Food Consumption Analysis: Cardiovascular Disease and Diet Solutions

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/29

|25

|27721

|367

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment solution is based on a review article from the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, focusing on the relationship between food consumption and cardiovascular disease (CVD). It addresses the impact of the globalized food system on dietary patterns and potential policy solutions. The analysis covers the development of the modern food system, the effects of various macronutrients and foods on CVD, and the necessary changes to the food system to address diet-related public health problems. The assignment likely involves analyzing a person's diet, comparing it against recommended guidelines, identifying key nutrients, and calculating the energy provided by each food group to assess overall dietary health in relation to CVD risk. It also involves comparing dietary intakes with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.

THE PRESENT AND FUTURE

STATE-OF-THE-ART REVIEW

Food Consumption and its Impact

on Cardiovascular Disease:

Importance of Solutions Focused on

the Globalized Food System

A Report From the Workshop Convened by the

World Heart Federation

Sonia S. Anand, MD, PHD,*y Corinna Hawkes, PHD,z Russell J. de Souza, SCD, RD,x Andrew Mente, PHD,y

Mahshid Dehghan, PHD,y Rachel Nugent, PHD,k Michael A. Zulyniak, PHD,* Tony Weis, PHD,{

Adam M. Bernstein, MD,# Ronald M. Krauss, MD,** Daan Kromhout, MPH, PHD,yy

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, P HD, DSC,zzxx Vasanti Malik, SCD,kk Miguel A. Martinez-Gonzalez, MPH, MD, PHD,{{

Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DRPH,## Salim Yusuf, MD, DPHIL ,y Walter C. Willett, MD, DRPH,{{ Barry M. Popkin, PHD***

ABSTRACT

Major scholars in the field, on the basis of a 3-day consensus, created an in-depth review of current knowledge on the

role of diet in cardiovascular disease (CVD), the changing global food system and global dietary patterns, and potential

policy solutions. Evidence from different countries and age/race/ethnicity/socioeconomic groups suggesting the health

effects studies of foods, macronutrients, and dietary patterns on CVD appear to be far more consistent though regional

knowledge gaps are highlighted. Large gaps in knowledge about the association of macronutrients to CVD in low-

and middle-income countries particularly linked with dietary patterns are reviewed. Our understanding of foods and

macronutrients in relationship to CVD is broadly clear; however, major gaps exist both in dietary pattern research and

ways to change diets and food systems. On the basis of the current evidence, the traditional Mediterranean-type diet,

including plant foods and emphasis on plant protein sources provides a well-tested healthy dietary pattern to reduce

CVD. (J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1590–614) © 2015 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

From the *Department of Medicine,McMaster University,Hamilton, Ontario, Canada;yPopulation Health Research Institute,

Hamilton Health Sciences and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; zCentre for Food Policy, City University, London,

J O U R N A LO F T H E A M E R I C A N C O L L E G E O FC A R D I O L O G Y V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

ª 2 0 1 5 B Y T H E A M E R I C A N C O L L E G E O FC A R D I O L O G Y F O U N D A T I O N I S S N 0 7 3 5 - 1 0 9 7 / $ 3 6 . 0 0

P U B L I S H E D B Y E L S E V I E R I N C . h t t p : / / d x . d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 / j . j a c c . 2 0 1 5 . 0 7 . 0 5 0

STATE-OF-THE-ART REVIEW

Food Consumption and its Impact

on Cardiovascular Disease:

Importance of Solutions Focused on

the Globalized Food System

A Report From the Workshop Convened by the

World Heart Federation

Sonia S. Anand, MD, PHD,*y Corinna Hawkes, PHD,z Russell J. de Souza, SCD, RD,x Andrew Mente, PHD,y

Mahshid Dehghan, PHD,y Rachel Nugent, PHD,k Michael A. Zulyniak, PHD,* Tony Weis, PHD,{

Adam M. Bernstein, MD,# Ronald M. Krauss, MD,** Daan Kromhout, MPH, PHD,yy

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, P HD, DSC,zzxx Vasanti Malik, SCD,kk Miguel A. Martinez-Gonzalez, MPH, MD, PHD,{{

Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DRPH,## Salim Yusuf, MD, DPHIL ,y Walter C. Willett, MD, DRPH,{{ Barry M. Popkin, PHD***

ABSTRACT

Major scholars in the field, on the basis of a 3-day consensus, created an in-depth review of current knowledge on the

role of diet in cardiovascular disease (CVD), the changing global food system and global dietary patterns, and potential

policy solutions. Evidence from different countries and age/race/ethnicity/socioeconomic groups suggesting the health

effects studies of foods, macronutrients, and dietary patterns on CVD appear to be far more consistent though regional

knowledge gaps are highlighted. Large gaps in knowledge about the association of macronutrients to CVD in low-

and middle-income countries particularly linked with dietary patterns are reviewed. Our understanding of foods and

macronutrients in relationship to CVD is broadly clear; however, major gaps exist both in dietary pattern research and

ways to change diets and food systems. On the basis of the current evidence, the traditional Mediterranean-type diet,

including plant foods and emphasis on plant protein sources provides a well-tested healthy dietary pattern to reduce

CVD. (J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1590–614) © 2015 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

From the *Department of Medicine,McMaster University,Hamilton, Ontario, Canada;yPopulation Health Research Institute,

Hamilton Health Sciences and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; zCentre for Food Policy, City University, London,

J O U R N A LO F T H E A M E R I C A N C O L L E G E O FC A R D I O L O G Y V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

ª 2 0 1 5 B Y T H E A M E R I C A N C O L L E G E O FC A R D I O L O G Y F O U N D A T I O N I S S N 0 7 3 5 - 1 0 9 7 / $ 3 6 . 0 0

P U B L I S H E D B Y E L S E V I E R I N C . h t t p : / / d x . d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 / j . j a c c . 2 0 1 5 . 0 7 . 0 5 0

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

T here is much controversy surrounding the

optimal diet for cardiovascular health. Data

relating diet to cardiovascular diseases

(CVDs) has predominantly been generated from

high-income countries (HIC), but >80% of CVD

deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries

(LMIC). Relatively sparse data on diet and CVD exist

from these countries though new data sources are

rapidly emerging (1,2). Noncommunicable diseases

are forecasted to increase substantially in LMIC

because of lifestyle transitions associated with in-

creasing urbanization, economic development, and

globalization. The Global Burden of Disease study

cites diet as a major factor behind the rise in hyper-

tension, diabetes, obesity, and other CVD compo-

nents (3). There are an estimated >500 million

obese (4,5) and close to 2 billion overweight or obese

individuals worldwide (6). Furthermore, unhealthy

dietary patterns have negative environmental im-

pacts, notably on climate change.

Poor quality diets are high in refined grains and

added sugars, salt, unhealthy fats, and animal-source

foods; and low in whole grains, fruits, vegetables,

legumes, fish, and nuts. They are often high in pro-

cessed food products—typically packaged and often

ready to consume—and light on whole foods and freshly

prepared dishes. These unhealthy diets are facilitated

by modern food environments, a problem that is

likely to become more widespread as food environ-

ments in LMIC shift to resemble those of HIC (5,7,8).

In this paper, we summarize the evidence relating

food to CVD, and the powerful forces that underpin

the creation of modern food environments—what we

call the global food system—to emphasize the impor-

tance of identifying systemic solutions to diet-related

health outcomes. We do this in the context of

increasing global attention to the importance

of improving food systems by the interna-

tional development and nutrition community

(9–11). Although the “food system” may seem

remote to a clinician sitting in an office seeing

a patient, its impact on the individuals they

are trying to treat are very real. This paper is on

the basis of a World Heart Federation inter-

national workshop to review the state of

knowledge on this topic. This review of diet,

dietary patterns, and CVD is not on the basis of

new systematic reviews or meta-analyses but

represents a careful review of many published

meta-analyses, seminal primary studies, and

recent research by the scholars who partici-

pated in the Consensus conference.

This paper presents: 1) an overview of the

development of the modern, globalized food

system and its implications for the food

supply; 2) a consensus on the evidence

relating various macronutrients and foods to

CVD and its related comorbidities; and 3) an

outline of how changes to the global food

system can address current diet-related pub-

lic health problems, and simultaneously have bene-

ficial impacts on climate change.

THE CHANGING FOOD SYSTEM AND

FOOD SUPPLY AND IMPLICATIONS FOR

DIETS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN, GLOBALIZED

FOOD SYSTEM. Food systems were once dominated

by local production for local markets, with relatively

little processing before foods reached the household

(Online Appendix, Box 1) (12). In contrast, the modern

A B B R E V I A T I O N S

A N D A C R O N Y M S

CHD =coronary heart disease

CI = confidence interval

CVD = cardiovascular disease

GI =glycemic index

GL = glycemic load

HDL-C = high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol

HIC = high-income countries

LDL-C = low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol

LMIC = low- and middle-

income countries

MI =myocardial infarction

OR = odds ratio

RCT = randomized controlled

trial

RR = relative risk

SSB =sugar-sweetened

beverage

T2DM =type 2 diabetes

mellitus

Barilla, Unilever Canada, Solae, Oldways, Kellogg’s, Quaker Oats, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, NuVal Griffin Hospital, Abbott, the

Canola Council of Canada, Dean Foods, the California Strawberry Commission, Haine Celestial, and the Alpro Foundation; has

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1591

optimal diet for cardiovascular health. Data

relating diet to cardiovascular diseases

(CVDs) has predominantly been generated from

high-income countries (HIC), but >80% of CVD

deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries

(LMIC). Relatively sparse data on diet and CVD exist

from these countries though new data sources are

rapidly emerging (1,2). Noncommunicable diseases

are forecasted to increase substantially in LMIC

because of lifestyle transitions associated with in-

creasing urbanization, economic development, and

globalization. The Global Burden of Disease study

cites diet as a major factor behind the rise in hyper-

tension, diabetes, obesity, and other CVD compo-

nents (3). There are an estimated >500 million

obese (4,5) and close to 2 billion overweight or obese

individuals worldwide (6). Furthermore, unhealthy

dietary patterns have negative environmental im-

pacts, notably on climate change.

Poor quality diets are high in refined grains and

added sugars, salt, unhealthy fats, and animal-source

foods; and low in whole grains, fruits, vegetables,

legumes, fish, and nuts. They are often high in pro-

cessed food products—typically packaged and often

ready to consume—and light on whole foods and freshly

prepared dishes. These unhealthy diets are facilitated

by modern food environments, a problem that is

likely to become more widespread as food environ-

ments in LMIC shift to resemble those of HIC (5,7,8).

In this paper, we summarize the evidence relating

food to CVD, and the powerful forces that underpin

the creation of modern food environments—what we

call the global food system—to emphasize the impor-

tance of identifying systemic solutions to diet-related

health outcomes. We do this in the context of

increasing global attention to the importance

of improving food systems by the interna-

tional development and nutrition community

(9–11). Although the “food system” may seem

remote to a clinician sitting in an office seeing

a patient, its impact on the individuals they

are trying to treat are very real. This paper is on

the basis of a World Heart Federation inter-

national workshop to review the state of

knowledge on this topic. This review of diet,

dietary patterns, and CVD is not on the basis of

new systematic reviews or meta-analyses but

represents a careful review of many published

meta-analyses, seminal primary studies, and

recent research by the scholars who partici-

pated in the Consensus conference.

This paper presents: 1) an overview of the

development of the modern, globalized food

system and its implications for the food

supply; 2) a consensus on the evidence

relating various macronutrients and foods to

CVD and its related comorbidities; and 3) an

outline of how changes to the global food

system can address current diet-related pub-

lic health problems, and simultaneously have bene-

ficial impacts on climate change.

THE CHANGING FOOD SYSTEM AND

FOOD SUPPLY AND IMPLICATIONS FOR

DIETS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN, GLOBALIZED

FOOD SYSTEM. Food systems were once dominated

by local production for local markets, with relatively

little processing before foods reached the household

(Online Appendix, Box 1) (12). In contrast, the modern

A B B R E V I A T I O N S

A N D A C R O N Y M S

CHD =coronary heart disease

CI = confidence interval

CVD = cardiovascular disease

GI =glycemic index

GL = glycemic load

HDL-C = high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol

HIC = high-income countries

LDL-C = low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol

LMIC = low- and middle-

income countries

MI =myocardial infarction

OR = odds ratio

RCT = randomized controlled

trial

RR = relative risk

SSB =sugar-sweetened

beverage

T2DM =type 2 diabetes

mellitus

Barilla, Unilever Canada, Solae, Oldways, Kellogg’s, Quaker Oats, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, NuVal Griffin Hospital, Abbott, the

Canola Council of Canada, Dean Foods, the California Strawberry Commission, Haine Celestial, and the Alpro Foundation; has

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1591

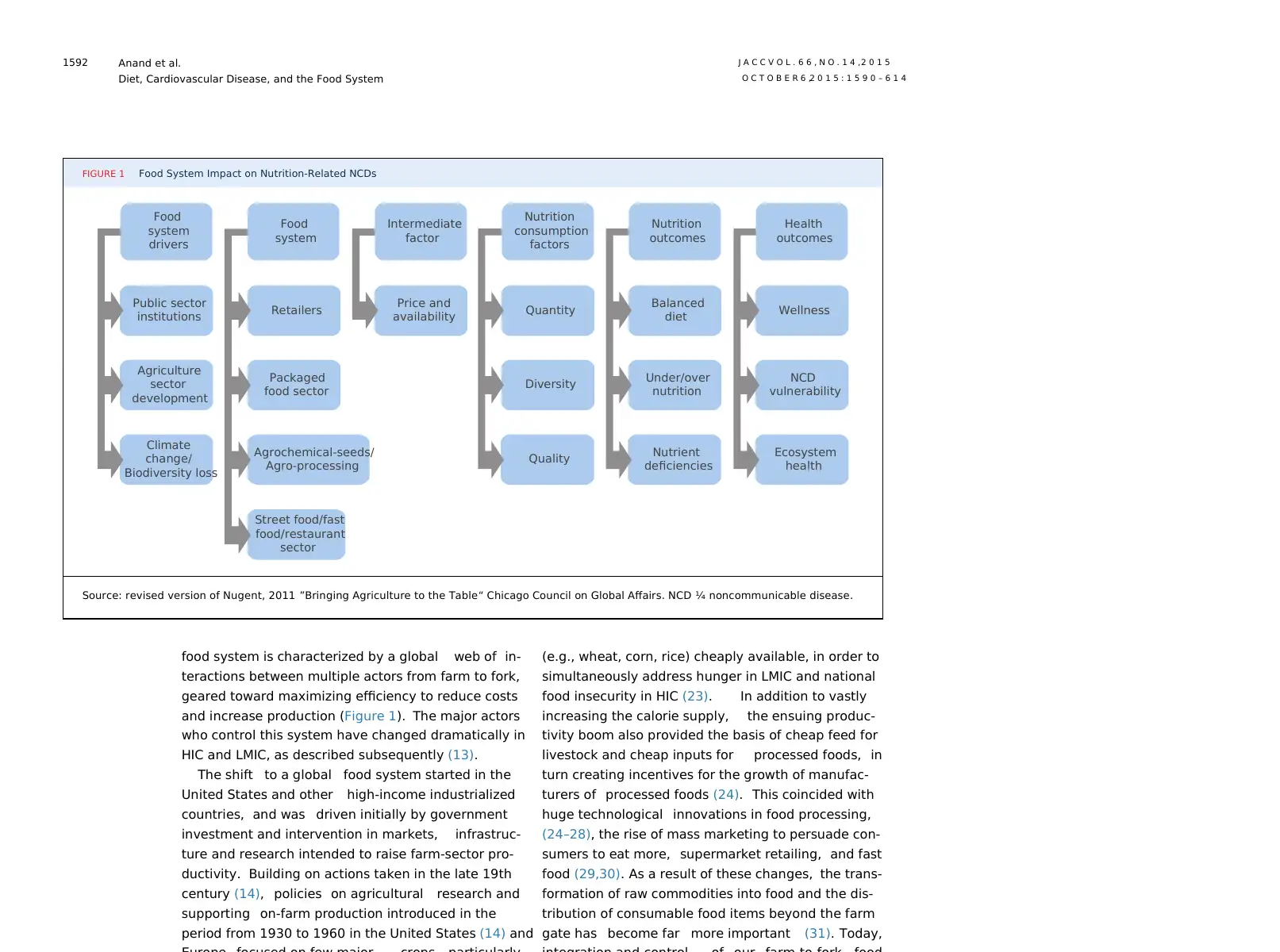

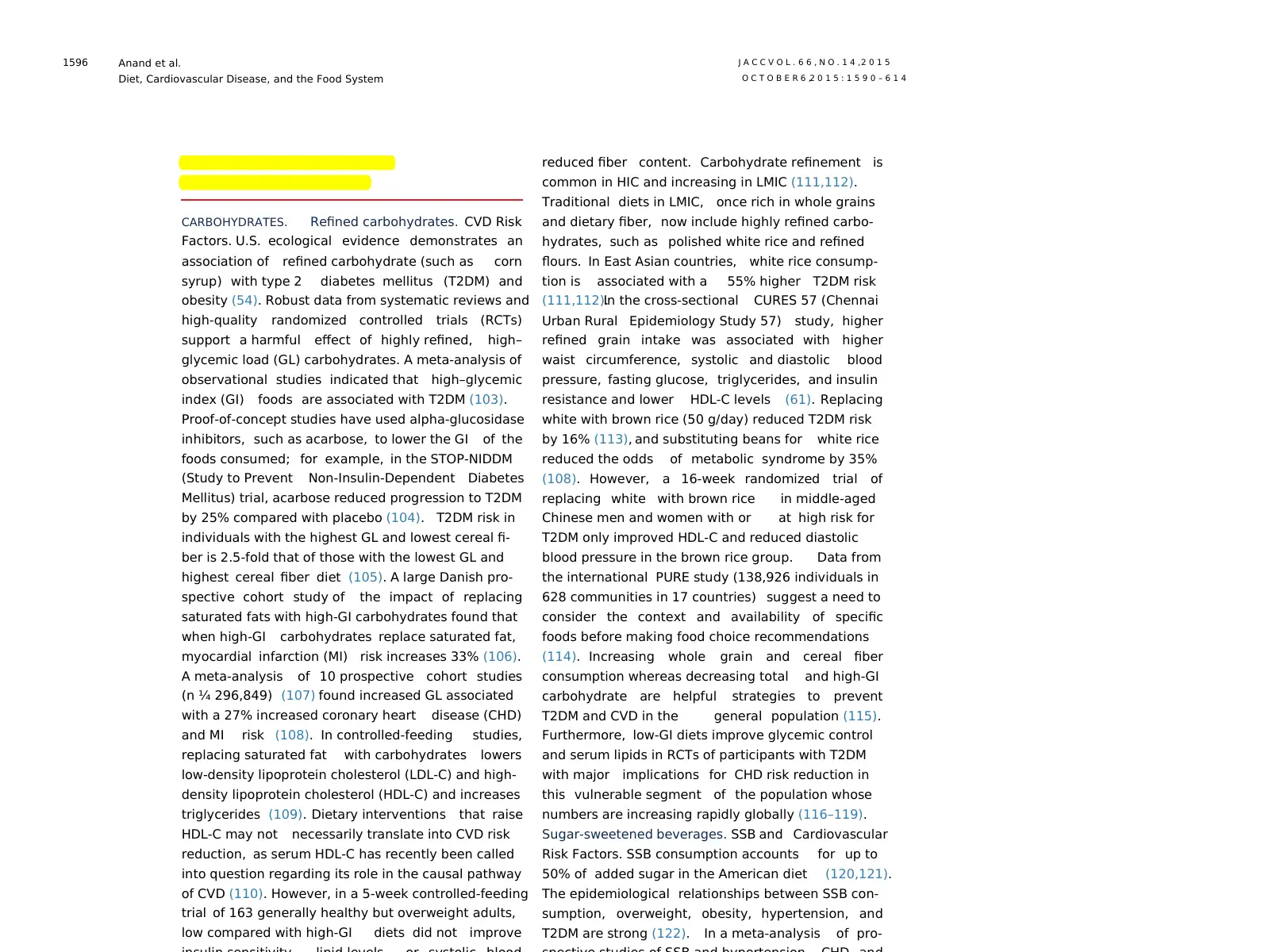

food system is characterized by a global web of in-

teractions between multiple actors from farm to fork,

geared toward maximizing efficiency to reduce costs

and increase production (Figure 1). The major actors

who control this system have changed dramatically in

HIC and LMIC, as described subsequently (13).

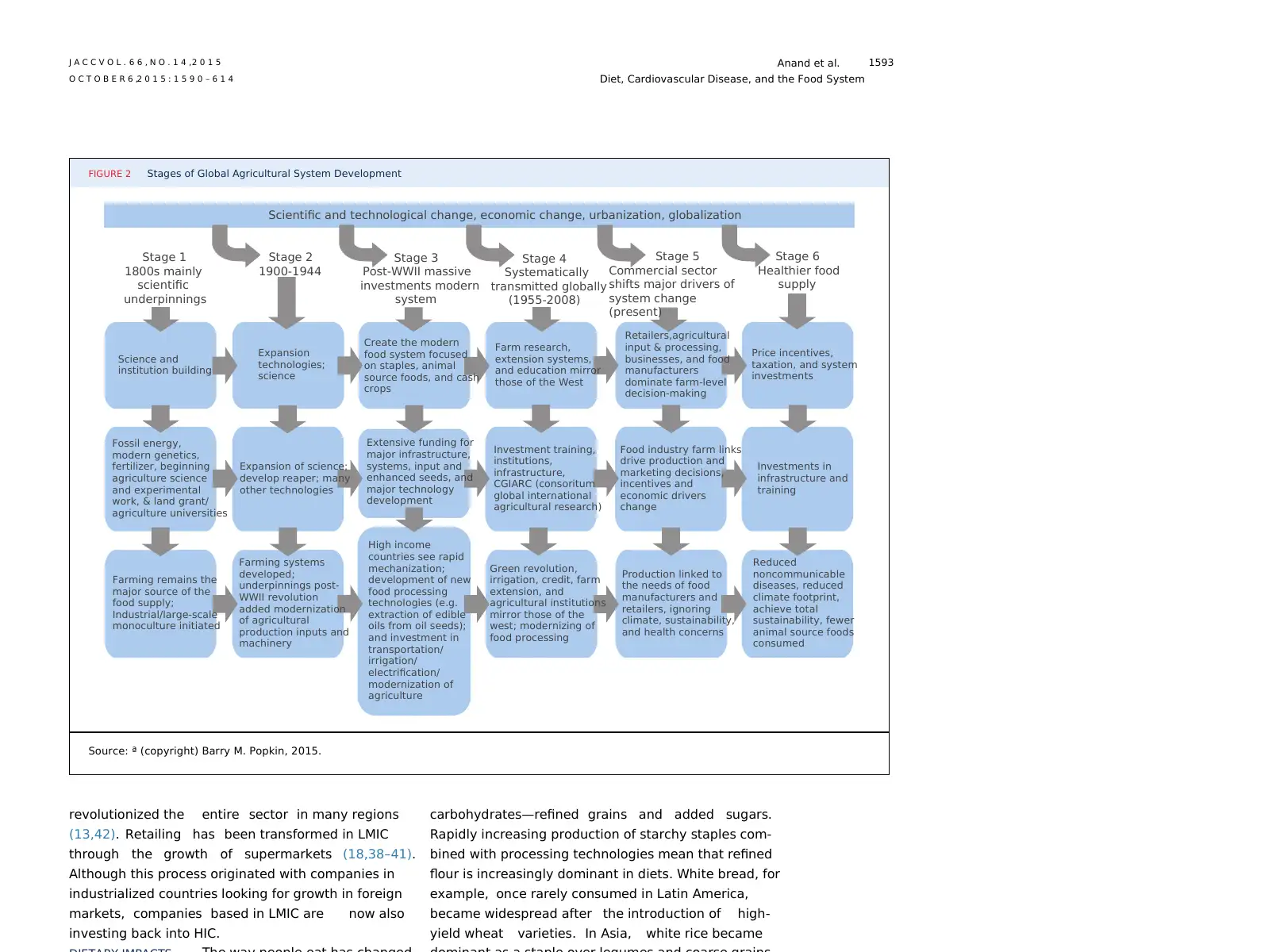

The shift to a global food system started in the

United States and other high-income industrialized

countries, and was driven initially by government

investment and intervention in markets, infrastruc-

ture and research intended to raise farm-sector pro-

ductivity. Building on actions taken in the late 19th

century (14), policies on agricultural research and

supporting on-farm production introduced in the

period from 1930 to 1960 in the United States (14) and

(e.g., wheat, corn, rice) cheaply available, in order to

simultaneously address hunger in LMIC and national

food insecurity in HIC (23). In addition to vastly

increasing the calorie supply, the ensuing produc-

tivity boom also provided the basis of cheap feed for

livestock and cheap inputs for processed foods, in

turn creating incentives for the growth of manufac-

turers of processed foods (24). This coincided with

huge technological innovations in food processing,

(24–28), the rise of mass marketing to persuade con-

sumers to eat more, supermarket retailing, and fast

food (29,30). As a result of these changes, the trans-

formation of raw commodities into food and the dis-

tribution of consumable food items beyond the farm

gate has become far more important (31). Today,

FIGURE 1 Food System Impact on Nutrition-Related NCDs

Food

system

drivers

Food

system

Intermediate

factor

Nutrition

consumption

factors

Nutrition

outcomes

Health

outcomes

Public sector

institutions Retailers Price and

availability Quantity Balanced

diet Wellness

Agriculture

sector

development

Packaged

food sector Diversity Under/over

nutrition

NCD

vulnerability

Climate

change/

Biodiversity loss

Agrochemical-seeds/

Agro-processing

Street food/fast

food/restaurant

sector

Quality Nutrient

deficiencies

Ecosystem

health

Source: revised version of Nugent, 2011 ”Bringing Agriculture to the Table“ Chicago Council on Global Affairs. NCD ¼ noncommunicable disease.

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1592

teractions between multiple actors from farm to fork,

geared toward maximizing efficiency to reduce costs

and increase production (Figure 1). The major actors

who control this system have changed dramatically in

HIC and LMIC, as described subsequently (13).

The shift to a global food system started in the

United States and other high-income industrialized

countries, and was driven initially by government

investment and intervention in markets, infrastruc-

ture and research intended to raise farm-sector pro-

ductivity. Building on actions taken in the late 19th

century (14), policies on agricultural research and

supporting on-farm production introduced in the

period from 1930 to 1960 in the United States (14) and

(e.g., wheat, corn, rice) cheaply available, in order to

simultaneously address hunger in LMIC and national

food insecurity in HIC (23). In addition to vastly

increasing the calorie supply, the ensuing produc-

tivity boom also provided the basis of cheap feed for

livestock and cheap inputs for processed foods, in

turn creating incentives for the growth of manufac-

turers of processed foods (24). This coincided with

huge technological innovations in food processing,

(24–28), the rise of mass marketing to persuade con-

sumers to eat more, supermarket retailing, and fast

food (29,30). As a result of these changes, the trans-

formation of raw commodities into food and the dis-

tribution of consumable food items beyond the farm

gate has become far more important (31). Today,

FIGURE 1 Food System Impact on Nutrition-Related NCDs

Food

system

drivers

Food

system

Intermediate

factor

Nutrition

consumption

factors

Nutrition

outcomes

Health

outcomes

Public sector

institutions Retailers Price and

availability Quantity Balanced

diet Wellness

Agriculture

sector

development

Packaged

food sector Diversity Under/over

nutrition

NCD

vulnerability

Climate

change/

Biodiversity loss

Agrochemical-seeds/

Agro-processing

Street food/fast

food/restaurant

sector

Quality Nutrient

deficiencies

Ecosystem

health

Source: revised version of Nugent, 2011 ”Bringing Agriculture to the Table“ Chicago Council on Global Affairs. NCD ¼ noncommunicable disease.

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1592

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

revolutionized the entire sector in many regions

(13,42). Retailing has been transformed in LMIC

through the growth of supermarkets (18,38–41).

Although this process originated with companies in

industrialized countries looking for growth in foreign

markets, companies based in LMIC are now also

investing back into HIC.

carbohydrates—refined grains and added sugars.

Rapidly increasing production of starchy staples com-

bined with processing technologies mean that refined

flour is increasingly dominant in diets. White bread, for

example, once rarely consumed in Latin America,

became widespread after the introduction of high-

yield wheat varieties. In Asia, white rice became

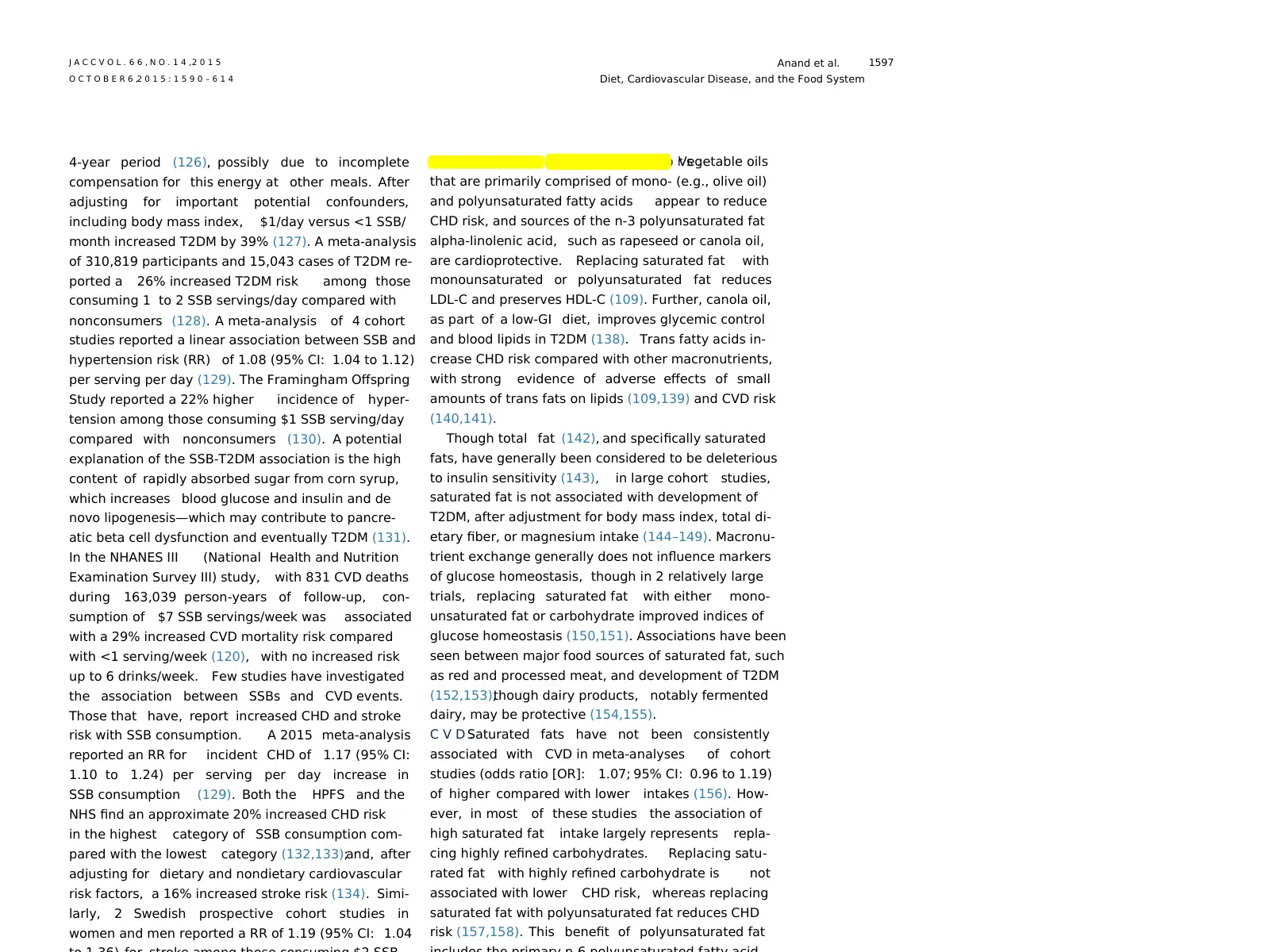

FIGURE 2 Stages of Global Agricultural System Development

Scientific and technological change, economic change, urbanization, globalization

Stage 1

1800s mainly

scientific

underpinnings

Stage 2

1900-1944

Stage 3

Post-WWII massive

investments modern

system

Stage 4

Systematically

transmitted globally

(1955-2008)

Stage 5

Commercial sector

shifts major drivers of

system change

(present)

Stage 6

Healthier food

supply

Price incentives,

taxation, and system

investments

Retailers,agricultural

input & processing,

businesses, and food

manufacturers

dominate farm-level

decision-making

Farm research,

extension systems,

and education mirror

those of the West

Create the modern

food system focused

on staples, animal

source foods, and cash

crops

Expansion

technologies;

science

Science and

institution building

Fossil energy,

modern genetics,

fertilizer, beginning

agriculture science

and experimental

work, & land grant/

agriculture universities

Expansion of science;

develop reaper; many

other technologies

Extensive funding for

major infrastructure,

systems, input and

enhanced seeds, and

major technology

development

Investment training,

institutions,

infrastructure,

CGIARC (consoritum

global international

agricultural research)

Food industry farm links

drive production and

marketing decisions,

incentives and

economic drivers

change

Investments in

infrastructure and

training

Reduced

noncommunicable

diseases, reduced

climate footprint,

achieve total

sustainability, fewer

animal source foods

consumed

Production linked to

the needs of food

manufacturers and

retailers, ignoring

climate, sustainability,

and health concerns

Green revolution,

irrigation, credit, farm

extension, and

agricultural institutions

mirror those of the

west; modernizing of

food processing

High income

countries see rapid

mechanization;

development of new

food processing

technologies (e.g.

extraction of edible

oils from oil seeds);

and investment in

transportation/

irrigation/

electrification/

modernization of

agriculture

Farming systems

developed;

underpinnings post-

WWII revolution

added modernization

of agricultural

production inputs and

machinery

Farming remains the

major source of the

food supply;

Industrial/large-scale

monoculture initiated

Source: ª (copyright) Barry M. Popkin, 2015.

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1593

(13,42). Retailing has been transformed in LMIC

through the growth of supermarkets (18,38–41).

Although this process originated with companies in

industrialized countries looking for growth in foreign

markets, companies based in LMIC are now also

investing back into HIC.

carbohydrates—refined grains and added sugars.

Rapidly increasing production of starchy staples com-

bined with processing technologies mean that refined

flour is increasingly dominant in diets. White bread, for

example, once rarely consumed in Latin America,

became widespread after the introduction of high-

yield wheat varieties. In Asia, white rice became

FIGURE 2 Stages of Global Agricultural System Development

Scientific and technological change, economic change, urbanization, globalization

Stage 1

1800s mainly

scientific

underpinnings

Stage 2

1900-1944

Stage 3

Post-WWII massive

investments modern

system

Stage 4

Systematically

transmitted globally

(1955-2008)

Stage 5

Commercial sector

shifts major drivers of

system change

(present)

Stage 6

Healthier food

supply

Price incentives,

taxation, and system

investments

Retailers,agricultural

input & processing,

businesses, and food

manufacturers

dominate farm-level

decision-making

Farm research,

extension systems,

and education mirror

those of the West

Create the modern

food system focused

on staples, animal

source foods, and cash

crops

Expansion

technologies;

science

Science and

institution building

Fossil energy,

modern genetics,

fertilizer, beginning

agriculture science

and experimental

work, & land grant/

agriculture universities

Expansion of science;

develop reaper; many

other technologies

Extensive funding for

major infrastructure,

systems, input and

enhanced seeds, and

major technology

development

Investment training,

institutions,

infrastructure,

CGIARC (consoritum

global international

agricultural research)

Food industry farm links

drive production and

marketing decisions,

incentives and

economic drivers

change

Investments in

infrastructure and

training

Reduced

noncommunicable

diseases, reduced

climate footprint,

achieve total

sustainability, fewer

animal source foods

consumed

Production linked to

the needs of food

manufacturers and

retailers, ignoring

climate, sustainability,

and health concerns

Green revolution,

irrigation, credit, farm

extension, and

agricultural institutions

mirror those of the

west; modernizing of

food processing

High income

countries see rapid

mechanization;

development of new

food processing

technologies (e.g.

extraction of edible

oils from oil seeds);

and investment in

transportation/

irrigation/

electrification/

modernization of

agriculture

Farming systems

developed;

underpinnings post-

WWII revolution

added modernization

of agricultural

production inputs and

machinery

Farming remains the

major source of the

food supply;

Industrial/large-scale

monoculture initiated

Source: ª (copyright) Barry M. Popkin, 2015.

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1593

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

United States packaged and processed food supply,

over 75% of foods, have some form of added sugar

(60). With urbanization there is some evidence to

show that refined carbohydrate consumption is

increasing, whereas consumption of traditional

grains (i.e., millet, maize) is decreasing in LMIC

(61,62).

A second key change has been the increasing

intake of vegetable oils, including processed vege-

table oils, and a decline in consumption of animal fats

(2,63). This was initially driven by rising production

of soybeans in the United States, later in Argentina

and Brazil, and then palm oil in East Asia. Oilseeds are

now among the most widely traded crops, and are

also processed to create margarines and vegetable

shortenings and into partially hydrogenated fats and

bleached deodorized oils for use in processed foods

(Online Appendix, Box 2). Between 1958 and 1996,a

major global shift occurred in the amount and types

of available fats, with soybean, palm, and rapeseed/

canola oils replacing butter, tallow, and lard. From

1958 to 1962, soybean, palm, and rapeseed/canola oils

represented 20% of the 29 million metric tons of fat

produced globally per year, whereas butter, lard, and

tallow represented 37%. By 1996 to 2001, these oils

accounted for 52% of the 103 million metric tons of fat

produced globally per year, whereas butter, lard, and

tallow contributed 20% (64). This has implications for

consumption of fatty acids. Palm oil (deodorized) has

become an increasing source of saturated fatty acids;

and partially hydrogenated fats are the main source

of trans fatty acids. Between 1990 and 2010, global

saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and trans fat in-

takes remained stable (trans fats going down in HIC

and up in LMIC), whereas n-6, seafood n-3, and plant

n-3 fat intakes each increased (65). Vegetable oil

consumption remains 2 times higher in HIC than in

LMIC. However, trans fat consumption is very high in

many LMIC although decreasing markedly in HIC. In

India, for example, vanaspati, a vegetable ghee used

A third key change has been the increasing

global consumption of meat, which has been made

economically feasible by subsidized production of

crops for animal feed—most importantly corn and

soybeans (soybean oil is a byproduct of soymeal

production for animals) (66–69). At very low levels

of intake animal food consumption may not induce

harm, providing high-quality protein and iron,

whereas excess animal food intake in HIC may

be linked to adverse health outcomes, particularly

from processed meats (70). Meat consumption has

increased considerably worldwide, and there is sub-

stantially greater production of meat in HIC than in

LMIC (71). North and South America, Europe, and

Australia/New Zealand have the highest meat intake,

whereas Asia and Africa have the lowest (72,73).

Processed meats (which refers to post-butchering

modifications of foods such as curing, smoking, or

addition of sodium nitrate), account for 35.8% of all

meat consumed in HIC (unpublished data from the

PURE [Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological]

study) (71).

Dietary consumption patterns of other protein

sources have been mixed. Between 1973 and 1997,

dairy consumption per capita (kilograms) increased

in LMIC by w48% and is projected to almost double

(93% increase) by 2020. On average, fish consump-

tion is 2 to 3 times higher in HIC than LMIC (74),

although with marked heterogeneity within income

categories. China has the highest per-capita con-

sumption of fish in the world, followed by Oceania,

North America, and Europe (74). Globally, although

there has been little or no increase in sea fish con-

sumption per capita since the 1960s, catches per year

have risen exponentially (75) and freshwater fish

intake has increased during this time (71). Eggs are

similarly consumed in higher quantities (2 to 6 times

per week) in HIC relative to LMIC, with a 14% decline

in consumption in HIC observed between 1980 and

2000, and no change was observed in LMIC (76). The

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1594

over 75% of foods, have some form of added sugar

(60). With urbanization there is some evidence to

show that refined carbohydrate consumption is

increasing, whereas consumption of traditional

grains (i.e., millet, maize) is decreasing in LMIC

(61,62).

A second key change has been the increasing

intake of vegetable oils, including processed vege-

table oils, and a decline in consumption of animal fats

(2,63). This was initially driven by rising production

of soybeans in the United States, later in Argentina

and Brazil, and then palm oil in East Asia. Oilseeds are

now among the most widely traded crops, and are

also processed to create margarines and vegetable

shortenings and into partially hydrogenated fats and

bleached deodorized oils for use in processed foods

(Online Appendix, Box 2). Between 1958 and 1996,a

major global shift occurred in the amount and types

of available fats, with soybean, palm, and rapeseed/

canola oils replacing butter, tallow, and lard. From

1958 to 1962, soybean, palm, and rapeseed/canola oils

represented 20% of the 29 million metric tons of fat

produced globally per year, whereas butter, lard, and

tallow represented 37%. By 1996 to 2001, these oils

accounted for 52% of the 103 million metric tons of fat

produced globally per year, whereas butter, lard, and

tallow contributed 20% (64). This has implications for

consumption of fatty acids. Palm oil (deodorized) has

become an increasing source of saturated fatty acids;

and partially hydrogenated fats are the main source

of trans fatty acids. Between 1990 and 2010, global

saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and trans fat in-

takes remained stable (trans fats going down in HIC

and up in LMIC), whereas n-6, seafood n-3, and plant

n-3 fat intakes each increased (65). Vegetable oil

consumption remains 2 times higher in HIC than in

LMIC. However, trans fat consumption is very high in

many LMIC although decreasing markedly in HIC. In

India, for example, vanaspati, a vegetable ghee used

A third key change has been the increasing

global consumption of meat, which has been made

economically feasible by subsidized production of

crops for animal feed—most importantly corn and

soybeans (soybean oil is a byproduct of soymeal

production for animals) (66–69). At very low levels

of intake animal food consumption may not induce

harm, providing high-quality protein and iron,

whereas excess animal food intake in HIC may

be linked to adverse health outcomes, particularly

from processed meats (70). Meat consumption has

increased considerably worldwide, and there is sub-

stantially greater production of meat in HIC than in

LMIC (71). North and South America, Europe, and

Australia/New Zealand have the highest meat intake,

whereas Asia and Africa have the lowest (72,73).

Processed meats (which refers to post-butchering

modifications of foods such as curing, smoking, or

addition of sodium nitrate), account for 35.8% of all

meat consumed in HIC (unpublished data from the

PURE [Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological]

study) (71).

Dietary consumption patterns of other protein

sources have been mixed. Between 1973 and 1997,

dairy consumption per capita (kilograms) increased

in LMIC by w48% and is projected to almost double

(93% increase) by 2020. On average, fish consump-

tion is 2 to 3 times higher in HIC than LMIC (74),

although with marked heterogeneity within income

categories. China has the highest per-capita con-

sumption of fish in the world, followed by Oceania,

North America, and Europe (74). Globally, although

there has been little or no increase in sea fish con-

sumption per capita since the 1960s, catches per year

have risen exponentially (75) and freshwater fish

intake has increased during this time (71). Eggs are

similarly consumed in higher quantities (2 to 6 times

per week) in HIC relative to LMIC, with a 14% decline

in consumption in HIC observed between 1980 and

2000, and no change was observed in LMIC (76). The

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1594

Total production of tree nuts in 2012 was 3.5 million

metric tons, a 5.5% increase from 2011. World con-

sumption of tree nuts in 2011 exceeded 3 million

metric tons (81).

A fourth key change is the marked growth of pur-

chases of all packaged foods and beverages (all cate-

gories of processing). This process is accelerating

across all LMIC markets (13,82,83). For example,

58% of calories consumed by Mexicans come from

packaged foods and beverages, which is similar

throughout the Americas (83) and even within the

United States (66%) (65,84). The proportion for China

is 28.5% and rising rapidly (36,82,83). The component

of snack foods that is “ultra-processed” (i.e., ready to

eat) varies depending on the method of measurement

but is increasing wherever it is studied at all income

levels (50,85,86). The shift to ultra-processed foods

has not just affected the food available for consump-

tion but also the way food is consumed (87). The way

people eat has changed greatly across the globe and the

pace of change is quickening. Snacking and snack

foods have grown in frequency and number (43–48);

eating frequency has increased; away-from-home

eating in restaurants, in fast food outlets, and from

take-out meals is increasing dramatically in LMIC;

both at home and away-from-home eating increa-

singly involve fried and processed food (47); and

the overall proportion of highly processed food in diets

has grown (50,51).

A fifth trend noted previously in relation to the

added sugar change is the shift in the way LMIC are

experiencing a marked increase in added sugar in

beverages. In the 1985 to 2005 period extensive added

sugar intake occurred across HIC (55) but more

recently large increases have occurred in LMIC,

particularly in consumption of SSBs and ultra-

processed foods (56–59). Today in the U.S. packaged

and processed food supply, >75% of foods have some

form of added sugar (60).

In addition, fruit and vegetable intake has re-

reported consuming fruits and vegetables 5 or more

times per day (91).

Although all of these changes across LMIC display

great heterogeneity (92), the global food system has

clearly reached all corners of the LMIC urban and

rural sector and major shifts in diets appear to be

accelerating.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS. The

modern food system is a major force in a range of

serious environmental problems, including climate

change (as a leading source of greenhouse gas emis-

sions, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous

oxide), the loss of biodiversity, the strain on fresh-

water resources, and the release of persistent toxins,

excess nitrates and phosphates (from fertilizer and

concentrated livestock operations, causing wide-

spread problems of eutrophication), and animal phar-

maceutical residues into waterways (12,93–95).

The major causes are beef and other large animals

for greenhouse gas and the metabolic losses associ-

ated with shifting the product of nearly one-third of

the world’s arable land to concentrated animals,

which effectively magnifies the resource budgets and

pollution loads of industrial monocultures (34). The

expansion of low-input agriculture and extensive

ranching are also major factors in deforestation,

which bear heavily on both climate change (as carbon

is released from vegetation and soils and sequestra-

tion capacity diminishes) and biodiversity loss.

In addition to being a major force in many envi-

ronmental problems, world agriculture is also ex-

tremely vulnerable to climate change, biodiversity

loss, declining freshwater availability, and the inevi-

table limits of nonrenewable resources (e.g., fossil

energy, high-grade phosphorous) although vulnera-

bility is highly uneven on a world scale (96). Many of

the world’s poorest-regions are poised to be most

adversely affected by rising average temperatures,

aridity, and water stress, as well as through increas-

ingly severe extreme weather events such as drought

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1595

metric tons, a 5.5% increase from 2011. World con-

sumption of tree nuts in 2011 exceeded 3 million

metric tons (81).

A fourth key change is the marked growth of pur-

chases of all packaged foods and beverages (all cate-

gories of processing). This process is accelerating

across all LMIC markets (13,82,83). For example,

58% of calories consumed by Mexicans come from

packaged foods and beverages, which is similar

throughout the Americas (83) and even within the

United States (66%) (65,84). The proportion for China

is 28.5% and rising rapidly (36,82,83). The component

of snack foods that is “ultra-processed” (i.e., ready to

eat) varies depending on the method of measurement

but is increasing wherever it is studied at all income

levels (50,85,86). The shift to ultra-processed foods

has not just affected the food available for consump-

tion but also the way food is consumed (87). The way

people eat has changed greatly across the globe and the

pace of change is quickening. Snacking and snack

foods have grown in frequency and number (43–48);

eating frequency has increased; away-from-home

eating in restaurants, in fast food outlets, and from

take-out meals is increasing dramatically in LMIC;

both at home and away-from-home eating increa-

singly involve fried and processed food (47); and

the overall proportion of highly processed food in diets

has grown (50,51).

A fifth trend noted previously in relation to the

added sugar change is the shift in the way LMIC are

experiencing a marked increase in added sugar in

beverages. In the 1985 to 2005 period extensive added

sugar intake occurred across HIC (55) but more

recently large increases have occurred in LMIC,

particularly in consumption of SSBs and ultra-

processed foods (56–59). Today in the U.S. packaged

and processed food supply, >75% of foods have some

form of added sugar (60).

In addition, fruit and vegetable intake has re-

reported consuming fruits and vegetables 5 or more

times per day (91).

Although all of these changes across LMIC display

great heterogeneity (92), the global food system has

clearly reached all corners of the LMIC urban and

rural sector and major shifts in diets appear to be

accelerating.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS. The

modern food system is a major force in a range of

serious environmental problems, including climate

change (as a leading source of greenhouse gas emis-

sions, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous

oxide), the loss of biodiversity, the strain on fresh-

water resources, and the release of persistent toxins,

excess nitrates and phosphates (from fertilizer and

concentrated livestock operations, causing wide-

spread problems of eutrophication), and animal phar-

maceutical residues into waterways (12,93–95).

The major causes are beef and other large animals

for greenhouse gas and the metabolic losses associ-

ated with shifting the product of nearly one-third of

the world’s arable land to concentrated animals,

which effectively magnifies the resource budgets and

pollution loads of industrial monocultures (34). The

expansion of low-input agriculture and extensive

ranching are also major factors in deforestation,

which bear heavily on both climate change (as carbon

is released from vegetation and soils and sequestra-

tion capacity diminishes) and biodiversity loss.

In addition to being a major force in many envi-

ronmental problems, world agriculture is also ex-

tremely vulnerable to climate change, biodiversity

loss, declining freshwater availability, and the inevi-

table limits of nonrenewable resources (e.g., fossil

energy, high-grade phosphorous) although vulnera-

bility is highly uneven on a world scale (96). Many of

the world’s poorest-regions are poised to be most

adversely affected by rising average temperatures,

aridity, and water stress, as well as through increas-

ingly severe extreme weather events such as drought

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1595

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

MACRONUTRIENTS, FOODS,

AND CVD RISK FACTORS

CARBOHYDRATES. Refined carbohydrates. CVD Risk

Factors. U.S. ecological evidence demonstrates an

association of refined carbohydrate (such as corn

syrup) with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and

obesity (54). Robust data from systematic reviews and

high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

support a harmful effect of highly refined, high–

glycemic load (GL) carbohydrates. A meta-analysis of

observational studies indicated that high–glycemic

index (GI) foods are associated with T2DM (103).

Proof-of-concept studies have used alpha-glucosidase

inhibitors, such as acarbose, to lower the GI of the

foods consumed; for example, in the STOP-NIDDM

(Study to Prevent Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes

Mellitus) trial, acarbose reduced progression to T2DM

by 25% compared with placebo (104). T2DM risk in

individuals with the highest GL and lowest cereal fi-

ber is 2.5-fold that of those with the lowest GL and

highest cereal fiber diet (105). A large Danish pro-

spective cohort study of the impact of replacing

saturated fats with high-GI carbohydrates found that

when high-GI carbohydrates replace saturated fat,

myocardial infarction (MI) risk increases 33% (106).

A meta-analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies

(n ¼ 296,849) (107) found increased GL associated

with a 27% increased coronary heart disease (CHD)

and MI risk (108). In controlled-feeding studies,

replacing saturated fat with carbohydrates lowers

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-

density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and increases

triglycerides (109). Dietary interventions that raise

HDL-C may not necessarily translate into CVD risk

reduction, as serum HDL-C has recently been called

into question regarding its role in the causal pathway

of CVD (110). However, in a 5-week controlled-feeding

trial of 163 generally healthy but overweight adults,

low compared with high-GI diets did not improve

reduced fiber content. Carbohydrate refinement is

common in HIC and increasing in LMIC (111,112).

Traditional diets in LMIC, once rich in whole grains

and dietary fiber, now include highly refined carbo-

hydrates, such as polished white rice and refined

flours. In East Asian countries, white rice consump-

tion is associated with a 55% higher T2DM risk

(111,112).In the cross-sectional CURES 57 (Chennai

Urban Rural Epidemiology Study 57) study, higher

refined grain intake was associated with higher

waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood

pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and insulin

resistance and lower HDL-C levels (61). Replacing

white with brown rice (50 g/day) reduced T2DM risk

by 16% (113), and substituting beans for white rice

reduced the odds of metabolic syndrome by 35%

(108). However, a 16-week randomized trial of

replacing white with brown rice in middle-aged

Chinese men and women with or at high risk for

T2DM only improved HDL-C and reduced diastolic

blood pressure in the brown rice group. Data from

the international PURE study (138,926 individuals in

628 communities in 17 countries) suggest a need to

consider the context and availability of specific

foods before making food choice recommendations

(114). Increasing whole grain and cereal fiber

consumption whereas decreasing total and high-GI

carbohydrate are helpful strategies to prevent

T2DM and CVD in the general population (115).

Furthermore, low-GI diets improve glycemic control

and serum lipids in RCTs of participants with T2DM

with major implications for CHD risk reduction in

this vulnerable segment of the population whose

numbers are increasing rapidly globally (116–119).

Sugar-sweetened beverages. SSB and Cardiovascular

Risk Factors. SSB consumption accounts for up to

50% of added sugar in the American diet (120,121).

The epidemiological relationships between SSB con-

sumption, overweight, obesity, hypertension, and

T2DM are strong (122). In a meta-analysis of pro-

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1596

AND CVD RISK FACTORS

CARBOHYDRATES. Refined carbohydrates. CVD Risk

Factors. U.S. ecological evidence demonstrates an

association of refined carbohydrate (such as corn

syrup) with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and

obesity (54). Robust data from systematic reviews and

high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

support a harmful effect of highly refined, high–

glycemic load (GL) carbohydrates. A meta-analysis of

observational studies indicated that high–glycemic

index (GI) foods are associated with T2DM (103).

Proof-of-concept studies have used alpha-glucosidase

inhibitors, such as acarbose, to lower the GI of the

foods consumed; for example, in the STOP-NIDDM

(Study to Prevent Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes

Mellitus) trial, acarbose reduced progression to T2DM

by 25% compared with placebo (104). T2DM risk in

individuals with the highest GL and lowest cereal fi-

ber is 2.5-fold that of those with the lowest GL and

highest cereal fiber diet (105). A large Danish pro-

spective cohort study of the impact of replacing

saturated fats with high-GI carbohydrates found that

when high-GI carbohydrates replace saturated fat,

myocardial infarction (MI) risk increases 33% (106).

A meta-analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies

(n ¼ 296,849) (107) found increased GL associated

with a 27% increased coronary heart disease (CHD)

and MI risk (108). In controlled-feeding studies,

replacing saturated fat with carbohydrates lowers

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-

density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and increases

triglycerides (109). Dietary interventions that raise

HDL-C may not necessarily translate into CVD risk

reduction, as serum HDL-C has recently been called

into question regarding its role in the causal pathway

of CVD (110). However, in a 5-week controlled-feeding

trial of 163 generally healthy but overweight adults,

low compared with high-GI diets did not improve

reduced fiber content. Carbohydrate refinement is

common in HIC and increasing in LMIC (111,112).

Traditional diets in LMIC, once rich in whole grains

and dietary fiber, now include highly refined carbo-

hydrates, such as polished white rice and refined

flours. In East Asian countries, white rice consump-

tion is associated with a 55% higher T2DM risk

(111,112).In the cross-sectional CURES 57 (Chennai

Urban Rural Epidemiology Study 57) study, higher

refined grain intake was associated with higher

waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood

pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and insulin

resistance and lower HDL-C levels (61). Replacing

white with brown rice (50 g/day) reduced T2DM risk

by 16% (113), and substituting beans for white rice

reduced the odds of metabolic syndrome by 35%

(108). However, a 16-week randomized trial of

replacing white with brown rice in middle-aged

Chinese men and women with or at high risk for

T2DM only improved HDL-C and reduced diastolic

blood pressure in the brown rice group. Data from

the international PURE study (138,926 individuals in

628 communities in 17 countries) suggest a need to

consider the context and availability of specific

foods before making food choice recommendations

(114). Increasing whole grain and cereal fiber

consumption whereas decreasing total and high-GI

carbohydrate are helpful strategies to prevent

T2DM and CVD in the general population (115).

Furthermore, low-GI diets improve glycemic control

and serum lipids in RCTs of participants with T2DM

with major implications for CHD risk reduction in

this vulnerable segment of the population whose

numbers are increasing rapidly globally (116–119).

Sugar-sweetened beverages. SSB and Cardiovascular

Risk Factors. SSB consumption accounts for up to

50% of added sugar in the American diet (120,121).

The epidemiological relationships between SSB con-

sumption, overweight, obesity, hypertension, and

T2DM are strong (122). In a meta-analysis of pro-

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1596

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4-year period (126), possibly due to incomplete

compensation for this energy at other meals. After

adjusting for important potential confounders,

including body mass index, $1/day versus <1 SSB/

month increased T2DM by 39% (127). A meta-analysis

of 310,819 participants and 15,043 cases of T2DM re-

ported a 26% increased T2DM risk among those

consuming 1 to 2 SSB servings/day compared with

nonconsumers (128). A meta-analysis of 4 cohort

studies reported a linear association between SSB and

hypertension risk (RR) of 1.08 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.12)

per serving per day (129). The Framingham Offspring

Study reported a 22% higher incidence of hyper-

tension among those consuming $1 SSB serving/day

compared with nonconsumers (130). A potential

explanation of the SSB-T2DM association is the high

content of rapidly absorbed sugar from corn syrup,

which increases blood glucose and insulin and de

novo lipogenesis—which may contribute to pancre-

atic beta cell dysfunction and eventually T2DM (131).

In the NHANES III (National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey III) study, with 831 CVD deaths

during 163,039 person-years of follow-up, con-

sumption of $7 SSB servings/week was associated

with a 29% increased CVD mortality risk compared

with <1 serving/week (120), with no increased risk

up to 6 drinks/week. Few studies have investigated

the association between SSBs and CVD events.

Those that have, report increased CHD and stroke

risk with SSB consumption. A 2015 meta-analysis

reported an RR for incident CHD of 1.17 (95% CI:

1.10 to 1.24) per serving per day increase in

SSB consumption (129). Both the HPFS and the

NHS find an approximate 20% increased CHD risk

in the highest category of SSB consumption com-

pared with the lowest category (132,133);and, after

adjusting for dietary and nondietary cardiovascular

risk factors, a 16% increased stroke risk (134). Simi-

larly, 2 Swedish prospective cohort studies in

women and men reported a RR of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.04

FATS AND OILS. C V D r i s k f a c t o r s .Vegetable oils

that are primarily comprised of mono- (e.g., olive oil)

and polyunsaturated fatty acids appear to reduce

CHD risk, and sources of the n-3 polyunsaturated fat

alpha-linolenic acid, such as rapeseed or canola oil,

are cardioprotective. Replacing saturated fat with

monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat reduces

LDL-C and preserves HDL-C (109). Further, canola oil,

as part of a low-GI diet, improves glycemic control

and blood lipids in T2DM (138). Trans fatty acids in-

crease CHD risk compared with other macronutrients,

with strong evidence of adverse effects of small

amounts of trans fats on lipids (109,139) and CVD risk

(140,141).

Though total fat (142), and specifically saturated

fats, have generally been considered to be deleterious

to insulin sensitivity (143), in large cohort studies,

saturated fat is not associated with development of

T2DM, after adjustment for body mass index, total di-

etary fiber, or magnesium intake (144–149). Macronu-

trient exchange generally does not influence markers

of glucose homeostasis, though in 2 relatively large

trials, replacing saturated fat with either mono-

unsaturated fat or carbohydrate improved indices of

glucose homeostasis (150,151). Associations have been

seen between major food sources of saturated fat, such

as red and processed meat, and development of T2DM

(152,153),though dairy products, notably fermented

dairy, may be protective (154,155).

C V D .Saturated fats have not been consistently

associated with CVD in meta-analyses of cohort

studies (odds ratio [OR]: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.19)

of higher compared with lower intakes (156). How-

ever, in most of these studies the association of

high saturated fat intake largely represents repla-

cing highly refined carbohydrates. Replacing satu-

rated fat with highly refined carbohydrate is not

associated with lower CHD risk, whereas replacing

saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces CHD

risk (157,158). This benefit of polyunsaturated fat

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1597

compensation for this energy at other meals. After

adjusting for important potential confounders,

including body mass index, $1/day versus <1 SSB/

month increased T2DM by 39% (127). A meta-analysis

of 310,819 participants and 15,043 cases of T2DM re-

ported a 26% increased T2DM risk among those

consuming 1 to 2 SSB servings/day compared with

nonconsumers (128). A meta-analysis of 4 cohort

studies reported a linear association between SSB and

hypertension risk (RR) of 1.08 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.12)

per serving per day (129). The Framingham Offspring

Study reported a 22% higher incidence of hyper-

tension among those consuming $1 SSB serving/day

compared with nonconsumers (130). A potential

explanation of the SSB-T2DM association is the high

content of rapidly absorbed sugar from corn syrup,

which increases blood glucose and insulin and de

novo lipogenesis—which may contribute to pancre-

atic beta cell dysfunction and eventually T2DM (131).

In the NHANES III (National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey III) study, with 831 CVD deaths

during 163,039 person-years of follow-up, con-

sumption of $7 SSB servings/week was associated

with a 29% increased CVD mortality risk compared

with <1 serving/week (120), with no increased risk

up to 6 drinks/week. Few studies have investigated

the association between SSBs and CVD events.

Those that have, report increased CHD and stroke

risk with SSB consumption. A 2015 meta-analysis

reported an RR for incident CHD of 1.17 (95% CI:

1.10 to 1.24) per serving per day increase in

SSB consumption (129). Both the HPFS and the

NHS find an approximate 20% increased CHD risk

in the highest category of SSB consumption com-

pared with the lowest category (132,133);and, after

adjusting for dietary and nondietary cardiovascular

risk factors, a 16% increased stroke risk (134). Simi-

larly, 2 Swedish prospective cohort studies in

women and men reported a RR of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.04

FATS AND OILS. C V D r i s k f a c t o r s .Vegetable oils

that are primarily comprised of mono- (e.g., olive oil)

and polyunsaturated fatty acids appear to reduce

CHD risk, and sources of the n-3 polyunsaturated fat

alpha-linolenic acid, such as rapeseed or canola oil,

are cardioprotective. Replacing saturated fat with

monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat reduces

LDL-C and preserves HDL-C (109). Further, canola oil,

as part of a low-GI diet, improves glycemic control

and blood lipids in T2DM (138). Trans fatty acids in-

crease CHD risk compared with other macronutrients,

with strong evidence of adverse effects of small

amounts of trans fats on lipids (109,139) and CVD risk

(140,141).

Though total fat (142), and specifically saturated

fats, have generally been considered to be deleterious

to insulin sensitivity (143), in large cohort studies,

saturated fat is not associated with development of

T2DM, after adjustment for body mass index, total di-

etary fiber, or magnesium intake (144–149). Macronu-

trient exchange generally does not influence markers

of glucose homeostasis, though in 2 relatively large

trials, replacing saturated fat with either mono-

unsaturated fat or carbohydrate improved indices of

glucose homeostasis (150,151). Associations have been

seen between major food sources of saturated fat, such

as red and processed meat, and development of T2DM

(152,153),though dairy products, notably fermented

dairy, may be protective (154,155).

C V D .Saturated fats have not been consistently

associated with CVD in meta-analyses of cohort

studies (odds ratio [OR]: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.19)

of higher compared with lower intakes (156). How-

ever, in most of these studies the association of

high saturated fat intake largely represents repla-

cing highly refined carbohydrates. Replacing satu-

rated fat with highly refined carbohydrate is not

associated with lower CHD risk, whereas replacing

saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces CHD

risk (157,158). This benefit of polyunsaturated fat

J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5 Anand et al.

O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

1597

cardiac deaths and nonfatal CHD (163), whereas the

PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) RCT

found that a Mediterranean diet (50 g/day extra virgin

olive oil) reduced CVD events by 30% over a 5-year

period (164).

Palm oil is the dominant fat globally and is rela-

tively high in saturated fat. On the basis of controlled-

feeding studies examining changes in blood lipids,

replacing palm oil with unsaturated fatty acids would

be expected to lower CHD risk (109), but palm oil

would be preferred to partially hydrogenated oils

high in trans fatty acids. Few studies have directly

compared palm oil with other oils for CHD risk. One

large case-control study in Costa Rica found that

soybean oil consumption was associated with lower

acute MI risk compared with palm oil consumption

(165).

S u m m a r y o ff a t sa n d o i l s .Compared with satu-

rated fat, vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated fats

reduce the TC:HDL-C (total cholesterol:HDL-C) ratio

and CHD incidence; inclusion of n-3 fatty acids

(alpha-linolenic acid) with the vegetable oils is

important for CHD prevention. The effect of

replacing saturated fat with carbohydrate on CHD

risk appears to depend on the quality of the carbo-

hydrate. Prospective studies consistently indicate

adverse effects of trans fats on CHD. Effects of

monounsaturated fat from plant sources require

further study; extra virgin olive oil appears to re-

duce CVD.

PROTEIN SOURCES. M e a t s .Nutrients and CVD Risk

Factors. Meat is rich in protein, iron, zinc, and B

vitamins, but can also contain significant amounts

of cholesterol and saturated fatty acids, which

raise LDL-C and lower triglyceride (157). A high

red meat intake (rich in heme iron), increases

endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds in

the gastrointestinal tract that are associated with

increased epithelial proliferation, oxidative stress,

and iron-induced hypoxia signaling (166–168).

content and N-nitroso compounds, also implicated in

colorectal cancer (167). The evidence suggests that

processed meat consumption increases CHD risk,

whereas unprocessed meat consumption has a small

or no association with CHD, mainly when compared

with refined starch and sugar. Both unprocessed and

processed red meats are associated with greater CVD

risk compared with poultry, fish, or vegetable protein

sources. Both types of meat are associated with

higher T2DM risk, although gram for gram the effect

size is notably larger for processed meats.

LMIC. Data relating meat consumption to CVD risk in

LMIC is limited. A recent pooled analysis of data

from 296,721 individuals from Asian countries (i.e.,

Bangladesh, mainland China, Japan, Korea, and

Taiwan) found no association between red meat and

poultry consumption and CVD, cancer mortality, or

all-cause mortality (173). Red meat intake is generally

much lower in these areas than in HIC however, and

current consumption does not likely reflect long-

term patterns.

D a i r y .CVD Risk Factors. The consumption of dairy

products has been associated with weight loss in

small studies (174), but the overall published data

does not confirm an important effect on body weight.

However, increased low-fat dairy consumption is

associated with lower LDL-C, triglycerides, plasma

insulin, insulin resistance, waist circumference, body

mass index, possibly blood pressure; and reduced

diabetes risk (174–182). In a large meta-analysis of

cohort studies (13,000 incident cases), and the EPIC

InterAct (European Prospective Investigation into

Cancer and Nutrition) case-cohort study (12,000

incident cases), fermented dairy (i.e., yogurt,

cheese, and thick fermented milk), but not total

dairy, was inversely associated with T2DM (155,183).

In a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies,

milk consumption was inversely associated with

total CVD in a small subset of studies with few

cases, but using a larger body of data with more

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1598

PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) RCT

found that a Mediterranean diet (50 g/day extra virgin

olive oil) reduced CVD events by 30% over a 5-year

period (164).

Palm oil is the dominant fat globally and is rela-

tively high in saturated fat. On the basis of controlled-

feeding studies examining changes in blood lipids,

replacing palm oil with unsaturated fatty acids would

be expected to lower CHD risk (109), but palm oil

would be preferred to partially hydrogenated oils

high in trans fatty acids. Few studies have directly

compared palm oil with other oils for CHD risk. One

large case-control study in Costa Rica found that

soybean oil consumption was associated with lower

acute MI risk compared with palm oil consumption

(165).

S u m m a r y o ff a t sa n d o i l s .Compared with satu-

rated fat, vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated fats

reduce the TC:HDL-C (total cholesterol:HDL-C) ratio

and CHD incidence; inclusion of n-3 fatty acids

(alpha-linolenic acid) with the vegetable oils is

important for CHD prevention. The effect of

replacing saturated fat with carbohydrate on CHD

risk appears to depend on the quality of the carbo-

hydrate. Prospective studies consistently indicate

adverse effects of trans fats on CHD. Effects of

monounsaturated fat from plant sources require

further study; extra virgin olive oil appears to re-

duce CVD.

PROTEIN SOURCES. M e a t s .Nutrients and CVD Risk

Factors. Meat is rich in protein, iron, zinc, and B

vitamins, but can also contain significant amounts

of cholesterol and saturated fatty acids, which

raise LDL-C and lower triglyceride (157). A high

red meat intake (rich in heme iron), increases

endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds in

the gastrointestinal tract that are associated with

increased epithelial proliferation, oxidative stress,

and iron-induced hypoxia signaling (166–168).

content and N-nitroso compounds, also implicated in

colorectal cancer (167). The evidence suggests that

processed meat consumption increases CHD risk,

whereas unprocessed meat consumption has a small

or no association with CHD, mainly when compared

with refined starch and sugar. Both unprocessed and

processed red meats are associated with greater CVD

risk compared with poultry, fish, or vegetable protein

sources. Both types of meat are associated with

higher T2DM risk, although gram for gram the effect

size is notably larger for processed meats.

LMIC. Data relating meat consumption to CVD risk in

LMIC is limited. A recent pooled analysis of data

from 296,721 individuals from Asian countries (i.e.,

Bangladesh, mainland China, Japan, Korea, and

Taiwan) found no association between red meat and

poultry consumption and CVD, cancer mortality, or

all-cause mortality (173). Red meat intake is generally

much lower in these areas than in HIC however, and

current consumption does not likely reflect long-

term patterns.

D a i r y .CVD Risk Factors. The consumption of dairy

products has been associated with weight loss in

small studies (174), but the overall published data

does not confirm an important effect on body weight.

However, increased low-fat dairy consumption is

associated with lower LDL-C, triglycerides, plasma

insulin, insulin resistance, waist circumference, body

mass index, possibly blood pressure; and reduced

diabetes risk (174–182). In a large meta-analysis of

cohort studies (13,000 incident cases), and the EPIC

InterAct (European Prospective Investigation into

Cancer and Nutrition) case-cohort study (12,000

incident cases), fermented dairy (i.e., yogurt,

cheese, and thick fermented milk), but not total

dairy, was inversely associated with T2DM (155,183).

In a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies,

milk consumption was inversely associated with

total CVD in a small subset of studies with few

cases, but using a larger body of data with more

Anand et al. J A C C V O L . 6 6 , N O . 1 4 ,2 0 1 5

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System O C T O B E R 6 ,2 0 1 5 : 1 5 9 0 – 6 1 4

1598

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

T2DM (RR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.85) than

nonconsumers (185).

E g g .CVD Risk Factors. Eggs are a relatively in-

expensive and low-calorie source of protein, folate,

and B vitamins (186). Eggs are also a source of

dietary cholesterol (a medium egg contains approxi-

mately 225 mg of cholesterol) (187). A meta-analysis

showed that eggs increase TC, HDL-C, and TC:HDL-C

(188), but 5 RCTs subsequently reported that egg

consumption did not significantly alter these para-

meters (189–191)or endothelial function (192,193).No

RCT has tested the effect of egg consumption on CVD

events. In a meta-analysis (194) of 16 prospective cohort

studies (90,735 participants) (191), egg consumption

was not associated with overall CVD or CHD, stroke, or

CHD or stroke mortality; but was associated with T2DM.

Overall, consumption of eggs in moderation (1 egg/day)

is likely neutral for CVD. However, relative to other

protein-rich foods that lower LDL cholesterol, such as

whole grains and nuts, eggs would likely increase

CVD risk.

LMIC. Unpublished data from 3 large international

studies, PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epide-

miological Study), ONTARGET (Ongoing Telmisartan

Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global

Endpoint Trial), and INTERHEART (a global study of

risk factors for acute myocardial infarction), with

collectively 200,000 individuals and 22,000 CVD

events from regions including China, India, and Af-

rica, show that moderate egg consumption appears to

be neutral or protective against CVD. However, sig-

nificant variations exist across regions, with a benefit

of daily egg consumption in China but possible harm

in South Asia.

F i s h .CVD Risk Factors. Fish are a source of protein,

vitamin D, multiple B vitamins, essential amino

acids, and trace elements; and the long-chain

omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid and

eicosapentaenoic acid (195,196), though amounts

vary over 10-fold across seafood species. Fatty

explanations include differences in the amounts and

types of fish consumed, cooking methods, and

background fish consumption. Fifteen of the 16

cohort studies (with 1 exception) (199) were con-

ducted in North America and European countries,

where deep-frying fish is common. The DART-1 (Diet

and Reinfarction) trials, a secondary prevention trial

and DART-2, in men with stable angina, are the only

randomized trial of fish intake and CVD outcomes.

They arrive at opposite conclusions. In the DART-1

trial, fish lowered all-cause mortality and trended

toward reducing CVD events after 2 years (194). In

the DART-2 trial oily fish did not affect all-cause

mortality or CVD events after 3 to 9 years, and

increased sudden cardiac death, largely confined to

the subgroup given fish oil capsules (200). Differ-

ential behavioral change or CVD stage may explain

the discrepancy (201). Follow-up of the DART-1 trial

at 5 years also showed increased rates of CVD in the

fish/fish oil group that did not persist through the

10-year assessment (202). We know of no primary

prevention trial on fish intake and CVD outcomes,

but a meta-analysis of fish oil supplement RCTs is

neutral (203).

Low-Income Countries and HIC. Mostof the data indi-

cating that fish is protective comes from studies

in HIC (204–208). Unpublished data from 3 large