Design-Build vs. Traditional Procurement: AUT Built Environment Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/13

|21

|8365

|384

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an overview of building procurement methods, focusing on the differences between design-build and traditional procurement systems. It emphasizes the importance of aligning procurement strategies with project objectives and risk management. The report explores various procurement systems, including traditional methods like lump sum, measurement, and cost reimbursement, as well as design and construct procurement and management procurement approaches. It highlights the advantages and disadvantages of each system, offering guidance on when each approach is most suitable. The discussion includes factors influencing procurement strategy, such as independent advice and risk identification, with references to relevant literature and government guidelines. The report concludes by emphasizing the need for a well-defined procurement strategy to achieve successful project outcomes. Desklib provides access to this and other solved assignments for students.

Report

Building Procurement Methods

Research Project No: 2006-034-C-02

The research in this report has been carried out by

Project Leader Peter Davis

Researchers Peter Davis

Peter Love

David Baccarini

Project Affiliates Curtin University of Technology

Western Australia Department of Housing & Work

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology

Research Program: C

Deliver and Management of Built Assets

Project: 2006-034-C

Procurement Method Tookit

Date: June 2008

Building Procurement Methods

Research Project No: 2006-034-C-02

The research in this report has been carried out by

Project Leader Peter Davis

Researchers Peter Davis

Peter Love

David Baccarini

Project Affiliates Curtin University of Technology

Western Australia Department of Housing & Work

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology

Research Program: C

Deliver and Management of Built Assets

Project: 2006-034-C

Procurement Method Tookit

Date: June 2008

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Disclaimer

The Reader makes use of this Report or any information

provided by the Cooperative Research Centre for

Construction Innovation at their own risk.

Construction Innovation will not be responsible for the

results of any actions taken by the Reader or third

parties on the basis of the information in this Report or

other information provided by Construction Innovation

nor for any errors or omissions that may be contained in

this Report. Construction Innovation expressly disclaims

any liability or responsibility to any person in respect of

any thing done or omitted to be done by any person in

reliance on this Report or any information provided.

© 2004 Icon.Net Pty Ltd

To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced

or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of Icon.Net Pty Ltd.

Please direct all enquiries to:

Chief Executive Officer

Cooperative Research Centre for Construction Innovation

9th Floor, L Block, QUT, 2 George St

Brisbane Qld 4000

AUSTRALIA

T: 61 7 3864 1393

F: 61 7 3864 9151

E: enquiries@construction-innovation.info

W: www.construction-innovation.info

The Reader makes use of this Report or any information

provided by the Cooperative Research Centre for

Construction Innovation at their own risk.

Construction Innovation will not be responsible for the

results of any actions taken by the Reader or third

parties on the basis of the information in this Report or

other information provided by Construction Innovation

nor for any errors or omissions that may be contained in

this Report. Construction Innovation expressly disclaims

any liability or responsibility to any person in respect of

any thing done or omitted to be done by any person in

reliance on this Report or any information provided.

© 2004 Icon.Net Pty Ltd

To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced

or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of Icon.Net Pty Ltd.

Please direct all enquiries to:

Chief Executive Officer

Cooperative Research Centre for Construction Innovation

9th Floor, L Block, QUT, 2 George St

Brisbane Qld 4000

AUSTRALIA

T: 61 7 3864 1393

F: 61 7 3864 9151

E: enquiries@construction-innovation.info

W: www.construction-innovation.info

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... i

List of Figures ................................................................................................................ i

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1

1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 2

2. PROCUREMENT STRATEGY ................................................................... 3

2.1 Independent Advice ...........................................................................................4

2.2 Identification of Risk ..........................................................................................4

3. FACTORS INFLUENCING PROCUREMENT STRATEGY ........................... 6

4. PROCUREMENT SYSTEMS ..................................................................... 7

4.1 Traditional Procurement ....................................................................................8

4.1.1 Lump sum ..............................................................................................8

4.1.2 Measurement .........................................................................................9

4.1.3 Cost reimbursement ...............................................................................9

4.1.4 Key points to consider with traditional procurement ............................ 10

4.1.5 Advantages and disadvantages of traditional procurement ................. 10

4.1.6 When should traditional procurement be used? .................................. 10

4.2 Design and Construct Procurement ................................................................ 11

4.2.1 Key points to consider with design and construct

procurement .........................................................................................12

4.2.2 Advantages and disadvantages of design and construct

procurement .........................................................................................13

4.2.3 When should design and construct procurement be used? ................. 13

4.3 Management Procurement ..............................................................................14

4.3.1 Management contracting .....................................................................14

4.3.2 Construction management ...................................................................15

4.3.3 Design and manage .............................................................................15

4.3.4 Advantages and disadvantages of management

procurement .........................................................................................15

4.3.5 Key points to consider with management procurement ....................... 16

5. REFERENCES ....................................................................................... 17

List of Figures

Figure 1 Risk apportionment between client and contractor ............................................ 7

Figure 2 Traditional Procurement Structure ..................................................................... 8

Figure 3 Pre and Post Novation Contracts .................................................................... 11

Figure 4 Construction Management Procurement Arrangements ...............................14

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... i

List of Figures ................................................................................................................ i

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1

1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 2

2. PROCUREMENT STRATEGY ................................................................... 3

2.1 Independent Advice ...........................................................................................4

2.2 Identification of Risk ..........................................................................................4

3. FACTORS INFLUENCING PROCUREMENT STRATEGY ........................... 6

4. PROCUREMENT SYSTEMS ..................................................................... 7

4.1 Traditional Procurement ....................................................................................8

4.1.1 Lump sum ..............................................................................................8

4.1.2 Measurement .........................................................................................9

4.1.3 Cost reimbursement ...............................................................................9

4.1.4 Key points to consider with traditional procurement ............................ 10

4.1.5 Advantages and disadvantages of traditional procurement ................. 10

4.1.6 When should traditional procurement be used? .................................. 10

4.2 Design and Construct Procurement ................................................................ 11

4.2.1 Key points to consider with design and construct

procurement .........................................................................................12

4.2.2 Advantages and disadvantages of design and construct

procurement .........................................................................................13

4.2.3 When should design and construct procurement be used? ................. 13

4.3 Management Procurement ..............................................................................14

4.3.1 Management contracting .....................................................................14

4.3.2 Construction management ...................................................................15

4.3.3 Design and manage .............................................................................15

4.3.4 Advantages and disadvantages of management

procurement .........................................................................................15

4.3.5 Key points to consider with management procurement ....................... 16

5. REFERENCES ....................................................................................... 17

List of Figures

Figure 1 Risk apportionment between client and contractor ............................................ 7

Figure 2 Traditional Procurement Structure ..................................................................... 8

Figure 3 Pre and Post Novation Contracts .................................................................... 11

Figure 4 Construction Management Procurement Arrangements ...............................14

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page | 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A plethora of methods for procuring building projects are available to meet the needs of

clients. Deciding what method to use for a given project is a difficult and challenging task as

a client’s objectives and priorities need to marry with the selected method so as to improve

the likelihood of the project being procured successfully. The decision as to what

procurement system to use should be made as early as possible and underpinned by the

client’s business case for the project. The risks and how they can potentially affect the

client’s business should also be considered.

In this report, the need for client’s to develop a procurement strategy, which outlines the key

means by which the objectives of the project are to be achieved is emphasised. Once a client

has established a business case for a project, appointed a principal advisor, determined their

requirements and brief, then consideration as to which procurement method to be adopted

should be made. An understanding of the characteristics of various procurement options is

required before a recommendation can be made to a client.

Procurement systems can be categorised as traditional, design and construct, management

and collaborative. The characteristics of these systems along with the procurement methods

commonly used are described. The main advantages and disadvantages, and circumstances

under which a system could be considered applicable for a given project are also identified.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A plethora of methods for procuring building projects are available to meet the needs of

clients. Deciding what method to use for a given project is a difficult and challenging task as

a client’s objectives and priorities need to marry with the selected method so as to improve

the likelihood of the project being procured successfully. The decision as to what

procurement system to use should be made as early as possible and underpinned by the

client’s business case for the project. The risks and how they can potentially affect the

client’s business should also be considered.

In this report, the need for client’s to develop a procurement strategy, which outlines the key

means by which the objectives of the project are to be achieved is emphasised. Once a client

has established a business case for a project, appointed a principal advisor, determined their

requirements and brief, then consideration as to which procurement method to be adopted

should be made. An understanding of the characteristics of various procurement options is

required before a recommendation can be made to a client.

Procurement systems can be categorised as traditional, design and construct, management

and collaborative. The characteristics of these systems along with the procurement methods

commonly used are described. The main advantages and disadvantages, and circumstances

under which a system could be considered applicable for a given project are also identified.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page | 2

1. INTRODUCTION

Strategies for the procurement of building projects have not changed significantly in the last

25 years, though time and cost overruns are still prevalent throughout the industry (Smith

and Love, 2001). In a response to reduce the incidence of time and costs overruns, the

disputes that may often arise, and the likelihood of project success, alternative forms of

procurement method such as partnering and alliancing have been advocated (Love et al.

1998). Not all forms of procurement method, however, are appropriate for particular project

types, as client objectives and priorities invariably differ (Skitmore and Marsden, 1988; Love

et al. 1997). The objectives and priorities of a client need to be matched to a procurement

system. To do this effectively, it is essential that the characteristics of various procurement

systems and selection methods available are understood by clients and their advisors before

a procurement method is selected. In this report, the characteristics of the most common

procurement systems and methods are presented. In conjunction with this report the reader

should also refer to the material developed by the New South Wales Government (2005)

‘Procurement Methodology Guidelines for Construction’ and the Western Australian

Department of Housing and Works ‘Local Government Procurement Guide’ (2006).

1. INTRODUCTION

Strategies for the procurement of building projects have not changed significantly in the last

25 years, though time and cost overruns are still prevalent throughout the industry (Smith

and Love, 2001). In a response to reduce the incidence of time and costs overruns, the

disputes that may often arise, and the likelihood of project success, alternative forms of

procurement method such as partnering and alliancing have been advocated (Love et al.

1998). Not all forms of procurement method, however, are appropriate for particular project

types, as client objectives and priorities invariably differ (Skitmore and Marsden, 1988; Love

et al. 1997). The objectives and priorities of a client need to be matched to a procurement

system. To do this effectively, it is essential that the characteristics of various procurement

systems and selection methods available are understood by clients and their advisors before

a procurement method is selected. In this report, the characteristics of the most common

procurement systems and methods are presented. In conjunction with this report the reader

should also refer to the material developed by the New South Wales Government (2005)

‘Procurement Methodology Guidelines for Construction’ and the Western Australian

Department of Housing and Works ‘Local Government Procurement Guide’ (2006).

Page | 3

2. PROCUREMENT STRATEGY

New building or renovation/adaptation of an existing building is necessary only when no

other building exists or appears to exist that will meet or appears to meet the needs of a

client (Turner, 1990). A building project is one way of delivering a solution to the particular

business needs of clients, whether for investment, expansion or improved efficiency. When a

new build solution is selected, rather than renting, leasing or purchasing existing real estate,

there is usually the need for a bespoke solution that aims to meet particular objectives.

Identifying these objectives and prioritising them can be a difficult task considering the array

of stakeholders typically who may be involved within the client organisation (Smith et al.

2001). As a result, adequate consultation and dialogue between stakeholders needs to have

been undertaken before project objectives are prioritised (Smith and Love, 2000).

New build projects are invariably unique one-off designs and built on sites that are also

unique in nature (Turner, 1990). Thus, when considering a strategy to deliver a project, a

client should be made aware of the complex array of activities and processes that are

involved with the procurement process so that they can be appropriately managed (Gordon,

1994). The New South Wales Government (2005) states that the selection of a procurement

methodology essentially involves establishing:

• the most appropriate overall arrangements (or delivery system) for the procurement;

• a contract system for each of the contract or work packages involved as components of

the chosen delivery system; and

• how the procurement will be managed by the agency (or management system), to suit

the delivery system and contract system(s) selected.

A plethora of procurement strategies have been developed to deal with the need to

successfully deliver building projects (e.g., RICS 1996). A procurement strategy outlines the

key means by which the objectives of the project are to be achieved (NSW, 2005). NEDO

(1985) identified seven steps to successful building procurement:

1. Selecting an–house project executive

2. Appointment of a principal adviser

3. Care in deciding the client’s requirements

4. Timing the project realistically

5. Selecting the procurement path

6. Choosing the organisations to work for the client

7. Designating a site or building for remodelling

The NSW Government (2005), for example, have developed a very detailed and

comprehensive procurement strategy, which comprises of ten stages:

1. Identify and quantify a service demand for a genuine delivery need in an outcomes

strategy.

2. Identify service delivery options for meeting the need with stakeholder and preliminary

risk analysis.

3. Justify proposed option with option evaluation, some financial/economic appraisal and

strategy report.

4. Define preferred project with brief, risk/benefits analysis, business case and authority to

proceed.

5. Define/select project procurement strategy with brief, risk/benefits analysis and risk

management plan, initial methodology report and later strategy report.

6. Define project specification with tender documents, estimate and tender evaluation plan

for each contract.

2. PROCUREMENT STRATEGY

New building or renovation/adaptation of an existing building is necessary only when no

other building exists or appears to exist that will meet or appears to meet the needs of a

client (Turner, 1990). A building project is one way of delivering a solution to the particular

business needs of clients, whether for investment, expansion or improved efficiency. When a

new build solution is selected, rather than renting, leasing or purchasing existing real estate,

there is usually the need for a bespoke solution that aims to meet particular objectives.

Identifying these objectives and prioritising them can be a difficult task considering the array

of stakeholders typically who may be involved within the client organisation (Smith et al.

2001). As a result, adequate consultation and dialogue between stakeholders needs to have

been undertaken before project objectives are prioritised (Smith and Love, 2000).

New build projects are invariably unique one-off designs and built on sites that are also

unique in nature (Turner, 1990). Thus, when considering a strategy to deliver a project, a

client should be made aware of the complex array of activities and processes that are

involved with the procurement process so that they can be appropriately managed (Gordon,

1994). The New South Wales Government (2005) states that the selection of a procurement

methodology essentially involves establishing:

• the most appropriate overall arrangements (or delivery system) for the procurement;

• a contract system for each of the contract or work packages involved as components of

the chosen delivery system; and

• how the procurement will be managed by the agency (or management system), to suit

the delivery system and contract system(s) selected.

A plethora of procurement strategies have been developed to deal with the need to

successfully deliver building projects (e.g., RICS 1996). A procurement strategy outlines the

key means by which the objectives of the project are to be achieved (NSW, 2005). NEDO

(1985) identified seven steps to successful building procurement:

1. Selecting an–house project executive

2. Appointment of a principal adviser

3. Care in deciding the client’s requirements

4. Timing the project realistically

5. Selecting the procurement path

6. Choosing the organisations to work for the client

7. Designating a site or building for remodelling

The NSW Government (2005), for example, have developed a very detailed and

comprehensive procurement strategy, which comprises of ten stages:

1. Identify and quantify a service demand for a genuine delivery need in an outcomes

strategy.

2. Identify service delivery options for meeting the need with stakeholder and preliminary

risk analysis.

3. Justify proposed option with option evaluation, some financial/economic appraisal and

strategy report.

4. Define preferred project with brief, risk/benefits analysis, business case and authority to

proceed.

5. Define/select project procurement strategy with brief, risk/benefits analysis and risk

management plan, initial methodology report and later strategy report.

6. Define project specification with tender documents, estimate and tender evaluation plan

for each contract.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page | 4

7. Call/close evaluate tenders for each contract and recommend/approve/engage best

project suppliers.

8. Project implementation with supplier(s) carrying out contract work and asset delivery

9. Asset operation/maintenance and then disposal after supplier(s) completes asset

delivery.

10. Project evaluation during/after delivery comparing outcomes sought and achieved, and

using lessons learnt.

In this report, we are concerned only with the procurement options available. A detailed

review of the techniques that can be used to select a procurement method can be found in

Love et al. (2006) However, selection of the procurement method must integrated with a

procurement methodology that addresses the stages identified by NEDO (1985) and the

NSW Government (2005).

The procurement method chosen in ‘steps 5’ above will influence the degree of integration

and collaboration that will take place between project team members, particularly the

contractor. The greater the integration between project members the more likely a project is

in achieving a successful outcome (Dissanayaka, 1998). Noteworthy, the procurement

method that is chosen for a given project will influence the degree of integration that occurs

between project team members, as this will depend upon the point in time when the

contractor is appointed in the procurement process. The selection of an independent advisor

can assist a client with the identification of risks associated with the procurement process.

2.1 Independent Advice

From the outset of a project clients want to ensure that they can achieve the solution they

require within their established budget and by an acceptable date in the future. This may be

best achieved if the client seeks independent advice on these matters from the outset from

an experienced construction professional, such as a consultant project manager (Love and

Mohamed, 1996). In meeting the needs of the business case, where there is particular focus

on building function or running costs, or speed to completion or capital cost, an experienced

independent project manager can align these needs to an appropriate procurement strategy

(Love and Mohamed, 1996).

2.2 Identification of Risk

The establishment of a procurement strategy that identifies and prioritises key project

objectives as well as reflects aspects of risk, and establishes how the process will be

managed are keys to a successful project outcome (Al-Bahar and Crandall, 1990). The

unique and bespoke nature of building projects means that clients who decide to build are

invariably confronted with high degrees of risk. These risks include completing a project that

does not meet the functional needs of the business, a project that is delivered later than the

initial programme or a project that costs more than the client’s ability to pay or fund. All of

these risks potentially could have an impact on the client’s core business. Consequently, a

procurement strategy should be developed that balances risk against the project objectives

that are established at an early stage.

The nature of the client’s business and the business case for a specific project should be

used to underpin the basic need for certainty in time and cost. The identification of the

factor(s) that will constitute the greatest risk to the business if they fail to be achieved will

assist in the development of a weighted list of priorities and the overall procurement system

to be considered.

The establishment of an appropriate project team to deliver a project at the right time, for the

right cost given the adopted strategy is a vital role for the client, who again should take

independent advice (Morledge et al., 2006). During the selection of the project team, better

outcomes are achieved when ‘value’ is considered over and above the price for the service

that is being offered (Holt et al., 2000). When running costs for the building are deemed

7. Call/close evaluate tenders for each contract and recommend/approve/engage best

project suppliers.

8. Project implementation with supplier(s) carrying out contract work and asset delivery

9. Asset operation/maintenance and then disposal after supplier(s) completes asset

delivery.

10. Project evaluation during/after delivery comparing outcomes sought and achieved, and

using lessons learnt.

In this report, we are concerned only with the procurement options available. A detailed

review of the techniques that can be used to select a procurement method can be found in

Love et al. (2006) However, selection of the procurement method must integrated with a

procurement methodology that addresses the stages identified by NEDO (1985) and the

NSW Government (2005).

The procurement method chosen in ‘steps 5’ above will influence the degree of integration

and collaboration that will take place between project team members, particularly the

contractor. The greater the integration between project members the more likely a project is

in achieving a successful outcome (Dissanayaka, 1998). Noteworthy, the procurement

method that is chosen for a given project will influence the degree of integration that occurs

between project team members, as this will depend upon the point in time when the

contractor is appointed in the procurement process. The selection of an independent advisor

can assist a client with the identification of risks associated with the procurement process.

2.1 Independent Advice

From the outset of a project clients want to ensure that they can achieve the solution they

require within their established budget and by an acceptable date in the future. This may be

best achieved if the client seeks independent advice on these matters from the outset from

an experienced construction professional, such as a consultant project manager (Love and

Mohamed, 1996). In meeting the needs of the business case, where there is particular focus

on building function or running costs, or speed to completion or capital cost, an experienced

independent project manager can align these needs to an appropriate procurement strategy

(Love and Mohamed, 1996).

2.2 Identification of Risk

The establishment of a procurement strategy that identifies and prioritises key project

objectives as well as reflects aspects of risk, and establishes how the process will be

managed are keys to a successful project outcome (Al-Bahar and Crandall, 1990). The

unique and bespoke nature of building projects means that clients who decide to build are

invariably confronted with high degrees of risk. These risks include completing a project that

does not meet the functional needs of the business, a project that is delivered later than the

initial programme or a project that costs more than the client’s ability to pay or fund. All of

these risks potentially could have an impact on the client’s core business. Consequently, a

procurement strategy should be developed that balances risk against the project objectives

that are established at an early stage.

The nature of the client’s business and the business case for a specific project should be

used to underpin the basic need for certainty in time and cost. The identification of the

factor(s) that will constitute the greatest risk to the business if they fail to be achieved will

assist in the development of a weighted list of priorities and the overall procurement system

to be considered.

The establishment of an appropriate project team to deliver a project at the right time, for the

right cost given the adopted strategy is a vital role for the client, who again should take

independent advice (Morledge et al., 2006). During the selection of the project team, better

outcomes are achieved when ‘value’ is considered over and above the price for the service

that is being offered (Holt et al., 2000). When running costs for the building are deemed

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page | 5

important or the design itself is complex or given importance, then procurement methods that

enable a high degree of integration and collaboration between project team members are

deemed to be desirable.

important or the design itself is complex or given importance, then procurement methods that

enable a high degree of integration and collaboration between project team members are

deemed to be desirable.

Page | 6

3. FACTORS INFLUENCING PROCUREMENT STRATEGY

For any given project a client can adopt a collaborative strategy, such as partnering

irrespective of the procurement method used. Such a strategy has been often used by clients

who have series of projects to undertake. The performance of both contractors and

consultants can be monitored using pre-defined indicators for each of the projects they are

involved with and then compared. This approach is particularly useful to monitor and

evaluate disbursement of incentives where appropriate (Morledge et al., 2006). Once the

primary strategy for a project has been established, then the following factors should be

considered when evaluating the most appropriate procurement strategy (Rowlinson, 1999;

Morledge et al. 2006):

• External factors – consideration should be given to the potential impact of economic,

commercial, technological, political, social and legal factors which influence the client and

their business, and the project team during project’s lifecycle. For example, potential

changes in interest rates, changes in legislation and so on.

• Client resources – a client’s knowledge, the experience of the organisation with procuring

building projects and the environment within which it operates will influence the

procurement strategy adopted. Client objectives are influenced by the nature and culture

of the organisation. The degree of client involvement in the project is a major

consideration.

• Project characteristics – The size, complexity, location and uniqueness of the project

should be considered as this will influence time, cost and risk.

• Ability to make changes – Ideally the needs of the client should be identified in the early

stages of the project. This is not always possible. Changes in technology may result in

changes being introduced to a project. Changes in scope invariably result in increase

costs and time, especially they occur during construction. It is important at the outset of

the project to consider the extent to which design can be completed and the possibility of

changes occurring.

• Cost issues – An assessment for the need for price certainty by the client should be

undertaken considering that there is a time delay from the initial estimate to when tenders

are received. The extent to which design is complete will influence the cost at the time of

tender. If price certainty is required, then design must be complete before construction

commences and design changes avoided.

• Timing – Most projects are required within a specific time frame. It is important that an

adequate design time is allowed, particularly if design is required to be complete before

construction. Assurances from the design team about the resources that are available for

the project should be sought. Planning approvals can influence the progress of the

project. If early completion is a critical factor then design and construction activities can

be overlapped so that construction can commence earlier on-site. Time and cost trade

offs should be evaluated.

3. FACTORS INFLUENCING PROCUREMENT STRATEGY

For any given project a client can adopt a collaborative strategy, such as partnering

irrespective of the procurement method used. Such a strategy has been often used by clients

who have series of projects to undertake. The performance of both contractors and

consultants can be monitored using pre-defined indicators for each of the projects they are

involved with and then compared. This approach is particularly useful to monitor and

evaluate disbursement of incentives where appropriate (Morledge et al., 2006). Once the

primary strategy for a project has been established, then the following factors should be

considered when evaluating the most appropriate procurement strategy (Rowlinson, 1999;

Morledge et al. 2006):

• External factors – consideration should be given to the potential impact of economic,

commercial, technological, political, social and legal factors which influence the client and

their business, and the project team during project’s lifecycle. For example, potential

changes in interest rates, changes in legislation and so on.

• Client resources – a client’s knowledge, the experience of the organisation with procuring

building projects and the environment within which it operates will influence the

procurement strategy adopted. Client objectives are influenced by the nature and culture

of the organisation. The degree of client involvement in the project is a major

consideration.

• Project characteristics – The size, complexity, location and uniqueness of the project

should be considered as this will influence time, cost and risk.

• Ability to make changes – Ideally the needs of the client should be identified in the early

stages of the project. This is not always possible. Changes in technology may result in

changes being introduced to a project. Changes in scope invariably result in increase

costs and time, especially they occur during construction. It is important at the outset of

the project to consider the extent to which design can be completed and the possibility of

changes occurring.

• Cost issues – An assessment for the need for price certainty by the client should be

undertaken considering that there is a time delay from the initial estimate to when tenders

are received. The extent to which design is complete will influence the cost at the time of

tender. If price certainty is required, then design must be complete before construction

commences and design changes avoided.

• Timing – Most projects are required within a specific time frame. It is important that an

adequate design time is allowed, particularly if design is required to be complete before

construction. Assurances from the design team about the resources that are available for

the project should be sought. Planning approvals can influence the progress of the

project. If early completion is a critical factor then design and construction activities can

be overlapped so that construction can commence earlier on-site. Time and cost trade

offs should be evaluated.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page | 7

4. PROCUREMENT SYSTEMS

A procurement system (or sometimes known as delivery system) “is an organisational

system that assigns specific responsibilities and authorities to people and organisations, and

defines the various elements in the construction of a project” (Love et al. 1998:p.222).

Procurement systems can be classified as:

• traditional (separated);

• design and construct (integrated);

• management (packaged); and

• collaborative (relational)

Sub-classifications of these systems have tended to proliferate in a response to market

demands. Holt et al. (2000) state that there are so many variables to each of the commonly

adopted procurement strategies, notwithstanding the commonly adopted nomenclature, there

is a very wide range of strategies available. For example, the NSW Government (2005) in

their procurement guidelines identifies more than eight variants of the design and construct

system. However, there are a range of commonly adopted procurement system and contract

methods and each of these is described below.

Collaborative forms such alliancing will not be described in this report as they are typically

used for high complex projects. A detailed description of their characteristics and the

conditions for using such forms of collaborative arrangement can be found in the Victorian

State Government (2006) ‘Project Alliance Practitioners Guide’.

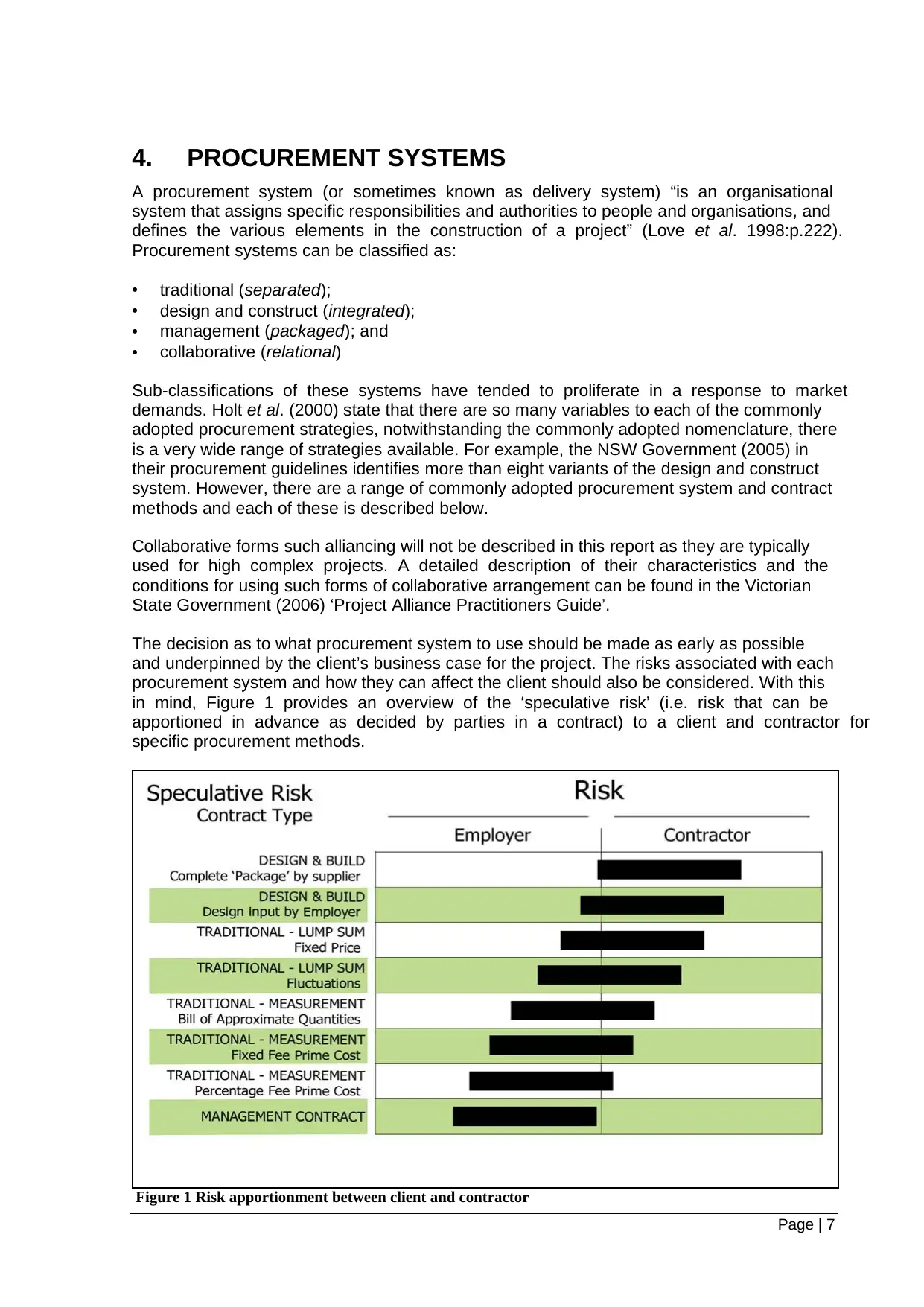

The decision as to what procurement system to use should be made as early as possible

and underpinned by the client’s business case for the project. The risks associated with each

procurement system and how they can affect the client should also be considered. With this

in mind, Figure 1 provides an overview of the ‘speculative risk’ (i.e. risk that can be

apportioned in advance as decided by parties in a contract) to a client and contractor for

specific procurement methods.

Figure 1 Risk apportionment between client and contractor

4. PROCUREMENT SYSTEMS

A procurement system (or sometimes known as delivery system) “is an organisational

system that assigns specific responsibilities and authorities to people and organisations, and

defines the various elements in the construction of a project” (Love et al. 1998:p.222).

Procurement systems can be classified as:

• traditional (separated);

• design and construct (integrated);

• management (packaged); and

• collaborative (relational)

Sub-classifications of these systems have tended to proliferate in a response to market

demands. Holt et al. (2000) state that there are so many variables to each of the commonly

adopted procurement strategies, notwithstanding the commonly adopted nomenclature, there

is a very wide range of strategies available. For example, the NSW Government (2005) in

their procurement guidelines identifies more than eight variants of the design and construct

system. However, there are a range of commonly adopted procurement system and contract

methods and each of these is described below.

Collaborative forms such alliancing will not be described in this report as they are typically

used for high complex projects. A detailed description of their characteristics and the

conditions for using such forms of collaborative arrangement can be found in the Victorian

State Government (2006) ‘Project Alliance Practitioners Guide’.

The decision as to what procurement system to use should be made as early as possible

and underpinned by the client’s business case for the project. The risks associated with each

procurement system and how they can affect the client should also be considered. With this

in mind, Figure 1 provides an overview of the ‘speculative risk’ (i.e. risk that can be

apportioned in advance as decided by parties in a contract) to a client and contractor for

specific procurement methods.

Figure 1 Risk apportionment between client and contractor

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page | 8

In design and construct forms of procurement the contractor predominately assumes the risk

for design and construction of the project. Design and construct variations exist where the

level of design risk can be apportioned more evenly, for example, novation. With traditional

lump sum contracts the intention is that there should usually be a fair and balance of risk

between parties. The balance can be adjusted as required, but the greater the risk to be

assumed by the contractor, the higher the tender figure is likely to be. With management

forms of procurement the balance of risk is most onerous for the client as the contractor is

providing only ‘management expertise’ to a project. However, under a design and manage

method a high of risk can be placed on the contractor for design integration.

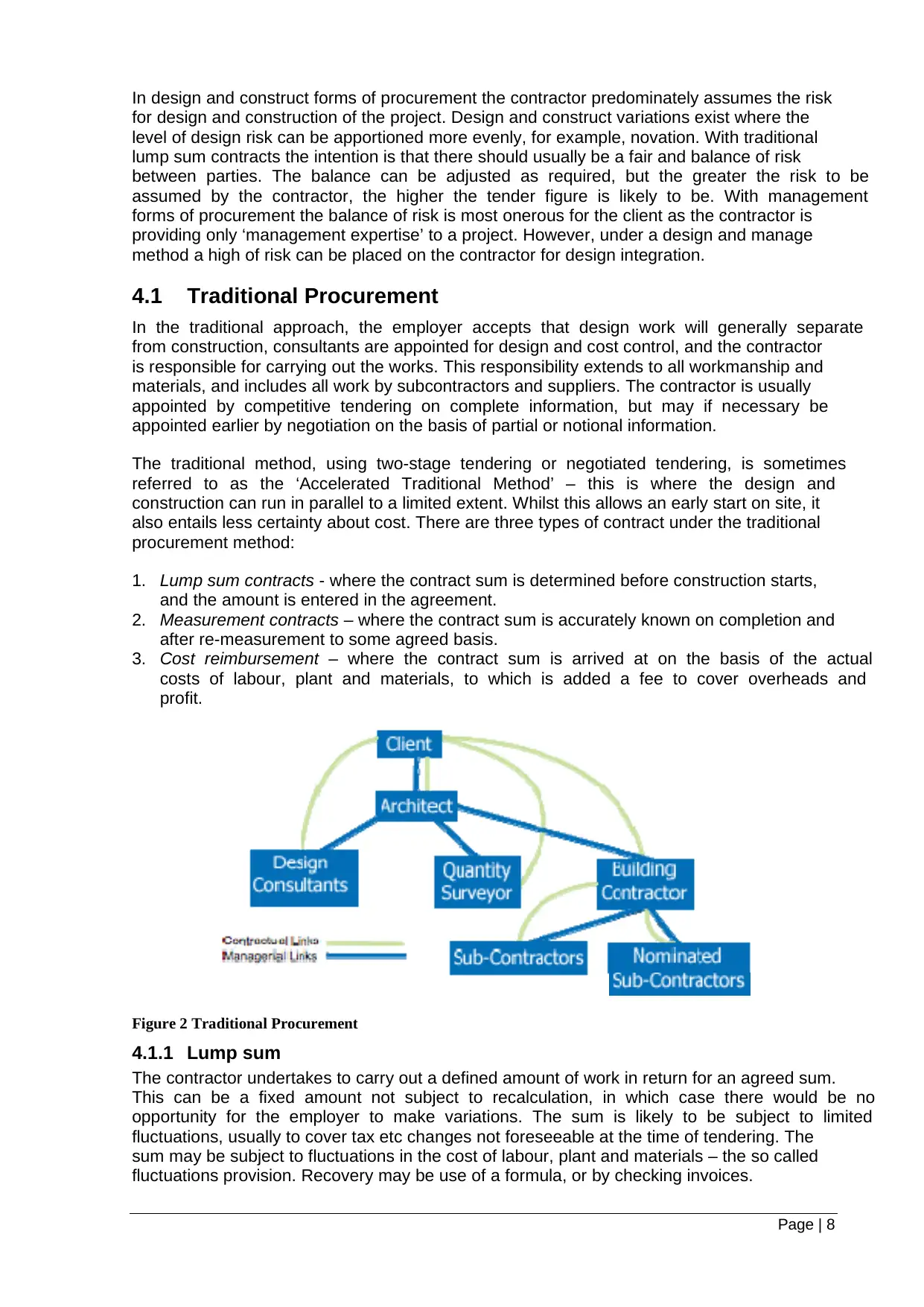

4.1 Traditional Procurement

In the traditional approach, the employer accepts that design work will generally separate

from construction, consultants are appointed for design and cost control, and the contractor

is responsible for carrying out the works. This responsibility extends to all workmanship and

materials, and includes all work by subcontractors and suppliers. The contractor is usually

appointed by competitive tendering on complete information, but may if necessary be

appointed earlier by negotiation on the basis of partial or notional information.

The traditional method, using two-stage tendering or negotiated tendering, is sometimes

referred to as the ‘Accelerated Traditional Method’ – this is where the design and

construction can run in parallel to a limited extent. Whilst this allows an early start on site, it

also entails less certainty about cost. There are three types of contract under the traditional

procurement method:

1. Lump sum contracts - where the contract sum is determined before construction starts,

and the amount is entered in the agreement.

2. Measurement contracts – where the contract sum is accurately known on completion and

after re-measurement to some agreed basis.

3. Cost reimbursement – where the contract sum is arrived at on the basis of the actual

costs of labour, plant and materials, to which is added a fee to cover overheads and

profit.

Figure 2 Traditional Procurement

4.1.1 Lump sum

The contractor undertakes to carry out a defined amount of work in return for an agreed sum.

This can be a fixed amount not subject to recalculation, in which case there would be no

opportunity for the employer to make variations. The sum is likely to be subject to limited

fluctuations, usually to cover tax etc changes not foreseeable at the time of tendering. The

sum may be subject to fluctuations in the cost of labour, plant and materials – the so called

fluctuations provision. Recovery may be use of a formula, or by checking invoices.

In design and construct forms of procurement the contractor predominately assumes the risk

for design and construction of the project. Design and construct variations exist where the

level of design risk can be apportioned more evenly, for example, novation. With traditional

lump sum contracts the intention is that there should usually be a fair and balance of risk

between parties. The balance can be adjusted as required, but the greater the risk to be

assumed by the contractor, the higher the tender figure is likely to be. With management

forms of procurement the balance of risk is most onerous for the client as the contractor is

providing only ‘management expertise’ to a project. However, under a design and manage

method a high of risk can be placed on the contractor for design integration.

4.1 Traditional Procurement

In the traditional approach, the employer accepts that design work will generally separate

from construction, consultants are appointed for design and cost control, and the contractor

is responsible for carrying out the works. This responsibility extends to all workmanship and

materials, and includes all work by subcontractors and suppliers. The contractor is usually

appointed by competitive tendering on complete information, but may if necessary be

appointed earlier by negotiation on the basis of partial or notional information.

The traditional method, using two-stage tendering or negotiated tendering, is sometimes

referred to as the ‘Accelerated Traditional Method’ – this is where the design and

construction can run in parallel to a limited extent. Whilst this allows an early start on site, it

also entails less certainty about cost. There are three types of contract under the traditional

procurement method:

1. Lump sum contracts - where the contract sum is determined before construction starts,

and the amount is entered in the agreement.

2. Measurement contracts – where the contract sum is accurately known on completion and

after re-measurement to some agreed basis.

3. Cost reimbursement – where the contract sum is arrived at on the basis of the actual

costs of labour, plant and materials, to which is added a fee to cover overheads and

profit.

Figure 2 Traditional Procurement

4.1.1 Lump sum

The contractor undertakes to carry out a defined amount of work in return for an agreed sum.

This can be a fixed amount not subject to recalculation, in which case there would be no

opportunity for the employer to make variations. The sum is likely to be subject to limited

fluctuations, usually to cover tax etc changes not foreseeable at the time of tendering. The

sum may be subject to fluctuations in the cost of labour, plant and materials – the so called

fluctuations provision. Recovery may be use of a formula, or by checking invoices.

Page | 9

Lump sum contracts with quantities are priced on the basis of drawings and a firm bill of

quantities. Items which cannot be accurately quantified can be recovered by an approximate

quantity or a provisional sum, but these should be kept to a minimum.

Lump sum contracts ‘without quantities’ are priced on the basis of drawings and another

document. This may simply be a specification of a descriptive kind, in which case the lump

sum will not be itemised, or one that is detailed to the extent that the contract sum is the total

of the priceable items. The job might be more satisfactory described as a ‘Schedule of

Works’, where the lump sum is the total of the priced items. In the latter cases, an itemised

breakdown of the lump sum will be a useful basis for valuing additional work. Where only a

lump sum is tendered, then a supporting ‘Schedule of Rates’ or a ‘Contract Sum Analysis’

will be needed from the tenderer.

Tenders can be prepared on the basis of notional quantities, but they will need to be

replaced by firm quantities if it is intended to enter into a ‘with quantities’ lump sum contract.

4.1.2 Measurement

Measurement contracts are also referred to as ‘re-measurement contracts’. This is where

the work which the contractor undertakes to do cannot for some good reason be accurately

measured before tendering. The presumption is that it has been substantially designed, and

that reasonably accurate picture of the amount and quality of what is required is given to the

tenderer. Probably the most effective measurement contracts, involving least risk is to the

employer, are those based on drawings’ with approximate quantities.

Measurement contracts can also be based on drawings and a ‘Schedule of Rates’ or prices

prepared by the employer for the tenderer to compete. This type of contract might be

appropriate where there is not enough time to prepare even approximate quantities or where

the quantity of work is very uncertain. Obviously the employer has to accept the risk involved

in starting work with no accurate idea of the total cost, and generally this type of contract is

best confined to small jobs.

4.1.3 Cost reimbursement

These are sometimes referred to as ‘Cost Plus’ contracts. The contractor undertakes to carry

out an indeterminate amount of work on the basis that they are paid the prime or actual cost

of labour, plant, and materials. In addition, the contractor receives an agreed fee to cover

management, overheads and profit. Hybrids of the cost reimbursement contracts include:

• Cost-plus percentage fee – the fee charged is directly related to the prime cost. It is

usually a flat rate percentage, but it can also be on a sliding scale. However, the

contractor has no real incentive to work at maximum efficiency, and this variant is only

likely to be considered where the requirements are particularly indeterminate pre-

contract.

• Cost-plus fixed fee – The fee to be charged is tendered by the contractor. This is

appropriate provided that the amount and type of work is largely foreseeable. The

contractor has an incentive to work efficiently so as to remain within the agreed fee.

• Cost-plus fluctuating fee – The fee varies in proportion to the difference between the

estimated cost and the actual prime cost. The assumption is that as the latter cost

increases, the contractor’s supposed inefficiency will result in a fee which decreases.

This approach depends upon there being a realistic chance of ascertaining the amount

and type of work at tender stage.

Lump sum contracts with quantities are priced on the basis of drawings and a firm bill of

quantities. Items which cannot be accurately quantified can be recovered by an approximate

quantity or a provisional sum, but these should be kept to a minimum.

Lump sum contracts ‘without quantities’ are priced on the basis of drawings and another

document. This may simply be a specification of a descriptive kind, in which case the lump

sum will not be itemised, or one that is detailed to the extent that the contract sum is the total

of the priceable items. The job might be more satisfactory described as a ‘Schedule of

Works’, where the lump sum is the total of the priced items. In the latter cases, an itemised

breakdown of the lump sum will be a useful basis for valuing additional work. Where only a

lump sum is tendered, then a supporting ‘Schedule of Rates’ or a ‘Contract Sum Analysis’

will be needed from the tenderer.

Tenders can be prepared on the basis of notional quantities, but they will need to be

replaced by firm quantities if it is intended to enter into a ‘with quantities’ lump sum contract.

4.1.2 Measurement

Measurement contracts are also referred to as ‘re-measurement contracts’. This is where

the work which the contractor undertakes to do cannot for some good reason be accurately

measured before tendering. The presumption is that it has been substantially designed, and

that reasonably accurate picture of the amount and quality of what is required is given to the

tenderer. Probably the most effective measurement contracts, involving least risk is to the

employer, are those based on drawings’ with approximate quantities.

Measurement contracts can also be based on drawings and a ‘Schedule of Rates’ or prices

prepared by the employer for the tenderer to compete. This type of contract might be

appropriate where there is not enough time to prepare even approximate quantities or where

the quantity of work is very uncertain. Obviously the employer has to accept the risk involved

in starting work with no accurate idea of the total cost, and generally this type of contract is

best confined to small jobs.

4.1.3 Cost reimbursement

These are sometimes referred to as ‘Cost Plus’ contracts. The contractor undertakes to carry

out an indeterminate amount of work on the basis that they are paid the prime or actual cost

of labour, plant, and materials. In addition, the contractor receives an agreed fee to cover

management, overheads and profit. Hybrids of the cost reimbursement contracts include:

• Cost-plus percentage fee – the fee charged is directly related to the prime cost. It is

usually a flat rate percentage, but it can also be on a sliding scale. However, the

contractor has no real incentive to work at maximum efficiency, and this variant is only

likely to be considered where the requirements are particularly indeterminate pre-

contract.

• Cost-plus fixed fee – The fee to be charged is tendered by the contractor. This is

appropriate provided that the amount and type of work is largely foreseeable. The

contractor has an incentive to work efficiently so as to remain within the agreed fee.

• Cost-plus fluctuating fee – The fee varies in proportion to the difference between the

estimated cost and the actual prime cost. The assumption is that as the latter cost

increases, the contractor’s supposed inefficiency will result in a fee which decreases.

This approach depends upon there being a realistic chance of ascertaining the amount

and type of work at tender stage.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 21

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.