Stakeholder Influence on CSR, Reputation, and Performance Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/08

|29

|17055

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes a study that investigates the influence of stakeholders on corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives and their subsequent impact on corporate reputation and business performance. The research, conducted through a mail survey of senior managers in Australian businesses, identifies employees and the public as key influential stakeholders in CSR decision-making. It reveals a positive relationship between CSR and reputation, which in turn affects market share, although not profitability. The study emphasizes the importance of managers understanding stakeholders' interests and incorporating them into CSR strategies to enhance reputation and business performance. The research also highlights concerns regarding the perceived lack of importance of regulatory stakeholders in CSR activities and suggests a need for revisiting government involvement in this area. The analysis provides insights into the link between CSR, reputation, and organizational performance, offering practical implications for managers aiming to improve business outcomes through stakeholder-influenced CSR strategies.

This is the authors’ final peer reviewed (post print) version of the item

published as:

Taghian,M, D'Souza,C and Polonsky,MJ 2015, A stakeholder approach to

corporate social responsibility, reputation and business performance, Social

Responsibility Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 340-363.

Available from Deakin Research Online:

http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30073833

Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright owner

Copyright: 2015, Emerald Group Publishing

published as:

Taghian,M, D'Souza,C and Polonsky,MJ 2015, A stakeholder approach to

corporate social responsibility, reputation and business performance, Social

Responsibility Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 340-363.

Available from Deakin Research Online:

http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30073833

Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright owner

Copyright: 2015, Emerald Group Publishing

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A stakeholder approach to corporate

social responsibility, reputation and

business performance

Mehdi Taghian, Clare D’Souza and Michael J. Polonsky

Abstract

Purpose – This paper aims to investigate business managers’ assessment of stakeholders’ influence

on corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. The key stakeholders included “employees” and

“unions” as internal and “public”, the “media” and the “government” as external stakeholders. The

purpose was to estimate the influence of stakeholders that managers perceive as important.

Moreover, the study sought to identify association between the CSR construct and corporate

reputation and in turn whether this influences business performance.

Design/methodology/approach – This study uses a mail survey with a random sampling of senior

managers sourced from Dun & Bradstreet’s Australian business database, focusing on large

organizations (i.e. minimum $10 million p.a. reported sales and minimum 100 employees) as the

selection criteria. A conceptual model was developed and tested using structural equation modeling.

Findings – The results identified that “employees” and the “public” are perceived to be the

influential stakeholder groups in CSR decision making. There was evidence of a positive relationship‐

between the CSR construct and reputation, which in turn influenced market share, but not

profitability.

Research limitations/implications – This study examined a cross section of organizations using Dun‐

& Bradstreet’s database of Australian businesses and may not fully represent the Australian business

mix. The effective response rate of 7.2 per cent appears to be low, even though it is comparable with

other research in the CSR area. There may have been some self selection by the respondents,‐

although there were no statistically significant differences identified in the corporate characteristics

of those invited to participate and those responding with usable questionnaires.

Practical implications – Managers can adopt a stakeholder influenced CSR strategy to generate‐

strong corporate reputation to improve business performance. It is important to ensure that the

interests of “employees” and “public” stakeholders are addressed within organizational strategy.

Respondents were less concerned about government stakeholders and thus government

involvement in organizational CSR may need to be revisited.

Social implications – The major concern that emerges from these findings is the absence of the

perceived importance of regulatory stakeholders on firms’ CSR activities. Regulatory controls of CSR

messages could reduce or eliminate inaccurate and misleading information to the public.

Originality/value – The analysis explains the perceived relative influence of stakeholders on CSR

decisions. It also provides an understanding of the link between organizational CSR reputation and

organization’s performance.

social responsibility, reputation and

business performance

Mehdi Taghian, Clare D’Souza and Michael J. Polonsky

Abstract

Purpose – This paper aims to investigate business managers’ assessment of stakeholders’ influence

on corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. The key stakeholders included “employees” and

“unions” as internal and “public”, the “media” and the “government” as external stakeholders. The

purpose was to estimate the influence of stakeholders that managers perceive as important.

Moreover, the study sought to identify association between the CSR construct and corporate

reputation and in turn whether this influences business performance.

Design/methodology/approach – This study uses a mail survey with a random sampling of senior

managers sourced from Dun & Bradstreet’s Australian business database, focusing on large

organizations (i.e. minimum $10 million p.a. reported sales and minimum 100 employees) as the

selection criteria. A conceptual model was developed and tested using structural equation modeling.

Findings – The results identified that “employees” and the “public” are perceived to be the

influential stakeholder groups in CSR decision making. There was evidence of a positive relationship‐

between the CSR construct and reputation, which in turn influenced market share, but not

profitability.

Research limitations/implications – This study examined a cross section of organizations using Dun‐

& Bradstreet’s database of Australian businesses and may not fully represent the Australian business

mix. The effective response rate of 7.2 per cent appears to be low, even though it is comparable with

other research in the CSR area. There may have been some self selection by the respondents,‐

although there were no statistically significant differences identified in the corporate characteristics

of those invited to participate and those responding with usable questionnaires.

Practical implications – Managers can adopt a stakeholder influenced CSR strategy to generate‐

strong corporate reputation to improve business performance. It is important to ensure that the

interests of “employees” and “public” stakeholders are addressed within organizational strategy.

Respondents were less concerned about government stakeholders and thus government

involvement in organizational CSR may need to be revisited.

Social implications – The major concern that emerges from these findings is the absence of the

perceived importance of regulatory stakeholders on firms’ CSR activities. Regulatory controls of CSR

messages could reduce or eliminate inaccurate and misleading information to the public.

Originality/value – The analysis explains the perceived relative influence of stakeholders on CSR

decisions. It also provides an understanding of the link between organizational CSR reputation and

organization’s performance.

Keywords Corporate social responsibility, Stakeholders, Business performance, Profit, Market share

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the voluntary actions taken by firms to benefit social and

environmental causes and communicated to the organization’s key stakeholders. CSR activities have

been found to influence corporate reputation which, in turn, has been found to increase business

performance (Ackerman, 1975; Baron, 2001; Garriga and Mele, 2004; McGuire et al., 1988; Menon

and Menon, 1997; Siegel and Vitaliano, 2007; Turker, 2009; Weaver et al., 1999). Firms’ adopt CSR to

allow them to be perceived as being “socially responsible”, gaining customer and other stakeholder

support (Golob and Bartlett, 2007).

However, for any strategic activities to be effective, managers must assess stakeholders’ interests to

identify what factors are important to them (Berman et al., 1999). Stakeholder orientation requires

that firms actively monitor and engage with their stakeholder environment, which has been likened

to expanding on the traditional marketing orientation approach (Ferrell et al., 2010). Evaluating of

the role of environmental forces has long been identified as important to strategy development

(Hambrick, 1982). Firms that are more effective in understanding these forces are better able to

develop strategy and, thus, improve organizational performance (Beal, 2000).

Research has suggested that managers are also considering how stakeholders view their actions

when developing activities that have a societal influence (Miles et al., 2006; Zink, 2005), which may

be influenced by a range of individuals or institutional factors (González Benito and González Benito,‐ ‐

2010). However, there are many instances where organizations have incorrectly assessed

stakeholder’s interests. For example, Shell revised its decisions in regard to the sinking of the Brent

Spar oil rig and chose instead to dismantle it, directly in response to the criticism of the global

community, a key stakeholder for Shell (Wheeler et al., 2002; Zyglidopoulos, 2002).

The effectiveness of managerial actions is, therefore, dependent on how well managers understand

stakeholders’ interests and influence and how appropriately they respond to them (Miles et al.,

2006; Wing Hung Lo et al., 2010). As a result, prior to designing and implementing strategy,‐

managers should undertake a variety of marketing research and environmental scanning activities to

understand the views of their stakeholders whom they believe are important (Berman et al., 1999).

Understanding the approaches used to monitor stakeholders such as stakeholder orientation, or

environmental scanning is important for understanding the wider business environment in which

strategic CSR decisions are made. Within this paper, we do not assess the process of how managers

collect stakeholder information, but rather the degree to which managers’ perceptions of

stakeholders’ influence affect their CSR decision making and, in turn, its impact on corporate‐

reputation and through this, how it impacts on the firm’s performance. We then provide some

recommendations on the importance of managers understanding and assessing the key

stakeholders’ attitudes, sentiments and expectations and addressing the business case for CSR. The

paper also refers to how government activities and initiatives may be used to assist in encouraging

organizations to be socially responsible.

The objectives of this study are:

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the voluntary actions taken by firms to benefit social and

environmental causes and communicated to the organization’s key stakeholders. CSR activities have

been found to influence corporate reputation which, in turn, has been found to increase business

performance (Ackerman, 1975; Baron, 2001; Garriga and Mele, 2004; McGuire et al., 1988; Menon

and Menon, 1997; Siegel and Vitaliano, 2007; Turker, 2009; Weaver et al., 1999). Firms’ adopt CSR to

allow them to be perceived as being “socially responsible”, gaining customer and other stakeholder

support (Golob and Bartlett, 2007).

However, for any strategic activities to be effective, managers must assess stakeholders’ interests to

identify what factors are important to them (Berman et al., 1999). Stakeholder orientation requires

that firms actively monitor and engage with their stakeholder environment, which has been likened

to expanding on the traditional marketing orientation approach (Ferrell et al., 2010). Evaluating of

the role of environmental forces has long been identified as important to strategy development

(Hambrick, 1982). Firms that are more effective in understanding these forces are better able to

develop strategy and, thus, improve organizational performance (Beal, 2000).

Research has suggested that managers are also considering how stakeholders view their actions

when developing activities that have a societal influence (Miles et al., 2006; Zink, 2005), which may

be influenced by a range of individuals or institutional factors (González Benito and González Benito,‐ ‐

2010). However, there are many instances where organizations have incorrectly assessed

stakeholder’s interests. For example, Shell revised its decisions in regard to the sinking of the Brent

Spar oil rig and chose instead to dismantle it, directly in response to the criticism of the global

community, a key stakeholder for Shell (Wheeler et al., 2002; Zyglidopoulos, 2002).

The effectiveness of managerial actions is, therefore, dependent on how well managers understand

stakeholders’ interests and influence and how appropriately they respond to them (Miles et al.,

2006; Wing Hung Lo et al., 2010). As a result, prior to designing and implementing strategy,‐

managers should undertake a variety of marketing research and environmental scanning activities to

understand the views of their stakeholders whom they believe are important (Berman et al., 1999).

Understanding the approaches used to monitor stakeholders such as stakeholder orientation, or

environmental scanning is important for understanding the wider business environment in which

strategic CSR decisions are made. Within this paper, we do not assess the process of how managers

collect stakeholder information, but rather the degree to which managers’ perceptions of

stakeholders’ influence affect their CSR decision making and, in turn, its impact on corporate‐

reputation and through this, how it impacts on the firm’s performance. We then provide some

recommendations on the importance of managers understanding and assessing the key

stakeholders’ attitudes, sentiments and expectations and addressing the business case for CSR. The

paper also refers to how government activities and initiatives may be used to assist in encouraging

organizations to be socially responsible.

The objectives of this study are:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

to identify the extent to which key stakeholders’ influence managers CSR

decision making;‐

to seek evidence of an association between the CSR measure and corporate reputation; and

to identify if there is an association between corporate reputation and business

performance.

The study begins by discussing CSR, its influence on corporate reputation, and in turn its influence on

firm performance. In particular, it is argued that when CSR actions are communicated to

stakeholders, there is the likelihood that such activities influence corporate image and reputation.

Consequently, such activities need to be considered as an element of marketing communication and,

so, be free from potentially deceptive information. The suggestion is that existing marketing

communication control mechanisms need to be applied to the communication of CSR activities, even

though such activities are voluntary in nature. We then outline the key stakeholders and discuss the

components of the proposed model, which has been developed to examine the proposed

associations. The associations include identification of the stakeholders’ perceived influence on

management’s decisions, assessment of whether CSR activities influence organizational reputation

and, in turn, the impact of reputation on organizational performance. The business performance

measures are then explained. These are based on managers’ subjective assessments of changes in

performance by the respondents, rather than objective assessment of performance.

CSR and its impact on corporate reputation and firm’s performance

There is a growing interest in the theoretical development and practical aspects of CSR. Dahlsrud

(2008) has reviewed 37 definitions of CSR, most of which he suggests are generally similar in focus.

In this study, we define CSR activities as voluntary actions undertaken by organizations extending

beyond their legal obligations, providing benefits to the environment and to society (Andreasen,

1994; Turker, 2009; Werther and Chandler, 2006).

CSR has become a popular corporate practice, as well as being important for stakeholders when

assessing corporate activities (Perrini and Minoja, 2008). Motivation for the growing academic

interest is, at least partly, the result of recent global corporate problems arising from unethical

corporate behavior. The global consequence of unethical conduct has resulted in a general loss of

consumers’ trust and confidence in business practices (Minor and Morgan, 2011).

In many cases, therefore, the application of CSR initiatives may be characterized as a marketing

activity, especially if the activity is designed to influence stakeholders’ perception of the firm. In

looking at CSR as a marketing initiative, such activities would be subject to legal frameworks that

regulate the veracity of marketing activities, such as the Federal Trade Commission in the USA, and

the Consumer and Competition Commission in Australia (Golob and Bartlett, 2007). These

governmental frameworks already regulate the promotion of CSR related activities such as green‐

marketing claims (Kangun and Polonsky, 1995). There are also other international frameworks that

have an impact on CSR related activities, such as the International Organisation for Standardization‐

(ISO) social accountability standards (Miles and Munilla, 2004).

CSR can also be characterized as strategic choices that are incorporated into a firm’s business

strategy and linked to its brand personality. For CSR to be effective, it has to affect societal outcomes

as well as be expressed through corporate communications, with the intention of informing and

decision making;‐

to seek evidence of an association between the CSR measure and corporate reputation; and

to identify if there is an association between corporate reputation and business

performance.

The study begins by discussing CSR, its influence on corporate reputation, and in turn its influence on

firm performance. In particular, it is argued that when CSR actions are communicated to

stakeholders, there is the likelihood that such activities influence corporate image and reputation.

Consequently, such activities need to be considered as an element of marketing communication and,

so, be free from potentially deceptive information. The suggestion is that existing marketing

communication control mechanisms need to be applied to the communication of CSR activities, even

though such activities are voluntary in nature. We then outline the key stakeholders and discuss the

components of the proposed model, which has been developed to examine the proposed

associations. The associations include identification of the stakeholders’ perceived influence on

management’s decisions, assessment of whether CSR activities influence organizational reputation

and, in turn, the impact of reputation on organizational performance. The business performance

measures are then explained. These are based on managers’ subjective assessments of changes in

performance by the respondents, rather than objective assessment of performance.

CSR and its impact on corporate reputation and firm’s performance

There is a growing interest in the theoretical development and practical aspects of CSR. Dahlsrud

(2008) has reviewed 37 definitions of CSR, most of which he suggests are generally similar in focus.

In this study, we define CSR activities as voluntary actions undertaken by organizations extending

beyond their legal obligations, providing benefits to the environment and to society (Andreasen,

1994; Turker, 2009; Werther and Chandler, 2006).

CSR has become a popular corporate practice, as well as being important for stakeholders when

assessing corporate activities (Perrini and Minoja, 2008). Motivation for the growing academic

interest is, at least partly, the result of recent global corporate problems arising from unethical

corporate behavior. The global consequence of unethical conduct has resulted in a general loss of

consumers’ trust and confidence in business practices (Minor and Morgan, 2011).

In many cases, therefore, the application of CSR initiatives may be characterized as a marketing

activity, especially if the activity is designed to influence stakeholders’ perception of the firm. In

looking at CSR as a marketing initiative, such activities would be subject to legal frameworks that

regulate the veracity of marketing activities, such as the Federal Trade Commission in the USA, and

the Consumer and Competition Commission in Australia (Golob and Bartlett, 2007). These

governmental frameworks already regulate the promotion of CSR related activities such as green‐

marketing claims (Kangun and Polonsky, 1995). There are also other international frameworks that

have an impact on CSR related activities, such as the International Organisation for Standardization‐

(ISO) social accountability standards (Miles and Munilla, 2004).

CSR can also be characterized as strategic choices that are incorporated into a firm’s business

strategy and linked to its brand personality. For CSR to be effective, it has to affect societal outcomes

as well as be expressed through corporate communications, with the intention of informing and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

influencing the firm’s internal and external key stakeholders in such a way that it is seen as value

adding (Miles et al., 2006; Neville et al., 2005). Such organization wide action (Golob and Bartlett,‐

2007) is intended to promote CSR related claims that are often designed to influence corporate‐

positioning and reputation. The reputation of an organization reflects their stakeholders’ perception

of the organizational personality. This perception is formed over time based on consumers’

experiences with the company, influences from other stakeholders and corporate communications.

As such, both CSR related claims and corporate reputation are central to a firm’s strategic direction‐

(Du et al. (2010)).

Given that CSR is becoming a prerequisite for organizations to operate (Minor and Morgan, 2011),

this study builds on the theoretical perspective that a firm’s adoption of CSR is a strategic decision,

aimed at achieving specific business performance objectives rather than being pursued for purely

philanthropic purposes (Garriga and Mele, 2004). Thus, managers need to consider all their legal,

ethical and discretionary responsibilities (Burton and Goldsby, 2007), as well as how their actions will

affect all stakeholders.

Notably, the positioning of CSR as an ethical and moral responsibility of business decision makers‐

could potentially be misplaced if, as some argue, CSR activities generate additional costs without

contributing additional profits. The dilemma of additional costs contradicts the fundamental tenet of

agency, where managers should be the generators of wealth for the firm’s owners while operating

within the legal framework (Freeman and Hasnaoui, 2010; Galan, 2006; Tsoutsoura, 2004). This

raises the issue, in regard to CSR, of which issues a firm wishes to pursue (Polonsky and Jevons,

2009).

CSR activities need to be considered from a moral and ethical basis, assuming that firms self regulate‐

their CSR behavior and their communication of those activities. However, they rely on individual

managers whose personality characteristics (i.e. attitudes, upbringing, cultural background and

religious orientation) can influence the outcomes (Carroll and Shabana, 2010), resulting in variations

in practice, often within the same organization. The recent ethical breaches provide evidence of the

ineffectiveness of a self regulation approach to corporate behavior. The ineffectiveness of self‐ ‐

regulation has prompted a debate on stronger governmental regulation to protect the economy,

businesses and consumers, from inappropriate behavior (Kemper and Martin, 2010). In addition, the

growing importance to consumers of social issues such as the environment has resulted in

businesses actively adopting CSR activities that are designed to resonate with both the brand and

the firms’ consumers (Bigné et al., 2012), thereby improving consumers’ perceptions of the firm (Ben

Brik et al., 2011).

Targeting of consumers’ perceptions through improvements of firm’s corporate reputation might

suggest that CSR is a strategic philanthropy tool and is more about corporate profits than social

responsibility (Carroll and Shabana, 2010) whereby “doing good” is undertaken in a way that

achieves the most corporate benefit rather than focusing on societal benefit. As a result, such CSR

activities would be a reactive tactical tool rather than a proactive strategic and positioning approach

(Faulkner et al., 2005). Given that firms’ CSR strategies should be driven by both business and

societal objectives, it is critical that they involve managers who assess and react to the sentiments of

organizational stakeholders that most strongly influence their business activities (Albareda et al.,

2008; Minor and Morgan, 2011; Moon, 2004). Although, as has been mentioned earlier, these

strategies also assume that managers effectively assess stakeholders’ interests (Berman et al., 1999;

Wing Hung et al., 2010).‐

adding (Miles et al., 2006; Neville et al., 2005). Such organization wide action (Golob and Bartlett,‐

2007) is intended to promote CSR related claims that are often designed to influence corporate‐

positioning and reputation. The reputation of an organization reflects their stakeholders’ perception

of the organizational personality. This perception is formed over time based on consumers’

experiences with the company, influences from other stakeholders and corporate communications.

As such, both CSR related claims and corporate reputation are central to a firm’s strategic direction‐

(Du et al. (2010)).

Given that CSR is becoming a prerequisite for organizations to operate (Minor and Morgan, 2011),

this study builds on the theoretical perspective that a firm’s adoption of CSR is a strategic decision,

aimed at achieving specific business performance objectives rather than being pursued for purely

philanthropic purposes (Garriga and Mele, 2004). Thus, managers need to consider all their legal,

ethical and discretionary responsibilities (Burton and Goldsby, 2007), as well as how their actions will

affect all stakeholders.

Notably, the positioning of CSR as an ethical and moral responsibility of business decision makers‐

could potentially be misplaced if, as some argue, CSR activities generate additional costs without

contributing additional profits. The dilemma of additional costs contradicts the fundamental tenet of

agency, where managers should be the generators of wealth for the firm’s owners while operating

within the legal framework (Freeman and Hasnaoui, 2010; Galan, 2006; Tsoutsoura, 2004). This

raises the issue, in regard to CSR, of which issues a firm wishes to pursue (Polonsky and Jevons,

2009).

CSR activities need to be considered from a moral and ethical basis, assuming that firms self regulate‐

their CSR behavior and their communication of those activities. However, they rely on individual

managers whose personality characteristics (i.e. attitudes, upbringing, cultural background and

religious orientation) can influence the outcomes (Carroll and Shabana, 2010), resulting in variations

in practice, often within the same organization. The recent ethical breaches provide evidence of the

ineffectiveness of a self regulation approach to corporate behavior. The ineffectiveness of self‐ ‐

regulation has prompted a debate on stronger governmental regulation to protect the economy,

businesses and consumers, from inappropriate behavior (Kemper and Martin, 2010). In addition, the

growing importance to consumers of social issues such as the environment has resulted in

businesses actively adopting CSR activities that are designed to resonate with both the brand and

the firms’ consumers (Bigné et al., 2012), thereby improving consumers’ perceptions of the firm (Ben

Brik et al., 2011).

Targeting of consumers’ perceptions through improvements of firm’s corporate reputation might

suggest that CSR is a strategic philanthropy tool and is more about corporate profits than social

responsibility (Carroll and Shabana, 2010) whereby “doing good” is undertaken in a way that

achieves the most corporate benefit rather than focusing on societal benefit. As a result, such CSR

activities would be a reactive tactical tool rather than a proactive strategic and positioning approach

(Faulkner et al., 2005). Given that firms’ CSR strategies should be driven by both business and

societal objectives, it is critical that they involve managers who assess and react to the sentiments of

organizational stakeholders that most strongly influence their business activities (Albareda et al.,

2008; Minor and Morgan, 2011; Moon, 2004). Although, as has been mentioned earlier, these

strategies also assume that managers effectively assess stakeholders’ interests (Berman et al., 1999;

Wing Hung et al., 2010).‐

The organization’s identity in the minds of the corporate stakeholders can be considered its

reputation or corporate identity. As such, firms societal activities play a critical role in shaping how

stakeholder’s assess organization’s reputation (Lii and Lee, 2012) and this in turn impacts on

corporate performance (Lai et al., 2010). Corporate reputation has been referred to as a collective

judgment of a corporation over time (Barnett et al., 2006). Reputation influences how stakeholders

assess the corporation and it enables consumers to make comparisons with other organizations. The

firm’s corporate reputation also creates expectations in regard to actions aligning with its

reputation. Research has indicated that there is an association between corporate reputation and

business performance, in other words, the more positive the reputation, the higher the performance

(Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Lai et al., 2010; Neville et al., 2005). Given CSR activities affect

corporate reputation (Bertels and Peloza, 2008; Lai et al., 2010), it is important to investigate

whether or not improved corporate reputation through stakeholder engagement increases business

performance.

Key stakeholders

Stakeholder theory asserts that managers need to consider the values, sentiments and expectations

of their key stakeholders, where a stakeholder is any individual or group that has a “stake” in the

firm and “can affect or be affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives” (Freeman

and McVea, 2001, p. 4), either as a claimant or influencer (Fassin, 2008). Managers design strategy

and corporate actions, including CSR actions, to address or respond to what the managers believe

are their key stakeholders’ expectations (Clarkson, 1995; Dawkins and Lewis, 2003; Donaldson and

Preston, 1995; Maignan et al., 2005; Wing Hung Lo et al., 2010). Researchers have identified that‐

any firm can focus on meeting stakeholders’ expectations (i.e. being stakeholder oriented) and that‐

such strategy potentially enhances business performance (Bhattacharya and Korschun, 2008; Bosse

et al., 2008; Ferrell et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2010; Rivera Camino, 2007).‐

Research has classified stakeholders in a number of ways (Clarkson, 1995). In this study, de

Chernatony and Harris’s (2000) approach for classifying stakeholders as internal or external has been

used. Internal stakeholders include managers, shareholders, company employees and labor unions.

External stakeholders comprise the general public (i.e. the community and local residents), media

and the government. The following sub sections briefly describe key internal and external‐

stakeholders, and their influence on CSR activities.

Internal stakeholders

Internal stakeholders are those groups who directly participate in the operation of the business

(Aaltonen, 2011). They comprise managers, employees and labor unions.

Employees and managers

Internal (primary) stakeholders are perhaps the most influential groups in a business enterprise

(Masden and Ulhoi, 2001; Rupp et al., 2006). They directly participate in the formation, design,

structure and conduct of a business. The managers’ and employees’ levels of motivation, loyalty and

organizational support are crucial if stated goals are to be achieved. Employees’ attitudes toward the

organization may also influence the external stakeholders’ perceptions about the firm (de

reputation or corporate identity. As such, firms societal activities play a critical role in shaping how

stakeholder’s assess organization’s reputation (Lii and Lee, 2012) and this in turn impacts on

corporate performance (Lai et al., 2010). Corporate reputation has been referred to as a collective

judgment of a corporation over time (Barnett et al., 2006). Reputation influences how stakeholders

assess the corporation and it enables consumers to make comparisons with other organizations. The

firm’s corporate reputation also creates expectations in regard to actions aligning with its

reputation. Research has indicated that there is an association between corporate reputation and

business performance, in other words, the more positive the reputation, the higher the performance

(Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Lai et al., 2010; Neville et al., 2005). Given CSR activities affect

corporate reputation (Bertels and Peloza, 2008; Lai et al., 2010), it is important to investigate

whether or not improved corporate reputation through stakeholder engagement increases business

performance.

Key stakeholders

Stakeholder theory asserts that managers need to consider the values, sentiments and expectations

of their key stakeholders, where a stakeholder is any individual or group that has a “stake” in the

firm and “can affect or be affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives” (Freeman

and McVea, 2001, p. 4), either as a claimant or influencer (Fassin, 2008). Managers design strategy

and corporate actions, including CSR actions, to address or respond to what the managers believe

are their key stakeholders’ expectations (Clarkson, 1995; Dawkins and Lewis, 2003; Donaldson and

Preston, 1995; Maignan et al., 2005; Wing Hung Lo et al., 2010). Researchers have identified that‐

any firm can focus on meeting stakeholders’ expectations (i.e. being stakeholder oriented) and that‐

such strategy potentially enhances business performance (Bhattacharya and Korschun, 2008; Bosse

et al., 2008; Ferrell et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2010; Rivera Camino, 2007).‐

Research has classified stakeholders in a number of ways (Clarkson, 1995). In this study, de

Chernatony and Harris’s (2000) approach for classifying stakeholders as internal or external has been

used. Internal stakeholders include managers, shareholders, company employees and labor unions.

External stakeholders comprise the general public (i.e. the community and local residents), media

and the government. The following sub sections briefly describe key internal and external‐

stakeholders, and their influence on CSR activities.

Internal stakeholders

Internal stakeholders are those groups who directly participate in the operation of the business

(Aaltonen, 2011). They comprise managers, employees and labor unions.

Employees and managers

Internal (primary) stakeholders are perhaps the most influential groups in a business enterprise

(Masden and Ulhoi, 2001; Rupp et al., 2006). They directly participate in the formation, design,

structure and conduct of a business. The managers’ and employees’ levels of motivation, loyalty and

organizational support are crucial if stated goals are to be achieved. Employees’ attitudes toward the

organization may also influence the external stakeholders’ perceptions about the firm (de

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Chernatony and Harris, 2000). Employees and managers participate in the development and

implementation of corporate strategies, including those related to CSR activities, as well as

reflecting, representing and supporting activities related to societal norms (sentiments and

preferences). Employees generally like working for companies that are ethical, both in terms of the

way they treat their employees and the way they engage with the broader society (Coldwell et al.,

2008; Stevens, 2008; Valentine and Fleischman, 2008). As such, employees are important in a firm’s

success and influence corporate decision making (Spitzeck and Hansen, 2010). Therefore,‐

employees’ attitudes and support of corporate actions would be of critical interest to the

management. This requires that managers investigate their employees’ attitudes and sentiments

about the CSR activities of the company. This can be done through consultation and communication,

allowing the employees to express themselves and react to the current organizational activities

(Roeck and Delobbe, 2012).

Unions

Unions are an aggregation of employees who seek to protect employee interests and the working

conditions of employees (Darnall et al., 2009). Unions have varying importance to organizations

depending on their ability to influence organizational actions (Savage et al., 1991). In some

countries, unions have broader social agendas, which move beyond working conditions. Unions,

therefore, have the potential to assist organizations in their business objectives, as well as influence

businesses’ broader social interests, including organizations’ CSR activities (Gjølberg, 2011).

External stakeholders

External stakeholders are individuals or groups outside the company that can affect or be affected

by an organization’s activities (Fassin, 2008). These stakeholders can influence the firm’s decision‐

making by applying direct and indirect pressure. External stakeholders’ acceptance of firms’ socially

responsible positioning is important to gain their support (Minor and Morgan, 2011). An

organization can formulate and manage external stakeholders’ perceptions of a firm through direct

corporate actions and communication (Randel et al., 2009).

Public stakeholders

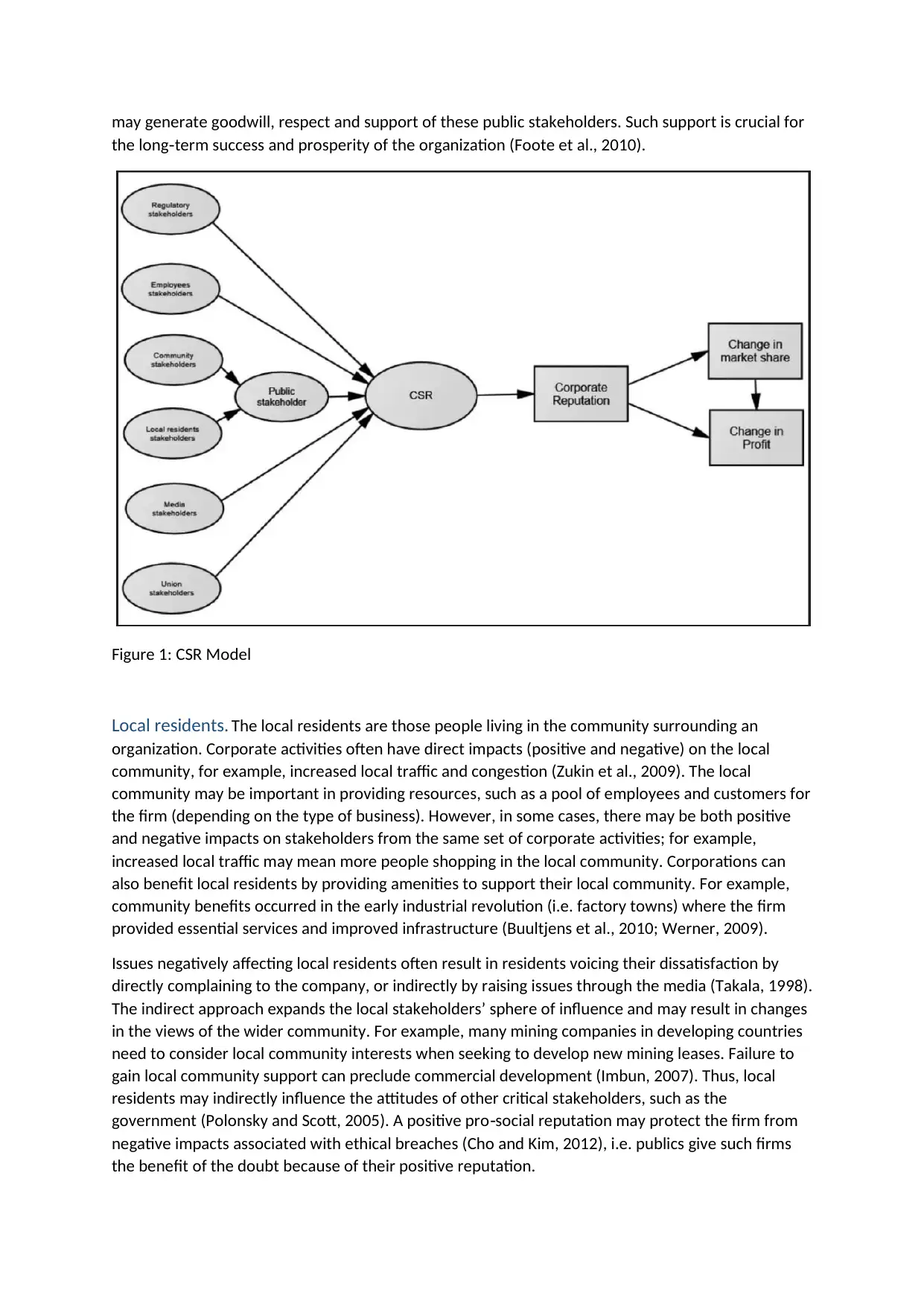

Public stakeholders include two groups: the local residents and the community in general. As will be

discussed in the components explanation of the model (Figure 1), these two groups have been

combined because of the high correlation between them. This stakeholder group incorporates

consumers and social support groups for the company, who are critical in the effective operation of

the organization. For example, in the case of Shell, they changed their strategic decision because the

wider community protested over their proposed actions in regards to the disposal of the Brent Spar

oil rig (Wheeler et al., 2002; Zyglidopoulos, 2002). In other instances, the community acting as

consumers has chosen to boycott firms because of their unethical behavior, which represents a lack

of CSR activities (Klein et al., 2004). Finally, local residents may support or oppose corporate

activities that are vital to organizational success. For example, activities such as hosting and

sponsoring community events, engaging in local community activities or donating money to

community organizations like local schools, libraries, hospitals, cultural organizations and charities

can initiate local resident support and cooperation (Cho, and Kim, 2012). A positive CSR reputation

implementation of corporate strategies, including those related to CSR activities, as well as

reflecting, representing and supporting activities related to societal norms (sentiments and

preferences). Employees generally like working for companies that are ethical, both in terms of the

way they treat their employees and the way they engage with the broader society (Coldwell et al.,

2008; Stevens, 2008; Valentine and Fleischman, 2008). As such, employees are important in a firm’s

success and influence corporate decision making (Spitzeck and Hansen, 2010). Therefore,‐

employees’ attitudes and support of corporate actions would be of critical interest to the

management. This requires that managers investigate their employees’ attitudes and sentiments

about the CSR activities of the company. This can be done through consultation and communication,

allowing the employees to express themselves and react to the current organizational activities

(Roeck and Delobbe, 2012).

Unions

Unions are an aggregation of employees who seek to protect employee interests and the working

conditions of employees (Darnall et al., 2009). Unions have varying importance to organizations

depending on their ability to influence organizational actions (Savage et al., 1991). In some

countries, unions have broader social agendas, which move beyond working conditions. Unions,

therefore, have the potential to assist organizations in their business objectives, as well as influence

businesses’ broader social interests, including organizations’ CSR activities (Gjølberg, 2011).

External stakeholders

External stakeholders are individuals or groups outside the company that can affect or be affected

by an organization’s activities (Fassin, 2008). These stakeholders can influence the firm’s decision‐

making by applying direct and indirect pressure. External stakeholders’ acceptance of firms’ socially

responsible positioning is important to gain their support (Minor and Morgan, 2011). An

organization can formulate and manage external stakeholders’ perceptions of a firm through direct

corporate actions and communication (Randel et al., 2009).

Public stakeholders

Public stakeholders include two groups: the local residents and the community in general. As will be

discussed in the components explanation of the model (Figure 1), these two groups have been

combined because of the high correlation between them. This stakeholder group incorporates

consumers and social support groups for the company, who are critical in the effective operation of

the organization. For example, in the case of Shell, they changed their strategic decision because the

wider community protested over their proposed actions in regards to the disposal of the Brent Spar

oil rig (Wheeler et al., 2002; Zyglidopoulos, 2002). In other instances, the community acting as

consumers has chosen to boycott firms because of their unethical behavior, which represents a lack

of CSR activities (Klein et al., 2004). Finally, local residents may support or oppose corporate

activities that are vital to organizational success. For example, activities such as hosting and

sponsoring community events, engaging in local community activities or donating money to

community organizations like local schools, libraries, hospitals, cultural organizations and charities

can initiate local resident support and cooperation (Cho, and Kim, 2012). A positive CSR reputation

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

may generate goodwill, respect and support of these public stakeholders. Such support is crucial for

the long term success and prosperity of the organization (Foote et al., 2010).‐

Figure 1: CSR Model

Local residents. The local residents are those people living in the community surrounding an

organization. Corporate activities often have direct impacts (positive and negative) on the local

community, for example, increased local traffic and congestion (Zukin et al., 2009). The local

community may be important in providing resources, such as a pool of employees and customers for

the firm (depending on the type of business). However, in some cases, there may be both positive

and negative impacts on stakeholders from the same set of corporate activities; for example,

increased local traffic may mean more people shopping in the local community. Corporations can

also benefit local residents by providing amenities to support their local community. For example,

community benefits occurred in the early industrial revolution (i.e. factory towns) where the firm

provided essential services and improved infrastructure (Buultjens et al., 2010; Werner, 2009).

Issues negatively affecting local residents often result in residents voicing their dissatisfaction by

directly complaining to the company, or indirectly by raising issues through the media (Takala, 1998).

The indirect approach expands the local stakeholders’ sphere of influence and may result in changes

in the views of the wider community. For example, many mining companies in developing countries

need to consider local community interests when seeking to develop new mining leases. Failure to

gain local community support can preclude commercial development (Imbun, 2007). Thus, local

residents may indirectly influence the attitudes of other critical stakeholders, such as the

government (Polonsky and Scott, 2005). A positive pro social reputation may protect the firm from‐

negative impacts associated with ethical breaches (Cho and Kim, 2012), i.e. publics give such firms

the benefit of the doubt because of their positive reputation.

the long term success and prosperity of the organization (Foote et al., 2010).‐

Figure 1: CSR Model

Local residents. The local residents are those people living in the community surrounding an

organization. Corporate activities often have direct impacts (positive and negative) on the local

community, for example, increased local traffic and congestion (Zukin et al., 2009). The local

community may be important in providing resources, such as a pool of employees and customers for

the firm (depending on the type of business). However, in some cases, there may be both positive

and negative impacts on stakeholders from the same set of corporate activities; for example,

increased local traffic may mean more people shopping in the local community. Corporations can

also benefit local residents by providing amenities to support their local community. For example,

community benefits occurred in the early industrial revolution (i.e. factory towns) where the firm

provided essential services and improved infrastructure (Buultjens et al., 2010; Werner, 2009).

Issues negatively affecting local residents often result in residents voicing their dissatisfaction by

directly complaining to the company, or indirectly by raising issues through the media (Takala, 1998).

The indirect approach expands the local stakeholders’ sphere of influence and may result in changes

in the views of the wider community. For example, many mining companies in developing countries

need to consider local community interests when seeking to develop new mining leases. Failure to

gain local community support can preclude commercial development (Imbun, 2007). Thus, local

residents may indirectly influence the attitudes of other critical stakeholders, such as the

government (Polonsky and Scott, 2005). A positive pro social reputation may protect the firm from‐

negative impacts associated with ethical breaches (Cho and Kim, 2012), i.e. publics give such firms

the benefit of the doubt because of their positive reputation.

Community in general. Community groups include the population at large, consumers and special

interest groups. Their perceptions of a company reflect the firm’s status and reputation (Neville et

al., 2005), as well as how the firm is positioned in respect to other organizations. Community groups’

perceptions are formed through long term corporate communications, their experience with the‐

firm and its products, as well as their perceptions of an organization’s societal impacts (Hoeffler et

al., 2010). The community plays many roles including as consumers, where consumers have a direct

impact on corporate action. For example, consumers can boycott firms because of their unethical

behavior, as this represents a lack of socially responsible activities (Klein et al., 2004). Perceived

inappropriate corporate actions can have long term consequences, affecting both corporate‐

reputation and firm performance. For example, Nestlé is still being punished by some consumers

over its activities in regards to the questionable promoting of infant formula in developing countries

two decades earlier (Boyd, 2012). Of course, community groups also have the ability to indirectly

influence others through the media as well. As was identified earlier, Shell changed their decision to

sink the Brent Spar oil rig because of global community protests (Wheeler et al., 2002;

Zyglidopoulos, 2002).

Media

The role of the media is to inform the wider community about issues of public interest. A neutral and

unbiased media can, however, also shape public opinion (Bodemer et al., 2012; Haddock Fraser,‐

2012). The media are indirect external stakeholders operating independently of the organization.

The media is an essential facilitator of communication between the firm and its stakeholders

(Deephouse and Heugend, 2009). The media’s support for a firm can be gained through maintaining

ongoing contacts and providing newsworthy information. However, firms cannot control the media,

thus support will be variable. The media, therefore, have the power to shape other stakeholders’

perceptions about an organization’s activities (Baum and Potter, 2008).

Government – regulatory stakeholders

Legal entities, such as companies, are formed for a specific purpose and are allowed to operate

within the legal framework of specified jurisdiction(s), with interactions regulated by government. To

maintain their operations, companies must behave in a legally and socially acceptable fashion. A key

area of legal concern in regard to corporate conduct relates to strategies and activities associated

with accurately communicating with their stakeholders (Kerr et al., 2008). Claiming to be socially

responsible is, increasingly, being used as a marketing claim (Hoeffler et al., 2010), and the accuracy

of these claims needs to be regulated to ensure consumers are not intentionally or unintentionally

misled.

Governments are also involved with corporate social activities as part of their governing function

and have a range of tools for facilitating the collaboration between themselves, businesses and the

civil society (Moon, 2004; Albareda et al., 2008). Therefore, governments at all levels, potentially,

have substantial influence on management’s decision making and corporate behavior, directly and‐

indirectly, through shaping the wider legal and regulatory framework within which managers’ work.

For example, how tax incentives are offered may encourage firms to undertake a range of socially

focused activities.

interest groups. Their perceptions of a company reflect the firm’s status and reputation (Neville et

al., 2005), as well as how the firm is positioned in respect to other organizations. Community groups’

perceptions are formed through long term corporate communications, their experience with the‐

firm and its products, as well as their perceptions of an organization’s societal impacts (Hoeffler et

al., 2010). The community plays many roles including as consumers, where consumers have a direct

impact on corporate action. For example, consumers can boycott firms because of their unethical

behavior, as this represents a lack of socially responsible activities (Klein et al., 2004). Perceived

inappropriate corporate actions can have long term consequences, affecting both corporate‐

reputation and firm performance. For example, Nestlé is still being punished by some consumers

over its activities in regards to the questionable promoting of infant formula in developing countries

two decades earlier (Boyd, 2012). Of course, community groups also have the ability to indirectly

influence others through the media as well. As was identified earlier, Shell changed their decision to

sink the Brent Spar oil rig because of global community protests (Wheeler et al., 2002;

Zyglidopoulos, 2002).

Media

The role of the media is to inform the wider community about issues of public interest. A neutral and

unbiased media can, however, also shape public opinion (Bodemer et al., 2012; Haddock Fraser,‐

2012). The media are indirect external stakeholders operating independently of the organization.

The media is an essential facilitator of communication between the firm and its stakeholders

(Deephouse and Heugend, 2009). The media’s support for a firm can be gained through maintaining

ongoing contacts and providing newsworthy information. However, firms cannot control the media,

thus support will be variable. The media, therefore, have the power to shape other stakeholders’

perceptions about an organization’s activities (Baum and Potter, 2008).

Government – regulatory stakeholders

Legal entities, such as companies, are formed for a specific purpose and are allowed to operate

within the legal framework of specified jurisdiction(s), with interactions regulated by government. To

maintain their operations, companies must behave in a legally and socially acceptable fashion. A key

area of legal concern in regard to corporate conduct relates to strategies and activities associated

with accurately communicating with their stakeholders (Kerr et al., 2008). Claiming to be socially

responsible is, increasingly, being used as a marketing claim (Hoeffler et al., 2010), and the accuracy

of these claims needs to be regulated to ensure consumers are not intentionally or unintentionally

misled.

Governments are also involved with corporate social activities as part of their governing function

and have a range of tools for facilitating the collaboration between themselves, businesses and the

civil society (Moon, 2004; Albareda et al., 2008). Therefore, governments at all levels, potentially,

have substantial influence on management’s decision making and corporate behavior, directly and‐

indirectly, through shaping the wider legal and regulatory framework within which managers’ work.

For example, how tax incentives are offered may encourage firms to undertake a range of socially

focused activities.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Corporate reputation

Corporate actions related to socially responsible activities (and irresponsible actions) have the ability

to influence the reputation and performance of a company (Boyd et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2010; Lii and

Lee, 2012). Reputation helps shape consumer attitudes and perceptions about a company (Fombrun

and Shanley, 1990), with positive perceptions motivating consumer purchase and developing

positive brand associations (Neville et al., 2005).

The inclusion of “corporate reputation” as an intervening variable between CSR measure and

organizational performance indicators is a recognition that some consumer purchases are influenced

by the firm’s reputation (Du et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2010; Lii and Lee, 2012). This is increasingly

recognized by firms that strategically use CSR to alter their positioning in the market. The purpose of

using “corporate reputation” as an intervening variable is to determine the extent to which

organizational reputation may be attributed to CSR and to what extent it is associated with

organizational performance (market share) (Peloza and Shang, 2011; Spitzeck and Hansen, 2010).

Several definitions have been provided for corporate reputation (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Weiss

et al., 1999). Fombrun (1996, p. 72) defined reputation as “a perceptual representation of a

company’s past actions and future prospects that describes the firm’s overall appeal of its key

constituents when compared with other leading rivals”. Corporate reputation can, therefore, be

characterized as the stakeholders’ evaluation of a company on key performance dimensions. This

definition proposes that a reputation is the synthesis of stakeholders’ perceptions and creates a

persona that can be formulated, implemented and managed (Neville et al., 2005).

In this study, corporate reputation is regarded as managers’ perceptions of how well the

organization meets the needs of its stakeholders, which is consistent with the definition offered by

Wartick (1992, p. 34) as “the aggregation of a single stakeholder’s perception of how well

organizational responses are meeting the demand and expectations of many organizational

stakeholders”. A managerial focused definition of reputation is possibly more realistic and functional‐

because it considers a holistic viewpoint of one stakeholder group in regard to how the firm

interacts with its other stakeholders. Relying on senior management perspectives is also

appropriate, as managers engage with all the organization’s stakeholders through a variety of formal

and informal exchanges, as well as shaping strategies that are based on the managers’ assessments

of stakeholders’ importance (Ferrell et al., 2010). It may be argued that as each stakeholder has

varying corporate expectations and attitudes, their interpretations and perceptions of a company’s

activities would differ. Therefore, aggregating the perceptions of all key stakeholders may result in

an inaccurate measure of corporate reputation, which is not reflective of any individual stakeholder

group (Polonsky and Scott, 2005).

The impact of CSR activities on corporate reputation is measured by managers’ perceptions of how

an organization is being perceived across a set of stakeholders in general, rather than by each

specific stakeholder, which is often done when assessing strategy related issues (Maignan et al.,‐

2011). This managerial perspective identifies the dimensions and attributes of corporate self‐

perception, reflecting what the management believes stakeholders consider as realistic, meaningful

and long lasting.‐

Corporate actions related to socially responsible activities (and irresponsible actions) have the ability

to influence the reputation and performance of a company (Boyd et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2010; Lii and

Lee, 2012). Reputation helps shape consumer attitudes and perceptions about a company (Fombrun

and Shanley, 1990), with positive perceptions motivating consumer purchase and developing

positive brand associations (Neville et al., 2005).

The inclusion of “corporate reputation” as an intervening variable between CSR measure and

organizational performance indicators is a recognition that some consumer purchases are influenced

by the firm’s reputation (Du et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2010; Lii and Lee, 2012). This is increasingly

recognized by firms that strategically use CSR to alter their positioning in the market. The purpose of

using “corporate reputation” as an intervening variable is to determine the extent to which

organizational reputation may be attributed to CSR and to what extent it is associated with

organizational performance (market share) (Peloza and Shang, 2011; Spitzeck and Hansen, 2010).

Several definitions have been provided for corporate reputation (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Weiss

et al., 1999). Fombrun (1996, p. 72) defined reputation as “a perceptual representation of a

company’s past actions and future prospects that describes the firm’s overall appeal of its key

constituents when compared with other leading rivals”. Corporate reputation can, therefore, be

characterized as the stakeholders’ evaluation of a company on key performance dimensions. This

definition proposes that a reputation is the synthesis of stakeholders’ perceptions and creates a

persona that can be formulated, implemented and managed (Neville et al., 2005).

In this study, corporate reputation is regarded as managers’ perceptions of how well the

organization meets the needs of its stakeholders, which is consistent with the definition offered by

Wartick (1992, p. 34) as “the aggregation of a single stakeholder’s perception of how well

organizational responses are meeting the demand and expectations of many organizational

stakeholders”. A managerial focused definition of reputation is possibly more realistic and functional‐

because it considers a holistic viewpoint of one stakeholder group in regard to how the firm

interacts with its other stakeholders. Relying on senior management perspectives is also

appropriate, as managers engage with all the organization’s stakeholders through a variety of formal

and informal exchanges, as well as shaping strategies that are based on the managers’ assessments

of stakeholders’ importance (Ferrell et al., 2010). It may be argued that as each stakeholder has

varying corporate expectations and attitudes, their interpretations and perceptions of a company’s

activities would differ. Therefore, aggregating the perceptions of all key stakeholders may result in

an inaccurate measure of corporate reputation, which is not reflective of any individual stakeholder

group (Polonsky and Scott, 2005).

The impact of CSR activities on corporate reputation is measured by managers’ perceptions of how

an organization is being perceived across a set of stakeholders in general, rather than by each

specific stakeholder, which is often done when assessing strategy related issues (Maignan et al.,‐

2011). This managerial perspective identifies the dimensions and attributes of corporate self‐

perception, reflecting what the management believes stakeholders consider as realistic, meaningful

and long lasting.‐

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Business performance

The impact of CSR activities on corporate reputation leads to business performance (Berman et al.,

1999; Lai et al., 2010). Business performance is a complicated concept to assess, given the various

ways it can be measured and the factors that can influence it (Clark et al., 2006; de Waal, 2002).

Performance may be considered, generally, as the corporate results achieved, or a change in results

through the implementation of targeted strategies (de Waal, 2002). Business performance may also

be viewed as the degree to which an organization has achieved its own set of defined objectives

(Dieckman, 2001). Business performance can also be assessed in relation to industry norms, the

historical firm performance or the established objectives and expectations of the organization

(Herremans and Ryans, 1995; Homburg et al., 1999). An organization’s defined objectives and

expectations could include different measures, such as the level of customer satisfaction,

profitability, market share, sales value and sales volume (Gustafsson and Johnson, 2002), just to

mention a few. In this study, business performance is considered as a subjective assessment by

managers of the change in market share and change in profitability, rather than an absolute

measure of performance. This approach is appropriate, as managers have been found to be effective

in making subjective assessments of changes in corporate performance (Harris, 2001; Narver and

Slater, 1990; Slater and Narver, 1996).

From the above review of the literature surrounding CSR, and the roles and responsibility of the

relevant stakeholders influencing the conduct of a business, the following research questions

emerge:

RQ1. Can CSR as a strategic focus be represented as a latent variable formed by managers’

perceptions of their stakeholders’ influences on corporate decision making?‐

RQ2. Is there an association between the levels of CSR focus and organizational reputation?

RQ3. Is there an association between organizational reputation and the business

performance indicators of: (a) change in market share; and (b) change in overall profitability

performance?

To address the above research questions, a model (see Figure 1) is proposed which suggests that

various stakeholders contribute to corporate CSR, the reputation of the organization and business

performance.

Model components

The model of CSR (Figure 1) is constructed such that there are multiple stakeholder influences

occurring simultaneously. The constituent factors in the model are designed to represent a multi‐

faceted structure of stakeholders’ influences which shape management’s decision making.‐

The model indicates that these factors, potentially, interact and create a synergistic outcome that

determines the relative strength of the organization’s CSR and, in turn, reputation, and through this,

the firm’s performance. CSR is measured as the overall influence of key stakeholders directly

relevant to an organization, as discussed previously.

Within the model, the “community in general” and “local residents” groups have been integrated

into one “public” stakeholder group. The data on the influence of these two groups were collected

separately; however, the variables of the two groups were highly correlated (76.6) and, therefore,

were integrated to avoid repetition while maintaining their representation in the model (Figure 1).

The impact of CSR activities on corporate reputation leads to business performance (Berman et al.,

1999; Lai et al., 2010). Business performance is a complicated concept to assess, given the various

ways it can be measured and the factors that can influence it (Clark et al., 2006; de Waal, 2002).

Performance may be considered, generally, as the corporate results achieved, or a change in results

through the implementation of targeted strategies (de Waal, 2002). Business performance may also

be viewed as the degree to which an organization has achieved its own set of defined objectives

(Dieckman, 2001). Business performance can also be assessed in relation to industry norms, the

historical firm performance or the established objectives and expectations of the organization

(Herremans and Ryans, 1995; Homburg et al., 1999). An organization’s defined objectives and

expectations could include different measures, such as the level of customer satisfaction,

profitability, market share, sales value and sales volume (Gustafsson and Johnson, 2002), just to

mention a few. In this study, business performance is considered as a subjective assessment by

managers of the change in market share and change in profitability, rather than an absolute

measure of performance. This approach is appropriate, as managers have been found to be effective

in making subjective assessments of changes in corporate performance (Harris, 2001; Narver and

Slater, 1990; Slater and Narver, 1996).

From the above review of the literature surrounding CSR, and the roles and responsibility of the

relevant stakeholders influencing the conduct of a business, the following research questions

emerge:

RQ1. Can CSR as a strategic focus be represented as a latent variable formed by managers’

perceptions of their stakeholders’ influences on corporate decision making?‐

RQ2. Is there an association between the levels of CSR focus and organizational reputation?

RQ3. Is there an association between organizational reputation and the business

performance indicators of: (a) change in market share; and (b) change in overall profitability

performance?

To address the above research questions, a model (see Figure 1) is proposed which suggests that

various stakeholders contribute to corporate CSR, the reputation of the organization and business

performance.

Model components

The model of CSR (Figure 1) is constructed such that there are multiple stakeholder influences

occurring simultaneously. The constituent factors in the model are designed to represent a multi‐

faceted structure of stakeholders’ influences which shape management’s decision making.‐

The model indicates that these factors, potentially, interact and create a synergistic outcome that

determines the relative strength of the organization’s CSR and, in turn, reputation, and through this,

the firm’s performance. CSR is measured as the overall influence of key stakeholders directly

relevant to an organization, as discussed previously.

Within the model, the “community in general” and “local residents” groups have been integrated

into one “public” stakeholder group. The data on the influence of these two groups were collected

separately; however, the variables of the two groups were highly correlated (76.6) and, therefore,

were integrated to avoid repetition while maintaining their representation in the model (Figure 1).

Corporate reputation is included in the model as an intervening variable between CSR and business

performance (Neville et al., 2005). This is done because of the focal role of corporate reputation in

performance and marketing outcomes (Lai et al., 2010; Tsoutsoura, 2004). Reputation is designed to

measure the association between corporate reputation and business performance indicators

(change in market share and profitability).

The market share measure is assessed based on respondents’ perceived change in the share of the

market by the strategic business unit in comparison to the previous year, and is not intended to be

product or market specific. It reflects the managers’ perception of the extent of the overall change‐

in the organization’s market share, that is, the firm’s strength in their target market (Hooley et al.,

2005). “Profit” is also measured based on respondents’ perception of the change in profits from the

previous year. Thus, the performance measures used in the study reflect the perceived effectiveness

of CSR, as well as the ability of the organization to respond to environmental change (Homburg et

al., 1999).

The inclusion of these two performance measures enables a comparison between:

1. a measure that, predominantly, reflects the influence of marketing decisions, that is,

changes in market share; and

2. changes in the profit of the organization, representing the results of the entire

organization’s activities, which is also important, as stakeholders have different interests in

corporate activities (Polonsky and Scott, 2005).

Including multiple outcome measures allows a comparison between the marketing and non‐

marketing indicators in regard to the benefits of CSR.

The key assumptions in the construction of this model are that:

the reputation of an organization influences its level of success in achieving its business

performance objectives (Boyd et al., 2010);

CSR strategy may contribute to a positive corporate reputation (Bertels and Peloza, 2008);

and

CSR strategy can influence business performance through corporate reputation (Ben Brik et

al., 2011).

Method

A mail survey was designed and conducted to investigate the research questions and test the

proposed model of CSR. The questionnaire was developed based on the CSR literature and the

stakeholder theory (Agle et al., 1999; Turker, 2009). The items assessing senior managers’

perceptions of corporate reputation (Caruna, 1997; Caruna and Chircop, 2000; Helm, 2005), and

performance (Hooley et al., 2005) were adopted from existing studies.

The research instrument was modified through a two stage pre test process. The first stage included‐ ‐

review by six senior managers to verify the relevance of the items included and recommend items

that required changes. Minor changes were suggested and made to the wording and sequence of

some items, where considered appropriate, and the modified version of the instrument was re‐

tested using a different panel of six senior marketing managers (Wren, 1997).

performance (Neville et al., 2005). This is done because of the focal role of corporate reputation in

performance and marketing outcomes (Lai et al., 2010; Tsoutsoura, 2004). Reputation is designed to

measure the association between corporate reputation and business performance indicators

(change in market share and profitability).

The market share measure is assessed based on respondents’ perceived change in the share of the

market by the strategic business unit in comparison to the previous year, and is not intended to be

product or market specific. It reflects the managers’ perception of the extent of the overall change‐

in the organization’s market share, that is, the firm’s strength in their target market (Hooley et al.,

2005). “Profit” is also measured based on respondents’ perception of the change in profits from the

previous year. Thus, the performance measures used in the study reflect the perceived effectiveness

of CSR, as well as the ability of the organization to respond to environmental change (Homburg et

al., 1999).

The inclusion of these two performance measures enables a comparison between:

1. a measure that, predominantly, reflects the influence of marketing decisions, that is,

changes in market share; and

2. changes in the profit of the organization, representing the results of the entire

organization’s activities, which is also important, as stakeholders have different interests in

corporate activities (Polonsky and Scott, 2005).

Including multiple outcome measures allows a comparison between the marketing and non‐

marketing indicators in regard to the benefits of CSR.

The key assumptions in the construction of this model are that:

the reputation of an organization influences its level of success in achieving its business

performance objectives (Boyd et al., 2010);

CSR strategy may contribute to a positive corporate reputation (Bertels and Peloza, 2008);

and

CSR strategy can influence business performance through corporate reputation (Ben Brik et

al., 2011).

Method

A mail survey was designed and conducted to investigate the research questions and test the

proposed model of CSR. The questionnaire was developed based on the CSR literature and the

stakeholder theory (Agle et al., 1999; Turker, 2009). The items assessing senior managers’

perceptions of corporate reputation (Caruna, 1997; Caruna and Chircop, 2000; Helm, 2005), and

performance (Hooley et al., 2005) were adopted from existing studies.

The research instrument was modified through a two stage pre test process. The first stage included‐ ‐