0.76) 0.5

P-value 0.3 < 0.001

Organizationallearning and continuous improvement Experimental3.83 (±0.65) 4.45 (±0.45) < 0.001

Control 3.49 (±0.82) 3.13 (±0.86) 0.1

P-value 0.06 < 0.001

Management support for patient safety Experimental3.15 (±1.05) 3.26 (±0.94) 0.5

Control 2.97 (±1.04) 3.31 (±0.99) 0.1

P-value 0.6 0.8

Overallperception of patient safety Experimental2.92 (±0.62) 3.08 (±0.53) 0.1

Control 3.29 (±0.63) 3.23 (±0.73) 0.6

P-value 0.06 0.3

Feedback and communication on errors Experimental3.25 (±0.85) 3.56 (±0.72) 0.1

Control 3.53 (±0.78) 3.52 (±0.77) 0.9

P-value 0.2 0.8

Communication openness Experimental2.72 (±0.67) 4.22 (±0.44) < 0.001

Control 2.80 (±0.79) 2.51 (±0.74) 0.1

P-value 0.5 < 0.001

Frequency of events reported Experimental2.91 (±0.56) 2.76 (±1.04) 0.4

Control 2.66 (±0.66) 2.51 (±0.68) 0.2

P-value 0.09 0.2

Teamwork across hospitalunits Experimental2.94 (±0.93) 3.06 (±0.84) 0.5

Control 3.17 (±0.76) 3.15 (±0.81) 0.8

P-value 0.1 0.6

Staffing Experimental1.84 (±0.62) 1.97 (±0.52) 0.3

Control 1.69 (±0.46) 1.68 (±0.57) 0.9

P-value 0.2 0.04

Handoffs and transitions Experimental2.75 (±0.91) 4.23 (±0.69) < 0.001

Control 2.42 (±0.80) 2.69 (±0.66) 0.2

P-value 0.1 < 0.001

Non-punitive response to errors Experimental2.25 (±0.93) 2.78 (±0.94) 0.02

Control 2.45 (±1.15) 2.46 (±1.17) 0.9

P-value 0.4 0.2

Totalscores of the patient safety culture Experimental2.91 (±0.4) 3.46 (±0.26) < 0.001b

Control 2.86 (±0.37) 2.84 (±0.37) 0.8

P-value 0.5 < 0.001

Safety score Experimental2.63 (±0.7) 3.37 (±0.5) < 0.001

Control 2.88 (±0.4) 2.90 (±0.5) 1.0

P-value 0.07 0.002

aThe between groups P-value is provided

bThe effect size of totalscores of the patient safety culture is 1.94

The bold numbers are significant p-values

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 6 of 8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

team members and leaders towards problem-solving and

to increase the number of events being reported.

It seems that the involvement of nurses and supervisors

in the empowermentprogram was notsufficientto im-

prove three important dimensions:staffing,error report-

ing,and non-punitive response to errors.Therefore,we

recommend that in the future higher-level hospital execu-

tives should also be involved in empowerment programs.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation ofthe present study was related to

the use of a self-reported instrument in order to explore

the effects ofempowermenton the patientsafety cul-

ture.It is recommended thatfurther studies should be

conducted using observationaldata collection methods.

Additionally,studies that assess the viewpoints ofother

parties such as patients are recommended.

Conclusion

This innovative empowermentprogram which involved

nursesand supervisorsresulted in improved patient

safety culture scores and developmentin some dimen-

sions.Communication openness,handoffsand transi-

tions,teamwork within units,learning and continuous

improvement,manager’s expectations and actions pro-

moting patientsafetyimproved significantlyafterthe

intervention.Therefore,this program can be utilized to

promote these importantdimensionsof patientsafety

culture.However,dimensions such as staffing,“non-pu-

nitive response to errors”,and “frequency of events that

were reported” continued to be the weak domains of the

patient safety culture throughout the study.Thus,to im-

prove these dimensions,conducting long-term studies

and additionalactions are also required.Given the im-

portance of reporting errors and adequate staffing in im-

proving patientsafety,it is recommended thatthese

items should be considered as a top priority for health-

care managers and hospital policymakers.

Abbreviations

AHRQ:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;HSOPSC:HospitalSurvey

on Patient Safety Culture;ICU:Intensive care units;SPSS:StatisticalPackage

for SocialScience;TeamSTEPPS:Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance

Performance and Patient Safety

Acknowledgments

This article was extracted from the MSc thesis by Maryam Amiri,and

approved by Vice Chancellor of Research of Shiraz University of Medical

Sciences,Shiraz,Iran.Hereby,the officials in NamaziHospital,Ms.Somayeh

Zahraei and Fatemeh Azadi,ICU nurses and supervisors are highly appreciated.

Appreciation goes to the Center for Development of Clinical Research at

Namazi Hospital and Dr.Nasrin Shokrpour,Mrs.Sareh Keshavarzi,Dr.Najaf Zare,

and Dr.Jamali for their collaboration in editorial assistance,design,statistics,and

data analysis.The authors would also like to thank the Research Consultation

Center at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and Mr.Argasi and Dr.N.Pakshir

for their editorial assistance.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Vice Chancellor of Resea

Shiraz University of Medical Sciences,Shiraz,Iran (Grant No.5793).The funding

body did not play any roles in the design of the study and collection,analysis,

and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the present study is available upon request.

Authors’contributions

Allauthors made substantialcontributions to the conception and design of

the study.Data was collected by MA.Data analysis and interpretation were

done by ZKh and MA.RNN also participated in data interpretation.MA,RNN,

and ZKh conducted the intervention.ZKh and MA participated in drafting

the manuscript.Allauthors revised the manuscript critically for important

intellectualcontent and finalapprovalof the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz

University of MedicalSciences (Shiraz,Iran) and the authorities at Namazi

Hospital(No.93–7397).Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants and confidentiality of the information was assured.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in publis

maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1Department of Nursing,Schoolof Nursing and Midwifery,Shiraz University

of MedicalSciences,Shiraz,Iran.2Anesthesia and CriticalCare Emergency

Medicine Department,NamaziHospital,Shiraz University of MedicalSciences,

Shiraz,Iran.

Received:18 July 2017 Accepted:12 June 2018

References

1. James JT.A new evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with

hospitalcare.J Patient Saf.2013;9(3):122–8.

2. Lyle-Edrosolo G,Waxman K.Aligning healthcare safety and quality

competencies:quality and safety education for nurses (QSEN),The Joint

Commission,and American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) magnet®

standards crosswalk.Nurse Leader.2016;14(1):70–5.

3. Ravi P,Vijai M.Errors in ICU:how safe is the patient? A prospective

observational study in a tertiary care hospital.J Anesth Clin Res.2015;6(6):535.

4. Zargarzadeh AH.Medication safety in Iran.J Pharm Care.2013;1(4):125–6.

5. Vazin A,FereidooniM.Determining frequency of prescription,

administration and transcription errors in internalintensive care unit of

Shahid FaghihiHospitalin Shiraz with direct observation approach.Iran J

Pharm Sci.2012;8(3):189–94.

6. Haghbin S,Shahsavari S,Vazin A.Medication errors in pediatric intensive care

unit:incidence,types and outcome.Trends Pharm Sci.2016;2(2):109–16.

7. FarziS,Irajpour A,SaghaeiM,RavaghiH.Causes of medication errors in

intensive care units from the perspective of healthcare professionals.J Res

Pharm Pract.2017;6(3):158–63.

8. NezamodiniZ,KhodamoradiF,Malekzadeh M,VaziriH.Nursing errors in

intensive care unit by human error identification in systems tool:a case

study.Jundishapur J Health Sci.2016;8(3):e36055.

9. Khademian Z,SharifiF,TabeiZ,Bolandparvaz S,Abbaszadeh A,AbbasiHR.

Teamwork improvement in emergency trauma department.Iran J Nurse

Midwifery Res.2013;18(4):333–9.

10. Shafakhah M,Zarshenas L,Sharif F,SarvestaniR.Evaluation of nursing

students’communication abilities in clinicalcourses in hospitals.Glob J

Health Sci.2015;7(4):323–8.

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 7 of 8

to increase the number of events being reported.

It seems that the involvement of nurses and supervisors

in the empowermentprogram was notsufficientto im-

prove three important dimensions:staffing,error report-

ing,and non-punitive response to errors.Therefore,we

recommend that in the future higher-level hospital execu-

tives should also be involved in empowerment programs.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation ofthe present study was related to

the use of a self-reported instrument in order to explore

the effects ofempowermenton the patientsafety cul-

ture.It is recommended thatfurther studies should be

conducted using observationaldata collection methods.

Additionally,studies that assess the viewpoints ofother

parties such as patients are recommended.

Conclusion

This innovative empowermentprogram which involved

nursesand supervisorsresulted in improved patient

safety culture scores and developmentin some dimen-

sions.Communication openness,handoffsand transi-

tions,teamwork within units,learning and continuous

improvement,manager’s expectations and actions pro-

moting patientsafetyimproved significantlyafterthe

intervention.Therefore,this program can be utilized to

promote these importantdimensionsof patientsafety

culture.However,dimensions such as staffing,“non-pu-

nitive response to errors”,and “frequency of events that

were reported” continued to be the weak domains of the

patient safety culture throughout the study.Thus,to im-

prove these dimensions,conducting long-term studies

and additionalactions are also required.Given the im-

portance of reporting errors and adequate staffing in im-

proving patientsafety,it is recommended thatthese

items should be considered as a top priority for health-

care managers and hospital policymakers.

Abbreviations

AHRQ:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;HSOPSC:HospitalSurvey

on Patient Safety Culture;ICU:Intensive care units;SPSS:StatisticalPackage

for SocialScience;TeamSTEPPS:Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance

Performance and Patient Safety

Acknowledgments

This article was extracted from the MSc thesis by Maryam Amiri,and

approved by Vice Chancellor of Research of Shiraz University of Medical

Sciences,Shiraz,Iran.Hereby,the officials in NamaziHospital,Ms.Somayeh

Zahraei and Fatemeh Azadi,ICU nurses and supervisors are highly appreciated.

Appreciation goes to the Center for Development of Clinical Research at

Namazi Hospital and Dr.Nasrin Shokrpour,Mrs.Sareh Keshavarzi,Dr.Najaf Zare,

and Dr.Jamali for their collaboration in editorial assistance,design,statistics,and

data analysis.The authors would also like to thank the Research Consultation

Center at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and Mr.Argasi and Dr.N.Pakshir

for their editorial assistance.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Vice Chancellor of Resea

Shiraz University of Medical Sciences,Shiraz,Iran (Grant No.5793).The funding

body did not play any roles in the design of the study and collection,analysis,

and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the present study is available upon request.

Authors’contributions

Allauthors made substantialcontributions to the conception and design of

the study.Data was collected by MA.Data analysis and interpretation were

done by ZKh and MA.RNN also participated in data interpretation.MA,RNN,

and ZKh conducted the intervention.ZKh and MA participated in drafting

the manuscript.Allauthors revised the manuscript critically for important

intellectualcontent and finalapprovalof the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz

University of MedicalSciences (Shiraz,Iran) and the authorities at Namazi

Hospital(No.93–7397).Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants and confidentiality of the information was assured.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in publis

maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1Department of Nursing,Schoolof Nursing and Midwifery,Shiraz University

of MedicalSciences,Shiraz,Iran.2Anesthesia and CriticalCare Emergency

Medicine Department,NamaziHospital,Shiraz University of MedicalSciences,

Shiraz,Iran.

Received:18 July 2017 Accepted:12 June 2018

References

1. James JT.A new evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with

hospitalcare.J Patient Saf.2013;9(3):122–8.

2. Lyle-Edrosolo G,Waxman K.Aligning healthcare safety and quality

competencies:quality and safety education for nurses (QSEN),The Joint

Commission,and American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) magnet®

standards crosswalk.Nurse Leader.2016;14(1):70–5.

3. Ravi P,Vijai M.Errors in ICU:how safe is the patient? A prospective

observational study in a tertiary care hospital.J Anesth Clin Res.2015;6(6):535.

4. Zargarzadeh AH.Medication safety in Iran.J Pharm Care.2013;1(4):125–6.

5. Vazin A,FereidooniM.Determining frequency of prescription,

administration and transcription errors in internalintensive care unit of

Shahid FaghihiHospitalin Shiraz with direct observation approach.Iran J

Pharm Sci.2012;8(3):189–94.

6. Haghbin S,Shahsavari S,Vazin A.Medication errors in pediatric intensive care

unit:incidence,types and outcome.Trends Pharm Sci.2016;2(2):109–16.

7. FarziS,Irajpour A,SaghaeiM,RavaghiH.Causes of medication errors in

intensive care units from the perspective of healthcare professionals.J Res

Pharm Pract.2017;6(3):158–63.

8. NezamodiniZ,KhodamoradiF,Malekzadeh M,VaziriH.Nursing errors in

intensive care unit by human error identification in systems tool:a case

study.Jundishapur J Health Sci.2016;8(3):e36055.

9. Khademian Z,SharifiF,TabeiZ,Bolandparvaz S,Abbaszadeh A,AbbasiHR.

Teamwork improvement in emergency trauma department.Iran J Nurse

Midwifery Res.2013;18(4):333–9.

10. Shafakhah M,Zarshenas L,Sharif F,SarvestaniR.Evaluation of nursing

students’communication abilities in clinicalcourses in hospitals.Glob J

Health Sci.2015;7(4):323–8.

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 7 of 8

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11. Patient Safety Network.Nursing and Patient Safety.2017.https://psnet.ahrq.

gov/primers/primer/22/nursing-and-patient-safety.Accessed 25 Nov 2017.

12. Rogers AE,Dean GE,Hwang WT,Scott.Role ofregistered nurses in

errorprevention,discovery and correction.QualSafHealth Care.2008;

17(2):117–21.

13. Henneman EA,GawlinskiA,Blank FS,Henneman PL,Jordan D,McKenzie JB.

Strategies used by criticalcare nurses to identify,interrupt,and correct

medicalerrors.Am J Crit Care.2010;19(6):500–9.

14. Mardon RE,Khanna K,Sorra J,Dyer N,Famolaro T.Exploring relationships

between hospitalpatient safety culture and adverse events.J Patient Saf.

2010;6(4):226–32.

15. Wang X,Liu K,You L,Xiang J,Hu H,Zhang L.The relationship between

patient safety culture and adverse events:a questionnaire survey.Int J Nurs

Stud.2014;51(8):1114–22.

16. Sammer CE,Lykens K,Singh KP,Mains DA,Lackan NA.What is patient safety

culture? A review of the literature.J Nurs Scholarsh.2010;42(2):156–65.

17. Azami-Aghdash S,Ebadifard Azar F,Rezapour A,AzamiA,RasiV,Klvany K.

Patient safety culture in hospitals of Iran:a systematic review and meta-

analysis.Med J Islam Repub Iran.2015;23(29):251.

18. Weaver SJ,LubomksiLH,Wilson RF,Pfoh ER,Martinez KA,Dy SM.

Promoting a culture of safety.In:Making health care safer II:An updated

criticalanalysis of the evidence for patient safety practices.Rockville:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2013.https://www.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/books/NBK133394/ .Accessed 23 Jun 2017.

19. Morello RT,Lowthian JA,Barker AL,McGinnes R,Dunt D,Brand C.Strategies

for improving patient safety culture in hospitals:a systematic review.BMJ

QualSaf.2013;22(1):8–11.

20. Famolaro T,Yount ND,Burns W,Flashner E,Liu H,Sorra J.Hospitalsurvey

on patient safety culture:2016 user comparative database report.2016.

(Prepared by Westat,Rockville,MD,under Contract No.HHSA

290201300003C).Rockville:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AHRQ Publication No.16–0021-EF

21. AbuAlRub RF,Abualhaja AA.The impact of educationalinterventions on

enhancing perceptions of patient safety culture among Jordanian senior

nurses.Nurs Forum.2014;49(2):139–50.

22. Jones F,Podila F,Power C.Creating a culture of safety in the emergency

department:The Value of Team Training.J Nurse Adm.2013;93(4):194–200.

23. Sayre MM.Improving collaboration and patient safety by encouraging

nurses to speak-up:Overcoming personaland organizationalobstacles

through self-reflection and collaboration .Available from ProQuest

Dissertations and Theses Global.(753487229).http://search.proquest.com/

docview/753487229?accountid=41313 .2010.Accessed 10 Jun 2016.

24. Institute of Medicine.Committee on the Health Professions Education

Summit.Health professions education:a bridge to quality.2003.https://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221528/ [Internet].NationalAcademies

Press (US).Accessed 15 Jun 2017.

25. Cronenwett L,Sherwood G,Barnsteiner J,Disch J,Johnson J,MitchellP.

Quality and safety education for nurses.Nurs Outlook.2007;55(3):112–31.

26. AHRQ.About TeamSTEPPS®.2016.https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/about-

teamstepps/index.html.Accessed 10 Mar 2017.

27. IzadiAR,Drikvand J,Ebrazeh A.The patientsafety culture in Fatemeh

Zahra Hospitalof Najafabad,Iran.Health Information Management.

2013;9(6):895–907.

28. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,Rockville.Surveys on Patient

Safety Culture™.https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/

quality-patient-safety/patientsafetyculture/hospitalscanform.pdf .Accessed

10 Mar 2018.

29. Nakagawa S,CuthillIC:Effectsize,confidence intervaland statistical

significance:a practicalguide forbiologists.Biologicalreviews 2007,

82(4):591–605.

30. AndreoliA,Fancott C,VeljiK,Baker GR,Solway S,Aimone E.Using SBAR to

communicate falls risk and management in interprofessionalrehabilitation

teams.Healthc Q.2010;13:94–101.

31. Khademian Z,PishgarZ, Torabizadeh C.Effectof training on the

attitude and knowledge ofteamwork among anesthesia and operating

room nursing students:a quasi-experimentalstudy.Shiraz E Med J.

2018;19(4):e61079.

32. Negarandeh R,Oskouie F,AhmadiF,Nikravesh M,Hallberg IR.Patient

advocacy:barriers and facilitators.BMC Nurs.2006;5(1):3.

33. Adams-Pizarro I,Walker Z,Robinson J,Kelly S,Toth M:Using the AHRQ

HospitalSurvey on patient safety culture as an intervention toolfor regional

clinicalimprovement collaboratives.In:Henriksen K,Battles JB,Keyes MA,

et al.,editors.Advances in patient safety:new directions and alternative

approaches (vol.2:culture and redesign).Rockville:Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality (US);2008.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/books/NBK43728/ .Accessed 10 Mar 2017.

34. Mayer CM,Cluff L,Lin WT,Willis TS,Stafford RE,Williams C:Evaluating

efforts to optimize TeamSTEPPS implementation in surgicaland pediatric

intensive care units.Jt Comm J QualPatient Saf 2011,37(8):365–374.

Amiri et al.BMC MedicalEducation (2018) 18:158 Page 8 of 8

gov/primers/primer/22/nursing-and-patient-safety.Accessed 25 Nov 2017.

12. Rogers AE,Dean GE,Hwang WT,Scott.Role ofregistered nurses in

errorprevention,discovery and correction.QualSafHealth Care.2008;

17(2):117–21.

13. Henneman EA,GawlinskiA,Blank FS,Henneman PL,Jordan D,McKenzie JB.

Strategies used by criticalcare nurses to identify,interrupt,and correct

medicalerrors.Am J Crit Care.2010;19(6):500–9.

14. Mardon RE,Khanna K,Sorra J,Dyer N,Famolaro T.Exploring relationships

between hospitalpatient safety culture and adverse events.J Patient Saf.

2010;6(4):226–32.

15. Wang X,Liu K,You L,Xiang J,Hu H,Zhang L.The relationship between

patient safety culture and adverse events:a questionnaire survey.Int J Nurs

Stud.2014;51(8):1114–22.

16. Sammer CE,Lykens K,Singh KP,Mains DA,Lackan NA.What is patient safety

culture? A review of the literature.J Nurs Scholarsh.2010;42(2):156–65.

17. Azami-Aghdash S,Ebadifard Azar F,Rezapour A,AzamiA,RasiV,Klvany K.

Patient safety culture in hospitals of Iran:a systematic review and meta-

analysis.Med J Islam Repub Iran.2015;23(29):251.

18. Weaver SJ,LubomksiLH,Wilson RF,Pfoh ER,Martinez KA,Dy SM.

Promoting a culture of safety.In:Making health care safer II:An updated

criticalanalysis of the evidence for patient safety practices.Rockville:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2013.https://www.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/books/NBK133394/ .Accessed 23 Jun 2017.

19. Morello RT,Lowthian JA,Barker AL,McGinnes R,Dunt D,Brand C.Strategies

for improving patient safety culture in hospitals:a systematic review.BMJ

QualSaf.2013;22(1):8–11.

20. Famolaro T,Yount ND,Burns W,Flashner E,Liu H,Sorra J.Hospitalsurvey

on patient safety culture:2016 user comparative database report.2016.

(Prepared by Westat,Rockville,MD,under Contract No.HHSA

290201300003C).Rockville:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AHRQ Publication No.16–0021-EF

21. AbuAlRub RF,Abualhaja AA.The impact of educationalinterventions on

enhancing perceptions of patient safety culture among Jordanian senior

nurses.Nurs Forum.2014;49(2):139–50.

22. Jones F,Podila F,Power C.Creating a culture of safety in the emergency

department:The Value of Team Training.J Nurse Adm.2013;93(4):194–200.

23. Sayre MM.Improving collaboration and patient safety by encouraging

nurses to speak-up:Overcoming personaland organizationalobstacles

through self-reflection and collaboration .Available from ProQuest

Dissertations and Theses Global.(753487229).http://search.proquest.com/

docview/753487229?accountid=41313 .2010.Accessed 10 Jun 2016.

24. Institute of Medicine.Committee on the Health Professions Education

Summit.Health professions education:a bridge to quality.2003.https://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221528/ [Internet].NationalAcademies

Press (US).Accessed 15 Jun 2017.

25. Cronenwett L,Sherwood G,Barnsteiner J,Disch J,Johnson J,MitchellP.

Quality and safety education for nurses.Nurs Outlook.2007;55(3):112–31.

26. AHRQ.About TeamSTEPPS®.2016.https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/about-

teamstepps/index.html.Accessed 10 Mar 2017.

27. IzadiAR,Drikvand J,Ebrazeh A.The patientsafety culture in Fatemeh

Zahra Hospitalof Najafabad,Iran.Health Information Management.

2013;9(6):895–907.

28. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,Rockville.Surveys on Patient

Safety Culture™.https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/

quality-patient-safety/patientsafetyculture/hospitalscanform.pdf .Accessed

10 Mar 2018.

29. Nakagawa S,CuthillIC:Effectsize,confidence intervaland statistical

significance:a practicalguide forbiologists.Biologicalreviews 2007,

82(4):591–605.

30. AndreoliA,Fancott C,VeljiK,Baker GR,Solway S,Aimone E.Using SBAR to

communicate falls risk and management in interprofessionalrehabilitation

teams.Healthc Q.2010;13:94–101.

31. Khademian Z,PishgarZ, Torabizadeh C.Effectof training on the

attitude and knowledge ofteamwork among anesthesia and operating

room nursing students:a quasi-experimentalstudy.Shiraz E Med J.

2018;19(4):e61079.

32. Negarandeh R,Oskouie F,AhmadiF,Nikravesh M,Hallberg IR.Patient

advocacy:barriers and facilitators.BMC Nurs.2006;5(1):3.

33. Adams-Pizarro I,Walker Z,Robinson J,Kelly S,Toth M:Using the AHRQ

HospitalSurvey on patient safety culture as an intervention toolfor regional

clinicalimprovement collaboratives.In:Henriksen K,Battles JB,Keyes MA,

et al.,editors.Advances in patient safety:new directions and alternative