Medieval Christian Art: Analyzing the Evolution of God's Depiction

VerifiedAdded on 2020/12/07

|10

|2773

|341

Essay

AI Summary

This essay analyzes the evolution of the depictions of God in Medieval Christian art, starting from the early, ambiguous representations influenced by pagan culture to the more defined iconography that emerged with the legalization of Christianity under Constantine. The paper examines significant changes and trends throughout the Middle Ages, including the Byzantine period and the Iconoclastic controversy, and evaluates the artistic significance of different works, focusing on the visual forms of God the Father (represented by the Hand of God), God the Son (often depicted as the Good Shepherd or Christ Enthroned), and the Holy Spirit (symbolized by a dove). It highlights how theological interpretations and social-political forces shaped the artistic representations of the Holy Trinity. The essay further discusses the standardization of religious subjects, the prohibition of God the Father's human form until the 10th century, the appropriation of pagan symbols, and the evolving depictions of Jesus Christ. The essay concludes by acknowledging the limitations of its scope and briefly mentioning subsequent theological debates and architectural trends. The paper emphasizes how the iconography of the Deity demonstrates changing theological understandings and how incredibly complex symbolism in Christian art interacted with.

Keeling 1

Katilynn Keeling

Prof. William Tronzo

VIS 121C

21 November 2020

Essay #2

Depictions of God in the period of Medieval Christian art bears a significance of the

important theological interpretations that evolved over time. To better understand the

complicated, overlapping, and incomplete timeline of Christian art, this paper will briefly

summarize what were significant changes and trends in Christian art throughout the Middle

Ages and will evaluate the artistic significance of different works of Byzantine Christian art,

looking at examples of the visual forms of God in art- referring separately the Holy Trinity: God

the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Before the rule of Constantine in the 3rd century, the enforced persecution of Christians

significantly impacted the ability to freely create meaningful religious art. Instead, early Christian

art was deliberately ambiguous- borrowing from the pagan culture and placing new meanings

into their symbolic interpretations (Syndicus, p. 30, 1962). However, the extravagant artistry of

classical pagan art contrasted the desire of early Christians whose art was not meant to be

glorified or idolized- viewing it as misappropriated worship of things other than the Creator

(Stephan & Sullivan, 2020). Exodus 20:4-5 reads, “4You shall not make for yourself a carved

image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that

is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the Lord

your God, am a jealous God” (NKJV). Early Christian art distinguished themselves from the

Pagans and idol worship by borrowing iconography plainly, then later, characterizing it so that

“[it did] not put the scenes it portrays in an earthly, finite perspective. The figures [stood] flat and

incorporeal on bright backgrounds… thereby [taking] on an unearthly quality…. The pictures are

Katilynn Keeling

Prof. William Tronzo

VIS 121C

21 November 2020

Essay #2

Depictions of God in the period of Medieval Christian art bears a significance of the

important theological interpretations that evolved over time. To better understand the

complicated, overlapping, and incomplete timeline of Christian art, this paper will briefly

summarize what were significant changes and trends in Christian art throughout the Middle

Ages and will evaluate the artistic significance of different works of Byzantine Christian art,

looking at examples of the visual forms of God in art- referring separately the Holy Trinity: God

the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Before the rule of Constantine in the 3rd century, the enforced persecution of Christians

significantly impacted the ability to freely create meaningful religious art. Instead, early Christian

art was deliberately ambiguous- borrowing from the pagan culture and placing new meanings

into their symbolic interpretations (Syndicus, p. 30, 1962). However, the extravagant artistry of

classical pagan art contrasted the desire of early Christians whose art was not meant to be

glorified or idolized- viewing it as misappropriated worship of things other than the Creator

(Stephan & Sullivan, 2020). Exodus 20:4-5 reads, “4You shall not make for yourself a carved

image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that

is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the Lord

your God, am a jealous God” (NKJV). Early Christian art distinguished themselves from the

Pagans and idol worship by borrowing iconography plainly, then later, characterizing it so that

“[it did] not put the scenes it portrays in an earthly, finite perspective. The figures [stood] flat and

incorporeal on bright backgrounds… thereby [taking] on an unearthly quality…. The pictures are

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Keeling 2

signposts, informative rather than beautiful…” (Syndicus, p 30, 1962). Holy representations,

therefore, were mostly limited to abstraction and portrayals of artistic metaphors and symbols

that called on followers to interact with the meanings behind the icons, rather than to idolize the

representation of the icons themselves...

By the late 2nd Century, incipient pictorial art began to make an appearance. It is

important to note that the ‘starting point’ of Christian pictorial art-

“lies in the basic teaching of the Christian revelation itself- namely, the

incarnation, the point at which the Christian proclamation is different from

Judaism. The incarnation of the Son of man, the Messiah, in the form of a human

being- who was created in the “image of God”- granted theological approval of a

sort to use the images that symbolized Christan truths” (Stephan & Sullivan).

The 4th Century became marked by Constantine’s support and legalization of Christianity,

freeing them from religious persecution. The Church grew (wealthier), and theological

perspectives pushed Christian iconographic art to become more widely accepted as it

symbolized testament to the faith, rather than seen as iconographic representations to be

worshipped. Narrative-based art could now be freely made according to Christianity (though

borrowed pagan icons/symbols were now fixed into Christian symbolism) and individual portraits

of Jesus originated and grew more elaborate.

Christian art expanded over the 6th and 7th Centuries and ushered in the First Golden

Age of Byzantine art (Demus, p. xiv, 1955). Magnificent churches were erected and lavishly

decorated with religious art which “served as spiritual gateways” (Hurst, 2004). However, the 8th

and 9th centuries became notably defined as the Byzantine Iconoclastic Period, in which social

and political upheavals, led by Emperor Leo III (and his later successor), divided the Orthodox

church regarding theological interpretations of the Old Testament Ten Commandments which

forbade the worship of “graven images” (“Iconoclastic Controversy”). The Church remained

mostly in support of religious iconographic art throughout these periods of divisiveness;

signposts, informative rather than beautiful…” (Syndicus, p 30, 1962). Holy representations,

therefore, were mostly limited to abstraction and portrayals of artistic metaphors and symbols

that called on followers to interact with the meanings behind the icons, rather than to idolize the

representation of the icons themselves...

By the late 2nd Century, incipient pictorial art began to make an appearance. It is

important to note that the ‘starting point’ of Christian pictorial art-

“lies in the basic teaching of the Christian revelation itself- namely, the

incarnation, the point at which the Christian proclamation is different from

Judaism. The incarnation of the Son of man, the Messiah, in the form of a human

being- who was created in the “image of God”- granted theological approval of a

sort to use the images that symbolized Christan truths” (Stephan & Sullivan).

The 4th Century became marked by Constantine’s support and legalization of Christianity,

freeing them from religious persecution. The Church grew (wealthier), and theological

perspectives pushed Christian iconographic art to become more widely accepted as it

symbolized testament to the faith, rather than seen as iconographic representations to be

worshipped. Narrative-based art could now be freely made according to Christianity (though

borrowed pagan icons/symbols were now fixed into Christian symbolism) and individual portraits

of Jesus originated and grew more elaborate.

Christian art expanded over the 6th and 7th Centuries and ushered in the First Golden

Age of Byzantine art (Demus, p. xiv, 1955). Magnificent churches were erected and lavishly

decorated with religious art which “served as spiritual gateways” (Hurst, 2004). However, the 8th

and 9th centuries became notably defined as the Byzantine Iconoclastic Period, in which social

and political upheavals, led by Emperor Leo III (and his later successor), divided the Orthodox

church regarding theological interpretations of the Old Testament Ten Commandments which

forbade the worship of “graven images” (“Iconoclastic Controversy”). The Church remained

mostly in support of religious iconographic art throughout these periods of divisiveness;

Keeling 3

however, theological shifts shaped by the Iconoclastic debate helped establish a set of rules

and expectations for Christian art. The standardization of what and how a religious subject was

to be presented “[did] not aim at evoking the emotions of pity, fear or hope... The pictures make

their appeal to the beholder not as an individual human being, a soul to be saved, but as a

member of the Church, with his own assigned place in the hierarchical organization” (Demus, pp

4-5).

This brief history sheds light on Byzantine art and illuminates the veneration of holy

icons but, most importantly, as religious iconography grew more widely accepted,

representations of God the Father remained prohibited, for “18no one has seen God at any time”

(John 1:18, NKJV). Artistic metaphors were implemented and standardized in this way. Most

frequently, the Hand of God was used to represent divine intervention or approval. This imagery

embodies hundreds of verses in Scripture which involve the hand of God such as; Isaiah 41:40 -

“Fear not for I am with you; be not dismayed...I will strengthen you, I will uphold you with my

righteous right hand” (NKJV), and “Was it not My hand which made all these things?” (Acts 7:50

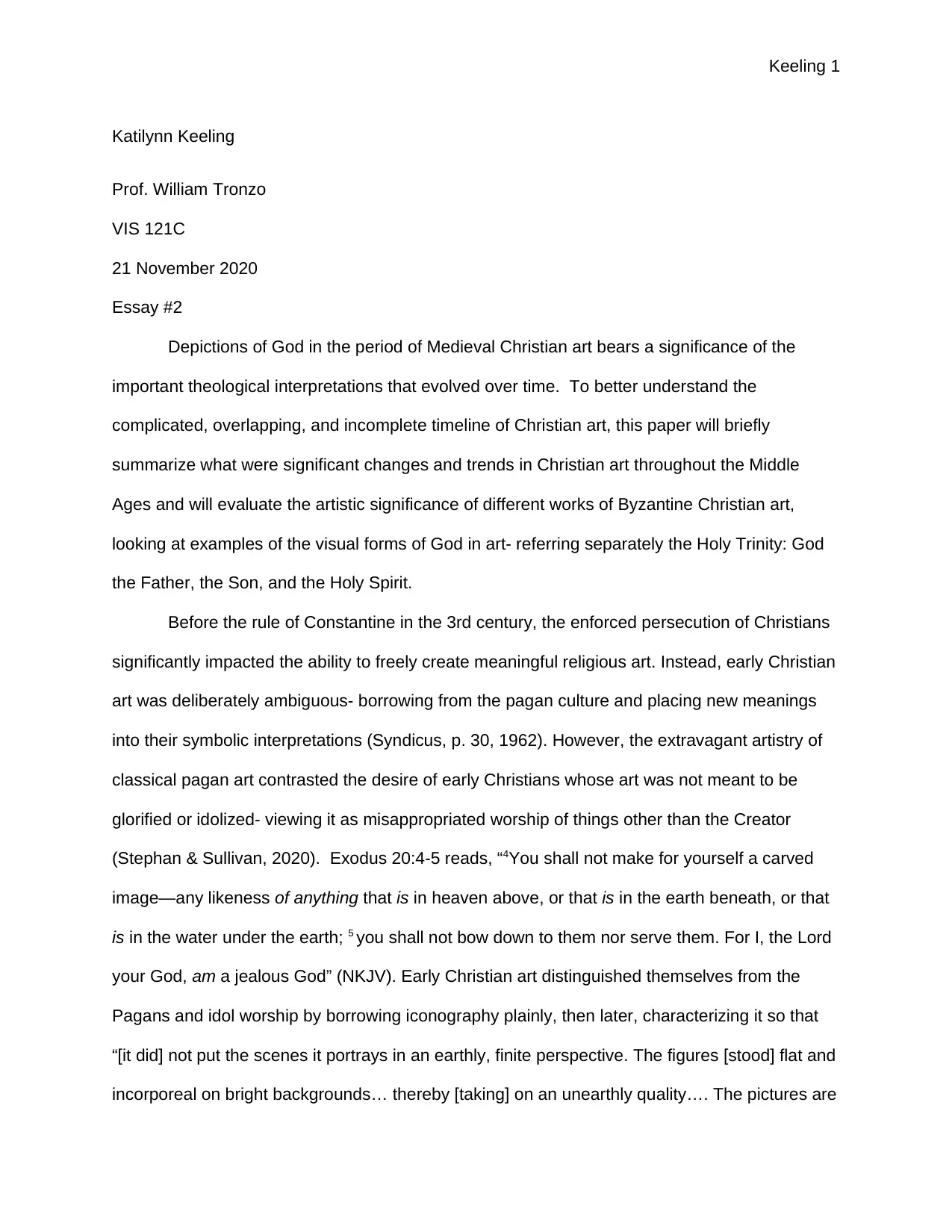

NKJV). Thus, God the Father is not seen documented until the 6th century on. A later example

is the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, circa 870 A.D. (Figure 1.1), a manuscript made for the

Carolingian King Charles the Bald (Pizzinato, p.145, 2018). While this image has a lot to

dissect, we will remain focused on the depiction of God. Here, the Hand of God emerges from

the heavens, positioned downward and outstretched as it hovers above the king’s head to

inform of God’s divine sanctioning of the king. Emphasis is placed on this symbolism by

enforcing it within the focal point- a lush green sun, fringed with golden rays. In some other

instances, God has been depicted as a burning bush in reference to Exodus Chapter three-

where Moses is visited by God in the form of a bush on fire but not burning (Demus, p. 104).

Ultimately the iconographic depiction of God the Father remained prohibited and, “for about a

thousand years, no attempt was made to portray the First Person of the Holy Trinity in human

however, theological shifts shaped by the Iconoclastic debate helped establish a set of rules

and expectations for Christian art. The standardization of what and how a religious subject was

to be presented “[did] not aim at evoking the emotions of pity, fear or hope... The pictures make

their appeal to the beholder not as an individual human being, a soul to be saved, but as a

member of the Church, with his own assigned place in the hierarchical organization” (Demus, pp

4-5).

This brief history sheds light on Byzantine art and illuminates the veneration of holy

icons but, most importantly, as religious iconography grew more widely accepted,

representations of God the Father remained prohibited, for “18no one has seen God at any time”

(John 1:18, NKJV). Artistic metaphors were implemented and standardized in this way. Most

frequently, the Hand of God was used to represent divine intervention or approval. This imagery

embodies hundreds of verses in Scripture which involve the hand of God such as; Isaiah 41:40 -

“Fear not for I am with you; be not dismayed...I will strengthen you, I will uphold you with my

righteous right hand” (NKJV), and “Was it not My hand which made all these things?” (Acts 7:50

NKJV). Thus, God the Father is not seen documented until the 6th century on. A later example

is the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, circa 870 A.D. (Figure 1.1), a manuscript made for the

Carolingian King Charles the Bald (Pizzinato, p.145, 2018). While this image has a lot to

dissect, we will remain focused on the depiction of God. Here, the Hand of God emerges from

the heavens, positioned downward and outstretched as it hovers above the king’s head to

inform of God’s divine sanctioning of the king. Emphasis is placed on this symbolism by

enforcing it within the focal point- a lush green sun, fringed with golden rays. In some other

instances, God has been depicted as a burning bush in reference to Exodus Chapter three-

where Moses is visited by God in the form of a bush on fire but not burning (Demus, p. 104).

Ultimately the iconographic depiction of God the Father remained prohibited and, “for about a

thousand years, no attempt was made to portray the First Person of the Holy Trinity in human

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Keeling 4

form…. the human form of the Father finally [made] its appearance in and after the tenth

century” (Cornwell, 2009).

form…. the human form of the Father finally [made] its appearance in and after the tenth

century” (Cornwell, 2009).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Keeling 5

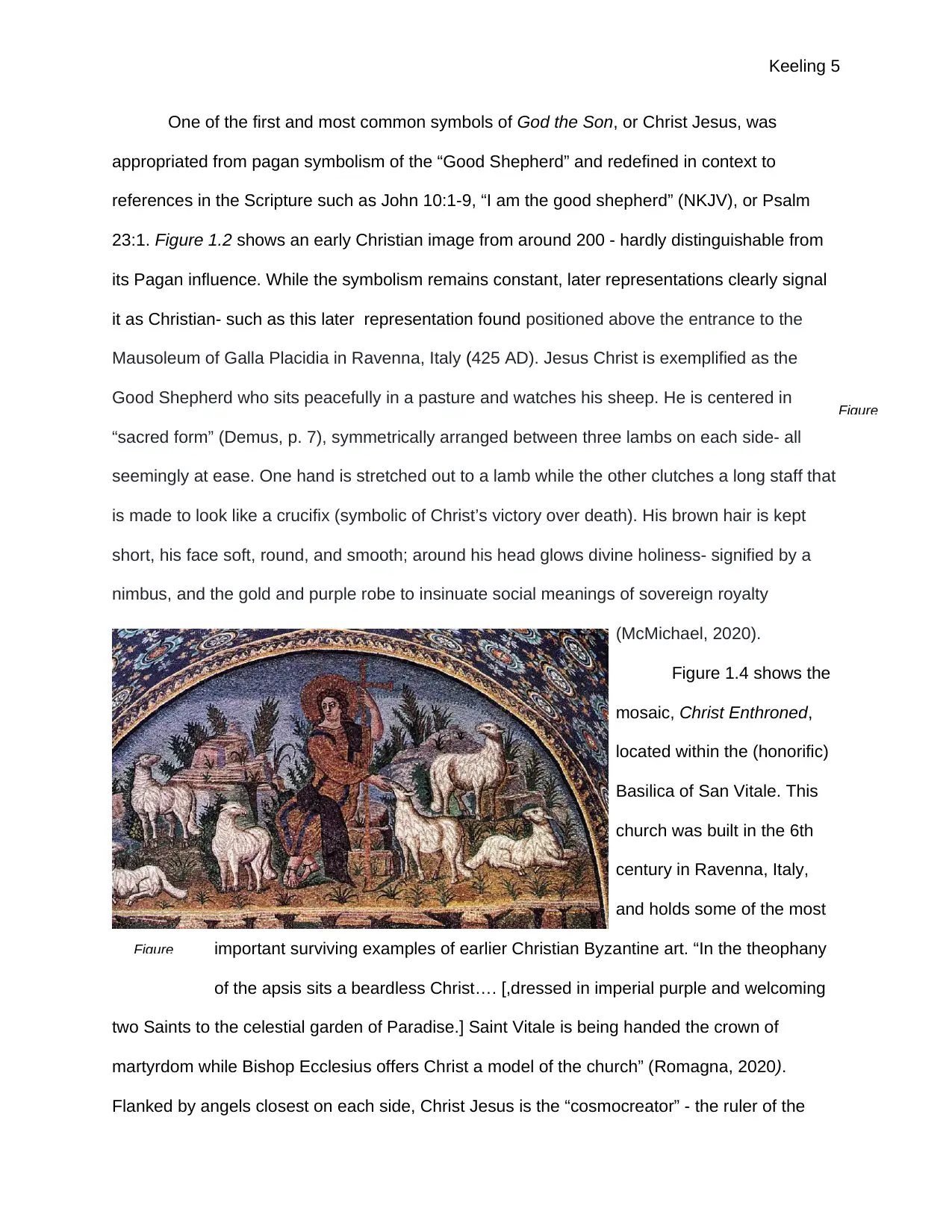

One of the first and most common symbols of God the Son, or Christ Jesus, was

appropriated from pagan symbolism of the “Good Shepherd” and redefined in context to

references in the Scripture such as John 10:1-9, “I am the good shepherd” (NKJV), or Psalm

23:1. Figure 1.2 shows an early Christian image from around 200 - hardly distinguishable from

its Pagan influence. While the symbolism remains constant, later representations clearly signal

it as Christian- such as this later representation found positioned above the entrance to the

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy (425 AD). Jesus Christ is exemplified as the

Good Shepherd who sits peacefully in a pasture and watches his sheep. He is centered in

“sacred form” (Demus, p. 7), symmetrically arranged between three lambs on each side- all

seemingly at ease. One hand is stretched out to a lamb while the other clutches a long staff that

is made to look like a crucifix (symbolic of Christ’s victory over death). His brown hair is kept

short, his face soft, round, and smooth; around his head glows divine holiness- signified by a

nimbus, and the gold and purple robe to insinuate social meanings of sovereign royalty

(McMichael, 2020).

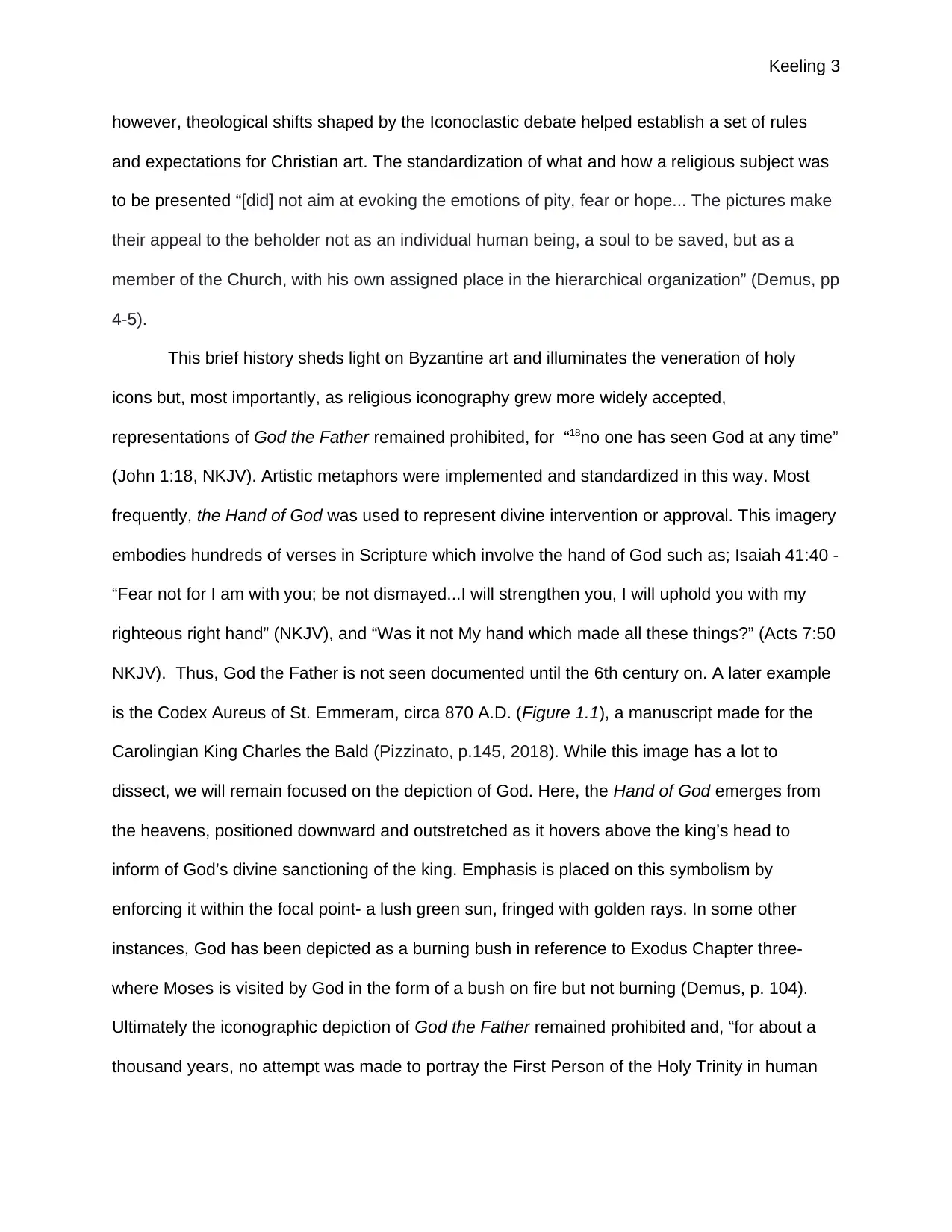

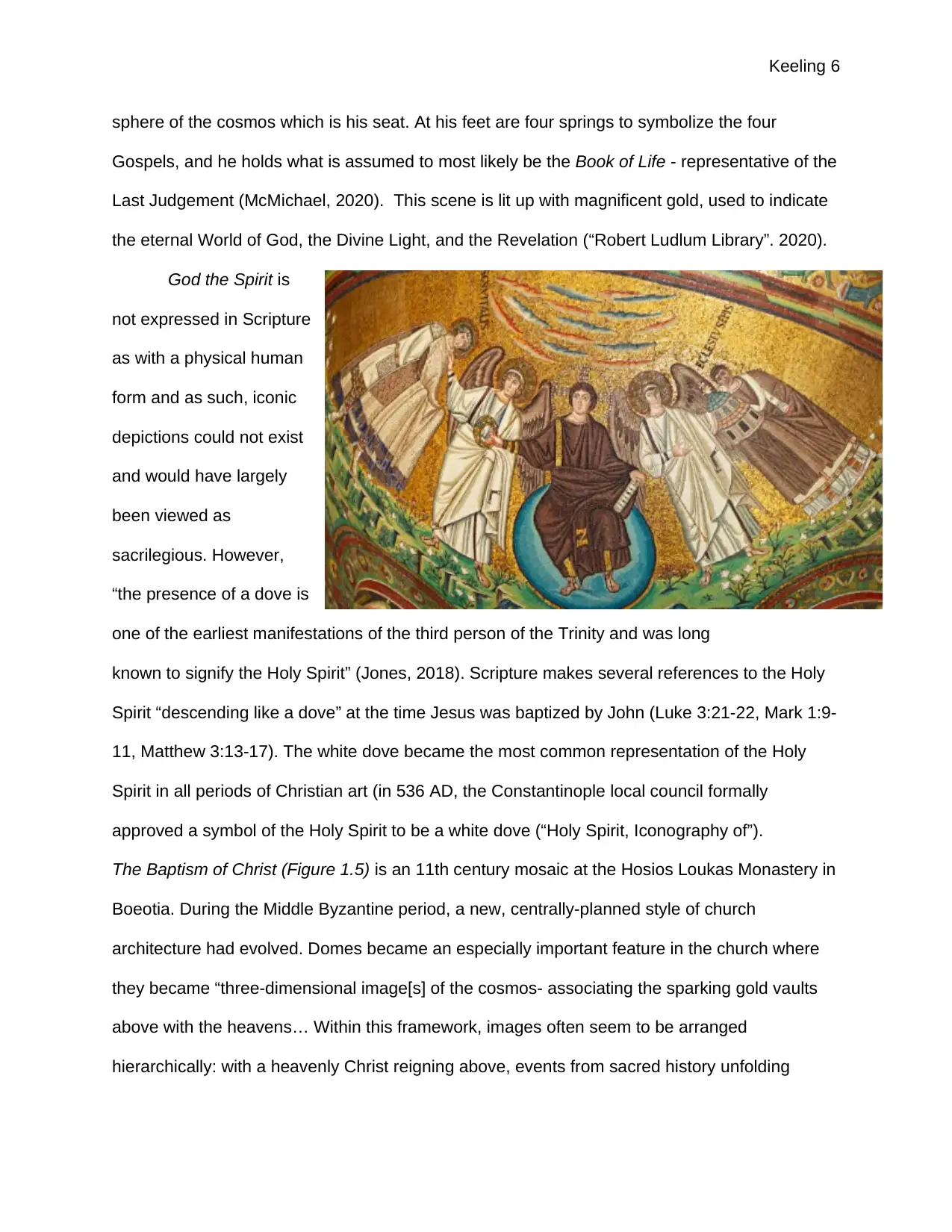

Figure 1.4 shows the

mosaic, Christ Enthroned,

located within the (honorific)

Basilica of San Vitale. This

church was built in the 6th

century in Ravenna, Italy,

and holds some of the most

important surviving examples of earlier Christian Byzantine art. “In the theophany

of the apsis sits a beardless Christ…. [,dressed in imperial purple and welcoming

two Saints to the celestial garden of Paradise.] Saint Vitale is being handed the crown of

martyrdom while Bishop Ecclesius offers Christ a model of the church” (Romagna, 2020).

Flanked by angels closest on each side, Christ Jesus is the “cosmocreator” - the ruler of the

Figure

Figure

One of the first and most common symbols of God the Son, or Christ Jesus, was

appropriated from pagan symbolism of the “Good Shepherd” and redefined in context to

references in the Scripture such as John 10:1-9, “I am the good shepherd” (NKJV), or Psalm

23:1. Figure 1.2 shows an early Christian image from around 200 - hardly distinguishable from

its Pagan influence. While the symbolism remains constant, later representations clearly signal

it as Christian- such as this later representation found positioned above the entrance to the

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy (425 AD). Jesus Christ is exemplified as the

Good Shepherd who sits peacefully in a pasture and watches his sheep. He is centered in

“sacred form” (Demus, p. 7), symmetrically arranged between three lambs on each side- all

seemingly at ease. One hand is stretched out to a lamb while the other clutches a long staff that

is made to look like a crucifix (symbolic of Christ’s victory over death). His brown hair is kept

short, his face soft, round, and smooth; around his head glows divine holiness- signified by a

nimbus, and the gold and purple robe to insinuate social meanings of sovereign royalty

(McMichael, 2020).

Figure 1.4 shows the

mosaic, Christ Enthroned,

located within the (honorific)

Basilica of San Vitale. This

church was built in the 6th

century in Ravenna, Italy,

and holds some of the most

important surviving examples of earlier Christian Byzantine art. “In the theophany

of the apsis sits a beardless Christ…. [,dressed in imperial purple and welcoming

two Saints to the celestial garden of Paradise.] Saint Vitale is being handed the crown of

martyrdom while Bishop Ecclesius offers Christ a model of the church” (Romagna, 2020).

Flanked by angels closest on each side, Christ Jesus is the “cosmocreator” - the ruler of the

Figure

Figure

Keeling 6

sphere of the cosmos which is his seat. At his feet are four springs to symbolize the four

Gospels, and he holds what is assumed to most likely be the Book of Life - representative of the

Last Judgement (McMichael, 2020). This scene is lit up with magnificent gold, used to indicate

the eternal World of God, the Divine Light, and the Revelation (“Robert Ludlum Library”. 2020).

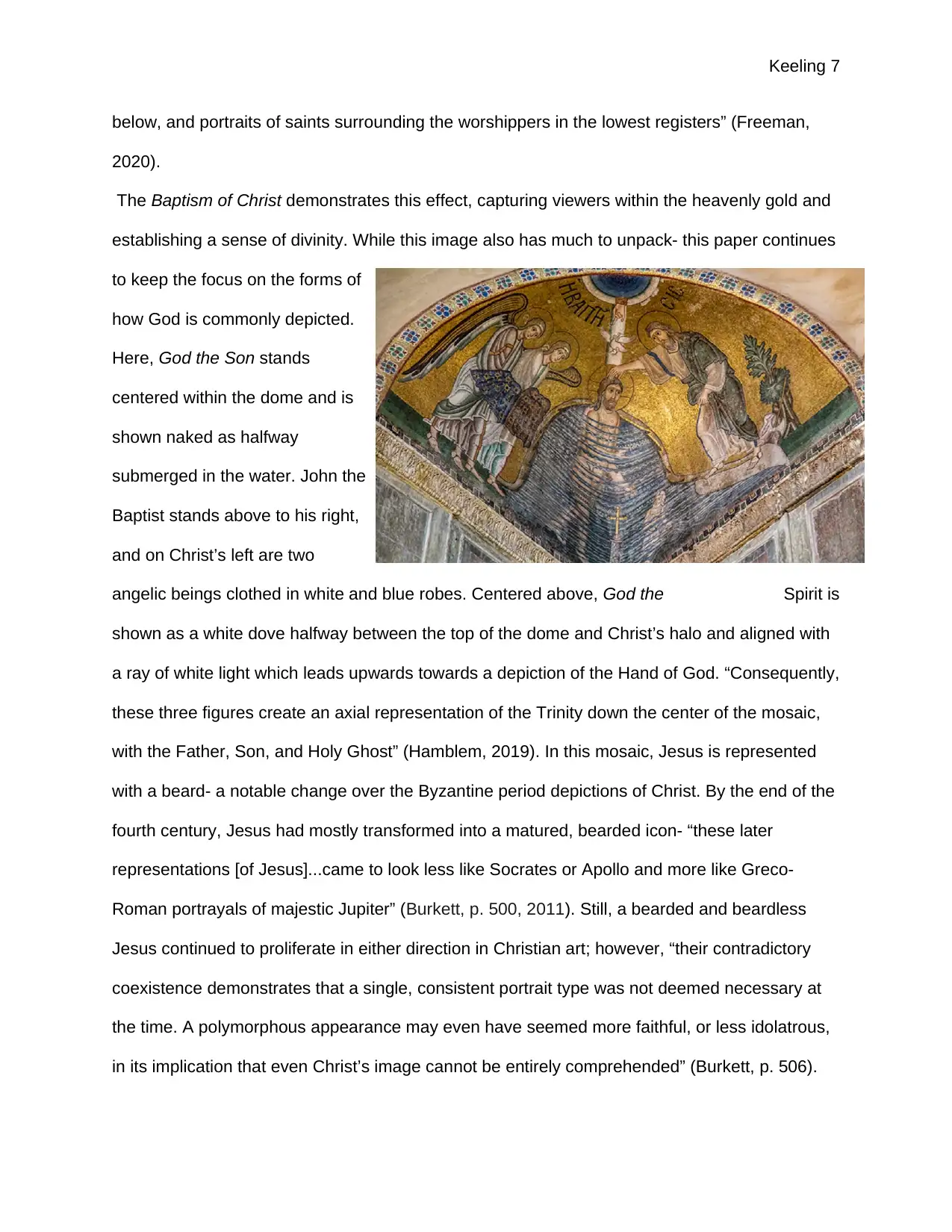

God the Spirit is

not expressed in Scripture

as with a physical human

form and as such, iconic

depictions could not exist

and would have largely

been viewed as

sacrilegious. However,

“the presence of a dove is

one of the earliest manifestations of the third person of the Trinity and was long

known to signify the Holy Spirit” (Jones, 2018). Scripture makes several references to the Holy

Spirit “descending like a dove” at the time Jesus was baptized by John (Luke 3:21-22, Mark 1:9-

11, Matthew 3:13-17). The white dove became the most common representation of the Holy

Spirit in all periods of Christian art (in 536 AD, the Constantinople local council formally

approved a symbol of the Holy Spirit to be a white dove (“Holy Spirit, Iconography of”).

The Baptism of Christ (Figure 1.5) is an 11th century mosaic at the Hosios Loukas Monastery in

Boeotia. During the Middle Byzantine period, a new, centrally-planned style of church

architecture had evolved. Domes became an especially important feature in the church where

they became “three-dimensional image[s] of the cosmos- associating the sparking gold vaults

above with the heavens… Within this framework, images often seem to be arranged

hierarchically: with a heavenly Christ reigning above, events from sacred history unfolding

sphere of the cosmos which is his seat. At his feet are four springs to symbolize the four

Gospels, and he holds what is assumed to most likely be the Book of Life - representative of the

Last Judgement (McMichael, 2020). This scene is lit up with magnificent gold, used to indicate

the eternal World of God, the Divine Light, and the Revelation (“Robert Ludlum Library”. 2020).

God the Spirit is

not expressed in Scripture

as with a physical human

form and as such, iconic

depictions could not exist

and would have largely

been viewed as

sacrilegious. However,

“the presence of a dove is

one of the earliest manifestations of the third person of the Trinity and was long

known to signify the Holy Spirit” (Jones, 2018). Scripture makes several references to the Holy

Spirit “descending like a dove” at the time Jesus was baptized by John (Luke 3:21-22, Mark 1:9-

11, Matthew 3:13-17). The white dove became the most common representation of the Holy

Spirit in all periods of Christian art (in 536 AD, the Constantinople local council formally

approved a symbol of the Holy Spirit to be a white dove (“Holy Spirit, Iconography of”).

The Baptism of Christ (Figure 1.5) is an 11th century mosaic at the Hosios Loukas Monastery in

Boeotia. During the Middle Byzantine period, a new, centrally-planned style of church

architecture had evolved. Domes became an especially important feature in the church where

they became “three-dimensional image[s] of the cosmos- associating the sparking gold vaults

above with the heavens… Within this framework, images often seem to be arranged

hierarchically: with a heavenly Christ reigning above, events from sacred history unfolding

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Keeling 7

below, and portraits of saints surrounding the worshippers in the lowest registers” (Freeman,

2020).

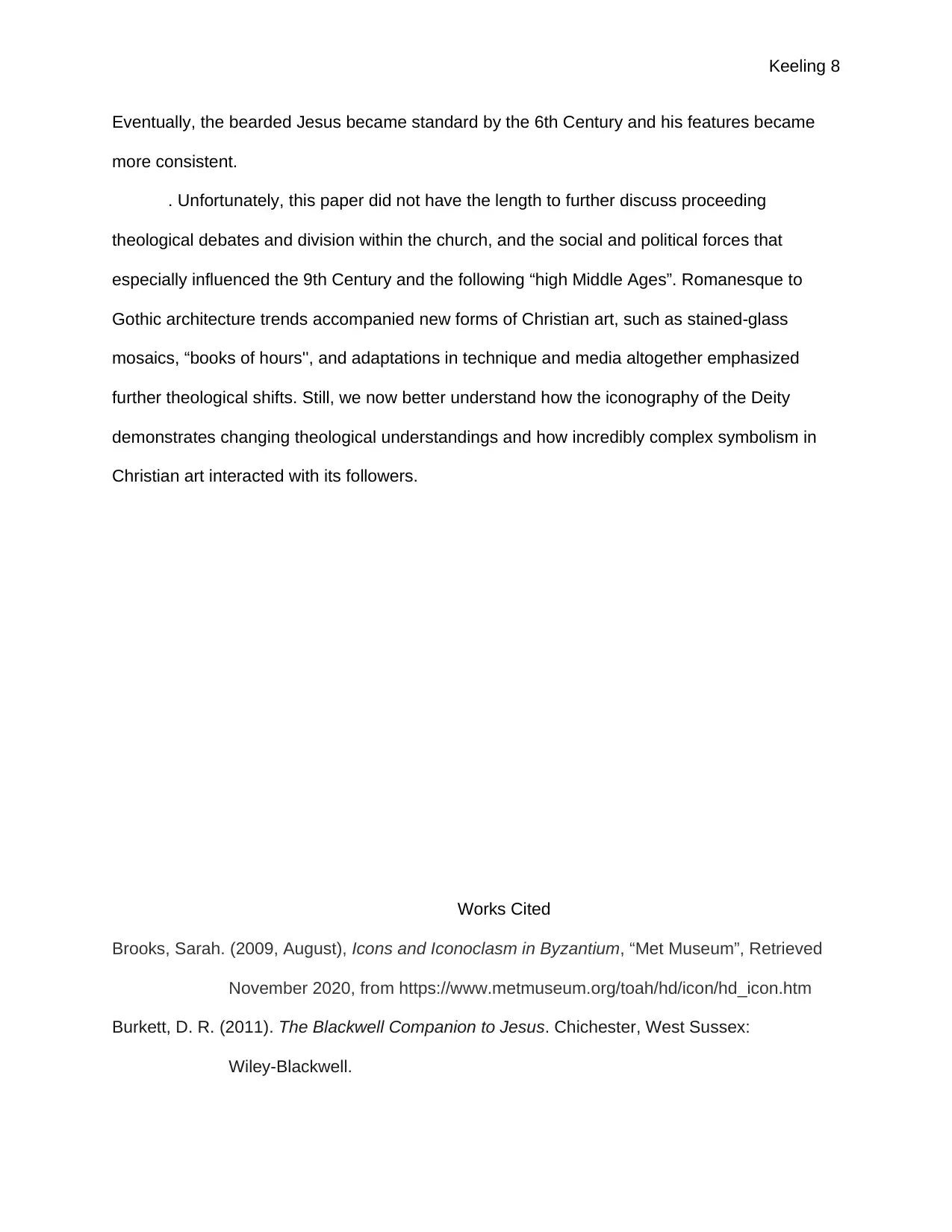

The Baptism of Christ demonstrates this effect, capturing viewers within the heavenly gold and

establishing a sense of divinity. While this image also has much to unpack- this paper continues

to keep the focus on the forms of

how God is commonly depicted.

Here, God the Son stands

centered within the dome and is

shown naked as halfway

submerged in the water. John the

Baptist stands above to his right,

and on Christ’s left are two

angelic beings clothed in white and blue robes. Centered above, God the Spirit is

shown as a white dove halfway between the top of the dome and Christ’s halo and aligned with

a ray of white light which leads upwards towards a depiction of the Hand of God. “Consequently,

these three figures create an axial representation of the Trinity down the center of the mosaic,

with the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” (Hamblem, 2019). In this mosaic, Jesus is represented

with a beard- a notable change over the Byzantine period depictions of Christ. By the end of the

fourth century, Jesus had mostly transformed into a matured, bearded icon- “these later

representations [of Jesus]...came to look less like Socrates or Apollo and more like Greco-

Roman portrayals of majestic Jupiter” (Burkett, p. 500, 2011). Still, a bearded and beardless

Jesus continued to proliferate in either direction in Christian art; however, “their contradictory

coexistence demonstrates that a single, consistent portrait type was not deemed necessary at

the time. A polymorphous appearance may even have seemed more faithful, or less idolatrous,

in its implication that even Christ’s image cannot be entirely comprehended” (Burkett, p. 506).

below, and portraits of saints surrounding the worshippers in the lowest registers” (Freeman,

2020).

The Baptism of Christ demonstrates this effect, capturing viewers within the heavenly gold and

establishing a sense of divinity. While this image also has much to unpack- this paper continues

to keep the focus on the forms of

how God is commonly depicted.

Here, God the Son stands

centered within the dome and is

shown naked as halfway

submerged in the water. John the

Baptist stands above to his right,

and on Christ’s left are two

angelic beings clothed in white and blue robes. Centered above, God the Spirit is

shown as a white dove halfway between the top of the dome and Christ’s halo and aligned with

a ray of white light which leads upwards towards a depiction of the Hand of God. “Consequently,

these three figures create an axial representation of the Trinity down the center of the mosaic,

with the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” (Hamblem, 2019). In this mosaic, Jesus is represented

with a beard- a notable change over the Byzantine period depictions of Christ. By the end of the

fourth century, Jesus had mostly transformed into a matured, bearded icon- “these later

representations [of Jesus]...came to look less like Socrates or Apollo and more like Greco-

Roman portrayals of majestic Jupiter” (Burkett, p. 500, 2011). Still, a bearded and beardless

Jesus continued to proliferate in either direction in Christian art; however, “their contradictory

coexistence demonstrates that a single, consistent portrait type was not deemed necessary at

the time. A polymorphous appearance may even have seemed more faithful, or less idolatrous,

in its implication that even Christ’s image cannot be entirely comprehended” (Burkett, p. 506).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Keeling 8

Eventually, the bearded Jesus became standard by the 6th Century and his features became

more consistent.

. Unfortunately, this paper did not have the length to further discuss proceeding

theological debates and division within the church, and the social and political forces that

especially influenced the 9th Century and the following “high Middle Ages”. Romanesque to

Gothic architecture trends accompanied new forms of Christian art, such as stained-glass

mosaics, “books of hours'', and adaptations in technique and media altogether emphasized

further theological shifts. Still, we now better understand how the iconography of the Deity

demonstrates changing theological understandings and how incredibly complex symbolism in

Christian art interacted with its followers.

Works Cited

Brooks, Sarah. (2009, August), Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium, “Met Museum”, Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/icon/hd_icon.htm

Burkett, D. R. (2011). The Blackwell Companion to Jesus. Chichester, West Sussex:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Eventually, the bearded Jesus became standard by the 6th Century and his features became

more consistent.

. Unfortunately, this paper did not have the length to further discuss proceeding

theological debates and division within the church, and the social and political forces that

especially influenced the 9th Century and the following “high Middle Ages”. Romanesque to

Gothic architecture trends accompanied new forms of Christian art, such as stained-glass

mosaics, “books of hours'', and adaptations in technique and media altogether emphasized

further theological shifts. Still, we now better understand how the iconography of the Deity

demonstrates changing theological understandings and how incredibly complex symbolism in

Christian art interacted with its followers.

Works Cited

Brooks, Sarah. (2009, August), Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium, “Met Museum”, Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/icon/hd_icon.htm

Burkett, D. R. (2011). The Blackwell Companion to Jesus. Chichester, West Sussex:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Keeling 9

Cornwell, J. (2009). Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art.

London, NY: Spck Publishing. Retrieved 2020, from

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Saints_Signs_and_Symbols/J2kX8f3iJfEC?hl=en

&gbpv=1

Demus, O. (1952) “The Classical System of Middle Byzantine Church Decoration”. MPublishing,

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Freeman, E., Ph.D. (2020). Mosaics and microcosm: The monasteries of Hosios Loukas, Nea

Moni, and Daphni. Retrieved 2020, from

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/

medieval-world/byzantine1/x4b0eb531:middle-byzantine/a/mosaics-and-microcosm-the-

monasteries-of-hosios-loukas-nea-moni-and-daphni

Hamblem, W., Ph.D. (2019). The Baptism of Christ, Hosios Loukas Mosaic. Retrieved

November 2020, from

https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/CivilizationHamblin/id/

1893/

“Holy Spirit, Iconography of”, New Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 2020, from

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs

-transcripts-and-maps/holy-spirit-iconography

Jones, S. P. (2018). Depictions of the Trinity in Early Christian Art Between 200AD and 400AD

(Unpublished master's thesis). Talbot School of Theology, Biola University.

Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/38113822/DEPICTIONS_OF_THE_

TRINITY_IN_EARLY_CHRISTIAN_ART_BETWEEN_200AD_AND_400AD

McMichael, A. L. (2020). Iconography of Christ. Retrieved November 21, 2020, from

http://projects.leadr.msu.edu/medievalart/about

Cornwell, J. (2009). Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art.

London, NY: Spck Publishing. Retrieved 2020, from

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Saints_Signs_and_Symbols/J2kX8f3iJfEC?hl=en

&gbpv=1

Demus, O. (1952) “The Classical System of Middle Byzantine Church Decoration”. MPublishing,

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Freeman, E., Ph.D. (2020). Mosaics and microcosm: The monasteries of Hosios Loukas, Nea

Moni, and Daphni. Retrieved 2020, from

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/

medieval-world/byzantine1/x4b0eb531:middle-byzantine/a/mosaics-and-microcosm-the-

monasteries-of-hosios-loukas-nea-moni-and-daphni

Hamblem, W., Ph.D. (2019). The Baptism of Christ, Hosios Loukas Mosaic. Retrieved

November 2020, from

https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/CivilizationHamblin/id/

1893/

“Holy Spirit, Iconography of”, New Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 2020, from

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs

-transcripts-and-maps/holy-spirit-iconography

Jones, S. P. (2018). Depictions of the Trinity in Early Christian Art Between 200AD and 400AD

(Unpublished master's thesis). Talbot School of Theology, Biola University.

Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/38113822/DEPICTIONS_OF_THE_

TRINITY_IN_EARLY_CHRISTIAN_ART_BETWEEN_200AD_AND_400AD

McMichael, A. L. (2020). Iconography of Christ. Retrieved November 21, 2020, from

http://projects.leadr.msu.edu/medievalart/about

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Keeling 10

Pizzinato, R. (2018). “Vision and Christomimesis in the Ruler Portrait of the Codex Aureus of St.

Emmeram”, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, V27. N2. Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/698840

“Robert Ludlum Library”, (2020, August 02). Revelations Of The Byzantine World. Retrieved

November 2020, from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache

%3Aq qqMeCOlPzcJ%3Aabletaxiskettering.co.uk

%2Frevelations_of_the_byzantine_world.pdf

Romagna, E. (2020) See the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, European Traveler. Retrieved

2020, from

https://www.european-traveler.com/italy/see-the-basilica-of-san-vitale-in-

ravenna/

Syndicus, E. (1962). Early Christian art. New York, NY: Hawthorn Books.

Pizzinato, R. (2018). “Vision and Christomimesis in the Ruler Portrait of the Codex Aureus of St.

Emmeram”, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, V27. N2. Retrieved

November 2020, from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/698840

“Robert Ludlum Library”, (2020, August 02). Revelations Of The Byzantine World. Retrieved

November 2020, from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache

%3Aq qqMeCOlPzcJ%3Aabletaxiskettering.co.uk

%2Frevelations_of_the_byzantine_world.pdf

Romagna, E. (2020) See the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, European Traveler. Retrieved

2020, from

https://www.european-traveler.com/italy/see-the-basilica-of-san-vitale-in-

ravenna/

Syndicus, E. (1962). Early Christian art. New York, NY: Hawthorn Books.

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.