HLSC122: Report on Designing and Using Research Questionnaires

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|34

|13738

|89

Report

AI Summary

This document provides a detailed overview of designing and using research questionnaires, primarily aimed at novice researchers. It addresses common questions related to questionnaire design, distribution strategies to maximize response rates, and appropriate data analysis techniques. The paper covers various aspects of questionnaire usage in quantitative research, including profiling, descriptive research, predictive analysis, and the development of measurement scales. It emphasizes the importance of aligning questionnaire design with research objectives and respondent characteristics. Furthermore, it differentiates questionnaires from interviews, highlighting the advantages of questionnaires in gathering data from larger samples and their utility in surveying and profiling situations where sufficient prior knowledge exists. The document also touches upon ethical considerations and practical constraints faced by new researchers. Desklib offers a wide array of study tools and resources, including similar assignments and past papers, to aid students in their academic pursuits.

Designing and Using Research Questionnaires

Abstract

Purpose: This article draws on experience in supervising new researchers, and the advice

of other writers to offer novice researchers such as those engaged in study for a thesis, or

in another small-scale research project, a pragmatic introduction to designing and using

research questionnaires.

Design/methodology/approach: After a brief introduction, this article is organized into

three main sections: designing questionnaires, distributing questionnaires, and analysing

and presenting questionnaire data. Within these sections, ten questions often asked by

novice researchers are posed and answered.

Findings: This article is designed to give novice researchers advice and support to help

them to design good questionnaires, to maximise their response rate, and to undertake

appropriate data analysis.

Originality/value: Other research methods texts offer advice on questionnaire design and

use, but their advice is not specifically tailored to new researchers. They tend to offer

options, but provide limited guidance on making crucial decisions in questionnaire

design, distribution and data analysis and presentation.

Keywords: research questionnaires; quantitative research; quantitative data analysis.

Paper type: Conceptual paper

1

Abstract

Purpose: This article draws on experience in supervising new researchers, and the advice

of other writers to offer novice researchers such as those engaged in study for a thesis, or

in another small-scale research project, a pragmatic introduction to designing and using

research questionnaires.

Design/methodology/approach: After a brief introduction, this article is organized into

three main sections: designing questionnaires, distributing questionnaires, and analysing

and presenting questionnaire data. Within these sections, ten questions often asked by

novice researchers are posed and answered.

Findings: This article is designed to give novice researchers advice and support to help

them to design good questionnaires, to maximise their response rate, and to undertake

appropriate data analysis.

Originality/value: Other research methods texts offer advice on questionnaire design and

use, but their advice is not specifically tailored to new researchers. They tend to offer

options, but provide limited guidance on making crucial decisions in questionnaire

design, distribution and data analysis and presentation.

Keywords: research questionnaires; quantitative research; quantitative data analysis.

Paper type: Conceptual paper

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1. Introduction

Questionnaires are one of the most widely used means of collecting data, and therefore

many novice researchers in business and management and other areas of the social

sciences associate research with questionnaires. Given their prevalence, it is to easy to

assume that questionnaires are easy to design and use; this is not the case – a lot of effort

goes into creating a good questionnaire that collects the data that answers your research

questions and attracts a sufficient response rate. In this article, we use the term research

questionnaire to refer to questionnaires that are used as part of an academic research

project. Others (e.g. Bryman and Bell, 2011) use the term self-completion questionnaire,

or the related terms self-administered questionnaire or postal or mail questionnaire.

Further, we use the term questionnaire to refer to documents that include a series of open

and closed questions to which the respondent is invited to provide answers. Research

questionnaires may be distributed to the potential respondents by post, e-mail, as an

online questionnaire, or face-to-face by hand. Interviews, especially structured and semi-

structured interviews, also ask questions that the respondent is invited to answer, but the

essential distinguishing characteristic of questionnaires is that they are normally designed

to be completed without any direct interaction with the researcher, either in person or

remotely. However, the boundary between questionnaires and interviews is fuzzy, since

they are both question answering research instruments, with unstructured interviews at

one end of a spectrum and questionnaires comprised of predominantly closed questions at

the other end. Respondents to a questionnaire may be asked to answer questions

regarding facts (e.g. their age or salary), or their attitudes, beliefs, behaviours or

experiences as a citizen, manager, professional, user, consumer or employee. Since one

of the main advantages of questionnaires is the ability to make contact with and gather

responses from a relatively large number of people in scattered and possibly remote

locations, questionnaires are typically used in surveys, where the objective is to profile a

‘population’. This leads to consideration of who to include in the survey, or the sample.

In research in organizational studies, management, and business, participants may be

selected either as an individual or as a representative of their team, organization, or

industry.

2

Questionnaires are one of the most widely used means of collecting data, and therefore

many novice researchers in business and management and other areas of the social

sciences associate research with questionnaires. Given their prevalence, it is to easy to

assume that questionnaires are easy to design and use; this is not the case – a lot of effort

goes into creating a good questionnaire that collects the data that answers your research

questions and attracts a sufficient response rate. In this article, we use the term research

questionnaire to refer to questionnaires that are used as part of an academic research

project. Others (e.g. Bryman and Bell, 2011) use the term self-completion questionnaire,

or the related terms self-administered questionnaire or postal or mail questionnaire.

Further, we use the term questionnaire to refer to documents that include a series of open

and closed questions to which the respondent is invited to provide answers. Research

questionnaires may be distributed to the potential respondents by post, e-mail, as an

online questionnaire, or face-to-face by hand. Interviews, especially structured and semi-

structured interviews, also ask questions that the respondent is invited to answer, but the

essential distinguishing characteristic of questionnaires is that they are normally designed

to be completed without any direct interaction with the researcher, either in person or

remotely. However, the boundary between questionnaires and interviews is fuzzy, since

they are both question answering research instruments, with unstructured interviews at

one end of a spectrum and questionnaires comprised of predominantly closed questions at

the other end. Respondents to a questionnaire may be asked to answer questions

regarding facts (e.g. their age or salary), or their attitudes, beliefs, behaviours or

experiences as a citizen, manager, professional, user, consumer or employee. Since one

of the main advantages of questionnaires is the ability to make contact with and gather

responses from a relatively large number of people in scattered and possibly remote

locations, questionnaires are typically used in surveys, where the objective is to profile a

‘population’. This leads to consideration of who to include in the survey, or the sample.

In research in organizational studies, management, and business, participants may be

selected either as an individual or as a representative of their team, organization, or

industry.

2

If you are new to research, and possibly engaging in research to complete a thesis or

other small-scale project, and are planning to use questionnaires as a research method,

this article is written for you. It helps you to think about the decisions that you need to

make in designing questionnaires, distributing the questionnaires is such a way as to get a

good response rate, and analysing and presenting the data. This article seeks to provide

answers to some of the questions that new researchers frequently ask. Whilst its emphasis

is on helping you to do rigorous research and to succeed and maybe even excel, it is also

pragmatic in recognizing the time and other constraints often experienced by new

researchers.

There are many other sources of advice on designing and using research questionnaires

that you could also consult. First, there are many research methods textbooks that offer a

basic grounding in research methods (e.g. Bryman and Bell, 2011; Collis and Hussey,

2009; Cresswell, 2008; Denscombe, 2010; Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Jackson, 2012;

Lee and Lings, 2008; Saunders, Thornhill and Lewis, 2012); since these books have a

wide scope, they only provide limited information on questionnaires as a data collection

method. Interestingly, there are only a few texts that deal specifically with quantitative

methods (e.g. Oakshott, 2009; Swift and Piff, 2010). Finally, there are a few texts

devoted specifically to questionnaires and/or surveys; amongst these Oppenheim (1992)

is regarded as a classic, whilst Gillham (2007), Sue and Pitter (2012) and Fowler (2008)

are also useful guides. Useful as these are, they can be a little daunting for the novice

researcher who is seeking a relatively quick and pragmatic approach to designing

questionnaires and analyzing their data. As with all research methods, learning how to

work with questionnaires is an iterative process, in which initial guidance allows the

researcher to get started, experience and reflection hones their art, and further advice

helps the researcher to develop their research skills yet further.

This article starts with discussion of a number of questions that are associated with the

design and planning of the questionnaire, and then moves on to consider aspects of the

questionnaire distribution and sampling, and finally, concludes with some thoughts on

making sense of the data and presenting it in a findings chapter.

3

other small-scale project, and are planning to use questionnaires as a research method,

this article is written for you. It helps you to think about the decisions that you need to

make in designing questionnaires, distributing the questionnaires is such a way as to get a

good response rate, and analysing and presenting the data. This article seeks to provide

answers to some of the questions that new researchers frequently ask. Whilst its emphasis

is on helping you to do rigorous research and to succeed and maybe even excel, it is also

pragmatic in recognizing the time and other constraints often experienced by new

researchers.

There are many other sources of advice on designing and using research questionnaires

that you could also consult. First, there are many research methods textbooks that offer a

basic grounding in research methods (e.g. Bryman and Bell, 2011; Collis and Hussey,

2009; Cresswell, 2008; Denscombe, 2010; Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Jackson, 2012;

Lee and Lings, 2008; Saunders, Thornhill and Lewis, 2012); since these books have a

wide scope, they only provide limited information on questionnaires as a data collection

method. Interestingly, there are only a few texts that deal specifically with quantitative

methods (e.g. Oakshott, 2009; Swift and Piff, 2010). Finally, there are a few texts

devoted specifically to questionnaires and/or surveys; amongst these Oppenheim (1992)

is regarded as a classic, whilst Gillham (2007), Sue and Pitter (2012) and Fowler (2008)

are also useful guides. Useful as these are, they can be a little daunting for the novice

researcher who is seeking a relatively quick and pragmatic approach to designing

questionnaires and analyzing their data. As with all research methods, learning how to

work with questionnaires is an iterative process, in which initial guidance allows the

researcher to get started, experience and reflection hones their art, and further advice

helps the researcher to develop their research skills yet further.

This article starts with discussion of a number of questions that are associated with the

design and planning of the questionnaire, and then moves on to consider aspects of the

questionnaire distribution and sampling, and finally, concludes with some thoughts on

making sense of the data and presenting it in a findings chapter.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

2. Designing questionnaires

Q1. Why should I choose questionnaires for my research?

Questionnaires are mostly used in conducting quantitative research, where the researcher

wants to profile the sample in terms of numbers (e.g. the proportion of the sample in

different age groups) or to be able to count the frequency of occurrence of opinions,

attitudes, experiences, processes, behaviours, or predictions. For example, questionnaires

could be distributed to members of a social network site in order to ascertain the reasons

for their membership of the site, and the benefits that they perceive themselves to derive

from membership of the site. The questionnaire might include questions relating to any of

the standard topics included in questionnaires:

• ‘facts’, such as their age or occupation

• opinions, attitudes, beliefs and judgments, such as opinions on the benefits of the site,

attitudes towards various features or functions of the site, and perceptions of the

usability of the site

• behaviour, such as how frequently they visited the site.

Questionnaires are typically used in survey situations, where the purpose is to collect data

from a relatively large number of people (say between 100 and 1000). Often, but not

always, the people from whom responses are collected are a sample drawn from a wider

population, and are chosen to ‘represent’ the wider population. So, for example, if we

wanted to compare the leadership styles adopted by CEO’s in technology companies with

those of CEO’s in retail organizations in the UK, we are unlikely to be able to collect a

completed questionnaire from every CEO in these two sectors. So, we would need to

make a decision as to how many responses from CEO’s of what types of organizations

we would regard as sufficient, and select a sample accordingly.

Although there are many different approaches to collecting data with which

questionnaires can be compared, a common consideration for novice researchers is

whether to choose between questionnaires or interviews. The big advantage of

questionnaires is that it is easier to get responses from a large number of people, and the

4

Q1. Why should I choose questionnaires for my research?

Questionnaires are mostly used in conducting quantitative research, where the researcher

wants to profile the sample in terms of numbers (e.g. the proportion of the sample in

different age groups) or to be able to count the frequency of occurrence of opinions,

attitudes, experiences, processes, behaviours, or predictions. For example, questionnaires

could be distributed to members of a social network site in order to ascertain the reasons

for their membership of the site, and the benefits that they perceive themselves to derive

from membership of the site. The questionnaire might include questions relating to any of

the standard topics included in questionnaires:

• ‘facts’, such as their age or occupation

• opinions, attitudes, beliefs and judgments, such as opinions on the benefits of the site,

attitudes towards various features or functions of the site, and perceptions of the

usability of the site

• behaviour, such as how frequently they visited the site.

Questionnaires are typically used in survey situations, where the purpose is to collect data

from a relatively large number of people (say between 100 and 1000). Often, but not

always, the people from whom responses are collected are a sample drawn from a wider

population, and are chosen to ‘represent’ the wider population. So, for example, if we

wanted to compare the leadership styles adopted by CEO’s in technology companies with

those of CEO’s in retail organizations in the UK, we are unlikely to be able to collect a

completed questionnaire from every CEO in these two sectors. So, we would need to

make a decision as to how many responses from CEO’s of what types of organizations

we would regard as sufficient, and select a sample accordingly.

Although there are many different approaches to collecting data with which

questionnaires can be compared, a common consideration for novice researchers is

whether to choose between questionnaires or interviews. The big advantage of

questionnaires is that it is easier to get responses from a large number of people, and the

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

data gathered may therefore be seen to generate findings that are more generalisable. For

example, if, say 400 students were surveyed on the factors that affected their choice of

mobile phone service provider, then this study would have the potential to be

generalisable to other members of the same student population. If, on the other hand,

instead of using questionnaires, the researcher had opted to conduct interviews, time

constraints would dictate that they collect data from rather fewer students, say, twenty.

With responses from only twenty students, we would feel a lot less confident that the data

collected would support generalization to the rest of the specific student population. On

the other hand, they may have potential to generate a range of insights and

understandings that might be useful, to say, mobile service providers. In general,

interviews are preferable to questionnaires when it is possible to identify people who are

in key positions to understand a situation, such as, say, the managers responsible for

implementing a corporate social responsibility policy in a specific brand of a retail chain.

In summary then, questionnaires are useful when:

• The research objectives centre on surveying and profiling a situation, to develop

overall patterns

• Sufficient is already known about the situation under study that it is possible to

formulate meaningful questions to include in the questionnaire.

• Willing respondents can be identified, who are in a position to provide

meaningful data about a topic. Questionnaires should not only suit the research

and the researcher, but also the respondents.

Q2. What types of research can be conducted through a questionnaire?

Surveys and questionnaires are employed to conduct a variety of different kinds of

research, key amongst which are:

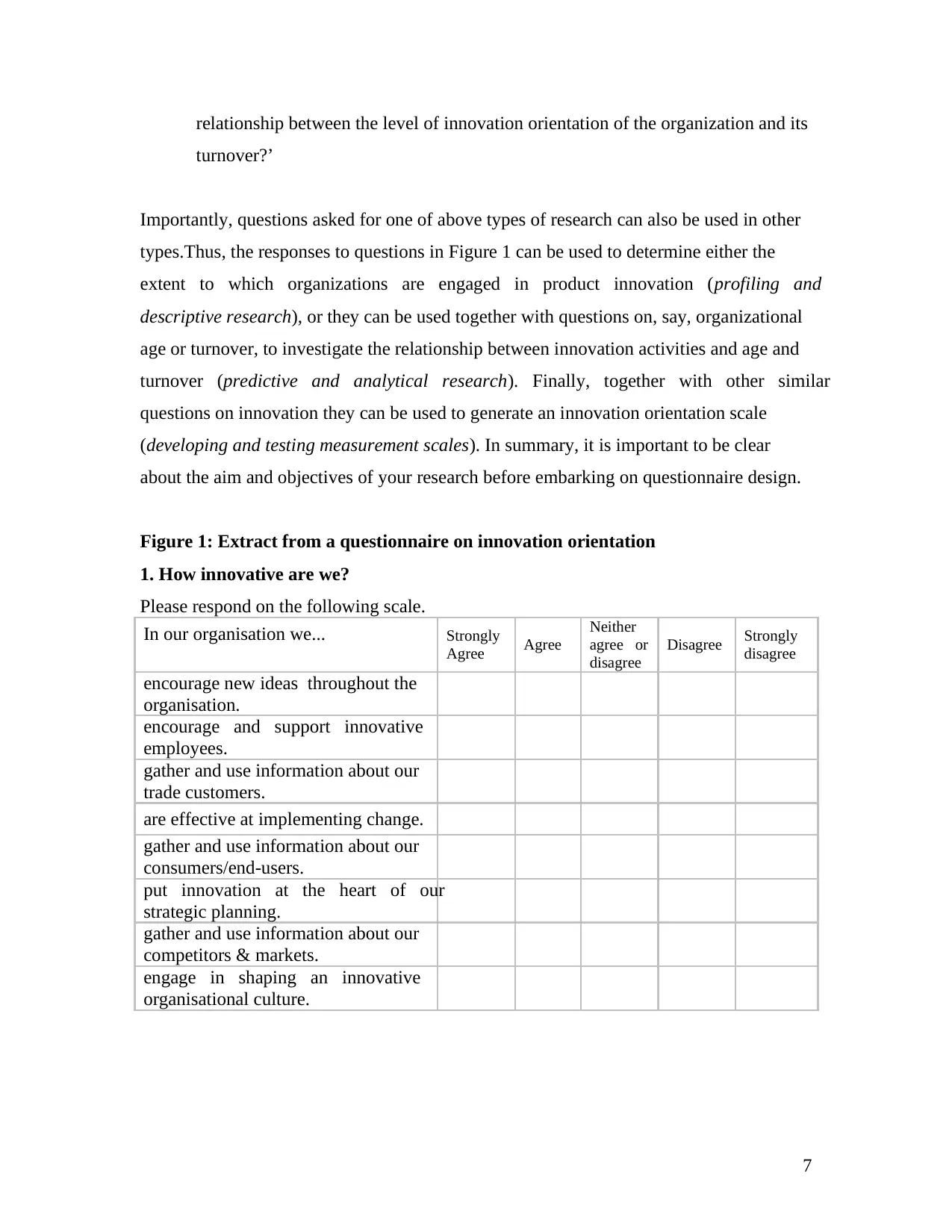

1. Profiling and descriptive research, where the purpose is to generate a profile of

the characteristics of the sample. For example, in examining innovation in a

groups of SME’s in the food sector, questions might be posed to identify the level

of engagement with different innovation activities (Figure 1). Such research

5

example, if, say 400 students were surveyed on the factors that affected their choice of

mobile phone service provider, then this study would have the potential to be

generalisable to other members of the same student population. If, on the other hand,

instead of using questionnaires, the researcher had opted to conduct interviews, time

constraints would dictate that they collect data from rather fewer students, say, twenty.

With responses from only twenty students, we would feel a lot less confident that the data

collected would support generalization to the rest of the specific student population. On

the other hand, they may have potential to generate a range of insights and

understandings that might be useful, to say, mobile service providers. In general,

interviews are preferable to questionnaires when it is possible to identify people who are

in key positions to understand a situation, such as, say, the managers responsible for

implementing a corporate social responsibility policy in a specific brand of a retail chain.

In summary then, questionnaires are useful when:

• The research objectives centre on surveying and profiling a situation, to develop

overall patterns

• Sufficient is already known about the situation under study that it is possible to

formulate meaningful questions to include in the questionnaire.

• Willing respondents can be identified, who are in a position to provide

meaningful data about a topic. Questionnaires should not only suit the research

and the researcher, but also the respondents.

Q2. What types of research can be conducted through a questionnaire?

Surveys and questionnaires are employed to conduct a variety of different kinds of

research, key amongst which are:

1. Profiling and descriptive research, where the purpose is to generate a profile of

the characteristics of the sample. For example, in examining innovation in a

groups of SME’s in the food sector, questions might be posed to identify the level

of engagement with different innovation activities (Figure 1). Such research

5

answers questions such as what do they do, what do they think, and, what are their

characteristics (e.g organizational age).

2. Predictive and analytical research, where the purpose is to understand any

relationships between variables. We might be interested in the relationship

between the number of hours exercise that a manager takes a week and their BMI.

Provided we have asked the respondents for information on these two variables,

and we have a sufficiently large data set, we can look for patterns, using

techniques like correlation, regression, or chi-squared tests, to investigate the

relationship between these two variables. For example, does BMI go down as the

number of hours exercise a week goes up? More advanced techniques such as

multiple regression and structured equation modeling allow exploration of the

relationships between several variables at one time. Once research has established

relationships between variables it may be possible to offer some predictions as to

future events or patterns of behaviour.

3. Developing and testing measurement scales, where the purpose is to generate a

measurement scale, or a set of statements to measure a complex variable, such as

service quality, trust, or innovation orientation. Creating a measure such as the

number of years experience a person has in their current role, or the turnover for a

business in the previous financial year, is relatively straightforward. However,

measuring and hence asking questions that ‘measure’, for example, the

innovativeness of an organization, or the extent of formalization of its strategic

planning processes is much more complex. Accordingly, researchers develop

measurement scales, comprising of a number of statements that can be used to

measure the variable. Typically, they initially propose such statements based on

previous research, and then test and refine the scale using data collected from

appropriate respondents, with the aid of analytical methods such as exploratory,

principal components or confirmatory factor analysis. Only when they have such

measures of complex variables, can they ask questions such as ‘Is there any

6

characteristics (e.g organizational age).

2. Predictive and analytical research, where the purpose is to understand any

relationships between variables. We might be interested in the relationship

between the number of hours exercise that a manager takes a week and their BMI.

Provided we have asked the respondents for information on these two variables,

and we have a sufficiently large data set, we can look for patterns, using

techniques like correlation, regression, or chi-squared tests, to investigate the

relationship between these two variables. For example, does BMI go down as the

number of hours exercise a week goes up? More advanced techniques such as

multiple regression and structured equation modeling allow exploration of the

relationships between several variables at one time. Once research has established

relationships between variables it may be possible to offer some predictions as to

future events or patterns of behaviour.

3. Developing and testing measurement scales, where the purpose is to generate a

measurement scale, or a set of statements to measure a complex variable, such as

service quality, trust, or innovation orientation. Creating a measure such as the

number of years experience a person has in their current role, or the turnover for a

business in the previous financial year, is relatively straightforward. However,

measuring and hence asking questions that ‘measure’, for example, the

innovativeness of an organization, or the extent of formalization of its strategic

planning processes is much more complex. Accordingly, researchers develop

measurement scales, comprising of a number of statements that can be used to

measure the variable. Typically, they initially propose such statements based on

previous research, and then test and refine the scale using data collected from

appropriate respondents, with the aid of analytical methods such as exploratory,

principal components or confirmatory factor analysis. Only when they have such

measures of complex variables, can they ask questions such as ‘Is there any

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

relationship between the level of innovation orientation of the organization and its

turnover?’

Importantly, questions asked for one of above types of research can also be used in other

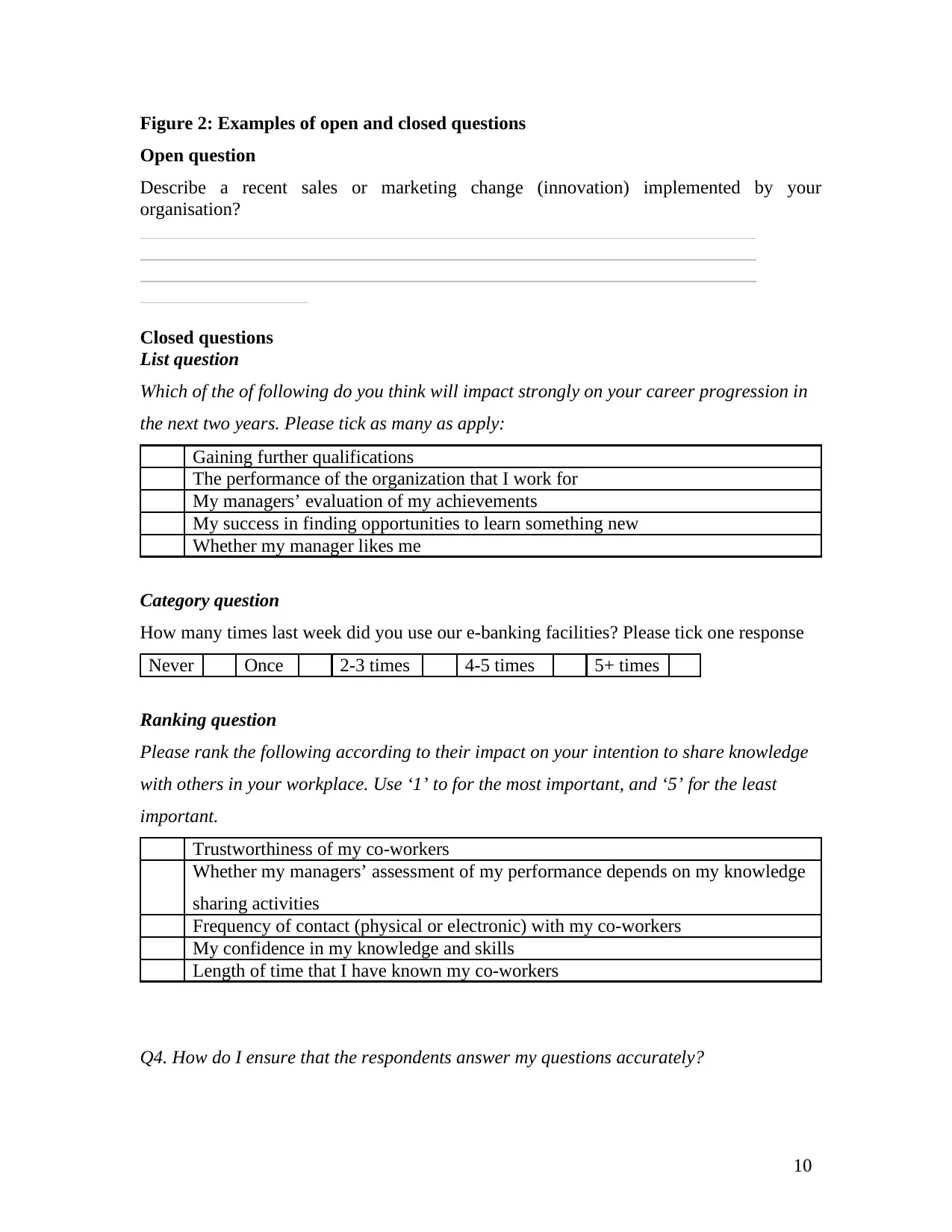

types.Thus, the responses to questions in Figure 1 can be used to determine either the

extent to which organizations are engaged in product innovation (profiling and

descriptive research), or they can be used together with questions on, say, organizational

age or turnover, to investigate the relationship between innovation activities and age and

turnover (predictive and analytical research). Finally, together with other similar

questions on innovation they can be used to generate an innovation orientation scale

(developing and testing measurement scales). In summary, it is important to be clear

about the aim and objectives of your research before embarking on questionnaire design.

Figure 1: Extract from a questionnaire on innovation orientation

1. How innovative are we?

Please respond on the following scale.

In our organisation we... Strongly

Agree Agree

Neither

agree or

disagree

Disagree Strongly

disagree

encourage new ideas throughout the

organisation.

encourage and support innovative

employees.

gather and use information about our

trade customers.

are effective at implementing change.

gather and use information about our

consumers/end-users.

put innovation at the heart of our

strategic planning.

gather and use information about our

competitors & markets.

engage in shaping an innovative

organisational culture.

7

turnover?’

Importantly, questions asked for one of above types of research can also be used in other

types.Thus, the responses to questions in Figure 1 can be used to determine either the

extent to which organizations are engaged in product innovation (profiling and

descriptive research), or they can be used together with questions on, say, organizational

age or turnover, to investigate the relationship between innovation activities and age and

turnover (predictive and analytical research). Finally, together with other similar

questions on innovation they can be used to generate an innovation orientation scale

(developing and testing measurement scales). In summary, it is important to be clear

about the aim and objectives of your research before embarking on questionnaire design.

Figure 1: Extract from a questionnaire on innovation orientation

1. How innovative are we?

Please respond on the following scale.

In our organisation we... Strongly

Agree Agree

Neither

agree or

disagree

Disagree Strongly

disagree

encourage new ideas throughout the

organisation.

encourage and support innovative

employees.

gather and use information about our

trade customers.

are effective at implementing change.

gather and use information about our

consumers/end-users.

put innovation at the heart of our

strategic planning.

gather and use information about our

competitors & markets.

engage in shaping an innovative

organisational culture.

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Q3. How do I decide the questions to ask?

It goes without saying that the questions in the questionnaire are designed to generate

data that is intended to answer your research questions. On the other hand, the questions

often do not exactly match your research questions. First, and foremost it is important

that questions use language that respondents understand – whereas your research

questions may use more ‘academic’ or specialized technical language. Secondly, you

may for instance be interested in the relationship between two variables, such as in the

example above, the relationship between the manager’s BMI and their exercise regime.

The questionnaire is unlikely to ask this question directly (unless the aim is to explore

people’s opinions on the relationship). Rather, the questionnaire may ask about BMI and

exercise regime, separately, thereby collecting data that can be analysed to investigate the

relationship.

Both research and questionnaire questions can be informed by practice or experience, or

by theory or previous research, or, as is common with research in practitioner disciplines,

a mix of both. Research that is informed by previous theory and research is described as

deductive. With deductive research, theory is a significant factor in determining the

research questions, and indeed, it may be possible and even advisable to use part or all of

a previous questionnaire from a published article on a similar topic. Provided that you

acknowledge your sources, and the questions are adapted to your specific research

question, this is not cheating; you are using questions that have already been ‘piloted’ and

making it easier to compare your research with previous research and to make a clear

claim about what is new in your findings (Bryman and Bell, 2011). Indeed, there are

many instances in which replication, conducting a similar study to one that was

conducted earlier but in a different context, can be a valuable addition to knowledge.

Since the design of a questionnaire calls for some prior knowledge, deductive research is

more common in research using questionnaires, than the alternative approach, inductive

research, where the researcher deduces theory from the data that they have gathered.

When framing and designing your questions it is useful to think about the type of

question that is suitable for a specific context. The first, and most significant

8

It goes without saying that the questions in the questionnaire are designed to generate

data that is intended to answer your research questions. On the other hand, the questions

often do not exactly match your research questions. First, and foremost it is important

that questions use language that respondents understand – whereas your research

questions may use more ‘academic’ or specialized technical language. Secondly, you

may for instance be interested in the relationship between two variables, such as in the

example above, the relationship between the manager’s BMI and their exercise regime.

The questionnaire is unlikely to ask this question directly (unless the aim is to explore

people’s opinions on the relationship). Rather, the questionnaire may ask about BMI and

exercise regime, separately, thereby collecting data that can be analysed to investigate the

relationship.

Both research and questionnaire questions can be informed by practice or experience, or

by theory or previous research, or, as is common with research in practitioner disciplines,

a mix of both. Research that is informed by previous theory and research is described as

deductive. With deductive research, theory is a significant factor in determining the

research questions, and indeed, it may be possible and even advisable to use part or all of

a previous questionnaire from a published article on a similar topic. Provided that you

acknowledge your sources, and the questions are adapted to your specific research

question, this is not cheating; you are using questions that have already been ‘piloted’ and

making it easier to compare your research with previous research and to make a clear

claim about what is new in your findings (Bryman and Bell, 2011). Indeed, there are

many instances in which replication, conducting a similar study to one that was

conducted earlier but in a different context, can be a valuable addition to knowledge.

Since the design of a questionnaire calls for some prior knowledge, deductive research is

more common in research using questionnaires, than the alternative approach, inductive

research, where the researcher deduces theory from the data that they have gathered.

When framing and designing your questions it is useful to think about the type of

question that is suitable for a specific context. The first, and most significant

8

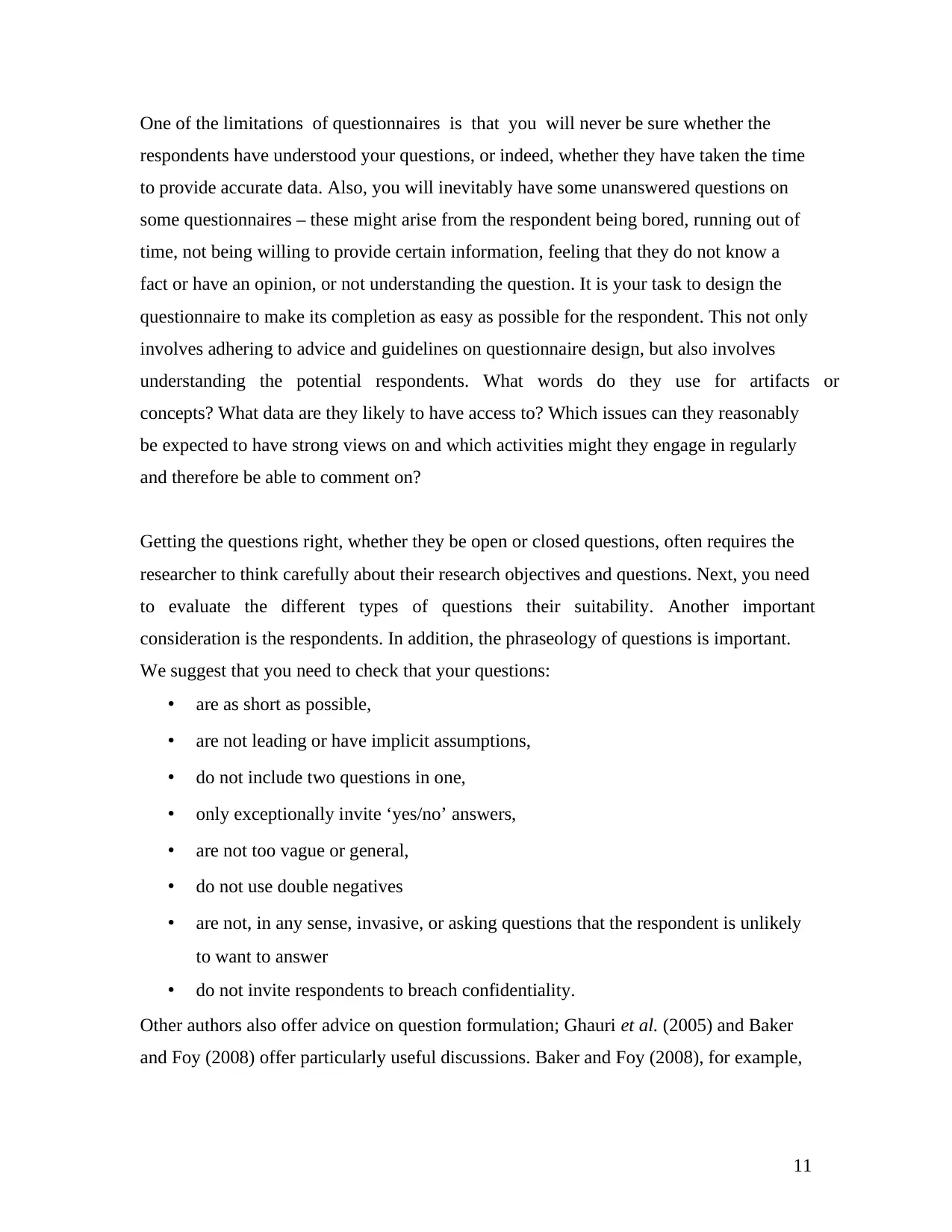

categorization of questions, is into open and closed questions. Figure 1 gives examples of

closed questions, in this case, Likert scale questions, where respondents are asked to

indicate how strongly they agree or disagree with a series of statements. Other types of

scale questions can also be used, including different number of options (e.g. 7-point

rather than 5-point), and continuum scales with opposgin words or concepts at opposite

ends of a numerical spectrum. Figure 2 gives an example of an open question and of

other types of closed questions; many questionnaires make use of a combination of open

and closed questions. Closed questions are always accompanied by a number of options

from which to select. Open questions simply invite respondents to provide data (e.g. team

size, name of organization) or offer short comments (typically between one and three

sentences). Closed questions are more difficult to design, because the researcher needs to

know sufficient about the respondent population to be able to offer sensible categories for

each closed question. For example, even what appears to be a simple type of closed

question, one asking about the age of someone, needs to take into consideration the

respondents and the research question. For example, in our study of the health and fitness

regimes of managers, if the researcher is planning to distribute the questionnaires to full-

time MBA students, then the specified age categories will be different to those if the

questionnaires were to be distributed to senior managers in businesses in a specific sector.

In addition, there are a number of different types of closed questions, each of which suits

different research objectives, and may need a different types of analysis. For further

explanation of types of questions see Gray (2009) and Ghauri et al., (2005), for an

introductory account, and Oppenheim (1992) for a more complex account.

Closed questions are quick for respondents (which may increase response rate), and the

responses to closed questions are easier to code and analyse, which is particularly

important if the number of questionnaires collected is quite large. Open questions are

useful for collecting more in-depth insights, and allow respondents to use their own

language and express their own views. However, since they are more time consuming to

complete and to analyse, they should only be used when they are the best option.

9

closed questions, in this case, Likert scale questions, where respondents are asked to

indicate how strongly they agree or disagree with a series of statements. Other types of

scale questions can also be used, including different number of options (e.g. 7-point

rather than 5-point), and continuum scales with opposgin words or concepts at opposite

ends of a numerical spectrum. Figure 2 gives an example of an open question and of

other types of closed questions; many questionnaires make use of a combination of open

and closed questions. Closed questions are always accompanied by a number of options

from which to select. Open questions simply invite respondents to provide data (e.g. team

size, name of organization) or offer short comments (typically between one and three

sentences). Closed questions are more difficult to design, because the researcher needs to

know sufficient about the respondent population to be able to offer sensible categories for

each closed question. For example, even what appears to be a simple type of closed

question, one asking about the age of someone, needs to take into consideration the

respondents and the research question. For example, in our study of the health and fitness

regimes of managers, if the researcher is planning to distribute the questionnaires to full-

time MBA students, then the specified age categories will be different to those if the

questionnaires were to be distributed to senior managers in businesses in a specific sector.

In addition, there are a number of different types of closed questions, each of which suits

different research objectives, and may need a different types of analysis. For further

explanation of types of questions see Gray (2009) and Ghauri et al., (2005), for an

introductory account, and Oppenheim (1992) for a more complex account.

Closed questions are quick for respondents (which may increase response rate), and the

responses to closed questions are easier to code and analyse, which is particularly

important if the number of questionnaires collected is quite large. Open questions are

useful for collecting more in-depth insights, and allow respondents to use their own

language and express their own views. However, since they are more time consuming to

complete and to analyse, they should only be used when they are the best option.

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure 2: Examples of open and closed questions

Open question

Describe a recent sales or marketing change (innovation) implemented by your

organisation?

Closed questions

List question

Which of the of following do you think will impact strongly on your career progression in

the next two years. Please tick as many as apply:

Gaining further qualifications

The performance of the organization that I work for

My managers’ evaluation of my achievements

My success in finding opportunities to learn something new

Whether my manager likes me

Category question

How many times last week did you use our e-banking facilities? Please tick one response

Never Once 2-3 times 4-5 times 5+ times

Ranking question

Please rank the following according to their impact on your intention to share knowledge

with others in your workplace. Use ‘1’ to for the most important, and ‘5’ for the least

important.

Trustworthiness of my co-workers

Whether my managers’ assessment of my performance depends on my knowledge

sharing activities

Frequency of contact (physical or electronic) with my co-workers

My confidence in my knowledge and skills

Length of time that I have known my co-workers

Q4. How do I ensure that the respondents answer my questions accurately?

10

Open question

Describe a recent sales or marketing change (innovation) implemented by your

organisation?

Closed questions

List question

Which of the of following do you think will impact strongly on your career progression in

the next two years. Please tick as many as apply:

Gaining further qualifications

The performance of the organization that I work for

My managers’ evaluation of my achievements

My success in finding opportunities to learn something new

Whether my manager likes me

Category question

How many times last week did you use our e-banking facilities? Please tick one response

Never Once 2-3 times 4-5 times 5+ times

Ranking question

Please rank the following according to their impact on your intention to share knowledge

with others in your workplace. Use ‘1’ to for the most important, and ‘5’ for the least

important.

Trustworthiness of my co-workers

Whether my managers’ assessment of my performance depends on my knowledge

sharing activities

Frequency of contact (physical or electronic) with my co-workers

My confidence in my knowledge and skills

Length of time that I have known my co-workers

Q4. How do I ensure that the respondents answer my questions accurately?

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

One of the limitations of questionnaires is that you will never be sure whether the

respondents have understood your questions, or indeed, whether they have taken the time

to provide accurate data. Also, you will inevitably have some unanswered questions on

some questionnaires – these might arise from the respondent being bored, running out of

time, not being willing to provide certain information, feeling that they do not know a

fact or have an opinion, or not understanding the question. It is your task to design the

questionnaire to make its completion as easy as possible for the respondent. This not only

involves adhering to advice and guidelines on questionnaire design, but also involves

understanding the potential respondents. What words do they use for artifacts or

concepts? What data are they likely to have access to? Which issues can they reasonably

be expected to have strong views on and which activities might they engage in regularly

and therefore be able to comment on?

Getting the questions right, whether they be open or closed questions, often requires the

researcher to think carefully about their research objectives and questions. Next, you need

to evaluate the different types of questions their suitability. Another important

consideration is the respondents. In addition, the phraseology of questions is important.

We suggest that you need to check that your questions:

• are as short as possible,

• are not leading or have implicit assumptions,

• do not include two questions in one,

• only exceptionally invite ‘yes/no’ answers,

• are not too vague or general,

• do not use double negatives

• are not, in any sense, invasive, or asking questions that the respondent is unlikely

to want to answer

• do not invite respondents to breach confidentiality.

Other authors also offer advice on question formulation; Ghauri et al. (2005) and Baker

and Foy (2008) offer particularly useful discussions. Baker and Foy (2008), for example,

11

respondents have understood your questions, or indeed, whether they have taken the time

to provide accurate data. Also, you will inevitably have some unanswered questions on

some questionnaires – these might arise from the respondent being bored, running out of

time, not being willing to provide certain information, feeling that they do not know a

fact or have an opinion, or not understanding the question. It is your task to design the

questionnaire to make its completion as easy as possible for the respondent. This not only

involves adhering to advice and guidelines on questionnaire design, but also involves

understanding the potential respondents. What words do they use for artifacts or

concepts? What data are they likely to have access to? Which issues can they reasonably

be expected to have strong views on and which activities might they engage in regularly

and therefore be able to comment on?

Getting the questions right, whether they be open or closed questions, often requires the

researcher to think carefully about their research objectives and questions. Next, you need

to evaluate the different types of questions their suitability. Another important

consideration is the respondents. In addition, the phraseology of questions is important.

We suggest that you need to check that your questions:

• are as short as possible,

• are not leading or have implicit assumptions,

• do not include two questions in one,

• only exceptionally invite ‘yes/no’ answers,

• are not too vague or general,

• do not use double negatives

• are not, in any sense, invasive, or asking questions that the respondent is unlikely

to want to answer

• do not invite respondents to breach confidentiality.

Other authors also offer advice on question formulation; Ghauri et al. (2005) and Baker

and Foy (2008) offer particularly useful discussions. Baker and Foy (2008), for example,

11

discuss question phraseology, question structure, and the link between these and potential

response bias.

Another key consideration is the order of the questions. In general, the order of questions

should be clear, often with questions clustered under theme or section headings. Often

earlier questions set the context for later questions. So, for example, if in a study on brand

equity co-creation, the first question asks ‘Please identify the online communities that

might discuss your brand’, this has ‘keyed in’ the respondent to thinking in terms of

online communities and the online presence for their brand. This will influence their

answers to subsequent questions. On the other hand, there are occasions when you do not

want the respondent to be influenced in their answer by previous questions. For example,

in our recent research on trust and the use of digital information sources, we first wanted

people to respond to an open question on trust, without being influenced by the views on

trust that were implicit in subsequent closed questions. Accordingly, we not only placed

that question first, but also did not give the respondents the other questions until they had

answered the first question. Another common consideration regarding the order of

questions is where to put questions on personal details, such as age, role, gender, or

salary, and on organizational details, such as budget, turnover, and number of staff.

Normally, these are included at the end of the questionnaire in order to encourage

respondents to complete the rest of the questionnaire before they come to sensitive

questions that they might not want to answer (and indeed, may not answer). In summary,

the order of questions is always important, but the specific order depends on your

research.

The quality of the response will also be enhanced by a clear title, coupled with a good,

short introductory paragraph at the beginning of the questionnaire. This paragraph should

introduce the purpose of the questionnaire, give the researcher’s affiliation and contact

details, and thank respondents for completing the questionnaire. Figure 3 provides a

succinct example. In some contexts it may be appropriate to elaborate further, but always

remember, time spent reading your introduction/instructions is time not spent on

answering questions. Presentation is also important. Aim for a professional and easy-to-

12

response bias.

Another key consideration is the order of the questions. In general, the order of questions

should be clear, often with questions clustered under theme or section headings. Often

earlier questions set the context for later questions. So, for example, if in a study on brand

equity co-creation, the first question asks ‘Please identify the online communities that

might discuss your brand’, this has ‘keyed in’ the respondent to thinking in terms of

online communities and the online presence for their brand. This will influence their

answers to subsequent questions. On the other hand, there are occasions when you do not

want the respondent to be influenced in their answer by previous questions. For example,

in our recent research on trust and the use of digital information sources, we first wanted

people to respond to an open question on trust, without being influenced by the views on

trust that were implicit in subsequent closed questions. Accordingly, we not only placed

that question first, but also did not give the respondents the other questions until they had

answered the first question. Another common consideration regarding the order of

questions is where to put questions on personal details, such as age, role, gender, or

salary, and on organizational details, such as budget, turnover, and number of staff.

Normally, these are included at the end of the questionnaire in order to encourage

respondents to complete the rest of the questionnaire before they come to sensitive

questions that they might not want to answer (and indeed, may not answer). In summary,

the order of questions is always important, but the specific order depends on your

research.

The quality of the response will also be enhanced by a clear title, coupled with a good,

short introductory paragraph at the beginning of the questionnaire. This paragraph should

introduce the purpose of the questionnaire, give the researcher’s affiliation and contact

details, and thank respondents for completing the questionnaire. Figure 3 provides a

succinct example. In some contexts it may be appropriate to elaborate further, but always

remember, time spent reading your introduction/instructions is time not spent on

answering questions. Presentation is also important. Aim for a professional and easy-to-

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 34

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.