Epidemiology Assignment: Antenatal Depression and Gestational Diabetes

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/17

|15

|3948

|40

Report

AI Summary

This assignment presents a critical appraisal of three articles investigating the association between antenatal depression and gestational diabetes (GDM). The methodology involved a comprehensive search of MEDLINE and CINAHL using relevant search terms, followed by the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria to refine the search results. The articles selected for appraisal included a systematic review, a cross-sectional study, and an epidemiological study. The appraisal employed the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) to assess the value, trustworthiness, and relevance of the findings. The systematic review by Byrn and Penckofer (2013) found a link between GDM and increased depression scores. Byrn and Penckofer (2015)'s cross-sectional study revealed that women with GDM had a higher likelihood of antenatal depression, with perceived stress and trait anxiety as predictive factors. Laurent and Ramos (2017)'s epidemiological study also indicated a strong association between GDM and depression. The discussion section critically evaluates the strengths and limitations of each study design, including the use of appropriate methods, potential biases, and the generalizability of the findings. Strategies to improve the reliability of the systematic review and the limitations of the sampling methods are discussed, along with implications for clinical practice and future research. The findings of all three studies support a correlation between GDM and antenatal depression. The report concludes with recommendations for healthcare providers to screen for depression in pregnant women with GDM and suggests future research directions.

Running head: NURSING

PUBH6005: Epidemiology

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author Note

PUBH6005: Epidemiology

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author Note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1NURSING

Introduction- According to Jarde et al. (2016) also referred to as prenatal depression,

antenatal depression refers to a type of clinical depression that creates an impact on a female,

at the time of pregnancy. This condition is generally considered as a precursor to postpartum

depression, when left untreated. Time and again it has been found any type of prenatal stress

sensed by the mother creates significant negative consequences on numerous facets of foetal

development, which in turn result in harm to the child and mother (Rice, Langley, Woodford,

Smith & Thapar, 2018). Such antenatal depression is found to occur due to several aspects

that are related to the personal life of the mother, socioeconomic condition, family issues and

relationship status (Castro, Glover, Ehlert & O'Connor, 2017). Following birth, an infant who

is born from a stressed or depressed mother is usually subjected to the repercussions, such

that the child becomes less active, and also experiences emotive distress. In contrast,

gestational diabetes (GDM) refers to the condition when a female demonstrated elevated

levels of blood glucose, usually during pregnancy (Koivusalo et al., 2016). This often

increases the risks of depression, besides augmenting susceptibility to pre-eclampsia and

often the child require caesarean section during delivery. Research evidences have also

established strong correlation between postpartum depression and antenatal depression

(Doyle, 2017). It has often been established by researchers that pregnant women diagnosed

with gestational diabetes, when subjected to a range of lifestyle interventions demonstrated

reduced signs and symptoms of postpartum depression (Lim et al., 2019). This assignment

will therefore contain a critical appraisal of three articles that determine the association

between antenatal depression and gestational diabetes.

Methodology- The extraction of articles was based on formulation of a causal research

question that generally helps in determining whether one or more variables affect or cause

one or more outcomes. The research question used for this assignment is given below:

What is the association between GDM and antenatal depression?

Introduction- According to Jarde et al. (2016) also referred to as prenatal depression,

antenatal depression refers to a type of clinical depression that creates an impact on a female,

at the time of pregnancy. This condition is generally considered as a precursor to postpartum

depression, when left untreated. Time and again it has been found any type of prenatal stress

sensed by the mother creates significant negative consequences on numerous facets of foetal

development, which in turn result in harm to the child and mother (Rice, Langley, Woodford,

Smith & Thapar, 2018). Such antenatal depression is found to occur due to several aspects

that are related to the personal life of the mother, socioeconomic condition, family issues and

relationship status (Castro, Glover, Ehlert & O'Connor, 2017). Following birth, an infant who

is born from a stressed or depressed mother is usually subjected to the repercussions, such

that the child becomes less active, and also experiences emotive distress. In contrast,

gestational diabetes (GDM) refers to the condition when a female demonstrated elevated

levels of blood glucose, usually during pregnancy (Koivusalo et al., 2016). This often

increases the risks of depression, besides augmenting susceptibility to pre-eclampsia and

often the child require caesarean section during delivery. Research evidences have also

established strong correlation between postpartum depression and antenatal depression

(Doyle, 2017). It has often been established by researchers that pregnant women diagnosed

with gestational diabetes, when subjected to a range of lifestyle interventions demonstrated

reduced signs and symptoms of postpartum depression (Lim et al., 2019). This assignment

will therefore contain a critical appraisal of three articles that determine the association

between antenatal depression and gestational diabetes.

Methodology- The extraction of articles was based on formulation of a causal research

question that generally helps in determining whether one or more variables affect or cause

one or more outcomes. The research question used for this assignment is given below:

What is the association between GDM and antenatal depression?

2NURSING

Two electronic databases namely, MEDLINE and CINAHL were comprehensively

searched for recovering scholarly evidences with the use of definite search terms that were

relevant to the aforementioned question. The terms that were given as an input in the

databases were namely, “gestational diabetes mellitus”, “gdm”, “diabetes in pregnancy”,

“gestational diabetes”, “association”, “relationship”, “correlation”, “antenatal depression”,

“perinatal depression”, and “depression in pregnancy”. A manual search was also conducted

in the bibliography of the obtained articles to retrieve additional evidences that were pertinent

to the research question. The search terms were combined using boolean operators ‘AND’

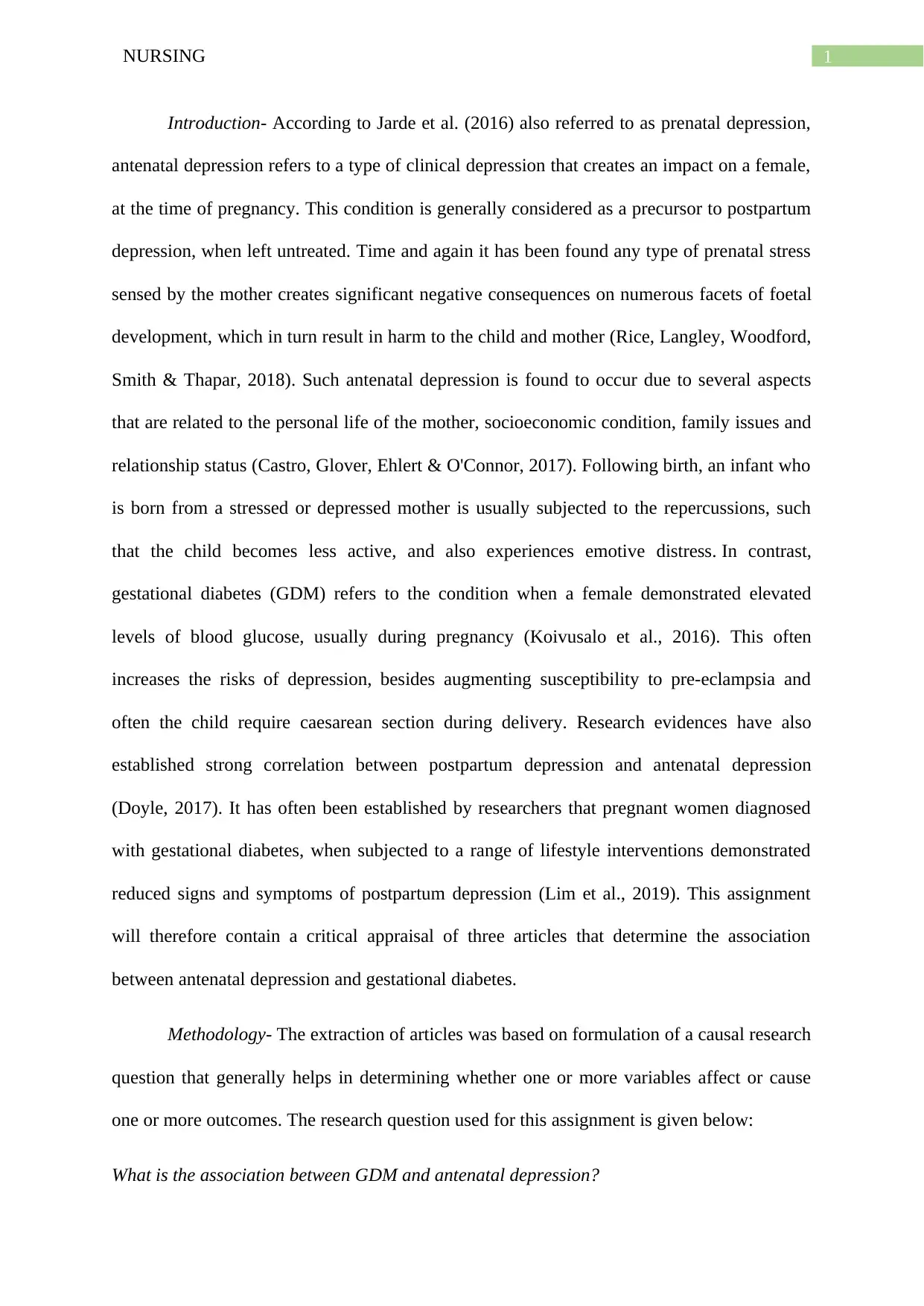

and ‘OR’ (McGowan et al. 2016). A definite inclusion and exclusion criteria was also

developed for refining the search results. The table given below contains the eligibility

criteria developed for article extraction:

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria

Articles published in English Articles published in foreign languages

Articles published on or after 2013 Articles published prior to 2013

Based on link between GDM and antenatal

depression

Articles that focus on other metabolic

syndrome

Primary and secondary research articles Clinical guideline, case study

Table 1- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following extraction of three articles that were considered most relevant to the

research question, a critical appraisal was performed for systematically and carefully

examining the outcome of the selected evidences. This helped in judging the value,

trustworthiness, and relevance of the findings in the particular context. The Critical Appraisal

Skills Programme (CASP) was used for the critical evaluation (CASP UK, 2018).

Two electronic databases namely, MEDLINE and CINAHL were comprehensively

searched for recovering scholarly evidences with the use of definite search terms that were

relevant to the aforementioned question. The terms that were given as an input in the

databases were namely, “gestational diabetes mellitus”, “gdm”, “diabetes in pregnancy”,

“gestational diabetes”, “association”, “relationship”, “correlation”, “antenatal depression”,

“perinatal depression”, and “depression in pregnancy”. A manual search was also conducted

in the bibliography of the obtained articles to retrieve additional evidences that were pertinent

to the research question. The search terms were combined using boolean operators ‘AND’

and ‘OR’ (McGowan et al. 2016). A definite inclusion and exclusion criteria was also

developed for refining the search results. The table given below contains the eligibility

criteria developed for article extraction:

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria

Articles published in English Articles published in foreign languages

Articles published on or after 2013 Articles published prior to 2013

Based on link between GDM and antenatal

depression

Articles that focus on other metabolic

syndrome

Primary and secondary research articles Clinical guideline, case study

Table 1- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following extraction of three articles that were considered most relevant to the

research question, a critical appraisal was performed for systematically and carefully

examining the outcome of the selected evidences. This helped in judging the value,

trustworthiness, and relevance of the findings in the particular context. The Critical Appraisal

Skills Programme (CASP) was used for the critical evaluation (CASP UK, 2018).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3NURSING

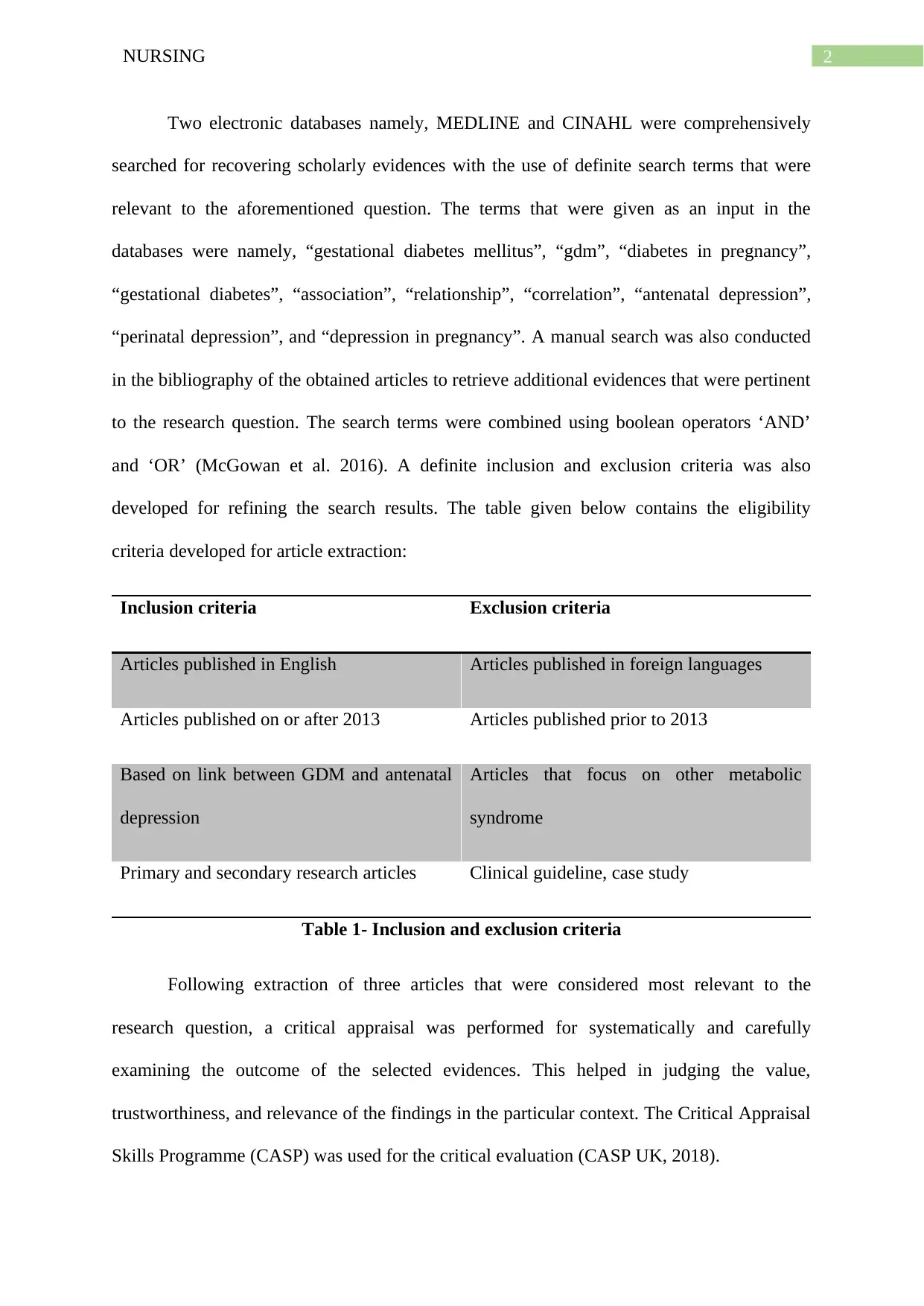

Results- The tables provided below contains answers to individual checklists for each

type of study that had been selected:

Byrn and Penckofer (2013)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes There is lack of evidence for the correlation between

antenatal depression and gestational diabetes.

2 Yes The researchers explored the causal association by collating

and summarising six research evidences that addressed the

phenomenon under investigation

3 Yes Till 2013, there were only six articles that had addressed

link between the two variables

4 Can’t tell There was lack of information on critical analysis of the

included articles

5 Yes Clear display and collation of the six articles suggested that

pregnant females with antenatal depression and GDM are at

an increased risk for negative health outcomes (Skelly,

Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

6 There exist a link between females with GDM and greater

depression scores paralleled to females without diabetes

throughout pregnancy

7 95% CI was reported by two studies included in the review

thus suggesting 95% certainty about obtaining similar

association in the target population

8 Yes There is not much difference in the local setting for

Results- The tables provided below contains answers to individual checklists for each

type of study that had been selected:

Byrn and Penckofer (2013)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes There is lack of evidence for the correlation between

antenatal depression and gestational diabetes.

2 Yes The researchers explored the causal association by collating

and summarising six research evidences that addressed the

phenomenon under investigation

3 Yes Till 2013, there were only six articles that had addressed

link between the two variables

4 Can’t tell There was lack of information on critical analysis of the

included articles

5 Yes Clear display and collation of the six articles suggested that

pregnant females with antenatal depression and GDM are at

an increased risk for negative health outcomes (Skelly,

Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

6 There exist a link between females with GDM and greater

depression scores paralleled to females without diabetes

throughout pregnancy

7 95% CI was reported by two studies included in the review

thus suggesting 95% certainty about obtaining similar

association in the target population

8 Yes There is not much difference in the local setting for

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4NURSING

pregnant women diagnosed with gestational diabetes

9 Yes Prevalence of depression, as evidenced by using depression

scale was measured in all studies included in the review

10 Yes There are no potential risks associated with early screening

of antenatal depression among GDM affected pregnant

women

Table 2- CASP checklist for systematic review

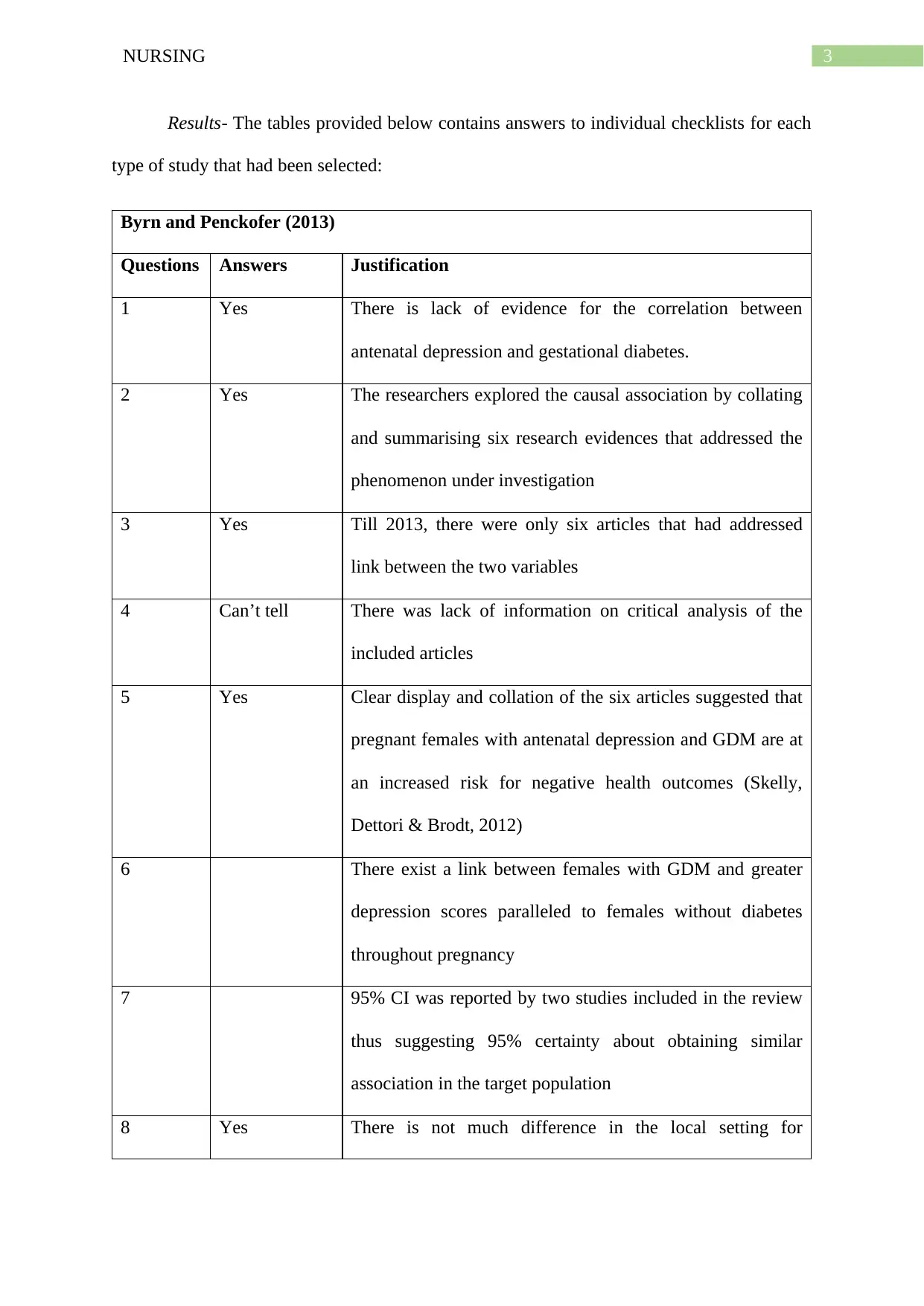

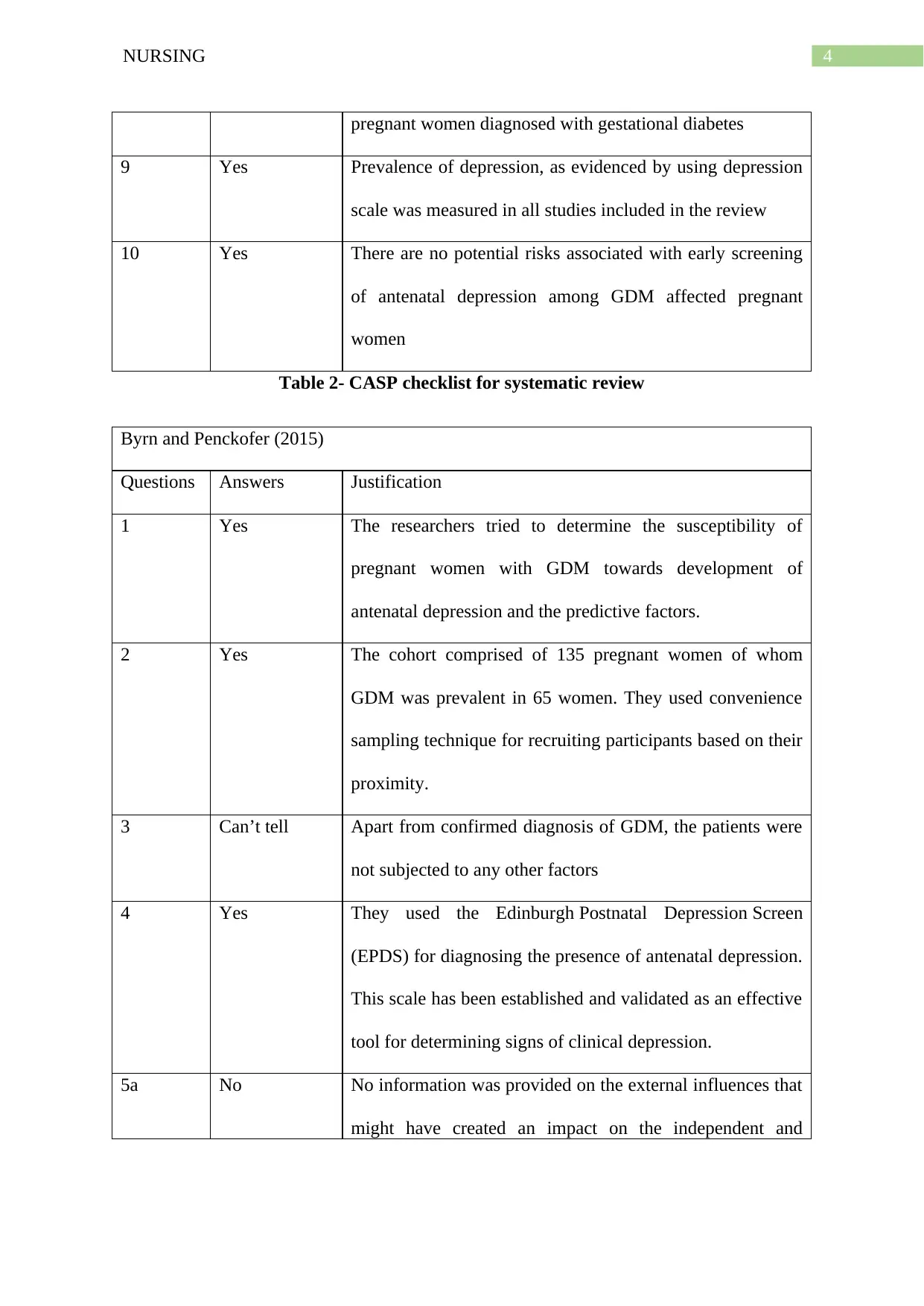

Byrn and Penckofer (2015)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes The researchers tried to determine the susceptibility of

pregnant women with GDM towards development of

antenatal depression and the predictive factors.

2 Yes The cohort comprised of 135 pregnant women of whom

GDM was prevalent in 65 women. They used convenience

sampling technique for recruiting participants based on their

proximity.

3 Can’t tell Apart from confirmed diagnosis of GDM, the patients were

not subjected to any other factors

4 Yes They used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen

(EPDS) for diagnosing the presence of antenatal depression.

This scale has been established and validated as an effective

tool for determining signs of clinical depression.

5a No No information was provided on the external influences that

might have created an impact on the independent and

pregnant women diagnosed with gestational diabetes

9 Yes Prevalence of depression, as evidenced by using depression

scale was measured in all studies included in the review

10 Yes There are no potential risks associated with early screening

of antenatal depression among GDM affected pregnant

women

Table 2- CASP checklist for systematic review

Byrn and Penckofer (2015)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes The researchers tried to determine the susceptibility of

pregnant women with GDM towards development of

antenatal depression and the predictive factors.

2 Yes The cohort comprised of 135 pregnant women of whom

GDM was prevalent in 65 women. They used convenience

sampling technique for recruiting participants based on their

proximity.

3 Can’t tell Apart from confirmed diagnosis of GDM, the patients were

not subjected to any other factors

4 Yes They used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen

(EPDS) for diagnosing the presence of antenatal depression.

This scale has been established and validated as an effective

tool for determining signs of clinical depression.

5a No No information was provided on the external influences that

might have created an impact on the independent and

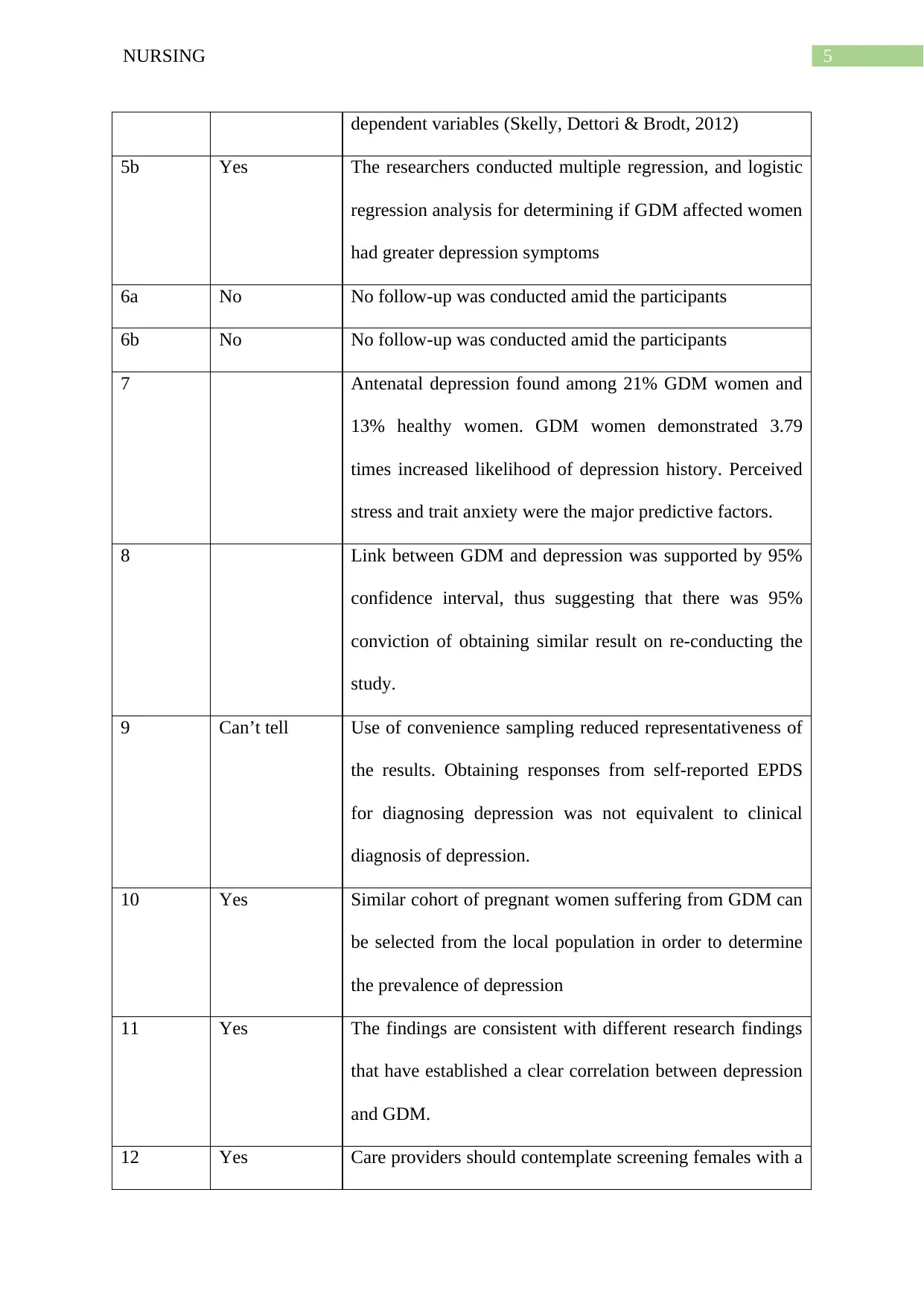

5NURSING

dependent variables (Skelly, Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

5b Yes The researchers conducted multiple regression, and logistic

regression analysis for determining if GDM affected women

had greater depression symptoms

6a No No follow-up was conducted amid the participants

6b No No follow-up was conducted amid the participants

7 Antenatal depression found among 21% GDM women and

13% healthy women. GDM women demonstrated 3.79

times increased likelihood of depression history. Perceived

stress and trait anxiety were the major predictive factors.

8 Link between GDM and depression was supported by 95%

confidence interval, thus suggesting that there was 95%

conviction of obtaining similar result on re-conducting the

study.

9 Can’t tell Use of convenience sampling reduced representativeness of

the results. Obtaining responses from self-reported EPDS

for diagnosing depression was not equivalent to clinical

diagnosis of depression.

10 Yes Similar cohort of pregnant women suffering from GDM can

be selected from the local population in order to determine

the prevalence of depression

11 Yes The findings are consistent with different research findings

that have established a clear correlation between depression

and GDM.

12 Yes Care providers should contemplate screening females with a

dependent variables (Skelly, Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

5b Yes The researchers conducted multiple regression, and logistic

regression analysis for determining if GDM affected women

had greater depression symptoms

6a No No follow-up was conducted amid the participants

6b No No follow-up was conducted amid the participants

7 Antenatal depression found among 21% GDM women and

13% healthy women. GDM women demonstrated 3.79

times increased likelihood of depression history. Perceived

stress and trait anxiety were the major predictive factors.

8 Link between GDM and depression was supported by 95%

confidence interval, thus suggesting that there was 95%

conviction of obtaining similar result on re-conducting the

study.

9 Can’t tell Use of convenience sampling reduced representativeness of

the results. Obtaining responses from self-reported EPDS

for diagnosing depression was not equivalent to clinical

diagnosis of depression.

10 Yes Similar cohort of pregnant women suffering from GDM can

be selected from the local population in order to determine

the prevalence of depression

11 Yes The findings are consistent with different research findings

that have established a clear correlation between depression

and GDM.

12 Yes Care providers should contemplate screening females with a

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6NURSING

depression history, during initial stages of pregnancy for

diagnosing GDM

Table 3- CASP checklist for cross-sectional study

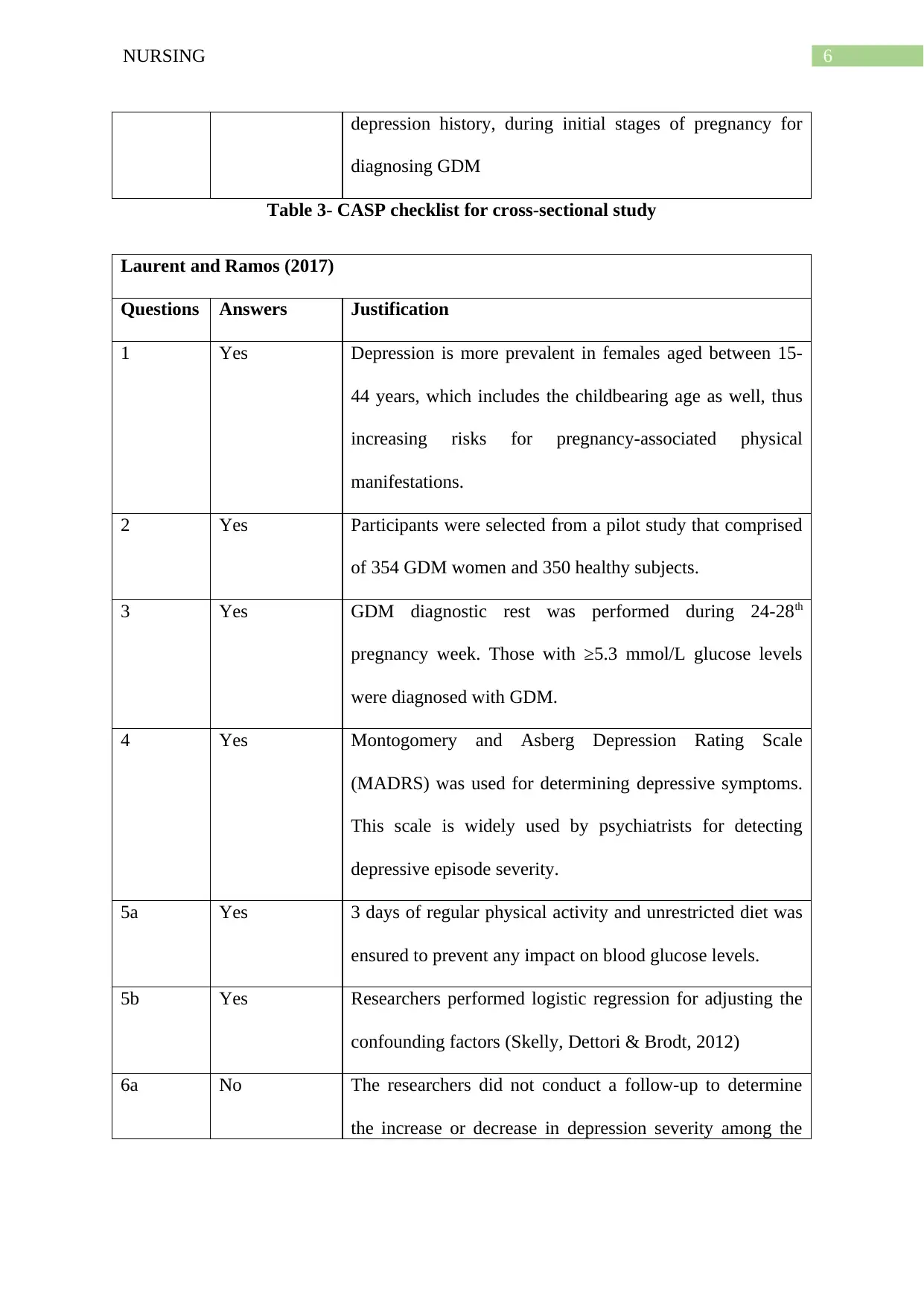

Laurent and Ramos (2017)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes Depression is more prevalent in females aged between 15-

44 years, which includes the childbearing age as well, thus

increasing risks for pregnancy-associated physical

manifestations.

2 Yes Participants were selected from a pilot study that comprised

of 354 GDM women and 350 healthy subjects.

3 Yes GDM diagnostic rest was performed during 24-28th

pregnancy week. Those with ≥5.3 mmol/L glucose levels

were diagnosed with GDM.

4 Yes Montogomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale

(MADRS) was used for determining depressive symptoms.

This scale is widely used by psychiatrists for detecting

depressive episode severity.

5a Yes 3 days of regular physical activity and unrestricted diet was

ensured to prevent any impact on blood glucose levels.

5b Yes Researchers performed logistic regression for adjusting the

confounding factors (Skelly, Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

6a No The researchers did not conduct a follow-up to determine

the increase or decrease in depression severity among the

depression history, during initial stages of pregnancy for

diagnosing GDM

Table 3- CASP checklist for cross-sectional study

Laurent and Ramos (2017)

Questions Answers Justification

1 Yes Depression is more prevalent in females aged between 15-

44 years, which includes the childbearing age as well, thus

increasing risks for pregnancy-associated physical

manifestations.

2 Yes Participants were selected from a pilot study that comprised

of 354 GDM women and 350 healthy subjects.

3 Yes GDM diagnostic rest was performed during 24-28th

pregnancy week. Those with ≥5.3 mmol/L glucose levels

were diagnosed with GDM.

4 Yes Montogomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale

(MADRS) was used for determining depressive symptoms.

This scale is widely used by psychiatrists for detecting

depressive episode severity.

5a Yes 3 days of regular physical activity and unrestricted diet was

ensured to prevent any impact on blood glucose levels.

5b Yes Researchers performed logistic regression for adjusting the

confounding factors (Skelly, Dettori & Brodt, 2012)

6a No The researchers did not conduct a follow-up to determine

the increase or decrease in depression severity among the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

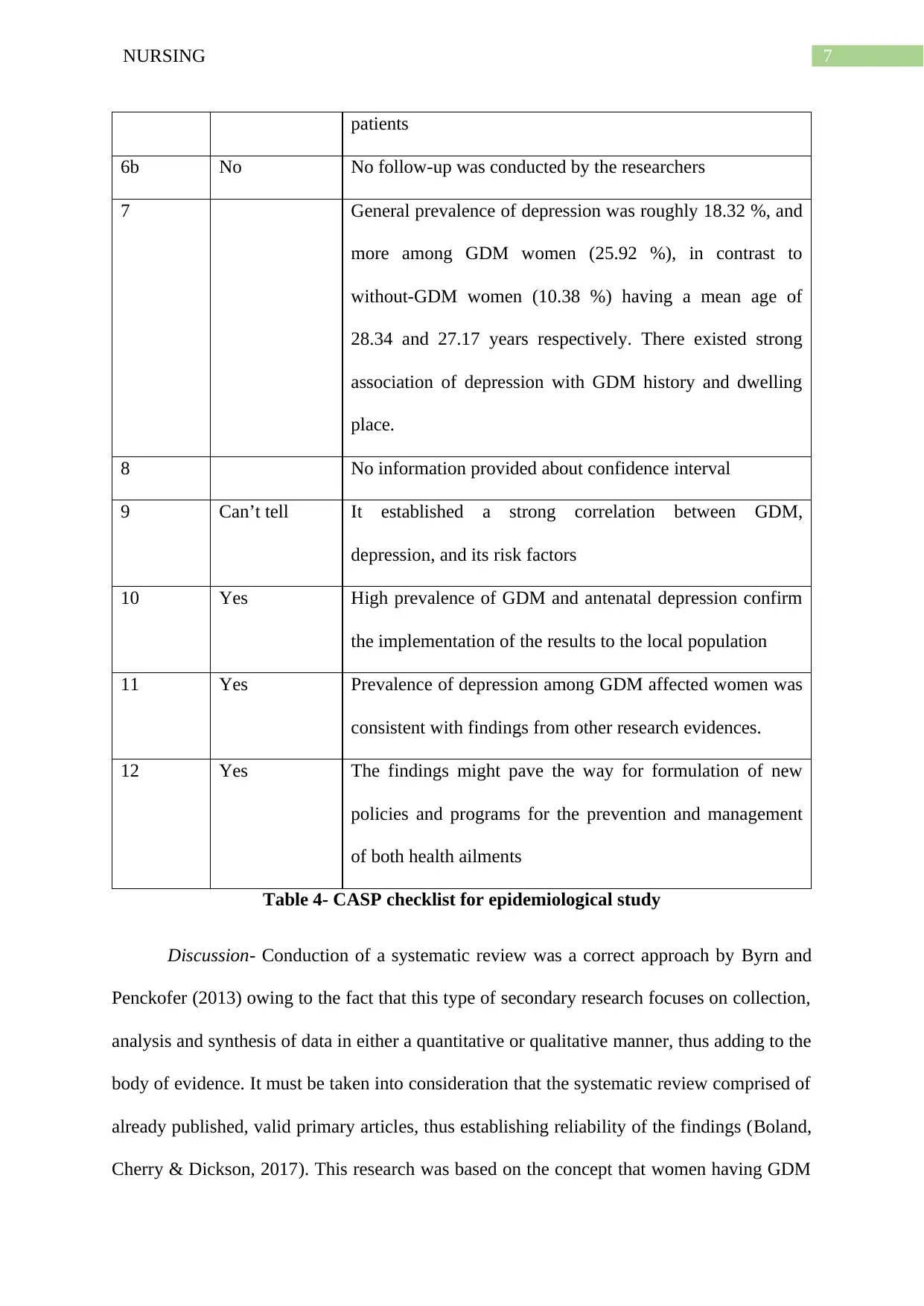

7NURSING

patients

6b No No follow-up was conducted by the researchers

7 General prevalence of depression was roughly 18.32 %, and

more among GDM women (25.92 %), in contrast to

without-GDM women (10.38 %) having a mean age of

28.34 and 27.17 years respectively. There existed strong

association of depression with GDM history and dwelling

place.

8 No information provided about confidence interval

9 Can’t tell It established a strong correlation between GDM,

depression, and its risk factors

10 Yes High prevalence of GDM and antenatal depression confirm

the implementation of the results to the local population

11 Yes Prevalence of depression among GDM affected women was

consistent with findings from other research evidences.

12 Yes The findings might pave the way for formulation of new

policies and programs for the prevention and management

of both health ailments

Table 4- CASP checklist for epidemiological study

Discussion- Conduction of a systematic review was a correct approach by Byrn and

Penckofer (2013) owing to the fact that this type of secondary research focuses on collection,

analysis and synthesis of data in either a quantitative or qualitative manner, thus adding to the

body of evidence. It must be taken into consideration that the systematic review comprised of

already published, valid primary articles, thus establishing reliability of the findings (Boland,

Cherry & Dickson, 2017). This research was based on the concept that women having GDM

patients

6b No No follow-up was conducted by the researchers

7 General prevalence of depression was roughly 18.32 %, and

more among GDM women (25.92 %), in contrast to

without-GDM women (10.38 %) having a mean age of

28.34 and 27.17 years respectively. There existed strong

association of depression with GDM history and dwelling

place.

8 No information provided about confidence interval

9 Can’t tell It established a strong correlation between GDM,

depression, and its risk factors

10 Yes High prevalence of GDM and antenatal depression confirm

the implementation of the results to the local population

11 Yes Prevalence of depression among GDM affected women was

consistent with findings from other research evidences.

12 Yes The findings might pave the way for formulation of new

policies and programs for the prevention and management

of both health ailments

Table 4- CASP checklist for epidemiological study

Discussion- Conduction of a systematic review was a correct approach by Byrn and

Penckofer (2013) owing to the fact that this type of secondary research focuses on collection,

analysis and synthesis of data in either a quantitative or qualitative manner, thus adding to the

body of evidence. It must be taken into consideration that the systematic review comprised of

already published, valid primary articles, thus establishing reliability of the findings (Boland,

Cherry & Dickson, 2017). This research was based on the concept that women having GDM

8NURSING

often report signs and symptoms of depression during their pregnancy (Ruohomäki et al.,

2018). It has often been established that formulating an appropriate inclusion and exclusion

criteria help in extraction of articles that are most pertinent to the research phenomenon being

investigated (). Thus, inclusion of all six articles that had been published till the review was

accurate. Critical analysis is mandatory in a systematic review since it helps in evaluating the

reliability of the findings that have been included. Nonetheless, lack of any such analysis

might have led to bias in the results. It is imperative for researchers to include studies in a

review that have high precision such that on performing identical research in the target

population, similar results are obtained. However, presence of 95% CI in two of the six

included studies reduced reliability of the findings (Greenland et al., 2016).

The findings can be easily applied to the local population since GDM is common

among 12% and 14% of pregnant Australian women. Thus, they can be selected from the

primary care centres, followed by determination of the incidence and prevalence of antenatal

depression. Use of depression scale ensured that all outcomes were considered in the

individual studies since they comprise of questionnaire that provide an indication for the

severity of different depressive symptoms like suicide ideation, agitation, weight loss,

somatic symptoms, low mood, and insomnia (Howard et al., 2018). Few strategies that could

have been adopted to increase reliability of the systematic review are namely, (i) involving

two or more committee experts who will independently select and appraise the articles to

prevent bias, (ii) development of a review protocol for data collection and appraisal, and (iii)

conducting a meta-analysis that will combine results from the quantitative studies and

compare them to recognise the common effect (Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe & Shiell, 2002).

The second research by Byrn and Penckofer (2015) was based on a cross-sectional

design, which can be cited as correct owing to the fact that it allowed assessment of a range

of variables within a definite time, and also facilitated routine collection of data at little or no

often report signs and symptoms of depression during their pregnancy (Ruohomäki et al.,

2018). It has often been established that formulating an appropriate inclusion and exclusion

criteria help in extraction of articles that are most pertinent to the research phenomenon being

investigated (). Thus, inclusion of all six articles that had been published till the review was

accurate. Critical analysis is mandatory in a systematic review since it helps in evaluating the

reliability of the findings that have been included. Nonetheless, lack of any such analysis

might have led to bias in the results. It is imperative for researchers to include studies in a

review that have high precision such that on performing identical research in the target

population, similar results are obtained. However, presence of 95% CI in two of the six

included studies reduced reliability of the findings (Greenland et al., 2016).

The findings can be easily applied to the local population since GDM is common

among 12% and 14% of pregnant Australian women. Thus, they can be selected from the

primary care centres, followed by determination of the incidence and prevalence of antenatal

depression. Use of depression scale ensured that all outcomes were considered in the

individual studies since they comprise of questionnaire that provide an indication for the

severity of different depressive symptoms like suicide ideation, agitation, weight loss,

somatic symptoms, low mood, and insomnia (Howard et al., 2018). Few strategies that could

have been adopted to increase reliability of the systematic review are namely, (i) involving

two or more committee experts who will independently select and appraise the articles to

prevent bias, (ii) development of a review protocol for data collection and appraisal, and (iii)

conducting a meta-analysis that will combine results from the quantitative studies and

compare them to recognise the common effect (Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe & Shiell, 2002).

The second research by Byrn and Penckofer (2015) was based on a cross-sectional

design, which can be cited as correct owing to the fact that it allowed assessment of a range

of variables within a definite time, and also facilitated routine collection of data at little or no

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9NURSING

expense (Parahoo, 2014). Evidences illustrate that assessment of exposure with great

specificity is imperative for minimalizing bias, owing to measurement error. The researchers

classified the study subjects into two groups, based on GDM diagnosis, thus ensuring that

there was no bias in the group allocation. However, use of convenience sampling was a major

limitation since the sample was not representative of the entire population, thus leading to

systematic bias (Emerson, 2015). This could be addressed if purposive sampling procedure

had been followed. Use of EPDS scale proved effective since the 10-item questionnaire

specifically addresses females with postnatal depression. Though the authors conducted

multiple regression, and logistic regression for confounding variable adjustment, clear

information was not provided on the range of variables.

Owing to the fact that confounding variables alter the impact of independent and

dependent variables, the researchers must have addressed the extraneous influence on the

outcomes, to prevent threat to internal validity (Halperin, Pyne & Martin, 2015). Follow-up

steps form an essential component of all investigation and are generally conducted in order to

ascertain the long-term health outcomes of the target population. Thus, the researchers should

have observed whether the symptoms of depression persisted throughout and after pregnancy.

Questions must have been formulated that assess the occupation, lifestyle and other

exposures, thereby categorising the stud subjects. In addition, recall bias must have been

prevented by using high-quality questionnaire and blinding the researchers to the participants

such that they will not be aware of the GDM status of study subjects (Rychetnik, Frommer,

Hawe & Shiell, 2002).

Laurent and Ramos (2017) conducted an epidemiological study for determining the

prevalence of depression among pregnant females, with or without GDM. This was a correct

research design since epidemiology encompasses the study of prevalence or incidence of

diseases in a particular population, besides determining the protective and risk factors

expense (Parahoo, 2014). Evidences illustrate that assessment of exposure with great

specificity is imperative for minimalizing bias, owing to measurement error. The researchers

classified the study subjects into two groups, based on GDM diagnosis, thus ensuring that

there was no bias in the group allocation. However, use of convenience sampling was a major

limitation since the sample was not representative of the entire population, thus leading to

systematic bias (Emerson, 2015). This could be addressed if purposive sampling procedure

had been followed. Use of EPDS scale proved effective since the 10-item questionnaire

specifically addresses females with postnatal depression. Though the authors conducted

multiple regression, and logistic regression for confounding variable adjustment, clear

information was not provided on the range of variables.

Owing to the fact that confounding variables alter the impact of independent and

dependent variables, the researchers must have addressed the extraneous influence on the

outcomes, to prevent threat to internal validity (Halperin, Pyne & Martin, 2015). Follow-up

steps form an essential component of all investigation and are generally conducted in order to

ascertain the long-term health outcomes of the target population. Thus, the researchers should

have observed whether the symptoms of depression persisted throughout and after pregnancy.

Questions must have been formulated that assess the occupation, lifestyle and other

exposures, thereby categorising the stud subjects. In addition, recall bias must have been

prevented by using high-quality questionnaire and blinding the researchers to the participants

such that they will not be aware of the GDM status of study subjects (Rychetnik, Frommer,

Hawe & Shiell, 2002).

Laurent and Ramos (2017) conducted an epidemiological study for determining the

prevalence of depression among pregnant females, with or without GDM. This was a correct

research design since epidemiology encompasses the study of prevalence or incidence of

diseases in a particular population, besides determining the protective and risk factors

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10NURSING

(Parahoo, 2014). They selected participants from a pilot study. Pilot study refers to a

preliminary trial that is usually conducted for determining duration, feasibility and adverse

events of a project (Patten & Newhart, 2017). Although use of the MADRS helped in

obtaining self-reports of depression symptoms, it was imperative to conduct a clinical

diagnosis based on DSM-V criteria for diagnosing antenatal depression. Owing to the impact

that confounding variables create on the research outcomes, adjusting these variables using

logistic regression ensured that there was no external influence on the link between

dependent and independent variables (Greenland et al. 2016). Follow-up was also not

conducted, thus leading to failure in determining the long-term causal association. Steps that

could have improved this research are namely, (i) disclosing the foreknowledge of outcome,

(ii) gaining a sound understanding of key data and its inherent variability, and (iii)

incorporating detailed exposure characterisation (Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe & Shiell,

2002).

Conclusion- Thus, it can be concluded that antenatal depression is prevalent among

pregnant females and the condition is generally manifested in the form of unusual worry,

apprehensions, chronic anxiety, and emotional detachment. This condition is most prevalent

among females who have been diagnosed with GDM, which refers to an increase in blood

glucose levels. On conducting a critical appraisal of the three selected articles, it was found

that all three of them established a clear association between GDM and antenatal depression,

thus calling for the need of conducting health screening, in order to facilitate early diagnosis.

Early detection of the condition would prevent health deterioration, and enhance the physical

and mental wellbeing of pregnant females.

References

(Parahoo, 2014). They selected participants from a pilot study. Pilot study refers to a

preliminary trial that is usually conducted for determining duration, feasibility and adverse

events of a project (Patten & Newhart, 2017). Although use of the MADRS helped in

obtaining self-reports of depression symptoms, it was imperative to conduct a clinical

diagnosis based on DSM-V criteria for diagnosing antenatal depression. Owing to the impact

that confounding variables create on the research outcomes, adjusting these variables using

logistic regression ensured that there was no external influence on the link between

dependent and independent variables (Greenland et al. 2016). Follow-up was also not

conducted, thus leading to failure in determining the long-term causal association. Steps that

could have improved this research are namely, (i) disclosing the foreknowledge of outcome,

(ii) gaining a sound understanding of key data and its inherent variability, and (iii)

incorporating detailed exposure characterisation (Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe & Shiell,

2002).

Conclusion- Thus, it can be concluded that antenatal depression is prevalent among

pregnant females and the condition is generally manifested in the form of unusual worry,

apprehensions, chronic anxiety, and emotional detachment. This condition is most prevalent

among females who have been diagnosed with GDM, which refers to an increase in blood

glucose levels. On conducting a critical appraisal of the three selected articles, it was found

that all three of them established a clear association between GDM and antenatal depression,

thus calling for the need of conducting health screening, in order to facilitate early diagnosis.

Early detection of the condition would prevent health deterioration, and enhance the physical

and mental wellbeing of pregnant females.

References

11NURSING

Boland, A., Cherry, G., & Dickson, R. (Eds.). (2017). Doing a systematic review: A student's

guide. Sage. https://books.google.co.in/books?

hl=en&lr=&id=Zpc3DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=systematic+review+step&o

ts=KhIa6CQSA8&sig=6A8wSv2qxGGAy96rfE5coRXfTas#v=onepage&q=systemati

c%20review%20step&f=false

Byrn, M. A., & Penckofer, S. (2013). Antenatal Depression and Gestational Diabetes: A

Review of Maternaland Fetal Outcomes. Nursing for women's health, 17(1), 22-33.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-486X.12003

Byrn, M., & Penckofer, S. (2015). The relationship between gestational diabetes and

antenatal depression. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 44(2),

246-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12554

CASP UK. (2018). CASP checklists. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP): Making

sense of evidence. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Castro, R. T. A., Glover, V., Ehlert, U., & O'Connor, T. G. (2017). Antenatal psychological

and socioeconomic predictors of breastfeeding in a large community sample. Early

human development, 110, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.04.010

Doyle, J. (2017). Perinatal depression screening: using antenatal depression screens and

patient demographics to predict risk for postpartum depression.

https://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://

scholar.google.co.in/&httpsredir=1&article=2967&context=theses

Emerson, R. W. (2015). Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling:

How does sampling affect the validity of research?. Journal of Visual Impairment &

Blindness, 109(2), 164-168. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0145482X1510900215

Boland, A., Cherry, G., & Dickson, R. (Eds.). (2017). Doing a systematic review: A student's

guide. Sage. https://books.google.co.in/books?

hl=en&lr=&id=Zpc3DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=systematic+review+step&o

ts=KhIa6CQSA8&sig=6A8wSv2qxGGAy96rfE5coRXfTas#v=onepage&q=systemati

c%20review%20step&f=false

Byrn, M. A., & Penckofer, S. (2013). Antenatal Depression and Gestational Diabetes: A

Review of Maternaland Fetal Outcomes. Nursing for women's health, 17(1), 22-33.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-486X.12003

Byrn, M., & Penckofer, S. (2015). The relationship between gestational diabetes and

antenatal depression. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 44(2),

246-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12554

CASP UK. (2018). CASP checklists. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP): Making

sense of evidence. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Castro, R. T. A., Glover, V., Ehlert, U., & O'Connor, T. G. (2017). Antenatal psychological

and socioeconomic predictors of breastfeeding in a large community sample. Early

human development, 110, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.04.010

Doyle, J. (2017). Perinatal depression screening: using antenatal depression screens and

patient demographics to predict risk for postpartum depression.

https://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://

scholar.google.co.in/&httpsredir=1&article=2967&context=theses

Emerson, R. W. (2015). Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling:

How does sampling affect the validity of research?. Journal of Visual Impairment &

Blindness, 109(2), 164-168. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0145482X1510900215

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.