Design-Build Project Delivery vs Traditional Procurement Methods

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/13

|122

|38376

|338

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an overview of innovative project delivery methods for infrastructure, with an international perspective, focusing on the road sector. It contrasts traditional Design-Bid-Build methods with more progressive approaches like Design-Build (DB), Design-Build Operate Maintain (DBOM), and Design-Build Finance Operate (DBFO). The study, incorporating data from countries like Australia, Canada, England, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, and the USA, highlights the advantages and disadvantages of various maintenance contract types, including traditional, hybrid, long-term, and Performance Specified Maintenance Contracts (PSMC). The report emphasizes the importance of partnering, lump sum contracts, and quality-based contractor selection for maximizing innovation in infrastructure projects. It concludes that adopting innovative methods requires a paradigm shift but is essential for keeping pace with societal changes and improving infrastructure management.

Pekka Pakkala

Finnish Road

Enterprise

Helsinki 2002

Finnish Road

Enterprise

Innovative Project Delivery

Methods for Infrastructure

An International Perspective

Finnish Road

Enterprise

Helsinki 2002

Finnish Road

Enterprise

Innovative Project Delivery

Methods for Infrastructure

An International Perspective

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pekka Pakkala

Innovative Project Delivery Methods for

Infrastructure

An International Perspective

Finnish Road Enterprise

Headquarters

Helsinki 2002

Innovative Project Delivery Methods for

Infrastructure

An International Perspective

Finnish Road Enterprise

Headquarters

Helsinki 2002

Cover: Tapio Kalliomäki

ISBN 952-5408-05-1

Oy Edita Ab

Helsinki 2002

Finnish Road Enterprise

Opastinsilta 12 B

P.O.Box 73

FIN-00521 HELSINKI

Tel. + 358 20 444 11

ISBN 952-5408-05-1

Oy Edita Ab

Helsinki 2002

Finnish Road Enterprise

Opastinsilta 12 B

P.O.Box 73

FIN-00521 HELSINKI

Tel. + 358 20 444 11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

PAKKALA, Pekka: Innovative Project Delivery Methods for Infrastructure –

An International Perspective. Helsinki 2002. Finnish Road Enterprise, Headquarters.

ISBN 952-5408-05-1

Executive Summary

Many countries around the world are attempting to answer the key

challenges to the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure

networks that are essential to the economic stability within their respective

countries. Society is rapidly changing and public clients are trying to meet

the critical needs of this fast-paced society. Aging infrastructures, cost

escalation, limited resources, productivity, acute regional development,

environmental issues, and sprawling growth are causing concern to the

management and administration of infrastructure networks. These are

strong incentives for seeking alternative and innovative means to procure

the main foundations of society and maintain economic stability.

This study, called “Innovative Project Delivery Methods For Infrastructure -

An International Perspective”, attempts to demonstrate practices and

methods that can be utilized by client organizations to more effectively

secure products and services. The goal is to share some of the most

innovative or at least the most progressive methods used in several

countries. It is important to distinguish between the delivery methods used

for “Capital Projects” and “Maintenance Contracts”. The details contained in

this report are from data and information gathered mostly from the road

sector, but they have implications that can be utilized in other infrastructure

sectors, as well. The countries included in this study are Australia, Canada

(Alberta, British Columbia & Ontario), England, Finland, New Zealand,

Sweden, and the USA.

Capital Projects

Most countries use traditional methods (Design-Bid-Build) to procure capital

investment projects, and all countries seem to be continuing with this

process, except for England, which uses alternative or innovative methods

extensively. The innovative or progressive methods identified in this study

are listed as follows:

• Design-Build (DB)

• Design-Build Operate Maintain (DBOM)

• Design-Build Finance Operate (DBFO)

• Full Delivery or Program Management

Figure 4 in the introduction section displays these methods quite well and

indicates some of the attributes included in these methods. Other innovative

aspects that could be used in conjunction with traditional and innovative

procurement methods are as follows:

An International Perspective. Helsinki 2002. Finnish Road Enterprise, Headquarters.

ISBN 952-5408-05-1

Executive Summary

Many countries around the world are attempting to answer the key

challenges to the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure

networks that are essential to the economic stability within their respective

countries. Society is rapidly changing and public clients are trying to meet

the critical needs of this fast-paced society. Aging infrastructures, cost

escalation, limited resources, productivity, acute regional development,

environmental issues, and sprawling growth are causing concern to the

management and administration of infrastructure networks. These are

strong incentives for seeking alternative and innovative means to procure

the main foundations of society and maintain economic stability.

This study, called “Innovative Project Delivery Methods For Infrastructure -

An International Perspective”, attempts to demonstrate practices and

methods that can be utilized by client organizations to more effectively

secure products and services. The goal is to share some of the most

innovative or at least the most progressive methods used in several

countries. It is important to distinguish between the delivery methods used

for “Capital Projects” and “Maintenance Contracts”. The details contained in

this report are from data and information gathered mostly from the road

sector, but they have implications that can be utilized in other infrastructure

sectors, as well. The countries included in this study are Australia, Canada

(Alberta, British Columbia & Ontario), England, Finland, New Zealand,

Sweden, and the USA.

Capital Projects

Most countries use traditional methods (Design-Bid-Build) to procure capital

investment projects, and all countries seem to be continuing with this

process, except for England, which uses alternative or innovative methods

extensively. The innovative or progressive methods identified in this study

are listed as follows:

• Design-Build (DB)

• Design-Build Operate Maintain (DBOM)

• Design-Build Finance Operate (DBFO)

• Full Delivery or Program Management

Figure 4 in the introduction section displays these methods quite well and

indicates some of the attributes included in these methods. Other innovative

aspects that could be used in conjunction with traditional and innovative

procurement methods are as follows:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

• Partnering

• Value Engineering

• Constructability Reviews

• Incentive and Disincentives

• Performance Specifications

• Multi-parameter Bidding (A+B+Quality)

• Lane Rental

More details on capital investment projects are discussed in the “Capital

Project Delivery Methods” section.

Maintenance Contracts

Maintenance procurement is quite a different aspect because the

infrastructure is already in place, but it needs to be maintained properly and

rehabilitation and/or improvements need to be provided before any major

deformation or deterioration occurs that effects safe usage. Previously, most

organizations retained in-house staff for most maintenance activities, but

now many client organizations must procure these services and products

from the private sector.

Earlier practices for procurement of maintenance were via yearly or multi-

year agreements, using separate contracts for each activity and with a labor

rate or unit price. More recently, there are innovative methods of procuring

maintenance activities for all products and services under one contract and

for a long term. The more innovative types of contracts are also beginning to

specify “outcome-based criteria”, which provides the contractor with more

flexibility, innovation potential, and cost savings measures for the client

organization. The contract mechanism is via a “Lump Sum” contract for all

these products and services over the duration of the contract period, and by

using a “quality-based contractor selection method” to ensure the success

of the project. More details can be found in the “Maintenance Procurement”

section.

Innovative maintenance contracts can be categorized by the following:

• Traditional 3 – 5-year duration

• Hybrid type contracts (Combination of Lump Sum and Unit Price -

Schedule of Rates)

• Longer term maintenance contracts (some are for 10 years)

• Performance Specified Maintenance Contracts (PSMC – Outcome-

Based Criteria)

• Value Engineering

• Constructability Reviews

• Incentive and Disincentives

• Performance Specifications

• Multi-parameter Bidding (A+B+Quality)

• Lane Rental

More details on capital investment projects are discussed in the “Capital

Project Delivery Methods” section.

Maintenance Contracts

Maintenance procurement is quite a different aspect because the

infrastructure is already in place, but it needs to be maintained properly and

rehabilitation and/or improvements need to be provided before any major

deformation or deterioration occurs that effects safe usage. Previously, most

organizations retained in-house staff for most maintenance activities, but

now many client organizations must procure these services and products

from the private sector.

Earlier practices for procurement of maintenance were via yearly or multi-

year agreements, using separate contracts for each activity and with a labor

rate or unit price. More recently, there are innovative methods of procuring

maintenance activities for all products and services under one contract and

for a long term. The more innovative types of contracts are also beginning to

specify “outcome-based criteria”, which provides the contractor with more

flexibility, innovation potential, and cost savings measures for the client

organization. The contract mechanism is via a “Lump Sum” contract for all

these products and services over the duration of the contract period, and by

using a “quality-based contractor selection method” to ensure the success

of the project. More details can be found in the “Maintenance Procurement”

section.

Innovative maintenance contracts can be categorized by the following:

• Traditional 3 – 5-year duration

• Hybrid type contracts (Combination of Lump Sum and Unit Price -

Schedule of Rates)

• Longer term maintenance contracts (some are for 10 years)

• Performance Specified Maintenance Contracts (PSMC – Outcome-

Based Criteria)

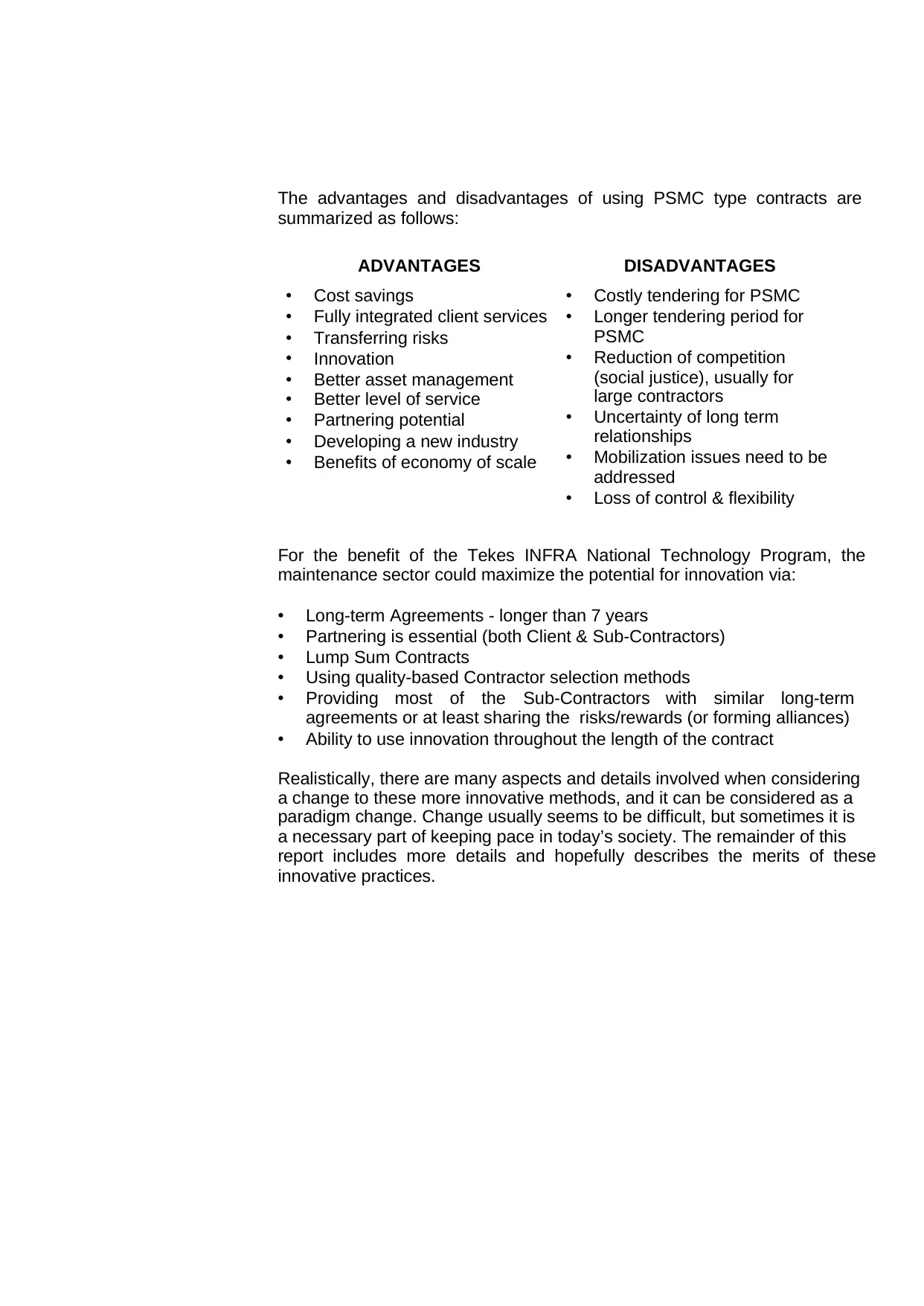

The advantages and disadvantages of using PSMC type contracts are

summarized as follows:

ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES

• Cost savings

• Fully integrated client services

• Transferring risks

• Innovation

• Better asset management

• Better level of service

• Partnering potential

• Developing a new industry

• Benefits of economy of scale

• Costly tendering for PSMC

• Longer tendering period for

PSMC

• Reduction of competition

(social justice), usually for

large contractors

• Uncertainty of long term

relationships

• Mobilization issues need to be

addressed

• Loss of control & flexibility

For the benefit of the Tekes INFRA National Technology Program, the

maintenance sector could maximize the potential for innovation via:

• Long-term Agreements - longer than 7 years

• Partnering is essential (both Client & Sub-Contractors)

• Lump Sum Contracts

• Using quality-based Contractor selection methods

• Providing most of the Sub-Contractors with similar long-term

agreements or at least sharing the risks/rewards (or forming alliances)

• Ability to use innovation throughout the length of the contract

Realistically, there are many aspects and details involved when considering

a change to these more innovative methods, and it can be considered as a

paradigm change. Change usually seems to be difficult, but sometimes it is

a necessary part of keeping pace in today’s society. The remainder of this

report includes more details and hopefully describes the merits of these

innovative practices.

summarized as follows:

ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES

• Cost savings

• Fully integrated client services

• Transferring risks

• Innovation

• Better asset management

• Better level of service

• Partnering potential

• Developing a new industry

• Benefits of economy of scale

• Costly tendering for PSMC

• Longer tendering period for

PSMC

• Reduction of competition

(social justice), usually for

large contractors

• Uncertainty of long term

relationships

• Mobilization issues need to be

addressed

• Loss of control & flexibility

For the benefit of the Tekes INFRA National Technology Program, the

maintenance sector could maximize the potential for innovation via:

• Long-term Agreements - longer than 7 years

• Partnering is essential (both Client & Sub-Contractors)

• Lump Sum Contracts

• Using quality-based Contractor selection methods

• Providing most of the Sub-Contractors with similar long-term

agreements or at least sharing the risks/rewards (or forming alliances)

• Ability to use innovation throughout the length of the contract

Realistically, there are many aspects and details involved when considering

a change to these more innovative methods, and it can be considered as a

paradigm change. Change usually seems to be difficult, but sometimes it is

a necessary part of keeping pace in today’s society. The remainder of this

report includes more details and hopefully describes the merits of these

innovative practices.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

FOREWORD

Tekes (National Technology Agency of Finland) initiated a new National

Technology Program in January 2001, called INFRA. The INFRA program

was created to assist in the development of a more sustainable,

competitive, and innovative environment for the infrastructure sectors.

These sectors, sometimes referred to as public works, consist mainly of

transport, communications, utilities, and other physical networks. Some

aspects of infrastructure includes design, construction, raw materials,

production, maintenance and upkeep, improvements, and possibly removal

after its life cycle is exhausted.

This project is mostly funded by Tekes, the Finnish Road Administration

(Finnra) and the Finnish Road Enterprise, and partially by VR-Track Ltd.,

The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, and The Central

Association of Earthmoving Contractors in Finland (SML). This specific

project is managed by the Finnish Road Enterprise, and its content is mainly

focused on project delivery processes for the road sector. Other sectors of

infrastructure use these same traditional or innovative methods in their

procurement of transportation networks and projects, and the project

delivery methods discussed in this report can be utilized by most public

infrastructure projects. However, it should be understood that most of the

content in this report is focused on issues and studies from the road sector.

Part of the INFRA program’s objective is to formulate and improve project

delivery processes that are expected to create a more competitive setting,

which leads to improved management, quality, innovative products and

services, partnering initiatives, and a more sustainable environment. This

lead to the development of the vision for this project. Global changes and

previous studies have demonstrated that creating an innovative

procurement delivery system leads to improvements. For example, the

building technology sector has demonstrated improvements and innovation

as a result of clients’ innovative project delivery systems. These similar

concepts could be adapted to the infrastructure sector.

There are several project delivery models utilized in transportation projects

throughout the world, but the “traditional“ project delivery model seems to be

the most broadly accepted practice and most extensively used. The type of

project delivery model used by the public entity can have a significant effect

on the ability to adapt new, not fully-tested technologies, the degree of

management burden, financing, and indirectly, the competitive market. As

society has progressed, increased pressure and accountability have been

placed on public administrations to provide a safe, reliable and functional

transport infrastructure, while effectively maintaining budget and financial

constrictions. This needs to be accomplished despite possible staffing

reductions, an aging infrastructure, and the need to account for future

technologies (such as Information Technology) that are not presently

available, but may be available in the years ahead.

Hence, this project was developed in order to seek out and evaluate the

most innovative project delivery systems in use by the most progressive

countries, not only for new construction projects, but especially for

Tekes (National Technology Agency of Finland) initiated a new National

Technology Program in January 2001, called INFRA. The INFRA program

was created to assist in the development of a more sustainable,

competitive, and innovative environment for the infrastructure sectors.

These sectors, sometimes referred to as public works, consist mainly of

transport, communications, utilities, and other physical networks. Some

aspects of infrastructure includes design, construction, raw materials,

production, maintenance and upkeep, improvements, and possibly removal

after its life cycle is exhausted.

This project is mostly funded by Tekes, the Finnish Road Administration

(Finnra) and the Finnish Road Enterprise, and partially by VR-Track Ltd.,

The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, and The Central

Association of Earthmoving Contractors in Finland (SML). This specific

project is managed by the Finnish Road Enterprise, and its content is mainly

focused on project delivery processes for the road sector. Other sectors of

infrastructure use these same traditional or innovative methods in their

procurement of transportation networks and projects, and the project

delivery methods discussed in this report can be utilized by most public

infrastructure projects. However, it should be understood that most of the

content in this report is focused on issues and studies from the road sector.

Part of the INFRA program’s objective is to formulate and improve project

delivery processes that are expected to create a more competitive setting,

which leads to improved management, quality, innovative products and

services, partnering initiatives, and a more sustainable environment. This

lead to the development of the vision for this project. Global changes and

previous studies have demonstrated that creating an innovative

procurement delivery system leads to improvements. For example, the

building technology sector has demonstrated improvements and innovation

as a result of clients’ innovative project delivery systems. These similar

concepts could be adapted to the infrastructure sector.

There are several project delivery models utilized in transportation projects

throughout the world, but the “traditional“ project delivery model seems to be

the most broadly accepted practice and most extensively used. The type of

project delivery model used by the public entity can have a significant effect

on the ability to adapt new, not fully-tested technologies, the degree of

management burden, financing, and indirectly, the competitive market. As

society has progressed, increased pressure and accountability have been

placed on public administrations to provide a safe, reliable and functional

transport infrastructure, while effectively maintaining budget and financial

constrictions. This needs to be accomplished despite possible staffing

reductions, an aging infrastructure, and the need to account for future

technologies (such as Information Technology) that are not presently

available, but may be available in the years ahead.

Hence, this project was developed in order to seek out and evaluate the

most innovative project delivery systems in use by the most progressive

countries, not only for new construction projects, but especially for

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

maintenance type contracts. The project duration is from January 1, 2001

through December 31, 2001. Considering the budget and time constraints, it

is not practical nor possible to evaluate all countries, but rather to

strategically incorporate and analyze the most progressive ones. That is the

process and objectives that were adapted in this study.

The research approach to this project was to gather as much written details

via reports, technical papers, conferences, internet searches, and contacts

throughout the industry. It is important to understand that there is only a

limited amount of information available through these sources, and it was

necessary to hold informal interviews/meetings with the appropriate

authorities in the progressive countries included in this study, which are

Australia, Canada (Alberta, British Columbia & Ontario), England, Finland,

New Zealand, Sweden, and the USA. The goal was to uncover innovative

practices for both capital and maintenance contracts, evaluate the best

practices, outline the lessons learned, and determine which methods might

be appropriate as a model in Finland. As part of the Tekes project, the

objective was to determine which delivery mechanisms would stimulate

innovation in the infrastructure sector.

through December 31, 2001. Considering the budget and time constraints, it

is not practical nor possible to evaluate all countries, but rather to

strategically incorporate and analyze the most progressive ones. That is the

process and objectives that were adapted in this study.

The research approach to this project was to gather as much written details

via reports, technical papers, conferences, internet searches, and contacts

throughout the industry. It is important to understand that there is only a

limited amount of information available through these sources, and it was

necessary to hold informal interviews/meetings with the appropriate

authorities in the progressive countries included in this study, which are

Australia, Canada (Alberta, British Columbia & Ontario), England, Finland,

New Zealand, Sweden, and the USA. The goal was to uncover innovative

practices for both capital and maintenance contracts, evaluate the best

practices, outline the lessons learned, and determine which methods might

be appropriate as a model in Finland. As part of the Tekes project, the

objective was to determine which delivery mechanisms would stimulate

innovation in the infrastructure sector.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project would not have been possible without the support of many

Finnish organizations and especially Tekes, which launched the INFRA

National Technology Program in January 2001. It is also necessary to

express appreciation for the support provided by the Finnish Road

Administration (Finnra) and the Finnish Road Enterprise, and also to VR-

Track Ltd., The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, and

The Central Association of Earthmoving Contractors in Finland (SML).

It is also appropriate and correct to provide recognition to my innovative and

pro-active colleague, Mr. Markku Teppo, to whom I am personally grateful.

Not only is financial support needed, but also the cooperation of many

organizations that participated throughout the world. I would personally like

to express my warm thanks and appreciation to all the organizations (listed

below) and people that participated and provided their valuable time and

effort in order to share in the need to develop innovative practices and

processes. It is so important to share views and opinions that would

hopefully lead to better care and management of the infrastructure network.

Thanks to all who provided their valuable input and expertise.

This report will be made available to all the organizations contributing to the

“outcomes” of this report, and they are mentioned below:

Australia

Egis Consulting

New South Wales - Roads & Traffic Authority

Transfield Services

John Holland Pty. Ltd.

VIC Roads

ARRB Transport Research

Geopave (Vic Roads)

Sinclair Knight Merz Pty. Ltd.

Tasmania DIER

Stornoway Maintenance

Canada

Ministry of Transportation Ontario

IMOS Inc.

Alberta Transportation

Ledcor Industries Ltd.

Ministry of Transportation British Columbia

JJM Construction Ltd.

Emcon Services Inc.

This project would not have been possible without the support of many

Finnish organizations and especially Tekes, which launched the INFRA

National Technology Program in January 2001. It is also necessary to

express appreciation for the support provided by the Finnish Road

Administration (Finnra) and the Finnish Road Enterprise, and also to VR-

Track Ltd., The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, and

The Central Association of Earthmoving Contractors in Finland (SML).

It is also appropriate and correct to provide recognition to my innovative and

pro-active colleague, Mr. Markku Teppo, to whom I am personally grateful.

Not only is financial support needed, but also the cooperation of many

organizations that participated throughout the world. I would personally like

to express my warm thanks and appreciation to all the organizations (listed

below) and people that participated and provided their valuable time and

effort in order to share in the need to develop innovative practices and

processes. It is so important to share views and opinions that would

hopefully lead to better care and management of the infrastructure network.

Thanks to all who provided their valuable input and expertise.

This report will be made available to all the organizations contributing to the

“outcomes” of this report, and they are mentioned below:

Australia

Egis Consulting

New South Wales - Roads & Traffic Authority

Transfield Services

John Holland Pty. Ltd.

VIC Roads

ARRB Transport Research

Geopave (Vic Roads)

Sinclair Knight Merz Pty. Ltd.

Tasmania DIER

Stornoway Maintenance

Canada

Ministry of Transportation Ontario

IMOS Inc.

Alberta Transportation

Ledcor Industries Ltd.

Ministry of Transportation British Columbia

JJM Construction Ltd.

Emcon Services Inc.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

England

Highways Agency

Ringway Highways Ltd.

Amey Highways Ltd.

Halcrow group

Carillion Highway Maintenance Ltd.

WS Atkins Consultants Ltd.

Hertfordshire County Council

New Zealand

Transit New Zealand

Transfund New Zealand

Opus International Consultants

United Contracting

Franklin District Council

Works Infrastructure

Fulton Hogan Auckland

Sweden

Swedish National Road Administration (SNRA)

SNRA Construction and Maintenance

Swedish Rail Administration (Banverket)

NCC AB

Skanska

USA

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)

Flippo Construction

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Massachusetts Highway Department

Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT)

VMS Inc.

Design Build Institute of America

District of Columbia Government DDOT

Shirley Contracting Corporation

Texas Department Of Transportation (TxDOT)

J. D. Abrams Inc.

Highways Agency

Ringway Highways Ltd.

Amey Highways Ltd.

Halcrow group

Carillion Highway Maintenance Ltd.

WS Atkins Consultants Ltd.

Hertfordshire County Council

New Zealand

Transit New Zealand

Transfund New Zealand

Opus International Consultants

United Contracting

Franklin District Council

Works Infrastructure

Fulton Hogan Auckland

Sweden

Swedish National Road Administration (SNRA)

SNRA Construction and Maintenance

Swedish Rail Administration (Banverket)

NCC AB

Skanska

USA

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)

Flippo Construction

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Massachusetts Highway Department

Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT)

VMS Inc.

Design Build Institute of America

District of Columbia Government DDOT

Shirley Contracting Corporation

Texas Department Of Transportation (TxDOT)

J. D. Abrams Inc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

TERMINOLOGY

Asset Management:

The OECD definition for asset management is defined as: A systematic

process of maintaining, upgrading and operating assets, combining

engineering principles with sound business practice and economic rationale,

and providing tools to facilitate a more organized and flexible approach to

making the decisions necessary to achieve the public’s expectations.

Build Own Operate Transfer (BOOT):

Build Own Operate Transfer is a project delivery method similar to DBFO,

except that there is an actual transfer of ownership. The Contractor is

responsible for the design, construction, maintenance, operations, and

financing of the project. The Contractor assumes the risks of financing until

the end of the contract period. Subsequently, the Owner is then responsible

for operations and maintenance of the asset.

Construction Management (CM - At Fee (Agency or Advisor):

This is a process similar to DBB, the traditional model, in which the

Owner/Client is responsible for the Design, Bidding, and Construction of a

project. However, the CM organization takes on the responsibility for

administration & management, constructability issues, day-to-day activities,

and assumes an advisory role to the Owner/ Client. The CM organization

has no contractual obligation to the Design and Construction entities. Again,

the Owner is responsible for operations and maintenance of the project as

well as the financing aspects.

Construction Management - At Risk Advisor (CM - At Risk):

In this scenario the Owner/Client has one agreement with the Construction

Manager, who then manages the contracts with the Design Consultant and

the General Contractor. CM-At Risk assumes much of the risks of the

project, which differentiates this model from CM-Agency and DBB, where

the Owner maintains the risk. Again, the Owner is responsible for operations

and maintenance of the project as well as the financing aspects.

Design-Bid-Build (DBB -Traditional Method):

This system was developed during the Industrial Revolution period, which

resulted in the creation of specialized professional movements of Architects,

Contractors, and Engineers. This approach has been the standard choice of

project delivery systems for many years. In this model, an Owner/Client

procures the services of a Design Consultant to develop the scope of the

project and complete design documents, which are then considered as legal

documents for use in selecting a contractor who builds according to the

specifications developed by the Design Team. Typically, in a public

organization the proposal is in an open competition for a “Low Price”. The

contractor that wins the award is legally bound to produce the project at a

Asset Management:

The OECD definition for asset management is defined as: A systematic

process of maintaining, upgrading and operating assets, combining

engineering principles with sound business practice and economic rationale,

and providing tools to facilitate a more organized and flexible approach to

making the decisions necessary to achieve the public’s expectations.

Build Own Operate Transfer (BOOT):

Build Own Operate Transfer is a project delivery method similar to DBFO,

except that there is an actual transfer of ownership. The Contractor is

responsible for the design, construction, maintenance, operations, and

financing of the project. The Contractor assumes the risks of financing until

the end of the contract period. Subsequently, the Owner is then responsible

for operations and maintenance of the asset.

Construction Management (CM - At Fee (Agency or Advisor):

This is a process similar to DBB, the traditional model, in which the

Owner/Client is responsible for the Design, Bidding, and Construction of a

project. However, the CM organization takes on the responsibility for

administration & management, constructability issues, day-to-day activities,

and assumes an advisory role to the Owner/ Client. The CM organization

has no contractual obligation to the Design and Construction entities. Again,

the Owner is responsible for operations and maintenance of the project as

well as the financing aspects.

Construction Management - At Risk Advisor (CM - At Risk):

In this scenario the Owner/Client has one agreement with the Construction

Manager, who then manages the contracts with the Design Consultant and

the General Contractor. CM-At Risk assumes much of the risks of the

project, which differentiates this model from CM-Agency and DBB, where

the Owner maintains the risk. Again, the Owner is responsible for operations

and maintenance of the project as well as the financing aspects.

Design-Bid-Build (DBB -Traditional Method):

This system was developed during the Industrial Revolution period, which

resulted in the creation of specialized professional movements of Architects,

Contractors, and Engineers. This approach has been the standard choice of

project delivery systems for many years. In this model, an Owner/Client

procures the services of a Design Consultant to develop the scope of the

project and complete design documents, which are then considered as legal

documents for use in selecting a contractor who builds according to the

specifications developed by the Design Team. Typically, in a public

organization the proposal is in an open competition for a “Low Price”. The

contractor that wins the award is legally bound to produce the project at a

certain price, schedule, and minimum level of standard care. After

completion of the project, the Owner is then responsible for operations and

maintenance of the project. The Owner is also responsible for all the

financing aspects.

Design-Build (DB):

This system heritage is as old as the days during the construction of the

pyramids, when it was referred to with the term Master Builder. Design-Build

is simply a project delivery method in which the Owner/Client selects an

organization that will complete both the design and construction under one

agreement. Upon completion, the Owner is then responsible for operations

and maintenance of the project. The Owner is also responsible for all the

financing aspects.

Design-Build-Operate-Maintain (DBOM):

Design-Build-Operate-Maintain is a project delivery method in which the

Owner/Client selects an organization that will complete the design,

construction, maintenance and an agreed upon period of operational

parameters under one agreement. Upon termination of the operational

period, the Owner is then responsible for operations and maintenance of the

project, unless the operations are continued under a separate procurement

method.

Design-Build/Finance/Operate (DBFO):

Design-Build/Finance/Operate is a project delivery method similar to DBOM,

except that the Contractor is also responsible for the financing of the project.

The contractor assumes the risks of financing until the end of the contract

period. The Owner is then responsible for operations and maintenance of

the asset.

Fully Integrated Clients Services:

“Fully Integrated Clients Services” in this report refers to most, if not all

maintenance activities, that are procured under one contract. In other

words, one contract that includes all the maintenance products and

services.

Lump Sum:

Lump Sum is considered as a fixed price agreement for the total work and

products of a given project. Sometimes this is also referred to as a “Fixed

Price” contract. Any changes to the contract must be agreed upon by both

parties, and they are usually described under “Change Orders”.

Network Area:

A Network Area is defined as a certain geographical area that includes all

the road assets, usually stated in terms of kilometers of roads. It also

includes other assets such as signs, guard rails, etc.

completion of the project, the Owner is then responsible for operations and

maintenance of the project. The Owner is also responsible for all the

financing aspects.

Design-Build (DB):

This system heritage is as old as the days during the construction of the

pyramids, when it was referred to with the term Master Builder. Design-Build

is simply a project delivery method in which the Owner/Client selects an

organization that will complete both the design and construction under one

agreement. Upon completion, the Owner is then responsible for operations

and maintenance of the project. The Owner is also responsible for all the

financing aspects.

Design-Build-Operate-Maintain (DBOM):

Design-Build-Operate-Maintain is a project delivery method in which the

Owner/Client selects an organization that will complete the design,

construction, maintenance and an agreed upon period of operational

parameters under one agreement. Upon termination of the operational

period, the Owner is then responsible for operations and maintenance of the

project, unless the operations are continued under a separate procurement

method.

Design-Build/Finance/Operate (DBFO):

Design-Build/Finance/Operate is a project delivery method similar to DBOM,

except that the Contractor is also responsible for the financing of the project.

The contractor assumes the risks of financing until the end of the contract

period. The Owner is then responsible for operations and maintenance of

the asset.

Fully Integrated Clients Services:

“Fully Integrated Clients Services” in this report refers to most, if not all

maintenance activities, that are procured under one contract. In other

words, one contract that includes all the maintenance products and

services.

Lump Sum:

Lump Sum is considered as a fixed price agreement for the total work and

products of a given project. Sometimes this is also referred to as a “Fixed

Price” contract. Any changes to the contract must be agreed upon by both

parties, and they are usually described under “Change Orders”.

Network Area:

A Network Area is defined as a certain geographical area that includes all

the road assets, usually stated in terms of kilometers of roads. It also

includes other assets such as signs, guard rails, etc.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 122

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.