Study on the Impact of Depression on Cigarette Smoking Frequency

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/29

|24

|6346

|437

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the impact of age, gender, and depression on cigarette smoking frequency using a large sample of the general public. The study analyzes the number of cigarettes smoked per day (cgtsday) in relation to age (agea), gender (gndr), and feelings of depression (fltdpr). Hypothesis testing reveals significant differences in smoking habits between genders, a weak positive correlation between age and smoking, and a notable impact of depression on smoking levels. A multiple regression model confirms the linear relationship between the control variables and smoking frequency. The findings highlight the importance of considering demographic and psychological factors in understanding and addressing smoking habits, particularly among women and individuals experiencing depression. Desklib provides access to a wealth of study resources, including past papers and solved assignments, to support students in their academic endeavors.

RUNNING HEAD: Impact of Depression on Cigarette Smoking Frequency – An Age and Gender-Based Study

Impact of Depression on Cigarette Smoking

Frequency – An Age and Gender-Based Study

1

Impact of Depression on Cigarette Smoking

Frequency – An Age and Gender-Based Study

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Abstract

The present investigation was performed by breaking down an extensive example of the

overall public, including a significant number of subjects who continued smoking. The result

variable was chosen as "cgtsday", which inferred the number of cigarettes smoked every day by

a person. The initial two demographical control factors were "agea", showing the age of the

examples and "gndr", meaning the sex of the example subjects. The third factor was the

sentiment of melancholy in a week ago and was meant by "fltdpr" in the overview. The reliance

on the result variable on the three control factors was tried in the theory testing process. The null

hypothesis was rejected against the substitute that there was a significant difference in cigarette

smoking speculation at 5% level, implying that guys smoked essentially more than the females.

There was a factually noteworthy connection demonstrating that cigarette smoking rate expanded

with increment in age. In any case, the affiliation was extremely frail and it is shown that for one

year of age increase cigarette smoking increments by 0.065. The cross-organization with the

sentiment of discouragement in later past or a week ago discovered that low smoking gathering

was measurably unique from different gatherings. From the t-test insights of the regression

model, the control factors were observed to be measurably noteworthy at 5% dimension of

noteworthiness. The control factors were found to significantly impact the cigarette smoking rate

in a linear manner.

2

The present investigation was performed by breaking down an extensive example of the

overall public, including a significant number of subjects who continued smoking. The result

variable was chosen as "cgtsday", which inferred the number of cigarettes smoked every day by

a person. The initial two demographical control factors were "agea", showing the age of the

examples and "gndr", meaning the sex of the example subjects. The third factor was the

sentiment of melancholy in a week ago and was meant by "fltdpr" in the overview. The reliance

on the result variable on the three control factors was tried in the theory testing process. The null

hypothesis was rejected against the substitute that there was a significant difference in cigarette

smoking speculation at 5% level, implying that guys smoked essentially more than the females.

There was a factually noteworthy connection demonstrating that cigarette smoking rate expanded

with increment in age. In any case, the affiliation was extremely frail and it is shown that for one

year of age increase cigarette smoking increments by 0.065. The cross-organization with the

sentiment of discouragement in later past or a week ago discovered that low smoking gathering

was measurably unique from different gatherings. From the t-test insights of the regression

model, the control factors were observed to be measurably noteworthy at 5% dimension of

noteworthiness. The control factors were found to significantly impact the cigarette smoking rate

in a linear manner.

2

Table of Contents

Abstract...................................................................................................................................................................... 2

Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................. 4

Rationale and Hypotheses................................................................................................................................... 5

Methodology............................................................................................................................................................. 6

Categorical Variable Generation for “cgtsday”....................................................................................... 7

One Variable Summary......................................................................................................................................... 7

Control variables................................................................................................................................................ 7

Outcome Variable............................................................................................................................................... 9

Inferential Analysis / Interpretation of Findings.................................................................................... 10

Hypothesis H01 Test: (T-test).................................................................................................................. 10

Hypothesis H02 Test: (Pearson’s Correlation).................................................................................. 11

Hypothesis H03 Test: (ANOVA)............................................................................................................... 12

Confirmatory test for Hypothesis H03: (Chi-Square Test for Categorical “cgtsday_cat”)13

Multiple Regression Model.............................................................................................................................. 14

Conclusion............................................................................................................................................................... 16

References............................................................................................................................................................... 18

Appendix (DO FILE OF STATA CODES)....................................................................................................... 20

3

Abstract...................................................................................................................................................................... 2

Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................. 4

Rationale and Hypotheses................................................................................................................................... 5

Methodology............................................................................................................................................................. 6

Categorical Variable Generation for “cgtsday”....................................................................................... 7

One Variable Summary......................................................................................................................................... 7

Control variables................................................................................................................................................ 7

Outcome Variable............................................................................................................................................... 9

Inferential Analysis / Interpretation of Findings.................................................................................... 10

Hypothesis H01 Test: (T-test).................................................................................................................. 10

Hypothesis H02 Test: (Pearson’s Correlation).................................................................................. 11

Hypothesis H03 Test: (ANOVA)............................................................................................................... 12

Confirmatory test for Hypothesis H03: (Chi-Square Test for Categorical “cgtsday_cat”)13

Multiple Regression Model.............................................................................................................................. 14

Conclusion............................................................................................................................................................... 16

References............................................................................................................................................................... 18

Appendix (DO FILE OF STATA CODES)....................................................................................................... 20

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Introduction

Cigarette smoking became commonplace from the very beginning of the 20th century.

Many men started smoking from the time of the First World War and many women got addicted

to the nicotine addiction from the era of Second World War. The general observation of time

trends has shown that more men than women smoke in their younger age, and although the

percentages have dropped globally, the decline is more pronounced in men than in women

(Fenech, & Bonassi, 2011, Ng et al., 2014). Cigarette smoking is the most important and decisive

factor that accelerates the age-related decline in lung diseases. The aim of this study was to

analyze the effects of age, gender and depression in the past on smoking habits (Leventhal &

Zvolensky, 2015). The main goal was to see whether smokers show a decrease in smoking

frequency as a result of increasing age and recently depressive mood (Boden, Fergusson &

Horwood, 2010). The study was conducted by analyzing a large sample of the general

population, including a significant number of subjects who were having increased smoking

habits. The prevalence of smoking and the burden of smoking-related diseases are of late shifting

to women. With a large number of young women who continue to smoke, there is a clear need to

learn more about ways to stop smoking and find ways to quit the menacing habit (Corona et al.,

2010). This article also examines smoking and gender behavior, with special attention to the

experience of aging.

One outcome and three control variables were identified from the survey data set

provided for this quantitative report. The outcome variable was selected as “cgtsday”, which

implied the number of cigarettes smoked per day by an individual. The first two

demographical control variables were “agea", indicating the age of the samples

(continuous) and “gndr”, denoting the gender (categorical and nominal) of the sample

subjects. The third control variable was the feeling of depression in last week and was

denoted by “fltdpr” in the survey (categorical and ordinal). The dependence of the outcome

variable on the three control variables was tested in the hypothesis testing process. A final

multiple regression model was constructed to assess the impact of the control variable on the

frequency of cigarette smoking.

4

Cigarette smoking became commonplace from the very beginning of the 20th century.

Many men started smoking from the time of the First World War and many women got addicted

to the nicotine addiction from the era of Second World War. The general observation of time

trends has shown that more men than women smoke in their younger age, and although the

percentages have dropped globally, the decline is more pronounced in men than in women

(Fenech, & Bonassi, 2011, Ng et al., 2014). Cigarette smoking is the most important and decisive

factor that accelerates the age-related decline in lung diseases. The aim of this study was to

analyze the effects of age, gender and depression in the past on smoking habits (Leventhal &

Zvolensky, 2015). The main goal was to see whether smokers show a decrease in smoking

frequency as a result of increasing age and recently depressive mood (Boden, Fergusson &

Horwood, 2010). The study was conducted by analyzing a large sample of the general

population, including a significant number of subjects who were having increased smoking

habits. The prevalence of smoking and the burden of smoking-related diseases are of late shifting

to women. With a large number of young women who continue to smoke, there is a clear need to

learn more about ways to stop smoking and find ways to quit the menacing habit (Corona et al.,

2010). This article also examines smoking and gender behavior, with special attention to the

experience of aging.

One outcome and three control variables were identified from the survey data set

provided for this quantitative report. The outcome variable was selected as “cgtsday”, which

implied the number of cigarettes smoked per day by an individual. The first two

demographical control variables were “agea", indicating the age of the samples

(continuous) and “gndr”, denoting the gender (categorical and nominal) of the sample

subjects. The third control variable was the feeling of depression in last week and was

denoted by “fltdpr” in the survey (categorical and ordinal). The dependence of the outcome

variable on the three control variables was tested in the hypothesis testing process. A final

multiple regression model was constructed to assess the impact of the control variable on the

frequency of cigarette smoking.

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Rationale and Hypotheses

In the tenure of entire life the amount of cigarettes smoked by people ultimately determines the

quality of air breathed. In women, the frequency of smoking determines the health condition,

especially given the biological intricacies of females. Some of the reviews have also shown the

status of smoker from the mid nineteenth century has decreased in the percentage, together with

an unstoppable increase in the number of ex-smokers (O'Loughlin, Karp, Koulis , Paradis,

DiFranza, 2009). Smoking in young women is particularly worrisome because it not only entails

a risk to their own long-term health, but also has a direct impact on the reproductive function and

health of their children (Strine et al., 2008). The prevalence of smoking in the most recent

meetings or in adult women exceeds that of men. This particular trend is now predominant in

European and Asian countries. While many longitudinal studies have studied the number of

people who have quit smoking to demonstrate that there is an effect in the loss of lung function

in heavy smokers compared to that of the light smokers. On the other hand, some studies had

already shown in the late nineteenth century that patients with adverse mental health had a high

proportion of addiction to cigarette smoking. Today, researchers are considering using both

cross-section and order information and taking advantage of recent depression problems (Thun,

DeLancey, Center, Jemal & Ward, 2009). The presentation of lung cancer and smoking was

followed by the constant expansion of data on the risks of smoking.

To study and analyze the impact of the control variables on smoking habit and frequency

of smoking, three hypotheses have been framed by the researcher. These hypotheses were

framed to answer the primary research question of this article: “Whether Age, Gender,

and recent Depression have any impact on frequency of cigarette smoking in daily life”.

Considering the type of the variables, the null hypotheses were structured against appropriate

alternate hypotheses. The three set of hypotheses were all tested at 5% level of significance for

their statistical implication.

5

In the tenure of entire life the amount of cigarettes smoked by people ultimately determines the

quality of air breathed. In women, the frequency of smoking determines the health condition,

especially given the biological intricacies of females. Some of the reviews have also shown the

status of smoker from the mid nineteenth century has decreased in the percentage, together with

an unstoppable increase in the number of ex-smokers (O'Loughlin, Karp, Koulis , Paradis,

DiFranza, 2009). Smoking in young women is particularly worrisome because it not only entails

a risk to their own long-term health, but also has a direct impact on the reproductive function and

health of their children (Strine et al., 2008). The prevalence of smoking in the most recent

meetings or in adult women exceeds that of men. This particular trend is now predominant in

European and Asian countries. While many longitudinal studies have studied the number of

people who have quit smoking to demonstrate that there is an effect in the loss of lung function

in heavy smokers compared to that of the light smokers. On the other hand, some studies had

already shown in the late nineteenth century that patients with adverse mental health had a high

proportion of addiction to cigarette smoking. Today, researchers are considering using both

cross-section and order information and taking advantage of recent depression problems (Thun,

DeLancey, Center, Jemal & Ward, 2009). The presentation of lung cancer and smoking was

followed by the constant expansion of data on the risks of smoking.

To study and analyze the impact of the control variables on smoking habit and frequency

of smoking, three hypotheses have been framed by the researcher. These hypotheses were

framed to answer the primary research question of this article: “Whether Age, Gender,

and recent Depression have any impact on frequency of cigarette smoking in daily life”.

Considering the type of the variables, the null hypotheses were structured against appropriate

alternate hypotheses. The three set of hypotheses were all tested at 5% level of significance for

their statistical implication.

5

H01: Male and females were equally inclined to smoking.

Against

HA1: There was a significant difference in smoking habits of men and women.

H02: Age had no correlation with the smoking frequency of sample subjects.

Against

HA2: There was a significant association of age of the subjects with their smoking frequency.

H03: Recent depression has no impact on the number of cigarettes smoked.

Against

HA3: Recent depression has a significant impact on the frequency of smoking.

Methodology

Four variables for the research purpose were extracted from the master data file to

evaluate the impact of age, gender and depression felt on cigarette addiction and smoking

frequency. STATA 15.0 version was utilized as the data analysis software platform for the

present research. The missing responses or responses where subjects did not want to answer were

taken care of in the STATA environment. The dependent "cgtsday" implied the number of

cigarette smoking by the subjects and responses from 2390 subjects was analyzed. Among 2390

responses 1837 missing values were re-coded, and assigned a character value to the missing

value for descriptive and inferential analyses. The missing values were then treated as non-

existent in STATA environment. Hence, valid 553 responses were analyzed in further

6

Against

HA1: There was a significant difference in smoking habits of men and women.

H02: Age had no correlation with the smoking frequency of sample subjects.

Against

HA2: There was a significant association of age of the subjects with their smoking frequency.

H03: Recent depression has no impact on the number of cigarettes smoked.

Against

HA3: Recent depression has a significant impact on the frequency of smoking.

Methodology

Four variables for the research purpose were extracted from the master data file to

evaluate the impact of age, gender and depression felt on cigarette addiction and smoking

frequency. STATA 15.0 version was utilized as the data analysis software platform for the

present research. The missing responses or responses where subjects did not want to answer were

taken care of in the STATA environment. The dependent "cgtsday" implied the number of

cigarette smoking by the subjects and responses from 2390 subjects was analyzed. Among 2390

responses 1837 missing values were re-coded, and assigned a character value to the missing

value for descriptive and inferential analyses. The missing values were then treated as non-

existent in STATA environment. Hence, valid 553 responses were analyzed in further

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

investigation. To test the gender difference effect on smoking cigarettes, an independent t-test

was used. The relation of smoking frequency with age of the subjects was tested by a Pearson’s

correlation coefficient.

Categorical Variable Generation for “cgtsday”

A new categorical variable “cgtsday_cat” was generated, where three categories of

smokers were created based on the frequency of smoking. Subjects smoking between 0 - 15

cigarettes was labeled as “Low Smoking”, smokers ranged between 16 to 30 cigarettes were

named as “Medium Smoking”, and smoking frequency between 31 to 45 cigarettes a day was

labeled as "High Smoking". A chi-square test was used to find the categorical difference of

smoking frequency on past depression levels. Finally, a multiple regression model was

constructed for testing the linear relationship between the outcome and control variables.

One Variable Summary

Control variables

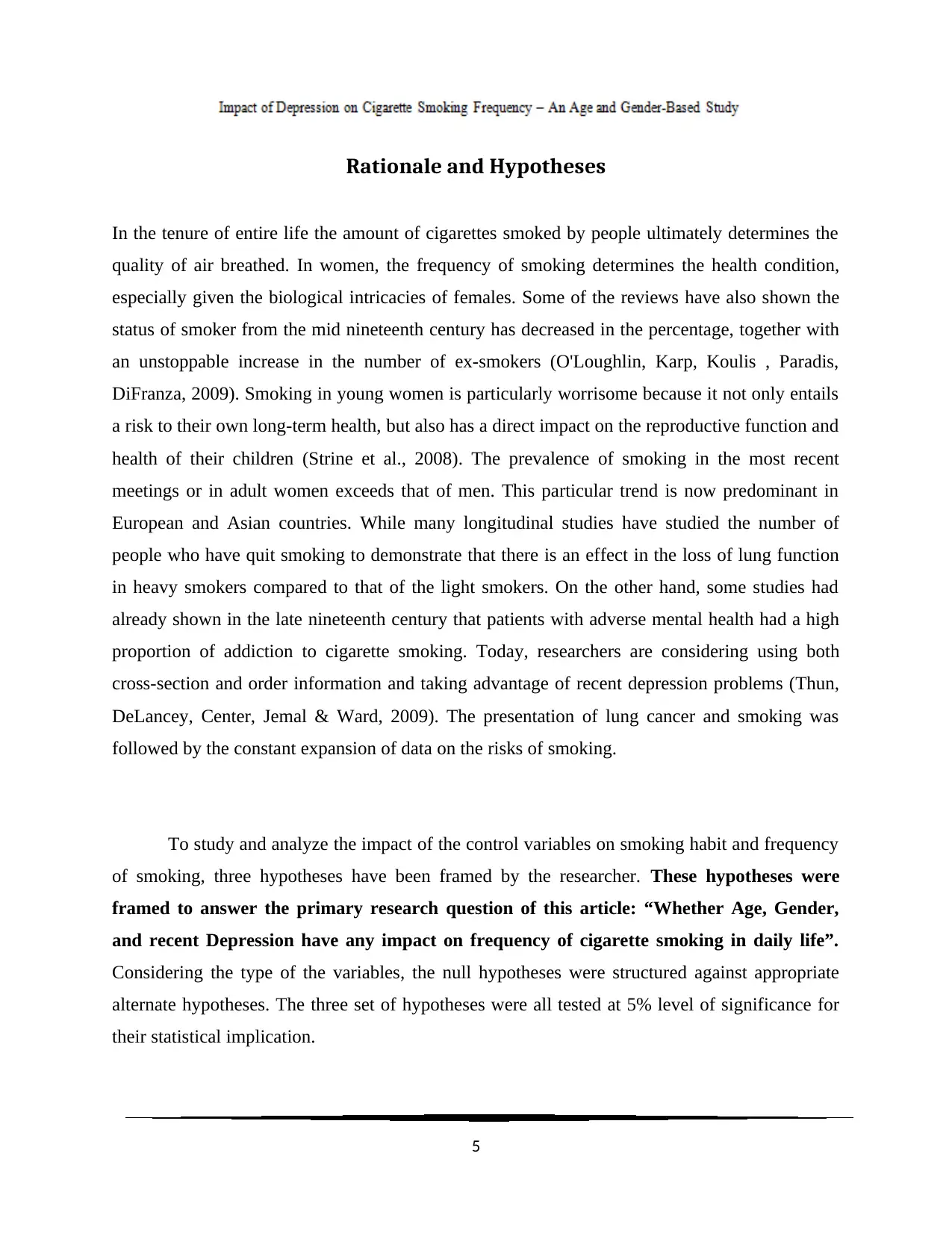

Gender analysis from figure 1 it can be noted that there was 1102 male (P = 46.11%) and

1288 female subjects (P = 53.89%) in the sample. The dominant presence of female subjects as

smokers in the sample indicated that females were addicted to smoking instead of various

biological hazards caused due to smoking (Dechanet et al., 2010).

46.11

53.89

0 20 40 60

Percent

Gender

Gender Distribution

Figure 1: Gender Distribution of the Subjects in the Sample

7

was used. The relation of smoking frequency with age of the subjects was tested by a Pearson’s

correlation coefficient.

Categorical Variable Generation for “cgtsday”

A new categorical variable “cgtsday_cat” was generated, where three categories of

smokers were created based on the frequency of smoking. Subjects smoking between 0 - 15

cigarettes was labeled as “Low Smoking”, smokers ranged between 16 to 30 cigarettes were

named as “Medium Smoking”, and smoking frequency between 31 to 45 cigarettes a day was

labeled as "High Smoking". A chi-square test was used to find the categorical difference of

smoking frequency on past depression levels. Finally, a multiple regression model was

constructed for testing the linear relationship between the outcome and control variables.

One Variable Summary

Control variables

Gender analysis from figure 1 it can be noted that there was 1102 male (P = 46.11%) and

1288 female subjects (P = 53.89%) in the sample. The dominant presence of female subjects as

smokers in the sample indicated that females were addicted to smoking instead of various

biological hazards caused due to smoking (Dechanet et al., 2010).

46.11

53.89

0 20 40 60

Percent

Gender

Gender Distribution

Figure 1: Gender Distribution of the Subjects in the Sample

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

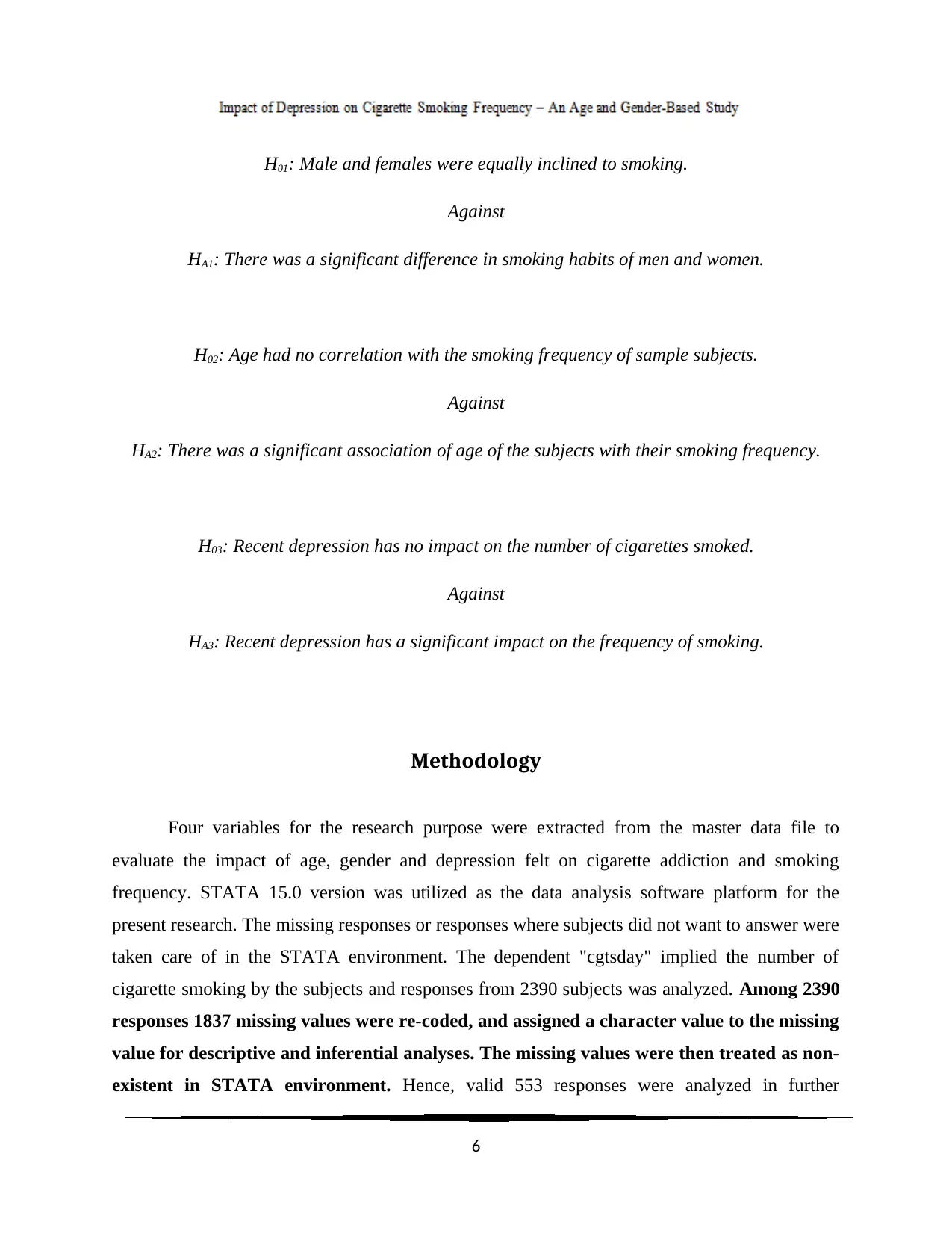

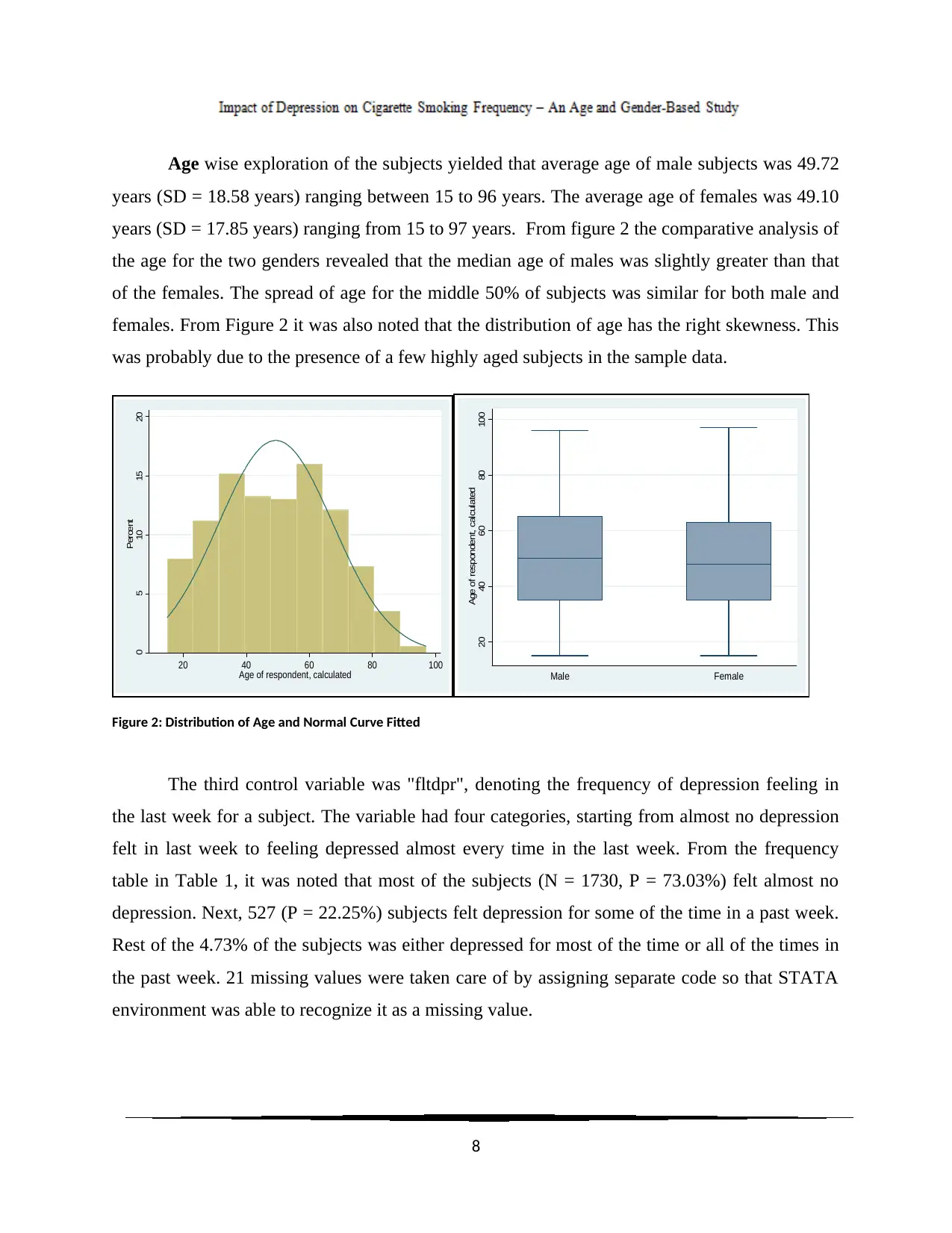

Age wise exploration of the subjects yielded that average age of male subjects was 49.72

years (SD = 18.58 years) ranging between 15 to 96 years. The average age of females was 49.10

years (SD = 17.85 years) ranging from 15 to 97 years. From figure 2 the comparative analysis of

the age for the two genders revealed that the median age of males was slightly greater than that

of the females. The spread of age for the middle 50% of subjects was similar for both male and

females. From Figure 2 it was also noted that the distribution of age has the right skewness. This

was probably due to the presence of a few highly aged subjects in the sample data.

0 5 10 15 20

Percent

20 40 60 80 100

Age of respondent, calculated

20 40 60 80 100

Age of respondent, calculated

Male Female

Figure 2: Distribution of Age and Normal Curve Fitted

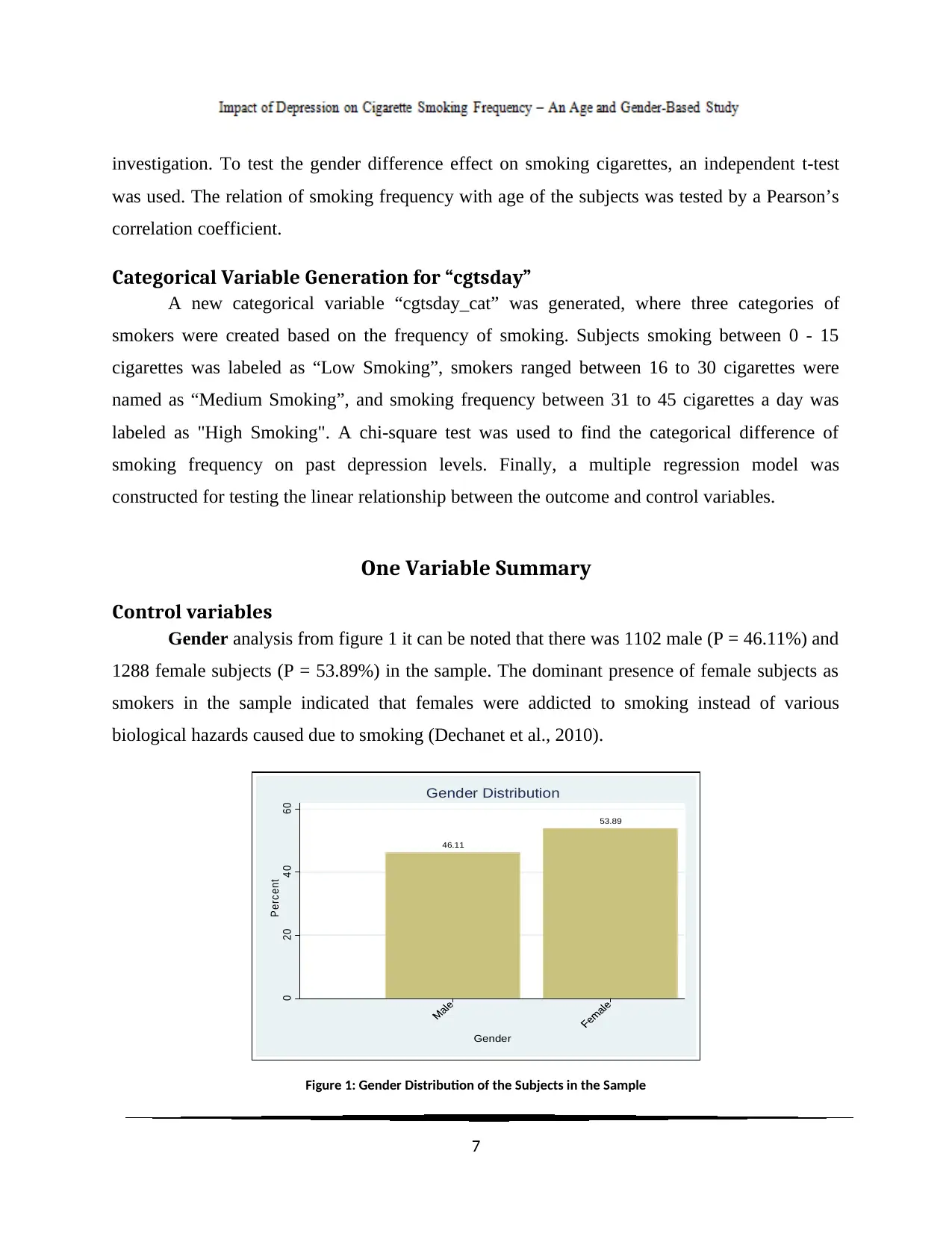

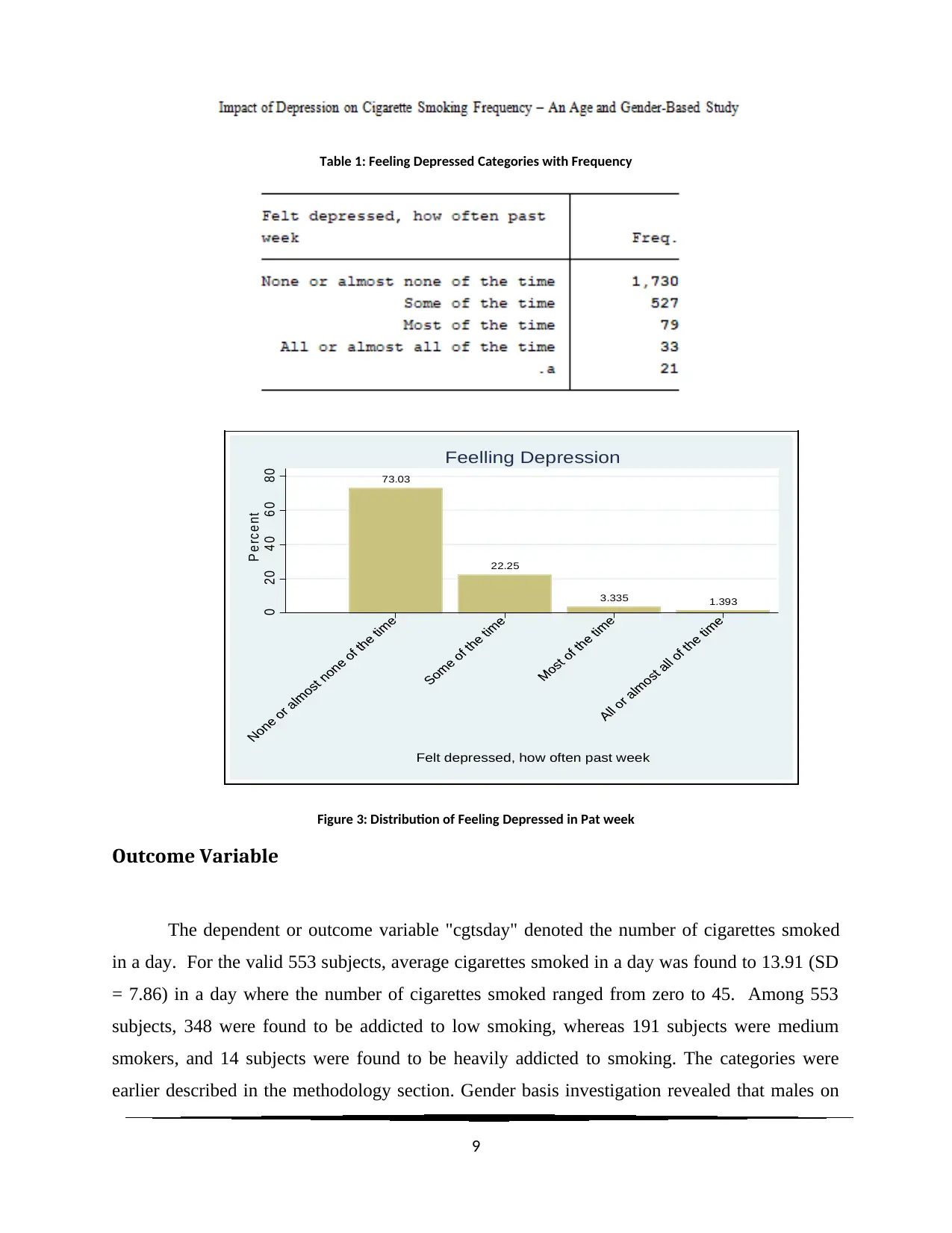

The third control variable was "fltdpr", denoting the frequency of depression feeling in

the last week for a subject. The variable had four categories, starting from almost no depression

felt in last week to feeling depressed almost every time in the last week. From the frequency

table in Table 1, it was noted that most of the subjects (N = 1730, P = 73.03%) felt almost no

depression. Next, 527 (P = 22.25%) subjects felt depression for some of the time in a past week.

Rest of the 4.73% of the subjects was either depressed for most of the time or all of the times in

the past week. 21 missing values were taken care of by assigning separate code so that STATA

environment was able to recognize it as a missing value.

8

years (SD = 18.58 years) ranging between 15 to 96 years. The average age of females was 49.10

years (SD = 17.85 years) ranging from 15 to 97 years. From figure 2 the comparative analysis of

the age for the two genders revealed that the median age of males was slightly greater than that

of the females. The spread of age for the middle 50% of subjects was similar for both male and

females. From Figure 2 it was also noted that the distribution of age has the right skewness. This

was probably due to the presence of a few highly aged subjects in the sample data.

0 5 10 15 20

Percent

20 40 60 80 100

Age of respondent, calculated

20 40 60 80 100

Age of respondent, calculated

Male Female

Figure 2: Distribution of Age and Normal Curve Fitted

The third control variable was "fltdpr", denoting the frequency of depression feeling in

the last week for a subject. The variable had four categories, starting from almost no depression

felt in last week to feeling depressed almost every time in the last week. From the frequency

table in Table 1, it was noted that most of the subjects (N = 1730, P = 73.03%) felt almost no

depression. Next, 527 (P = 22.25%) subjects felt depression for some of the time in a past week.

Rest of the 4.73% of the subjects was either depressed for most of the time or all of the times in

the past week. 21 missing values were taken care of by assigning separate code so that STATA

environment was able to recognize it as a missing value.

8

Table 1: Feeling Depressed Categories with Frequency

73.03

22.25

3.335 1.393

0 20 40 60 80

P e rce nt

Felt depressed, how often past week

Feelling Depression

Figure 3: Distribution of Feeling Depressed in Pat week

Outcome Variable

The dependent or outcome variable "cgtsday" denoted the number of cigarettes smoked

in a day. For the valid 553 subjects, average cigarettes smoked in a day was found to 13.91 (SD

= 7.86) in a day where the number of cigarettes smoked ranged from zero to 45. Among 553

subjects, 348 were found to be addicted to low smoking, whereas 191 subjects were medium

smokers, and 14 subjects were found to be heavily addicted to smoking. The categories were

earlier described in the methodology section. Gender basis investigation revealed that males on

9

73.03

22.25

3.335 1.393

0 20 40 60 80

P e rce nt

Felt depressed, how often past week

Feelling Depression

Figure 3: Distribution of Feeling Depressed in Pat week

Outcome Variable

The dependent or outcome variable "cgtsday" denoted the number of cigarettes smoked

in a day. For the valid 553 subjects, average cigarettes smoked in a day was found to 13.91 (SD

= 7.86) in a day where the number of cigarettes smoked ranged from zero to 45. Among 553

subjects, 348 were found to be addicted to low smoking, whereas 191 subjects were medium

smokers, and 14 subjects were found to be heavily addicted to smoking. The categories were

earlier described in the methodology section. Gender basis investigation revealed that males on

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

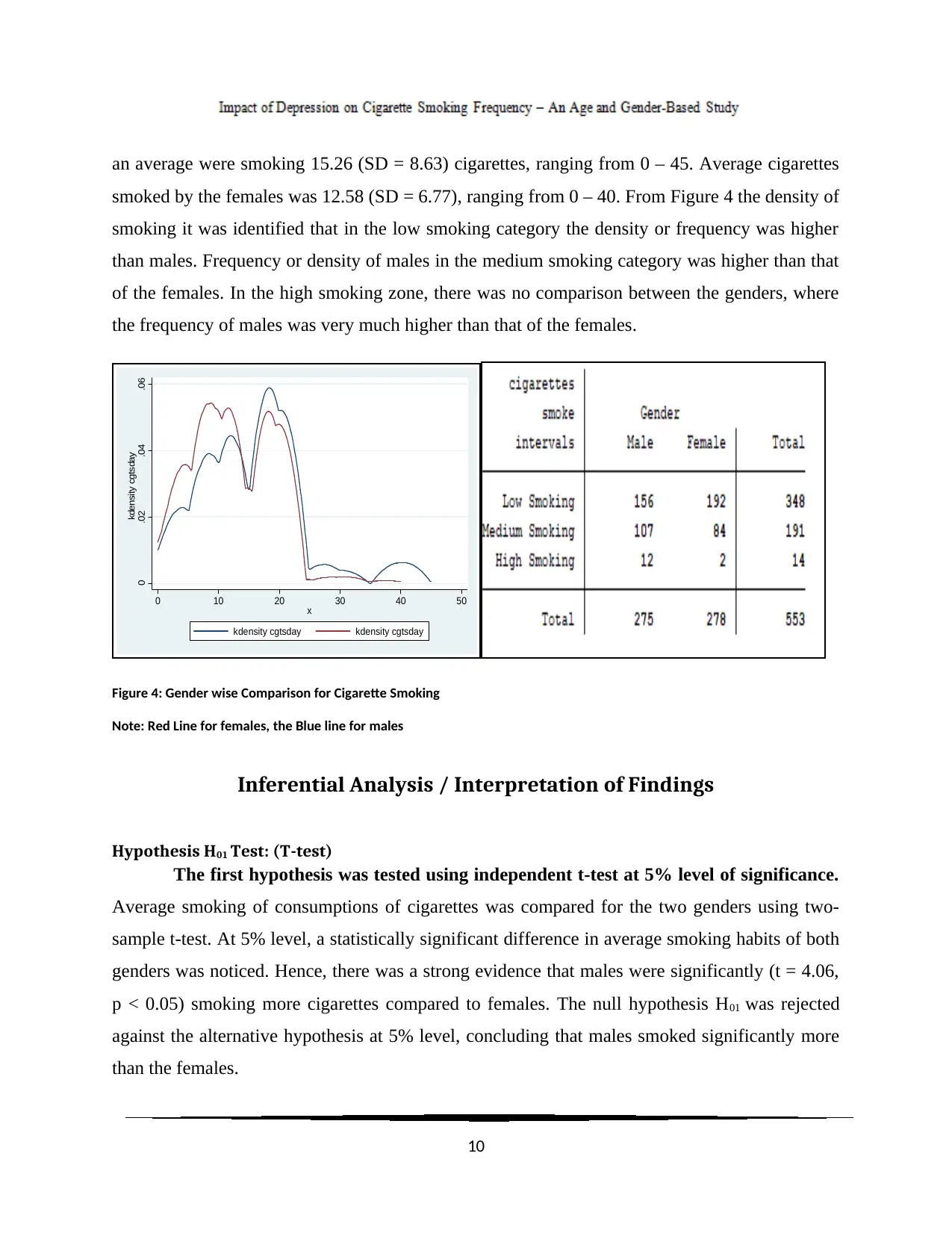

an average were smoking 15.26 (SD = 8.63) cigarettes, ranging from 0 – 45. Average cigarettes

smoked by the females was 12.58 (SD = 6.77), ranging from 0 – 40. From Figure 4 the density of

smoking it was identified that in the low smoking category the density or frequency was higher

than males. Frequency or density of males in the medium smoking category was higher than that

of the females. In the high smoking zone, there was no comparison between the genders, where

the frequency of males was very much higher than that of the females.

0 .02 .04 .06

kdensity cgtsday

0 10 20 30 40 50

x

kdensity cgtsday kdensity cgtsday

Figure 4: Gender wise Comparison for Cigarette Smoking

Note: Red Line for females, the Blue line for males

Inferential Analysis / Interpretation of Findings

Hypothesis H01 Test: (T-test)

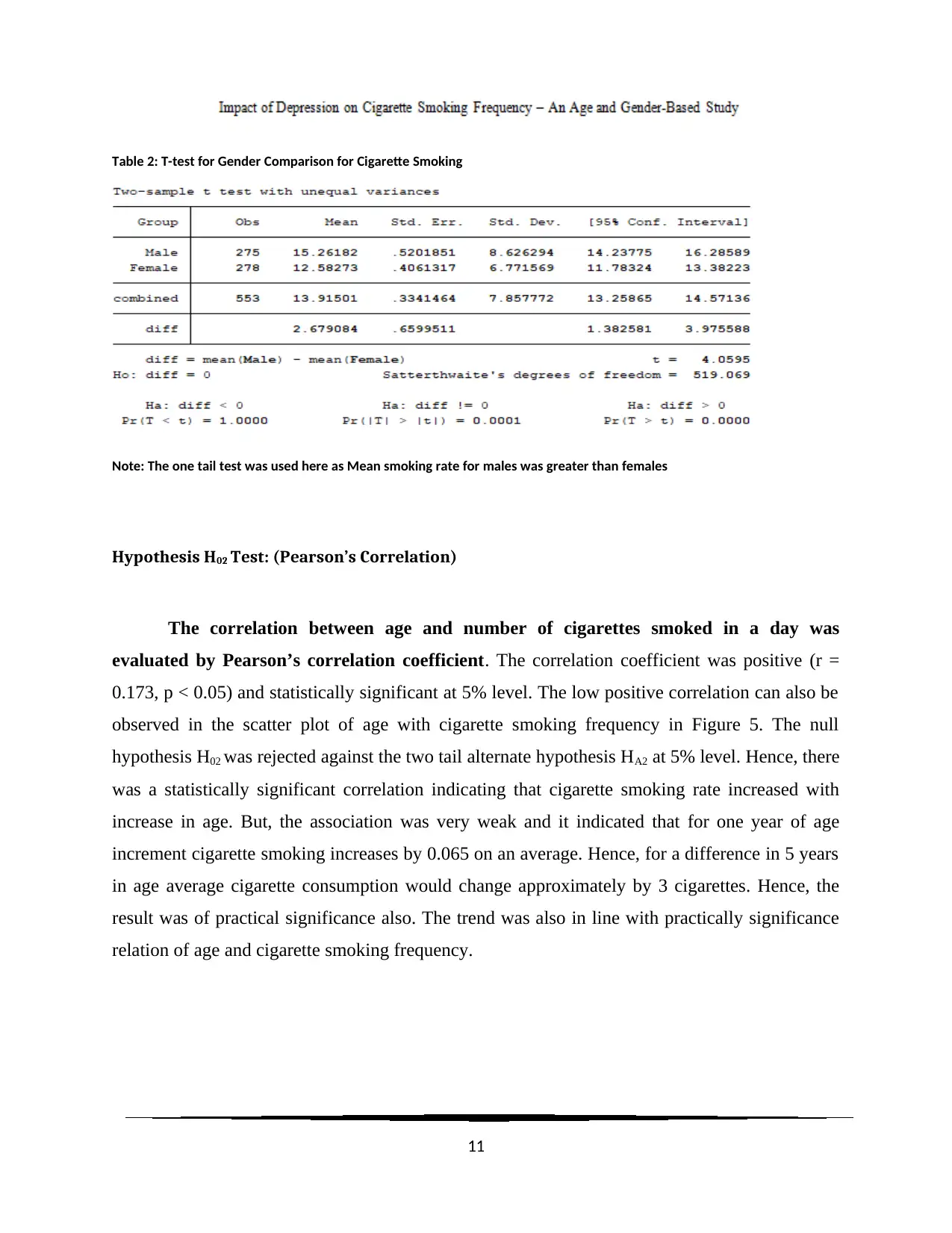

The first hypothesis was tested using independent t-test at 5% level of significance.

Average smoking of consumptions of cigarettes was compared for the two genders using two-

sample t-test. At 5% level, a statistically significant difference in average smoking habits of both

genders was noticed. Hence, there was a strong evidence that males were significantly (t = 4.06,

p < 0.05) smoking more cigarettes compared to females. The null hypothesis H01 was rejected

against the alternative hypothesis at 5% level, concluding that males smoked significantly more

than the females.

10

smoked by the females was 12.58 (SD = 6.77), ranging from 0 – 40. From Figure 4 the density of

smoking it was identified that in the low smoking category the density or frequency was higher

than males. Frequency or density of males in the medium smoking category was higher than that

of the females. In the high smoking zone, there was no comparison between the genders, where

the frequency of males was very much higher than that of the females.

0 .02 .04 .06

kdensity cgtsday

0 10 20 30 40 50

x

kdensity cgtsday kdensity cgtsday

Figure 4: Gender wise Comparison for Cigarette Smoking

Note: Red Line for females, the Blue line for males

Inferential Analysis / Interpretation of Findings

Hypothesis H01 Test: (T-test)

The first hypothesis was tested using independent t-test at 5% level of significance.

Average smoking of consumptions of cigarettes was compared for the two genders using two-

sample t-test. At 5% level, a statistically significant difference in average smoking habits of both

genders was noticed. Hence, there was a strong evidence that males were significantly (t = 4.06,

p < 0.05) smoking more cigarettes compared to females. The null hypothesis H01 was rejected

against the alternative hypothesis at 5% level, concluding that males smoked significantly more

than the females.

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 2: T-test for Gender Comparison for Cigarette Smoking

Note: The one tail test was used here as Mean smoking rate for males was greater than females

Hypothesis H02 Test: (Pearson’s Correlation)

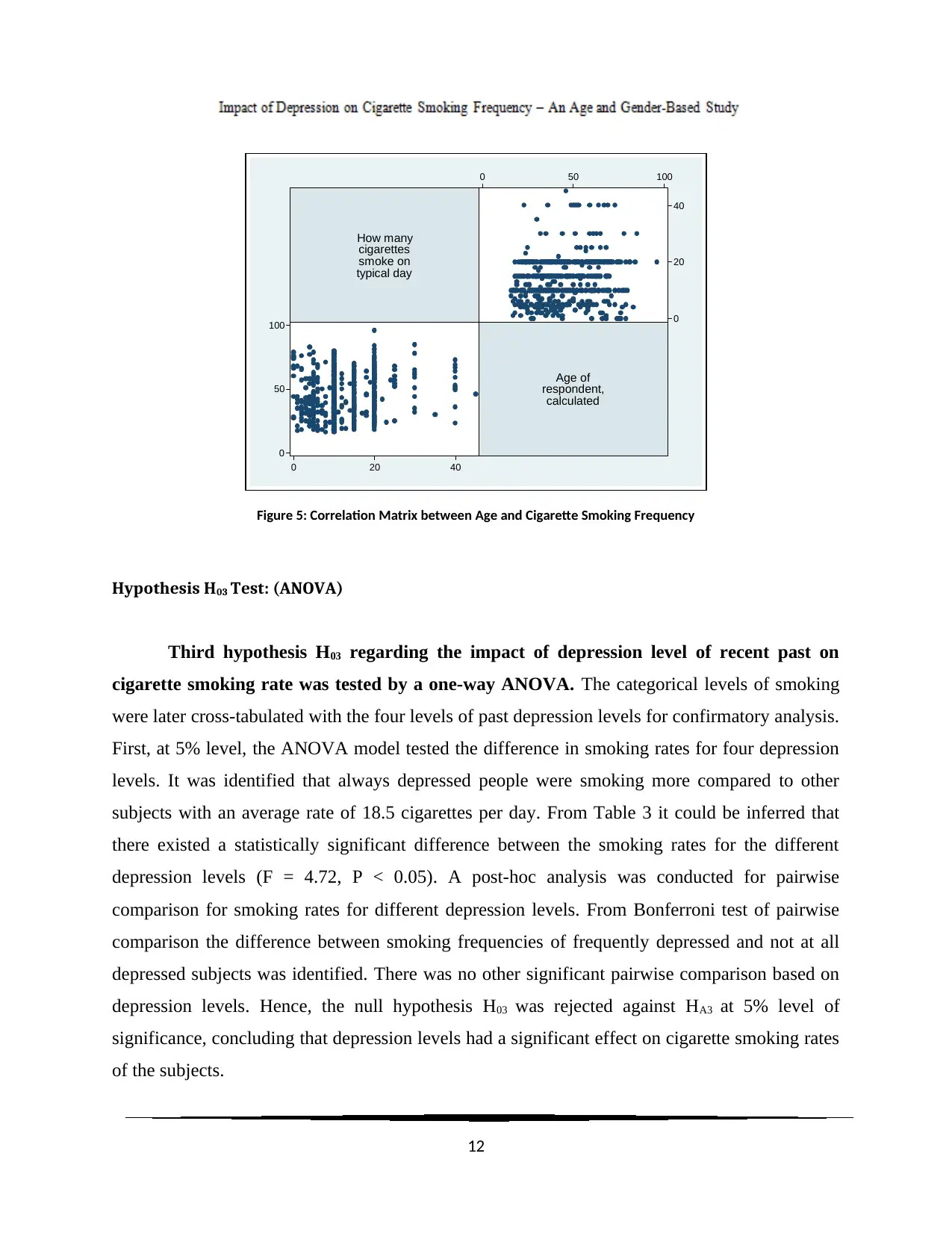

The correlation between age and number of cigarettes smoked in a day was

evaluated by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient was positive (r =

0.173, p < 0.05) and statistically significant at 5% level. The low positive correlation can also be

observed in the scatter plot of age with cigarette smoking frequency in Figure 5. The null

hypothesis H02 was rejected against the two tail alternate hypothesis HA2 at 5% level. Hence, there

was a statistically significant correlation indicating that cigarette smoking rate increased with

increase in age. But, the association was very weak and it indicated that for one year of age

increment cigarette smoking increases by 0.065 on an average. Hence, for a difference in 5 years

in age average cigarette consumption would change approximately by 3 cigarettes. Hence, the

result was of practical significance also. The trend was also in line with practically significance

relation of age and cigarette smoking frequency.

11

Note: The one tail test was used here as Mean smoking rate for males was greater than females

Hypothesis H02 Test: (Pearson’s Correlation)

The correlation between age and number of cigarettes smoked in a day was

evaluated by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient was positive (r =

0.173, p < 0.05) and statistically significant at 5% level. The low positive correlation can also be

observed in the scatter plot of age with cigarette smoking frequency in Figure 5. The null

hypothesis H02 was rejected against the two tail alternate hypothesis HA2 at 5% level. Hence, there

was a statistically significant correlation indicating that cigarette smoking rate increased with

increase in age. But, the association was very weak and it indicated that for one year of age

increment cigarette smoking increases by 0.065 on an average. Hence, for a difference in 5 years

in age average cigarette consumption would change approximately by 3 cigarettes. Hence, the

result was of practical significance also. The trend was also in line with practically significance

relation of age and cigarette smoking frequency.

11

How many

cigarettes

smoke on

typical day

Age of

respondent,

calculated

0

20

40

0 20 40

0

50

100

0 50 100

Figure 5: Correlation Matrix between Age and Cigarette Smoking Frequency

Hypothesis H03 Test: (ANOVA)

Third hypothesis H03 regarding the impact of depression level of recent past on

cigarette smoking rate was tested by a one-way ANOVA. The categorical levels of smoking

were later cross-tabulated with the four levels of past depression levels for confirmatory analysis.

First, at 5% level, the ANOVA model tested the difference in smoking rates for four depression

levels. It was identified that always depressed people were smoking more compared to other

subjects with an average rate of 18.5 cigarettes per day. From Table 3 it could be inferred that

there existed a statistically significant difference between the smoking rates for the different

depression levels (F = 4.72, P < 0.05). A post-hoc analysis was conducted for pairwise

comparison for smoking rates for different depression levels. From Bonferroni test of pairwise

comparison the difference between smoking frequencies of frequently depressed and not at all

depressed subjects was identified. There was no other significant pairwise comparison based on

depression levels. Hence, the null hypothesis H03 was rejected against HA3 at 5% level of

significance, concluding that depression levels had a significant effect on cigarette smoking rates

of the subjects.

12

cigarettes

smoke on

typical day

Age of

respondent,

calculated

0

20

40

0 20 40

0

50

100

0 50 100

Figure 5: Correlation Matrix between Age and Cigarette Smoking Frequency

Hypothesis H03 Test: (ANOVA)

Third hypothesis H03 regarding the impact of depression level of recent past on

cigarette smoking rate was tested by a one-way ANOVA. The categorical levels of smoking

were later cross-tabulated with the four levels of past depression levels for confirmatory analysis.

First, at 5% level, the ANOVA model tested the difference in smoking rates for four depression

levels. It was identified that always depressed people were smoking more compared to other

subjects with an average rate of 18.5 cigarettes per day. From Table 3 it could be inferred that

there existed a statistically significant difference between the smoking rates for the different

depression levels (F = 4.72, P < 0.05). A post-hoc analysis was conducted for pairwise

comparison for smoking rates for different depression levels. From Bonferroni test of pairwise

comparison the difference between smoking frequencies of frequently depressed and not at all

depressed subjects was identified. There was no other significant pairwise comparison based on

depression levels. Hence, the null hypothesis H03 was rejected against HA3 at 5% level of

significance, concluding that depression levels had a significant effect on cigarette smoking rates

of the subjects.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.