National University of Political and Administration Studies PR Report

VerifiedAdded on 2021/07/05

|22

|14028

|103

Report

AI Summary

This report, authored by Diana-Maria Cismaru and Raluca Silvia Ciochina from the National University of Political and Administration Studies (NUPSPA Bucharest), investigates the challenges public relations practitioners face in the era of digital intelligence. It highlights the need for digital skills to navigate the evolving media landscape and address diverse public audiences. The study identifies gaps in practitioners' ability to engage both traditional and digitally-savvy publics and deficiencies in current university curricula that fail to adequately integrate digital intelligence. The report examines the consequences of these gaps on PR practices and proposes directions for educational strategies to adapt to the changing demands of the field. It references previous research showing the importance of digital communication, strategic planning, and measurement skills. The authors emphasize the importance of digital literacy and the ability to grasp and reason with online abstractions, as well as the need for practitioners to understand how technology and psychology impact information sharing. The report also touches upon the merging of PR and marketing, and the skills practitioners need to develop to create integrated marketing and communication strategies.

The rise of digital intelligence: challenges for public relations education and practices

Diana-Maria Cismaru, Associate Professor, Ph.D

Raluca Silvia Ciochina, Ph. D. Student

National University of Political and Administration

Studies (NUPSPA Bucharest)

Abstract

The current global culture, built around networks of information technology which entails ease and speed of

information flow, constrains PR practitioners to develop a new form of intelligence: digital intelligence. Considering

the definition of Gardner (1993, p. ii) of intelligence as the “ability to solve problems or fashion products that are of

consequence in a particular cultural setting or community”, Adams (2004, p. 96) observed that, in the global

contemporary village, “intelligence is directly related to our ability to interact with this emerging digital

environment.” Applying social media strategies to meet a competitive market, where publics gained the power to

influence media interactions, has become one of the main requirements for PR practitioners. Yet, previous

scholarship (Tench et al., 2013) showed that the development of digital skills is rather modest for European

practitioners. Using a survey on a sample of PR practitioners and students, the paper explores two types of gaps that

practitioners have to deal with. First gap refers to the difficulty of addressing constantly to two categories of publics

(older traditional publics, and young publics with a higher level of digital skills). The second gap refers to education,

as the curricula in universities does not address to the emerging digital intelligence in an integrative way. The aim of

the pilot study is to determine the consequences of these gaps on PR practices and the directions for an educational

strategy of adaptation.

Keywords: digital intelligence, digital skills gap, public relations challenges

Introduction

Several authors have identified that public relations and communication practitioners are

currently dealing and struggling with the impact of new media and the internet on their practice

(James, 2007, Macnamara, 2010, Robson & James, 2012), and also with the lack of skilled

people who can deal with the challenges of today`s social media environment (Fitch, 2009;

Tench et al, 2013). Tench et al. (2013) found some of the core skills needed by a communicators

to face today`s dynamic, global environment: writing, critical thinking/problem solving skills,

soft skills, legislative knowledge and social media skills, which was the top area where

specialists needed to improve. The aim of this research paper is to investigate the current

challenges that public relations and communication practitioners from Romania are facing when

addressing external publics in today`s digital media environment. A second aim of the paper is to

identify some of the digital skills gaps present at the educational level, considering the emerging

new media environment.

According to research carried by the PR Academy (2013), alumni respondents identified as

their top three skills gaps: digital communications (52%), followed by strategic planning (46%),

and measurement (44%). In 2012, the European Communication Monitor (Zerfass et al., 2012)

which is the largest transnational survey on strategic communication worldwide, with 2,200

participants from 42 countries, also showed that there are gaps between the perceived importance

of digital media and the way they are actually being used by public relations professionals,

indicating the same knowledge and skills gap. In fact, some of the biggest digital challenges

identified by communication professionals are coping with the digital evolution (46%),

addressing more audiences and channels with limited resources (34%), ethics in social media,

Diana-Maria Cismaru, Associate Professor, Ph.D

Raluca Silvia Ciochina, Ph. D. Student

National University of Political and Administration

Studies (NUPSPA Bucharest)

Abstract

The current global culture, built around networks of information technology which entails ease and speed of

information flow, constrains PR practitioners to develop a new form of intelligence: digital intelligence. Considering

the definition of Gardner (1993, p. ii) of intelligence as the “ability to solve problems or fashion products that are of

consequence in a particular cultural setting or community”, Adams (2004, p. 96) observed that, in the global

contemporary village, “intelligence is directly related to our ability to interact with this emerging digital

environment.” Applying social media strategies to meet a competitive market, where publics gained the power to

influence media interactions, has become one of the main requirements for PR practitioners. Yet, previous

scholarship (Tench et al., 2013) showed that the development of digital skills is rather modest for European

practitioners. Using a survey on a sample of PR practitioners and students, the paper explores two types of gaps that

practitioners have to deal with. First gap refers to the difficulty of addressing constantly to two categories of publics

(older traditional publics, and young publics with a higher level of digital skills). The second gap refers to education,

as the curricula in universities does not address to the emerging digital intelligence in an integrative way. The aim of

the pilot study is to determine the consequences of these gaps on PR practices and the directions for an educational

strategy of adaptation.

Keywords: digital intelligence, digital skills gap, public relations challenges

Introduction

Several authors have identified that public relations and communication practitioners are

currently dealing and struggling with the impact of new media and the internet on their practice

(James, 2007, Macnamara, 2010, Robson & James, 2012), and also with the lack of skilled

people who can deal with the challenges of today`s social media environment (Fitch, 2009;

Tench et al, 2013). Tench et al. (2013) found some of the core skills needed by a communicators

to face today`s dynamic, global environment: writing, critical thinking/problem solving skills,

soft skills, legislative knowledge and social media skills, which was the top area where

specialists needed to improve. The aim of this research paper is to investigate the current

challenges that public relations and communication practitioners from Romania are facing when

addressing external publics in today`s digital media environment. A second aim of the paper is to

identify some of the digital skills gaps present at the educational level, considering the emerging

new media environment.

According to research carried by the PR Academy (2013), alumni respondents identified as

their top three skills gaps: digital communications (52%), followed by strategic planning (46%),

and measurement (44%). In 2012, the European Communication Monitor (Zerfass et al., 2012)

which is the largest transnational survey on strategic communication worldwide, with 2,200

participants from 42 countries, also showed that there are gaps between the perceived importance

of digital media and the way they are actually being used by public relations professionals,

indicating the same knowledge and skills gap. In fact, some of the biggest digital challenges

identified by communication professionals are coping with the digital evolution (46%),

addressing more audiences and channels with limited resources (34%), ethics in social media,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

but also catching up in the field of mobile applications. Therefore, communication specialists

manifest a growing interest in obtaining qualifications in these areas. The next year‟s similar

study (Zerfass et al., 2013) was conducted in 43 countries, and showed that communication

practitioners believe that there is a need to develop different strategies for different generations,

the under 30 digital native generation being more interactive (89%), and that organisations use

specific communication strategies for each generation (60%). Moreover, bloggers, consumers

and digital active employees are starting to become important tools for strategic communicators.

67% practitioners believe that online videos are important communication tools, but only 46%

implemented this tool in their organizations. As far as social media skills are concerned,

communication practitioners are looking at a slow increase from 2011, as only 29% are good at

initiating web-based dialogues with stakeholders. Also, 7 out of 10 communication practitioners

faced a communication crisis, but only few chose to use social media as instrument for dealing

with it.

Another relevant study (Parker, 2014) has found skills gaps in the UK public relations

market, comparing the demands of organizations with the skills of public relations candidates.

The survey found that, amongst other gaps, writing, social media and client services skills are

considered missing when evaluating communication practitioners. The need to keeping pace with

newest technologies and developments in the context of digital era is primordial for

communication practitioners. They now see digital communication as part of strategic planning

and recognising their shortages is a first step in addressing this issue and potentially solve it

through qualification means.

The National Academy of Sciences (1999) significantly observed that “skills with specific

applications are thus necessary but not sufficient for individuals to prosper in the information

age” (p. 11). As Resnik (2002) suggested, fostering creativity and innovation inside classrooms

can be a first step. While acquiring computer literacy is crucial, individuals also need to

internalize in-depth understanding of information technology, so as when faced with an

unexpected issue, they will be able to adapt or find alternative solutions. This represents

technological fluency – “the ability to reformulate knowledge, to express oneself creatively and

appropriately, and to produce and generate information (rather than simply to comprehend it).”

(p. 14).

As younger publics have incorporated the digital media into their lives at a more profound

level, not necessarily focusing on their utility, but rather on the experiences they provide, it is

extremely important that communication practitioners dealing with these publics enhance their

level of understanding of digital media use, noted by Buckingham (2008) as “digital literacy”.

Considering this, the paper proposes a direction to study the development of a new form of

intelligence crucial for public relations and communication practitioners: the digital intelligence.

Literature Review

Public relations practice in the online environment

Although past research evaluates the differences between roles in the public relations

profession, the practice of this profession implies various forms, especially with the current

emerging information and communication technologies which imply various levels of execution

and involvement. Many scholars have investigated the new roles and challenges that public

relations and communication practitioners are currently facing, considering the emancipation of

manifest a growing interest in obtaining qualifications in these areas. The next year‟s similar

study (Zerfass et al., 2013) was conducted in 43 countries, and showed that communication

practitioners believe that there is a need to develop different strategies for different generations,

the under 30 digital native generation being more interactive (89%), and that organisations use

specific communication strategies for each generation (60%). Moreover, bloggers, consumers

and digital active employees are starting to become important tools for strategic communicators.

67% practitioners believe that online videos are important communication tools, but only 46%

implemented this tool in their organizations. As far as social media skills are concerned,

communication practitioners are looking at a slow increase from 2011, as only 29% are good at

initiating web-based dialogues with stakeholders. Also, 7 out of 10 communication practitioners

faced a communication crisis, but only few chose to use social media as instrument for dealing

with it.

Another relevant study (Parker, 2014) has found skills gaps in the UK public relations

market, comparing the demands of organizations with the skills of public relations candidates.

The survey found that, amongst other gaps, writing, social media and client services skills are

considered missing when evaluating communication practitioners. The need to keeping pace with

newest technologies and developments in the context of digital era is primordial for

communication practitioners. They now see digital communication as part of strategic planning

and recognising their shortages is a first step in addressing this issue and potentially solve it

through qualification means.

The National Academy of Sciences (1999) significantly observed that “skills with specific

applications are thus necessary but not sufficient for individuals to prosper in the information

age” (p. 11). As Resnik (2002) suggested, fostering creativity and innovation inside classrooms

can be a first step. While acquiring computer literacy is crucial, individuals also need to

internalize in-depth understanding of information technology, so as when faced with an

unexpected issue, they will be able to adapt or find alternative solutions. This represents

technological fluency – “the ability to reformulate knowledge, to express oneself creatively and

appropriately, and to produce and generate information (rather than simply to comprehend it).”

(p. 14).

As younger publics have incorporated the digital media into their lives at a more profound

level, not necessarily focusing on their utility, but rather on the experiences they provide, it is

extremely important that communication practitioners dealing with these publics enhance their

level of understanding of digital media use, noted by Buckingham (2008) as “digital literacy”.

Considering this, the paper proposes a direction to study the development of a new form of

intelligence crucial for public relations and communication practitioners: the digital intelligence.

Literature Review

Public relations practice in the online environment

Although past research evaluates the differences between roles in the public relations

profession, the practice of this profession implies various forms, especially with the current

emerging information and communication technologies which imply various levels of execution

and involvement. Many scholars have investigated the new roles and challenges that public

relations and communication practitioners are currently facing, considering the emancipation of

information and communication technologies, especially social media (e.g. Macnamara, 2011;

Lee, 2013; Wigley & Zhang, 2011).

The contemporary digital culture, based on hyper-connectivity and global access to

computers, smartphones and other devices which allow Internet connection, has changed the

realm of daily interaction as public relations and communication professionals knew it in the

past. Information availability, from various sources, either institutionalized or not, can cause both

benefits and problems for communication practitioners. Rumors can spread easily and the

dynamics of misinformation propagation and attempts to deceive users are still at infancy levels

(Ratkiewicz et al, 2011); false information diffusion can cause organizations or public actors

damages. Furthermore, communication practitioners need to be able to face competitors`

unethical practices, such as attacks (Herring et al., 2002), which are meant to diffuse the

attention from one topic and turn discussions into unproductive debates.

John Bell, a renowned digital innovation specialist who led the successful Social@Ogilvy

(the best digital consultancy in the world), argued in 2008 that the public relations and marketing

practice are merging together, and, as a consequence, the public relations and communication

practitioner is forced to develop new skills, and more particularly to: create integrated marketing

and communication strategy, monitor the online space, implement advanced search engine

optimization programs, develop relationships with influencers, manage communities and

participate in conversations, start using new technology in their own lives, start applying new

engagement metrics, test and evaluate pilot programs, focus on training, work on content strategy

and apply digital crisis management. Moreover, Bell (2008) emphasized that public relations

practitioners should develop their ability to identify and engage influencers and understand how

technology and psychology impact individuals who share information.

Among other public relations and communication work categories, Sha (2011) defined social

media relations as activities which included “utilizing Web-based social networks, developing

social media strategies for communication efforts, producing in-house or client blogs, apprising

clients on how to use social media strategies as delivery channels for communication efforts,

SEO, blogger relations, etc.” (p. 188-189). According to Sha (2011), the top KSAs (knowledge,

skills and abilities) used by communication practitioners in a typical week in 2010 were: use of

information technology and new media channels (91%), management skills and issues, media

relations, research, planning, implementation and evaluation of PR programs, among others.

Towards a Definition of Digital Intelligence

Although many scholars have addressed the importance of internet skills and proposed ways

of measuring them (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2010; Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk, 2005), there is still

a need to investigate what specific digital skills communication practitioners should acquire in

today`s digital era (and not only what they perceive to be important) and whether future

practitioners are prepared to meet the challenges of the online environment, considering their

levels of digital skills nowadays.

As van Deursen and van Dijk (2010) noted, considering people`s “increasing dependence on

information, internet skills should be considered as a vital resource in contemporary society” (p.

893). Stemming from Gardner`s (1993) intelligence classification scheme, who defined

intelligence as the “ability to solve problems or fashion products that are of consequence in a

particular cultural setting or community” (p.15), Adams (2004) proposed the emergence of a new

form of intelligence: digital intelligence. According to Adams, digital intelligence “is a response

Lee, 2013; Wigley & Zhang, 2011).

The contemporary digital culture, based on hyper-connectivity and global access to

computers, smartphones and other devices which allow Internet connection, has changed the

realm of daily interaction as public relations and communication professionals knew it in the

past. Information availability, from various sources, either institutionalized or not, can cause both

benefits and problems for communication practitioners. Rumors can spread easily and the

dynamics of misinformation propagation and attempts to deceive users are still at infancy levels

(Ratkiewicz et al, 2011); false information diffusion can cause organizations or public actors

damages. Furthermore, communication practitioners need to be able to face competitors`

unethical practices, such as attacks (Herring et al., 2002), which are meant to diffuse the

attention from one topic and turn discussions into unproductive debates.

John Bell, a renowned digital innovation specialist who led the successful Social@Ogilvy

(the best digital consultancy in the world), argued in 2008 that the public relations and marketing

practice are merging together, and, as a consequence, the public relations and communication

practitioner is forced to develop new skills, and more particularly to: create integrated marketing

and communication strategy, monitor the online space, implement advanced search engine

optimization programs, develop relationships with influencers, manage communities and

participate in conversations, start using new technology in their own lives, start applying new

engagement metrics, test and evaluate pilot programs, focus on training, work on content strategy

and apply digital crisis management. Moreover, Bell (2008) emphasized that public relations

practitioners should develop their ability to identify and engage influencers and understand how

technology and psychology impact individuals who share information.

Among other public relations and communication work categories, Sha (2011) defined social

media relations as activities which included “utilizing Web-based social networks, developing

social media strategies for communication efforts, producing in-house or client blogs, apprising

clients on how to use social media strategies as delivery channels for communication efforts,

SEO, blogger relations, etc.” (p. 188-189). According to Sha (2011), the top KSAs (knowledge,

skills and abilities) used by communication practitioners in a typical week in 2010 were: use of

information technology and new media channels (91%), management skills and issues, media

relations, research, planning, implementation and evaluation of PR programs, among others.

Towards a Definition of Digital Intelligence

Although many scholars have addressed the importance of internet skills and proposed ways

of measuring them (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2010; Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk, 2005), there is still

a need to investigate what specific digital skills communication practitioners should acquire in

today`s digital era (and not only what they perceive to be important) and whether future

practitioners are prepared to meet the challenges of the online environment, considering their

levels of digital skills nowadays.

As van Deursen and van Dijk (2010) noted, considering people`s “increasing dependence on

information, internet skills should be considered as a vital resource in contemporary society” (p.

893). Stemming from Gardner`s (1993) intelligence classification scheme, who defined

intelligence as the “ability to solve problems or fashion products that are of consequence in a

particular cultural setting or community” (p.15), Adams (2004) proposed the emergence of a new

form of intelligence: digital intelligence. According to Adams, digital intelligence “is a response

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

to the cultural change brought about by digital technologies and takes into account the skills and

talents possessed by the “symbol analysts” and “masters of chance” recently recognized in

Gardner`s (1999) latest book” (p. 94). According to Gardner, “a symbol analyst can sit for hours

in front of a string of numbers and words, usually displayed on a computer screen, and readily

discern meaning”, making future projections, while “a master of change readily acquires new

information, solves problems, forms “weak ties” with mobile and highly dispersed people, and

adjusts easily to changing circumstances” (1999, p. 2).

Considering Schmidt`s and Hunter`s (2000) definition of general intelligence, which refers

to the ability to learn and solve problems, we conceptualize digital intelligence as the ability to

grasp and reason correctly with digital/online abstractions (online concepts) and solve online

problems (technological, informational and communicational).

As “each intelligence must have an identifiable core operation or set of operations […] (and)

is activated or „triggered‟ by certain kinds of internally or externally presented information”

(Gardner, 1993, p. 16), Adams (2004) observes that, considering information clusters and lack of

linearity, “those with the ability to understand and interact with this digital information to

arrange, manipulate, and display it according to their perceptions possess yet another intelligence

- an intelligence made up of components of the other intelligences” (p. 95). In 1999, Gardner

developed a newer version of intelligence definition stating that it represents a “biopsychological

potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or

create products that are of value in a culture” (p. 33-34). Moreover, as Adams observers, our

ability to deal with today`s challenges depends on our intellectual ability to solve problems and

interact in a digital environment. Rapid information diffusion and dissemination has changed the

way we process information, and the way communication means, particularly new media, are

expanding, individuals need to adapt as well, in a setting where “technological advancements

have allowed fluency across all cultures and at the same time have rapidly increased our ability

for information gathering, storage, and retrieval” (p. 94).

As Gardner (1999) suggested after assessing the ways his multiple intelligence theory can

be applied in schools and education in general, specific techniques need to be applied and goals

to be established, and then a measurement of how successful implementation has been in the end.

The author believed that education should combine various resources which imply multiple

intelligences usage, thus creating a complete and challenging experience for the ones studying.

Resnik (2002) introduced the notion of digital fluency and emphasized that, even though

individuals are taught how to look up information on the web and use specific platforms, they are

not fluent with technology, as they need to know how to construct things of significance with the

tools they use, not only understand how they work. He furthermore foresaw that “in the years

ahead, digital fluency will become a prerequisite for obtaining jobs, participating meaningfully in

society, and learning throughout a lifetime” (p. 33). While the digital divide gap is currently

shifting from internet access and opportunities to interact with technology to digital fluency gap

(Resnik, 2002), it is becoming more and more relevant to develop the right set of skills and

knowledge to overcome these issues, from their infancy levels, starting with university programs.

Livingstone (2004) asserts that “as people engage with a diversity of ICTs, we must develop an

account of literacies in the plural, defined through their relations with different media rather than

defined independently of them” (p. 7). Resnik (2002) proposed a more entrepreneurial approach

to learning, especially as information is available and learning can become individualized:

“Students can become more active and independent learners, with the teacher serving as a

consultant, not chief executive” (p. 36).

talents possessed by the “symbol analysts” and “masters of chance” recently recognized in

Gardner`s (1999) latest book” (p. 94). According to Gardner, “a symbol analyst can sit for hours

in front of a string of numbers and words, usually displayed on a computer screen, and readily

discern meaning”, making future projections, while “a master of change readily acquires new

information, solves problems, forms “weak ties” with mobile and highly dispersed people, and

adjusts easily to changing circumstances” (1999, p. 2).

Considering Schmidt`s and Hunter`s (2000) definition of general intelligence, which refers

to the ability to learn and solve problems, we conceptualize digital intelligence as the ability to

grasp and reason correctly with digital/online abstractions (online concepts) and solve online

problems (technological, informational and communicational).

As “each intelligence must have an identifiable core operation or set of operations […] (and)

is activated or „triggered‟ by certain kinds of internally or externally presented information”

(Gardner, 1993, p. 16), Adams (2004) observes that, considering information clusters and lack of

linearity, “those with the ability to understand and interact with this digital information to

arrange, manipulate, and display it according to their perceptions possess yet another intelligence

- an intelligence made up of components of the other intelligences” (p. 95). In 1999, Gardner

developed a newer version of intelligence definition stating that it represents a “biopsychological

potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or

create products that are of value in a culture” (p. 33-34). Moreover, as Adams observers, our

ability to deal with today`s challenges depends on our intellectual ability to solve problems and

interact in a digital environment. Rapid information diffusion and dissemination has changed the

way we process information, and the way communication means, particularly new media, are

expanding, individuals need to adapt as well, in a setting where “technological advancements

have allowed fluency across all cultures and at the same time have rapidly increased our ability

for information gathering, storage, and retrieval” (p. 94).

As Gardner (1999) suggested after assessing the ways his multiple intelligence theory can

be applied in schools and education in general, specific techniques need to be applied and goals

to be established, and then a measurement of how successful implementation has been in the end.

The author believed that education should combine various resources which imply multiple

intelligences usage, thus creating a complete and challenging experience for the ones studying.

Resnik (2002) introduced the notion of digital fluency and emphasized that, even though

individuals are taught how to look up information on the web and use specific platforms, they are

not fluent with technology, as they need to know how to construct things of significance with the

tools they use, not only understand how they work. He furthermore foresaw that “in the years

ahead, digital fluency will become a prerequisite for obtaining jobs, participating meaningfully in

society, and learning throughout a lifetime” (p. 33). While the digital divide gap is currently

shifting from internet access and opportunities to interact with technology to digital fluency gap

(Resnik, 2002), it is becoming more and more relevant to develop the right set of skills and

knowledge to overcome these issues, from their infancy levels, starting with university programs.

Livingstone (2004) asserts that “as people engage with a diversity of ICTs, we must develop an

account of literacies in the plural, defined through their relations with different media rather than

defined independently of them” (p. 7). Resnik (2002) proposed a more entrepreneurial approach

to learning, especially as information is available and learning can become individualized:

“Students can become more active and independent learners, with the teacher serving as a

consultant, not chief executive” (p. 36).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

There are scholars who observed how some individuals` online skills are more developed

than others` (Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk, 2005; 2006) and this phenomena was introduced as

second level digital divide, a form of exclusion derived from how information and

communication technologies are used. Hargittai (2002) identified differences in how people find

information online and that they engage in various types of web surfing, with younger people

displaying more agility in using search engines. In 2008, taking further research into the

phenomena of second level digital divide, Hargittai identified that there are differences regarding

the levels of skills of young adults as well, and those who benefit from higher education and

access to various sources use the Web for activities, “that may lead to more informed political

participation (seeking political or government information online), help with one`s career

advancement (exploring career or job opportunities on the Web), or consulting information about

financial and health services.” (p. 607)

In Buckingham`s (2008) view, definitions of digital literacy previously provided by other

scholars are too narrow, referring only to the operational skills developed for using software and

hardware, or “in performing basic information retrieval tasks” (p. 60). Beyond the instrumental

or functional literacy of using digital media, there are other abilities which need to be addressed:

the strategic ability to use information critically, evaluate information resources properly,

language, production and audience understanding of the online environment (Buckingham,

2008).

According to van Dijk (2006), Hargittai is the only researcher who observed information

skills in their depth. Further, Van Dijk (2006) introduced the notion of digital skills together with

Steyaert (2000) as operational and, respectively, instrumental. In an earlier paper (Van Dijk,

2005) the author distinguished between strategic skills, which refer to the ability to use

technology for reaching particular objectives and for building one`s social status, information

skills, which refer to finding, selecting and processing information using various sources and

operational skills, which are more practical and refer to the ability to work with computer

software are hardware (and are the most basic skills). Moreover, van Dijk stressed that

individuals usually learn computer skills by practice, without the formal help of education; but

education is still required, especially as people need to understand the effects of their interaction,

either implicit or explicit, with information and communication technologies. Strategic digital

skills, on the other hand, need more in-depth research as they imply “making a transition to the

actual usage of digital media and how this usage may lead to more or less participation in several

fields of society “(van Dijk, 2006, p. 229). Based on earlier academic findings, Van Deursen and

van Dijk (2009, p.2) suggested a framework for adequately measuring four types of digital skills:

operational skills, information skills, formal skills (used to handle special structures like menus

and hyperlinks) and strategic skills.

Also, in building a quantitative research instrument are useful the findings of Eshet (2012),

who identified six digital skills for effective performance in the digital era: photo-visual,

branching, reproduction, information, socio-emotional and real-time thinking skills. The latter

has been introduced as in today`s “digital era, with the central role of fast computers, multimedia

environments, and devices that can process and present information in real-time and at high

speed, real-time thinking has become a critical skill” (p. 272). Social emotionally skilled

individuals show more willingness to share information with others, can evaluate it and are “able

to design knowledge through virtual collaboration” (p. 271) and understand the rules for

communicating in the online space, aided by reproduction skills, which refer to rearranging

information and content to create new meanings, while information skills imply critically

than others` (Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk, 2005; 2006) and this phenomena was introduced as

second level digital divide, a form of exclusion derived from how information and

communication technologies are used. Hargittai (2002) identified differences in how people find

information online and that they engage in various types of web surfing, with younger people

displaying more agility in using search engines. In 2008, taking further research into the

phenomena of second level digital divide, Hargittai identified that there are differences regarding

the levels of skills of young adults as well, and those who benefit from higher education and

access to various sources use the Web for activities, “that may lead to more informed political

participation (seeking political or government information online), help with one`s career

advancement (exploring career or job opportunities on the Web), or consulting information about

financial and health services.” (p. 607)

In Buckingham`s (2008) view, definitions of digital literacy previously provided by other

scholars are too narrow, referring only to the operational skills developed for using software and

hardware, or “in performing basic information retrieval tasks” (p. 60). Beyond the instrumental

or functional literacy of using digital media, there are other abilities which need to be addressed:

the strategic ability to use information critically, evaluate information resources properly,

language, production and audience understanding of the online environment (Buckingham,

2008).

According to van Dijk (2006), Hargittai is the only researcher who observed information

skills in their depth. Further, Van Dijk (2006) introduced the notion of digital skills together with

Steyaert (2000) as operational and, respectively, instrumental. In an earlier paper (Van Dijk,

2005) the author distinguished between strategic skills, which refer to the ability to use

technology for reaching particular objectives and for building one`s social status, information

skills, which refer to finding, selecting and processing information using various sources and

operational skills, which are more practical and refer to the ability to work with computer

software are hardware (and are the most basic skills). Moreover, van Dijk stressed that

individuals usually learn computer skills by practice, without the formal help of education; but

education is still required, especially as people need to understand the effects of their interaction,

either implicit or explicit, with information and communication technologies. Strategic digital

skills, on the other hand, need more in-depth research as they imply “making a transition to the

actual usage of digital media and how this usage may lead to more or less participation in several

fields of society “(van Dijk, 2006, p. 229). Based on earlier academic findings, Van Deursen and

van Dijk (2009, p.2) suggested a framework for adequately measuring four types of digital skills:

operational skills, information skills, formal skills (used to handle special structures like menus

and hyperlinks) and strategic skills.

Also, in building a quantitative research instrument are useful the findings of Eshet (2012),

who identified six digital skills for effective performance in the digital era: photo-visual,

branching, reproduction, information, socio-emotional and real-time thinking skills. The latter

has been introduced as in today`s “digital era, with the central role of fast computers, multimedia

environments, and devices that can process and present information in real-time and at high

speed, real-time thinking has become a critical skill” (p. 272). Social emotionally skilled

individuals show more willingness to share information with others, can evaluate it and are “able

to design knowledge through virtual collaboration” (p. 271) and understand the rules for

communicating in the online space, aided by reproduction skills, which refer to rearranging

information and content to create new meanings, while information skills imply critically

evaluating and assessing information. The branching digital skills, or hypermedia skills, on the

other hand, involve a sense of orientation, the ability to create mental models and concept maps

and other forms of abstract representation, and the photo-visual skill helps users “to intuitively

and freely „read‟ and understand instructions and messages that are presented in a visual

graphical form” (p. 268).

For answering the first research question, we developed a survey and we sought to identify

the level of operational, strategic and fluency skills developed by public relations and

communication students for dealing with the current digital online environment. Concordant with

Hargittai`s (2008) view, the online behaviour can be a reflection of individual`s online skills, we

introduced items to the questionnaire, where the participants were able to rate their abilities on

new media platforms, particularly social media.

Research questions

Considering the theoretical framework we developed, the aim of this paper is to address the

following research questions:

RQ1: Which type of digital skills (operational, information, strategic or of digital fluency)

are more developed among students in public relations?

RQ2: What limitations and opportunities are PR practitioners facing while engaging with

publics in the digital landscape, and what particular skills are necessary to deal with challenges?

RQ3: What aspects in academic education in public relations should be adapted and

emphasized in order to form the necessary skills for managing communication in the new digital

environment?

Methodology

We applied a questionnaire investigating online behaviours and the degree of development of

digital skills (operational, informational, strategic and of digital fluency) of students engaged in

public relations and communication education, in two different universities (University of

Bucharest, from Romania, and National University of Political Studies and Public

Administration, Bucharest, Romania). The respondents were either undergraduates or graduates

enrolled in a master program. The questionnaire was applied to students in communication and

public relations for two reasons: one of them is that they are the future specialists in

communication and public relations, and the second was that, due to their age, they are a sample

of the “digitally intelligent” new publics.

The questionnaire was delivered to students in March, 2014. A convenience sample was used

and it consisted of 100 participants who were required to fill in the questionnaires as accurately

as possible. 98 students submitted valid questionnaires, 83 of which were females. The majority

of students (n=88) were aged between 20 and 25 years old, most of them being students (n=67),

and almost one third, employed.

For finding out the perception of the challenges and requirements of the social media

environment among practitioners, and for identifying their online behavior and activities related

to their job roles, we chose to conduct a more in-depth analysis, by using a qualitative method,

the interview. We chose a convenience sample for this pilot study, and, as such, the participants

belonged to various industries and had different job roles as public relations and communication

practitioners, but all of them had previous or current professional engagement with the online

other hand, involve a sense of orientation, the ability to create mental models and concept maps

and other forms of abstract representation, and the photo-visual skill helps users “to intuitively

and freely „read‟ and understand instructions and messages that are presented in a visual

graphical form” (p. 268).

For answering the first research question, we developed a survey and we sought to identify

the level of operational, strategic and fluency skills developed by public relations and

communication students for dealing with the current digital online environment. Concordant with

Hargittai`s (2008) view, the online behaviour can be a reflection of individual`s online skills, we

introduced items to the questionnaire, where the participants were able to rate their abilities on

new media platforms, particularly social media.

Research questions

Considering the theoretical framework we developed, the aim of this paper is to address the

following research questions:

RQ1: Which type of digital skills (operational, information, strategic or of digital fluency)

are more developed among students in public relations?

RQ2: What limitations and opportunities are PR practitioners facing while engaging with

publics in the digital landscape, and what particular skills are necessary to deal with challenges?

RQ3: What aspects in academic education in public relations should be adapted and

emphasized in order to form the necessary skills for managing communication in the new digital

environment?

Methodology

We applied a questionnaire investigating online behaviours and the degree of development of

digital skills (operational, informational, strategic and of digital fluency) of students engaged in

public relations and communication education, in two different universities (University of

Bucharest, from Romania, and National University of Political Studies and Public

Administration, Bucharest, Romania). The respondents were either undergraduates or graduates

enrolled in a master program. The questionnaire was applied to students in communication and

public relations for two reasons: one of them is that they are the future specialists in

communication and public relations, and the second was that, due to their age, they are a sample

of the “digitally intelligent” new publics.

The questionnaire was delivered to students in March, 2014. A convenience sample was used

and it consisted of 100 participants who were required to fill in the questionnaires as accurately

as possible. 98 students submitted valid questionnaires, 83 of which were females. The majority

of students (n=88) were aged between 20 and 25 years old, most of them being students (n=67),

and almost one third, employed.

For finding out the perception of the challenges and requirements of the social media

environment among practitioners, and for identifying their online behavior and activities related

to their job roles, we chose to conduct a more in-depth analysis, by using a qualitative method,

the interview. We chose a convenience sample for this pilot study, and, as such, the participants

belonged to various industries and had different job roles as public relations and communication

practitioners, but all of them had previous or current professional engagement with the online

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

environment. They were either practitioners employed in social and digital management roles, or

consultants from this field. First, we approached them via email and explained the purposes of

our research and the reason why we consider them eligible for the interview. After accepting, we

established Skype meetings, as many did not have the time for a face-to-face interview.

Consequently, we interviewed 20 public relations and communication practitioners dealing with

the online environment. The sample consisted of: 3 communication professionals from the

political industry, 6 online communication specialists working in a public relations and online

marketing agency, and 11 communication specialists working for a particular client/organization.

Their experience with the online environment is not homogenous, yet the current online

environment poses similar challenges, as we will see from interview analysis.

Research instruments

a) The questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed for assessing the online behaviour

and attitudes, the degree of development of digital skills and the different digital skills that

students possess.

Firstly, we enquired what digital platforms public relations and communication students use

for operational purposes, specifically if they use mobile phones, laptops or notebooks, tablets or

dvd/ipods for variate activities (visiting sites, reading and sending emails, reading press, giving

likes and shares, making comments, accepting connection requests, being able to buy items and

pay bills, listening to music, watching videos and movies and playing online games). Then, we

inserted items for self-evaluation of operational skills, which included orientation, photo-visual

and reproduction skills. As such, we enquired about the familiarity with the following items:

tagging, using hyperlinks and bookmarking websites, and by asking participants whether they are

able to generate their profiles in online social networks and to edit attractive content materials

and to make technical improvements to blog or Facebook account, use monitoring tools for

online channels, and even to generate and design a blog entirely. We also asked our participants

the time spent on adapting to new interfaces, either for mobile or online platforms in general.

In order to assess information skills, which include critically assessing information, we

developed items inquiring about the time spent to find necessary information, and familiarity

with items like timeline, hashtag, mentions. We also asked participants to refer to their attitude

towards the degree to which they believe information is reliable after it is found on several online

channels, whether they acknowledge the credibility of the information if it is coming from a

friend, and whether information overload is too much to handle when engaging in social media

communication. Moreover, we asked the participants to rate how quickly they can find the best

information available for homework and exams online.

As public relations and communication students need to understand and critically assess

social media opportunities and strengths for dealing with future challenges, we introduced

strategic social media skills, which imply the individuals` ability to take advantage of social

media and reach specific goals. We sought to identify what social media students use for both

personal and education-related purposes: for spending free time, for entertainment, for keeping

up with what friends are doing, for receiving trusted information and real time information, for

finding out professional opportunities, for seeing Power-Point presentations, and for accessing

visual information. Also, we specifically enquired what types of actions students take on

Facebook, Twitter, You Tube, Slide Share, Linked In, and blogs: whether they update their

profiles, give likes and comments, see videos and photos, share useful information with friends,

write statuses or postings, and upload presentations, videos or prints.

consultants from this field. First, we approached them via email and explained the purposes of

our research and the reason why we consider them eligible for the interview. After accepting, we

established Skype meetings, as many did not have the time for a face-to-face interview.

Consequently, we interviewed 20 public relations and communication practitioners dealing with

the online environment. The sample consisted of: 3 communication professionals from the

political industry, 6 online communication specialists working in a public relations and online

marketing agency, and 11 communication specialists working for a particular client/organization.

Their experience with the online environment is not homogenous, yet the current online

environment poses similar challenges, as we will see from interview analysis.

Research instruments

a) The questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed for assessing the online behaviour

and attitudes, the degree of development of digital skills and the different digital skills that

students possess.

Firstly, we enquired what digital platforms public relations and communication students use

for operational purposes, specifically if they use mobile phones, laptops or notebooks, tablets or

dvd/ipods for variate activities (visiting sites, reading and sending emails, reading press, giving

likes and shares, making comments, accepting connection requests, being able to buy items and

pay bills, listening to music, watching videos and movies and playing online games). Then, we

inserted items for self-evaluation of operational skills, which included orientation, photo-visual

and reproduction skills. As such, we enquired about the familiarity with the following items:

tagging, using hyperlinks and bookmarking websites, and by asking participants whether they are

able to generate their profiles in online social networks and to edit attractive content materials

and to make technical improvements to blog or Facebook account, use monitoring tools for

online channels, and even to generate and design a blog entirely. We also asked our participants

the time spent on adapting to new interfaces, either for mobile or online platforms in general.

In order to assess information skills, which include critically assessing information, we

developed items inquiring about the time spent to find necessary information, and familiarity

with items like timeline, hashtag, mentions. We also asked participants to refer to their attitude

towards the degree to which they believe information is reliable after it is found on several online

channels, whether they acknowledge the credibility of the information if it is coming from a

friend, and whether information overload is too much to handle when engaging in social media

communication. Moreover, we asked the participants to rate how quickly they can find the best

information available for homework and exams online.

As public relations and communication students need to understand and critically assess

social media opportunities and strengths for dealing with future challenges, we introduced

strategic social media skills, which imply the individuals` ability to take advantage of social

media and reach specific goals. We sought to identify what social media students use for both

personal and education-related purposes: for spending free time, for entertainment, for keeping

up with what friends are doing, for receiving trusted information and real time information, for

finding out professional opportunities, for seeing Power-Point presentations, and for accessing

visual information. Also, we specifically enquired what types of actions students take on

Facebook, Twitter, You Tube, Slide Share, Linked In, and blogs: whether they update their

profiles, give likes and comments, see videos and photos, share useful information with friends,

write statuses or postings, and upload presentations, videos or prints.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

We also included digital fluency skills, which also imply socio-emotional involvement and

real-time thinking skills: ability to understand that information cannot be controlled in social

media after it became available to users, or dealing with criticism or negative feedback. Also,

items assessing digital fluency skills included: ability to understand when someone has evil

intentions in an online conversation, rules of acceptable behaviour in an online setting, coping

with large volumes of information from a variety of social channels in the same time, engaging

in conversations on different platforms with more than 3 people in the same time.

We used descriptive statistical analysis for identifying some of the items, aligned with the

way we developed our research instrument. We also included Likert scales and analysed them as

ordinal level data, conducting mean analysis for each item investigated. Likert scales were

mostly used for self-assessment of familiarity with different online behaviours, attitudes or social

media channels.

In order to compare the four type of digital skills, the variables have been recomposed (for

each of the four categories of skills, seven variables were introduced in order to generate a

composed variable). Some variables needed recoding for being correctly introduced in the

composed variable (for example, the “time needed to find an information” was recoded). Finally,

an entire recoding by using weighting was applied for the third category, strategic skills, since

the frequencies were not constructed on the same ordinal scale, from 1 to 5.

b) The interview guide was structured and consisted in fourteen questions. The discussion

started, in the same manner as the questionnaire, with a general inquiry about the number and

type of digital devices used, the time spent on internet in professional/personal aims, the time to

get accustomed with a device or for gathering internet information. The next set of questions

identified the differentiated use of different social media. A special place was given to the

discussion of advantages or disadvantages (or limitations or challenges) determined by the social

media development. The next aspect in discussion was the difference in approaching mature and

young publics. The last sequence of questions was dedicated to the topic of education in public

relations and to the competencies needed to be developed to young specialists in order to cope

with the new digital environment.

Results of the questionnaire survey

The introductory part of the questionnaire presented general questions regarding the

possession of devices, time spent on social media and association of devices with specific

actions.

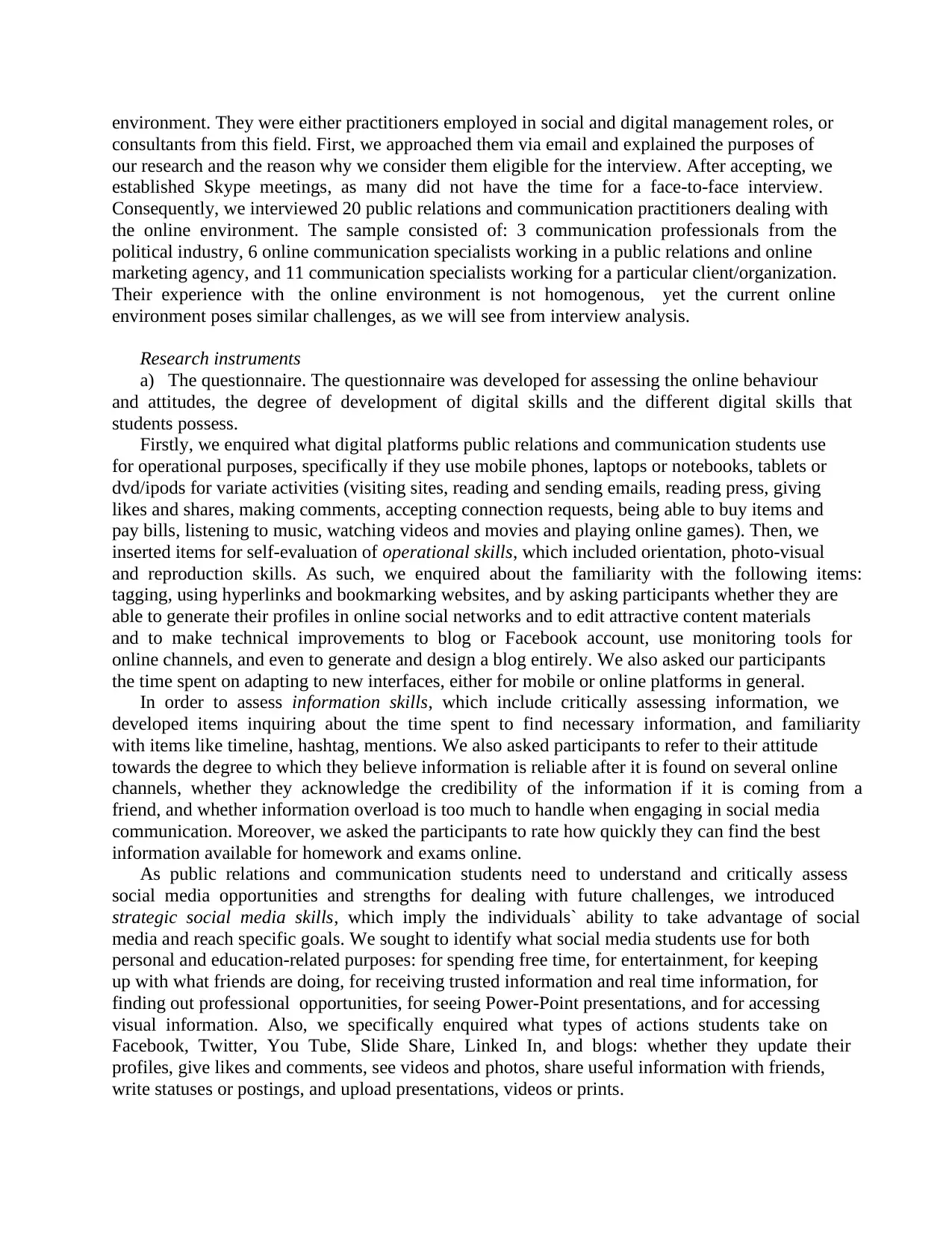

Even though most students had one mobile phone (n=76) and one laptop or notebook (n=86),

almost a quarter had 2 mobile phones at their disposal (n=20), and only 35 students owned a

tablet. Students mostly use laptops or notebooks for looking up information (n=63), visit sites

(n=74), read and send emails (n=67), read press (n=58), buy items (n=80), pay bills (n=73),

watch videos and movies (n=76). However, when more social online activities are involved,

results appear to me more distributed, as they show a balance between mobile phones and

laptops/notebook use, for the following: giving likes and shares (35% vs. 37%), making

comments (33% vs. 42%), accepting connection requests (33% vs. 42%), engaging in online

conversations (34% vs. 43%), and also for listening to music (28% vs. 31%) (See Graph 1).

As far as social media accounts are concerned, results showed that Facebook and You Tube

were the most preferred by students: 99% have a Facebook account, 82% have a You Tube

real-time thinking skills: ability to understand that information cannot be controlled in social

media after it became available to users, or dealing with criticism or negative feedback. Also,

items assessing digital fluency skills included: ability to understand when someone has evil

intentions in an online conversation, rules of acceptable behaviour in an online setting, coping

with large volumes of information from a variety of social channels in the same time, engaging

in conversations on different platforms with more than 3 people in the same time.

We used descriptive statistical analysis for identifying some of the items, aligned with the

way we developed our research instrument. We also included Likert scales and analysed them as

ordinal level data, conducting mean analysis for each item investigated. Likert scales were

mostly used for self-assessment of familiarity with different online behaviours, attitudes or social

media channels.

In order to compare the four type of digital skills, the variables have been recomposed (for

each of the four categories of skills, seven variables were introduced in order to generate a

composed variable). Some variables needed recoding for being correctly introduced in the

composed variable (for example, the “time needed to find an information” was recoded). Finally,

an entire recoding by using weighting was applied for the third category, strategic skills, since

the frequencies were not constructed on the same ordinal scale, from 1 to 5.

b) The interview guide was structured and consisted in fourteen questions. The discussion

started, in the same manner as the questionnaire, with a general inquiry about the number and

type of digital devices used, the time spent on internet in professional/personal aims, the time to

get accustomed with a device or for gathering internet information. The next set of questions

identified the differentiated use of different social media. A special place was given to the

discussion of advantages or disadvantages (or limitations or challenges) determined by the social

media development. The next aspect in discussion was the difference in approaching mature and

young publics. The last sequence of questions was dedicated to the topic of education in public

relations and to the competencies needed to be developed to young specialists in order to cope

with the new digital environment.

Results of the questionnaire survey

The introductory part of the questionnaire presented general questions regarding the

possession of devices, time spent on social media and association of devices with specific

actions.

Even though most students had one mobile phone (n=76) and one laptop or notebook (n=86),

almost a quarter had 2 mobile phones at their disposal (n=20), and only 35 students owned a

tablet. Students mostly use laptops or notebooks for looking up information (n=63), visit sites

(n=74), read and send emails (n=67), read press (n=58), buy items (n=80), pay bills (n=73),

watch videos and movies (n=76). However, when more social online activities are involved,

results appear to me more distributed, as they show a balance between mobile phones and

laptops/notebook use, for the following: giving likes and shares (35% vs. 37%), making

comments (33% vs. 42%), accepting connection requests (33% vs. 42%), engaging in online

conversations (34% vs. 43%), and also for listening to music (28% vs. 31%) (See Graph 1).

As far as social media accounts are concerned, results showed that Facebook and You Tube

were the most preferred by students: 99% have a Facebook account, 82% have a You Tube

account, 34% have Twitter and Linked In accounts, 43% have an Instagram account, and 32%

have a Pinterest account. Slide Share (10%), Wordpress (21%) and Blogger (18%) showed low

results in this sense. The respondents were asked to rate their daily use of the platforms, and it

appears that the search engine Google and Facebook are the main options for daily use, followed

by You Tube and Gmail, as secondary or third options available.

Graph 1. Balance between mobile phones and laptops use for social media actions

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Likes/shares Comments Connections Online

conversation

Listen music

Mobile phones

Laptops/notebooks

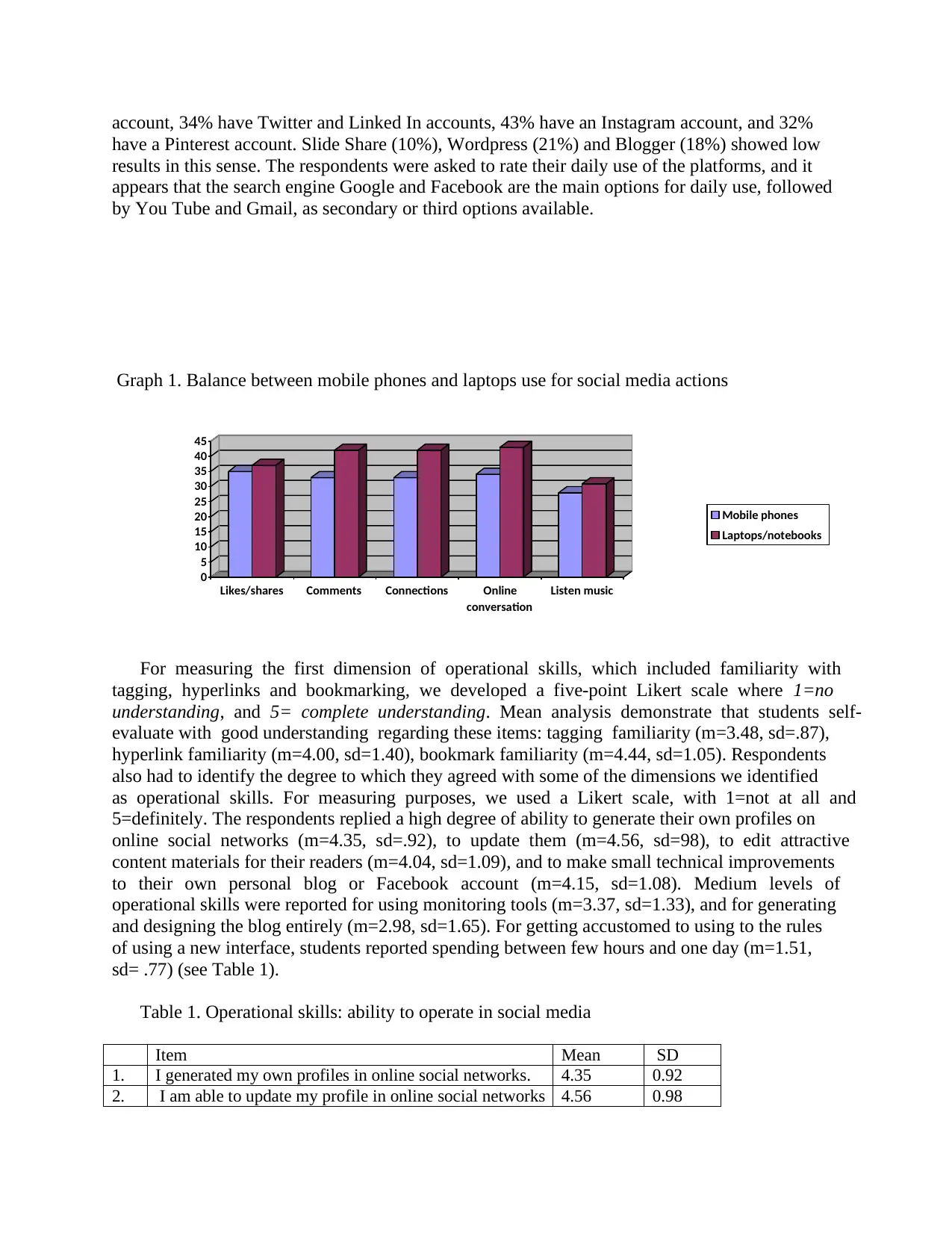

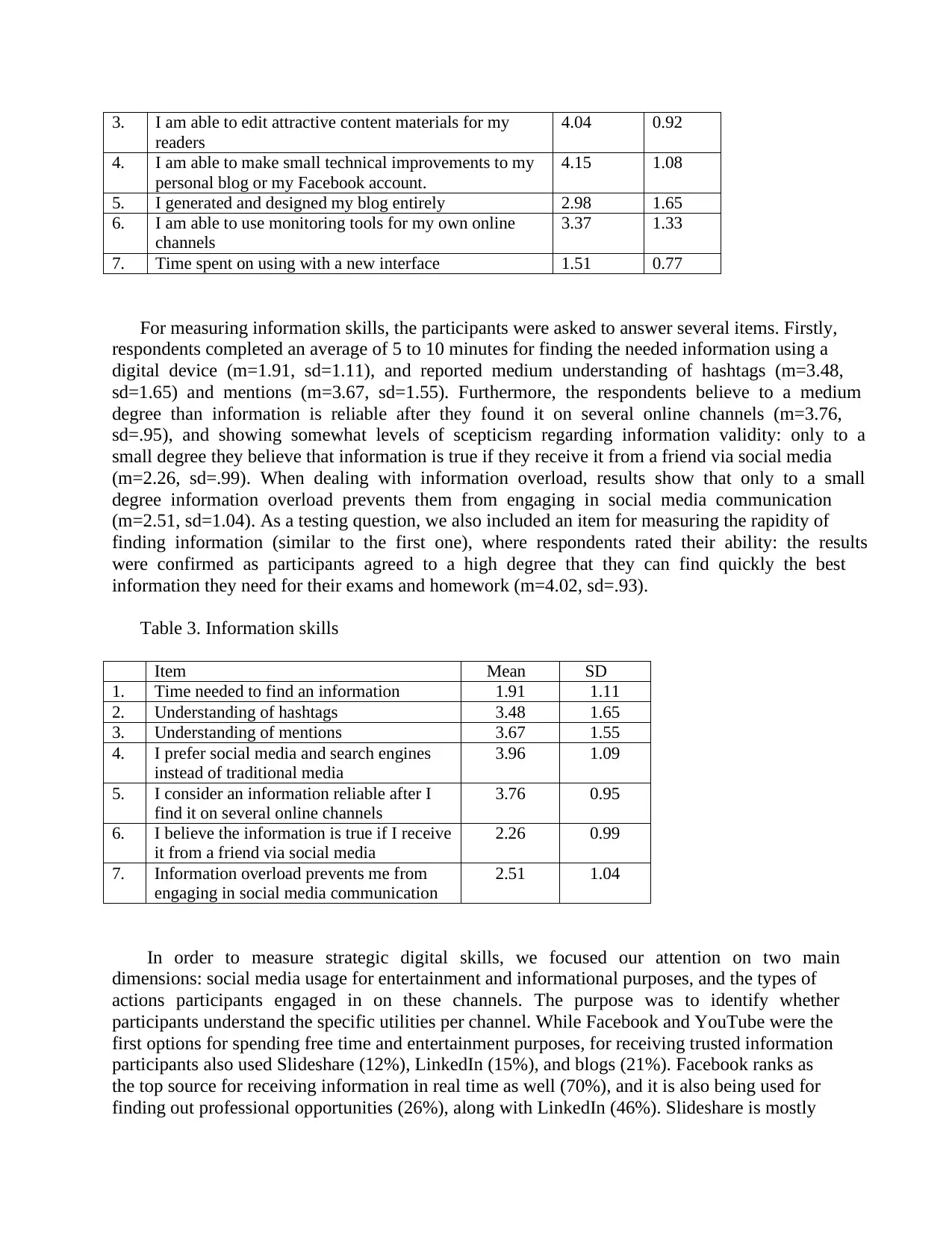

For measuring the first dimension of operational skills, which included familiarity with

tagging, hyperlinks and bookmarking, we developed a five-point Likert scale where 1=no

understanding, and 5= complete understanding. Mean analysis demonstrate that students self-

evaluate with good understanding regarding these items: tagging familiarity (m=3.48, sd=.87),

hyperlink familiarity (m=4.00, sd=1.40), bookmark familiarity (m=4.44, sd=1.05). Respondents

also had to identify the degree to which they agreed with some of the dimensions we identified

as operational skills. For measuring purposes, we used a Likert scale, with 1=not at all and

5=definitely. The respondents replied a high degree of ability to generate their own profiles on

online social networks (m=4.35, sd=.92), to update them (m=4.56, sd=98), to edit attractive

content materials for their readers (m=4.04, sd=1.09), and to make small technical improvements

to their own personal blog or Facebook account (m=4.15, sd=1.08). Medium levels of

operational skills were reported for using monitoring tools (m=3.37, sd=1.33), and for generating

and designing the blog entirely (m=2.98, sd=1.65). For getting accustomed to using to the rules

of using a new interface, students reported spending between few hours and one day (m=1.51,

sd= .77) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Operational skills: ability to operate in social media

Item Mean SD

1. I generated my own profiles in online social networks. 4.35 0.92

2. I am able to update my profile in online social networks 4.56 0.98

have a Pinterest account. Slide Share (10%), Wordpress (21%) and Blogger (18%) showed low

results in this sense. The respondents were asked to rate their daily use of the platforms, and it

appears that the search engine Google and Facebook are the main options for daily use, followed

by You Tube and Gmail, as secondary or third options available.

Graph 1. Balance between mobile phones and laptops use for social media actions

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Likes/shares Comments Connections Online

conversation

Listen music

Mobile phones

Laptops/notebooks

For measuring the first dimension of operational skills, which included familiarity with

tagging, hyperlinks and bookmarking, we developed a five-point Likert scale where 1=no

understanding, and 5= complete understanding. Mean analysis demonstrate that students self-

evaluate with good understanding regarding these items: tagging familiarity (m=3.48, sd=.87),

hyperlink familiarity (m=4.00, sd=1.40), bookmark familiarity (m=4.44, sd=1.05). Respondents

also had to identify the degree to which they agreed with some of the dimensions we identified

as operational skills. For measuring purposes, we used a Likert scale, with 1=not at all and

5=definitely. The respondents replied a high degree of ability to generate their own profiles on

online social networks (m=4.35, sd=.92), to update them (m=4.56, sd=98), to edit attractive

content materials for their readers (m=4.04, sd=1.09), and to make small technical improvements

to their own personal blog or Facebook account (m=4.15, sd=1.08). Medium levels of

operational skills were reported for using monitoring tools (m=3.37, sd=1.33), and for generating

and designing the blog entirely (m=2.98, sd=1.65). For getting accustomed to using to the rules

of using a new interface, students reported spending between few hours and one day (m=1.51,

sd= .77) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Operational skills: ability to operate in social media

Item Mean SD

1. I generated my own profiles in online social networks. 4.35 0.92

2. I am able to update my profile in online social networks 4.56 0.98

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3. I am able to edit attractive content materials for my

readers

4.04 0.92

4. I am able to make small technical improvements to my

personal blog or my Facebook account.

4.15 1.08

5. I generated and designed my blog entirely 2.98 1.65

6. I am able to use monitoring tools for my own online

channels

3.37 1.33

7. Time spent on using with a new interface 1.51 0.77

For measuring information skills, the participants were asked to answer several items. Firstly,

respondents completed an average of 5 to 10 minutes for finding the needed information using a

digital device (m=1.91, sd=1.11), and reported medium understanding of hashtags (m=3.48,

sd=1.65) and mentions (m=3.67, sd=1.55). Furthermore, the respondents believe to a medium

degree than information is reliable after they found it on several online channels (m=3.76,

sd=.95), and showing somewhat levels of scepticism regarding information validity: only to a

small degree they believe that information is true if they receive it from a friend via social media

(m=2.26, sd=.99). When dealing with information overload, results show that only to a small

degree information overload prevents them from engaging in social media communication

(m=2.51, sd=1.04). As a testing question, we also included an item for measuring the rapidity of

finding information (similar to the first one), where respondents rated their ability: the results

were confirmed as participants agreed to a high degree that they can find quickly the best

information they need for their exams and homework (m=4.02, sd=.93).

Table 3. Information skills

Item Mean SD

1. Time needed to find an information 1.91 1.11

2. Understanding of hashtags 3.48 1.65

3. Understanding of mentions 3.67 1.55

4. I prefer social media and search engines

instead of traditional media

3.96 1.09

5. I consider an information reliable after I

find it on several online channels

3.76 0.95

6. I believe the information is true if I receive

it from a friend via social media

2.26 0.99

7. Information overload prevents me from

engaging in social media communication

2.51 1.04

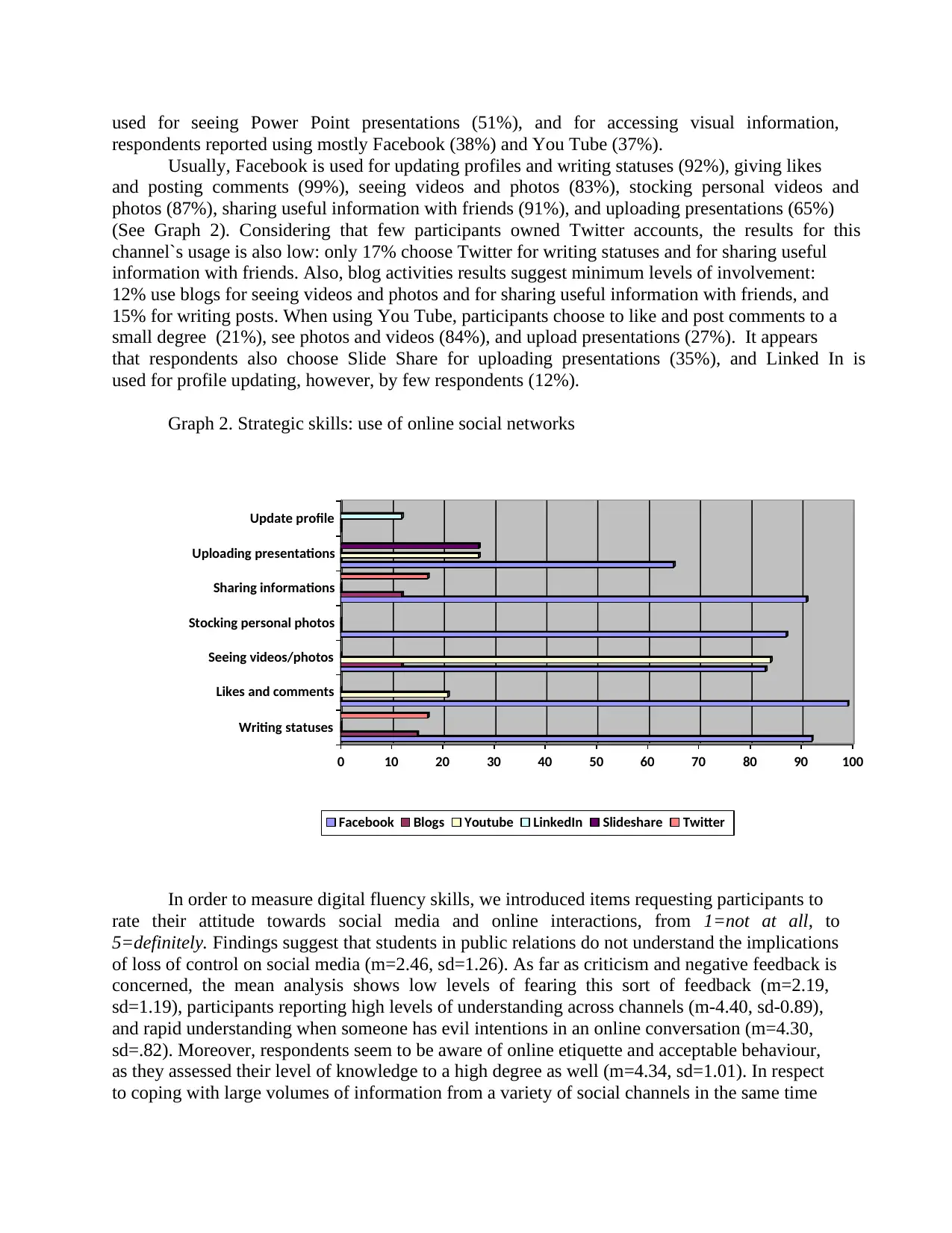

In order to measure strategic digital skills, we focused our attention on two main

dimensions: social media usage for entertainment and informational purposes, and the types of

actions participants engaged in on these channels. The purpose was to identify whether

participants understand the specific utilities per channel. While Facebook and YouTube were the

first options for spending free time and entertainment purposes, for receiving trusted information

participants also used Slideshare (12%), LinkedIn (15%), and blogs (21%). Facebook ranks as

the top source for receiving information in real time as well (70%), and it is also being used for

finding out professional opportunities (26%), along with LinkedIn (46%). Slideshare is mostly

readers

4.04 0.92

4. I am able to make small technical improvements to my

personal blog or my Facebook account.

4.15 1.08

5. I generated and designed my blog entirely 2.98 1.65

6. I am able to use monitoring tools for my own online

channels

3.37 1.33

7. Time spent on using with a new interface 1.51 0.77

For measuring information skills, the participants were asked to answer several items. Firstly,

respondents completed an average of 5 to 10 minutes for finding the needed information using a

digital device (m=1.91, sd=1.11), and reported medium understanding of hashtags (m=3.48,

sd=1.65) and mentions (m=3.67, sd=1.55). Furthermore, the respondents believe to a medium

degree than information is reliable after they found it on several online channels (m=3.76,

sd=.95), and showing somewhat levels of scepticism regarding information validity: only to a

small degree they believe that information is true if they receive it from a friend via social media

(m=2.26, sd=.99). When dealing with information overload, results show that only to a small

degree information overload prevents them from engaging in social media communication

(m=2.51, sd=1.04). As a testing question, we also included an item for measuring the rapidity of

finding information (similar to the first one), where respondents rated their ability: the results

were confirmed as participants agreed to a high degree that they can find quickly the best

information they need for their exams and homework (m=4.02, sd=.93).

Table 3. Information skills

Item Mean SD

1. Time needed to find an information 1.91 1.11

2. Understanding of hashtags 3.48 1.65

3. Understanding of mentions 3.67 1.55

4. I prefer social media and search engines

instead of traditional media

3.96 1.09

5. I consider an information reliable after I

find it on several online channels

3.76 0.95

6. I believe the information is true if I receive

it from a friend via social media

2.26 0.99

7. Information overload prevents me from

engaging in social media communication

2.51 1.04

In order to measure strategic digital skills, we focused our attention on two main

dimensions: social media usage for entertainment and informational purposes, and the types of

actions participants engaged in on these channels. The purpose was to identify whether

participants understand the specific utilities per channel. While Facebook and YouTube were the

first options for spending free time and entertainment purposes, for receiving trusted information

participants also used Slideshare (12%), LinkedIn (15%), and blogs (21%). Facebook ranks as

the top source for receiving information in real time as well (70%), and it is also being used for

finding out professional opportunities (26%), along with LinkedIn (46%). Slideshare is mostly

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

used for seeing Power Point presentations (51%), and for accessing visual information,

respondents reported using mostly Facebook (38%) and You Tube (37%).

Usually, Facebook is used for updating profiles and writing statuses (92%), giving likes

and posting comments (99%), seeing videos and photos (83%), stocking personal videos and

photos (87%), sharing useful information with friends (91%), and uploading presentations (65%)

(See Graph 2). Considering that few participants owned Twitter accounts, the results for this

channel`s usage is also low: only 17% choose Twitter for writing statuses and for sharing useful

information with friends. Also, blog activities results suggest minimum levels of involvement:

12% use blogs for seeing videos and photos and for sharing useful information with friends, and

15% for writing posts. When using You Tube, participants choose to like and post comments to a

small degree (21%), see photos and videos (84%), and upload presentations (27%). It appears

that respondents also choose Slide Share for uploading presentations (35%), and Linked In is

used for profile updating, however, by few respondents (12%).

Graph 2. Strategic skills: use of online social networks

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Writing statuses

Likes and comments

Seeing videos/photos

Stocking personal photos

Sharing informations

Uploading presentations

Update profile

Facebook Blogs Youtube LinkedIn Slideshare Twitter

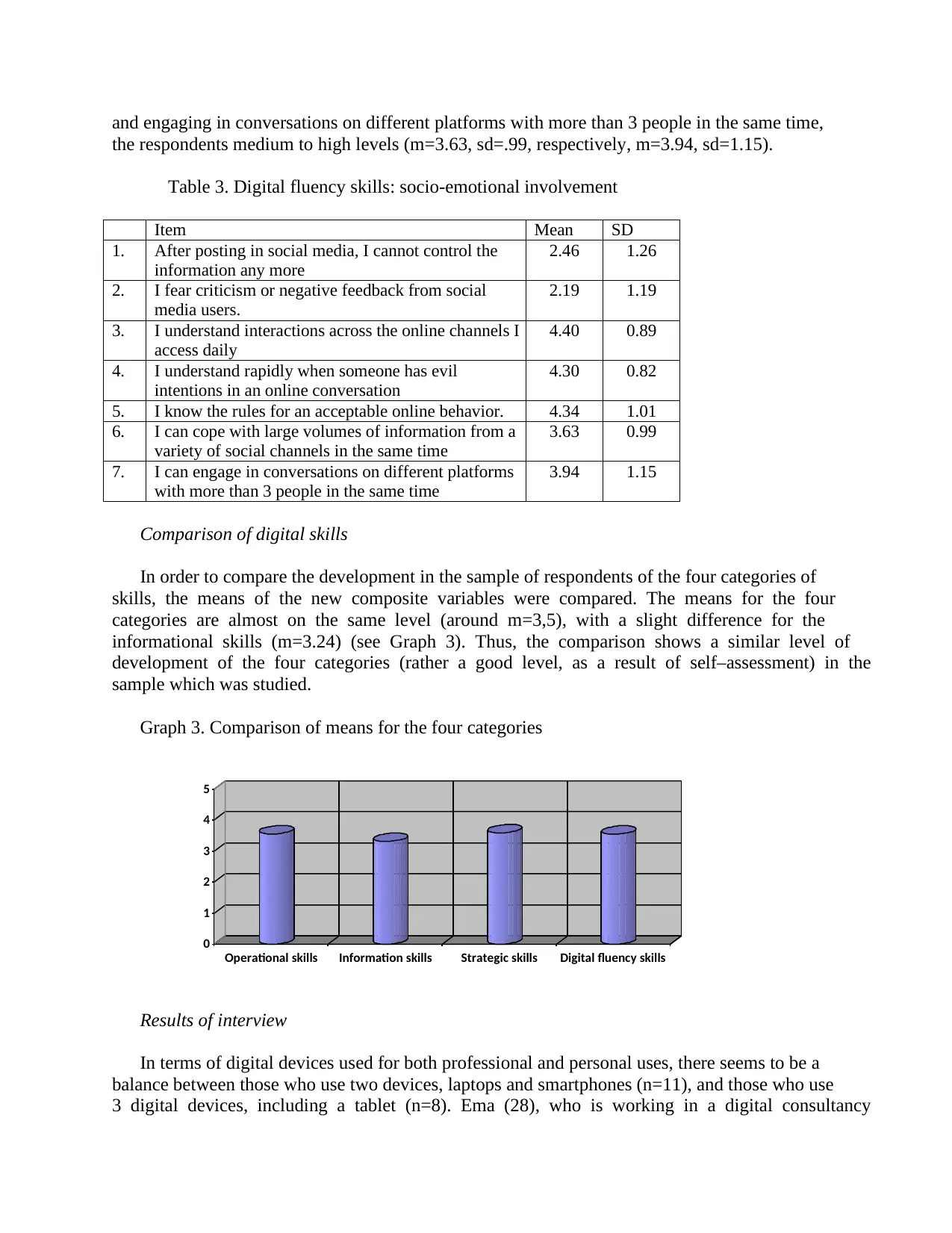

In order to measure digital fluency skills, we introduced items requesting participants to

rate their attitude towards social media and online interactions, from 1=not at all, to